Abstract

Stress response in bacterial pathogens promotes adaptation, virulence and antibiotic resistance. In this study, a network approach is applied to identify the common central mediators of stress response in five emerging opportunistic pathogens; Enterococcus faecium Aus0004, Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus USA300, Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78,578, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. A Protein-protein interaction network (PPIN) was constructed for each stressor using Cytoscape3.7.1 from the differentially expressed genes obtained from Gene expression omnibus datasets. A merged PPIN was constructed for each bacterium. Hub-bottlenecks in each network were the central stress response proteins and common pathways enriched in stress response were identified using KOBAS3.0. 31 hub-bottlenecks were common to each individual stress response, merged networks in all five pathogens and an independent cross stress (CS) response dataset of Escherichia coli. The 31 central nodes are in the RpoS mediated general stress regulon and also regulated by other stress response systems. Analysis of the 20 common metabolic pathways modulating stress response in all five bacteria showed that carbon metabolism pathway had the highest crosstalk with other pathways like amino acid biosynthesis and purine metabolism pathways. The central proteins identified can serve as targets for novel wide-spectrum antibiotics to overcome multidrug resistance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-91269-5.

Keywords: Stress response, Bacterial pathogen, Differentially expressed genes, Protein protein interaction network, Centrality

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Systems biology

Introduction

Bacteria have developed sophisticated mechanisms to survive in extreme environmental conditions through years of evolution1. The ability to screen the environment for physical and chemical disturbances is integral for bacteria to stay in a dynamic environment2. Survival of the fittest is achieved as a result of enormous genetic elasticity in the bacteria. The capacity to deal with stressors is the determining factor for their survival. Bacteria fight against stress by adopting many mechanisms including proteolysis, formation of dormant structures such as spores, modification of molecules entering the bacteria, decreased antibiotic penetration or efflux, changes in the target site, changes in the composition of the stressor and modifications in metabolic pathways3.

Studies on the stress response have determined that different environmental conditions affect cell cycle, movement of signalling molecules, metabolism, the level of gene expression and protein activity in bacteria4. Sigma factor, the factor that bind to the RNA polymerase at transcription initiation site is the primary regulator for general stress response in many bacterial species5. Different sigma factors perform various tasks such as heat shock, motility of flagella, maintaining the stationary phase, cell envelop formation, sporulation etc6. Bacteria are simultaneously exposed to various stressors, such as changes in temperature, pH, availability of nutrients, and exposure to toxins7. Harmless bacteria are able to survive in the environment due to the alterations in gene expression caused by stress but pathogenic bacteria use this as an advantage to escape from the immune system and antibiotics6.The stress response mechanisms in bacteria are associated with increased virulence in bacteria, bacterial adaptation, physiological alterations, multidrug resistance, biofilm formation, quorum sensing, and antibiotic resistance1,8.

A unified control of the stress response is suggested by cross-stress (CS) protection, the capacity of one stress situation to protect against other stressors9. As an example, keeping Escherichia coli in a medium containing acid provides protection against cold, antibiotics, heat and chemicals. In comparison, the cells that were not exposed to acid first were not resistant to other stresses10. CS protection has also been reported in fungus Metarhizium robertsii where treatment with heat shock induced protection against UV, osmotic and oxidative stress11. CS protection against environmental stress and antibiotics promote bacterial resistance to therapeutic agents7,12,13. In this way, CS protection has also resulted in increased virulence in bacteria. CS protection has also posed a threat to food safety. Exposure to acidic conditions could induce cross-protection for foodborne pathogens against subsequent stress or multiple stresses such as heat, cold, osmosis, antibiotic, disinfectant, and non-thermal technology14. When a cell is adapted to a specific condition and suddenly in it subjected to another condition there is a change in gene expression.

Large omics datasets can be analysed through machine learning, statistical analysis, pathway analysis, network studies, visualization methods such as scatter plots etc15. Networks are of different types, such as protein-protein interaction (PPI), isoform-isoform interactions, genetic interactions, neuron-neuron interactions, metabolic molecule interactions, and drug-target interactions16. Bacteria have numerous genes and interconnected pathways that benefit from a system level approach for their integrative analysis using network biology17. Network studies are highly effective in studying the biological processes and pathways as well as key genes and proteins, including drug targets18. As an example, Protein-Protein Interaction network (PPIN) analysis elucidates the association of one disease with another19,20. Another study showing PPI analysis of human proteins and virus proteins was used to study the properties of human proteins targeted by viruses21. Analysis of host-pathogen PPIs was carried for prediction of cardiovascular diseases induced by microbes22. Network studies in association with machine learning was done to predict the drug targets in microbe associated cardiovascular diseases23.

Genes involved in all the stress responses are likely to be differentially expressed under multiple conditions and in multiple pathogens. Genes with a prominent role in stress response are also likely to assume a central role in the PPIN of DEGs. Bacterial stress response has been modelled in E. coli using the DEGs in stress conditions such as pH, temperature and antibiotics. As a result, the role of 24 central proteins pathways such as ribosome, purine metabolism and ABC transporters in stress response was identified24. In the present study, we hypothesized the presence of a set of central stress response genes and pathways that would be common to and necessarily required for response to all stressors as well as CS response in multiple pathogenic bacteria. The bacteria used in this study are Enterococcus faecium Aus0004, Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus USA300, Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78,578, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. These opportunistic and antibiotic resistant bacteria are responsible for a majority of hospital-acquired infections cause infections in the nose, skin, lungs, urinary tract, and in different regions undergoing surgery in hospitalized patients25. The different types of stressors considered are antibiotics, drugs, chemicals, prebiotics, nutrients starvation etc. The DEGs in specific stress conditions were extracted from Microarray and RNA Seq datasets. PPINs were generated from the five bacteria in different stress conditions. Thirty-one central proteins were found to be common to all the stressors in each pathogen while 20 common pathways were identified to have a role in stress response in the bacteria studied. Cross-validation with an independent CS response dataset of Escherichia coli showed that the central stress responses genes coincided with central genes of the CS-PPIN. Our work indicates the existence of some common genes and pathways that are responsible for stress response. Identification of the central proteins and pathways involved in stress response in bacteria can be helpful for determining broad-spectrum antibiotic therapies in future.

Materials and methods

Identification of datasets from gene expression omnibus

The expression data was extracted from GEO, an international public repository which contain high-throughput gene expression and other functional genomics data26. The GEO datasets was searched for emerging pathogenic bacteria. Specific strains were taken to avoid strain wise variations. The strains with the maximum number of available datasets of stress were selected. Studies with knockouts or other genetic manipulation were excluded. The GEO datasets used are shown in Table 127–36. The information about stressors considered is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Details of datasets selected to find stress response DEGs in five pathogenic bacteria.

| No. | Microorganism | Technique | Stress condition | Accession no. | References | No. of DEGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Enterococcus faecium Aus0004 | RNA Seq | Daptomycin | GSE94924 | 27 | 752 |

| 2. | Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus USA300 | RNA Seq | Nitric oxide | GSE99563 | 28 | 514 |

| Array | Benzbromarone | GSE55980 | 29 | 771 | ||

| Array | Thioridazine | GSE43759 | 30 | 396 | ||

| 3. | Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78,578 | RNA Seq | NMP 1-(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine | GSE122651 | 31 | 1431 |

| 4. | Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | RNA Seq | Tanreqing | GSE141753 | 32 | 707 |

| RNA Seq | Diallyl ether | GSE151292 | 33 | 559 | ||

| RNA Seq | Fructooligosaccharide | GSE124468 | 34 | 85 | ||

| 5. | Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | RNA Seq | Low iron | GSE213943 | 35 | 2030 |

| Array | Low zinc | GSE168513 | 36 | 725 |

Identification of DEGs

From the complete set of DEGs present in the datasets, genes showing significant change in gene expression having |Log2FC | ≥ 1 and Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) ≤ 0.05 were taken as seed nodes22,24. For the microarray datasets, DEGs were extracted through GEO2R26. For RNA Seq data, the DEGs were extracted by processing the FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped). Fold change (log2FC) calculations were done and p-value was calculated by applying the t-test. FDR was calculated by sorting p-values in ascending order, ranking them and applying the formula37:

|

where m is total number of hypotheses tested and i is rank of p-value.

