Summary

Peripheral T cell lymphomas (PTCLs) comprise heterogeneous malignancies with limited therapeutic options. To uncover targetable vulnerabilities, we generate a collection of PTCL patient-derived tumor xenografts (PDXs) retaining histomorphology and molecular donor-tumor features over serial xenografting. PDX demonstrates remarkable heterogeneity, complex intratumor architecture, and stepwise trajectories mimicking primary evolutions. Combining functional transcriptional stratification and multiparametric imaging, we identify four distinct PTCL microenvironment subtypes with prognostic value. Mechanistically, we discover a subset of PTCLs expressing Epstein-Barr virus-specific T cell receptors and uncover the capacity of cancer-associated fibroblasts of counteracting treatments. PDXs’ pre-clinical testing captures individual vulnerabilities, mirrors donor patients’ clinical responses, and defines effective patient-tailored treatments. Ultimately, we assess the efficacy of CD5KO- and CD30- Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells (CD5KO-CART and CD30_CART, respectively), demonstrating their therapeutic potential and the synergistic role of immune checkpoint inhibitors for PTCL treatment. This repository represents a resource for discovering and validating intrinsic and extrinsic factors and improving the selection of drugs/combinations and immune-based therapies.

Keywords: T cell lymphoma, patient-derived tumor xenografts, clonal evolution, stratification, microenvironment, repository, precision medicine, CAR-T, drug screenings, pre-clinical trials

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We establish 102 patient-derived models covering common and rare PTCL entities

-

•

PTCL models genomically and transcriptionally recapitulate matched primary tumor

-

•

We identify pathogenic liabilities, effective combinations, and response predictors

-

•

We provide an innovative host-centric PTCL classification

Peripheral T cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are heterogeneous malignancies with limited therapeutic options. Fiore et al. introduce 102 patient-derived PTCL models to dissect pathogenetic mechanisms, identify intrinsic and host-mediated vulnerabilities, and implement innovative therapeutic approaches.

Introduction

In 2023, a total of 80,550 cases of lymphomas were diagnosed in the USA, with a staggering number of 20,180 deaths (https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/nhl.html). Peripheral T cell lymphomas (PTCLs) represent ∼15% of all lymphomas and comprise >30 different entities.1,2 PTCL patients display a remarkable clinical heterogeneity, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) ranging from 14% (adult T cell leukemia-lymphoma [ATLL]) to 70% (ALK+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma [ALCL]).3 Regrettably, chemotherapies (including anthracycline-containing regimens) have limited efficacy, and relapsed/refractory PTCLs experience a short OS (∼6 months),4 calling for effective agents and/or combinations.5 Improvements in PTCL classification, predictive biomarkers identification, and targeted agent development remain unmet medical needs.6

In recent years, multiple drugs were approved, and several are in clinical trials. Nevertheless, response rates remain disappointing (25%–29%), with progression-free survival < 4 months.6,7,8

This is mainly due to PTCL heterogeneity and rarity, as well as to the lack of informative models (only a few PTCL cell lines mainly corresponding to ATLL and ALCL subsets). Cell lines are unable to fully recapitulate the biology and therapeutic responsiveness of human cancers.9,10,11 Many of these limitations are shared by transgenic mice, including a few PTCL models.12,13,14,15,16

Patient-derived tumor xenografts (PDXs) can provide critical insight into overcoming treatment resistance, identifying targetable liabilities17,18,19,20,21,22 and microenvironment stimuli,23,24,25 and enabling pre-clinical trials.26,27 Despite limitations,28,29,30,31 PDXs are considered among the most informative tools to model human cancers.26,27,32,33 However, lymphoma PDXs remain poorly represented.17,34,35,36,37

Here, we describe an extensive library of PDXs corresponding to different PTCL entities. We show that these models (1) faithfully recapitulate the biological features and driver defects of their matched donor neoplasms, (2) allow the recognition of causative genetic defects and suitable dependencies, (3) underline the lymphoma-host dependencies and host-related refractory mechanisms, and (4) represent informative platforms to test established/innovative and cell-based therapeutic strategies. This repository will foster scientific discoveries and the development of therapeutic regimens tailored to molecularly defined subgroups, advancing personalized approaches for PTCL patients.

Results

Establishing a living PTCL PDX biorepository

We implanted 308 PTCLs from fresh or cryopreserved samples, yielding 102 patient-derived tumor models comprising 88 PDXs and 14 PDX-derived lines (PDX-Dlines; Figures 1A and 1B; Table S1) and 3,283 PDX cryopreserved seed samples (median passage: T4).

Figure 1.

Generation of PTCL PDX and PDX derivates

(A) Schematic representation of PDX generation and propagation strategies. Different primary sample sources and routes of implantation are annotated.

(B) Pie chart indicating the PTCL total and subtype-specific number of PDXs generated.

(C) PTCL PDX subtype-specific percentage of engraftment.

(D) Number of PDXs generated from naive or refractory patients for different PTCL subtypes.

(E) Time of engraftment (in days) of PDXs belonging to different PTCL subcategories along different rounds of propagation (T1 to T10). Error bars represent standard deviations.

(F) Representative MRI scanning of 4 different organs (lung, kidney, liver, and spleen) of an NSG mouse implanted with the different PDX. Arrows indicate lymphoma infiltration.

(G) Representative H&E staining of 4 different organs (lung, kidney, liver, and spleen) of NSG mice implanted with the AITL PDX model (magnification ×40).

(H) Flow cytometric analysis of EBV+ AITL PDX IL129A before (upper panels) and after CD19-ADC treatment (lower panels).

(I) Schematic representation of PDX-Dline generation strategies.

The biorepository represents the most common PTCL subtypes (Figure 1A). Higher engraftment rates were seen in relapsed/refractory PTCL (r/r, 62%; naive, 38%), with a 36% engraftment rate on average for the most common T/natural killer (NK) entities (PTCL not otherwise specified [PTCL-NOS], angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma [AITL], and ALCL). Also, rates were not linked to other parameters (Table S1). Rare entities engrafted less efficiently (Table S1,<15%) except Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T cell lymphoma [MEITL] (Figures 1C and 1D). We also generated six PDXs from two longitudinal samples of the same patient. The engraftment time ranged from 3 weeks to 10 months (Figures 1E and S1A–S1H), remaining relatively stable along serial passages, except for AITL, which displayed progressively longer times over serial transfers (Figure S1B). Tumors implanted subcutaneously seldom homed to distant tissues (lungs, liver, and/or spleen), sometimes without a concomitant expansion at the implantation site (Figures 1F, 1G, and S1I). Seventy-three of 88 models propagated ≥2 serial passages without EBV+ (Epstein Barr virus) lymphoblastoid CD19+ B cells (EBV-LCLs). Some EBV+ LCLs (1%–90%) were detected (30 cases); primarily AITL (n = 10) (Table S1) and prominent expansions (>90%) were also seen (18 samples, 17% of all engraftments). EBV+ LCLs were present intratumorally in visceral tissues (i.e., kidney, spleen, liver, and lung) and, in most cases, expanded over serial passages (Figures 1H and S1J). EBV+ PDX and samples with no lymphoma expansion (6–9 months from injection) were failures (Figure S1J). Aiming to eradicate EBV+ LCLs, we treated six EBV+ PDXs with the anti-CD19 drug-conjugated loncastuximab tesirine (ADCT-402).38 The antibody successfully eradicated B cells, but only one PDX was established and serially propagated (interleukin [IL]129A AITL PDX, Figures 1H, S1K, and S1L). Similar data were obtained by treating EBV+ PDX in complement-proficient (Hc1) mice with rituximab (data not shown).

Lastly, we established fourteen continuous PDX-Dlines using cytokine-supplemented media (with/without IL-2 and IL15) or murine cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs; Figure 1I; Table S1).

PDXs maintain the immunophenotypic and TCR clonotype profiles of primary PTCLs

PTCL PDX histologically/cytologically resembled their matched donor samples (Figures 2A and S2A). In 29 cases, mostly AITL PDX, normal T and B cells (or EBV+ LCLs) were co-mingled with neoplastic elements, particularly in early passages (Figures 2B and 2C). PDX lineage fidelity and individual phenotypes were preserved, as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry and immunophenotyping (Figures 2D and S2B). Gene rearrangement analysis demonstrated that PDX and matched primaries share identical T cell receptor (TCR) DNA rearrangements (Tables S1 and S2; Figures 2E, S2C, and S2D). By total RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), primary and PDX displayed a rich TCR clonotype representation (Figures S2E–S2F). Explicit α and/or β TCR lymphoma clonotypes (>5% of the TCR) were documented in ∼50% of primary samples, with a higher clonal representation in PDX (Figures 2E and S2E–S2G).

Figure 2.

PDX faithfully mimics matched primary donor samples

(A) H&E staining of primary lymphomas (green frames) and matched PDX (yellow frames, magnification 40×).

(B) EBV in situ hybridization depicting EBV+ lymphoblastoid cells (EBER+) in AITL PDX.

(C) Multiparametric in situ imaging (MISI) of representative AITL lesions derived from diagnostic (lymph node) and patient-matched PDX (lung).

(D) Pie graph reporting the expression of 26 immune-histochemistry (IHC) markers in primary and PDX (T1 to T16) samples. Red: highly expressed, green: low expressed.

(E) α/β TCR clonal representation of primary and PDX, along serial passages.

(F) EBV positivity among PTCLs.

(G) TCR repertoire against EBV peptides and their mismatched sequences compare to known reference sequences.

(H) Prediction binding of EBV peptides to MHC class II determinants.

(I) In vitro competitive binding assay of EBV tetramers to recombinant DRB1.

