Abstract

Objective

Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are common healthcare-related infections in intensive care units (ICUs). This study investigated the risk factors for CAUTIs in critically ill patients.

Methods

This study was a single-centre, retrospective, matched case-control study of patients undergoing indwelling catheterization in the ICU from December 1, 2016, to October 31, 2021. Patients with catheterizations were matched 1:4 with controls that were hospitalized in the ICU during the same period (with a difference in admission time of no more than two months).

Results

CAUTI occurred in 18 of 403 patients, with an infection rate of 3.7/per 1000 catheter days. Repeat catheterization of the urinary catheter (OR = 10.09) and days of antibiotic use (OR = 0.13) were independent risk factors for CAUTI (P < 0.05). A total of 31 pathogen strains were detected in urine samples from 18 CAUTI patients. The main pathogens were Gram-positive bacteria (n = 13, 41.9%), fungi (n = 10, 32.3%) and Gram-negative bacteria (n = 7, 22.6%). CAUTI was associated with an increase in hospitalization days by 26 days and an increase in total hospitalization cost of ¥160,000 (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

CAUTIs pose an economic and health burden for ICU patients. Repeat catheterization and longer use of antibiotics are to be avoided as much as possible.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-025-10839-0.

Keywords: Catheter-associated urinary tract infections, Risk factors, Case-control study, Nosocomial infection

Introduction

Currently, indwelling catheterization is a common procedure, especially in intensive care units (ICUs). The widespread use of indwelling catheterization has also led to an increased risk of infection. According to reports, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are now one of the six major healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs) [1]. Research indicates that 95% of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in the ICU are associated with indwelling catheters [2]. CAUTIs are associated with adverse patient outcomes, including prolonged hospitalization, greater financial burden and increased mortality [3].

The duration of urinary catheter use is the primary risk factor for CAUTI [4]. Other potential risk factors include urethral injury caused by repeat catheterization, gender and age-related diabetes, among others [5]. Patients in the ICU often have severe conditions, undergo more invasive procedures, and have a higher likelihood of infection. It is necessary to determine the risk factors for CAUTIs in ICU patients. To this end, this study aimed to identify the rates and frequency of CAUTI and the risk factors of CAUTI among ICU patients.

Methods

Patients and study design

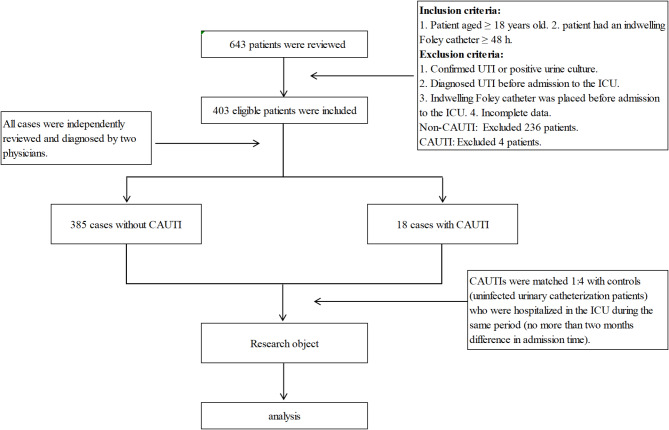

Data for this study were obtained from the Hospital Infection Management System at the First People’s Hospital of Guiyang City in Western China. This hospital is a comprehensive hospital with 1600 beds. This single-centre, retrospective, matched case–control study included patients undergoing indwelling catheterization in the ICU at the First People’s Hospital of Guiyang City from December 1, 2016, to October 31, 2021. The date of accessing the data was 15/1/2022. The case data of 634 patients were reviewed and, ultimately, 403 eligible patients were included. Patients with CAUTIs were matched 1:4 with controls (uninfected urinary catheterization patients) who were hospitalized in the ICU during the same period (no more than two months difference in admission time). All cases were independently reviewed and diagnosed by two physicians (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of research design

The data collected for this study comprised demographic, bacteriological, and clinical data, including baseline patient characteristics, comorbidities, infections, antibiotic therapy, outcomes, laboratory data and microbiological data. The study was a retrospective study of medical records. The ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent. Authors had not access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection.