The list of DEGs is given in Supplementary sheet S1.

PPIN generation

The individual PPIN in each stress condition was generated using STRING38. The confidence score for network construction was taken as 0.77524. The probability that a predicted link between two proteins in the same metabolic map in the KEGG database actually exists is represented by the confidence score. The PPIN of each bacterium in separate stress conditions was generated. The union of the different stressors of bacteria was generated using Cytoscape 3.7.139.

Validation and randomization of networks

To validate the network as biological network power law was fitted to the network and node degree distribution was plotted. The generated cross response network was also statistically validated using Simple randomization method preserving the degree option39 of the network Randomizer 1.1.3 plugin in Cytoscape 3.7.1.

Identification of hubs and bottlenecks

The topological analysis of the PPIN was done by using several topological measures namely degree, betweenness centrality (BC) and clustering coefficient. These can be explained as follows:

A degree of a node in the network is defined as number of edges linked to it which means the number of interactions The nodes with degree exponent < 2 were considered as Hub nodes as previously used for calculation of significant hub nodes22.

The BC is a measure that tells how frequently a node functions as a bridge over the shortest pathways connecting two other nodes22. A node with high BC has greater control over the network40. The top high BC nodes in this study were the same as the number of nodes identified as hubs for each network. The nodes that are both hubs as well as bottlenecks are called Hub-bottleneck nodes were considered central in the network.

The clustering coefficient is the measure used to infer the properties of the proteins in a cluster. It is the measure used in network analysis to define the level to which nodes tend to cluster together. The proteins in the similar clusters have similar properties. The value of clustering coefficient is between 0 and 1. The higher the value, higher the similarity/association between the proteins in the same cluster41.

Generation of CS-PPIN

In order to compare the central stress response proteins obtained from different pathogens with those under CS response, a PPIN of CS was generated. DEGs under two or more stress conditions were obtained from a dataset of CS protection study in which E. coli was grown for 500 generation under five different stressors (nutrient deprivation, 0.3 M NaCl, 0.6 n-butanol, 0.1 mMol H2O2, and pH 5.5)42. The DEGs with a cut-off score FDR < 0.05 were obtained and were used to construct a CS-PPIN. The hub-bottlenecks were computed.

Identification of stress response pathways

The pathways involved in stress response in five selected bacteria were identified using KOBAS 3.0, a webserver for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and gene ontologies. The enrichment module was used to find the pathways associated with the genes in stress response43.

Results

Topological analysis of the generated networks

To study the stress response, ten stress conditions were analysed in five bacteria. For this, ten individual networks were constructed and merged to obtain five final stress response PPINs for five selected bacteria. The number of seed nodes used to generate the stress response PPIN of each bacterium are shown in Table 1. The details of networks constructed using the DEGs extracted in STRING v11 are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

A single network was generated using seed nodes in Daptomycin stress E. faecium (referred to as EF-PPIN) while three individual networks were constructed for stress conditions corresponding to Nitric oxide, Benzbromarone and Thioridazine in S. aureus. The merged networks of these conditions are then formed in Cytoscape (termed the SA-PPIN). For K. pneumoniae a network was constructed using seed nodes in 1-(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine stress, represented as KP-PPIN. For P. aeruginosa three independent stress response networks were constructed for stressors Tanreqing, Diallyl ether and Fructooligosaccharide. They were then merged to form a network (PA-PPIN). In case of M. tuberculosis, two networks were generated in Low Fe and Low Zn and then merged to construct the MT-PPIN. So, the final merged networks are represented as EF-PPIN, SA-PPIN, KP-PPIN, PA-PPIN, MT-PPIN. The CS-PPIN of E. coli was also generated.

The topological characteristics of the five constructed networks are shown in Table 2. The values of correlation coefficient, coefficient of determination and degree exponent indicates the scale free nature of all the networks, which in turn means that most nodes have only a few connections, while a small number of nodes have a large number of connections. The scale free nature of the biological nature is important as it allows the efficient coordination among components of the biological systems. Similarly, the calculated average clustering coefficient of real networks are much greater than the random networks as shown in Table 2 and indicate the biological significance of the network22. In network analysis, the clustering coefficient is a metric that measures how closely connected nodes are in a graph (Chalancon, Kruse, and Babu 2013). For comparison, the average clustering coefficients of 1000 randomized networks have also been added. The average clustering coefficient value of all five networks was found to be in the range of 0.345–0.571, and is similar to that reported for other PPI networks44,45. The clustering coefficient of the PPI networks is also much higher in comparison with that of 0.027–0.161 in the random networks, further validating the node distribution and densely connected nature of the networks.

Table 2.

Topological characteristics of the PPINs.

| Network | Nodes | Edges | Highest Degree | Highest BC | Correlation | R 2 | Deg exp | Clustering coefficient of real networks | Clustering coefficient of randomized networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF-PPIN | 995 | 8129 | 83 | 1 | 0.665 | 0.758 | −1.142 | 0.459 | 0.096 |

| SA-PPIN | 2038 | 9125 | 105 | 1 | 0.748 | 0.838 | −1.500 | 0.411 | 0.043 |

| KP-PPIN | 1299 | 8466 | 95 | 0.666 | 0.665 | 0.808 | −1.296 | 0.481 | 0.064 |

| PA-PPIN | 2289 | 14,970 | 105 | 1 | 0.789 | 0.887 | −1.477 | 0.422 | 0.027 |

| MT-PPIN | 2875 | 16,787 | 209 | 1 | 0.829 | 0.907 | −1.428 | 0.345 | 0.034 |

| CS-PPIN | 715 | 9887 | 123 | 0.064 | 0.397 | 0.643 | −0.879 | 0.571 | 0.161 |

Constructing the networks of the hub-bottlenecks also showed that they form highly connected subnetworks. The connected components of the subnetworks are shown in Table 3. Constructing the networks of these hub-bottlenecks showed they form highly connected subnetworks. The connected components of the subnetworks are shown in Table 3. In all networks, the hub-bottlenecks were fully connected while in KP-PPIN, all are connected except 1. This indicates the completeness of the constructed networks. The five bacterial stress response networks are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Table 3.

The number of Hub-bottlenecks and the connected components of their subnetworks in each network.

| Microorganism | No of hubs | No. of bottlenecks | No. of hub bottleneck | Connected components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF-PPIN | 801 | 801 | 770 | All |

| SA-PPIN | 558 | 558 | 349 | All |

| KP-PPIN | 856 | 856 | 758 | 757 |

| PA-PPIN | 711 | 711 | 461 | All |

| MT-PPIN | 628 | 628 | 323 | All |

| CS-PPIN | 691 | 691 | 680 | All |

Central proteins in stress response

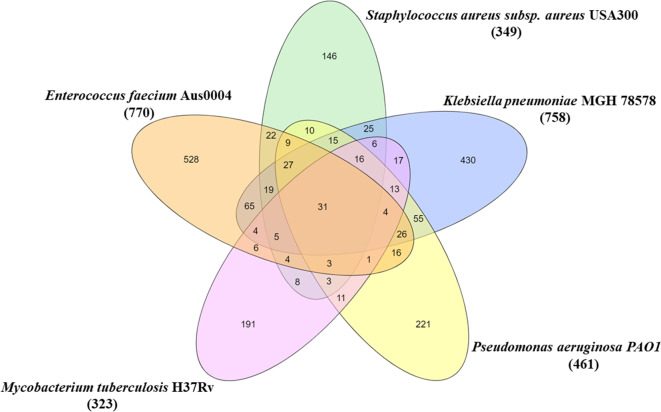

The number of Hubs, bottlenecks, and central proteins of the final generated networks were computed and are shown in Table 3. The overlapping of central proteins in the networks is shown in Fig. 1. Comparison of central proteins in all bacterial networks suggested the presence of thirty-one common proteins. These common central proteins across all the five bacterial stress response networks are listed in Table 4. These proteins have a reported role in DNA repair pathways, synthesis of some important biomolecules, activation of some other proteins in stress and performing cellular tasks, energy metabolism, and efficient signalling molecule production as shown in Table 4. The presence of these 31 central proteins was also checked in 10 individual stress response networks. It was observed that all of the 31 common proteins identified were also central in most of the individual stress response networks. As shown in Supplementary Table S3, a majority of the 31 proteins were central to the individual stress response networks, with the lowest number being found in lowest zinc conditions in M. tuberculosis. Additionally, Table S4 gives statistical information such as degree, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality of the 31 common central proteins in each of the five networks. This gives an overall importance of these central proteins in driving stress response in each of the individual bacterial network.

