Abstract

Background

Drug prices affect government budgets directly through spending on public programs like Medicare and Medicaid, and indirectly via private coverage for public employees and tax subsidies for private insurance. Yet, the Senate parliamentarian ruled that the Senate could not use streamlined Budget Reconciliation to extend the Inflation Reduction Act’s controls on insulin co-payment or drug prices to private insurers on the grounds that their expenditures do not affect the federal budget.

Objective

To quantify insulin and other drug costs borne by federal, state, and local governments, including direct expenditures and indirect government subsidies that flow through private insurers.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of expenditures for outpatient retail prescription drugs reported by respondents and their pharmacies in the 2019 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (adjusted downward for drug rebates), supplemented with information on employment-related insurance from the US Office of Management and Budget and other sources.

Participants

The civilian non-institutionalized US population.

Main Measures

Direct (payments by public health insurance programs) and indirect (taxpayer-funded payments via private insurers) government expenditures for outpatient retail drugs.

Key Results

Direct government expenditures for outpatient retail prescription drugs totaled $154.85 billion in 2019, including $15.68 billion for insulin. Indirect government expenditures channeled through private insurers totaled $53.59 billion (including $5.48 billion for insulins). Those indirect expenditures encompassed $32.32 billion in tax subsidies for employer-sponsored private coverage, $25 million for subsidies to private Affordable Care Act marketplace plans, and $21.24 billion for government-paid premiums for public employees and retirees. Overall, government expenditures for outpatient retail prescription drugs totaled $208.44 billion, 58.76% of all-payer spending and 65.96% of spending for insulin.

Conclusions

Governments directly or indirectly fund most drug purchases, including substantial expenditures that flow through private insurers. Hence, prices paid by private insurers impact government budgets, supporting the view that government should be allowed to regulate drug prices.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-024-09032-x.

KEY WORDS: costs and spending, prescription drugs, insurance coverage and benefits, Medicare, Medicaid, private health insurance, diabetes

INTRODUCTION

High drug prices and costs have triggered widespread concern. Nearly one-third of American adults report that they have failed to take a medication as prescribed due to cost within the past 12 months and 83% favor government negotiating drug prices for both Medicare and private insurers.1

The hardships imposed by high and escalating insulin prices have drawn particular attention; 7.6 million Americans use insulin to manage their diabetes.2 Medicare Part D plans alone spent $13.3 billion on insulin in 2017, up from $1.4 billion in 2007.3 Meanwhile, list prices for insulin—which are reflected in out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for the uninsured and for those with insurance before they meet their annual deductible—increased more than 250% between 2007 and 2018.4 High OOP costs contribute to medication non-adherence and insulin rationing, and even, reportedly, to several deaths.5–7

In response to public concern, several bills proposing caps on OOP costs for insulin have been introduced since 2021, including the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act, the Affordable Insulin Now Act, and the Build Back Better Act. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) imposed penalties on drug firms that raised prices faster than inflation, a $35/month cap on OOP insulin costs for patients, and negotiations over the prices Medicare pays for some drugs. Initial versions of the IRA would have applied the penalties and caps to prescriptions for patients covered by private insurance as well as those with Medicare. However, the Senate parliamentarian ruled that list price and OOP spending limits for the privately insured would not affect the federal budget, precluding passage under the Senate’s budget reconciliation process that allows passage with a simple (rather than the usual 60%) majority vote. As a result, those provisions were stripped from the final bill.8,9

The parliamentarian’s ruling could affect future Congressional efforts to regulate drug prices and other costs paid by private insurance. Yet, such costs might impact the federal budget in several ways. The federal government purchases private coverage for millions of federal workers, military families, and retirees. Additionally, it subsidizes private coverage through the Affordable Care Act exchanges and provides tax subsidies that defray a substantial portion of the costs of employer-sponsored private coverage for private-sector workers. Finally, although state and local government expenditures for prescription drugs do not affect the federal budget, and hence are not relevant to the parliamentarian’s ruling, estimates of such expenditures may inform state-level efforts to address drug costs.

