Abstract

Background: Female patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) have an increased risk of breast cancer (BrCa), and surveillance is recommended. However, clinicopathological features of their tumors and prognosis are lacking. To facilitate more precise future guideline development, we evaluated these data. Methods: We conducted an international survey for InSiGHT members to collect retrospective data on PJS patients with diagnosed breast cancer. Results: We received 23 responses, including three centers with data on BrCa patients. All reported BrCa patients were female. In total, the cohort comprised 27 patients with 34 BrCa (five bilateral synchronous, one bilateral metachronous, and one metachronous unilateral tumours). The median age at first cancer diagnosis was 45 years (range 26–67). Most cancers were ductal carcinoma, either invasive (13) or in situ (DCIS; 19). TNM staging for invasive cancer was available in thirteen cases, of which nine were T1N0M0. Among tumors with histological reports, 14/15 were oestrogen receptor positive, 8/15 were progesterone receptor positive, and 4/15 were HER2 positive. There were no triple negative breast cancers. Twenty-five patients had follow-up data, comprising 229 patient years. Eleven patients had died of any cause during follow-up. Survival at 5 years was 73%. Conclusion: Overall, breast cancers that occur in this PJS population seem to have favorable characteristics and prognosis. These data will help inform discussions about risk management in patients with PJS. Further research is needed to better understand lifetime risk, the optimal surveillance modality and its outcomes.

Keywords: Genetic cancer predisposition, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Breast cancer, Hereditary cancer syndromes, Germline pathogenic variants

Introduction

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is a rare autosomal dominant inherited disorder, caused by a constitutional pathogenic variant (PV) in the tumour suppressor gene STK11 (also known as LKB1) [1, 2] and clinically characterized by the development of Peutz-Jegher type hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract, mucocutaneous pigmentation [3–5] The estimated prevalence of PJS is most consistently reported to be somewhere between 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000, with a wider range of estimates from some studies [5–7]. Patients with PJS have an increased cancer risk as well as an increased risk of cancer-related mortality [8–16]. The absolute risk of developing cancer among PJS patients is difficult to estimate given the rarity of this condition and the nature of historical studies which are likely to be subject to significant ascertainment bias [5, 17]. Women with PJS are reported to have a 19–54% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer [8, 9]. This wide variation in quoted risk probably reflects ascertainment bias and small number of absolute cases in the available data (ranging from 1 to 17 reported breast cancer cases per previously published case series) [8–14, 16, 18]. Nonetheless, the breast cancer risk in women with PJS appears consistently elevated compared to general female population risk between 12 and 14% observed in Western countries [19–21]. Due to these striking numbers, the fifth edition of the World Health Organization classification of tumours of the breast (2019) now includes PJS as a genetic tumour syndrome of breast cancer [22], in line with other PVs at high or moderate risk for breast cancer, including established PVs in BRCA1, BRCA2, CDH1, PALB2, ATM, CHEK2, PTEN, and TP53 [23, 24].

Because of their estimated high lifetime risk of breast cancer [17, 25–27], women with PJS are recommended to start surveillance with annual breast MRI and clinical breast exams every 6–12 months by age 25 or 30 [17, 27, 28]. As the breast tumor biology, clinical characteristics and prognosis among women with PJS have not been characterized in the same way as breast cancers in persons with other high risk PVs [29], routine risk reducing mastectomy is currently not recommended [17]. A few case reports have documented the occurrence of both synchronous and metachronous bilateral breast cancers in women with PJS [18, 30–33]. A few recent case reports and case series have reported on histological subtypes of the breast tumors occurring in women with PJS, and most have reported ER + tumors [34, 35], though one has reported a triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) that demonstrated loss of the normal homologous STK11 allele in the tumor [36]. Overall, information about presentation and prognosis of breast cancer in PJS is limited, and this information is essential to inform counseling and to help future development of surveillance and treatment guidelines.

To begin to address this gap, we have conducted an international survey to provide a descriptive epidemiologic assessment of the clinical and pathological characteristics of breast cancers among PJS patients.

Methods

We performed a retrospective survey to assess information about the histological classification, receptor status, and clinical care of breast tumors among PJS patients. PJS patients were eligible for inclusion if they had histologically confirmed diagnoses of breast tumor (invasive cancers and/or ductal carcinoma in situ).

Study populations

The International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumors (InSiGHT) is a scientific organization for researchers, clinicians and other healthcare professionals focused on research and clinical care into hereditary conditions that predispose to gastrointestinal tumors, including PJS [37, 38]. We sent the survey to InSiGHT members to enquire if they had had a case of PJS and breast cancer. For those that did, we collected retrospective information about breast cancers that had occurred in their PJS populations.

Prior to distributing the survey, local institutional Research and Development approval was received and each center contributing data obtained local institutional approval to share anonymized data.

Data visualization and analysis

Survey responses and anonymized data were collated and information about patient follow-up and confirmation of vital status was checked by clinicians at participating sites in the third quarter of 2023. Descriptive statistics and data visualization of the survey results, including a Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival, were generated using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version: 28.0.1.0 (Amronk, NY: IBM Corp). Due to the small numbers of cases and considerable missing data, we did not perform statistical tests to compare the data across strata, and report only descriptive statistics here. Given the retrospective nature and lack of coordinated, prospectively collated surveillance outcomes, this study is not intended to address cumulative risk of BrCa development in this population.