Fig. 1.

Overlapping central proteins modulating stress response in five pathogenic bacteria: The orange ellipse represents central proteins in EF-PPIN, green ellipse represents central proteins in SA-PPIN, blue ellipse represents central proteins in KP-PPIN, yellow ellipse represents central proteins in PA-PPIN, pink ellipse represents central proteins in MT-PPIN.

Table 4.

Role of the common central proteins in normal and stress condition in cells.

| Gene name | Protein name | Role of protein in cell | Role of protein in stress | Regulon info |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| adk | Adenylate kinase | Cellular homeostasis. Energy metabolism46. ADP synthesis90. | Energy metabolism. Nucleotide synthesis46. | F, ns |

| atpD | ATP synthase subunit beta |

ATP synthesis. Metabolic pathways of proteins and carbohydrates47. |

Increases antibiotic susceptibility of pathogens91. | TU, ns |

| eno | Enolase | Glycolytic enzyme, role in catabolic glycolytic pathway57. | Oxidative stress response in P. aeruginosa92 . | TU, linear |

| gyrB | DNA gyrase subunit B | DNA replication, DNA binding, ATP hydrolysis65. | Develop resistance against fluoroquinolones66. | F, ns |

| pgk | Phosphoglycerate kinase | ATP production70. | Increase glycolytic flux in hypoxia. Triggers pathways involved in DNA repair and SOS response70. | F, linear |

| carB | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase | Pyrimidine biosynthesis50. | Absence of this gene in S. aureus led to significant growth defect and increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide51. | TU, Ns |

| cmk | CMP kinase | Nucleotide biosynthesis52. | DNA repair52. | Ns |

| folD | Bifunctional protein FolD, Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase | Folate cycle, synthesis of methionine, purine and thymidylate58. | Help bacteria in heat-stress response59. | F, Ns |

| guaA | GMP synthetase | Biosynthesise guanine nucleotides62. | Purine metabolism. Helps bacteria in low guanine63. | TU, In |

| purB | Adenylosuccinate lyase | Purine metabolism71. | Antibiotic and stress tolerance71. | TU, ns |

| purE | N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide mutase | Biosynthesis of purine nucleotides72. | Biosynthesis of purine nucleotides73. | F, ns |

| purH | Bifunctional purine biosynthesis protein | Purine biosynthesis74. | Purine biosynthesis74. | F, ns |

| ftsZ | Cell division protein FtsZ | Plays major role in cytokinesis48. |

Interact with transcription factors. Relocates its Z -ring to other parts of the cell which help other proteins in stress response pathways49. |

TU, ns |

| cysE | Serine acetyltransferase | Cysteine and serine metabolism53. | Cysteine metabolism is linked with antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation in some bacteria53. | F, ns |

| dnaK | Chaperone protein, Heat shock protein 70 | Required for growth in absence of stress54. | Maintain homeostasis in thermal stress55. | F, linear |

| dnaN | DNA polymerase III beta sliding clamp subunit | DNA replication, maintenance of membrane structure56. | SOS response and DNA repair56. | TU, ns |

| glmS | Glutamine–fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | Protein glycosylation Growth and functional maintenance of the cell60. | Help in Cadmium, osmotic and pH stress61. | TU, ns |

| gyrA | DNA gyrase subunit A | Replication64. | Play an active role in quinolone treatment64. | F, ns |

| lepA | Elongation factor 4 | Biogenesis of ribosome 30s subunit. Protein export functions67. | Released in the cytoplasm of high ionic strength or low temperature68. | F, ns |

| pgi | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | glycolysis and gluconeogenesis69. | Activated in oxidative, heat and nutrient stress69. | F, ns |

| pyrG | CTP synthase | Pyrimidine biosynthesis75. | Pyrimidine biosynthesis75. | F, linear |

| recA | Recombinase A | DNA repair76. |

DNA repair pathways76. Swarming motility77. |

F, ns |

| rplB | 50 S ribosomal protein L2 |

Transcription. Formation of peptide bond78. |

Helps in high hydrostatic pressure78. | TU, in |

| rplC | 50 S ribosomal protein L3 |

Role in ribosome assembly. Transcription regulation79. |

Resistance tolinezolid (an oxazolidinone) and tiamulin (a pleuromutilin)80. | F, ns |

| rpoA | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha | Transcription81. | Regulation of Transcription in stress81. Inhibition of RpoS by oligomerization93. | TU, ns |

| rpoB | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | RNA synthesis, Binding of sigma factor. Serve as a binding site for a antibiotics82. | Interacts with heat shock proteins to maintain the stability of RNA polymerase83. Inhibition of RpoS by oligomerization93. | TU, ns |

| rpoC | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta’ | Synthesis of RNA. Catalytic Mg2 + coordination82. |

Plays role in efficient transcription in stress response. Binding site for ppGpp which is a global gene regulator in stress. Sigma factor binding82. |

TU, ns |

| rpsA | 30 S ribosomal protein S1 | Transcription and Translation processes84. | Downregulated in oxidative stress84. RNA mediated stress response85. Inhibition of RpoS by oligomerization93. | F, ns |

| rpsB | 30 S ribosomal protein S2 | Binding proteins to ribosome86. | Upregulation on exposure to silver nanoparticle. Ribosomal protein S2 regulates its own level by inhibition of messenger (m)RNA synthesis during stress conditions86. | F, ns |

| rpsE | 30 S ribosomal protein S5 |

Translocation and translocation. mRNA binding87. |

Low expression level in salt stress87. | TU, ns |

| thyA | Thymidylate synthase | Required for DNA synthesis94. | DNA replication and repair88.Decreased activity in oxidative and Nitrosative stress. Increased activity in acidic stress89,95. | TU, ns |

Cross-validation using CS-PPIN

It was found that 31 central proteins are common to the stress response networks of all the pathogens and stressors studied. These 31 nodes were then compared with a CS-PPIN from E. Coli constructed as described in methodology. Out of the 31 central proteins found to be central to stress response in our study, 29 were found to central proteins in CS-PPIN also. Also, 14 out of 20 enriched pathways (common among stress response networks) identified in our study were found to be enriched in CS-PPIN. The central stress response nodes in common with those of the CS-PPIN are shown as bold in Table 4.

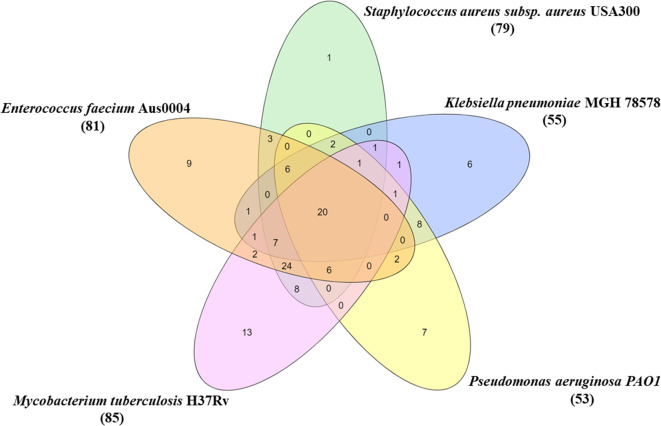

Pathways enriched in each bacterium for stress

The common pathways responsible for mediating the stress response in bacteria having p-value < 0.05 were identified. A Venn-diagram to represent overlapping pathways in the five bacteria is shown in Fig. 2. These common enriched pathways are listed in Table 5 which highlights their role in normal and stress conditions such as biofilm formation, signalling molecules formation, biosynthesis of amino acids, maintenance of redox balance, developing resistance against antibiotics etc. The percentage of proteins annotated by KOBAS 3.0 for the stress response network generation is shown in Supplementary Table S5. Twenty pathways were found to be common in all five bacteria. Additionally, Table S6 gives statistical significance in the form of p-value for the 20 common enriched pathways in each of the five networks. This information shows how enriched these common pathways are in each of the five bacterial stress response networks. A low p-value shows that each of the pathway in each network is highly enriched and is important for stress response mechanism.

