Abstract

There is a growing interest in the development of reliable analytical methods for characterizing tire and road wear particles (TRWP). The current research extends the use of single particle analysis techniques to various experimental biota samples. TRWP and cryogenically milled tire tread (CMTT) were identified using a weight of evidence framework including density separation, optical microscopy, and chemical mapping (scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy). Our techniques successfully identified CMTT particles in laboratory earthworms exposed to soil spiked with CMTT. A river biota sample (bivalves) collected from the Seine with no detectable TRWP was spiked with road dust containing TRWP. Particle identification was performed after a biota digestion protocol and density separation of particles > 1.5 g/cm3 and < 2.2 g/cm3 which resulted in sufficient TRWP for identification and characterization. The average TRWP particle size from the road dust spiked biota sample was 126 μm by number and 220 μm by volume (range: 9 –572 μm). The size distribution overlay of TRWP identified from spiked biota were consistent with TRWP identified from the original road dust sample suggesting that the current method for biota digestion, dual density separation, and TRWP characterization is feasible for similar samples.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-98902-3.

Keywords: TRWP, Microplastic, Single particle analysis, Chemical mapping, Biota digestion

Subject terms: Environmental impact, Environmental monitoring

Introduction

There is a growing interest in the development of reliable analytical methods for characterizing environmental microplastic particles (MP), which are generally thermoplastic materials 1 μm to 5 mm in size1. Tire and road wear particles (TRWP), despite not conforming to the conventional definition of plastic materials, have been prioritized for inclusion in MP environmental assessments2–5. TRWP consist of tread rubber elastomers with varying amounts of mineral encrustations from the pavement and other environmental sources6,7. Transport of TRWP in the air or via runoff to terrestrial and aquatic environments is possible8–10.

The composition of tire tread includes styrene-butadiene rubber, butadiene rubber, natural rubber, sulfur- and zinc-containing vulcanization agents, and filler materials that include carbon black, silica, and chalk7,11,12. Analytical methods for identification and characterization of individual TRWP in complex environmental matrices are needed. Previous research has examined the physical and chemical properties of tread materials and TRWP via numerous experimental techniques including mass- and microscopy-based analysis4,6,7,9,12–32. For example, recent studies have quantified the mass of TRWP in air, soil, freshwater, and sediment using pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Py-GC-MS), however information on TRWP size distribution is not possible using this mass analysis alone9,16,27–29. Further research has characterized TRWP with various techniques including size fractionation/mass techniques and tactile/optical identification26,33–36. While there are strengths and limitations with each method, the use of these techniques aid in the advancement of characterizing TRWP in various environmental matrices.

Previous studies have provided some limited information regarding TRWP identification and size distribution in biota samples. For example, Hart, et al.37 examined microplastic particles in dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and four species of prey fish including hardhead catfish (Ariopsis felis), pigfish (Orthopristis chrysoptera), pinfish (Lagodon rhomboides), and Gulf toadfish (Opsanus beta) collected from Sarasota Bay (Florida). The authors indicated that none of the gastric samples from dolphins contained particles suspected to be tire particles as measured by physical attributes and optical properties including examination for particles (> 35 μm) that were black in color, cylindrical shape, had a rubbery surface texture, and maintained their shape when manipulated with forceps37. The authors identified particles suspected to be tire tread particles (using the same physical attributes and optical properties noted above) in 23.1 and 32% of prey fish muscle and gastrointestinal tract tissue, respectively37. However, no additional size distribution data was provided for the suspected tire tread particles.

Parker et al.38 examined microplastic particles in five fish species from the Charleston Harbor estuary along the southeastern Atlantic Ocean coast of the United States including Atlantic Menhaden, Spotted Seatrout, Spot, Striped Mullet, and Bay Anchovy. While microplastics were observed in 99% of collected fish, suspected tire wear particles were found in only 14% of individual fish across all five species38. The suspected tire particles were classified based on optical properties (dark in color/black) and physical characteristics (elongated or cylindrical in shape, partially or entirely covered with road dust, rough surface texture and rubbery flexibility when manipulated with forceps). The authors noted that one of the suspected tire particles was examined by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) as the remaining five particles were too small to utilize FTIR38. The suspected tire particle reportedly had a FTIR spectra indicative of carbon black (a common component in tires); however, it is unclear whether the spectra resembled any polymer features of tread or whether the particle was mostly carbon black which is not specific to tire tread origin38. Nonetheless, this particle was classified as a suspected tire particle highlighting some of the uncertainty with the optical and physical property analysis. In total, the suspected tire wear particles accounted for 1.2% of total microplastics identified in the fish tissue38. The authors noted that dimensions were measured for a subset of the microplastic particles (n = 247); however, specific dimensions for different types of microplastics including suspected tire particles were not reported. The authors indicated that the targeted size of microplastics ranged from 63 μm to 5 mm based on isolation methods; however, the measured range of microplastic size was from 43 μm to 11.3 mm in maximum dimension38.

