Abstract

Two experiments were conducted to evaluate the effect of incremental fasting time on the gastrointestinal tract in chickens. Adult White Leghorn roosters with intact ceca were provided a nutrient-adequate corn-soybean meal diet ad libitum for 3 weeks. Prior to initiation of the experimental phase, ad libitum feed intake was recorded for 8 h and immediately after the fasting period commenced. In Experiment 1, roosters were fasted for either 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 16, or 24 h. At each time point birds were euthanized and pH in the crop, gizzard, and ceca were recorded and cecal contents were collected to measure volatile fatty acids (VFA) and select cecal microbial groups. In Experiment 2, roosters were fasted for 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 16, and 24 h and excreta were collected to determine secretory IgA (sIgA) excretion. In contrast to Experiment 1, roosters in Experiment 2 were not euthanized and thus sIgA excretion was measured within individual roosters across each time point. Experiments 1 and 2 contained 5 and 8 replicates per treatment, respectively. In Experiment 1, there was a linear increase (P < 0.05) in cecal pH as fasting length increased. Cecal VFA content was reduced (P < 0.05) by 9 to 12 h of fasting and branch-chain FA to VFA ratio increased (P < 0.05) by 6 h of fasting. There were few effects (P > 0.05) of fasting on the microbial groups in cecal contents and mucosa; however, Escherichia coli content was greater (P < 0.05) at 24 h of fasting compared with other time points. In Experiment 2, total sIgA excreted was greater (P < 0.05) at 24 h of fasting, being 1106 µg/h at 24 h compared with a mean of 419 µg/h for all other time points. In conclusion, fasting reduced cecal VFA concentrations and increased cecal pH, Escherichia coli, branched-chain FA to VFA ratio, and sIgA excretion, suggesting that fasting elicited negative effects on the gastrointestinal tract.

Key words: Fasting, Volatile fatty acids, Secretory IgA, Escherichia coli, pH

Introduction

There are a number of instances in which animals are fasted in poultry production. A molt may be induced in laying hens by withdrawing feed for 4 to 14 d, thus allowing for rejuvenation of the reproductive tract and extension of the lay cycle (Berry, 2003; Bell and Kuney, 2004; Koelkebeck et al., 2006). Utilization of feeding programs in which birds only receive feed on certain days, i.e. skip-a-day feeding programs, is a common practice used for broiler breeder pullets to maintain good flock uniformity and prevent excessive growth of the females which would subsequently reduce egg production (Bartov et al., 1988; Carneiro et al., 2019). Another common practice is to remove feed from broiler chickens for approximately 8 h or more prior to processing to reduce contamination issues and excessive waste excretion (Bilgili, 2002). A routine period of fasting of up to 8 h will also occur for chickens during the time that the lights are off each night. Although these fasting periods are important parts of poultry production, during this time the flow of nutrients through the gastrointestinal tract is disrupted, which may subsequently have negative influences on the microbiota and the ability of the bird to maintain homeostasis within the intestine.

Anderson et al. (2023) conducted a study to evaluate the effects of diet adaptation and enzyme use on true metabolizable energy in adult White Leghorn roosters. In this study, some roosters received feed ad libitum, while others were subjected to the precision-fed rooster assay. The precision-feeding assay consisted of fasting roosters for 26 h, precision-feeding (crop intubating) them with 30 g of sample, and placing them in a cage where no feed was provided for 48 h while excreta were being quantitatively collected. These authors found that roosters that were subjected to the precision-feeding assay, rather than being ad libitum-fed, had greater concentrations of Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Clostridium sensu stricto, and lower concentrations of acetate, propionate, and butyrate in the ceca. Further, Parsons et al. (2023) found that total secretory IgA (sIgA) excretion was substantially reduced from 12.5 to 2.7 mg / 24 h when roosters were fasted for 48 h instead of being precision-fed a semi-purified diet that contained 10 % casein. These studies suggest that fasting may have a negative effect on intestinal homeostasis by reducing volatile fatty acid (VFA) production in the ceca, causing shifts in the cecal microbiota, and reducing sIgA secretion. It has yet to be determined, however, the time that is required for these changes within the gastrointestinal tract to occur in response to fasting, as excreta were collected once at the end of a 48 h fast in the studies by Anderson et al. (2023) and Parsons et al. (2023).

The objective of this study was to evaluate the incremental effect of fasting on the pH in the gastrointestinal tract, select cecal microbial groups, cecal VFA concentrations, and sIgA excretion in adult Leghorn roosters.

Materials and methods

The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois (number 20131).