Since antigen-driven TCR engagement facilitates cell growth and treatment resistance,39 we assessed the TCR usage and antigen specificity (https://vdjdb.cdr3.net/). We observed a relative over-representation of selected VDJ (TRA-V29DV5, V9-2, and V13-1), particularly in EBV+ AITL (Figure S2H). Notably, EBV transcripts were identified (Figure 2F), corresponding to both lytic and latent genes (Figure S2I) and, seldom, to HTLV-1 and HHV6 transcripts (Figure S2J).40 Remarkably, individual primary/PDX displayed dominant TCR clones expressing canonical or mismatched TCR CDR3 motifs known to bind EBV peptides (Figures 2G, S2K, and S2L; Table S2). To extend this prediction, we estimated the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II binding for multiple EBV peptides (Figure 2H). Next, we executed a competitive in vitro binding assay showing a high binding affinity of Epstein barr Nuclear Antigen (EBNA)-3B/4 peptides (IC50: 0.08 μM) to recombinant DRB1 (IL36, Figure 2I).

Lastly, we detected explicit immunoglobulin H (IgH) clones, at very low frequency in primary tumors (Figure S2M). Exceptions included rare primary AITL and EBV+ PDX (Figure S2N).

PDXs preserve the transcriptomic landscape of primary lymphomas

We first compared the transcriptomic profiles of primary (n = 79) and matched PDX (n = 140; Table S2) by principal-component analysis (PCA), demonstrating a partial overlap (Figure S3A), likely due to the tumor content (Figures S3B and S3C) and host human cells (Figures S3C–S3E). Hence, we performed a surrogate variable analysis (see STAR Methods) and established distinct clusters corresponding to ALK+ ALCL, ALK− ALCL, and PTCL-NOS/AITL, demonstrating a close correspondence of primary and PDX (Figures 3A, 3B, and S3F). PTCL-NOS and AITL were stratified using Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment, differential expression, pathway analyses, and publicly available signatures (Figures 3C and S3G–S3I), confirming known transcripts in different subtypes (Figure S3H). As selected biomarkers distinguish PTCL subtypes,41,42 we established PDX classifiers for each subgroup enriched by known differentially expressed genes (Figure S3J). The PDX-Dlines also showed close transcriptional signatures to matched donor PDX (Figure S3K).

Figure 3.

PDX maintains the inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity of matched lymphoma

(A) PCA of PDX and primary lymphoma-matched samples (AITL, PTCL-NOS, and ALCL) based on the bulk RNA expression levels excluding non-lymphoma reads in primary samples.

(B) Heatmap and unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on 1,000 top differentially expressed genes of PDX and primary lymphomas belonging to the main 4 PTCL subcategories (AITL, PTCL-NOS, ALK+ ALCL, and ALK- ALCL).

(C) Supervised hierarchical clustering of primary and PDX based on 12 known publicly available signatures stratifying different PTCL entities (A: PMC2817630_AITL, B: PMC2817630_ATLL, C; PMC4014836_TBX21/GATA3, D: PMC20159827_ALK+, E: PMC2817630_ALK+, F: PMC4014836_ALK+/−, G: PMC4014836_AITL, H: PMC4014836_ATLL, I; PMC4014836_ATLL, J: PMC2817630_CT_PTCL, K; PMC6161771_DUSP22, and L: PMC4014836_ENKTL).

(D) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) clusters annotation based on single-cell RNA-seq expression of PTCL-NOS and AITL (IL-2 and IL138A) and ALCL (IL69, IL79 and IL89) PDX.

(E) Dot plot representation of top gene transcripts in each UMAP cluster of the PDX models sequenced by single-cell RNA-seq.

(F) UMAP cluster annotation based on single-cell RNA-seq expression (IL138A primary and T3 PDX model). Cell types have been annotated on the right part of the graph.

(G) Hallmark analysis of selected differentially expressed pathways among three tumor clusters of IL138A primary and PDX, based on single-cell RNA-seq expression data. Cluster 0 was present in both primary and PDX, while clusters 1 and 2 were enriched in IL138A PDX vs. the correspondent primary.

(H) Heatmap reporting fusions of primary and PDX samples belonging to different PTCLs. Only chimeras with a pathogenetic score ≥0.7 are depicted.

(I) Antitumoral effect of AZD-6244 in TO-ALCL-Belli PDX model (n = 8 mice/group). Error bars represent standard deviations.

(J) Circle pot depicting fusion landscapes of IL-2 and IL19 primary and PDX samples.

By single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) (5 PDXs, Table S2), models were individually segregated at cluster resolution, even within the same entity (i.e., ALK+ ALCL, Figures 3D and 3E). Tumor clusters were common between primary and PDX (#1 and #2) (Figures 3F and 3G), and normal human stromal cells were depleted in PDX (#6 and #8, populated by normal CD8+ T cells and monocytes, respectively) (Figures 3F and S3L).

Fusion transcripts are common in PTCL and typical to histologic subtypes.2 We thus searched for chimeric transcripts (see Methods; Table S3) and identified 4,022 gene fusions across 206 samples. Previously identified fusions were annotated,43,44,45 as well as unknown putative tumorigenic fusions involving a variety of T cell genes (ACADVL-VAV1, MAZ-NF1, VASP-PPP2R1A, TET3-IMMT, MYL3-SETD2, TOX-MYBL1, IL17RA-RP11-363L24.3, and SMG1-NFATC3) (Table S3; Figure 3H). In ACADVL-VAV1, ACADVL was fused in-frame, while VAV1 translated to a truncated protein lacking its negative regulatory domain (Figure S3M), reminiscent of other oncogenic VAV1 fusion proteins.46,47 Since Ras signaling can contribute to PTCL pathogenesis,48,49,50,51 we validated the MAZ-NF1 fusion of an ALK− ALCL PDX. The predicted outcome was a truncated NF1 protein lacking activity (Figures S3N–S3P). Meanwhile, primary and PDX lost the second NF1 allele (Figure S3P), leading to the deregulated activation of Ras. Of note, we observed the loss of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure S3Q) and the improved PDX outcome in vivo (Figure 3I) upon selumetinib treatment (AZD-6244, an MEK inhibitor), a compound with limited activity in other PDX-Dlines (Figure S3R).

Since fusion transcripts are informative biomarkers of disease identity52,53 and serve as surrogates for tracing clonal evolution,53 we explored their landscape in two models (IL-2 and IL19), derived from the same donor at different time points (Figures 3J, S3S, and S3T). PDX displayed several undetectable fusions in primary samples (IL-2, n = 62, and IL19, n = 68), some co-shared (n = 36). By quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (RT-qPCR - n = 9) and Sanger sequencing (n = 3, Figures S3U and S3V), we confirmed selected fusions in PDX and primary samples (Figure S3V). Remarkably, emerging fusions in the relapsed sample (primary IL19) and corresponding PDX suggested the occurrence of clonal trajectories in part shared and maintained along the diagnostic, PDX samples, and even PDX-Dlines (Figures S3U and S3V).

PTCL PDXs retain pathogenetic drivers and inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity

We performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) in 223 samples (34 primary, 29 normal, and 160 PDX samples and PDX-Dlines), derived from 49 different models (Table S2). Having assessed the contribution of human and mouse reads (Figure S4A), copy-number alteration (CNA) demonstrated significant overlaps between primary and corresponding PDX (Table S4; Figures 4A and S4B). Globally, PTCL-NOS and ALK− ALCL displayed a higher degree of DNA structural alterations (Figure 4B), including known abnormalities (e.g., 6q21 and 1q+ or 3q31.3+ in ALK− ALCL) and defects associated with pathogenic alterations (e.g., PRDM1 and MIR17HG), than other histology.54,55 ALCL displayed specific gains at 1p36.22 and 19q13.42, occurring in regions harboring pathogenetic TNFRSF8 (CD30) and KIR2FDL1/KIR3DL2 genes.56,57,58

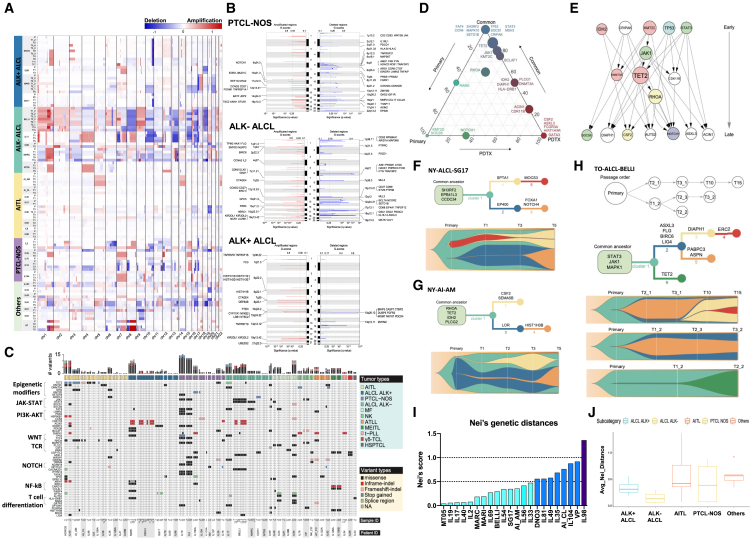

Figure 4.

PTCL PDX models mutational landscape and clonal evolution

(A) Global copy-number variation (CNV) analysis of primary and PDX along propagation.

(B) Chromosome view of genes included in the recurrent deleted or amplified genomic regions in PTCL-NOS and ALCL (ALK+ and ALK−).

(C) Mutational landscape of PTCL primary and PDX samples assessed by WES. Variant sites with read depth lower than five are marked as NA. For the sample ID, “P” stands for primary tumors.

(D) Ternary plot of mutation frequency in recurrently mutated genes, comparing primary tumor-specific (left, green), PDX-specific (right, red), and shared (top, blue) alterations. The size of each node represents the mutation frequency.

(E) PDX tumor evolutionary directed graph of gene mutations. Arrows show the order in which mutations occur. The size of each node corresponds to the frequency of mutations.

(F–H) Tumor evolution models of NY-ALCL-SG, NY-AI-AM, and TO-ALCL-BELLI PDX models. Fish plots (bottom panels) show dynamic changes in CCF of each mutation cluster along serial passages, as depicted in the inferred phylogenetic trees (top panels).

(I) Nei’s genetic distance indicates the global evolution score of PDX models.

(J) Nei’s genetic distance indicates the global evolution score of PDX derived from different PTCL entities. Error bars represent standard deviations.