We recently developed and utilized single particle analysis methods including a preparatory density separation technique followed by optical imaging, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and additional chemical mapping techniques to identify and characterize individual TRWP23. The single particle analysis methodology was then extended to TRWP identification and particle size distribution determination in more complex environmental samples including road dust, tunnel dust, settling pond sediment, and river sediment24,25. The present study extends the single particle analysis methods to biota samples including laboratory earthworms as a well-known experimental model and an environmental bivalve sample, highlighting the potential for broader environmental applications. Advancement in the study of microplastic detection methods will aid in understanding the role of biota uptake and potential bioaccumulation across different species of the trophic network. These results are expected to help advance the methods for identification and characterizing TRWP and potentially other microplastics in various environmental matrices including biota samples.

Materials and methods

Particle preparation and collection

Cryogenically milled tire tread (CMTT) particles were generated as described previously23. Briefly, CMTT was prepared using three tire types representative of key passenger car tire characteristics including tread with silica and carbon black as primary fillers. A 2:1:1 ratio representing two parts of the carbon black tire tread for each single part of the silica summer tire tread and the silica winter tire tread were utilized to generate CMTT.

The road dust sample was obtained from a vacuum assisted street sweeping car in Leipzig, Germany as described previously25,26. Briefly, collection of road dust was performed during water spraying and sweeping on the road surface. Before further analyses the sample was freeze dried and dry sieved to < 500 μm using a vibratory sieve shaker (AS200, Retsch, Haan, Germany).

Earthworm sample

CMTT were mixed with milliQ water (100 g/L) for 24 h on a rotary shaker at 20 °C in darkness and were recovered by filtration on a 0.45 μm cellulose filter (Whatman®). CMTT were dried at 40 °C for 24 h and mixed with natural soil (LUFA 2.2®, Speyer, Germany). The sandy loam LUFA 2.2 soil (< 2 mm) is a common standard and reference soil collected in Germany and characterized with sand content of 81.3 ± 2.3%, 12.1 ± 1.3% silt, 6.60 ± 1.3% clay, pH of 5.5 ± 0.1, organic carbon content of 1.93 ± 0.2%, density of 1.13 ± 0.045 g/ml, cation exchange capacity of 10.0 ± 0.8 (100 cmol+/kg), and maximum water holding capacity of 45.2 ± 5.0 (g/100 g)39,40. During the course of the experiment, pH remained within the OECD guideline 222 recommended ranges (4.8–5.3)40,41. The CMTT/soil mixture (5% w/w CMTT) was utilized as a higher experimental particle/mass content and may represent higher environmental concentrations observed near the roadside4,40. The mixture was homogenized on a rotary shaker at 20 °C in darkness for 24 h and adjusted to 60% of the water holding capacity for optimal moister conditions and let to equilibrate for 7 days40,41. For this proof-of-concept analysis, a single experiment was performed using ten pre-acclimated (24 h) adult worm species Eisenia andrei (Annelida: Oligochaeta) from laboratory cultures at Ecotox Centre (Lausanne, CH). The adult worms were introduced into glass crystallizers containing 500 g soil with 5% CMTT in an incubation room (temperature = 20 °C, photoperiod: 16 h light/8 h darkness). Humidity was adjusted during the experiment following the OECD 222 test guideline41. Earthworms were removed after 4 weeks, dried and weighed. The worms were not gut depurated before freeze-drying. They were freeze-dried for 24 h, ground into fine powder with a mortar and pestle and stored at − 20 °C. Enders et al. (2016) previously tested several biota digestion protocols for effective tissue digestion along with documentation of impacts on physical and chemical characteristics of different microplastic particles including black tire rubber elastomers42. While acidic treatment resulted in complete dissolution or disintegration of several polymers including black tire rubber elastomer with increased destruction after higher temperature testing (80 °C), the authors observed that 30% KOH: NaClO mixture resulted in efficient tissue digestion while retaining the physical properties of all tested microplastic particles. Therefore, for single particle analysis, 100 mg of the earthworm sample was digested using 30% KOH: NaClO mixture with ultrasonication for 15 min and shaking for 30 min. The suspension was then washed with deionized water 15 times by centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 15 min. Approximately 90.2 mg of material was available after the digestion and washing steps. The particles were then dried at 60 ℃ for one hour prior to microscopy analysis.

