Abstract

Vitamin D deficiency and elevated CRP (C-reactive protein) levels are independent indicators of risk for mortality in cancer survivors; however, their combined association with mortality has not been examined. This study included adult cancer survivors from four NHANES cycles (2003–2010), utilizing a multistage survey design. CRP levels were measured using a latex-enhanced turbidimetric assay, and serum 25(OH)D levels were assessed using RIA and LC–MS/MS methods. Mortality data were linked with the National Death Index up to 2019. The restricted cubic spline model was used to explore the nonlinear associations with mortality. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to examine survival curve differences. Cox analysis was employed to assess mortality risk after adjusting for confounding factors, and interaction analysis was conducted. Of the 1619 adult cancer survivors (56.9% female; weighted age 64.91 ± 0.44 years), 762 deaths were recorded during the 17-year follow-up. Higher CRP and lower 25(OH)D levels were associated with increased risks of all-cause and cancer mortality. Joint analysis revealed the High CRP and Low VID group had the highest all-cause (HR 2.40, 95% CI 1.82–3.17) and cancer (HR 5.23, 95% CI 3.15–8.70) mortality risk compared to Low CRP and High VID group. Additionally, a multiplicative interaction between serum 25(OH)D and CRP factors on cancer mortality was observed (P = 0.049), indicating a synergistic effect of these two factors on cancer mortality. Sex and ethnicity subgroup analyses revealed that the High CRP and Low VID group exhibits the highest risk for all-cause and cancer mortality, findings that are consistent with those observed in the overall population. In cancer survivors, an elevated risk of cancer and all-cause mortality is linked to vitamin D deficiency and elevated levels of CRP. In particular, the interaction between these factors may impact cancer survivors’ mortality related to cancers. Consequently, the risks may be significantly reduced through the use of anti-inflammatory medications as well as adequate intake of vitamin D.

Keywords: Vitamin D deficiency, C-reactive protein, Cancer mortality, Cancer survivors, NHANES

Subject terms: Chronic inflammation, Nutrition, Prognosis, Cancer

Introduction

According to demographic projections, the number of new cancer cases will exceed 35 million by 2050. Additionally, cancer survivors have emerged as a substantial demographic due to the ongoing development of medical technology. Consequently, it is highly critical to reduce the mortality rate of research for these survivors1. Despite the significant increase in the lifespan of cancer survivors due to modern medicine, the long-term prognosis for adult cancer survivors continues to be a persistent obstacle. As a result, it is imperative to create effective treatment strategies to enhance the survival rate of cancer survivors2.

Furthermore, researchers have discovered that cancer survivors have a high incidence of a variety of chronic diseases, including heart disease3, COPD4, diabetes5, and cognitive impairment6. The indicator of inflammatory activity, raised levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), is a distinctive characteristic of a variety of chronic diseases. CRP is an abnormal protein whose levels can either increase due to factors such as inflammation and infection or reflect physiological and cellular damage. A potential correlation between the prognosis of cancer patients and their CRP levels has been suggested by a multitude of studies7–9. A previous observational study7 indicates that the 5-year cancer-related mortality and overall survival of colorectal cancer patients experienced a significant decline in the elevated CRP level group. Thurner et al.8 identified elevated plasma CRP as a prognostic factor for poor survival in prostate cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. A poor prognosis correlates with increased CRP levels, and this association is unrelated to other prognostic indicators. Increased CRP levels were found to be positively correlated with the risk of mortality, morbidity, and distant metastasis in breast cancer patients in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) study’s data analysis9. This finding underscored inflammation as the primary etiological factor in those cancer survivors.

Vitamin D, a hormone-like compound, is crucial for the regulation of cell proliferation, immune function, and bone health, as discovered by Yu et al.10. Insufficient vitamin D levels have been related to an increased risk of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer, according to researchers. In addition, inferior cancer prognoses and longevity have been linked to vitamin D insufficiency. In a recent prospective investigation11, it was found that cancer survivors had lower risks of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer-related mortality when their serum 25(OH)D concentrations were elevated. The available evidence strongly supports the notion that vitamin D supplementation provides additional benefits beyond its impact on the skeletal system, notably in persons with insufficient vitamin D levels, autoimmune illnesses, and multiple sclerosis, with a focus on the immune system. Early study12 proved that inhibition of cellular proliferation is the main factor responsible for the anticancer effect of 1,25(OH)2D on thyroid cancers. In postmenopausal breast cancer patients in stages I-IIIa, Vrieling et al.13 discovered a correlation between serum 25(OH)D quantities and death from all causes and distant complications. Consequently, the development of tumors is closely correlated with vitamin D insufficiency, and numerous studies have demonstrated that a decline in cancer survivorship can result from low vitamin D levels. A previous review14 has summarized that vitamin D may inhibit cancer cell proliferation, promote cell apoptosis, and inhibit epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression through a variety of mechanisms. Furthermore, the quality of life and survival status of breast cancer patients are significantly influenced by vitamin D supplementation. In vitro experiments and clinical studies have demonstrated that vitamin D supplementation can enhance the quality of life of cancer patients, reduce the risk of complications, increase survival, and alleviate pain and other adverse effects.

Research has substantiated the strong correlation between vitamin D and inflammation. Bidirectional Mendelian randomization research15 demonstrates that the observed relationship between 25(OH)D and C-reactive protein (CRP) is likely due to Vitamin D insufficiency. Correcting low levels of Vitamin D may potentially decrease chronic inflammation. Previous research has demonstrated a relationship between elevated vitamin D levels and reduced C-reactive protein levels16. Vitamin D deficiency, along with inflammation, typically occurs concurrently in cancer survivors. The correlation between mortality and vitamin D and the amount of C-reactive protein has been separately investigated. However, the effect of the interaction between vitamin D and C-reactive protein on death rates among adult cancer survivors remains uncertain. Identifying the combined impact of vitamin D and C-reactive protein on mortality is critical for improving the prognosis of cancer survivors. This investigation evaluated the combined impact of vitamin D and C-reactive protein on mortality in adult cancer survivors in the United States. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 2003–2010) was employed in the investigation.

