ABSTRACT

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (1), a honeybee propolis component, possesses many bioactive properties, making it a useful scaffold for drug research. Further, CAPE (1) is a more effective inhibitor of the biosynthesis of 5‐lipoxygenase (5‐LO) products compared to Zileuton, the only clinically‐approved direct 5‐LO inhibitor. However, CAPE (1) suffers from a poor metabolic profile, being rapidly metabolized to caffeic acid (CA). In this study, we synthesized and performed several biological assays on a new bioisostere of CAPE (1) possessing a 1,2,4‐oxadiazole ring. The new bioisostere (OB‐CAPE (5)) has a similar antiproliferative effect to CAPE (1) on NCI‐60 cancer cell lines and maintains the activity of CAPE (1) as an inhibitor of the biosynthesis of 5‐, 12‐ and 15‐LO products and as an iron chelator. In human polymorphonuclear leukocytes, OB‐CAPE (5) inhibits the biosynthesis of 5‐LO products with an IC50 of 0.93 µM compared to 1.0 µM for CAPE (1). Both compounds have similar antioxidant activity, with IC50 values of 1.2 µM for OB‐CAPE (5) and 1.1 µM for CAPE (1). The new hydrogen bond predicted for the oxadiazole ring and the GLN363 amino acid in the 5‐LO active site may explain the small improvement in the affinity of OB‐CAPE (5) for the protein compared to CAPE (1). Finally, stability studies in human plasma reveal that OB‐CAPE (5) is 25% more stable than CAPE (1). Therefore, the increase in stability associated with the replacement of the ester function with its bioisostere, while maintaining the anti‐inflammatory and anticancer properties of CAPE (1), suggests that OB‐CAPE (5) may be a comparable yet more stable candidate for in vivo studies in disease models.

Keywords: anti‐leukotriene therapy, bioisosteres, caffeic acid phenethyl ester, inflammation

1. Introduction

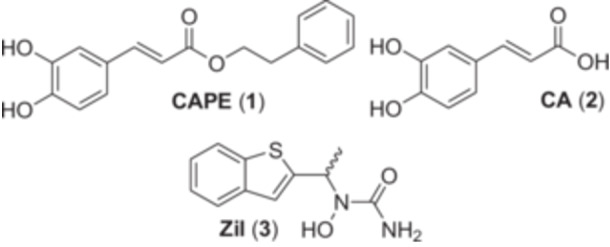

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE (1), Figure 1) has been studied for its antioxidant, antiproliferative, anti‐inflammatory, and antibacterial activities (Russo, Longo, et Vanella 2002; Shin et al. 2017; Sud'ina et al. 1993; Zeng et al. 2022). In comparison with caffeic acid (CA (2)), CAPE (1) is a much stronger iron chelator in biological settings, likely due to its increased lipophilicity, which allows it to penetrate the cell membrane more reliably (Shao et al. 2020, 2021). We previously demonstrated that CAPE (2) could inhibit the biosynthetic activity of 5‐lipoxygenase (5‐LO), and that it was more effective than CA (2) and Zileuton (Zil (3)), the only 5‐LO inhibitor approved by the FDA (Boudreau et al. 2012). Furthermore, Zil (3) has had limited clinical use due to its hepatotoxic metabolites, products of the Cytochrome P450 pathway (Joshi et al. 2004; Lu et al. 2003).

FIGURE 1.

Structures of compounds used as reference throughout this study.

Lipoxygenases (LO) are involved in the inflammatory response via the metabolism of arachidonic acid, to which they catalyze the addition of molecular oxygen. In humans, there exists six different LO genes whose translated products play key roles in the immune response either by producing pro‐inflammatory or pro‐resolution mtabolites (Kuhn, Banthiya, et Van Leyen 2015). The 5‐, 12‐ and 15‐LO have been linked to many diseases, including atherosclerosis, several cancers, asthma and Alzheimer's disease (Folcik et al. 1995; Haeggström et Funk 2011; Ikonomovic et al. 2008; Natarajan 1999; Peters‐Golden et Henderson 2007; Rong et al. 2012; Wegner et al. 1993). The major mechanism through which 5‐LO is involved in diseases seems to be via the biosynthesis of the leukotrienes (LTs), most notably LTB4, a potent leukocyte chemoattractant, and the vascular muscle constricting cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs), LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 (Henderson 1994). Besides Zil (3), other clinically approved compounds that interfere with the 5‐LO pathway are CysLTs receptor antagonists, such as Montelukast and Zafirlukast (Bisgaard 2001; Calhoun 1998).

Although the metabolism of CAPE (1) has not yet been thoroughly investigated, the few resources available seem to indicate that it is rapidly metabolized to CA in vitro, either when incubated in rat plasma or with HT‐29 colon cancer cells (Celli et al. 2007; Mbarik et al. 2019; Tang et al. 2017). As such, the need to synthesize new derivatives of CAPE (1) that are more stable in vivo is an ongoing effort to alleviate the pharmacological hurdles faced by this compound.

One way to achieve this goal is to use bioisosterism, which involves the replacement of a functional group within an organic molecule with another that plays a similar biological role (Patani et LaVoie 1996). 1,2,4‐Oxadiazoles are among the ester bioisosteres that have been investigated for their ability to maintain biological activity, without the susceptibility to esterases (Camci et Karali 2023). We recently synthesized a derivative of sinapic acid phenethyl ester with a 1,2,4‐oxadiazole ring in place of the ester and demonstrated that it kept its capacity to inhibit the biosynthesis of 5‐LO products as effectively as its ester analog (Touaibia et al. 2022).

Therefore, the aim of this study was to apply this same modification to CAPE (1), and further investigate the impact of the 1,2,4‐oxadiazole ring on the stability and biological activity of CAPE (1). The biological activity of CAPE (1) and its oxadiazole bioisostere (OB‐CAPE (5)) as inhibitors of LOs in cellular models, their antioxidant, iron chelation and anticancer activities were measured, as well as their stability in human plasma. Furthermore, molecular docking experiments were performed in silico, giving a greater view of the interaction of OB‐CAPE (5) within 5‐LO.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Synthetic Experimental Procedure

All chemicals were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. All reactions were carried under argon atmosphere. Purification was carried out with reagent‐grade solvents, and TLC analyses were conducted using silica gel‐coated aluminum sheets (SiliaPlate TLC, Silicycle®). TLC results were revealed by UV light (254 nm). Purification was carried out by flash chromatography (Isco Inc. CombiFlash™ Sg100c). 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded using a Bruker AV‐III‐400 spectrometer; spectra were recorded at room temperature. Chemical shifts (δ values) were referenced to the deuterated solvent peak and recorded in parts per million. NMR data were reported as δ value (where s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, and quin = quintuplet, integration, J value (Hz)). High‐resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) measurements were performed on an Agilent 6200 high‐resolution time‐of‐flight mass spectrometer equipped with a Dual ESI ion source. Analytical high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on an Agilent Technologies system (Agilent1100 Series) with an ACE C18column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) using Milli‐Q water (A) and HPLC grade methanol (B) as mobile phase in isocratic mode (25%:75% (A:B; 15 min); flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, detection at 320 nm).