We sought to comprehensively assess the extent of taxpayer spending for insulin and for all outpatient retail prescription drugs in 2019.

DATA AND METHODS

We analyzed data on insurance coverage, type of employer, and payments for prescription medications from the 2019 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Full-Year Consolidated Data File and Prescribed Medicines File. The MEPS, described in detail elsewhere,10 is a nationally representative survey that collects detailed information on health care coverage, health care use, and expenditures by and for the civilian, non-institutionalized US population.

MEPS queries respondents about prescription fills (including refills) and obtains information on the amounts paid and sources of payment from their pharmacies (including mail order pharmacies). The sources of payments include those made by patients OOP, as well as insurance payments from both private and public insurers. We identified all filled prescriptions, which MEPS categorized according to the Multum Lexicon Therapeutic Classification Scheme.11 We further subcategorized insulins according to duration of effect/rapidity of onset and examined individual insulin types.

We determined mean payments per prescription for each drug category, as well as for the insulin subcategories. Because MEPS data represents payments to pharmacies, it does not account for rebates that manufacturers often pay to insurers. Hence, we also report figures adjusted downward based on a published estimate of that rebates averaged 21% overall, including 22% for Medicare Part D, 51% for Medicaid, 12% for all private insurers, and 21% for “other” federal and state payers.12 We assumed that no rebates are paid to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). For a sensitivity analysis, we calculated rebates assuming 27% rebates for all non-VHA payers, based on a detailed study of rebates in Colorado in 2019.13

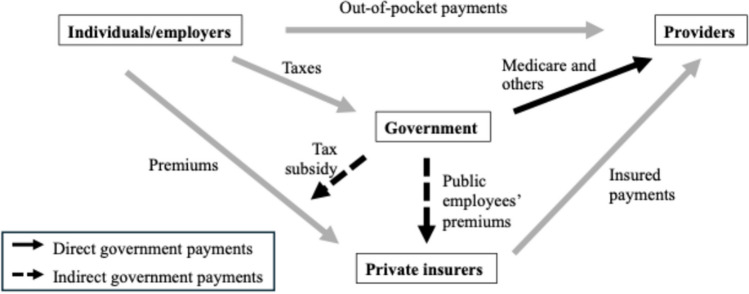

Figure 1 displays the conceptual model of the flow of funds for outpatient retail prescription drug purchases underlying our analysis. Table 1 summarizes the data sources and calculations used in our analysis.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of flows of payments from individuals, employers, private insurers, and government to pharmacies for outpatient retail prescription drugs.

Table 1.

Sources of Data and Methods Used to Estimate Government Expenditures for Outpatient Retail Prescription Drugs

| Payer category | Data source | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Direct government payments | ||

| Medicare | MEPS* | Sum of Medicare-paid expenditures, with and without rebates |

| Medicaid | MEPS* | Sum of Medicaid-paid expenditures, with and without rebates |

| VA | MEPS* | Sum of VA-paid expenditures, assumes no rebates |

| Other federal | MEPS* | Sum of expenditures paid by “Other Federal Programs,” with and without rebates |

| Other state/local | MEPS* | Sum of expenditures paid by “Other State and Local Payer,” with and without rebates |

| Subtotal of direct government payments | Sum of categories above | |

| Indirect government expenditures through taxpayer contributions to private insurance payments | ||

| Tax subsidies for private insurance | ||

| Employer-sponsored insurance | MEPS*; Office of Management and Budget (total federal tax subsidy), Quarterly Survey of State and Local taxes (ratio of state:federal income tax receipts), and NHEA (government employers’ share of employer payments for private coverage) | [Sum of payments by employer-paid private insurance] × [private employers’ share of all employer-paid private insurance] × [(federal + state and local tax subsidies)/total employer payments for employees’ premiums] |

| ACA exchange plans | MEPS*; CMS Health Insurance Exchange 2019 Open Enrollment Report | Sum of expenditures paid by ACA exchange plans × share of ACA exchange premiums paid by government |