Diets and experimental design

Experiments 1 and 2 were conducted to determine the effect of incremental fasting length on pH, cecal VFA concentrations, select cecal microbial groups, and sIgA excretion in the gastrointestinal tract. Conventional Single Comb adult White Leghorn roosters with intact ceca were utilized in these experiments. Roosters were 150 weeks-of-age and weighed approximately 2,220 g. Roosters were housed in an environmentally controlled room in individual cages and were provided a nutritionally complete corn-soybean meal-based diet ad libitum for 3 weeks (Table 1). During this time, roosters received 16 h of light and 8 h of dark. At the end of the pre-experimental phase, feed was removed for 8 h overnight and 80 g of the same diet was provided to each bird ad libitum for 8 h. After 8 h, the remaining feed was weighed and removed, and the fasting period commenced. Roosters were fasted for a maximum of 24 h. During this time, roosters had ad libitum access to water and received 24 h of light.

Table 1.

Ingredient composition of the diet during the pre-experimental phase for Experiments 1 and 2 (as-fed basis).

| Ingredient, % | Pre-experimental diet |

|---|---|

| Corn | 76.8 |

| Soybean meal | 18.4 |

| Pork meat and bone meal | 2.5 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.00 |

| Limestone | 0.55 |

| NaCl | 0.30 |

| Vitamin mix1 | 0.20 |

| Mineral mix2 | 0.15 |

| DL-Methionine | 0.10 |

| Nutrients: | |

| AMEn, calculated kcal/kg | 3,080 |

| CP, analyzed % | 16.1 |

| Ca, analyzed % | 0.79 |

| P, analyzed % | 0.61 |

Provided per kilogram of diet: retinyl acetate, 4,400 IU; cholecalciferol, 25 µg; DL-α-tocopherol acetate, 11 IU; vitamin B12, 0.01 mg; riboflavin; 4.41 mg; d-pantothenic acid, 10 mg; niacin, 22 mg; menadione sodium bisulfate, 2.33 mg.

Provided per kilogram of diet: manganese, 75 mg from MnSO4·H2O; iron, 75 mg from FeSO4·H2O; 75 mg from ZnO; copper, 5 mg from CuSO4·5H2O; iodine, 0.75 mg from ethylene diamine dihydroiodide; selenium, 0.1 from NaSeO3.

In Experiment 1, roosters were fasted for 0 (no fasting), 3, 6, 9, 12, 16, and 24 h. Five roosters were euthanized at each time point using CO2 gas. The pH in the crop, gizzard, and ceca were measured in each rooster using a spear tip pH probe (Sensorex S175CD/BNC). A small incision was made into the crop, gizzard, and ceca and the pH probe was inserted in a manner such that the probe was in contact with digesta. Digesta were present in both the gizzard and ceca throughout the study. No feed was present in the crop of the birds after 3 h of fasting; thus, the pH of the crop after the 3 h time point in this study was indicative of the pH of the fluid present in the crop. Once pH was recorded, the ceca were then weighed and then the contents were collected using a combination of flushing and gently squeezing. After collection of cecal contents, the remaining cecal tissue was weighed to determine the total weight of cecal contents. Cecal tissue was cleaned with water and mucosa were collected by gently scraping the tissue with a microscope slide. Due to the limited amount of mucosa, samples from 2 roosters were pooled to obtain the minimum amount of sample required for analyses. Thus, there were 5 replicates of 1 individually caged rooster per treatment for all analyses in Experiment 1, excluding mucosa analyses which had 2 replicates of 2 individually caged roosters per treatment. Cecal contents and mucosa were immediately preserved using BioFreeze sampling kits (Alimetrics Diagnostics Ltd., Espoo, Finland). The microbial groups (Clostridium perfringens, Ruminococcaceae, Bifidobacterium, Lachnospiraceae, and E. coli) in cecal contents and mucosa and fatty acid profile in cecal contents (acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, lactic acid, branched-chain fatty acids (BCFA), and VFA) were then measured as described below. The BCFA measured were iso-butyric acid, 2-methyl-butyric acid, and iso-valeric acid. Both the cecal contents and cecal mucosa were collected for microbial analyses due to differences in the microbial communities that can be present in those locations due to variations in substrate availability and oxygen concentration (Chikina and Vignjevic, 2021).

In Experiment 2, roosters were fasted for 24 h and sIgA excretion was measured in the excreta. There were 8 roosters in total that were not euthanized during the trial, which was done to account for the effect of the individual bird. Excreta were quantitatively collected by placing trays beneath each cage. Collections took place from 0 to 3, 3 to 6, 6 to 9, 9 to 12, 12 to 16, and 16 to 24 h of fasting. After each collection, excreta were frozen prior to lyophilization. After lyophilization, excreta were weighed, ground, and analyzed for sIgA.

Chemical analyses

Analyzed nutrient concentrations in the diet (Table 1) were measured at the Agricultural Experiment Station Chemical Laboratory (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO). The CP was determined by measuring N via combustion (Method 990.03; AOAC International, 2007). The Ca and P were determined using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (Method 985.01 A, B, and D; AOAC Internation, 2007).

