Abstract

This study proposes BAGWO, a novel hybrid optimization algorithm that integrates the Beetle Antennae Search algorithm (BAS) and the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) to leverage their complementary strengths while enhancing their original strategies. BAGWO introduces three key improvements: the charisma concept and its update strategy based on the sigmoid function, the local exploitation frequency update strategy driven by the cosine function, and the switching strategy for the antennae length decay rate. These improvements are rigorously validated through ablation experiments. Comprehensive evaluations on 24 benchmark functions from CEC 2005 and CEC 2017, along with eight real-world engineering problems, demonstrate that BAGWO achieves stable convergence and superior optimization performance. Extensive testing and quantitative statistical analyses confirm that BAGWO significantly outperforms competing algorithms in terms of solution accuracy and stability, highlighting its strong competitiveness and potential for practical applications in global optimization.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-98816-0.

Keywords: Hybrid algorithm, Grey Wolf Optimizer, Beetle Antennae Search algorithm, Ablation experiments, Global optimization, BAGWO

Subject terms: Computational science, Applied mathematics

Introduction

Optimization is the act of finding the best solution from a decision space given certain constraints and objectives (single or multi-objective)1. In real-world production practices, it is often faced with numerous optimization problems, such as minimizing cost, risk and time and maximizing efficiency, profit and quality2,These optimization problems are prevalent in agricultural production, mechanical design and machining, production scheduling, path planning, aviation and aerospace, water conservancy infrastructure and various other aspects of production and daily life, significantly impacting our lives.

Optimization problems can be categorized into single-objective optimization and multi-objective optimization based on the number of optimization objectives. Multi-objective optimization is often more complex than single-objective optimization, which can be simplified into single-objective optimization problems using methods such as the objective constraint method, weighted sum method, and objective programming method3. In this paper, we focus on studying algorithms for solving single-objective optimization problems. Optimization problems can be classified into constrained optimization problems and unconstrained optimization problems according to the presence or absence of constraints. The most common way to solve constrained optimization problems is to transform them into unconstrained optimization problems using the penalty function method4. Optimization problems can be categorized into linear optimization problems and nonlinear optimization problems based on the characteristics of constraints and the objective function. In nonlinear optimization problems, the relationship between the constraints, the objective function, and the decision variables is nonlinear. Solving nonlinear optimization problems is typically more challenging than solving linear optimization problems. Real-life optimization problems frequently involve nonlinear optimization problems. The objective function corresponding to the optimization problem can be classified into unimodal functions and multimodal functions based on the number of extreme in the feasible domain. A unimodal function has only one global extremum in the feasible domain, which is typically the optimal solution being sought. On the other hand, multimodal functions have multiple extremes in the feasible domain, which makes it easier to get trapped in local extremes when solving for the optimal value. Many objective functions in real-world continuity optimization problems are multimodal functions. There are many classifications of optimization problems. The classification and recognition of optimization problems are helpful in selecting the appropriate optimization methods to solve them.

In order to solve optimization problems, deterministic optimization methods such as linear and nonlinear programming methods were first developed. These methods utilize functional features or gradient information of optimization problems to find optimal solutions and are commonly employed in solving optimization problems5. In contrast, non-deterministic (stochastic) optimization algorithms solve optimization problems based on stochastic properties, which are characterized by their simplicity, ease of implementation, independence from gradient information during optimization, and their effectiveness in optimizing multimodal functions. Therefore, they are increasingly used to solve optimization problems across various domains. In recent decades, non-deterministic optimization algorithms have garnered significant attention and have rapidly developed. They are increasingly utilized to solve optimization problems. When using a non-deterministic optimization algorithm to solve an optimization problem, there is no need to be concerned about the form of the optimization objective function or compute the gradient information. This is because the problem being optimized can be viewed as a black box, where deterministic inputs can be provided to obtain deterministic outputs without needing to consider the internal workings of the black box. By this method, the complexity of solving the optimization problem is significantly simplified. It is only necessary to ensure that the input to the black box meets the optimization constraints, and this can be achieved through the use of a penalty function. Figure 1 illustrates the schematic diagram of the black box model.

Fig. 1.

Simple/Complex optimization problems are regarded as black boxes.

Among the non-deterministic optimization algorithms, the most concerning is the metaheuristic algorithm. Metaheuristic algorithms are optimization algorithms used to address complex issues that cannot be solved using standard approaches6. Metaheuristic algorithms rely on two key search mechanisms in the optimization process: exploration and exploitation. Exploration involves visiting regions that have not been previously explored in the feasible solution globally, aiming to cover as many regions as possible. It helps in escaping local optima. Exploitation, on the other hand, involves a detailed search of explored regions, particularly those likely to contain globally optimal solutions. It is beneficial for enhancing the quality and accuracy of optimization results. Exploration and exploitation are two contrasting search processes. Emphasizing the exploration process improves the likelihood of reaching the vicinity of the actual global optimum, but the quality and stability of the optimization results may not be guaranteed. Emphasizing the exploitation process enhances the quality of the optimization results but also increases the likelihood of getting trapped in a local optimum and prematurely converging. Therefore, the essence of metaheuristic algorithms lies in balancing exploration and exploitation to obtain or approximate the optimal solution. Fortunately, nature is always the best teacher, providing numerous sources of inspiration for metaheuristic algorithms. Many researchers have developed numerous practical metaheuristic algorithms by drawing inspiration from biological behaviors or natural physical phenomena. These algorithms can be classified into the following categories based on their sources of inspiration5,7:

Evolution-based: It simulates the process of natural evolution of organisms. According to Darwin’s concept of “survival of the fittest,” superior variations and their descendants are more likely to survive and reproduce. Typical algorithms include Genetic Algorithm (GA)8, Differential Evolution (DE)9, Evolution Strategy (ES)10, and so on.

Swarm-based: It simulates the social behavior of birds, insects and animals. Typical algorithms include Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)11, Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA)12, Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (AFSA)13, Artificial Bee Colony (ABC)14, Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA)15, Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)16, Chameleon Swarm Algorithm (CSA)5, and so on.

Physics-based: It simulates the laws of nature and natural physical phenomena. Typical algorithms include Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA)17, Light Spectrum Optimizer (LSO)7, Simulated Annealing (SA)18, Water Cycle Algorithm (WCA)19, Chemical Reaction Optimization (CRO)20, and so on.

Human-based: It simulates human body systems, human brain thinking, and human behavior in society. Typical algorithms include Immune Algorithm (IA)21, Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO)22, Artificial Neural Network (ANN)23, and so on.

Others: It includes metaheuristic algorithms that are not inspired by biological behavior or natural physical phenomena. Typical algorithms include Sine-Cosine Algorithm (SCA)24, Yin-Yang-Pair Optimization (YYPO)25, Five-Elements Cycle Optimization (FECO)26, and so on.

The “No Free Lunch” (NFL) theorem states that there is no single metaheuristic algorithm that can solve all types of optimization problems optimally. Each optimization algorithm has its own scope of application27,28. Some metaheuristic algorithms optimize well for unimodal functions but generally perform poorly for multimodal functions. Typical algorithms include GWO, WOA, and others. In contrast, some algorithms optimize well for multimodal functions but perform poorly for unimodal functions. Typical algorithms include the Firefly Algorithm (FA)29, Beetle Antennae Search algorithm (BAS)30, and so on. Therefore, integrating the existing unimodal function-solving advantage algorithms and multimodal function-solving advantage algorithms is an effective approach to improve the comprehensive optimization capability of optimization algorithms without violating the NFL theorem. As mentioned in Mirjalili’s paper24, the research on metaheuristic algorithms is mainly divided into three main directions: improving the current techniques, hybridizing different algorithms, and proposing new algorithms. Among them, improving the current techniques and hybridizing different algorithms are two crucial ways to improve the performance of the algorithms and broaden the use scenarios. There are numerous instances supporting this notion. For improving the current techniques, typical algorithms include IGWO31, MPSO32, IGA33, etc. For hybridizing different algorithms, typical algorithms include, but are not limited to BAS-PSO34, WPO35, SCCSA36, SA-PSO37, etc. However, these improvements or hybridization methods do not work well for both unimodal and multimodal problems at the same time. The purpose of this paper is to hybridize and improve two algorithms that have advantages in solving unimodal and multimodal functions, respectively, in order to improve the overall optimization performance of the proposed hybrid algorithm. It provides a competitive and viable option for solving practical optimization problems.