| Government expenditures for public employees’ and retirees’ private health insurance | ||

| Federal employees | MEPS*; Office of Personnel Management | Sum of private insurance expenditures on behalf of federal employees and dependents × share of premiums paid by federal government |

| State/local employees | MEPS*; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | Sum of private insurance expenditures on behalf of state and local government employees × share of premiums paid by state and local governments |

| Civilian TRICARE enrollees | MEPS*; US Government Accountability Office | Sum of TRICARE expenditures on behalf of civilians × share of TRICARE premiums paid by federal government |

| Subtotal of indirect government expenditures | Sum of 5 categories above | |

See text for rebate percentages incorporated in rebate-adjusted figures

NHEA National Health Expenditure Accounts

*Authors’ analysis of data from 2019 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Our estimates encompass direct as well as indirect taxpayer spending in 2019 for all outpatient retail drugs (i.e., excluding those administered in hospitals, clinics, or physicians’ offices, which are not reported in the MEPS data) combined and for insulins. To calculate direct spending by government health programs, we summed payments to pharmacies by Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Health Administration, and smaller federal, state, and local government programs.

We assessed several types of indirect government payments for medications, i.e., taxpayer-funded payments that flow through private insurers. First, to calculate expenditures for civilian government workers (and their dependents) covered by employer-based private insurance, we identified such respondents based on the MEPS variable indicating employer type. We summed private insurers’ payments for drugs on their behalf and deflated these figures by the percentage of premiums paid by workers themselves: 11% for federal workers and their families (based on US Office of Personnel Management figures on the proportion of family and individual coverage, and the weighted average of federal employees’ share of private coverage) and 21% for state and local government employees and their families (based on figures from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).14,15

We used similar methods to estimate the federal government’s 88% share of drug costs paid by the Department of Defense’s TRICARE program on behalf of US-based civilians, e.g., dependents of military personnel and military retirees.16

To estimate indirect tax expenditures due to tax subsidies for workers with employment-based coverage, we calculated tax subsidies’ share of premiums paid to private insurers using previously published methods.17,18 We first obtained the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) 2019 estimates of the value of the federal income tax and payroll tax subsidies (which the OMB labels “tax expenditures”) to health care and health insurance.19 While state/local governments that impose income taxes also indirectly subsidize employment-based insurance through taxes, no published estimates of these subsidies are available. Hence, we estimated state and local income tax subsidies to health insurance premiums in 2019 by multiplying the value of the federal income tax subsidy by the ratio of (local + state) income tax receipts to federal income tax receipts. We calculated this ratio using data from the Census Bureau’s quarterly surveys of state and local taxes.20 Together, the value of federal and state tax subsidies is equivalent to 24.52% of expenditures for employer-sponsored private coverage.

To avoid double-counting tax subsidies received by government employees, we adjusted the tax subsidy estimates downward based on the share of employer-sponsored coverage paid by state/local and federal government employers reported in the National Health Expenditure Accounts.21

Finally, we used CMS figures on Advanced Payment Tax Credits for private coverage purchased through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace Health Insurance Exchanges to estimate the proportion (76.6%) of exchange coverage (and hence payments for prescription drugs) attributable to public funds.22

To account for prescription drug rebates, we adjusted all figures downward by rebate amounts, as noted above.

All analyses used Stata version 17 procedures that account for the survey’s complex design and MEPS-provided weights to derive nationally representative estimates. The authors’ IRB does not consider analyses of de-identified, public-use data to be human subjects research.

RESULTS

Of MEPS participants, 16,856 filled 289,675 prescriptions (weighted n = 3,085,807,573), including 5741 (weighted n = 56,237,258) for insulins. Among the 16 categories of drugs, cardiovascular agents accounted for the largest share (20.3%) of prescriptions, but only 5.4% of total payments (Table 2). While metabolic agents (including insulins) accounted for a somewhat smaller share of outpatient prescriptions (15.3%), they represented 21.2% of all payments, nearly twice the payment share of the second costliest category—central nervous system agents.

