Abstract

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), classified as a neglected tropical disease (NTD), is a significant public health concern caused by Leishmania protozoa. It is transmitted through the bites of infected female sandflies and manifests in various forms, ranging from localized skin ulcers to social stigma due to scarring. Numerous reports highlight the life-threatening side effects of glucantim, the first-line treatment for this disease, indicating a pressing need foralternative drugs. This experimental study aims to assess the anti-leishmanial effects of chitosan and chitosan- amphotericin B against Leishmania major (L. major) in vitro and in vivo. Chitosan and amphotricine B were purchased, and different concentrations were prepared. L. major promastigotes were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium. In vitro anti-leishmanial activity was assessed against the promastigotes of L. major using vital staining. For the in vivo assessment, lesion sizes were measured before and after ointment treatments in Bagg Albino mice (BALB/c). The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2 H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was utilized to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of chitosan and chitosan–amphotericin B at varying concentrations on the L929 cell line. Additionally, the in vitro hemolytic activity was measured using a spectrophotometric method. The in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that chitosan–amphotericin B exhibited superior inhibitory effects against L. major compared to either chitosan or amphotericin B alone, and even against the positive control, particularly at higher concentrations (P < 0.05). Furthermore, cytotoxicity tests indicated that both chitosan and amphotericin, whether used separately or in combination, had no cytotoxic effects on the L929 cell line or human blood samples in vitro and did not impact liver enzymes in vivo (P < 0.05). The findings from this in vitro and in vivo study highlighted the impressive anti-leishmanial effects of chitosan, which were further enhanced with the addition of amphotericin B.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13568-025-01877-7.

Keywords: Anti-leishmanial, Leishmania major, Cytotoxicity, Chitosan, Amphotericin B

Introduction

Leishmaniasis, as one of the most infectious parasitic disease, is caused by an intracellular parasite of the genus Leishmania and is transmitted through the bites of female sandflies (Reithinger et al. 2007). This infection has been reported in 105 countries, and currently, more than one billion people live in endemic areas and are at risk of Leishmanisis. Different species of Leishmania cause a wide range of clinical symptoms, ranging from self-limiting but scarred skin lesions (cutaneous leishmaniasis, CL) to rarer and more complex forms of CL and visceral leishmaniasis (VL). Based on clinical aspects, leishmaniasis in humans is categorized into four forms: CL, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL), and visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also known as kala-azar (Mcgwire and Satoskar 2014). CL is the most widespread form of leishmaniasis, with an annual incidence of about 1.5 million cases (Atan et al. 2018). Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Algeria, Brazil, Tunisia, Syria, Turkey, Morocco, Pakistan, Peru and Colombia are the twelve mostprevalent countries with a heavy burden of CL infection (Pasquier et al. 2022).

Several systemic and local therapeutic methods are used as first-line treatment for leishmaniasis, including chemical drugs (pentavalent antimonial, pentamidine, miltefosine, amphotericin B, and paromomycin) and physical treatments such as cryotherapy, thermotherapy, surgery, and laser therapy (AlMohammed et al. 2021). Unfortunately, many of these medications are burdened with limitations such as high cost, administration challenges, significant adverse effects, varying sensitivities among Leishmania species, and drug resistance (Bi et al. 2018). Additionally, several factors affect the treatment outcomes for leishmaniasis, including geographical areas, social variances, type of diseases, parasite species, and immune system (Al-Salem et al. 2019).

In light of these obstacles, there is an urgent need for more effective and safer treatment as well as new drug targets for leishmaniasis. Urgent attention is required for the development of a new class of drugs or innovative strategies, particularly through combination therapy for CL. This pioneering approach should aim to eradicate parasites and enhance the wound healing process. Additionally, it should be adaptable for deployment in diverse healthcare centers.

The incorporation of combination therapy into the treatment of CL presents a promising avenue, with the potential to alleviate adverse reactions and consequently improve treatment adherence. Moreover, combination therapy may augment the effectiveness of therapeutic protocols in patients with concomitant infections (Trinconi et al. 2014). To achieve new therapeutic solutions, the World Health Organization (WHO) advocates for the utilization of medicinal plants and natural compounds, either as standalone therapies or in combination with other effective drugs, as complementary or alternative approaches. The availability of numerous beneficial drugs derived from medicinal plants and natural compounds underscores the significant potentialof accessing new sources of drugs against leishmaniasis (Date et al. 2007).

Chitosan is a biodegradable cationic polysaccharide produced by the deacetylation of chitin. Numerous publications have addressed the antimicrobial and anti-leishmanial activities of chitosan due to its antioxidant activity and immune-stimulating effects, and it can be used as a drug delivery vehicle (Ziani et al. 2011). Despite the absence of a fully explained mechanism of action, several possible mechanisms have been suggested. For example, chitosan is believed to activate polymorphonuclear leukocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts, contributing to the acceleration of wound healing (Cheung et al. 2015; Peluso et al. 1994). Another suggested mechanism involves chitosan binding to pathogen DNA, leading to the inhibition of DNA transcription (Goy et al. 2009; Hadwiger et al. 1986). Additionally, an indirect mechanism of action may be associated with the proinflammatory effect of chitosan on macrophages, which represent the primary habitat for leishmanial amastigote form. Stimulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) is a key aspect of this process. These factors play essential roles in the proinflammatory response against intracellular pathogens, increasing the production of microbicidal reactive nitrogen species (Peluso et al. 1994; Porporatto et al. 2003; Ravindranathan et al. 2016; Sarkar et al. 2017).

Given all biological characteristics and activities listed, chitosan stands out as a viable candidate for more in-depth studies to evaluate its suitability for the treatment of CL. This study aims to assess the anti-parasitic activity of chitosan, amphotericin B, and chitosan- amphotericin B in different proportions against L. major in vitro and in murine models.

