Abstract

KEY WORDS: Pediatric rehabilitation, traumatic brain injury, physical therapy, occupational therapy

Each year, pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) leads to an estimated 404,000 emergency department visits and 42,000 hospitalizations.1 In addition to emergency and acute hospital care needs, approximately 17,000 children per year with pediatric TBI are permanently disabled with persistent deficits in cognition, mobility, and performance of activities of daily living (ADLs).1–4 While the current continuum of trauma-related care includes disposition and reintegration into what would have been “normal” activities for a child prior to injury, the child with a moderate to severe TBI represents a special circumstance. In these cases, the child now needs to establish a “new normal” with the assistance of family and the medical team. Rehabilitation services are a critical part of this process, and delay in the initiation of a comprehensive rehabilitation program after pediatric TBI has been associated with worse functional outcomes.5 However, there is wide variation among hospitals in the provision of rehabilitation therapies for children with TBI.6 The American College of Surgeons quality program for excellence in trauma centers advocates for “early multidisciplinary assessment of patients to determine their rehabilitation needs and provide relevant services” and emphasizes that “these needs should be met as early as possible during the initial hospitalization.”7 Notably, the resources and reference sections corresponding to these rehabilitation recommendations list no available articles and contain no specific details. Consensus is lacking regarding definitions of rehabilitation services and appropriate timing for initiation and progression of rehabilitation services along the continuum of care.

In response to these issues, the Health Resources & Services Administration funded Emergency Medical Services for Children Innovation and Improvement Center (EIIC) Trauma Domain Team convened a panel of subject matter experts (SMEs). Our goal was to integrate the best research evidence, clinical experience, values and preferences, and resources to form the basis for clinical practice guidelines that would improve patient care for children with TBI.8 Rather than dictating a one-size-fits-all approach to patient care, clinical practice guidelines offer an evaluation of the quality of the relevant scientific literature and an assessment of the likely benefits and harms of a particular treatment. This information enables health care providers to proceed accordingly, selecting the best care for a unique patient based on his or her preferences.9 As part of this initiative, we conducted a systematic review of the literature for evidence supporting whether specific timing of initiation of rehabilitation services after TBI influences patient outcomes. In the absence of evidence revealed by the systematic review, the expert panel created an algorithm to guide prospective research on early initiation of rehabilitation services for hospitalized children with TBI. We also developed recommendations for standardized definitions of rehabilitation and rehabilitation services.

METHODS

In October of 2018, the EIIC Trauma Domain Team began work on a proposal to complete a systematic review of the literature regarding the initiation of pediatric rehabilitation for children who had sustained a TBI. Approval from the EIIC leadership was obtained in December of 2018. Subject matter experts from institutions across the United States were identified and invited to participate in the project. The expert panel was composed of two EIIC representatives, two pediatric trauma surgeons, three pediatric physiatrists, two pediatric physical therapists, two pediatric occupational therapists, one pediatric speech therapist, one pediatric rehabilitation psychologist, and one evidence-based practice specialist. The expert panel had monthly phone calls from December 2018 to December 2019 and two in-person meetings in April 2019 and October 2019.

Literature Review

During the first in-person meeting, the expert panel developed a patient/population, intervention, comparison and outcomes (PICO) question, which was approved by the Evidence Based Outcomes Center. The PICO question was: “In children with severe TBI (Glasgow Coma Scale score < 8), does early initiation of rehabilitation therapies improve outcomes?” PubMed and Cochrane databases were systemically searched for English language articles published between January 1990 and December 2018 using a combination of MeSH and free-text terms (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/TA/E218). The Evidence-Based Practice Specialist reviewed titles and abstracts generated by the search strategy for relevance to the PICO question. Relevant articles were pulled for full-text review by the Evidence-Based Practice Specialist and further narrowed to studies including pediatric populations for review by the SME panel.