Table 2.

Outpatient Retail Prescription Drugs by Drug Category, Mean Costs per Prescription Fill, and Percent of Total Prescription Fills and Costs, in 2019

| Drug category | All drug prescriptions by category (unweighted n = 289,675) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean payment per prescription | % of prescriptions | % of payments | ||

| Unadjusted* | Adjusted† | |||

| Metabolic agents (including insulins) | $202 | $160 | 15.3 | 21.2 |

| Miscellaneous and unclassified agents | $613 | $484 | 3.4 | 14.1 |

| Central nervous system agents | $91 | $72 | 18.2 | 11.3 |

| Immunologic agents | $3047 | $2407 | 0.3 | 7.1 |

| Antineoplastics | $1388 | $1097 | 0.7 | 6.8 |

| Respiratory agents | $153 | $121 | 6.3 | 6.7 |

| Anti-infectives | $193 | $152 | 4.7 | 6.2 |

| Cardiovascular agents | $38 | $30 | 20.3 | 5.4 |

| Coagulation modifiers | $346 | $273 | 2.0 | 4.8 |

| Psychotherapeutic agents | $84 | $66 | 8.3 | 4.8 |

| Hormones/hormone modifiers | $68 | $54 | 7.8 | 3.7 |

| Topical agents | $116 | $92 | 4.6 | 3.6 |

| Gastrointestinal agents | $86 | $68 | 4.8 | 2.8 |

| Genitourinary tract agents | $249 | $197 | 0.5 | 2.8 |

| Nutritional products | $33 | $26 | 2.7 | 0.6 |

| Alternative medicines | $75 | $59 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

Source: Authors’ calculations from the 2019 MEPS. All figures are weighted to be nationally representative

*Average of amounts paid by individual respondents and their insurers

†Adjusted downward by 21% to account for estimated prescription drug rebates for all payers combined

Per-prescription-fill costs were highest for immunologic agents ($2407 adjusted for rebates) and antineoplastics ($1097 adjusted for rebates) (Table 2). As a result, although each of these categories accounted for fewer than 1% of prescription fills, each represented about 7% of prescription drug costs.

Table 3 displays figures on the frequency and cost of insulin prescription fills according to type of insulin. Adjusted cost per insulin prescription averaged $570 (unadjusted $722), which differed minimally across major payors (data not shown). Long-acting insulins were 43.6% of insulin prescriptions. Novolog, Humalog, and Lantus together accounted for more than half of all fills and costs. Per-fill costs were highest for Novo Nordisk’s Fiasp, Novolog (both of which are brand name versions of Aspart), and Tresiba, and were lowest for generic Aspart (also made by Novo Nordisk).

Table 3.

Outpatient Retail Insulin Prescriptions by Insulin Type, Names, Manufacturer, Mean Cost per Prescription Fill, and Percentage of Total Insulin Prescription Fills and Costs, in 2019

| Type | Insulin prescriptions by type (unweighted n = 5741) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | |||||||

| Generic name | Product name* | Manufacturer | Mean payment per prescription fill | % of insulin prescriptions | % total insulin payments | ||

