Abstract

Introduction and objective

Despite recent advances in the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the clinical outcome of some patients is still unsatisfactory. Therefore, early evaluation to identify high-risk individuals in STEMI patients is essential. The hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score, as a new indicator that can reflect both nutritional status and inflammatory state of the body, can provide prognostic information. In this context, the present study was designed to investigate the relationship between HALP scores assessed at admission and no-reflow as well as long-term outcomes in patients with STEMI.

Material and methods

A total of 1040 consecutive STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI were enrolled in this retrospective study. According to the best cutoff value of HALP score of 40.11, the study samples were divided into two groups. The long-term prognosis was followed up by telephone.

Results

Long-term mortality was significantly higher in patients with HALP scores lower than 40.11 than in those higher than 40.11. The optimal cutoff value of HALP score for predicting no-reflow was 41.38, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.727. The best cutoff value of HALP score for predicting major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) was 40.11, the AUC was 0.763. The incidence of MACE and all-cause mortality was higher in the HALP score <40.11 group.

Conclusion

HALP score can independently predict the development of no-reflow and long-term mortality in STEMI patients undergoing PCI.

Keywords: HALP score, long-term mortality, no-reflow phenomenon, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Introduction

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), a critical form of cardiovascular disease, is the leading cause of death in industrialized countries, and its mortality and morbidity are increasing rapidly in some low-income and middle-income countries [1]. For STEMI, timely percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to restore coronary blood supply is the key to improve the prognosis of patients [2]. PCI is the first choice of treatment strategy for STEMI patients; it can quickly open the acute obstructive coronary artery and rescue ischemic cardiomyocytes. It can significantly reduce the risk of death in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and improve the prognosis [3]. However, despite recent advances in the management of STEMI, the clinical outcome of some patients is still unsatisfactory, and the mortality rate is high even after timely primary PCI. Therefore, early evaluation to identify high-risk individuals in STEMI patients is essential. We expected to find a measure that predicted the occurrence of no-reflow and stratified the long-term outcome of patients with STEMI.

No-reflow phenomenon is a serious complication that occurs in approximately 10–30% of patients with AMI during successful primary PCI and has few effective treatment options [4]. The no-reflow phenomenon expands the degree of myocardial ischemic necrosis, which increases the risk of adverse cardiovascular events such as malignant arrhythmia, in-hospital death, cardiogenic shock, and heart failure [5–7]. Thus, the no-reflow phenomenon reduces the advantage of primary PCI and increases the likelihood of poor short-term and long-term outcomes [8]. Current studies suggest that no-reflow is related to ischemic injury, thromboembolism, distal atherosclerosis, reperfusion injury, and oxidative stress [9]. Despite intensive research on treatments targeting the various known mechanisms associated with no-reflow, no effective treatment has been shown to be sufficient to effectively prevent or reverse no-reflow. Therefore, effective prevention or reduction of no-reflow has become the focus of improving the prognosis of STEMI patients.

Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score, calculated from four basic blood indicators including albumin, hemoglobin, platelet count, and lymphocyte count, can reflect nutritional status and systemic inflammation. With the characteristics of simple availability and low cost, HALP score has been proved to predict the prognosis of various cancer types [10–12]. The HALP score is calculated as follows: HALP score = Lymphocyte count (109/l) × Albumin (g/l) × Hemoglobin (g/l)/Platelet count (109/l) [11]. Related studies have shown that anemia and hypoalbuminemia indicate the presence of malnutrition, which have been confirmed as risk factors for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and are associated with poor prognosis of patients [13]. Lymphocytes have an important regulatory function in post-ACS inflammation [14]. Excessive platelet activation increases the risk of thromboembolism and can exacerbate the inflammatory response [15].

However, no studies have evaluated the value of HALP score in predicting no-reflow as well as long-term adverse outcomes in STEMI patients treated with PCI. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate these relationships.

Methods

Study population

This is a retrospective, single-center cohort study. This study included 1595 patients diagnosed with STEMI who underwent PCI within 12 h from January 2017 to January 2021 in Hebei General Hospital. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hebei General Hospital. Because this was a retrospective study, patient informed consent was waived. The study was conducted in strict accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. STEMI was defined as: (1) ECG indicates ST-segment elevation in two or more adjacent leads and new left bundle branch block or abnormal Q wave; (2) symptoms of chest pain >30 min in the 24 h prior to admission; (3) At least one of the serum myocardial markers creatine kinase-myocardial band isoenzymes and cardiac troponin T were positive within 24 hours of the onset of chest pain symptoms [16].