Alimetrics Diagnostics (Espoo, Finland) conducted the analyses of cecal contents and cecal mucosa for microbial groups and VFA (Kettunen et al., 2015, 2017; Whelan et al., 2019; Anderson et al., 2023; Davies et al., 2024; Itani et al., 2025). The abundance of Ruminococcaceae, Bifidobacterium, Lachnospiraceae, Clostridium perfringens, E. coli, and total bacteria were measured (Kettunen et al., 2017). Clostridium perfringens and E. coli were selected due to the previous observation that these species were elevated in the ceca of roosters after 48 h of fasting and due to their role in pathogenesis (Parish, 1961; Chapman et al., 1997; Ganas et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 2023). Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae, along with the genus Bifidobacterium, were selected because they account for a large proportion of microorganisms in the ceca of broiler chickens and because these groups contribute to acetic, propanoic, and butyric acid production (De Vuyst and Leroy, 2011; Rivière et al., 2015; Apajalahti and Vienola, 2016; Vacca et al., 2020; Rychlik, 2021). Cecal samples were collected and stored using BioFreeze sampling kits according to the manufacturers instructions (Alimetrics Diagnostics, Espoo, Finland). Samples were shaken vigorously until all material was mixed. Samples were stored at 20°C and were received by Alimetrics within 1 week after sample collection. After samples were received by Alimetrics, microbial groups were measured following the procedure described by Kettunen et al. (2015). Briefly, 2 ml of sample from BioFreeze tubes was transferred to a microfuge tube and centrifuged at 18000 x g for 10 min. The residual pellet was then suspended in 600 μl of a lysis buffer that contained 50 mm EDTA and 100 mm Tris HCl with 20 μl of proteinase K. This suspension was then transferred to tubes that contained 0.4 g of sterile glass beads and the samples were incubated for 1 h at 65°C with 30 s intervals of vortexing at 1400 rpm every 10 min. After incubation, bacterial cells were disrupted using 2 rounds of bead beating for 1 min at 6.5 m/s. Genomic DNA was purified by adding 750 μl of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) followed by 10 min of centrifugation at 10,000 x g. Supernatant (550 μl) was then mixed with 600 μl of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) and centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 10 min. Supernatant (350 μl) was collected and DNA was precipitated by adding 100 % isopropanol and 35 μl of Na-acetate. Samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 18,000 x g and the DNA pellet was washed with 1 ml of 70 % ethanol, dried, and 100 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer was added. Analysis of microbial groups was conducted as described by Kettunen et al. (2015) using quantitative real-time PCR analysis. The target gene for Clostridium perfringens was phospholipase c (plc) gene, whereas 16S rRNA was used for all other genus, family, and species. The information regarding the annealing temperatures and target gene sequences is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primer sequences for real-time PCR analyses.

| Target genus, family, or species |

Annealing temperature (°C) |

Primer sequence (5′−3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 60 | F: TCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT | Nadkarni et al. (2002) |

| R: GGACTACCAGGGTATCTAATCCTGTT | |||

| Bifidobacterium | 65 | F: CGGGTGAGTAATGCGTGACC | Furet et al. (2009) |

| R: TGATAGGACGCGACCCCA | |||

| Ruminococcaceae | 50 | F: GCACAAGCAGTGGAGT | Matsuki et al. (2004) |

| R: CTTCCTCCGTTTTGTCAA | |||

| Lachnospiraceae | 55 | F: CGGTACCTGACTAAGAAGC | Rinttilä et al. (2004) |

| R: AGTTTYATTCTTGCGAACG | |||

| Escherichia coli | 60 | F: GGAGTAAAGTTAATACCTTTGCTC | Davies et al. (2024) |

| R: CCTCTACGAGACTCAAGCTT | |||

| Clostridium perfringens | 62 | F: ATAGATACTCCATATCATCCTGCT | Tansuphasiri (2002) |

| R: TTACCTTTGCTGCATAATCCC |

The VFA in cecal contents were analyzed using gas chromatography as described by Kettunen et al. (2015). Pivalic acid, which was used as an internal standard (2,4 ml; 1.0 mM), was mixed with 400 μl of cecal digesta. After homogenization of samples by shaking, samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 3,000 x g. After centrifugation, 800 μl of supernatant was mixed with 400 μl of an oxalic acid solution, samples were incubated for 60 min at 4°C, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 18,000 x g. Gas chromatography was then conducted to measure FA concentrations in the supernatant using a glass column packed with 80/120 carbopack B-DA/4 % Carbowax stationary phase, helium, and a flame ionization detector. The VFA measured were acetic acid, propanoic acid, butyric acid, lactic acid, and BCFA (iso-butyric acid, 2-methyl-butyric acid, and iso-valeric acid). The total amount of bacterial groups and fatty acids present were calculated as described below.