| Unadjusted† | Adjusted‡ | ||||||

|

Rapid acting Short/intermediate Acting |

Aspart | Novolog | Novo Nordisk | $1089 | $860 | 17.1 | 25.2 |

| Novo FlexPen | Novo Nordisk | $356 | $281 | 0.6 | 0.3 | ||

| Fiasp | Novo Nordisk | $1253 | $990 | 0.2 | 0.0 | ||

| Aspart | Novo Nordisk | $67 | $53 | 0.2 | 0.0 | ||

| Lispro | Humalog | Eli Lilly | $816 | $645 | 15.2 | 16.6 | |

| Admelog | Sanofi-Aventis | $233 | $184 | 1.7 | 2.2 | ||

|

Short/intermediate acting Long acting |

Regular insulin/NPH | Humulin R/N | Eli Lilly | $914 | $722 | 5.2 | 6.6 |

| Novolin R/N | Novo Nordisk | $271 | $214 | 4.5 | 1.8 | ||

|

Long acting Ultralong acting |

Glargine | Lantus | Sanofi-Aventis | $565 | $446 | 20.7 | 15.5 |

| Basaglar | Eli Lilly | $380 | $300 | 9.0 | 5.3 | ||

| Toujeo | Sanofi-Aventis | $902 | $713 | 3.4 | 4.6 | ||

| Glargine | Eli Lilly/Sanofi-Aventis | $201 | $159 | 0.7 | 0.3 | ||

| Solostar | Sanofi-Aventis | $245 | $194 | 0.3 | 0.1 | ||

| Detemir | Levemir | Novo Nordisk | $680 | $537 | 9.9 | 9.3 | |

| Ultralong acting | Degludec | Tresiba | Novo Nordisk | $1088 | $860 | 6.5 | 10.1 |

| Unknown | Insulin, misc | N/A | N/A | $456 | $360 | 0.5 | 3.1 |

Source: Authors’ calculations from the 2019 MEPS. Figures are weighted to be nationally representative

*Name reported in MEPS data file

†Average of amounts that individuals and their insurers paid per prescription fill

‡Adjusted downward by 21% to account for estimated prescription drug rebates for all payers combined

Prescription drug payments to pharmacies totaled $449.00 billion, equivalent to $354.71 billion after adjustment for rebates (Table 4). Payments for insulins totaled $40.60 billion unadjusted and $32.07 billion adjusted, 9.04% of the payments for all prescription medications. A sensitivity analysis using 2019 Colorado rebate figures yielded an adjusted estimate of $327.77 billion for total outpatient drug expenditures and $29.64 billion for insulins (Supplementary Table).

Table 4.

Taxpayers’ Contributions to Retail Prescription Payments for All Drugs and for Insulins, in 2019

| All prescriptions (unweighted n = 289,675) | Insulin (unweighted n = 5741) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted (millions of dollars) | Adjusted for rebates (millions of dollars) | % of total | Unadjusted (millions of dollars) | Adjusted for rebates (millions of dollars) | % of total | |

| Total payments for prescriptions | $449,000 | $354,710 | 100 | $40,600 | $32,074 | 100 |

| Direct government payments | ||||||

| Medicare Part D | $157,000 | $122,460 | 34.52 | $16,500 | $12,870 | 40.13 |

| Medicaid | $46,800 | $22,932 | 6.46 | $4150 | $2034 | 6.34 |

| VA | $5390 | $5390 | 1.52 | $330 | $330 | 1.03 |

| Other federal | $2520 | $1991 | 0.56 | $321 | $254 | 0.79 |

| Other state/local | $2630 | $2078 | 0.59 | $242 | $191 | 0.60 |

| Subtotal of direct government payments | $214,340 | $154,851 | 43.66 | $21,543 | $15,679 | 48.88 |

| Indirect government expenditures through taxpayer contributions to private insurance payments | ||||||

| Tax subsidies for private insurance | ||||||

| Employer-sponsored insurance | $36,732 | $32,324 | 9.11 | $3752 | $3302 | 10.29 |

| ACA exchange plans 12% rebate | $28 | $25 | 0.01 | $0.44 | $0.38 | 0.00 |

| Government expenditures for public employees’ and retirees’ private health insurance | ||||||

| Federal employees | $2265 | $1993 | 0.56 | $81.44 | $71.67 | 0.22 |

| State/local employees | $15,808 | $13,911 | 3.92 | $1904 | $1676 | 5.22 |

| Civilian TRICARE enrollees | $6060 | $5333 | 1.50 | $489 | $430 | 1.34 |

| Subtotal of indirect government expenditures | $60,893 | $53,586 | 15.11 | $6227 | $5480 | 17.08 |

| Total tax-financed expenditures | $275,233 | $208,437 | 58.76 | $27,770 | $21,159 | 65.96 |