Expert Panel Review and Consensus Recommendations

During the second in-person meeting, the expert panel worked to develop a consensus guideline for the initiation of rehabilitation for the child who has sustained a TBI. We created a standardized algorithm to guide future development of the literature. The products of this meeting were a set of standardized definitions of the different components of rehabilitation services and a visual aid depicting our algorithm to address early initiation of rehabilitation services for hospitalized children with TBI.

RESULTS

Literature Review

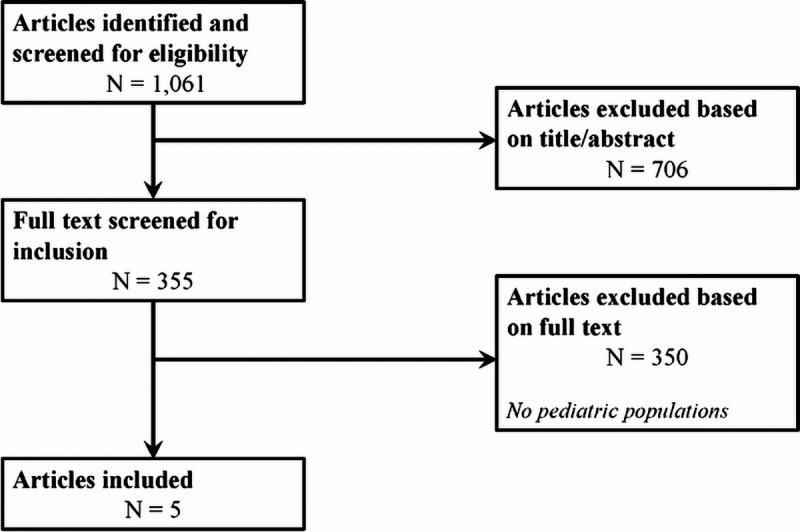

Of the 1,061 titles and abstracts identified by the search algorithm, 355 studies were selected for full-text review, and 5 of these were relevant to the PICO question (Fig. 1). The included studies investigated functional outcomes in children with severe TBI treated in inpatient rehabilitation settings; however, none addressed the timing of rehabilitation initiation during acute care hospitalization (Table 1). Three of the five studies focused on disorders of consciousness populations with the primary functional outcome of emergence to a conscious state.11,12,14 The remaining studies addressed provision of therapy services and functional progression during acute inpatient rehabilitation.10,13 All of these studies were descriptive in nature and did not include comparison populations.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of systematic review process and evaluation of articles for inclusion. N indicates the number of articles at each step. Exclusion criteria applied to full-text review are listed in the relevant text box.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in Literature Review

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Setting/Study Population | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2004)10 | Retrospective cohort | 814 children discharged from acute inpatient rehabilitation at 12 facilities from 1996 to 1998 | Therapy provision during inpatient rehabilitation varied widely depending on age and impairmentGreatest functional gains: children >7 years old with traumatic injuries |

| Eilander et al. (2005)11 | Retrospective pre-post | 145 children/young adults with DOC admitted to an Early Intensive Neurorehabilitation Program between December 1987 and January 2001 | 2/3 emerged to full consciousnessSignificant prognostic factors: LOC at admission Etiology Time since injuryBetter outcomes after traumatic injuries |

| Eilander et al. (2007)12 | Retrospective pre-post | 145 children/young adults with DOC admitted to an Early Intensive Neurorehabilitation Program between December 1987 and January /2001 | Strong correlation between DRS and GOSE scoresMore patients with TBI than ABI achieved functional semi-independence |

| Foy and Somers (2013)13 | Retrospective cohort | 106 adolescents/young adults admitted to a residential neurorehabilitation facility since 2002 | Statistically significant functional improvements in both TBI and ABIFunctional level at discharge predicted by function at admission and LOS |

| Pham et al. (2014)14 | Retrospective case series | 14 patients aged 1–20 years with DOC admitted to acute inpatient rehabilitation from August 2009 to December 2012 | 10/14 patients emerged to the conscious state during admissionHigher LOC and older age were associated with emergence during admission |

ABI, acquired (nontraumatic) brain injury; DOC, disorders of consciousness; DRS, Disability Rating Scale; GOSE, Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended; LOC, level of consciousness; LOS, length of stay.

