Abstract

Background

There are several treatment options for managing acute asthma exacerbations (sustained worsening of symptoms that do not subside with regular treatment and require a change in management). Guidelines advocate the use of inhaled short acting beta2‐agonists (SABAs) in children experiencing an asthma exacerbation. Anticholinergic agents, such as ipratropium bromide and atropine sulfate, have a slower onset of action and weaker bronchodilating effect, but may specifically relieve cholinergic bronchomotor tone and decrease mucosal edema and secretions. Therefore, the combination of inhaled anticholinergics with SABAs may yield enhanced and prolonged bronchodilation.

Objectives

To determine whether the addition of inhaled anticholinergics to SABAs provides clinical improvement and affects the incidence of adverse effects in children with acute asthma exacerbations.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE (1966 to April 2000), EMBASE (1980 to April 2000), CINAHL (1982 to April 2000) and reference lists of studies of previous versions of this review. We also contacted drug manufacturers and trialists. For the 2012 review update, we undertook an 'all years' search of the Cochrane Airways Group's register on the 18 April 2012.

Selection criteria

Randomized parallel trials comparing the combination of inhaled anticholinergics and SABAs with SABAs alone in children (aged 18 months to 18 years) with an acute asthma exacerbation.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We used the GRADE rating system to assess the quality of evidence for our primary outcome (hospital admission).

Main results

Twenty trials met the review eligibility criteria, generated 24 study comparisons and comprised 2697 randomised children aged one to 18 years, presenting predominantly with moderate or severe exacerbations. Most studies involved both preschool‐aged children and school‐aged children; three studies also included a small proportion of infants less than 18 months of age. Nine trials (45%) were at a low risk of bias. Most trials used a fixed‐dose protocol of three doses of 250 mcg or two doses of 500 mcg of nebulized ipratropium bromide in combination with a SABA over 30 to 90 minutes while three trials used a single dose and two used a flexible‐dose protocol according to the need for SABA.

The addition of an anticholinergic to a SABA significantly reduced the risk of hospital admission (risk ratio (RR) 0.73; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.63 to 0.85; 15 studies, 2497 children, high‐quality evidence). In the group receiving only SABAs, 23 out of 100 children with acute asthma were admitted to hospital compared with 17 (95% CI 15 to 20) out of 100 children treated with SABAs plus anticholinergics. This represents an overall number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 16 (95% CI 12 to 29).

Trends towards a greater effect with increased treatment intensity and with increased asthma severity were observed, but did not reach statistical significance. There was no effect modification due to concomitant use of oral corticosteroids and the effect of age could not be explored. However, exclusion of the one trial that included infants (< 18 months) and contributed data to the main outcome, did not affect the results. Statistically significant group differences favoring anticholinergic use were observed for lung function, clinical score at 120 minutes, oxygen saturation at 60 minutes, and the need for repeat use of bronchodilators prior to discharge from the emergency department. No significant group difference was seen in relapse rates.

Fewer children treated with anticholinergics plus SABA reported nausea and tremor compared with SABA alone; no significant group difference was observed for vomiting.

Authors' conclusions

Children with an asthma exacerbation experience a lower risk of admission to hospital if they are treated with the combination of inhaled SABAs plus anticholinergic versus SABA alone. They also experience a greater improvement in lung function and less risk of nausea and tremor. Within this group, the findings suggested, but did not prove, the possibility of an effect modification, where intensity of anticholinergic treatment and asthma severity, could be associated with greater benefit.

Further research is required to identify the characteristics of children that may benefit from anticholinergic use (e.g. age and asthma severity including mild exacerbation and impending respiratory failure) and the treatment modalities (dose, intensity, and duration) associated with most benefit from anticholinergic use better.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Humans; Infant; Administration, Inhalation; Adrenergic beta‐2 Receptor Agonists; Adrenergic beta‐2 Receptor Agonists/administration & dosage; Adrenergic beta‐2 Receptor Agonists/therapeutic use; Asthma; Asthma/drug therapy; Atropine; Atropine/administration & dosage; Atropine/therapeutic use; Cholinergic Antagonists; Cholinergic Antagonists/administration & dosage; Cholinergic Antagonists/therapeutic use; Disease Progression; Drug Therapy, Combination; Drug Therapy, Combination/methods; Hospitalization; Hospitalization/statistics & numerical data; Ipratropium; Ipratropium/administration & dosage; Ipratropium/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Combined inhaled anticholinergics and beta2‐agonists for initial treatment of acute asthma in children

Background In an asthma attack, the airways (small tubes in the lungs) narrow because of inflammation (swelling), muscle spasms and mucus secretions. Other symptoms include wheezing, coughing and chest tightness. This makes breathing difficult. Reliever inhalers typically contain short‐acting beta2‐agonists (SABAs) that relax the muscles in the airways, opening the airways so that breathing is easier. Anticholinergic drugs work by opening the airways and decreasing mucus secretions. Review question We looked at randomised controlled trials to find out whether giving inhaled anticholinergics plus SABAs (instead of SABAs on their own) in the emergency department provides benefits or harms in children having an asthma attack. Key results We found that children with a moderate or severe asthma attack who were given both drugs in the emergency department were less likely to be admitted to the hospital than those who only had SABAs. In the group receiving only SABAs, on average 23 out of 100 children with acute asthma were admitted to hospital compared with an average of 17 (95% CI 15 to 20) out of 100 children treated with SABAs plus anticholinergics. Taking both drugs was also better at improving lung function. Taking both drugs did not seem to reduce the possibility of another asthma attack. Fewer children treated with anticholinergics reported nausea and tremor, but no significant group difference was observed for vomiting. Quality of the evidence and further research Most of the studies were in preschool‐ and school‐aged children; three studies also included a small proportion of infants under 18 months of age, although there was no evidence that inclusion of these infants with wheezy episodes affected the results. Nine trials (45%) were at a low risk of bias and we regarded the evidence for hospitalisation as high quality. Physicians can administer the dose of anticholinergic and SABA in several different ways; as a single dose, or as a certain number of doses or more flexibly. Most of the trials gave the children two or three doses and we think that more research is needed to improve characterization of children that benefit from, and the most effective number and frequency of doses of, anticholinergic treatment.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Anticholinergic and short‐acting beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols) for initial treatment of acute asthma in children.

| Anticholinergic and shorth‐acting beta2‐agonists (SABA) versus SABA alone (all protocols) for initial treatment of acute asthma in children | ||||||

| Patient or population: children with initial treatment of acute asthma Settings: emergency department Intervention: anticholinergic and SABA versus SABA alone (all protocols) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Anticholinergic and SABA versus SABA alone (all protocols) | |||||

| Primary outcome: hospital admissions hospital admissions | 23 per 100 | 17 per 100 (15 to 20) | RR 0.73 (0.63 to 0.85) | 2497 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | 3 studies had no admissions so did not contribute to the RR. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the mean control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SABA: short‐acting beta‐agonists. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

Asthma is caused by inflammation in the airways and bronchoconstriction, which makes it difficult to breathe and leads to wheezing and breathlessness. The underlying inflammation causes the lining of the airways to secrete mucus, which also obstructs the free flow of air through the lungs. The bronchoconstriction is alleviated by using bronchodilators such as short acting beta2‐agonists (SABAs), while the underlying inflammation can be treated with regular inhaled corticosteroids. However, symptoms may flare up in response to an asthma trigger (e.g. virus, dust, pollen) leading to an asthma exacerbation. It is not known why the inflammation, secretions and bronchoconstriction occur. Asthma exacerbations can be life threatening and may require more medications than are used on a day‐to‐day basis.