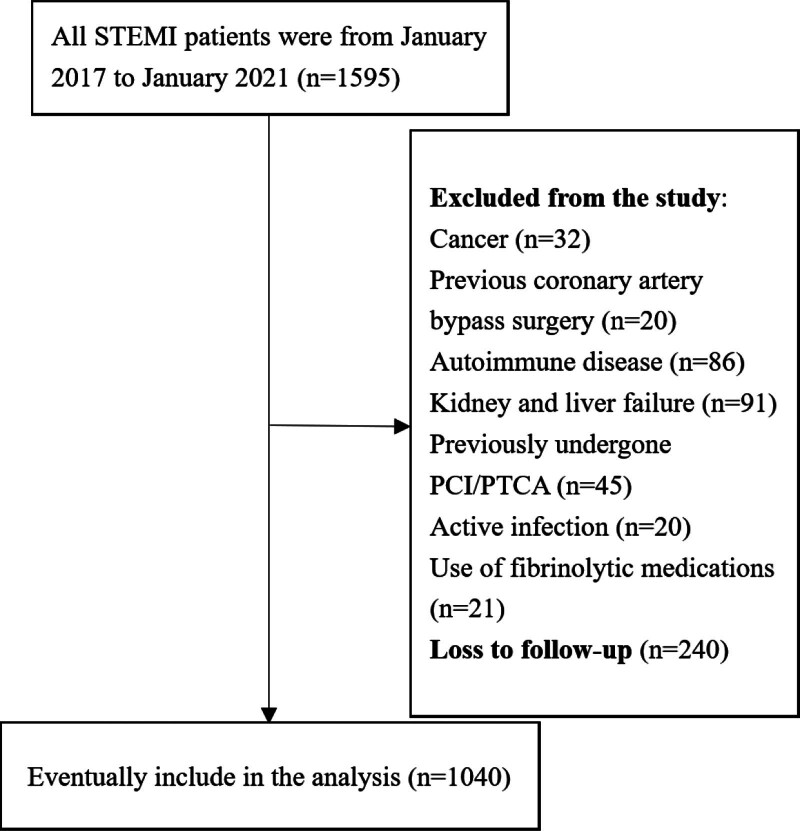

The following patients were excluded to avoid factors that could affect HALP score: (1) cancer (n = 32), (2) previous coronary artery bypass surgery (n = 20), (3) autoimmune disease (n = 86), (4) kidney or liver failure (n = 91), (5) previously undergone PCI/percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (n = 45), (6) active infection (n = 20), and (7) use of fibrinolytic medications (n = 21). Loss to follow-up was n = 240. Finally, 1040 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study.

Coronary procedures

All enrolled patients were immediately given a single dose of clopidogrel 300 mg or ticagrelor 180 mg and aspirin 300 mg after being diagnosed as STEMI. Before coronary intervention, patients were given 100 μg/kg unfractionated heparin intravenously. The Judkins technique was used for coronary angiography. Radial artery access was used in most patients. Three interventional cardiologists who were unaware of the clinical data of the patients evaluated the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade at the final angiography. No-reflow phenomenon is defined as TIMI blood flow grade remaining ≤grade 2 following revascularization of the culprit lesion in the absence of vascular dissection, coronary spasm, and thromboembolism [17].

Laboratory measurements

Before coronary intervention, blood samples were collected from patients from an anterior cubital vein. Laboratory examination items include white neutrophil count, blood cell count, lymphocyte count, platelet count, monocyte count, blood glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, serum creatine, glomerular filtration rate, and other biochemical tests.

The HALP score is calculated as follows: HALP score = Lymphocyte count (109/l) × Albumin (g/l) × Hemoglobin (g/l)/Platelet count (109/l) [11]. The medication during hospitalization followed the relevant clinical guidelines [2]. The cardiologist determines angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, statins, beta-blockers, and other drugs. Diabetes, smoking, and medical records of taking related drugs are based on self-report. Experienced doctors used Simpson’s method to measure left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by transthoracic echocardiography.