GWO was proposed by Mirjalili16et al. in 2014 and is inspired by the social hierarchy of grey wolves and the collaborative process of prey hunting. Since its introduction in 2014, GWO has gained widespread adoption in both academic and engineering fields due to its excellent optimization performance and straightforward implementation. However, Makhadmeh38et al. pointed out that the original GWO faces challenges such as a tendency to fall into local optima, high parameter sensitivity, and insufficient global optimization capabilities. Over the past decade, researchers have conducted extensive studies to enhance the optimization capabilities and applicability of the original GWO. In 2024, Makhadmeh and Mirjalili, the inventor of GWO, systematically summarized the development of GWOand its improved versions over the last ten years38. This paper organizes their research findings into two main categories for single-objective optimization improvements: Modified versions and Hybridized versions, as shown in Table 1. Modified versions have significantly enhanced the performance of GWO by incorporating various strategies such as chaos mechanisms, opposition-based learning, and adaptive strategies, making it more effective in handling complex optimization problems. However, these improvements also introduce challenges such as increased computational complexity and heightened parameter sensitivity, which require careful consideration in practical applications. Hybridized versions, on the other hand, combine GWO with other optimization algorithms to leverage their respective strengths, demonstrating exceptional performance in tackling complex, multi-objective, and large-scale optimization problems. Nevertheless, their higher implementation complexity and computational costs may limit their applicability. In the future, the development of GWO will focus on structured population design, adaptive parameter adjustment, and hybrid strategy optimization. These improvements are expected to further enhance the algorithm’s performance and applicability.

Table 1.

GWO and related improvement strategies.

| Improvement approach | Specific improvement strategies | Pros and cons | Related algorithms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified versions | Binary GWO | Use S-shaped and V-shaped transfer functions to convert continuous GWO to binary version for feature selection, text classification, etc. |

Pros: suitable for binary search spaces. Cons: may lose diversity in continuous problems. |

BGWO, BIGWO, SCGWO, RL-GWO, EOCSGWO, etc. |

| Adaptive GWO | Dynamically adjust GWO parameters with adaptive mechanisms for neural network training, power system optimization, etc. |

Pros: balances exploration and exploitation. Cons: increased computational complexity. |

cmaGWO, etc. | |

| Chaotic GWO | Introduce chaotic mapping mechanisms to enhance diversity and avoid local optima. |

Pros: improves global search ability. Cons: sensitive to chaotic map selection. |

SCGWO, etc. | |

| Dynamic GWO | Dynamically adjust wolf positions or population size with nonlinear operators to enhance flexibility and tracking ability. |

Pros: adapts to complex search spaces. Cons: may slow convergence in simple problems. |

VAGWO, etc. | |

| Opposition-based GWO | Introduce opposition-based learning strategies to enhance exploration and avoid local optima. |

Pros: enhances exploration. Cons: may increase computational cost. |

RL-GWO, EOCSGWO, etc. | |

| Structured population GWO | Divide the population into subgroups to enhance diversity and search capabilities. |

Pros: improves diversity. Cons: complex implementation. |

AP-TLB-IGWO, etc. | |

| Fractional GWO | Combine fractional-order techniques for multi-view video super-resolution, natural gas and coal consumption prediction, etc. |

Pros: handles complex systems. Cons: high computational cost. |

FGWO, etc. | |

| Mutation-based GWO | Introduce mutation operations to enhance local search and convergence speed. |

Pros: improves local search. Cons: risk of premature convergence. |

MGWO, etc. | |

| Greedy strategy GWO | Combine greedy selection and crossover operations for multi-objective power flow optimization, economic load dispatch, etc. |

Pros: fast convergence. Cons: may get stuck in local optima. |

G-SCNHGWO, etc. | |

| Hybrid strategy GWO | Combine with other optimization algorithms to enhance global search and convergence speed. |

Pros: balances exploration and exploitation. Cons: increased complexity. |

DE-GWO, etc. | |

| Hybridized versions | Combined with Local Search | Combine with local search algorithms to enhance local search capabilities. |

Pros: improves local search. Cons: may slow global search. |

MbGWOSFS, etc. |

| Combined with swarm intelligence | Combine with swarm intelligence algorithms (e.g., Jaya optimizer, symbiotic organisms search) to enhance global search capabilities. |

Pros: enhances global search. Cons: may increase computational cost. |

DA-GWO, CS-GWO, etc. | |

| Combined with evolutionary algorithms | Combine with evolutionary algorithms to enhance population diversity and global search capabilities. |

Pros: improves diversity. Cons: complex implementation. |

EGWO-GA, etc. | |

| Combined with other algorithms | Combine with other algorithms for specific optimization problems. |

Pros: tailored for specific problems. Cons: limited generalizability. |

ELM-GWO, etc. | |

BAS is a metaheuristic algorithm proposed in 2017 by Jiang30et al., which is inspired by the foraging and mate-seeking behavior of beetles. BAS has the advantages of fewer parameters, better global search capability, being not easy to fall into local optima, and straightforward programming implementation. Due to its simple principles and efficient implementation, BAS has been widely adopted and continuously refined in both academic and engineering fields. Chen39 et al. systematically reviewed recent advancements in BAS, categorizing its single-objective optimization improvement strategies into four main classes, as shown in Table 2. These methods have demonstrated significant optimization results within their respective applicable scopes. Chen39 et al. further highlighted that integrating BAS with other high-performance algorithms represents a promising approach to enhancing its global search capabilities, indicating a fruitful direction for future research.

Table 2.

BAS and related improvement strategies.

| Improvement approach | Specific improvement strategies | Pros and cons | Related algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter adjustment | Adjusts step size, beetle spacing, introduces beetle populations. |

Pros: Enhances global/local search. Cons: High complexity, sensitive to parameters. |

VSBAS, BSAS, BASL, etc. |

| Adaptive mechanisms | Uses inertia weights, elite selection, fallback mechanisms. |

Pros: Fast convergence, robust. Cons: Complexity, local optima risk. |

BAS-ADAM, WSBAS, EBAS, ENBAS, FBAS, etc. |

| Hybrid heuristics | Combines PSO, ABC, FPA, GA, ACO, etc. for global/local search. |

Pros: Combines strengths, versatile. Cons: High complexity, tuning needed. |

BSO, BAS-PSO, BAPSO, MBAS, BAS-ABC, etc. |

| Deep learning | Optimizes neural networks (BP, CNN, ELM) with BAS. |

Pros: Improves training speed/accuracy. Cons: High complexity, resource-heavy. |

BASNNC, BASZNN, BAS-CNN, etc. |

From the above analysis of GWO and BAS, it is evident that BAS boasts advantages such as a simple structure, fewer parameters, and strong global search capabilities, particularly excelling in optimizing multimodal functions, although its local search ability is relatively weak. On the other hand, GWO also features a simple structure and fewer parameters, with strong local search capabilities, but its global search ability is somewhat limited. The two algorithms complement each other’s strengths. Based on the analysis and future prospects presented in the studies by Makhadmeh38and Chen39, integrating the two algorithms with complementary characteristics and designing improvement strategies tailored to their respective features holds promise for developing a highly competitive global optimization algorithm. Therefore, this study integrates BAS and GWO, proposing improvement strategies for BAS’s antenna length update, GWO’s population summoning mechanism, and the balance between exploration and exploitation, resulting in a high-performance new algorithm named BAGWO. This paper will conduct a detailed study and discussion on the design, improvement strategies, and overall performance of BAGWO.