Description of the intervention

The initial management of acute paediatric asthma exacerbations in children focuses on the rapid relief of bronchospasm using inhaled or nebulized bronchodilators (BTS 2011; GINA 2011). Children who do have moderate or severe asthma and those who do not respond sufficiently to bronchodilators to relieve symptoms require the addition of oral or intravenous glucocorticoids (BTS 2011; GINA 2011; Lougheed 2012). SABAs are clearly the most effective bronchodilators due to their rapid onset of action and the magnitude of achieved bronchodilation (Sears 1992; Svedmyr 1985; Teoh 2012). Anticholinergic agents, such as ipratropium bromide and atropine sulfate, have a slower onset of action and weaker bronchodilating effect, but may specifically relieve cholinergic bronchomotor tone and decrease mucosal edema and secretions (Chapman 1996; Gross 1988; Silverman 1990). Thus, the combination of inhaled anticholinergics with SABAs may yield enhanced and prolonged bronchodilation.

National and international guidelines recommend the addition of anticholinergics to inhaled SABAs in people with an acute severe asthma exacerbation and suggest consideration of this therapy in people with moderate exacerbations (BTS 2011; GINA 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

The first version of this Cochrane review published in 1997 found a significant reduction in hospital admissions in school‐aged children with severe exacerbations receiving intensive anticholinergic treatment. The review was updated in 2000 with the addition of three new trials further strengthening the initial conclusions (Plotnick 2000). With the identification of seven new studies, the 2012 update aims to examine the conclusions of the earlier version of this review and explore if characteristics of participants or treatment are associated with increased benefit.

Objectives

To determine whether the addition of inhaled anticholinergics to inhaled SABAs provides clinical improvement and affects the incidence of adverse effects in children with acute asthma exacerbations.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in an emergency department setting, comparing the combination of an inhaled anticholinergic drug and SABA versus a SABA alone in the treatment of an acute asthma exacerbation.

Types of participants

Children aged 18 months to 18 years presenting to an emergency department with an acute exacerbation of asthma. Where studies included children younger than 18 months, we excluded them if the younger children contributed more than 5% of the total study population (post‐hoc decision).

Types of interventions

Treatment group: single or repeated doses of nebulized or inhaled short‐acting anticholinergics plus SABAs.

Control group: single or repeated doses of nebulized or inhaled placebo plus SABAs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Hospital admission.

Secondary outcomes

Change from baseline in % predicted forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) (60 and 120 minutes after the last combined anticholinergic and SABA inhalation).

Percent change from baseline in FEV1 (60 and 120 minutes after the last combined inhalation).

Change from baseline in respiratory resistance (60 and 120 minutes after the last combined inhalation).

Change from baseline in clinical score (60 and 120 minutes after the last combined inhalation).

Oxygen saturation (60 and 120 minutes after the last combined inhalation).

Need for repeated bronchodilator treatments after the intervention/placebo protocol, prior to disposition.

Need for systemic corticosteroids.

Adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting and tremor.

Relapse rate.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For the previous version of this review, MEDLINE (1966 to April 2000), EMBASE (1980 to April 2000) and CINAHL (1982 to April 2000) were searched using the following MeSH, full text and keyword terms: [asthma, wheez* or respiratory sounds] and [random*, trial*, placebo*, comparative study, controlled study, double‐blind, single‐blind] and [child* or infan* or adolescen* or pediatr* or paediatr*] and [emergenc* or acute*] and [ipratropium* or anticholinerg* or atropin*].

For the 2012 review update, we undertook an 'all years' search of the Cochrane Airways Group Register of Trials with the following terms: anticholinergic* or anti‐cholinergic* or atropine* or ipratropium or tiotropium or oxitropium or Aclidinium) AND ((beta* and agonist) or bronchodilat* or salbutamol or fenoterol or albuterol or terbutaline or metaproterenol) and (child* or paediat* or pediat* or adolesc* or infan* or toddler* or bab* or young* or preschool* or "pre school*" or pre‐school* or newborn* or "new born*" or new‐born* or neo‐nat* or neonat*.

Searching other resources

We reviewed bibliographies of all trials and review articles identified through searches to identify potentially relevant citations. We contacted the manufacturer of ipratropium bromide, Boehringer Ingelheim, for the original review and the update, to identify other published or unpublished trials. We contacted trialists working in the field of paediatric asthma to identify potentially relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In the updated search, one review author (BG) examined each new citation (title and abstract) identified through one of the above strategies and classified as clearly included, possibly included or clearly not an RCT. We retrieved and assessed full‐text articles of all citations identified as definite or possible RCTs, irrespective of language of publication. BG and Toby Lasserson (former Managing Editor of the Cochrane Airways Group) assessed the full text independently to determine if the study met the inclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreement by consensus. Emma Welsh (Managing Editor of the Cochrane Airways Group) and Elizabeth Stovold (Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Airways Group) assisted in screening repeat literature searches prior to publication.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from eligible studies and entered data into the Characteristics of included studies table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

One review author (BG) and one member of the Cochrane Airways Group (TL or EJW) assessed the risk of bias. Agreement was reached independently in each case. We assessed the risk of bias as high, low or unclear in accordance with recommendation in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for the following domains (Higgins 2011):

random sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding (performance bias and detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective reporting (reporting bias);

other bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We analyzed treatment effects for dichotomous outcomes as pooled risk ratios (RR). For continuous outcomes, we used the mean difference (MD) or the standardized mean difference (SMD) to estimate the pooled effect size. For example, the MD was reported for pulmonary function tests using the same unit of measure. We used the SMD, reported in 'standard deviation units', when the change in the same pulmonary function test was reported in different units (change in % predicted FEV1 and % change in FEV1). We presented pooled effect sizes along with the 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the study investigators or study sponsors to verify study methodology and extracted information and to provide additional data if necessary.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I2 statistic for assessing the level of statistical heterogeneity between the results of the studies. We used the following levels of I2 as a guide:

0% to 40% may not be important;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We visually inspected funnel plot symmetry where we had more than 10 trials contributing data to a meta‐analysis in an effort to detect possible biases.

Data synthesis

We entered data into Review Manager 5.1 software (RevMan 2011). Treatment effects for dichotomous outcomes were analyzed and reported as pooled RRs using the fixed‐effect model (Greenland 1985), or, in case of substantial, unexplained heterogeneity, the random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We postulated a priori that three factors may potentially influence the magnitude or direction, or both, of the therapeutic response, namely:

the intensity of anticholinergic treatment;

co‐intervention with glucocorticoids; and

the severity of exacerbation (based on documented/reported severity by authors and by tertile of admission rate).

Therefore, RCTs were grouped according to the intensity of anticholinergic protocol (single‐dose regimen, multiple fixed‐dose regimen, multiple flexible‐dose regimen) and stratified on the presence/absence of systemic glucocorticoids. Whenever reported, the baseline % predicted FEV1 and hospital admission rate in the control groups were recorded as indicators of severity and examined for their potential interaction with therapeutic effect.

In order to evaluate the effect of baseline severity on the magnitude of response to the intervention, we stratified trials according to severity documented or reported by authors as per the original review. In addition, we ranked each study in increasing order of the control group admission rate as a proxy for severity. We then split these arbitrarily into tertiles, which we referred to as low, medium or high risk. If the admission rate for a particular study was not available, we did not rank that study.

For the 2012 update, we considered adding a subgroup analysis by age of child; however, the overlap in age ranges included in each study precluded this analysis. We considered also doing a subgroup analysis based on cumulative dose of ipratropium delivered. However, this analysis was potentially confounded by the severity of the asthma exacerbation of the children included in the trials as well as differences between the drug delivery methods (nebulizers versus metered‐dose inhalers (MDI) and spacers) and was thus omitted.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to examine the effect on results of excluding unpublished trials, those with poor methodological quality and studies that included a small proportion of children under 18 months of age (less than 5% of total study participants).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For the 2012 update, the search retrieved 223 references for screening (18 April 2012). We excluded studies that had already been assessed for inclusion in the first version of the review and obtained 19 citations for full‐text scrutiny. These citations referred to 19 studies (see Appendix 1 for details of previous search results) and seven new trials met the eligibility criteria for inclusion.