Definition of major adverse cardiovascular events and follow-up

All enrolled patients were followed up telephonically at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after discharge, and the endpoint events during this period were recorded. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) including repeated revascularization procedures following PCI (recurrent myocardial infarction or stent thrombosis), worsening heart failure (previous heart failure acute episodes or new-onset heart failure), and cardiovascular death were the primary endpoints.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 26.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test is used to determine the normality of a numerical variable. Numerical variables that conform to a normal distribution are described as mean ± SD. Numerical variables that are not normally distributed are described in terms of median and interquartile intervals. t-Test or Mann–Whitney U test was applied for comparison of two groups of numerical variables. Frequency and percentage are used to describe categorical variables, and χ2 tests or Fisher exact probabilities are applied for inter-group comparisons.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to analyze the predictive power and the optimal cutoff value of the HALP score for no-reflow phenomenon and long-term MACE. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve method and the log-rank test were employed to compare survival rates between the two groups, respectively.

The independent risk variables of no-reflow phenomenon during primary PCI were analyzed using logistic regression, and the influence of HALP score on patient prognosis was determined using the Cox proportional hazards model. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

A total of 1040 STEMI patients were included in the final analysis. Figure 1 is the flowchart of this study. The clinical baseline characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1. The study sample consisted of 1040 STEMI patients treated with PCI. The mean age of the patients was 62.2 ± 10.2 years, including 812 males (78.1%). Intraoperative no-reflow occurred in 144 patients (14.3%). During a mean follow-up of 16 months, MACE occurred in 156 patients (15%). According to the best cutoff value of HALP score of 40.11, the samples were divided into two groups. There were no significant differences in BMI, family history, diabetes, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, white blood cell count, monocyte count, culprit vessels, LVEF, and postoperative medication between patients with a HALP score <40.11 and patients with HALP score ≥40.11. Age, female, monocyte count, neutrophil count, platelet count, and no-reflow were significantly higher in patients with HALP score <40.11 than those with HALP score ≥40.11. Lymphocyte count, hemoglobin, and albumin levels were lower in HALP score <40.11 group than HALP score ≥40.11 group.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of this study. The figure shows the selection and exclusion criteria and follow-up of the study subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| Variable | All | HALP score <40.11 (n = 458) | HALP score ≥40.11 (n = 582) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and medical history | ||||

| Age, years | 62 (55–68) | 63 (56–68) | 60 (55–68) | 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.48 (23.63–27.68) | 25.4 (23.6–27.68) | 25.56 (23.58–27.68) | 0.743 |

| Male, n (%) | 812 (78.08) | 344 (75.1) | 468 (80.4) | 0.040 |

| Family history of coronary heart disease, n (%) | 143 (13.75) | 65 (14.2) | 78 (13.4) | 0.713 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 245 (23.56) | 118 (25.8) | 127 (21.8) | 0.137 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 610 (58.65) | 265 (57.9) | 345 (59.3) | 0.645 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 551 (52.98) | 241 (52.6) | 310 (53.3) | 0.836 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 130 (12.5) | 57 (12.4) | 73 (12.5) | 0.962 |

| Hemodynamic characteristics | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | 132 (114–149) | 131 (114–148) | 132 (115–149) | 0.710 |

| DBP, mmHg | 82 (72–92) | 82 (72–92.5) | 81.5 (72–92) | 0.931 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 74 (64–88) | 74 (63–88) | 75 (65–89) | 0.962 |

| LVEF | 54 (47–58) | 53 (47–57) | 54 (46–59) | 0.137 |

| Killip class ≥2 at admission, n (%) | 191 (18.4) | 80 (17.5) | 111 (19.1) | 0.567 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| White blood cell count, ×109/l | 10.29 (8.71–12.08) | 10.41 (9–12.19) | 10.18 (8.59–11.97) | 0.824 |

| Monocyte count, ×109/l | 0.42 (0.32–0.54) | 0.43 (0.33–0.54) | 0.41 (0.31–0.54) | 0.932 |

| Neutrophil count, ×109/l | 7.94 (6.16–9.73) | 8.26 (6.78–9.92) | 7.52 (5.84–9.51) | 0.006 |

| Lymphocyte count, ×109/l | 1.73 (1.4–2.08) | 1.45 (1.22–1.70) | 1.98 (1.70–2.28) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count, ×109/l | 233 (199–276) | 261 (224–293) | 217.5 (184–252) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 133 (124–144) | 130 (121–140) | 136 (126–148) | <0.001 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 44 (37–49) | 40 (37–47) | 45 (39–49) | <0.001 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mmol/l | 6.17 (5.11–8.47) | 6.19 (5.15–9.22) | 6.09 (5.06–8.08) | 0.279 |