The concentration of sIgA was determined at the University of Arkansas using ELISA kits developed for chicken IgA (Abnova, Taipei City, Taiwan). Approximately 0.1 g of dried excreta were weighed into 50 ml tubes and 10 ml of saline was added. Samples were then vortexed for 5 s and centrifuged at 1,400 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was then decanted into 15 ml centrifuge tubes, vortexed, and filtered using 1.5 µm nylon syringe filters. Samples were then stored in a −80°C freezer. Prior to analyses, samples were thawed, diluted (1:100), and the ELISA was conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of sIgA in excreta and total sIgA excretion were calculated as described by Parsons et al. (2023). The equation is shown below.

Statistical analysis

Data from all experiments were analyzed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data from Experiment 1 were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA for a completely randomized design. Data from Experiment 2 were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with fasting length as a fixed effect and rooster as a repeated effect. Linear and quadratic effects were also evaluated using Proc GLM. Pairwise treatment comparisons were determined using the least significant difference test (Carmer and Walker, 1985). The significance value for all analyses was P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Experiment 1

There was no difference (P > 0.05) in ad libitum feed intake among fasting groups prior to the initiation of the experimental phase (Table 3). There was approximately 4 g of feed in the crop of roosters (DM basis) at 0 of fasting; no feed was observed in the crop after 3 h of fasting (data not shown). Feed was present in the gizzard of each rooster at each time point. Roosters contained 0.5 to 0.9 g of digesta (DM basis) in the ileum at 3 h of fasting, 1 rooster contained 0.43 and 0.37 g of digesta (DM basis) at h 6 and 9, respectively, and no digesta were present in the ileum after 9 h of fasting. The crop, gizzard, and cecal pH in Experiment 1 are presented in Table 4. There were few differences (P > 0.05) in crop pH among time points from 0 to 12 h of fasting. As fasting length increased, however, there was a linear increase (P < 0.05) in crop pH from 3.69 at 0 h to 5.57 at 24 h. There was a quadratic reduction (P < 0.05) in gizzard pH from 3.94 to 2.85 as fasting length increased, whereas fasting linearly increased (P < 0.05) cecal pH from 5.84 to 6.66. It should be noted that cecal pH increased (P < 0.05) from 0 to 3 h, but no significant differences were observed after 3 h of fasting (P > 0.05). Ford (1974) reported similar trends in chicks, where fasting birds for 18 h increased pH in the crop from 5.0 to 6.7, reduced the pH in the gizzard from 2.5 to 2.2, and increased the cecal pH from 6.2 to 6.8. The cause for the increase in crop and cecal pH could be due to alterations in microbial activity, a total reduction of subtrate available for fermentation, or increased fermentation of protein (exogenous and endogenous) relative to carbohydrate (i.e. fiber) as the residual fiber sources were depleted (Józefiak et al., 2007; Apajalahti and Vienola, 2016). The cause for the reduction in gizzard pH reported in the present study is likely due to increased concentration of HCl as digesta exited with no further inputs rather than alterations in microbial activity since microbial numbers in the gizzard are minute compared with the crop and ceca (Robinson et al., 2022).

Table 3.

Ad libitum feed intake of roosters prior to fasting in Experiment 11.

| Fasting length during experimental phase (h) | Feed intake (g/rooster) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Experiment 12 | Epxeriment 23 | |

| 0 | 39 | - |

| 3 | 41 | - |

| 6 | 39 | - |

| 9 | 34 | - |

| 12 | 39 | - |

| 16 | 42 | - |

| 24 | 39 | 31 |

| SEM | 3.7 | 2.8 |

| P-value | 0.254 | - |

Feed was removed from roosters for 8 h overnight which corresponded with the time that the lights were off. Values in the table are the ad libitum feed consumption of roosters the following morning. Feed was provided to roosters for 8 h.

Values are means of 5 individually caged roosters. Feed intake during the pre-experimental period in Experiment 1 did not differ (P > 0.05) among fasting groups.

Value is a mean of 8 individually caged roosters. All 8 roosters were fasted for 24 h and excreta were collected from each bird at each time point.

Table 4.

Crop, gizzard, and cecal pH in Experiment 1.

| Fasting length (h) | Crop pH | Gizzard pH | Cecal pH |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.69c | 3.94a | 5.84b |

| 3 | 4.19bc | 3.21ab | 6.39a |

| 6 | 4.81ab | 3.22ab | 6.37a |

| 9 | 4.45bc | 2.60b | 6.50a |

| 12 | 4.07bc | 2.56b | 6.31a |

| 16 | 4.62b | 3.09b | 6.33a |

| 24 | 5.57a | 2.85b | 6.66a |

| SEM | 0.286 | 0.285 | 0.131 |

| P-values | |||

| ANOVA | 0.003 | 0.032 | 0.007 |

| Linear | <0.001 | 0.032 | 0.004 |

| Quadratic | 0.475 | 0.021 | 0.381 |

Values within a column with no common superscript differ (P < 0.05). Values are means of 5 individually caged roosters.