Diagnostic criteria

CAUTI was diagnosed in accordance with the American CDC/NHSN criteria [6], as follows: (1) The patient had an indwelling urinary catheter that had been in place for > 2 days on the date of the event (day of device placement = Day 1) and was either still present on the date of the event or removed the day before the date of the event. (2) The patient had at least one of the following signs or symptoms: (a) fever (> 38.0 C), (b) suprapubic tenderness and (c) costovertebral angle pain or tenderness. 3. The patient had a urine culture with no more than two species of organisms, at least one of which was a bacterium of ≥ 105 CFU/ml. If more than two types of microorganisms were isolated, the sample was considered to be contaminated.

Inclusion criteria

(1) Patient aged ≥ 18 years old; (2) patient had an indwelling Foley catheter ≥ 48 h.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Confirmed UTI or positive urine culture. (2) Diagnosed UTI before admission to the ICU. (3) Indwelling Foley catheter was placed before admission to the ICU. (4) Incomplete data.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 22.0). Quantitative data were converted into count data using the median method, and count data were statistically described using ratios (%). Intergroup comparisons of count data were conducted using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the causal relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables, with backward stepwise regression modelling to exclude the influence of collinear variables. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Risk factors

We retrospectively reviewed the data of 634 ICU patients. A total of 403 patients with indwelling urinary catheters were included in the study, including 242 males and 161 females aged 18–98 years; the median age was 67 years. The total duration of catheter use was 4818 days. Among the 403 subjects, there were 385 cases without CAUTI and 18 cases with CAUTI. The infection rate was 3.74/1000 catheter days.

Then, the risk factors for CAUTI were analysed. Univariate analysis showed that urinary catheter days, repeat catheterization of the urinary catheter, ventilator intubation days, repeat insertion of a central venous catheter, type of antibiotics used and days of antibiotics use were significantly associated with CAUTI (p < 0.01) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of basic information of the patients

| Factor | CAUTI (n, %) n = 18 |

Non- CAUTI (n, %) n = 72 | χ2 | OR | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex(male) | 10(55.6) | 45(62.5) | 0.29 | 0.75 | 0.26∼3.13 | 0.59 |

| Age(≥72) | 8(44.4) | 37(51.4) | 0.28 | 0.76 | 0.27∼2.13 | 0.60 |

| Smoking | 6(33.3) | 2839.4) | 0.23 | 0.83 | 0.28∼2.48 | 0.63 |

| Drinking | 2(11.1) | 24(33.8) | 3.58 | 0.27 | 0.06∼1.26 | 0.06 |

| Mortality | 7(38.9) | 23(31.9) | 0.41 | 1.36 | 0.46∼3.95 | 0.52 |

| Hypertension | 9(50.0) | 32(45.8) | 0.10 | 1.18 | 0.42∼3.32 | 0.75 |

| Diabetes | 5(27.8) | 17(23.6) | 0.14 | 1.24 | 0.39∼3.99 | 0.71 |

| Heart disease | 7(38.9) | 29(40.3) | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.33∼2.72 | 0.91 |

| Brain disease | 7(38.9) | 37(51.4) | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.21∼1.73 | 0.34 |

| Kidney disease | 4(22.2) | 17(23.6) | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.27∼3.18 | 0.90 |

| Malignancies | 1(5.6) | 5(6.9) | 0.00 | 0.79 | 0.09∼7.20 | 0.99 |

| Pulmonary disease | 15(83.3) | 49(69.4) | 1.38 | 2.20 | 0.58∼8.38 | 0.24 |

| Consciousness disorders | 4(22.2) | 20(27.8) | 0.23 | 0.74 | 0.22∼2.53 | 0.63 |

