Abstract

Cross-coupling reactions between short-lifetime radicals are challenging reactions in organic chemistry. Here, we report the development of an N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-mediated radical coupling reaction based on the catalytic machinery of thiamine- and flavin-dependent enzymes. Through a series of enzyme screenings, we found that acetolactate synthase from Thermobispora bispora (TbALS) and its engineered variants exhibit promising catalytic activity toward abiotic radical acylation reactions of α-bromo carbonyl compounds. Notably, the TbALS variant has higher catalytic activity for small nonaromatic substrates despite forming less stable radical intermediates. Furthermore, the catalytic system of TbALS can be applied to photocatalytic reactions utilizing the photoredox properties of FAD. Nonbenzylic alkyl radicals generated from N-acyloxyphthalimides are efficiently converted into the corresponding dialkyl ketones under irradiation of a blue LED. These findings highlight the utility of thiamine- and flavin-dependent enzymes for achieving selective cross-coupling reactions of short-lifetime radicals.

Introduction

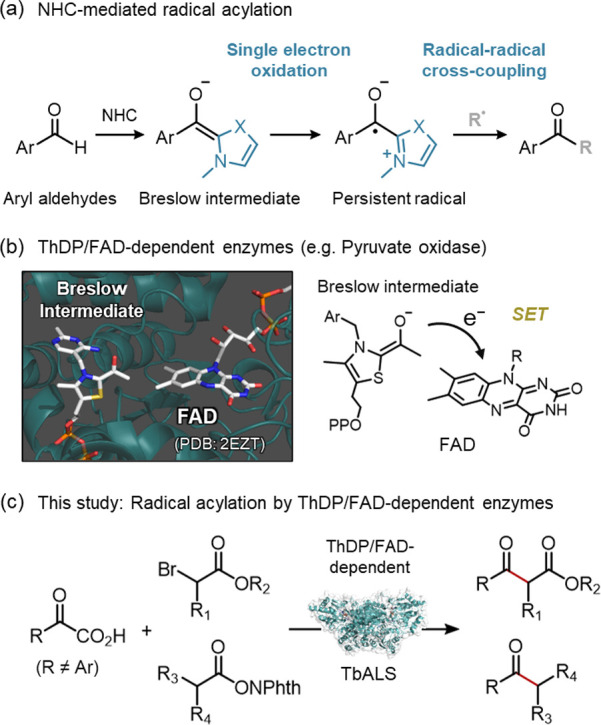

Radical–radical cross-coupling reactions are powerful synthetic tools that can provide straightforward access to a wide variety of chemical bonds.1 In particular, N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-mediated radical catalysis has been one of the most successful strategies in these cross-coupling reactions.2−5 NHC generates persistent radicals through one-electron oxidation of the Breslow intermediate (Figure 1a), and the subsequent cross-coupling reaction proceeds selectively under the control of the persistent radical effect.6 Over the past decade, a number of excellent reaction systems have been explored to take advantage of the unique reactivity of NHC-derived persistent radicals. Examples include the acylation of organic halides,7−11 redox-active esters,12−14 and other radical precursors.15−17 In spite of these remarkable advances, the efficiency of NHC-mediated radical catalysis is still limited by the lifetime of the radical intermediates generated in situ. In many cases, the scope of the reaction is limited to tailored substrates, for example, aryl aldehydes that generate stabilized radicals at benzylic positions, with a few exceptions.4,14

Figure 1.

(a) General catalytic mode of NHC-mediated radical acylation reactions. (b) Single electron oxidation of Breslow intermediate promoted by ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes. (c) Radical acylation reactions catalyzed by the ThDP/FAD-dependent enzyme TbALS investigated in this study.

On the other hand, enzymes found in nature possess excellent catalytic systems that manage the reactivity of short-lifetime radicals.18−28 The active sites of the enzymes can precisely control the orientation of the short-lifetime radicals, thereby enabling selective radical couplings beyond the conventional diffusion-dominant rules of organic chemistry.29 In this study, we focused on a class of enzymes which have thiamine diphosphate (ThDP) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactors within their active site (Figure 1b).30,31 Some of these ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes, such as pyruvate oxidase, are known to promote two successive single electron transfers (SETs) between FAD and ThDP-derived Breslow intermediates.32 Inspired by this SET mechanism of ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes, we envisioned applying this enzyme machinery to abiotic NHC radical catalysis (Figures 1c and S1). Very recently, Huang’s group and Yang’s group have independently reported the development of outstanding catalytic platforms by combining an externally added organic photocatalyst with a “ThDP”-dependent enzyme.33,34 In contrast to these catalytic platforms generating one transient radical in a solution, the “ThDP/FAD”-dependent enzymes are expected to generate two radicals in the same active site with a defined orientation (Figures S1 and S2). We posited that this property of the ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes provides a significant advantage in controlling the reactivity of short-lifetime radicals in NHC radical catalysis.

Results and Discussion

Based on the hypothesis above, we first screened a panel of ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes to identify a promising enzyme capable of promoting targeted NHC radical catalysis. Based on information from protein databases (PDB and UniProt), 14 ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes, including cyclohexane-1,2-dione hydrolase,35−37 pyruvate oxidase,32,38−40 pyruvate dehydrogenase,41,42 glyoxylate carboligase,43,44 and acetolactate synthase (ALS)45−48 were selected for the radical acylation reaction of ethyl 2-bromopropionate (2a) with pyruvic acid (1a) as an acyl donor (Figures 2a, S3, and Table S1).10 Surprisingly, the desired acylation activity was identified in acetolactate synthase Q47SB8, A0A919QSP1, and D6Y6A4 originating from thermophilic actinomycetes, even though the reaction proceeds through less-stable acetyl radical equivalents and nonbenzylic carbon-centered radicals (Figure 2b). All three enzymes are located on the same branch of the phylogenetic tree and exhibit significantly higher acylation activities relative to the other ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes. In particular, acetolactate synthase D6Y6A4 from Thermobispora bispora (TbALS) has the highest activity and provides the desired acylated product 3aa in 2.4% yield (Figures S4 and S5). The native reaction catalyzed by acetolactate synthase is a nonredox benzoin-type condensation reaction between two molecules of pyruvic acid (Figure S6).47 Structural similarity between the substrates might be one of the reasons for the promiscuous activity of ALS toward the acylation reaction of α-bromoester 2a.

