Abstract

Background

Glioblastoma is the most aggressive and malignant brain tumor, characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity, invasiveness, and resistance to treatment. Patients with glioblastoma have a very poor prognosis despite multimodal interventions. In this study, we investigated how 18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT) PET combined with contrast-enhanced MRI and blood metabolomics can contribute to evaluate prognosis and treatment response for patients with glioblastoma.

Methods

Patients, scheduled for surgery due to suspected high-grade glioma were included in this clinical study and underwent four 18F-FLT-PET/MRI examinations prior to surgery and during standard treatment. Blood samples were collected and analyzed by metabolomics. Patients were grouped according to survival as long-time survivors (>3 years) and short-time survivors (<500 days).

Results

Both 2 and 6 weeks into treatment, short-time survivors displayed a significantly larger tumor volume than long-time survivors. When comparing MRI findings during treatment, long-time survivors displayed a substantial tumor decrease, whereas the short-time survivors showed minor or no effect. Regarding 18F-FLT-PET the results were not as unambiguous. Furthermore, there was a clear and significant separation in the metabolomic pattern in blood between the survival groups and across treatment time points.

Conclusions

MRI measures of tumor volume and growth during treatment appear to be prognostic clinical factors that affect outcome. Metabolomic patterns in blood differ significantly between the defined survival groups and may serve as support for an early forecast of prognosis. We also observe a clear separation in metabolite levels between different time points during treatment, which likely reflects treatment effects.

Keywords: glioblastoma, metabolomics, prognosis, PET

Key Points.

Changes in tumor volume on MRI during treatment is a prognostic factor.

Blood metabolomics has the potential to forecast prognosis and detect the effect of treatment.

18F-FLT-PET does not show clear correlations between survival groups or during treatment.

Importance of the Study.

The interpretation of PET in glioblastoma is difficult and sparsely researched. In this clinical PET/MRI study, 18F-FLT is used as a tracer and metabolomics is sequentially analyzed in blood samples during treatment. Significant changes in tumor volume on contrast-enhanced MRI but not SUV-activity in 18F-FLT/PET harbors prognostic information both during treatment and between groups of long- and short-time survivors. Changes in blood metabolomics during treatment and between survival groups are interesting and suggest new contributions to the field.

Glioblastoma is the most common and most aggressive malignant primary brain tumor, affecting nearly 400 patients per year in Sweden. The age-adjusted incidence in 2015 was 3.8 per 100 000 (data from the Swedish Cancer Registry). In the United States, the annual incidence of primary malignant brain tumors is approximately 7 per 100 000 individuals of which approximately 49% are glioblastomas.1 The disease is for unknown reasons slightly more common in men. The incidence seems to be stable over the years and the cause is in most cases unknown. Many attempts have been made to improve survival, but the prognosis is still discouraging with a median overall survival around 12–14 months in clinical cohorts,2 and less than 10% of patients with high-grade gliomas survive longer than 5 years.3 Standard treatment for patients in good performance status and age under 70 is surgery, followed by radio-chemotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy, and since 2019 in Sweden, tumor-treating-fields (TTF), a treatment with low-intensity, intermediate-frequency alternating electric-fields (Optune®), Novocure GmbH, Munich, Germany.4–6

During and after treatment, patients are followed with contrast-enhanced MRI, every 2 to three months according to Swedish national guidelines. In Swedish and European guidelines, amino-acid-PET is recommended in some clinical situations when MRI is difficult to interpret.6 The tracer used in this study,18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT), is not an amino acid but a marker for proliferation and this makes it a good candidate for clinical use in this highly aggressive tumor. Since glioblastoma is an aggressive and many times fast-growing tumor there is an unmet need to measure treatment response by monitoring active tumor proliferation and/or changes in metabolomics, rather than imaging macroscopic changes that tend to take longer to appear on MRI. Despite full treatment, the disease almost always relapses or continues to progress. To increase the chances to affect outcome we need methods to forecast early treatment response. Further, a fairly large fraction of patients who planned to receive full adjuvant treatment have to interrupt treatment due to the progress of disease or toxicity.2 In some cases, clinical deterioration does not correlate with the radiologic findings why other methods, like for example liquid biopsies or blood metabolomics would be an important contribution to better understanding the development of the disease.

In this prospective clinical study, we included patients who were planned for surgery and radio-chemotherapy due to suspected glioblastoma. After signing informed consent they underwent standard treatment with surgery, radio-chemotherapy, and adjuvant chemotherapy. Two patients were additionally treated with TTF. In addition to standard examinations, patients provided blood samples for metabolomics and sequentially performed 18F-FLT-PET/MRI before surgery, before the start of radio-chemotherapy, after 2 weeks of radio-chemotherapy, and at the end of radio-chemotherapy. The aim of this study was to evaluate if 18F-FLT-PET/MRI and metabolomic patterns in blood added value to forecast prognosis and treatment response.

Materials and Methods

Patients/Study Design

This 18F-FLT-PET/MRI study included 35 patients with high-grade glioma and was performed at Umeå University Hospital between 2015 and 2019. The inclusion criteria for the study were adult patients (age > 18) with suspected high-grade glioma, planned for surgery and oncological treatment. Patients were included in the study after signing informed consent according to GCP and the Helsinki declaration. Ethical approval was obtained from the regional Ethics Committee in Umeå (Dnr: 2010-84-31 and 2014-383-32M).

The patient handling involved a baseline preoperative combined 18F-FLT-PET/MRI, followed by surgery which was planned based on the MRI images. Tumor tissue samples were collected at the Department of Neurosurgery, Umeå University Hospital, as part of the U-CAN project.7 DNA was isolated from fresh frozen tumor tissue samples using the NucleoSpin Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel) as described by the manufacturer. Glioma classification was performed in accordance with the 2016 WHO classification of tumors of the CNS and subsequent cIMPACT-NOW additions. Surgery was followed by a postoperative MRI within 48 hours, according to standard clinical routine, to obtain a baseline image before the known post-surgical MRI signal enhancements had appeared. The plan for the included patients was to perform three additional 18F-FLT-PET/MRI acquisitions before and during treatment to evaluate treatment response. Patients were treated according to clinical routine with six weeks of radiotherapy with 60 Gy in 30 fractions and temozolomide 75 mg/m2, starting 3–5 weeks after surgery. Four weeks after fulfilling radio-chemotherapy patients were treated with adjuvant temozolomide 150–200 mg/m2 (planned for 6 cycles). Two patients were treated with TTF (which was introduced in Sweden in 2019). Blood samples for metabolomics were acquired the same day as each FLT-PET/MRI scan. Due to technical issues and in some cases, deterioration of the patients during treatment all patients did not perform all planned investigations. The naming and purpose of the radiological examinations are summarized in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Timeline summarizing the experimental protocol, and oncological treatment. (A) Scan 1: FLT-PET/MRI before surgery (pre-op). Scan 2: MRI within 48 hours after surgery (post-op MRI). Scan 3: FLT-PET/MRI before radio-chemotherapy (time t = 0, post-op PET). Scan 4: FLT-PET/MRI after 2 weeks of radio-chemotherapy (t = 2w). Scan 5: FLT-PET/MRI at the end of 6 weeks of radio-chemotherapy (t = 6w). (B) Typical PET and MRI images, with thresholded PET volume indicated to the left, and the same region transferred to the MRI image to the right. The white contrast visible in the MRI is what will be measured as the MRI tumor volume. Due to PET resolution, the measured PET volume is larger than the contrast loading tumor edge on the MRI. (C) MRI volume (Vtumor) changes as a function of time. Absolute volume from pre-operation scan to end of treatment. Data points for each group and time point are calculated as the median of individual tumor volumes. (D) MRI volume change relative post-op MRI. Data points for each group and time point are calculated as median of individual [scan-volume]/[post-op volume] ratios.