We found a high concordance of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertion or deletions (indels) between primary tumors and matched PDX (Figures S4C and S4D; Table S5) with a higher median variant allele frequency (VAF) in PDX (50% vs. 40%, respectively, p < 2.2e−16, t test; Figure S4E). Globally, 3,430 non-synonymous somatic variants were recognized (Table S5), mostly missense (77%), 11% splice site, 4% stop-gain, 4% in-frame, and 4% frameshift. A total of 1,582 were classified as pathogenetic SNVs. These involved chromatin modifiers, JAK-STAT, and TCR-associated genes (e.g., TET2, DNMT3A, JAK1, STAT3, RHOA, TP53, and NOTCH1).37,59,60,61,62 Previously undescribed putative tumorigenic variants (e.g., DIAPH1, FAT4, CRIPAK, SH3RF2, and BCLAF163,64,65,66,67) were detected (Figure 4C). Oncogenic drivers were enriched in AITL (TET2 and RHOA),68 ALK− ALCL (JAK1 and STAT3),69 and mycosis fungoides [MF] (PLCG1).70 Most mutations were faithfully shared between primary tumors and along PDX passages. Conversely, some were exclusive to either primary (e.g., KMT2D) or PDX (e.g., CSF2, GATA3, and ASXL3; Figure 4D) or emerged along serial PDX passages (AUTS2 and CSF2, Figure S4F). Higher mutational burdens were observed in ALK− ALCL, PTCL-NOS, and MF (Figure S4G). Lastly, we screened 104 normal/primary/PDX/PDX-Dline samples by deep sequencing and annotated 537 mutations in 450 pathogenetic genes (Table S2). When we compared WES and deep sequencing analyses (data not shown), we observed >90% concordance with an increased VAF of selected alterations in propagated PDX (Figure S4H).

To explore the evolutionary mutation trajectories, we built a tumor evolutionary directed graph71,72 showing that ancestor mutations usually occurred in STAT3, TP53, IDH2, and KMT2C, followed sequentially by those in JAK1, CDK11B, TET2, and RHOA. Mutations in ACIN1, NOTCH1, DIAPH1, and CSF2 were mostly acquired along PDX propagation (Figure 4E). We then implemented a clonal evolution analysis on 29/49 models using cancer cell fraction (CCF) estimation by ABSOLUTE.73 We classified a clonal mutation if the CCF was >0.85 with a probability >0.5 and subclonal otherwise. We identified 2,103 clonal and 1,544 subclonal mutations (Table S6) and constructed evolution models (e.g., T1-T3-T5 and, for selected cases, up to T15).74 All models showed a major cluster of co-shared mutations among primaries and PDX (Figures 4F–4H and S4I–S4K), with dominant clones preserved over propagations. Minor subclones branched and expanded along PDX propagations, with some clonal competition (Figures 4F–4H). Finally, we computed Nei’s genetic distances on 22/29 models to estimate clonal drifting along propagation (Figure 4I, 4J, and S4L)75 and defined three subgroups based on low/medium/high evolution rate (average Nei’s score): 14/22 (64%) low (<0.5), 7/22 (32%) median (>0.5 and <1), and only 1/22 (4%) high score (>1). This confirmed the overall stability of PDX compared to different systems (e.g., glioblastoma; Figure S4M).

In sum, PDXs maintain primary-matched pathogenetic drivers and degrees of lymphoma heterogeneity.76

PTCL PDXs recapitulate primary and host microenvironment interactions

To explore the nature of the PTCL tumor microenvironment (TME), we took advantage of our methodology24,77 to extract functional signatures from the crosstalk of TME with cancer cells (functional gene expression signatures [FGESs]) from bulk RNA-seq. We first used 24 FGESs to virtually reconstruct the TME of 845 PTCLs from 16 public datasets and our cohort. We separated them into four major clusters representing “lymphoma microenvironment” categories (Table S7; Figures 5A and S5A–S5E): “B cell rich” for the abundance of B cells and B cell trafficking FGES; “mesenchymal” for over-representation of FGES linked to stromal cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), and ECM remodeling; “inflammatory” for the presence of FGES related to macrophages and NK cells; and “depleted” that overall had the lowest representation of TME FGES. PTCL subgroups were distributed across the four TMEs without specific associations, although each group displayed distinct signatures and bore different genomic defects (Figure S5F). A survival analysis on two distinct PTCL patients’ cohorts (n = 253) showed that the “depleted” TME was associated with poorer prognosis (uncorrected p = 0.005) (Figure 5B). Remarkably, the only FGESs overrepresented in the “depleted” TME cases were related to “Th2-ILs and GATA3 activation” and “proliferation rate” (Figure 5A) and exhibited the highest proportion of tumor cells as determined by mutational load (Figure S5G, p < 0.01 vs. the other categories). Similar data were recently described in an independent PTCL cohort.78 Next, we performed a multiplex imaging analysis of primary PTCL using antibodies recognizing different subtypes of T cells, macrophages, and stromal elements, confirming the RNA deconvolution predictions (Figures 5C and S5H).

Figure 5.

The microenvironment of primary and PDX defines distinct subgroups of PTCLs

(A) Heatmap of the activity scores of 20 FGES and 4 signaling pathways (x axis) denoting four major TME clusters of primary PTCL (n = 845). In each dataset, signatures were median scaled using median and MAD (median absolute deviation) calculated only for samples with AITL or PTCL-NOS. MFP (microenvironment functional phenotype) portraits were predicted by Louvain clustering (with a threshold of closest points 0.25) within 20 signatures. Samples were sorted by MFP and by diagnosis and for each MFP and diagnosis by proliferation rate increasing. The bottom four molecular pathways were calculated by Progeny.

(B) Kaplan-Meier models of OS according to the PTCL TME category.

(C) TME annotation by multiplex analysis of PDX.

(D) Heatmap of the activity scores of 20 FGES (x axis) denoting four major TME clusters of PDX; signature scores (calculated by single sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis - ssGSEA - algorithm) were median scaled for each biopsy site separately taking median and MAD only from AITL and PTCL-NOS samples. Oncoplot below the heatmap depicts mutations, ALK, and EBV status. Color palettes on the top indicate MFP, biopsy site, T-cell phenotype, and diagnosis for each sample.

(E) Left: Sankey plot showing changes in T differentiation throughout primary and three passages of PDX. Right: plot showing changes in MFP subtypes throughout primary and three passages of PDX.

(F) Proportion of macrophages M1 or M2 enriched in PDX by FGES. Error bars represent standard deviations (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(G) The proportion of myCAF enriched in selected PDX subtypes by FGES. Error bars represent standard deviations (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(H) The proportion of iCAF enriched in PDX by FGES. Error bars represent standard deviations (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(I) Barplot of apoptotic lymphoma cells cocultured with and without stromal cells (STCs). Data are representative of three replicates. Error bars represent standard deviations.

(J) Gene Ontology analysis indicates the biological processes enriched in educated vs. not-educated SCTs. Error bars represent standard deviations.

(K) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the top 100 differentially expressed genes in not-educated (cultured in vitro >3 days) and (re)educated (freshly isolated or co-cultured in vitro with PTCL cells >3 days) STCs isolated from PDX.

(L) Percentage of viable IL-2 PDX cells cultured in stress conditions alone (red bar) or cocultured with STCs isolated from different PDXs. Data are representative of three replicates. Error bars represent standard deviations.

(M) Percentage of viable MT05 PDX cells cultured in stress conditions alone (red bar) or cocultured with STCs isolated from different PDXs. Data are representative of three replicates. Error bars represent standard deviations.

(N) Barplots reporting the delta of the specific cell death of PDX-Dlines (IL-2 and IL142A) exposed to 40 drugs with or without STCs (72 h at 1 μM).

(O) Barplot showing viable PTCL PDX cells cocultured with STCs or cultured alone in the presence of targeting agents (72 h). Data are representative of three replicates. Error bars represent standard deviations.

We extended this approach to PDX models, using converted mouse FGES (mFGES), and showed the same four TME categories of primary tumors (Figures 5D and S5F–S5N). Using only human reads, we performed a clustering analysis of the PTCLs into 4 functional “intrinsic” T cell phenotypes: Th1 (mostly AITLs and PTCL-NOS), Tfh (AITL), Th2 (PTCL-NOS carrying JAK-STAT mutations), and cytotoxic (mainly ALCL) (Figure S5F). The Th1 and Tfh group frequently displayed TET2, RHOA mutations, and detectable EBV transcripts. The cytotoxic group had the lowest TCR signaling rate and few normal T cells (Figure S5K), in line with the ALCL low TCR signaling.79 Most samples with high TCR signaling displayed TET2/DNMT and/or RHOA/PCLG1 defects80; meanwhile, ∼50% of those lacking them were EBV+. TCR-negative samples were conversely enriched in JAK1/STAT3 mutants and/or clustered among ALCL.2,79 We next showed that TME cell populations were mostly conserved along PDX passages (Figure 5E), particularly in ALK+ ALCL, which maintained their cytotoxic phenotype, and for most Th2 PDX. Nevertheless, changes were observed, suggesting some plasticity (i.e., “mesenchymal” and “B cell-rich” TMEs; Figures 5E and S5I). A transition to a “mesenchymal” TME was seen in ALCLs whose tumor content rapidly increased after engraftment. Other PDXs displayed a progression to a “B cell-rich” TME (e.g., NY-PTCL-CR, IL33, and IL98), likely driven by an increased number of EBV-LCLs (Figures S5I and S5J).81,82

Additionally, we interrogated murine tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and CAFs, which increased along PDX passages (Figure S5M). Both M1-like and M2-like TAMs expanded in PDX, with an increased M2/M1 ratio (primary:1.53 vs. PDX: 2.27; Figure 5F). Regarding CAFs, signatures corresponding to “myCAF” and “iCAF” (Table S7) were also enriched (Figures 5G, 5H, and S5N).

