Abstract

Fusarium wilt of spinach, caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae (Fos), leads to substantial losses in spinach (Spinacia oleracea) seed production in the only region of the USA suitable for growing spinach seed crops, the maritime Pacific Northwest. Accessions of wild spinach, S. turkestanica, serve as a major source of resistance to multiple spinach diseases. In this study, 84 Spinacia genotypes (all 68 S. turkestanica accessions available publicly and 16 S. oleracea) were evaluated for reactions to Fos at medium and high densities of inoculum comprising a mix of isolates of races 1 and 2, using a factorial experimental design of genotypes (n = 84) and Fos inoculum density (0, 12,500, and 37,500 CFU/ml potting medium) with two replicates. The area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) calculated for wilt severity 28, 35, and 42 days after planting (DAP) ranged from 0.0 to 11.0 and 1.5 to 13.3 at medium and high inoculum densities, respectively. Of the 68 S. turkestanica accessions, 17 and 8 showed high levels of resistance at medium and high inoculum densities, respectively. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers (n = 7,065) identified with genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) were used for genome wide association studies (GWAS) using multiple models tested with GAPIT and TASSEL software. Twelve SNPs were associated significantly with Fusarium wilt resistance in 10 QTL regions located on chromosomes 1, 3, 4, and 6. SNP S6_38110665 on chromosome 6 was validated across multiple GWAS models and demonstrated a major effect (-2.48 to -2.79) at reducing Fusarium wilt severity. SNP S6_38110665 can be used to introduce Fusarium wilt resistance QTL into cultivated spinach (S. oleracea) using marker-assisted selection, thereby enhancing breeding programs for improved disease resistance.

Keywords: Fusarium wilt, GWAS, QTL, Resistance, Spinach, Spinacia turkestanica

Subject terms: Genetics, Plant sciences

Introduction

Fusarium wilt of spinach (Spinacia oleracea), caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae (Fos), is an important soilborne pathogen that can lead to substantial yield losses in spinach1,2. This disease poses a major threat to long-term viability of spinach seed production in the maritime Pacific Northwest (PNW) region of the United States due to the conduciveness of the acid soils of this region to long-term survival of the pathogen, and the limited management options available to seed growers3–6. In 2017, hybrid spinach seed production in the PNW occurred on approximately 2,000 ha, supplying up to 50 and 20% of the US and global seed demand, respectively [Puget Sound Seed Growers’ Association (PSSGA), Burlington, WA, personal communication]. Historically, seed growers in the PNW have managed Fusarium wilt by planting spinach seed crops on virgin land (no history of a spinach crop) or in fields with > 10 years of rotation out of spinach, application of agricultural limestone to increase soil pH, foliar application of the micronutrients Zn and Mn to counter reduced availability caused by agricultural limestone applications, and practices that improve overall soil health such as cover cropping and incorporation of organic amendments like compost4–6.

Resistance to spinach Fusarium wilt is an important component of integrated management of this disease in the PNW. Partial resistance to this disease is available in cultivated spinach germplasm7–9 but most contemporary spinach inbred lines used in hybrid seed production are very susceptible to Fos (PSSGA, personal communication). Furthermore, management of spinach Fusarium wilt is complex in the PNW as hybrid spinach seed crops are grown on a contractual basis because of the proprietary nature of the inbred lines of seed companies, i.e., spinach seed growers have very limited or no choice in the specific inbred lines they are contracted to plant3. In addition, seed contractors and growers often have inadequate understanding of the susceptibility to Fusarium wilt of the specific inbred lines they are contracted to plant for their hybrid spinach seed crops. As a result, even with the integrated management strategies described above, seed growers can experience major losses to Fusarium wilt if either of the inbred lines in a hybrid spinach seed crop is highly susceptible to Fusarium wilt6,10. Growers can incur losses of up to 100% if either inbred line dies prematurely due to susceptibility to Fusarium wilt, as female lines will sex-revert if there is inadequate pollination from the male line dying prematurely because of Fusarium wilt, and highly susceptible female lines die prior to setting seed4.

Spinacia turkestanica Iljin (2n = 2x = 12) is an immediate progenitor of cultivated spinach (S. oleracea [2n = 2x = 12])11 and accessions of this wild species have furnished important genetic resources for many commercially important genes12–16. For example, alleles conferring resistance to races of the downy mildew pathogen (Peronospora effusa) have been transferred from S. turkestanica to commercial spinach cultivars to protect crops against this devastating disease15,16. S. turkestanica genotypes should be characterized more extensively for economically important agronomic traits such as sources of resistance genes. This study employed genome wide association studies (GWAS) to map quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for resistance to spinach Fusarium wilt in S. turkestanica accessions using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) identified by genotype-by-sequencing (GBS).

Materials and methods

Plant material

In total, 84 genotypes of two Spinacia species, S. turkestanica (68) and S. oleracea (16), were used in this study. All 68 S. turkestanica accessions were collected originally from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and were received from the CGN, Wageningen University and Research (WUR) in 2019. All 16 S. oleracea accessions were received from the National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2018. Information on each accession, including the country of origin, is provided in Supplemental Table S1. In addition to the 16 S. oleracea lines, three proprietary spinach inbred lines known to be highly susceptible (S), moderately susceptible (MS), and partially resistant (R) to race 1 of Fos7,17, served as control treatments to compare with reactions of the S. turkestanica accessions to Fos.