At the time of analysis, patients were divided into groups according to survival after diagnosis, where short-time survivors had an overall survival less than median, 500 days (N = 18 patients), and long-time survivors more than 3 years (N = 6 patients). Patients with survival between 500 days and 3 years (N = 11 patients), were omitted from systematic analysis, resulting in 24 patients included in the final analysis. The reasoning behind the division of patients into these groups was that we wanted to characterize features of slower-growing and faster-growing tumors; by omitting intermediate survivors the chance to have distinctively different tumor populations would be greatly enhanced. The patients with survival between 500 days and 3 years (N = 11 patients) were analyzed for the MRI imaging measures to find out if these patients behaved similarly to either the short- or long-time survivors.

Imaging

A 45-minute simultaneous 18F-FLT-PET/MRI acquisition commenced 40 minutes post-injection of 2.6 MBq/kg 18F-FLT. The PET acquisition was reconstructed to form 89 slices of 192 × 192 pixel attenuation-corrected PET images, with voxel size 3.125 × 3.125 × 2.78 mm3. Multiple MRI protocols were acquired, and here we analyzed the intravenously injected gadolinium (Dotarem®, 279.3 mg/ml, dosed 0.2 ml/kg) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI image of 196 slices and 512 × 512 pixels, with voxel size 0.49 × 0.49 × 1.0 mm3. PET images were re-sampled into the matrix of the T1-weighted images prior to analysis.

Image Analysis

Blinded image analysis was performed with imlook4d (https://sites.google.com/site/imlook4d). PET images are converted to standardized uptake values (SUV),8 with the tumor aggressiveness quantified as the most intense voxel (SUVmax) within a delineated PET volume (see below).

The contrast-enhanced tumor volume (Vtumor) on MRI and necrosis (Vnecrosis) were manually delineated slice by slice, giving the 2 volumes in cm3. The total tumor volume was calculated as Vtotal = Vtumor + Vnecrosis. The volume Vtumor was considered as the active tumor tissue.

The PET-active tumor volume (VPET) was delineated using all voxels above a threshold level T, inside a manually delineated search volume. The threshold level was set to 40% of the SUVmax intensity above the background, which was calculated as

T = 0.4 (SUVmax—SUVbkg) + SUVbkg, where the background activity SUVbkg is the mean activity in a contralateral region of interest, and SUVmax is the voxel with the highest SUV in the tumor search volume. The threshold formula using contralateral ROI value SUVbkg was necessary for scan 1, where it allowed capturing the thin uptake around the necrotic area (which has low intensity caused by partial-volume effects). An example of thresholded PET volume, and contrast-enhanced MRI is displayed in Figure 1B.

The parameters calculated from each scan were the median values of SUVmax, VPET, Vtumor, and Vtotal, for the two groups. New parameters, describing the change in a parameter value, were calculated on each individual patient. This change thus reflects changes where the individual is under their own control. These patient changes were calculated by two methods: A) as a difference between scans, for instance Vtumor between scans 5 and 2 as Vtumor5- Vtumor2; and B) as a ratio, for instance, Vtumor5/Vtumor2. These parameters were calculated to reflect changes relative to the post-op scan (scan 2 for MRI and scan 3 for PET). Since we did not observe any necrosis post-surgery, we only tabulate data for the first scan of Vtotal (because the values Vtotal = Vtumor for scans without necrosis).

IDH-Mutation Analyses

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) assay P088-C2 (lot C2-0416) was used to detect four common IDH1- and IDH2-mutations: IDH1-R132H, IDH1-R132C, IDH2-R172K, and IDH2-R172M. All MLPA analyses were performed as described by the manufacturer (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and interpreted by an expert geneticist.

O6-Methylguanine-DNA-Methyltransferase (MGMT)-Promoter-Analyses

The pyrosequencing assay was performed using the therascreen MGMT Pyro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR products were subjected to pyresequencing on a Pyromark Q24 System (Qiaqen, Hilden, Germany). Tumor samples with MGMT-promoter methylation <10% were considered as unmethylated and >10% as methylated.

Metabolomics

Blood (30 ml) was sampled at the time points of the PET/MRI scans and centrifugated at 3600 rpm at 4 °C for 15 minutes. Plasma was then transferred to Cryo Tubes and stored at −80 °C. Plasma samples were randomly divided into analytical groups based on patient ID. Plasma samples taken at different PET/MR scans (pre-op, before radio-chemotherapy, 2 weeks into radio-chemotherapy, and at the end of radio-chemotherapy) from the same patient were consequently run together and directly adjacent to each other in randomized order, thereby minimizing variability in platform performance for individual patients. We incorporated quality control measures by including pooled quality control plasma samples approximately between every twentieth analytical sample. Quality control samples were used to monitor platform performance and to calculate technical reproducibility by means of relative standard deviation (RSD%) for all quantified metabolites. Untargeted metabolomic analysis was done using Metabolon Inc. global metabolomics platform based on four Ultrahigh Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectroscopy methods, in both positive and negative electrospray ionization mode. All analytical samples were run during one analysis day to avoid day-to-day batch effects. The obtained metabolomics data set based on quantified peak areas for named and unnamed metabolites was curated prior to statistical analysis. For multivariate statistical analysis, missing values due to biological reasons or under the limit of quantification were imputed with half of the minimum intensity detected for that metabolite. To avoid distorting the data due to the imputation of many variables, we completely excluded metabolites that were missing in >50% of samples at any of the four PET/MR occasions when blood samples were collected. We also excluded identified drugs and exogenous metabolites, as well as unnamed metabolic features representing metabolites with unknown identity. After completing data curation, 663 identified and named metabolites remained for statistical analysis. The median RSD%QC for these metabolites was 7.1% and 97.7% of all named metabolites had an RSD% below 30.