Fig. 2.

Overlapping enriched pathways modulating stress response in five pathogenic bacteria: The orange ellipse represents the pathways enriched in EF-PPIN, green ellipse represents pathways enriched in SA-PPIN, blue ellipse represents pathways enriched in KP-PPIN, yellow ellipse represents pathways enriched in PA-PPIN, pink ellipse represents central proteins in MT-PPIN.

Table 5.

Common enriched pathways with their role in normal and stress conditions in bacteria.

| Pathways | Role in normal conditions | Role in stress |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic pathways | Energy generation, synthesis of biomolecules, cellular processes115. | ATP is the essential requirement in stress conditions115. |

| Carbon metabolism | Redistribute carbon groups to various amino acids to generate compounds which serve as the building blocks of the cell115. | Modification of enzymes in S. aureus in Cu stress by carbon metabolism116. |

| Biosynthesis of amino acids | Series of enzymatic reaction that converts precursor molecules into amino acids117. | Effect of cefotaxime stress in amino acid metabolism. Level of some amino acids increases in stress. Enhanced amino acid levels is indicator of stress response of S. pneumoniae to antibiotics117. |

| Purine metabolism | Energy transfer functions, cell signalling, production of GTP118. | Production of signalling molecules by purines have important role in formation of biofilm118. |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | Synthesis of various sugar derivatives and biomolecules. Synthesis of cell wall component and polysaccharides119. |

High mucin environment adaptation of Akkermansia muciniphila119. Acid stress in S. thermophilus120. |

| Ribosome | Translation process121. | Formation of leaderless mRNA, it selectively induces under stress121. |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | Synthesis and degradation of pyrimidine molecules which are involved in DNA, RNA synthesis122. |

Formation of biofilm. Formation of cell signalling molecules in stress123. |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | Source of biosynthetic intermediates for the synthesis of nucleotides, amino acids, vitamins, lipopolysaccharide and also fatty acids. maintain carbon homoeostasis124. | Cell stabilizes NADPH level in oxidative and ROS stress by mediating this pathway125. |

| Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | Energy production, amino acid biosynthesis, nitrogen metabolism126. | Ciprofloxacin shows large decrease in Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism127. |

| One carbon pool by folate | Synthesis of precursors for cellular functions, epigenetic maintenance128. | Mediate antibiotic stress, redox defense Biofilm formation129. |

| Cysteine and methionine metabolism | Sulphur metabolism130. | Play role in nutrient and oxidative stress reactive oxygen species stress131. |

| Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | Interconvert through various enzymatic reactions. Have role in protein synthesis132. | Oxidative, osmotic stress, resistance to Kanamycin133. |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | Glyoxylate shunt allows bacteria to grow on acetate or fatty acids in Krebs cycle134. | Specific enzymes for this pathway have been shown to be upregulated in the stressed environment of biofilms135. |

| Pyruvate metabolism | Glycolysis, energy production, catabolism, anabolism136. | Fatty acid biosynthesis, and thereby affect membrane fluidity in acid stress137. |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | Generates ATP through electron transport chain and ATP synthase138. | Aerobic electron transfer chain components downregulated in stress138. |

| Arginine biosynthesis |

Involved in urea cycle. Immune cell functions by NO production139. |

Acid, oxidative and phosphate deprivation stress140. |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | energy production, carbon skeleton generation for biosynthesis, redox balance141. | TCA maintains the disrupted redox balance in stress142. |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | Utilization and breakdown of carbohydrates as energy sources143. | Osmotic and nutrient deprivation stress143. |

| Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism |

Glucose and lipid metabolism. Energy metabolism, DNA repair, epigenetic modification, inflammation, circadian rhythm144. |

Enable cell to survive in changes such as nutrient oxidative stress deficiency145. |

| 2-Oxocarboxylic acid metabolism | Metabolism of amino acids, carbohydrates, hydrocarbons and fats143. | Energy production and redox balance143. |

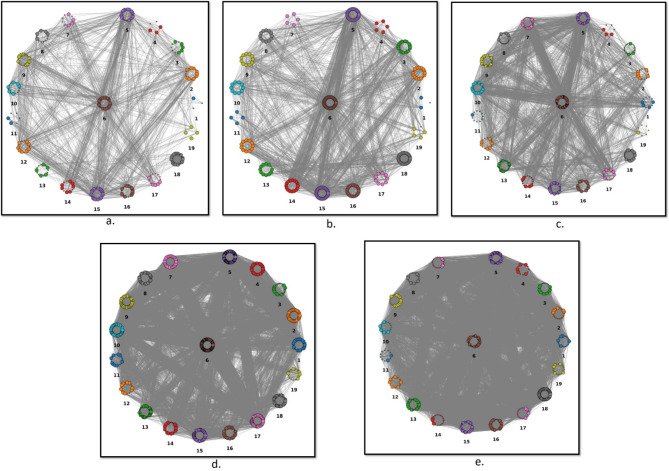

A cross-talk analysis was carried out between the 20 common enriched pathways in all the five bacterial networks (Fig. 3). As observed from the figure, there were a high number of edges between the top enriched pathways with “carbon metabolism pathway” as the most critical mediator of the pathway crosstalk making interactions with all other common enriched pathways in all five bacterial networks. The carbon metabolism pathway makes the largest number of interactions with the biosynthesis of amino acids pathway followed by purine metabolism pathways in case of all 5 bacterial networks. This confirms the importance of interplay among these pathways in bacterial stress response. Also, majority of nodes involved in cross-talk are the central nodes of the stress-response networks.

Fig. 3.

Involvement of the 31 central proteins identified in various stress response pathways.

Discussion

A network biology approach was used to find the stress response in some emerging pathogenic bacteria. The microbes used in our study are pathogens commonly causing infections in hospital and community settings. This includes E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa, and M. tuberculosis. A set of common proteins that have a central role in stress response in these five bacteria were determined. The previously reported roles of these proteins in physiological as well as stress conditions such as biofilm formation, developing resistance against antibiotics, SOS response generation, DNA repair, formation of other important biomolecules are shown in Table 446–95. Analysis using the Gene Ontology (GO) resource (https://geneontology.org/) showed that most of the central proteins identified were highly enriched in Transcription by Polymerase I-V and AMP biosynthetic processes. Other enriched processes were translesion synthesis, nucleoside monophosphate phosphorylation, DNA toplogical change, negative regulation of DNA transcription initiation, regulation of DNA transcripted transcription elongation, proton motive force-driven plasma membrane ATP synthesis, pyrimidine NTP biosynthesis, DNA templated transcription intiation, positive regulation of translation, glycolytic processes, cellular response to cell envelope stress, transcription anti-termination, and ribosomal small subunit assembly.

Central proteins of the stress response networks common to the stress response networks of all five pathogenic bacteria

Several different distinct stress response systems have been described in bacteria like the SOS, generalized stress, temperature, acid, starvation, oxidative, envelope and osmotic stress responses. The generalized stress response of bacteria is triggered by many different stress signals like is often accompanied by growth cessation or reduction. It confers the ability to withstand the actual stress response encountered as well as stressors not yet encountered. In contrast to the response to specific stressors, this provides a preventive mechanism that renders the cell stress resistant and is also termed as cross stress protection96. RpoS, the decisive master regulator of the generalized stress response, directs RNA polymerases to their promoters. RpoS controls over 1000 genes identified in E. coli by two separate studies97,98. All the central proteins identified in this study are part of the RpoS regulon either as the first gene or as a part of the transcriptional unit (TU) as shown in Table 4.

A further CHIP-Seq investigation showed that expression of the genes in the regulon may vary dramatically in response to RpoS. Thus, sensitive genes are transcribed rapidly with the [production of only a little RpoS, those whose expression changes linearly with increase in RpoS while the expression of insensitive genes change very little98. Only four of the central nodes identified were in the category of linear variation in concentration in response to RpoS levels, namely enolase, phosphoglycerate kinase, Heat shock protein 70 and CTP synthase. Many of the insensitive genes coincided with the glutamate-dependent acid resistance 2 system controlled by the GadEWX system that allows E. coli to survive at pH 2.0 and colonize the gastrointestinal tract99. Though part of the regulon, the expression pattern of the central genes identified in this study largely did not significantly change in response to RpoS concentration. Also, they were not target genes for GadEWX regulon. These genes may be under additional control of other stress response systems.