River bivalve sample collection

The river sampling was carried out along the Seine River in France as described in detail previously24. Bivalves (blue mussel; Mytilus edulis) were collected near the mouth of the Seine (Latitude 49.453650, Longitude 0.143674). This collection site reflects estuarine conditions with mixing of the freshwater river and the marine environment of the Channel. After drying the bivalves for at least 16 h at 75 °C, the soft tissue was extracted and placed in a jar for shipment. Prior to microscopy analysis, the bivalves underwent a digestion process which included sonication for 15 min with 30% KOH: NaClO followed by sample shaking for two hours42.

Bivalve sample spiking

Additional experiments were performed using biota spiked with 10% road dust material. Road dust containing ∼ 1.4% w/w TRWPs was spiked into the biota at a 10-fold dilutions corresponding to TRWP concentrations of approximately 0.14% in the final spiked biota sample. This dilution factor is the same dilution performed with artificial sediment as previously reported25. Therefore, size distribution analysis from the spiked biota sample can be compared with previous results obtained from the undiluted road dust sample as well as the spiked sediment sample (consisting of 75% quartz sand, 20% kaolin and 5% peat moss)25. This sample also underwent a digestion process which included sonication for 15 min with 30% KOH: NaClO followed by sample shaking for two hours prior to density separation and microscopy analysis.

TRWP density separation

TRWP sample preparation for single particle analysis has been detailed previously23,25. Particles were density separated using a sodium polytungstate solution22,23,25. Previous research has demonstrated that an appreciable amount of TRWP will have a density between 1.5 g/cm3 and 2.2 g/cm3.22 Therefore, our protocol utilized a dual density separation approach which isolated particles with a density between 1.5 g/cm3 and 2.2 g/cm3. During each density separation step, the suspension was centrifuged at 7800 revolutions per minute (RPM) for 50 min. The tube was left undisturbed in a vertical position for 12 h and then the float and sink portions were extracted using glass pipette. After density separation, particles were then rinsed with deionized water, followed by isopropanol using a 0.45 μm vacuum filtration system (25 mm Hydrophilic Pure Silver membrane filter with a 0.45 μm pore size–Millipore Sigma). The particles were then dried at 60 ℃ for one hour prior to analysis.

Single particle analysis techniques

For sample preparation, a carbon tape (15 mm × 10 mm) was first cut and pressed lightly against the cleaned particle sample. Optical microscopy (OM) inspection was performed using the Keyence VHX-7000 series. Images of the particles transferred onto the carbon tape were captured using a full-ring setting at magnifications of 200x and 400x. A depth-up mode was employed for each image to ensure that particles with uneven surfaces or structures were sharply imaged on the same plane. The same particles on the carbon tape were subsequently used for both optical imaging and SEM/EDX analysis using visual inspection. Hitachi S-3700 N equipped with an IXRF Model 550i EDX analysis system was used for SEM/EDX analysis. This analysis was conducted via a backscattered electron detector at an acceleration potential of 15 kV and vacuum pressure of 40 Pa. Elements were individually resolved, with the exception of Zn and Na, which are labeled as “Na/Zn” in this study because the Zn Lα peak and the Na Kα peak near 1.0 keV cannot be distinguished from one another with the EDX system43.

Previous work has characterized the physical and chemical properties of CMTT and TRWP that include black/opaque optical properties, round/elongated/jagged morphological characteristics, and chemical composition of sulfur (S), sodium/zinc (Na/Zn) with variable amounts of silica (Si), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), and aluminum (Al)23–25. The single particle analysis techniques use a weight of evidence approach that combines physical and chemical properties to identify and distinguish tire/tread particles from other environmental particles and is consistent with previous research6,7,23–25,35.

ImageJ analysis software (U.S. NIH) was used to determine the maximum diameter of each TRWP particle using SEM backscatter images. Diameters (or length) of primary particles were measured using the longest chord joining points on the observable perimeter of the particle; maximum orthogonal dimension (or width) was also measured. Aspect ratio was determined using the ratio of the length to width measurements.

