Abstract

The annexin superfamily proteins, a family of calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding proteins, are involved in a variety of Ca²+-regulated membrane events. Annexin A, expressed in vertebrates, has been implicated in a variety of regulated cell death (RCD) pathways, including apoptosis, autophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and neutrophil extracellular trap-induced cell death (NETosis). Given that inflammation is a key driver of cell death, the roles of Annexin A in inflammation have been extensively studied. In this review, we discuss the regulatory roles of Annexin A in RCD and inflammation, the development of related targeted therapies in translational medicine, and the application of animal models to study these processes. We also analyze current challenges and discuss future directions for improved diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Annexin A, regulated cell death, inflammation, translational medicine

Introduction

Annexins are calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding proteins involved in a wide range of cell membrane-associated processes, including vesicular transport, autophagy, cytotoxicity, membrane-cytoskeletal anchoring, modulation of membrane protein activity, signaling, and inflammatory responses.1 Early annexin nomenclature, primarily based on biochemical properties and functions, was inconsistent. Later, phylogenetic and comparative genomic analyses classified annexins into five categories: Annexin A (vertebrates), Annexin B (invertebrates), Annexin C (fungi, monocytes, and other eukaryotes), Annexin D (plants), and Annexin E (prokaryotes).2 In higher vertebrates, the Annexin A family comprises 12 members (Annexin A1–A13), although the existence of Annexin A12 remains unconfirmed.3 Annexin A family proteins are characterized by a conserved C-terminal core domain and a more variable N-terminal region. The C-terminal core comprises four (or eight in Annexin A6) highly conserved, approximately 70-amino-acid long, repetitive structural domains (I–IV), forming a slightly curved disc. The relatively short N-terminal region, ranging from dozens to hundreds of amino acids, exhibits diverse amino acid sequences. Compared to the C-terminal core, the N-terminal region significantly contributes to structural arrangement, overall stability, specific functions and subcellular localization. Post-translational modifications of the N-terminal region, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and proteolysis, can alter key regions within the core structure of annexins, thereby influencing their function.4,5 Overall, the N-terminal region serves as a crucial regulatory element for the structure and function of annexins. While in vitro functions of annexins are well-studied, research into their in vivo physiological roles remains in its infancy.

Annexins facilitate the organization of cell membranes and the cytoskeleton. Upon binding to phospholipids, they modulate the formation of bilayer membrane structures through lateral aggregation and stabilize the lipid bilayer.6 Furthermore, annexins are involved in cellular signal transduction. For example, overexpression of Annexin A1 activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase/ mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK-MAPK) and T-cell receptor signaling pathways, binds to Formyl Peptide Receptor 1 (FPR1), and upregulates nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), thereby promoting T-cell proliferation and differentiation, exerting an anti-inflammatory effect.7 Annexin A4 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis through activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.8 Annexin A6 has been shown to act as a scaffold protein for Protein Kinase C (PKC) and p120 GTPase-activating proteins, negatively regulating the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/Ras/MAPK pathway and promoting EGFR lysosomal degradation.9 Annexin A5, the most abundant annexin in most cells and tissues, is also found extracellularly. Its high affinity for phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane makes it a widely used marker of for detecting apoptotic cells in various disease contexts.6 Over the past decade, research on the association between annexins and RCD has largely focused on apoptosis. However, annexins are now known to participate in other forms of RCD (Table 1). Apoptosis, autophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis and NETosis are well-characterized pathways regulating cell death, contributing to the clearance of pathogens and potentially tumor cells, and playing crucial roles in in vivo homeostasis, host defense, cancer development, and a wide range of pathophysiological processes.10 These RCD pathways often interact and exhibit antagonism, responding to diverse stimuli at different stages of cellular metabolism. This interplay is essential for normal cellular function. While apoptosis has been extensively studied in relation to annexins, research on the involvement of annexins in other RCD modalities, including autophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis and NETosis, remains in its early stages. Future research should prioritize these less-explored areas of RCD. In addition to their influence on cell fate decisions, annexins also directly participate in the modulation of inflammatory processes.11,12 Considering the complex interactions between inflammation and RCD, the involvement of annexins in these two processes is especially significant. By influencing the mode of cell death and the consequent release of inflammatory mediators, Annexin A family proteins can influence the pathogenesis, development, and resolution of a wide range of diseases.13–15 Consequently, an in-depth study of the underlying mechanisms by which Annexin A family proteins operate in RCD, inflammation, and disease is of great significance for the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Table 1.

Annexin A Expression and Link to Regulated Cell Death

| Annexin | Expression in Cells | Regulatory RCD | REF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annexin A1 | Expressed in most cells and highly prominent in differentiated cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils |

Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (√) Pyroptosis (√) Ferroptosis (\) NETosis (√) |

[16–19] |

| Annexin A2 | Expressed in most cells, especially in endothelial cells, monocytes and macrophages |

Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (√) Pyroptosis (√) Ferroptosis (√) NETosis (\) |

[20–23] |

| Annexin A3 | Expressed in most cells | Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (√) Pyroptosis (√) Ferroptosis (√) NETosis (\) |

[24–27] |

| Annexin A4 | Expressed in most cells and prominent in secretory epithelial cells |

Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (\) Pyroptosis (\) Ferroptosis (\) NETosis (\) |

[28] |

| Annexin A5 | The most abundant annexin is expressed in external cells except neurons |

Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (√) Pyroptosis (\) Ferroptosis (√) NETosis (√) |

[29–32] |

| Annexin A6 | The expression of most cells is abundant in endothelial cells, hepatocytes and macrophages, but low in epithelial cells of intestinal tissues and parathyroid glands |

Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (√) Pyroptosis (\) Ferroptosis (\) NETosis (\) |

[33,34] |

| Annexin A7 | Expressed in most cells | Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (√) Pyroptosis (\) Ferroptosis (\) NETosis (\) |

[35] |

| Annexin A8 | Endothelial cells; epithelial cells | Apoptosis (\) Autophagy (√) Pyroptosis (\) Ferroptosis (√) NETosis (\) |

[36,37] |

| Annexin A9 | Low abundance | Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (\) Pyroptosis (\) Ferroptosis (\) NETosis (\) |

[38] |

| Annexin A10 | Epithelial cells | Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (√) Pyroptosis (\) Ferroptosis (√) NETosis (\) |

[39–41] |

| Annexin A11 | Expressed in most cells | Apoptosis (√) Autophagy (\) Pyroptosis (\) Ferroptosis (\) NETosis (\) |

[42] |

Relationship Between Annexin A and RCD

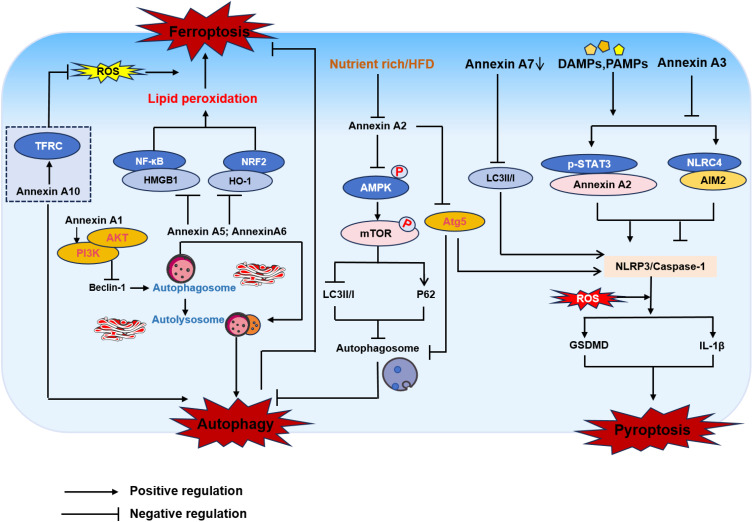

Annexin A plays a crucial role in regulating RCD processes. Specifically, annexins bind to the plasma membrane and participate in membrane remodeling and permeability changes, thereby influencing the balance of ion concentrations within the cell. These changes can activate or inhibit key regulatory proteins, such as caspases, which, in turn, initiate or suppress RCD signaling pathways. Furthermore, Annexin A can prevent the formation of apoptotic bodies by inhibiting the externalization of membrane phospholipids and reducing phagocytosis. Annexin A also directly binds to cytochrome c and inhibits its release, thereby inhibiting mitochondrial-mediated regulated cell death.43 Based on current studies, the regulatory mechanisms of Annexin A in RCD are summarized below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annexin A regulates regulated cell death patterns such as autophagy, ferroptosis, and pyroptosis. Annexin A1 activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of autophagy. Annexin A2 regulates autophagy flow by blocking AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. Annexin A5 and A6 play a role in the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. Knockdown Annexin A10 inhibits autophagy mediated TFRC degradation induced ferroptosis. p-STAT3 promotes Annexin A2 expression at the transcriptional level, thereby activating caspase-1 to mediate pyroptosis. Annexin A2 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation through Atg5-dependent autophagy, ultimately leading to pyroptosis. Annexin A7 decreases autophagy-induced NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis in epithelial cells. Annexin A3 can inhibit pyroptosis via the NLRC4/AIM2 axis.