The main research and contributions of this paper are listed as follows:

A novel algorithm named BAGWO is proposed by hybridizing GWO and BAS. This algorithm replaces grey wolves with beetles and simplifies the hierarchical structure. Key improvements include the swarm position update strategy, the local exploitation frequency switching strategy, and the beetle antenna length update strategy. Experimental results demonstrate that BAGWO significantly outperforms BAS and GWO in comprehensive optimization performance, with ablation tests further confirming the effectiveness of these enhancements.

BAGWO incorporates three improvement strategies: it prioritizes global exploration in the early stages to increase the likelihood of approaching the global optimum, while focusing on local exploitation in the later stages to enhance the stability and precision of the optimization results. Extensive experiments validate the effectiveness of this design approach.

The optimization performance of BAGWO is rigorously evaluated using 24 benchmark functions from CEC2005 and CEC2017, as well as eight challenging real-world engineering problems. Statistical analysis shows that BAGWO exhibits strong competitiveness in comprehensive optimization performance and global optimization compared to other widely-used optimization algorithms.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, a brief overview of the fundamental principles and core characteristics of GWO and BAS is provided. In Sect. 3, the BAGWO, formed by integrating and improving GWO and BAS, is introduced, along with a detailed description of the improvement strategies, algorithm principles, and pseudocode. In Sect. 4, the optimization performance of the proposed BAGWO is tested by CEC benchmark functions, and the test results are analyzed using statistical methods. In Sect. 5, the proposed BAGWO is applied to real-world engineering problems. Finally, in Sect. 6, the proposed BAGWO is summarized, and future applications are outlined.

Background

This section briefly introduces the BAS and the GWO, discusses the inspiration behind the two algorithms and the abstract model, and provides the necessary background knowledge for the content in Sect. 3.

Beetle antennae search algorithm

As shown in Fig. 2(a), which depicts the foraging process of the beetle, the length of the beetle’s antennae tends to be longer than its body length. When foraging for food or searching for a mate, the beetles use two antennae to randomly explore the nearby area. When a higher odor concentration is detected on one side, the beetles adjust their body in that direction and move. Conversely, they adjust their body in the opposite direction and move towards the higher odor concentration until reaching the vicinity of food or a mate. Using the example of searching for food, the action steps of a beetle can be broken down as follows:

Fig. 2.

Beetle antennae search algorithm model.

A beetle arrives in an area where food is available.

The orientation of the beetle’s head is stochastic, utilizing information from the left and right antennae to detect the concentration of food odors in the directions of both antennae.

The beetle rotates its body towards the side with a higher odor concentration on the antennae and moves forward a certain distance.

Repeat steps (2) and (3) until food is found.

The BAS optimization algorithm model can be obtained through the bionic principle of the beetle’s foraging behavior. As shown in Fig. 2(b) the beetle’s body is abstracted as a center of mass, the left and right antennae are line segments of the same length extending from the center of mass in opposite directions, and the length of a single antennae is  . The process of beetle foraging can be described as follows:

. The process of beetle foraging can be described as follows:

The initial time

initializes the initial position

initializes the initial position  of the beetle, defines the length of the antennae at the initial time of the beetle as

of the beetle, defines the length of the antennae at the initial time of the beetle as  , and the orientation

, and the orientation  of the beetle’s head is randomly given.

of the beetle’s head is randomly given.At time

, the beetle detects the food position through its antennae, and calculates the positions

, the beetle detects the food position through its antennae, and calculates the positions  and

and  of the left and right antennae respectively. The calculation formulas of the antennae positions are as shown in Eq. (1).

of the left and right antennae respectively. The calculation formulas of the antennae positions are as shown in Eq. (1).

|

1 |

Here,

is the angle of the beetle antennae relative to the coordinate system at time

, and the function

represents the calculation function of the beetle antennae coordinate. The

in the function input is used to judge the left and right of the antennae.

-

(3)

Obtaining the food concentration at both antennae ends, the beetle then moves a distance

along the antennae on the side with the higher food concentration and randomizes the orientation of the beetle’s head, and the concentration of the odor (also known as fitness) is calculated as shown in Eq. (2).

along the antennae on the side with the higher food concentration and randomizes the orientation of the beetle’s head, and the concentration of the odor (also known as fitness) is calculated as shown in Eq. (2).

|

2 |

Where

represents the fitness function and

represents the position at the antennae’ end.

-

(4)

Update the length

of the beetle antennae and the step length

of the beetle antennae and the step length  of the beetle ‘s movement. The update formula is as shown in Eq. (3) and Eq. (4).

of the beetle ‘s movement. The update formula is as shown in Eq. (3) and Eq. (4).

|

3 |

|

4 |

Where the functions

and

are the length update function of the beetle antennae and the step length update function of the beetle, respectively.

-

(5)

Repeat steps (2) and (4) until the optimization results reach a certain accuracy

, or reach the maximum number of iteration times N.

, or reach the maximum number of iteration times N. -

(6)

One of the conditions for the solution to reach the iteration termination of precision

is as follows.

is as follows.

|

5 |

-

(7)

Output the optimization result

and its corresponding fitness

and its corresponding fitness  and the actual number of iteration times

and the actual number of iteration times  , the solution is finished.

, the solution is finished.

BAS shows good application potential in optimization problems with its unique advantages. The main features of the algorithm include40,41:

Avoiding local optima: Compared with the gradient descent algorithm, BAS can effectively escape local optimal solutions by randomly adjusting the search direction and incorporating an appropriate step length update rule. This enhances the likelihood of discovering the global optimal solution.

Easy to implement: The structure and implementation process of BAS are very simple. Compared with the gradient descent algorithm, BAS does not need the gradient information of the objective function, which simplifies the calculation process.

Suitable for low-dimensional optimization problems: When dealing with low-dimensional optimization problems, BAS performs particularly well. Without knowing the details of the objective function, it can perform effective optimization calculations, especially for solving multimodal optimization problems.

Easy to integrate with other algorithms: Due to its simple form, BAS is easy to combine with other algorithms to form new hybrid optimization algorithms without significantly increasing the complexity of the algorithm.

Grey Wolf optimizer

As a carnivore that feeds on small to medium-sized prey such as goats, bison, and hares, the grey wolf often hunts prey predominantly as a group. Similar to the hierarchy that exists in human society, there are different social classes within the grey wolf group, which can be classified as  -wolf,

-wolf,  -wolf,

-wolf,  -wolf, and

-wolf, and  -wolf according to the class, in order from high to low, as shown in Fig. 3(a)16. Where

-wolf according to the class, in order from high to low, as shown in Fig. 3(a)16. Where  -wolf is the leader of a pack of grey wolves and is responsible for directing the hunting process of the entire pack,

-wolf is the leader of a pack of grey wolves and is responsible for directing the hunting process of the entire pack,  -wolf is the subordinate of

-wolf is the subordinate of  -wolf and takes orders from

-wolf and takes orders from  -wolf and helps

-wolf and helps  -wolf in decision making and directing other lower ranked wolves,

-wolf in decision making and directing other lower ranked wolves,  -wolf is the subordinate of

-wolf is the subordinate of  - and

- and  -wolf, and is responsible for overseeing and directing

-wolf, and is responsible for overseeing and directing  -wolf, and

-wolf, and  -wolf are the lowest ranked wolves in the pack of grey wolves, and are subservient to the dominance and directing of the other ranked wolves16,42.

-wolf are the lowest ranked wolves in the pack of grey wolves, and are subservient to the dominance and directing of the other ranked wolves16,42.

Fig. 3.

Grey wolf optimizer model16.

When hunting prey, grey wolf packs can be broken down into the processes of stalking and approaching the prey, encircling the prey, and attacking the prey until it is captured. The hunting process of grey wolf packs can be specifically broken down into the following steps:

Prey found in an area.

Stalking, approaching prey.

