Abstract

Objectives:

Digital ulcers (DUs) are a major cause of pain and disability in systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients and remain a major treatment challenge. Our aim was to explore clinicians’ perspectives towards treatment initiation and escalation, akin to a ‘Treat to Target’ (T2T) strategy.

Methods:

SSc clinicians were invited to participate in an online survey.

Results:

A total of 173 responses (75% rheumatologists) were obtained from 33 countries. When initiating a change in oral drug therapy for SSc-DUs, most (80%) respondents would consider adding new medication to existing treatment, and 50% would increase existing treatment dose. Time to assess the impact of treatment change varied considerably, with around half (43.6%) waiting 1 month. Endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors and prostanoids were considered most efficacious for DU prevention, with good perceived efficacy from calcium channel blockers and moderate benefit from anti-platelet agents and immunosuppression. Side effects (e.g. headache and peripheral oedema) are perceived to be a significant issue with oral vasodilatory/vasoactive therapies in many patients. The highest rated T2T targets were (1) complete absence of new/recurrent DUs (63%), (2) reduction >50% in the number of DU recurrence (52%) and (3) reduction in DU healing time (37%) and reduction in DU pain >50% (37%). The most frequent reasons for hospitalisation were to administer intravenous treatment (91%) and DU complications (87%). Surgery is reserved for the threatened digit (e.g. gangrene), underlying calcinosis and failure of medical therapy.

Conclusion:

Significant heterogeneity currently exists concerning treatment initiation and escalation for SSc-DUs, potentially amenable to a T2T strategy.

Keywords: Digital ulcers, systemic sclerosis, scleroderma, T2T, management, pharmacological, vascular, Raynaud’s

Significance and innovations

• There is significant heterogeneity in drug therapy initiation and escalation strategies used for SSc-DUs.

• Drug side effects are an important consideration in the therapeutic strategy for SSc-DUs.

• Clinicians can identify potential treatment targets for SSc-DUs of relevance to a future T2T strategy.

Introduction

Digital ulcers (DUs) are common in systemic sclerosis (SSc), with around 40%–50% of patients experiencing DUs throughout the course of their disease, and are associated with significant pain and disability.1 –5 Ulcers typically occur on the fingertips or overlying the bony prominences of the small joints of the hands but may also occur at other sites, including related to underlying calcinosis.4,6 Irrespective of location, SSc-DUs represent a significant societal burden including associated health care costs (e.g. need for hospitalisation and increased medication use) and loss of work productivity.7,8

Significant improvements in SSc-DU management have been achieved in recent years, both for ulcer prevention and healing, including a number of effective pharmacological drug therapies.9,10 However, despite optimal medical management DUs are still often challenging to treat, with long healing times, recurrent ulceration and poor tolerance of systemic vasodilation, all playing a role.4,6,7 Current treatment recommendations and guidelines have presented the relative positionings of different drug classes for SSc-DUs. Furthermore, there is no available guidance concerning drug initiation and escalation strategies to inform clinical practice. In order to optimise drug efficacy and/or tolerability, a key priority is to develop an approach to drug treatment initiation and/or dose titration and to determine the benefit conferred from sequential vs combination therapies. 11

Vascular disease plays a cardinal role in the complex pathogenesis of SSc. The existence of an unified ‘endovascular phenotype’ has been proposed, in which shared pathogenic mechanisms likely exist between different vascular beds. 12 In general, DUs are considered to have an ischaemic aetiology, although other aetiopathogenic drivers have been proposed at different ulcer locations. These include mechanical factors, for example, for those DUs overlying the small joints of the hands, or related to finger contractures, primarily arising from recurrent microtrauma at vulnerable sites and/or increased skin tension.4,13,14 Furthermore, the role of inflammation (of physiological importance in normal wound healing) has yet to be fully elucidated and is likely to be detrimental, if excessive.4,15 Thus, DUs might be considered as the external representation of the internal disease pathology.