RecA, the main mediator of the DNA damage induced SOS response, is among the central proteins identified in this study. Apart from DNA damage, aging colonies, the SOS response is known to be activated by alkaline pH, cells reaching senescence in a medium, fluoroquinolone and β-lactam antibiotics. The RecA gene is important for controlling swarm motility, bacterial behaviour in biofilms and promotion of homologous recombination. It also upregulates integrase genes that in turn increase cassette rearrangement leading to spread of antibiotic resistance genes by horizontal gene transfer. RecA mediated SOS response is instrumental in promoting biofilm formation and development of persistence. Therefore, RecA has been proposed as a target for antibiotic resistance1.

The central proteins in our study also include dnaK, a key component of the heat shock stress response that is activated by the appearance of denatured or unfolded proteins in response to heat shock. DnaK is a chaperonin that has an additonal role in transport, transporting proteins for degradation, assembly of proteasome and temperature homeostasis. More recently, it has been shown to be involved in FliC mediated biofilm formation, cell adhesion to human plasminogen, bacterial growth, pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance. DnaK also has a role in immunogenicity and evasion of host immune response with potential for adjuvant and immunomodulatory activity54. The disruption of dnaK was shown to increase susceptibility of E. coli to fluroquinolones, methicillin and oxacillin100. The methylene tetrahydrofolate encoded by FolD is part of the folate biosynthetic pathway, a common target of antibiotics101 and also involved in heat stress response59.

The adk gene codes for the adenylate kinase enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of AMP and ATP to two ADP molecules in the de novo ribonucleotide synthesis pathway. The transcriptional repression of adk has been reported to cause accumulation of (p)ppGpp, a stress alarmone of the stringent stress response. (p)ppGpp binds to RNA polymerase to achieve global rewiring of protein expression in stress such as amino acid starvation. with a marked reduction in cell size, reduced growth rates and partial dormancy.

AtpD or the conserved beta subunit of the ATP synthase complex is an important catalytic component of the main energy transducing machinery102. Inhibitors that inhibit the ATP synthase complex have been studied in combination with various antibiotics to prolong their efficacy103. As an example, reservatrol that between the beta and gamma subunit of ATP synthase improves the effectiveness of aminoglycoside antibiotics in S. aureus91.

The adaptive oxidative stress response is activated in bacteria in response to high levels of reactive oxygen species that activates many efflux pump systems to achieve antibiotic resistance1. Eno encodes a glycolytic enzyme that is also part of the RNA degradosome. Mutations of eno were shown to affect virulence and oxidative stress in P. aeruginosa. GyrB subunit belongs to the DNA gyrase that introduces negative supercoil into DNA to relieve mechanical stress and is a target for quinolone antibiotics. The SOS DNA damage response and the oxidative stress response is likely to be activated by inhibition of DNA gyrase104.

The LPS induced envelope stress response of bacteria is responsible for membrane homeostasis, sensing of external signals and cell damage repair. It is also the target site of many antibiotics. Osmotic stress predominantly affects bacterial cell structure and permeability. The osmotic stress response works at both the protein and gene transcription level, and includes efflux pump systems, Two component membrane bound histidine kinase systems and membrane bound chemoreceptors1. CarB is a component of Carbamoyl phosphate synthase enzyme and is important for arginine and pyrimidine synthesis in E. coli105. In other pathogenic bacteria, it has been implicated in maintaining cell wall integrity, responding to osmotic stress, virulence, motility and biofilm formation106,107.

The ribosome acts as a main checkpoint for maintaining the balance between protein synthesis, sequestration, turnover and degradation during stress response. Ribosomal biogenesis may be reduced or ribosomes may be silenced in order to protect them under stress conditions108. RplA and rplB encode the protein L2 and L3 that are involved in the 50 S subunit of ribosomes. Both L2 and L3 are necessary for the functioning of the peptidyl transferase center109,110. L2 additionally functions as a transcriptional modulator78 while absence of methylation in L3 lead to a poor growth phenotype and cold sensitivity with accumulated ribosomal subunit precursors111. Both L2 and L3 are targets for antibiotics.

The cmk gene encodes a conserved cytidine monophosphate kinase that is essential for synthesis of nucleoside precursors. A Δcmk mutant in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis was growth deficient and highly attenuated while an antisense effect causes significant growth inhibition in S. aureus112. However, the exact mechanisms underlying these effects have not yet been elucidated.

GuaA codes for GMP synthetase, an enzyme that catalyzes the final step in the de novo synthesis of GMP. GTP has a key role in cellular processes and is an energy currency. The inverse relationship between (p)ppGpp has been proposed as a metabolic switch to control growth and survival113.

PurB, PurE and PurH are related to de novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis and are regulated by PurR, a general transcription factor. Downregulation of the PuR regulated genes has been observed in stress conditions and may be associated with repression of purine biosynthesis during starvation114.

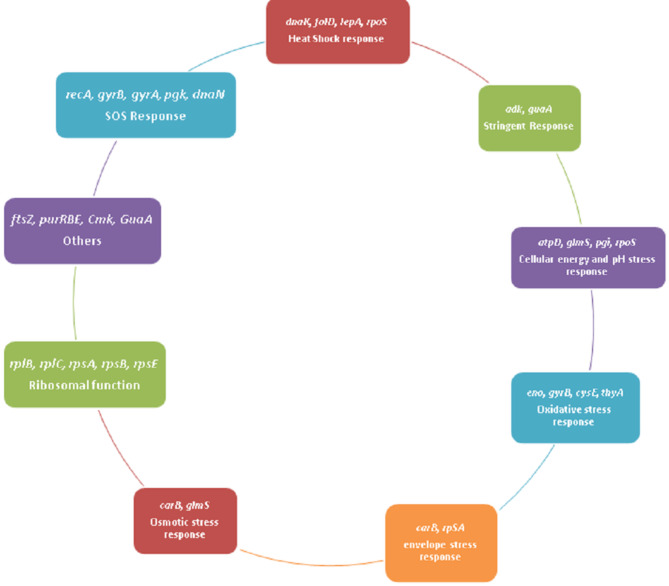

Systematic analysis of the 31 central proteins identified allowed us to categorize the involvement of these rpoS regulon proteins in various other types of stress responses as shown in Fig. 4. The stress response proteins found in our study were cross validated with the available dataset of CS response in E. coli and it was found that they coincide with each other. Twenty-nine proteins were found to have role in stress in this dataset also. The proteins are found to have role in transcription translational mechanisms, DNA repair pathways, cell division, energy metabolism, biosynthesis of important and amino acids.

Fig. 4.

Crosstalk between the common enriched pathways in the 5 bacterial stress response networks (a) SA-PPIN, (b) EF-PPIN, (c) MT-PPIN, (d) PA-PPIN and (e) KP-PPIN. The clusters represent the proteins in each numbered pathway, while edges show the interactions between the proteins in different pathways. The central nodes are depicted to be bigger than the other nodes. The pathway clusters are numbered in all the networks as follows: (1) 2-Oxocarboxylic acid metabolism; (2) Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism; (3) Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism; (4) Arginine Biosynthesis; (5) Biosynthesis of amino acids; (6) Carbon metabolism; (7) Citrate cycle (TCA cycle); (8) Cysteine and methionine metabolism; (9) Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism; (10) Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism; 11. Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism; 12. One carbon by folate; 13. Oxidative Phosphorylation; 14. Pentose phosphate pathway; 15. Purine metabolism; 16. Pyrimidine metabolism; 17. Pyruvate metabolism; 18. Ribosome; 19. Starch and sucrose metabolism.