Figure 2.

Screening of ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes for the radical acetylation of 2a with 1a. (a) Phylogenetic tree of the enzymes selected for the screening. Each enzyme is classified as one of four groups that are highlighted using different colors. (b) Screening results for the radical acylation of α-bromoester. Reaction conditions: Enzyme (ca. 6 μM), 1a (10 mM), 2a (1.0 mM), ThDP (0.10 mM), MgSO4 (1.0 mM) in MOPS buffer (100 mM MOPS, pH = 7.5), 25 °C for 24 h under N2. Yield of 3aa was determined based on substrate 2a by GC-MS.

Interestingly, ALSs, including TbALS, which are capable of promoting the acylation reaction, were found to exhibit a characteristic UV–vis absorption at 500–600 nm that is not usually observed for other ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes (Figure S7a,b). Furthermore, during the enzyme screening process, we unintentionally identified a D283Y variant of TbALS with enhanced UV–vis absorption at 500–600 nm (Figure S7c,d). The E. coli cells expressing the D283Y variant have a slightly orangish color, whereas the cells expressing wild-type TbALS are yellow (Figure S8). The results of the molecular dynamics simulation (Figures S9–S11) suggest that the Tyr283 residue incorporated in the active site interacts with the N1 atom of the FAD isoalloxazine ring (Figures S12 and S13). The absorption at 500–600 nm may be due to the formation of an electrostatic complex between FAD and neighboring amino acid residues, particularly the Tyr283 residue,49,50 which is also supported by TD-DFT calculations (Figure S14). Moreover, the D283Y mutation also contributes to the acylation activity of TbALS. The yield of 3aa was found to be increased by 3.5% when TbALS(D283Y) is employed as the catalyst. As commonly observed in the electron transfer systems of natural flavoproteins,51−53 the preferential interaction of Tyr residue may promote the SET process in the catalytic cycle by stabilizing the flavin semiquinone intermediate (Figures S1 and S2). In contrast, the TbALS(A30W/D283Y) variant, which is characterized by loss of the absorption band at 500–600 nm, exhibits negligible activity, vide infra (Figures 3b and S15). These results indicate the importance of the electronic state of the FAD cofactor for NHC radical catalysis.

Figure 3.

(a) Substrate docking model and schematic illustration for the rational engineering of TbALS(D283Y). Substrate 2a is shown as a green stick. R285 and amino acid residues subjected to site-directed mutagenesis are highlighted as blue sticks, in which protein chains A and B are also indicated in parentheses. (b) Screening results for the TbALS(D283Y) variants in the first round of engineering. Yields of 3aa are shown as a blue or gray bar. The relative binding free energy changes (ΔΔG°bind) are plotted as black diamonds. (c) Summary of the rational engineering of TbALS variants. Reaction conditions: TbALS variants (ca. 6 μM), 1a (10 mM), 2a (1.0 mM), ThDP (0.10 mM), and MgSO4 (1.0 mM) in MOPS buffer (100 mM MOPS, pH = 7.5), 25 °C, 24 h under N2. Yield of 3aa was determined based on substrate 2a by GC-MS.

Next, rational engineering of TbALS(D283Y) based on a docking simulation approach was carried out to further improve the radical acylation activity. As described above, native ALS catalyzes the condensation reaction between two molecules of pyruvic acid (1a) (Figure S6). To change this substrate specificity of ALS, a computer-aided protein design was performed using a substrate-docked enzyme model (Figure 3a). In this model, the first substrate 1a was placed in a complex with ThDP in the form of 2-α-hydroxyethylthiamine diphosphate, the so-called Breslow intermediate, which has been reported as crystallographic data for acetolactate synthase.54 The second substrate 2a was then placed in the substrate binding cavity of TbALS to evaluate the binding free energy (ΔG°bind) of the substrate 2a using the molecular operating environment (MOE) software.55 Interestingly, high-scored configurations indicated formation of a hydrogen bond between the carbonyl group of 2a and the Arg285 residue, which is conserved in the native reaction of ALS (Figure 3a).56 Substitution of the Arg285 residue results in a significant decrease in the activity of TbALS(D283Y), suggesting that Arg285 plays an important role in the target acylation reaction (Figure S16).

Subsequently, we conducted in silico mutation analysis using the obtained model. A series of single-substitution variants was generated in silico, and the effect of the mutations was evaluated based on relative binding free energy changes (ΔΔG°bind) between the in silico-generated single-substitution variant and the parent TbALS variant. In the first round of engineering, we tested 14 single mutants of TbALS(D283Y), which gave lower ΔΔG°bind scores according to the in silico analyses (Figure 3b and Table S2). Notably, mutations at the V104 position, located in the regulatory Q-loop region of ALS,57,58 were found to clearly increase the activity of TbALS(D283Y). In particular, TbALS(V104R/D283Y) provided product 3aa in the highest yield, which is generally consistent with the calculation result of the ΔΔG°bind scores (Figure 3b). In addition, the TbALS(V104K/D283Y) variant, where a similar positive amino acid residue was incorporated into the Q-loop region, also exhibits enhanced catalytic activity. In view of these results, we conducted a second round of engineering using these two variants as templates. As a result, the W484H variant of TbALS(V104K/D283Y) (hereinafter referred to as TbALSKYH) was found to be the optimal catalyst (Figures 3c, S17, Tables S3, and S4). Compared to the wild-type, TbALSKYH exhibited an 8-fold improvement in total turnover number (TTN) and afforded 3aa in 20% yield (32 TTN). Considering the enzyme precipitation observed during the course of the reaction, enzyme denaturation may be the main factor determining the yield of this acylation reaction.