Chasing, surrounding, and harassing prey until it stops moving.

Attacking prey.

Through the bionics principle of grey wolf predation, the GWO model can be obtained. The specific algorithm details can be viewed in the article written by Mirjalili16 et al. in 2014. As shown in Fig. 3(b), the optimization procedure of GWO is as follows:

Initialize the grey wolves’ position and the parameters

in the algorithm.

in the algorithm.update the position of each grey wolf.

Update the fitness of each grey wolf.

loop procedure (2)-(3) until the maximum number of iterations is reached.

Output the optimal calculation results.

GWO solves the optimization problems by simulating the group hunting behavior of grey wolves. It has unique characteristics and has been widely used in practical engineering applications. The main features of the algorithm include:

The parameters are less, and the implementation is relatively simple: the number of parameters involved in the grey wolf algorithm is small, and the parameter adjustment is simple.

Excellent local search ability: The algorithm has excellent local search ability, especially suitable for the optimization of unimodal functions, and has satisfactory results.

Without gradient information: GWO does not need to calculate the derivative during the operation, and is suitable for the optimization of various types of non-differentiable or derivative difficult to obtain problems.

Poor global search ability and sensitive to the initial distribution: GWO in the global optimization problem solving is general, especially for the multimodal functions’ optimization effect is not as good as its unimodal functions’ optimization effect; In addition, GWO is sensitive to the initial distribution of the swarm, the different initial distribution of the swarm has an impact on its optimization performance.

In summary, GWO has the advantages of few parameters, relatively easy to implement, and no derivative information is required in the solution process. It is especially suitable for solving unimodal function optimization problems, but the disadvantage is that the effect of solving multimodal function problems is general, and it is sensitive to the initial distribution of the swarm.

Proposed BAGWO

In this section, we introduce the newly proposed hybrid optimization algorithm, which combines the advantages of BAS and GWO. The comprehensive optimization performance of the hybrid algorithm is expected to surpass that of the two original algorithms. The direction of movement during the exploration of the BAS is determined by the information received at the two antennae. The optimization process does not require the use of gradient information, making it highly effective in optimizing low-dimensional problems and multimodal functions. In addition, since the BAS is simple enough, combining it with other algorithms does not significantly increase the complexity. GWO has fewer parameters, is relatively easy to implement, has good local search ability, and has an exceptional optimization effect on unimodal functions. It can be seen that BAS and GWO complement each other’s advantages and are very suitable for cross-integration to enhance the two algorithms. The enhanced algorithm can yield significant optimization benefits for both unimodal and multimodal functions.

The combination of BAS and GWO forms BAGWO. The advantages of GWO and BAS are preserved in BAGWO, with enhancements to the exploration and exploitation strategies of BAGWO. The optimization solving process within BAGWO can be divided into two distinct phases based on the collective and individual behaviors of search agents in the swarm: global exploration phase and local exploitation phase.

Global exploration phase: As shown in Fig. 4(a), the schematic diagram illustrates the principle of BAGWO. In BAGWO, the search agent is replaced from a grey wolf to a beetle. The position updating method of each search agent in the respective swarm during the search for the optimal solution precisely mirrors the position updating method of a beetle in the BAS. This method ensures that the search agents consistently moves towards a non-inferior solution during the position updating process. Unlike GWO, each search agent in BAGWO is treated as an equal individual without social hierarchy. When updating its position, a search agent moves toward the direction indicated by the Historically Best Search Agent (HBSA), responding to its calling and attraction. The HBSA refers to the agent with the best fitness value since the start of the optimization process, continuously updated and tracked during the search. Through this global exploration mechanism, all search agents update their positions under the guidance of the HBSA while performing local exploitation. This approach helps focus the search on the region containing the actual global optimum and improves global optimization performance.

Fig. 4.

Position update in BAGWO.

Local exploitation phase: A single search agent in the BAGWO swarm during local exploitation is illustrated in Fig. 4(b), where  represents the step length of the search agent as it moves and

represents the step length of the search agent as it moves and  represents the number of times for local exploitation under a certain number of iterations. It can be seen that in the local exploitation process, the search agent can only exploit in a region centered on the starting movement point with a radius of

represents the number of times for local exploitation under a certain number of iterations. It can be seen that in the local exploitation process, the search agent can only exploit in a region centered on the starting movement point with a radius of  (The subscript

(The subscript  denotes the index of the search agent within the swarm, while

denotes the index of the search agent within the swarm, while  represents the current number of local exploitation), and each search agent of the swarm performs such a local exploitation process. In the process of local exploitation, each search agent moves according to how beetles update their positions in BAS. They determine the direction of movement based on the fitness information received from their two antennae. While effectively exploring the local region, this approach also helps to escape from local optima. After the local exploitation process of all search agents in the swarm, the HBSA is updated and recorded to update the historical global optimal solution.

represents the current number of local exploitation), and each search agent of the swarm performs such a local exploitation process. In the process of local exploitation, each search agent moves according to how beetles update their positions in BAS. They determine the direction of movement based on the fitness information received from their two antennae. While effectively exploring the local region, this approach also helps to escape from local optima. After the local exploitation process of all search agents in the swarm, the HBSA is updated and recorded to update the historical global optimal solution.

The HBSA’s position at iteration times  is denoted as

is denoted as  , and the corresponding fitness is

, and the corresponding fitness is  , the position of the search agents in the swarm after the execution of the local exploitation process is

, the position of the search agents in the swarm after the execution of the local exploitation process is  , and the corresponding fitness is

, and the corresponding fitness is  , the update formula for the position of HBSA

, the update formula for the position of HBSA  is shown in Eqs. (6) and (7). Equation (6) represents that after all search agents in the swarm complete one round of searching, both their current fitness values and the historical best fitness value from the previous iteration are sorted. This process identifies the best fitness value

is shown in Eqs. (6) and (7). Equation (6) represents that after all search agents in the swarm complete one round of searching, both their current fitness values and the historical best fitness value from the previous iteration are sorted. This process identifies the best fitness value  for the current iteration. Equation (7), on the other hand, utilizes this best fitness value

for the current iteration. Equation (7), on the other hand, utilizes this best fitness value  obtained from Eq. (6) to derive the corresponding historical position

obtained from Eq. (6) to derive the corresponding historical position  of the search agent (expressed through an inverse function). It is essential to note that the

of the search agent (expressed through an inverse function). It is essential to note that the  we aim to solve for must be based on the actual trajectory data of the BAGWO optimizer’s search process.

we aim to solve for must be based on the actual trajectory data of the BAGWO optimizer’s search process.

|

6 |

|

7 |

In BAGWO, not only are the characteristics of BAS and GWO combined, but also the charisma (newly proposed concept), antennae length switching strategy, and the switching strategy of the frequency of local exploitation have been researched and improved to varying degrees. These improvements enhance the comprehensive optimization performance of BAGWO. In the following subsections, the specific details of these improvements will be elaborated.

Hybrid algorithm improvement strategy

The charisma and its update strategy

The charisma, derived from GWO, indicates the leadership or influence of the α-wolf over other grey wolves. In this paper, the charisma refers to the HBSA’s ability to attract search agents within the BAGWO framework, represented as a real number between 0 and 1. A charisma closer to 1 means that the HBSA strongly draws search agents towards its position, causing them to move there immediately when the charisma is 1. Conversely, as the charisma approaches 0, the HBSA’s attraction diminishes, leading search agents to return to their original positions, remaining stationary when the charisma equals 0.

For swarm intelligence optimization algorithms, the trade-off between exploration and exploitation is a crucial consideration. Exploration signifies the algorithm’s ability to conduct a global search to explore unexplored regions, while exploitation represents the algorithm’s local search capability to meticulously exploit already explored regions. The actual computational results demonstrate that emphasizing exploration in the early stage and exploitation in the later stage is conducive to improving the algorithm’s capability to discover the true optimal solution. Therefore, it is necessary to adjust the charisma based on the number of iterations. A smaller charisma should be used when the number of iterations is small, and a larger charisma when the number of iterations is large, until it reaches 1.0.