Standardized Terms and Definitions

The expert panel developed a list of key terms that need to be understood when discussing rehabilitation after TBI (Table 2). Of note, the goal of rehabilitation is to optimize the functioning of individuals in the context of environments relevant to daily life. In pursuit of this goal, rehabilitation services encompass all specialized health care services that may be integrated into each patient’s care. Individual components of rehabilitation services, such as Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) and specific therapy disciplines are also defined in Table 2. Fostering a shared understanding of these components and the overall goals of rehabilitation forms the basis of our proposed algorithm for advancing the study of initiation of rehabilitation services after pediatric TBI.

TABLE 2.

Key Terms and Standardized Definitions for the Field of Rehabilitation Medicine. Citations Are Provided for Further Reading on Each Term

| Terms | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Rehabilitation | “A set of measures that assist individuals who experience, or are likely to experience, disability to achieve and maintain optimal functioning in interaction with their environments”15 |

| Rehabilitation services | “Special health care services that help a person regain physical, mental, and/or cognitive (thinking and learning) abilities that have been lost or impaired as a result of disease, injury, or treatment. Rehabilitation services help people return to daily life and live in a normal or near-normal way. These services may include physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, cognitive therapy, and mental health rehabilitation services.”16 |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | “Physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R), also known as physiatry or rehabilitation medicine, aims to enhance and restore functional ability and quality of life to those with physical impairments or disabilities affecting the brain, spinal cord, nerves, bones, joints, ligaments, muscles, and tendons.”17 |

| Physical therapy | “Physical therapists (PTs) are movement experts who optimize quality of life through prescribed exercise, hands-on care, and patient education.”18 |

| Occupational therapy | “In its simplest terms, occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants help people across the lifespan participate in the things they want and need to do through the therapeutic use of everyday activities (occupations).”19 |

| Speech and Language pathology | “Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) work to prevent, assess, diagnose, and treat speech, language, social communication, cognitive-communication, and swallowing disorders in children and adults.”20 |

Consensus Guideline for Initiation of Rehabilitation After Pediatric TBI

The primary outcome of the expert panel discussions was the creation of an algorithm to address early initiation of rehabilitation services for hospitalized children with TBI (Fig. 2). The algorithm starts with a TBI requiring hospitalization. We purposefully did not include severity (in the form of Glasgow Come Scale, Injury Severity Score, Head Injury Severity Score, etc.) as this was not the focus. The first recommended metric is consultation of rehabilitation services (PT/OT/Speech/PM&R) within 48 hours of a TBI warranting hospitalization. In the absence of evidence from existing studies, this recommendation reflects the consensus of the expert panel and is already in place at some institutions.

Figure 2.

Visual algorithm to address early initiation of rehabilitation services for hospitalized children with TBI. Single asterisk indicates the step at which metric tracking can be initiated by adding information to a quality improvement plan or institutional trauma registry. Separate pathways are shown for patients based on whether prolonged ventilation will be required. At the end of each branch is a disposition checklist of items that should be addressed prior to discharge. Table 3 provides detail regarding disposition requirements.

We then dichotomized based on whether prolonged ventilation needs were present. In the acute stage of moderate to severe TBI, treatment interventions greatly vary based on degree of injury, medical stability, and comorbidities. Children requiring ICU level of care and prolonged intubation after TBI often require special rehabilitation considerations, such as consciousness assessment, management of neuro agitation and/or paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity, bowel/bladder management, and positioning to prevent development of decubitus ulcers and contractures. Regardless of the setting in which rehabilitation services are initiated, recommended rehabilitation interventions include early mobilization, assessment of swallowing and language skills, and ADLs. In children who did not require intubation or were extubated within 48 hours of injury, rehabilitation services should also focus on functional mobility assessment, family counseling, and disposition planning. The role of PM&R in the management of the child with severe TBI ranges from identification and management of paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity, management of post-TBI agitation and sleep disturbances, communication with the team and family regarding the severity of injury and recovery potential, addressing bracing needs associated with immobility, and evaluation and determination of the appropriate level of rehabilitation services ranging from subacute to acute inpatient to outpatient.