Abbreviations: Inhibition of TFRC, transferrin receptor; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; HMGB1, high mobility group box-1 protein; NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1, heme Oxygenase 1; Mtor, mammalian target of rapamycin; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; NLRC4, NLR family, CARD domain-containing protein 4; AIM2, abstract in melanoma 2.

Apoptosis

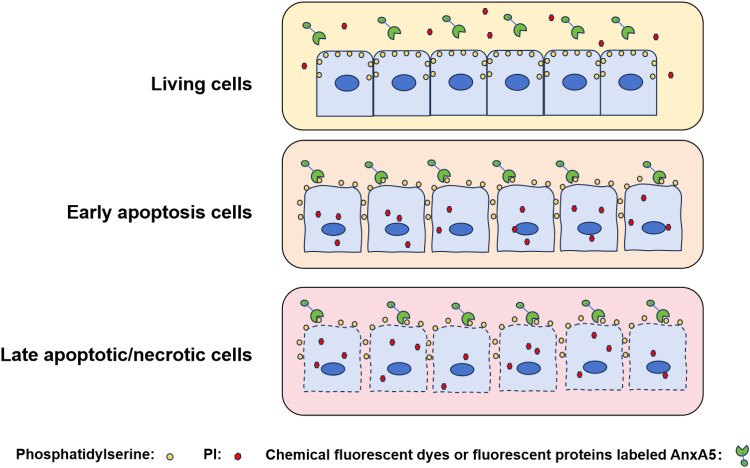

Apoptosis, a form of regulated cell death, is characterized by distinct morphological hallmarks, including cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and the formation of membrane blebs, ultimately leading to the generation of apoptotic bodies. These apoptotic bodies are efficiently recognized and phagocytosed, thereby preventing the release of intracellular constituents and limiting the induction of inflammation.10 A key event in apoptosis is the translocation of PS, a negatively charged phospholipid, from the inner to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. This PS externalization serves as a critical signaling cue, promoting the recognition and engulfment of apoptotic cells by phagocytes.44 The subsequent recognition and engulfment of apoptotic cells by phagocytes, often mediated by binding to PS, leads to the formation of apoptotic bodies. Furthermore, rapid membrane repair, crucial for cell survival following membrane rupture, involves Annexin A binding to PS, inducing membrane cross-linking and fusion—key steps in this process.45 This mechanism prevents the release of intracellular contents, thereby minimizing the risk of a pro-inflammatory response. Notably, Annexin A5 exhibits a high calcium-dependent affinity for PS. This property has made Annexin A5 a widely used tool for detecting apoptotic cells, and numerous commercially available products are available for research applications.46,47 Combined with propidium iodide (PI) staining, fluorescently labeled Annexin A5 enables the discrimination of live and apoptotic cells using fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry (Figure 2), further highlighting its utility in apoptosis research.48 Conversely, Annexin A1 functions as an anti-apoptotic protein; its downregulation disrupts cancer cell homeostasis, leading to cell cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis.49 Annexin A2 accumulates in apically extruded transformed cells, contributing to resistance against reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced apoptosis by suppressing p38-MAPK, a stress-activated protein kinase.20 Studies investigating the effects of Annexin A3 downregulation on HepG2 cells revealed that it promoted apoptosis and chemoresistance by increasing Bax expression, decreasing Bcl-2 expression, and inactivating caspase-9 and caspase-3 in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.24 Similarly, Annexin A4 influences cell growth, invasion, and apoptosis. Overexpression of Annexin A4 may promote trophoblast proliferation and invasion, and alleviate the progression of preeclampsia in a rat model, potentially via activation of the PI3K/AKT/eNOS pathway, a cell survival pathway known to inhibit apoptosis.28 Annexin A6, a highly abundant cardiac membrane protein found in various cardiac cell types including myocytes, plays a key role in the transition of chronically hypertrophied cardiomyocytes to apoptosis.33 Dysregulation, heterozygous deletion, and altered subcellular localization of Annexin A7 have been implicated in the development, invasion, metastasis, and apoptosis of various cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma,50 gastric cancer,51 lung cancer,52 multiple myeloma53 and other malignancies. Recent research has increasingly focused on Annexin A9 and A10, primarily in the context of cancer. Sequence analysis suggests that Annexin A9 is a target of miR-186-5p. Subsequent experiments revealed that miR-186-5p promotes apoptosis through the downregulation of Annexin A9, while reintroduction of Annexin A9 can rescue apoptosis induced by miR-186-5p, thereby promoting breast cancer cell survival.54 Annexin A10 has been implicated in the apoptosis of thyroid39 and gastric cancer cells,55 etc. Annexin A11 may play a significant role in hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis and progression. In vitro studies show that knockdown of Annexin A11 inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis in human cholangiocarcinoma-derived fibroblast cell lines through modulation of Akt2/ Forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1) and/or Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression.42 Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of annexins structure, function, and dynamics, leading to a more nuanced appreciation of the biological roles of Annexin A in apoptosis and other RCD processes.

Figure 2.

The principle of apoptosis detection using Annexin A5 probes.

Autophagy

Autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved eukaryotic degradation pathway, maintains intracellular homeostasis through lysosomal degradation of damaged or superfluous organelles and proteins. While autophagy is generally considered a pro-survival mechanism, impairment of autophagy or excessive autophagic flux can trigger cell death.56 Despite recent advances in understanding the regulation and fundamental molecular mechanisms of autophagy, many questions remain unresolved. Specifically, how does autophagy regulate cell death, and what are the finely tuned regulatory mechanisms governing autophagy-dependent cell death (ADCD) and autophagy-mediated cell death (AMCD)?57 Here, we highlight the diverse roles of Annexin A in modulating autophagy’s impact on other cell death modalities, providing a novel perspective on autophagy-related cell death. Recent studies indicate that Vibrio vulnificus metalloprotease (VvpM) recruits Annexin A2 to lipid rafts, thereby regulating NF-κB-dependent IL-1β production. Additionally, VvpM interacts with Annexin A2 outside of lipid rafts to promote the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation through autophagy-related gene 5 (Atg5)-dependent autophagy, ultimately resulting in pyroptosis.58 Annexin A3 has been implicated in sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, where its overexpression inhibits PKCδ/p38-mediated apoptosis, promotes autophagy, and enhances cell survival. In HCC patient liver specimens, Annexin A3 expression correlated positively with microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (LC3B), a marker of autophagy, and reduced overall survival in sorafenib-treated patients. Annexin A5 has been proposed to facilitate autophagosome-lysosome fusion, rather than directly influencing lysosomal degradation capacity.59 Annexin A6 has been identified in autophagic vesicles of rat hepatocytes, suggesting a role in autophagosome-lysosome fusion.60 Autophagy is regulated by the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway.61 Sun et al62 reported that Annexin A6 expression inhibits AKT/mTOR-mediated autophagy activation, thus affecting cervical cancer progression. Given that Annexin A6 is believed to contribute to the organization of membrane microdomains and regulate vesicle fusion, its influence on autophagy flux could potentially impact cellular stress and survival; however, direct evidence linking it to autophagy-dependent cell death remains limited. Furthermore, in an (apoE⁻/⁻) mouse model of atherosclerosis, Annexin A7 was identified as an endogenous regulator of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C (PC-PLC), an enzyme implicated in the modulation of autophagy. While decreased Annexin A7 GTPase activity inhibits PC-PLC levels and activity, promoting autophagy and suppressing apoptosis, this ultimately contributes to the inhibition of atherosclerosis development and progression.63 These findings suggest a protective rather than a cell death-promoting role for Annexin A7-mediated autophagy in this context. Additionally, attenuating NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated epithelial cell pyroptosis contributes to the maintenance of intestinal barrier function in Crohn’s colitis, and mechanistic studies exploring this found that it was achieved by modulating Annexin A7 to promote autophagy.64 The observation that Annexin A10 knockdown resulted in increased autophagic flux and accumulation of sequestosome 1, an autophagy receptor, strongly indicates that Annexin A10 influences autophagy. This disruption of autophagy, specifically the inhibition of autophagy-mediated transferrin receptor degradation, plays a critical role in the subsequent induction of ferroptosis. Furthermore, Annexin A1, A5, and A6 participate in autophagosome-lysosome fusion; and Annexin A2 regulates autophagosome formation by trafficking autophagy-related gene 9A (Atg9A) from endosomes to autophagosomes via actin.65 Further research is needed to fully elucidate the specific mechanisms by which these annexins regulate autophagy, and whether such regulation contributes to autophagy-dependent cell death in different cellular contexts.

Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, is characterized by the accumulation of ROS and the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in cellular membranes. This process disrupts membrane integrity via phospholipid peroxidation, leading to membrane rupture, intracellular content release, and subsequent inflammatory responses that contribute to disease pathogenesis.66 Various stimuli, including ferroptosis inducers (eg, Erastin and RSL3), clinically approved drugs (eg, sorafenib, sulfasalazine, statins, and artemisinin), ionizing radiation, and cytokines (eg, INF-γ and TGF-β1), can induce ferroptosis in tumor cells, thereby influencing tumor growth.67–69 Annexin A is increasingly implicated in basic research, including studies of ferroptosis. High-throughput analysis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and ferroptosis revealed that Annexin A2 promotes ferroptosis in HepG2 cells, contributing to the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.23 Annexin A3-rich exosomes derived from tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) inhibited ferroptosis in laryngeal cancer cells. Mechanistically, Annexin A3 primarily inhibits activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) ubiquitination, thereby stabilizing its function. Stabilized ATF2 then suppresses the expression of ChaC glutathione-specific γ-glutamyl cyclotransferase 1 (CHAC1), leading to elevated intracellular glutathione levels, reduced lipid peroxidation, and ultimately inhibiting ferroptosis.27 In a mouse model of traumatic brain injury, Annexin A5 demonstrates neuroprotective effects by modulating key pathways involved in the injury response. Specifically, Annexin A5 attenuates neuroinflammation by suppressing NF-κB/high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) signaling, a pathway known to promote inflammatory cytokine production. HMGB1, a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecule, is released during injury and exacerbates inflammation.70 Concurrently, Annexin A5 mitigates oxidative stress and ferroptosis by enhancing the NRF2/HO-1 antioxidant system, thereby bolstering cellular defense against reactive oxygen species.31 TFAP2A is an upstream transcription factor of Annexin A8, which plays a role in regulating ferroptosis. In cervical squamous cell carcinoma, Annexin A8, transcriptionally activated by TFAP2A, maintains glutathione levels, thereby reducing the susceptibility of cervical squamous cell carcinoma cells to ferroptosis induced by specific inducers.37 Annexin A10 knockdown inhibits colorectal cancer progression by inducing ferroptosis through inhibiting transferrin receptor (TFRC) degradation; this Annexin A10-TFRC-ferroptosis axis represents a potential therapeutic target in serrated pathway colorectal cancer.40 These findings suggest that Annexin A may represent promising therapeutic targets for modulating ferroptosis. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise molecular targets and comprehensive mechanisms of Annexin A action in ferroptosis.

Pyroptosis

Pyroptosis, a lytic form of RCD, is characterized by cellular swelling, membrane blebbing, and eventual cell rupture, which releases intracellular contents and triggering a robust inflammatory response.71 While sharing some features with apoptosis and necrosis, including nuclear condensation, DNA fragmentation, and phospholipid externalization, pyroptosis is distinguished by scanning electron microscopy findings of swollen cells with nonselective pores. These cells form ‘pyroptotic body’-like vesicles that ultimately undergo plasma membrane rupture and release inflammatory mediators. Pyroptosis is primarily categorized into the Caspase-1-dependent classical pathway and the Caspase-4/5/11-reliant non-classical pathway.72 Caspase-1-dependent classical pathway: In response to signals from bacteria and viruses, intracellular pattern recognition receptors function as receptors, recognizing these signals and binding to the precursor of Caspase-1 via the adaptor protein ASC to form a multiprotein complex. This complex activates Caspase-1, which cleaves Gasdermin D (GSDMD) to produce a peptide containing the active domain at the nitrogen terminus, leading to perforation of the cell membrane, cell rupture, release of cellular contents, and triggering an inflammatory response. Additionally, activated Caspase-1 cleaves the precursors of IL-1β and IL-18 to produce active IL-1β and IL-18, which are released extracellularly to recruit inflammatory cells, thereby amplifying the inflammatory response. Caspase-4/5/11-dependent non-classical pathway: Caspase-4, 5, and 11 are activated in response to signals such as bacteria. The activated Caspase-4/5/11 then cleave GSDMD to form peptides containing the active domain at the nitrogen terminus, which induces perforation of the cell membrane, cell rupture, and release of cellular contents, resulting in an inflammatory response. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a regulated protein complex that detects injury and enhances the inflammatory response via caspase-1 activation, cleavage of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, and the induction of pyroptosis.73 Furthermore, NLRP3 inflammasome activation promotes the production of lipid mediators, such as eicosanoids and ceramides, which participate in metabolic and immune signaling and are dysregulated under conditions of excessive NLRP3 inflammasome activation.74 Annexin A1 deficiency exacerbates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation and lipid mediator (eg, ceramide) production, promoting NLRP3 inflammasome activation in response to nigrosomal stimulation.18 Annexin A2 promotes pyroptosis by assembling a lipid raft-dependent ROS-generating complex. Within lipid rafts, Annexin A2 recruits NADPH oxidase 2 and neutrophil cytosolic factor 1, amplifying ROS production. This Annexin A2-mediated ROS surge activates NF-κB, enhancing IL-1β transcription and subsequent pyroptosis execution. Thus, Annexin A2 acts as a key regulator, driving inflammatory cell death via a lipid raft/ROS/NF-κB/IL-1β cascade.75 Bioinformatic analyses suggest a role for Annexin A2 in hepatic steatosis, potentially by regulating plasma cholesterol clearance.76 Moreover, in vivo and in vitro studies indicate that elevated Annexin A2, transcriptionally upregulated by p-STAT3, potently activates caspase-1 and inflammasomes, ultimately driving hepatocyte pyroptosis and liver fibrosis.22 Annexin A3 has been identified as a potential genetic marker for pyroptosis in ischemic stroke, and it inhibits pyroptosis by suppressing the NLRC4/AIM2 axis (pyroptosis-related factors).26 Although less studied, the role of annexins in pyroptosis warrants further investigation, given their potential to modulate GSDMD-mediated membrane permeabilization and cell lysis.

NETosis

NETosis refers to a controversial type of RCD in neutrophils, characterized by the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).56 NETs are web-like structures composed of chromatin and histones complexed with granule and cytoplasmic proteins. They are formed in response to microbial and sterile signals, including receptor activation such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and provide a stable platform for capturing and degrading microbes. A significant portion of the nucleic acids in NETs originates from mitochondria. NETs play a crucial role in host defense by trapping and killing pathogens, but excessive or dysregulated NETs formation contributes to various inflammatory diseases and tissue damage, including diabetes and cancer.77,78 While the involvement of annexins in other forms of regulated cell death is increasingly understood, their role in NETosis and NETs-related processes is only beginning to be explored. Several Annexin A family members, particularly Annexin A1 and Annexin A5, are associated with neutrophil function and inflammation, suggesting their potential involvement in NETs-related pathways. Traditionally, Annexin A1 has been considered an anti-inflammatory molecule that, in neutrophils, inhibits activation and recruitment while accelerating apoptosis, thereby promoting resolution of inflammation.79 In myocardial infarction models, upregulated Annexin A1 can inhibit NETosis via its receptor, FPR2, thereby attenuating myocardial injury.80 However, proteomic analyses have identified Annexin A1 as a significant component of NETs, particularly in lupus nephritis, challenging this solely anti-inflammatory role. Within NETs, Annexin A1 undergoes citrullination at arginine 188. This citrullination, which is associated with autoimmunity as it generates neoepitopes that can induce autoantibody production, may be linked to Annexin A1’s function. Through its incorporation and citrullination within NETs, Annexin A1 could potentially promote the formation of autoantibodies against NETs components, thereby contributing to the development of autoimmune diseases.19 Annexin A5, due to its high affinity for PS, plays a crucial role in NETs-related coagulation and inflammation. In COVID-19 patients, PS-containing microparticles can induce neutrophil adhesion and NETosis, whereas Annexin A5 can inhibit these pro-inflammatory and pro-NETosis effects by binding to these microparticles.81 Intriguingly, Annexin A5 plays a critical role in S100A12-induced NETosis and the exacerbation of acute myocardial infarction. The interaction of S100A12 and Annexin A5 enhances calcium influx, leading to calcium overload in neutrophils, promoting NETosis and subsequent cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction.32