Results

All registered InSiGHT members were contacted and 23 responses were received. Three centers had cases of PJS and breast cancer and one center had detailed breast surveillance data but no cases of breast cancer [15]. All cases were either confirmed carriers or obligate carriers of likely pathogenic or pathogenic germline variant in STK11 (Table 1).There were 34 breast cancers in 27 patients (including five bilateral synchronous tumors, one case with bilateral metachronous tumors, and one metachronous unilateral tumor). Two additional patients were diagnosed with benign breast lesions, and they were excluded from further analysis. All reported breast cancer patients were female (Table 2). The median age at first cancer diagnosis was 45 years (range 26–67). About one third of DCIS tumors and invasive ductal carcinoma tumors were diagnosed in women age < 40 years.

Table 1.

Genetic information of Peutz-Jeghers patients who had breast cancer diagnoses (N = 27 patients)

| Patient number | STK11 variant |

|---|---|

| 1 | c.370 A > T |

| 2 | c. 752 G > A |

| 3 | Not tested |

| 4 | c.735-1 G > A* |

| 5 | c.Del Ex 1 |

| 6 | c.921 − 12 G > A* |

| 7 | c.921 − 12 G > A |

| 8 | c.991 dupC |

| 9 | c.197 dupT |

| 10 | c.290 + 1 G > C |

| 11 | c.908 T > A |

| 12 | c.664 delA |

| 13 | c.396 C > A |

| 14 | c.368 delA |

| 15 | c.843 delG |

| 16 | c.843 delG |

| 17 | c.454 C > T |

| 18 | c.454 C > T |

| 19 | c.454 C > T |

| 21 | c.815–816 insA |

| 22 | c.Ex7 R304W |

| 23 | c.Del ex 3–4 |

| 24 | c.Del ex 3–10 |

| 25 | c.256 C > T |

| 26 | c.250 A > T |

| 27 | c.232 A > T |

| 28 | c.1-? 464 + del |

*mutation detected in first degree relative

Table 2.

Characteristics of Peutz-Jeghers patients who had breast cancer diagnoses (N = 27 patients)

| Female | 27 (100%) |

| Age at first breast cancer diagnosis, years | 45 [26–67] |

| Death, all cause | 9 (33.3%) |

| Follow-up time, years* | 9.5 [0–29] |

Values reported are absolute numbers(% of the population with information available) or median[interquartile range]

* Follow-up time was missing for 5 patients

The reported tumors were diagnosed between 1944 and 2020. Given the historical nature of this survey, several cases predate breast cancer surveillance efforts in their countries. Among those who did take part in surveillance, we do not have detailed, country-specific information about the recommendations for modality or frequency of surveillance at the time of diagnosis for the individual cases; guidelines have been updated during the retrospective study period. Information about (prior) breast cancer surveillance or tumor detection were available for 14 patients, and the results are presented in Table 3. Among the 9 patients with information about tumor detection, 5 tumors were reported to be detected at surveillance, including 2 tumors detected at first surveillance, and 4 tumors were detected as a palpable mass after a previous negative mammogram. We caution against drawing conclusions about surveillance based on these data since the information was incomplete and inconsistently reported.

Table 3.

Surveillance and tumor detection

| Patient number |

Surveillance-detected tumor | Surveillance history | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | No prior surveillance | Tumor detected at first surveillance |

| 2 | 0 | Prior surveillance | Previous mammogram was 7 months earlier (BI-RADS 2) |

| 3 | 0 | No prior surveillance | Tumor detected as palpable mass |

| 4 | 1 | Yearly surveillance | |

| 5 | 0 | Prior surveillance | Tumor detected as palpable mass; Last surveillance was 6 years earlier |

| 6 | 1 | Prior surveillance | Previous mammogram was 3 years earlier |

| 7 | 1 | No prior surveillance | Tumor detected at first surveillance |

| 8 | 0 | Tumor was not surveillance-detected, and we have no information about prior surveillance | |

| 9 | 0 | Prior surveillance | Tumor detected as palpable mass; Previous mammogram was 7 months earlier (BI-RADS 2) |

| 10 | 1 | Prior surveillance | Previous mammogram was 14 months earlier |

| 11 | 0 | Prior surveillance | Tumor detected as palpable mass; Last surveillance was 8 months earlier |

| 13 | 1 | Tumor was surveillance-detected, but we have no information about prior surveillance | |

| 27 | Yearly surveillance | Patient had prior surveillance (mammogram and MRI), but we have no information if tumor was surveillance-detected | |

| 28 | Yearly surveillance | Patient had prior surveillance (ultrasound and MRI), but we have no information if tumor was surveillance-detected |

Tumor characteristics

An overview of the tumor characteristics is presented in Table 4. Half of the cancers were ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS, N = 17) followed by invasive ductal carcinoma (ICD, N = 14), intracystic papillary carcinoma (N = 1), invasive mixed (N = 1), and unspecified invasive tumor (N = 1). For three DCIS, information on grade was missing (17.6%). Of the DCIS with grade available (N = 11), six DCIS (42.9%) were grade 3, and seven DCIS (50%) were grade 2 at the time of diagnosis. Among the invasive tumors with TNM staging available (N = 14), nine had tumors with stage T1N0M0, two had T2N0M0, and three were lymph node positive. No patient presented with metastatic disease. Among the invasive tumors with information on receptor status available(N = 11/17), all eleven were ER+, four were PR + and three were HER+. Additionally, among the four DCIS with receptor status available, three were ER+, four were PR+, and one was HER2+. There were no triple negative breast cancers.