| Peak cTnT, ng/ml | 3.32 (2.3–5.65) | 3.43 (2.32–5.89) | 3.23 (2.12–5.64) | 0.557 |

| Peak CK-MB, U/l | 109.5 (49–226.05) | 112 (49–230) | 108.35 (49–212.3) | 0.686 |

| Peak NT-pro BNP, pg/ml | 610 (233–1512) | 634 (232–1921) | 566.5 (233–1354) | 0.125 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 4.53 (3.9–5.25) | 4.56 (3.88–5.26) | 4.53 (3.92–5.25) | 0.351 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 1.51 (1.05–2.05) | 1.49 (1.03–1.31) | 1.52 (1.06–2.09) | 0.567 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dl | 1.02 (0.89–1.15) | 1 (0.88–1.15) | 1.03 (0.90–1.16) | 0.256 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dl | 2.99 (2.55–3.58) | 2.97 (2.50–3.49) | 3 (2.59–3.48) | 0.790 |

| Serum creatine, mg/dl | 77 (67.6–87.52) | 77 (67.6–87.06) | 76.9 (67.08–88) | 0.416 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 89.74 (75.89–99.36) | 89.73 (74.48–98.99) | 90.02 (77.40–99.91) | 0.135 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 330.36 (272.2–398.9) | 328.7 (274.66–396.57) | 330.73 (267.5–399.57) | 0.858 |

| HALP score | 41.73 (32.28–54.05) | 31.24 (25.69–36.06) | 52.37 (45.18–64.06) | <0.001 |

| Procedural data | ||||

| Culprit vessel | ||||

| Left circumflex artery, n (%) | 96 (9.23) | 43 (9.4) | 53 (9.1) | 0.876 |

| Left anterior descending artery, n (%) | 510 (49.05) | 225 (49.1) | 285 (48.9) | 0.960 |

| Left main coronary artery, n (%) | 62 (5.96) | 29 (6.3) | 33 (5.7) | 0.655 |

| Right coronary artery, n (%) | 372 (35.76) | 161 (35.2) | 211 (36.3) | 0.713 |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 413 (39.71) | 174 (38) | 239 (41.1) | 0.315 |

| Single culprit lesion, n (%) | 627 (60.29) | 284 (62) | 343 (58.9) | 0.315 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 304 (29.3) | 130 (28.4) | 174 (29.9) | 0.594 |

| Initial TIMI flow grade, n (%) | 0.559 | |||

| 0–1 | 740 (71.15) | 318 (69.4) | 422 (72.5) | |

| ≥2 | 300 (28.85) | 140 (30.6) | 160 (27.5) | |

| Angiographic no-reflow | 144 (13.85) | 112 (24.5) | 32 (5.5) | <0.001 |

| Number of stent, n | 1.18 ± 0.53 | 1.19 ± 0.51 | 1.17 ± 0.55 | 0.523 |

| Door-to-balloon time, min | 60 (47–79) | 60 (47–79) | 60 (47–78) | 0.523 |

| Postoperative medication | ||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 985 (94.7) | 435 (95) | 550 (94.5) | 0.733 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 993 (95.5) | 433 (94.5) | 560 (96.2) | 0.196 |

| Statin, n (%) | 938 (90.2) | 412 (90) | 526 (90.4) | 0.820 |

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 835 (80.29) | 376 (82.1) | 459 (78.9) | 0.194 |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 257 (24.7) | 121 (26.4) | 136 (23.4) | 0.257 |

| ACEI or ARB, n (%) | 541 (52) | 230 (50.2) | 311 (53.4) | 0.302 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CK-MB, creatine kinase myocardial band; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; HALP score, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet score; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Univariate logistic analysis showed that lymphocyte count, platelet count, HALP score, and albumin could predict no-reflow. According to the results of multivariate logistic regression, HALP score in Table 2 (odds ratio = 0.932, 95% CI: 0.903–0.961, P < 0.001) was still an independent predictor.

Table 2.