Statistics

Imaging Data.—

Statistical analysis between groups was performed using a one-sided Student’s t-test, and a one-sided Mann–Whitney U non-parametric test in case non-normality was found with Shapiro–Wilk Normality test (P < .05). Both the one-sided tests compared if values for long-time survivors were less than for short-time survivors, which is the expected result for both volume and SUV measures for long-time survivors compared to short-time survivors. Statistics were performed in R, version 4.2.2 (R Core Team (2022). R: https://www.R-project.org/).

Patient population.—

For comparisons between the survival groups regarding age, WHO PS and MGMT-status SPSS, version 28.0 (IBM Corp) was used with Pearson Chi-Square test and results were considered significant if P < .05.

Metabolomics.—

Statistical analyses of the curated and log2-transformed data set were performed using SIMCA (version 17.0, Sartorius Stedim Data Analytics AB) and MATLAB R2017a (MathWorks, Inc.). As metabolites are not independent variables, we used multivariate statistical analysis to explore the data and establish quantitative relationships between metabolite concentrations, patient groups, or sampling time points. Multivariate modeling was done using Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures (OPLS) discriminant analysis (DA) to model the systematic variation in the metabolomics data related to, and orthogonal to predefined sample classes. OPLS-DA was done using the identified metabolites as input variables, centered and scaled to unit variance, giving each variable equal importance. Similarities between survival and treatment groups were analyzed by agglomerative hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) using Cohen’s d effect sizes as distance metrics for OPLS models and complete linkage for clustering. The concept of combining HCA with the OPLS framework to create a decision tree has been described previously.9,10 The obtained OPLS-Hierarchical Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-HDA) model is built upon a hierarchy of two-class OPLS-DA models and provides an intuitive visualization of inter-class relationships for multiclass analysis. Leave-one-out cross-validated (CV) goodness of prediction Q2-values were used to determine the predictive ability of the models.9 ANOVA based on the cross-validated OPLS-DA models was employed to calculate P-values for the differences between the predefined sample classes in the respective models. To prevent model overfitting, the number of orthogonal components were reduced to the lowest CVANOVAP-value, resulting in one predictive and zero orthogonal component for all two-class models. Results are displayed as cross-validated predictive scores for pairwise OPLS-DA models between overall survival groups and sampling time points. Effect sizes were calculated as fold change between means for each metabolite. Effect sizes and significance levels for each metabolite are shown in volcano plots as log ratios, i.e., log2 fold change versus −log10P-value (two-sided t-test). P-value correction for multiple testing by Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate at alpha < 0.05 for all model comparisons based on 663 metabolites resulted in zero metabolites below alpha. Metabolites with practical significance with a large effect size (>2-fold difference) and with high between-group variation (P < .01) were considered of significant interest and are highlighted in figures and tables.

Results

Patients

Patient characteristics for the study cohort are displayed in Table 1. All patients included in the exploratory analysis were diagnosed with a glioma WHO grade 4. The long-time survivors were diagnosed at a younger (56 years) median age than the short-time survivors (63 years), but this difference was not statistically significant. Both groups had a similar distribution of males and females. Long-time survivors displayed a significantly better WHO performance status at diagnosis, compared to the short-time survivors. All patients in the long-time survival group had a methylated MGMT-promoter (>10%) compared to the short-time survivors where all except two patients had an unmethylated MGMT-promoter (<10%). For one patient in the short-time survival group, MGMT-methylation status is missing. One patient in each survival group had a mutation in IDH (R132H). Patients in the short-time survival and long-time survival groups had a median overall survival of 9.9 months and 5.2 years respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics for Long-Time Survivors (>3 years) and Short-Time Survivors (<500 Days)

| > 3 years | <500 days | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (N) | 6 | 18 | |

| Females (N, %) | 3 (50%) | 10 (56%) | |

| Males (N, %) | 3 (50%) | 8 (44%) | .813 |

| Age diagnosis (years) § | 56 ± 15 | 63 ± 12 | .159 |

| Overall Survival from diagnosis (days) § | 1892 ± 252 | 297 ± 75 | |

| WHO PS 0 (N, %) | 5 (83%) | 4 (22%) | |

| WHO PS 1–3 (N, %) | 1 (17%) | 14 (78%) | .007* |

| MGMT-methylated promoter (N, %)# | 6 (100%) | 2 (12%) | |

| MGMT non-methylated promoter (N, %) | 0 (0%) | 15 (88%) | <.001* |

| IDH-mutation r132h (N, %) | 1 (17%) | 1 (6%) | |

| IDH-wild type (N, %) | 5 (83%) | 17 (94%) | .394 |

| Concomitant TMZ (N, %) | 6 (100%) | 17 (94%) | .555 |

| Adjuvant TMZ (N, %) | 6 (100%) | 14 (78%) | .206 |

| Number of cycles of adjuvant TMZ (mean) | 6 | 3 | |

| TTF (tumor treating fields) (N, %) | 1 (17%) | 1 (6%) | .394 |

| 2:nd line treatment (N, %)# | 6 (100%) | 7 (41%) | .012* |

§Median ± standard deviation.

*Indicate significant P-value <.05.

#Information is missing for one patient.

All patients in the long-time survival group were treated with concomitant temozolomide and six cycles of adjuvant temozolomide, and all were treated with second-line treatment at the first progression: One patient was treated with bevacizumab/lomustine in second-line and re-irradiated with 3,4 Gy in 10 fractions to a total of 34 Gy in third line, one patient had temozolomide in second-line treatment, one patient had temozolomide in second-line treatment and bevacizumab/lomustine in third line, one patient had bevacizumab/lomustine in second-line and 2 patients were treated with temozlomide and then re-irradiated with 3,4 Gy in 10 fractions to a total of 34 Gy. Also, for the short-time survivors, the majority were treated with both concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide, but only 7 patients (41%) had undergone second-line systemic treatment: Four patients were treated with bevacizumab/lomustine, 2 patients in this group was re-operated twice, 1 patient was treated with lomustine, one with bevacizumab and one with temozolomide/bevacizumab (Table 1). Despite radiological progress at 250 and 800 days, respectively, 2 of the patients survived just over five years. At the time of analysis, all short-time survivors were diseased, whereas 2 patients who belonged to the long-time survivors were still alive.

Imaging

The measures of SUV and MRI tumor volumes for scans 1 to 5 are summarized in Table 2. The time course of MRI volumes is visualized in Figure 1C. The MRI measures display a significant difference between long-time and short-time survivors of Vtumor after 6 weeks of treatment (Table 2). Also, for the 2-week measure of Vtumor, the t-test showed a significant difference between long- and short-time survivors respectively, but non-normality for the short-time survivors gave a Mann–Witney U test near significance (P = .05). Even though the distributions of values overlap, all the individual Vtumor measures from the long-time survivors were less than the respective median Vtumor from the short-time survivors; both for the 2- and 6-week time points.