Included studies

Trial protocol/dose regimen

Overall, there were 20 included trials and three trials generated additional comparisons. Two studies provided stratified data subgrouped by severity (Qureshi 1998; Zorc 1999), and one study evaluated two different dosing strategies against control (Schuh 1995). Overall, there were 24 comparisons. We subgrouped trials according to the intensity of the anticholinergic protocol (see Table 2). Six trials on 570 children tested a single dose of ipratropium bromide added to multiple (two to six) doses of SABAs given every 20 to 30 minutes. We termed these the 'single‐dose protocol'.

1. Study treatments.

| Protocol | Study | Age range (years) | Delivery device | Dose of ipratropium bromide | Number of doses | Total dose delivered |

| Single dose | Beck 1985 | 6‐17.5 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 1 | 250 mcg |

| Chakraborti 2006 | 5‐15 | MDI and spacer | 80 mcg | 1 | 80 mcg | |

| Cook 1985 | 12‐18 | Nebulized | 1‐2 mL of 0.025% solution | 1 | 1‐2 mL of 0.025% solution | |

| Ducharme 1998 | 3‐17 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 1 | 250 mcg | |

| Phanichyakam 1990 | 4‐14 | MDI and spacer | 40 mcg | 1 | 40 mcg | |

| Schuh 1995 (single) (single dose) | 5‐17 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 1 | 250 mcg | |

| Multiple fixed‐dose protocol | Benito Fernandez 2000 | 5 months to 16 years | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 2 | 500 mcg |

| BI [pers comm] | 2‐10 | Nebulized | 500 mcg | 3 | 1500 mcg | |

| Iramain 2011 | 2‐18 | Nebulized | 500 mcg children over 20 kg 250 mcg children under 20 kg |

6 | 3000 mcg or 1500 mcg | |

| Peterson 1996 | 5‐12 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 2 | 500 mcg | |

| Qureshi 1997 | 6‐18 | Nebulized | 500 mcg | 2 | 1000 mcg | |

| Qureshi 1998 (moderate) | 2‐18 | Nebulized | 500 mcg | 2 | 1000 mcg | |

| Qureshi 1998 (severe) | 2‐18 | Nebulized | 500 mcg | 2 | 1000 mcg | |

| Reisman 1988 | 5‐15 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 3 | 750 mcg | |

| Schuh 1995 (multiple dose) | 5‐17 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 3 | 750 mcg | |

| Sharma 2004 | 6‐14 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 3 | 750 mcg | |

| Sienra Monge 2000 | 8‐15 | MDI and spacer | 120 mcg | 2 | 240 mcg | |

| Watanasomsiri 2006 | 3‐15 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 3 | 750 mcg | |

| Watson 1988 | 6‐17 | Nebulized | 250 mcg | 2 | 500 mcg | |

| Zorc 1999 (mild) | 1‐17 | Nebulized | 500 mcg | 2 | 1000 mcg | |

| Zorc 1999 (moderate) | 1‐17 | Nebulized | 500 mcg | 2 | 1000 mcg | |

| Zorc 1999 (severe) | 1‐17 | Nebulized | 500 mcg | 2 | 1000 mcg | |

| Multiple flexible‐dose protocol | Calvo 1998 | 5‐14 | MDI and spacer | 20 mcg | Max 7 | 140 mcg (max) |

| Guill 1987 | 13 months to 13 years | Nebulized | 0.05‐0.1 mg/kg | Max 3 | 0.15‐0.3 mg/kg (max) |

Max: maximum; MDI: metered‐dose inhaler.

In 16 intervention arms with 2191 children, doses of ipratropium bromide were administered at multiple fixed time points after the trial began. We termed these trials 'multiple fixed‐dose protocol'. The doses of ipratropium bromide varied from 120 mcg to 500 mcg and the number of doses ranged between two and six over 30 to 90 minutes.

Two studies including 84 children added a dose of anticholinergic to every SABA, leaving the number of inhalations determined by the child's need. These were termed 'multiple flexible‐dose protocol'. Calvo 1998 used a fixed dose of ipratropium bromide (20 mcg) given up to seven times in two hours. Treatment was stopped after the child's clinical score dropped below a predetermined threshold. Guill 1987 used a fixed dose of atropine sulfate (0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg) up to three times at 20‐minute intervals. Treatment was continued until symptoms were controlled or the subject was admitted to hospital.

With one exception that used atropine (Guill 1987), ipratropium bromide was used as the anticholinergic agent.

Participants

Three studies with children younger than 18 months were included (Benito Fernandez 2000; Guill 1987; Phanichyakam 1990). Only Benito Fernandez 2000 reported data for the primary outcome and we tested whether inclusion of this study would unduly affect the analysis (although unlikely, as the mean age of children in the study was 5.7 years).

Outcomes

The most frequently reported outcomes were hospital admission rate and spirometric measurements. Nineteen intervention arms (from 16 studies) reported our primary outcome of hospital admission rate. Of note, 84% of the weight in this outcome was contributed by trials focusing on children with documented or reported moderate or severe airway obstruction and 87% of the weight was contributed by trials in the higher and middle tertile of admission rate. Not all trials considered each outcome. The reporting of adverse and side effects was variable. Adverse effects such as hypertension or tachycardia were reported so infrequently that they could not be considered in this review. Whenever reported, we extracted side effects such as nausea, vomiting and tremor, which may interfere with children's compliance. All reported outcomes are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Defining severity using admission rate

No single baseline spirometric characteristic was consistently reported across all studies. Hence insufficient lung function data were provided to enable us to determine the asthma severity of children at the start of trials. We ascertained asthma severity in two ways.

First, as per the original protocol, we stratified severity using lung function or clinical score at baseline and used both the eligibility/exclusion criteria and the severity reported by authors to confirm our assessment (see Table 3).

2. Severity based on review author assessment of trial report.

| Study | MEAN FEV1/PEFR (inclusion criteria) | MEAN score | Trial report description of severity | Review authors severity classification | Age |

| Beck 1995 | FEV 30‐31% (eligibility: FEV1 < 50% pred) | Not reported | Severe | Severe | 6 years‐upper range not reported |

| Benito‐Fernandez 2000 | Mean PEF: 45% predicted | 4.5 on a 5‐point score | Moderate to severe | Severe | 5 months to 16 years |

| BI (pers comm) | Unclear if measured | severity score of 13 (unknown scale) | Severe | Severe | 2‐10 years |

| Calvo (1998) | PEF = 69‐71% (excluded if PEF > 80% pred.) | 12‐point TAL score: 5.6‐6 (moderate) | Moderate | Moderate | 5‐14 years |

| Chakraborti (2006) | FEV1 69‐71 ± 37% (S+IB) and 57 ± 21% (S alone) | 10‐point clinical asthma score 1.83 (S+IB) vs. 2.07 (S alone) | Mild and moderate | Mild and moderate | 5‐15 years |

| Ducharme (1998) | Children requiring continuous nebulizations of salbutamol were excluded | Mild and moderate | Mild and moderate | 3‐7 years | |

| Iramain (2011) | FEV1 60‐64%/PEF 62‐60% | 15‐point pulmonary score: 12.3 | Moderate and severe | Moderate and severe | 2‐18 years |

| Pederson (1996) | Mean not reported (eligibility FEV1 < 70% pred.) | Not reported | Not reported | Moderate and severe | 5‐12 years |

| Qureshi (1997) | Mean FEV1 and PEF at baseline 37% and 34% (eligibility FEV1 < 50% pred.) | Not reported | Severe | Severe | 6‐18 years |

| Qureshi (1998) (sev) | Subgroup data provided by author: FEV1 34% (eligibility FEV1 < 50% pred.) |

12‐15 on 15‐point asthma score) | Severe | Severe | 2‐18 years |

| Qureshi (1998) (mod) | Subgroup data provided by author: FEV1 55% (eligibility: 50% < FEV1 < 70% pred.) |