Fatty acid concentrations in cecal contents are presented in Fig. 1. Increased fasting length resulted in a reduction (P < 0.05) in the concentration of butyrate from 15.0 to 12.5 and further to 5.0 mmol/kg as fasting length increased from 3 h to 6 and 9 h, respectively. Few differences (P > 0.05) were observed for other fatty acids; however, similar numeric trends were observed for acetic acid, propionic acid, and total VFA concentration compared with butyric acid. After determination of fatty acid concentration, the total amount of fatty acids present were then calculated by multiplying the fatty acid concentration by the total weight of cecal contents (Fig. 2). Similar trends were observed for acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, BCFA, and total VFA, where the total amount of these molecules in the ceca were reduced (P < 0.05) by fasting lengths of 6 to 9 h. Interestingly, however, despite the reduction in both the total amount of BCFA and total VFA content in the ceca, the ratio of BCFA to total VFA increased (P < 0.05) with as little as 6 h of fasting. This is an interesting observation, as acetic, propionic, and butyric acid are produced primarily as end products from fermentation of carbohydrates by microbial species in the gastrointestinal tract, whereas BCFA are end products from amino acid metabolism (Rios-Covian et al., 2020). The increase in the BCFA to VFA ratio as fasting length increased (Fig. 2) combined with the observation that the amount of cecal contents was linearly reduced as fasting length increased (P < 0.05; Table 5) suggests that as the ceca were emptied, there likely was a proportional increase in amino acids of endogenous origin entering the ceca.

Fig. 1.

Concentrations of (a) acetic acid, (b) propionic acid, (c) butyric acid, (d) lactic acid, (e) branched chain fatty acids, and (f) total volatile fatty acids in cecal contents vs. fasting length in Experiment 1. Values are means ± SE of 5 individually caged roosters. Values with no common superscript differ (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Total amount of (a) acetic acid, (b) propionic acid, (c) butyric acid, (d) branched chain fatty acids, (e) total volatile fatty acids, and (f) branched chain fatty acid to volatile fatty acid ratio in cecal contents vs. fasting length in Experiment 1. Values are means ± SE of 5 individually caged roosters. Values with no common superscript differ (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

| Fasting length (h) | Cl. Perfringens | Ruminoc. | Bifidob. | Lachno. | E. coli | Total bacteria3 | Total cecal contents (g; wet basis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.1E+05b | 3.9E+11 | 9.3E+09 | 3.5E+11 | 1.3E+08b | 3.2E+12 | 2.49 |

| 3 | 5.6E+04b | 4.5E+11 | 7.5E+09 | 4.9E+11 | 3.4E+08b | 4.5E+12 | 2.26 |

| 6 | 1.4E+05b | 6.6E+11 | 4.7E+10 | 5.5E+11 | 3.1E+07b | 4.9E+12 | 2.31 |

| 9 | 9.1E+05a | 6.7E+11 | 3.3E+10 | 3.6E+11 | 8.0E+07b | 4.8E+12 | 2.27 |

| 12 | 1.3E+05b | 3.4E+11 | 9.6E+09 | 3.4E+11 | 2.1E+09b | 3.4E+12 | 1.97 |

| 16 | 7.6E+04b | 3.9E+11 | 1.1E+10 | 3.6E+11 | 3.1E+09ab | 3.3E+12 | 1.66 |

| 24 | 1.1E+05b | 5.1E+11 | 4.8E+09 | 3.8E+11 | 9.2E+09a | 5.1E+12 | 1.36 |

| SEM | 8.33E+04 | 1.57E+11 | 1.33E+10 | 7.83E+10 | 1.72E+09 | 1.03E+12 | 0.301 |

| P-values | |||||||

| ANOVA | 0.003 | 0.692 | 0.315 | 0.486 | 0.010 | 0.747 | 0.068 |

| Linear | 0.952 | 0.940 | 0.537 | 0.490 | <0.001 | 0.501 | <0.001 |

| Quadratic | 0.356 | 0.678 | 0.194 | 0.982 | 0.056 | 0.930 | 0.855 |

Values within a column with no common superscript differ (P < 0.05). Values are means of 5 individually caged roosters.

Values are expressed as rRNA gene copies per gram of cecal contents.

Cl. Perfringens = Clostridium perfringens; Ruminoc. = Ruminococcaceae; Bifidob. = Bifidobacterium; Lachno. = Lachnospiraceae; E. coli = Escherichia coli.

Total bacteria = total 16S rRNA gene copies measured per gram of cecal contents.