2.2. Synthesis of OB‐CAPE (5)

To a solution of (E)‐3,4‐dihydroxycinnamic acid (CA; 2) (0.9 g, 4.99 mmol), 2‐ (1H‐benzotriazol‐1‐yl)‐1,1,3,3‐tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU: 2.1 g, 5.53 mmol, 1.5 equiv) and N,N‐diisopropylethyl‐amine (DIEA: 2.6 mL, 2.6 mmol, 3 equiv) dissolved in DMF (10 mL) at room temperature was added N′‐hydroxy‐3‐phenylpropanamidine (4) (Cai et al. 2016) (820 mg, 4.99 mmol, 1 equiv). Following stirring for 24 h, the reaction mixture was poured in 50 mL of H2O. EtOAc (3 × 25 mL) was used to extract the product, and combined organic layers were subsequently washed with brine (3 × 25 mL). The product was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and extraction solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure. Following dissolution in DMF (15 mL), the reaction mixture was heated at 120°C for 24 h. Water (25 mL) was added to the mixture and the resulting product was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 25 mL). Combined organic fractions were washed with brine (3 × 25 mL), then dried over anhydrous MgSO4. Finally, products were filtered and concentrated under vacuum. Compound OB‐CAPE (5) was obtained as a yellow pale solid after flash chromatography (0 − 50% EtOAc/Hex), yield (47%, 724 mg), m.p. 174°–176°C, Rf = 0.22 (20% H/Ac).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 7.67 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H, =CHCO), 7.31–7.27 (m, 4H, Har), 7.23–7.14 (m, 2H, Har), 7.11 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Har), 6.95 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H, =CHAr), 6.80 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Har), 3.02 (s, 4H, 2 x CH2); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 175.68, 170.25, 149.04, 146.12, 143.43, 140.80, 128.84, 128.79, 126.65, 126.31, 121.89, 116.24, 115.31, 106.74, 32.71, 27.60; HRMS m/z calc. for C18H16N2O3 + (H+): 309.1234; found: 309.1224; HPLC: purity > 98%.

2.3. NCI‐60 Cell Line Screening

Compounds were tested using the NCI 60 Cell One‐Dose Screen at a single dose of 10 µM. Data are presented as relative to an untreated control condition. Full methodology is available online at: https://dtp.cancer.gov/discovery_development/nci-60/methodology.htm.

2.4. Inhibition of the Biosynthesis of Lipoxygenases Products in Transfected HEK293 Cells

Briefly, HEK293 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) cells stably transfected with either 5‐LO/FLAP (Allain et al. 2015), 12‐ or 15‐LO (Touaibia et al. 2024) were harvested using 0.25% trypsin, washed and pelleted, then resuspended in HBSS (Lonza, Walkerville, MD) containing 1.6 mM of CaCl2. Subsequently, 1 × 106 cells/mL were incubated with tested compounds at indicated concentrations or DMSO (0.1%) for 5 min at 37°C before stimulation with a mix of arachidonic acid (Nu‐Chek Prep) (10 µM for 5‐LO, or 1 µM for 12‐ and 15‐LO) and 10 µM of A23187 calcium ionophore (Abcam). After 15 min, stimulation was stopped by the addition of 0.5 volumes of cold MeOH/ACN (1:1) containing 200 ng/mL each of prostaglandin B2 (PGB2; Cayman Chemicals) and 19‐OH PGB2 (Cayman Chemicals) as internal standards for reverse‐phase high pressure liquid chromatography (RP‐HPLC). Samples were kept at ‐20°C until preparation for HPLC analysis of LO products. HPLC analysis was undertaken as described previously with modifications to the analytical system (Hébert et al. 2023; Robichaud et al. 2016). 5‐LO products analyzed were the sum of LTB4, its trans‐isomers and 5‐hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5‐HETE). 12‐HETE and 15‐HETE were analyzed as 12‐LO and 15‐LO products, respectively.

2.5. Isolation of PMNL From Whole Blood

Whole blood was obtained from healthy volunteers, and heparinized blood was subsequently centrifuged at 275 x g for 15 min at room temperature. Plasma was collected, and following dextran sedimentation, erythrocytes were removed. The remaining cells were separated using a lymphocyte separation medium (density: 1.077 g/mL; Wisent, St‐Bruno, QC), following centrifugation at 800 x g for 20 min at room temperature. PMNL were then obtained following hypotonic lysis of remaining erythrocytes.

2.6. Inhibition of the Biosynthesis of 5‐LO Products in PMNL

Isolated PMNL were resuspended (5 × 106 cells/mL) in HBSS (Lonza, Walkerville, MD) containing 1.6 mM CaCl2 and 0.3 U/mL adenosine deaminase (Sigma‐Aldrich, Oakville, ON), then pre‐incubated at 37°C for 10 min before stimulation (Hébert et al. 2023). Compounds, or DMSO as control, were added to PMNL at indicated concentrations, and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. PMNL were then stimulated using 1 µM thapsigargin (Sigma‐Aldrich) for 15 min. Following stimulation, the reaction was stopped via addition of 0.5 volumes of cold MeOH/ACN (1:1) containing an internal standard of 50 ng of 19‐OH‐PGB2. Samples were subsequently stored at ‐20°C until preparation for RP‐HPLC. HPLC analysis was done as described above, and 5‐LO products analyzed from PMNL were LTB4, its trans isomers, 20‐OH‐LTB4, 20‐COOH‐LTB4, and 5‐HETE.

2.7. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking with 5‐LO (3O8Y) (Gilbert et al. 2011) was conducted following a previously described protocol (Touaibia et al. 2024) using AutoDock Vina (Trott et Olson 2010). All grid parameters for the docking are included in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Parameters used for the molecular docking of studied compounds.

| Protein | PDB ID | Grid center (x, y, z) | Grid size (x, y, z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5‐LO | 3O8Y | 4.049, 21.346, ‐0.284 | 30, 20, 30 |

2.8. Prediction of Physicochemical Properties and Evaluation of Drug‐Likeness

The SwissADME (Daina, Michielin, et Zoete 2017) web tool was used to assess the physicochemical properties of OB‐CAPE (5), CAPE (1) and Zil (3). Subsequently, results were filtered based on the Lipinski rule of five, to estimate the potential bioavailability and drug likeness of compounds (Lipinski et al. 2001).