| Hepatic disease | 0(0.0) | 10(13.9) | — | 0.00 | — | 0.20 |

| Prostatic hypertrophy | 2(11.1) | 5(6.9) | 0.35 | 1.67 | 0.30∼9.43 | 0.56 |

| Urolithiasis | 0(0.0) | 4(5.6) | — | 0.00 | — | 0.58 |

| Other infections outside the urinary system | 18(100.0) | 60(83.3) | — | — | — | 0.12 |

| Surgical operation | 1(5.6) | 9(12.5) | 0.70 | 0.41 | 0.05∼3.48 | 0.40 |

| Kinds of antibiotics used(<2, %) | 2(11.1) | 43(59.7) | 13.61 | 0.08 | 0.02∼0.39 | < 0.01 |

| Days of antibiotics use (<12 days, %) | 2(11.1) | 46(63.9) | 16.12 | 0.07 | 0.02∼0.33 | < 0.01 |

| Using immunosuppressants | 7(38.9) | 30(41.7) | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.31∼2.56 | 0.83 |

| Radiation therapy/Chemotherapy | 0(0.0) | 1(1.4) | — | 0.00 | — | 1.00 |

| Perineal care | 18(100.0) | 69(97.2) | — | — | — | 1.00 |

| APACHE score(≥21, %) | 8(44.4) | 37(51.4) | 0.28 | 0.76 | 0.27∼2.14 | 0.60 |

| Charlson comorbidity index(≥5, %) | 8(44.4) | 37(51.4) | 0.28 | 0.76 | 0.27∼2.14 | 0.60 |

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of indwelling catheter condition of the patients

| Factor | CAUTI (n, %) n = 18 |

Non- CAUTI (n, %) n = 72 | χ2 | OR | 95%CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary catheter-days(≦9 days, %) | 1(5.6) | 46(63.9) | 19.64 | 0.03 | 0.01∼0.26 | < 0.01 |

| Repeated intubation (Urinary catheter) | 14(77.8) | 12(16.7) | 26.18 | 17.50 | 4.90∼62.46 | < 0.01 |

| Medical advice for extubation | 4(22.2) | 6(8.3) | 2.81 | 3.14 | 0.78∼12.62 | 0.09 |

| Ventilator intubation | 15(83.3) | 44(62.0) | 2.93 | 3.00 | 0.79∼11.32 | 0.09 |

| Ventilator intubation-days(≦4 days, %) | 4(22.2) | 41(56.9) | 6.94 | 0.22 | 0.06∼0.72 | < 0.01 |

| Repeated intubation (Ventilator) | 5(27.8) | 9(12.5) | 2.56 | 2.69 | 0.77∼9.36 | 0.11 |

| Central venous catheters | 11(61.1) | 48(66.7) | 0.20 | 0.79 | 0.27∼2.28 | 0.66 |

| Central venous catheters-days | 5(27.8) | 44(61.1) | 6.45 | 0.25 | 0.08∼0.76 | 0.25 |

| Repeated intubation (Central venous catheter) | 3(16.7) | 0(0.0) | — | 0.00 | — | < 0.01a |

a Fisher’s exact test

After all variables were included in the regression model, the results showed that repeat catheterization of the urinary catheter (OR = 10.90, 95% CI 2.85–41.69) and days of antibiotics use (OR = 0.13, 95% CI 0.03–0.67) were significant independent risk factors for CAUTI (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Binary logistic analysis of the risk factors for patients with CAUTI

| Factor | B | S.E. | Wald | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeated intubation (Urinary catheter) | 2.39 | 0.68 | 12.18 | 10.90 | 2.85~41.69 | < 0.01 |

| Days of antibiotics use (<12) | -2.06 | 0.84 | 5.96 | 0.13 | 0.03~0.67 | 0.02 |

Distribution of opportunistic pathogens

A total of 31 pathogen strains were detected in the urine samples of 18 CAUTI patients. These included Gram-positive bacteria (n = 13, 41.94%) and fungi (n = 10, 41.94%), followed by Gram-negative bacteria (n = 7, 22.58%). The most common pathogens included Enterococcus faecium (n = 10, 32.26%), Candida albicans (n = 5, 16.13%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 3, 9.68%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 3, 9.68%) (S1).