Table 2.

Median Value of SUVmax and Tumor Volumes, for Long-Time Survivors (>3 Years) and Short-Time Survivors (<500 Days)

| Measure | Scan | >3 years | < 500 days | P-value § |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET SUVmax [g/ml] | Scan 1, pre-op | 3.07 | 2.93 | .56 |

| Scan 3, t = 0 weeks | 1.40 | 1.93 | .26 | |

| Scan 4, t = 2 weeks | 0.85 | 1.07 | .34 | |

| Scan 5, t = 6 weeks | 0.79 | 1.03 | .08 | |

| PET VPET [cm3] | Scan 1, pre-op | 50.61 | 34.97 | .88 |

| Scan 3, t = 0 weeks | 7.80 | 11.77 | .40 | |

| Scan 4, t = 2 weeks | 7.37 | 10.18 | .64 | |

| Scan 5, t = 6 weeks | 3.74 | 9.43 | .25 | |

| MRI Vtumor [cm3] | Scan 1, pre-op | 37.76 | 19.91 | .95 |

| Scan 2, post-op | 3.23 | 1.74 | .79 | |

| Scan 3, t = 0 weeks | 3.40 | 7.23 | .22 | |

| Scan 4, t = 2 weeks | 0.70 | 5.29 | .05* | |

| Scan 5, t = 6 weeks | 0.17 | 4.95 | .005* | |

| MRI Vtotal [cm3] (contrast + necrosis) |

Scan 1, pre-op | 49.90 | 31.15 | .97 |

§ P-value comparing groups, for measures and scans described on same line.

*Indicate significant P-value < .05.

Even though short-time survivors showed smaller Vtumor than long-time survivors preoperatively (20 vs 37 cm3) and postoperatively (1.74 vs 3.23 cm3), the short-time survivor’s tumor volumes (7.2 cm3) had surpassed that of the long-time survivors (3.4 cm3) at start of treatment. Expressed differently, the short-time survivors’ median tumor volume doubled in the timespan from operation to start of treatment, whereas the long-time survivors’ median tumor volume changed very little (Table 2).

Measuring the change in tumor volume compared to the postoperative MRI there was a significant difference between long- and short-time survivors; this was evident both 2 and 6 weeks into treatment (Figure 1D). The median tumor volume increase was more than 3 cm3 from operation to end of treatment for the short-time survivors group (Table 3), (“Diff scans 5-2,” short-time survivors), whereas a decrease was found for the long-time survivors. The short-time survivors did not display shrinkage in median tumor difference during treatment, whereas long-time survivors did (Table 3). The same trend is shown when comparing the median ratio of tumor volume relative to the postoperative volume, where substantial shrinkage is seen 2 and 6 weeks into treatment for long-time survivors, but a more than 3-fold median tumor volume increase is seen for the short-time survivors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Median Measurements of Changes in SUVmax and Tumor Volume (PET and MRI), for Long-Time Survivors (>3 Years) and Short-Time Survivors (<500 Days)

| Measure | Scans | >3 years | < 500 days | P-value § |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET change SUVmax [g/ml] | Scan 3/1 | 0.48 | 0.92 | .15 |

| Scan 4/3 | 0.60 | 0.51 | .81 | |

| Scan 5/3 | 0.71 | 0.48 | .95 | |

| PET change VPET [cm3] | Scan 3/1 | 0.13 | 0.31 | .17 |

| Scan 4/3 | 0.73 | 0.98 | .24 | |

| Scan 5/3 | 0.38 | 0.91 | .16 | |

| Diff scans 4–3 | −4.04 | 0.12 | .09 | |

| Diff scans 5–3 | −2.66 | −0.54 | .20 | |

| MRI change Vtumor [cm3] | Scan 2/1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | .32 |

| Scan 3/2 | 1.86 | 2.82 | .22 | |

| Scan 4/2 | 0.38 | 3.92 | .04* | |

| Scan 5/2 | 0.21 | 3.46 | .01* | |

| Diff scans 3–2 | 1.57 | 3.87 | .10 | |

| Diff scans 4–2 | −1.13 | 3.53 | .02* | |

| Diff scans 5–2 | −3.09 | 3.60 | .004* | |

| MRI change Vtotal (contrast + necrosis) [cm3] |

Scan 2/1 | 0.05 | 0.04 | .46 |

§ P-value comparing groups, for measures and scans described on same line.

*Indicate significant P-value < .05.

The delineated PET-active tumor volumes do not display any significant difference between groups but support the same trend as for measured MRI volumes (Tables 2 and 3). The SUVmax measures gave no significant difference between groups, but there is a trend (P = .15) towards long-time survivors having a median reduction in SUVmax following operation (Table 3, “Scan 3/1”).