Spinach Fusarium wilt resistance screening

The S. turkestanica and S. oleracea genotypes were grown in a greenhouse at 22–24 °C by day with supplemental lighting provided for 10 h day-1, and at 18–20 °C by night, as described by Batson et al7. The temperature in the greenhouse was increased to 24–27 °C during the day and 20–24 °C at night from 14 days after planting (DAP). A mix of three Fos isolates, namely Fus254 and Fus322 (isolates of race 1), and Fus058 (race 2), was used to generate medium and high inoculum densities in the potting medium, as reported by Batson et al7,17. The experiment included a factorial arrangement of Spinacia accessions (n = 84) and inoculum densities (n = 3), i.e., no inoculum [0 spores ml-1 of potting medium], medium inoculum density [12,500 spores ml-1 potting medium], and high inoculum density [37,500 spores ml-1 potting medium], with two replicates of each treatment combination. A six-cell standard tray insert (ST1-606 DP, T.O. Plastics, Clearwater, MN), with each cell 5.08 cm wide × 5.72 cm long × 8.43 cm deep, was used for sowing 12 seeds of each spinach genotype (2 seeds cell-1) approximately 1 cm deep in the potting medium. To control thrips (Thrips spp. and/or Frankliniella spp.), Botanigard 22WP [Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin, Laverlam International, Butte, MT) was applied at 2.4 g liter-1 in rotation with Entrust (spinosad, Dow Agrosciences, Indianapolis, IN) at 0.17 g liter-1 and Leverage 2.0 (imidacloprid, Bayer, Kansas City, MO) at 1.33 ml liter-1 on a weekly basis. At 14 DAP, seedlings were thinned to six plants per six-pack. Plants were fertigated with General Purpose 20:20:20 NPK fertilizer (Plant Marvel, Chicago, IL) injected into the irrigation water at a 1:100 ratio for applying a final nitrogen concentration of 200 ppm.

Severity of Fusarium wilt was rated 28, 35, and 42 DAP for each plant on a 0-to-5 ordinal wilt scale as described by Gatch and du Toit4, where: 0 = no visible wilt symptoms; 1 = cotyledons flaccid; 2 = first two true leaves flaccid and approximately 25% of the leaves wilting; 3 = approximately 50% of the leaves wilting; 4 = approximately 75% of the leaves wilting; and 5 = plant dead due to wilt. The number of seedlings in each disease severity category was recorded at each assessment, and the Fusarium wilt severity index (FWSI) as well as the area under the disease (wilt severity) progress curve (AUDPC) calculated4. After the final wilt severity rating, the stem of each plant was cut at the surface of potting medium and the aboveground tissue dried at ~ 60 °C to calculate dry spinach biomass for the 6 plants per replication per treatment combination.

Statistical analysis of phenotype data

To account for the non-homogeneous variances of FWSI and AUDPC ratings, the data were transformed using ranks averages before analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were calculated. All analyses were performed using JMP Pro 17.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC)18. In the ANOVAs, only data for inoculated plants, i.e., responses of Spinacia accessions in potting medium with the medium and high densities of Fos, were used because wilt symptoms were not observed or were highly negligible in the non-inoculated control potting medium. Means separations for wilt ratings of the Spinacia accessions were compared to those of the R, MS, and S inbred control treatments. The mean values of FWSI, AUDPC, and dry biomass of S. turkestanica (n = 68) and S. oleracea (n = 16) were compared using a t-test.

Sequencing and marker discovery

The details of DNA sequencing and marker discovery for the GWAS panel are described by Gyawali et al11. In summary, genomic DNA was isolated from a single frozen leaf of each plant using the cetyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method19,20, after the leaf was ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. The GBS method of Elshire et al21 was used to sequence the DNA extracted from each sample after digesting the genomic DNA with the ApeKI restriction enzyme, as described by Bhattarai et al22. Finally, 96-plex GBS libraries were amplified, purified, and sequenced as 150 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina NovaSeq machine (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Adaptors were removed and high-quality reads were aligned to the reference genome of spinach cultivar Sp7523. DNA sequencing was performed at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center, and SNPs were identified by the Bioinformatics Resource Center at the same institution. After a series of quality parameters for SNP filters were evaluated as detailed by Gyawali et al11, the high-quality SNP datasets were used for population structure and GWAS analyses.

Population structure, clustering, and GWAS

The population structure of the Spinacia genotypes based on Fusarium wilt resistance mapping was analyzed using STRUCTURE Version 2.3.4, with individual genotypes assigned to genetic clusters, hereafter called groups, based on inferred genetic ancestry24. The structure analysis was performed by setting an admixture model, with K ranging from 1 to 10, using five iterations, a burn in period of 100,000, and a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) run length of 100,000. The number of potential groups (K) were determined in Structure Harvester version 0.6.4 according to Evanno et al25. The resulting proportion of membership coefficients (Q matrices) for each accession was used to draw a bar plot to visualize clustering of the Spinacia genotypes. Spinacia species were assigned to individual groups (Q) based on an assignment value of 75%, otherwise considered an admix. The inferred ancestry assessments obtained from Structure were then judged based on prior knowledge of the geographic location of the original collection site of each genotype of S. turkestanica and S. oleracea, provided by the respective germplasm centers. The population groups (Q-values) and kinship matrix were used as a covariate in marker-trait association analyses. Furthermore, the genetic relationship among wild and cultivated spinach were inferred based on the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) in MEGA7. The marker-trait associations were analyzed using GLM, MLM, MLMM, SUPER, FarmCPU, and BLINK models in GAPIT; and using SMR, GLM, and MLM in TASSEL. Multiple GWAS models were tested with -log10 P-values (lod values) > 3.0 to validate any candidate spinach Fusarium wilt resistance QTLs identified.