The reduction in VFA concentrations in the ceca due to fasting in the present study is in good agreement with Anderson et al. (2023) who reported that adult roosters subjected to the 48 h fasting period used in the precision-fed rooster assay exhibited reductions in acetic, propionic, and butyric acid concentrations in the ceca from 69 to 25, 25 to 8, and 7 to 1 mmol/kg, respectively, compared with ad libitum fed birds. Although samples were only collected at the end of a 48 h fasting period in the study by Anderson et al. (2023), data herein provides information on the effect of incremental fasting length on cecal VFA concentrations. The amount of acetic, propionic, and butyric acid in the ceca had been reduced after 6 to 9 h of fasting in the present study, which occurred well before the initial observations after 48 h of fasting made previously by Anderson et al. (2023). The reduction in butyric acid in particular could have important implications on intestinal barrier integrity, as this fatty acid is an essential energy substrate for epithelial cells (Roediger, 1982). Therefore, the reduction in butyrate caused by fasting may deprive epithelial cells in the ceca of energy, thereby increasing the susceptibility of the birds to infection and inflammation.

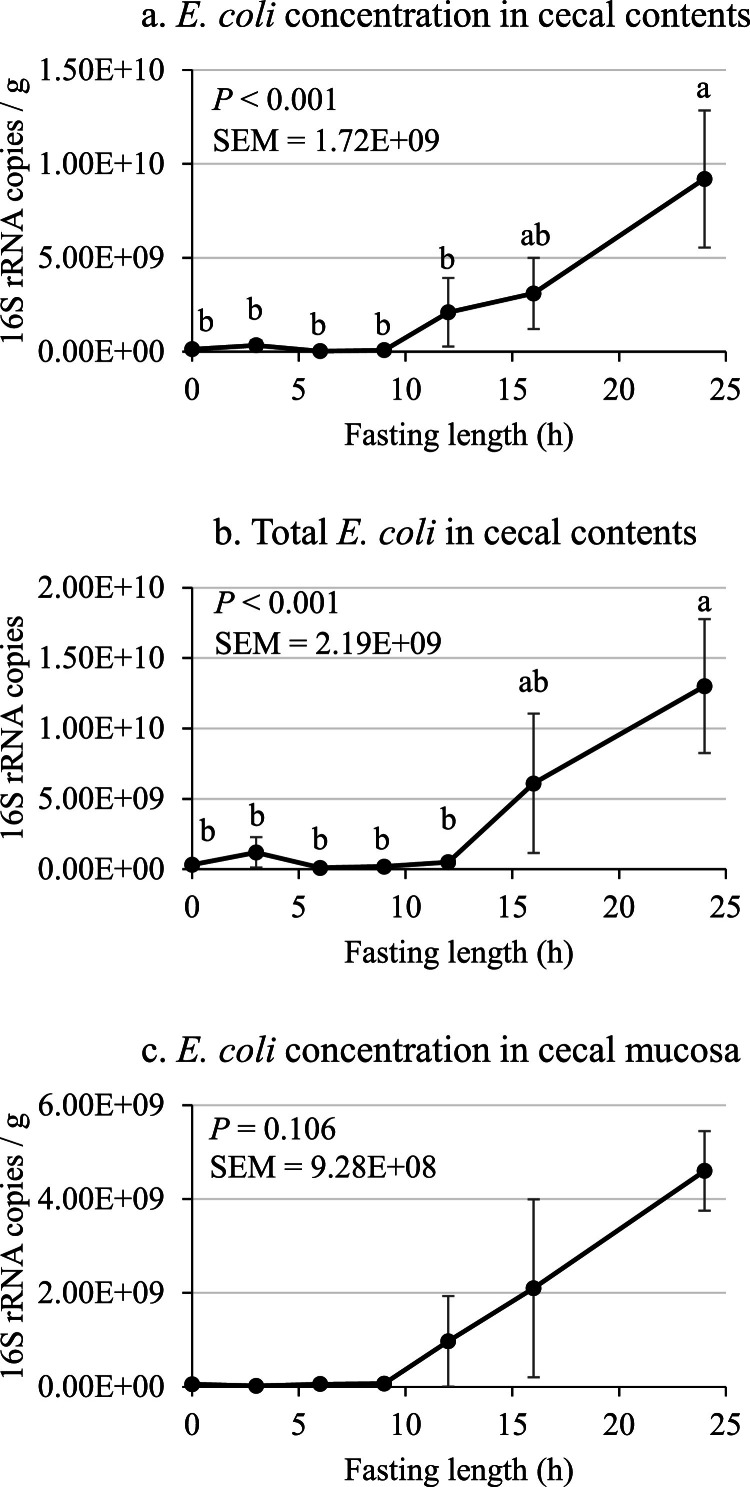

The concentration and total amount of bacteria in cecal contents are presented in Table 5, Table 6. There was no effect of fasting (P > 0.05) on the concentration and total amount of Ruminococcaceae, Bifidobacterium, and total 16S rRNA gene copies in the cecal contents. The concentration and total amount of Clostridium perfringens in cecal contents, however, was found to be greater (P < 0.05) in roosters fasted for 9 h compared with other time points, while the total amount of Lachnospiraceae in cecal contents was found to be linearly reduced (P < 0.05) as fasting length increased. The most substantial change to cecal microbial groups caused by fasting occurred for E. coli. There was a linear effect of fasting length (P < 0.05) on the concentration of E. coli and a quadratic effect (P < 0.05) on total E. coli in the cecal contents. As shown in Fig. 3, the concentration of E. coli began to numerically increase by 12 h of fasting and significantly increased (P < 0.05) by 24 h of fasting. A similar trend was observed for total E. coli in the cecal contents, where there was a numeric increase at 16 h and a significant increase (P < 0.05) at 24 h of fasting.