Results of the univariate and multivariate regression analyses for the predictors of the no-reflow phenomenon

| Variable | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocyte count | 0.531 (0.374–0.754) | <0.001 | 2.474 (0.958–6.393) | 0.061 |

| Platelet count | 1.005 (1.003–1.008) | <0.001 | 0.998 (0.993–1.003) | 0.474 |

| HALP score | 0.945 (0.931–0.959) | <0.001 | 0.919 (0.877–0.962) | <0.001 |

| Albumin | 0.930 (0.903–0.957) | <0.001 | 1.008 (0.991–1.025) | 0.366 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.990 (0.979–1.000) | 0.057 | – | – |

| Age | 0.995 (0.978–1.012) | 0.573 | – | – |

| Male | 1.118 (0.738–1.696) | 0.598 | – | – |

| LVEF | 0.996 (0.976–1.016) | 0.711 | – | – |

| Peak cTnT | 1.005 (0.951–1.063) | 0.852 | – | – |

| Culprit vessel | 1.088 (0.921–1.284) | 0.321 | – | – |

CI, confidence interval; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; HALP score, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet score; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OR, odds ratio.

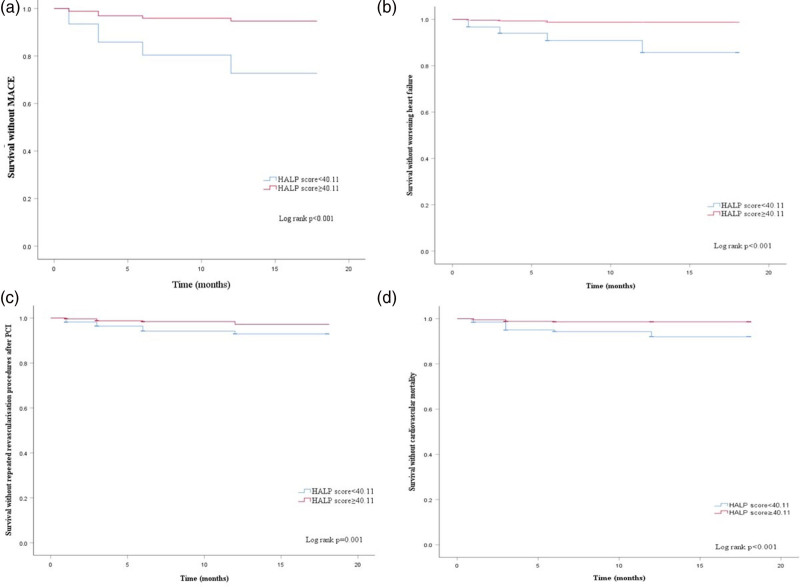

Table 3 shows the occurrence of adverse clinical outcomes at 18 months of patient follow-up. MACE occurred in 125 patients with HALP score <40.11, including 34 cases of cardiovascular mortality, 61 cases of worsening heart failure, and 30 cases of repeated revascularization procedures after PCI. MACE occurred in 31 patients in HALP score ≥40.11 group, including 8 cases of cardiovascular mortality, 7 cases of worsening heart failure, and 16 cases of repeated revascularization procedures after PCI.

Table 3.

18 months follow-up outcomes

| Variable | HALP score <40.11 (n = 458) | HALP score ≥40.11 (n = 582) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | 36 (7.9) | 17 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Repeated revascularisation procedures after PCI | 30 (6.6) | 16 (2.7) | 0.003 |

| Worsening heart failure | 61 (13.3) | 7 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 34 (7.4) | 8 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| MACE | 125 (27.3) | 31 (5.3) | <0.001 |

HALP score, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet score; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

There were significant differences between the two groups in MACE, worsening heart failure, repeated revascularization procedures after PCI, and cardiovascular mortality. The results of Kaplan–Meier curve showed that compared with HALP score ≥40.11 group, the risks of MACE, worsening heart failure, repeated revascularization procedures after PCI, and cardiovascular mortality in the HALP score <40.11 group were significantly higher than those in the HALP score ≥40.11 group (P < 0.001, Fig. 2). Table 4 shows that HALP score is an independent risk factor for MACE (P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

The Kaplan–Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of (a) MACE, (b) worsening heart failure, (c) repeated revascularization procedures after PCI, and (d) cardiovascular mortality. MACE, major adverse cardiac events; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression of long-term MACE