Results

Fusarium wilt resistance in wild spinach

Based on the ANOVAs for FWSI calculated 28, 35, and 42 DAP, as well as the AUDPC values and spinach dry biomass for the GWAS panel of 87 lines (including the R, MS, and S control lines of S. oleracea), spinach genotype (G), Fos inoculum density (I), and the interaction terms (G × I) had highly significant effects on FWSI 28, 35, and 42 DAP, as well as AUDPC values (P < 0.005), but the G x I interaction effect on spinach dry biomass was not significant (P = 0.3059) (Supplemental Table S2). Therefore, the significant differences in severity of Fusarium wilt among Spinacia accessions occurred at both inoculum densities of Fos, although accessions varied regarding how much difference was observed in wilt severity between the two inoculum densities. Eight S. turkestanica genotypes, CGN 24956, CGN 24955, CGN 25002, CGN 24996, CGN 25005, CGN 24957, CGN 25138, and CGN 25086, had lower AUDPC values (≤ 3) and similar or less severe Fusarium wilt than those of the R control inbred when evaluated at the high inoculum density (Supplemental Table S3, Figs. 1 and 2). At the medium inoculum density, an additional 10 genotypes showed a resistant response (AUDPC ≤ 1.7) similar to that of the R control treatment.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of the reactions of a genome wide association study (GWAS) panel of wild spinach (Spinacia turkestanica [n = 68]) and cultivated spinach (S. oleracea [n = 16]) accessions assessed for response to inoculation with a mix of isolates of races 1 and 2 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae (Fos). (A) Mean Fusarium wilt severity index (FWSI) ratings for the Spinacia genotypes in potting medium with a high Fos inoculum density (37,500 spores ml-1 potting medium). (B) Mean area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) ratings for the Spinacia genotypes planted in potting medium with the high Fos inoculum density. (C) Mean FWSI ratings for the Spinacia genotypes planted in potting medium with a medium Fos inoculum density (12,500 spores ml-1 potting medium). (D) Mean AUDPC ratings for the Spinacia genotypes at the medium Fos inoculum density. Arrows with R, MS, and S represent the wilt severity ratings of partially resistant, moderately susceptible, and susceptible proprietary inbred lines of S. oleracea, respectively, that were used as control treatments.

Fig. 2.

Area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) of spinach Fusarium wilt severity index (FWSI) ratings in relation to spinach dry biomass (g plant-1) of Spinacia turkestanica (n = 68) and S. oleracea (n = 16) accessions in potting medium with a high inoculum density (37,500 spores ml-1) of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae (Fos). St1 to St75 are S. turkestanica genotypes, AM1 to AM330 are S. oleracea genotypes, and R, MS, and S represent partially resistant, moderately susceptible, and susceptible proprietary S. oleracea inbreds, respectively, used as control treatments. S. turkestanica and S. oleracea genotypes are ordered based on increasing AUDPC values for FWSI.

The AUDPC values for the R, MS, and S inbreds averaged 2.98, 7.59, and 9.77, respectively, at the high inoculum density; and 1.75, 5.49, and 8.17, respectively, at the medium inoculum density. The FWSI 42 DAP for R, MS, and S inbreds was 0.38, 0.74, and 0.82, respectively, at the high inoculum density; and 0.24, 0.53, and 0.77, respectively, at the medium inoculum density. The mean FWSI 42 DAP for S. turkestanica accessions (n = 68) at the high and medium inoculum densities was 0.49 and 0.35, respectively. The mean FWSI 42 DAP for S. oleracea accessions (n = 16) at the high and medium inoculum densities was 0.85 and 0.49, respectively. The mean FWSI 42 DAP for these 84 genotypes ranged from 0.26 to 1.0, with an average of 0.55 ± 0.04 at the high inoculum density; and from 0.0 to 0.85, with an average of 0.38 ± 0.04 at the medium inoculum density. The mean AUDPC for S. turkestanica accessions at the high and medium inoculum densities was 5.14 and 3.48, respectively. The mean AUDPC for the 16 S. oleracea accessions at the high and medium inoculum densities was 9.63 and 4.33, respectively. The mean AUDPC values of the 84 Spinacia accessions ranged from 1.49 to 13.3 with a mean ± standard error of 6.01 ± 0.67 at the high inoculum density, and from 0.0 to 11.03 with a means of 3.64 ± 0.58 at the medium inoculum density. Dry spinach biomass of the R, MS, and S inbreds averaged 0.79, 0.47, and 0.49 g plant-1, respectively, at the high inoculum density; and 0.60, 0.72, and 0.78, respectively, at the medium inoculum density. The mean dry biomass of the S. turkestanica accessions at the high and medium inoculum densities was 0.78 and 0.82 g plant-1 respectively. In contrast to wild spinach, the cultivated spinach accessions had a mean dry biomass at the high and medium inoculum densities of 0.06 and 0.24 g plant-1 respectively. The mean spinach biomass of these accessions ranged from 0.01 to 1.3 g plant-1 with an average of 0.61 ± 0.15 g plant-1 at the high inoculum density; and from 0.03 to 1.41 g plant-1 with an average of 0.71 ± 0.14 g plant-1 at the medium inoculum density. The t-test for FWSI of the S. turkestanica and S. oleracea accessions revealed significant differences in wilt severity of these species at both high (P < 0.0001) and medium (P = 0.032) inoculum densities (Table S3). The t-test for AUDPC values of FWSI for S. turkestanica vs. S. oleracea accessions revealed significant differences in mean AUDPC values of these species at the high inoculum density (P < 0.0001) but not at the medium inoculum density (P = 0.207). Likewise, the t-test of FWSI of S. turkestanica vs. S. oleracea accessions revealed significant differences for the two species at both high and medium (P < 0.0001) inoculum densities.