Methods

Materials

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO: 99%), glacial acetic acid, ethanol, sodium chloride, and neutral red were provided by Merck Chemical Company (Germany). MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide), Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium, griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide in H3PO4 10% (v/v) in Milli-Q water), heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), the antibiotics penicillin and streptomycin, and chitosan were supplied by Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, USA). Tween 80, span 80, span 60, stearic acid (SA), and solvents were purchased from Merck Co. (Germany). Distilled water was purified by a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Direct-Q), and amphotricine B was purchased from Research Products International (RPI), USA.

Study place

This study was design and completed in Mazandaran Province in northern Iran, bordered by the Caspian Sea to the north and the Alborz mountain range to the south with diverse natural landscapes including plains, forests, and mountainous regions. These area located in geographical coordinates of around 36°23′N latitude and 52°11′E longitude and the average rainfall ranges from 600 mm to over 2,000 mm with peak rainfall typically seen in autumn. The climate can be classified as moderate with hot, humid summers and mild winters.

Parasites cultivation

L. major promastigotes, Iranian strain MRHO/IR/75/ER, were obtained from the Department of Parasitology, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. The Parasites were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7.4) supplemented with 20% FBS), 25 mM of HEPES (0.1 M, pH of 7.4), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and incubated at 24 °C with frequent passages every three days (Rahimi-Esboei et al. 2018).

Study design

To investigate the killing effect of chitosan and chitosan–amphotericin B on L. major in vitro, 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major in a 96-well plate were incubated with different concentrations of chitosan and amphotericin B. For in vivo study, the treatment process was conducted on BALB/c mice divided into15 groups under the following experimental conditions:

Group A Amphotericin B; 100 µl of amphotericin B with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group B Glucantime; 100 µl of glucantime with a concentration of 0.3 g/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group C Chitosan (100 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (75/25); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group D Chitosan (100 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (50/50); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group E Chitosan (100 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (25/75); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group F Chitosan (200 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (75/25); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group G Chitosan (200 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (50/50); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group H Chitosan (200 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (25/75); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group I Chitosan (400 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (75/25); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group J Chitosan (400 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (50/50); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group K Chitosan (400 µg/ml) + amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) (25/75); 100 µl of soultion with a concentration of 500 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group L Chitosan; 100 µl of chitosan with a concentration of 100 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group M Chitosan; 100 µl of chitosan with a concentration of 200 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group N Chitosan; 100 µl of chitosan with a concentration of 400 µg/ml was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Group O Phosphate buffer saline (PBS); 100 µl of PBS was added to wells containing 1 × 106 promastigotes of L. major.

Assessment of anti-promastigote activity in vitro

The 96-well plate containing 100 µl of L. major promastigotes (1 × 106 cells/ml) in the logarithmic phase, along with the treatments (according to the groups), was introduced into the wells. The plate was kept at 26 °C, and the viability of the parasites was determined after 12, 24, and 48 h using eosin 0.1% as vital stain (Saberi et al. 2021).

Assessment of anti-leishmanial effects in vivo

Seventy-fivefemale BALB/c mice (weighing about 20 g and aged 6–7 weeks) were acquired from Razi Rad Industries, Tehran, Iran. All protocols were done according to the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals. Procedures involving experimental animals received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Research at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (IR.MUI.MED.REC.1399,056). Throughout the experimental period, animals were housed in standard boxes under controlled conditions of light and temperature and were provided with a standard diet.

The mice were divided into 15 groups, each consisting of 5 mice. To initiate Leishmaniasis, a subcutaneous injection of stationary phase promastigotes (1.5 × 106 L. major promastigotes) was performed at the base of the tail of each mouse. The mice were then assigned to the following groups: a standard group that received amphotericin B and glucantime;, test groups that received chitosan ointment in concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 µg/ml, a group that received loaded chitosan–amphotericin B ointment at different concentration; and a control group that received the ointment without any active ingredients or PBS solution.

Inoculated mice experienced the formation of nodules and ulcers after 21 days. Topical treatment was administered to each mouse continuously every 28 days. To confirm the presence of the Leishmania parasite, samples from each lesion were examined for amastigotes using direct microscopy (1000×). Weekly measurements of lesion diameter were performed before and after treatment using a dial micrometer (Starrett Dial indicator, model 25 A, USA). Subsequently, these measurements were compared with those of untreated lesions (Elmi et al. 2021). The following formula was applied for determining of the ulcer score (Rahimi-Esboei et al. 2018):

|

Biochemical analysis

The toxic effects of the mentioned treatments on the livers were evaluated by analyzing aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in serum samples from the mice, using a Pars Azmoon kit (Iran) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The normal ranges for ALT and AST, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, were 75–90 IU/l and 125–155 IU/l, respectively (Mousavi et al. 2022).

Hemolytic assay

The spectrophotometric method was employed to assess in vitro hemolytic activity. A human blood suspension (0.2 ml) was combined with chitosan (100, 200, and 400 µg/ml) and chitosan–amphotericin B (500 µg/ml) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (0.8 ml). The mixture underwent a 30-minute incubation at 37 °C, followed by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The analysis of free hemoglobin in the supernatant was carried out using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at 540 nm. Minimal and maximal hemolytic controls were established using PBS and distilled water, respectively. Each sample was executed in triplicate (Mousavi et al. 2022).