Of note, many drug therapies used for the treatment of DU disease are also utilised for other digital (e.g. Raynaud’s phenomenon [RP]) and systemic (e.g. pulmonary arterial hypertension [PAH]) vasculopathic sequelae in SSc.9,16 Indeed, it is suspected by many clinicians that most of (if not all) vascular-acting therapies used for one specific indication are likely to also confer additional off-target benefit/s for other distant vascular manifestations of the disease. Furthermore, targeting shared vascular mechanisms could potentially be deployed judiciously as a putative form of systemic disease modification, for example, by reducing local tissue ischaemia that promotes deleterious tissue fibrosis.4,11,17,18

A Treat to Target (T2T) approach has revolutionised the management of many rheumatological conditions including rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and gout.19 –21 Over the past two decades a large number of clinical trials have demonstrated superior clinical outcomes from a T2T approach compared to standard clinical care in patients with RA.19 –21 T2T includes a number of essential components comprising target selection, how to assess the target, when to assess the target, choosing if and when to change the treatment and shared decision-making with the patient.19 –21

Against this background and extant knowledge deficit, our overarching aim was to understand clinicians perspectives concerning drug initiation and escalation strategies for SSc-DUs, including to inform the development of a future T2T strategy approach to management.

Materials and methods

Study design

A dedicated steering board consisting of clinicians with an interest in SSc, patient representation (IG) and methodological expertise (AA) was assembled to develop a bespoke targeted survey to explore clinician’s perspectives concerning treatment initiation and escalation strategies for SSc-DU. The questions were developed by the steering board through an iterative process including discussion concerning the wording and choice of options in answers.

Survey questions

The survey consisted of 17 questions (see Supplemental Material). The steering board developed a survey to explore clinicians’ perspectives and current and theoretical future T2T practices concerning treatment strategies for SSc-DU. The questions included clinician demographics, personal experiences on DU treatments, specific opinions about drug efficacy and side effects and surgical intervention.

Survey distribution and responses

Clinicians with an interest in SSc were invited to participate in our online survey. The link to the survey was widely distributed including (but not limited) through SSc clinician networks and users of social media (e.g. X). The survey was launched online on 31st October 2023 and kept open for 15 weeks. Participants gave their informed consent for using their anonymous responses before commencing the survey. Our survey did not require ethical approval as no identifiable information was collected. Consent was implied through voluntary participation, and respondents could discontinue at any point.

Statistical analysis

Data were imported from the survey platform into SPSS software. Both fully completed (n = 20) and partially completed (n = 153) surveys were analysed and reported as the number of evaluable responses per individual questions. Absolute and relative frequencies were calculated and depicted in tabular form. Data are reported as the number of responses to each question and presented as descriptive statistics. Where fewer evaluable responses were avaliable for specific questions, this is indicated within the text.

Results

Respondent demographics

Respondent demographics are presented in Table 1. A total of 173 responses (of which 153 were complete responses) from 33 countries was collected. The respondents were similarly distributed between both male (45%) and female (53%) sexes. There was widespread international uptake/representation with respondents being from Italy (29%), Australia (9%), Croatia (9%), UK (8%) and Spain (8%). Most respondents were rheumatologists (75%), followed by internal medicine specialists (14%). The remaining respondents were specialists in dermatology, allergology/clinical immunology, geriatrics, pulmonary hypertension experts and vascular medicine. Most respondents worked in a university hospital setting (89%), with equal proportions working in a general (non-university/teaching) hospital (8%) or private practice (11%), and with little representation from general practice (0.6%). There was a breadth of clinical experience, with the majority of respondents (87%) reporting at least 6 years of clinical practice, including around two-thirds (68%) with at least 11 years. Most respondents had a substantial SSc patient cohort under their care, with over two-thirds exceeding 50 patients: 51–100 (20%), 101–200 (18%) and >200 (32%).

Table 1.

Survey respondent demographics.

| Respondent (n = 173) demographics (n, %) | ||

| Sex | Male | 78 (45) |

| Female | 91 (53) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | |

| Prefer not to specify | 1 (1) | |

| Not answered | 1 (1) | |

| Country of practice a | Italy | 51 (29) |

| Australia | 15 (9) | |

| Croatia | 9 (9) | |

| Spain | 14 (8) | |

| UK | 14 (8) | |

| USA | 8 (5) | |

| France | 7 (4) | |

| Brazil | 5 (3) | |

| Germany | 5 (3) | |

| Netherlands | 5 (3) | |

| Portugal | 6 (3) | |

| Israel | 3 (2) | |

| Switzerland | 3 (2) | |

| Turkey | 3 (2) | |

| Years of practice | 0–5 years | 22 (13) |

| 6–10 years | 27 (16) | |

| 11–20 years | 56 (32) | |

| 21–30 years | 38 (22) | |

| >30 years | 25 (14) | |

| Not answered | 5(3) | |

| Type of hospital/work practice | University hospital | 150 (89) |

| General (non-university/teaching) hospital | 14 (8) | |

| General practitioner/family practice clinic | 1 (0.6) | |

| Private practice | 19 (11) | |

| Number of SSc patients under respondents care with SSc or CTD and SSc features | <25 | 23 (14) |