Table 6.

| Fasting length (h) | Cl. Perfringens | Ruminoc. | Bifidob. | Lachno. | E. coli | Total bacteria3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.7E+05b | 9.6E+11 | 2.3E+10 | 9.2E+11ab | 3.2E+08b | 8.0E+12 |

| 3 | 1.7E+05b | 1.3E+12 | 1.7E+10 | 1.2E+12a | 1.2E+09b | 1.2E+13 |

| 6 | 4.1E+05b | 1.9E+12 | 9.5E+10 | 1.4E+12a | 1.0E+08b | 1.4E+13 |

| 9 | 1.9E+06a | 1.5E+12 | 7.5E+10 | 8.2E+11ab | 1.9E+08b | 1.1E+13 |

| 12 | 2.3E+05b | 6.5E+11 | 1.3E+10 | 6.0E+11b | 5.1E+08b | 6.8E+12 |

| 16 | 1.3E+05b | 6.7E+11 | 1.9E+10 | 6.3E+11ab | 6.1E+09ab | 5.8E+12 |

| 24 | 1.6E+05b | 6.7E+11 | 6.0E+09 | 5.1E+11b | 1.3E+10a | 6.8E+12 |

| SEM | 1.59E+05 | 4.01E+11 | 2.54E+10 | 1.85E+11 | 2.19E+09 | 2.88E+12 |

| P-values | ||||||

| ANOVA | 0.001 | 0.346 | 0.184 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.486 |

| Linear | 0.695 | 0.191 | 0.372 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.220 |

| Quadratic | 0.302 | 0.478 | 0.194 | 0.926 | 0.013 | 0.603 |

Values within a column with no common superscript differ (P < 0.05). Values are means of 5 individually caged roosters.

Values are expressed as total rRNA gene copies in cecal contents.

Cl. Perfringens = Clostridium perfringens; Ruminoc. = Ruminococcaceae; Bifidob. = Bifidobacterium; Lachno. = Lachnospiraceae; E. coli = Escherichia coli.

Total bacteria = total 16S rRNA gene copies measured per gram of cecal contents.

Fig. 3.

(a) E. coli concentration in cecal contents, (b) total E. coli in cecal contents, and (c) E. coli concentration in cecal mucosa vs. fasting length in Experiment 1. Values are means ± SE of 5 individually caged roosters for (a) and (b) and 2 pooled samples from 2 roosters for (c). Values with no common superscript differ (P < 0.05).

The microbial groups in the cecal mucosa exhibited similar trends to cecal contents, where there was no effect of fasting on the concentrations of Clostridium perfringens, Ruminococcaceae, Bifidobacterium, Lachnospiraceae, and total 16S rRNA copies (Table 7). There was a quadratic increase (P < 0.05), however, for E. coli in the cecal mucosa as fasting length increased. This effect is explained by the numeric increase in E. coli after 9 h of fasting (Fig. 3). These results are in good agreement with Anderson et al. (2023) who reported increased E. coli in the cecal contents of roosters that were fasted for 48 h compared with ad libitum-fed birds.

Table 7.

| Fasting length (h) | Cl. Perfringens | Ruminoc. | Bifidob. | Lachno. | E. coli | Total bacteria4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 9.3E+05 | 1.2E+11 | 1.8E+09 | 2.2E+11 | 5.4E+07 | 5.9E+11 |

| 3 | 0.0E+00 | 8.9E+10 | 7.4E+08 | 1.7E+11 | 2.0E+07 | 4.4E+11 |

| 6 | 2.1E+05 | 1.2E+11 | 4.3E+09 | 2.5E+11 | 5.8E+07 | 8.6E+11 |

| 9 | 1.1E+05 | 1.6E+11 | 1.9E+09 | 2.6E+11 | 6.9E+07 | 8.7E+11 |

| 12 | 6.4E+04 | 7.3E+10 | 1.7E+09 | 6.0E+10 | 9.7E+08 | 5.0E+11 |

| 16 | 0.0E+00 | 1.4E+11 | 1.3E+09 | 2.4E+11 | 2.1E+09 | 6.9E+11 |

| 24 | 2.9E+04 | 1.4E+11 | 1.3E+09 | 3.1E+11 | 4.6E+09 | 7.0E+11 |

| SEM | 2.07E+05 | 5.98E+10 | 1.05E+09 | 1.25E+11 | 9.28E+08 | 3.54E+11 |

| P-values | ||||||

| ANOVA | 0.168 | 0.970 | 0.488 | 0.933 | 0.106 | 0.977 |

| Linear | 0.049 | 0.652 | 0.435 | 0.536 | <0.001 | 0.864 |

| Quadratic | 0.060 | 0.898 | 0.574 | 0.602 | 0.065 | 0.670 |

There were no differences (P > 0.05) among treatment means. Values are means of 2 pooled samples from 2 individually caged roosters.