As a functional validation, murine PDX stromal and tumor endothelial cells improved the survival of cocultured lymphoma cells (Figures 5I and S5O).83,84 Cocultured CAFs upregulated biogenesis, migration, cell mobility, and DNA replication pathways (Figure 5J), mimicking the phenotype of freshly isolated mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs; Figure 5K), a phenotype partially lost when cultured alone. Remarkably, freshly isolated CAFs from matched tumors or in vitro re-educated-CAFs more efficiently rescued PDX under serum deprivation (Figures 5L and 5M). Finally, PDX-CAFs improved the viability of 2 models (IL-2 and IL142A) in co-culture drug screening platforms (Figures 5N and 5O), including compounds targeting PTCL driver pathways (Figure 5O). This effect was only seen with lymphoma-matched PDX-MSCs (Figure S5P), suggesting a lymphoma-specific education. We next identified putative pathways that mediated the host rescue, as depicted in Figure S5Q, where CAF rescue was partially abrogated with crizotinib (navitoclax/ABT263, belinostat, etc). Finally, we found that mouse mesenchymal cells (MS-5) protected ALCL cell lines from brentuximab-vedotin (BV)-induced death (Figure S5R).

Therapeutic responses are assessed in PTCL PDX

We first examined the therapeutic prediction of six PDXs (3 ALK+ ALCLs, 1 PTCL-NOS, and 2 ALK− ALCLs) performing a high-throughput in vitro drug screening (Figure S6A) targeting ∼634 proteins (Table S8; Figure 6A), demonstrating a high reproducibility among replicates (Figure S6B) and along serial propagations (Figures 6A–6C and S6C). Therapeutic responses differed according to the subtype (Figures 6B and 6C). Most compounds had little effect. However, a subgroup of 19 drugs showed higher efficacy across samples (Figure 6C). We then correlated the gene expression profiles with cell viability after drug exposure and identified predictive signatures to belinostat (Figures S6D and S6E) and ruxolitinib (R = 0.97, p = 0.033) (Figures 6D–6G, S6D, and S6F). Next, we expanded the screening to PDX-Dlines with 53 drugs, including the 30 most active compounds within the 433-drug library and 23 drugs from clinical trials (Table S9; Figure 6H), establishing dose-response curves (Figures 6I and S6G). Also, PDX-Dlines displayed individual patterns of responses to the ALK inhibitor (ALKi) crizotinib (TO-ALCL-DN03, ALK+ ALCL) and the JAK inhibitors (JAKi) ruxolitinib, tofacitinib, and cerdulatinib (IL-2, JAK1 mutant; Figure 6H), in line with their genetic alterations. Conversely, cytotoxic chemotherapeutics (daunorubicin, SN38, and vincristine), HDAC inhibitors (romidepsin, and panobinostat), a survivin inhibitor YM155, proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib and CEP18870), an aurora-kinase inhibitor (tozasertib), and a CDK9 inhibitor (AZD-4573) were pan-active, even at low concentrations.

Figure 6.

Ex vivo PDX drug responses

(A) Heatmap showing the magnitude of the cross-correlation of 6 PDX freshly isolated cells exposed to the drug library.

(B) Principal-component analysis (PCA) of 19 PDX freshly isolated cells based on the responses to 433 drugs. Circled dotted lines group together samples of PTCL subtype.

(C) Heatmap showing the responses of 6 PDX models (19 freshly isolated cell samples) to 433 drugs. Dendrograms on the left and bottom show unsupervised hierarchical clustering of drugs and PDX along the axis of maximum variation (ward) for the Euclidean distances. The dot plot denotes the average drug viabilities per PDX across 433 drugs (top). Dot plot shows the average sample viabilities per drug (right).

(D) Dot plots showing the correlation between the expression levels of JAK1 and JAK2 across PTCL subtypes with cell viability after ruxolitinib treatment (72 h, 1 μM). The correlation coefficients and p values are indicated.

(E) Heatmap and unsupervised clustering depicting the gene expression within the JAK-STAT pathway. Genes were selected based on the correlation between the expression and viability of samples treated with ruxolitinib (1 μM, 72 h). The viability values are indicated in the upper color bars.

(F) Heatmap and unsupervised clustering depicting the gene expression from a regression analysis obtained by modeling the cell viabilities as a function of the PTCL subtypes plus each gene expression.

(G) Dot plot showing the predicted vs. actual cell viabilities, with correlation and p value across PTCL subtypes. The prediction derives from the regression analysis in Figure 5F.

(H) Heatmap displaying the response of five PDX-Dlines to 40 compounds. Specific cell death is reported in percentage.

(I) IC50 assessment in five PDX-Dlines treated in vitro with increasing concentrations of compounds (day 3 and 6).

(J) Boxplot indicating the predicted synergy score by the DeepPTCL algorithm for the indicated drug combinations across PTCLs. Error bars represent standard deviations.

(K) Percentage of viable IL-2 and IL142A PDX-DLines cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations of duvelisib and cerdulatinib (IL-2) or duvelisib and venetoclax (IL142A) for 72 h. Data are representative of three replicates. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Seeking drug combination candidates, we developed a deep learning-based algorithm named DeepPTCL (see Methods). Having demonstrated a consensus between the The Cancer Genome Atlas cell lines and PTCL (see Methods; Figure S6H), we screened 8 of the most effective drugs for synergies (irinotecan, romedepsin, duvelisib, pralatrexate, AZD-4573, cerdulatinib, azacytidine, and crizotinib) on PDX-Dlines (IL-2, IL89, IL142A, TO-ALCL-DN03, and TO-ALCL-Belli). DeepPTCL predicted 6 top synergy combinations with duvelisib (Figure 6J), some further validated in vitro (duvelisib/cerdulatinib in JAK1mut IL-2 PDX-Dline and duvelisib/venetoclax in IL-2 and IL142A PDX-Dlines, carrying PTEN and TP53 deletions) (Figure 6K; Figure S6I). Lastly, we linked responses of representative combinations to the mesenchymal TME within the FGES subtypes (Figure S6J).

PTCL PDX pre-clinical trials in vivo

To assess responses to standard and innovative drugs/combinations, we selected 17 PTCL PDXs (10 naive and 7 refractory; Figure 7A; Table S9).

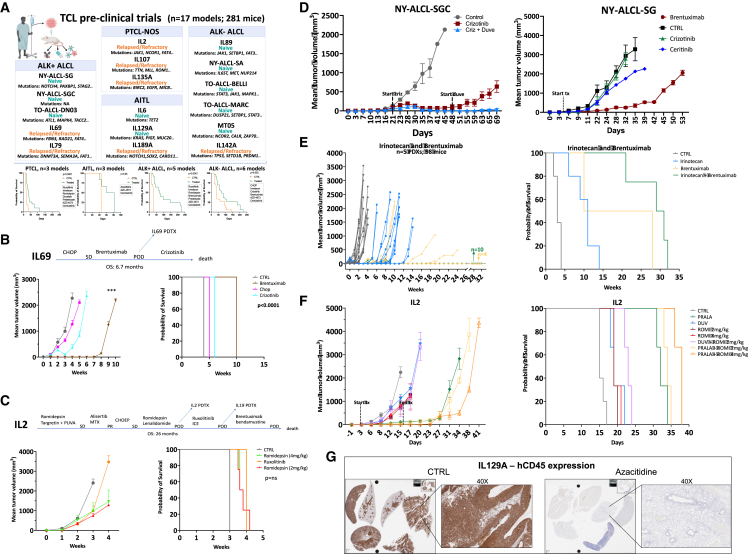

Figure 7.

The mouse hospital and pre-clinical trials

(A) PTCL pre-clinical trials overview and Kaplan-Meier plots representative of the overall survival of PDX models.

(B) Comparison of IL69 patient and matched PDX responses to CHOP, brentuximab, and crizotinib (n = 8–10 mice/group). Top panel: IL69 patient clinical history. Error bars represent standard deviations. p values were estimated with adjusted t test (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001). Kaplan-Meier curve of the OS (right panel, log rank test, p < 0.0001).

(C) Comparison of IL-2 patient and matched PDX responses to ruxolitinib and romidepsin (n = 8–10 mice/group). Top panel: IL-2 patient clinical history. Error bars represent standard deviations. Kaplan-Meier curve of the OS (right panel, log rank test, p = ns: >0.05).

(D) Left panel: antitumoral effect of crizotinib alone or in combination with duvelisib in NY-ALCL-SGC PDX (n = 8–10 mice/group). Right panel: antitumoral effect of crizotinib, brentuximab, and ceritinib in NY-ALCL-SG PDX (n = 8–10 mice/group). Error bars represent standard deviations.

(E) Antitumoral effect of irinotecan, brentuximab, or combination in ALCL PDX (MT05: cutaneous ALCL - cALCL-, IL69, DN03; IL79: ALK+ ALCL; IL-2: PTCL-NOS). Kaplan-Meier curves of the OS (right panel, log rank test, p < 0.0001). Individual biological and technical replicates are depicted as single lines.

(F) Antitumoral effect of pralatrexate, duvelisib, and romidepsin or combinations in IL-2 PTCL-NOS PDX (n = 8–10 mice/group). Error bars represent standard deviations (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001). Kaplan-Meier curves of the OS (right panel, log rank test, p < 0.0001).

(G) hCD45 IHC staining of IL129A PDX treated with vehicle or azacytidine. Left panels: mice organs (lungs, kidney, spleen, liver, and heart). Right panels: lungs (40x).

First, we tested whether PDX recapitulated patients’ responses (Table S10; Figures 7B, 7C, and S7A–S7C) to (1) CHOP, demonstrating that TO-ALCL-DN03 responded in line with the matched patient (partial response, Figures S7D–S7F) while MT05 and TO-ALCL-Marc were refractory as the donor patients, and (2) targeted agents. These latter experiments showed that JAK1mut IL-2 PDX was refractory to ruxolitinib and romidepsin, as its corresponding patient (Figure 7C), and the NPM-ALK+ IL69—derived from a patient refractory to CHOP, BV, and crizotinib—did not also show significant responses (Figure 7B). Similar responses were documented in the IL79 ALK+ ALCL model (Figure S7G). Conversely, the ALKi-naive TO-ALCL-DN03 was eradicated by crizotinib (Figure S7H), while NY-ALCL-SG showed little-to-no response to crizotinib and ceritinib (respectively) but was partially controlled by BV (Figure 7D). For the ALKi-naive NY-ALCL-SGC, we observed a significant response to crizotinib followed by a relapse; this latter phenotype was controlled by the duvelisib-crizotinib combination (Figure 7D).85 As STAT3 powers some ALK− ALCL,69 we treated a naive STAT3+ ALCL PDX with baricitinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, using two different dosing schedules. Growth inhibition was partially achieved in BID-treated mice, demonstrating that prolonged and significant suppression of pSTAT3 is required for improved clinical outputs (Figure S7I).