| 25–50 | 27 (16) | |

| 51–100 | 34 (20) | |

| 101–200 | 31 (18) | |

| >200 | 53 (32) | |

| Not answered | 0 (0) | |

CTD: connective tissue disease; SSc: systemic sclerosis; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America.

Data on countries contributing <1% of respondents are available as Supplementary Material.

Access to intravenous prostanoid therapy for DU

Only two-thirds (67.3%) of respondents (n = 153) reported the ability to provide outpatient-based intravenous prostanoid (e.g. iloprost, epoprostenol) therapy in their institution. There was significant geographical variation, being disproportionately more accessible in Europe (81.5%), compared to North and South America (4.8% and 1%, respectively), or Oceania and Asia (8.7% and 3.8%, respectively).

Pharmacological treatment approach for SSc-DU

Respondents were asked about their general approach when dealing with a change in oral drug therapy for SSc-DU. Most frequently (n = 163, 80%), respondents would consider adding a new medication to the existing treatment, and half (n = 163, 50%) would consider increasing the existing drug dose. Respondents seldom considered stopping existing and starting new treatment (n = 163, 20%).

We also asked respondents how long they would typically wait to assess treatment response or to consider further treatment for a typical (uncomplicated) DU. The majority (n = 163, 85.3%) reported that they would wait at least two weeks or longer, whereas around two-thirds of respondents (n = 163, 61.4%) reported waiting between 1 (n = 163, 43.6%) and 3 (n = 163, 17.8%) months.

Drug treatment efficacy for preventing DU

Based on respondents’ clinical experience, we enquired about the perceived efficacy of different drug classes/mechanisms of action for preventing DU. Responses were obtained using a numerical scale to collect respondents’ sentiments, where 0 indicated being ‘not effective’ and 10 as ‘very effective’. Respondents could also choose not to score these if they deemed that they had no relevant experience to inform their responses. Full description of the perceived efficacy of the individual drug classes/mechanisms by respondents is available as Supplementary Material.

Out of a total of 157 responses and based on the mean (SD) scores, endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs) (7.8 [2.9]), prostanoids (7.68 [2.9]) and phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors (PDE5i) (7 [2.3]) were rated as the most efficacious drug treatments for DU prevention. Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) were deemed to have moderate treatment efficacy (5.5 [2.2]). Anti-platelets were deemed to have mild to moderate efficacy for DU prevention (4.59 [2.5]). Alpha blockers, drugs affecting the renin-angiotensin system and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were perceived by respondents to have limited preventive efficacy for DUs (all mean values below 4.0). However, a significant proportion of respondents had no experience with these drugs to inform their opinion (alpha-blockers: 43%, SSRIs: 28% and drugs affecting the renin-angiotensin system: 11%).

Most respondents (n = 157) had relevant experience to inform their responses concerning immunosuppression for DU prevention. In more detail, 89% and 84% of respondents had experience with conventional synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) and biologic (b) DMARDs, respectively, and rated them as having mild to moderate efficacy (3.5 [3.2] and 4.1 [3.2] for csDMARDs and bDMARDs, respectively).

Side effects associated with oral drug treatment for DU

Based upon their experience, respondents were asked to indicate the frequency (‘never’, ‘seldom’, ‘some of the time’, ‘most of the time’) of side effects associated with oral vasodilatory/vasoactive therapy for SSc-DUs; responses are presented in Table 2. Headache was considered to be the most frequent side effect associated with treatment, whereas lower extremity oedema, light-headedness and nausea were less frequently observed. Fatigue was the least frequently observed side effect.

Table 2.