Cell toxicity assay

An MTT assay, as detailed earlier, was employed to confirm the cytotoxic effects of chitosan and chitosan–amphotericin B at different concentrations on the L929 cell line. For this purpose, the L929 cell line was purchased from Pasteur Institute (Tehran-Iran) and then cultured in RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 100 IU/ml of penicillin at 37 °C. After the final passage, cells were centrifuged and diluted in a fresh culture medium to a final density of 1 × 105 cells/ml. Following preparation of the suspension, 200 µl (containing 500000 cells) were added to the different rows of a 96-well plate. Then, 200 µl of various concentrations of each mentioned compound, along with 200 µl of amphotericin B and glucantime (as positive controls), were added to each well. In another row, 200 µl of medium containing L929 cell without any drug compounds was added as a negative control. Subsequently, the plate was placed in the incubator at 37 °C. After 72 h, each well received an addition of MTT reagent prepared by combining 5 mg of MTT powder with 1 ml of sterile PBS. The plate was then incubated in a dark room for 3 h. Afterward, 200 µl of DMSO was added to each well, and the plate was stored in a dark environment for 10–20 min. The final step involved measuring the optical density at a wavelength of 570 nm using an ELISA reader (Batool et al. 2022).

|

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons between the mean values of the experimental groups (Anti-parasitic treatments and toxicity assessments) were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with SPSS version 21 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The results of in vitro study

In this study, the effects of chitosan and amphotericin B were investigated separately and in combination at different proportions. The results of the in vitro study revealed that amphotericin B and even glucantime were more effectiveness against promastigotes of L. major compared to chitosan at concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 µg/ml. However, when chitosan was mixed with amphotericin B, the anti-leishmanial effects were significantly improved compared to each compound used separately (P < 0.05; Fig. 1). According to Fig. 1, chitosan and amphotericin B in all separated and mixed forms showed significantly better effectiveness than glucantime (P < 0.05), except at a concentration of 100 µg/ml of chitosan (P = 0.053 after 12 h, P = 0.430 after 24 h). After 48 h, the anti-leishmanial effects of groups C, E, F, G, H, K, and L were statistically different from glucantime (P < 0.05). In comparison to amphotricine B, the effectiveness of group L was statistically less (P = 0.083), while other groups had similar results (P > 0.05). The IC50 of chitosan in the current study after 48 h was calculated as 71.63 µg/ml, while the IC50 of amphotricine B was calculated as 255.88 µg/ml.

Fig. 1.

In vitro leishmanicidal effects of chitosan and amphotericin B alone or combination in different proportions after a 7, b 14, and c 21 days of treatment. *Significant differences according to the control, P < 0.05. Abbreviations. Amph: amphotericin B, Chit: chitosan, Glu: Glucantime

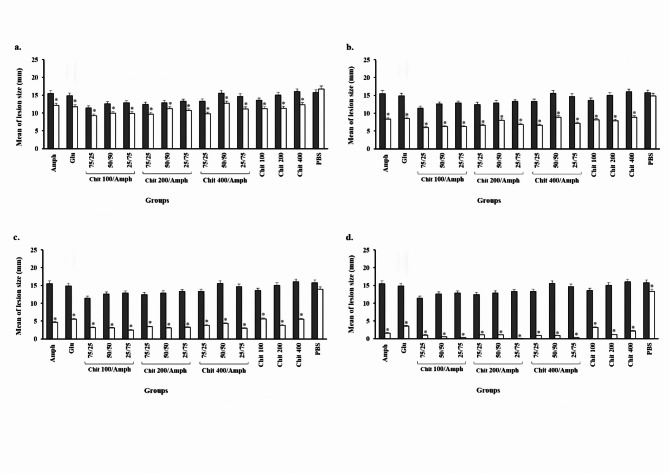

The results of in vivo study

The lesion sizes in different groups were measured before and after 7, 14, 21, and 28 days of treatment. Our findings showed that the leishmanicidal effects of all the studied compounds in all groups were significantly better than those in the negative control groups (P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The results indicated that the lesion sizes after exposure to chitosan at concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 µg/ml after 28 days decreased from 13.73 to 3.14 mm, from 15.03 to 1.19 mm, and from 16.24 to 2.27 mm, respectively. In the group receiving amphotericin B, the wound size decreased from 15.71 to 1.59 mm (Fig. 2d). However, the results for groups C to K demonstrated that the chitosan-loaded amphotericin B had a synergistic effect.

Fig. 2.

In vivo leishmanicidal effects of chitosan (100, 200, and 400 µg/ml) and amphotericin B separated and mixed forms in different proportions before and after a 7, b 14, c 21, and d 28 days of treatment in BALB/c mice. *Significant differences according to the control, P < 0.05. Abbreviations. Amph: amphotericin B, Chit: chitosan, Glu: Glucantime

In groups E, H, and K, where the chitosan–amphotericin B combination at a ratio of 25/50 was used, the effectiveness rates decreased from 12.8 to 0.4 mm, from 13.26 to 0.07 mm, and from 14.7 to 0.3 mm, respectively. In other words, the effect of chitosan–amphotericin B in combination was superior to that of either amphotericin B or chitosan alone. The results also showed that the leishmanicidal effects of all groups were significantly better than those glucantime (P = 0.003).