Outcomes of patients with CAUTI

Compared with the non-CAUTI group, the number of days of hospitalisation was increased in the CAUTI group by 26 days (p < 0.001), the total hospitalization cost was increased by ¥ 161,000 (about $ 22115, p < 0.001) and the discharge all-cause mortality was increased by 1.2 times (Table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes between the two groups

| Outcome | CAUTI (n = 18) | Non- CAUTI (n = 72) | Z/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization (median/inter-quartile range) | 37.00(47.00) | 11.50(15.00) | −4.826a | < 0.001 |

|

Total cost of hospitalization (10,000 yuan, median/inter-quartile range) |

21.91(19.00) | 5.30(7.00) | −4.610a | < 0.001 |

| Discharge all-cause mortality (n,%) | 7(23.30) | 11(18.30) | 0.313b | 0.576 |

a Wilcoxon singned-rank test, b Chi-square test

Discussion

In this study, the infection rate was 3.74/1000 catheter days. This finding is similar to previous reports [7]. The results revealed that repeat catheterization and days of antibiotics use were independent risk factors for CAUTI. Patients in ICU might have longer catheterization days, and medical staff would regularly replace the catheter according to guidelines [8]. But repeat catheterization might lead to bacterial translocation or urethral injury, ultimately creating conditions for CAUTI. Bacteria can enter the bladder by contaminating the catheter tip with the distal urethral microbiota during insertion or advancing along its exterior or interior [9]. The number of days of antibiotics use as an independent risk factor for CAUTI has rarely been reported before. The human urethra also contains microbial colonies [10]. Traditionally, bacterial culture of urine mainly identifies pathogens involved in UTIs. On the contrary, slow-growing, anaerobic, or picky organisms such as Corynebacterium, Lactobacillus and Ureaplasma are rarely isolated from the urinary tract because conventional cultivation techniques are not designed to support the growth of these genera [11–14]. These urinary tract microbiota might serve as barriers to urinary tract pathogens [15]. The use of antibiotics might break down these barriers. For example, in rats where antibiotic treatment suppressed the microbiota, the urinary metabolite profiles were significantly different between the treatment group and the control group [16]. There might be some correlation between the duration of antibiotics use and CAUTI. This deserves attention in future research. In the univariate analyses, there were significant differences in the number of urinary catheter days, ventilator intubation days, repeat insertion of a central venous catheter and types of antibiotics used between the two groups, but these differences were not observed in the multivariate analysis. The results of the multivariate analysis were different from other studies [7]. This might be due to differences in our research design and the included participants.

In the current study, the most commonly detected bacteria were Enterococcus faecium and Candida albicans. This result is consistent with previous reports [17, 18]. Enterococcus is likely to be extraluminally acquired [19]. Therefore, in the prevention and control of CAUTIs, attention should be paid to post-catheterization care, such as hand hygiene, environmental cleaning and disinfection measures, to reduce contact transmission.

In addition, the current results demonstrated that CAUTI significantly increases patients’ hospitalization time and economic burden. This is similar to a previous study [7].

There are several limitations of this study that should be noted. First, this was a single-centre study, which limits the representativeness of the results. Second, this was a retrospective study with a limited sample size. Third, several included study patients could have bacterial/fungal colonization rather than true CAUTI. Nonetheless, the results provide directions for future research.

Conclusion

CAUTIs pose economic and health burdens to ICU patients, and thus, are worthy of attention. In preventing CAUTIs, attention should be paid to Repeat catheterization and the risk of infection due to long-term antibiotics use.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the Guiyang Board of Health and Science and Technology Fund of Guizhou Provincial Health Commission.