Side effects associated with the use of oral vasodilatory/vasoactive drug therapy for SSc-DU.

| Side effect | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | Never | 1 (0.6%) |

| Seldom | 27 (17 %) | |

| Some of the time | 99 (63%) | |

| Most of the time | 30 (19%) | |

| Nausea | Never | 17 (11%) |

| Seldom | 92 (59%) | |

| Some of the time | 47 (30%) | |

| Most of the time | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Lightheadedness | Never | 15 (10%) |

| Seldom | 67 (43%) | |

| Some of the time | 65(41%) | |

| Most of the time | 10 (6%) | |

| Fatigue | Never | 30 (19%) |

| Seldom | 91 (58%) | |

| Some of the time | 36 (23%) | |

| Most of the time | 0 (0%) | |

| Lower extremity oedema | Never | 3 (2%) |

| Seldom | 57 (36%) | |

| Some of the time | 86 (55%) | |

| Most of the time | 11 (7%) | |

Potential targets for a DU T2T strategy

Considering a hypothetical future T2T strategy, we asked respondents to choose their ‘top 3’ treatment targets for SSc-DU (). These were the: (1) complete absence of new/recurrent/DUs (63%), (2) reduction >50% in the number of DU recurrence (52%) and (3) reduction in DU healing time (37%) or reduction in DU pain >50% (37%).

Figure 1.

Targets for a future DU T2T strategy. Respondents indicated on a binary scale their preference (i.e. whether to include or exclude) potential target/s for a hypothetical future T2T strategy for SSc-DUs.

Data are presented as the percentage of respondents who considered whether an item could be a potential treatment target.

Other targets deemed important by respondents were: prevention of DU complications (e.g. infection and/or gangrene) (30%), patient reported outcome (e.g. DU Visual Analogic Scale VAS) (25%), reduction in the burden of RP (e.g. leading to improved digital perfusion) (17%), reduced DU size (e.g. to visual inspection) (12%) and the prevention of other SSc-associated vascular complications (e.g. PAH) (11%).

Clinician-reported outcome (e.g. DU VAS) (6%), reduction < 50% of the number of DU recurrence (6%) and reduction in DU pain < 50% (3%), were the least preferred T2T targets.

Outpatient drug management strategies for DUs

For DU managed in the community (i.e. not requiring hospitalisation), we asked respondents whether they typically modified the existing dose of oral vasodilatory/vasoactive therapies. The majority of respondents proactively increased either ‘always’ (41.2%) or ‘sometimes’ (56.9%) the existing dose of oral vasodilatory/vasoactive therapies.

Likewise, after a DU episode, the majority of respondents (n = 153) ‘always’ (55.6%) or ‘sometimes’ (41.8%) reviewed the patient’s ongoing (chronic) therapeutic strategy.

We also asked respondents if they would modify patients’ pharmacological treatment (e.g. temporary dose reduction) for SSc-associated vasculopathy during the warmer months and they confirmed to do so ‘sometimes’ (74%) or ‘always’ (16%).

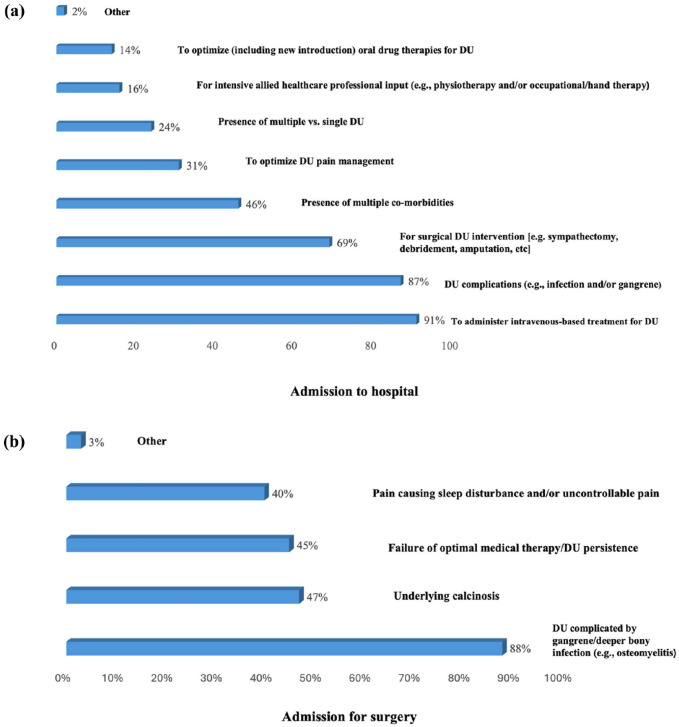

Factors influencing hospitalisation to treat DUs

We also explored the factors that influence respondents (n = 153) decision to admit patients to the hospital to treat DU (Figure 2a). The most frequents reason were to administer intravenous-based treatment for DU (91%), DU complications (e.g. infection and/or gangrene) (87%) and for surgical DU intervention (e.g. sympathectomy, debridement, amputation, etc) (69%).