In summary, Annexin A exhibits a diverse range of functions across various forms of regulated cell death. By modulating the initiation, execution, and resolution phases of apoptosis, autophagy, ferroptosis, pyroptosis and NETosis, Annexin A family members exert significant control over cell fate decisions. These multifaceted actions highlight the importance of Annexin A as a key regulator of regulated cell death, influencing not only the mode of cell demise but also the subsequent cellular and tissue responses, including inflammation. Given the intricate link between regulated cell death and inflammation, the following section will explore the specific roles of Annexin A in modulating inflammatory pathways.

Annexin A and Inflammation

Emerging evidence indicates that Annexin A1, A2, and A5 play significant roles in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. While leukocyte recruitment to injured or infected tissues is crucial for tissue repair and pathogen clearance, excessive or chronic inflammation contributes to tissue damage and diseases such as arthritis, atherosclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and COVID-19.82 The inflammatory response, a protective mechanism activated in response to injury or infection, significantly influences on cellular fate decisions. On the one hand, inflammation can initiate intracellular apoptotic signaling cascades, leading to the elimination of compromised or infected cells. On the other hand, inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ, may also promote inflammatory cell death modalities, such as necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis.83,84 Moreover, inflammation can modulate autophagic processes. While moderate inflammation may stimulate autophagy to facilitate the clearance of damaged organelles and protein aggregates, excessive inflammation can suppress autophagy, resulting in the accumulation of intracellular debris.85 Annexin A functions as critical intermediary between inflammation and cell fate, regulating the magnitude and duration of inflammatory responses and consequently impacting cellular survival or death. For instance, Annexin A1 mitigates inflammation and safeguards cells by suppressing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and augmenting the production of anti-inflammatory mediators.18 Conversely, Annexin A can directly influence apoptosis, autophagy, and necrosis. As an example, Annexin A5 promotes the efficient removal of apoptotic cells by binding to PS, thereby dampening the inflammatory response. Investigating the regulatory mechanisms of Annexin A in inflammation may provide further insights into their role in regulating RCD.

Annexin A1’s anti-inflammatory properties stem from its modulation of leukocyte-mediated immune responses. As a glucocorticoid-regulated protein, Annexin A1 limits neutrophil recruitment, promotes neutrophil apoptosis, and induces macrophage reprogramming towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype (characterized by the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β), thereby facilitating the resolution of inflammation and suggesting its therapeutic potential in inflammatory diseases. Annexin A1’s anti-inflammatory actions include inhibiting inducible nitric oxide synthase in LPS-stimulated macrophages, which reduces nitric oxide release and promotes IL-10 production.86 Furthermore, Annexin A1 activation of FPR2 homodimers on mononuclear phagocytes triggers anti-inflammatory responses, including the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines and the inhibition of neutrophil recruitment.79 In the early stages of atherosclerosis, adhesion of monocytes to the vascular endothelium is a critical step. In a hypercholesterolemic mouse model, Annexin A1 inhibited leukocyte recruitment to the carotid arteries,87 inversely correlating with atherosclerotic lesion severity.88 High LDL levels activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, promoting caspase-1 activation and subsequent inflammation.89 NLRP3 senses inflammatory signals in macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils, which then promote the release of IL-1β and IL-18 from these cells.90 While Annexin A1 co-localizes with and binds NLRP3, its anti-inflammasome activity is independent of FPR2 signaling. Annexin A1 deficiency enhances IL-1β production by increasing macrophage NLRP3 expression.91 The N-terminal portion of Annexin A1 is known as the Ac2-26 peptide, mimics the full-length protein’s effects on maintaining intestinal homeostasis, particularly during mucosal inflammation, by preserving epithelial integrity and modulating inflammatory factor expression.92 Polymeric Annexin A1 nanoparticles demonstrate therapeutic efficacy in models of peritonitis,93 colonic wound healing,94 and atherosclerosis.94 The significant therapeutic potential of Annexin A1 in inflammatory diseases is driving the development of pharmaceutical formulations, which will be discussed in subsequent sections.

Similarly, Annexin A2 also modulates monocyte and macrophage activation and inflammatory responses. Swisher et al95 demonstrated that the Annexin A2-S100A10 heterotetramer activates human macrophages, promoting infiltration via NF-κB signaling and the release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. S100A10 knockdown significantly reduced LPS-induced production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10, suggesting the Annexin A2-S100A10 heterotetramer is a potential anti-inflammatory therapeutic target.96 Annexin A2’s multifaceted roles in respiratory viral infections and inflammation suggest potential antiviral therapeutic strategies for viral pneumonia. Specifically, Annexin A2 enhances cytomegalovirus infection and gene expression,97 while cytomegalovirus infection upregulates cell surface Annexin A2, which subsequently activates γδ T cells via γδ T cell receptor recognition, inducing oxidative stress and inflammation.98,99 Expanding on the role of Annexin A2 in viral infection, Fang et al100 identified autoantigens associated with SARS-CoV infection. Antibodies in the sera of SARS patients were co-localized with anti-S2 antibodies on human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line A549 cells, and both shared the same cell membrane binding site as the anti-Annexin A2 antibodies. Annexin A2, as part of the Annexin A2-S100A10 heterotetramer, functions as a key extracellular binding partner for both pathogen and host proteins and is subject to shedding or secretion.101 Its interaction with nuclear endosomes negatively regulates TLR4-mediated inflammation,102 suggesting a crucial role for Annexin A2 in modulating infection-induced inflammation and preventing excessive inflammatory responses.

Annexin A5’s anti-inflammatory properties are well-established, particularly given the crucial role of macrophages in inflammatory diseases. Atherosclerosis, characterized by T cell and monocyte/macrophage infiltration into the arterial intima, provides a relevant model. Numerous studies demonstrate an inverse correlation between Annexin A5 expression and both monocyte recruitment and plaque macrophage content, highlighting its anti-inflammatory effects. Annexin A5 exerts anti-inflammatory effects in multiple disease models. For example, in a murine model of atherosclerosis, Annexin A5 reduced both local and systemic inflammation and improved vascular function.103 In a nonalcoholic steatohepatitis model, Annexin A5 dose-dependently decreased TNF-α while increasing IL-10 secretion, promoting an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype. In osteoarthritis, Annexin A5 promoted Toll-like receptor 4 internalization and lysosomal degradation via calcium-dependent endocytosis, inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization, reducing pro-inflammatory mediator release and ROS production, and ultimately mitigating synovial inflammation and cartilage damage.104 Furthermore, Annexin A5 inhibition exacerbated LPS-induced lung inflammation in an acute lung injury model, reinforcing its potential as an anti-inflammatory therapeutic target.105

Annexin A as a Novel Target for Disease Treatment

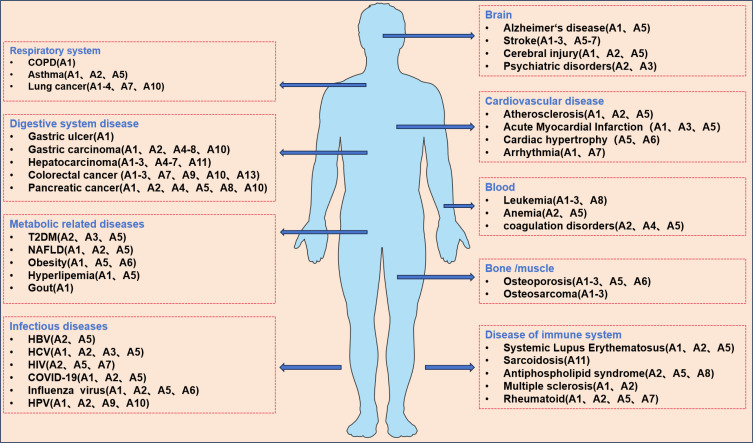

Altered expression of Annexin A in various disease tissues and cells (Figure 3) suggests its potential utility as a biomarker for disease onset, progression, and treatment response. However, the studies presented here are illustrative examples of Annexin A’s potential role in common diseases and cancers and do not encompass the full scope of its involvement.