Author contributions

Zhao Tao, Li Yajun, Zhou Xuan and Du Guiqin contributed to the study conception and design. Zhao Tao, Li Yajun, Zhou Xuan and Du Guiqin contributed to writing-review and editing. Zhao Tao contributed to project administration and funding acquisition. All authors wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to investigation. Tian Juan and Tu Rui prepared figure 1 and contributed to formal analysis. Xiao Zuyan, Zhang Bingbing and Zhou Ruiqi prepared all tables.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Plan Project of Guiyang Health and Family Planning Commission under grant number [2018 Zhuwei technology contract No.002]; Science and Technology Fund of Guizhou Provincial Health Commission under grant number[gzwjkj 2020-1-203].

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to publication

This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the First People’s Hospital of Guiyang. Our study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The medical ethics committee of the First People’s Hospital of Guiyang has agreed to waive the consent of the participants.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Li Yajun, Zhou Xuan and Tian Juan contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Du Guiqin, Email: dgqlcc0718@163.com.

Zhao Tao, Email: 15186613384@163.com.

References

- 1.Cassini A, Plachouras D, Eckmanns T, et al. Burden of six healthcare-associated infections on European population health: estimating incidence-based disability adjusted life years through a population prevalence-based modeling study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:1–16. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leblebicioglu H, Ersoz G, Rosenthal VD, et al. Impact of a multidimensional infection control approach on catheter-associated urinary tract infection rates in adult intensive care units in 10 cities of Turkey: international nosocomial infection control consortium findings (INICC). Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:885–91. 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollenbeak CS, Schilling AL. The attributable cost of catheter-associated urinary tract infections in the United States: a systematic review. Am J Infect Control. 2018;6(5):1438–46. 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kranz J, Schmidt S, Wagenlehner F, et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adult patients—preventive strategies and treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:83–8. 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farsi AH. Risk factors and outcomes of postoperative catheter-associated urinary tract infection in colorectal surgery patients: a retrospective cohort study. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15111. 10.7759/cureus.15111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Healthcare Safety Network(NHSN) of American. 2015 patient safety component manual (Urinary tract infection events) [M]. CDC/NHSN Protocol Clarifications. 2015;7–1 ∼ 7–17.

- 7.Shen L, Fu T, Huang L, et al. 7295 elderly hospitalized patients with catheter-associated urinary tract infection: a case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):825. 10.1186/s12879-023-08711-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Industry Standards of the People’s Republic of China. Prevention and control standards for hospital infection in intensive care unit WS/T 509–2016. December 27, 2016.

- 9.Barford JM, Anson K, Hu Y, et al. A model of catheter-associated urinary tract infection initiated by bacterial contamination of the catheter tip. BJU Int. 2008;102:67–74. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe AJ, Toh E, Shibata N, et al. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(4):1376–83. 10.1128/JCM.05852-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, et al. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:871–6. 10.1128/JCM.02876-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soriano F, Tauch A. Microbiological and clinical features of corynebacterium urealyticum: urinary tract stones and genomics as the rosetta stone. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(7):632–43. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JW, Shim YH, Lee SJ. Lactobacillus colonization in infants with urinary tract infection. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(1):135–9. 10.1007/s00467-008-0974-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latthe PM, Toozs-Hobson P, Gray J. Mycoplasma and ureaplasma colonisation in women with lower urinary tract symptoms. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:519–21. 10.1080/01443610802097690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host–bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2021;292(5519):1115–8. 10.1126/science.1058709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swann JR, Tuohy KM, Lindfors P, et al. Variation in antibiotic-induced microbial recolonization impacts on the host metabolic phenotypes of rats. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(8):3590–603. 10.1021/pr200243t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng D, Li X, Liu P, et al. Epidemiology of pathogens and antimicrobial resistanceof catheter-associated urinary tract infections in intensivecare units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(12):e81–90. 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padawer D, Pastukh N, Nitzan O, et al. Catheter-associated candiduria: risk factors, medical interventions, and antifungal susceptibility. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(7):e19–22. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daifuku R, Stamm WE. Association of rectal and urethral colonization with urinary tract infection in patients with indwelling catheters. JAMA. 1984;252(15):2028–30. 10.1001/jama.1984.03350150028015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.