2.9. Antioxidant Activity of Compounds

Antioxidant activity of CAPE and its bioisostere was determined via the 2,2′‐azobis (2‐amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) assay for oxidation of linoleic acid (Hébert et al. 2023). Tested compounds or DMSO (0.1%) as control were suspended in PBS (Corning; 21‐040‐CV) containing 0.16 mM of linoleic acid (Cayman Chemical, 90150‐1) and Tween®20 (VWR, 0777‐1 L). Addition of 2 mM AAPH (AAPH·2HCl; Sigma‐Aldrich, 440914‐25 G) suspended in PBS to the mixture in a UV‐transparent flat bottom 96‐well plate allowed the start of the oxidation reaction of linoleic acid. A control condition containing DMSO and linoleic acid, but without AAPH, allowed for matrix subtraction. The absorbance values of each sample were measured at intervals of 5 min over a 3‐h period by a UV plate reader set at 234 nm (Biotek Synergy H1 Hybrid Microplate Reader). Sample compartment was set at 37°C with constant shaking, and antioxidant activities of compounds were measured using a slope rate of the measured UV signal. Values of 100% denote good antioxidant activity, whereas values near 0% denote mediocre antioxidant activity. Values were calculated using formula:

2.10. Iron Chelation Assays

Stock solutions for each compound were prepared at a concentration of 500 µM in PBS at pH 7.4 (Corning) and incubated for 30 min in the presence of Fe (III) citrate (Sigma‐Aldrich) at various concentrations. Samples were subsequently analyzed by UV‐Vis spectroscopy via a Genesys 10S UV‐Vis spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, US) as described previously (Shao et al. 2020, 2021).

2.11. Stability of Compounds in Human Plasma

Whole blood was obtained from healthy volunteers, and plasma was collected as described above. Platelet‐free plasma was then obtained following centrifugation at 1300 x g at room temperature for 20 min and was stored at ‐20°C (Hébert et al. 2023) until use. In stability assays plasma was pre‐incubated at 37°C. CAPE or its bioisostere, or DMSO to monitor plasma background, were then added to plasma at the indicated concentrations in a total volume of 2 mL. At the indicated times 100 µL of plasma containing the compounds or DMSO were added to 900 µL of stop solution containing MeOH/ACN (1:1) and an internal standard of 100 ng of 19‐OH‐PGB2. Samples were stored at ‐20°C overnight. Compound stability was assessed using the identical HPLC protocol as that described above for lipoxygenase product analysis, with the addition of 325 nm and 345 nm analysis wavelengths for the measurements of CAPE and OB‐CAPE, respectively. The λmax of tested compounds were determined beforehand to be 325 nm for CAPE and 345 nm for its bioisostere.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of OB‐CAPE (5)

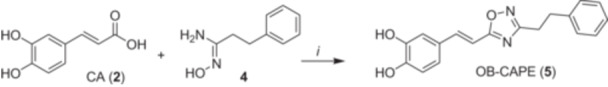

Bioisostere OB‐CAPE (5) bearing the 1,2,4‐oxadiazole heterocycle was obtained as shown in Scheme 1. N′‐hydroxy‐3‐phenylpropanamidine 4 (Cai et al. 2016), obtained from phenylpropionitrile, reacted with CA (2) and N,N,N′,N′‐tetramethyl‐O‐ (1H‐benzotriazol‐1‐yl)‐uronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) as a carboxylic acid activating agent to obtain OB‐CAPE (5).

SCHEME 1.

Synthesis of compound OB‐CAPE (5). i) HBTU, DIEA, DMF, rt, 24 h.

3.2. Anticancer Activity

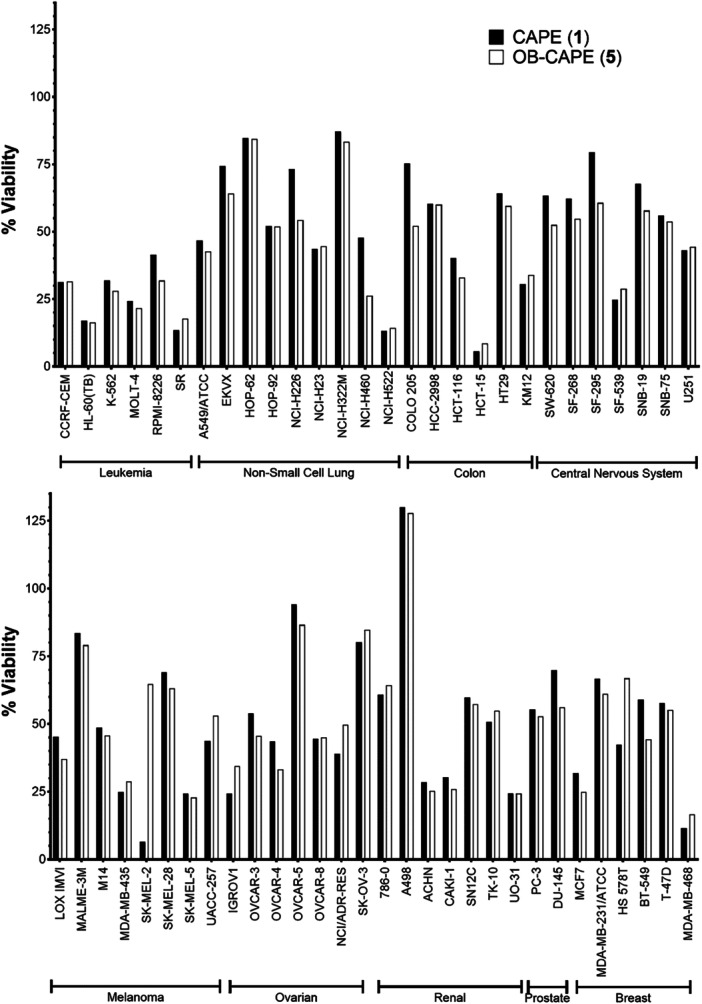

To assess and compare the antiproliferative activity of CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5), the NCI‐60 cancer cell lines screening was performed and analyzed as described previously (Yan et al. 2022) (see Figures S1 and S2). CAPE (1) and its derivatives are well established antitumor agents, having shown anticancer activity in several cancer models, notably multiple myeloma, breast cancer and glioblastoma (Beauregard et al. 2015; Morin et al. 2017; Murugesan et al. 2020). CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) showed similar effects on cell viability in most cell lines, with particularly notable effects on leukemia cell lines (Figure 2). Both compounds were generally less effective against most lung, central nervous system, ovarian, renal and prostate cancer cell lines. Furthermore, when results are broken down within individual cell lines, CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) exhibit at least modest growth inhibition on all cell lines apart from A498 renal cancer cells, which showed a growth increase to 130.0% and 127.8%, respectively. Despite this, past studies have found that propolis extracts are effective against the A498 cell line, supporting a role for other naturally occurring compounds, or their combination, in the treatment of renal cancer (Freitas et al. 2022; Valente et al. 2011). Only the SK‐MEL‐2 melanoma cell line showed a noticeable difference between the two compounds, with 6.6% of cells treated with CAPE (1) remaining viable compared to 64.7% with OB‐CAPE (5). Overall, these results suggest that, in general, the substitution of the ester function for an oxadiazole has little consequence on the antiproliferative activity of CAPE (1).