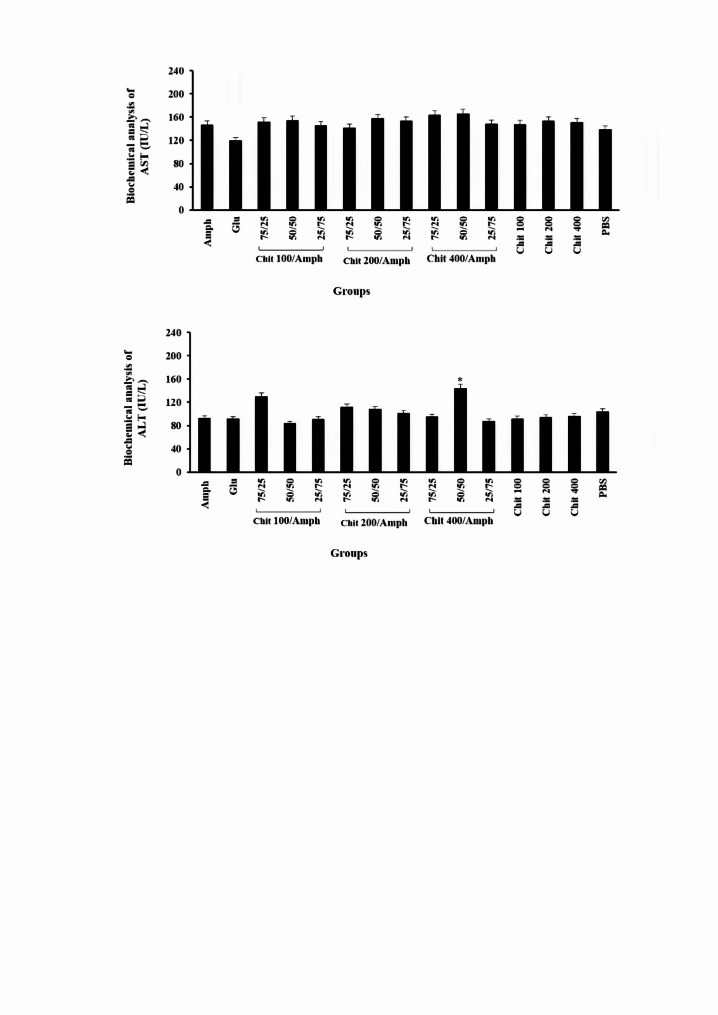

Biochemical analysis

The biochemical parameters, such as AST and ALT, were evaluated before and after treatments with different formulations, including chitosan, amphotericin B, a combination of chitosan and amphotericin B, and control groups. Our findings suggested that the level of AST in groups receiving glucantime and amphotericin B was higher compared to the other treatment groups; however, the differences did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.072). When evaluating ALT, most groups were within the normal range; however, the level of ALT in group J (chitosan 400 µg/ml- amphotericin B (50/50)) demonstrated a significantly higher value compared to the other groups (P = 0.037; Fig. 3). The results of the current investigation into liver toxicity indicated that the liver enzyme results varied significantly among the groups, suggesting that the toxicity of these drugs cannot be judged solely based on these tests and must be confirmed with additional assessments.

Fig. 3.

Biochemical analysis of AST and ALT as the biologic factors in BALB/c mice following treatment with different doses of chitosan (100, 200, and 400 µg/ml) and amphotericin B separated and mixed forms in different proportions. *Significant differences according to the control, P < 0.05. Abbreviations. Amph: amphotericin B, Chit: chitosan, Glu: Glucantime

Hemolytic activity

As presented in Table 1, the hemolytic effects of chitosan (at concentrations of 10, 50, and, 100 mg/ml), amphotericin B, Triton X-100, and PBS were assessed. The results revealed that chitosan at all concentrations exhibited similar hemolytic effects to PBS without significant difference, and all were significantly lower than Triton X-100as a positive control (P = 0.001). Amphotericin B showed hemolytic effects of 13.9%, 17.9%, and 18.4% after 12, 24, and 48 h, respectively, which were significantly higher than those of chitosan (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

The hemolytic effects of the Chitosan in concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 mg/ml in comparison to the amphotericin B and control groups

| Treatment groups | Hemolytic activity (%) ± SD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours | ||||||

| 12 | P value | 24 | P value | 48 | P value | |

| Chitosan 10 mg/ml | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.00* | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.00* | 1.8 ± 0.03 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 50 mg/ml | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 0.00* | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 0.00* | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 100 mg/ml | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 0.00* | 5.4 ± 0.01 | 0.00* | 7.7 ± 0.6 | 0.00* |

| Amphotericin B 500 µg/ml | 13.9 ± 0.4 | 0.00* | 17.9 ± 0.9 | 0.00* | 18.4 ± 0.9 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 10 mg/ml- amphotericin B 500 µg/ml | 12.0 ± 0.7 | 0.00* | 12.8 ± 0.9 | 0.00* | 12.7 ± 0.6 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 50 mg/ml- amphotericin B 500 µg/ml | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 0.00* | 10.2 ± 0.2 | 0.00* | 12.0 ± 0.5 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 100 mg/ml- amphotericin B 500 µg/ml | 8.8 ± 0.4 | 0.00* | 9.9 ± 0.4 | 0.00* | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 0.00* |

| Glucantime | 15.6 ± 0.5 | 0.00* | 18.6 ± 0.6 | 0.00* | 20.3 ± 0.8 | 0.00* |

| Triton X100 | 90.1 ± 4.5 | 0.00* | 99.4 ± 0.5 | 0.00* | 100 ± 0.0 | 0.00* |

| PBS | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.00* | 0.6 ± 0. 2 | 0.00* | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.00* |

*Significant differences according to the control, P < 0.05

Cytotoxicity activity

The MTT assay based on tetrazolium colorimetry demonstrated that chitosan at concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 mg/ml exhibited equal toxicity to PBS as a negative control (P = 0.094, P = 0.085, P = 0.733, respectively) and significantly lower than cisplatin as positive control (P = 0.001). The cytotoxicity effects of amphotericin B were significantly lower than those of cisplatin (P = 0.001) but higher than those of chitosan with a non-significant difference (Table 2). In addition, the results related to IC50, IC90 and IC95 are 1.322, 59.48 and 84.78 at 48 h hours, respectively.

Table 2.