Figure 3.

Overview of diseases associated with changes in annexin expression levels.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; HBV, hepatitis C virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HPV, human papillomavirus.

Annexin A1, an endogenous anti-inflammatory mediator, plays a crucial role in resolving multi-organ inflammation. In a high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy mouse model, Annexin A1 deficiency exacerbated renal injury, characterized by increased proteinuria, glomerular dilation, tubulointerstitial lesions, and inflammation/fibrosis. And Annexin A1 overexpression attenuated renal injury by binding to NF-κB p65, inhibiting its activation, thereby reducing the release of pro-inflammatory factors and alleviating the inflammatory response.106 Given the significant impact of viral infections in recent years, Cui et al107 investigated Annexin A1’s role in influenza A virus infection. Using RNA sequencing to analyze changes in the autophagy pathway in infected cells, they demonstrated Annexin A1’s crucial role in enhancing autophagy. Annexin A2 serves as a marker for various cancers. The Annexin A2-S100A10 heterotetramer promotes fibronectin production, contributing to tumor invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis, as well as hemorrhagic disorders and inflammation. Dallacasagrande et al108 comprehensively reviewed Annexin A2’s anti-inflammatory functions in acute and chronic inflammation. In acute inflammation, Annexin A2’s membrane repair activity modulates inflammation by repairing lysosomes, regulating inflammasome activation, and influencing autophagosome biogenesis. In chronic inflammation, Annexin A2 promotes angiogenesis and tissue repair. In the context of cancer, it has been found that ginsenoside compound K binds to Annexin A2, disrupting its interaction with the NF-κB p50 subunit and nuclear co-localization, thereby suppressing NF-κB activation, downstream gene expression, and caspase-9/3 activation, ultimately leading to the induction of apoptosis and the suppression of tumor growth and metastasis.109 Furthermore, in Her2-negative breast cancer, Praveenkumar et al110 proposed Annexin A2 as a potential tissue and serum biomarker and therapeutic target. Annexin A5 has been implicated in a wide range of diseases, both neoplastic and non-neoplastic, demonstrating significant potential in in vitro and clinical diagnostics, as well as therapeutics (see for a detailed review111). Research on Annexin A6 has largely focused on cancer. Korolkova et al112 extensively reviewed its contributions to cancer progression. Emerging research, however, suggests a potential link between Annexin A6, hypolipidemia, and major depressive disorder.113 In Annexin A6-deficient hepatocytes, insulin fails to suppress glucose production, suggesting a role for Annexin A6 in regulating glycolipid metabolism and maintaining homeostasis.114 Annexin A1, A2, A5, and A7 are implicated in various aspects of atherosclerosis and acute myocardial infarction pathogenesis. Emerging evidence suggests that Annexin A, rather than merely participating in atherogenesis, actively drive its progression, making them potential therapeutic targets.6 Annexin A9 has also been studied in diseases, primarily cancer. In breast cancer, Annexin A9 downregulation inhibits xenograft tumor growth and lung metastasis.115 Mechanistically, Annexin A9 regulates the AKT/mTOR/STAT3 pathway via calbindin A4, modulating p53/Bcl-2-mediated apoptosis. Furthermore, Annexin A9 facilitates calbindin A4 secretion into the tumor microenvironment, where phosphorylation at serine 2 and threonine 69 promotes the release of pro-angiogenic cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 and 5). In HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, Annexin A9 and A10 expression correlate with histologic grade.116 Dysregulation and mutation of Annexin A11 are implicated in autoimmune diseases117 and in the development of cancer, chemoresistance, and recurrence.118 Across a spectrum of diseases, including inflammatory disorders, cancers, and neurodegenerative conditions, Annexin A exhibits altered expression and exert significant influence on disease progression through their modulation of regulated cell death and inflammation. These findings support the exploration of Annexin A as therapeutic targets for a wide range of conditions. Continued research into the specific roles of Annexin A in different disease contexts will be crucial for the development of effective and targeted therapies.

Translational Medicine Exploration Based on Annexin A

Annexin A Animal Models

Translational medicine bridges basic and clinical research through a reciprocal cycle of investigation, moving from bench to bedside and back again. Although the importance of translational research is widely acknowledged, achieving seamless integration between basic and clinical studies remains a significant challenge. Preclinical studies using diverse animal models have been invaluable in advancing our understanding of disease pathophysiology and human anatomy, contributing significantly to medical progress. Translational research in inflammation is a rapidly growing field. Applying a translational medicine approach to inflammatory disease treatment, which integrates basic science and clinical practice, and utilizing large animal models (eg, pigs, dogs, and non-human primates) could accelerate clinical translation.

While knockout mouse models for several Annexin A family members (A1, A2, A4, A5, A6, and A7), including some double-knockout models, have been generated and characterized, these animals typically exhibit normal viability, fertility, and behavior, limiting their utility in certain translational studies.119 Initial findings suggested that Annexin A primarily modulated biological functions rather than acting as essential mediators or effectors. However, studies using various Annexin A knockout (KO) mouse models have revealed crucial in vivo functions for these proteins. This section summarizes the phenotypes of Annexin A KO mice to elucidate in vivo roles and regulatory mechanisms in disease pathogenesis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Annexin A Knockout Mouse Disease Model Study

| Model | Disease and Mechanism | |

|---|---|---|

| Annexin A1 | ◆Annexin A1 KO-mice | ◆Myocardial infarction (MI): Stimulated cardiac macrophages, inducing neovascularization and cardiac repair;120,121 ◆Pancreatic cancer: Maintains cytoskeletal integrity and promotes migration and invasion;122 ◆Infections and parasitic diseases (eg: Leishmaniasis):Inhibits neutrophil hyperinfiltration and promotes macrophage transformation to an anti-inflammatory phenotype;123 ◆Type 1 diabetes (T1DM): Protects against cardiac and renal dysfunction by returning MAPK signalling to baseline and activating pro-survival pathways (Akt);124 ◆Muscle injury: Cell–cell fusion;125 |

| Annexin A2 | ◆Annexin A2/ApoE Double-KO mice ◆Annexin A2 KO-mice |

◆Atherosclerosis: Suppressed integrin α5 signaling caused by oscillary shear stress;126 ◆Sepsis: Increased IL-17 and reactive oxygen species production;127 ◆Preeclampsia: Impaired decidualization of endometrial stromal cells and uterine environment; Annexin A2 acts as adhesion molecule during implantation;128 |

| Annexin A5 | ◆Annexin A5 KO-mice ◆Lack of phenotype in Annexin A5 and Annexin A5/A6 double-KO mice |

◆Skin wound repair: Membrane repair;129 ◆Immune: Regulates the immune response to foreign cells;130 ◆Bone and cartilage development: Regulation of Ca2+ influx;131 |

| Annexin A6 | ◆Annexin A6 KO-mice | ◆Osteoarthritis: Loss of Annexin A6/p65 (NF-κB) interaction;132 ◆Liver regeneration: Loss of alanine uptake and SNAT4 transporter cell surface localization;133 ◆Osteoarthritis: Increased cation channel Piezo2 activity in sensory neurons;134 ◆Insulin resistance: Loss of Annexin A6 scaffold and membrane transport functions;114 |

| Annexin A7 | ◆Annexin A7 KO-mice | ◆Insulin sensitivity: Annexin A7 influences insulin sensitivity of cellular glucose uptake and thus glucose tolerance;135 ◆ Tumors: Loss of Annexin A7 GTPase activity;136 |

Prospects for the Development of Novel Protein-Engineered Drugs and Technologies Based on Annexin A

Annexin A exhibits diverse biological functions, including PS binding, apoptosis detection, cell membrane repair, modulation of inflammation and coagulation, and participation in disease pathogenesis. These diverse roles have led to applications in in vitro and clinical diagnostics, as well as therapeutics. Existing research has spurred the development of various Annexin A -based drug delivery strategies—including small molecule, nucleic acid, peptide, hydrogel, antibody, and cell-based approaches—for preclinical and clinical applications. Here, we discuss key advances and emerging concepts in tissue-specific drug delivery strategies and their clinical translation.