The severity of Fusarium wilt for the 84 Spinacia accessions, measured as FWSI 24 DAP and AUDPC values, was skewed toward susceptibility at the high inoculum density compared to a more normal distribution at the medium inoculum density (Fig. 1). As expected, the more susceptible S. turkestanica accessions had much lower spinach biomass compared to the MS and R control inbred lines and the more resistant accessions of S. turkestanica (Fig. 2). The low spinach biomass of most of the S. oleracea genotypes reflected the fact that more S. oleracea genotypes were highly susceptible to Fos compared to a majority of the S. turkestanica genotypes. For example, although St68 and St30 had greater AUDPC values than all the S. oleracea accessions except AM55, the biomass of these two S. turkestanica accessions was greater than that of all the S. oleracea accessions. As expected, there was a strong positive correlation (P < 0.0001) between FWSI and AUDPC values 28, 35, and 42 DAP, and strong negative correlations (P < 0.0001) between dry spinach biomass and severity of Fusarium wilt at both Fos inoculum densities (Supplemental Table S4).

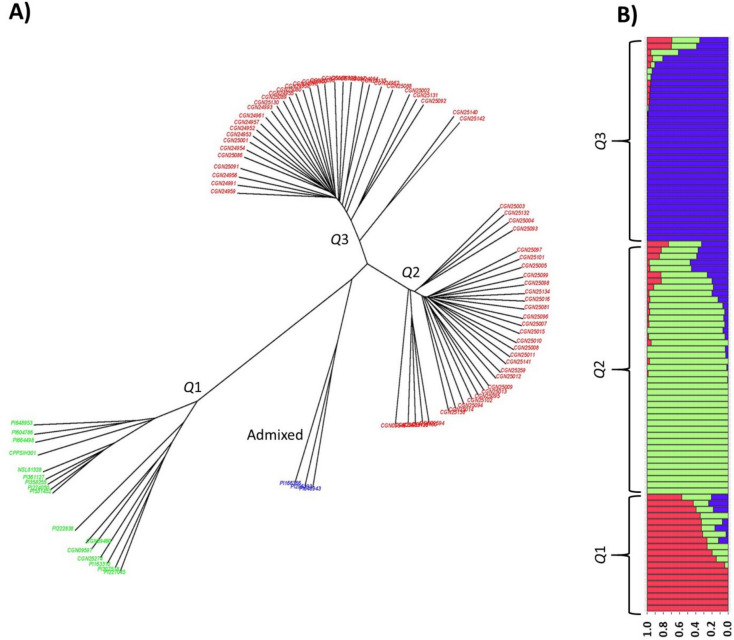

Population structure of S. turkestanica and S. oleracea accessions

The multivariate analysis using UPGMA revealed three distinct Spinacia groups: Q1 comprised only S. oleracea accessions, Q2 comprised S. turkestanica accessions from Uzbekistan, and Q3 comprised accessions of S. turkestanica from Tajikistan, with some genotypes admixed (Fig. 3A). The multivariate analysis was supported by the STRUCTURE analysis, as group Q1 included cultivated spinach, including all S. oleracea accessions and accessions with varying degrees of admixing of S. oleracea and S. turkestanica; group Q2 included only S. turkestanica accessions collected in Uzbekistan, and group Q3 included only S. turkestanica accessions in Tajikistan (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Population structure of a spinach Fusarium wilt mapping panel consisting of 68 accessions of Spinacia turkestanica and 16 accessions of S. oleracea. (A) Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean phylogenetic tree of whole genome sequences showing three distinct groups of Spinacia accessions represented by: Q1 with S. oleracea accessions (cultivated spinach), Q2 with S. turkestanica wild spinach accessions collected from Uzbekistan, and Q3 with S. turkestanica wild spinach accessions collected from Tajikistan. (B) Population structure of Spinacia accessions with three groups, Q1, Q2, and Q3.