8‐11 on a 15‐point Clinical score | Moderate | Moderate | 2‐18 years |

| Reisman (1998) | FEV1 33‐40% (eligibility; FEV1 < 55% pred.) | ‐ | Severe | Severe | 5‐15 years |

| Schuh (1995) | mean FEV1‐34% (eligibility; FEV1 < 50% pred.) | wheezing score 2.2‐2.5 on max of 3 | Severe | Severe | 5‐17 years |

| Sharma (2004) | PEF 35% pred. (excluded PEF < 30% pred. and signs of impending respiratory disease | Wheezing score 2.5 to 2.6 (max = 3) | Moderate | Severe | 6‐14 years |

| Sienra monge (2000) | FEV1: 1 L | not reported | Moderate to severe | Unrated | 8‐15 years |

| Watson (1988) | Mean FEV1 not reported (eligibility FEV1: 30‐70% pred.) | 5.7‐6 on a scale of 0 to 12 | Moderate and severe | Moderate and severe | 6‐17 years |

| Watanasomsiri (2006) | Mean % pred. PEFR at baseline 27‐30% in the subset of people cooperating with the forced expiratory technique)(PEFR was not an inclusion criteria) no exclusion or inclusion based on severity | 6.42 on a scale of 0 to 12 | Proportion of moderate asthma: 73% and of severe asthma: 27% | Moderate and severe | 3‐15 years |

| Zorc (1999) | Subgroups data obtained from authors | Not reported | ‐ | 3 strata (mild, moderate and severe) | 1‐17 years |

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; IB: ipratropium bromide; max: maximum; PEF: peak expiratory flow; PEFR: peak expiratory flow rate; pred.: predicted; S: salbutamol; y.o.: years old.

Eight studies were judged as 'severe' (Benito Fernandez 2000; BI [pers comm]; Qureshi 1997; Qureshi 1998 (severe); Reisman 1988; Schuh 1995 (multiple); Sharma 2004; Zorc 1999 (severe)), four studies as 'moderate and severe' (Iramain 2011; Peterson 1996; Watanasomsiri 2006; Watson 1988), three studies as moderate (Calvo 1998; Qureshi 1998 (moderate); Zorc 1999 (moderate)), two studie as 'mild and moderate ' (Chakraborti 2006; Ducharme 1998), and one study as 'mild' (Zorc 1999 (mild)) asthma.

Sienra Monge 2000 did not provide enough information to confirm the authors' judgment and was left unrated (it did not provide data for the primary outcome).

Next, we used the control group event rate as a proxy for severity. Studies were ranked by the order of the admission rate of the control group, and divided into three groups and labelled as high, medium and low admission rates (see Table 4).

3. Studies grouped by control group event rate as a proxy for severity.

| Protocol | Study |

Admission rate (control group) |

Baseline population spirometry

characteristics (where available) |

Admission rate ‐ ranking |

| Multiple fixed‐dose protocol | Benito Fernandez 2000 | 0.53 | PEFR (%) mean 44.8 | High |

| Qureshi 1998 (severe) | 0.52 | PEFR < 50% predicted | High | |

| Schuh 1995 (multiple) | 0.46 | FEV1 < 50% predicted | High | |

| Qureshi 1997 | 0.45 | PEFR < 50% predicted | High | |

| Iramain 2011 | 0.43 | PEF or FEV1 < 60% predicted | High | |

| Zorc 1999 (severe) | 0.41 | Not reported | Medium | |

| Peterson 1996 | 0.30 | FEV1 < 70% predicted | Medium | |

| Zorc 1999 (moderate) | 0.26 | Not reported | Medium | |

| Reisman 1988 | 0.23 | FEV1 < 55% predicted | Medium | |

| Sharma 2004 | 0.16 | % predicted PEFR 34.4% (mean) | Medium | |

| Qureshi 1998 (moderate) | 0.09 | PEFR < 70% predicted | Low | |

| Watanasomsiri 2006 | 0.09 | % PEFR 29.2 | Low | |

| BI [pers comm] | 0.09 | Not reported | Low | |

| Zorc 1999 (mild) | 0.07 | Not reported | Low | |

| Watson 1988 | 0.00 | Not reported | Low | |

| Single‐dose protocol | Schuh 1995 (single) | 0.46 | FEV1 < 50% predicted | High |

| Ducharme 1998 | 0.17 | Respiratory resistance | Medium | |

| Chakraborti 2006 | 0.00 | FEV1 < 80% | Low |

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; PEF: peak expiratory flow; PEFR: peak expiratory flow rate.

Ranking of severity based on admission rate in the control group corresponded somewhat but not perfectly to ranking based on mean baseline % predicted FEV1 in the studies that reported it or authors' reports. Ranking on admission rate permitted the inclusion of studies that did not use spirometry or did not report mean baseline % predicted FEV1. The ranking admission rate varied from 0 to 0.53.

Studies from the multiple dose‐fixed and single‐dose protocols provided hospital admission data and were, therefore, ranked in this manner.

We define six intervention arms from 'multiple dose‐fixed protocol' trials as a high admission rate (Benito Fernandez 2000; Iramain 2011; Qureshi 1997; Qureshi 1998 (severe); Schuh 1995 (multiple); Schuh 1995 (single)), six as medium admission rate (Ducharme 1998; Peterson 1996; Reisman 1988; Sharma 2004; Zorc 1999 (moderate); Zorc 1999 (severe)), and six as low admission rate (BI [pers comm]; Chakraborti 2006; Qureshi 1998 (moderate); Watanasomsiri 2006; Watson 1988; Zorc 1999 (mild)). We were unable to rank six studies because admission rates were not provided (Beck 1985; Calvo 1998; Cook 1985; Guill 1987; Phanichyakam 1990; Sienra Monge 2000).

Excluded studies

We excluded 30 studies; common reasons for exclusion of studies were: studies on people with chronic or stable asthma (N = 13), hospitalised people (N = 6), inappropriate protocols (e.g. different SABAs in each arm or SABAs at different doses) (N = 4), adults (N = 3), infants (N = 2), non‐randomized control trials (N = 2) and conference abstracts (N = 2). Full details are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

The judgment for each risk of bias domain for each study is included in the Characteristics of included studies table and an overview is given in Figure 1. Methodology of nine of the 19 trials was confirmed by the authors (Calvo 1998; Cook 1985; Ducharme 1998; Guill 1987; Peterson 1996; Qureshi 1997; Qureshi 1998 (severe); Schuh 1995; Zorc 1999 (moderate)).

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgments about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

We considered 10 studies to be at low risk of selection bias: randomisation was performed using computer‐generated random numbers in six studies (Chakraborti 2006; Ducharme 1998; Guill 1987; Iramain 2011; Peterson 1996; Zorc 1999 (mild)), tables of random numbers in three trials (Qureshi 1997; Qureshi 1998; Schuh 1995 (multiple); Schuh 1995 (single)), and one trial used block randomisation (Benito Fernandez 2000). Nine studies did not describe the method of randomisation and were classified as unclear risk of bias, one study used consecutive assignment and was judged to be at high risk of bias (Calvo 1998).

We considered 14 trials to be at low risk of bias for allocation concealment; 12 studies used number‐coded solutions supplied by the pharmacy (Beck 1985; Benito Fernandez 2000; Calvo 1998; Ducharme 1998; Iramain 2011; Peterson 1996; Qureshi 1997; Qureshi 1998 (moderate); Reisman 1988; Schuh 1995 (single); Watanasomsiri 2006; Zorc 1999 (mild)), one study used opaque consecutive numbered envelopes containing assignment (Guill 1987), and one study "used a person not involved in the study" (Chakraborti 2006). Allocation concealment was at unclear risk of bias in the remaining six studies.

Blinding

Sixteen studies claimed double‐blinding while two were described as triple‐blind (Ducharme 1998; Peterson 1996), and two were unblinded (Phanichyakam 1990; Sharma 2004). Twelve studies used an identical placebo in the control group, one study described a similarly looking intervention and placebo solutions (Cook 1985), and three studies did not provide details of the blinding method (BI [pers comm]; Sienra Monge 2000; Watson 1988). It was assumed that the person making the decision to admit to hospital was also blinded to the medication received but only one study described them as blinded (Schuh 1995).

