Abstract

Cholesterol and its metabolic derivatives have important biological functions and are crucial in tumor initiation, progression, and treatment. Cholesterol maintains the physical properties of cellular membranes and is pivotal in cell signal transduction. Cholesterol metabolism includes both de novo synthesis and uptake from extracellular sources such as low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). This review explores both aspects to provide a comprehensive understanding of their roles in cancer. Cholesterol metabolism is involved in bile acid production and steroid hormone biosynthesis and is closely linked to the reprogramming of endogenous and exogenous cellular signals within the tumor microenvironment. These signals are intricately associated with key biological processes such as tumor cell proliferation, survival, invasion, and metastasis. Evidence suggests that regulating cholesterol metabolism may offer therapeutic benefits by inhibiting tumor growth, remodeling the immune microenvironment, and enhancing antitumor immune responses. This review summarizes the role of cholesterol metabolism in tumor biology and discusses the application of statins and other cholesterol metabolism inhibitors in cancer therapy, aiming to provide novel insights for the development of antitumor drugs targeting cholesterol metabolism and for advances in cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Cholesterol metabolism, Tumorigenesis, Therapy, Clinical application

Background

Research has revealed a close association between cholesterol metabolism and tumorigenesis. Cholesterol, a sterol compound widely present in vertebrates, is an essential component of cellular membranes and plays multiple biological roles [1]. In mammalian cell membranes, cholesterol is a key lipid component that maintains membrane integrity and fluidity and contributes to the formation of membrane microstructures. In addition to its structural and functional roles in membranes, cholesterol can be converted into various oxysterols through enzymatic and nonenzymatic pathways, which are critical for the biosynthesis of steroid hormones [2]. The homeostasis of cholesterol metabolism is maintained by a complex regulatory network involving processes such as cholesterol biosynthesis, uptake, efflux, and storage [3]. Cholesterol interacts with numerous proteins, including receptors, ion channels, and enzymes, and plays a significant role in regulating protein stability, subcellular localization, and biological activity [4, 5]. Studies have shown that cholesterol metabolism undergoes reprogramming during tumor initiation and progression. This metabolic reprogramming directly impacts the biological properties of tumor cells and modulates the immune cells' antitumor activity within the tumor microenvironment. Cholesterol metabolism is significantly upregulated in tumor cells and is closely associated with rapid tumor growth and malignant phenotypes [6–8]. Cholesterol and its derivatives, as well as intermediates in its synthesis, regulate tumor cell proliferation, migration, stemness, and drug resistance [9–13]. Given the pivotal role of cholesterol metabolism in tumor biology, targeting cholesterol metabolism has emerged as a prominent focus in cancer research, with significant progress achieved in recent years. This review explores the regulatory mechanisms of cholesterol metabolism in tumor cells and discusses the potential applications of targeting cholesterol metabolic pathways in cancer therapy.

Overview of cholesterol metabolism reprogramming

Cholesterol is the primary sterol compound in mammals and plays a crucial role in fundamental cellular life processes. It plays a major role in the composition of the cellular membrane and serves as a precursor for the biosynthesis of bile acids and various steroid hormones, including aldosterone, progesterone, cortisol, estrogen, and testosterone [14]. Cholesterol was first isolated and described in 1784 by a French chemist from the ethanol-soluble fraction of human gallstones. Its metabolic derivatives also play significant roles in cellular signaling [15]. Knockout studies show that inhibition of cholesterol synthesis is lethal. However, in cancer cells, de novo cholesterol synthesis can be completely inhibited which shifts the cell to be dependent upon cholesterol uptake. Cells acquire cholesterol through two primary pathways: de novo synthesis via the mevalonate pathway and uptake of exogenous cholesterol. In the mevalonate pathway, two molecules of acetyl-CoA undergo a series of reactions to produce mevalonate, with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR) serving as the rate-limiting enzyme. Mevalonate is further converted through enzymatic reactions into farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) and squalene, ultimately forming cholesterol. The second major pathway involves dietary cholesterol, which is absorbed and transported in the bloodstream as LDL. LDL binds to low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLRs) on cell membranes and is internalized via endocytosis. Intracellular cholesterol levels are dynamically regulated. Excess cholesterol can be esterified and stored in lipid droplets or exported from cells via cholesterol efflux. Lipid rafts, in contrast, serve as dynamic membrane microdomains that regulate signaling rather than storage. Cholesterol efflux primarily depends on adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, such as ABCA1, ABCG1, ABCG5, and ABCG8, often in cooperation with HDL [16]. The scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1) is a membrane receptor protein that plays a crucial role in HDL metabolism by selectively mediating the uptake of HDL-derived cholesteryl esters into cells and tissues. In addition to promoting cholesterol efflux from peripheral tissues, such as macrophages, back to the liver, SR-B1 helps regulate plasma membrane cholesterol levels. This receptor also facilitates the uptake of lipid-soluble vitamins and assists viral entry into host cells. SR-B1’s diverse functions influence various physiological processes, including programmed cell death, female fertility, platelet function, vascular inflammation, and conditions such as diet-induced atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Furthermore, SR-B1 has emerged as a potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. The selective uptake pathway of HDL-cholesteryl esters mediated by SR-B1 is being explored for the delivery of therapeutic and diagnostic agents [17]. Additionally, cholesterol can be esterified into less toxic cholesterol esters (CEs) by acyl-coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase (ACATs) and stored in lipid droplets or rafts. Cholesterol synthesis, uptake, efflux, and esterification are regulated by various transcription factors, including sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2 (SREBP-2), liver X receptors (LXRs), and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1 (NRF1). SREBP-2 specifically regulates cholesterol synthesis and transport by controlling the expression of enzymes required for lipid homeostasis. It is also worth noting that, SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) interacts with insulin induced gene 1 (INSIG1) to regulate SREBP2 activation, which controls cholesterol synthesis. Under high cholesterol conditions, INSIG1 retains SCAP-SREBP2 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), preventing its activation [18]. LXRs maintain the intracellular cholesterol balance by regulating the expression of cholesterol efflux-related genes, such as ABCA1 and ABCG1, and by modulating the SREBP pathway to influence cholesterol synthesis. NRF1 promotes cholesterol efflux by alleviating suppression of the LXR pathway. Other transcription factors or coregulators, such as apolipoprotein A-1 binding protein (AIBP), regulate cholesterol efflux by activating SREBP-2 [19]. In addition, the deletion of liver-specific asialoglycoprotein receptor 1 (ASGR1) stabilizes LXRα, upregulates ABCA1 and ABCG5/G8, facilitates cholesterol transport to HDL, and enhances its excretion into bile and feces, thereby reducing serum and hepatic lipid levels [20]. Nuclear receptor corepressors, such as silencing mediators for retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptors, interact with transcription factors to regulate ABCA1 and SREBP-1 expression, further balancing cholesterol levels [21]. Moreover, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase b (PI3K/AKT) signaling pathway maintains intracellular lipid levels and ensures cell growth by regulating the expression of SREBP-1 and its target genes [22]. Cholesterol metabolism is a dynamic and multilayered process. Under pathological conditions such as cancer, this balance can be reprogrammed to meet the specific demands of cancer cells—a phenomenon referred to as cholesterol metabolism reprogramming.