Blood Sample Metabolomics

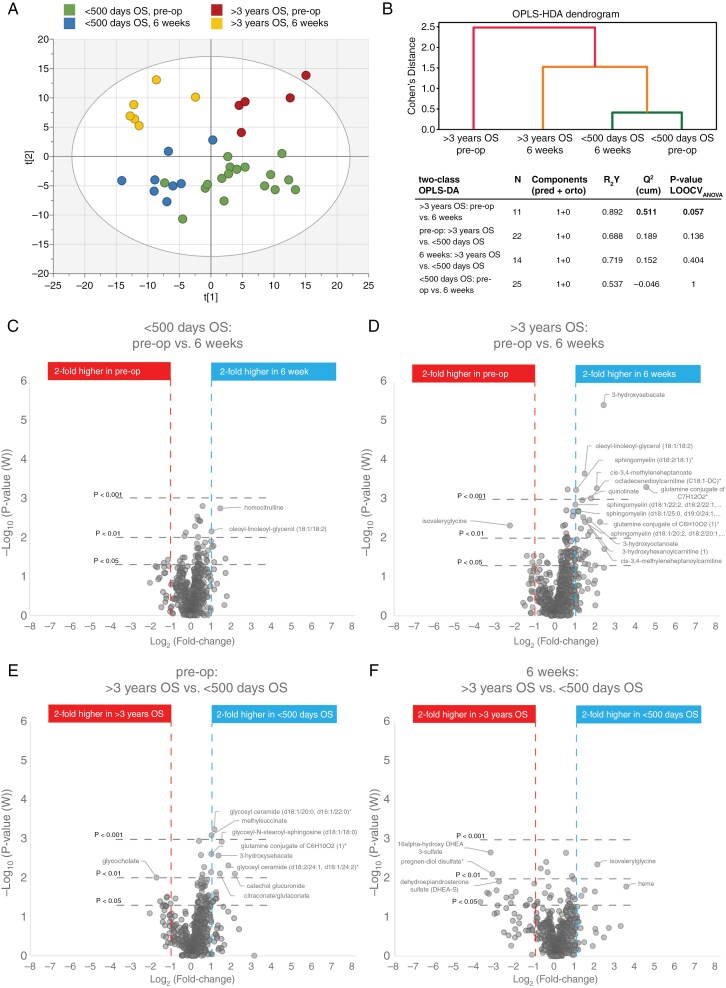

Blood samples for metabolite analysis were collected on the same day as for each PET/MRI scan. The blood metabolome was quantified by Metabolon Inc. global metabolomic analysis platform. After stringent data curation, 663 quantified and named metabolites were obtained for multivariate statistical analysis. We used the same patient grouping according to survival time for the blood metabolite analysis, as used for image analysis. Multivariate modeling of the two survival groups; <500 days and >3 years, before surgery (pre-op) and at the end of radio-chemotherapy (6 weeks) showed a clear separation of the survival groups (Figure 2A). The short- and long-time survivors did not overlap, and samples from the long-time survivors separated clearly from each other before and after the completed treatment (Figure 2A). To further illustrate phenotypic similarities or differences between each of the survival and sampling timepoint, we also used agglomerative hierarchical clustering for each class of patient groups based on the OPLS-Hierarchical Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-HDA) method.9,10 The dendrogram generated for the OPLS-HDA model shows the relationships between all four classes (Figure 2B). Using this approach, the >3 years OS groups were clearly separated from the <500 days OS groups. Large differences between classes were seen for the >3 years OS groups, pre-op and after 6 weeks of treatment, indicating a strong treatment response. In contrast, the <500 days OS group showed high similarity between pre-op and 6 weeks of treatment, indicating a weak treatment response (Figure 2B). A pairwise investigation of the defined survival groups and sampling time points was conducted to better understand their metabolic differences (Figure 2B). The strongest multivariate model was obtained for the >3 years group before surgery and after completed treatment (Q2 = 0.51, P = .057), while a non-satisfactory model with negative Q2-value was obtained for the short-time survivors before and after completed treatment.

Figure 2.

Blood metabolomic analysis based on patient survival groups and sampling time points. (A) Four class Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures (OPLS)-DA model for blood metabolites based on patient survival time and sampling time point. (B) The dendrogram shows similarities between the 4 classes of survival and treatment groups by use of OPLS-HDA. Table with model characteristics for two-class OPLS-DA comparisons based on the same patient grouping as shown in dendrogram and in A. (C-F) Volcano plots highlighting individual metabolites with practical significance (>2-fold difference and P < .01) for each two-class comparison.

We made use of volcano plots to highlight individual metabolites responsible for the observed separation of survival groups in our pairwise comparison (Figure 2C-F). Metabolites with practical significance for metabolic phenotyping of brain tumors9 with large effect size (>2-fold difference) and with high between-group variation (P < .01) were considered of significant interest and were highlighted in the volcano plots and listed in Table 4. Analysis of individual blood metabolites revealed a very weak treatment response for the short-time survivor group. However, a strong treatment response was observed for the >3 years survival group. Here, the separation before and after completed treatment was predominantly an effect of higher levels of metabolites related to fatty acid and sphingolipid metabolism (Figure 2D and Table 4). Especially including specific acylcarnitines, sphingomyelins, and cis-3,4-methylylated metabolites involved in fatty acid transport and their metabolism. When comparing the short- to long-time survival groups, higher levels of blood metabolites related to hydroxy-, and methyl-branched fatty acids, were detected in the <500 days group compared to >3 years group before treatment (Figure 2E and Table 4). Levels of hexosylceramides in the form of glycosylated metabolites were also elevated in the short-time survivors. After 6 weeks completed treatment, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) related metabolites were significantly higher in the >3 years survival group compared to short-time survivors (Figure 2F and Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics for Significantly Altered Metabolites (>2-fold Difference and P < .01) for Compared Survival and Treatment Groups

| Survival or treatment group comparisons | Metab. levels§ | P-value | Fold change | Biochemical class | Pathway | HMDB ID | Pubchem ID | RSD%QC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <500 days OS; 6 weeks vs. pre-op | In 6 weeks: | |||||||

| oleoyl-linoleoyl-glycerol (18:1/18:2) | ↑ | .0071 | 2.1 | Lipid | Diacylglycerol | HMDB0007219 | 71433693 | 6.5 |

| homocitrulline | ↑ | .0018 | 2.8 | Amino Acid | Urea cycle; Arginine and Proline Metab. | HMDB0000679 | 65072 | 15.9 |

| >3 years OS; 6 weeks vs. pre-op | In 6 weeks: | |||||||

| sphingomyelin (d18:2/18:1)* | ↑ | .00058 | 2.1 | Lipid | Sphingomyelins | HMDB0001348 | 52931155 | 7.0 |

| sphingomyelin (d18:1/22:2, d18:2/22:1, d16:1/24:2)* | ↑ | .0014 | 2.0 | Lipid | Sphingomyelins | HMDB0240670 | 52931199 | 5.4 |

| sphingomyelin (d18:1/25:0, d19:0/24:1, d20:1/23:0, d19:1/24:0)* | ↑ | .0020 | 2.2 | Lipid | Sphingomyelins | HMDB0240671 | 44260137 | 16.1 |

| sphingomyelin (d18:1/20:2, d18:2/20:1, d16:1/22:2)* | ↑ | .0038 | 2.8 | Lipid | Sphingomyelins | 52931175 | 14.9 | |

| cis-3,4-methyleneheptanoate | ↑ | .00053 | 4.2 | Lipid | Fatty Acid, Branched | 84081620 | 14.1 | |

| cis-3,4-methyleneheptanoylcarnitine | ↑ | .0029 | 2.7 | Lipid | Fatty Acid Metab. (Acyl Carnitine) | 129691996 | 2.9 | |

| cis-3,4-methyleneheptanoylglycine | ↑ | .0069 | 3.4 | Lipid | Fatty Acid Metabolism (Acyl Glycine) | 129822188 | 7.8 | |

| octadecenedioylcarnitine (C18:1-DC)* | ↑ | .0009 | 3.5 | Lipid | Fatty Acid Metabolism (Acyl Carnitine) | HMDB0240778 | 71464570 | 9.4 |

| 3-hydroxyhexanoylcarnitine | ↑ | .0021 | 2.2 | Lipid | Fatty Acid Metabolism (Acyl Carnitine) | HMDB0013131 | 76043853 | 6.4 |

| tetradecadienedioate (C14:2-DC)* | ↑ | .0057 | 2.4 | Lipid | Fatty Acid, Dicarboxylate | 86018718 | 2.5 | |

| 3-hydroxyoctanoate | ↑ | .0034 | 3.3 | Lipid | Fatty Acid, Monohydroxy | HMDB0001954 | 26613 | 8.3 |

| 3-hydroxysebacate | ↑ | .0000038 | 5.4 | Lipid | Fatty Acid, Monohydroxy | HMDB0000350 | 3017884 | 12.7 |