Results and discussion

Identification of CMTT and TRWP

The single particle analysis was divided into two phases including (1) identification and (2) quantitative primary particle analysis. The identification phase consisted of applying single particle analysis techniques including optical microscopy and SEM/EDX mapping. CMTT particles were identified by optical properties (black/opaque), morphological characteristics (jagged shape), and chemical properties (S + Na/Zn) ± (Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al) (Fig. 1).

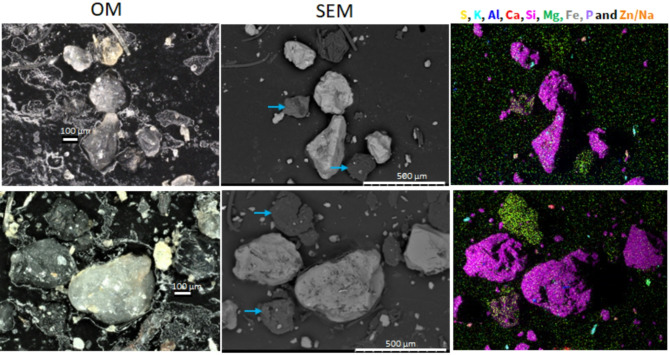

Fig. 1.

SEM/EDX mapping of cryogenically milled tire tread (CMTT) particles. CMTT particles were analyzed by optical microscopy (OM) (left panel insert), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (left panel), and elemental mapping by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (right panel). CMTT particles contained S + Na/Zn with variable amounts of other elements including Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al.

TRWP were identified by optical properties (black/grey/opaque), morphological characteristics (mostly round or elongated in shape with variable mineral encrustations), and chemical properties (S + Zn/Na) ± (Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

SEM/EDX mapping of tire and road wear particles (TRWP). Example TRWP were analyzed by optical microscopy (OM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and elemental mapping by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). TRWP contained S + Zn/Na with other elements including Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al.

After TRWP identification, physical characteristics including size distribution and aspect ratio were determined using optical and chemical mapping characteristics by OM and SEM/EDX analysis as detailed in Materials and Methods and further below.

Identification of CMTT in earthworm sample

An initial single particle analysis feasibility experiment was performed with earthworms exposed to CMTT spiked soil followed by a biota digestion protocol. Stock CMTT particles were analyzed by SEM with elemental mapping and contained S + Na/Zn with other elements including K, Mg, Ca, and Al (Fig. 1). Earthworms exposed to soil spiked with 5% CMTT were further processed for single particle analysis after protein digestion steps outlined in Materials and Methods. CMTT particles were identified by optical properties (black/opaque), morphological characteristics (jagged shape), and chemical properties (S + Na/Zn) ± (Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

OM and SEM/EDX mapping of particles in laboratory earthworm sample. Following biota digestion, particles were examined by optical microscopy (OM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and elemental mapping. Example CMTT with associated elements (S + Na/Zn +/- Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al) are indicated with a blue arrow.

This proof-of-concept experiment demonstrates the ability to characterize experimental earthworm exposure to different particle types in soil including CMTT. This research can aid in understanding the fate, transport, and ecological impact of different particle types in soil. Thus, based on the favorable outcome of the laboratory exposed earthworms, our single particle analysis and biota digestion protocols were carried forward in subsequent quantitative particle size experiments using an environmental matrix as it is possible that specific biota may exhibit important differences in response to chemical digestion. Therefore, particle processing techniques should be verified prior to quantitative particle size analysis.

Identification and characterization of TRWP in bivalve sample

Bivalves collected near the mouth of the Seine river in France as detailed previously24, demonstrated no detectable TRWP with over 600 particles analyzed after biota digestion steps (Supplemental Fig. 1). Therefore, the feasibility of using our single particle analysis techniques was tested by spiking the undigested biota sample with road dust collected previously25,26. Road dust containing ∼ 1.4% w/w TRWPs was spiked into the biota sample at a 10-fold dilution corresponding to TRWP concentrations of approximately 0.14%.