Figure 2.

Factors influencing clinicians decision-making concerning proposal for admission to hospital (a) and surgery (b) to treat SSc-DUs.

Less frequently reported items were presence of multiple co-morbidities (46%), to optimise DU pain management (30%), presence of multiple vs single DU (24%) and to optimise (including new introduction) oral drug therapies for DU (14%).

DU surgery

We also enquired about the factors which influence clinicians’ (n = 153) decision to propose surgical intervention for SSc-DUs (Figure 2b). The most common reason was DU complicated by gangrene or deeper bony infection (e.g. osteomyelitis) (87.6%). Other important reasons, considered by around half of respondents, were underlying calcinosis (47%), failure of optimal medical therapy or DU persistence (45%) and pain causing sleep disturbance and/or uncontrollable pain (40%).

DU inflammation

The majority (87.6%) of respondents (n = 153) acknowledged that they recognise signs of ulcer inflammation without obvious evidence of infection.

Discussion

Our data confirm that there is significant heterogeneity in current clinical practice in the management of patients with SSc-DUs, including both drug initiation and escalation strategies. We have also benchmarked the perceived efficacy and tolerability of our currently available therapies for DU prevention by clinicians. Furthermore, our study provides novel insights into clinician’s decision-making concerning the management of SSc-DUs, including outpatient-based strategies and the reasoning concerning acute treatment intensification. We have also highlighted the presence of significant international inequity in the provision to administer intravenous prostanoid therapy for SSc-DUs and also questioned the role of inflammation in ulcer pathogenesis.

A key finding of our study is that clinicians can identify hypothetical future T2T targets for SSc-DUs. The ‘top 3’ treatment targets as ranked by respondents were the: (1) complete absence of new/recurrent/DUs (63%), (2) reduction >50% in the number of DU recurrence (52%) and (3) reduction in DU healing time (37%) and reduction in DU pain >50% (37%). While pain has been previously reported by the patients as the principal reason for considering change in treatment for DU. 22 Furthermore, prevention of DU complications (e.g. gangrene) was also deemed of importance (30%). Patient-reported outcomes were prioritised over the clinician-reported ones (e.g. DU patient- and clinician-reported VAS was endorsed by 25% and 6%, respectively), and only minimal insight was considered to be gained from reduction in DU size alone (e.g. to visual inspection, 6%). Our data are in keeping with the ongoing work by the OMERACT Vascular Disease in SSc Working Group which aims to develop a core set of outcome measure domains to study SSc-DUs (and SSc-RP separately).23 –25 As such, a recent scoping review was undertaken by the group to evaluate the outcome domains used to assess SSc-DUs, of which 40 studies met the predetermined eligibility criteria. 25 Around half assessed the DU count/number (n = 23) and/or improvement in DUs (n = 20). Functional assessment was also assessed in one-quarter (n = 10) of studies. Lesser utilised domains were DU complications (n = 7), DU pain (n = 6), health-related quality of life (n = 4) and global DU assessment (n = 2). Furthermore, objective examination of DU microcirculation/pathophysiology (n = 4) and histopathology (n = 1) was only undertaken in several studies.

Concerning the targeting of a unified endovascular phenotype in SSc, our study highlights how most clinicians believe that treatment for SSc-DUs should also explicitly aim to reduce the global burden of digital ischaemia (e.g. SSc-RP, 17% of respondents) and prevent other SSc-associated vascular complications (e.g. PAH, 11% of respondents). These data are also supported from the patients’ perspective, as emerged from the PAtient Survey of experiences of RAynaud’s Phenomenon (PASRAP) analysis. 26 In this study, patients (n = 747) ranked (out of 13 items) the emergence of new DU, and benefit to internal organ complications, among the top-5 factors when considering treatment escalation for SSc-RP. 26

Clinicians utilise different management approaches when considering choice of treatment and drug escalation strategies for SSc-DUs. When initiating a change in oral drug therapy for SSc-DU, most (80%) clinicians consider either adding new to existing treatment or increasing the existing dose (50%) and less frequently favour substituting existing with new drug treatment (20%). These findings can broadly be conceptually compared with that of the previously described PASRAP study concerning treatment escalation for SSc-RP. 26 In PASRAP, around half (53%) of the studied patients would consider adding new (in combination with exisiting treatment), and unlike the clinicians who participated to our survey, patients themselves preferred drug substitution (41%) compared to increasing the current dose (29%).