Materials and methods

Study participants

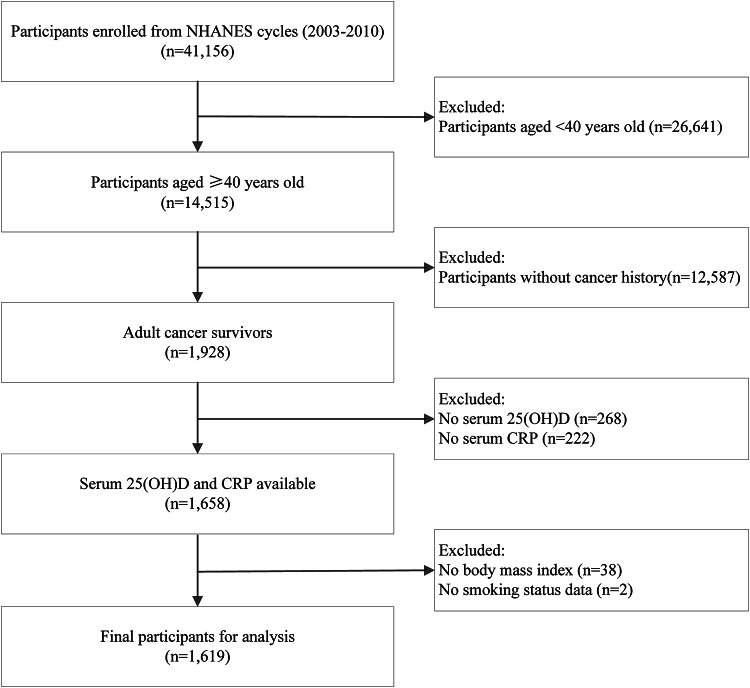

The study included adult cancer survivors, with data sourced from four NHANES cycles from 2003 to 2010. NHANES is a multistage, complex sampling design survey that assesses the health of U.S. residents. This survey is conducted on an ongoing basis by the National Centre for Health Statistics (NCHS) every two years. For detailed information regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the final study sample, please refer to Fig. 1. All participants provided informed consent, and the NCHS Ethics Review Board endorsed the survey protocols.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participants selection.

Measurement of 25(OH)D and CRP

A high-sensitivity latex-enhanced turbidimetric assay was employed to quantitatively measure CRP from blood samples. From 2003 to 2010, there were no changes in equipment, laboratory measurement methods, or laboratory locations. According to previous reference studies, CRP levels higher than 3 mg/L are considered indicative of elevated inflammation17. As for serum 25(OH)D, the data from NHANES 2003 to 2006 was measured using the radioimmunoassay (RIA) method. In subsequent NHANES investigations from 2007 to 2010, the more specific and sensitive liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) method was substituted for this method due to excessive method bias and imprecision at the time. NHANES 2003–2006 serum 25(OH)D data has been converted via regression to 25(OH)D measurements equivalent to those obtained by the LC–MS/MS method. According to guidelines, serum 25(OH)D levels below 50 nmol/L are considered indicative of vitamin D insufficiency18. Detailed descriptions of sample collection, processing, and laboratory methods are available on the NHANES official website.

Assessment of study outcomes

The mortality status and cause-specific death for each NHANES participant was assessed by linking NHANES with the National Death Index (NDI) up to December 31, 2019. The Worldwide Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) was applied to identify the cause-specific mortality, including cardiovascular mortality (I00–I09, I11, I13, I20–I51, and I60–I69) and cancer mortality (C00–C97). Only deaths where cancer is the primary cause of death are classified as cancer-related mortality, excluding those where cancer is mentioned but not the primary cause.

Other covariates

Demographic characteristics included age, sex, race, educational level, marital status, smoking, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity (PA). Comorbidities included self-reported hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 was defined as underweight, 18.5–25 kg/m2 as normal, 25–30 kg/m2 as overweight, and ≥ 30 kg/m2 as obesity. Physical activity was evaluated using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire, where < 150 min/week was defined as inactive and ≥ 150 min/week as active. Self-identified indications of coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke have been incorporated in the category of cardiovascular disease.

Statistical analysis

The “survey” R package was employed to weight all analyses in accordance with the NHANES statistical processing guidelines. Weighted means (SE) and counts (weighted %) were summarized for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. We used appropriate Rao-Scott chi-square and t-test to explore the relationship between socio-demographic, behavior, and comorbidity characteristics with serum 25(OH)D or CRP status. Cox models adjusted for potential confounders were employed to explore separate relationship between serum 25(OH)D or CRP status with mortality. Restricted cubic spline models were also utilized to investigate nonlinear associations between serum 25(OH)D or CRP status and mortality. Furthermore, we categorized the study sample into four groups based on elevated CRP and vitamin D deficiency status: Low CRP & High VID; Low VID only; High CRP only; High CRP & Low VID. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were employed to explore the combined effects of serum 25(OH)D and CRP status on mortality, using the Log-rank test for group comparisons. Cox models adjusted for confounders were also utilized to analyze the joint effect of serum 25(OH)D and CRP status on mortality. Additionally, the multiplicative interaction effect of the two factors on mortality was explored by incorporating an interaction term between the two factors in the models. The results of Model 1 (unadjusted), Model 2 (adjusted for age and sex), and Model 3 (adjusted for multiple variables) were demonstrated. We conducted a subgroup assessment, sorted by sex, to determine the combined influence on mortality within each sex subgroup. The R version 4.0.3 software was employed to perform every evaluation.

Results

Sample traits by serum 25(OH)D or CRP status

The flowchart depicting the complete study population inclusion process is shown in Fig. 1. Of the 1,619 participants (weighted age: 64.91 ± 0.44 years) in four NHANES cycles from 2003 to 2010, 56.9% were females, and 43.1% were males. Table 1 summarized the sample characteristics of subjects stratified by CRP levels, and Table 2 presented those by serum 25(OH)D deficiency status. Subjects with the elevated CRP levels were non-Hispanic Black (P = 0.003), less educated (P = 0.023), obesity (P < 0.001), ever/now smoking (P = 0.011), inactive (P = 0.002), and had higher potential for hypertension (P < 0.001), DM (P = 0.014), and cardiovascular disease (P = 0.017). A similar pattern was observed among participants with lower serum 25(OH)D levels, they tended to be female (P = 0.018), non-Hispanic Black/other races (P < 0.001), less educated (P = 0.001), widowed/divorced/separated (P < 0.001), obesity (P = 0.003), now smoking (P < 0.001), inactive (P < 0.001), and had higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by CRP status of adult cancer survivors (NHANES 2003–2010).