In mathematics, the sigmoid function is referred to as a growth curve due to its S-shaped curve. When the input is small, the output is close to 0, while a large input yields an output close to 1. Therefore, the sigmoid function is particularly suitable for representing the relationship between the charisma  and the number of iterations

and the number of iterations  , and the functional relationship between the two is given directly in Eq. (8).

, and the functional relationship between the two is given directly in Eq. (8).  in Eq. (8) represents the maximum number of iterative running times,

in Eq. (8) represents the maximum number of iterative running times,  represents the shape coefficient. The larger

represents the shape coefficient. The larger  is, the more drastic the change of the charisma

is, the more drastic the change of the charisma  is, and vice versa, the gentler the change is.

is, and vice versa, the gentler the change is.  represents the final charisma, which is a parameter that determines the final level of charisma. The smaller the value of

represents the final charisma, which is a parameter that determines the final level of charisma. The smaller the value of  , the larger the range of swarm aggregation at the maximum number of iterations

, the larger the range of swarm aggregation at the maximum number of iterations  , which is beneficial for global exploration but detrimental to local exploitation, potentially affecting the stability of the optimization results. Conversely, as the value of

, which is beneficial for global exploration but detrimental to local exploitation, potentially affecting the stability of the optimization results. Conversely, as the value of  approaches 1, the range of swarm aggregation becomes smaller at the maximum number of iterations

approaches 1, the range of swarm aggregation becomes smaller at the maximum number of iterations  , which aids in local exploitation during the later stages of the algorithm and helps improve solution stability, but also increases the probability of falling into local optimum solutions. The trend of the charisma is shown in Fig. 5(a), and in the BAGWO proposed in this paper, the value of the shape factor

, which aids in local exploitation during the later stages of the algorithm and helps improve solution stability, but also increases the probability of falling into local optimum solutions. The trend of the charisma is shown in Fig. 5(a), and in the BAGWO proposed in this paper, the value of the shape factor  is set to 100 by default, and the value of the final charisma

is set to 100 by default, and the value of the final charisma  is typically around 1, commonly approximated as 0.99.

is typically around 1, commonly approximated as 0.99.

|

8 |

Fig. 5.

The charisma, beetle antennae length, and the frequency of local exploitation variation over iterations.

Switching strategy of antennae length decay rate

In BAGWO, the antenna length of the search agent represents the ratio of the detection and perception distance to the distance between the upper and lower bounds of the decision variables during the optimization process. This ratio is a relative value between 0 and 1. When this value is 1, it means that the distance of the search agent’s unilateral antenna length is equal to the distance between the upper and lower bounds of the decision variables. It is important to note that in the native BAS algorithm, the antenna length

is equal to the distance between the upper and lower bounds of the decision variables. It is important to note that in the native BAS algorithm, the antenna length  is an absolute value, which differs from the concept presented in this paper.

is an absolute value, which differs from the concept presented in this paper.

To enhance the accuracy of the optimization solution, it is necessary for the antennae length of the search agents to decrease progressively throughout the iterative optimization process. There are various methods to adjust the antennae length, among which the commonly used formula is shown in Eq. (9)30, in which  represents the unilateral antennae length of the search agents when the number of iterations is

represents the unilateral antennae length of the search agents when the number of iterations is  ,

,  represents the decay rate of the search agents’ antennae length (It represents the rate of change in the antennae length of the search agent), and

represents the decay rate of the search agents’ antennae length (It represents the rate of change in the antennae length of the search agent), and  represents the minimum antennae length. Equation (9) can be simplified to the form of Eq. (10) when

represents the minimum antennae length. Equation (9) can be simplified to the form of Eq. (10) when  is set to be 0, in which

is set to be 0, in which  represents the initial antennae length of the beetle.

represents the initial antennae length of the beetle.

|

9 |

|

10 |

After benchmarking, it was found that there are limitations in updating the antennae length using the approach shown in Eqs. (9) and (10). Some benchmark functions are well-optimized when the Antennae Length Decay Rate (ALDR)  is large, while others are well-optimized when the ALDR is small. In order to solve the matching problem of the ALDR

is large, while others are well-optimized when the ALDR is small. In order to solve the matching problem of the ALDR  is small. In order to solve the matching problem of the ALDR

is small. In order to solve the matching problem of the ALDR  , the approach shown in Fig. 5(b) is adopted. A larger ALDR

, the approach shown in Fig. 5(b) is adopted. A larger ALDR  is used before a certain iteration times

is used before a certain iteration times  , and a smaller ALDR

, and a smaller ALDR  is used after

is used after  . The corresponding antennae length for an iteration times of

. The corresponding antennae length for an iteration times of  is the switching point antennae length, denoted by

is the switching point antennae length, denoted by  . In the actual parameter setting, since the solution accuracy is often related to the final antennae length, and people are more sensitive to the value of antennae length than the ALDR

. In the actual parameter setting, since the solution accuracy is often related to the final antennae length, and people are more sensitive to the value of antennae length than the ALDR  , It is more intuitive to express the antennae length updating formula as a function of the final antennae length and the number of iterations as shown in Eq. (11), where

, It is more intuitive to express the antennae length updating formula as a function of the final antennae length and the number of iterations as shown in Eq. (11), where  can be calculated by Eq. (12), and the coefficients

can be calculated by Eq. (12), and the coefficients  and

and  in Eq. (11) represent the pre- and post- antennae length factors, which can be calculated by Eq. (13) and Eq. (14), respectively.

in Eq. (11) represent the pre- and post- antennae length factors, which can be calculated by Eq. (13) and Eq. (14), respectively.

|

11 |

|

12 |

|

13 |

|

14 |

There is a connection between the parameter selection of  and the maximum iteration times

and the maximum iteration times  , when the maximum iteration times

, when the maximum iteration times  is small, in order to ensure enough exploration times to avoid falling into a local optimum,

is small, in order to ensure enough exploration times to avoid falling into a local optimum,  should take a larger value. Conversely, when the maximum iteration times

should take a larger value. Conversely, when the maximum iteration times  is large, it can be ensured that the solution space is sufficiently explored, and a relatively small value of

is large, it can be ensured that the solution space is sufficiently explored, and a relatively small value of  should be taken to ensure that the solution space is sufficiently exploited. Equation (15) is the empirical relationship between

should be taken to ensure that the solution space is sufficiently exploited. Equation (15) is the empirical relationship between  and

and  , and the middle square bracket in the formula indicates upward rounding.

, and the middle square bracket in the formula indicates upward rounding.

|

15 |

The frequency of local exploitation update strategy

In order to make the algorithm focus on exploration in the early stage, faster and better to reach the actual optimal solution neighborhood and to reduce the running cost of the algorithm to some extent. Another useful improvement is to couple the frequency of local exploitation with the number of iterations of the algorithm, and the function relationship between the two is in the form of cosine function, as shown in Fig. 5(c). Through this mechanism, the swarm is able to maintain extensive global exploration during the early iterations. As the iteration progresses and the charisma value  increases, the swarm gradually shifts its focus towards local exploitation. Consequently, the frequency of local exploitation can be appropriately reduced in this phase. Local exploitation is a process of searching for the optimal solution only within the local area of the search space, and it is a concept in contrast to global exploration. The specific functional relationship is shown in Eq. (16), where

increases, the swarm gradually shifts its focus towards local exploitation. Consequently, the frequency of local exploitation can be appropriately reduced in this phase. Local exploitation is a process of searching for the optimal solution only within the local area of the search space, and it is a concept in contrast to global exploration. The specific functional relationship is shown in Eq. (16), where  represents the current iteration times,

represents the current iteration times,  represents the maximum iteration running times,

represents the maximum iteration running times,  represents the local maximum exploitation times, which is a constant, and

represents the local maximum exploitation times, which is a constant, and  represents the frequency of local exploitation corresponding to the current iteration times. The square brackets in Eq. (16) represent upward rounding, so the variation rule of the frequency of local exploitation with the number of iterations is actually shown as the horizontal line in Fig. 5(c), and the number of horizontal lines is equal to

represents the frequency of local exploitation corresponding to the current iteration times. The square brackets in Eq. (16) represent upward rounding, so the variation rule of the frequency of local exploitation with the number of iterations is actually shown as the horizontal line in Fig. 5(c), and the number of horizontal lines is equal to  .