Our survey also provides novel insights into clinicians’ perspectives on the effectiveness and side effects of oral drug therapies for SSc-DU in the contemporary period. ERAs, PDE5i and prostanoids are considered the most effective drug therapies for DU prevention, and CCBs were deemed to have moderate efficacy. Drugs targeting the renin-angiotensin system and SSRIs were perceived to have limited efficacy, although many clinicians had limited practical experience with their use for DU treatment. Anti-platelet therapies were also perceived to have mild to moderate treatment efficacy. Although historically there was a dearth of robust data, recently a recurrence in research interest has led to more supportive evidence to encourage their use for this indication.10,27 Broad approaches to immunosuppression (both csDMARD and bDMARD) therapies were also deemed to have moderate effect on DU prevention. Indeed, some authors have reported their positive treatment experience with various immunosuppressive therapies for DU healing. However, to date, there have been no dedicated placebo-controlled RCTs of immunosuppressive therapies in SSc where DUs have been studied as a primary endpoint. 10 Side effects associated with oral vasodilatory drug treatment for SSc-DU are common. Headaches, in particular, are considered almost universal. Lower limb extremity oedema, light-headedness and nausea, also frequently complicate such treatment. Future studies should seek to examine the severity of side effects attributed to treatment, and how this impacts on the onward therapeutic strategy adopted by clinicians.

Important practical insights were gained concerning the ‘real world’ outpatient management strategies for SSc-DUs. For those DUs managed in the community (i.e. not requiring hospitalisation), the majority (98%) of the clinicians would either ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ modify existing vascular treatment/s for DU. Furthermore, after episodic DU, the majority (97.4 %) of respondents either ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ actively review the patient’s ongoing (chronic) therapeutic strategy. Finally, most respondents (90%) either ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’ modify patients’ pharmacological treatment (e.g. temporary dose reduction) for SSc-associated vasculopathy during the warmer months. Taken together, incident DU represents a major milestone in the patient’s disease course and requires careful consideration of the therapeutic strategy. Active management by clinicians and longer-term consideration of preventive pharmacological strategies are critical to optimise outcomes.

Our data also provide a unique understanding of clinicians’ behaviours concerning the management of active digital ulceration and the role for surgical intervention. Here we determined that the most frequent reasons for hospitalisation for DU were to administer intravenous-based treatment and manage ulcer complications (e.g. infection and/or gangrene) and for surgical intervention (e.g. sympathectomy, debridement, amputation, etc). Other important (but less prioritised) factors were the presence of multiple co-morbidities, to optimise DU pain management, the presence of multiple DUs and to optimise (including new introductions) of oral drug therapies for DU. Surgical intervention is actively considered by clinicians, particularly where DUs are complicated by gangrene or deeper bony infection (e.g. osteomyelitis). Other considerations related to surgery included the presence of underlying calcinosis, failure of optimal medical therapy or DU persistence and uncontrollable pain and/or pain causing sleep disturbance.

Our survey confirmed significant international inequity in clinicians’ current ability to administer intravenous prostanoid therapy, specifically for SSc-DUs, within their institution. Overall, only two-thirds reported the ability to provide intravenous prostanoid therapy, and accessibility was particularly disproportionate in Europe (>80%), compared to other global regions (all <10%). The reasoning behind this disparity in access is likely multifactorial including (but not limited to) the differences in healthcare systems including drug availability and reimbursement mechanisms. For example, iloprost is currently only available in Europe and not the United States.28,29