Incomplete outcome data

Thirteen studies reported the presence/absence of participant withdrawal or dropout and the reasons for the attrition if applicable (BI [pers comm]; Calvo 1998; Cook 1985; Ducharme 1998; Guill 1987; Iramain 2011; Peterson 1996; Qureshi 1997; Qureshi 1998 (moderate); Schuh 1995; Watanasomsiri 2006; Watson 1988; Zorc 1999 (severe)). One study referred to 40 children in the abstract but presented data for only 30 children with no clear explanation (Sienra Monge 2000).

Selective reporting

One study recorded data for hospital admission but did not publish the data and commented that the "hospital admission data was not significant" (Beck 1985).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

First we present the primary outcome with all protocols, then we present the prespecified subgroup analyses (trial protocol, severity, co‐intervention of corticosteroid) followed by the secondary outcomes. We did not subgroup the secondary outcomes.

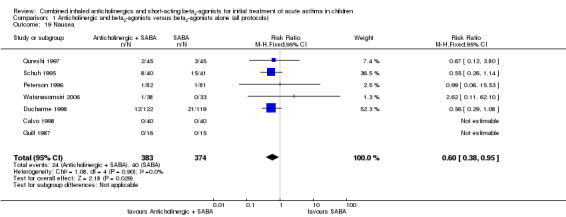

Primary outcome: admission to hospital

When anticholinergics were delivered in addition to SABAs, there was a significant decrease in the risk of hospital admission versus SABAs and placebo (RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.85; Figure 2). The primary analysis was inclusive of all study protocols (single dose, multiple‐fixed and multiple‐flexible); however, only studies using single and multiple‐fixed dose protocols reported data for this outcome. Fifteen studies (nineteen comparisons) reported data for this outcome, but the absence of admission in three studies mean that the pooled RR was based on data from 16 comparisons (2326 children). The result was statistically significant (P value < 0.0001) and there was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity between the study results (I2 = 0%). In the children receiving SABAs only, 23 people out of 100 were admitted to hospital compared with 17 (95% CI 15 to 20) out of 100 for children receiving SABAs plus anticholinergics (Figure 3). This represents an overall number needed to treat for an additional beneficial effect (NNTB) of 16 (95% CI 12 to 29).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Anticholinergic and short‐acting beta2‐agonists versus short‐acting beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), outcome: 1.1 Primary outcome: hospital admissions.

3.

In the children on short‐acting beta2‐agonists only, 23 people out of 100 were admitted to hospital, compared with 17 (95% CI 15 to 20) out of 100 for children on short‐acting beta2‐agonists plus anticholinergics.

A funnel plot of the results for this outcome did not appear to indicate obvious signs of publication bias (Figure 4).

4.

Funnel plot of analysis 1.1.

Primary outcome: admission to hospital: subgroup analysis by study protocol

Subgrouping the studies by study protocol for the same outcome showed no statistically significant difference between subgroups (test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 0.55, degrees of freedom (df) = 1, P value = 0.46, I2 = 0%), although the power was low due to marked group imbalances in weight (Analysis 1.2). Fifteen intervention arms including 1998 children were subgrouped into the multiple fixed‐dose protocol group. Of interest, anticholinergics delivered as a multiple fixed‐dose regimen in 11 studies on 1998 children led to a decrease in the risk of hospital admission by 28% compared with SABA alone (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.84). This result was statistically significant (P value < 0.0001) with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). However, pooling data from only three studies (including 419 children) that used a single‐dose regimen showed no significant reduction in risk (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.56 to 1.26). Studies grouped into the multiple flexible‐dose protocol did not provide data for this outcome. Due to subgroup imbalance in number and severity, we cannot firmly conclude on whether the intensity of therapy makes a difference in the magnitude of effect of treatment.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 2 Primary outcome: hospital admissions subgrouped by trial protocol.

Primary outcome: admission to hospital: subgroup analysis by author's judgment of asthma severity and control group admission rate (multiple dose ‐ fixed protocol)

Efforts had been made in previous versions of this review to stratify studies by asthma severity based on baseline lung function or clinical score and validated by both the eligibility and exclusion criteria and the authors' assessment of severity (Table 3). The studies were classified as severe, moderate and severe, moderate, mild and moderate, and mild. There was no significant difference between the RRs in these severity subgroups (test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 2.58, df = 4, P value = 0.63, I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.3). Admittedly, the number of subgroups may have decreased the power to detect statistically significant subgroup differences.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 3 Primary outcome: hospital admissions subgrouped by review authors' judgment of trial report.

In the eight studies including 1188 children, judged as experiencing a severe asthma exacerbation, a 27% decrease in the risk of admission (RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.87) was observed with anticholinergic treatment.

In the four studies including 371 children, rated as having a moderate or severe asthma exacerbation, a 40% reduction in risk of hospitalisation (RR 0.60; 95% CI 0.41 to 0.89) was documented in favor of anticholinergic treatment. In the three studies with 463 children experiencing a moderate asthma exacerbation, no significant reduction in risk of hospitalisation (RR 0.77; 95% 0.49 to 1.22) was observed although the effect size was of similar magnitude to that in the preceding groups.

Two studies including 358 children experiencing mild and moderate asthma exacerbations showed a non‐significant reduction in hospital admission (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.52 to 1.47).

In 117 children judged as experiencing a mild asthma exacerbation, there was no apparent beneficial effect on hospital admission with a wide confidence interval (RR 1.43; 95% CI 0.42 to 4.79).

In this review update, we subgrouped hospital admissions using our proxy measure for severity derived from the control group event rate for hospitalisation (see Table 4). The studies were grouped into tertiles corresponding to high, medium and low risk of admission (high risk, admission rate ≥ 43%; medium risk, admission rate 10% to 42%; and low risk < 10%). There was no significant difference between the RRs in the severity subgroups (test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 1.68, df = 2, P value = 0.43, I2 = 0%).

Six studies on 669 children were grouped in the upper tertile with the highest control group admission rates: there was a 32% decrease in the risk of admission with the use of anticholinergics (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.82; Analysis 1.4). In the six studies on 780 children in the medium‐risk group, the use of anticholinergics reduced the risk of admission by 25% (RR 0.75; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.99). In the subgroup with the lowest control group event rates that included six studies on 968 children, the use of anticholinergics did not significantly reduce the risk of hospital admission (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.42). Comparing the control group weighted risk against the treatment group's risk, the NNTB in the high‐risk group was 7 (95% CI 5 to 12) versus 17 (95% CI 10 to 415) in the medium‐risk group and 139 (not statistically significant) in the low‐risk group (see Table 5).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 4 Primary outcome: hospital admissions subgrouped by control group event rate (tertiles).

4. Number needed to treat for hospital admissions grouped by severity tertile.

| Risk tertile | Weighted control group risk | Risk ratio (95% CI) | Corresponding treatment group risk (95% CI) | NNTB (95% CI) |

| Low | 8.0% | 0.91 (0.59 to 1.42) | 7% (4 to 11) | 139 (not significant) |

| Medium | 24.1% | 0.75 (0.57 to 0.99) | 18% (14 to 24) | 17 (10 to 415) |

| High | 48.7% | 0.68 (0.56 to 0.82) | 33% (27 to 40) | 7 (5 to 12) |

Comparing the control group weighted risk against the treatment group's risk it can be seen that the NNTB in the high risk group was 7 versus 13 in the medium‐risk group and 131 in the low‐risk group.

CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number need to treat for an additional beneficial effect.

Irrespective of the methods to classify severity, the findings would suggest that, within this group of trials of children with predominantly moderate and severe asthma, those with the most severe airway obstruction and a baseline risk of admission of more than 40% showed the largest numerical benefit from the addition of anticholinergics, with an intermediate effect in those with moderate airway obstruction or a baseline risk of admission between 10% and 40% and no significant effect in the few trials pertaining only to children with mild asthma.