Afterward, we harnessed multiple PDX to design precision-medicine-driven pre-clinical trials by integrating phenotypic, genomic, and drug screening data. We chose a debulking approach using irinotecan, which was effective in the in vitro screening (Figure 6C), followed by chemo-free approaches (Figures 7E and S7J). Irinotecan has some activity in PTCL patients86 and in relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin patients.87,88,89 In detail, CD30+ ALCL PDX (IL69, IL79, MT05, and DN03) were challenged with irinotecan and BV (Figure 7E), while the IL-2 PTCL-NOS PDX was treated with irinotecan and ruxolitinib (Figure S7J). Combinations either eradicated and/or yielded improvement in survival. Finally, we tested effective in vitro drugs (Figure 6H), either as single agents or in combinations (Figures 7F, S7K, and S7L). Pralatrexate proved to be the most effective, improving OS and, in some cases, leading to lymphoma eradication as a single agent (IL142A, Figure S7K), or in combination with romidepsin (IL-2, Figure 7F) or duvelisib (IL107, Figure S7L). Conversely, azacitidine (Figures 7G and S7M)90,91 decreased lymphoma growth (Figures 7G and S7M–S7P) and prolonged survival (Figure S7P). We next combined CDK9 inhibitor (AZD-4573)92 with cerdulatinib,93 following a 1 × 1 × 1 pre-clinical design,26 in 9 PDXs (Figure 8A). As a single agent, cerdulatinib showed a modest effect in 3/9 models and significant readouts in only 2/9 models. AZD-4573 was more potent, with a modest effect in 2/9 and superior response in 4/9 models (Figures 8A–8C and S8A). Their combination yielded improved responses in 5/9 models, extending survival (pairwise log rank p = 0.019) (Figures 8C, S8A and S8B). By bulk RNA-seq, we observed that non-responders had an upregulation of TCR signaling, and conversely, responders were enriched in genes regulating migration, cytoskeleton, and cell interactions (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

PDX pre-clinical trials support the implementation of drug combinations and immune-based regiments

(A) Swimmer plot of PDX models (n = 9 and 36 mice) treated with vehicle, cerdulatinib, AZD-4573, or combination.

(B) Barplot depicting PDX tumor size across time points (vehicle, cerdulatinib, AZD-4573, and combination). p values were calculated with one-way ANOVA with adjustment for multiple comparisons ∗: p < 0.05.

(C) Kaplan-Meier plots of the global OS of PDX models (n = 9 and 36 mice; log rank test, p = 0.017).

(D) Heatmap depicting the top differentially expressed genes in PDX model responders and not-responders to AZD-4573 in vivo treatment.

(E) Flow cytometry analysis of TO-ALCL-DN03 (above panels) and IL-2 (below panels) PDX-Dlines cocultured with CART30 cells at the indicated target (red dots)-to-effector (green dots) ratio.

(F) Antitumoral effect of CART5 cells alone or combinations with nivolumab in IL-2 PTCL-NOS PDX (n = 6–10 xenografts/group). Error bars represent standard deviations.

(G) Antitumoral effect of CART30 cells alone or combinations with nivolumab in NY-ALCL-SG ALK+ALCL PDX (n = 6–10 xenografts/group). Error bars represent standard deviations.

(H) Detection of untransduced - UTD -and CART30 within the peri-tumor and tumor masses (CART30 is depicted in green and NY-ALCL-SG cells in red).

(I) Multiparametric analysis demonstrates the positive PDL1 expression of NY-ALCL-SG (red color), and CD2 (green) and PD1 (low/partial white) of CART30 cells.

Lastly, we assessed the efficacy of CAR-T in PTCL PDX, a still largely unexplored field.94,95 We took advantage of two CART products specifically targeting CD30 or CD5 (CART30 and CART5, respectively), the latter engineered to lack endogenous CD5 expression, avoiding fratricide effects and with enhanced antitumor activity (see Methods96). Both products were effective in vitro (CART5 against IL-2, a PTCL-NOS, and CD5+/CD30− and CART30 against TO-ALCL-DN03, an ALK+ALCL, and CD30+/CD5−) (Figures 8E, S8C and S8D). In vivo, CART5 controlled lymphoma growth, especially in combination with nivolumab (Figure 8F). Meanwhile, CART30 or CART30/nivolumab combination showed a partial effect (Figure 8G). This was likely due to a defective intratumoral infiltration (Figures 8H and S8E) and disrupted crosstalk, as shown by multiplex imaging. Indeed, ALCL cells were strongly PDL1+, largely excluding PD1+ and EOMES+ CART at lymphoma periphery (Figure 8I) and distant locations (i.e., spleen; Figure S8F).

Discussion

This study establishes the largest available PDX biorepository for PTCL, offering a robust pre-clinical resource to study tumor evolution, drug resistance, and personalized therapies. PDXs faithfully replicate primary tumor characteristics, including histopathology, clonality, genomic, transcriptomic, and drug susceptibility, making them an invaluable resource for understanding PTCL pathogenesis.

PDX fidelity and drifting along propagation are still a matter of debate.30,33,97 Here, we proved that PDXs closely matched primary samples, displaying identical TCR rearrangements and retaining the same driver mutations/copy-number variation (CNV) and gene expression patterns. Nevertheless, distinct subclones were detectable with the acquisition of non-random defects in a stepwise fashion (i.e., loss of TET2 and DNMT3a) and the acquisition of mutations (i.e., RHOA, IDH2, or NOTCH1/4 in ALCL and AITL PDX). This supports the model of stepwise T cell transformation, defining preferential trajectories/pathways driven by intrinsic defects. These findings feature the relevance of PTCL PDX to inform the potential evolutionary trajectory of human tumors. Along the same lines, we discovered genomic aberrations (e.g., ACADVL-VAV1 and MAZ-NF1) converging on specific pathways and propelling T cell transformation. These findings support the implementation of agents selectively targeting downstream effectors (STAT3, IRF4 PROTACs, etc.). Strikingly, PTCL PDX and PDX-Dlines maintained a significant subclonal heterogeneity, a feature often lost by conventional cell lines, providing a better representation and higher predictive power.17,98 We took advantage of this predictive potential by comparing, via a deep learning model, PTCL PDX transcriptional signatures with those of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia, to in silico predict and in vitro validate drug combinations.

Personalized treatments require cancer genomic stratification,99,100 providing a more granular landscape and pinpointing the role of the microenvironment.24,101 Here, we proved that PTCL and matched PDX can be stratified by microenvironment functional signatures (FGESs) derived by lymphoma-host cognate interactions. This stratification is of prognostic relevance, with the “Th2” subgroup (so-called Th2/GATA3, over-activating the PI3K pathway) bearing the most unfavorable outcome. Similar data were recently presented in an independent cohort.78 Strikingly, despite the paucity of the PDX microenvironment, the host elements’ compositions somehow recapitulated the PTCL landscapes, supporting a model predicting the education of the host by lymphoma elements.102,103,104,105 PDX cells could also instruct stromal remodeling in vitro, establishing prosurvival niches with drug-counteracting capabilities. This model allows the functional validation of host-mediated protumorigenic mechanisms and testing of ad hoc regimens strategies.106,107,108 Considering the limited array of intrinsic druggable liabilities, we believe that targeting the lymphoma microenvironment will become of pivotal importance in future studies.

Finally, PDXs are emerging as a powerful tool in clinical oncology for investigating rare tumors and neoplasms,109,110,111 such as PTCL.12,17 We believe that the future/systematic generation of PDX from patients enrolled in clinical trials will allow the direct comparison of PDX and patients’ responses, faster PDX-based predictions, and the possibility to assign/switch patients to the most effective therapeutic arms.32,111 Here, we performed pre-clinical trials using experimental drugs (mostly derived from drug screening approaches and/or in silico predictions) and proved their efficacy as single agents or combinations. Also, we proved that immune-based CAR-T strategies (CD5KO-CART5 and CART30) can be explored and validated in PTCL PDXs.

In summary, PDXs provide a compelling opportunity to foster the translation of drug and immune-based strategies from the bench to the bedside.24,112 Our biorepository provides a resource for PTCL research and serves as a pre-clinical platform for testing novel therapies. By integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and drug response data, this study advances precision medicine for PTCL patients.

Limitations of the study

Despite the significance of our findings, several limitations must be acknowledged.

Limited immune system representation

PDX models lack a functional immune system,25,111 limiting the evaluation of immunotherapies, including CAR-T and checkpoint inhibitors. Thus, studies should explore humanized mouse models to address this limitation.

Engraftment success varies

∼36% of PTCLs successfully engrafted, with lower rates for rare subtypes. We believe that tissue availability and technical (tissue amount/appropriateness) and biological features of rare lymphomas (individual and heterogeneous genotypes and host requirements) partially explain these failures.113,114 To improve success, we employed b2/MCH class I-class II knockout mice to lessen graft versus host disease (GVHD)-like reactions, which can jeopardize engraftments.115 Further optimization (e.g., IL15-NSG mice) did not improve NK/T PTCL engraftment, demonstrating that defined/multiple signals are required, hardly overcome by individual engineered models. We found liability in the emergence of EBV-transformed cells116 (especially in AITL), rarely controlled by anti-CD19-ADC (Antibody-Drug Conjugate) or rituximab in NSG Hc1 mice, in contrast to previous studies with solid cancers.117,118 This predicts that EBV+ and/or B cells may not be simply bystander elements but can contribute to the early stage of transformation and/or sustain lymphoma growth/survival.119 This model is in line with the EBV-peptide recognition (EBNA LMP1 etc.) by lymphoma/leukemia TCR/MHC class I complex and TCR triggering. These data extend the putative pathological role of B cells in the genesis and maintenance of AITL.120

Microenvironment changes over passages

While PDXs retain key tumor features, some human host components diminish over serial passages, affecting tumor-host interactions. Nevertheless, as for other PDXs,24,121,122, functional similarities between human and mouse TME and the protumorigenic role of CAFs were observed. Future work taking advantage of co-culture systems and engineered microenvironments is required to dissect the mechanisms of action.