Common pathways in stress response in five pathogenic bacteria

Pathway enrichment analysis of all the networks identified 20 pathways common to all the stress response proteins of all the bacteria. The role of these common pathways in normal as well as stress conditions such as biofilm formation, signalling molecules formation, biosynthesis of amino acids, maintenance of redox balance, developing resistance against antibiotics etc., is shown in Table 5115–146. Among these, some of the top enriched pathways are discussed below:

-

4.4.1

Carbon metabolism- When the cell is in stress condition, it leads to depletion of vital nutrients from the cell. But activation of carbon metabolism pathway is responsible for the synthesis of important macromolecules in the cell. It starts with the uptake of glucose by phosphotransferase system and then a series of interconnected pathways comes into action such as glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, tricarboxylic cycle etc. This pathway performs the effective utilization of sources of carbon to energy147.

-

4.4.2

Biosynthesis of amino acids- This pathway involves many interconnected pathways involved in the synthesis of the amino acids which is very important for the synthesis of proteins e.g. in Tryptophan biosynthesis pathway secondary metabolites are synthesised in the cell which are not involved in the normal growth of the cell but provide selective advantage to them to sustain in the environment148. They may be toxins which help in maintaining their chance of survival. Other pathways such as Aspartate pathway starts by an intermediate from the Citric acid cycle. During stress conditions some reactive oxygen species are produced which is metabolised by certain amino acids also some amino acids also help in cell wall synthesis149.

-

4.4.3

Purine and pyrimidine metabolism- The products of purine and pyrimidine metabolism are involved in processes like replication and transfer of signals in the cell. In stress conditions bacteria for its DNA repair acquire this pathway. Cell in stress sends signals for the production of toxins and other regulatory proteins150.

-

4.4.4

Oxidative phosphorylation- The process of oxidative phosphorylation is considered important process in organisms and it ensures the completion of all other vital processes in cell. The process of oxidative phosphorylation represents the formation of energy rich adenosine triphosphate. It involves energy generation by transfer of electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors in the presence of oxygen in electron transport chain. Oxidative phosphorylation is required in metabolism, growth, maintenance and active transport of electrons across cell membrane151.

-

4.4.5

Pentose phosphate pathways- Pentose phosphate pathway has two phases oxidative and non-oxidative phase. It involves formation of pentose sugars for nucleotide synthesis in non-oxidative phase and formation of reducing equivalents such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate in oxidative phase152.

Cross validation with CS response dataset of E. coli showed that many of the central responsible for mediating stress response in different stress conditions as well as responsible for CS protection. This indicates that there are certain common stress response proteins in a wide range of different bacteria. However, to advance these targets into effective therapeutic strategies, further analysis is needed to clarify their precise role in bacterial pathogenesis and survival. The carbon metabolism pathway was shown to have a high significance in cross-talk analysis in our study, underscoring its potential impact on bacterial survival. This pathway has been considered as a promising target for antimicrobials as its disruption induces nutritional starvation stress153.

Prioritized lists of drug targets have been generated for several diseases using high-quality interaction networks and analysis of differentially expressed genes154. The general and specific bacterial stress responses have been proposed as potential targets for overcoming bacterial resistance to antibiotics1,6. A recent study used network systems biology and transcriptomic analysis to identify critical stress-response genes in E. coli. The study revealed that bacterial responses to multiple stressors share overlapping genes and pathways, that regulate essential survival mechanisms like DNA repair and biofilm formation. By targeting these central nodes, researchers are developing adjuvant therapies that enhance antibiotic efficacy and reduce tolerance114. Stress adaptation systems like efflux pumps and biofilm formation contribute significantly to antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Thus, inhibiting these pathways and proteins could also lead to novel therapeutic strategies that work alongside antibiotics, effectively reducing resistance by compromising the bacteria’s adaptive capabilities1. The identification of shared proteins and pathways in the bacterial stress response system paves the way for the development of broad-spectrum antibiotics or adjuvants that combat multidrug resistance.

Conclusion

A network biology approach was used to analyze stress response in five emerging pathogenic bacteria: E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and M. tuberculosis, which commonly cause infections in healthcare and community settings. Thirty-one core proteins were identified as mediators of cellular stress (CS) across these bacteria, with roles in DNA repair, biomolecule synthesis, protein activation, cellular processes, energy metabolism, and signaling. Cross-referencing with E. coli CS data validated 29 of these proteins, emphasizing their roles in transcription, translation, DNA repair, cell division, and biosynthesis. These conserved proteins may provide potential catalytic sites for developing new antibiotics and treatments against these pathogens. Pathway enrichment identified 20 shared pathways, including metabolism, antibiotic biosynthesis, carbon metabolism, and ribosome function. Further, cross-talk analysis highlighted the “carbon metabolism pathway” as the most critical mediator of the pathway crosstalk making interactions with all other common enriched pathways in all five bacterial networks. This study is important for effective targeting of multiple resistance, persistence and virulence determining phenomena as an antimicrobial strategy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

AS acknowledges Netaji Subhas University of Technology for providing financial support in the form of Teaching Assistantship.

Abbreviations

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- PPIN

Protein-protein interaction network

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- CS

Cross- stress

- PPI

Protein-protein interactions

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped

- FC

Fold change

- BC

Betweenness centrality

- CS-PPIN

Cross-stress protein-protein interaction network

- EF-PPIN

Enterococcus faecium Aus0004-PPIN

- SA-PPIN

Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus USA300-PPIN

- KP-PPIN

Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78578-PPIN

- PA-PPIN

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1-PPIN

- MT-PPIN

Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv -PPIN

Author contributions

A.S. and S.T. wrote the main manuscript text, A.S. prepared the figures. S.B. designed the work and revised it critically. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from Department of Biotechnology grant number BT/PR40197/BTIS/137/68/2023.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary information files. Additionally, the raw network files are available at https://github.com/sblab/Stress-response/tree/main.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dawan, J. & Ahn, J. Bacterial stress responses as potential targets in overcoming antibiotic resistance. Microorganisms10 (7), (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Guo, M. S. & Gross, C. A. Stress-induced remodeling of the bacterial proteome. Curr. Biol.24 (10), R424–R434 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darby, E. M. et al. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance revisited. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.21 (5), 280–295 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harbottle, H. et al. Genetics of antimicrobial resistance. Anim. Biotechnol.17 (2), 111–124 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottesman, S. Trouble is coming: signaling pathways that regulate general stress responses in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem.294 (31), 11685–11700 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar, A. et al. Bacterial stress response: Understanding the molecular mechanics to identify possible therapeutic targets. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther.19 (2), 121–127 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang, F. C. et al. Bacterial stress responses during host infection. Cell. Host Microbe20 (2), 133–143 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonilla, C. Y. Generally stressed out bacteria: environmental stress response mechanisms in gram-positive bacteria. Integr. Comp. Biol.60 (1), 126–133 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swiecilo, A. Cross-stress resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast–new insight into an old phenomenon. Cell. Stress Chaperones21 (2), 187–200 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung, H. J., Bang, W. & Drake, M. A. Stress response of Escherichia coli. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf.5 (3), 52–64 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, X., St Leger, R. J. & Fang, W. Stress-induced pyruvate accumulation contributes to cross protection in a fungus. Environ. Microbiol.20 (3), 1158–1169 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gophna, U. & Ron, E. Z. Virulence and the heat shock response. Int. J. Med. Microbiol.292 (7–8), 453–461 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poole, K. Bacterial stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.67 (9), 2069–2089 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu, R. A. et al. Recent advances in Understanding the effect of acid-adaptation on the cross-protection to food-related stress of common foodborne pathogens. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.62 (26), 7336–7353 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parampreet Kaur, A. S. I. C. Computational techniques and tools for omics data analysis: State-of-the-art, challenges, and future directions. (2021).