Source: Authors calculations from the 2019 MEPS. All figures are weighted to be nationally representative. Figures for total payments, other federal, and other state are adjusted downward by 21% to account for estimated rebates. Figures for Medicare are adjusted downward by 22% for rebates. Figures for Medicaid are adjusted downward by 51% for rebates. Figures for all indirect government expenditures are adjusted downward by 12%, the average rebate for private insurers

Taxpayers’ share of payments for all outpatient retail drugs totaled 58.76% (Table 4). Direct government payments by Medicare, Medicaid, the VHA, and other government programs accounted for 43.66% of all payments. Indirect payments by federal, state, and local governments that flowed through private insurers totaled $53.59 billion adjusted for rebates ($60.89 billion unadjusted), accounting for 15.11% of total outpatient retail drug expenditures, including 9.11% for tax subsidies to employer-sponsored coverage, and 5.98% for taxpayers’ share of public employees’ and TRICARE premiums. The sensitivity analysis using 2019 Colorado rebate figures (Supplementary Table) yielded estimates that taxpayers’ expenditures for outpatient retail drugs totaled $200.92 billion, 61.30% of total expenditures for such drugs.

Taxpayers’ share of insulin costs amounted to $21.16 billion adjusted for rebates ($27.77 billion unadjusted), 65.96% of total expenditures for insulin, somewhat larger than taxpayers’ share of payments for other prescription drugs. Direct federal, state, and local government payments accounted for 48.88% of insulin spending, and indirect payments for 17.08% ($6.23 billion unadjusted, $5.48 billion adjusted for rebates), 10.29% for tax subsidies, and 6.78% for taxpayers’ share of premium costs for public employees and TRICARE.

DISCUSSION

Taxpayers pay for 58.76% of all outpatient retail prescription drugs and almost two-thirds of insulin purchases. These figures are considerably higher than those reported in the usual tabulations of sources of payment for medications. Those tabulations reflect who “wrote the check” to the pharmacy, rather than who ultimately picked up the bill; payments made by private insurers on behalf of a government employee are labeled “private,” even if a government entity paid the entire premium. Similarly, tax subsidies to employer-sponsored coverage are not counted in National Health Expenditure Accounts tabulations,21 or estimates by Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Inspector General.23

Although health policy experts (and both the OMB and Congressional Budget Office (CBO)) are aware of these indirect sources of government payments for care, others (apparently including the Senate Parliamentarian) often fail to take account of them. A CBO document prepared after the Parliamentarian’s ruling estimated that savings for commercial insurers from provisions that remained in the IRA would reduce federal deficits by $2 billion over a decade.24 However, we could identify no official estimates tabulating potential government savings from the more broadly applicable price reductions in the bill’s original version, or of government expenditures—including indirect expenditures that flow through private insurers—for prescriptions drugs.

Prior studies have estimated individuals’ out-of-pocket spending for insulin and costs paid by private insurers and Medicare,1,25 but none have assessed overall government spending for insulin. The HHS Office of Inspector General estimated that HHS programs accounted for 41% of prescription drug funding in 2019 (approximately $151 billion).26 This estimate is similar to our adjusted estimate of direct government spending through such programs after adjusting for rebates, but does not include the additional $53.59 billion we estimate flows through indirect sources.

Hence, the full budgetary impact of high prices for insulin and other drugs, and potential savings for government from price controls or negotiations have been obscured. Our figures suggest that reducing US insulin prices to the Canadian or UK levels—respectively 88% and 92% lower than the US27—would have saved US taxpayers as much as $19.5 billion in 2019 (92% of our calculation of taxpayer payments for insulin).