.

|

16 |

Summary of parameters in BAGWO

Summarizing the above introduction, there are a total of five parameters that need to be set when BAGWO is actually used, which are described as follows.

, Number of search agents in the swarm: In general, the more search agents in the swarm, the better the optimization performance of the algorithm. However, this improvement comes at the cost of increased time consumption. Considering the balance between the effectiveness of the solution to the optimization problem and the time consumption, it is generally recommended that the number of search agents falls within the range of 5 to 50, with 30 being a commonly accepted value.

, Number of search agents in the swarm: In general, the more search agents in the swarm, the better the optimization performance of the algorithm. However, this improvement comes at the cost of increased time consumption. Considering the balance between the effectiveness of the solution to the optimization problem and the time consumption, it is generally recommended that the number of search agents falls within the range of 5 to 50, with 30 being a commonly accepted value. , Initial antennae length: The initial length of the search agent’s antennae is a relative value ranging from 0 to 1. The greater the value, the larger the initial exploration space. A commonly used value is 1.0.

, Initial antennae length: The initial length of the search agent’s antennae is a relative value ranging from 0 to 1. The greater the value, the larger the initial exploration space. A commonly used value is 1.0. , Maximum number of iteration times: If the number of iterations exceeds

, Maximum number of iteration times: If the number of iterations exceeds  , the algorithm stops running and outputs the calculation results.

, the algorithm stops running and outputs the calculation results. , Final charisma value: The charisma when the number of iterations reaches the maximum number of iteration times

, Final charisma value: The charisma when the number of iterations reaches the maximum number of iteration times  , which generally takes the value of 0.99.

, which generally takes the value of 0.99. , The maximum frequency of local exploitation for each search agent: The smaller the value of

, The maximum frequency of local exploitation for each search agent: The smaller the value of  , the faster the algorithm optimizes the solution. However, the corresponding optimization performance will decrease to some extent. Conversely, the larger

, the faster the algorithm optimizes the solution. However, the corresponding optimization performance will decrease to some extent. Conversely, the larger  is, the better the optimization performance, but the speed of optimizing the solution will decrease. Considering the balance between the effectiveness and time consumption of the optimization problem solution, the value of the maximum frequency of local exploitation is generally recommended to be between 2 and 20.

is, the better the optimization performance, but the speed of optimizing the solution will decrease. Considering the balance between the effectiveness and time consumption of the optimization problem solution, the value of the maximum frequency of local exploitation is generally recommended to be between 2 and 20.

In practical applications, the selection of algorithm parameters varies based on the specific requirements of the tasks being optimized. For tasks that are not sensitive to computation time, high configuration parameters can be selected. in this case, the optimization performance of BAGWO can be released enough. For optimization tasks that are time-sensitive, low configuration parameters should be chosen, in this case, the optimization performance of BAGWO is somewhat limited, but it still yields acceptable results.

Computational procedures and pseudo-code of BAGWO

A detailed description of how BAGWO is formed and improved is given above, this subsection presents the detailed computational procedures and pseudo-code of BAGWO. The detailed procedures are given below.

Define the objective function

to be solved for optimization, where

to be solved for optimization, where  is the decision variable of the optimization problem, a n-dimensional vector, and the upper and lower bounds corresponding to the decision variable

is the decision variable of the optimization problem, a n-dimensional vector, and the upper and lower bounds corresponding to the decision variable  are

are  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.Initialize the algorithm parameters, and assign initial values to the number of search agents

, the initial antennae length

, the initial antennae length  , the maximum iteration times

, the maximum iteration times  , the final charisma value

, the final charisma value  , and the local initial exploration times

, and the local initial exploration times  for BAGWO.

for BAGWO.The initial distribution of the swarm was sampled using the Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) method to obtain the initial decision variable values

. It should be noted that random uniform sampling is also an optional sampling method.

. It should be noted that random uniform sampling is also an optional sampling method.Calculate anterior antennae length coefficient

by Eq. (13). Determine the iteration times

by Eq. (13). Determine the iteration times  by Eq. (15), corresponding to the transition of antennae length decay rate.

by Eq. (15), corresponding to the transition of antennae length decay rate.Calculate initial antennae length decay rate, contained within Eq. (11).

Update the frequency of local exploitation of the search agents

by Eq. (16).

by Eq. (16).-

For each search agent in the swarm, update its position by the movement mode of the beetle in BAS. For any search agent in the swarm, the specific steps are as follows:

- Randomly initialize the orientation of the search agent, use an n-dimensional vector to represent this orientation, and normalize it.

|

17 |

In the Eq. (17),  is the generated random n-dimensional vector,

is the generated random n-dimensional vector,  is the result of normalization, the norm in the equation is the Euclidean norm.

is the result of normalization, the norm in the equation is the Euclidean norm.

-

b)

Calculate the left antenna end position

and the right antenna end position

and the right antenna end position  of the search agent.

of the search agent.

|

18 |

In Eq. (18),  is the position of the search agent center,

is the position of the search agent center,  in the superscript represents the number of current iteration times,

in the superscript represents the number of current iteration times,  represents the frequency of local exploitation, and

represents the frequency of local exploitation, and  represents the serial number of search agent in the swarm.

represents the serial number of search agent in the swarm.

-

c)

Then the fitness

,

,  corresponding to the end of the left and right antennae of the search agent can be calculated.

corresponding to the end of the left and right antennae of the search agent can be calculated. -

d)

Calculate the new position of the search agent according to the fitness.

If

|

19 |

|

20 |

-

2)

If

|

21 |

In Eq. (20) and Eq. (21),  is the symbol function,

is the symbol function, represents the fitness of the

represents the fitness of the  -th search agent in the global iteration times

-th search agent in the global iteration times  .

.

-

e)

Repeat steps a) to d) until the local exploitation is completed for

times,

times,  .

.

-

(8)

The position

and the fitness

and the fitness  of the HBSA are updated according to Eqs. (6) and (7) with

of the HBSA are updated according to Eqs. (6) and (7) with  in the superscript representing the current iteration times.

in the superscript representing the current iteration times. -

(9)

Summons the search agents in the swarm to move in the direction of the HBSA. For any search agent in the swarm, the formula for the movement of the search agent is as follows.

|

22 |

-

(10)

If

, Calculate hind antennae length coefficient

, Calculate hind antennae length coefficient  by Eq. (14), Update antennae length decay rate, contained within Eq. (11).

by Eq. (14), Update antennae length decay rate, contained within Eq. (11). -

(11)

Update the charisma according to Eq. (8).

-

(12)

Update the antennae length of the search agents according to Eq. (11).

-

(13)

Runs the above steps (6)-(12) until the maximum number of iteration times

is reached or other iteration convergence conditions are satisfied.

is reached or other iteration convergence conditions are satisfied. -

(14)

Output the final optimal result,

and

and  .

.

The pseudo-code is shown in Algorithm 1. The MATLAB source code and other resources on BAGWO are available at https://github.com/auroraua/BAGWO.

Algorithm 1: BAGWO

Results and discussion

In this section, the proposed BAGWO and other common competitive optimization algorithms are tested on 24 benchmark functions, and the test results are analyzed using statistical analysis methods. The algorithms involved in the comparison, their parameter settings, benchmark functions selection, statistical analysis methods, and conclusions are described in detail below.