FIGURE 2.

NCI60 Cancer cell score of CAPE (1) or OB‐CAPE (5) after exposure to a single dose (10 µM) of each compound compared to an untreated control. For each cancer cell line, viability results are presented as mean values of duplicate analyses.

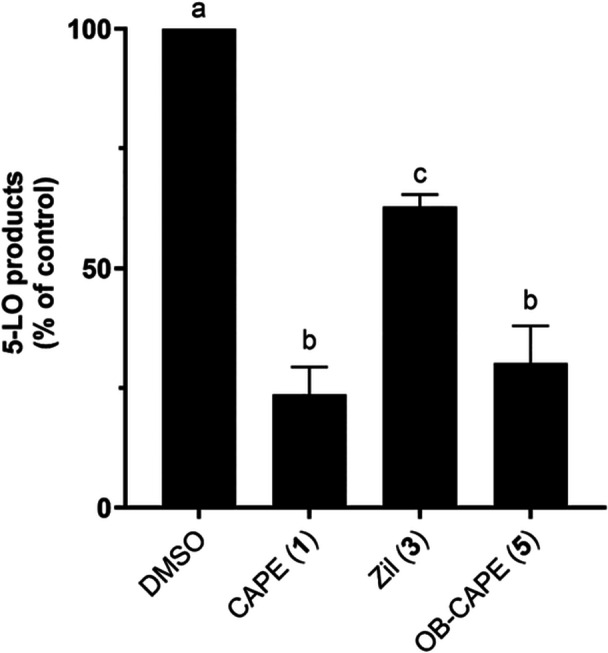

3.3. Inhibition of the Biosynthesis of Lipoxygenase Products

CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) were tested and compared for their effects on the biosynthesis of 5‐, 12‐ and 15‐lipoxygenase products in cellular assays (Allain et al. 2015; Touaibia et al. 2024). For 5‐LO, Zileuton (Zil; 3) was used as positive control, whereas for 12‐ and 15‐LO, Baicalein, a natural product shown to inhibit platelet lipoxygenase (Sekiya et Okuda 1982), was used as positive control. Figure 3 shows the comparison between the activities of Zil (3), CAPE (1) and its bioisostere OB‐CAPE (5) on the biosynthesis of 5‐LO products in HEK293 cells stably transfected with 5‐LO and 5‐lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP) (Allain et al. 2015). CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) were more potent than Zil (3), with a remaining relative production of 5‐LO products of 23.7% and 30.2% for CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5), respectively, at a concentration of 1 µM.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of the biosynthesis of 5‐LO products by Zil (3), CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) (1 μM) in HEK293 cells transfected with 5‐LO/FLAP. Values are the means ± SD of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. The graph shows values that are normalized to diluent (DMSO) controls. Values without at least one common superscript letter are significantly different (p < 0.05) as determined by two‐way ANOVA of the non‐normalized data with subsequent Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

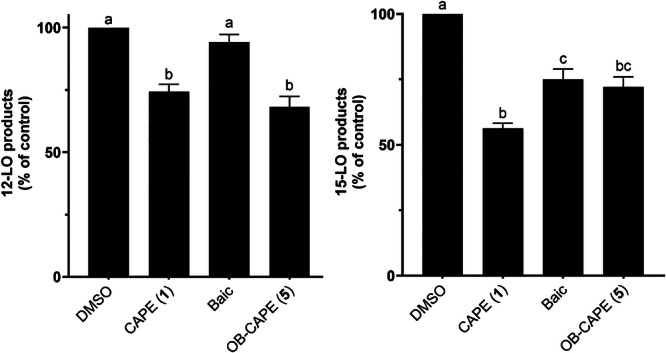

When HEK293 cells stably transfected with 12‐LO were incubated with CAPE (1), OB‐CAPE (5) or Baic, both CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) were more potent inhibitors of the biosynthesis of the 12‐LO product, 12‐hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (12‐HETE), than Baic. The was no difference in inhibitory activity between the two test compounds, with a remaining relative production of 12‐HETE of 74.3% and 68.2% for CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5), respectively, (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of the biosynthesis of 12‐LO (left) and 15‐LO (right) products by Baic, CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) (1 μM) in 12‐LO and 15‐LO transfected HEK293 cells. Values are the means ± SD of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. The graph shows values that are normalized to diluent (DMSO) controls. Values without at least one common superscript letter are significantly different (p < 0.05) as determined by two‐way ANOVA of the non‐normalized data with subsequent Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

The effect of CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) on the biosynthesis the 15‐LO product, 15‐HETE, in HEK293 cells stably transfected with 15‐LO, still in comparison to Baic, is also shown in Figure 4. The test compounds showed similar significant inhibitory activity for the biosynthesis of 15‐HETE, with no statistical differences between CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5), although only CAPE (1) was statistically different from Baic.

These results show that there are no statistical differences between the behaviors of CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) towards 5‐, 12‐ and 15‐LO, further supporting that these compounds have similar biological properties, and both are more selective towards 5‐LO than 12‐ or 15‐LO. As such, these results support that the substitution of the ester function within CAPE (1) with an oxadiazole does not affect the capacity of the compound to impact the biosynthesis of LO products. This is not surprising, as the functional group most involved in the inhibition of lipoxygenases is likely the catechol ring, since other natural products shown to inhibit the biosynthesis of lipoxygenases, such as NDGA, contain at least one catechol ring within their structure (Ford‐Hutchinson et al. 1994; Kemal et al. 1987). The role of the phenethyl moiety of CAPE is likely to provide hydrophobicity that improves its capacity to enter the cell and to interact with the active site of the enzyme.

To further support the results obtained from the LO‐mediated biosynthesis assays in HEK293 cells, compounds were tested for the inhibition of the biosynthesis of 5‐LO in PMNL isolated from human peripheral blood. IC50 results showed that CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) possessed similar activity as inhibitors of the biosynthesis of 5‐LO products in PMNL (Table 2). Both compounds were approximately threefold more potent than Zil (3). These results further suggest that OB‐CAPE (5) is an adequate bioisostere of CAPE (1), possessing similar affinities towards lipoxygenase activity in human cells. This, in turn, highlights a potential anti‐inflammatory role for this compound.

TABLE 2.