- 16.Liu, C. et al. Computational network biology: data, models, and applications. Phys. Rep.846, 1–66 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhillon, B. K. et al. Systems biology approaches to understanding the human immune system. Front. Immunol.11, 1683 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlopoulos, G. A. et al. Visualizing genome and systems biology: technologies, tools, implementation techniques and trends, past, present and future. Gigascience4, 38 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramani, C. et al. Host-virus protein interaction network reveals the involvement of multiple host processes in the life cycle of hepatitis E virus. mSystems3 (1), (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Zhang, G. et al. Uncovering the genetic links of SARS-CoV-2 infections on heart failure co-morbidity by a systems biology approach. ESC Heart Fail.9 (5), 2937–2954 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khorsand, B., Savadi, A. & Naghibzadeh, M. Comprehensive host-pathogen protein-protein interaction network analysis. BMC Bioinform.21 (1), 400 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh, N. et al. Network analysis of host-pathogen protein interactions in microbe induced cardiovascular diseases. Silico Biol.14 (3–4), 115–133 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh, N. & Bhatnagar, S. Machine learning for prediction of drug targets in microbe associated cardiovascular diseases by incorporating host-pathogen interaction network parameters. Mol. Inf.41 (3), e2100115 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagar, S. D. et al. A network biology approach to decipher stress response in bacteria using Escherichia coli as a model. OMICS20 (5), 310–324 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Oliveira, D. M. P. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.33 (3), (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Clough, E. & Barrett, T. The gene expression omnibus database. Methods Mol. Biol.1418, 93–110 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinel, C. et al. Small RNAs in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium involved in daptomycin response and resistance. Sci. Rep.7 (1), 11067 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carvalho, S. M. et al. The Staphylococcus aureus alpha-acetolactate synthase ALS confers resistance to nitrosative stress. Front. Microbiol.8, 1273 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray, B. M. H.P., GSE55980. (2014).

- 30.Thorsing, M. et al. Thioridazine induces major changes in global gene expression and cell wall composition in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300. PLoS ONE8 (5), e64518 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anes, J. et al. Exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of the chemosensitizer 1-(1-Naphthylmethyl)-Piperazine creates membrane destabilization in multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol.10, 92 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, W. et al. Traditional Chinese medicine Tanreqing inhibits quorum sensing systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol.11, 517462 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, W. R. et al. Diallyl sulfide from Garlic suppresses quorum-sensing systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and enhances biosynthesis of three B vitamins through its thioether group. Microb. Biotechnol.14 (2), 677–691 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubio-Gomez, J. M. et al. Full transcriptomic response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to an inulin-derived fructooligosaccharide. Front. Microbiol.11, 202 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dow, A. et al. Zinc limitation triggers anticipatory adaptations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog.17 (5), e1009570 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alebouyeh, S. et al. Iron deprivation enhances transcriptional responses to in vitro growth arrest of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Microbiol.13, 956602 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoav, B. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. JR Stat. Soc. B57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res.49 (D1), D605–D612 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res.13 (11), 2498–2504 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen, S. J. et al. Construction and analysis of protein-protein interaction network of heroin use disorder. Sci. Rep.9 (1), 4980 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, J. et al. Recent advances in clustering methods for protein interaction networks. BMC Genom.11 (Suppl 3), S10 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dragosits, M. et al. Evolutionary potential, cross-stress behavior and the genetic basis of acquired stress resistance in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol.9, 643 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bu, D. et al. KOBAS-i: intelligent prioritization and exploratory visualization of biological functions for gene enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res.49 (W1), W317–W325 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dhasmana, A. et al. Topological and system-level protein interaction network (PIN) analyses to deduce molecular mechanism of curcumin. Sci. Rep.10 (1), 12045 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.M, B. and C. P, Comparative analysis of differential proteome-wide protein-protein interaction network of methanobrevibacter ruminantium M1. Biochem. Biophys. Rep.20, 100698. (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Ionescu, M. I. Adenylate kinase: A ubiquitous enzyme correlated with medical conditions. Protein J.38 (2), 120–133 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox, G. B. et al. Hypothesis. The mechanism of ATP synthase. Conformational change by rotation of the beta-subunit. Biochim. Biophys. Acta768 (3–4), 201–208 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chukwudi, C. U. & Good, L. Phenotypic indications of FtsZ Inhibition in hok/sok-induced bacterial growth changes and stress response. Microb. Pathog.114, 393–401 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramirez-Diaz, D. A. et al. FtsZ induces membrane deformations via torsional stress upon GTP hydrolysis. Nat. Commun.12 (1), 3310 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li, G. et al. Pyrimidine biosynthetic enzyme CAD: its function, regulation, and diagnostic potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22 (19), (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Buvelot, H. et al. Hydrogen peroxide affects growth of S. aureus through downregulation of genes involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis. Front. Immunol.12, 673985 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsao, N. et al. The contribution of CMP kinase to the efficiency of DNA repair. Cell Cycle14 (3), 354–363 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benoni, R. et al. Modulation of Escherichia coli serine acetyltransferase catalytic activity in the cysteine synthase complex. FEBS Lett.591 (9), 1212–1224 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fourie, K. R. & Wilson, H. L. Understanding GroEL and DnaK stress response proteins as antigens for bacterial diseases. Vaccines (Basel)8 (4), (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Schramm, F. D. et al. An essential regulatory function of the DnaK chaperone dictates the decision between proliferation and maintenance in Caulobacter crescentus. PLoS Genet.13 (12), e1007148 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aakre, C. D. et al. A bacterial toxin inhibits DNA replication elongation through a direct interaction with the beta sliding clamp. Mol. Cell52 (5), 617–628 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diaz-Ramos, A. et al. alpha-Enolase, a multifunctional protein: its role on pathophysiological situations. J. Biomed. Biotechnol.2012, p156795 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eich, M. L. et al. Expression and role of methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 like (MTHFD1L) in bladder cancer. Transl Oncol.12 (11), 1416–1424 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chello, P. L. et al. Elevation of dihydrofolate reductase, thymidylate synthetase, and thymidine kinase in cultured mammalian cells after exposure to folate antagonists. Cancer Res.36 (7 pt 1), 2442–2449 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Traykovska, M., Popova, K. B. & Penchovsky, R. Targeting GlmS ribozyme with chimeric antisense oligonucleotides for antibacterial drug development. ACS Synth. Biol.10 (11), 3167–3176 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCown, P. J., Winkler, W. C. & Breaker, R. R. Mechanism and distribution of GlmS ribozymes. Methods Mol. Biol.848, 113–129 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakamura, J. et al. The glutamine hydrolysis function of human GMP synthetase. Identification of an essential active site cysteine. J. Biol. Chem.270 (40), 23450–23455 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ipe, D. S. et al. Conserved bacterial de Novo guanine biosynthesis pathway enables microbial survival and colonization in the environmental niche of the urinary tract. ISME J.15 (7), 2158–2162 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sada, M. et al. Molecular evolution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa DNA gyrase GyrA gene. Microorganisms10 (8), (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Feng, X. et al. Mutations in GyrB play an important role in ciprofloxacin-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Drug Resist.12, 261–272 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kampranis, S. C. & Maxwell, A. Hydrolysis of ATP at only one GyrB subunit is sufficient to promote supercoiling by DNA gyrase. J. Biol. Chem.273 (41), 26305–26309 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heller, J. L. E., Kamalampeta, R. & Wieden, H. J. Taking a step back from back-translocation: an integrative view of LepA/EF4’s cellular function. Mol. Cell. Biol.37 (12), (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Pech, M. et al. Elongation factor 4 (EF4/LepA) accelerates protein synthesis at increased Mg2 + concentrations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.108 (8), 3199–3203 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu, J. et al. Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase is associated with disease activity and declines in response to infliximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Chin. Med. J. (England)133 (8), 886–891 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rojas-Pirela, M. et al. Phosphoglycerate kinase: structural aspects and functions, with special emphasis on the enzyme from Kinetoplastea. Open Biol.10 (11), 200302 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yee, R. et al. Genetic screen reveals the role of purine metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus persistence to rifampicin. Antibiotics (Basel)4 (4), 627–642 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoskins, A. A. et al. N5-CAIR mutase: role of a CO2 binding site and substrate movement in catalysis. Biochemistry46 (10), 2842–2855 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brugarolas, P. et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase and N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide mutase from Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.67 (Pt 8), 707–715 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jenkins, A. et al. Role of purine biosynthesis in Bacillus anthracis pathogenesis and virulence. Infect. Immun.79 (1), 153–166 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang, Y. F. & Carman, G. M. CTP synthetase and its role in phospholipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prog Lipid Res.47 (5), 333–339 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cox, M. M. Regulation of bacterial RecA protein function. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol.42 (1), 41–63 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gomez-Gomez, J. M. et al. A novel role for RecA under non-stress: promotion of swarming motility in Escherichia coli K-12. BMC Biol.5, 14 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rippa, V. et al. The ribosomal protein L2 interacts with the RNA polymerase alpha subunit and acts as a transcription modulator in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol.192 (7), 1882–1889 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klitgaard, R. N. et al. Mutations in the bacterial ribosomal protein l3 and their association with antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.59 (6), 3518–3528 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miller, K. et al. Linezolid and tiamulin cross-resistance in Staphylococcus aureus mediated by point mutations in the peptidyl transferase center. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.52 (5), 1737–1742 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abushahba, M. F., Mohammad, H. & Seleem, M. N. Targeting multidrug-resistant Staphylococci with an anti-rpoA peptide nucleic acid conjugated to the HIV-1 TAT cell penetrating peptide. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids5 (7), e339 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bergval, I. L. et al. Specific mutations in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis RpoB gene are associated with increased dnaE2 expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett.275 (2), 338–343 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Adekambi, T., Drancourt, M. & Raoult, D. The RpoB gene as a tool for clinical microbiologists. Trends Microbiol.17 (1), 37–45 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Teixeira-Gomes, A. P., Cloeckaert, A. & Zygmunt, M. S. Characterization of heat, oxidative, and acid stress responses in Brucella melitensis. Infect. Immun.68 (5), 2954–2961 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mélodie Duval, K. P. et al. View ORCID ProfileLauriane Kuhn, Mathias Springer, Pascale Romby, Ben F. Luisi, Eric Massé, View ORCID ProfileStefano Marzi, Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S1 enhances the kinetics of ribosome biogenesis and RNA decay.