The cytotoxic effects of the Chitosan in concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 mg/ml in comparison to the amphotericin B and control groups

| Treatment groups | Cytotoxic activity (%) ± SD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours | ||||||

| 6 | P value | 12 | P value | 24 | P value | |

| Chitosan 10 mg/ml | 0.81 ± 0.004 | 0.00* | 0.68 ± 0.008 | 0.00* | 0.61 ± 0.01 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 50 mg/ml | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.00* | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 0.00* | 0.59 ± 0.009 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 100 mg/ml | 0.56 ± 0.009 | 0.00* | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 0.00* | 0.50 ± 0.009 | 0.00* |

| Amphotericin B 500 µg/ml | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.00* | 0.41 ± 0.07 | 0.00* | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 10 mg/ml- amphotericin B 500 µg/ml | 0.74 ± 0.006 | 0.00* | 0.70 ± 0.04 | 0.00* | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 50 mg/ml- amphotericin B 500 µg/ml | 0.69 ± 0.003 | 0.00* | 0.66±-0.003 | 0.00* | 0.61 ± 0.06 | 0.00* |

| Chitosan 100 mg/ml- amphotericin B 500 µg/ml | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 0.00* | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.00* | 0.58 ± 0.007 | 0.00* |

| Glucantime | 0.43 ± 0.002 | 0.00* | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.00* | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.00* |

| Triton X100 | 0.14±-0.002 | 0.00* | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.00* | 0.11 ± 0.006 | 0.00* |

| PBS | 0.95 ± 0.037 | 0.00* | 0.98 ± 0.21 | 0.00* | 1.12 ± 0.84 | 0.00* |

*Significant differences according to the control, P < 0.05

Discussion

Pentavalent antimony is used as the first–line conventional drug for the treatment of leishmaniasis in endemic areas; however, it is associated with severe consequences, and in 10–25% of cases, there is a possibility of disease recurrence (Horber et al. 1991; Sundar and Chakravarty 2010). These drugs have shown toxic effects on the heart, liver, and kidney, and the number of reports regarding resistance to these drugs is increasing (Özbilgin et al. 2020). Consequently, many researchers have focused on finding alternative, cheaper, safer, and more accessible drugs for the poorest population on Earth and less complicated to use (Gervazoni et al. 2020; Rahimi-Esboei et al. 2018). Natural compounds extracted from plants are potent for these objectives. According to the WHO, about 80% of the world’s population now uses herbal remedies for the treatment of various infectious and non-infectious diseases (Zhang et al. 2019). Numerous studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of medicinal plant extracts against leishmaniasis (Brito et al. 2013; Elmi et al. 2021; Raeisi et al. 2020). Medicinal plants and their secondary metabolites-such as terpenes, phenolic compounds, and nitrogen/sulfur-containing compounds-exhibit many therapeutic effects against leishmania spp. However, most of these products are not reproducible in in vivo experiments. Consequently, many, such as Ligustim chuanxiong, Menta villosa, Artemisia annua, and Croton argyropylloides are still under pre-clinical trials (Da Silva et al. 2012; Raj et al. 2020).

In the present study, commercial chitosan at concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 µg/ml was used to assess its anti-leishmanial activity in vitro and in vivo against CL caused by L. major. The obtained results were compared to the amphotericin B as a positive control. Lesion sizes in different groups was calculated before treatment and at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after treatment. Chitosan demonstrated a time- and dose-dependent manner, and the combination of chitosan and amphotericin B showed better effectiveness than either amphotericin B or chitosan alone. The results also indicated that the leishmanicidal effects of all groups were significantly better than those of glucantime (P = 0.003).

The chitosan in current study in combination to the Amphotricine B showed 70–100% anti-leishmanial effects. Similarly to our study, Rahimi-Esboei et al. (2018) reported that Chitosan at concentrations of 200 and 400 µg/mL after 180 min had 100% lethality effectiveness against L. major promastigotes and chitosan reveals as a strong anti-leishmanial agent, achieving complete parasite elimination (Rahimi-Esboei et al. 2018). Chitosan-Based Silver Nanoparticles (2017) showed a potent activity against both promastigote and amastigote stages of L. amazonensis, with IC50 values ranging from 0.422 to 2,120 µg/mL and revealed a synergistic effect of silver nanoparticles that enhances the antimicrobial efficacy of chitosan (Lima et al. 2017). In the current study, the IC50 of chitosan on L. major after 48 h was calculated as 71.63 µg/ml that was more effective than Chitosan-Based Silver Nanoparticles, while the IC50 of amphotricine B was calculated as 255.88 µg/ml. Rahimi et al. (2020) assessed the anti-leishmanial effects of Chitosan-Polyethylene Oxide Nanofibers against L. major and the IC50 values on promastigotes and amastigotes was ranged from 0.197 to 1.023 µg/mL. The reported effectiveness of chitosan in the present study aligns well with results from other studies, which also establish high anti-leishmanial activity against various Leishmania species. The efficiency varieties from complete lethality to significant reductions in parasite viability, depending on the formulation.

Chitosan at different molecular weightsshowed excellent antibacterial effects against Pseudomonas fluorescens, Escherichia coli, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Salmonella typhimurium as Gram-negative bacteria, as well as Bacillus megaterium, Lactobacillus monocytogenes, L. bulgaricus, L.plantarum, L. brevis, Staphylococcus aureus, and B. cereus as Gram-positive bacteria (No et al. 2002). Furthermore, various studies have reported the anti-parasitic effects of chitosan with promising results. Fungal chitosan extracted from Penicillium viridicatum and P. aurantiogriseum exhibited better scolicidal effects against the protoscolices of Echinococcus granulosus in vitro (Rahimi-Esboei et al. 2013). A similar study evaluated the anti-giardia activity of chitosan on the cyst stage of Giardia lamblia (G. lamblia) and reported that chitosan at a concentration of 400 µg/ml killed 100% of cysts after 180 min of exposure (Yarahmadi et al. 2016). Elmi et al. (2020) assessed the anti-protozoan effects of chitosan and nano- chitosan against Plasmodium falciparum, G. lamblia, and Trichomonas vaginalis, which are amongthe most important protozoa affecting. The results indicated that nano- chitosan at a concentration of 50 µg/ml inhibited 59.5%, 99.4%, and 31.3% of the growth rates of P. falciparum, T. vaginalis, and G. lamblia, respectively (Elmi et al. 2021). Najm et al. (2021) indicated that the methanolic extracts of Artimisia persica, A. fragrance, and A. spicigera inhibited the growth of the Leishmania parasite, with the IC50 values of 51 µg/ml, 400 µg/ml, and 200 µg/ml, respectively (Najm et al. 2021).