| 3-hydroxybutyroylglycine* | ↑ | .0084 | 3.2 | Lipid | Fatty Acid Metabolism (Acyl Glycine) | 89458166 | 6.5 | |

| oleoyl-linoleoyl-glycerol (18:1/18:2) | ↑ | .00022 | 2.8 | Lipid | Diacylglycerol | HMDB0007219 | 71433693 | 6.5 |

| quinolinate | ↑ | .0011 | 2.6 | Dicarboxylic acid | Kynurenine; Nicotinamide Metabolism | HMDB0000232 | 1066 | 11.1 |

| isovalerylglycine | ↓ | .0048 | 0.21 | Amino Acid, -acyl | BCAA Metabolism | HMDB00678 | 546304 | 16.4 |

| glutamine conjugate of C7H12O2 | ↑ | .00049 | 23.3 | Partially characterized | 11.7 | |||

| glutamine conjugate of C6H10O2 | ↑ | .0039 | 4.7 | Partially characterized | 12.5 | |||

| pre-op; < 500 days OS vs. > 3 years OS | In < 500d: | |||||||

| glycosyl ceramide (d18:1/20:0, d16:1/22:0)* | ↑ | .00057 | 2.2 | Lipid | Hexosylceramides | HMDB0004973 | 20057356 | 9.4 |

| glycosyl ceramide (d18:2/24:1, d18:1/24:2)* | ↑ | .0048 | 3.6 | Lipid | Hexosylceramides | 10700574 | 6.1 | |

| glycosyl-N-stearoyl-sphingosine (d18:1/18:0) | ↑ | .0012 | 2.9 | Lipid | Hexosylceramides | 45039326 | 11.6 | |

| 3-hydroxysebacate | ↑ | .0027 | 2.6 | Lipid | Fatty Acid, Monohydroxy | HMDB0000350 | 3017884 | 12.7 |

| Methylsuccinate | ↑ | .0008 | 2.0 | Fatty acyls | Methyl-branched fatty acid | HMDB0001844 | 10349 | 17.5 |

| citraconate/glutaconate | ↑ | .0077 | 2.7 | Fatty acyls | Methyl-branched fatty acid | HMDB0000634 | 643798 | 7.2 |

| catechol glucuronide | ↑ | .0079 | 4.5 | Phenolic glycoside | Tyrosine Metabolism | HMDB0240490 | 75124209 | 25.1 |

| Glycocholate | ↓ | .0098 | 0.30 | Lipid | Primary Bile Acid Metabolism | HMDB0000138 | 10140 | 4.2 |

| glutamine conjugate of C6H10O2 | ↑ | .0024 | 2.0 | Partially characterized | 12.5 | |||

| 6 weeks; < 500 days OS vs. > 3 years OS | In < 500d: | |||||||

| Isovalerylglycine | ↑ | .0043 | 4.2 | Amino Acid, acyl | BCAA Metabolism | HMDB00678 | 546304 | 16.4 |

| 16alpha-hydroxy DHEA 3-sulfate | ↓ | .0021 | 0.11 | Lipid | Androgenic Steroids | HMDB0062544 | 20848950 | 5.8 |

| pregnen-diol disulfate* | ↓ | .0076 | 0.11 | Lipid | Pregnenolone Steroids | 121596229 | 4.2 |

§Arrows indicate higher (↑) or lower (↓) metabolite levels for the named group in each comparison.

*Indicates a compound that has not been confirmed based on a reference standard but still identified with high confidence.

Discussion

The aim of this clinical study on patients with high-grade glioma was to evaluate if 18F-FLT-PET/MRI and metabolomic patterns in blood added value to forecast prognosis and treatment response. From the analysis of the patient characteristics, expected clinical positive prognostic factors such as better WHO performance status and a trend to younger age were found. More patients in the long-time survival group compared to the short-time survival group had a methylated (silenced) MGMT-promoter which is a well-known predictive (and prognostic) factor.11

Since patients with glioblastoma suffer from poor prognosis and few treatment alternatives it is important to find new tools to assess treatment response and to help differentiate patients in need of change of treatment earlier than what is possible today. When changes in tumor volume are to be seen in MRI it is often too late to accomplish meaningful changes in treatment decisions that affect outcome. The use of amino-acid PET in patients with glioma is recommended both in Swedish national guidelines6 in special situations and in European guidelines.12 However, PET imaging in brain tumors is somewhat challenging. The tumor may be protected by the blood-brain barrier making the choice of tracer important. Tumor vessels are often leaky and immature and whether the blood-brain barrier is a clinical issue or not is debated.1318F-fluorodeoxyglukos (18F-FDG) is the most common tracer for other malignancies but since the normal brain consumes a high amount of glucose it may be difficult to differentiate the brain tumor from normal brain tissue. In this study, we examined a different tracer, 18F-FLT which is a marker for tumor cell proliferation in glioblastoma.14 Therefore, we hypothesized that it would make a good candidate for forecasting prognosis and perhaps a response to treatment in this highly aggressive tumor.

To summarize the statistical treatment of MRI and PET measures: (i) the group median values are first presented (Table 2), with the shortcoming that the median values will most likely arise from different patients in different scans; (ii) the median of individual-patient changes are then presented (Table 3), with the benefit that the median of a ratio or a difference measure is calculated from the same patient.

The 18F-FLT-PET results were not as we had hypothesized. We believe that one important factor to this is that the limited PET scanner resolution, together with the varying size and shape of the relatively small postoperative remaining tumor, causes individual variations in the partial-volume effect. This means that there is an individual scale factor (often referred to as recovery coefficient) that would introduce a large variance between individual patients, which may very well be larger than the variance in tumor growth rate (which is what we probe with 18F-FLT). So, even though we saw trends in SUVmax decreasing after operation for the long-time survivors (Table 3,” Scan 3/1”), such change could very well have been significant on the cell level, without being possible to measure accurately with PET.

The nonsignificant trend towards lowering SUVmax for long-time survivors, but not for short-time survivors, may reflect something real. This result may indicate that a fast-growing tumor cell population remained after operation in short-time survivors indicated by a SUVmax ratio post-op/pre-op being around one (0.9) for short-time survivors, but much lower (0.5) for long-time survivors. This is supported by the trend of Vtumor tumor growth from operation to the start of treatment (Table 3,” Scan 3/2”). None of the results in this section gave statistical significance, neither by measuring group-level changes (Table 2) or changes in the median tumor (Table 3).

In this analysis, we omitted the intermediate-time survivors (500 days < overall survival < 3 years) since we wanted clearly separated survival groups. It is still interesting to get an understanding of the general behavior of this intermediate group, which we briefly tested using the MRI imaging measures (data not shown). Comparing the intermediate-time survivors to short-time survivors, none of the MRI measures were significantly different. Similarly, long- and intermediate-survivor groups showed significant differences in some of the MRI measures that also were present in the long-time vs short-time survival comparison. This suggests that short- and intermediate-time survivor groups are similar.