- 86.Soni, D. et al. Stress response of pseudomonas species to silver nanoparticles at the molecular level. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.33 (9), 2126–2132 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang, Z. et al. Structural insights into the assembly of the 30S ribosomal subunit in vivo: functional role of S5 and location of the 17S rRNA precursor sequence. Protein Cell5 (5), 394–407 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chu, E. & Allegra, C. J. The role of thymidylate synthase as an RNA binding protein. Bioessays18 (3), 191–198 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fivian-Hughes, A. S., Houghton, J. & Davis, E. O. Mycobacterium tuberculosis thymidylate synthase gene ThyX is essential and potentially bifunctional, while ThyA deletion confers resistance to p-aminosalicylic acid. Microbiology (Reading)158 (Pt 2), 308–318 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Esmon, B. E. et al. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli mutants defective in adenylate kinase and sn-glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase. J. Bacteriol.141 (1), 405–408 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu, L. et al. Inhibition of the ATP synthase sensitizes Staphylococcus aureus towards human antimicrobial peptides. Sci. Rep.10 (1), 11391 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weng, Y. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa enolase influences bacterial tolerance to oxidative stresses and virulence. Front. Microbiol.7, 1999 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Morichaud, Z. et al. Structural basis of the mycobacterial stress-response RNA polymerase auto-inhibition via oligomerization. Nat. Commun.14 (1), 484 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu, J. et al. Thymidylate synthase as a translational regulator of cellular gene expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1587 (2–3), 174–182 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chatterjee, I. et al. In vivo mutations of thymidylate synthase (encoded by thyA) are responsible for thymidine dependency in clinical small-colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol.190 (3), 834–842 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hengge-Aronis, R. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the sigma(S) (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.66 (3), 373–395 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cho, B. K. et al. Genome-scale reconstruction of the sigma factor network in Escherichia coli: topology and functional States. BMC Biol.12, 4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wong, G. T. et al. Genome-wide transcriptional response to varying RpoS levels in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol.199 (7), (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Seo, S. W. et al. Decoding genome-wide GadEWX-transcriptional regulatory networks reveals multifaceted cellular responses to acid stress in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun.6, 7970 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yamaguchi, Y. et al. Effects of disruption of heat shock genes on susceptibility of Escherichia coli to fluoroquinolones. BMC Microbiol.3, 16 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eadsforth, T. C. et al. Assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa N5,N10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase-cyclohydrolase as a potential antibacterial drug target. PLoS ONE7 (4), e35973 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nakamoto, R. K. et al. Molecular mechanisms of rotational catalysis in the F(0)F(1) ATP synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1458 (2–3), 289–299 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mackieh, R. et al. Inhibitors of ATP synthase as new antibacterial candidates. Antibiotics (Basel)12 (4), (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 104.Dwyer, D. J. et al. Gyrase inhibitors induce an oxidative damage cellular death pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol.3, 91 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Charlier, D., Nguyen, P., Le Minh & Roovers, M. Regulation of carbamoylphosphate synthesis in Escherichia coli: an amazing metabolite at the crossroad of arginine and pyrimidine biosynthesis. Amino Acids50 (12), 1647–1661 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mushtaq, A. et al. Carbamoyl phosphate synthase subunit CgCPS1 is necessary for virulence and to regulate stress tolerance in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Plant. Pathol. J.37 (3), 232–242 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhuo, T. et al. Molecular study on the carab Operon reveals that carb gene is required for swimming and biofilm formation in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. BMC Microbiol.15, 225 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Njenga, R. et al. Coping with stress: how bacteria fine-tune protein synthesis and protein transport. J. Biol. Chem.299 (9), 105163 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Aseev, L. V., Koledinskaya, L. S. & Boni, I. V. Extraribosomal functions of bacterial ribosomal proteins-an update, 2023. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25 (5), (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Kaczanowska, M. & Ryden-Aulin, M. Ribosome biogenesis and the translation process in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.71 (3), 477–494 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lhoest, J. & Colson, C. Cold-sensitive ribosome assembly in an Escherichia coli mutant lacking a single methyl group in ribosomal protein L3. Eur. J. Biochem.121 (1), 33–37 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee, H. T. et al. A novel peptide nucleic acid against the cytidine monophosphate kinase of S. aureus inhibits Staphylococcal infection in vivo. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids18, 245–252 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gaca, A. O., Colomer-Winter, C. & Lemos, J. A. Many means to a common end: the intricacies of (p)ppGpp metabolism and its control of bacterial homeostasis. J. Bacteriol.197 (7), 1146–1156 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Abdelwahed, E. K. et al. Gene networks and pathways involved in Escherichia coli response to multiple stressors. Microorganisms10 (9), (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Munoz-Elias, E. J. & McKinney, J. D. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacteria. Cell Microbiol.8 (1), 10–22 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tarrant, E. et al. Copper stress in Staphylococcus aureus leads to adaptive changes in central carbon metabolism. Metallomics11 (1), 183–200 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Leonard, A. et al. Exploring metabolic adaptation of Streptococcus pneumoniae to antibiotics. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo)73 (7), 441–454 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sivapragasam, S. & Grove, A. The link between purine metabolism and production of antibiotics in Streptomyces. Antibiotics (Basel)8 (2), (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 119.Liu, X. et al. Transcriptomics and metabolomics reveal the adaption of Akkermansia muciniphila to high mucin by regulating energy homeostasis. Sci. Rep.11 (1), 9073 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Qiao, Y. et al. Metabolic pathway profiling in intracellular and extracellular environments of Streptococcus thermophilus during pH-controlled batch fermentations. Front. Microbiol.10, 3144 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Leiva, L. E. & Katz, A. Regulation of leaderless mRNA translation in bacteria. Microorganisms10 (4), (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 122.Turnbough, C. L. Jr. & Switzer, R. L. Regulation of pyrimidine biosynthetic gene expression in bacteria: repression without repressors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.72 (2), 266–300 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Garavaglia, M., Rossi, E. & Landini, P. The pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthetic pathway modulates production of biofilm determinants in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE7 (2), e31252 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rytter, H. et al. The pentose phosphate pathway constitutes a major metabolic hub in pathogenic francisella. PLoS Pathog.17 (8), e1009326 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Christodoulou, D. et al. Reserve flux capacity in the pentose phosphate pathway by NADPH binding is conserved across kingdoms. iScience19, 1133–1144 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Oikawa, T. Alanine, aspartate, and asparagine metabolism in microorganisms. (2006).