In this study, a chitosan–amphotericin B combination was also used, and surprising results were obtained. The combination of chitosan–amphotericin B had a synergistic effect in vitro and in vivo, and the growth inhibition effectiveness of the drug in the combined form was much better than when the drugs were used separately.

In the present study, we used chitosan as a nanocarrier to deliver amphotericin B, and the results revealed that chitosan can potentially reduce toxicity and increase the efficacy of amphotericin B. It can also facilitate stable drug delivery at the site of action and prevent drug degradation. Our study found that the combination of chitosan with amphotericin B was more stable and effective than amphotericin B alone, which is consistent with the findings of Riezk et al. (Riezk et al. 2020). The liposomal structures used to formulate amphotericin B are both costly and require a cold chain for stability; thus, we have largely overcome this issue by using chitosan (Frézard et al. 2022).

To maximize the effect of the synthesized nanocomposite on Leishmania inside the cell, we synthesized nanoparticles smaller than 100 nm. The study by Wijnant et al. showed that nanoparticles less than 100 nm were more effectively adsorbed at the site of infection. Additionally, Danaei et al. demonstrated that small nanoparticles have greater penetration into the dermis upon topical application, which can be effective in treating CL; this finding aligns with our present study (Danaei et al. 2021).

One of the most significant challenges in drug use is toxicity, where sometimes the side effects outweigh their effectiveness. In this study, we evaluated the toxicity of all drugs using the MTT method, and no toxicity was observed in test groups on the L929 cell line or human red blood cells. Most toxins in the human body are metabolized in the liver, where the first signs of toxicity typically occur. After 28 days of outweigh, blood samples were taken from mice, and the levels of AST and ALT enzymes were measured. The results showed that, except for amphotericin B, no toxicity was observed in the studied groups. The highest drug toxicity was associated with amphotericin B; low levels of toxicity were noted in the combination forms. The increase in leishmanicidal effect and reduction in toxicity on human cell lines in the combination form of the drugs represent a significant finding in our current study.

Amphotericin B in this study exhibited less cell toxicity when used with chitosan compared to when it was used alone. Therefore, this combination could reduce the side effects of amphotericin B, which is consistent with findings by Ribeiro et al. (2014). Furthermore, it also reduced the hemolysis rate of red blood cells. Ribeiro et al. (2014) showed that the EC50 of chondroitin sulfate-labeled amphotericin B had a greater efficacyin eliminating the Leishmania parasites compared to amphotericin-B alone, which aligns with our present study. The effects of the synthesized nanocomposite on the Leishmania parasites in thisstudy may also be attributed to chitosan’s properties in activating immune system mechanisms against the parasite. A study by Khademi et al. (2016), showed that nano-chitosan can enhance the Th1 response, an active mechanism in eliminating leishmaniasis. Another study found that chitosan can increase superoxide dismutase activity in the body, seving as a barrier against free radicals and reducing clinical symptoms of the disease while also enhancing macrophage anti-parasitic activity (Wang et al. 2013).

The toxicity of the drugs studied in curremt study was lower than cisplatin (positive control groups) and amphotericin B, even at the highest concentration. Many drugs that are evaluated in various studies have good antimicrobial effects, but in most cases, due to high toxicity, they are not approved for use in humans. Therefore, assessing the toxicity level is of great importance. However, the use of natural ingredients often has fewer side effects, which was also confirmed in this study. Chitosan revealed remarkable cytotoxicity effects against HepG2 (liver cancer), HeLa (cervical cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer) human cancer cell lines but the effectiveness of chitosan towards normal fibroblast cells was negligible (Frigaard et al. 2022).

Findings from both in vitro and in vivo aspects of this study demonstrated that chitosan possesses highly effective leishmanicidal effects, which are notably heightened in the presence of amphotericin B. This study also investigated the toxicity of chitosan in vitro on cell lines and in vivo on liver enzymes, showing that chitosan is not toxic. Therefore, results obtained from this study, combined with findings from other research endeavors, suggest that chitosan can be considered a natural anti-parasitic drug pending further clinical trials. According to the results of this study, it can be suggested to use combined drugs in different ratios for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Considering the role of time, it is possible to use forms of medicine that are exposed to the wound for a longer period of time. Also, along with anti-parasitic compounds, it is appropriate to use supplements to enhance the growth and proliferation of skin cells.