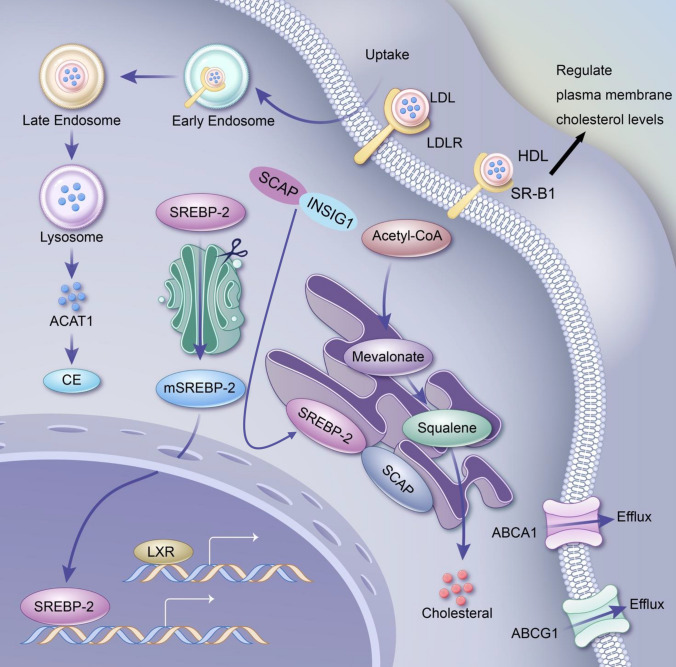

The specific mechanisms of cholesterol metabolic reprogramming are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the remodeling mechanisms of cholesterol metabolism. Cholesterol metabolic reprogramming refers to the process by which cells, particularly cancer cells, adaptively regulate cholesterol synthesis, uptake, storage, and utilization to meet the demands of rapid growth and survival. Tumor cells enhance de novo cholesterol synthesis through upregulated HMGCR activity and increase cholesterol uptake by overexpressing LDLR. SR-B1 selectively mediates the uptake of HDL-derived cholesteryl esters into cells and tissues, helping to regulate plasma membrane cholesterol levels. Excess cholesterol is stored as cholesteryl esters in lipid droplets via ACAT enzymes, providing a reservoir for metabolic needs. Simultaneously, cholesterol efflux is suppressed by downregulating transporters such as ABCA1 and ABCG1, leading to intracellular cholesterol accumulation that supports membrane structure, lipid raft formation, and oncogenic signaling pathways like PI3K/AKT. Cholesterol derivatives, including oxysterols and steroid hormones, further influence the tumor microenvironment by modulating immune suppression and promoting cell growth. This reprogramming is tightly controlled by factors such as SREBP2 and LXRs and can also be influenced by non-coding RNAs and inflammatory signals. In addition, SCAP interacts with INSIG1 to regulate the activation of SREBP2 to control cholesterol synthesis. Understanding cholesterol metabolic reprogramming sheds light on its role in cancer progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance, offering potential targets for novel cancer treatments, such as HMGCR inhibitors, LDLR blockers, and cholesterol efflux modulators

Cholesterol metabolism and the malignant biological behaviors of tumor cells

Role of cholesterol in cell proliferation

Cholesterol is a key raw material for cell membrane synthesis, and the mevalonate pathway is responsible for producing sterols and other isoprenoid metabolites essential for various biological functions [23]. Cholesterol, the primary sterol in mammals and a precursor for nonsteroidal isoprenoids, is required in large quantities by rapidly dividing cells. Many signaling pathways converge on the mevalonate pathway, including those involved in proliferation, tumor promotion, and tumor suppression [24, 25]. Cholesterol and other mevalonate derivatives are critical for cell cycle progression, and their deficiency can block different cell cycle stages. Additionally, the accumulation of nonisoprenoid mevalonate derivatives may lead to DNA replication stress. Understanding the mechanisms by which cholesterol and other mevalonate derivatives influence cell cycle progression may facilitate the identification of novel inhibitors or the repurposing of existing cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitors to target cancer cell division [24]. Tumor cells require substantial cholesterol to support their rapid proliferation. Upregulation of cholesterol metabolic pathways is a hallmark of many cancers, particularly those with high proliferation rates. Key enzymes, such as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A (HMG-CoA) reductase, are overexpressed in tumor cells, promoting cholesterol synthesis [26]. Notably, in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), which is characterized by the presence of numerous lipid droplets containing free and esterified cholesterol, the expression of cholesterol biosynthetic enzyme genes is suppressed. This suggests a reliance on exogenous cholesterol in ccRCC [27]. This finding collectively indicate that de novo cholesterol synthesis may be inhibited in certain cancers. Under such circumstances, cancer cells must rely on lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol uptake.

Recent studies have shown that the reprogramming of cholesterol metabolism, glucose metabolism, and lipid metabolism is associated with cancer cell proliferation. For example, alterations in cholesterol levels (induced by high-cholesterol or high-fat diets) increased the incidence of chemically induced colonic polyps and tumor progression in mice. At the cellular level, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were found to promote colorectal cancer cell (CRC) proliferation by regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. Supplementation with LDL-C or HDL-C increased glucose uptake and utilization, leading to increased lactate production by CRC cells. Moreover, LDL-C and HDL-C upregulated aerobic glycolysis, resulting in increased ATP production via glycolysis and decreased ATP generation via oxidative phosphorylation. Cholesterol uptake-related molecular alterations and increased lipid and cholesterol accumulation were observed in cells treated with LDL-C or HDL-C [28]. In another study [29], an analysis of cytochrome p450 family 27 subfamily a member 1 (CYP27A1) expression data from public databases and metastatic RCC cases revealed significant downregulation of CYP27A1 in RCC tissues. This downregulation was associated with favorable clinicopathological features and prognosis. In vitro experiments demonstrated that the upregulation or downregulation of CYP27A1 expression in RCC cell lines significantly influenced their apoptosis, proliferation, invasion, migration, and clonogenic capacity. This study is the first to explore the role of CYP27A1 in RCC, providing new potential strategies for RCC treatment and highlighting the predictive value of CYP27A1 in metastatic RCC targeted therapy.

Furthermore, studies have shown that inhibiting cholesterol biosynthesis can reduce cancer cell proliferation. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), a cancer with high cholesterol demand, requires substantial cholesterol for its rapid growth. However, the precise mechanisms by which the cholesterol metabolism balance is disrupted in PDAC remain unclear. Research by Duan et al. [30] investigated the mechanisms of cholesterol metabolic imbalance in PDAC. Bioinformatics analysis and in vivo and in vitro experiments revealed that arfGAP with FG repeats 1 (AGFG1) expression was associated with poor prognosis in patients with PDAC. RNA sequencing revealed that AGFG1 overexpression increased intracellular cholesterol biosynthesis, whereas AGFG1 knockdown inhibited cholesterol biosynthesis and led to cholesterol accumulation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mechanistically, AGFG1 was shown to interact with Caveolin 1 (CAV1) to relocate sterols, promoting cholesterol biosynthesis and disrupting the intracellular cholesterol metabolic balance. Yao et al. [31] reported that kruppel-like factor 13 (KLF13) expression was downregulated in CRC cells. KLF13 inhibited CRC cell proliferation by transcriptionally repressing 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1 (HMGCS1) and cholesterol biosynthesis. Cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitors significantly suppressed colony formation. He et al. [32] reported that squalene epoxidase (SQLE) was highly upregulated in CRC patients. SQLE-associated cholesterol biosynthesis regulation was significantly elevated and correlated with poor prognosis. These findings demonstrated that SQLE promoted CRC progression by promoting the accumulation of calcitriol and activating mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling via CYP24A1-mediated cholesterol metabolism, suggesting that SQLE is a potential therapeutic target for CRC.

Notably, studies [33] have explored the pivotal role of the glycolysis‒cholesterol metabolism axis in regulating the tumor microenvironment (TME), its dual-edged effects on immune cell responses and immunotherapy efficacy, emphasizing how combined interventions targeting glycolysis/cholesterol metabolism and immunotherapy could unleash the potential of antitumor immune responses and advance personalized treatment strategies. Chen et al. [34] used gene set variation analysis on data from 430 CRC cases to identify four metabolic subtypes based on glycolysis- and cholesterol synthesis-related gene sets: quiescent, glycolytic, cholesterol synthesis, and mixed types. These subtypes differ in immune scores, stromal scores, and estimation of stromal and immune cells in malignant tumor tissues using expression data (ESTIMATE) algorithm-derived scores and are associated with the cancer-immunity cycle, immune modulators, and responses to immunotherapy. Patients with cholesterol synthesis subtypes had better prognoses than those with other subtypes, particularly the glycolytic subtype. The glycolytic subtype correlated with unfavorable clinical features, including high mutation rates in titin (TTN), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and tumor protein p53 (TP53), and increased angiogenesis. The study also identified γ-glutamyl hydrolase (GGH) as an upregulated factor in CRC that is associated with CD4+ T-cell infiltration and longer overall survival. The overexpression of GGH in CRC-derived cell lines suppressed the expression of pyruvate kinase m1/2 (PKM), glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1), and lactate dehydrogenase a (LDHA), reduced extracellular lactate levels, and decreased intracellular ATP production.

Metabolic pathways have become fundamental in the deregulation of carcinogenesis, offering novel therapeutic strategies for cancer treatment. Recent research has uncovered a previously unrecognized branch of cholesterol metabolism involving the biochemical transformation of 5,6-epoxycholesterols. In breast cancer, 5,6-epoxycholesterols are metabolized into the tumor-promoting compound oncosterone, whereas in normal breast tissue, they give rise to the tumor-suppressing metabolite dendrogenin A (DDA). Targeting oncosterone to inhibit its mitogenic and invasive properties presents a promising avenue for breast cancer therapy. Meanwhile, reactivating DDA biosynthesis or utilizing DDA as a therapeutic agent offers potential strategies, including DDA-deficiency complementation, induction of breast cancer cell re-differentiation, and breast cancer chemoprevention [35].

Cholesterol in cell cycle regulation

Cholesterol constitutes an essential component of cellular membranes and plays a crucial role in cell cycle regulation. Cholesterol metabolites, such as sterols, regulate the expression and function of cell cycle-related proteins, thereby influencing cell proliferation [36]. High cholesterol levels promote cell transition from the G1 phase to the S phase, accelerating cell cycle progression [37].