| Characteristics | Low CRP (n = 937) | High CRP (n = 682) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted number | 9,307,528 | 6,118,824 | |

| Age (years) | 65.03 ± 0.53 | 64.71 ± 0.63 | 0.670 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.067 | ||

| Female | 455 (54.6) | 374 (60.3) | |

| Male | 482 (45.4) | 308 (39.7) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.003 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 756 (90.9) | 492 (87.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 88 (3.6) | 109 (7.1) | |

| Mexican American/Hispanic | 22 (0.9) | 24 (1.6) | |

| Other | 71 (4.6) | 57 (4.3) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.023 | ||

| Less than high school | 223 (15.4) | 197 (20.9) | |

| High school and above | 714 (84.6) | 485 (79.1) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.227 | ||

| Married/with a partner | 610 (69.2) | 401 (64.3) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 292 (27.2) | 257 (32.3) | |

| Single | 35 (3.6) | 24 (3.4) | |

| Body mass index, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Normal | 311 (35.5) | 124 (18.1) | |

| Underweight | 21 (2.5) | 9 (1.0) | |

| Overweight | 388 (40.1) | 211 (29.8) | |

| Obesity | 217 (21.9) | 338 (51.1) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.011 | ||

| Never | 435 (47.4) | 269 (38.3) | |

| Ever | 391 (39.4) | 306 (44.7) | |

| Now | 111 (13.2) | 107 (17.0) | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 0.002 | ||

| Inactive | 644 (67.8) | 524 (77.2) | |

| Active | 293 (32.2) | 158 (22.8) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Absence | 433 (52.7) | 253 (40.9) | |

| Presence | 504 (47.3) | 429 (59.1) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.014 | ||

| Absence | 790 (87.6) | 534 (82.0) | |

| Presence | 147 (12.4) | 148 (18.0) | |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 0.017 | ||

| Absence | 705 (80.3) | 473 (74.9) | |

| Presence | 232 (19.7) | 209 (25.1) |

All continuous variables were presented as weighted mean and SE; all categorical variables were expressed as non-weighted numbers and weighted percentages. High CRP was defined as CRP ≥ 3 mg/L.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by serum 25(OH)D status of adult cancer survivors (NHANES 2003–2010).

| Characteristics | High serum 25(OH)D (n = 1208) | Low serum 25(OH)D (n = 411) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted number | 12,274,515 | 3,151,837 | |

| Age (years) | 65.04 ± 0.47 | 64.38 ± 0.95 | 0.511 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.018 | ||

| Female | 598 (55.1) | 231 (63.7) | |

| Male | 610 (44.9) | 180 (36.3) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1023 (93.0) | 225 (74.9) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 81 (2.6) | 116 (14.5) | |

| Mexican American/Hispanic | 31 (1.1) | 15 (1.6) | |

| Other | 73 (3.3) | 55 (9.0) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Less than high school | 280 (16.1) | 140 (23.7) | |

| High school and above | 928 (83.9) | 271 (76.3) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Married/with a partner | 792 (69.7) | 219 (57.7) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 371 (26.7) | 178 (39.2) | |

| Single | 45 (3.6) | 14 (3.1) | |

| Body mass index, n (%) | 0.003 | ||

| Normal | 346 (29.8) | 89 (23.8) | |

| Underweight | 21 (2.0) | 9 (1.6) | |

| Overweight | 466 (37.3) | 133 (31.2) | |

| Obesity | 375 (30.9) | 180 (43.4) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Never | 533 (44.6) | 171 (40.7) | |

| Ever | 554 (43.9) | 143 (32.3) | |

| Now | 121 (11.5) | 97 (27.0) | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Inactive | 825 (67.8) | 343 (86.1) | |

| Active | 383 (32.2) | 68 (13.9) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.489 | ||

| Absence | 529 (48.5) | 157 (46.0) | |

| Presence | 679 (51.5) | 254 (54.0) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.095 | ||

| Absence | 1011 (86.1) | 313 (82.4) | |

| Presence | 197 (13.9) | 98 (17.6) | |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Absence | 907 (80.0) | 271 (70.8) | |

| Presence | 301 (20.0) | 140 (29.2) |

All continuous variables were presented as weighted mean and SE; all categorical variables were expressed as non-weighted numbers and weighted percentages. Low serum 25(OH)D was defined as 25(OH)D < 50 nmol/L.

Establish a distinct correlation between serum 25(OH)D or CRP and mortality

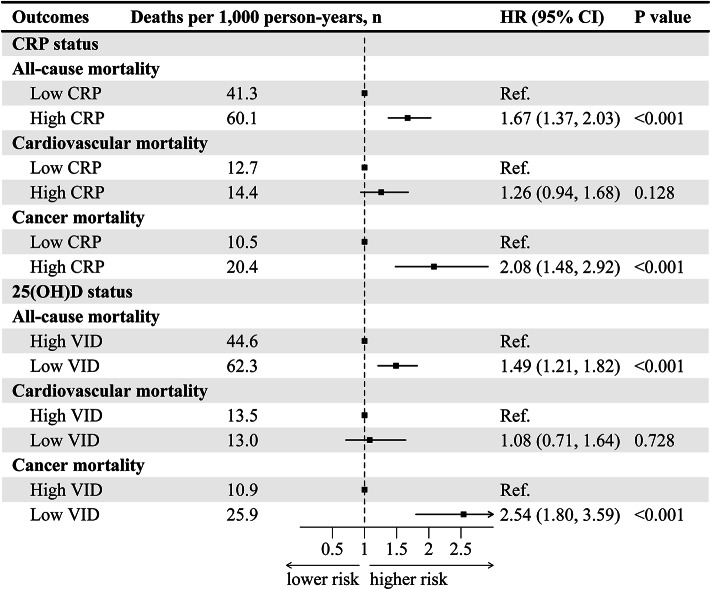

During a 17-year follow-up of study participants (median follow-up: 9.7 years), 762 deaths were recorded, with 209 deaths attributed to cardiovascular and 225 to cancer. After multivariable adjustment, the low CRP group was used as reference, the risk of all-cause (HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.37–2.03) and cancer (HR 2.08, 95% CI 1.48–2.92) mortality was positively correlated with a higher CRP level (Fig. 2). Compared to serum 25(OH)D sufficiency, the multivariable adjusted HRs for all-cause and cancer mortality in the serum 25(OH)D deficient group were 1.49 (95% CI 1.21–1.82) and 2.54 (95% CI 1.80–3.59) (Fig. 2). However, the relationship between serum 25(OH)D or CRP and cardiovascular mortality was not statistically significant. Results information for other models could be found in Table S1.

Fig. 2.

Separate effects on all-cause and cause-specific mortality by serum 25(OH)D or CRP status in adult cancer survivors (NHANES 2003–2010). The model adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, BMI, smoking, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular. HR (95% CI), hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval.