Our analysis has several limitations. No comprehensive and reliable figures are available on rebates paid to insurers. Hence, our figures for net costs rely on published estimates of such rebates. Our primary analysis using payer-specific estimates of rebates yielded estimates of taxpayer payments for medications slightly lower than the more recent Colorado-based estimate of the all-payer average rebate. Other sources using varying methods suggest somewhat higher rebates,28 and rebate levels have likely increased since 2019. However, while calculations assuming higher rebates would decrease our dollar estimates of government expenditures, our estimates of the fraction paid by governments would not be greatly affected since both numerators and denominators would decrease. Furthermore, rebate prices are estimated to increase in tandem with list prices, often at a slightly lower rate.29

MEPS’ exclusion of persons in institutions, where public payment predominates, likely leads us to underestimate public payments, particularly for Medicaid and Medicare coverage of nursing home residents. However, it is reassuring that our rebate-adjustment yielded estimates of outpatient prescription drug expenditures overall, and by Medicare and Medicaid, that are similar to those provided by the National Health Expenditures Accounts.

Because our estimates encompass only outpatient prescription medications, they exclude payments for drugs administered in hospitals and physicians’ offices—which account for about 30% of total prescription drug expenditures,30 $37.26 billion in 201931—causing us to substantially understate total government drug expenditures. Moreover, increases in prescription drug expenditures since 2019 have certainly increased government expenditures, although their effect on government’s share of expenditures is uncertain. Our tax subsidy estimates rely on simplifying assumptions regarding similarities between public- and private-sector workers with job-based coverage, e.g., that public and private sector employees are in similar tax brackets and live in states with similar average income tax rates. We also assume, as does the CBO,24 that reductions in drug prices would cause premium reductions for government purchasers of private coverage, and that government payers’ share of commercial premiums applies to drug purchases.

CONCLUSION

High drug costs affect all American taxpayers, not just patients who need medications. The Inflation Reduction Act, which imposed some Medicare drug price controls, may prove a useful first step, but broader measures are needed to make drugs affordable for all patients and for government budgets.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

Adam Gaffney, David U. Himmelstein, Steffie Woolhandler, and Danny McCormick are, or have served as, leaders of Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), a non-profit organization that favors coverage expansion through a single payer program; however, none of them receives any compensation from that group, although some of Dr. Gaffney’s travel on behalf of the organization was previously reimbursed by it. The spouse of Adam Gaffney is an employee of Treatment Action Group (TAG), a non-profit research and policy think tank focused on HIV, TB, and hepatitis C treatment. Elizabeth Schrier declares that she does not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kirzinger A, Montero A, Sparks G, Valdes I, Hamel L. Public opinion on prescription drugs and their prices. KFF August 21, 2023. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/public-opinion-on-prescription-drugs-and-their-prices/. Accessed 20 November 2023.

- 2.CDC. United States diabetes surveillance system. Total, adults with diabetes aged 18+ years, number in 1,000,000s. https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/diabetes/diabetesatlas-surveillance.html. Accessed on 15 February 2023.

- 3.Cubanski J, Neuman T, True S, Damico A. How much does Medicare spend on insulin. Kaiser Family Foundation. April 1, 2019. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-does-medicare-spend-on-insulin/. Accessed 22 August 2023.

- 4.Hernandez I, San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Gellad WF. Changes in list prices, net prices, and discounts for branded drugs in the US, 2007-2018. JAMA 2020;323(9):854-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaffney A, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Prevalence and correlates of patient rationing of insulin in the United States: a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(11):1623-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herkert D, Vijayakumar P, Luo J, et al. Cost-related insulin underuse among patients with diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):112-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jha AK, Aubert RE, Yao J, Teagarden JR, Epstein RS. Greater adherence to diabetes drugs is linked to less hospital use and could save nearly $5 billion annually. Health Affairs. 2012;31(8):1836-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Why insulin is so expensive in the U.S. – and what the Inflation Reduction Act does about it. Time, August 16, 2022. https://time.com/6206569/insulin-prices-inflation-reduction-act/. Accessed 15 July 2025.

- 9.Democrats passed a major climate, health, and tax bill. Here’s what’s in it. NPR, August 12, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/08/07/1116190180/democrats-are-set-to-pass-a-major-climate-health-and-tax-bill-heres-whats-in-it .Accessed 15 July 2025.