Our study benefitted from a large number of evaluable responses and a robust study design led by an international steering board. We developed an easy-to-use interface to collect responses and conducted extensive pre-distribution testing. The survey was widely distributed internationally among SSc clinician networks and social media; however, there could have been a potential for responder bias, particularly because our survey was conducted only in the English language. Furthermore, in many countries, the response rate was less than 1%, and this represents a limitation of the data analysis, although our use of social media and SSc clinician networks likely ensured broad visibility and dissemination to important stakeholder group. Another limitation is that many respondents had a relatively limited number of patients with SSc under their care to inform their responses. We are unaware of any important differences between geographical regions (and this was not the intention of our survey), and our intention was to understand clinician decision-making. We also focussed on currently avaliable oral drug therapies and therapeutic strategies used for SSc-DUs, and it is possible that clinicians may adopt different treatment strategies based on the perceived aetiology of ulcers. The lower perceived efficacy of certain drug therapies (e.g. alpha-blockers, SSRIs and drugs affecting the renin-angiotensin system) may also partially be explained by the lower proportion of respondents who had relevant experience of using these drug treatments for SSc-DUs. It is important to again recognise the essential role for local tissue management, including ulcer debridement, which we did not specifically explore in our present survey.15,30,31 Pragmatically, we examined clinicians’ opinions on a broad range of likely future DU T2T outcome measures. However, we recognise that other novel outcome measures (including of DU disease severity) are currently being actively explored including but not limited to DU ultrasound (e.g. to assess ulcer surface dimensions and volume) and ulcer photography.32 –37

In conclusion, there is significant heterogeneity concerning clinicians’ treatment initiation and escalation for SSc-DUs. Clinicians use different therapeutic approaches for incident DU and also consider the longer-term pharmacological preventive strategy. Our study provides novel insights into the perceived efficacy and side effects of drug therapies used for DU and a preliminary assessment of potential treatment targets relevant to a future T2T strategy. There is significant international inequity in access to intravenous-based iloprost for SSc-DUs. Our study also exposes a current knowledge gap for the role of inflammation (without overt infection) in the pathogenesis of SSc-DU and whether immunosuppressive therapy is of benefit. Further research is indicated to explore whether a T2T strategy could be developed to optimise the therapeutic approaches for DUs and whether this could also confer broader benefits to systemic vasculopathy in SSc.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the World Scleroderma Foundation Digital Ulcer ad hoc committee and we thank clinicians for their participation to the survey. We also extend thanks to SSc clinician networks and users of social media for their dissemination of the survey.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: MH is Chair of a Data Safety Monitoring Board: SHED SSc–SHarp dEbridement of Digital ulcers in Systemic Sclerosis: a multi-centre Randomised Controlled Trial feasibility study (REC reference: 21/YH/0278) and receives research funding and speaker fees from Janssen, outside of the submitted work. None of the other authors report any relevant conflicts of interest.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Authors’ note: The Editor/Editorial Board Member of JSRD is an author of this paper; therefore, the peer review process was managed by alternative members of the Board, and the submitting Editor/Board member had no involvement in the decision-making process.

Data availability statement: The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

ORCID iDs: Giulia Campanaro  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6269-2944