TbALSKYH provided the desired acylated product 3aa in 87% yield under high catalyst loading conditions to manage enzyme inactivation (Table 1, entry 1). Although this product was obtained as a racemic mixture due to rapid keto–enol tautomerization in aqueous media, α-bromoester 2a was nicely converted into the acylated product 3aa without forming hydrogenated byproducts, such as ethyl propionate (4a), which is expected to be produced via two-electron redox cycle of FAD (Figures S18–S20).59,60 Increasing the concentration of 2a did not significantly decrease the yields of 3aa and improved the TTN for the reaction (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). Negative control experiments performed in the absence of TbALSKYH or using only FAD as a catalyst afforded little or no product, indicating the crucial role of the enzyme active site (Table 1, entries 4 and 5). The use of acetaldehyde as an acyl donor leads to a reduced yield of product 3aa, suggesting incompatibility of aldehydes with our biocatalytic system (Table 1, entry 6). Notably, the presence of TEMPOL or dioxygen does not significantly interfere with the catalysis of TbALSKYH (Table 1, entries 7 and 8). The well-organized TbALSKYH active site may contribute to preventing the diffusion of reactive radical intermediates and inhibiting the entry of the radical trapping/quenching reagents. Alternatively, the formation of the radical intermediates was confirmed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and UV–vis measurements. In the low-temperature EPR measurements, EPR signals were detected only under the standard reaction conditions, where the substrates were added to the TbALSKYH solution (Figure S21). The UV–vis absorption characteristic of the semiquinone radicals of FAD was also observed around 500–700 nm during the enzymatic reaction (Figure S22).61,62 These results clearly support the envisioned radical mechanism for the acylation reaction. Furthermore, DFT calculations also verify the SET process between the Breslow intermediate and the FAD cofactor (Figures S23–S25). Particularly, the Tyr283 residue, which is supposed to interact with the N1 atom of the FAD isoalloxazine ring, was calculated to decrease the free energy changes in the SET process, which is consistent with the experimental results for TbALS(D283Y) and its variants.

Table 1. Biocatalytic Radical Acylation of α-Bromoestera.

| entry | deviation from standard conditions | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 87 |

| 2 | increased concentration of 2a (2.0 mM) | 82 |

| 3 | increased concentration of 2a (4.0 mM) | 67 |

| 4 | no enzyme | n.d. |

| 5 | 130 μM FAD instead of TbALSKYH | <0.1 |

| 6 | 10 mM acetaldehyde instead of 1a | 9 |

| 7 | in the presence of 1.0 mM TEMPOL | 83 |

| 8 | aerobic conditions | 51 |

Standard reaction conditions: TbALSKYH (130 μM), 1a (10 mM), 2a (1.0 mM), ThDP (0.10 mM), MgSO4 (1.0 mM) in MOPS buffer (100 mM MOPS, pH = 7.5), 25 °C, 24 h under N2. Yield of 3aa was determined based on substrate 2a by GC-MS.

Next, the substrate scope for the TbALSKYH-catalyzed acylation reaction was investigated (Scheme 1). In addition to compound 1a, 2-oxobutyric acid (1b) was also accepted as an acyl donor. Corresponding acylated product 3ba was formed in 47% yield, whereas TbALSKYH showed significantly reduced activity toward benzoylformic acid (1c), which can generate a relatively stabilized benzoyl radical equivalent. As summarized in the bar graph in Scheme 1a, the substrate preference of TbALSKYH is remarkably inconsistent with the usual rules for NHC organocatalysis. The active site of TbALSKYH appears to be specialized for small and less stable radical intermediates, although it cannot accommodate bulky α-keto acids. A similar substrate preference was also observed for a range of α-bromoesters (Scheme 1b). In addition to 2a, secondary α-bromopropionate esters with different ester groups are also compatible. Isopropyl 2-bromopropionate (2b) and benzyl 2-bromopropionate (2c) were nicely converted into the corresponding β-ketoesters 3ab and 3ac in 60 and 61% yield, respectively. Surprisingly, TbALSKYH was found to show high acylation activity toward ethyl 2-bromoacetate (2d) and benzyl 2-bromoacetate (2e), which generate less stable primary carbon-centered radicals. Ethyl acetoacetate (3ad) and benzyl acetoacetate (3ae) were efficiently produced in 76 and 72% yield, respectively. In contrast, the presence of bulky substituents at the α-position reduced the activity of TbALSKYH. Ethyl α-bromophenylacetate (2f), which can produce a stabilized secondary benzyl radical, is less efficiently converted into ethyl 2-phenylacetoacetate (3af). Tertiary α-bromoesters 2g and 2h afforded only trace amounts of the target products, and α-hydroxyesters were generated via nonenzymatic SN1-type hydrolysis of C–Br bonds. Besides α-bromoesters, a series of α-bromoketones (2i–2o) and α-bromoamides (2p, 2q), which generate primary and secondary carbon-centered radicals, were also found to be acceptable for the present catalytic system. Using TbALSKYH, the corresponding β-diketones (3ai–3ao) and β-ketoamides (3ap, 3aq) were produced in moderate yields (Scheme 1c). Taken together, these results suggest that the efficiency of our catalytic system is determined mainly by the bulkiness of the substrates and that the reaction proceeds under control by the enzyme active site, regardless of the availability of radical intermediates. In the reaction of bulky substrates, we also observed the formation of the hydrogenated products, such as 4c and 4f, which can be generated in a two-electron catalytic cycle (Figures S20, S26, and S27). The slow access of these bulky substrates into the enzyme active site might lead to the overoxidation of the Breslow intermediate and result in the undesirable two-electron redox cycle of the FAD cofactor (Figure S28).59,60

Scheme 1. Scope for Acylation of α-Bromo Carbonyls.