At the end of each branch is a Disposition Checklist to be addressed prior to discharge of the child who has sustained a TBI. For a more in depth view, see Table 3. The first item on the list is disposition location. Understanding details about the environment into which the child will be discharged is important to ensure appropriate equipment and access to the discharge setting. Specific considerations include the need for ramps to enter the home, planning a second path of egress in an emergency if the primary exit is blocked, and accessibility of sleeping and bathroom arrangements. Second on the disposition checklist is a comprehensive list of specialists who will need to see the patient after discharge. While Primary Care Physicians may be versed in concussion protocols and Return to Learn or Return to Play protocols, many are not. If this is the case in the area in which the child lives, appropriate follow-up needs to be determined prior to discharge. This may require follow-up with a trauma clinic, PM&R clinic, etc. The appropriate time frame should be determined by the severity of injury and likelihood of complications. Third on the disposition checklist is supplies, which range from pain medications to catheters for clean intermittent catheterizations to durable medical equipment. The last item on the disposition checklist is a learning plan. These recommendations can range from no return to school until seen in clinic to return to school part time for a week with subsequent increase as tolerated. It also includes recommendations for return to sports and other recreational activities. For concussions, both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have guidelines published for “Return to Learn” and “Return to Play.”21,22

TABLE 3.

Disposition Checklist With Explanations

DISCUSSION

Systematic review of the literature revealed that sufficient evidence is not yet available to address our PICO question of whether early initiation of rehabilitation services improves outcomes in children with severe traumatic brain injuries (Glasgow Come Scale score <8). Many challenges arose in addressing our PICO question, including: (1) variability in injury severity classification; (2) variability in timing of (a) initiation of rehabilitation and (b) follow-up assessment; (3) variability in age groupings within pediatric populations; (4) loss to follow up; (5) access to rehabilitation care including treatment variability during acute care phase; (6) variability in outcome measures; (7) difficulty translating performance across different standardized tests; (8) measurement of real-world functioning; (9) relatively young age of the subspecialty of physical medicine and rehabilitation.

Since the evidence does not yet exist to support evidence-based guidelines, the SME panel created an algorithm to address early initiation of rehabilitation services for hospitalized children with TBI. This algorithm provides a framework for development of prospective research studies and quality improvement initiatives to determine optimal timing to initiate rehabilitation in children with severe TBI, as well as to elucidate the factors that should guide the application of future guidelines to each clinical situation. In addition, the recommendation for consultation of rehabilitation services (PT/OT/Speech/PM&R) within 48 hours of a TBI warranting hospitalization represents a trackable metric that could be added to institutional trauma quality improvement plans and registries.

It has been consistently shown that early mobilization is feasible and safe in the ICU setting.23,24 Specific to this patient population, Roth et al. found initiation of early therapeutic treatment for patients following acute neurological injury had no adverse effect despite completing therapy with elevated intracranial pressure.25 Related evidence suggests that initiating rehabilitation within 3 days of acquired brain injury is not harmful in children.26 Although feasible and safe, rehabilitation in the PICU setting is not straight-forward in practice due to the wide range of chronological, cognitive, and developmental ages of this patient population.23 The goals in rehabilitation of the child who has a moderate to severe TBI incorporate individualized and medically appropriate therapies, including tolerance to handling, calming techniques, positioning, range of motion, progressive strengthening, progressive endurance, and progressive mobilization. Agitation can be a barrier to early rehabilitation in children with moderate to severe TBI. Handling and calming techniques can assist with state regulation and decreasing agitation in various ICU settings. These techniques include but are not limited to: utilizing low stimulation precautions, swaddling, varying tactile pressure, and regulating sleep wake cycles.27 Optimizing joint alignment by utilizing appropriate positioning options (pressure relieving ankle foot orthoses, hip straps, knee immobilizers, splinting, and bracing) and range of motion exercises has been shown to be feasible and beneficial during the acute phase.25,28 As the child progresses along the medical continuum, therapeutic intervention should also evolve, including progressive strengthening, endurance, mobility, ADLs and recommendations for bracing and equipment with focus on safe discharge.