Table 4.

Breast tumor characteristics at the time of diagnosis

| Patient | Tumor | Breast | Age | Grade | TNM | ER+ | PR+ | HER+ | Surgery | Chemo | Radiation | Endocrine | Tumor type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 34 | 2 | T0N0M0 | Lumpectomy | 0 | 1 | DCIS | |||||

| 8 | 1 | 61 | 2 | T0N0M0 | DCIS | ||||||||

| 11 | 1 | 26 | 3 | T0N0M0 | Bilateral ablation | 1 | 0 | 1 | DCIS | ||||

| 12 | 1 | 33 | 3 | T0N0M0 | DCIS | ||||||||

| 13 | 1 | 47 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Bilateral mastectomy | DCIS | ||||||

| 14 | 1 | L | 61 | 3 | T0N0M0 | Mastectomy | DCIS | ||||||

| 14 | 2 | R | 61 | T0N0M0 | Mastectomy | DCIS | |||||||

| 15 | 1 | L | 34 | 2 | T0N0M0 | Mastectomy | DCIS | ||||||

| 17 | 1 | R | 36 | 3 | T0N0M0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Bilateral mastectomy | DCIS | |||

| 17 | 1 | L | 36 | 2 | T0N0M0 | 0 | 0 | Equiv | DCIS | ||||

| 22 | 1 | R | 62 | 2 | T0N0M0 | Mastectomy | DCIS | ||||||

| 23 | 1 | R | 45 | 2 | T0N0M0 | Lumpectomy | DCIS | ||||||

| 24 | 1 | R | 41 | DCIS | |||||||||

| 24 | 1 | L | 41 | DCIS | |||||||||

| 26 | 1 | R | 49 | 3 | T0N0M0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Mastectomy | DCIS | |||

| 26 | 1 | L | 49 | 1 | T0N0M0 | Lumpectomy | DCIS | ||||||

| 27 | 1 | L | 45 | 2 | T0N0M0 | Bilateral mastectomy | DCIS | ||||||

| 28 | 1 | R | 28 | 3 | T0N0M0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Bilateral mastectomy | DCIS | |||

| 2 | 1 | 50 | T1N0M0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Lumpectomy | 1 | 1 | 1 | IDC | ||

| 3 | 1 | 34 | 3 | T2N0M0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | IDC | |||||

| 5 | 1 | 49 | T1N0M0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Lumpectomy | 0 | 1 | 0 | IDC | ||

| 6 | 1 | 53 | T1N0M0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Lumpectomy | 0 | 1 | 0 | IDC | ||

| 7 | 1 | 61 | T1N0M0 | IDC | |||||||||

| 9 | 1 | 47 | Lumpectomy + ablation | 0 | 0 | 0 | IDC | ||||||

| 10 | 1 | 41 | T1N0M0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Ablation | 1 | 0 | 0 | IDC | ||

| 11 | 1 | 26 | T1N1M0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Bilateral ablation | 1 | 0 | 1 | IDC | ||

| 14 | 51 | IDC | |||||||||||

| 16 | 1 | 36 | TxN2 | Mastectomy | 0 | 1 | IDC | ||||||

| 18 | 1 | R | 35 | T1N0M0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Bilateral Mastectomy | 1 | 1 | 1 | IDC | |

| 18 | 1 | L | 35 | T2N1M0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | IDC | |||||

| 19 | 1 | R | 67 | T1N0M0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Lumpectomy | 1 | 0 | 1 | IDC | |

| 25 | 1 | R | 31 | T1N0M0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Bilateral mastectomy | 1 | 1 | 1 | IDC | |

| 21 | 1 | R | 46 | T1N0M0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Lumpectomy and bilateral mammoplasty | 0 | 1 | 1 | Invasive mixed | |

| 15 | 2 | L | 44 | Left lumpectomy and right mastectomy | Invasive papillary | ||||||||

| 4 | 1 | 55 | T2N0M0 | Lumpectomy | 1 | 1 | Unspecified invasive |

In the columns ER+, PR+, HER2, Chemo, Radiation, and Endocrine, a 1 denotes “yes”, and a 0 denotes “no”. All empty cells denote the data is not known. DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; IDC: invasive ductal carcinoma

Treatment

Most patients were treated with some form of surgery for their first breast tumor diagnosis. Six patients underwent bilateral mastectomy, while five patients underwent a unilateral mastectomy, of whom two patients were later treated for a second breast tumor with mastectomy of the other breast. Ten women were treated with lumpectomy. Among the invasive tumors with information about additional treatment available (N = 15/17), eight women were treated with chemotherapy, nine women were treated with radiotherapy, and seven women were treated with endocrine therapy (Table 3).