Deep learning therapy prediction requires validation

The DeepPTCL algorithm successfully predicted effective drug combinations, fostering future (pre)clinical studies in patients before entering into clinics.

Clinical translation of PDX findings

While PDX drug responses nicely correlated with patient outcomes, the implementation of PDX in prospective clinical trials is needed for the translatability of our findings. We hope that new clinical trials will include the utilization of patients’ samples for the generation of PDX and, thus, the future design and validation of broader PTCL therapeutic strategies.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Giorgio Inghirami (ggi9001@med.cornell.edu).

Materials availability

Biobanked PDXs are cataloged by the Center for Technology Licensing (https://innovation.weill.cornell.edu) and can be requested. Distribution of PDX and derived cell lines to third (academic or commercial) parties requires completion of a material transfer agreement and must be authorized by the medical ethical committee of Weill Cornell Medicine (WCM) at request of the HUB to ensure the compliance with the Institutional Review Board-Research at the WCM research involving human subjects’ act. Use of PDX is subjected to patient consent; upon consent withdrawal, distributed PDX and any derived material will have to be promptly disposed of.

Data and code availability

-

•

Raw sequencing data have been deposited to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) and are publicly available. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table (WES: PRJNA1198080; RNA-seq: PRJNA1214670; scRNA-seq: PRJNA1218277). Also, this paper analyzes existing, publicly available data, whose accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Codes used in this study are deposited at https://github.com/marchionniLab/ing-2023 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14847458) and https://github.com/Mew233/DeepPTCL (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14845644) and listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank all staff members of the Immunopathology Laboratory at Weill Cornell Medicine for their support. We are grateful to the Epigenomics and Genomics Cores of Weill Cornell Medicine for next-generation sequencing. We thank the members of the Weill Cornell Cell Sorting Core and Edward Meyer Cancer Center PDX Shared Resource. We thank Drs. Lorenzo Galluzzi and Shahin Rafii for intellectual discussions, feedback, and support. We thank the mouse facility operators and Drs. Kvin Lertpiriyapong and Rodolfo Ricart Arbona. We are grateful to Ani Arkur, Sofia Alayon, and Shefali B. Sha for their administrative support and financial management. G.I. is supported by CA229086, CA229100, CA195568, and LLS 7011-16; L.V.C. and R.F. were supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research, Metastases 5x1000 Special Program, grant 21198; L.V.C. and G.Medico were supported by American-Italian Cancer Foundation Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship (AICF 2021-22 and 2023-24); D.F. was supported by the Rita-Levi Montalcini grant from the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR); V.F. was supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research, MFAG 2023 ID 28974; and D.M.W. was supported by NCI R35 CA231958, NCI P01 CA233412, and Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Specialized Center of Research 7026-21. R.R., A.W., and L.Z. were supported by NCI R35 CA253126, U01CA243073, and Stand Up to Cancer Convergence Program. L.Z. was supported by the NSFC 32170565 and the CAS Hundred Talents Program. W.C.C. was supported by the COH Cancer Center Support Grant P30, CA033572, and 1PO1CA229100.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: D.F., L.V.C., R.P., E.M., S.Y.N., A.M., Z.E., A.I., D.A., P.M., J.R., F.B., R.F., J.D.B., D.B., W.T., D.M.W., L.C., R.R., S.H., and G.I. Methodology and investigation: D.F., L.V.C., J.P., A.T., W.C., V.F., F.T., N.Z., C.K., G.Medico, R.P.P., M.G., R.M., G.A., M.T.C., G.Z., C.P., R.A.E., S.P., N.D.S., and I.K. Software and formal analysis: L.Z., N.K., P.G., M.S., P.Z., L.Y., A.W., X.H., A.N., O.K., D.Nikitin, D.T., E.P., A.B., A.K., E.B., V.S., K.T., N.D.S., S.D., G.Macari, L.C., S.G., L.S., J.O., C.Z., L.Q., O.E., and C.X. Resources: D.Novero, M.P., E.T., B.F., A.M., F.Z., J.S., E.D.S., Z.E., D.A., P.M., J.R., J.D.B., W.C.C., W.T., M.R., D.M.W., S.H., and G.I. Writing original draft: D.F., L.V.C., W.T., L.C., and G.I. Writing, reviewing, and editing: D.F., L.V.C., W.T., L.C., and G.I. Funding acquisition: D.F., S.H., D.M.W., R.F., and G.I. Project administration: G.I.

Declaration of interests

D.M.W. is an employee of Merck and has an equity interest in Ajax, Bantam, and Travera. F.B. receives institutional research funds from ADC Therapeutics, Bayer AG, Cellestia, Helsinn, HTG Molecular Diagnostics, ImmunoGen, iOnctura, Menarini Ricerche, NEOMED Therapeutics 1, Nordic Nanovector ASA, and Spexis AG; advisory board fees from Novartis; consultancy fee from Helsinn and Menarini; and travel grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, and iOnctura and provided expert statements to HTG Molecular Diagnostics.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-CD3e conjugated to FITC (clone 17A2) | BD Bioscience | 349201; RRID: AB_395698 |

| anti-CD57 conjugated to PE (clone B3GAT1) | BD Bioscience | 560844; RRID:AB_2033965 |

| anti-CD5 conjugated to PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone L17F12) | BD Bioscience | 341099; RRID: AB_400220 |

| anti-CD4 conjugated to PE-Cy7 (clone SK3) | BD Bioscience | 348799; RRID: AB_400387 |

| anti-CD7 conjugated to APC (clone 124-1D1) | Invitrogen | 17-0079-42; RRID: AB_10671279 |

| anti-CD8 conjugated to APC-H7 (clone SK1) | BD Bioscience | 641409; RRID: AB_1645737 |

| anti-CD2 conjugated to BV421 (clone TS1/8) | BioLegend | 309216; RRID: AB_2073669 |

| anti-CD45 conjugated to V500C (clone 2D1) | BD Bioscience | 647450; RRID: AB_2814897 |

| anti-TCRa/b conjugated to FITC (clone WT31) | BD Bioscience | 340883; RRID: AB_400168 |

| anti-TCRg/g conjugated to PE (clone 111F2) | BD Bioscience | 347907; RRID: AB_400359 |

| anti-CD56 conjugated to PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone B159) | BD Bioscience | 560842; RRID: AB_2033964 |

| anti-CD3 conjugated to PE-Cy7 (clone SK7) | BD Bioscience | 341101; RRID: AB_400222 |

| anti-CD30 conjugated to APC (clone HRS4) | Beckman Coulter | A87939; RRID: N/A |

| anti-CD25 conjugated to APC-H7 (clone M-A251) | BD Bioscience | 560244; RRID: AB_1645472 |

| anti-CD16 conjugated to BV421 (clone 3G8) | Biolegend | 302032; RRID: AB_2104003 |

| anti-CD7 conjugated to FITC (clone M-T701) | BD Bioscience | 340699; RRID: AB_400100 |

| anti-CD185 conjugated to PE (clone J252D4) | Biolegend | 356904; RRID: AB_2561813 |

| anti-CD278 conjugated to PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone C398.4A) | Biolegend | 313518; RRID: AB_10641280 |

| anti-CD10 conjugated to APC (clone HI10A) | BD Bioscience | 340923; RRID: AB_400543 |

| anti-CD279 conjugated to BV421 (clone MIH4) | BD Bioscience | 565935; RRID:AB_2739399 |

| anti-CD5 conjugated to BV605 (clone UCHT2) | BD Bioscience | 563945; RRID: AB_2738500 |

| anti-Kappa conjugated to FITC (Rabbit anti-Human) | Agilent | FO434; RRID: N/A |

| anti-Lambda conjugated to PE (rabbit anti-Human) | Agilent | RO437; RRID: N/A |

| anti-CD23 conjugated to PE-Cy7 (clone M-L233) | BD Bioscience | 561167; RRID: AB_10611996 |

| anti-CD20 conjugated to APC-H7 (clone L27) | BD Bioscience | 641405; RRID: AB_1645729 |

| anti-CD19 conjugated to BV421 (clone HIB19) | BD Bioscience | 562440; RRID: AB_11153299 |

| anti-ALK-1 | Leica Biosystems | PA0831; RRID: AB_3073618 |

| anti-CD30 (clone BerH2) | Dako | GA602; RRID: AB_3675588 |

| anti-CD3 (clone PS1) | Leica Biosystems | NCL-CD3-PS1; RRID: AB_442061 |

| anti-CD2 (clone AB75) | Leica Biosystems | NCL-CD2-271; RRID: AB_442057 |

| anti-CD4 (clone 4B12) | Leica Biosystems | PA0371; RRID: AB_10554438 |

| anti-CD7 (clone LP15) | Novocastra | NCL-L-CD7-580 P; RRID: N/A |

| anti-CD5 (clone 4C7) | Novocastra | NCL-L-CD5-4C7; RRID: N/A |

| anti- TIA1 (clone 2G9A10F5) | Immunotech | IM2550; RRID: AB_131704 |

| anti-granzyme (clone GrB7) | Monosan | MON7029C; RRID: N/A |

| anti-perforin (clone 5B10) | Lab Vision | MS-1834-R7; RRID:AB_149381 |

| anti- TCRa/b (clone IP26) | Biolegend | 306718; RRID: AB_10612569 |

| anti-CD20 (clone L26) | Dako | M0755; RRID: AB_2282030 |

| anti-PAX5 (clone 24/PAX5) | BD Transduction Lab | 610863; RRID: AB_398182 |

| anti-CD25 (clone 4C9) | Leica Biosystems | PA0306; RRID: AB_10556556 |

| anti-CLA (rabbit polyclonal) | Dako | A 0423; RRID: AB_2335700 |

| anti-OCT2 (rabbit polyclonal) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-56822; RRID: AB_784955 |

