Abstract

The study observed interactions between gut microbiota and male reproductive health, noting that the causal relationships were previously unclear. It aimed to explore the potential cause-and-effect relationship between gut bacteria and male reproductive problems such as inflammation, infertility, and sperm functionality, using a two-sample Mendelian randomization method to examine these connections. The analysis found that certain bacterial genera, such as Erysipelatoclostridium (0.71 [0.55–0.92]), Parasutterella (0.74 [0.57–0.96]), Ruminococcaceae UCG-009 (0.77 [0.60–0.98]), and Slackia (0.69 [0.49–0.96]), showed protective effects against prostatitis. In contrast, other genera like Faecalibacterium (1.59 [1.08–2.34]), Lachnospiraceae UCG004 (1.64 [1.15–2.34]), Odoribacter (1.68 [1.01–2.81]), Paraprevotella (1.28 [1.03–1.60]), and Sutterella (1.58 [1.13–2.19]) were detrimental. Additionally, causal relationships were identified between 2 genera and orchitis and epididymitis, 3 genera and male infertility, and 5 genera and abnormal spermatozoa. Further analysis of sperm-related proteins revealed causal associations between specific bacterial genera and proteins such as SPACA3, SPACA7, SPAG11A, SPAG11B, SPATA9, SPATA20, and ZPBP4. The results remained robust after sensitivity analysis and reverse Mendelian randomization analysis. The study concluded that specific bacterial genera have causal roles in reproductive inflammation, infertility, and sperm-associated proteins. This provides a novel strategy for the early diagnosis and identification of therapeutic targets in reproductive inflammation and infertility.

Keywords: gut microbiota, infertility, Mendelian randomization, prostatitis, sperm-related proteins

1. Introduction

Globally, 8% to 12% of couples experience infertility, with male factors contributing to 30% to 50% of cases.[1] A global survey reported that between 1990 and 2017, male infertility rates increased annually by 0.291%.[2] The causes of male infertility are diverse, ranging from congenital issues like chromosomal abnormalities to acquired conditions like prostatitis and orchitis, all of which can affect sperm production.[3] Sperm undergo a series of biochemical reactions involving genetic and protein substances. Poor biochemical combinations are linked to sperm abnormalities such as low count, poor motility, and abnormal morphology.[4–6] These abnormalities highlight the complex interplay of metabolic and genetic factors in male reproductive health.

The human gut hosts trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites.[7] This ecosystem plays a crucial role in various bodily functions, such as digestion, metabolism, and inflammation, by influencing endocrine, neural, and immune pathways.[8,9] Evidence suggests a close connection between gut microbiota composition and the reproductive system.[10,11] The gut microbiome impacts the male reproductive system through mechanisms like metabolic byproducts, spermatogenesis, and hormonal regulation.[12] It also affects reproductive functions by interacting with the immune and nervous systems, influencing the prostate environment and sperm quality.[13,14] Disruption of gut flora can worsen these immune issues, leading to systemic inflammation and reproductive problems.[15,16] Understanding this relationship across different individuals and conditions is vital for improving male reproductive health. Early prevention, potentially through specific probiotics, offers promising avenues for enhancing health and preventing fertility-related issues.

Previous studies have suggested the gut microbiota as a novel biomarker for predicting and preventing infertility. However, many rely on observational data or case-control designs, which are prone to confounding factors like diet, age, and mental state. This complexity hinders strong causal inferences about the role of gut microbiota in male reproductive health. Mendelian randomization (MR) offers a solution by using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to assess the causal relationship between exposures (such as changes in gut biota) and reproductive outcomes (such as proteins, inflammation, and sperm abnormalities), reducing the risk of confounding.[12] The random allocation of genotypes at conception strengthens the credibility of causal inferences.[17] MR has been used successfully in studies exploring the causal links between gut microbiota and diseases like immune and endocrine disorders.[18,19] In this study, we used the latest genome-wide association studies data to conduct a two-sample MR analysis. Our goal was to determine if assessing gut microbiome abundance in male reproductive health and infertility can establish new standards and provide more effective preventive or therapeutic interventions for these common male health issues.