Benchmark functions selection

The Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) is held annually to explore the topic of evolutionary computation from theory to practical application. During the annual CEC meeting, a set of benchmark functions is introduced to assess the performance of different optimization algorithms in an objective and fair manner. In unconstrained single-objective optimization, benchmark functions mainly include unimodal functions, multimodal functions, hybrid functions, and compositional functions16,36, The differences between each function are as follows:

Unimodal functions: In a given interval, this type of function has only one strictly real-valued local maxima or local minima. These functions are primarily utilized to assess the convergence speed and optimization capability of the algorithm.

Multimodal functions: In a given interval, this type of function has multiple real-valued local maximum or local minimum. These functions are primarily used to assess the local optimal escape ability and global exploration ability of the algorithm.

Hybrid functions: This type of function is a hybrid of several different unimodal and multimodal functions that exhibit distinct characteristics in various regions. It is primarily used to examine the ability of optimization algorithms to flexibly switch between different search stages, search areas, and search strategies.

Compositional functions: This type of function is formed by combining several different unimodal or multimodal functions according to specific rules, resulting in a completely new and complex function. The optimization difficulty of these combined functions is generally greater than that of the above three categories of benchmark functions. A small but essential set of combined functions is placed within the benchmark function collection to challenge the performance of optimization algorithms and to identify those algorithms that still perform well under complex conditions.

Algorithms involved in the comparison and their parameter settings

In order to evaluate the performance and effectiveness of the proposed BAGWO, 14 commonly used competitive optimization algorithms are selected, including classic algorithms such as DE, GA, PSO, SA. It also includes competitive recently proposed algorithms such as GWO, IGWO, CSA, BAS, Dragonfly Algorithm (DA)47, Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm (GOA)48, Moth-Flame Optimization algorithm (MFO)45, Multi-Verse Optimizer (MVO)44, SCA, WOA. Table 4 shows the parameter settings of BAGWO and 14 other algorithms in this paper. Apart from the parameters for the BAGWO algorithm, the parameters for the other algorithms are set to the default values used or recommended in their original algorithm publications. It is important to note that due to many algorithms involved in the comparisons, adjusting their parameters would increase the complexity of the problem; therefore, their parameter settings remain unchanged throughout all the benchmark tests in this paper. For the BAGWO algorithm, setting the parameter  to 1.0 aims to maximize the search range during its initial run. The value

to 1.0 aims to maximize the search range during its initial run. The value  =0.99 is the conventional default parameter mentioned in Sect. 3.1.1, while

=0.99 is the conventional default parameter mentioned in Sect. 3.1.1, while  indicates that each search agent can perform a maximum of 10 local exploitations during the initial optimization phase. A smaller

indicates that each search agent can perform a maximum of 10 local exploitations during the initial optimization phase. A smaller  may result in insufficient local exploration, so 10 is considered a more suitable value.

may result in insufficient local exploration, so 10 is considered a more suitable value.

Table 4.

All algorithms parameter settings.

| Algorithm | Parameters | Algorithm category |

|---|---|---|

| All algorithms |

|

|

| BAGWO |

|

|

| DE |

|

Classic algorithms |

| GA |

|

|

| PSO |

|

|

| SA |

|

|

| BAS |

|

Recently proposed algorithms |

| CSA |

|

|

| DA |

|

|

| GOA |

|

|

| GWO |

(The variable (The variable decreases linearly from 2 to 0.) decreases linearly from 2 to 0.) |

|

| IGWO |

(The variable (The variable decreases linearly from 2 to 0.) decreases linearly from 2 to 0.) |

|

| MFO |

(The variable (The variable decreases linearly from − 1 to −2.) decreases linearly from − 1 to −2.) |

|

| MVO |

|

|

| SCA |

|

|

| WOA |

(The variable (The variable decreases linearly from 2 to 0.) decreases linearly from 2 to 0.) |

Table 5 shows the feature classification of all comparative algorithms involved in this study. It can be observed that the vast majority belong to swarm-based algorithms, which are also commonly used in practical applications.

Table 5.

Feature classification of all algorithms.

| Features | Name |

|---|---|

| Evolution-based | DE, GA |

| Swarm-based | BAS, CSA, DA, GOA, GWO, IGWO, MFO, PSO, WOA, BAGWO |

| Physics-based | SA |

| Others | MVO, SCA |

BAGWO optimization performance evaluation and comparison

In this subsection, the optimization performance of the proposed BAGWO is evaluated using the CEC benchmark functions, and the test results are compared with 14 other commonly used optimization algorithms to comprehensively assess the optimization performance of the BAGWO. In the process of evaluation and analysis, statistical analysis methods are used to quantitatively analyze and evaluate the results.

Comparison of calculation results between BAGWO and other algorithms

Among the 24 benchmark functions selected in this paper, the input dimensions of the five benchmark functions F8–F12 are fixed, while the input dimensions of the 19 benchmark functions F1–F7 and F13–F24 are variable. The size of the input dimension represents the number of decision variables. In the comparative analysis of the test results in this section, the dimension of the benchmark functions with variable input dimension is set to 30, which is also the number of dimensions often selected in many similar works. In Table 3, detailed information on all benchmark functions was provided, where F1–F4 are unimodal, F5–F16 are multimodal, F17–F20 are hybrid, and F21–F24 are compositional functions, and Table 4 contains the parameter settings for all comparison algorithms participating in the study. In order to minimize the impact of random factors in each optimization process, each benchmark function is repeated 30 times when evaluating the optimization performance of the algorithm. and the average value and standard deviation of the calculated data are used to objectively represent the optimization result of the optimization algorithm on a specific benchmark function. The optimization problems addressed in this paper aim to minimize the value. Therefore, the lower the average value, the better the optimization performance of the algorithm, and the smaller the standard deviation, the greater the numerical stability of the optimization algorithm. The use of average value and standard deviation can reduce the influence of random factors on the calculation results to a certain extent. However, it should be noted that the larger outliers of the calculation results may deteriorate the average value and standard deviation. The boxplot can display the median, quartiles, and outliers in the data. Therefore, the box plot can be used as a valuable tool for comprehensively and intuitively analyzing and comparing the calculated data. However, in order to objectively and quantitatively analyze and evaluate the performance of the algorithms, statistical analysis methods will be mentioned and utilized later.

Table 3.

The benchmark functions in this paper.

| Functions | Source | Dim | Range |

|

Function type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | CEC 2005 F1 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