Peng et al. [38] investigated the effects of the ACAT1 inhibitor avasimibe on the cell cycle of bladder cancer (BLCA) cells. Compared with normal cells, BLCA cells contain higher cholesterol levels, with ACAT1 playing a critical role in cholesterol esterification. Avasimibe, a drug used for treating atherosclerosis, effectively inhibits ACAT1. The study revealed that ACAT1 was significantly upregulated in BLCA and was positively correlated with tumor grade. Avasimibe treatment reduced BLCA cell proliferation and migration, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and upregulated the expression of ROS-related proteins such as superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and catalase. BLCA cells treated with avasimibe were arrested at the G1 phase, accompanied by downregulation of cell cycle-related proteins. Furthermore, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) was upregulated at both the transcriptional and protein levels following avasimibe treatment. The PPARγ antagonist GW9662 reversed avasimibe-induced cell cycle effects. Additionally, xenograft and lung metastasis models demonstrated that avasimibe effectively inhibited tumor growth and metastasis in vivo. This study provides the first evidence that avasimibe suppresses BLCA progression and metastasis, with the PPARγ signaling pathway playing a pivotal role in regulating the cell cycle distribution induced by avasimibe. Studies have shown that ApoE may play a crucial role in tumor initiation and progression. It has been reported that the interaction between ApoE and its receptors is involved in various cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, adhesion, and tissue-specific immune regulation [39]. However, compared to other receptors, ApoE preferentially binds to LRP8, activating distinct signaling pathways that induce cytoskeletal remodeling, cell adhesion, proliferation, and apoptosis [40]. Du et al. [41] demonstrated that apolipoprotein E2 (ApoE2)-low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8 (LRP8) regulates the cell cycle, with high expression levels of ApoE2-LRP8/c-Myc detected in tumor tissues and cell lines. ApoE2-LRP8 induces extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK) 1/2 phosphorylation to activate c-Myc, promoting the expression of cell cycle-related proteins. ApoE2 conditions facilitated c-Myc binding to the target gene sequence of the p21 Waf1/Cip1 promoter, reducing transcription. ERK/c-Myc signaling enhances the expression of cyclin D1, cdc2, and cyclin B1 while reducing p21 activity, thus promoting cell cycle progression. This study elucidates the role of ApoE2-LRP8 in activating the ERK-c-Myc-p21 Waf1/Cip1 signaling cascade and regulating the G1/S and G2/M transitions, highlighting its importance in cancer cell proliferation. ApoE2 may serve as a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer.

Cholesterol metabolism in tumor invasion and migration

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases, are key regulators of tumor cell invasion and metastasis [42]. Research [43] has highlighted the effects of high cholesterol levels on breast cancer cells, including increased macrophage infiltration and induction of the M2 phenotype, angiogenesis, endothelial cell proliferation, and cancer-associated fibroblast phenotypes. Cholesterol metabolism affects the invasive and metastatic potential of tumor cells and the cellular composition and functionality of the TME, facilitating angiogenesis. Cholesterol promotes epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast cancer cells by activating the estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRα) pathway and inducing excessive MMP9 release, driving extracellular matrix remodeling and enabling cancer cell invasion and migration. Conversely, studies [44] have shown that cholesterol efflux-regulating genes, such as LXRs LXRα and LXRβ, inhibit basal and cytokine-mediated MMP-9 expression. Treatment of mouse peritoneal macrophages with synthetic LXR agonists (GW3965 or T1317) reduced MMP9 mRNA expression and mitigated the stimulation of MMP9 by inflammatory factors (e.g., lipopolysaccharide, interleukin-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α). Clinically, hypercholesterolemia and dyslipidemia are associated with increased cancer risk and poor prognosis. Recently, it has been shown that cells can tolerate lipid-dependent stress by engaging phospholipid glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)-dependent antioxidant pathways and/or downregulating the expression of the enzymes responsible for lipid oxidation. Researchers [45] reported that metabolic stress caused by lipid accumulation is linked to ferroptosis suppressors GPX4, emphasizing the role of ferroptosis in tumor growth and metastasis. Dyslipidemia or hypercholesterolemia might influence carcinogenesis by selecting cells resistant to ferroptosis.

Cholesterol metabolism and tumor immune evasion

Tumor cells evade immune attacks through various mechanisms, with cholesterol metabolism playing a key role in this process. The mevalonate pathway, a highly conserved metabolic pathway that produces isoprenoids and cholesterol, is often hyperactive in cancer cells [46]. A recent study revealed that tumor cells utilize high intracellular cholesterol to induce T-cell exhaustion and facilitate immune evasion. This study [47] demonstrated that high cholesterol secreted by tumor cells (e.g., MC38 CRC cells and melanoma cells) in the TME increased cytoplasmic cholesterol levels in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Elevated cholesterol in CD8 + T cells triggered ER stress and upregulated ER stress-related protein x-box binding protein 1 (XBP1). As a transcription factor, XBP1 promotes the transcription of immune checkpoint molecules, leading to functional exhaustion and immunosuppressive states in CD8+ T cells, thereby advancing tumor progression. Early studies have indicated that cholesterol-lowering drugs can inhibit the high expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), which facilitates immune evasion by cancer cells [48]. Recent research has revealed that cholesterol can recognize and bind to two cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid consensus (CRAC) motifs within the transmembrane domain of PD-L1, forming a “sandwich” structure. This interaction enhances the stability of PD-L1, preventing its degradation and potentially contributing to the ability of tumor cells to evade immune surveillance [49]. Oxysterols in the TME exhibit immunosuppressive effects. For example, 22-hydroxycholesterol (22-OH-Chol) recruits C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2)-expressing neutrophils, inhibiting CD8+ T-cell activation and releasing pro-metastatic and pro-angiogenic factors [50]. Similarly, 27-OH-Chol recruits polymorphonuclear cells, promoting breast cancer invasion [51]. Additionally, 22-OH-Chol reduces dendritic cell (DC) and CD8+ T-cell recruitment by activating the LXRα-dependent transcriptional program in DCs, fostering a highly immunotolerant TME [52].

A summary of cholesterol metabolism and its association with tumor malignancy is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cholesterol metabolism and the malignant biological behaviors of tumor cells

| Role of cholesterol in tumors | Mechanisms | Cancer types | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor cell proliferation | LDL-C and HDL-C promote CRC cell proliferation by regulating cellular glucose and lipid metabolism | CRC | [28] |

| KLF13 is downregulated in colorectal cancer cells and inhibits CRC cell proliferation by transcriptionally repressing HMGCS1 and cholesterol biosynthesis | [31] | ||

| SQLE promotes CRC development through calcitriol accumulation and activation of the MAPK signaling pathway mediated by cholesterol-metabolizing enzyme CYP24A1 | [32] | ||

| Depriving ccRCC cells of either cholesterol or HDL compromises proliferation and survival in vitro and tumor growth in vivo; in contrast, elevated dietary cholesterol promotes tumor growth. SCARB1 is uniquely required for cholesterol import, and inhibiting SCARB1 is sufficient to cause ccRCC cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, elevated intracellular reactive oxygen species levels, and decreased PI3K/AKT signaling | RCC | [27] | |

| Altered expression of cholesterol homeostasis-related protein CYP27A1 in RCC cell lines significantly affects apoptosis, proliferation, invasion, migration, and colony formation | [29] | ||

| Knockdown of cholesterol metabolism-related gene AGFG1 inhibits cholesterol biosynthesis and leads to cholesterol accumulation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Furthermore, AGFG1 interacts with CAV1 to relocalize cholesterol, facilitating cholesterol biosynthesis and disrupting intracellular cholesterol metabolism homeostasis | PDAC | [30] | |

| The 5,6-epoxycholesterols are metabolized in breast cancers to the tumour promoter oncosterone whereas, in normal breast tissue, they are metabolized to the tumour suppressor metabolite, DDA. Blocking the mitogenic and invasive potential of oncosterone will present new opportunities for breast cancer treatment | Breast cancer | [35] | |

| Regulation of Tumor Cell Cycle | ACAT1 inhibitors can induce cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase in BLCA cells, accompanied by downregulation of cell cycle-related proteins (cyclin a1/2 (CCNA1/2), cyclin d1 (CCND1), and cyclin-dependent kinase 2/4 (CDK2/4) | BLCA | [38] |

| ApoE2-LRP8 induces ERK1/2 phosphorylation to activate c-Myc and promotes the expression of cell cycle-related proteins, regulating the G1/S and G2/M transitions | PDAC | [41] | |