For future investigations, it would be advantageous to explore the optimal dosages and treatment durations of chitosan and chitosan–amphotericin B to maximize efficacy while minimizing potential side effects. Examining the synergistic effects of combination thrapies with other anti-leishmanial agents could also improve healing consequences. Furthermore, organize mechanistic studies to comprehend how chitosan and chitosan–amphotericin B interact with L. major at the molecular level could provide valuable insights. Furthermore, extending the in vivo studies to include different animal models and assessing the long-term safety and efficacy of these treatments are crucial steps towards clinical translation. Finally, evaluating the stability, bioavailability, and pharmacokinetics of chitosan–amphotericin B formulations would be essential for developing an alternative therapeutic products.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks are extended by the authors of this study to the laboratory staff at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and the Toxoplasma Research Center at Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. The methods applied in this study were conducted in strict accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Bahman Rahimi Esboei. Formal analysis: Bahman Rahimi Esboei, Maryam Pourhajibagher. Methodology: Parisa Mousavi, Bahman Rahimi Esboei, Azadeh Zolfaghari. Project administration: Parisa Mousavi, Bahman Rahimi Esboei, Seyed Mahmood Mousavi, Seyed Hossein Hejazi. Resources: Bahman Rahimi Esboei, Seyed Hossein Hejazi. Supervision: Bahman Rahimi Esboei, Seyed Mahmood Mousavi, Seyed Hossein Hejazi. Writing of original draft: Parisa Mousavi, Zabihollah Shahmoradi, Fatemeh Namdar. Design the figures: Parisa Mousavi, Bahman Rahimi Esboei. Writing-review and editing: Parisa Mousavi, Bahman Rahimi Esboei, Maryam Pourhajibagher, Azadeh Zolfaghari, Zabihollah Shahmoradi, Fatemeh Namdar, Fatemeh Parandin, Seyed Mahmood Mousavi. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Skin Diseases and Leishmaniasis Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran [Grant No: IR.MUI. MED.REC.1399.056].

Data availability

This published article encompasses all the data generated or analyzed throughout the duration of this study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for trials involving experimental animals was secured from the Ethics Committee of Research at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Isfahan, Iran), with the ethical code IR.MUI.MED.REC.1399.056. All methods were conducted in strict adherence to international guidelines for ethical conduct in the care and use of animals. The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors of this article agree to submit the article to Parasitology Research Journal.

Competing interests

The authors of declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bahman Rahimi Esboei, Email: Bahman5164@yahoo.com.

Maryam Pourhajibagher, Email: m-pourhajibagher@sina.tums.ac.ir.

Seyed Hossein Hejazi, Email: Hejazi@med.mui.ac.ir.

References

- Al-Salem WS, Solórzano C, Weedall GD, Dyer NA, Kelly-Hope L, Casas-Sánchez A, Alraey Y, Alyamani Essam J, Halliday A, Balghonaim SM (2019) Old world cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment response varies depending on parasite species, geographical location and development of secondary infection. Parasites Vectors 12(1):1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlMohammed HI, Khudair Khalaf A, Albalawi E, Alanazi A, Baharvand AD, Moghaddam P, Mahmoudvand A, H (2021) Chitosan-Based nanomaterials as valuable sources of Anti-Leishmanial agents. Syst Rev Nanomaterials 11(3):689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atan NAD, Koushki M, Ahmadi NA, Rezaei-Tavirani M (2018) Metabolomics-based studies in the field of Leishmania/leishmaniasis. Alex J Med 54(4):383–390 [Google Scholar]

- Batool S, Javaid S, Javed H, Asim L, Shahid I, Khan M, Muhammad A (2022) Addressing artifacts of colorimetric anticancer assays for plant-based drug development. Med Oncol 39(12):198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi K, Chen Y, Zhao S, Kuang Y, Wu CH (2018) Current visceral leishmaniasis research: a research review to inspire future study. BioMed Res Int 2018 (1): 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brito AMG, Dos Santos D, Rodrigues SA, Brito RG, Xavier-Filho L (2013) Plants with anti-Leishmania activity: integrative review from 2000 to 2011. Pharmacogn Rev 7(13):34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung RCF, Ng TB, Wong JH, Chan WY (2015) Chitosan: an update on potential biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. Mar Drugs 13(8):5156–5186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva EC, Rayol CD, Medeiros PL, Figueiredo RCBQ, Piuvezan MR, Brabosa-Filho JM (2012) Anti-leishmanial activity of Warifteine: a bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloid isolated from Cissampelos sympodialis Eichl.(Menispermaceae). Sci World J 12(02):1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaei M, Motaghi MM, Naghmachi Y, Amirmahani F, Moravej R (2021) Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) by filamentous algae extract: comprehensive evaluation of antimicrobial and anti-biofilm effects against nosocomial pathogens. J Nanobiotechnol 76(1):3057–3069 [Google Scholar]

- Date AA, Joshi MD, Patravale VB (2007) Parasitic diseases: liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles versus lipid nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 59(6):505–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmi T, Rahimi-Esboei B, Sadeghi F, Zamani Z, Didehdar M, Fakhar M (2021) In vitro antiprotozoal effects of nano-chitosan on Plasmodium falciparum, Giardia lamblia and Trichomonas vaginalis. Acta Parasitol 66(1):39–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frézard F, Aguiar MM, Ferreira LA, Ramos GS, Santos TT, Borges GS (2022) Liposomal amphotericin B for treatment of leishmaniasis: from the identification of critical physicochemical attributes to the design of effective topical and oral formulations. Pharmaceutics 15(1):99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigaard J, Jensen JL, Galtung HK, Hiorth M (2022) The potential of Chitosan in nanomedicine: an overview of the cytotoxicity of Chitosan based nanoparticles. Front Pharmacol 14(4):24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervazoni LF, Barcellos GB, Ferreira-Paes T, Almeida-Amaral EE (2020) Use of natural products in leishmaniasis chemotherapy: an overview. Front Chem 8:1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goy RC, Britto DD, Assis OB (2009) A review of the antimicrobial activity of Chitosan. Polímeros 19:241–247 [Google Scholar]

- Hadwiger LA, Kendra D, Fristensky B, Wagoner W (1986) Chitosan both activates genes in plants and inhibits RNA synthesis in fungi. Chitin Nat Technology: Springer 13(1):209–214 [Google Scholar]