The disposition checklist items highlighted in the algorithm are intended to guide discharge planning for children with TBI who are discharged directly from acute care services. These recommendations are based on factors considered as part of the discharge planning process for all patients admitted to acute inpatient rehabilitation. Arranging appropriate follow-up care with primary care and specialists is particularly important since a study of health care utilization after pediatric TBI showed that 37% of caregivers of children requiring hospitalization for moderate to severe TBI did not see any physicians between discharge and 12 months after injury.29 In addition, 31% of those children had unmet or unrecognized health care needs 12 months after injury with higher unmet needs associated with more severe injuries, nonwhite race, Medicaid benefits, and disruption of family functioning.29 The recommended disposition checklist items are designed to minimize unmet and unrecognized health care needs of child by providing a framework to detect and meet changing needs throughout recovery.

CONCLUSION

Evidence does not currently exist for an evidence-based guideline for optimal timing of rehabilitation after TBI in children. The goal of this expert panel was to create an algorithm to guide prospective research on early initiation of rehabilitation services for hospitalized children with TBI. These recommendations build on the limited literature available and provide a basis for the development of clinical trials to determine the optimum timing and effectiveness of early initiation of rehabilitation services after pediatric TBI.

AUTHORSHIP

Conception and study design: C.M.N., E.H., B.L., K.D., S.L.W., S.S., B.N.-M., and M.E.F. participated in the development of the PICO question and literature review. Data acquisition: BL participated in performing the literature search and review of titles and abstracts to narrow to relevant studies for review by the expert panel. Data analysis and interpretation: C.M.N., E.H., B.L., K.D., S.L.W., S.S., B.N.-M., and M.E.F. participated in development of consensus recommendations. Drafting of the article: Creation of article figures and article writing were performed by C.M.N. and M.L.S. Critical revision: All authors participated in critical review of the article prior to submission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Diana Fendya (MSN (R), RN), Molly Fuentes (MD), Jaclyn Gould (DPT), Jordan Huffman (OTR/L) for their contributions to the development of this project and their participation in the subject matter expert panel.

Funding Disclosure: Supported in part by the EMS for Children Innovation and Improvement Center, Emergency Medical Services for Children, Health Resources and Services Administration

DISCLOSURE

Author disclosure forms have been supplied and are provided as Supplemental Digital Content (http://links.lww.com/TA/E219).

Footnotes

Published online: February 6, 2025.

A preliminary version of this work was presented by CN as a poster at the 2019 Pediatric Trauma Society meeting in San Diego, CA.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jtrauma.com).

Contributor Information

Christian M. Niedzwecki, Email: cmniedzw@texaschildrens.org.

Michelle L Seymour, Email: mlseymo3@texaschildrens.org.

Emily Hermes, Email: ekhermes@texaschildrens.org.

Betsy Lewis, Email: bslewis1@texaschildrens.org.

Kathryn DeMarco, Email: kdemarco@sralab.org.

Shari L. Wade, Email: shari.wade@cchmc.org.

Stacy Suskauer, Email: suskauer@kennedykrieger.org.

Bindi Naik-Mathuria, Email: bnaik@UTMB.EDU.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rutland-Brown W, Langlois JA, Thomas KE, Xi YL. Incidence of traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2003. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21(6):544–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montgomery V, Oliver R, Reisner A, Fallat ME. The effect of severe traumatic brain injury on the family. J Trauma. 2002;52(6):1121–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babikian T, Asarnow R. Neurocognitive outcomes and recovery after pediatric TBI: meta-analytic review of the literature. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):283–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popernack ML, Gray N, Reuter-Rice K. Moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury in children: complications and rehabilitation strategies. J Pediatr Health Care. 2015;29(3):e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumas HM, Haley SM, Ludlow LH, Rabin JP. Functional recovery in pediatric traumatic brain injury during inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(9):661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett TD, Niedzwecki CM, Korgenski EK, Bratton SL. Initiation of physical, occupational, and speech therapy in children with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(7):1268–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resources for optimal Care of the Injured Patient: 2022 standards [internet]. In: Verification Review Consultation Program for Excellence in Trauma Centers, American College of Surgeons. 2022: Mar [cited 2023 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/quality/verification-review-and-consultation-program/standards/.