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Lymphocyte count | 0.215 (0.141–0.328) | <0.001 | 2.486 (0.649–9.523) | 0.184 |

| Platelet count | 1.004 (1.001–1.006) | 0.004 | 0.992 (0.984–1.001) | 0.068 |

| HALP score | 0.931 (0.916–0.946) | <0.001 | 0.884 (0.829–0.943) | <0.001 |

| Albumin | 0.969 (0.943–0.995) | 0.022 | 1.059 (0.999–1.122) | 0.052 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.986 (0.976–0.996) | 0.008 | 1.014 (0.995–1.034) | 0.156 |

| Age | 1.007 (0.990–1.024) | 0.405 | – | – |

| Male | 1.109 (0.738–1.667) | 0.618 | – | – |

| LVEF | 0.989 (0.970–1.009) | 0.269 | – | – |

| Peak cTnT | 0.987 (0.933–1.045) | 0.658 | – | – |

| Culprit vessel | 0.934 (0.793–1.100) | 0.413 | – | – |

CI, confidence interval; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; HALP score, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet score; HR, hazard ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE, major adverse cardiac events.

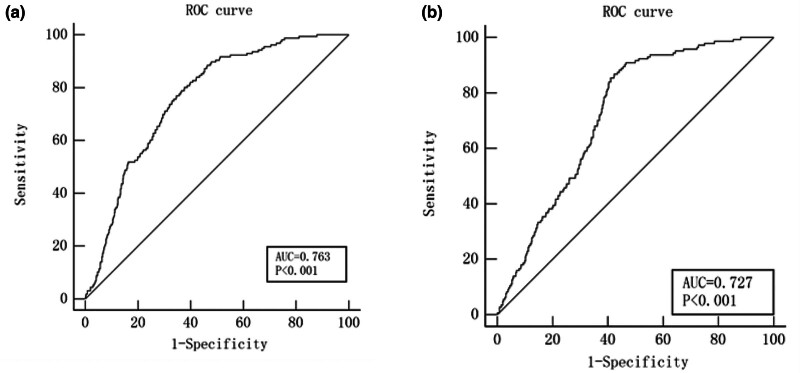

In addition, we found that HALP score could predict long-term MACE (Z = 14.47, 95% CI: 0.736–0.788, P < 0.001), the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.763, the best cutoff value was 40.11, the sensitivity was 80.13%, and the specificity was 62.33% (Fig. 3a). Figure 3b shows the predictive value of HALP score for no-reflow phenomenon (Z = 12.18, 95% CI: 0.699–0.754, P < 0.001), the AUC was 0.727, the best cutoff value was 41.38, the sensitivity was 86.81%, and the specificity was 57.7%.

Fig. 3.

The ROC curve was used to evaluate the HALP score for predicting (a) long-term MACE and (b) no-reflow phenomenon. HALP score, the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet score; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that HALP scores were independently associated with a higher likelihood of no-reflow phenomenon in STEMI patients undergoing PCI. The results of ROC curve showed that HALP score had a strong predictive ability for no-reflow phenomenon and long-term prognosis in these patients.

No-reflow phenomenon is associated with increased short-term adverse cardiovascular events and long-term mortality in patients with STEMI, so it is of great significance for the risk classification of patients with STEMI [18,19]. A total of 144 patients (14.3%) had no-reflow phenomenon, which was consistent with the results of previous studies [20,21]. The pathophysiological mechanism of no-reflow phenomenon is not fully understood, but it is currently believed to be related to microvascular perfusion disorder and some mechanisms that may cause microvascular dysfunction such as increased inflammatory process, microvascular occlusion, ischemia-reperfusion injury, preexisting endothelial dysfunction, and oxidant–antioxidant imbalance [22,23]. Therefore, early identification of high-risk patients with no-reflow and optimization of intervention strategies, preoperative preparation, and close monitoring are essential to reduce the risk of no-reflow and its potential harms. In previous studies, a variety of scoring methods and biomarkers have been developed to assess no-reflow in STEMI patients undergoing PCI [24–27]. However, these scoring methods and markers still have some limitations in clinical practice. Therefore, there is a need for a simple and accessible risk score for early identification of high-risk patients with no-reflow.

HALP score is a novel index calculated from hemoglobin and albumin levels and lymphocyte and platelet counts [28]. Decreased albumin and hemoglobin levels indicate anemia and malnutrition, whereas increased platelet counts and decreased lymphocyte counts are associated with impaired immune system and inflammation, and thus can reflect both systemic inflammatory and nutritional status of patients [29]. As a new predictor, HALP score has been proved to have good predictive efficacy for the poor prognosis of patients with malignant tumors [30,31]. Previous studies have shown that HALP scores are associated with short-term and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure and with short-term poor outcomes in patients with STEMI [32,33].