- Horber F, Lerut J, Jaeger P (1991) Renal tubular acidosis: a side effect of treatment with pentavalent antimony. Clin Nephrol 36(4):213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademi F, Derakhshan M, Sadeghi R (2016) The role of Toll-like receptor gene polymorphisms in tuberculosis susceptibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Clin Med 3(4):133–139 [Google Scholar]

- Lima DS, Gullon B, Cardelle-Cobas A, Brito LM, Rodrigues KAF, Quelemes PV, Ramos-Jesus J, Arcanjo DDR, Plácido A, Batziou K, Quaresma P, Eaton P, Delerue-Matos C, Carvalho FA, da Silva DA, Pintado M, de Leite SA JR (2017) Chitosan-based silver nanoparticles: a study of the antibacterial, antileishmanial and cytotoxic effects. J Bio Comp Polym 32(4):397–410 [Google Scholar]

- Mcgwire BS, Satoskar AR (2014) Leishmaniasis: clinical syndromes and treatment. QJM Int J Med 107(1):7–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi P, Rahimi Esboei B, Pourhajibagher M, Fakhar M, Shahmoradi Z, Hejazi SH (2022) Anti-leishmanial effects of resveratrol and resveratrol nanoemulsion on Leishmania major. BMC Microbiol 22(1):1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najm M, Hadighi R, Heidari-Kharaji M (2021) Anti-Leishmanial activity of Artemisia persica A. spicigera and A. fragrance against Leishmania major. Iran J Parasitol 16(3):464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- No HK, Park NY, Lee SH (2002) Antibacterial activity of Chitosans and Chitosan oligomers with different molecular weights. Int J Food Microbiol 74(1–2):65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özbilgin A, Çavuş İ, Kaya T, Yıldırım A, Harman M (2020) Comparison of in vitro resistance of wild leishmania isolates against drugs used in the treatment of leishmaniasis. Turkiye Parazitol Dergisi 44(1):12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier G, Demar M, Lami P, Zribi A, Marty P, Buffet P, Blaizot R (2022) Leishmaniasis epidemiology in endemic areas of metropolitan France and its overseas territories from 1998 to 2020. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 16(10):e0010745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso G, Petillo O, Ranieri M, Santin M, Ambrosic L, Calabró D, Balsamo G (1994) Chitosan-mediated stimulation of macrophage function. Biomaterials 15(15):1215–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porporatto C, Bianco ID, Riera CM, Correa SG (2003) Chitosan induces different l-arginine metabolic pathways in resting and inflammatory macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 304(2):266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeisi M, Mirkarimi K, Jannat B, Rahimi Esboei B, Pagheh AS, Mehrbakhsh Z, Foroutan M (2020) In vitro effect of some medicinal plants on Leishmania major strain MRHO/IR/75/ER. Med Lab J 14(4):46–52 [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi-Esboei B, Fakhar M, Chabra A, Hosseini M (2013) In vitro treatments of Echinococcus granulosus with fungal Chitosan as a novel biomolecule. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 3(10):811–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi-Esboei B, Mohebali M, Mousavi P, Fakhar M, Akhoundi B (2018) Potent anti-leishmanial activity of Chitosan against Iranian strain of Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER): in vitro and in vivo assay. J Vector Borne Dis 55(2):111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj S, Sasidharan SN, Balaji Dubey WK, Saudagar P (2020) Review on natural products as an alternative to contemporary anti-leishmanial therapeutics. J Proteins Proteom 11(5):135–158 [Google Scholar]

- Ravindranathan S, Koppolu BP, Smith SG, Zaharoff DA (2016) Effect of Chitosan properties on immunoreactivity. Mar Drugs 14(5):91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reithinger R, Dujardin J-C, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S (2007) Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis 7(9):581–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riezk A, Van Bocxlaer K, Yardley V, Murdan S, Croft SL (2020) Activity of amphotericin B-loaded Chitosan nanoparticles against experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Molecules 25(17):4002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi R, Zadeh AG, Afshar MJA, Fakhar M, Keighobadi M, Mohtasebi S, Rahimi-Esboei B (2021) In vivo anti-leishmanial activity of concocted herbal topical Preparation against Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER). Ann Parasitol 67(3):483–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar K, Xue Y, Sant S (2017) Host response to synthetic versus natural biomaterials. The immune response to implanted materials and devices. Springer, Berlin, pp 81–105

- Sundar S, Chakravarty J (2010) Antimony toxic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 7(12):4267–4277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Trinconi CT, Reimão João Q, Yokoyama-Yasunaka JK, Miguel Daniel C, Uliana Sergio R (2014) Combination therapy with Tamoxifen and amphotericin B in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58(5):2608–2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Wen W, Xiong H, Zhang X, Gu H, Wang S (2013) A novel amperometric biosensor for superoxide anion based on superoxide dismutase immobilized on gold nanoparticle-chitosan-ionic liquid biocomposite film. Anal Chim Acta 758(3):66–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarahmadi M, Fakhar M, Ebrahimzadeh Mohammad A, Chabra A, Rahimi-Esboei B (2016) The anti-giardial effectiveness of fungal and commercial Chitosan against Giardia intestinalis cysts in vitro. J Parasitic Dis 40(1):75–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Sharan A, Espinosa SA, Gallego-Perez D, Weeks J (2019) The path toward integration of traditional and complementary medicine into health systems globally: the World Health Organization report on the implementation of the 2014–2023 strategy. J Altern Complement Med 25(9):869–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziani K, Henrist C, Jérôme C, Aqil A, Maté JI, Cloots R (2011) Effect of nonionic surfactant and acidity on Chitosan nanofibers with different molecular weights. Carbohydr Polym 83(2):470–476 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This published article encompasses all the data generated or analyzed throughout the duration of this study.