GWAS and candidate genes

Using multiple GWAS models, four significant SNPs were found to be associated with QTL for resistance to Fusarium wilt when accessions were screened at the medium inoculum density: S1_25951949 and S1_48745097 on chromosome 1, S3_4557414 on chromosome 3, and S6_38110665 on chromosome 6; and eight significant SNPs at the high inoculum density: S1_29168394 and S1_44196225 on chromosome 1; S3_10604391, S3_10604403, and S3_10604424 on chromosome 3; S4_92628754 on chromosome 4; and S6_11538772 and S6_35488289 on chromosome 6 (Table 1, Fig. 4A). The Q-Q plot of QTL on chromosome 6 for GLM, MLM, SUPER, MLMM, FramCPU, and Blink models are presented in Fig. 4B and Supplemental Fig. 1. Three of these SNPs, S3_10604391, S3_10604403, and S3_10604424, mapped close together on chromosome 3 and, therefore, are considered part of the same Fos resistance QTL. Of the 12 total SNPs significantly associated with resistance phenotypes, S3_10604424 on chromosome 6 detected at the medium inoculum density was validated with all nine GWAS models tested. The -log10 P-value (lod-value) of this QTL ranged from 3.64 to 9.24, and the marker effects of this QTL ranged from -2.5 to -2.8 for severity of spinach Fusarium wilt (Table 2). Candidate genes detected within 5 Kb of putative QTLs in the accessions screened included a complex 1 LYR-like protein on chromosome 3 near Spo09924, and a two-component response regulator on chromosome 3 near Spo13199 (Supplemental Table S5). A major QTL on chromosome 6 (SNP S6_3811072) was close to a transcription factor, dehydration-responsive element-binding protein 2A. The D111/G-patch domain protein, WRKY DNA-binding protein 22, and 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase were each within 20 Kb of the SNP S6_3811072 (Supplemental Table S5).

Table 1.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers associated with Fusarium wilt resistance, chromosome location of the SNPs, inoculum density of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae at which Fusarium wilt severity was evaluated, and genome wide association study (GWAS) models used to validate quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for wilt resistance in a panel of 68 accessions of wild spinach, Spinacia turkestanica.

| SNP† | CH‡ | Position | Inoculum density § | BLINK | FarmCPU | MLM | MLMM | SUPER | GLM | T.MLM | T-GLM | SMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS model lod value# | ||||||||||||

| S1_25951949 | 1 | 25,951,949 | Medium | 2.86 | 5.11 | 1.31 | 2.86 | 1.55 | 1.46 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 1.15 |

| S1_29168394 | 1 | 29,168,394 | High | 3.36 | 3.36 | 2.97 | 3.33 | 3.06 | 2.99 | 2.39 | 2.71 | 1.97 |

| S1_44196225 | 1 | 44,196,225 | High | 3.23 | 3.23 | 2.83 | 3.15 | 2.86 | 2.89 | 2.24 | 2.55 | 0.90 |

| S1_48745097 | 1 | 48,745,097 | Medium | 2.17 | 5.32 | 1.85 | 2.17 | 2.02 | 2.05 | 1.73 | 1.82 | 3.11 |

| S3_4557414 | 3 | 4,557,414 | Medium | 2.13 | 5.73 | 2.39 | 2.13 | 2.66 | 2.62 | 2.27 | 3.09 | 0.86 |

| S3_10604391 | 3 | 10,604,391 | High | 1.52 | 1.52 | 1.46 | 1.51 | 1.43 | 1.47 | 3.02 | 3.42 | 9.67 |

| S3_10604403 | 3 | 10,604,403 | High | 1.52 | 1.52 | 1.46 | 1.51 | 1.43 | 1.47 | 3.02 | 3.42 | 9.67 |

| S3_10604424 | 3 | 10,604,424 | High | 1.52 | 1.52 | 1.46 | 1.51 | 1.43 | 1.47 | 3.02 | 3.42 | 9.67 |

| S4_92628754 | 4 | 92,628,754 | High | 3.20 | 3.20 | 2.87 | 3.19 | 3.05 | 2.86 | 3.51 | 4.28 | 1.40 |

| S6_11538772 | 6 | 11,538,772 | High | 3.48 | 3.48 | 3.05 | 3.44 | 3.14 | 3.08 | 3.90 | 4.77 | 1.31 |

| S6_35488289 | 6 | 35,488,289 | High | 3.35 | 3.35 | 2.94 | 3.29 | 3.13 | 2.98 | 2.20 | 2.42 | 1.09 |

| S6_38110665 | 6 | 38,110,665 | Medium | 7.91 | 9.24 | 4.49 | 6.58 | 5.34 | 5.11 | 3.64 | 5.71 | 6.03 |

†SNP = Single nucleotide polymorphism.

‡CH = Chromosome on which the SNP was detected.

§Inoculum density = density of spores of F. oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae added to the potting medium in which spinach accessions were planted to evaluate for severity of Fusarium wilt symptoms. Medium = 12,500 spores ml-1 of potting medium. High = 37,500 spores ml-1 of potting medium.

#The GWAS models BLINK, FarmCPU, GLM, MLM, MLMM, and SUPER were calculated using Genome Association and Prediction Integrated Tool 3 (GAPIT 3), while T.GLM (Tassel.GLM) and T.MLM (Tassel.MLM) were calculated using TASSEL software. GWAS lod value = -log10 (P-value).

Fig. 4.

Manhattan and Quantile–Quantile (QQ) plots of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) associated with Fusarium wilt resistance QTL detected in a population of 68 accessions of wild spinach, Spinacia turkestanica, and 16 cultivated spinach, Spinacia oleracea, lines evaluated at a medium inoculum density (12,500 spores ml-1) of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae (Fos). (A) The significant SNP, S6_38110665, on chromosome 6 was validated in each of six genome wide association study (GWAS) models calculated using GAPIT: BLINK, FarmCPU, GLM, MLM, MLMM, and SUPER. (B) QQ plots of each of the six GWAS models show the expected null distribution of P-values vs. observed P-values. The Manhattan and QQ plots were produced with the Genome Association and Prediction Integrated Tool (GAPIT) package in R.

Table 2.