2. Method

2.1. Source of gut microbiome and outcome data

Genetic variations in the gut microbiome were discovered in a large-scale association study involving 24 cohorts with 18,340 participants.[20] Among them, 20 cohorts consisted of samples of single ancestry, with the majority of participants (16 cohorts, N = 13,266) being of European descent. The microbiota quantitative trait locus mapping study for each queue only included taxa present in > 10% of samples, totaling 211 taxa (131 genera, 35 families, 20 orders, 16 classes, and 9 phyla). For better practical application, only genus level data were analyzed, and 12 genera that were not clearly named were excluded, ultimately resulting in the inclusion of 119 classified genera.[7] Primary data regarding male reproductive inflammation (prostatitis, orchitis, and epididymitis) and infertility (abnormal spermatozoa and male infertility) were mainly derived from the FinnGen database. Proteins associated with sperm formation were sourced from the genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome.[21] Additionally, for convenient analysis and data collation and extraction, we acquired the resultant GWAS data directly from the OPEN GWAS website (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). Detailed information regarding the collected data, which includes ID numbers, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and sample sizes, is provided (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O792).

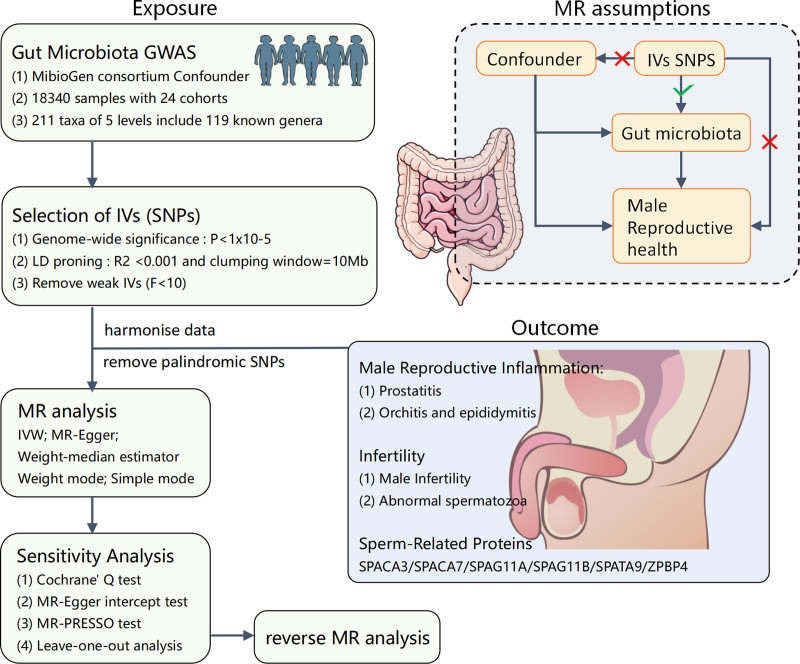

2.2. Study design

The overall structure of the study is illustrated in Figure 1. We utilized the two-sample MR method to probe the causal association between the entities of the gut microbiome and male reproductive health. To mitigate biases influencing the results maximally, we strived to fulfill 3 crucial assumptions while employing the MR method.[22] First, the relevance assumption stipulates a robust and strong correlation between the IVs and the exposure. Second, the independence assumption posits that IVs should be independent of the confounding factors influencing the “exposure-outcome” relationship. Last, the exclusion restriction assumption asserts that genetic variations can only influence the outcome through the exposure and should not affect the outcome via any alternative pathways.

Figure 1.

Study design and workflow. GWAS = genome-wide association studies; IVs = instrumental variables; IVW = inverse-variance weighting; MR = Mendelian randomization; SNPs = single nucleotide polymorphisms.

2.3. Ethics statement

Since the data used in this study were ethically approved in their initial research, no additional ethical permission was required for this study.

2.4. Criteria for IV selection

Priority is given to SNPs associated with each genus at the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 1.0 × 10⁻⁵) as potential strong IVs.[23] To mitigate the bias from weak instruments, the strength of IVs is quantified using the formula F = β²_exposure/SE²_exposure,[24,25] excluding variables with an F-statistic below 10.[26] Furthermore, by setting the R² threshold to 0.001 and maintaining a genetic distance of 10 Mb, variable independence is ensured, and the effect of linkage disequilibrium is reduced. Last, SNPs with minor allele frequencies ≤ 0.01 or those that were palindromic or ambiguous were excluded.

2.5. MR analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.2.3, utilizing the “MR-PRESSO” and “TwoSampleMR” packages.