Follow-up

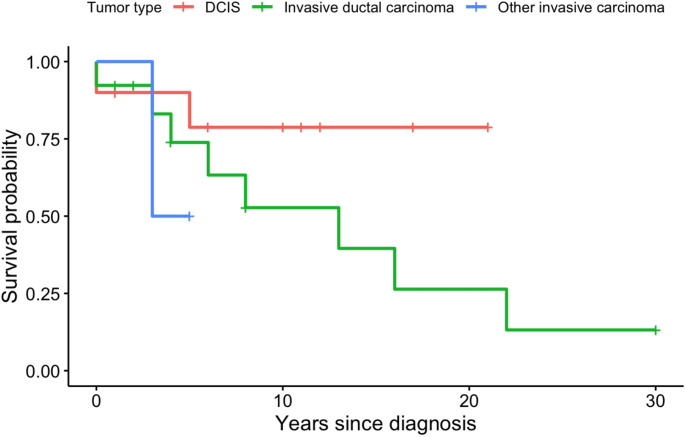

Twenty-five patients had information on follow-up time available, with a total of 229 person-years of follow-up. Eleven patients are reported to have passed away during follow-up. Among those who died, median age of death was 56 years (range 39–75). Six of the eleven women passed away within 5 years of the breast cancer diagnosis (5-year cumulative survival 73.0%), though we do not have information on cause of death to confirm that these were cancer related. For two patients, follow-up time information was missing, but among the patients who were still known to be alive at the time of the survey (N = 14), there was a median of nine years follow-up (range 1–30 years) since the diagnosis of their first tumor. When stratified by histological subtype (i.e. DCIS, invasive ductal carcinoma, or other invasive carcinoma), we see that DCIS patients seemingly had no deaths reported after 5 years, and 50% of the DCIS patients had ≥ 10 years of follow-up (Fig. 1). For patients with invasive ductal carcinoma, the median overall survival time was estimated to be 13 years after diagnosis of the first tumor, though the small sample size leads to uncertainty in this estimate (95% CI 3.5–22.5 years). Of the other invasive cancers diagnosed, the patient with an unknown invasive breast carcinoma passed away three years after her diagnosis, while the other patient was censored after five years. Of note, these survival curves do not account for competing risks, such as new primary diagnoses, or other cancer diagnoses, nor do they account for year of diagnosis, staging and treatment of the primary tumor.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve denoting overall survival by first tumor histology

Discussion

This is the first study evaluating the breast tumor characteristics in an internationalpopulation of PJS patients. All breast tumors reported in our survey occurred in women. Half of the tumors reported were DCIS, and among the cases with information about hormone receptor status, we had no reports of triple negative breast cancers.

In the absence of precise risk characterization, women with known STK11 PVs and likely PVs [39] are being treated equivalently to BRCA1 and BRCA2 PGV carriers. Similar to BRCA1 and BRCA2 PV carriers [40], breast cancers do occur at a young age in women with PJS. Previous studies estimate the median age of breast cancer diagnosis in PJS to be 37 years [29]. In our survey patient population, the median age at first cancer diagnosis was 45 years old with a range from 26 to 67 years old. Several patients were diagnosed with synchronous or metachronous bilateral breast tumors, and two women experienced recurrent tumors during their follow-up. This is consistent with numerous other case reports of bilateral breast tumors among women PJS [18, 30–33], and reinforces the overall increased risk of developing breast tumors in this population. There were no cases of men with breast cancer, confirming data in previous case studies [8, 9, 11, 34, 41].

Compared to women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 PVs, our data indicate that women with PJS have more favorable tumor characteristics. One clear comparative indication is the presence of triple negative breast cancers (TNBC) (i.e. tumors that do not have receptors for estrogen or progesterone and do not produce HER2 protein), which carry the worse prognosis among breast cancer subtypes [42, 43]. TNBCs make up 10–20% of all breast cancer diagnoses. Women with BRCA1, and to a lesser extent BRCA2 PVs, have an even higher risk of TNBCs compared to the general population [42, 44, 45]. We are aware of one case study in the literature in which a woman with a germline PV in STK11 was diagnosed with a TNBC, in which the tumor showed loss of homologous normal allele [36]. In this study sample, we observed no TNBC’s in PJS patients. All invasive tumors in our study for which immunohistochemistry was available were hormone receptor positive, in line with several previous case reports of breast tumors in women with PV in STK11 [34, 35]. Due to the limited sample size, this result should be interpreted with caution.

Notably, half of the tumors diagnosed in this study population (50%) were DCIS. Actually, DCIS represent a pre-cancer that is not invasive at the time of detection, and usually DCIS have a very good prognosis [46]. About half of high-grade DCIS can progress to invasive breast cancer within five to ten years, if left untreated [47], and about 5% of treated DCIS will recur as an invasive breast tumor [48–51]. Current evidence suggests that low-grade DCIS tumors take decades to progress to invasive tumors, if they ever do [47, 52, 53]. In general population, DCIS make up between 13 and 25% of all screen-detected breast cancers, and DCIS is equally as prevalent in patients who carry BRCA PVs as in high familial-risk women who are non-carriers, but occurs at an earlier age [54]. The increased incidence of DCIS diagnosis after the commencement of population-based screening has fueled discussions about overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS in women with average lifetime risk of breast cancer [46, 55, 56], and at least one ongoing trial in the general population is specifically studying active surveillance without treatment for women with low grade DCIS [57]. For now, the absence of informative and effective risk stratification precludes a more tailored approach for DCIS, particularly in women with a lifetime high risk of breast cancer.