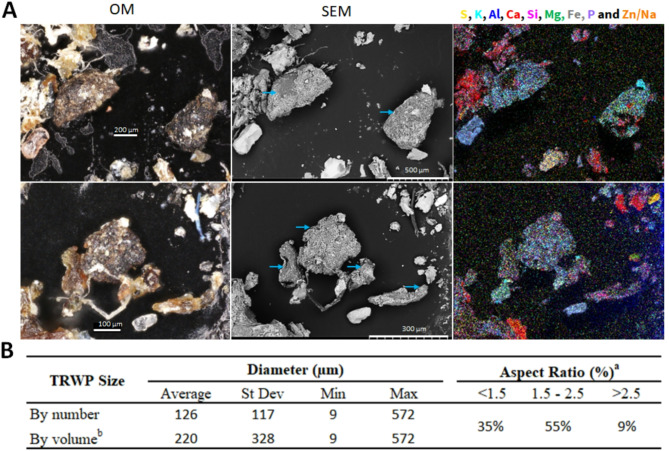

Therefore, after protein digestion of the spiked biota sample, a dual density separation method was employed (Supplemental Fig. 2). The first separation utilized sodium polytungstate solution with a density of 1.5 g/cm3 to separate biological materials with densities close to water from more dense environmental particles. The sink fraction was collected to separate the denser particulate fraction from the biological material (float fraction). The collected particles with density > 1.5 g/cm3 were then separated a second time using 2.2 g/cm3 with TRWP enrichment expected in the float fraction similar to previous experiments. After density separation, particles were examined by optical microscopy (OM), SEM, and elemental mapping (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

OM and SEM/EDX mapping of particles in density separated road dust spiked biota sample. (A) Particles were density separated and examined by optical microscopy (OM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and elemental mapping. Example TRWP are indicated with a blue arrow. (B) A total of 65 TRWP particles (out of 568 total particles) were identified in 20 fields of view and characterized for size distribution and aspect ratio. a Percentages were rounded to two significant figures and therefore do not add up to 100%. b Volume estimated using spherical equivalent corresponding to the diameter of the major particle axis.

TRWP were black/grey/opaque, round to elongated in shape, and contained variable mineral encrustations with chemical properties including S + Zn/Na and variable amounts of Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al. The average TRWP particle size recovered from the biota spiked with road dust was 126 μm by number and 220 μm by volume with a range of 9 μm to 572 μm (Fig. 4). In the present study, biota soft tissue was spiked with road dust to a final concentration of 0.14% (dry w/w). Across 20 fields, a total of 65 TRWP and 503 non-TRWP particles were examined and classified. Thus, if 20 fields are counted, one particle could potentially be detected if TRWP concentration were as low as approximately 0.002% (dry w/w). In practice, the detection limit is likely several-fold higher and the specific number of fields needed to detect a single TRWP or enough TRWP to perform a size distribution analysis would vary due to random variations as well as differences in particle size distributions. This proof-of-concept experiment demonstrates the ability to characterize different particle types in an experimental river biota sample can aid in understanding the fate, transport, and ecological impact including exposure to different organisms.

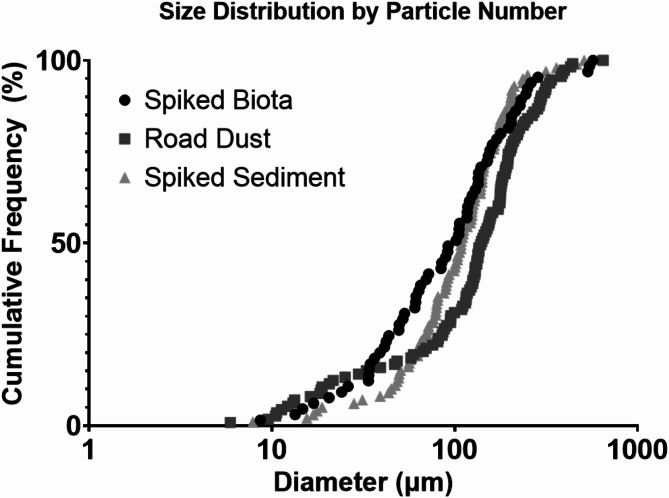

Size distribution analysis from the spiked biota sample was compared with previous results obtained from the undiluted road dust sample as well as a spiked artificial sediment sample25. Cumulative frequency (unit normalized distribution) was displayed for TRWP identified from road dust spiked biota, road dust only, and road dust spiked artificial sediment (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Size distribution overlay of TRWP identified from spiked biota, road dust, and spiked sediment. Cumulative frequency (unit normalized distribution) was displayed for TRWP identified from road dust spiked biota (n = 65), road dust only (n = 113), and road dust spiked artificial sediment (n = 99) as reported previously25.