To investigate causal relationships between exposures and outcomes, we employed a series of methods, including inverse-variance weighting (IVW), MR Egger, weighted median, weighted mode, and simple mode.[27–29] Notably, if inconsistent results were yielded by these methods, the results from the IVW method were considered the primary method. The IVW method is slightly superior under certain conditions compared to other methods.[29] It consolidates Wald ratio estimates from each SNP into a single causal estimate for each hazard ratio, each obtained by dividing the SNP-outcome association by the SNP-exposure association.[30] MR–Egger generally complies with the instrument strength independent of direct effect assumption and accommodates pleiotropy to some extent, reflecting the dose–response relationship between IV and outcomes.[28,31] The weighted median method maximally reduces Type-1 error and allows some invalid genetic variations.[29] Weighted mode and simple mode methods remain reliable when the majority of IVs satisfying causal inference criteria have similar causal estimates. The causal relationships between gut microbiota and diseases are described using odds ratios (ORs) [95% confidence intervals (CIs)]; causal relations with sperm-related proteins are expressed using β [95% CI].[32,33] To enhance the reliability of the results, a series of sensitivity analyses were also performed. Cochran Q test was used to evaluate heterogeneity between IVs, and leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was utilized to assess the impact of outliers on the stability of the results. The presence of horizontal pleiotropy can challenge the second MR assumption; hence, various methods were employed for its detection. Specifically, MR–Egger intercept test and MR-PRESSO global test assessed the presence of horizontal pleiotropy.[34,35] The MR-PRESSO method further adjusted for pleiotropy by identifying and removing outliers, setting permutation counts at 1000 for the analysis.[36,37]

To ascertain the existence of bidirectional causal relationships, reverse MR analyses were conducted. In this context, male reproductive tract inflammation, infertility, and sperm-related proteins were treated as exposures, with corresponding SNPs serving as IVs, and identified pathogenic genera were considered outcomes.

3. Result

3.1. Selection of SNPs

IVs were selected using strict criteria: genome-wide significance (P < 1.0 × 10⁻⁵), linkage disequilibrium, validation by F-statistics, and exclusion of palindromic or ambiguous sequences. All IVs had F-statistics well above the threshold of 10, ensuring they were strong and reliable for their associated bacterial taxa (Table S2, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O792).

3.2. Male reproductive inflammation

3.2.1. Prostatitis

Nine bacterial genera have been linked to prostatitis (IVW-P < .05). Erysipelatoclostridium, Parasutterella, Ruminococcaceae UCG-009, and Slackia appear to have protective effects with ORs of 0.71 [0.55–0.92], 0.74 [0.57–0.96], 0.77 [0.60–0.98], and 0.69 [0.49–0.96], respectively. In contrast, Faecalibacterium (1.59 [1.08–2.34]), Lachnospiraceae UCG004 (1.64 [1.15–2.34]), Odoribacter (1.68 [1.01–2.81]), Paraprevotella (1.28 [1.03–1.60]), and Sutterella (1.58 [1.13–2.19]) are identified as risk factors for prostatitis (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

MR results of causal links between gut microbiome and inflammation of the male reproductive inflammation and infertility. CI = confidence intervals; IVW = inverse-variance weighting; OR = odds ratios; SNPs = single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of the causal association between gut microbiome and prostatitis. SNPs = single nucleotide polymorphisms.

3.2.2. Orchitis and epididymitis

Two bacterial genera, Eubacterium (ruminantium group) and Ruminococcaceae UCG009, have been identified as protective factors against orchitis and epididymitis, showing values of 0.74 [0.58–0.93] and 0.68 [0.51–0.91], respectively (P = .01) (Fig. 2; Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O793).

3.3. Infertility

3.3.1. Male infertility

Three bacterial genera have been linked to male infertility (IVW-P < .05). Eubacterium (rectale group) was associated with a reduced risk (0.31 [0.15–0.64]), while Eubacterium (oxidoreducens group) (1.58 [1.13–2.19]) and Lactococcus (1.45 [1.01–2.06]) were associated with an increased risk (Fig. 2; Figure S2, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O793).

3.3.2. Abnormal spermatozoa

IVW analysis identified 5 bacterial genera significantly associated with abnormal spermatozoa (IVW-P < .05). Butyrivibrio (1.24 [1.00–1.52]), Lachnospiraceae UCG001 (1.57 [1.07–2.32]), Ruminococcaceae UCG009 (1.44 [1.02–2.04]), and Streptococcus (2.07 [1.24–3.44]) were linked to an increased risk, while Prevotella 9 (0.67 [0.45–0.99]) was associated with a reduced risk (Fig. 2; Figure S3, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O793).