0 | unimodal |

| F2 | CEC 2005 F3 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

0 | unimodal |

| F3 | CEC 2005 F6 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

0 | unimodal |

| F4 | CEC 2017 F1 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

100 | unimodal |

| F5 | CEC 2005 F8 | 10/30/50/100 | [−500, 500

|

−418.98

|

multimodal |

| F6 | CEC 2005 F10 | 10/30/50/100 | [−32, 32

|

0 | multimodal |

| F7 | CEC 2005 F12 | 10/30/50/100 | [−50, 50

|

0 | multimodal |

| F8 | CEC 2005 F14 | 2 | [−65.536, 65.536] | ≈ 0.998 | multimodal |

| F9 | CEC 2005 F16 | 2 | [−5, 5

|

≈ −1.0316 | multimodal |

| F10 | CEC 2005 F19 | 3 | [0, 1

|

≈ −3.86 | multimodal |

| F11 | CEC 2005 F21 | 4 | [0, 10

|

≈ −10.1532 | multimodal |

| F12 | CEC 2005 F23 | 4 | [0, 10

|

≈ −10.5364 | multimodal |

| F13 | CEC 2017 F4 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

400 | multimodal |

| F14 | CEC 2017 F6 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

600 | multimodal |

| F15 | CEC 2017 F8 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

800 | multimodal |

| F16 | CEC 2017 F11 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

1100 | multimodal |

| F17 | CEC 2017 F13 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

1300 | hybrid |

| F18 | CEC 2017 F15 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

1500 | hybrid |

| F19 | CEC 2017 F17 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

1700 | hybrid |

| F20 | CEC 2017 F19 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

1900 | hybrid |

| F21 | CEC 2017 F21 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

2200 | compositional |

| F22 | CEC 2017 F25 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

2500 | compositional |

| F23 | CEC 2017 F27 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

2700 | compositional |

| F24 | CEC 2017 F29 | 10/30/50/100 | [−100, 100

|

2900 | compositional |

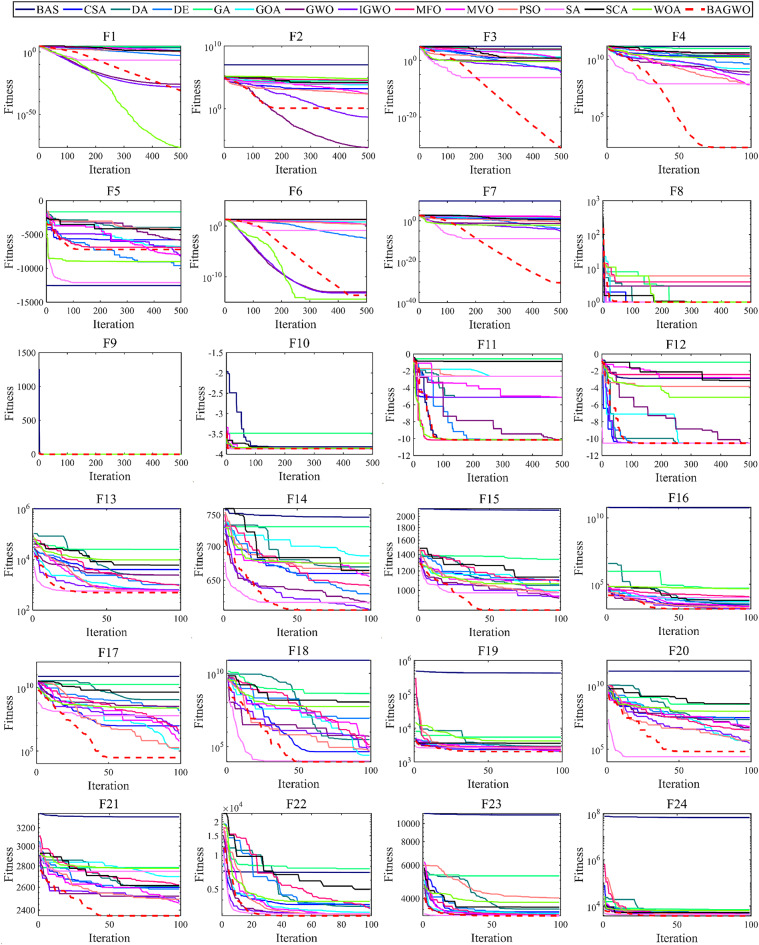

As depicted in Fig. 6, the comparison diagram illustrates the optimal fitness calculation process of 15 optimization algorithms, including BAGWO, for 24 benchmark functions. The calculation results of BAGWO are represented by red dotted lines in the figure. From the qualitative analysis of the comparison curve data in the graph, it can be seen that BAGWO has the best comprehensive optimization performance, especially in the 8 benchmark functions of F3, F4, F7, F8, F15, F17, F19 and F21. The optimization results are significantly better than those of other optimization algorithms. In addition, the optimization effect is in a dominant position in the 11 benchmark functions of F9, F10, F11, F12, F13, F14, F16, F20, F22, F23 and F24. Moreover, the optimization effect is also significant in other benchmark functions not explicitly mentioned. In Fig. 6, it can also be observed that BAGWO demonstrates superior convergence compared to the other 14 algorithms. It can rapidly approach the global optimal value area within a small number of iterations, thus validating the effectiveness of the “exploration and development” strategy proposed in this paper. In addition, it can be observed that the comprehensive optimization effect of BAGWO is superior to that of GWO, BAS and IGWO, further confirming the effectiveness and outstanding performance of BAGWO.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the optimization performance of the BAGWO with 14 other algorithms across 24 benchmark functions when the function dimension is 30 (F8–F12 input dimensions fixed).

Figure 7 shows the boxplot of the optimization results of the algorithms participating in the comparison across 24 benchmark functions. The reason for using boxplot is that they can intuitively present the data distribution of multiple optimization results from different algorithms across various benchmark functions, as well as key statistical information such as the median and interquartile range. In the same boxplot, the central red horizontal line indicates the median of the optimization results; the lower its position, the better the average optimization performance of the algorithm. The length of the box in the vertical direction reflects the degree of dispersion of the optimization results: a longer box signifies poorer stability of the optimization results, which corresponds to worse performance of the respective algorithm on the current benchmark function. In simple terms, algorithms with a lower red line position and shorter boxes in the boxplot demonstrate better performance on the current benchmark function, providing a visual and qualitative assessment of the comprehensive optimization performance of the algorithms. In qualitative analysis, it can be observed from the boxplot that the optimization results of BAGWO are concentrated. The median and average values are low in the figure, indicating superiority over other algorithms in the calculation results of most benchmark functions. In Table A.1 and Table A.3 of Supplementary Material, the average value and standard deviation of the calculation results for 15 algorithms across 24 benchmark functions are presented, using the same data source as Fig. 7, it is evident that the optimization results of BAGWO are significantly superior in most benchmark functions. Based on the data in Figs. 6 and 7, the data in the Supplementary Material, and the corresponding qualitative analysis conclusions, it can be seen that the optimization performance of BAGWO is superior to that of the other 14 algorithms included in the comparison. BAGWO demonstrates better accuracy, stability, and convergence speed in solving the optimization problem. However, to ensure the validity of this conclusion, the next section will further quantitatively analyze the calculation results across various dimensions.

Fig. 7.

Box plot analysis for benchmark functions F1–F24.

Convergence behavior analysis

Improvement strategies for the BAGWO are discussed in Sect. 3 of this paper, including the improvement of the charisma, the improvement of the switching strategy for ALDR, the improvement of the frequency of local exploitation, and the improvement of the initial distribution of the swarm. The conclusions of the qualitative analysis in the previous subsection validate the effectiveness of the improvement. This subsection will analyze how the improvement works. A total of 14 benchmark functions are selected here, namely F1–F9, F14–F16, F22, F23. Figures 8 and 9 depict the trends of various parameters as the number of iterations increases during the optimization process of BAGWO in these benchmark functions. The meanings of the subgraphs represented in the figures, in order of columns from left to right, are as follows: the subgraph of the benchmark functions dimension is 2D, the contour subgraph shows the historical optimization process of the swarm in the two-dimensional space, the historical trajectory subgraph of the one-dimensional optimization variable, the convergence process subgraph of the best fitness, and the convergence process subgraph of the average fitness of the swarm. From the one-dimensional history trajectory graph in the third column and the swarm search history graph in the second column in Figs. 8 and 9, it can be seen that the search agents in the swarm change their positions drastically when the number of iterations is small. During this drastic change of position, the swarm mainly focuses on exploration, which corresponds to the left tail of the function curve of the sigmoid function of the charisma. At this time, the charisma value is small, and the frequency of local exploitation is also large. Therefore, the probability of the swarm moving in the region near the optimal solution is high. As the number of iterations increases, the rate of change in position rapidly levels off, at this time the charisma value gradually increases, the swarm is more and more focused on exploitation, and it gradually tends to exploit the region near the global optimum until the global optimal solution is found. From the above analysis, it can be seen that the BAGWO enables the swarm to quickly locate the region where the optimal solution is found in the exploration-oriented process. The swarm then exploits this region in detail during the exploitation-oriented process, achieving a balanced exploration and exploitation in BAGWO. This balance enhances accuracy, stability, and convergence speed.

Fig. 8.

Search history and trajectory of the first particle in the first dimension (F1–F3, F5–F9).

Fig. 9.

Search history and trajectory of the first particle in the first dimension (F4, F14–F16, F22, F23).