| Tumor cell invasion and migration | Cholesterol promotes EMT in breast cancer cells and the release of MMP9 through the activation of the ERRα pathway, affecting extracellular matrix remodeling and providing the driving force for cancer cell invasion and migration | Breast cancer | [43] |

| Lipid accumulation induces metabolic stress in cells, requiring continuous expression of GPX4, a negative regulator of ferroptosis. Resistance to ferroptosis is a characteristic of metastatic cells, and the knockdown of GPX4 weakens tumor cell initiation and metastatic activity | Breast cancer, melanoma | [45] | |

| Tumor cell immune escape | Secretion of high cholesterol triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress in CD8+ T cells and upregulates the expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related protein XBP1. This promotes the transcription of immune checkpoint molecules such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), CD244, T-cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain-3 (TIM-3), and lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) within CD8+ T cells, leading to their functional exhaustion and immune suppression, thereby facilitating tumor progression | CRC, melanoma | [47] |

| PD-L1 depends on two cholesterol recognition motifs (CRAC1 and CRAC2) within its transmembrane domain to recognize and interact with cholesterol. The F257 and F259 binding sites within the CRAC1 motif interact with cholesterol via hydrophobic forces, while the R260 and R262 binding sites within the CRAC2 motif interact with cholesterol through hydrogen bonds. In this manner, PD-L1 is enveloped by cholesterol in a “sandwich” structure, which enhances its stability on the cell membrane | CRC | [49] | |

| 22-OH-Chol recruits CXCR2-expressing neutrophils, which can inhibit the activation and initiation of CD8+ T lymphocytes and release pro-metastatic and pro-angiogenic factors | – | [50] | |

| 27-OH-Chol facilitates breast cancer invasion by recruiting polymorphonuclear cells | Breast cancer | [51] | |

| 22-OH-Chol activates an LXRα-dependent transcriptional program in DC, reducing the recruitment of DCs and anti-tumor CD8+ T lymphocytes, creating a strong tumor-tolerant tumor microenvironment | – | [52] |

Cholesterol metabolism and tumor drug resistance

In recent years, an increasing amount of research has shown that cholesterol metabolism is closely associated with tumor drug resistance. To address the issue of tamoxifen (TAM) resistance in breast cancer treatment, Tiwary et al. [53] discovered that a small-molecule bioactive lipid, RRR-α-tocopherol ether-linked acetic acid analog (α-TEA), in combination with TAM, can inhibit survival signals by disrupting cholesterol-rich lipid microdomains and activate apoptotic pathways by inducing ER stress to overcome tamoxifen resistance. Palma et al. [54] reported that microRNAs (miRNAs) related to cholesterol and cancer resistance pathways participate in cholesterol-mediated TAM resistance. They reported that miRNA-128 and miRNA-223 play key roles in cholesterol-mediated TAM resistance and that altering the expression of these two miRNAs, in combination with TAM treatment, reduces free cholesterol and lipid rafts, thereby decreasing the viability of resistant cells. Other studies [55] have shown that cholesterol and mevalonic acid promote breast cancer progression, invasion, and resistance through the ERRα pathway.

The ERRα pathway also influences drug resistance in lung cancer. Clinically, epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) have shown significant benefits for the survival of patients with advanced lung cancer harboring EGFR mutations. However, resistance is an inevitable issue. Research by Pan et al. [56] demonstrated that cholesterol/EGFR/Src/ERK/specificity protein 1 (SP1) axis-induced ERRα re-expression promoted the survival of gefitinib- and osimertinib-resistant cancer cells. Furthermore, studies have shown that lowering cholesterol and reducing ERRα can be effective adjuncts for treating NSCLC. Similarly, Liu et al. [57] reported that the cholesterol metabolism inhibitor pitavastatin can inhibit lung cancer cell proliferation, promote apoptosis, and suppress acquired EGFR-TKI resistance. Pitavastatin, in combination with gefitinib, increased the sensitivity of lung cancer cells to EGFR-TKI drugs and alleviated resistance. In 2018, the FDA approved gilteritinib, a drug for treating FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia, although its therapeutic efficacy and mechanism for other malignancies are still unclear. Sun et al. [58] reported that gilteritinib inhibits FLT3-negative lung cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. Surprisingly, researchers reported that gilteritinib upregulated cholesterol biosynthesis genes and inhibited cholesterol efflux, leading to cholesterol accumulation in lung cancer cells. This cholesterol accumulation not only weakened the antitumor effect of gilteritinib but also induced resistance to the drug. To overcome this, researchers have used SQLE inhibitors (NB-598) to block cholesterol synthesis, increasing the sensitivity of lung cancer cells and gilteritinib-resistant lung cancer cells to gilteritinib. Furthermore, they discovered that the natural cholesterol inhibitor 25-OH-Chol could inhibit cholesterol biosynthesis and increase cholesterol efflux, suggesting that combining gilteritinib and cholesterol-lowering drugs may be a new therapeutic strategy for lung cancer. Natural products have also been shown to play a role in reversing lung cancer resistance. Dai et al. [59] reported that the natural anticancer agent Taxus chinensis var. mairei (Lemée et Lévl) Cheng et L.K. Fu (AETC) enhances osimertinib sensitivity through ERK/SREBP-2/HMGCR-mediated cholesterol biosynthesis, providing a promising therapeutic target for reversing osimertinib resistance.

Chemotherapy resistance is a major challenge in the treatment of gastrointestinal tumors. In cisplatin-resistant esophageal cancer cells, the cholesterol content is significantly increased, counteracting the proapoptotic effects of chemotherapy drugs on cancer cells [60]. In CRC, cholesterol synthesis plays an important role. Liu et al. [61] reported that SQLE has a new role in CRC chemotherapy resistance and revealed a novel mechanism of (S)−2,3-epoxydiene-dependent NF-κB activation, indicating the potential of combining terbinafine with 5-Fu for the treatment of CRC. Compared with colorectal cancer cells, CRC stem cells (CSCs) exhibit greater proliferation and invasiveness. One study [62] revealed that combining cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitors with conventional chemotherapy synergistically inhibited CSC-rich spheroids and overcame CRC cell resistance, suggesting that targeting cholesterol biosynthesis is a new approach for treating chemotherapy-resistant CRC. The same dilemma is faced in gastric cancer treatment, where trastuzumab resistance and poor subsequent chemotherapy efficacy have become major challenges in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive gastric cancer. Liang et al. [63] reported that HER2-positive gastric cancer cells are sensitive to cholesterol-lowering drugs and that combining these drugs with chemotherapy improved the efficacy of trastuzumab-resistant gastric cancer treatment. Pair immunoglobulin-like 2 receptor β (PILRB) has also been linked to gastric cancer resistance [64], with researchers finding that PILRB reprograms cholesterol metabolism by altering the expression of ABCA1 and SCARB1 and that high PILRB expression renders gastric cancer cells resistant to statin treatment. In resistant liver cancer cells, researchers [65] have reported that the mitochondrial cholesterol content increases significantly, and by inhibiting hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase or squalene synthase (SS) (the first enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis), sensitivity to chemotherapy is increased through mitochondrial mechanisms. In vivo, atorvastatin or an SS inhibitor (YM-53601) enhanced doxorubicin-mediated liver cancer growth arrest and cell death. In sorafenib-resistant liver cancer cells, the key regulator of cholesterol metabolism sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 2 (SREBF2) is activated, and further research revealed that SREBF2 positively correlates with StAR related lipid transfer domain containing 4 (STARD4), with overexpression of STARD4 reversing the impact of SREBF2 knockdown on mitochondrial cytochrome C release and sorafenib resistance [66]. Another group of researchers [67] reported increased expression of secreted acidic cysteine-rich protein (SPARC) in sorafenib-resistant liver cancer cells, and SPARC was associated with cholesterol homeostasis dysregulation and the occurrence and progression of liver cancer characterized by intrahepatic and early extrahepatic metastasis. Inhibiting SPARC expression or lowering cholesterol levels increased liver cancer cell sensitivity to sorafenib treatment. In resistant PDAC cells, the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway was upregulated, and HMGCS2, an enzyme rate-limiting cholesterol biosynthesis and ketogenesis, was overexpressed in resistance models. HMGCS2 may be a potential therapeutic target for treating gemcitabine-resistant PDAC [68].