There is nothing in this study that contradicts that 18F-FLT-PET would be useful to give complementary information to MRI-based radiation therapy target delineation. We have in a few cases noted that incorporating PET information into the MRI delineations would have added small regions that were unique to PET. This aspect could not be quantified by a gross tumor value, as used in this study, but is something that we believe is worth a future study. It is not unthinkable that the outcome of treatment could benefit from removing or targeting these extra volumes during surgery and/or radiotherapy. Using PET for target volume definition in glioblastoma in radiotherapy is endorsed by the 2023 ESTRO-EANO guidelines.15

We conclude that 18F-FLT-PET is not robust enough to predict outcomes for glioblastoma patients, whereas MRI data does show potential to predict treatment response. There is some evidence in the literature that glioblastoma with MGMT-methylated promoters exhibits more often pseudo-progression during follow up and this is often evident during adjuvant therapy.16,17 In this study the last follow-up is at the end of radio-chemotherapy and at this time point we do not observe any increase in tumor volume indicating early pseudo-progression. We do not have information on tumor volume at a later stage. The results from this clinical study show that patients whose tumors shrink during primary radio-chemotherapy live longer. We did not find significant changes in SUV between groups. Several factors could explain this negative finding, such as differences in blood-brain-barrier leakage, or treatment affecting proliferation differently between patients.

Metabolomic analysis of blood samples collected before and after 6 weeks of completed treatment was able to distinguish prognostic metabolites related to poor survival, and metabolites related to a positive treatment response (Table 4). When comparing the short- to long-time survival groups before treatment, we observe higher levels of hydroxy-, and methyl-branched fatty acids, which may signal an increased level of ketoacidosis and/or incomplete fatty acid oxidation, in the short-time survival group.18,19 Hydroxy- and methyl-branched fatty acids are known to be involved in various metabolic pathways, including the synthesis of complex lipids and energy production. However, accurately mapping altered blood metabolites to specific intracellular pathways remains challenging, often rendering conclusions somewhat speculative. Elevated levels of these fatty acids may indicate metabolic stress and impaired mitochondrial function, which are often associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients.20,21 Blood plasma levels of glycosyl sphingolipids were also elevated in the short-time survivors (Figure 2E and Table 4). Glycosyl ceramides and glycosyl sphingosines are involved in maintaining cell membrane stability and are crucial for the membrane’s structural and functional properties.22 These metabolites may also play an important role in cell signaling and the immune response.23 Glycosyl sphingolipids are essential for cell–cell interactions, signal transduction, and immune modulation.24 Their elevated levels could reflect an adaptive response to cellular stress or an attempt to maintain cellular integrity under adverse conditions. Ceramide is widely known for activating signals of cell death leading to deterioration of cell survival.25 Ceramides can induce apoptosis through various mechanisms, including the activation of caspases and the disruption of mitochondrial function.26,27

The positive treatment response seen in blood samples from the >3 years survival group after completed treatment (Figure 2D), was predominantly related to higher levels of metabolites associated with fatty acid and sphingolipid metabolism. This was observed as higher levels of metabolites related to medium-chain fatty acid transport for oxidation, acylcarnitines linked to beta-oxidation, and higher blood levels of sphingomyelins. These observations may highlight the benefits of high energy production. Medium-chain fatty acids are more readily oxidized than long-chain fatty acids, providing a quick source of energy for cells. Additionally, acylcarnitines facilitate the transport of long-chain fatty acids into mitochondria for beta-oxidation, which is also crucial for maintaining high energy production and cellular metabolism.28 On the other hand, sphingomyelins are found in cell membranes, especially in myelin sheaths, and play a role in signal transduction such as proliferation/survival, migration, and inflammation.29 Sphingomyelin synthase 1 is the primary enzyme that generates sphingomyelin. Interestingly and relevant to our findings, a study showed that median, 2- and 5-year survival were significantly better for glioma patients with high sphingomyelin synthase 1 expression, whereas patients with low sphingomyelin synthase 1 expression had worse prognosis.30 Sphingomyelins are involved in the formation of lipid rafts, which are specialized membrane microdomains that facilitate signal transduction, protein sorting and play functional roles in immunity.31,32 While speculative, elevated sphingomyelin levels in long-term survivors may enhance cellular communication and support a more robust immune response. Combined with improved energy turnover, these factors could have contributed to more favorable treatment outcomes.

There was a clear separation in the metabolomic pattern in blood between the time-points before surgery and after treatment for the long-time survivors (Figure 2A and D) but not for the short-time survivors (Figure 2A and C). The non-satisfactory model with negative Q2-value obtained for the short-time survivors before and after completed treatment indicates a weak metabolic response to treatment in the short-time survival group (Figure 2B and C). We show that blood-based metabolomics offers the potential to analyze cellular events downstream, enabling the detection of changes in blood that reflect earlier processes within the tumor. This approach may serve as a valuable component of liquid biopsy, providing insights into the tumor’s biological characteristics that could aid in predicting prognosis and tailoring treatment strategies. Others have also found relations between blood levels of metabolites associated with tumor hypoxia and treatment outcome of bevacizumab which further reflects the use of metabolomics as predictive markers for treatment.33

This study is limited by the relatively low number of participants and uneven group sizes. We do, however, not believe that larger groups would change the results in any major way since the groups were made homogenous by omitting the intermediate-time survivors from the analysis. Furthermore, the separation between groups were clear for the MRI and metabolomic parameters presented, exemplified by all MRI volume measures for long-time survivors in scans 4 and 5 had smaller volumes than the median of the short-time survivor group.

From this study, it is unclear to what extent PET with the use of 18F-FLT-tracer contributed to increased knowledge and further studies with different tracers are needed. We believe that the reported differences in blood metabolomics and tumor volume in contrast-enhanced MRI between long- and short-time survivors and changes during treatment are promising and that these parameters may be valuable candidates for future clinical decision aids. We also hope that the metabolic differences between groups have a biological significance and may be utilized to better understand the biology of glioblastoma, and possibly be developed into a diagnostic tool.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study where blood and imaging with 18F-FLT-PET/MRI are sampled sequentially from the timepoint before surgery, after surgery, and during concomitant radio-chemotherapy from patients with glioblastoma. We find the results interesting and although the most crucial would be to find better treatment and more treatment options for this group of patients, the strive to find better diagnostic methods, earlier detection of treatment outcomes, and more accurate prognostication hopefully will encourage more research in this field.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all individuals participating in the Uppsala-Umeå Comprehensive Cancer Consortium (www.u-can.uu.se) and especially A Tommy Bergenheim for surgery samples from the beginning of the project and Thomas Brännström for neuropathology review. We thank the Biobank Sweden and the Region Västerbotten for providing data and samples. We are grateful to Matilda Rentoft, Mikael Kimdahl and Ulrika Andersson at the Translational Research Centre in Umeå for invaluable help with the blood samples sent to Metabolon. Thanks also to Björn Tavelin for help with statistics. Part of this work has been presented at the European Association of Neuro-Oncology, 2023 in Rotterdam as a poster.