- 8.Satterfield JM Spring B Brownson RC Mullen EJ Newhouse RP Walker BB, et al. Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice. Milbank Q. 2009;87(2):368–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines , Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, eds. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust [Internet]. In: Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011: [cited 2023 Feb 22]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209539/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CC, Heinemann AW, Bode RK, Granger CV, Mallinson T. Impact of pediatric rehabilitation services on children’s functional outcomes. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58(1):44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eilander HJ, Wijnen VJM, Scheirs JGM, de Kort PLM, Prevo AJH. Children and young adults in a prolonged unconscious state due to severe brain injury: outcome after an early intensive neurorehabilitation programme. Brain Inj. 2005;19(6):425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eilander HJ, Timmerman RBW, Scheirs JGM, Van Heugten CM, De Kort PLM, Prevo AJH. Children and young adults in a prolonged unconscious state after severe brain injury: long-term functional outcome as measured by the DRS and the GOSE after early intensive neurorehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2007;21(1):53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foy CML, Somers JS. Increase in functional abilities following a residential educational and neurorehabilitation programme in young adults with acquired brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;32(3):671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham K, Kramer ME, Slomine BS, Suskauer SJ. Emergence to the conscious state during inpatient rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury in children and young adults: a case series. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(5):E44–E48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization, World Bank . World report on disability 2011. 2011 [cited 2023 Feb 22]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44575 [PubMed]

- 16.Rehabilitation Services. National Cancer Institute Dictionary of Cancer Terms [Internet]: [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/rehabilitation-services. [Google Scholar]

- 17.What is Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation? [Internet]. American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: About Physiatry: [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.aapmr.org/about-physiatry/about-physical-medicine-rehabilitation. [Google Scholar]

- 18.What Physical Therapists Do [Internet]. American Physical Therapy Association: Becoming a PT: [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.apta.org/your-career/careers-in-physical-therapy/becoming-a-pt. [Google Scholar]

- 19.What is occupational therapy? [internet]. American Occupational Therapy Association: [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.aota.org/about/what-is-ot. [Google Scholar]

- 20.About Speech-Language Pathology [Internet]. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association: [cited 2019 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.asha.org/Students/Speech-Language-Pathologists/. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halstead ME. Return to learn. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;158:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HEADS UP: Returning to Sports and Activities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2019: (Injury Center: Brain Injury Basics). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuello-Garcia CA, Mai SHC, Simpson R, Al-Harbi S, Choong K. Early mobilization in critically ill children: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2018;203:25–33.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wieczorek B, Burke C, Al-Harbi A, Kudchadkar SR. Early mobilization in the pediatric intensive care unit: a systematic review. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2015;2015(4):129–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roth C, Stitz H, Kalhout A, Kleffmann J, Deinsberger W, Ferbert A. Effect of early physiotherapy on intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure. Neurocrit Care. 2013;18(1):33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fink EL Beers SR Houtrow AJ Richichi R Burns C Doughty L, et al. Early protocolized versus usual care rehabilitation for pediatric neurocritical care patients: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(6):540–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altimier L, Phillips R. The neonatal integrative developmental care model: advanced clinical applications of the seven core measures for neuroprotective family-centered developmental care. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2016;16(4):230–244. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cameron S Ball I Cepinskas G Choong K Doherty TJ Ellis CG, et al. Early mobilization in the critical care unit: a review of adult and pediatric literature. J Crit Care. 2015;30(4):664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slomine BS McCarthy ML Ding R MacKenzie EJ Jaffe KM Aitken ME, et al. Health care utilization and needs after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e663–e674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]