The results of this study show that HALP score is associated with no-reflow in STEMI patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI), HALP score serves as an independent risk factor for no-reflow, and is associated with long-term MACE, which may be related to the aggravation of inflammation and oxidative stress. The decrease in hemoglobin suggests anemia and may affect the oxygen supply to the myocardium [34]. The occurrence of no-reflow is closely related to systemic inflammation and oxidative stress [35]. Because albumin has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, low albumin levels are associated with no-reflow [36,37].

As a new index, HALP score has the characteristics of simple availability, low cost, and easy to be applied in clinical practice. HALP score can be used for early identification of high-risk patients with no-reflow and long-term MACE. For high-risk patients with low HALP score, anticoagulation, antiplatelet, and lipid-lowering therapy should be intensified before operation, blood pressure should be strictly controlled, the dosage of contrast agent and surgical procedures should be minimized during operation to reduce the occurrence of no-reflow during operation, and early individualized intensive treatment and close follow-up after operation should be carried out. Thus changing the long-term prognosis of these patients. However, whether the HALP score can be applied in clinical practice still needs further large-scale, multicenter prospective studies to clarify the efficacy of HALP score in predicting the morbidity and mortality of STEMI patients treated with PCI.

This study is the first to demonstrate the predictive value of HALP score for long-term MACE in STEMI patients treated with pPCI; however, this study has limitations. First, it was a single-center retrospective study. Second, the HALP score was not compared with the classical risk scoring system, and the relationship between the HALP score and the synergy between PCI with taxus and cardiac surgery (SYNTAX) score was not evaluated.

In conclusion, HALP score has a good predictive value for intraoperative no-reflow phenomenon and long-term MACE in patients with STEMI. It is of great significance for early identification of high-risk STEMI patients, early individualized intensive treatment, and close follow-up, so as to change the long-term prognosis.

Acknowledgements

All authors contributed to: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and, (3) final approval of the version to be published.