Reaction conditions: TbALSKYH (130 μM), 1 (10 mM), 2 (1.0 mM), ThDP (0.10 mM), MgSO4 (1.0 mM) in MOPS buffer (100 mM MOPS, pH = 7.5), 25 °C, 24 h under N2. Yields of 3 were determined based on substrate 2 by GC-MS and LC-MS. a TbALS (V104K/D283Y/W484H/A560L) variant was used. b 6 h reaction time.

Finally, we applied the catalytic system of ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes to photocatalytic reactions that exploit the photoredox properties of FAD to utilize less activated radical precursors.63N-acyloxyphthalimides were selected as substrates that generate more challenging alkyl radicals via reductive decarboxylation12,13 and subjected to the acylation reaction using pyruvic acid (1a) as an acyl donor. Notably, TbALS(D283Y) and its variants were found to promote the acylation reaction of N-acyloxyphthalimide 5a under blue light irradiation (Figures S29). In particular, TbALS(V104Y/D283Y), generated by the docking-guided rational engineering of TbALS(D283Y), showed the highest activity and efficiently produced isopropyl methyl ketone (6aa) in 56% yield (112 TTN) (Figures S30 and S31). This cross-coupling reaction between the “non-benzoyl-type” acyl radical equivalent and the “non-benzylic” secondary alkyl radical highlights the catalytic potential of TbALS to utilize the short-lifetime radical intermediates. Taking this result, we next investigated the scope of acceptable substrates for the photocatalytic reaction (Scheme 2). In addition to 1a, TbALS(V104Y/D283Y) has accepted 2-oxobutyric acid (1b) as an acyl donor, affording ethyl isopropyl ketone (6ba) in 25% yield. On the other hand, the use of bulky benzoylformic acid (1c) results in negligible yield as in the acylation of α-bromoesters. With regard to N-acyloxyphthalimides, substrates 5b–5d, forming secondary and tertiary alkyl radicals, are also compatible. Acetylated products 6ab–6ad are obtained in moderate yields but as a racemic mixture (Figure S32). The active site of TbALS cannot distinguish small differences of alkyl substituents, such as methyl and ethyl groups, at the α-position. Surprisingly, TbALS(V104Y/D283Y) was found to promote the acetylation reaction of 5e and 5f even though these substrates form less stable primary alkyl radicals as an intermediate. 2-Butanone (6ae) and 4-phenyl-2-butanone (6af) were produced in 23 and 7% yield, respectively. In contrast, the reaction of N-acyloxyphthalimide 5g, which has a bulky aromatic substituent at the α-position, resulted in a complete loss of the activity of TbALS(V104Y/D283Y), although 5g generates a stabilized benzyl radical intermediate. These unique substrate preferences of TbALS variants, summarized in the bar graph in Scheme 2, reflect the characteristics of enzymatic transformations that are not observed in typical chemo-catalytic transformations. We suppose that the strict substrate recognition of TbALS may play an important role in controlling the high reactivity of the short-lifetime radicals. Starting with the findings in this study, further enzyme screening or extensive protein engineering would provide opportunities to expand the scope of current biocatalytic systems in the near future.

Scheme 2. Scope for Acylation of N-Acyloxyphthalimides.

Reaction conditions: TbALS(V104Y/D283Y) (5 μM), 1 (60 mM), 5 (1.0 mM), ThDP (0.10 mM), MgSO4 (1.0 mM) in Tris–HCl buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, pH = 8.5) containing DMF (10 v/v%), 25 °C, 12 h under irradiation of blue LED (465 nm) and N2 atmosphere. Yields of 6 were determined based on substrate 5 by GC-MS.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed NHC-mediated radical acylation reactions catalyzed by ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes. Through the screening of diverse ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes, TbALS, which has a characteristic UV–vis absorption band in the range of 500–600 nm, was identified as a promising catalyst. Furthermore, TbALSKYH, an engineered variant obtained by docking-guided rational engineering, showed high catalytic activity, especially toward the radical acylation reaction of α-bromo carbonyl compounds via formation of less stable radical intermediates. In addition, the catalytic machinery of TbALS was applied to the photocatalytic acylation reaction of N-acyloxyphthalimides by using the photoredox properties of the FAD cofactor. These findings highlight the great potential of ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes as catalysts for selective cross-coupling reactions involving challenging short-lifetime radicals. This study is expected to provide new insights into the radical chemistry of thiamine-based biocatalysts and NHC organocatalysts.