Contributor Information

Jan Axelsson, Department of Diagnostics and Interventions, Radiation Physics, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Benny Björkblom, Department of Chemistry, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Thomas Asklund, Department of Diagnostics and Interventions, Oncology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Jens Brandel, Department of Diagnostics and Interventions, Diagnostic Radiology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Svante Larhed, Department of Diagnostics and Interventions, Oncology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Gabriela M Ringmar, Department of Diagnostics and Interventions, Oncology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Karolina Hedman, Department of Surgical Sciences, Molecular Imaging and Medical Physics, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden; Department of Diagnostics and Interventions, Radiation Physics, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Katrine Riklund, Department of Diagnostics and Interventions, Diagnostic Radiology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Rickard L Sjöberg, Department of Clinical Sciences, Neurosciences, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Maria Sandström, Department of Diagnostics and Interventions, Oncology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Funding

The Swedish Cancer Society (CAN 2013/701 to T.A), Sjöberg Foundation (2020-01-07-08 to B.B., M.S. and R.L.S) Umeå University Hospital grant (RV-492791, RV-764931, RV-866041 to M.S), Cancer Research Foundation in Northern Sweden (LP 18-2185, LP 20-2249 to M.S).

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Tissue collection and storing: T.A., M.S., and R.L.S.; surgical procedure: R.L.S.; metabolite extraction and mass spectrometric analysis: B.B.; methodology: B.B., J.A., M.S., and K.R.; statistical analysis: J.A., B.B., and M.S.; tumor delineation: J.A., M.S., J.B., G.M.R., K.H., and S.L.; clinical analysis and characterization: M.S., J.A., J.B., G.M.R., S.L., and K.H.; data interpretation: M.S., J.A., K.H., G.M.R., and B.B.; writing original draft: M.S., J.A., and B.B. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Due to GDPR and patient sensitive data we share data upon request with specific data sharing agreements.

References

- 1. Schaff L, Mellinghoff I.. Glioblastoma and other primary brain malignancies in adults: A review. JAMA. 2023;329(7):574–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eriksson M, Kahari J, Vestman A, et al. Improved treatment of glioblastoma - changes in survival over two decades at a single regional Centre. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(3):334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wen PY, Weller M, Lee EQ, et al. Glioblastoma in adults: A Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and European Society of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(8):1073–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, et al. Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2306–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Guidlines for tumours in the brain, spinal cord and its membranes, 2023. https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/diagnoser/hjarna/vardprogram/ [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glimelius B, Melin B, Enblad G, et al. U-CAN: A prospective longitudinal collection of biomaterials and clinical information from adult cancer patients in Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(2):187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thie JA. Understanding the standardized uptake value, its methods, and implications for usage. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(9):1431–1434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Björkblom B, Wibom C, Eriksson M, et al. Distinct metabolic hallmarks of WHO classified adult glioma subtypes. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24(9):1454–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Forsgren E, Björkblom B, Trygg J, Jonsson P.. OPLS-based multiclass classification and data-driven inter-class relationship discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.4c01799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weller M, van den Bent M, Preusser M, et al. EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(3):170–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arvanitis CD, Ferraro GB, Jain RK.. The blood-brain barrier and blood-tumour barrier in brain tumours and metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(1):26–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitamura K, Yamamoto Y, Kudomi N, et al. Intratumoral heterogeneity of (18)F-FLT uptake predicts proliferation and survival in patients with newly diagnosed gliomas. Ann Nucl Med. 2017;31(1):46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Niyazi M, Andratschke N, Bendszus M, et al. ESTRO-EANO guideline on target delineation and radiotherapy details for glioblastoma. Radiother Oncol. 2023;184:109663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, et al. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2192–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yoon RG, Kim HS, Paik W, et al. Different diagnostic values of imaging parameters to predict pseudoprogression in glioblastoma subgroups stratified by MGMT promoter methylation. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(1):255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tserng KY, Jin SJ.. Metabolic origin of urinary 3-hydroxy dicarboxylic acids. Biochemistry. 1991;30(9):2508–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ruiz-Sala P, Pena-Quintana L.. Biochemical markers for the diagnosis of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guerra IMS, Ferreira HB, Melo T, et al. Mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation disorders: From disease to lipidomic studies-a critical review. Int J Mol Sci . 2022;23(22):13933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang SF, Tseng LM, Lee HC.. Role of mitochondrial alterations in human cancer progression and cancer immunity. J Biomed Sci. 2023;30(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Blitterswijk WJ, van der Luit AH, Veldman RJ, Verheij M, Borst JC.. second messenger or modulator of membrane structure and dynamics? Biochem J. 2003;369(Pt 2):199–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Won JS, Singh I.. Sphingolipid signaling and redox regulation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40(11):1875–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang T, de Waard AA, Wuhrer M, Spaapen RM.. The role of glycosphingolipids in immune cell functions. Front Immunol. 2019;10:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ponnusamy S, Meyers-Needham M, Senkal CE, et al. Sphingolipids and cancer: Ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate in the regulation of cell death and drug resistance. Future Oncol. 2010;6(10):1603–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Siskind LJ. Mitochondrial ceramide and the induction of apoptosis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37(3):143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shalaby YM, Al Aidaros A, Valappil A, Ali BR, Akawi N.. Role of ceramides in the molecular pathogenesis and potential therapeutic strategies of cardiometabolic diseases: what we know so far. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:816301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Longo N, Frigeni M, Pasquali M.. Carnitine transport and fatty acid oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(10):2422–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taniguchi M, Okazaki T.. Role of ceramide/sphingomyelin (SM) balance regulated through “SM cycle” in cancer. Cell Signal. 2021;87:110119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fernandez-Garcia P, Rossello CA, Rodriguez-Lorca R, et al. The opposing contribution of SMS1 and SMS2 to glioma progression and their value in the therapeutic response to 2OHOA. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(1):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chakraborty M, Jiang XC.. Sphingomyelin and its role in cellular signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;991:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee M, Lee SY, Bae YS.. Functional roles of sphingolipids in immunity and their implication in disease. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55(6):1110–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lodi A, Pandey R, Chiou J, et al. Circulating metabolites associated with tumor hypoxia and early response to treatment in bevacizumab-refractory glioblastoma after combined bevacizumab and evofosfamide. Front Oncol. 2022;12:900082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to GDPR and patient sensitive data we share data upon request with specific data sharing agreements.