The size distribution overlay of TRWP identified from spiked biota were consistent with TRWP identified from road dust and spiked sediment as previously characterized25. For example, the mean diameter of the TRWP by number in the spiked biota sample (126 μm) was within 26% of the mean value of the original road dust sample (158 μm) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of average TRWP diameter by number or volume for various sample/matrix types using single particle analysis techniques in this manuscript or previously described24,25.

| Sample/matrix | Average diameter by number (µm) | Average diameter by volume (µm) |

|---|---|---|

| TRWP in tunnel dust | 54 | 94 |

| TRWP in road dust | 158 | 224 |

| TRWP in road dust-spiked biota | 126 | 220 |

| TRWP in road dust-spiked sediment | 124 | 177 |

| TRWP in river sediment | 133 | 171 |

| TRWP in settling pond sediment | 267 | 506 |

Further, the mean diameter of the TRWP by volume in the spiked biota sample (220 μm) was within 2% of the mean value of the original road dust sample (224 μm) (Table 1). Compared with previous environmental samples characterized by single particle analysis techniques, average TRWP diameter were smaller in tunnel dust compared to road dust while settling pond sediment TRWP were appreciably larger (Table 1). Our single particle analysis techniques characterized differences in TRWP size for various matrices that likely represent differences in environmental aging processes including weathering and aggregation24,25. Taken together, the results of the current manuscript demonstrate that our single particle analysis methods were capable of characterizing TRWP particle size distribution after biota digestion and dual density separation steps which may aid in TRWP identification of environmental biota samples.

Strengths and limitations

The purpose of the current research was to apply suitable analytical techniques including SEM/EDX mapping to characterize the specific physical and chemical properties of individual particles in various biota samples. One of the strengths of this research includes the use of an established weight of evidence framework for increased specificity towards TRWP identification that considers both physical and chemical properties of TRWP using optical microscopy and SEM/EDX as well as preparation techniques including density separation. A potential limitation to the current analysis includes the manual nature of identifying and characterizing particles. Future research can aim to better understand the detection limit and consistency of this approach including statistical analysis. However, previous research has utilized automation via machine learning algorithms and has demonstrated some consistency across both approaches30–32. Therefore, future research can continue to utilize various manual and automated approaches to isolate, identify, and characterize TRWP in biota samples with varying degrees of complexity and to better understand uncertainties with each approach.

Conclusions

We hypothesized the single particle analysis techniques were capable of identifying and characterizing different particle types including TRWP and CMTT in various biota samples. Therefore, our aim was to extend our single particle analysis methods to biota samples including laboratory earthworms and an environmental bivalve sample with the potential for broader environmental applications to aid in understanding the fate, transport, and ecological impact of different particle types. Multiple physical and chemical properties were utilized to identify TRWP and CMTT particles. CMTT particles were black/opaque, jagged shaped, and contained S + Na/Zn with variable amounts of other elements including Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al. TRWP were black/grey/opaque, mostly round or elongated in shape with variable mineral encrustations, and contained S + Zn/Na with variable amounts of Si, K, Mg, Ca, and Al. The identification of CMTT in earthworms demonstrated the feasibility of our approach. Our single particle analysis techniques were further validated by the identification and characterization of TRWP in bivalve samples spiked with road dust. The average TRWP particle size from the road dust spiked biota sample was 126 μm by number and 220 μm by volume with a range of 9 μm to 572 μm which is consistent with TRWP identified from the original road dust sample. These data suggest that the current method for biota digestion, dual density separation, and TRWP characterization is feasible for similar samples and that our single particle analysis methodologies were useful for the characterization of particle size distribution in biota samples. These results may advance the methods for identification and characterizing TRWP and potentially other microplastics in various environmental matrices including biota samples.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank UFZ (Steffen Weyrauch and Thorsten Reemtsma, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research—UFZ, Leipzig, Germany) for the coordination and collection of TRWP in Germany. The authors would also like to thank Tim Barber and Sophie Claes from Environmental Resources Management (ERM) for the coordination and collection of biota sample in France. Additionally, the authors are grateful to Yujin Ducatillon Kim (World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), Tire Industry Project (TIP)) for her facilitation and support.