| anti-CD33 (clone PWS44) | Leica Biosystems | PA0558; RRID:AB_10555285 |

| anti-MIB (clona MIB-1) | Agilent | GE020; RRID: N/A |

| anti-GAS1 (clone C-17) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | N/A |

| anti-pSTAT3 (clone M9C6) | Cell Signaling Technology | 4113; RRID: AB_2198588 |

| anti-C/EBP (C19) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-150; RRID: AB_2260363 |

| anti-NFATC2 (clone M20) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-1151; RRID: AB_632026 |

| anti-pJAK2 (clone E132) | abcam | ab219728; RRID: N/A |

| anti-pJAK3 (rabbit polyclonal) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-16567; RRID:AB_2128682 |

| anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) | Cell Signaling Technology | 9102; RRID: AB_330744 |

| anti-GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology | 5174s; RRID: AB_10622025 |

| anti-CD2 | Leica Biosystems | AB75; RRID: AB_2528815 |

| anti-CD30 | Agilent | BERH2; RRID: AB_10670808 |

| anti-PDL1 | Roche | SP263; RRID: AB_2819099 |

| anti-EOMES | eBioscience/Invitrogen/Thermo | WD1928; RRID: AB_2572615 |

| anti-CD3 (clone SP7) | Lab Vision | RM-9107-S; RRID: AB_149922 |

| anti-CD68 (clone KP1) | Agilent | IR609; RRID: N/A |

| anti-CD163 (clone 10D6) | Leica Biosystems | NCL-L-CD163, RRID:AB_2756375 |

| anti-SMA (clone 1A4) | Agilent | M0851; RRID: AB_2223500 |

| anti-CD20 (clone L26) | Leica Biosystems | NCL-L-CD20-L26; RRID:AB_563521 |

| DAPI | Cell Signaling Technology | 4083S |

| Biological samples | ||

| PTCL Patient Samples | Weill Cornell Medicine, New York PresbyterianHospital (NY), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (NY), City of Hope (CA), The Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai, University of Torino (IT), San Raffaele (IT). | WCM IRB: 1302013582, 0107004999, 1410015560; MSKCC IRB: 13–014, 09–141, 12–245, 06–107; University of Torino: 0081521 |

| Healthy Peripheral blood mononuclear cells | New York Blood Bank | Custom Order |

| Tissue Blocks of human PTCL | as described in Crescenzo et al., 2015 | 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.006 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| 17AAG | Selleckchem | S1141 |

| ABT-199 | Selleckchem | S8048 |

| ABT263 | Selleckchem | S1001 |

| AUY922 | Selleckchem | S1069 |

| Azacytidine | Selleckchem | S1782 |

| AZD4573 | Selleckchem | S8719 |

| Belinostat | Selleckchem | S1085 |

| Bortezomib | Selleckchem | S1013 |

| Brentuximab vedoton | Boc Science | 914088-09-8 |

| CC220 | Selleckchem | S8760 |

| CEP18870 | Selleckchem | S1157 |

| Cerdulatinib | Selleckchem | S3566 |

| Ceritinib | Selleckchem | S4967 |

| Chidamide | Selleckchem | S8567 |

| CHIR124 | Selleckchem | S2683 |

| Crenolanib | Selleckchem | S2730 |

| Crizotinib | Selleckchem | S1068 |

| Cyclophosphamide | Selleckchem | S2057 |

| Daunorubicin | Selleckchem | S3035 |

| Decitabine | Selleckchem | S1200 |

| Dexamethason | Selleckchem | S5956 |

| Doxorubicin | Selleckchem | S1208 |

| Duvelisib | Selleckchem | S7028 |

| Enzastaurin | Selleckchem | S1055 |

| Ganetespib | Selleckchem | S1159 |

| GDC-0077 | Selleckchem | S8668 |

| Idelalisib | Selleckchem | S2226 |

| Irinotecan | Selleckchem | S1198 |

| KPT330 | Selleckchem | S7252 |

| Lenalidomide | Selleckchem | S1029 |

| MK1775 | Selleckchem | S1525 |

| MLN2238 | Selleckchem | S2180 |

| NSC319726 | Selleckchem | S7149 |

| NVP742 | Selleckchem | S1088 |

| Ouabain | Selleckchem | S4016 |

| Panobinostat | Selleckchem | S1030 |

| PomalidomideS1567 | Selleckchem | S1567 |

| Prednisone | MedChemExpress | HY-B0214 |

| Pralatrexate | Selleckchem | S1497 |

| PU-H71 | Selleckchem | S8039 |

| RGFP-966 | Selleckchem | S7229 |

| RO4929097 | Selleckchem | S1575 |

| Romidepsin | Selleckchem | S3020 |

| Ruxolitinib | Selleckchem | S1378 |

| SC144 | Selleckchem | S7124 |

| Selumetinib | Selleckchem | S1008 |

| Semagacestat | Selleckchem | S1594 |

| SN38 | Selleckchem | S4908 |

| Stattic | Selleckchem | S7024 |

| Tozasertib | Selleckchem | S1048 |

| TGR1202 | Selleckchem | S8194 |

| Tofacitinib | Selleckchem | S2789 |

| TSA | Selleckchem | S1045 |

| Valemetostat | Selleckchem | S8926 |

| Vincristine | Selleckchem | S9555 |

| YKL-5-124 | Selleckchem | S8863 |

| YM155 | Selleckchem | S1130 |

| Ficoll-Paque PLUS | Cytiva | 17144003 |

| Trypan Blue | Sigma Aldrich | T10282 |

| RPMI 1640 Medium | Gibco™ | 11875093 |

| DMEM Medium | ThermoFisher Scientific | C11965092 |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (1X) | ThermoFisher Scientific | 20021–027 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum; Heat inactivated | Corning | 35-011-CV |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) 0.5M | VWR | E522-100ML |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin-Glutamine (100X) | Gibco/Invitrogen | 15140–122 |

| Normocin | Invivogen | ant-nr-1 |

| Gemcitabine | Selleck Chemicals | S1714 |

| Mitomycin C | Sigma-Aldrich | M4287 |

| 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA | Gibco™ | 25200056 |

| Collagenase Type IV | Sigma-Aldrich | C5138-5G |

| Accutase cell dissociation reagent | ThermoFisher Scientific | A1110501 |

| Cell strainer, 100μm, filter | Corning | 431742 |

| Cell strainer, 70μm, filter | Corning | 431751 |

| Cell strainer, 40μm, filter | Falcon, Fisher Scientific | C352340 |

| Recombinant Human IL-2 | R&D systems | 202-IL |

| Recombinant Human IL-7 | R&D systems | 207-IL-025 |

| Recombinant Human IL-15 | R&D systems | 247-ILB |

| DNase I | Worthington Biochemical | LS002007 |

| LB agar Lennox | Gibco | 244520 |

| Trizol | ThermoFisher | 15596018 |

| SYBR™ Select Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | 4472897 |

| EBER probes | Leica | ISH5687-A |

| CellTrace™ CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit | Invitrogen | C34554 |

| CellTrace™ Violet | Invitrogen | C34557 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| SureSelect Strand-Specific RNA Library Agilent Preparation Kit | Agilent | G9691A |

| TruSeq® Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Human/Mouse/Rat | Illumina | 20020597 |

| SureSelectXT Human All Exon 50 Mb v4 Kit | Agilent | 5190–4632 |

| SureSelectXT Human All Exon 50 Mb v5 Kit | Agilent | 5190–6209 |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Qiagen | 69504 |

| RNeasy Mini kit | Qiagen | 74106 |

| Qubit dsDNA HS and BR Assay Kits | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Q32851 |

| Bio-Rad protein assay kit | Bio-Rad Laboratories | 5000001 |

| PCR Mycoplasma Detection Kit - Quantity: 100 Reactions | Applied Biological material | G238 |

| CD3 MicroBeads, human | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-097-043 |

| CD19 MicroBeads, human | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-050-301 |

| TCRB Gene Clonality Assay | Invivoscribe | 12050011 |

| IGH + IGK B-Cell Clonality Assay | Invivoscribe | 11000031 |

| Chromium™ Next GEM Single Cell 5′ Library and Gel Bead Kit v1.1 | 10x Genomics | 1000165 |

| Chromium™ Single Cell 5′ Library Construction Kit | 10x Genomics | 1000020 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw Data Files from RNA-seq | This paper - SRA | SRA: PRJNA1214670 |

| Raw Data Files from WES | This paper - SRA | SRA: PRJNA1198080 |

| Raw Data Files from scRNASeq | This paper - SRA | SRA: PRJNA1218277 |

| WES data | Nat Genet Da Silva Almeida 2015 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.3442#Sec17 |

| WES data | Nat Genet Sakata-Yanagimoto 2014 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.2872#Sec24 |

| WES data | Nat Genet Choi 2015 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.3356#Sec34 |

| WES data | Mod Pathol 2020 Laginestra | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6994417/ |

| WES data | Nat Genet Kataoka 2015 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.3415#Sec45 |

| WES data | Frontiers in Oncology Mirza 2020 | https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.00514/full |

| WES data | Nat Genet Jiang 2015 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.3358 |

| WES data | Cancer Cell Crescenzo 2015 | https://www.cell.com/cancer-cell/fulltext/S1535-6108(15)00094-X#secsectitle0015 |

| WES data | Palomero, Nat Genet. 2014 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.2873#Sec26 |

| Targeted genomic | Schatz, Hortwitz, Weinstock Leukemia 2014 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4286477/table/tbl1/?report=objectonly |

| Targeted genomic | Yoshida, Weinstock Blood 2020 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7180081/ |

| Targeted genomic | Nat Genet Sakata-Yanagimoto 2014 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.2872#Sec24 |

| Targeted genomic | Kataoka, Nat Genet. 2015 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.3415#Sec44 |

| Targeted genomic | Nat Genet Jiang 2015 | https://www.nature.com/articles/ng.3358 |