Glucocorticoids are highly effective in treating inflammatory diseases, but their significant side effects necessitate the development of safer alternatives. The discovery of glucocorticoid-regulated anti-inflammatory proteins, such as Annexin A1, has opened new avenues for anti-inflammatory therapies. Extensive research has characterized Annexin A1 and its bioactive peptides, particularly the N-terminal Ac2-26 region, demonstrating their ability to modulate inflammatory cytokine production, reduce neutrophil infiltration, promote neutrophil apoptosis and cellular proliferation, and stimulate IL-10 production.137,138 Targeted nanoparticles (NPs) offer a promising therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel disease, potentially achieving improved spatial localization, enhanced efficacy, and reduced off-target effects. Leveraging the exposure of type IV collagen at sites of inflammation, Leoni et al developed type IV collagen-targeted polymeric NPs encapsulating Ac2-26 for treating dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in a mouse model. Their results demonstrated that these NPs were superior to Ac2-26 alone in reducing colitis severity, and also improved anastomotic healing in a murine colitis model.139,140 Based on the Annexin A1 EphA2-binding domain, cell-penetrating peptides of 3 amino acids (SKG) and 11 amino acids (EYVQTVKSSKG) were developed. These peptides–A1 (28–30) and A1 (20–30), respectively–inhibited Annexin A1-EphA2 binding, promoted EphA2 degradation, and suppressed gastric and cervical cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo, suggesting potential therapeutic applications in these cancers.141

Annexin A5’s high affinity for PS has enabled its use in developing molecular probes and drug delivery systems. Coupled with flow cytometry, Annexin A5 serves as an effective in vitro probe for apoptosis detection, finding widespread application. Furthermore, ribozyme-labeled recombinant Annexin A5 has shown promise in in vivo assays using animal models.142,143 Building upon previous findings, researchers developed PS-containing liposomes encapsulating Avastin for topical ocular administration in rats and rabbits, with and without Annexin A5. Results demonstrated that Annexin A5 enhanced drug delivery across biological barriers via liposome association, a finding corroborated by in vitro studies showing enhanced drug delivery via Annexin A5-mediated endocytosis.144 Utilizing Annexin A5’s PS-targeting properties, an Annexin A5-conditionally cytotoxic drug fusion protein was designed for targeted delivery of a conditionally cytotoxic drug precursor (prodrug) to tumor cells. In vitro studies demonstrated significant cytotoxic activity against tumor vascular endothelial cells and tumor cells when this fusion protein was combined with 5-fluorocytosine.145 Thrombin-human Annexin A5 complexes, formed via Lys-Lys ligation, have shown efficacy in treating arteriovenous malformations by forming emboli in target vessels at low radiation doses.146 Huang et al147 engineered a chimeric protein comprising the extracellular domain of tissue factor and human Annexin A5. This chimera retains the ligand-binding activity of both tissue factor and human Annexin A5, accelerating factor X activation by factor VIIa. Interestingly, it displays a biphasic effect on coagulation: promoting coagulation at low concentrations and exhibiting anticoagulant activity at high concentrations. A recent clinical trial in healthy volunteers (NCT04217629) demonstrated that intravenous doses of Annexin A5 ranging from 0.75 to 20 mg were well-tolerated and showed no significant adverse effects. While further safety and tolerability data from animal models are needed, these findings support the pursuit of additional clinical translational studies.