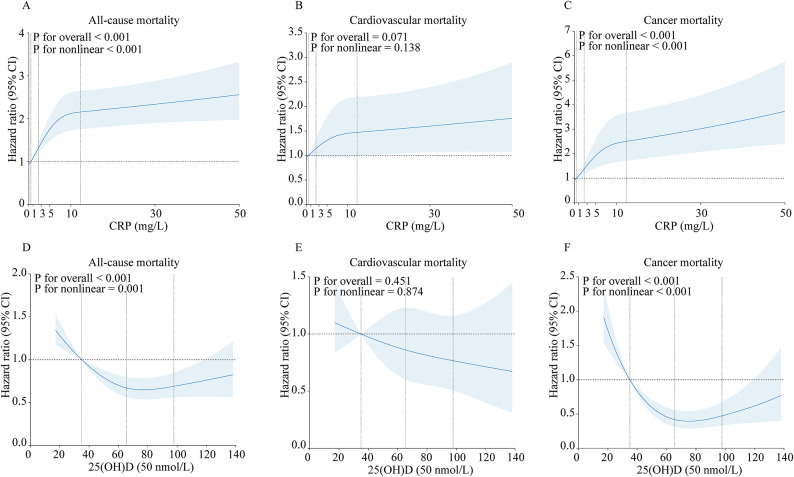

Results from the restricted cubic spline model indicate an L-shaped nonlinear association between serum 25(OH)D (P for overall < 0.001; P for nonlinear < 0.001) or CRP (P for overall < 0.001; P for nonlinear = 0.001) and all-cause mortality, with a similar L-shaped nonlinear association observed for cancer mortality with respect to serum 25(OH)D (P for overall < 0.001; P for nonlinear < 0.001) or CRP (P for overall < 0.001; P for nonlinear < 0.001) (Fig. 3). However, no association was found for cardiovascular mortality.

Fig. 3.

Nonlinear association of serum 25(OH)D and CRP with all-cause and cause-specific mortality based on restricted cubic spline model in adult cancer survivors (NHANES 2003–2010). The four vertical dashed lines represent the quartile values of serum 25(OH)D or CRP. A horizontal dashed line represents the reference line where hazard ratio equals 1.

A combined relationship between serum 25(OH)D and CRP and mortality

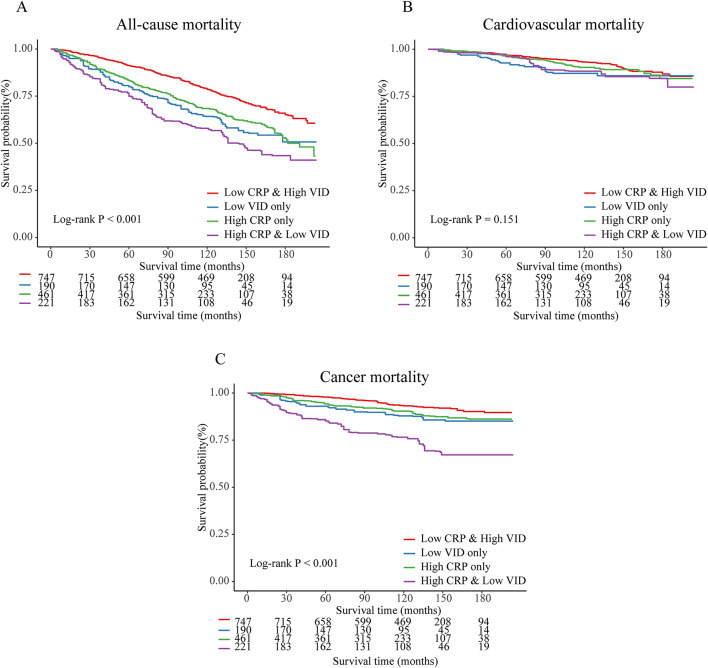

Kaplan–Meier analysis results show that the High CRP & Low VID group has the highest mortality rate, both for all-cause mortality and cancer mortality (Log-rank P < 0.05) (Fig. 4). However, for cardiovascular mortality, the survival curves among the four groups did not show statistically significant differences.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves illustrated the combined effects of serum 25(OH)D and CRP on all-cause and cause-specific mortality in adult cancer survivors (NHANES 2003–2010).

Figure 5 showed joint effects on mortality by serum 25(OH)D and CRP status adjusted for confounding, and the Low CRP & High VID group was set as reference. In the Low VID only group (HR 1.40, 95% CI 1.07–1.84), High CRP only group (HR 1.62, 95% CI 1.25–2.10), and High CRP & Low VID group (HR 2.40, 95% CI 1.82–3.17), the risk of all-cause mortality was increased. The High CRP only group (HR 1.62, 95% CI 1.02–2.56), and High CRP & Low VID group (HR 5.23, 95% CI 3.15–8.70) all exhibited an increased risk of cancer mortality. However, there was no statistically significant association between the combined effect of serum 25(OH)D and CRP and cardiovascular mortality. Results for other models were available in Table S2.

Fig. 5.

Joint effects on all-cause and cause-specific mortality by serum 25(OH)D and CRP status in adult cancer survivors (NHANES 2003–2010). The model adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, BMI, smoking, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular. HR (95% CI), hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval.

Through further interaction analysis, we found a multiplicative interaction between serum 25(OH)D and CRP factors with respect to cancer mortality (P = 0.049), indicating a synergistic effect of these two factors on cancer mortality (Fig. 5). No interaction effects were observed for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Subgroup analysis

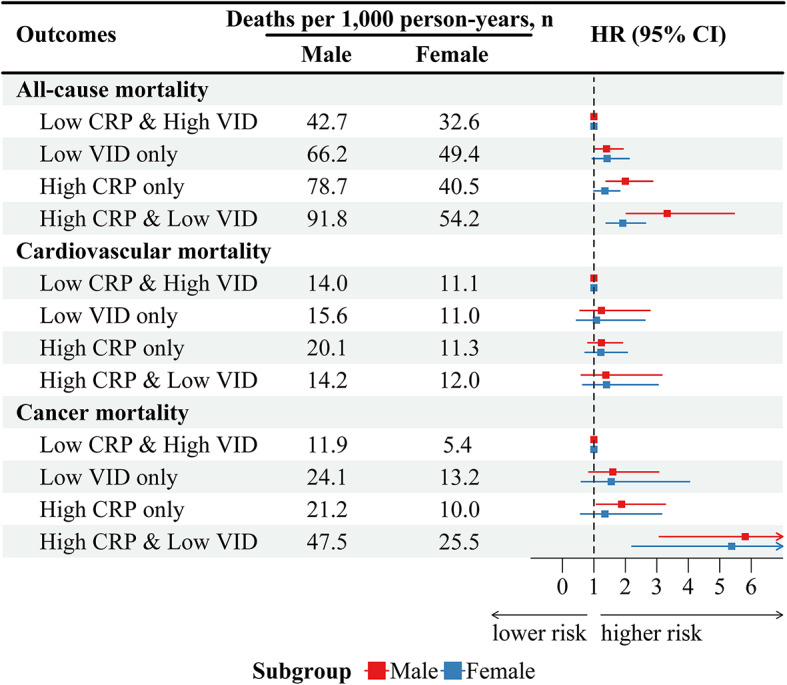

Figure 6 presented the association between serum 25(OH)D and CRP status and mortality, adjusted for confounding factors, across different sex subgroups. In both male and female subgroups, the High CRP and Low VID group had significantly highest risks of all-cause (male: HR 3.33, 95% CI 2.03–5.46; female: HR 1.92, 95% CI 1.39–2.64) and cancer (male: HR 5.81, 95% CI 3.08–10.95; female: HR 5.38, 95% CI 2.21–13.14) mortality compared to the Low CRP and High VID group. No statistical significance was found for cardiovascular mortality. Detailed information about the full adjusted model can be found in Table S3.