Author contributions

MK, SCO, BF, TM, FB, and KU designed the experiments. MK and SCO analyzed the data and prepared the Figures. MK and KU wrote the manuscript. All authors (MK, SCO, BF, TM, FB, and KU) reviewed the manuscript, provided edits, and finalized the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

Several authors (MK and KU) are employed by Stantec, a consulting firm that provides scientific advice to the government, corporations, law firms, and various scientific/professional organizations. The work presented here was funded by TIP which operates under the umbrella of WBCSD, is comprised of 10 leading tire companies and serves as a global, voluntary, CEO-led initiative which aims to proactively identify and address the potential human health and environmental impacts of tires to contribute to a more sustainable future. The Stantec authors of this manuscript were retained as consultants to the TIP, and Exponent (author SCO) was retained by Stantec to execute the experimental methodology. Centre Ecotox and Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (authors BF, TM, and FB) were retained as consultants and received funding from TIP. The study design, execution, interpretation, and manuscript preparation were conducted solely by the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.de Ruijter, V. N., Redondo-Hasselerharm, P. E., Gouin, T. & Koelmans, A. A. Quality criteria for microplastic effect studies in the context of risk assessment: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol.10.1021/acs.est.0c03057 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ISO. ISO 472:2013 Plastics - Vocabulary. (2013).

- 3.Kole, P. J., Lohr, A. J., Van Belleghem, F. & Ragas, A. M. J. Wear and tear of tyres: A stealthy source of microplastics in the environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 1410.3390/ijerph14101265 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Wagner, S. et al. Tire wear particles in the aquatic environment—a review on generation, analysis, occurrence, fate and effects. Water Res.139, 83–100. 10.1016/j.watres.2018.03.051 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rochman, C. et al. Rethinking microplastics as a diverse contaminant suite. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.38, 703–711 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreider, M. L., Panko, J. M., McAtee, B. L., Sweet, L. I. & Finley, B. L. Physical and chemical characterization of tire-related particles: comparison of particles generated using different methodologies. Sci. Total Environ.408, 652–659. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.016 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommer, F. et al. Tire abrasion as a major source of microplastics in the environment. Aerosol Air Qual. Res.18, 2014–2028. 10.4209/aaqr.2018.03.0099 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustafsson, M. et al. Properties and toxicological effects of particles from the interaction between tyres, road pavement and winter traction material. Sci. Total Environ.393, 226–240. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.12.030 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unice, K. M., Kreider, M. L. & Panko, J. M. Comparison of tire and road wear particle concentrations in sediment for watersheds in France, Japan, and the united States by quantitative pyrolysis GC/MS analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol.47, 8138–8147. 10.1021/es400871j (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unice, K. M. et al. Characterizing export of land-based microplastics to the estuary - Part II: Sensitivity analysis of an integrated Geospatial microplastic transport modeling assessment of tire and road wear particles. Sci. Total Environ.646, 1650–1659. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.301 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baensch-Baltruschat, B., Kocher, B., Stock, F. & Reifferscheid, G. Tyre and road wear particles (TRWP)—a review of generation, properties, emissions, human health risk, ecotoxicity, and fate in the environment. Sci. Total Environ.733, 137823. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137823 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisentraut, P. et al. Two birds with one Stone—Fast and simultaneous analysis of microplastics: Microparticles derived from thermoplastics and tire wear. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett.5, 608–613. 10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00446 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adachi, K. & Tainosho, Y. Characterization of heavy metal particles embedded in tire dust. Environ. Int.30, 1009–1017. 10.1016/j.envint.2004.04.004 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadle, S. H. & Williams, R. L. Gas and particle emissions from automobile tires in laboratory and field studies. Air Pollut Control Assoc.28, 502–507. 10.1080/00022470.1978.10470623 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dannis, M. L. Rubber dust from the normal wear of tires. Rubber Chem. Technol.47, 1011–1037 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unice, K. M., Kreider, M. L. & Panko, J. M. Use of a deuterated internal standard with pyrolysis-GC/MS dimeric marker analysis to quantify tire tread particles in the environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 9, 4033–4055. 10.3390/ijerph9114033 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams, R. W. & Cadle, S. H. Characterization of tire emissions using an indoor test facility. Rubber Chem. Technol.61, 7–25 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camatini, M. et al. Fractal Shape Analysis of Tire Debris Particles: Preliminary Results and Applications. MRS Proc. 661 (2001). 10.1557/proc-661-kk1.6