Conclusions and Prospects

Recent advances in bioinformatics have increasingly highlighted the significant role of annexins in regulated cell death, although the precise mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Elucidating these mechanisms is crucial for advancing our fundamental knowledge of RCD in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis and for understanding its contributions to the pathogenesis and treatment of diverse diseases. RCD patterns significantly influence tissue repair, ultimately impacting long-term outcomes, such as organ senescence and tumorigenesis. Indeed, a vicious cycle of impaired anti-inflammatory barriers, dysregulated cell death, and subsequent inflammation underlies many chronic inflammatory and infectious diseases. Given the key role of annexins in modulating inflammation and the established link between inflammation and RCD, a deeper understanding of their anti-inflammatory mechanisms, holds significant potential for developing novel therapeutic targets and strategies. However, several key questions remain: In vivo studies using Annexin A knockout mouse models have revealed that individual Annexin A deficiencies do not always impair normal development—does this reflect functional redundancy with other proteins? What types of studies can be developed in future basic research? Will future drug discovery efforts focus on recombinant Annexin A-derived mimetic peptides or on traditional small-molecule inhibitors? Future research should focus on elucidating the precise molecular targets and comprehensive mechanisms of Annexin A action in cell death and inflammation, and on developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting Annexin A.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank everyone who helped with this work.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (82360132), Gansu Province Science and Technology Plan Funding (24JRRA911, 23JRRA1489, 24YFFA037), The Fund of the First Hospital of Lanzhou University (ldyyyn2018-62, ldyyyn2020-02, ldyyyn2020-14), Gansu Clinical Medical Research Center of Infection & Liver Diseases (21JR7RA392), Lanzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (2023-2-76).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Gerke V, Gavins FNE, Geisow M, et al. Annexins-a family of proteins with distinctive tastes for cell signaling and membrane dynamics. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1574. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-45954-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss SE, Morgan RO. The annexins. Genome Biol. 2004;5(4):219. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-4-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirsaeidi M, Gidfar S, Vu A, Schraufnagel D. Annexins family: insights into their functions and potential role in pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0843-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huber R, Römisch J, Paques EP. The crystal and molecular structure of human annexin V, an anticoagulant protein that binds to calcium and membranes. EMBO J. 1990;9(12):3867–3874. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07605.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caron D, Boutchueng-Djidjou M, Tanguay RM, Faure RL. Annexin A2 is SUMOylated on its N-terminal domain: regulation by insulin. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(9):985–991. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y-Z, Wang -Y-Y, Huang L, Zhao -Y-Y, Chen L-H, Zhang C. Annexin A protein family in atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2022;531:406–417. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2022.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Li X, Li X, Zheng L, Lei L. ANXA1 silencing increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to low-concentration arsenic trioxide treatment by inhibiting ERK MAPK activation. Tumori. 2015;101(4):360–367. doi: 10.5301/tj.5000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Wang H, Zheng M, Deng L, Zhang X, Lin B. p53 and ANXA4/NF‑κB p50 complexes regulate cell proliferation, apoptosis and tumor progression in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Med. 2020;46(6):2102–2114. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koese M, Rentero C, Kota BP, et al. Annexin A6 is a scaffold for PKCα to promote EGFR inactivation. Oncogene. 2013;32(23):2858–2872. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan J, Ofengeim D. A guide to cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(5):379–395. doi: 10.1038/s41580-023-00689-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian X, Yang W, Jiang W, Zhang Z, Liu J, Tu H. Multi-omics profiling identifies microglial annexin A2 as a key mediator of NF-κB pro-inflammatory signaling in ischemic reperfusion injury. Molecular Cellular Proteo. 2024;23(2):100723. doi: 10.1016/j.mcpro.2024.100723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou Z, Lu F, Lin J, et al. Loss of Annexin A1 in macrophages restrains efferocytosis and remodels immune microenvironment in pancreatic cancer by activating the cGAS/STING pathway. J Immuno Therap Cancer. 2024;12(9):e009318. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-009318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu L, Liu C, Chang D-Y, et al. The attenuation of diabetic nephropathy by Annexin A1 via regulation of lipid metabolism through the AMPK/PPARα/CPT1b pathway. Diabetes. 2021;70(10):2192–2203. doi: 10.2337/db21-0050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo M, Almeida D, Dallacasagrande V, et al. Annexin A2 promotes proliferative vitreoretinopathy in response to a macrophage inflammatory signal in mice. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):8757. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-52675-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minciacchi VR, Karantanou C, Bravo J, et al. Differential inflammatory conditioning of the bone marrow by acute myeloid leukemia and its impact on progression. Blood Adv. 2024;8(19):4983–4996. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2024012867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia Q, Mao M, Zeng Z, et al. Inhibition of SENP6 restrains cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating Annexin-A1 nuclear translocation-associated neuronal apoptosis. Theranostics. 2021;11(15):7450–7470. doi: 10.7150/thno.60277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren J, Hu Z, Niu G, et al. Annexin A1 induces oxaliplatin resistance of gastric cancer through autophagy by targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR. FASEB J. 2023;37(3):e22790. doi: 10.1096/fj.202200400RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanches JM, Branco LM, Duarte GHB, et al. Annexin A1 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation and modifies lipid release profile in isolated peritoneal macrophages. Cells. 2020;9(4):926. doi: 10.3390/cells9040926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruschi M, Petretto A, Vaglio A, Santucci L, Candiano G, Ghiggeri GM. Annexin A1 and autoimmunity: from basic science to clinical applications. Int J mol Sci. 2018;19(5):1348. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito S, Kuromiya K, Sekai M, et al. Accumulation of annexin A2 and S100A10 prevents apoptosis of apically delaminated, transformed epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120(43):e2307118120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2307118120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh M, Lim H, Jin H, et al. ANXA2 (annexin A2) is crucial to ATG7-mediated autophagy, leading to tumor aggressiveness in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Autophagy. 2024;20(3):659–674. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2024.2305063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng Y, Li W, Wang Z, et al. The p-STAT3/ANXA2 axis promotes caspase-1-mediated hepatocyte pyroptosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):497. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03692-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin J, Cao P, Ding X, Zeng Z, Deng L, Luo L. Machine learning identifies ferroptosis-related gene ANXA2 as potential diagnostic biomarkers for NAFLD. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1303426. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1303426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo C, Li N, Dong C, et al. 33-kDa ANXA3 isoform contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis via modulating ERK, PI3K/Akt-HIF and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. J Adv Res. 2021;30:85–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong M, Che N, Zhou L, et al. Efficacy of annexin A3 blockade in sensitizing hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib and regorafenib. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):826–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L, Cai Y, Deng C. Identification of ANXA3 as a biomarker associated with pyroptosis in ischemic stroke. EurJ Med Res. 2023;28(1):596. doi: 10.1186/s40001-023-01564-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu L, Li W, Liu D, et al. ANXA3-rich exosomes derived from tumor-associated macrophages regulate ferroptosis and lymphatic metastasis of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12(5):614–630. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-23-0595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y, Sui L, Qiu B, Yin X, Liu J, Zhang X. ANXA4 promotes trophoblast invasion via the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway in preeclampsia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2019;316(4):C481–c491. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00404.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park N, Chun Y-J. Auranofin promotes mitochondrial apoptosis by inducing annexin A5 expression and translocation in human prostate cancer cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2014;77(22–24):1467–1476. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2014.955834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su G, Zhang D, Li T, et al. Annexin A5 derived from matrix vesicles protects against osteoporotic bone loss via mineralization. Bone Res. 2023;11(1):60. doi: 10.1038/s41413-023-00290-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao Y, Zhang H, Wang J, et al. Annexin A5 ameliorates traumatic brain injury-induced neuroinflammation and neuronal ferroptosis by modulating the NF-ĸB/HMGB1 and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;114:109619. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Song H, Liu D, et al. S100A12 triggers NETosis to aggravate myocardial infarction injury via the Annexin A5-calcium axis. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):1746. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-56978-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee P, Chander V, Bandyopadhyay A. Balancing functions of annexin A6 maintain equilibrium between hypertrophy and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(9):e1873. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang M, Pan M, Li Y, et al. ANXA6/TRPV2 axis promotes lymphatic metastasis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by inducing autophagy. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2023;12(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s40164-023-00406-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li N, Chen L, Zhao X, Gu C, Chang Y, Feng S. Targeting ANXA7/LAMP5-mTOR axis attenuates spinal cord injury by inhibiting neuronal apoptosis via enhancing autophagy in mice. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):309. doi: 10.1038/s41420-023-01612-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu L, Gou R, Guo Q, Wang J, Liu Q, Lin B. High expression and potential synergy of human epididymis protein 4 and Annexin A8 promote progression and predict poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(7):4017–4030. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheng Y, Ding H, Zhou J, et al. The effect of TFAP2A/ANXA8 axis on ferroptosis of cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CESC) in vitro. Cytotechnology. 2024;76(4):403–414. doi: 10.1007/s10616-024-00619-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao H, Xia M, Ruan H. Knockdown of sulfotransferase 2B1 suppresses cell migration, invasion and promotes apoptosis in ovarian carcinoma cells via targeting annexin A9. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2024;50(8):1334–1344. doi: 10.1111/jog.15969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei T, Zhu X. Knockdown of ANXA10 inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by down-regulating TSG101 thereby inactivating the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2021;53(4):429–440. doi: 10.1007/s10863-021-09902-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Zhou Y, Ning L, Chen J, Chen H, Li X. Knockdown of ANXA10 induces ferroptosis by inhibiting autophagy-mediated TFRC degradation in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(9):588. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-06114-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z, Liu F, Lan X, Wang F, Sun J, Wei H. Pyroptosis-related genes features on prediction of the prognosis in liver cancer: an integrated analysis of bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing. Heliyon. 2024;10(19):e38438. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu S, Wang J, Guo C, Qi H, Sun MZ. Annexin A11 knockdown inhibits in vitro proliferation and enhances survival of Hca-F cell via Akt2/FoxO1 pathway and MMP-9 expression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;70:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong M, Park N, Chun Y-J. Role of annexin a5 on mitochondria-dependent apoptosis induced by tetramethoxystilbene in human breast cancer cells. Biomolecules Ther. 2014;22(6):519–524. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le T, Ferling I, Qiu L, et al. Redistribution of the glycocalyx exposes phagocytic determinants on apoptotic cells. Dev Cell. 2024;59(7):853–868.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2024.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berg Klenow M, Iversen C, Wendelboe Lund F, et al. Annexins A1 and A2 accumulate and are immobilized at cross-linked membrane-membrane interfaces. Biochemistry. 2021;60(16):1248–1259. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cordeiro MF, Hill D, Patel R, Corazza P, Maddison J, Younis S. Detecting retinal cell stress and apoptosis with DARC: progression from lab to clinic. Prog Retinal Eye Res. 2022;86:100976. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2021.100976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang R, Lu W, Wen X, et al. Annexin A5-conjugated polymeric micelles for dual SPECT and optical detection of apoptosis. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(6):958–964. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.083220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centonze M, Di Conza G, Lahn M, et al. Autotaxin inhibitor IOA-289 reduces gastrointestinal cancer progression in preclinical models. J Exper Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42(1):197. doi: 10.1186/s13046-023-02780-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasan M, Kumolosasi E, Jantan I, Jasamai M, Nazarudin N. Knockdown of Annexin A1 induces apoptosis, causing G2/M arrest and facilitating phagocytosis activity in human leukemia cell lines. Acta Pharm. 2022;72(1):109–122. doi: 10.2478/acph-2022-0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bai L, Guo Y, Du Y, et al. 47 kDa isoform of Annexin A7 affecting the apoptosis of mouse hepatocarcinoma cells line. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;83:1127–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye W, Li Y, Fan L, et al. Effect of annexin A7 suppression on the apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. mol Cell Biochem. 2017;429(1–2):33–43. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2934-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ning J, Wang X, Li N, et al. ZBM-H-induced activation of GRP78 ATPase promotes apoptosis via annexin A7 in A549 lung cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2022;123(4):798–806. doi: 10.1002/jcb.30224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu H, Guo D, Sha Y, et al. ANXA7 promotes the cell cycle, proliferation and cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance of multiple myeloma cells by up-regulating CDC5L. Aging. 2020;12(11):11100–11115. doi: 10.18632/aging.103326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Zhou X, Deng X, et al. miR-186-ANXA9 signaling inhibits tumorigenesis in breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1166666. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1166666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim JK, Kim PJ, Jung KH, et al. Decreased expression of annexin A10 in gastric cancer and its overexpression in tumor cell growth suppression. Oncol Rep. 2010;24(3):607–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(3):486–541. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu S, Yao S, Yang H, Liu S, Wang Y. Autophagy: regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(10):648. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-06154-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee S-J, Jung YH, Kim JS, et al. A vibrio vulnificus VvpM induces IL-1β production coupled with necrotic macrophage death via distinct spatial targeting by ANXA2. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:352. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghislat G, Aguado C, Knecht E. Annexin A5 stimulates autophagy and inhibits endocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(1):92–107. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Enrich C, Rentero C, Grewal T. Annexin A6 in the liver: from the endocytic compartment to cellular physiology. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017;1864(6):933–946. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gao W, Guo H, Niu M, et al. circPARD3 drives malignant progression and chemoresistance of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting autophagy through the PRKCI-Akt-mTOR pathway. mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01279-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun X, Shu Y, Xu M, et al. ANXA6 suppresses the tumorigenesis of cervical cancer through autophagy induction. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(6):e208. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H, Huang S, Wang S, et al. Targeting annexin A7 by a small molecule suppressed the activity of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C in vascular endothelial cells and inhibited atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E−/− mice. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4(9):e806. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao J, Sun Y, Yang H, et al. PLGA-microspheres-carried circGMCL1 protects against Crohn’s colitis through alleviating NLRP3 inflammasome-induced pyroptosis by promoting autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(9):782. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05226-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xi Y, Ju R, Wang Y. Roles of Annexin A protein family in autophagy regulation and therapy. Biomed Pharmacothe. 2020;130:110591. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li L, Xing T, Chen Y, et al. In vitro CRISPR screening uncovers CRTC3 as a regulator of IFN-γ-induced ferroptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Discovery. 2023;9(1):331. doi: 10.1038/s41420-023-01630-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao R, Kalathur RKR, Coto‐Llerena M, et al. YAP/TAZ and ATF4 drive resistance to Sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma by preventing ferroptosis. EMBO Mol Med. 2021;13(12):e14351. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202114351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D. Broadening horizons: the role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(5):280–296. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-00462-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang S, Zhang Y. HMGB1 in inflammation and cancer. J Hematol oncol. 2020;13(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00950-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen X, He W-T, Hu L, et al. Pyroptosis is driven by non-selective gasdermin-D pore and its morphology is different from MLKL channel-mediated necroptosis. Cell Res 2016;26(9):1007–1020. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hsu S-K, Li C-Y, Lin I-L, et al. Inflammation-related pyroptosis, a novel programmed cell death pathway, and its crosstalk with immune therapy in cancer treatment. Theranostics. 2021;11(18):8813–8835. doi: 10.7150/thno.62521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526(7575):660–665. doi: 10.1038/nature15514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dennis EA, Norris PC. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(8):511–523. doi: 10.1038/nri3859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee S-J, Jung YH, Song EJ, Jang KK, Choi SH, Han HJ. Vibrio vulnificus VvpE stimulates IL-1β production by the hypomethylation of the IL-1β promoter and NF-κB activation via lipid raft–dependent ANXA2 recruitment and reactive oxygen species signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2015;195(5):2282–2293. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rezaei Tavirani M, Rezaei Tavirani M, Zamanian Azodi M. ANXA2, PRKCE, and OXT are critical differentially genes in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2019;12(2):131–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu C, Yalavarthi S, Tambralli A, et al. Inhibition of neutrophil extracellular trap formation alleviates vascular dysfunction in type 1 diabetic mice. Sci Adv. 2023;9(43):eadj1019. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adj1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang D, Liu J. Neutrophil extracellular traps: a new player in cancer metastasis and therapeutic target. J Exper Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):233. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-02013-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sugimoto MA, Vago JP, Teixeira MM, Sousa LP. Annexin A1 and the resolution of inflammation: modulation of neutrophil recruitment, apoptosis, and clearance. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:8239258. doi: 10.1155/2016/8239258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Qi M, Huang H, Li Z, et al. Qingxin Jieyu Granule alleviates myocardial infarction through inhibiting neutrophil extracellular traps via activating ANXA1/FPR2 axis. Phytomedicine. 2024;135:156147. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.156147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garnier Y, Claude L, Hermand P, et al. Plasma microparticles of intubated COVID-19 patients cause endothelial cell death, neutrophil adhesion and netosis, in a phosphatidylserine-dependent manner. Br J Haematol. 2022;196(5):1159–1169. doi: 10.1111/bjh.18019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gül E, Enz U, Maurer L, et al. Intraluminal neutrophils limit epithelium damage by reducing pathogen assault on intestinal epithelial cells during Salmonella gut infection. PLoS Pathogens. 2023;19(6):e1011235. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Karki R, Sharma BR, Tuladhar S, et al. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ triggers inflammatory cell death, tissue damage, and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection and cytokine shock syndromes. Cell. 2021;184(1):149–168.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang D, Liang Y, Zhao S, et al. ZBP1 mediates interferon-induced necroptosis. Cell mol Immunol. 2020;17(4):356–368. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0237-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Matsuzawa-Ishimoto Y, Hwang S, Cadwell K. Autophagy and inflammation. Ann Rev Immunol. 2018;36(1):73–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ferlazzo V, D’Agostino P, Milano S, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of annexin-1: stimulation of IL-10 release and inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2003;3(10–11):1363–1369. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(03)00133-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Drechsler M, de Jong R, Rossaint J, et al. Annexin A1 counteracts chemokine-induced arterial myeloid cell recruitment. Circ Res. 2015;116(5):827–835. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.116.305825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Butcher MJ, Galkina EV. wRAPping up early monocyte and neutrophil recruitment in atherogenesis via AnnexinA1/FPR2 signaling. Circ Res. 2015;116(5):774–777. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.115.305920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27(1):229–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Man SM, Kanneganti TD. Converging roles of caspases in inflammasome activation, cell death and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(1):7–21. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Galvão I, de Carvalho RVH, Vago JP, et al. The role of annexin A1 in the modulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunology. 2020;160(1):78–89. doi: 10.1111/imm.13184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Broering MF, Tocci S, Sout NT, et al. Development of an inflamed high throughput stem-cell-based gut epithelium model to assess the impact of Annexin A1. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024;20(5):1299–1310. doi: 10.1007/s12015-024-10708-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kamaly N, Fredman G, Subramanian M, et al. Development and in vivo efficacy of targeted polymeric inflammation-resolving nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(16):6506–6511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303377110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fredman G, Kamaly N, Spolitu S, et al. Targeted nanoparticles containing the proresolving peptide Ac2-26 protect against advanced atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(275):275ra220. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Swisher JFA, Khatri U, Feldman GM. Annexin A2 is a soluble mediator of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(5):1174–1184. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Song C, Zhou X, Dong Q, et al. Regulation of inflammatory response in human chondrocytes by lentiviral mediated RNA interference against S100A10. Inflamm Res. 2012;61(11):1219–1227. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0519-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Derry MC, Sutherland MR, Restall CM, Waisman DM, Pryzdial ELG. Annexin 2-mediated enhancement of cytomegalovirus infection opposes inhibition by annexin 1 or annexin 5. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(1):19–27. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82294-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Marlin R, Pappalardo A, Kaminski H, et al. Sensing of cell stress by human γδ TCR-dependent recognition of annexin A2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(12):3163–3168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621052114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kaminski H, Marsères G, Cosentino A, et al. Understanding human γδ T cell biology toward a better management of cytomegalovirus infection. Immunol Rev. 2020;298(1):264–288. doi: 10.1111/imr.12922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fang YT, Lin CF, Liao PC, et al. Annexin A2 on lung epithelial cell surface is recognized by severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus spike domain 2 antibodies. Mol Immunol. 2010;47(5):1000–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Swisher JF, Burton N, Bacot SM, Vogel SN, Feldman GM. Annexin A2 tetramer activates human and murine macrophages through TLR4. Blood. 2010;115(3):549–558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-226944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang S, Yu M, Guo Q, et al. Annexin A2 binds to endosomes and negatively regulates TLR4-triggered inflammatory responses via the TRAM-TRIF pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):15859. doi: 10.1038/srep15859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ewing MM, de Vries MR, Nordzell M, et al. Annexin A5 therapy attenuates vascular inflammation and remodeling and improves endothelial function in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(1):95–101. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.110.216747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jia Z, Kang B, Dong Y, Fan M, Li W, Zhang W. Annexin A5 derived from cell-free fat extract attenuates osteoarthritis via macrophage regulation. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(8):2994–3007. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.92802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Zhou R. Loss of Annexin A5 expression attenuates the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response of rat alveolar macrophages. Cell Biol Int. 2020;44(2):391–401. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wu L, Liu C, Chang D-Y, et al. Annexin A1 alleviates kidney injury by promoting the resolution of inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2021;100(1):107–121. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cui J, Morgan D, Cheng DH, et al. RNA-sequencing-based transcriptomic analysis reveals a role for Annexin-A1 in classical and influenza a virus-induced autophagy. Cells. 2020;9(6):1399. doi: 10.3390/cells9061399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dallacasagrande V, Hajjar KA. Annexin A2 in inflammation and host defense. Cells. 2020;9(6):1499. doi: 10.3390/cells9061499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]