Fig. 6.

Sex-based subgroup analysis of joint effects on all-cause and cause-specific mortality by serum 25(OH)D and CRP status in adult cancer survivors (NHANES 2003–2010). The model adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, BMI, smoking, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular. HR (95% CI), hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval.

Table S4 illustrates the association between serum 25(OH)D and CRP status and mortality across different ethnicity subgroups, adjusted for confounding factors. Among Non-Hispanic White subgroup, the High CRP and Low VID group exhibited the highest risks of all-cause (HR 2.37, 95% CI 1.72–3.27) and cancer (HR 6.08, 95% CI 3.45–10.72) mortality compared to the Low CRP and High VID group. Similarly, the “Non-Hispanic Black or Mexican American/Hispanic or other” subgroup revealed increased risks of all-cause (HR 3.20, 95% CI 1.89–5.42), cardiovascular (HR 3.04, 95% CI 1.03–8.98), and cancer (HR 2.91, 95% CI 1.13–7.48) mortality in the High CRP and Low VID group compared to the Low CRP and High VID group.

Table S5 showed the association between serum 25(OH)D and CRP status and mortality across different cancer subgroups, adjusted for confounding factors. In the breast cancer subgroup, only Low 25(OH)D group exhibited significantly higher all-cause (HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.07–3.49) mortality risks compared to the Low CRP and High 25(OH)D group. However, in the prostate cancer subgroup, the High CRP and Low VID group showed increased risks of all-cause (HR 2.81, 95% CI 1.57–5.02) mortality compared to the Low CRP and High VID group. For the colorectal cancer subgroup, the High CRP and Low VID group had significantly higher risks of cancer (HR 15.82, 95% CI 2.4–104.2) mortality compared to the Low CRP and High VID group.

Discussion

This prospective cohort study aimed to investigate the combined influence of vitamin D and C-reactive protein on overall and cause-specific mortality. The progression of adult cancer survivors in the United States was monitored over a 17-year period by this investigation, which utilized a geographically representative sample. This study revealed both lower vitamin D levels and raised C-reactive protein levels were related to an increase in mortality. The combination of CRP and vitamin D significantly increased the risk of all-cause and specific mortality, demonstrating an interaction effect on cancer-specific mortality.

The correlation between the prevention of chronic diseases and vitamin D was previously established in an investigation19. Previous research has established the connection between a wide variety of chronic disorders, such as cancer20, bone mineral disease21, diabetes22 and cardiovascular disease, and the presence of vitamin D “deficiency” (defined as a circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D amount below 30 nmol/L). Subgroup analyses revealed that trials supplementing with vitamin D3 had a substantially lower all-cause mortality rate than those supplementing with vitamin D2. Data accumulation shows that vitamin D deficiency increases the incidence and mortality of chronic diseases in cancer survivors. Previous research23 has demonstrated a negative correlation between mortality and 25-hydroxy serum vitamin D levels (25(OH)D) in female with early breast cancer, as well as breast cancer recurrence risk. A case-cohort investigation24 conducted in the Pathways Study revealed an association between serum vitamin D levels and survival rates as well as survival without tumor progression in breast cancer patients. Particularly, patients with higher vitamin D levels exhibited improved survival without progression and general survival when contrasted with those with reduced vitamin D levels. Our research also verified a negative correlation between the quantity of vitamin D and all-cause or cancer-related death among cancer survivors, which is in line with prior research. In the 25(OH) D-deficient group, all-cause mortality and cancer mortality were 1.49-fold and 2.54-fold higher than in the 25(OH) D-sufficient group, respectively (Fig. 2). Men with digestive-system malignancies may have a higher risk of developing and dying from cancer if they have deficient levels of vitamin D, according to a prospective study25. Recent research26 shows that individuals with hypertension or limited sunlight exposure have an increased risk of overall deaths due to lower vitamin D intake. However, this risk decreases with increased vitamin D consumption, and ischemic stroke and pneumonia mortality also decrease. The variations in assessment methods, cutoff values, sources, and daily vitamin D supplements in these studies potentially influenced mortality from cancer, cardiovascular, without cancer/cardiovascular specific cause or all causes, which could account for the distinct associations between vitamin D and mortality. Vitamin D levels are closely related with chronic diseases, which are prevalent among cancer survivors. Our research confirms the inverse correlation between vitamin D levels and overall mortality and cancer-specific mortality in cancer survivors.

In two cohort studies24,27, elevated serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were negatively correlated to breast cancer prognosis and independently linked to improved outcomes, including overall survival. Females with elevated 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels exhibited a decreased risk of mortality from all causes compared to those with low levels, with a notably stronger association observed in premenopausal women. Elevated vitamin D levels have a positive correlation with improved breast cancer survival but a strong negative correlation with breast cancer risk, according to a meta-analysis28. Furthermore, prior research29 has demonstrated that vitamin D deficiency is prevalent among female breast cancer patients, and it is impossible to ameliorate this deficiency through vitamin D supplementation. The underlying mechanism may be attributed to the molecular actions of vitamin D in modulating the immune system and exerting anti-inflammatory effects. Vitamin D can suppress lymphocyte activation during immune responses, thereby reducing the incidence of tumors and autoimmune diseases. Additionally, vitamin D enhances the cytotoxicity and activity of natural killer (NK) cells, aiding the immune system in eliminating malignant cells and infectious microorganisms. Furthermore, vitamin D regulates the activity and differentiation of T and B lymphocytes, thereby enhancing the body’s capacity for immune and anti-inflammatory responses. Beyond its role in inflammation, vitamin D can regulate inflammatory responses through multiple mechanisms. Firstly, it inhibits inflammation-related pathways by modulating the concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Secondly, vitamin D can mitigate the risk of tumor growth and metastasis by preventing inflammation-induced vascular changes. Moreover, vitamin D can inhibit fibrogenesis and tissue destruction during inflammatory responses, thereby reducing organ damage. Previous research30 has shown that the vitamin D receptor (VDR) can be genetically modulated in breast cancer. As well the vitamin D receptor (VDR) is an essential transcriptional regulator of autophagy. VDR stimulates autophagy and autophagic transcriptional profiles in breast cancer cells, leading to improved patient survival31. VDR belongs to class II of the nuclear receptor superfamily, functions as a ligand-dependent transcription factor. It mediates the biological activities of active vitamin D, thereby regulating cell growth and differentiation in both healthy and cancerous breast tissues. VDR demonstrates anti-proliferative properties and can form heterodimers with retinoid X receptor (RXR), thyroid hormone receptor (THR), or retinoic acid receptor (RAR). In summary, vitamin D plays a crucial role in immune regulation and inflammatory responses. It modulates immune system development and inflammatory processes via various mechanisms, thereby impacting overall health. Supplementation with vitamin D can help reduce inflammatory responses, lower the incidence of autoimmune diseases, and improve immune function and control of inflammatory responses. All of these factors led to the conclusion that vitamin D therapy may have a big effect on how well breast cancer patients respond to their treatments, leading to a lower death rate and better overall free survival (OFS) and disease-free survival (DFS)32.