This study involves human participants and was approved by an Ethics Committee or Institutional Board.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Li X, Yu C, Lei L, Liu X, Chen Y, Wang Y, et al. Association of pre-PCI blood pressure and no-reflow in patients with acute ST-elevation coronary infarction. Glob Heart 2024; 19:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018; 39:119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Zhang F, Liu L, Gao M, Song X, Li Y, et al. Prognostic value of GRACE risk score combined with systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Angiology 2023. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandrashekhar Y, Alexander T, Mullasari A, Kumbhani DJ, Alam S, Alexanderson E, et al. Resource and infrastructure-appropriate management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in low- and middle-income countries. Circulation 2020; 141:2004–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tasar O, Karabay AK, Oduncu V, Kirma C. Predictors and outcomes of no-reflow phenomenon in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis 2019; 30:270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Waha S, Patel MR, Granger CB, Ohman EM, Maehara A, Eitel I, et al. Relationship between microvascular obstruction and adverse events following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: an individual patient data pooled analysis from seven randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2017; 38:3502–3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnic FS, Wainstein M, Lee MK, Behrendt D, Wainstein RV, Ohno-Machado L, et al. No-reflow is an independent predictor of death and myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J 2003; 145:42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pantea-Roșan LR, Pantea VA, Bungau S, Tit DM, Behl T, Vesa CM, et al. No-reflow after PPCI—a predictor of short-term outcomes in STEMI patients. J Clin Med 2020; 9:2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annibali G, Scrocca I, Aranzulla TC, Meliga E, Maiellaro F, Musumeci G. ‘No-reflow’ phenomenon: a contemporary review. J Clin Med 2022; 11:2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo Y, Shi D, Zhang J, Mao S, Wang L, Zhang W, et al. The hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score is a novel significant prognostic factor for patients with metastatic prostate cancer undergoing cytoreductive radical prostatectomy. J Cancer 2019; 10:81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antar R, Farag C, Xu V, Drouaud A, Gordon O, Whalen MJ. Evaluating the baseline hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score in the United States adult population and comorbidities: an analysis of the NHANES. Front Nutr 2023; 10:1206958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan H, Lin S. Association of hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet score with risk of cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in the general population: results from the NHANES 1999–2018. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023; 14:1173399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartopo AB, Gharini PP, Setianto BY. Low serum albumin levels and in-hospital adverse outcomes in acute coronary syndrome. Int Heart J 2010; 51:221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Liu Z, Shao J, Lin L, Jiang M, Wang L, et al. Immune and inflammation in acute coronary syndrome: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J Immunol Res 2020; 2020:4904217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reininger AJ, Bernlochner I, Penz SM, Ravanat C, Smethurst P, Farndale RW, et al. A 2-step mechanism of arterial thrombus formation induced by human atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55:1147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 127:e362–e425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niccoli G, Burzotta F, Galiuto L, Crea F. Myocardial no-reflow in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toprak K, Kaplangoray M, Akyol S, İnanir M, Memioğlu T, Taşcanov MB, et al. The non-HDL-C/HDL-C ratio is a strong and independent predictor of the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol 2024; 79:194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler MJ, Chan W, Taylor AJ, Dart AM, Duffy SJ. Management of the no-reflow phenomenon. Pharmacol Ther 2011; 132:72–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fajar JK, Heriansyah T, Rohman MS. The predictors of no reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Indian Heart J 2018; 70:S406–S418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciofani JL, Allahwala UK, Scarsini R, Ekmejian A, Banning AP, Bhindi R, De Maria GL. No-reflow phenomenon in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: still the Achilles’ heel of the interventionalist. Future Cardiol 2021; 17:383–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y, Yang J, Ji Y, Wang S, Wang T, Wang F, Tang J. Usefulness of fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio to predict no-reflow and short-term prognosis in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Vessels 2019; 34:1600–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaur G, Baghdasaryan P, Natarajan B, Sethi P, Mukherjee A, Varadarajan P, Pai RG. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of coronary no-reflow phenomenon. Int J Angiol 2021; 30:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai C, Liu M, Zhou Y, Lu D, Li C, Chang S, et al. A score system to predict no-reflow in primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the PIANO score. Eur J Clin Invest 2022; 52:e13686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yarlioglues M, Karacali K, Ilhan BC, Yalcinkaya Oner D. A retrospective study: association of C-reactive protein and uric acid to albumin ratio with the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2024; 397:131621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplangoray M, Toprak K, Cicek OF, Deveci E. Relationship between the fibrinogen/albumin ratio and microvascular perfusion in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevated myocardial infarction: a prospective study. Arq Bras Cardiol 2023; 120:e20230002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saygi M, Tanalp AC, Tezen O, Pay L, Dogan R, Uzman O, et al. The prognostic importance of the Naples prognostic score for in-hospital mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis 2024; 35:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ustaoglu M, Aktas G, Kucukdemirci O, Goren I, Bas B. Could a reduced hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score predict autoimmune hepatitis and degree of liver fibrosis? Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2024; 70:e20230905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karakayali M, Omar T, Artac I, Ilis D, Arslan A, Altunova M, et al. The prognostic value of HALP score in predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis 2023; 34:483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu H, Zheng X, Ai J, Yang L. Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score and cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13,110 patients. Int Immunopharmacol 2023; 114:109496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong Y, Yong Y, Wang Y. Clinical value of hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet indexes in predicting lymph node metastasis and recurrence of endometrial cancer: a retrospective study. PeerJ 2023; 11:e16043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L, Gong B, Wang W, Xu K, Wang K, Song G. Association between haemoglobin, albumin, lymphocytes, and platelets and mortality in patients with heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2024; 11:1051–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toprak K, Toprak IH, Acar O, Ermiş MF. The predictive value of the HALP score for no-reflow phenomenon and short-term mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Postgrad Med 2024; 136:169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akbar KMA, Dharma S, Andriantoro H, Sukmawan R, Mangkuanom AS, Rejeki VG. Relationship between hemoglobin concentration at admission with the incidence of no-reflow phenomenon and in-hospital mortality in acute myocardial infarction with elevation of ST segments in patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Angiol 2022; 32:106–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allencherril J, Jneid H, Atar D, Alam M, Levine G, Kloner RA, Birnbaum Y. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of the no-reflow phenomenon. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2019; 33:589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roche M, Rondeau P, Singh NR, Tarnus E, Bourdon E. The antioxidant properties of serum albumin. FEBS Lett 2008; 582:1783–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheinenzon A, Shehadeh M, Michelis R, Shaoul E, Ronen O. Serum albumin levels and inflammation. Int J Biol Macromol 2021; 184:857–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]