The overall favorable tumor characteristics among our study population indicate a need for reflection on current clinical care and counseling for women with PJS. We note some differences in standard of care across the countries included in this survey. In the UK and Australia, women with PJS are still counseled on risk reducing bilateral mastectomy, despite recent guidelines that advise against this [17, 28, 58]. In the Netherlands, prophylactic mastectomy is generally not advocated to women with PJS in the absence of clear evidence of the clinical benefit [17]. This survey indicates that the tumors occurring in women with PJS seem to be slower growing, less likely to recur, and have better prognosis than tumors that are reported in other high-risk breast cancer groups, like BRCA1 and BRCA2 PV carriers. Based on this, we consider that risk reducing bilateral mastectomy may be overtreatment in this group and should not be recommended routinely.

Given the receptor status of the tumors, patients may seek additional advice on exogenous hormone use (e.g. oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy(HRT)). Based on the limited literature from women with high familial risk or PV in BRCA1/2, exogenous hormones are not contraindicated in unaffected women, but patients with previous breast cancer (especially hormone receptor positive cancer) are advised against exogenous hormone use [59–63]. For the PJS population, a potential increased risk of cervical cancer is also relevant for HRT use [5, 27, 64, 65]. Numerous international guidelines suggest endocrine therapy for breast cancer prevention in women at high risk [66–69]. All of the tumors that were tested for receptor status in our survey were ER+, suggesting preventative selective estrogen receptor modulators may be effective breast cancer prevention among PJS patients, as has been demonstrated among other patients at high risk for ER + tumors [69–71]. However, our limited understanding of the pathophysiology of breast cancer among PJS, the generally bad acceptance and adherence to chemoprevention [72, 73], and the potential for SERM to increase risk of other cancers (e.g. endometrial cancer) [74, 75], it is difficult to determine the net benefits and harms of chemoprevention in this patient group at this moment [76, 77].

Information about (prior) breast cancer surveillance was collected as part of the survey, but given the historical nature of this survey and the large timespan of the diagnoses (1944–2020), characterizing the role of surveillance is difficult. Several cases occurred prior to commencement of any imaging-based surveillance, and recommendations regarding starting age, modality (i.e. clinical breast exams, mammograms, and/or breast MRI) and frequency of surveillance for PJS patients (and the general public) has differed across countries and across time. From the survey responses, only five of nine tumors were surveillance detected from mammography, and four tumors presented as a palpable mass after a previously negative mammogram. The current European PJS surveillance guideline recommends utilizing contrast-enhanced breast MRI starting from age 25–30, and then some combination of annual mammography, tomosynthesis, or ultrasound in combination with breast-MRI annually up to and including age 70 years [17]. We do not have any reported information about what surveillance recommendations the patients in our survey received and only limited information about surveillance with modalities other than mammography. To date, there are no prospective data comparing the clinical efficacy and utility of various (combinations of) imaging modalities in PJS. Most of the tumors identified in this survey appear to be prognostically favorable. As such, future studies should consider the positive and negative predictive values, cost, and harm-benefit ratios of mammography, tomosynthesis and MRI-based surveillance among PJS patients and aim to calibrate the starting age and frequency of surveillance to best suit this population.

This study represents the first international survey of clinical pathological features of breast cancer among PJS patients. Though our survey includes a small sample size and is based on retrospective data collection, it provides a first profile of breast cancer in this patient population. Anecdotally, in the process of collecting this survey data, we noted that at both a national and institutional level, many InSIGHT members reported that there was no registry for patients with PJS to identify cases of breast cancer or for co-ordination of patient care more generally. In the absence of such registries, we cannot rule out that our reported cases are not subject to ascertainment bias. The small number of reported breast cancer cases may also indicate that ascertainment bias in historic data sets has led to an overestimation of breast cancer risk in this population.

To achieve an accurate characterization of breast cancer risk in PJS, we need an accurate count of all women with PJS, but we also need more precise capture of how many women with PJS undergo risk reducing bilateral mastectomy, capture other incident cancers, and capture of cause-specific mortality. Further, additional evidence is needed to determine if non-carrier family members of patients with PJS also experience an increased risk of breast cancer or other cancers due to family history [78–80]. Most importantly, there is a need for continued and reinforced collaboration between clinical genetics and oncology departments to follow patients from genetic diagnosis through cancer care in order to accurately characterize the clinical course for these patients and ensure optimal surveillance and care. Next steps should determine whether counseling and surveillance guidelines for breast cancer should be updated for women with PJS and ideally unified across countries.

Author contributions

E.L. performed the analysis, prepared the tables and figures, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. A.W. and A.L. conceived the project, provided supervision, and interpreted data. A.W., M.B., F.R.R., A.M.J., A.G., M.v.L., S.E.K, E.D., M.C.W.S., J.G.K., V.Z. F.M., and A.L. contributed to data collection, data cleaning, and clinical interpretation. All authors reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the final version of the writing.