IC50 values for the inhibition of the biosynthesis of 5‐LO products in PMNL.

| IC50 (µM) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| OB‐CAPE (5) | 0.93 (0.86–1.0) |

| CAPE (1) | 1.0 (0.98–1.1) |

| Zil (3) | 2.9 (2.6–3.3) |

Note: Values are means of four independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

3.4. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5)

As a member of the polyphenol class of molecules, CAPE (1) was shown to possess significant antioxidant and antiradical activity across numerous assays (Göçer and Gülçin 2011; Hébert et al. 2023; Sud'ina et al. 1993). In a biological setting, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are critical mediators that promote both tumorigenic and inflammatory responses including lung diseases such as asthma (Barnes 1990; Moloney and Cotter 2018; Nakamura et Takada 2021; Paola and Salvatore 2012). To continue the comparison of the properties of CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5), the AAPH antioxidant assay was performed. Both CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) possessed a similar IC50 for the inhibition of linoleic acid peroxidation in the AAPH assay, at 1.1 and 1.2 µM, respectively (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

IC50 values of the antioxidant activity in the AAPH assay.

| IC50 (µM, 95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| OB‐CAPE (5) | 1.2 (0.99–1.5) |

| CAPE (1) | 1.1 (0.99–1.3) |

Note: Means of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

These results suggest a correlation between the antioxidant properties of both compounds with their observed properties against both cancer cell proliferation and lipoxygenase biosynthetic activity.

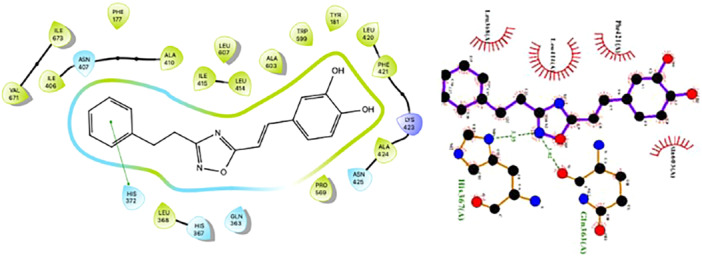

3.5. Molecular Docking

To better understand whether the substitution of the ester bond with a 1,2,4‐Oxadiazole impacts on the affinity of CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) towards 5‐LO, molecular docking experiments were performed with the stable human 5‐LO protein (PDB ID: 3O8Y) (Gilbert et al. 2011). Based on binding energy (BE), both CAPE (1) (BE: ‐8.8 kcal/mol) and OB‐CAPE (5) (BE: ‐9.6 kcal/mol) show more affinity towards 5‐LO when compared to Zil (3) R‐enantiomer (BE: ‐6.7 kcal/mol) and Zil (3) S‐enantiomer (BE: ‐6.5 kcal/mol) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Docking results for CAPE (1), OB‐CAPE (5), and Zileuton (3).

| Compound | Binding energy (BE) (kcal/mol) | π‐π interactionsa | H‐Bonds (Laskowski et Swindells 2011) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAPE (1) | –8.8 | His372 | Leu420 |

| OB‐CAPE (5) | –9.6 | His372 | Gln363 |

| R‐Zil (3) | –6.7 | Phe421 | Leu420 x 2, Asn425 |

| S‐Zil (3) | –6.5 | ‐‐‐ | Leu420 x 2, Ala424, Phe421 |

Schrödinger Release 2019‐2: Maestro, Schrödinger; LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

Interestingly, both CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) possess π‐π interactions with His372 of 5‐LO, although OB‐CAPE (5) has a slightly lower binding energy than CAPE (1). Both compounds form hydrogen bonds within the 5‐LO active site, with CAPE (1) interacting with Leu420 via one of its hydroxyl groups, the same amino acid with which both Zil (3) enantiomers interact, whereas OB‐CAPE (5) interacts with Gln363 via one of the nitrogen atoms within its oxadiazole ring. The interaction of one of the two nitrogen atoms of the heterocycle with the nitrogen of the His367 residue of the enzyme's active site may also explain the increased affinity of OB‐CAPE (5) for 5‐LO compared to CAPE (1). A visualization of OB‐CAPE (5) in the 5‐LO active site is presented in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

π‐π interactions (left) and H bond (right) of OB‐CAPE (5) with Gln363 amino acid within the 5‐LO active site.

3.6. Predicted Physicochemical Properties of OB‐CAPE (5)

In silico evaluation of the physicochemical properties of OB‐CAPE (5) are presented in Table 5. OB‐CAPE (5) respects Lipinski's rule of five (Lipinski et al. 2001), indicating favorable drug‐likeness, and is mostly comparable to CAPE (1), possessing one less rotatable bond, but one more hydrogen bond acceptor. Interestingly, the number of hydrogen bond donors is identical between CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5), and there is negligible difference between calculated lipophilicities of the two compounds.

TABLE 5.

Physicochemical properties and partition coefficients of studied compounds.

| Physicochemical properties a | Lipophilicity a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW | n‐ROTB | n‐HBA | n‐HBD | CLogPo/w | |

| Rule | 500 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| OB‐CAPE (5) | 308.33 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3.09 |

| CAPE (1) | 284.31 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 3.08 |

| Zileuton (3) | 236.29 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1.81 |

Abbreviations: CLog Po/w, logarithm of compound partition coefficient between n‐octanol and water; MW, molecular weight (g/mol); n‐HBA, number of hydrogen bonds acceptors; n‐HBD, number of hydrogen bond donors; n‐ROTB, number of rotatable bonds.

SwissADME (Daina et al. 2017).

These striking similarities support the observed biological effects of OB‐CAPE (5) when compared to CAPE (1) and explain why both compounds react in largely the same manner in all biological assays. Furthermore, the increased lipophilicity of both compounds compared to Zil (3) may further explain why both are more effective 5‐LO inhibitors in vitro, as the increased lipophilicity of CAPE (1), especially compared to CA (2), has been correlated with its higher affinity towards intracellular iron atoms (Shao et al. 2021).