- 10.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: survey background. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp Accessed 23 August 2023. [PubMed]

- 11.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-213A: 2019 prescribed medicines, July 2021. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h213a/h213adoc.pdf. Accessed 23 August 2023.

- 12.Roehrig C. The impact of prescription drug rebates on health plans and consumers. Ann Arbor: Altarum, 2018. https://altarum.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-publication-files/Altarum-Prescription-Drug-Rebate-Report_April-2018.pdf. Accessed 22 August 2023.

- 13.Prescription drug rebates in Colorado 2017–2019. Center for Improving Value in Healthcare, August 2021. https://civhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Prescription-Drug-Rebates-Issue-Brief-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2024.

- 14.Agency for HealthCare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Insurance Component (IC) Data Tools. https://datatools.ahrq.gov/meps-ic?type=tab&tab=mepsich3pbs. Accessed 22 August 2023. [PubMed]

- 15.US Office of Personnel Management. Healthcare and Insurance: Cost of Insurance. https://www.opm.gov/healthcare-insurance/healthcare/reference-materials/reference/cost-of-insurance/. Accessed 22 August 2023.

- 16.Military health care Tricare: cost-sharing proposals would help offset increasing health care spending, but projected savings are likely overestimated. United States Government Accountability Office: GAO-07–647. May 2007. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-07-647.pdf. Accessed 16 September 2023.

- 17.Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Paying for national health insurance--and not getting it. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(4):88-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. The current and projected taxpayer shares of US health costs. Am J Public Health 2016;106(3):449-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of Management and Budget. Analytical perspectives: budget of the United States government. Various years. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/budget-united-states-government-analytical-perspectives-425?browse=2010s#577371. Accessed 17 February 2023.

- 20.US Census Bureau. Quarterly survey of state and local tax revenue (first quarter 2019 data release). https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/qtax.html (accessed February 17, 2023).

- 21.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditure Data. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata. Accessed 17 February 2023.

- 22.CMS. Health Insurance Exchanges 2019 open enrollment report. March 25, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/health-insurance-exchanges-2019-open-enrollment-report. Accessed 22 August 2023.

- 23.Drug spending. US Department of Health and Human Services: Office of the Inspector General, May 14, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/featured-topics/drug-spending/. Accessed 27 July 2024.

- 24.Congressional Budget Office. How CBO Estimated the Budgetary Impact of Key Prescription Drug Provisions in the 2022 Reconciliation Act. February 17, 2023. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58850. Accessed 24 July 2024.

- 25.Meiri A, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Wharam JF. Trends in insulin out-of-pocket costs and reimbursement price among US patients with private health insurance, 2006-2017. JAMA intern Med. 2020;180(7):1010-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.HHS Office of Inspector General. Drug Spending. May 14, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/featured-topics/drug-spending/. Accessed 24 July 2024.

- 27.Mulcahy AW, Schwam D, Edenfield N. Comparing insulin prices in the United States to other countries: results from a price index analysis. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA788-1.html. Accessed 23 August 2023.

- 28.IQVIA. Medicine spending and affordability in the U.S.: understanding patients’ costs for medicines. August 4, 2020. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/medicine-spending-and-affordability-in-the-us. Accessed 21 November 2023.

- 29.Sood, N, Ribero R, Martha R, Van Nuys K. The association between drug rebates and list prices. Leonard D Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. 2020. https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/the-association-between-drug-rebates-and-list-prices/. Accessed 1 Augus 2024.

- 30.Parasrampuria S, Murphy S. Trends in prescription drug spending, 2016–2021. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, September 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/88c547c976e915fc31fe2c6903ac0bc9/sdp-trends-prescription-drug-spending.pdf. Accessed 27 July 2024.

- 31.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part B spending by drug. https://data.cms.gov/summary-statistics-on-use-and-payments/medicare-medicaid-spending-by-drug/medicare-part-b-spending-by-drug. Accessed August 1, 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.