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6269-2944

Giulia Bandini  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2076-7319

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2076-7319

Ilaria Galetti  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9595-7582

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9595-7582

Michael Hughes  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3361-4909

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3361-4909

References

- 1. Hughes M, Herrick AL. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017; 56(1): 14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khimdas S, Harding S, Bonner A, et al. Associations with digital ulcers in a large cohort of systemic sclerosis: results from the Canadian scleroderma research group registry. Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63(1): 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steen V, Denton CP, Pope JE, et al. Digital ulcers: overt vascular disease in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2006; 48: 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hughes M, Allanore Y, Chung L, et al. Raynaud phenomenon and digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Rheumatology 2020; 16(4): 208–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hughes M, Pauling JP, Jones J, et al. Patient experiences of digital ulcer development and evolution in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2020; 59: 2156–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amanzi L, Braschi F, Fiori G, et al. Digital ulcers in scleroderma: staging, characteristics and sub-setting through observation of 1614 digital lesions. Rheumatology 2010; 49(7): 1374–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matucci-Cerinic M, Krieg T, Guillevin L, et al. Elucidating the burden of recurrent and chronic digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: long-term results from the DUO registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75(10): 1770–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morrisroe K, Stevens W, Sahhar J, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: their epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and associated clinical and economic burden. Arthritis Res Ther 2019; 21: 299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hughes M, Ong VH, Anderson ME, et al. Consensus best practice pathway of the UK scleroderma study group: digital vasculopathy in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2015; 54(11): 2015–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ross L, Maltez N, Hughes M, et al. Systemic pharmacological treatment of digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Rheumatology 2023; 62(12): 3785–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hughes M, Khanna D, Pauling JD. Drug initiation and escalation strategies of vasodilator therapies for Raynaud’s phenomenon: can we treat to target? Rheumatology 2020; 59(3): 464–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matucci-Cerinic M, Kahaleh B, Wigley FM. Review: evidence that systemic sclerosis is a vascular disease. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65(8): 1953–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hachulla E, Clerson P, Launay D, et al. Natural history of ischemic digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: single-center retrospective longitudinal study. J Rheumatol 2007; 34(12): 2423–2430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hughes M, Murray A, Denton CP, et al. Should all digital ulcers be included in future clinical trials of systemic sclerosis-related digital vasculopathy. Med Hypotheses 2018; 116: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughes M, Alcacer-Pitarch B, Allanore Y, et al. Digital ulcers: should debridement be a standard of care in systemic sclerosis. Lancet Rheumatol 2020; 2(5): e302–e307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2022; 43(38): 3618–3731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hughes M, Di Donato S, Gjeloshi K, et al. MRI Digital Artery Volume Index (DAVIX) as a surrogate outcome measure of digital ulcer disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2023; 5(10): e611–e621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hughes M, Huang S, Pauling JD, et al. The clinical relevance of Raynaud’s phenomenon symptom characteristics in systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol 2022; 41(10): 3049–3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Solomon DH, Bitton A, Katz JN, et al. Review: treat to target in rheumatoid arthritis: fact, fiction, or hypothesis? Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66(4): 775–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kiltz U, Smolen J, Bardin T, et al. Treat-to-target (T2T) recommendations for gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(4): 632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Vollenhoven R. Treat-to-target in rheumatoid arthritis – are we there yet. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019; 15(3): 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bandini G, Alunno A, Alcacer-Pitarch B, et al. Patient’s unmet needs and treatment preferences concerning digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2024; 64: 1277–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hughes M, Maltez N, Brown E, et al. Domain reporting in systemic sclerosis-related digital ulcers: an OMERACT scoping review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2023; 61: 152220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maltez N, Hughes M, Brown E, et al. Domain reporting in systemic sclerosis-related Raynaud’s phenomenon: an OMERACT scoping review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2023; 61: 152208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maltez N, Hughes M, Brown E, et al. Developing a core set of outcome measure domains to study Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: report from OMERACT 2020. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021; 51(3): 640–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hughes M, Huang S, Pauling JD, et al. Factors influencing patient decision-making concerning treatment escalation in Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res 2021; 73(12): 1845–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garaiman A, Steigmiller K, Gebhard C, et al. Use of platelet inhibitors for digital ulcers related to systemic sclerosis: EUSTAR study on derivation and validation of the DU-VASC model. Rheumatology 2023; 62: 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pauling JD, Hughes M, Pope JE. Raynaud’s phenomenon-an update on diagnosis, classification and management. Clin Rheumatol 2019; 38(12): 3317–3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ramahi A, Hughes M, Khanna D. Practical management of Raynaud’s phenomenon-a primer for practicing physicians. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2022; 34(4): 235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hughes M, Alcacer-Pitarch B, Gheorghiu AM, et al. Digital ulcer debridement in systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Clin Rheumatol 2020; 39(3): 805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Campochiaro C, Suliman YA, Hughes M, et al. Non-surgical local treatments of digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2023; 63: 152267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hughes M, Moore T, Manning J, et al. A pilot study using high-frequency ultrasound to measure digital ulcers: a possible outcome measure in systemic sclerosis clinical trials? Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017; 35(Suppl. 106)(4): 218–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Suliman YA, Kafaja S, Fitzgerald J, et al. Ultrasound characterization of cutaneous ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol 2018; 37(6): 1555–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Simpson V, Hughes M, Wilkinson J, et al. Quantifying digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: reliability of computer-assisted planimetry in measuring lesion size. Arthritis Care Res 2018; 70(3): 486–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hughes M, Bruni C, Cuomo G, et al. The role of ultrasound in systemic sclerosis: on the cutting edge to foster clinical and research advancement. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2021; 6(2): 123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Suliman YA, Bruni C, Hughes M, et al. Ultrasonographic imaging of systemic sclerosis digital ulcers: a systematic literature review and validation steps. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021; 51(2): 425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Davison AK, Dinsdale G, New P, et al. Feasibility study of mobile phone photography as a possible outcome measure of systemic sclerosis-related digital lesions. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2022; 6(3): rkac105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]