Validation of a major spinach Fusarium wilt resistance quantitative trait locus (QTL) on chromosome 6 and the associated marker effects on reducing severity of Fusarium wilt in accessions of Spinacia turkestanica.

| SNP† | CH‡ | SNP position | lod (-log10[P]) | P-value | Marker effect§ | GWAS model# | MAF%£ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S6_38110665 | 6 | 38,110,665 | 7.91 | 1.24E-08 | Blink | 11.30% | |

| 9.24 | 5.76E-10 | -2.79 | FarmCPU | ||||

| 5.11 | 7.77E-06 | -2.63 | GLM | ||||

| 4.49 | 3.25E-05 | -2.48 | MLM | ||||

| 6.58 | 2.64E-07 | MLMM | |||||

| 5.34 | 4.54E-06 | SUPER | |||||

| 5.71 | 1.93E-06 | T.GLM | |||||

| 3.64 | 2.29E-04 | T.MLM |

†SNP = Single nucleotide polymorphism.

‡CH = Chromosome.

§SNP effect on severity of spinach Fusarium wilt. Negative values represent association with less severe Fusarium wilt.

#Genome wide association study (GWAS) models BLINK, FarmCPU, GLM, MLM, MLMM, and SUPER were run using Genome Association and Prediction Integrated Tool 3 (GAPIT 3). T.GLM (Tassel.GLM) and T.MLM (Tassel.MLM) models were run in TASSEL software.

£MAF = minor allele frequency.

Discussion

In this study, screening accessions of S. turkestanica for resistance to Fusarium wilt using medium and high inoculum densities of Fos facilitated the mapping and validation of QTLs associated with resistance to Fos based on various GWAS models. Eight S. turkestanica accessions, St-21 (CGN 24956), St-17 (CGN 24955), St-58 (CGN 25002), St-25 (CGN 24996), St-55 (CGN 25005), St-57 (CGN 24957), St-20 (CGN 25138), and St-45 (CGN 25086), showed greater resistance to Fos than the partially resistant inbred control line, even at the high inoculum density. The wide variation in Fos resistance observed across the 68 S. turkestanica accessions and 16 S. oleracea accessions at both medium and high inoculum densities suggests that Fos resistance in spinach is quantitative. Supporting this was the detection of a major QTL associated with SNP S6_38110665 on chromosome 6, which was validated using eight GWAS models.

Resistance to Fos is one of the most important breeding goals in spinach seed production in the PNW region of the United States because the acid soils in this region are highly conducive to Fusarium wilt4,10. Therefore, the high Fos inoculum pressure in this region has necessitated very long rotations between spinach seed crops, although this can be ameliorated with applications of agricultural limestone to raise the soil pH close to neutral, along with foliar applications of micronutrients, and fungicide seed treatments, even though these add to the cost of spinach seed production6. Furthermore, spinach inbreds used in hybrid seed production often are susceptible to Fos7,10. Hence, identifying sources of resistance to Fos, mapping the location of resistance genes, and introgressing resistance from different sources, such as spinach landraces and wild relatives, are important to develop spinach cultivars with greater resistance to Fusarium wilt. Evidence for quantitative resistance to Fos in spinach germplasm, and the limited understanding of races of the pathogen in regions of spinach seed production around the world, combined with the lower priority of resistance to Fusarium wilt in major spinach breeding programs compared to breeding for resistance to the many races of the downy mildew pathogen, have contributed to slow progress at improving resistance to Fusarium wilt in spinach.

Introgression of resistance from wild relatives has been demonstrated successfully in many crop species, including cereals and vegetables26–30. Therefore, utilization of wild genetic resources for discovery of novel sources of resistance and introgression of these resistance gene(s) into elite germplasm has become integral to crop breeding programs globally. In spinach, there are a few examples of introgression of genes from wild relatives, a majority of which have been for downy mildew (P. effusa) resistance31,32. To our knowledge, this study appears to be the first mapping study of resistance to Fos using wild relatives of spinach. Furthermore, the quantitative nature of Fos resistance in Spinacia, the occurrence of both races of the pathogen in spinach seed production regions, and the demand for selection of horizontal resistance to both races led to the use of a GWAS approach in this study for mapping resistance to Fos. The GWAS study demonstrated three distinct groups in the panel of 84 accessions evaluated. Accessions in group 1 (Q1) separated from those of the wild spinach accessions (Q2 and Q3) and represented all 16 of the cultivated spinach (S. oleracea) accessions screened. Group 2 (Q2) represented accessions collected from Uzbekistan, while group 3 (Q3) mostly represented accessions collected from the Tajikistan region. Gyawali et al11 reported two distinct groups of S. turkestanica accessions collected from central Asia, represented as Q2 and Q3 in that study. Interestingly, out of the eight most resistant S. turkestanica accessions identified in this study, five (St-21, St-17, St-25, St-57, and St-45) were in group Q3 (mostly from Tajikistan), two (St-20 and St-55) were in group Q2 (from Uzbekistan), while St-58 included an admixture of groups Q2 (33.9%) and Q3 (61.4%). The population structure and grouping of resistance to Fos among the S. turkestanica accessions identified in this study should provide spinach breeders with a diversity of sources of resistance to Fusarium wilt. However, it remains to be determined if these sources of resistance are allelic or not. Further research is warranted to elucidate the heritability and allelic nature of these sources of resistance associated with the two main Q groups of S. turkestanica.