Primary outcome: admission to hospital: subgroup analysis by co‐intervention with corticosteroids

Studies were grouped by co‐intervention with corticosteroids (Analysis 1.5). There was no significant difference between the subgroups (test for subgroup differences: Chi2 = 0.66, df = 3, P value = 0.88, I2 = 0%). In the eight studies that administered corticosteroids to all children, the addition of an anticholinergic showed a reduction in the risk of hospital admission (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.59 to 0.86). In the six studies that did not give corticosteroids to all children, the addition of an anticholinergic showed a significant reduction in risk (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.94). In the three studies that administered corticosteroids at the physician's discretion, the point estimate was similar, but the confidence interval crossed unity (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.54 to 1.10). This subgroup analysis would suggest that the effect of an anticholinergic was present, independently from the administration of systemic corticosteroids.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 5 Primary outcome: hospital admissions subgrouped by co‐intervention of corticosteroid.

Secondary outcomes: lung function

Five studies on 402 children reported data for change in % predicted FEV1 across two study protocols (single‐ and multiple‐dose protocols) (Analysis 1.6). Children treated with an anticholinergic showed a significant improvement from baseline in % predicted FEV1 at 60 minutes compared to those treated with SABA alone (MD 10.08; 95% CI 6.24 to 13.92). Two studies on 117 children reported data for the same outcome at 120 minutes (Analysis 1.7), which also showed a statistically significant improvement in % predicted FEV1 in the treatment group versus the control group (MD 6.87; 95% CI 1.17 to 12.56). Fewer studies provided data for change in absolute FEV1 or in peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) at 60 minutes (Analysis 1.8) or 120 minutes (Analysis 1.9); although in both cases appeared to favor the use of salbutamol plus an anticholinergic over salbutamol alone, it was only statistically significant at 60 minutes (SMD 0.57; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.88).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 6 Change from baseline in % predicted FEV1, 60 minutes after the last of IB.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 7 Change from baseline in % predicted FEV1, 120 minutes after last IB.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 8 % Change in FEV1 or PEFR at 60 minutes after last IB (± 15 minutes).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 9 % Change in FEV1 or PEFR at 120 minutes after last IB (± 30 minutes).

Secondary outcome: respiratory resistance

In a post hoc analysis of one trial examining 294 children with mild to moderate exacerbations, stratified on concurrent use of systemic corticosteroids, no statistically significant group difference in respiratory resistance observed at 60 minutes (Analysis 1.10) and at 120 minutes (Analysis 1.11) suggesting no significant influence of concurrent corticosteroids on the magnitude of effect associated with a single dose of ipratropium bromide (Ducharme 1998).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 10 % Change in respiratory resistance at 60 minutes after IB (± 15 minutes).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 11 % Change in respiratory resistance at 120 minutes after IB (± 30 minutes).

Secondary outcome: change in clinical score

No studies provided data on clinical score at 60 minutes; however, three studies on 934 children provided data for clinical score at 120 minutes. Of these three studies, only two included means with standard deviations. Combining these two results showed that subjects treated with an anticholinergic had a greater improvement in clinical score at 120 minutes (SMD ‐0.23; 95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.04; Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 12 Change in clinical score at 120 minutes (± 30 minutes).

Secondary outcome: oxygen (O2) saturation at 60 minutes post therapy

In two trials reporting data for oxygen saturation there was a significant group difference at 60 minutes (RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.97; 415 children; Analysis 1.14), but not at 120 minutes (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.59; 185 children; Analysis 1.15).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 14 O2 saturation < 95% at 60 minutes (± 15 minutes).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 15 O2 saturation < 95% at 120 minutes (± 30 minutes).

Secondary outcome: need for repeat bronchodilator treatment required after standard protocol prior to disposition

Nine studies on 1074 children reported data for the number of children who required repeat treatments of bronchodilator after the study protocol finished and before discharge. Subjects treated with the anticholinergic protocol were 13% less likely to require a repeat bronchodilator treatment before discharge (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.79 to 0.97; Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 13 Need for repeat bronchodilator treatment after standard protocol prior to disposition.

Secondary outcome: adverse events (tremor, vomiting and nausea)

Adverse events reported included tremor, vomiting and nausea. Analysis of nine studies on 524 children showed that children treated with the addition of an anticholinergic were significantly less likely to experience tremor than those treated with inhaled SABAs alone (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.93; Analysis 1.17). Similarly, analysis of seven studies including 757 children showed that children treated with an anticholinergic were significantly less likely to suffer from nausea (RR 0.60; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.95; Analysis 1.19). Analysis of eight studies on 1230 children observed no statistically significant group difference on vomiting (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.56; Analysis 1.18).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 17 Tremor.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 19 Nausea.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 18 Vomiting.

Secondary outcome: relapse

Ten studies on 1389 children reported the relapse rate of children initially discharged from the emergency department during the follow‐up period. No statistically significant difference between groups was observed (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.68; Analysis 1.20).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols), Outcome 20 Relapse.

Sensitivity analysis

Three sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the impact of unpublished data, the inclusion of studies with very young children and inclusion of trials with lower reported methodological quality.

Excluding the two unpublished studies (BI [pers comm]; Peterson 1996) from the primary outcome (all treatment protocols) did not alter the direction or significance level of the risk of admission (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.61 to 0.84).

Of the three included studies that included children under 18 months of age (Benito Fernandez 2000; Guill 1987; Phanichyakam 1990), only Benito Fernandez 2000 contributed data to the primary outcome. Removing this study from the primary outcome (all treatment protocols) made very little difference to the overall result and no impact on the statistical significance (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.86).

Excluding the five studies (Beck 1985; Calvo 1998; Chakraborti 2006; Phanichyakam 1990; Sharma 2004) with lower reported methodological quality and thus at higher risk of bias also did not alter the direction or significance level of the result (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.64 to 0.86).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Primary outcome: hospital admissions

In children with predominantly moderate and severe asthma exacerbation, the combination of an anticholinergic and SABA significantly reduced the risk of hospital admission, the primary outcome of this review. This result was derived from 15 studies (19 comparisons) and 2497 children. Does this result alone justify the use of an anticholinergic in the treatment of all children with acute asthma? To investigate this further we performed several subgroup analyses and considered the validity of these results and their significance for practice.

Different treatment protocols used in the trials

An anticholinergic was administered as a single dose, multiple doses according to a fixed protocol, or a flexible dosing regimen where the an anticholinergic was systematically added to every SABA treatment until sufficient clinical improvement for discharge. This fundamental difference in treatment protocols prompted the first subgroup analysis by study protocol. The majority of data came from trials using multiple doses of ipratropium added to inhaled SABA with a fixed protocol: these trials used doses between 250 mcg and 500 mcg usually via a nebulizer device, with all but one using two or three doses over 30 to 90 minutes. There was a 28% statistically significant reduction in the risk of hospital admission in favor of anticholinergics. The three trials using a single‐dose protocol showed a smaller effect size that was not statistically significant and there were no admission data in the two trials using a flexible protocol. In absence of significant group difference in this analysis and the absence of head‐to‐head comparison between treatment protocols, there is insufficient information to judge how these different treatment protocols compare with each other. Until further data are available, it seems reasonable to recommend repeated doses of ipratropium bromide in a fixed protocol for one to two hours.

Asthma exacerbation severity

Examining participant characteristics and study author's classification of severity, it was evident that the overwhelming majority of trials were conducted in children with moderate or severe asthma, or both (not unexpected for studies performed in emergency departments). When the trials were broken down into severity subgroups based on the rate of admission to hospital in the control group (given inhaled SABAs alone) or based on lung function and clinical score, there was no significant difference between the severity subgroups.