In the clinical treatment of ovarian cancer, platinum-based chemotherapy (Pt) is the main therapeutic approach, but most patients develop Pt resistance (Pt-R). Wang et al. [69] reported that Pt-R ovarian cancer cells increase intracellular cholesterol uptake via the SR-B1. The research group synthesized low-cholesterol HDL-like nanoparticles (HDL-NPs) to block SR-B1, reducing cholesterol uptake and leading to cell death and inhibition of tumor growth. Further investigation revealed that chemotherapy resistance and cancer cell survival under high ROS loads were mediated by SREBF2, which upregulated GPX4 and SR-B1 expression. Targeting SR-B1 to regulate cholesterol uptake inhibited this axis, inducing ferroptosis in Pt-R ovarian cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. Another group of researchers [70] analyzed clinical patient samples and reported that ABCA10, a potential cholesterol transport protein, was highly expressed in ovarian tissue but downregulated in ovarian cancer tissues. Further studies revealed that transcription factor 21 (TCF21) promoted ABCA10 expression, lowering cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells by increasing mitochondrial cholesterol efflux, indirectly verifying that cholesterol accumulation in mitochondria is closely associated with resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Additionally, in melanoma [71], prostate cancer [72, 73], and other malignant tumors, researchers have reversed chemotherapy resistance by targeting cholesterol metabolism. In prostate cancer, a key area of concern is castration-resistant prostate cancer. Studies have shown that cholesterol not only serves as a precursor for androgen synthesis but also promotes cancer cell growth and survival through various mechanisms. In castration-resistant prostate cancer, cholesterol metabolism is reprogrammed to support the progression of castration-resistant disease [74]. Notably, inhibiting the activity of SR-B1, the primary receptor for HDL, has been shown to reduce the growth rate of castration-resistant prostate cancer cells, lower intratumoral androgen levels, and enhance treatment efficacy [75].

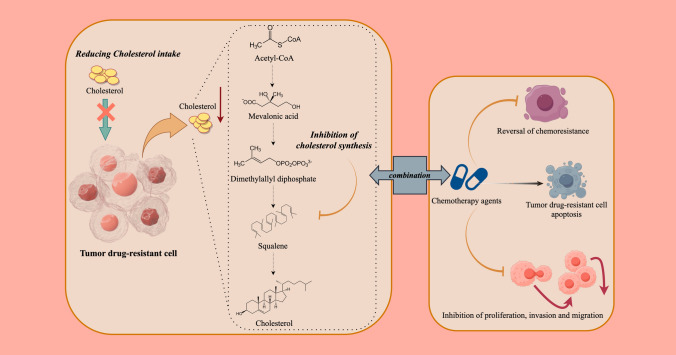

In conclusion, targeting cholesterol metabolism is a potential therapeutic strategy for treating chemotherapy resistance. Moreover, it is important to note that in certain types of cancer, exogenous cholesterol uptake is increased, while de novo synthesis is suppressed. This metabolic shift may represent an adaptive survival strategy of cancer cells. Studies have shown that the enhanced uptake of cholesterol may be regulated through the LDLR and other related pathways [76]. Meanwhile, the activation of antioxidant pathways may also play a crucial role in cancer cell survival and drug resistance [77]. In various cancers, inhibiting mevalonate metabolism pathways, reducing intracellular cholesterol levels, inhibiting cholesterol uptake and combining cholesterol biosynthesis-related gene inhibitors with anticancer drugs have shown excellent therapeutic effects in slowing resistant cell growth and inducing the apoptosis of resistant cells, thereby restoring sensitivity to drugs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Overview of cholesterol metabolism and tumor drug resistance. In various cancers, to address chemotherapy resistance, a common approach involves inhibiting the mevalonate metabolic pathways, thereby reducing intracellular cholesterol levels. This strategy often includes combining inhibitors of genes associated with cholesterol biosynthesis with anticancer drugs

A summary of cholesterol metabolism and tumor drug resistance is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cholesterol metabolism and tumor drug resistance

| Mechanisms of cholesterol in cancer drug resistance | Cancer types | References |

|---|---|---|

| The phosphorylated forms of growth factor receptors, downstream survival mediators pAKT, pmTOR, and pERK1/2, and phosphorylated estrogen receptor-α (pER-α at Ser-167 and Ser-118), along with cholesterol-rich lipid microdomains, are highly expressed in TAM-resistant cell lines and are further enhanced by TAM treatment | Breast cancer | [53] |

| miRNA-128 and miRNA-223 play critical roles in cholesterol-mediated TAM resistance. These miRNAs regulate the increase of free cholesterol and lipid rafts, rendering tumor cells resistant to TAM | [54] | |

| Prolonged exposure to EGFR-TKIs induces resistance accompanied by cholesterol accumulation in lipid rafts, promoting EGFR and Src interaction and leading to EGFR/Src/ERK signaling reactivation. This reactivation mediates SP1 nuclear translocation and ERRα re-expression, with ERRα identified as a target gene of SP1. ERRα re-expression supports cell proliferation by regulating ROS detoxification processes | Lung cancer | [56] |

| In PC9GR cells, the Hippo/YAP signaling pathway is activated. Pitavastatin suppresses YAP expression. YAP knockdown decreases the expression of pAKT, BCL-2 and phosphor-BCL2 associated agonist of cell death (pBAD), while increasing BCL2 associated x, apoptosis regulator (BAX) expression. Downregulation of YAP significantly enhances apoptosis and reduces survival in gefitinib-resistant lung cancer cells | [57] | |

| Gilteritinib induces cholesterol accumulation in LCCs by upregulating cholesterol biosynthesis genes and inhibiting cholesterol efflux. This accumulation weakens the antitumor effect of gilteritinib and promotes resistance in lung cancer cells | [58] | |

| Cholesterol synthesis is altered in osimertinib-resistant cells, with ERK1/2 activation leading to these changes. The combination of AETC and osimertinib synergistically reduces intracellular ROS levels, promotes apoptosis, and inhibits the growth of osimertinib-resistant cells | [59] | |

| Esophageal cancer cells treated with U18666A, a drug that increases mitochondrial cholesterol levels, exhibit protection against tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced apoptosis, reduced caspase-8 activation, and cisplatin resistance | Esophageal cancer | [60] |

| (S)−2,3-epoxy-squalene enhances the interaction between beta-transducin repeat containing e3 ubiquitin protein ligase (BTRC) and inhibitor kappa B alpha (IκBα), promoting IκBα degradation and subsequent NF-κB activation. Activated NF-κB upregulates baculoviral IAP repeat containing 3 (BIRC3) expression, maintaining tumor cell survival post-5-Fu treatment and promoting 5-Fu resistance in CRC | CRC | [61] |

| The loss of HMGCR or farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FDPS) activates the TGF-β signaling pathway, leading to the downregulation of differentiation inhibitory proteins, thereby impairing tumor stemness. Differentiation inhibitory proteins are key regulators of tumor stemness. Cholesterol and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate restore the growth inhibition and signaling effects disrupted by HMGCR/FDPS blockade, indicating that these metabolites directly regulate stemness | [62] | |

| Cdc42, a cholesterol driver, is activated through the formation of the npc intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1)- transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 (TβRI)-Cdc42 complex, facilitating endosomal cholesterol transport and plasma membrane enrichment, thereby influencing gastric cancer cell resistance | Gastric cancer | [63] |

| PILRB reprograms cholesterol metabolism by altering ABCA1 and SCARB1 expression. High PILRB expression renders gastric cancer cells resistant to statin therapy | [64] | |

| In liver cancer, chemotherapy sensitivity is enhanced by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase or SS, which catalyzes the first steps of cholesterol biosynthesis, through mitochondrial augmentation | Liver cancer | [65] |

| In sorafenib-resistant cells, the cholesterol metabolism regulator SREBF2 is activated. SREBF2 knockdown resensitizes sorafenib-resistant cells and xenografts to the drug. Further research indicates SREBF2 binds with STARD4, a mediator of cholesterol transport, which promotes liver cancer cell proliferation and migration and increases sorafenib resistance | [66] | |

| SPARC is highly expressed in sorafenib-resistant liver cancer cells, enhancing cholesterol accumulation by stabilizing ApoE protein. SPARC competitively binds ApoE, weakening its interaction with e3 ubiquitin-protein ligase tripartite motif containing 21 (TRIM21) and preventing its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. ApoE accumulation stimulates PI3K/AKT signaling and induces EMT, leading to cholesterol enrichment in cancer cells | [67] | |

| Cholesterol biosynthesis is upregulated in gemcitabine-resistant cells, with HMGCS2, a rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis and ketogenesis, overexpressed in resistant cells. Mechanistic studies indicate that HMGCS2 contributes to gemcitabine resistance and metastasis in PDAC models, and this process is dependent on bromodomain containing 4 (BRD4) | PDAC | [68] |

| Resistant cells increase intracellular cholesterol via HDL receptor SR-B1 uptake. Under high ROS loads, chemotherapy resistance and cancer cell survival are mediated by SREBF2-induced expression of GPX4 and SR-B1. Targeting SR-B1 to modulate cholesterol uptake inhibits this axis and induces ferroptosis in Pt-R ovarian cancer cells in vitro and in vivo | Ovarian cancer | [69] |