Materials and Methods

Docking Simulation and In Silico Mutation Analysis

The homodimer structure model of TbALS was generated by AlphaFold2.64 The qualities of these models were estimated using the global error scoring functions QMEANDisCo (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/qmean/) and AlphaFold2 pLDDT; 0.78 and 96.5, respectively. To construct models of TbALS obtaining ligands, the MOE (Molecular Operating Environment software, version 2019.01) was used. A crystal structure of acetohydroxyacid synthase derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PDB: 6BD9) was superposed on the model of TbALS, and this crystal structure was then deleted except for the FAD and ThDP structures from 6BD9. ThDP was edited to the Breslow intermediate by using the MOE builder. The TbALS model was then protonated using the protonate 3D tool of MOE at pH 7 and temperature 300 K and then optimized by energy minimization using the AMBER10: extended Hückel theory (EHT) force field (gradient = 0.01 RMS kcal·mol–1·A–2). The TbALS (D283Y) variant was generated with the protein builder tool of MOE. For the docking simulation, the force field of AMBER10:EHT and the implicit solvation model of the reaction field (R-field 1:80; cutoff 8,10) were selected, and ethyl 2-bromopropionate was constructed using the MOE builder. To construct a model of TbALS obtaining ethyl 2-bromopropionate, docking simulations were carried out with the general dock tool of MOE, and the best-scoring configurations were selected for further analysis. The residue scan tool of MOE was used for in silico mutation analysis of TbALS, and the settings were as follows: residues: G29, A30, L32, S76, V104, S105, F114, Q115, and K164 in chain A and R285, W484, and A560 in chain B; mutations: alanine, arginine, asparagine, aspartic acid, cysteine, glutamic acid, glutamine, glycine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, threonine, tryptophan, tyrosine, valine; site limit: 1; and affinity atoms: ethyl 2-bromopropionate. The effect of the mutation on the binding free energy (ΔG°bind) between ethyl 2-bromopropionate and the TbALS variants was evaluated; the relative binding free affinity changes (ΔΔG°bind) between the TbALS variant (ΔG°bind_variant) and TbALS mutant (ΔG°bind_WT) were obtained from the MOE.

Expression and Purification of TbALS Variants and Other ThDP/FAD-Dependent Enzymes

The expression plasmids encoding the gene of TbALS variants and other ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes were transformed into the chemically competent E. coli BL21-Gold(DE3) strain. The transformants were plated on an LB agar medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C overnight. A single colony was then inoculated into 10 mL of LB medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and cultured at 37 °C and 180 rpm for 5 h. The culture (1.0 mL) was then transferred into 100 mL of LB medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and cultivated at 37 °C and 150 rpm for another 3 h. The cell culture (10 mL) was then transferred to 1.5 L of LB medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and cultivated at 37 °C and 150 rpm. After the OD600 value reached approximately 0.6–0.7, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.20 mM to induce the expression of ThDP/FAD-dependent enzymes. The cultivation was continued at 18 °C and 150 rpm for 20 h. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 7000g for 10 min at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C. Next, the frozen cells were thawed at room temperature and resuspended in Tris–HCl buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) containing FAD (0.10 mM), ThDP (0.50 mM), and MgSO4 (1.0 mM). The cells were lysed by sonication (Branson Sonifier 250) on an ice bath, followed by incubation with Benzonase (125 units/μL, 2.0 μL). The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 8800g for 10 min at 4 °C. After filtration with Millex-GV (0.22 μm), the supernatant was loaded onto a Strep-Tactin Superflow high-capacity column (IBA Lifesciences), and the purified enzymes were eluted with MOPS buffer (100 mM MOPS, 1.0 mM MgSO4, pH 7.5) containing 2.5 mM desthiobiotin. The elution was then stored at −80 °C until further use. Purity of the protein was examined by SDS-PAGE analysis. The enzyme concentration was determined under denaturing conditions based on the extinction coefficient of free FAD (ε451 = 1.19 × 104 cm–1 M–1) purchased from TCI Co., Ltd.

General Procedure for the TbALS-Catalyzed Radical Acylation of α-Bromoesters, α-Bromoketones, and α-Bromoamides

The purified solution of TbALS variants was placed in a glovebox after degassing and N2 purging. To a 500 μL solution of TbALS variants in MOPS buffer (100 mM MOPS, 1.0 mM MgSO4, pH 7.5), ThDP (50 nmol) in H2O (5.0 μL), substrates 2a–2q (0.50 μmol) in DMSO (5.0 μL), and α-ketoacid 1a–1c (5.0 μmol) in H2O (5.0 μL) were added in the glovebox filled with N2 gas. After sealing, the samples were taken from the glovebox and incubated at 25 °C for 24 h. The reaction was quenched by adding EtOAc (800 μL) and 1,3,5-triethylbenzene (50 nmol) in DMSO (5.0 μL) as an internal standard. The mixture was then vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min. Finally, the organic layer was analyzed by GC-MS equipped with an Rxi-5Sil MS column (GL Science) to determine the yield of the products 3aa–3ac and 3ab–3ao. The yields of 3ap and 3aq were determined by LC-MS equipped with a YMC-Triart C18 TA12SP9-05Q1PT column instead of GC-MS.

General Procedure for the TbALS-Catalyzed Radical Acylation of N-Acyloxyphthalimides

The purified solution of TbALS variants was placed in a glovebox after degassing and N2 purging. To a 450 μL solution of the TbALS variants in Tris–HCl buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, 1.0 mM MgSO4, pH 8.5), ThDP (50 nmol) in H2O (5.0 μL), N-acyloxyphthalimide 5a–5g (0.50 μmol) in DMF (50 μL), and α-ketoacid 1a–1c (30 μmol) in H2O (10 μL) were added in the glovebox filled with N2 gas. After sealing, the samples were taken from the glovebox and incubated with irradiation of blue LED (465–470 nm, 130–140 lm) using a SynLED Parallel Photoreactor (Merck Ltd.). After 12 h, the reaction was quenched by adding Et2O (800 μL) and 1,3,5-triethylbenzene (50 nmol) in DMF (5.0 μL) as an internal standard. The mixture was then vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min. Finally, the organic layer was analyzed by GC-MS equipped with an Rxi-5Sil MS column (GL Science) and GC-FID equipped with SUPELCO Beta DEXTM 120 fused silica capillary column (Merck Ltd.) to determine the yield and enantiomeric ratio of the products.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Prof. Kohsuke Honda and Prof. Kentaro Miyazaki of Osaka University for their constructive suggestions regarding the enzyme assay. We are grateful to Assistant Prof. Takuya Kodama of Osaka University for technical assistance with the EPR experiments. The generous allotment of computation time from the Research Center for Computational Science, the National Institutes of Natural Sciences, Japan (Project: 24-IMS-C041), is also gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ALS

acetolactate synthase

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MOE

molecular operating environment

- NHC

N-heterocyclic carbene

- SET

single electron transfer

- TbALS

Thermobispora bispora acetolactate synthase

- TEMPOL

4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine 1-oxyl free radical

- ThDP

thiamine diphosphate

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.5c04484.