Data availability

The available anonymized clinical data is provided within the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hemminki A, Tomlinson I, Markie D, Jarvinen H, Sistonen P, Bjorkqvist AM et al (1997) Localization of a susceptibility locus for Peutz-Jeghers syndrome to 19p using comparative genomic hybridization and targeted linkage analysis. Nat Genet 15(1):87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemminki A, Markie D, Tomlinson I, Avizienyte E, Roth S, Loukola A et al (1998) A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Nature 391(6663):184–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peutz JLA (1921) Over Een Zeer Merkwaardige, gecombineerde Familiaire polyposis Van de Slijmliezen Van Den tractus intestinalis Met die Van de Neuskeelholte En Gepaard Met eigenaardige pigmentaties Van huid-en Slijmvliezen. Nederl Maandschr Geneesk 10:134–146 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeghers H, Mc KV, Katz KH (1949) Generalized intestinal polyposis and melanin spots of the oral mucosa, lips and digits; a syndrome of diagnostic significance. N Engl J Med 241(26):1031–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, Moslein G, Alonso A, Aretz S et al (2010) Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut 59(7):975–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jelsig AM, Qvist N, Sunde L, Brusgaard K, Hansen T, Wikman FP et al (2016) Disease pattern in Danish patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis 31(5):997–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Utsunomiya J, Gocho H, Miyanaga T, Hamaguchi E, Kashimure A (1975) Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: its natural course and management. Johns Hopkins Med J 136(2):71–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, Goodman SN, Petersen GM, Booker SV et al (2000) Very high risk of cancer in Familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 119(6):1447–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hearle N, Schumacher V, Menko FH, Olschwang S, Boardman LA, Gille JJ et al (2006) Frequency and spectrum of cancers in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Cancer Res 12(10):3209–3215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehenni H, Resta N, Park JG, Miyaki M, Guanti G, Costanza MC (2006) Cancer risks in LKB1 germline mutation carriers. Gut 55(7):984–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Lier MG, Westerman AM, Wagner A, Looman CW, Wilson JH, de Rooij FW et al (2011) High cancer risk and increased mortality in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gut 60(2):141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resta N, Pierannunzio D, Lenato GM, Stella A, Capocaccia R, Bagnulo R et al (2013) Cancer risk associated with STK11/LKB1 germline mutations in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome patients: results of an Italian multicenter study. Dig Liver Dis 45(7):606–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishida H, Tajima Y, Gonda T, Kumamoto K, Ishibashi K, Iwama T (2016) Update on our investigation of malignant tumors associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in Japan. Surg Today 46(11):1231–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen HY, Jin XW, Li BR, Zhu M, Li J, Mao GP et al (2017) Cancer risk in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: A retrospective cohort study of 336 cases. Tumour Biol 39(6):1010428317705131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jelsig AM, Wullum L, Kuhlmann TP, Ousager LB, Burisch J, Karstensen JG (2023) Risk of Cancer and mortality in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and juvenile polyposis syndrome-A nationwide cohort study with matched controls. Gastroenterology 165(6):1565–1567e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SH, Kim ER, Park JJ, Kim ES, Goong HJ, Kim KO et al (2023) Cancer risk in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in Korea: a retrospective multi-center study. Korean J Intern Med 38(2):176–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner A, Aretz S, Auranen A, Bruno MJ, Cavestro GM, Crosbie EJ et al (2021) The management of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: European hereditary tumour group (EHTG) guideline. J Clin Med 10(3):473–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Fostira F, Mollaki V, Lypas G, Alexandrakis G, Christianakis E, Tzouvala M et al (2018) Genetic analysis and clinical description of Greek patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: creation of a National registry. Cancer Genet 220:19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Waal D, Verbeek AL, den Heeten GJ, Ripping TM, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Broeders MJ (2015) Breast cancer diagnosis and death in the Netherlands: a changing burden. Eur J Public Health 25(2):320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancer Statistics SEER, Review 1975–2017, National Cancer Institute [Internet]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/

- 21.Lifetime risk estimates calculated by the Cancer Intelligence Team at Cancer Research UK [Internet] (2023) Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer/risk-factors#ref-1

- 22.Board WCoTE (2019) Breast tumours, 5th edn. IARC, Lyon [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrucelli NDMB, Pal T BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle: GeneReviews® [Internet]; 1998 [updated 2023 Sep 21. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1247/

- 24.Wu M, Krishnamurth K, Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL):: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 [updated 2023 Jul 17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535357/

- 25.Rousset-Jablonski C, Gompel A (2017) Screening for Familial cancer risk: focus on breast cancer. Maturitas 105:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achatz MI, Porter CC, Brugieres L, Druker H, Frebourg T, Foulkes WD et al (2017) Cancer screening recommendations and clinical management of inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer syndromes in childhood. Clin Cancer Res 23(13):e107–e14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klimkowski S, Ibrahim M, Ibarra Rovira JJ, Elshikh M, Javadi S, Klekers AR et al (2021) Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and the role of imaging: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and associated cancers. Cancers (Basel) 13(20):5121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Government N (2010) STK11 (Peutz-Jeghers) – risk management: eviQ, Cancer Institute NSW; [updated 5 July 2022. Available from: https://www.eviq.org.au/cancer-genetics/adult/risk-management/395-stk11-peutz-jeghers-risk-management#cancer-tumour-risk-management-guidelines