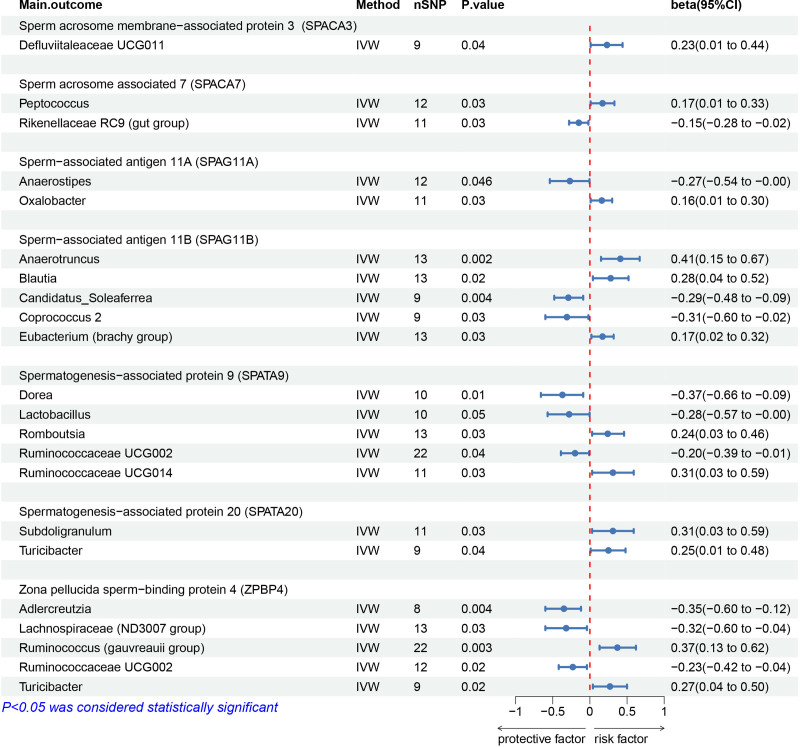

3.4. Sperm-related proteins

The study found several key associations between bacterial genera and sperm-related proteins: Defluviitaleaceae UCG011 was positively linked to SPACA3 (β = 0.23), while Rikenellaceae RC9 was negatively correlated. Peptococcus had a positive association with SPACA7 (β = 0.17), whereas Anaerostipes was negatively associated (β = −0.15). Oxalobacter was positively linked to SPAG11A (β = 0.16), while Anaerostipes showed a negative association (β = −0.27). Candidatus_Soleaferrea and Coprococcus 2 were negatively associated with SPAG11B (β = −0.29 and −0.31), while Anaerotruncus, Blautia, and Eubacterium (brachy group) had positive associations (β = 0.41, 0.28, and 0.17, respectively).

Dorea, Lactobacillus, and Ruminococcaceae UCG002 were negatively associated with SPATA9 (β = −0.37, −0.28, and −0.20), while Romboutsia and Ruminococcaceae UCG014 were positively associated (β = 0.24 and 0.31). Subdoligranulum and Turicibacter had positive associations with SPATA20 (β = 0.31 and 0.25). Adlercreutzia, Lachnoclostridium, and Ruminococcaceae UCG002 showed negative associations with ZPBP4 (β = −0.35, −0.32, and −0.23), while Lachnospiraceae (ND3007 group), Ruminococcus (gauvreauii group), and Turicibacter were positively associated with ZPBP4 (β = 0.61, 0.37, and 0.27) (Fig. 4; Figures S4–S10, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O793).

Figure 4.

MR results of causal links between gut microbiome and sperm-related proteins. CI = confidence intervals; IVW = inverse-variance weighting; OR = odds ratios; SNPs = single nucleotide polymorphisms.

3.5. Sensitivity analysis

The other MR methods, such as MR Egger, weighted median, weighted mode, and simple mode, might not all have P values below .05, but the overall trend is consistent with the IVW results (Tables S3–S13, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O792) (Fig. 3; Figures S1–S10, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O793). No heterogeneity was detected by Cochran Q test (Table S14, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O792). Employing the MR–Egger intercept and MR-PRESSO analysis revealed no signs of pleiotropy (Tables S15–S16, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O792). Following the exclusion of 1 SNP per case, no notable alterations were observed in the estimated relationship between gut microbiota and inflammation, infertility and sperm-related proteins (Fig. 5; Figures S11–S20, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/O793).

Figure 5.

Leave-one-out analysis of the causal association between gut microbiome and prostatitis.

3.6. Bidirectional MR analysis

When positive results were obtained from the initial MR analysis, a subsequent bidirectional MR analysis was performed. A causal link was observed between male infertility and Lactococcus (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.00–1.11, P = .048) and between SPAG11B and Coprococcus 2 (β = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.01–0.14, P = .02) but not with other gut microbiota genera. Sensitivity analyses revealed no heterogeneity or pleiotropy (data not shown).

4. Discussion

In the MR analysis of gut microbiota and male reproductive health, we explored the causal relationships between gut microbiota traits and conditions like male infertility, reproductive inflammation, and sperm-associated proteins. We identified 9 bacterial genera linked to prostatitis, 2 to orchitis and epididymitis, 3 to male infertility, and 5 to abnormal sperm. Additionally, different bacteria were associated with sperm-related proteins. Our study overcomes weak IV bias and ensures robust results by using various MR methods, Cochran Q tests, and MR-PRESSO analysis. Unlike previous studies, which mainly focused on correlations, our research systematically investigates the causal relationships between gut microbiota and male reproductive health.