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a type of tyrosine secretion frequently referenced as an indicator of inflammation in the body. Numerous factors contribute to the tumor’s complexity, including genetics, environmental factors, and lifestyle. The incidence of inflammation is particularly high among cancer survivors. The correlation between CRP and the mortality rate of cancer survivors is substantiated by existing research. A randomization investigation33 demonstrated that an elevated CRP level was linked to an elevated risk of depression in the entire population. Predictors of cancer, future CVD, and deaths in the overall population are initial and subsequent increases in CRP levels, according to two prospective observational cohorts34. In a current multicenter study, it was determined that patients with ovarian cancer had a lower survival rate when their CRP levels were elevated35. A study conducted by the UK Biobank36 revealed a positive correlation between CRP levels and several health conditions, such as tongue cancer, bronchitis, hydronephrosis, and acute pancreatitis. Conversely, a negative correlation was shown between CRP levels and colorectal cancer, colon cancer, and neurological illnesses. Furthermore, our investigation confirmed a link between elevated CRP levels and a 1.67-fold increase in all-cause deaths and a 2.08-fold increase in cancer-related deaths among cancer survivors. In colorectal cancer patients, plasma CRP levels are indicative of survival, as discovered by Yamamoto et al.37. Patients with high CRP levels may have an excessive internal inflammatory response, leading to a poor prognosis. This could result in a decrease in their survival rate. Furthermore, elevated CRP levels may influence patients’ prognoses due to their tumor size, stage, lymphatic metastasis, and distant metastasis. Observational investigations38 revealed a positive correlation between higher CRP concentrations and an elevated risk of developing cancer in general. This correlation was shown to be significant when the CRP concentration reached a threshold of 3 mg/L. Certain psychological factors, such as elderly people’s self-awareness, can influence and facilitate the inflammatory response. In individuals who have metastatic breast cancer, an elevated serum CRP level is a predictor of a poor prognosis, as evidenced by a meta-analysis39. More consistent findings in metastatic patients indicate that elevated serum CRP levels increase the hazard ratio for overall survival by nearly twofold. Also, we observed a positive association between CRP levels and death due to cancer among cancer survivors in our study. This correlation may be attributed to CRP’s role in predicting an increased likelihood of the body developing cancer diseases. Additional investigation is required to determine the mechanisms that underlie these phenomena. In cancer survivors, we discovered a negative correlation between all-cause or cancer-specific mortality and the C-reactive protein level. Vitamin D and C-reactive protein may serve as indicators of cancer survivors’ mortality, as well as their prognosis and treatment. This implies the need for routine screening of cancer survivors for these parameters.

Additionally, our research demonstrated that cancer survivors who had elevated C-reactive protein and vitamin D insufficiency were at a substantially increased risk of cancer-related mortality and all-cause death. In cancer survivors, vitamin D is linked to the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein (CRP). Several investigations have previously investigated the relationship between inflammation and vitamin D in cancer survivors. Specifically, insufficient vitamin D levels can lead to an increase in CRP, which affects the prognosis of cancer. This may be attributed to the immune system’s dysfunction, which is exacerbated by vitamin D deficiency, thereby increasing the risk of tumorigenesis and inflammatory response. To combat infection, vitamin D can modulate growth factors and anti-inflammatory cells, as well as the immune system40–42. Vitamin D is a crucial cell activator of muscle protein that plays a significant function in biological processes, including inflammation43–45. Additionally, research has demonstrated that deficiencies in vitamin D may result in elevated inflammatory responses and an elevated incidence of cancer. According to research46, vitamin D inadequacy may worsen the disease process and increase the severity of the inflammatory response in patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings suggest that vitamin D may be a substantial factor in the treatment and prevention of COVID-19 disease. Vitamin D supplements may assist in the reduction of inflammation and the enhancement of immune system function, thereby reducing the incidence of cancer, from the perspective of dietary supplements. However, to determine the optimal timing and specific dose of vitamin D supplementation for cancer prevention, additional large-scale randomized controlled efficacy trials are necessary. This would facilitate the reduction of cancer and all-cause mortality among cancer survivors. Consequently, our research has verified that the risk of all-cause mortality is nearly three times higher in individuals with vitamin D inadequacy and an elevated CRP level, with a cancer-related mortality risk exceeding five times that of cancer survivors.