| Targeted genomic | Cancer Cell Crescenzo 2015 | https://www.cell.com/cancer-cell/fulltext/S1535-6108(15)00094-X#secsectitle0015 |

| RNA_Sequencing data | EGA | EGA: EGAS00001001296 |

| RNA_Sequencing data | dbGaP | dbGaP: phs000689 |

| RNA_Sequencing data | SRA | SRA: SRP049695 |

| RNA_Sequencing data | SRA | SRA: SRP029591 |

| RNA_Sequencing data | SRA | SRA: SRP099016 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE58445 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE45712 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE19069 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE90597 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE6338 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE36172 |

| RNA_Targeted data | EMBL-EBI | EBI: E-TABM-783 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE65823 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE118623 |

| RNA_Targeted data | EMBL-EBI | EBI: E-TABM-702 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE78513 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE51521 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE14317 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE80631 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE19067 |

| RNA_Targeted data | NCBI GEO | GEO: GSE20874 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| TO-ALCL-Belli PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| TO-ALCL-DN03 PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| TO-ALCL-MARI PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL2 PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL69 PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL79 PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL86 PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL89 PDX-Dline | Fiore, Cappelli et al. Cancers 2020123 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32560455/ |

| IL104 PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL135A PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL142A PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL 223B PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| IL 228 PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| COH1 PDX-Dline | This paper | N/A |

| MS-5 cell line | DSMZ | ACC 441 |

| SUPM2 cell line | DSMZ | ACC 509 |

| L82 cell line | DSMZ | ACC 597 |

| MAC1 cell line | Expasy | CVCL_H631 |

| TLBR1 cell line | DSMZ | ACC 904 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ | The Jackson Laboratory | 5557 |

| NOD.Cg-B2mtm1Unc Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ | The Jackson Laboratory | 10636 |

| NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid H2-K1b-tm1Bpe H2-Ab1g7-em1Mvw H2-D1b-tm1Bpe Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ | The Jackson Laboratory | 025216 |

| NOD.Cg-Hc1 Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ | The Jackson Laboratory | 030511 |

| Patient-derived xenografts (PDX) | This paper | Table S1 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for RTqPCR | This paper | Table S12 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Excel 2016 | Microsoft | https://www.office.com/ |

| GSEA (4.1.0) | Subramanian et al. 2005 | https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp |

| Halo | Indica labs | https://www.indicalab.com |

| STARTRAC | Zhang et al., 2018b | https://github.com/Japrin/STARTRAC |

| STAR aligner v2.6.1 | Dobin et al., 2013 | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR |

| DiVa V8.0.1 | BD Biosciences | https://www.bdbiosciences.com/en-eu/products/software/instrument-software/bd-facsdiva-software |

| FlowJo v10.7.1 | FlowJo, LLC | N/A |

| R v4.3.1 | R Core Team, 2014124 | https://www.r-project.org |

| CIBERSORT | Newman et al., 2015 | https://cibersort.stanford.edu/ |

| Seurat v.4.0.3 | Stuart et al., 2019 | https://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| BLAST | Altschul (1990) | ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/blast=/LATEST |

| ImageJ Software | Open source | N/A |

| GraphPad Prism software version 9.3.1 | GraphPad Software, Inc. | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| IGV | Robinson et al., 2011 | http://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/ |

| Kassandra code | Zaitsev et al.77 | https://github.com/BostonGene/Kassandra |

| Shiny v1.7.4 | R Studio Partners, R Core Team 2019125 | https://www.r-project.org/nosvn/pandoc/shiny.html |

| Tidyverse v1.3.9 | vignettes/paper.Rmd126 | https://www.tidyverse.org/packages/ |

| Bioconductor v3.17 | Huber et al. 2015127 | https://www.bioconductor.org |

| Paper code #1 | This paper | https://github.com/marchionniLab/ing-2023 - https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14847458 |

| Paper code #2 | This paper | https://github.com/Mew233/DeepPTCL - https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14845644 |

| Other | ||

| Clinical Annotations | This paper | Table S1 |

| BD FACSCanto™ II | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| BD LSR Fortessa | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| LSRII | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| BD FACSAriaTM III Cell Sorter | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| BD FACSCelestaTM Cell Analyzer | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| NovaSeq 6000 | Illumina | N/A |

| TissueLyser II | Qiagen | 85300 |

| Leica Bond-III | Leica instruments | N/A |

| Leica Bond-RX | Leica instruments | N/A |

| Rodent diet | PicoLab Rodent Diet 20 | 5053 |

| Ventilated cages | N/A | N/A |

| Mouse hair removal kit | 3 M | 9667L |

| Gauze Sponges | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 13-761-52 |

| VWR® Dissecting Scissors, Sharp Tip, 41/2″ | VWR | 82027–578 |

| VWR Dissecting Forceps | VWR | 89259–944 |

| Isoflurane chamber with nose cone | N/A | N/A |

| Wound Clip Complete Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | BD427638 |

| 1 mL syringe | VWR | 76124–644 |

| 5 mL syringe | VWR | 76163–596 |

| Animal Ear Punch, Plier-Style | VWR | N 10806-290 |

| Freezing container | VWR | 55710–200 |

| 50mL Falcon Tubes | VWR | CA21008-940 |

| Sterile Petri Dish | VWR | 25384–342 |

| Scalpel with blade no. 10 | VWR-Miltex | 21909–654 |

| Sterile razor | VWR | 55411–050 |

| 2mL Serological Pipette | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 170365 |

| 5mL Serological Pipette | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 170355 |

| 10mL Serological Pipette | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 170367 |

| 25mL Serological Pipette | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 170357 |

| Alcohol pad | VWR | 720–2586 |

| Puralube® Ophthalmic Ointment | Patterson veterinary | 211–38 |

| Sutures: Dermalon Suture, Blue, Size 5/0, 18″, CE-4 Needle | Medline | D-G175621 |

| Insulin Syringes | VWR | BD328438 |

| RAM Scientific Safe-T-Fill™ Capillary Blood Collection Systems: Lithium Heparin | ThermoFisher | 14-915-65 |

| Lab animal scale | N/A | N/A |

| Digital caliper | VWR | 36934–152 |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO2) | N/A | N/A |

| Isoflurane | N/A | N/A |

| Feeding gavage needles | braintreescientific | N-VP 22G-15S |

| Mouse Tail Illuminator Restrainer | braintreescientific | MSPP-MTISTD |

| Matrigel | Corning | 354234 |

| Trocar for mouse surgery | braintreescientific | TRO 14MS |

| Surgical Scrub Betadine | Purdue Products LP | 6904214–40890 |

| Betadine Iodine Solution | Purdue Products LP | 158348 |

| Meloxicam | Boeringer Ingelheim | L20805A-42 |

| Tear gel | Optixcare Eye Lube | BP231-1 |

| Ethyl Alcohol Anhydrous | Commercial Alcohols | PO16EAAN |

Experimental model and study participant details

Human study

The collection of PTCL patient data and tissue for the generation and distribution of PDX and derivatives were performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board-Research at the Weill Cornell Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Privacy Board and the Comitato Etico Interaziendale, AOU San Giovanni Battista di Torino and CTO Maria Adelaide di Torino. All patients participating in the study signed informed consent forms approved by the authority responsible (see above). In all cases, patients can withdraw their consent at any time, leading to the prompt disposal of their tissue and any derived material. Biobanked Patient-Derived models can be requested at https://innovation.weill.cornell.edu. Clinical information is available in Table S1. Additional data i.e., age, gender, genetics, therapy, etc. of subjects can be inquired through https://innovation.weill.cornell.edu.

Pathological samples most frequently from diagnostic tissue samples (76/88), and some from bone marrow (3/88), pleural effusions (2/88), or peripheral blood (7/88) were collected at the Weill Cornell Medicine (WCM) of New York, University of Torino, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Both fresh (n = 54) and viably cryopreserved tissue samples were implanted (n = 34). Diagnoses were assigned according to the WHO classification by expert pathologists. De-identified patients’ samples (323) were obtained with informed consent under WCM (78), Torino (6), MSKCC (234), S. Raffaele at Milan (1), City of Hope (3), and Mount Sinai (1) Institutional Review Boards (IRB)-approved protocols, according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Mice models

NOD Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG), NOD.Cg-B2mtm1Unc Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG B2m), NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid H2-K1b-tm1Bpe H2-Ab1g7-em1Mvw H2-D1b-tm1Bpe Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG-MHC I/II DKO), and NOD.Cg-Hc1 Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG-Hc1) mice were originally purchased from Jackson Laboratories and then bred in-house and handled according to WCM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #2014-24).

Primary PTCL samples were implanted subcutaneous (sc, 2 fragments, 1mm3 each) or via intravenous (iv; 1 × 106 cells, 150 μL of DPBS) or intra bone (ib; 1 × 106 cells, 10–20 μL of DPBS) routes, in 4-6-week-old (male/female ratio: 1:1) NSG B2m/NSG-MHC I/II DKO mice.128 PDX-Dlines were s.c. implanted in Matrigel (25%, 1x106 cells, 150 μL of DPBS). Engraftment was monitored every week by visual inspection (s.c.) and/or multicolor flow cytometry on peripheral blood. Mice were sacrificed at the earlier sign of distress. All tissues were collected for histology, immunohistochemistry, and additional ancillary studies. Viable and dry samples were cryopreserved for PDX transplantation/biobanking and genomic/functional studies. Tumors were then propagated along multiple generations corresponding to serial passages (T).

Cell culture

PDX-Dlines, PDX derived stromal cells, PTCL continuous cell lines (SUPM2, L82, MAC1 and TLBR1), and MS-5 stromal cell line were cultured in RPMI (Sigma) supplemented with 20% FBS (Corning), 100 U/ml glutammine (Sigma), Normocin 1:500 (InVivoGen) and 100μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. IL2 and TO-ALCL-BELLI PDX-Dlines were supplemented with exogenous interleukin-2 (50U/ml) and interleukin15 (10μg/ml) (R&D). Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a panel of monoclonal antibodies against human T cell surface markers twice per year.

Method details

Isolation of viable PDX-derived tumor cells