Sample preparation, experimental details, analytical data, amino acid and DNA sequences, and characterization data (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was prepared with contributions of all authors. All authors have approved of the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25H01579 (ForecastBiosyn), JP23H04554 (ForecastBiosyn), JP24H01136 (Bottom-up Biotech), JP22H05421 (Bottom-up Biotech), JP25H00887, JP24K01630, JP22K21348, JP22K14783, JP21K20535, JP21K05016, JST ACT-X Grant Number JPMJAX22B6 (Environments and Biotechnology), and Kaneko-Narita research fund (Protein Research Foundation).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Yi H.; Zhang G.; Wang H.; Huang Z.; Wang J.; Singh A. K.; Lei A. Recent Advances in Radical C–H Activation/Radical Cross-Coupling. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9016–9085. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. Recent advances in N-heterocyclic carbene-based radical catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 5630–5636. 10.1039/D0SC01538E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Xing X. N.; Huang J. H.; Lu L. Q.; Xiao W. J. Light opens a new window for N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 10605–10613. 10.1039/D0SC03595E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.; Schwenzer M.; Studer A. Radical NHC Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 11984–11999. 10.1021/acscatal.2c03996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q.; Du D.; Gao J. Radical Acylation of Alkenes by NHC-Organocatalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300832 10.1002/ejoc.202300832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leifert D.; Studer A. The Persistent Radical Effect in Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 74–108. 10.1002/anie.201903726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. L.; Liu Y. Q.; Zou W. L.; Zeng R.; Zhang X.; Liu Y.; Han B.; He Y.; Leng H. J.; Li Q. Z. Radical Acylfluoroalkylation of Olefins through N-Heterocyclic Carbene Organocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1863–1870. 10.1002/anie.201912450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Peng Q.; Guo D.; Wang J. NHC-Catalyzed Radical Trifluoromethylation Enabled by Togni Reagent. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 443–447. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b04203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.-B.; Wang Z.-H.; Li J.-M.; Wu C. Modular synthesis of α-aryl β-perfluoroalkyl ketones via N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 3801–3804. 10.1039/D0CC00293C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. Radical N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis for β-ketocarbonyl synthesis. Tetrahedron 2021, 91, 132212 10.1016/j.tet.2021.132212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki Y.; Ohnishi N.; Kakeno Y.; Takemoto S.; Ishii T.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. Aryl radical-mediated N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3848. 10.1038/s41467-021-24144-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T.; Kakeno Y.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Alkylation of Aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3854–3858. 10.1021/jacs.9b00880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T.; Ota K.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed Radical Relay Enabling Vicinal Alkylacylation of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 14073–14077. 10.1021/jacs.9b07194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakeno Y.; Kusakabe M.; Nagao K.; Ohmiya H. Direct Synthesis of Dialkyl Ketones from Aliphatic Aldehydes through Radical N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8524–8529. 10.1021/acscatal.0c02849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guin J.; De Sarkar S.; Grimme S.; Studer A. Biomimetic Carbene-Catalyzed Oxidations of Aldehydes Using TEMPO. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8727–8730. 10.1002/anie.200802735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I.; Im H.; Lee H.; Hong S. N-Heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed deaminative cross-coupling of aldehydes with Katritzky pyridinium salts. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 3192–3197. 10.1039/D0SC00225A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.-B.; Wan D.-H. C–C Bond Acylation of Oxime Ethers via NHC Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 1049–1053. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c04248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick J. B.; Duffus B. R.; Duschene K. S.; Shepard E. M. Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4229–4317. 10.1021/cr4004709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridwell-Rabb J.; Li B.; Drennan C. L. Cobalamin-Dependent Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes: Capitalizing on Old Motifs for New Functions. ACS Bio & Med. Chem. Au 2022, 2, 173–186. 10.1021/acsbiomedchemau.1c00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedison T. M.; Heyes D. J.; Scrutton N. S. Making molecules with photodecarboxylases: A great start or a false dawn?. Curr. Res. Chem. Biol. 2022, 2, 100017 10.1016/j.crchbi.2021.100017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Arnold F. H. Navigating the Unnatural Reaction Space: Directed Evolution of Heme Proteins for Selective Carbene and Nitrene Transfer. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1209–1225. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel M. A.; Greenberg N. R.; Oblinsky D. G.; Hyster T. K. Accessing non-natural reactivity by irradiating nicotinamide-dependent enzymes with light. Nature 2016, 540, 414–417. 10.1038/nature20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegasiewicz K. F.; Cooper S. J.; Gao X.; Oblinsky D. G.; Kim J. H.; Garfinkle S. E.; Joyce L. A.; Sandoval B. A.; Scholes G. D.; Hyster T. K. Photoexcitation of flavoenzymes enables a stereoselective radical cyclization. Science 2019, 364, 1166–1169. 10.1126/science.aaw1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Wang B.; Wang Y.; Jiang G.; Feng J.; Zhao H. Photoenzymatic enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroalkylation. Nature 2020, 584, 69–74. 