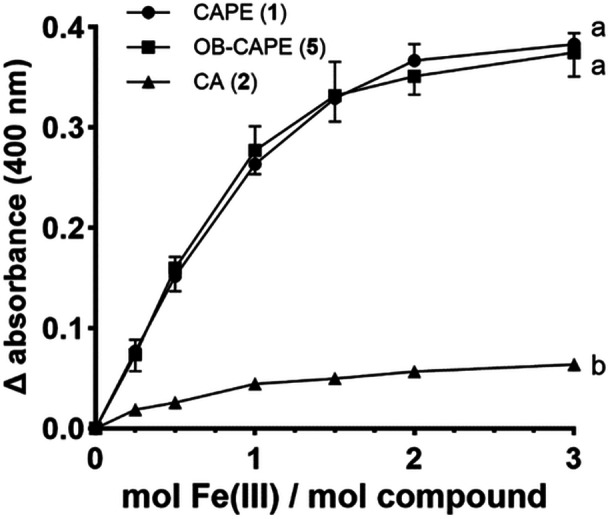

3.7. Iron Chelation Assays

To further characterize any differences or similarities between CAPE (1) and OB‐CAPE (5) that may be related to their modes of action, in vitro iron chelation assays against Fe (III) were undertaken and measured by UV‐visible spectroscopy. Fe (III) is the active form of the central nonheme iron within LO enzymes, which catalyzes the peroxidation reaction of arachidonic acid leading to the eventual formation of lipid mediators (Solomon et al. 1997; Wisastra et Dekker 2014). Catechol rings, such as the one found in CAPE (1), were reported to chelate Fe (III) ions and reduce them to Fe (II) via a redox cycle in in vitro assays (Kemal et al. 1987; Nelson 1988). It was previously demonstrated that the catechol ring was vital for the activity of CAPE (1), as a substitution with a benzene ring resulted in the loss of activity towards 5‐LO (Boudreau et al. 2012). As mentioned above, recent advances have also demonstrated that CAPE (1) is a stronger chelator than CA (2) in biological settings, which is thought to be in part due to its increased lipophilicity, allowing it to cross cell membranes to a greater extent (Shao et al. 2020, 2021).

The affinity of CA (2) towards Fe (III) citrate showed a gradual hyperchromic shift which can be observed with each incremental increase in concentration of Fe (III), suggesting the formation of a complex between CA (2) and Fe (III) ions (See Figure S3). A hyperchromic shift can be observed around 400 nm when CAPE (1) is exposed to different concentrations of Fe (III), clearly showing the formation of a new complex (See Figure S4). Similar results were obtained when OB‐CAPE (5) was exposed to increasing concentrations of Fe (III), and a hyperchromic shift was also observed near 400 nm (See Figure S5). Figure 6 shows the adjusted absorbance values of each compound at 400 nm with increasing Fe (III)/compound ratios.

FIGURE 6.

Absorbance ratios of compounds and Fe (III) adjusted to background signal of each respective compound at 400 nm. Data are represented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. For clarity, error bars for CAPE point upwards, whereas error bars for OB‐CAPE point downwards. Variation was small in CA samples, such that no error bars were generated. Two‐way ANOVA analysis with Tukey's multiple comparisons test was performed; curves that do not share a common letter are considered statistically different (p < 0.0001).

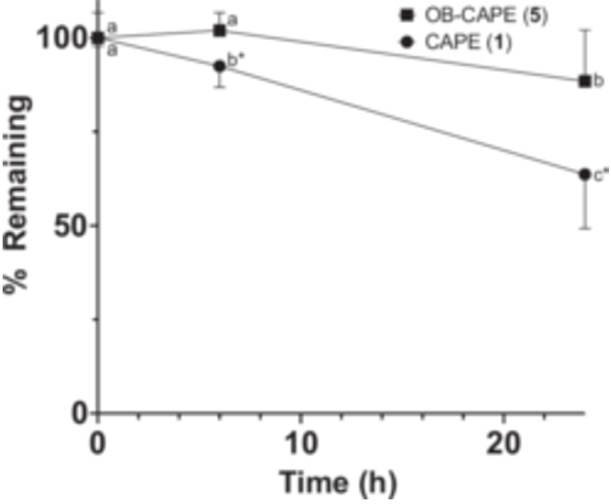

3.8. Stability in Human Plasma

Finally, as CAPE (1) was previously found to be rapidly degraded in rat plasma (Wang et al. 2007), we sought to compare the stability of CAPE (1) and whether OB‐CAPE (5) in human plasma. There are a few differences between human and rat plasma, the most notable being the presence of highly active carboxylesterases in rat plasma, but not in human plasma (Bahar et al. 2012). As such, it is not surprising that the few studies performed on both models showed that CAPE (1) was less stable in rat plasma than in human plasma, and that CA (2) appeared to be the major metabolite in the former (Celli et al. 2007). However, CA (2) was also detected as a product of CAPE (1) metabolism following incubation with HT‐29 colon cancer cells (Tang et al. 2017) suggesting that the labile nature of ester linkage in a biological setting may hinder the usefulness of CAPE. Our results in human plasma (Figure 7) demonstrate that OB‐CAPE (5) is more stable than CAPE (1) after 24 h incubations in human plasma, with average remaining concentrations of 88.4% and 63.7%, respectively.

FIGURE 7.

Stability of compounds in human plasma. Data are presented as the means ± SD of four independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. A 5 µM dose of each compound was incubated with human plasma for up to 24 h. Following 2‐way repeated measures ANOVA analyses, there were significant effects of time (F (2, 6) = 8.135; p = 0.02), compounds (F (1, 3) = 57.32; p = 0.005) and their interaction (F (2, 6) = 58.21; p = 0.0001). At different time points, values without common superscripts within compounds are considered statistically significant, and values with an asterisk * are different from OB‐CAPE (5) at the same time point as determined using Tukey's multiple comparisons test (p < 0.05).

These results suggest that while the ester is mostly the targeted moiety in this setting, there are other mechanisms involved in the degradation or modification of CAPE (1) in human plasma, likely involving the catechol ring. This is based on other observations on the metabolism of CAPE (1), which found that the catechol ring is prone to glucuronidation in both HT‐29 cancer cells and HepaRG hepatocyte models (Mbarik et al. 2019; Tang et al. 2017). Future in vivo experiments are warranted to determine whether OB‐CAPE (5) may be a more effective therapeutic candidate than CAPE (1) based on its equivalent biological activity and apparent enhanced stability.

4. Conclusions

Newly synthetized 1,2,4‐oxadiazole bioisostere OB‐CAPE (5) and CAPE (1) showed nearly identical antiproliferative activity when tested against various cancer cell models, three different human lipoxygenases in cell‐based assays, as well as antioxidant and iron chelation assays. Molecular modeling and evaluation of in silico properties support a similar mode of action, with both molecules possessing very similar physicochemical properties and interactions within the 5‐LO active site. However, OB‐CAPE (5) was more stable in human plasma than CAPE (1), supporting its potential as a suitable candidate for further in vivo studies in disease models.

Author Contributions

Mika A. Robichaud: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review, visualization. Audrey Isabel Chiasson: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review, visualization. Jérémie A. Doiron: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing – review, visualization. Mathieu P.A. Hébert: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation visualization. Marc E. Surette: conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. Mohamed Touaibia: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Robichaud et al Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

M.T. acknowledges the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and Université de Moncton. M.E.S. acknowledges the support of the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation and the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the publication.