- 29.Sokolova A, Johnstone KJ, McCart Reed AE, Simpson PT, Lakhani SR (2023) Hereditary breast cancer: syndromes, tumour pathology and molecular testing. Histopathology 82(1):70–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin-Odegard B, Svane S (1994) Peutz-Jeghers syndrome associated with bilateral synchronous breast carcinoma in a 30-year-old woman. Eur J Surg 160(9):511–512 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehur PA, Madarnas P, Devroede G, Perey BJ, Menard DB, Hamade N (1984) Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Association of duodenal and bilateral breast cancers in the same patient. Dig Dis Sci 29(2):178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trau H, Schewach-Millet M, Fisher BK, Tsur H (1982) Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and bilateral breast carcinoma. Cancer 50(4):788–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riley E, Swift M (1980) A family with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and bilateral breast cancer. Cancer 46(4):815–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipsa A, Kowtal P, Sarin R (2019) Novel germline STK11 variants and breast cancer phenotype identified in an Indian cohort of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 28(11):1885–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kilic-Okman T, Yardim T, Gucer F, Altaner S, Yuce MA (2008) Breast cancer, ovarian gonadoblastoma and cervical cancer in a patient with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 278(1):75–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakanishi C, Yamaguchi T, Iijima T, Saji S, Toi M, Mori T et al (2004) Germline mutation of the LKB1/STK11 gene with loss of the normal allele in an aggressive breast cancer of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Oncology 67(5–6):476–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International society for gastrointestinal hereditary tumours-InSiGHT (2019) Fam Cancer 18(Suppl 1):1–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch PM (2008) Standards of care in diagnosis and testing for hereditary colon cancer. Fam Cancer 7(1):65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chow E, Meldrum CJ, Crooks R, Macrae F, Spigelman AD, Scott RJ (2006) An updated mutation spectrum in an Australian series of PJS patients provides further evidence for only one gene locus. Clin Genet 70(5):409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, Phillips KA, Mooij TM, Roos-Blom MJ et al (2017) Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA 317(23):2402–2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez Lagos FA, Sorli Guerola JV, Romero Martinez IM, Codoner Franch P (2020) Register and clinical follow-up of patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in Valencia registro y Seguimiento clinico de Pacientes Con sindrome de Peutz Jeghers En Valencia. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed) 85(2):123–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orrantia-Borunda E, A-NP, Acuña-Aguilar LE et al (2022) Subtypes of breast Cancer. In: Mayrovitz HN, editor. Breast Cancer [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2022 Aug 6. Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Yang J, Peng L, Sahin AA, Huo L, Ward KC et al (2017) Triple-negative breast cancer has worse overall survival and cause-specific survival than non-triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 161(2):279–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen H, Wu J, Zhang Z, Tang Y, Li X, Liu S et al (2018) Association between BRCA status and Triple-Negative breast cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol 9:909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer Subtypes National Cancer Institute; [Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast-subtypes.html

- 46.van Seijen M, Lips EH, Thompson AM, Nik-Zainal S, Futreal A, Hwang ES et al (2019) Ductal carcinoma in situ: to treat or not to treat, that is the question. Br J Cancer 121(4):285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salvatorelli L, Puzzo L, Vecchio GM, Caltabiano R, Virzi V, Magro G (2020) Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: an update with emphasis on radiological and morphological features as predictive prognostic factors. Cancers (Basel) 12(3):609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Shaaban AM, Hilton B, Clements K, Provenzano E, Cheung S, Wallis MG et al (2021) Pathological features of 11,337 patients with primary ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and subsequent events: results from the UK Sloane project. Br J Cancer 124(5):1009–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lips EH, Kumar T, Megalios A, Visser LL, Sheinman M, Fortunato A et al (2022) Genomic analysis defines clonal relationships of ductal carcinoma in situ and recurrent invasive breast cancer. Nat Genet 54(6):850–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson AM, Clements K, Cheung S, Pinder SE, Lawrence G, Sawyer E et al (2018) Management and 5-year outcomes in 9938 women with screen-detected ductal carcinoma in situ: the UK Sloane project. Eur J Cancer 101:210–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elshof LE, Schaapveld M, Schmidt MK, Rutgers EJ, van Leeuwen FE, Wesseling J (2016) Subsequent risk of ipsilateral and contralateral invasive breast cancer after treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: incidence and the effect of radiotherapy in a population-based cohort of 10,090 women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 159(3):553–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanders ME, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Page DL (2005) The natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in women treated by biopsy only revealed over 30 years of long-term follow-up. Cancer 103(12):2481–2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanders ME, Schuyler PA, Simpson JF, Page DL, Dupont WD (2015) Continued observation of the natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ reaffirms proclivity for local recurrence even after more than 30 years of follow-up. Mod Pathol 28(5):662–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hwang ES, McLennan JL, Moore DH, Crawford BB, Esserman LJ, Ziegler JL (2007) Ductal carcinoma in situ in BRCA mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol 25(6):642–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Luijt PA, Heijnsdijk EA, Fracheboud J, Overbeek LI, Broeders MJ, Wesseling J et al (2016) The distribution of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) grade in 4232 women and its impact on overdiagnosis in breast cancer screening. Breast Cancer Res 18(1):47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryser MD, Weaver DL, Zhao F, Worni M, Grimm LJ, Gulati R et al (2019) Cancer outcomes in DCIS patients without locoregional treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 111(9):952–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elshof LE, Tryfonidis K, Slaets L, van Leeuwen-Stok AE, Skinner VP, Dif N et al (2015) Feasibility of a prospective, randomised, open-label, international multicentre, phase III, non-inferiority trial to assess the safety of active surveillance for low risk ductal carcinoma in situ - The LORD study. Eur J Cancer 51(12):1497–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Field K, Phillips K-A (2007) Management of women at high familial risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer Forum 31:141–149