The composition of microbial communities is intricately linked to prostate health, encompassing conditions such as prostatitis and prostate cancer. These communities include gut microbiota, urinary tract microbiota, and oral microbiota.[13] Our MR analysis identified certain bacteria with a causal association with prostatitis, reinforcing the link between gut microbiota and prostate health. The gut microbiota modulates Th17/Treg balance, influencing prostatitis, and alterations in gut microbiota – whether through dietary changes or imbalances – can impact prostate health.[38–40] Specifically, Faecalibacterium was identified as a detrimental factor for the prostate. Despite being one of the most prevalent gut bacteria in healthy adults and considered beneficial for inflammatory bowel disease and kidney disease, its role in prostate health appears to be adverse.[41–43] Conversely, Parasutterella was found to have a protective effect against prostatitis and other inflammatory conditions, such as ulcerative colitis. This suggests that certain gut bacteria exert broad anti-inflammatory effects, underscoring the complex and context-dependent roles of gut microbiota in various health conditions.[44,45]

This study uncovers a causal connection between gut microbiota and the testicular axis. We found that Ruminococcaceae UCG009 and Eubacterium (ruminantium group) exert protective effects, with Ruminococcaceae UCG009 also providing protection against prostatitis and respiratory infections, underscoring its strong anti-inflammatory properties.[46] The gut microbiota is recognized as an endocrine organ influencing distant organs, with metabolic factors linked to infertility through the gut-brain and gut-testicular axes.[47,48] For example, decreased bile acid levels impair vitamin A absorption, reducing Ruminococcaceae abundance and leading to abnormal sperm development.[49] Additionally, the gut microbiota impacts testicular inflammation by modulating immune cells, cytokines, and chemokines. Given the rising antibiotic resistance and treatment challenges for orchitis and epididymitis due to the blood–testis barrier, early identification and modulation of gut microbiota offer significant potential for preventive and therapeutic applications.[50,51]

In addition to its link with inflammatory factors, the gut microbiota can have a direct causal relationship with male infertility. Surprisingly, Lactococcus has been identified as a risk factor for male infertility, despite its role as a protective factor against female infertility and its presence in female reproductive health microbiota.[52–54] This discrepancy may be related to endocrine factors, such as sex hormones. Research shows that sex differences impact gut microbiota composition, influencing conditions like systemic lupus erythematosus and type-1 diabetes.[55–57] Androgens can significantly alter the gut microbiota, while the microbiota also affects androgen production and metabolism. For example, transplanting microbiota from adult male mice to immature female mice has been shown to increase testosterone levels and induce metabolic changes.[12,58,59]

The most direct link to male infertility is often related to sperm abnormalities, such as oligospermia, asthenospermia, and azoospermia. In this study, Prevotella 9 was identified as a protective genus against male sperm abnormalities, potentially due to its positive correlation with higher testosterone levels.[60] Conversely, semen containing micrococci or α-hemolytic streptococci is associated with increased rates of oligospermia and teratospermia, as well as lower sperm concentration and percentage of normal sperm compared to uninfected semen.[61] Additionally, significant differences in β-diversity were observed in the microbiota of patients with asthenospermia and oligospermia, with higher relative abundances of Spermatococcus, Lactobacillus, and Roseburia in asthenospermic patients, and notably higher Lactobacillus levels in oligospermic patients.[62]

This study reveals that the gut microbiota can influence proteins critical to sperm structure and function, including SPACA3, SPACA7, SPAG11A, SPAG11B, SPATA9, SPATA20, and ZPBP4, all of which are involved in sperm formation, maturation, and the sperm-egg recognition process. Through MR analysis, we identified varying effects of different gut microbiota on these proteins. While the underlying mechanisms require further investigation, our findings establish a causal link between gut microbiota and sperm-associated proteins, providing potential strategies for improving sperm quality through targeted interventions.