The strongest evidence for a 32% and 25% statistically significant reduction in the risk of admission to hospital with an additional inhaled anticholinergic was seen from the trials classified with a high and medium admission rate, respectively, and while no evidence of effect was noted in the subgroup with the lowest admission rates, the small sample in this latter subgroup reduced the precision of this observation. Seven children (95% CI 5 to 12) needed to be treated in the high admission rate subgroup to prevent one hospital admission versus 17 (95% CI 10 to 415) in the medium admission rate subgroup and 139 (not statistically significant) in the low admission rate subgroup (see Table 5). Similarly, although there was no overall statistically significant subgroup difference when severity was based on lung function and clinical score, there was evidence of effect in all severity subgroups but those classified in the mild and mild‐moderate severity subgroups. We underline that, irrespective of the severity classification used, as the CIs for these subgroups were overlapping, there was no significant difference in RR or risk difference between the severity subgroups in this group of predominantly moderate and severe children. Until further data are available, it seems prudent to recommend the addition of anticholinergics in children with moderate or severe exacerbations.

Use of systemic corticosteroids

As the use of corticosteroids for the treatment of acute asthma is widely established in practice, we explored the possibility of effect modification by co‐intervention with oral corticosteroids (BTS 2011; GINA 2011; Lougheed 2012; Rowe 2001). There was some variation in the use of corticosteroids between studies; corticosteroids were either not used, were systematically used or their use was left to the discretion of the attending physician. We found no statistically significant group difference between the subgroups that did or did not administer systemic corticosteroids and no apparent difference in the size of the effect of an anticholinergic. This suggests that the effect of anticholinergics is not influenced by co‐intervention with systemic corticosteroids, at least not within two to three hours of corticosteroid administration (mean time to decision to admit in studies contributing data to the primary outcome two to three hours). This may be due to the delayed onset of action of systemic corticosteroids three to four hours after administration (Rowe 2001).

Other subgroups

Further subgroup analyses were considered for the 2012 update, but not performed. Analysis by age of child was not possible because of the significant overlap in children's ages between studies (see Table 2) and reported data were not stratified by age group in individual studies. Total dose of treatment could not be reliably established as the majority of studies used nebulizer devices to deliver the drug. With such a wide age range of subjects it is unclear what proportion of the delivered dose reaches the child's airways (Rubin 2003), which would make any comparison difficult to interpret reliably.

Secondary outcomes

Wide ranges of physiological and spirometric parameters were reported among the studies. However, such was the range of parameters used by different studies that the amount of data that could be pooled were limited.

Statistically significant group differences favoring anticholinergic use were observed for lung function whether reported as 'change in % predicted FEV1' or as '% change in FEV1', clinical score at 120 minutes, oxygen saturation at 60 minutes and the need for repeat use of bronchodilators prior to discharge from the emergency department. No significant group difference was seen for the relapse rate.

Adverse events

The combination of anticholinergics and SABAs was associated with a statistically significant 30% and 39% reduced risk of nausea and tremor, respectively. No significant group difference in vomiting was observed. Clinically important adverse effects, such as tachycardia or hypertension, were reported too infrequently to permit aggregation. Thus, the addition of anticholinergics to SABAs decreased the incidence of commonly observed beta2‐adrenergic effects in children treated with SABAs only.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The age range of subjects in the included studies ranged from four months to 18 years (with eight studies including preschool‐aged children). The diagnosis of asthma in young children represents a considerable challenge to clinicians and wheezy symptoms in children younger than 12 months may represent a different disease process (such as bronchiolitis) to asthma. The inclusion of studies with infants less than 12 months of age was carefully considered for its potential to confound the results. In the studies that included subjects less than 18 months of age (Benito Fernandez 2000; Guill 1987; Phanichyakam 1990), the population age range was examined and in each case less than 5% of the population were under 18 months. With such a degree of homogeneity within the studies, the impact, if any, on the overall review was therefore likely to have been very small. Sensitivity analysis removing the only study (Benito Fernandez 2000) that reported admission data of the three studies that included children less than one year of age, did not alter the direction or magnitude of effect for the primary outcome (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.86).

With over half of the studies in this review being carried out in North America, the validity of study results to other countries should be considered. Large geographical variations in hospital admission rates have been predominantly attributed to differences in asthma diagnosis, use of daily prophylaxis, intensity of emergency therapy, admission criteria and bed availabilities (Homer 1996; Payne 1995). It is acknowledged in the UK and elsewhere, that admission rates in chronic disease may also be influenced by factors such as population deprivation and availability of primary care services (Saxena 2006). These factors may limit the external validity (generalizability) of study results, but as they would be applied similarly to both the treatment and control group within each study, this would not affect the internal validity of the observed effect. Interestingly, the absence of statistical heterogeneity of study results across trials provides reassurance to the robustness of study results across countries from which these studies originated.

Quality of the evidence

Like all systematic reviews, this meta‐analysis is limited by the quality of existing data (Khan 1996). This review examined studies for bias against fixed pre‐established criteria in keeping with current Cochrane review methodology. Potential biases were identified in five out of the 19 studies contributing data to our primary outcome. However, there were a far greater number of studies where the potential for bias was unclear. This could be a reflection of poor methodological reporting or poor methodology. Sensitivity analysis removing studies with potential bias did not change the direction and significance of the results for the primary outcome in any of the treatment protocols (Beck 1985; Calvo 1998; Chakraborti 2006; Phanichyakam 1990; Sharma 2004). Data from two unpublished studies (BI [pers comm]; Peterson 1996) were included in this review and sensitivity analysis showed that removing them from the analysis did not impact significantly on the overall result for the primary outcome.

Although only one study clearly described the physician making the decision to admit as blinded to the study medication, the double‐blinded nature of nearly all trials (18 out of 20 were double blinded) would imply that study physicians making such clinical decisions were also blinded to the study medication. This should be clearly reported in future trials.

Despite these possible limitations, we did not consider them to have affected the strength or direction of the results for our primary outcome and so we rated the quality of evidence for the effect on hospital admission as high. However, unanswered questions remain regarding the optimal dose, intensity of therapy and severity of asthma exacerbations in relation to the reduced risk of hospital admission.

Potential biases in the review process

We attempted to minimize selection bias in the review process by using a broad search strategy and having the extracted data checked by a member of the editorial base of the Cochrane Airways Group.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The present review summarizes the best evidence available to April 2012. The first update identified three new trials not included in the first version of this review published in 1997. This update has added seven new trials. The conclusion regarding the single‐dose protocol and the multiple dose‐fixed protocol with regard the primary outcome remains unchanged due to the absence of new trials. With four additional trials in the multiple dose‐fixed protocol, the findings of the previous review were confirmed and strengthened. Thus supporting the addition of multiple doses of anticholinergics to SABAs for reducing hospital admission and improving lung function in children not only with severe but also with moderate asthma exacerbations.

The findings of this review are similar to other reviews examining a paediatric population (Rodrigo 2005). In their review, Rodrigo et al included 16 studies examining the use of anticholinergics plus SABAs versus SABAs alone in childhood asthma. Of those studies, 15 were examined in this review. Timsit 2002 was excluded from this review as the protocol examined a different dose of SABA in each treatment arm. The review concluded that "the addition of multiple doses of inhaled ipratropium bromide to SABAs is indicated in the standard treatment in children, adolescents and adults with moderate to severe exacerbations of asthma in the emergency setting" (Rodrigo 2005). In line with our definition, Rodrigo 2005 defined severity by baseline spirometric testing (FEV1 or peak expiratory flow (PEF) 50% to 70% of predicted as moderate exacerbation and FEV1 or PEF less than 50% of predicted as a severe exacerbation or different clinical scores).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The findings of this Cochrane review support the use of anticholinergics in addition to SABAs over SABAs alone in the management of acute asthma in children, with an anticipated 27% reduction in the risk of hospital admission. The absence of statistically significant subgroup difference in treatment response between severity subgroups or those receiving different treatment intensity (multiple fixed‐dose versus single‐dose) prevents firm conclusions regarding a possible effect modification associated with treatment intensity and asthma severity. Yet, given the large weight of the trials pertaining to children with moderate or severe asthma (with an under‐representation of those with mild asthma) and the absence of effect in the mildest subgroup, it seems prudent to recommend the systematic use of anticholinergics in children with moderate or severe asthma only. Similarly, as most of the evidence is derived from trials testing a multiple fixed‐dose protocol using three doses of 250 mcg or two doses of 500 mcg of ipratropium bromide administered by nebulizer over 60 to 90 minutes, in combination with a SABA, we would recommend this treatment strategy and duration. There are also insufficient data to comment on the efficacy of adding anticholinergic to every SABA treatment, that is, titrating the number of both therapies to the child's response, on the optimal duration of combination therapy, and no evidence to explore whether the anticholinergic dose should be adjusted to the child's age. The addition of anticholinergics to SABAs was associated with significantly less tremor and nausea than SABAs alone.