- 59.Baranska A, Kanadys W (2022) Oral contraceptive use and breast Cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: systematic review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control studies. Cancers (Basel) 14(19):4774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Michaelson-Cohen R, Gabizon-Peretz S, Armon S, Srebnik-Moshe N, Mor P, Tomer A et al (2021) Breast cancer risk and hormone replacement therapy among BRCA carriers after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Eur J Cancer 148:95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huber D, Seitz S, Kast K, Emons G, Ortmann O (2021) Hormone replacement therapy in BRCA mutation carriers and risk of ovarian, endometrial, and breast cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 147(7):2035–2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, Lidegaard O (2017) Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 377(23):2228–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burchardt NA, Eliassen AH, Shafrir AL, Rosner B, Tamimi RM, Kaaks R et al (2022) Oral contraceptive use by formulation and breast cancer risk by subtype in the nurses’ health study II: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 226(6):821 e1- e26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roura E, Travier N, Waterboer T, de Sanjose S, Bosch FX, Pawlita M et al (2016) The influence of hormonal factors on the risk of developing cervical Cancer and Pre-Cancer: results from the EPIC cohort. PLoS ONE 11(1):e0147029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of, Cervical C, Appleby P, Beral V, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Colin D, Franceschi S et al (2007) Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16,573 women with cervical cancer and 35,509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet 370(9599):1609–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bevers TB, Ward JH, Arun BK, Colditz GA, Cowan KH, Daly MB et al (2015) Breast Cancer risk reduction, version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 13(7):880–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cuzick J, DeCensi A, Arun B, Brown PH, Castiglione M, Dunn B et al (2011) Preventive therapy for breast cancer: a consensus statement. Lancet Oncol 12(5):496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Visvanathan K, Fabian CJ, Bantug E, Brewster AM, Davidson NE, DeCensi A et al (2019) Use of endocrine therapy for breast Cancer risk reduction: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 37(33):3152–3165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.King MC, Wieand S, Hale K, Lee M, Walsh T, Owens K et al (2001) Tamoxifen and breast cancer incidence among women with inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: National surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project (NSABP-P1) breast Cancer prevention trial. JAMA 286(18):2251–2256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cobain EF, Milliron KJ, Merajver SD (2016) Updates on breast cancer genetics: clinical implications of detecting syndromes of inherited increased susceptibility to breast cancer. Semin Oncol 43(5):528–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, Dowsett M, Knox J, Cawthorn S et al (2014) Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 383(9922):1041–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ropka ME, Keim J, Philbrick JT (2010) Patient decisions about breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 28(18):3090–3095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith SG, Sestak I, Forster A, Partridge A, Side L, Wolf MS et al (2016) Factors affecting uptake and adherence to breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 27(4):575–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fornander T, Rutqvist LE, Cedermark B, Glas U, Mattsson A, Silfversward C et al (1989) Adjuvant Tamoxifen in early breast cancer: occurrence of new primary cancers. Lancet 1(8630):117–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DeMichele A, Troxel AB, Berlin JA, Weber AL, Bunin GR, Turzo E et al (2008) Impact of raloxifene or Tamoxifen use on endometrial cancer risk: a population-based case-control study. J Clin Oncol 26(25):4151–4159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Force USPST, Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M et al (2019) Medication use to reduce risk of breast cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 322(9):857–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sessa C, Balmana J, Bober SL, Cardoso MJ, Colombo N, Curigliano G et al (2023) Risk reduction and screening of cancer in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndromes: ESMO clinical practice guideline. Ann Oncol 34(1):33–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weidner AE, Liggin ME, Zuniga BI, Tezak AL, Wiesner GL, Pal T (2020) Breast cancer screening implications of risk modeling among female relatives of ATM and CHEK2 carriers. Cancer 126(8):1651–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gao C, Polley EC, Hart SN, Huang H, Hu C, Gnanaolivu R et al (2021) Risk of breast Cancer among carriers of pathogenic variants in breast Cancer predisposition genes varies by polygenic risk score. J Clin Oncol 39(23):2564–2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kurian AW, Gong GD, John EM, Johnston DA, Felberg A, West DW et al (2011) Breast cancer risk for noncarriers of family-specific BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: findings from the breast Cancer family registry. J Clin Oncol 29(34):4505–4509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The available anonymized clinical data is provided within the manuscript.