In this study, four QTLs were identified and mapped when accessions were evaluated using a medium inoculum density of Fos, while six resistance QTL were found by screening the 86 accessions with a high inoculum density. Both inoculum density treatments included a mix of three isolates representing races 1 (two isolates) and 2 (one isolate). Therefore, the resistance to spinach Fusarium wilt detected in this study appears to be broad resistance to both races 1 and 2 of Fos. Overall, 12 significant SNPs were identified in association with Fusarium wilt resistance at the medium and high inoculum density treatments. Of these SNPs, S6_38110665, which mapped to chromosome 6, was validated in nine GWAS models (Fig. 4A). The marker association in the QQ plot for the QTL on chromosome 6 suggests that the confounding effects of population structure and relatedness were well controlled by the GWAS models GLM, MLM, SUPER, MLMM, FramCPU, and Blink (Fig. 4B). The marker effect of this QTL was high and ranged from -2.5 to -2.8, suggesting that S6_38110665 alone could reduce severity of spinach Fusarium wilt by 2.5 to 2.8 AUDPC units.

The dehydration-responsive element-binding protein 2A (DREB) was detected within 5 Kb of SNP S6_38110665, making this transcription factor a target for future studies on resistance to Fusarium wilt in spinach. This transcription factor has been reported to regulate abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in diverse crops33–36 and should be investigated for a potential role in resistance to spinach Fusarium wilt. Another transcription factor, ethylene responsive element binding factor 2 (ERF2), was detected 10 Kb from the same Fusarium wilt resistance QTL, and has been demonstrated to play an important role in pathogenesis-related (PR) genes37,38 and abiotic stress tolerance39–41. Resistance to Fos in spinach germplasm appears to be polygenic but may also be controlled by a few oligo-genes. Therefore, DREB and ERF2 should be evaluated for their role in resistance to Fusarium wilt in spinach. The SNP information revealed by this study could benefit spinach breeders by converting SNP markers into high throughput markers, followed by marker assisted selection (MAS) for resistance to Fos. Furthermore, the wild accessions evaluated are available publicly from the CGN gene bank in the Netherlands.

Conclusions

Resistance to Fusarium wilt of spinach has gained increased attention in recent years due to the growing demand for spinach seed to meet the increase in consumer demand for baby leaf spinach, which entails very dense seeding rates. Contemporary spinach germplasm, including inbreds, breeding lines, and hybrids, generally have lacked robust resistance to Fusarium wilt. In this study, we identified eight S. turkestanica accessions collected from central Asia that had resistant reactions to Fos. A major resistance QTL was mapped to chromosome 6 and validated using nine GWAS models. A marker-assisted selection program could be employed to introgress this QTL into S. oleracea, and to enhance resistance to Fusarium wilt in spinach hybrids.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was received from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative Project No. 2017-51181-26830, the Alfred Christianson Endowment in Vegetable Seed Science, and Washington State University College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences Hatch Project Nos. WNP0010 and WNP00595. We thank members of the Vegetable Seed Pathology Program at Washington State University for excellent technical assistance with phenotyping of the wild spinach accessions.

Author contributions

S.G. and L.J.d.T. designed and conceived the research. S.G. carried out the phenotyping experiments. S.G. and G.B. analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. L.J.d.T. and A.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript based on three reviewers’ comments.

Funding

Financial support for this study was received from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative Project No. 2017–51181-26830, the Alfred Christianson Endowment in Vegetable Seed Science, and Washington State University College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences Hatch Project Nos. WNP0010 and WNP00595.

Data availability

The datasets for this study, including SNP markers generated during and/or analyzed, are included in the supplemental files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ainong Shi, Email: ashi@uark.edu.

Lindsey J. du Toit, Email: dutoit@wsu.edu

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-98932-x.

References

- 1.Correll, J. C. et al. Economically important diseases of spinach. Plant Dis.78, 653–660. 10.1094/PD-78-0653 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsson, M. & Gerhardson, B. Disease progression and yield losses from root disease caused by soilborne pathogens of spinach. Phytopath.82, 403–406 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foss, C.R. & Jones, L.J. Crop Profile for Spinach Seed in Washington. US Dep. Agric. Natl. Pest Manage. Centers (2005).

- 4.Gatch, E. W. & du Toit, L. J. A soil bioassay for predicting the risk of spinach Fusarium wilt. Plant Dis.99, 512–526. 10.1094/PDIS-08-14-0804-RE (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gatch, E. W. & du Toit, L. J. Limestone mediated suppression of Fusarium wilt in spinach seed crops. Plant Dis.101, 81–94. 10.1094/PDIS-04-16-0423-RE (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gyawali, S., Derie, M. L., Gatch, E. W., Sharma-Poudyal, D. & du Toit, L. J. Lessons from 10 years of stakeholder adoption of a soil bioassay for assessing the risk of spinach Fusarium wilt. Plant Pathol.70, 778–791. 10.1111/ppa.13335 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batson, A. M., Gyawali, S. & du Toit, L. J. Shedding light on races of the spinach Fusarium wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae. Phytopath.112, 2138–2150. 10.1094/PHYTO-03-22-0107-R (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laguna, R. Screening for disease resistance to Fusarium wilt of spinach. MS thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR (2000).