References

- Allain, E. P. , Boudreau L. H., Flamand N., and Surette M. E.. 2015. “The Intracellular Localisation and Phosphorylation Profile of the Human 5‐Lipoxygenase Δ13 Isoform Differs From That of Its Full Length Counterpart.” PLoS One 10, no. 7: e0132607. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar, F. G. , Ohura K., Ogihara T., and Imai T.. 2012. “Species Difference of Esterase Expression and Hydrolase Activity in Plasma.” Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 101, no. 10: 3979–3988. 10.1002/jps.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, P. J. 1990. “Reactive Oxygen Species and Airway Inflammation.” Free Radical Biology and Medicine 9, no. 3: 235–243. 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90034-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard, A. P. , Harquail J., Lassalle‐Claux G., et al. 2015. “CAPE Analogs Induce Growth Arrest and Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells.” Molecules 20, no. 7: 12576–12589. 10.3390/molecules200712576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaard, H. 2001. “Pathophysiology of the Cysteinyl Leukotrienes and Effects of Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists in Asthma.” Allergy 56, no. s66: 7–11. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.56.s66.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, L. H. , Maillet J., and LeBlanc L. M., et al. 2012. “Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester and Its Amide Analogue Are Potent Inhibitors of Leukotriene Biosynthesis in Human Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes.” PLoS One 7, no. 2: e31833. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H. , Huang X., Xu S., et al. 2016. “Discovery of Novel Hybrids of Diaryl‐1,2,4‐Triazoles and Caffeic Acid as Dual Inhibitors of Cyclooxygenase‐2 and 5‐Lipoxygenase for Cancer Therapy.” European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 108: 89–103. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, W. J. 1998. “Summary of Clinical Trials With Zafirlukast.” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 157, no. 6: S238–S246. 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.mar6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camci, M. , and Karali N.. 2023. “Bioisosterism: 1,2,4‐Oxadiazole Rings.” ChemMedChem 18, no. 9: e202200638. 10.1002/cmdc.202200638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli, N. , Dragani L. K., Murzilli S., Pagliani T., and Poggi A.. 2007. “In Vitro and in Vivo Stability of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester, a Bioactive Compound of Propolis.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55, no. 9: 3398–3407. 10.1021/jf063477o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina, A. , Michielin O., and Zoete V.. 2017. “SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug‐Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules.” Scientific Reports 7, no. 1: 42717. 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folcik, V. A. , Nivar‐Aristy R. A., Krajewski L. P., and Cathcart M. K.. 1995. “Lipoxygenase Contributes to the Oxidation of Lipids in Human Atherosclerotic Plaques.” Journal of Clinical Investigation 96, no. 1: 504–510. 10.1172/JCI118062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford‐Hutchinson, A. W. , Gresser M., and Young R. N.. 1994. “5‐LIPOXYGENASE.” Annual Review of Biochemistry 63, no. 1: 383–417. 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, A. S. , Costa M., Pontes O., et al. 2022. “Selective Cytotoxicity of Portuguese Propolis Ethyl Acetate Fraction Towards Renal Cancer Cells.” Molecules 27, no. 13: 4001. 10.3390/molecules27134001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, N. C. , Bartlett S. G., Waight M. T., et al. 2011. “The Structure of Human 5‐Lipoxygenase.” Science 331, no. 6014: 217–219. 10.1126/science.1197203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göçer, H. , and Gülçin İ.. 2011. “Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester (CAPE): Correlation of Structure and Antioxidant Properties.” International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 62, no. 8: 821–825. 10.3109/09637486.2011.585963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeggström, J. Z. , and Funk C. D.. 2011. “Lipoxygenase and Leukotriene Pathways: Biochemistry, Biology, and Roles in Disease.” Chemical Reviews 111, no. 10: 5866–5898. 10.1021/cr200246d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert, M. P. A. , Selka A., Lebel A. A., et al. 2023. “Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Analogues as Selective Inhibitors of 12‐Lipoxygenase Product Biosynthesis in Human Platelets.” International Immunopharmacology 121: 110419. 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, W. R. 1994. “The Role of Leukotrienes in Inflammation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 121, no. 9: 684–697. 10.7326/0003-4819-121-9-199411010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomovic, M. D. , Abrahamson E. E., Uz T., Manev H., and Dekosky S. T.. 2008. “Increased 5‐Lipoxygenase Immunoreactivity in the Hippocampus of Patients With Alzheimer's Disease.” The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry: Official Journal of the Histochemistry Society 56, no. 12: 1065–1073. 10.1369/jhc.2008.951855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, E. M. , Heasley B. H., Chordia M. D., and Macdonald T. L.. 2004. “In Vitro Metabolism of 2‐Acetylbenzothiophene: Relevance to Zileuton Hepatotoxicity.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 17, no. 2: 137–143. 10.1021/tx0341409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemal, C. , Louis‐Flamberg P., Krupinski‐Olsen R., and Shorter A. L.. 1987. “Reductive Inactivation of Soybean Lipoxygenase 1 by Catechols: A Possible Mechanism for Regulation of Lipoxygenase Activity.” Biochemistry 26, no. 22: 7064–7072. 10.1021/bi00396a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, H. , Banthiya S., and van Leyen K.. 2015. “Mammalian Lipoxygenases and Their Biological Relevance.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) ‐ Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1851, no. 4: 308–330. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R. A. , and Swindells M. B.. 2011. “LigPlot+: Multiple Ligand–Protein Interaction Diagrams for Drug Discovery.” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 51, no. 10: 2778–2786. 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski, C. A. , Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., and Feeney P. J.. 2001. “Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings.” Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 46, no. 1–3: 3–26. 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P. , Schrag M. L., Slaughter D. E., Raab C. E., Shou M., and Rodrigues A. D.. 2003. “Mechanism‐Based Inhibition of Human Liver Microsomal Cytochrome P450 1A2 by Zileuton, a 5‐lipoxygenase Inhibitor.” Drug Metabolism and Disposition 31, no. 11: 1352–1360. 10.1124/dmd.31.11.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbarik, M. , Poirier S. J., Doiron J., et al. 2019. “Phenolic Acid Phenethylesters and Their Corresponding Ketones: Inhibition of 5‐lipoxygenase and Stability in Human Blood and HepaRG Cells.” Pharmacology Research & Perspectives 7, no. 5: e00524. 10.1002/prp2.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moloney, J. N. , and Cotter T. G.. 2018. “ROS Signalling in the Biology of Cancer.” Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 80: 50–64. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin, P. , St‐Coeur P. D., Doiron J., et al. 2017. “Substituted Caffeic and Ferulic Acid Phenethyl Esters: Synthesis, Leukotrienes Biosynthesis Inhibition, and Cytotoxic Activity.” Molecules 22, no. 7: 1124. 10.3390/molecules22071124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan, A. , Lassalle‐Claux G., Hogan L., et al. 2020. “Antimyeloma Potential of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester and Its Analogues Through Sp1 Mediated Downregulation of IKZF1‐IRF4‐MYC Axis.” Journal of Natural Products 83, no. 12: 3526–3535. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, H. , and Takada K.. 2021. “Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer: Current Findings and Future Directions.” Cancer Science 112, no. 10: 3945–3952. 10.1111/cas.15068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, R. 1999. “Evidence for 12‐lipoxygenase Induction in the Vessel Wall Following Balloon Injury.” Cardiovascular Research 41, no. 2: 489–499. 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, M. J. 1988. “Catecholate Complexes of Ferric Soybean Lipoxygenase 1.” Biochemistry 27, no. 12: 4273–4278. 10.1021/bi00412a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paola Rosanna, D. , and Salvatore C.. 2012. “Reactive Oxygen Species, Inflammation, and Lung Diseases.” Current Pharmaceutical Design 18, no. 26: 3889–3900. 10.2174/138161212802083716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patani, G. A. , and LaVoie E. J.. 1996. “Bioisosterism: A Rational Approach in Drug Design.” Chemical Reviews 96, no. 8: 3147–3176. 10.1021/cr950066q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters‐Golden, M. , and Henderson W. R.. 2007. “Leukotrienes.” New England Journal of Medicine 357, no. 18: 1841–1854. 10.1056/NEJMra071371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robichaud, P. P. , Poirier S. J., Boudreau L. H., et al. 2016. “On the Cellular Metabolism of the Click Chemistry Probe 19‐Alkyne Arachidonic Acid.” Journal of Lipid Research 57, no. 10: 1821–1830. 10.1194/jlr.M067637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong, S. , Cao Q., Liu M., et al. 2012. “Macrophage 12/15 Lipoxygenase Expression Increases Plasma and Hepatic Lipid Levels and Exacerbates Atherosclerosis.” Journal of Lipid Research 53, no. 4: 686–695. 10.1194/jlr.M022723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A. , Longo R., and Vanella A.. 2002. “Antioxidant Activity of Propolis: Role of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester and Galangin.” Fitoterapia 73: S21–S29. 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya, K. , and Okuda H.. 1982. “Selective Inhibition of Platelet Lipoxygenase by Baicalein.” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 105, no. 3: 1090–1095. 10.1016/0006-291X(82)91081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao, B. , Mao L., Shao J., et al. 2020. “Mechanism of Synergistic DNA Damage Induced by Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester (CAPE) and Cu (II): Competitive Binding Between CAPE and DNA With Cu (II)/Cu (I).” Free Radical Biology and Medicine 159: 107–118. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao, B. , Mao L., Tang M., et al. 2021. “Caffeic Acid Phenyl Ester (CAPE) Protects Against Iron‐Mediated Cellular DNA Damage Through Its Strong Iron‐Binding Ability and High Lipophilicity.” Antioxidants 10, no. 5: 798. 10.3390/antiox10050798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S. H. , Lee S. R., Lee E., Kim K. H., et al. 2017. “Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester From the Twigs of Cinnamomum cassia Inhibits Malignant Cell Transformation by Inducing c‐Fos Degradation.” Journal of Natural Products 80, no. 7: 2124–2130. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, E. I. , Zhou J., Neese F., and Pavel E. G.. 1997. “New Insights From Spectroscopy Into the Structure/Function Relationships of Lipoxygenases.” Chemistry & Biology 4, no. 11: 795–808. 10.1016/S1074-5521(97)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sud'ina, G. F. , Mirzoeva O. K., Pushkareva M. A., Korshunova G. A., Sumbatyan N. V., and Varfolomeev S. D.. 1993. “Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester as a Lipoxygenase Inhibitor With Antioxidant Properties.” FEBS Letters 329, no. 1–2: 21–24. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80184-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H. , Yao X., Yao C., Zhao X., Zuo H., and Li Z.. 2017. “Anti‐Colon Cancer Effect of Caffeic Acid p‐Nitro‐Phenethyl Ester In Vitro and In Vivo and Detection of Its Metabolites.” Scientific Reports 7, no. 1: 7599. 10.1038/s41598-017-07953-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touaibia, M. , Chiasson A. I., Robichaud S., Doiron J. A., Hébert M. P. A., and Surette M. E.. 2024. “Single and Multiple Inhibitors of the Biosynthesis of 5‐, 12‐, 15‐lipoxygenase Products Derived From Cinnamyl‐3,4‐dihydroxy‐α‐cyanocinnamate: Synthesis and Structure–Activity Relationship.” Drug Development Research 85, no. 3: e22181. 10.1002/ddr.22181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touaibia, M. , Faye D. C., Doiron J. A., et al. 2022. “Structure–Activity Relationship Studies of New Sinapic Acid Phenethyl Ester Analogues Targeting the Biosynthesis of 5‐Lipoxygenase Products: The Role of Phenolic Moiety, Ester Function, and Bioisosterism.” Journal of Natural Products 85, no. 1: 225–236. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott, O. , and Olson A. J.. 2010. “AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking With a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading.” Journal of Computational Chemistry 31, no. 2: 455–461. 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente, M. J. , Baltazar A. F., Henrique R., Estevinho L., and Carvalho M.. 2011. “Biological Activities of Portuguese Propolis: Protection Against Free Radical‐Induced Erythrocyte Damage and Inhibition of Human Renal Cancer Cell Growth In Vitro.” Food and Chemical Toxicology 49, no. 1: 86–92. 10.1016/j.fct.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Bowman P. D., Kerwin S. M., and Stavchansky S.. 2007. “Stability of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester and Its Fluorinated Derivative in Rat Plasma.” Biomedical Chromatography 21, no. 4: 343–350. 10.1002/bmc.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, C. D. , Gundel R. H., Abraham W. M., et al. 1993. “The Role of 5‐Lipoxygenase Products in Preclinical Models of Asthma.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 91, no. 4: 917–929. 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90350-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisastra, R. , and Dekker F.. 2014. “Inflammation, Cancer and Oxidative Lipoxygenase Activity Are Intimately Linked.” Cancers 6, no. 3: 1500–1521. 10.3390/cancers6031500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, V. C. , Pham C. D., Ballato E. S., et al. 2022. “Prodrugs of a 1‐Hydroxy‐2‐Oxopiperidin‐3‐Yl Phosphonate Enolase Inhibitor for the Treatment of ENO1 ‐Deleted Cancers.” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 65, no. 20: 13813–13832. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y. , Su Y., Liu W., et al. 2022. “Design and Synthesis of Caffeic Acid Derivatives and Evaluation of Their Inhibitory Activity Against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa.” Medicinal Chemistry Research 31, no. 1: 177–194. 10.1007/s00044-021-02810-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Robichaud et al Supplementary Material.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the publication.