Additionally, our investigation revealed that cancer survivors who displayed elevated CRP levels and low vitamin D levels were at a significantly increased risk of all-cause death, particularly cancer-related death rates, in comparison to those who exhibited either high CRP levels or low vitamin D levels, respectively. Vitamin D content was initially evaluated for bone disease. Currently, the increasing number of studies establishing a relation between vitamin D quantity and human inflammatory response and immune activities is influencing the prognosis and efficacy of cancer patients. Vitamin D’s capacity to regulate chronic inflammatory diseases at the molecular level has been recently demonstrated by research, further emphasizing the intimate connection between the antioxidant vitamin D and the inflammatory response. There is a substantial prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy among individuals who have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), as indicated by recent research47,48. Additionally, there is a correlation between low serum levels of vitamin D and the development of disease conditions. Research has shown that the activation of vitamin D signaling mechanisms enhances the integrity of the epithelial barrier and gastrointestinal microbiome, modulates the production of various junctional proteins, including defensins and mucins, and impacts the response to inflammation. 1,25(OH)2D regulates proinflammatory cytokines on both the genomic and functional levels, according to a mechanism study48,49. It inhibits the expression of TNFα and IFNγ by competing with NFAT1 and utilising a vitamin D response element (VDRE) in its promoter, respectively. 1,25(OH)2D inhibits NFκB activation by increasing IκBα expression, thereby preventing the genomic activation of proinflammatory genes such as IL-8 and IL-12. Vitamin D receptors are extensively expressed in the cardiomyocytes of animal models and are implicated in numerous chronic diseases, including cardiac fibrosis. Hypertension can be attributed to endothelial dysfunction, with renin–angiotensin–aldosterone (RAAS) activation being one potential mechanism. Consensus research50 indicates that global VDR knockout rodents develop cardiac hypertrophy and elevated blood pressure due to increased renin expression and subsequent RAAS activation. An increasing body of evidence51–53 indicated a negative correlation between levels of 25-(OH)D and blood pressure. This study’s most remarkable finding is that both low vitamin D levels and elevated CRP levels exacerbate the risk of cancer-related mortality. This phenomenon has never been investigated in prior investigations. Vitamin D deficiency may elevate the probability of an inflammatory response, while vitamin D supplementation may mitigate inflammation, according to prior research54,55. The immune response may be regulated; the antioxidant effect; and the production of anti-inflammatory active substances, such as antioxidants, may be the mechanism by which vitamin D is generated. Nevertheless, there are only a handful of studies that have previously observed the combination of CRP and vitamin D. As a result, tumor survivors who have elevated CRP, an inflammatory marker, may be vitamin D deficient. Furthermore, it is noteworthy to note that the risk of cancer-related mortality was increased in our study due to a lack of vitamin D and raised CRP levels, which were contributing factors to the interaction. Cancer survivors with insufficient vitamin D and CRP levels faced elevated hazards of all-cause mortality and cancer-related mortality. Inadequate vitamin D and elevated CRP levels are prevalent among tumor survivors. Despite the absence of research on the joint effect of CRP and vitamin D on fatality in cancer survivors, the public health community widely acknowledges the significance of inflammation and vitamin D. At first, our research emphasized how important critical nodes are because they are linked to the higher risk of death among cancer survivors who are low on vitamin D and high on CRP, rather than just the effect of low vitamin D or high CRP, respectively. It is advised that public health and management strategies for cancer survivors include the evaluation of vitamin D and CRP levels, as shown by the evidence presented in this study. Aggressive intervention strategies may reduce the risk of mortality and enhance long-term survival among cancer survivors by detecting chronic inflammation and vitamin D insufficiency early. It is crucial to be aware of the possible risks linked to over-supplementation of vitamin D, including conditions like hypercalcemia that may result in negative health impacts. To achieve the best patient outcomes, it is essential to maintain a balance in vitamin D supplementation coupled with diligent monitoring. Excessive vitamin D may adversely affect results in cancer survivors; hence, appropriate vitamin D dosage is crucial.

This research may be subject to several limitations. One potential limitation is residual confounding, since the publicly available dataset lacks a complete array of confounding variables. This might limit our capacity to fully account for all factors influencing the observed relationships. Furthermore, the results might not be entirely applicable to populations beyond the United States, owing to variations in eating patterns, healthcare structures, and other socio-cultural elements. Given the restricted sample size, the findings pertaining to specific cancer subgroups might lack stability. Future studies may require larger samples to investigate the collective influence of these factors on mortality within particular types of cancer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study revealed that cancer survivors with insufficient vitamin D levels and elevated CRP are at a higher risk for both all-cause and cancer-specific mortality. These results underscore the significance of timely identification and management of vitamin D deficiency and inflammation in individuals who have survived cancer. Addressing elevated CRP levels alongside insufficient vitamin D could carry substantial implications for public health. We suggest evaluating the use of anti-inflammatory therapies and vitamin D supplementation, encompassing both oral intake and dietary options, as potential approaches to decrease mortality in this group. To solidify these findings and develop more definitive clinical recommendations, it is crucial to conduct randomized controlled trials.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We express gratitude to the NHANES administration for providing related data accessible through the NHANES website.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z., X.C., and X.S.; Data curation, H.Z., X.C., and X.S.; Formal analysis, H.Z.; Investigation, H.Z., X.C., and X.S.; Methodology, H.Z., X.C., and X.S.; Project administration, resources & software, H.Z.; Supervision, H.Z., B.D., X.C., and X.S.; Validation, H.Z., B.D., X.C., and X.S.; Visualization, H.Z.; Writing-original draft preparation, H.Z., X.C., and X.S.; Writing-review and editing, H.Z., B.D., X.C., and X.S.

Data availability

Analytical data discussed in this manuscript are publicly accessible on the NHANES website [https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm], and upon request, the analytical data will be provided, subject to application by the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The survey protocol received approval from the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board, as documented at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm. All participants provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

XiaoDi Sun, Email: xdsun86@cmu.edu.cn.

XiTao Chen, Email: chenxt@cmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-95931-w.