| Mitochondrial cholesterol accumulation in drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells, potentially associated with ABCA10, contributes to resistance. TCF21 promotes ABCA10 expression, enhancing mitochondrial cholesterol efflux and reducing cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells | [70] | |

| 27-OH-Chol, a major cholesterol metabolite synthesized by CYP27A1, is highly expressed in melanoma patients. CYP27A1 is upregulated by 24-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR24) and activates the Rap1-PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. The impact of cholesterol on melanoma resistance requires its metabolite 27HC, catalyzed by CYP27A1. Furthermore, 27HC upregulates Rap1A/Rap1B expression and increases AKT phosphorylation | Melanoma | [71] |

| Statin-resistant prostate cancer cells increase intracellular cholesterol by upregulating HMGCR expression and its transcription factor SREBP-2 | Prostate cancer | [72] |

| The transcription factor SREBF-1, involved in cholesterol and lipid biosynthesis, is highly expressed in resistant prostate tumor cells. SREBF-1 expression is significantly elevated in advanced prostate cancer tissues, suggesting its involvement in tumor progression and therapeutic resistance | [73] | |

| In castration-resistant prostate tumors, cholesterol uptake genes are highly expressed, and circulating cholesterol levels are directly correlated with tumor expression of CYP17A, a key enzyme required for the de novo synthesis of androgens from cholesterol. Inhibiting the activity of SR-B1, the primary receptor for HDL, has been shown to slow the growth of castration-resistant prostate cancer cells, reduce intratumoral androgen levels, and enhance treatment efficacy | [75] | |

| Compared to the normal cells, prostate cancer cells showed high expression of cholesterol-producing HMGCR but failed to express the major cholesterol exporter ABCA1. LDL increased relative cell number of cancer cell lines, and these cells were less vulnerable than normal cells to cholesterol-lowering simvastatin treatment | [76] | |

| Glioblastoma cells rely on external cholesterol for survival and lipid droplet accumulation to sustain their rapid growth. Therefore, targeting cholesterol metabolism through strategies such as activating LXRs, disrupting intracellular cholesterol transport, inhibiting cholesterol uptake, promoting cholesterol efflux, suppressing the SREBP signaling pathway, and preventing cholesterol esterification may help combat glioblastoma growth and drug resistance | Glioblastoma | [77] |

Antitumor therapy targeting cholesterol metabolism

Targeting cholesterol transport and absorption

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) plays a crucial role in lipid regulation by promoting the degradation of LDLR. Additionally, PCSK9 can bind directly to major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules on the surface of tumor cells, inducing their degradation and thereby weakening the antigen-presenting capacity of tumor cells. Studies have shown that knocking out PCSK9 significantly enhances this capacity [78]. Another molecule that regulates LDLR is an inducible degrader of LDLR (IDOL), which triggers LDLR degradation via ubiquitination and whose expression is transcriptionally regulated by LXRs. For example, the LXR agonist GW3965 accelerates LDLR degradation by increasing IDOL expression, thereby reducing intracellular cholesterol levels and inhibiting tumor growth [79, 80]. Regarding cholesterol absorption, Niemann‒Pick C1-like 1 protein (NPC1L1), a key molecule, plays a vital role in angiogenesis. Its inhibition significantly reduces tumor growth in prostate cancer [81] and liver cancer [82]. Moreover, NPC1L1 has been implicated in colorectal cancer development; knockout of NPC1L1 in mice significantly decreased the incidence of inflammatory colorectal cancer induced by azoxymethane and dextran sulfate sodium [83]. NPC1L1 is highly expressed in intestinal and biliary epithelial cells and on the surface of many tumor cells. Although the specific mechanisms by which NPC1L1 regulates tumor development remain unclear, its inhibitor ezetimibe, a clinically safe lipid-lowering drug, has the potential for further exploration of its antitumor effects and mechanisms. Cholesterol absorbed via LDLR is first transported to lysosomes and then distributed to the cell membrane, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum by Niemann‒Pick type C (NPC) proteins. If NPC function in lysosomes is impaired, cholesterol and phospholipids accumulate abnormally in lysosomes, causing lipotoxicity and triggering cell death [84]. Notably, itraconazole, an NPC inhibitor, suppresses the activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) via both cholesterol metabolism-dependent and cholesterol metabolism-independent pathways, thereby downregulating mTORC1 signaling, regulating angiogenesis in endothelial cells, and inhibiting tumor growth [85].

Targeting cholesterol synthesis

Although numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated the antitumor activity of targeting HMGCR and retrospective studies support the role of statins in cancer prevention and prognosis improvement [86–92], phase II/III randomized controlled trials in advanced CRC [93], lung cancer [94, 95], gastric cancer [96], and PDAC [97] have not shown a significant extension of progression-free survival or overall survival when statins are combined with standard treatments. These findings indicate that the antitumor effects of statins are largely limited to laboratory studies and retrospective analyses, with prospective randomized controlled trials failing to demonstrate notable efficacy. This may be attributed to statins activating SREBPs while reducing intracellular cholesterol levels, counteracting some of the drugs' benefits [98]. Additionally, in some refractory cancers, the efficacy of statins remains limited, particularly in cancer types with low cholesterol synthesis activity [99, 100]. In these cases, cancer cells exhibit poor responsiveness to statin therapy, likely because they rely more on exogenous cholesterol uptake rather than endogenous synthesis. As a result, researchers have begun focusing on pathways involved in exogenous cholesterol uptake to identify potential therapeutic targets [101, 102]. As mentioned earlier, PCSK9 inhibitors lower serum cholesterol levels by upregulating LDLR, a mechanism that may exert inhibitory effects on cholesterol-dependent cancer cells [103]. HMGCR is highly active in all proliferating cells and is not unique to tumor cells, suggesting that HMGCR may not be an effective antitumor target. In the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, another key rate-limiting enzyme, SQLE, is closely associated with the prognosis of various cancers, including lung cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and CRC [104]. The SQLE inhibitor terbinafine, a known antifungal agent, significantly inhibits the growth of CRC cells both in vitro and in vivo [32]. Further studies have shown that the oncogene c-myc promotes tumor growth by increasing SQLE expression and that SQLE knockout cell lines lose sensitivity to c-myc-induced changes in cholesterol levels, indicating the critical role of SQLE in c-myc-mediated tumor growth. Hence, SQLE is a potential therapeutic target for tumors with c-myc amplification [105]. Xiao et al. [106] demonstrated that gypenoside L reduced cholesterol and triglyceride levels in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells; inhibited cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis; and targeted the transcription factor SREBP2 to suppress HMGCS1 protein expression. This, in turn, downregulated the downstream proteins HMGCR and mevalonate kinase (MVK), regulating the mevalonate pathway.

Combination therapy targeting cholesterol metabolism

Although using antimetabolic drugs to modulate cholesterol metabolism in tumor cells alone may not significantly reduce tumor size, it can worsen the survival environment for tumor cells, thereby enhancing the efficacy of other treatments. As described in Sect. 4, combining cholesterol metabolism-targeting drugs with traditional endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy holds promise for improving therapeutic efficacy and overcoming drug resistance. For example, tamoxifen, a first-line drug for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients, acts through the estrogen receptor pathway and lowers intracellular cholesterol levels by inhibiting its lysosomal transport and synthesis. However, this feedback activates the SREBP-HMGCR pathway, potentially promoting tumor growth [107]. Combining lovastatin with tamoxifen significantly enhances its antitumor effects [108]. In prostate cancer, the second-generation androgen receptor inhibitor enzalutamide significantly upregulates HMGCR expression in resistant prostate cancer. Statins inhibit HMGCR activity and downregulate androgen receptor expression via the mTOR pathway. Studies have shown that combining simvastatin with enzalutamide successfully reverses resistance [109]. Additionally, prostate cancer cells undergoing chemotherapy with doxorubicin or cisplatin exhibit increased ABCG4 expression due to excessive glutathione depletion, leading to drug efflux and resistance. Simvastatin reverses resistance and enhances chemotherapy sensitivity by restoring intracellular glutathione levels and inhibiting ABCG4 expression [110]. In a mouse CRC xenograft model, simvastatin combined with 5-Fu chemotherapy prolonged survival [111]. In a liver cancer model, fluvastatin combined with sorafenib enhanced antitumor effects by inhibiting the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-related MAPK and NF-κB pathways [112]. Recent studies [113] have shown that lysosomal autophagy inhibition (LAI) using hydroxychloroquine or DC661 enhances the effectiveness of cancer therapy, although tumor relapse remains common in clinical treatments. Lipidomics has shown that LAI increases cholesterol, sphingolipid, and glycosphingolipid contents. Inhibiting cholesterol/sphingolipid metabolic proteins enhances LAI cytotoxicity. Targeting UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase (UGCG) synergistically increases LAI cytotoxicity. While UGCG inhibition reduces the LAI-induced accumulation of glycosphingolipids and increases cell death, UGCG overexpression causes LAI resistance. Patients with high UGCG expression in melanoma patients exhibit significantly shorter disease-specific survival. The FDA-approved UGCG inhibitor eliglustat combined with LAI significantly suppresses tumor growth and improves survival in tumor-bearing and drug-resistant patient-derived xenograft models.