- 9.O’Brien, M. J. & Winters, H. F. Evaluation of spinach accessions and cultivars for resistance to Fusarium wilt. I. Greenhouse-bench method. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci.102, 424–426 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gatch, E.W. Management of Fusarium wilt in spinach seed crops in the maritime Pacific Northwest USA. PhD Dissertation, Washington State University, Pullman, WA USA. https://mtvernon.wsu.edu/VSP/Gatch-dissertation-8-2013.pdf (2013). [Accessed 22 January 2024]

- 11.Gyawali, S., Bhattarai, G., Shi, A., Kik, C. & du Toit, L. J. Genetic diversity, structure, and selective sweeps in Spinacia turkestanica associated with the domestication of cultivated spinach. Front Genet.12, 740437. 10.3389/fgene.2021.740437 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones, R. K. & Dainello, F. J. Occurrence of race 3 of Peronospora effusa on spinach in Texas and identification of sources of resistance. Plant Dis.66, 1078–1079 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherbakoff, C. D. Breeding for resistance to Fusarium and Verticillium wilts. Bot. Rev.15, 377–422 (1949). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith, L. B. Breeding mosaic resistant spinach and notes on malnutrition. Bull. VA Truck Exp. Stat.31, 137–160 (1920). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith, P. G. Downy mildew immunity in spinach. Phytopath.40, 65–68 (1950). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith, P. G. & Zahara, M. B. New spinach immune to mildew: hybrid variety developed by plant breeding program intended for use where Viroflay is adapted, produces comparable yield. Hilgardia10, 15. 10.3733/ca.v010n07p15 (1956). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batson, A. M., Fokkens, L., Rep, M. & du Toit, L. J. Putative effector genes distinguish two pathogenicity groups of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae. MPMI34, 141–156. 10.1094/MPMI-06-20-0145-R (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.JMP Pro. 17. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007.

- 19.Murray, M. G. & Thompson, W. F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res.8, 4321–4325 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porebski, S. L., Bailey, G. & Baum, B. R. Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Mole. Biol. Report15, 8–15 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elshire, R. J. et al. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE6, e19379. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019379 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattarai, G. et al. Genome wide association studies in multiple spinach breeding populations refine downy mildew race 13 resistance genes. Front. Plant Sci.11, 563187. 10.3389/fpls.2020.563187 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu, C. et al. Draft genome of spinach and transcriptome diversity of 120 Spinacia accessions. Nat. Commun.8, 15275. 10.1038/ncomms15275 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics155, 945–959 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol.14, 2611–2620 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dempewolf, H. et al. Past and future use of wild relatives in crop breeding. Crop Sci.57, 1070–1082. 10.2135/cropsci2016.10.0885 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fatima, F. et al. Identification of new leaf rust resistance loci in wheat and wild relatives by array-based SNP genotyping and association genetics. Front. Plant Sci.11, 583738. 10.3389/fpls.2020.583738 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajjar, R. & Hodgkin, T. The use of wild relatives in crop improvement: A survey of developments over the last 20 years. Euphytica156, 1–13. 10.1007/s10681-007-9363-0 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wulff, B. B. H. & Moscou, M. J. Strategies for transferring resistance into wheat: From wide crosses to GM cassettes. Front. Plant Sci.5, 692. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00692 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, H., Mittal, N., Leamy, L. J., Barazani, O. & Song, B. H. Back into the wild - apply untapped genetic diversity of wild relatives for crop improvement. Evol. Applic.10, 5–24. 10.1111/eva.12434 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandenberger, L. P., Morelock, T. E. & Correll, J. C. Evaluation of spinach germplasm for resistance to a new race (race 4) of Peronospora farinosa f. sp. spinaciae. HortSci.27(20), 1118–1119 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Handke, S., Seehaus, H. & Radies, M. Detection of a linkage of the four dominant mildew resistance genes ‘“M1 M2 M3 M4”’ in spinach from the wildtype Spinacia turkestanica. Gartenbauwissenschaft65, 73–78 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ain-Ali, Q.-U. et al. Genome-wide promoter analysis, homology modeling and protein interaction network of Dehydration Responsive Element Binding (DREB) gene family in Solanum tuberosum. PLoS ONE16, e0261215. 10.1371/journal.pone.0261215 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akbudak, M. A., Filiz, E. & Kontbay, K. DREB2 (dehydration-responsive element-binding protein 2) type transcription factor in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor): Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression profiles under cadmium and salt stresses. Biotech8, 426. 10.1007/s13205-018-1454-1 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baillo, E. H., Kimotho, R. N., Zhang, Z. & Xu, P. Transcription factors associated with abiotic and biotic stress tolerance and their potential for crops improvement. Genes10, 771. 10.3390/genes10100771 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizoi, J., Shinozaki, K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. AP2/ERF family transcription factors in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech.1819, 86–96. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.08.004 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarthy, S. et al. The tomato transcription factor Pti4 regulates defense-related gene expression via GCC box and non-GCC box cis elements. Plant Cell15, 3033–3050 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohme-Takagi, M. & Shinshi, H. Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell7, 173–182 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujimoto, S. Y., Ohta, M., Usui, A., Shinshi, H. & Ohme-Takagi, M. Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. Plant Cell12, 393–404 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin, L.-G., Li, H. & Liu, J.-Y. Molecular characterization of three ethylene responsive element binding factor genes from cotton. J. Integr. Plant Biol.52, 485–495. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00914.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohta, M., Ohme-Takagi, M. & Shinshi, H. Three ethylene-responsive transcription factors in tobacco with distinct transactivation functions. Plant J.22, 29–38 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this study, including SNP markers generated during and/or analyzed, are included in the supplemental files.