While much remains to be understood about the specific roles of gut microbiota in male reproductive health, their impact can be viewed from several key perspectives. The gut microbiota’s ability to modulate immune responses may influence sperm quality.[63] Additionally, bioactive molecules and metabolic products produced by these bacteria could affect hormone balance and reproductive organ function in males.[64] Gut bacteria are integral to the metabolism of male hormones and can contribute to conditions like prostatitis and orchitis through systemic inflammation.[12,65] Moreover, gut microbiota is linked to mental health, where stress and mood disorders can alter hormone levels and impact fertility.[66,67] Finally, gut bacteria play a crucial role in nutrient absorption, including trace elements like zinc and selenium, which are vital for sperm production and maturation.[68]

5. Advantages and limitations

Integrating genetic information is crucial for advancing disease prevention and treatment, but translating this knowledge into clinical practice remains challenging. This study established a connection between gut microbiota and male reproductive health using MR as a tool to treat genetic information as IVs. MR analysis effectively mitigated confounding factors and reverse causality, providing a cost-efficient alternative to randomized controlled trials.[69,70] Various statistical methods, including MR-PRESSO and MR-Egger regression intercept tests, ensured result consistency and addressed horizontal pleiotropy, while inverse MR clarified potential reverse causal relationships. By employing a two-sample MR design with nonoverlapping data, the study minimized bias and provided a robust framework for exploring the complex relationship between gut microbiota and reproductive health.[71] The findings underscore the importance of gut microbiota in male infertility and suggest potential preventive and therapeutic strategies through dietary changes, microbial supplements, or fecal microbiota transplantation.[72]

When examining the relationship between gut microbiota and male infertility, certain limitations must be considered, as they could affect our interpretation of the findings. Our research primarily utilizes GWAS summary data from individuals of European ancestry, leading to potential biases and limiting the generalizability of the results across other ethnicities. Although sex factors were adjusted and genetic variants on sex chromosomes excluded, sex-specific biases cannot be entirely ruled out. The bacterial classification at the genus level may reduce the precision of the analysis, and the study did not explore the link between male reproductive system inflammation and infertility in depth. Additionally, SNPs not meeting the conventional GWAS significance threshold (P < 5 × 10−8) might have introduced bias.[73] To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the causal relationship between gut microbiota and male infertility, future research should address these limitations by including more diverse populations, employing finer bacterial classifications, and leveraging multiomics approaches to explore the complex gene-environment interactions that influence male reproductive health.

6. Conclusion

This study used genetic data from gut microbiota and MR analysis to explore causal links with male reproductive health, including sperm-related proteins, inflammation, and infertility. Specific bacterial genera were identified as having causal effects on risks, and the robustness of these findings has been rigorously tested. By analyzing at the genetic level, this research reveals the relationship between gut microbiota and male reproductive health, offering a novel strategy for the early diagnosis of patients and identification of therapeutic targets in reproductive inflammation and infertility.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the researchers who provided the GWAS summary statistical data used in this study. We also appreciate the assistance of American Journal Experts for their editorial support.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Zhoushan Feng, Guo Feng.

Data curation: Jingwen Mei, Shicun Qiao, Wen Long.

Formal analysis: Shicun Qiao, Wen Long.

Investigation: Jingwen Mei, Shicun Qiao.

Methodology: Jingwen Mei, Shicun Qiao, Guo Feng.

Project administration: Xiaohong Wu, Zhoushan Feng.

Resources: Xiaohong Wu, Shicun Qiao, Zhoushan Feng, Guo Feng.

Software: Jingwen Mei.

Supervision: Xiaohong Wu, Zhoushan Feng.

Validation: Wen Long, Guo Feng.

Visualization: Wen Long.

Writing – original draft: Jingwen Mei, Wen Long.

Writing – review & editing: Xiaohong Wu, Zhoushan Feng, Guo Feng.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations:

- CIs

- confidence intervals

- IVs

- instrumental variables

- IVW

- inverse-variance weighting

- MR

- Mendelian randomization

- ORs

- odds ratios

- SNPs

- single nucleotide polymorphisms

- SPACA3

- sperm acrosome membrane-associated protein 3

- SPAG11A

- sperm-associated antigen 11A

- SPAG11B

- sperm-associated antigen 11B

- SPATA20

- spermatogenesis-associated protein 20

- SPATA9

- spermatogenesis-associated protein 9

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 81830045 and 82171666).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

How to cite this article: Wu X, Mei J, Qiao S, Long W, Feng Z, Feng G. Causal relationships between gut microbiota and male reproductive inflammation and infertility: Insights from Mendelian randomization. Medicine 2025;104:17(e42323).

XW, JM, and SQ contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiaohong Wu, Email: 1152504644@qq.com.

Jingwen Mei, Email: meijingwen613@163.com.

Shicun Qiao, Email: 17697210326@163.com.

Wen Long, Email: llongwen@163.com.

Guo Feng, Email: fengyue20021@163.com.