Implications for research.

Future trials should be designed to address five issues, the impact on the magnitude of effect of: (1) the severity of airway obstruction (mild asthma and impending respiratory failure); (2) child's age (preschooler‐aged versus school‐aged children); (3) intensity/flexibility of therapy (fixed versus flexible); (4) dose of anticholinergics (250 mcg versus 500 mcg) and (5) delivery devices (nebulization versus inhalation). This could be done by conducting head‐to head comparisons with different doses, treatment intensity (multiple fixed‐dose versus multiple flexible‐dose protocols) and different inhalation modalities (metered dose inhaler versus nebulization) or by stratifying on child's age and baseline severity or both. Indeed, future research must attempt to define the severity of asthma exacerbation reliably and reproducibly in the study population by standardized methods (e.g. spirometry, respiratory resistance or interrupter technique) or validated clinical scores, or both. Any such attempts should consider the difficulties of using spirometric parameters in a young population (Arets 2001), although it offers the most objective means to ascertain the severity of airway obstruction reliably (Silverman 2007). Alternate measures include use of clinical scores with validated cut‐offs for severity such as the Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure (Chalut 2000; Ducharme 2008).

Because systemic glucocorticoids are now the standard treatment of children with moderate and severe exacerbations, they should be systematically given with SABAs in future trials. Trials are needed to examine the effect of adding anticholinergics in a multiple flexible‐dose manner, that is, each time a SABA is deemed necessary.

Future trials should include more sensitive and reliable endpoints such as number of bronchodilator inhalations and oxygenation (during the emergency department treatment), duration of hospitalisation and duration of need for intensive (at less than four‐hour interval) bronchodilator inhalation (for hospitalised children) and attempt to measure time to full recovery in discharged participants, that is, the duration of symptoms, rescue SABA use, functional status and quality of life.

In addition, it seems urgent to assess the efficacy and duration of anticholinergics in children with impending respiratory failure at risk of admission or admitted to the intensive care unit.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 September 2013 | Amended | Typo in BG affiliation amended |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1996 Review first published: Issue 2, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 April 2012 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Seven new studies added (Benito Fernandez 2000; Chakraborti 2006; Iramain 2011; Sharma 2004; Sienra Monge 2000; Watanasomsiri 2006) making a total of 20 studies including 2697 children; methods for assessing risk of bias updated; summary of findings table added; conclusions changed. |

| 18 April 2012 | New search has been performed | Literature search re‐run |

| 22 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 25 April 2000 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Three new trials were included in this update; two pertaining to the multiple dose ‐ fixed protocol (Qhreshi, 1998; Zorc, 1999) and one pertaining to the multiple dose ‐ flexible protocol (Calvo, 1998); one previously unpublished trial (Ducharme, 1995) was published and is hereafter referred to as Ducharme, 1998. The addition of these new trials confirmed previous findings about the efficacy of intensive anticholinergics and beta2‐agonist inhalations in acute severe pediatric asthma. It raised the possibility that intensive therapy may have some benefits for children with moderate exacerbations by reducing the number of inhalations required after the fixed protocol. Despite a new trial testing the multiple‐dose flexible protocol, the evidence is still insufficient to conclude about the benefits of the systematic addition of anticholinergics to every beta2‐agonist inhalation, irrespective of disease severity. No new trial was added to the single dose protocol, which remains unchanged. |

Acknowledgements

No source of funding was available for this review. We thank Laurie Plotnick for his contribution to the previous version of this review. We thank the Cochrane Airways Review Group, namely Stephen Milan, Anna Bara, Elizabeth Stovold, Toby Lasserson, Christopher Cates and Emma Welsh for the literature search and ongoing support and Dr Paul Jones for his constructive comments. We also thank Dr Terry Klassen and Dr David McGillivray for their invaluable suggestions and Dr Francisco Noya and L Nannini for translating our correspondence to and from Spanish‐speaking study authors. We are indebted to the trials' authors, namely Drs M.F. Guill, F.A. Qureshi, S. Schuh, K.P. Dawson, T. Klassen, J.J. Zorc and G.M. Calvo, who cooperated enthusiastically to our requests for information.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Archive of search results for review

Issue 3, 2000

Forty studies were reviewed in full text for possible inclusion; 37 studies were identified by the literature search and bibliographies and three studies were identified by contact with trialists. A total of 13 randomised controlled trials were selected for inclusion.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Anticholinergic and beta2‐agonists versus beta2‐agonists alone (all protocols).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Primary outcome: hospital admissions | 19 | 2497 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.63, 0.85] |

| 2 Primary outcome: hospital admissions subgrouped by trial protocol | 19 | 2497 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.63, 0.85] |

| 2.1 Single‐dose protocol | 3 | 419 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.56, 1.26] |

| 2.2 Multiple fixed‐dose protocol | 15 | 1998 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.61, 0.84] |

| 2.3 Multiple flexible‐dose protocol | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Primary outcome: hospital admissions subgrouped by review authors' judgment of trial report | 18 | 2497 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.63, 0.85] |

| 3.1 Severe | 8 | 1188 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.61, 0.87] |

| 3.2 Moderate‐severe | 4 | 371 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.41, 0.89] |

| 3.3 Moderate | 3 | 463 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.49, 1.22] |

| 3.4 Mild‐moderate | 2 | 358 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.52, 1.47] |

| 3.5 Mild | 1 | 117 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.42, 4.79] |

| 4 Primary outcome: hospital admissions subgrouped by control group event rate (tertiles) | 18 | 2417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.63, 0.85] |

| 4.1 High control group event rate (upper tertile) | 6 | 669 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.56, 0.82] |

| 4.2 Medium control group event rate (middle tertile) | 6 | 780 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.57, 0.99] |

| 4.3 Low control group event rate (lower tertile) | 6 | 968 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.59, 1.42] |

| 5 Primary outcome: hospital admissions subgrouped by co‐intervention of corticosteroid | 17 | 2407 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.63, 0.84] |

| 5.1 Background corticosteroids | 8 | 1043 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.59, 0.86] |

| 5.2 No background corticosteroids | 6 | 353 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.47, 0.94] |

| 5.3 Variable (at physicians discretion) | 3 | 511 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.54, 1.10] |

| 5.4 Not reported | 1 | 500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.48, 1.53] |

| 6 Change from baseline in % predicted FEV1, 60 minutes after the last of IB | 5 | 402 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.08 [6.24, 13.92] |

| 7 Change from baseline in % predicted FEV1, 120 minutes after last IB | 2 | 117 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.87 [1.17, 12.56] |

| 8 % Change in FEV1 or PEFR at 60 minutes after last IB (± 15 minutes) | 4 | 166 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.25, 0.88] |

| 9 % Change in FEV1 or PEFR at 120 minutes after last IB (± 30 minutes) | 4 | 219 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [‐0.15, 0.39] |

| 10 % Change in respiratory resistance at 60 minutes after IB (± 15 minutes) | 1 | 294 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.02, 0.07] |

| 10.1 Co‐intervention: corticosteroids during the previous 60 minutes | 1 | 70 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.13, 0.09] |

| 10.2 Co‐intervention: no corticosteroids | 1 | 224 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [‐0.02, 0.08] |