References

- 1.Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.74(3), 229–263 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen, R. E. et al. United States population-based estimates of patient-reported outcomes measurement information system symptom and functional status reference values for individuals with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.35(17), 1913–1920 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueno, K. et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease in cancer survivors. J. Cachexia. Sarcopenia Muscle15(3), 1062–1071 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leuzzi, G. et al. C-reactive protein level predicts mortality in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev.26(143), 160070 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storey, S. et al. Association of comorbid diabetes with clinical outcomes and healthcare utilization in colorectal cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum48(2), 195–206 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regier, N. G. et al. Cancer-related cognitive impairment and associated factors in a sample of older male oral-digestive cancer survivors. Psychooncology28(7), 1551–1558 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park, J. H., Watt, D. G., Roxburgh, C. S., Horgan, P. G. & McMillan, D. C. Colorectal cancer, systemic inflammation, and outcome: staging the tumor and staging the host. Ann. Surg.263(2), 326–336 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thurner, E. M. et al. The elevated C-reactive protein level is associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990)51(5), 610–619 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villaseñor, A. et al. Postdiagnosis C-reactive protein and breast cancer survivorship: findings from the WHEL study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.23(1), 189–199 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu, Y. et al. Joint association of sedentary behavior and vitamin D status with mortality among cancer survivors. BMC Med.21(1), 411 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mo, X. et al. Association of serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D concentration and risk of mortality in cancer survivors in the United States. BMC Cancer24(1), 545 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinckspoor, I. et al. Vitamin D in thyroid tumorigenesis and development. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem.48(2), 65–98 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vrieling, A. et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and postmenopausal breast cancer survival: Influence of tumor characteristics and lifestyle factors?. Int. J. Cancer134(12), 2972–2983 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hines, S. L., Jorn, H. K., Thompson, K. M. & Larson, J. M. Breast cancer survivors and vitamin D: a review. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif)26(3), 255–262 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou, A. & Hyppönen, E. Vitamin D deficiency and C-reactive protein: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Epidemiol.52(1), 260–271 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liefaard, M. C. et al. Vitamin D and C-reactive protein: A Mendelian randomization study. PLoS ONE10(7), e0131740 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu, X., Hall, J., Byles, J. & Shi, Z. Dietary pattern, serum magnesium, ferritin, C-reactive protein and anaemia among older people. Clin. Nutr. (Edinburgh, Scotland)36(2), 444–451 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertoldo, F. et al. Definition, assessment, and management of vitamin D inadequacy: Suggestions, recommendations, and warnings from the italian society for osteoporosis, mineral metabolism and bone diseases (SIOMMMS). Nutrients14(19), 4148 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welsh, P. & Sattar, N. Vitamin D and chronic disease prevention. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed)348, g2280 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giampazolias, E. et al. Vitamin D regulates microbiome-dependent cancer immunity. Science (New York, NY).384(6694), 428–437 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battaglia, Y. et al. Bone mineral density changes in long-term kidney transplant recipients: a real-life cohort study of native vitamin D supplementation. Nutrients14(2), 323 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cojic, M., Kocic, R., Klisic, A. & Kocic, G. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic and oxidative stress markers in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 6-month follow up randomized controlled study. Front. Endocrinol.12, 610893 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao, T., Klein, P. & Grossbard, M. L. Vitamin D and breast cancer. Oncologist17(1), 36–45 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao, S. et al. Association of serum level of vitamin D at diagnosis with breast cancer survival: a case-cohort analysis in the pathways study. JAMA Oncol.3(3), 351–357 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giovannucci, E. et al. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J. Natl Cancer Inst.98(7), 451–459 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanri, A. et al. Vitamin D intake and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Japanese men and women: the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. Eur. J. Epidemiol.38(3), 291–300 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almeida-Filho, B. S. et al. Negative impact of vitamin D deficiency at diagnosis on breast cancer survival: a prospective cohort study. Breast J.2022(1), 4625233 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, Y. & Je, Y. Vitamin D intake, blood 25(OH)D levels, and breast cancer risk or mortality: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer110(11), 2772–2784 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crew, K. D. et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency despite supplementation in premenopausal women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol.27(13), 2151–2156 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ditsch, N. et al. The association between vitamin D receptor expression and prolonged overall survival in breast cancer. J. Histochem. Cytochem.60(2), 121–129 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isbilen, E., Kus, T., Cinkir, H. Y., Aktas, G. & Buyukbebeci, A. Better survival associated with successful vitamin D supplementation in non-metastatic breast cancer survivors. Turk. J. Biochem.46(5), 509–516 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavera-Mendoza, L. E. et al. Vitamin D receptor regulates autophagy in the normal mammary gland and in luminal breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.114(11), E2186-e2194 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wium-Andersen, M. K., Orsted, D. D. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Elevated C-reactive protein, depression, somatic diseases, and all-cause mortality: a mendelian randomization study. Biol. Psychiat.76(3), 249–257 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suthahar, N. et al. Association of initial and longitudinal changes in C-reactive protein with the risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality. Mayo Clin. Proc.98(4), 549–558 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peres, L. C. et al. High levels of C-reactive protein are associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer: results from the ovarian cancer cohort consortium. Can. Res.79(20), 5442–5451 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Si, S., Li, J., Tewara, M. A. & Xue, F. Genetically determined chronic low-grade inflammation and hundreds of health outcomes in the UK Biobank and the FinnGen population: a phenome-wide mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol.12, 720876 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto, T., Kawada, K. & Obama, K. Inflammation-related biomarkers for the prediction of prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22(15), 8002 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu, M. et al. C-reactive protein and cancer risk: a pan-cancer study of prospective cohort and Mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Med.20(1), 301 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikkelsen, M. K. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of C-reactive protein as a biomarker in breast cancer. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci.59(7), 480–500 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen, L. S. et al. Pre-treatment serum vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased inflammatory biomarkers and short overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990).144, 72–80 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gwenzi, T. et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on inflammatory response in patients with cancer and precancerous lesions: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin. Nutr. (Edinburgh, Scotland)42(7), 1142–1150 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sha, S., Gwenzi, T., Chen, L. J., Brenner, H. & Schöttker, B. About the associations of vitamin D deficiency and biomarkers of systemic inflammatory response with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a general population sample of almost 400,000 UK Biobank participants. Eur. J. Epidemiol.38(9), 957–971 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeon, S. M. & Shin, E. A. Exploring vitamin D metabolism and function in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med.50(4), 1–14 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manson, J. E. et al. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med.380(1), 33–44 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang, Y. et al. Association between vitamin D supplementation and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.)366, l4673 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ünsal, Y. A. et al. Retrospective analysis of vitamin D status on ınflammatory markers and course of the disease in patients with COVID-19 infection. J. Endocrinol. Investig.44(12), 2601–2607 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gubatan, J., Chou, N. D., Nielsen, O. H. & Moss, A. C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: association of vitamin D status with clinical outcomes in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.50(11–12), 1146–1158 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu, W., Yan, J., Zhi, C., Zhou, Q. & Yuan, X. 1,25(OH)(2)D(3) deficiency-induced gut microbial dysbiosis degrades the colonic mucus barrier in Cyp27b1 knockout mouse model. Gut Pathogens11, 8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kloc, M. et al. Effects of vitamin D on macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) hyperinflammatory response in the lungs of COVID-19 patients. Cell. Immunol.360, 104259 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li, Y. C. et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J. Clin. Investig.110(2), 229–238 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Judd, S. E., Nanes, M. S., Ziegler, T. R., Wilson, P. W. & Tangpricha, V. Optimal vitamin D status attenuates the age-associated increase in systolic blood pressure in white Americans: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.87(1), 136–141 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, T. J. et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation117(4), 503–511 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ke, L. et al. Hypertension, pulse, and other cardiovascular risk factors and vitamin D status in Finnish men. Am. J. Hypertens.26(8), 951–956 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miao, J. et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular and glycemic biomarkers. J. Am. Heart Assoc.10(10), e017727 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krajewska, M. et al. Vitamin D effects on selected anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory markers of obesity-related chronic inflammation. Front. Endocrinol.13, 920340 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Analytical data discussed in this manuscript are publicly accessible on the NHANES website [https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm], and upon request, the analytical data will be provided, subject to application by the corresponding author.