A summary of antitumor therapies targeting cholesterol metabolism is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antitumor therapies targeting cholesterol metabolism

| Targeted pathway | Therapeutic agents | Mechanisms | Cancer types | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting cholesterol transport and absorption | GW3965 | The LXRs agonist GW3965 accelerates LDLR degradation by upregulating IDOL expression, thereby reducing intracellular cholesterol levels and inhibiting tumor growth | Glioblastoma | [80] |

| Ezetimibe | Regulation of key molecules related to cholesterol absorption, such as NPC1L1 | Prostate cancer, liver cancer, CRC | [81–83] | |

| Itraconazole | mTORC1 activation through cholesterol metabolism-dependent and independent pathways, thereby downregulating mTORC1 signaling, regulating endothelial cell angiogenesis, and inhibiting tumor growth | Lung cancer | [85] | |

| Avasimibe | Reduces cancer cell proliferation and migration, regulates the cell cycle, and increases reactive oxygen species production along with the upregulation of ROS metabolism-related proteins SOD2 and catalase | BLCA | [38] | |

| Targeting cholesterol synthesis | Statins | Targeting HMGCR demonstrates significant antitumor activity, with retrospective studies supporting the positive role of statins in tumor prevention and improving prognosis | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, liver cancer | [86–92] |

| Terbinafine | SQLE promotes colorectal cancer progression via the accumulation of calcitriol and stimulation of MAPK signaling mediated by cholesterol catalytic protein CYP24A1 | CRC | [32] | |

| Combination therapies targeting cholesterol metabolism | α-TEA + TAM | Inhibits pro-survival signaling by disrupting cholesterol-rich lipid microdomains and activates the mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis pathway via ER stress-induced phosphor-c-Jun N-terminal kinase/C/EBP homologous protein /death receptor 5 signaling, preventing TAM resistance | Breast cancer | [53] |

| Lovastatin + TAM | TAM reduces intracellular cholesterol levels by inhibiting cholesterol transport in lysosomes and its synthesis, which feedback activates the SREBPs-HMGCR pathway and may promote tumor growth. However, combining lovastatin with tamoxifen significantly enhances its antitumor effect | [108] | ||

| Gefitinib/Osimertinib + Lovastatin + XCT790 | Inhibits the survival of gefitinib and osimertinib-resistant cancer cells by targeting the cholesterol/EGFR/Src/Erk/SP1 axis to induce ERRα re-expression | Lung cancer | [56] | |

| Gefitinib + Pitavastatin | Pitavastatin reverses gefitinib resistance by modulating the YAP pathway, inhibiting downstream AKT/BAD-BCL-2 signaling, promoting apoptosis, and inhibiting resistant cell proliferation | [57] | ||

| Gilteritinib + NB-598/25HC | The SQLE inhibitor NB-598 restores gilteritinib sensitivity in resistant cells by blocking cholesterol synthesis. Additionally, the natural cholesterol inhibitor 25-OH-Chol suppresses cholesterol biosynthesis and increases cholesterol efflux, sensitizing resistant cells | [58] | ||

| Osimertinib + AETC | Combined application of AETC and osimertinib regulates ERK1/2, inhibits endogenous cholesterol synthesis, downregulates cholesterol biosynthesis key regulators in resistant cells and xenografts, reduces lipid levels, and ultimately reverses osimertinib resistance | [59] | ||

| Terbinafine + 5-Fu | The clinically used antifungal SQLE inhibitor terbinafine enhances 5-Fu sensitivity in CRC in vivo. Moreover, SQLE expression correlates with the prognosis of colorectal cancer patients treated with 5-Fu-based chemotherapy | CRC | [61] | |

| Lovastatin/Zoledronic Acid + 5-Fu/Oxaliplatin | Lovastatin or zoledronic acid effectively targets HMGCR or FDPS, inhibiting the self-renewal and tumorigenic potential of CSCs both in vitro and in vivo | [62] | ||

| Paclitaxel + ZCL278 | ZCL278 inhibits Cdc42 activation, reduces plasma membrane cholesterol levels, and reverses trastuzumab resistance in gastric cancer cells | Gastric cancer | [63] | |

| Atorvastatin/Squalene synthase inhibitor YM-53601 + Doxorubicin | Inhibits chemotherapy resistance in liver cancer cells by disrupting mitochondrial cholesterol’s role in cell membrane arrangement | Liver cancer | [65] | |

| Sorafenib + Fluvastatin | Sorafenib combined with fluvastatin enhances antitumor effects by inhibiting TLR4-related MAPK and NF-κB pathways | [112] | ||

| Gemcitabine + JQ1 | The bromodomain and extraterminal inhibitor JQ1 reduces HMGCS2 levels, sensitizing PDAC cells to gemcitabine, and gemcitabine combined with JQ1 reverses gemcitabine resistance in vivo | PDAC | [68] | |

| Dafadine-A + Vemurafenib | Cholesterol depletion or inhibition of CYP27A1 by dafadine-A abolishes vemurafenib-resistant cell characteristics, reducing Rap1A/Rap1B expression and AKT Thr308/309 phosphorylation | Melanoma | [71] | |

| Iruzole + Lysosomal autophagy inhibitors | Lipid remodeling driven by UGCG dependence promotes resistance to LAI. Targeting UGCG with lysosomal storage disorder drugs enhances LAI’s antitumor activity with minimal drug toxicity | [113] | ||

| Simvastatin + Enzalutamide | Simvastatin inhibits HMGCR activity and downregulates androgen receptor expression via the mTOR pathway. Studies show that combining simvastatin with enzalutamide successfully reverses resistance | Prostate cancer | [109] | |

| Simvastatin + Cisplatin/Doxorubicin | Simvastatin reverses drug resistance and enhances chemosensitivity by restoring intracellular glutathione levels and inhibiting ABCG4 expression in tumor cells | [110] |

Future research directions and clinical prospects

Although numerous studies have highlighted the importance of cholesterol metabolism in cancer, its precise mechanisms require further exploration. Elucidating the role of cholesterol metabolism in tumor cell proliferation, survival, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance could provide a theoretical basis for developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Currently available statins have demonstrated significant effects in lowering cholesterol levels and exhibiting antitumor activity. However, these effects are limited by certain clinical challenges. Literature reviews reveal that statins often show potent antitumor activity in in vitro studies but exhibit limited efficacy in in vivo and clinical studies. This discrepancy may stem from factors such as drug metabolism, tissue distribution, and insufficient plasma concentrations to achieve the dosage required for tumor growth inhibition. Furthermore, statins may affect both normal and tumor cells, potentially leading to adverse effects, particularly on liver function and muscles [114]. In clinical settings, the dosages required for antitumor effects are often higher than those used for cholesterol reduction, resulting in increased side effects and limiting their clinical utility. Additionally, most clinical trials evaluating the antitumor effects of statins are observational studies, with relatively few prospective randomized controlled trials, leading to limited evidence quality [115]. Future research should focus on exploring the synergistic mechanisms of statins with other antitumor agents and developing rational combination therapy protocols to improve efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. The development of novel statin derivatives or drug delivery systems, such as nanocarrier technologies, that target tumor-specific pathways could increase the selectivity and efficacy of antitumor therapies. Conducting large-scale, high-quality, multicenter clinical trials is essential to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of statins in cancer therapy, providing stronger evidence for their application. Clinically, a major challenge is that many refractory cancers exhibit inherently low cholesterol synthesis activity, making them less responsive to statin therapy. Therefore, targeting pathways involved in exogenous cholesterol uptake may represent a promising avenue for exploration, including in clinical trials. The author believes that integrating cholesterol uptake pathways with emerging research directions could serve as an alternative therapeutic strategy beyond inhibiting de novo cholesterol synthesis, such as through statin use.

In summary, statins hold promise as an antitumor therapy but face challenges related to complex mechanisms of action, insufficient efficacy, and safety concerns. Through in-depth research and technological innovation, statins may play a greater role in cancer treatment. Combining cholesterol metabolism inhibitors with other antitumor therapies, such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immune checkpoint inhibitors, is crucial for future cancer therapy. Multitargeted intervention strategies could improve therapeutic outcomes, overcome tumor resistance, and prolong patient survival.