References

- [1].Eisenberg ML, Esteves SC, Lamb DJ, et al. Male infertility. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sun H, Gong TT, Jiang YT, Zhang S, Zhao YH, Wu QJ. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: results from a global burden of disease study, 2017. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11:10952–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Agarwal A, Baskaran S, Parekh N, et al. Male infertility. Lancet. 2021;397:319–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jodar M, Soler-Ventura A, Oliva R, Molecular Biology of Reproduction and Development Research Groupeproduction, Development Research Group. Semen proteomics and male infertility. J Proteomics. 2017;162:125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bisconti M, Simon JF, Grassi S, et al. Influence of risk factors for male infertility on sperm protein composition. Int J Mol Sci . 2021;22:13164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Beurois J, Cazin C, Kherraf ZE, et al. Genetics of teratozoospermia: back to the head. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34:101473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nelson KE, Weinstock GM, Highlander SK, et al. A catalog of reference genomes from the human microbiome. Science. 2010;328:994–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zmora N, Suez J, Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:35–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Adak A, Khan MR. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:473–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ahmadian E, Rahbar Saadat Y, Hosseiniyan Khatibi SM, et al. Pre-eclampsia: microbiota possibly playing a role. Pharmacol Res. 2020;155:104692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liu JB, Chen K, Li ZF, Wang ZY, Wang L. Glyphosate-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis facilitates male reproductive toxicity in rats. Sci Total Environ. 2022;805:150368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wang Y, Xie Z. Exploring the role of gut microbiome in male reproduction. Andrology. 2022;10:441–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Porter CM, Shrestha E, Peiffer LB, Sfanos KS. The microbiome in prostate inflammation and prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21:345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sheng W, Xu W, Ding J, et al. Guijiajiao (Colla Carapacis et Plastri, CCP) prevents male infertility via gut microbiota modulation. Chin J Nat Med. 2023;21:403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sochocka M, Donskow-Lysoniewska K, Diniz BS, Kurpas D, Brzozowska E, Leszek J. The gut microbiome alterations and inflammation-driven pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease-a critical review. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:1841–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Weiss G, Goldsmith LT, Taylor RN, Bellet D, Taylor HS. Inflammation in reproductive disorders. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:216–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27:1133–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xiang K, Wang P, Xu Z, et al. Causal effects of gut microbiome on systemic lupus erythematosus: a two-sample mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2021;12:667097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liang Y, Zeng W, Hou T, et al. Gut microbiome and reproductive endocrine diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1164186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kurilshikov A, Medina-Gomez C, Bacigalupe R, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition. Nat Genet. 2021;53:156–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature. 2018;558:73–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;362:k601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sanna S, van Zuydam NR, Mahajan A, et al. Causal relationships among the gut microbiome, short-chain fatty acids and metabolic diseases. Nat Genet. 2019;51:600–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Amoroso C, Perillo F, Strati F, Fantini MC, Caprioli F, Facciotti F. The role of gut microbiota biomodulators on mucosal immunity and intestinal inflammation. Cells. 2020;9:1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang Y, Zhang X, Chen D, et al. Causal associations between gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:971376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Burgess S, Thompson SG, CRP CHD Genetics Collaboration. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:755–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Palmer TM, Sterne JA, Harbord RM, et al. Instrumental variable estimation of causal risk ratios and causal odds ratios in Mendelian randomization analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1392–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Assessing the suitability of summary data for two-sample Mendelian randomization analyses using MR-Egger regression: the role of the I2 statistic. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1961–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Huang YF, Zhang WM, Wei ZS, et al. Causal relationships between gut microbiota and programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death-ligand 1: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1136169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang W, Zhang S, Zhao F, Du J, Wang Z. Causal relationship between gut microbes and cardiovascular protein expression. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1048519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:377–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ni JJ, Xu Q, Yan SS, et al. Gut microbiota and psychiatric disorders: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:737197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li Y, Li Q, Cao Z, Wu J. The causal association of polyunsaturated fatty acids with allergic disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:962787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Du HX, Yue SY, Niu D, et al. Gut microflora modulates Th17/Treg cell differentiation in experimental autoimmune prostatitis via the short-chain fatty acid propionate. Front Immunol. 2022;13:915218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhong W, Wu K, Long Z, et al. Gut dysbiosis promotes prostate cancer progression and docetaxel resistance via activating NF-kappaB-IL6-STAT3 axis. Microbiome. 2022;10:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Matsushita M, Fujita K, Nonomura N. Influence of diet and nutrition on prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci . 2020;21:1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Miquel S, Martin R, Rossi O, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and human intestinal health. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:255–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Qiu X, Zhang M, Yang X, Hong N, Yu C. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii upregulates regulatory T cells and anti-inflammatory cytokines in treating TNBS-induced colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e558–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li HB, Xu ML, Xu XD, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Attenuates CKD via Butyrate-Renal GPR43 Axis. Circ Res. 2022;131:e120–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Liu X, Zhang Y, Li W, et al. Fucoidan ameliorated dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis by modulating gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. J Agric Food Chem. 2022;70:14864–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wu X, Xu N, Ye Z, et al. Polysaccharide from Scutellaria barbata D. Don attenuates inflammatory response and microbial dysbiosis in ulcerative colitis mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;206:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Huang S, Li J, Zhu Z, et al. Gut microbiota and respiratory infections: insights from Mendelian randomization. Microorganisms. 2023;11:2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Mayer EA, Nance K, Chen S. The gut-brain axis. Annu Rev Med. 2022;73:439–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Martinot E, Thirouard L, Holota H, et al. Intestinal microbiota defines the GUT-TESTIS axis. Gut. 2022;71:844–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zhang T, Sun P, Geng Q, et al. Disrupted spermatogenesis in a metabolic syndrome model: the role of vitamin A metabolism in the gut-testis axis. Gut. 2022;71:78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ryan L, Daly P, Cullen I, Doyle M. Epididymo-orchitis caused by enteric organisms in men > 35 years old: beyond fluoroquinolones. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37:1001–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wen Q, Tang EI, Gao Y, et al. Signaling pathways regulating blood-tissue barriers - lesson from the testis. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860:141–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ding H, Wang Y, Li Z, et al. Baogong decoction treats endometritis in mice by regulating uterine microbiota structure and metabolites. Microb Biotechnol. 2022;15:2786–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zhou L, Ni Z, Cheng W, et al. Characteristic gut microbiota and predicted metabolic functions in women with PCOS. Endocr Connect. 2020;9:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Xi Y, Zhang C, Feng Y, et al. Genetically predicted the causal relationship between gut microbiota and infertility: bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis in the framework of predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine. EPMA J. 2023;14:405–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hevia A, Milani C, Lopez P, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. mBio. 2014;5:e01548–01514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Mu Q, Zhang H, Liao X, et al. Control of lupus nephritis by changes of gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2017;5:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kriegel MA, Sefik E, Hill JA, Wu HJ, Benoist C, Mathis D. Naturally transmitted segmented filamentous bacteria segregate with diabetes protection in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11548–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Choi S, Hwang YJ, Shin MJ, Yi H. Difference in the gut microbiome between ovariectomy-induced obesity and diet-induced obesity. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;27:2228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Markle JG, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science. 2013;339:1084–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Haro C, Rangel-Zuniga OA, Alcala-Diaz JF, et al. Intestinal microbiota is influenced by gender and body mass index. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mehta RH, Sridhar H, Vijay Kumar BR, Anand Kumar TC. High incidence of oligozoospermia and teratozoospermia in human semen infected with the aerobic bacterium Streptococcus faecalis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2002;5:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Yang H, Zhang J, Xue Z, et al. Potential pathogenic bacteria in seminal microbiota of patients with different types of dysspermatism. Sci Rep. 2020;10:6876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Hussein MR, Abou-Deif ES, Bedaiwy MA, et al. Phenotypic characterization of the immune and mast cell infiltrates in the human testis shows normal and abnormal spermatogenesis. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1447–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Cai H, Cao X, Qin D, et al. Gut microbiota supports male reproduction via nutrition, immunity, and signaling. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:977574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chen J, Chen J, Fang Y, et al. Microbiology and immune mechanisms associated with male infertility. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1139450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Gubert C, Kong G, Renoir T, Hannan AJ. Exercise, diet and stress as modulators of gut microbiota: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;134:104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Ilacqua A, Izzo G, Emerenziani GP, Baldari C, Aversa A. Lifestyle and fertility: the influence of stress and quality of life on male fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Mirnamniha M, Faroughi F, Tahmasbpour E, Ebrahimi P, Beigi Harchegani A. An overview on role of some trace elements in human reproductive health, sperm function and fertilization process. Rev Environ Health. 2019;34:339–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bowden J, Holmes MV. Meta-analysis and Mendelian randomization: a review. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10:486–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wang Y, Li T, Fu L, Yang S, Hu YQ. A novel method for Mendelian randomization analyses with pleiotropy and linkage disequilibrium in genetic variants from individual data. Front Genet. 2021;12:634394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Burgess S, Davies NM, Thompson SG. Bias due to participant overlap in two-sample Mendelian randomization. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Quaranta G, Sanguinetti M, Masucci L. Fecal microbiota transplantation: a potential tool for treatment of human female reproductive tract diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Agusti A, Melen E, DeMeo DL, Breyer-Kohansal R, Faner R. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: understanding the contributions of gene-environment interactions across the lifespan. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10:512–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.