- 19.Kupiainen, K. et al. Size and composition of airborne particles from pavement wear, tires, and traction sanding. Environ. Sci. Technol.39, 699–706 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, S., Kwak, J., Kim, H. & Lee, J. Properties of roadway particles from interaction between the tire and road pavement. Int. J. Automot. Technol.14, 163–173. 10.1007/s12239 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swietilik, R., Trojanowska, M., Strzelecka, M. & Bocho-Janiszewska, A. Fractionation and mobility of Cu, Fe, Mn, Pb and Zn in the road dust retained on noise barriers along expressway—a potential tool for determining the effects of driving conditions on speciation of emitted particulate metals. Environ. Pollut. 196, 404–413. 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.10.018 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klöckner, P. et al. Tire and road wear particles in road environment–Quantification and assessment of particle dynamics by Zn determination after density separation. Chemosphere222, 714–721. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.176 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovochich, M. et al. Chemical mapping of tire and road wear particles for single particle analysis. Sci. Total Environ.757, 144085. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144085 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovochich, M. et al. Characterization of tire and road wear particles in urban river samples. Environ. Adv.12, 100385. 10.1016/j.envadv.2023.100385 (2023). https://doi.org [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovochich, M. et al. Characterization of individual tire and road wear particles in environmental road dust, tunnel dust, and sediment. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett.8, 1057–1064. 10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00811 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klöckner, P. et al. Characterization of tire and road wear particles from road runoff indicates highly dynamic particle properties. Water Res.185, 116262. 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116262 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panko, J. M., Chu, J., Kreider, M. L. & Unice, K. M. Measurement of airborne concentrations of tire and road wear particles in urban and rural areas of France, Japan, and the united States. Atmos. Environ.72, 192–199. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.01.040 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 28.More, S. L. et al. Refinement of a microfurnace pyrolysis-GC-MS method for quantification of tire and road wear particles (TRWP) in sediment and solid matrices. Sci. Total Environ.874, 162305. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162305 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barber, T. R. et al. Abundance and distribution of tire and road wear particles in the Seine river, France. Sci. Total Environ.913, 169633. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169633 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Järlskog, I. et al. Differentiating and quantifying carbonaceous (tire, bitumen, and road marking wear) and non-carbonaceous (metals, minerals, and glass beads) non-exhaust particles in road dust samples from a traffic environment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 233, 375 (2022). 10.1007/s11270-022-05847-8

- 31.Rausch, J. et al. Automated identification and quantification of tire wear particles (TWP) in airborne dust: SEM/EDX single particle analysis coupled to a machine learning classifier. Sci. Total Environ.803, 149832. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149832 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Järlskog, I. et al. Concentrations of tire wear microplastics and other traffic-derived non-exhaust particles in the road environment. Environ. Int.170, 107618. 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107618 (2022). https://doi.org:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbasi, S. et al. Distribution and potential health impacts of microplastics and microrubbers in air and street dusts from Asaluyeh County, Iran. Environ. Pollut.. 244, 153–164. 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.039 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Järlskog, I. et al. Traffic-related microplastic particles, metals, and organic pollutants in an urban area under reconstruction. Sci. Total Environ.774, 145503. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145503 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Järlskog, I. et al. Occurrence of tire and bitumen wear microplastics on urban streets and in sweepsand and washwater. Sci. Total Environ.729, 138950. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138950 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klöckner, P. et al. Comprehensive characterization of tire and road wear particles in highway tunnel road dust by use of size and density fractionation. Chemosphere279, 130530. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130530 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hart, L. B. et al. Plastic, it’s what’s for dinner: A preliminary comparison of ingested particles in bottlenose dolphins and their prey. Oceans4, 409–422 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker, B. W. et al. Microplastic and tire wear particle occurrence in fishes from an urban estuary: Influence of feeding characteristics on exposure risk. Mar. Pollut Bull.160, 111539. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111539 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bastos, A. C. et al. Water-extractable priority contaminants in LUFA 2.2 soil: Back to basics, contextualisation and implications for use as natural standard soil. Ecotoxicology23, 1814–1822. 10.1007/s10646-014-1335-2 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masset, T. et al. Effects of tire particles on earthworm (Eisenia andrei) fitness and bioaccumulation of tire-related chemicals. Environ. Pollut.. 368, 125780. 10.1016/j.envpol.2025.125780 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.OECD. Test No. 222: Earthworm reproduction test (Eisenia fetida/ Eisenia andrei). (2016).

- 42.Enders, K., Lenz, R., Beer, S. & Stedmon, C. A. Extraction of microplastic from biota: recommended acidic digestion destroys common plastic polymers. ICES J. Mar. Sci.74, 326–331. 10.1093/icesjms/fsw173 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newbury, D. E. Mistakes encountered during automatic peak identification of minor and trace constituents in Electron-Excited energy dispersive X-Ray microanalysis. Scanning31, 91–101 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.