Conclusion

Cholesterol metabolism is pivotal in tumor initiation, progression, and treatment. Cholesterol not only maintains the physical properties of cell membranes and participates in cellular signaling but is also closely associated with reprogramming endogenous and exogenous signals within the tumor microenvironment. These signals are tightly linked to critical biological processes such as tumor cell proliferation, survival, invasion, and metastasis. Modulating cholesterol metabolism can inhibit tumor growth, reshape the immune microenvironment, and enhance antitumor immune responses. This review aims to provide theoretical and practical guidance for developing new antitumor strategies by delving into the specific mechanisms of cholesterol metabolism in tumor biology. However, despite substantial theoretical support from existing studies, inconsistencies in clinical data and limited statistical analyses reduce the reliability of conclusions. Moreover, the author acknowledges personal academic limitations and the relatively small scope of the included studies, which impose certain constraints on this research. The exploration of cholesterol metabolism in cancer therapy still holds considerable potential. Future studies should focus on deepening our understanding of the mechanisms by which cholesterol metabolism influences tumor progression. Building on this foundation, new therapeutic strategies can be developed to increase the efficacy of targeted cholesterol metabolism inhibitors in combination with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Such approaches are promising for advancing cancer treatment and may become an important tool in future oncology practice.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the figures drawn by using Figdraw.

Abbreviations

- 22-OH-Chol

22-Hydroxycholesterol

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- ACAT: acyl-coenzyme A

Cholesterol acyltransferase

- AGFG1

ArfGAP with FG repeats 1

- AIBP

Polipoprotein A-1 binding protein

- APC

Adenomatous polyposis coli

- ApoE2

Apolipoprotein E2

- ASGR1

Asialoglycoprotein receptor 1

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BAX

BCL2 associated x, apoptosis regulator

- BIRC3

Baculoviral IAP repeat containing 3

- BLCA

Bladder cancer

- BRD4

Bromodomain containing 4

- BTRC

Beta-transducin repeat containing e3 ubiquitin protein ligase

- CAV1

Caveolin 1

- CCNA1/2

Cyclin a1/2

- CCND1

Cyclin d1

- CDK2/4

Cyclin-dependent kinase 2/4

- CE

Cholesterol ester

- CRAC

Cholesterol recognition/interaction amino acid consensus

- CRC

Colorectal cancer cell

- CSC

CRC stem cell

- CXCR2

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2

- CYP

Cytochrome p450 family

- DC

Dendritic cell

- DDA

Dendrogenin A

- DHCR24

24-Dehydrocholesterol reductase

- EGFR-TKI

Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- EMT

Epithelial‒mesenchymal transition

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERK

Extracellular regulated protein kinase

- ERRα

Estrogen-related receptor alpha

- ESTIMATE

Estimation of stromal and immune cells in malignant tumor tissues using expression data

- FDPS

Farnesyl diphosphate synthase

- FPP

Farnesyl pyrophosphate

- GGH

γ-Glutamyl hydrolase

- GLUT1

Glucose transporter type 1

- GPX4

Glutathione peroxidase 4

- HDL-NP

Low-cholesterol HDL-like nanoparticle

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HMG-CoA

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A

- HMGCR

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase

- HMGCS1

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1

- IDOL

Inducible degrader of LDLR

- INSIG1

Insulin induced gene 1

- IκBα

Inhibitor kappa B alpha

- KLF13

Kruppel-like factor 13

- LAG-3

Lymphocyte-activation gene 3

- LAI

Lysosomal autophagy inhibition

- LDHA

Lactate dehydrogenase A

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDLR

Low-density lipoprotein receptor

- LRP8

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8

- LXR

Liver X receptor

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MHC-I

Major histocompatibility complex class I

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- mTORC1

Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1

- MVK

Mevalonate kinase

- NPC1

NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1

- NPC1L1

Niemann‒Pick C1-like 1

- NRF1

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1

- pBAD

Phosphor-BCL2 associated agonist of cell death

- PCSK9

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PI3 K/AKT

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase b

- PILRB

Pair immunoglobulin-like 2 receptor β

- PKM

Pyruvate kinase m1/2

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- Pt-R

Platinum-based chemotherapy resistance

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SCAP

SREBP cleavage-activating protein

- SCARB1

Scavenger receptor class b member 1

- SOD2

Superoxide dismutase 2

- SPARC

Secreted acidic cysteine-rich protein

- SQLE

Squalene epoxidase

- SR-B1

HDL receptor B-1-type scavenger receptor

- SREBF2

Sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 2

- SREBP-2

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2

- SS

Squalene synthase

- STARD4

StAR related lipid transfer domain containing 4

- TAM

Tamoxifen

- TCF21

Transcription factor 21

- TIM-3

T-cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain-3

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- TP53

Tumor protein p53

- TRIM21

Tripartite motif containing 21

- TTN

Titin

- TβR1

Transforming growth factor beta receptor 1

- UGCG

UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase

- XBP1

X-box binding protein 1

- α-TEA

RRR-α-tocopherol ether-linked acetic acid analog

- ccRCC

clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Author contributions

ZC completed the initial drafting of the manuscript, literature collection, and preparation of figures and tables. LF provided guidance on the writing and structure of the article. YX contributed to the design of the article’s structure and provided support through project funding. YD assisted in designing the article’s structure, editing and revising the manuscript, and offering project funding support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 82374002), the Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (Grant Number: 22XD1423000), the Key Discipline Construction Project of Shanghai's Three Year Action Plan for Strengthening the Construction of Public Health System (Grant No.: GWVI-11.1-24), the Shanghai 2022 ‘Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan’ Medical Innovation Research Special Project (Grant No.: 22Y11922200), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No.: 2024M762107).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yanwei Xiang, Email: xiangyanwei@shutcm.edu.cn.

Yue Ding, Email: dingyue-2001@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Luo J, Yang H, Song BL. Mechanisms and regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:225–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iuliano L. Pathways of cholesterol oxidation via non-enzymatic mechanisms. Chem Phys Lipids. 2011;164:457–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheepers R, Araujo RP. Robust homeostasis of cellular cholesterol is a consequence of endogenous antithetic integral control. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1244297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hulce JJ, Cognetta AB, Niphakis MJ, Tully SE, Cravatt BF. Proteome-wide mapping of cholesterol-interacting proteins in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2013;10:259–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker CD, Risher WC, Risher ML. Regulation of synaptic development by astrocyte signaling factors and their emerging roles in substance abuse. Cells. 2020;9:297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao M, Luo J, Gu T, Yu X, Song Z, Jun Y, et al. LPCAT1 reprogramming cholesterol metabolism promotes the progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giacomini I, Gianfanti F, Desbats MA, Orso G, Berretta M, Prayer-Galetti T, et al. Cholesterol metabolic reprogramming in cancer and its pharmacological modulation as therapeutic strategy. Front Oncol. 2021;11: 682911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghanbari F, Fortier AM, Park M, Philip A. Cholesterol-induced metabolic reprogramming in breast cancer cells is mediated via the ERRα pathway. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warns J, Marwarha G, Freking N, Ghribi O. 27-hydroxycholesterol decreases cell proliferation in colon cancer cell lines. Biochimie. 2018;153:171–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mok EHK, Leung CON, Zhou L, Lei MML, Leung HW, Tong M, et al. Caspase-3-induced activation of SREBP2 drives drug resistance via promotion of cholesterol biosynthesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2022;82:3102–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husain A, Chiu YT, Sze KM, Ho DW, Tsui YM, Suarez EMS, et al. Ephrin-A3/EphA2 axis regulates cellular metabolic plasticity to enhance cancer stemness in hypoxic hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;77:383–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Picarda E, Ren X, Zang X. Tumor cholesterol up. T Cells Down Cell Metab. 2019;30:12–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kopecka J, Godel M, Riganti C. Cholesterol metabolism: at the cross road between cancer cells and immune environment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2020;129: 105876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weis HJ. Der Stoffwechsel des Cholesterols [Cholesterol metabolism]. Klin Wochenschr. 1970;48:1203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortes VA, Busso D, Maiz A, Arteaga A, Nervi F, Rigotti A. Physiological and pathological implications of cholesterol. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2014;19:416–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirtori CR, Corsini A, Ruscica M. The role of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in 2022. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2022;24:365–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen WJ, Azhar S, Kraemer FB. SR-B1: a unique multifunctional receptor for cholesterol influx and efflux. Annu Rev Physiol. 2018;80:95–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPherson R, Gauthier A. Molecular regulation of SREBP function: the Insig-SCAP connection and isoform-specific modulation of lipid synthesis. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:201–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu Q, Yang X, Lv J, Zhang J, Xia B, Kim JD, et al. AIBP-mediated cholesterol efflux instructs hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell fate. Science. 2019;363:1085–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]