10.1038/s41586-020-2406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q.; Chin M.; Fu Y.; Liu P.; Yang Y. Stereodivergent atom-transfer radical cyclization by engineered cytochromes P450. Science 2021, 374, 1612–1616. 10.1126/science.abk1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui J.; Zhao Q.; Huls A. J.; Soler J.; Paris J. C.; Chen Z.; Reshetnikov V.; Yang Y.; Guo Y.; Garcia-Borràs M.; Huang X. Directed evolution of nonheme iron enzymes to access abiological radical-relay C(sp3)–H azidation. Science 2022, 376, 869–874. 10.1126/science.abj2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergel S.; Soler J.; Klein A.; Schülke K. H.; Hauer B.; Garcia-Borràs M.; Hammer S. C. Engineered cytochrome P450 for direct arylalkene-to-ketone oxidation via highly reactive carbocation intermediates. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 606–617. 10.1038/s41929-023-00979-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L.; Li D.; Mai B. K.; Bo Z.; Cheng L.; Liu P.; Yang Y. Stereoselective amino acid synthesis by synergistic photoredox-pyridoxal radical biocatalysis. Science 2023, 381, 444–451. 10.1126/science.adg2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N.; Toraya T. Molecular architectures and functions of radical enzymes and their (re)activating proteins. J. Biochem. 2015, 158, 271–292. 10.1093/jb/mvv078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati S.; Rabe von Pappenheim F.; Tittmann K. Frontiers in the enzymology of thiamin diphosphate-dependent enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2022, 76, 102441 10.1016/j.sbi.2022.102441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tittmann K. Reaction mechanisms of thiamin diphosphate enzymes: redox reactions. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 2454–2468. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wille G.; Meyer D.; Steinmetz A.; Hinze E.; Golbik R.; Tittmann K. The catalytic cycle of a thiamin diphosphate enzyme examined by cryocrystallography. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 324–328. 10.1038/nchembio788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Chen H.; Yu L.; Peng X.; Zhang J.; Xing Z.; Bao Y.; Liu A.; Zhao Y.; Tian C.; Liang Y.; Huang X. A light-driven enzymatic enantioselective radical acylation. Nature 2024, 625, 74–78. 10.1038/s41586-023-06822-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Xu S.; Chen H.; Yang Y. Unnatural Thiamine Radical Enzymes for Photobiocatalytic Asymmetric Alkylation of Benzaldehydes and α-Ketoacids. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 9144–9150. 10.1021/acscatal.4c02752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach A. K.; Fraas S.; Harder J.; Tabbert A.; Brinkmann H.; Meyer A.; Ermler U.; Kroneck P. M. Cyclohexane-1,2-Dione Hydrolase from Denitrifying Azoarcus sp. Strain 22Lin, a Novel Member of the Thiamine Diphosphate Enzyme Family. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 6760–6769. 10.1128/JB.05348-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loschonsky S.; Wacker T.; Waltzer S.; Giovannini P. P.; McLeish M. J.; Andrade S. L.; Müller M. Extended Reaction Scope of Thiamine Diphosphate Dependent Cyclohexane-1,2-Dione Hydrolase: from C-C Bond Cleavage to C-C Bond Ligation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14402–14406. 10.1002/anie.201408287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loschonsky S.; Waltzer S.; Fraas S.; Wacker T.; Andrade S. L.; Kroneck P. M.; Müller M. Catalytic scope of the thiamine-dependent multifunctional enzyme cyclohexane-1,2-dione hydrolase. ChemBioChem. 2014, 15, 389–392. 10.1002/cbic.201300673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller Y. A.; Schulz G. E. Structure of the Thiamine- and Flavin-Dependent Enzyme Pyruvate Oxidase. Science 1993, 259, 965–967. 10.1126/science.8438155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tittmann K.; Wille G.; Golbik R.; Weidner A.; Ghisla S.; Hübner G. Radical Phosphate Transfer Mechanism for the Thiamin Diphosphate- and FAD-Dependent Pyruvate Oxidase from Lactobacillus plantarum. Kinetic Coupling of Intercofactor Electron Transfer with Phosphate Transfer to Acetyl-thiamin Diphosphate via a Transient FAD Semiquinone/Hydroxyethyl-ThDP Radical Pair. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 13291–13303. 10.1021/bi051058z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan E. C. M.; Hoque M. M.; Hossain M. T.; Yamamoto T.; Imamura S.; Suzuki K.; Sekiguchi T.; Takenaka A. The structures of pyruvate oxidase from Aerococcus viridans with cofactors and with a reaction intermediate reveal the flexibility of the active-site tunnel for catalysis. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F 2007, 63, 900–907. 10.1107/S1744309107041012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann P.; Weidner A.; Pech A.; Stubbs M. T.; Tittmann K. Structural basis for membrane binding and catalytic activation of the peripheral membrane enzyme pyruvate oxidase from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 17390–17395. 10.1073/pnas.0805027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Škerlová J.; Berndtsson J.; Nolte H.; Ott M.; Stenmark P. Structure of the native pyruvate dehydrogenase complex reveals the mechanism of substrate insertion. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5277. 10.1038/s41467-021-25570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. Y.; Wang A. Y.; Cronan J. E. Molecular cloning, DNA sequencing, and biochemical analyses of Escherichia coli glyoxylate carboligase. An enzyme of the acetohydroxy acid synthase-pyruvate oxidase family. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 3911–3919. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53559-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplun A.; Binshtein E.; Vyazmensky M.; Steinmetz A.; Barak Z. E.; Chipman D. M.; Tittmann K.; Shaanan B. Glyoxylate carboligase lacks the canonical active site glutamate of thiamine-dependent enzymes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 113–118. 10.1038/nchembio.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Li Y.; Wang X. Acetohydroxyacid synthases: evolution, structure, and function. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 8633–8649. 10.1007/s00253-016-7809-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonhienne T.; Garcia M. D.; Fraser J. A.; Williams C. M.; Guddat L. W. The 2.0 Å X-ray structure for yeast acetohydroxyacid synthase provides new insights into its cofactor and quaternary structure requirements. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171443 10.1371/journal.pone.0171443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipman D. M.; Duggleby R. G.; Tittmann K. Mechanisms of acetohydroxyacid synthases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005, 9, 475–481. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Li Y.; Liu X.; Sun J.; Li X.; Lin J.; Yang X.; Xi Z.; Shen Y. Molecular architecture of the acetohydroxyacid synthase holoenzyme. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 2439–2449. 10.1042/BCJ20200292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey V.; Ghisla S. ROLE OF CHARGE-TRANSFER INTERACTIONS IN FLAVOPROTEIN CATALYSIS. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1974, 227, 446–465. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb14407.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick D. B. INTERACTIONS OF FLAVINS WITH AMINO ACID RESIDUES: ASSESSMENTS FROM SPECTRAL AND PHOTOCHEMICAL STUDIES. Photochem. Photobiol. 1977, 26, 169–182. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1977.tb07471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson R. P.; Krey G. D. Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Tyrosine-98 in the Flavodoxin from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough): Regulation of Oxidation-Reduction Properties of the Bound FMN Cofactor by Aromatic, Solvent, and Electrostatic Interactions. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 8505–8514. 10.1021/bi00194a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogués I.; Tejero J.; Hurley J. K.; Paladini D.; Frago S.; Tollin G.; Mayhew S. G.; Gómez-Moreno C.; Ceccarelli E. A.; Carrillo N.; Medina M. Role of the C-Terminal Tyrosine of Ferredoxin-Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Reductase in the Electron Transfer Processes with Its Protein Partners Ferredoxin and Flavodoxin. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 6127–6137. 10.1021/bi049858h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D. The Role of the si-Face Tyrosine of a Homodimeric Ferredoxin-NADP+ Oxidoreductase from Bacillus subtilis during Complex Formation and Redox Equivalent Transfer with NADP+/H and Ferredoxin. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1741. 10.3390/antiox12091741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonhienne T.; Garcia M. D.; Noble C.; Harmer J.; Fraser J. A.; Williams C. M.; Guddat L. W. High Resolution Crystal Structures of the Acetohydroxyacid Synthase-Pyruvate Complex Provide New Insights into Its Catalytic Mechanism. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 11981–11988. 10.1002/slct.201702128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y.; Noda S.; Shirai T.; Kondo A. Direct 1,3-butadiene biosynthesis in Escherichia coli via a tailored ferulic acid decarboxylase mutant. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2195. 10.1038/s41467-021-22504-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel S.; Vyazmensky M.; Vinogradov M.; Berkovich D.; Bar-Ilan A.; Qimron U.; Rosiansky Y.; Barak Z. E.; Chipman D. M. Role of a Conserved Arginine in the Mechanism of Acetohydroxyacid Synthase: CATALYSIS OF CONDENSATION WITH A SPECIFIC KETOACID SUBSTRATE. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 24803–24812. 10.1074/jbc.M401667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonhienne T.; Garcia M. D.; Pierens G.; Mobli M.; Nouwens A.; Guddat L. W. Structural insights into the mechanism of inhibition of AHAS by herbicides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E1945–E1954. 10.1073/pnas.1714392115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonhienne T.; Low Y. S.; Garcia M. D.; Croll T.; Gao Y.; Wang Q.; Brillault L.; Williams C. M.; Fraser J. A.; McGeary R. P.; West N. P.; Landsberg M. J.; Rao Z.; Schenk G.; Guddat L. W. Structures of fungal and plant acetohydroxyacid synthases. Nature 2020, 586, 317–321. 10.1038/s41586-020-2514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tittmann K.; Schröder K.; Golbik R.; McCourt J.; Kaplun A.; Duggleby R. G.; Barak Z. E.; Chipman D. M.; Hübner G. Electron Transfer in Acetohydroxy Acid Synthase as a Side Reaction of Catalysis. Implications for the Reactivity and Partitioning of the Carbanion/Enamine Form of (α-Hydroxyethyl)thiamin Diphosphate in a “Nonredox” Flavoenzyme. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 8652–8661. 10.1021/bi049897t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval B. A.; Meichan A. J.; Hyster T. K. Enantioselective Hydrogen Atom Transfer: Discovery of Catalytic Promiscuity in Flavin-Dependent ‘Ene’-Reductases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11313–11316. 10.1021/jacs.7b05468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwinn K.; Ferré N.; Huix-Rotllant M. UV-visible absorption spectrum of FAD and its reduced forms embedded in a cryptochrome protein. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 12447–12455. 10.1039/D0CP01714K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsova Y. V.; Kulik L. V.; Mamedov M. D.; Baykov A. A.; Bogachev A. V. Flavodoxin with an air-stable flavin semiquinone in a green sulfur bacterium. Photosynth. Res. 2019, 142, 127–136. 10.1007/s11120-019-00658-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H.; Hyster T. K. From Ground-State to Excited-State Activation Modes: Flavin-Dependent “Ene”-Reductases Catalyzed Non-natural Radical Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 1446–1457. 10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior A. W.; Evans R.; Jumper J.; Kirkpatrick J.; Sifre L.; Green T.; Qin C.; Žídek A.; Nelson A. W. R.; Bridgland A.; Penedones H.; Petersen S.; Simonyan K.; Crossan S.; Kohli P.; Jones D. T.; Silver D.; Kavukcuoglu K.; Hassabis D. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 2020, 577, 706–710. 10.1038/s41586-019-1923-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.