Values are expressed as rRNA gene copies per gram of cecal mucosa.

Cl. Perfringens = Clostridium perfringens; Ruminoc. = Ruminococcaceae; Bifidob. = Bifidobacterium; Lachno. = Lachnospiraceae; E. coli = Escherichia coli.

Total bacteria = total 16S rRNA gene copies measured per gram of cecal contents.

The lack of effect (P > 0.05) of fasting on Ruminococcaceae and Bifidobacterium in both the cecal contents and cecal mucosa could have important implications for fermentation. The Ruminococcaceae family contains organisms that ferment fiber and produce butyrate (Rychlik, 2021). Microbes in the Bifidobacterium family can also ferment fiber to produce fatty acids, such as lactate and acetate, which can be absorbed by the host or partake in cross-feeding interactions in which they provide substrates for butyrate-producing microorganisms (De Vuyst and Leroy, 2011; Rivière et al., 2015). The constant levels of these groups in the cecal mucosa suggest that these microbes may adhere to the mucus layer as a means by which to remain in the ceca and prevent being expelled with cecal contents. This would provide a mechanism by which to re-establish the microbial populations as new digesta enters the ceca in order to maintain stable microbial populations and prevent dysbiosis. It should be noted, however, that the digesta derived substrate available to these adherent microbes probably became depeleted over time and was replaced by mucosal substrates which likely altered their metabolism, which is reflected in altered VFA and BCFA profiles.

As mentioned previously, fasting resulted in increased E. coli populations in both the cecal contents and cecal mucosa (Fig. 3) which is likely indicative of a negative effect of fasting. Elevated levels of E. coli in the large intestine have been found to be associated with colitis in mice, inflammatory bowel disease in humans, and impairments in gastrointestinal function in children with cystic fibrosis (Carvalho et al., 2012; Mukhopadhya et al., 2012; Hoffman et al., 2014; Yang and Jobin, 2014). It is also well known that specific strains of E. coli are pathogenic and cause food-borne illness in humans (Chapman et al., 1997). Furthermore, E. coli has been found to support the growth of pathogenic organisms in chickens and turkeys, such as Histomonas meleagridis (Bradley and Reid, 1966; Ganas et al., 2012; Bilic and Hess, 2020). Due to the potential role of E. coli in causing dysbiosis and increasing risk of infection and disease, the effect of fasting reported herein on E. coli prevalence in the ceca could have important implications for how fasting is used in poultry production. Although more research is needed to evaluate the incremental effect of fasting in more practical poultry production settings, data from the present study suggests that fasting length should be minimized to what is necessary to achieve the desired outcome, as the risk of dysbiosis in the ceca may increase as fasting times increase.

Overall, when evaluating the effects of fasting and timing at which the effects occurred in Experiment 1, there are a number of interesting observations. The increase in cecal pH as fasting length increased (Table 4) coincided with a reduction in total VFA concentraiton in the ceca (Fig. 2). This suggests that the pH in the ceca is at least partially dependent on microbial activity, specifically acetic, propionic, and butyric acid production. Similar results were reported by Ford (1974) in which axenic chicks were reported to have a higher cecal pH compared with conventional birds, being 7.4 and 6.8, respectively. Further, Ford (1974) found that fasting conventional birds for 18 h increased the cecal pH from 6.2 to 6.8. The decrease in cecal VFA and increase in cecal pH in the present study are important observations as both pH and VFA concentration have been shown to exhibit regulatory effects on the microbiota. Wolin (1969) reported that increasing the concentration of acetic, propionic, and butyric acid in bovine rumen fluid reduced the growth of E. coli in vitro. Further, the inhibition of E. coli by VFA was found to be pH dependent, as addition of VFA resulted in 96 % inhibition of E. coli when the pH was 6.0, but this effect was reduced to 2 % inhibition at a pH of 7.0. The increase in E. coli in the present study (Fig. 3) observed at 24 h of fasting may, therefore, be a result of the reduction in VFA and subsequent increase in cecal pH.

The BCFA to VFA ratio increased at similar time points to the increase in cecal pH and reduction in cecal VFA concentraitons. This ratio may, therefore, serve as an indicator of intestinal homeostasis. Branched-chain fatty acids and their deratives are associated with increase risk of disease (Rios-Covian et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Salazar et al., 2022). As discussed previously, an increase in the BCFA to VFA ratio is indicative of a shift from carbohydrate to protein fermentation in the ceca (Smith and Macfarlane, 1998). In humans, many organism in the Clostridum genus have been found to produce BCFA (Smith and Macfarlane, 1998). In poultry, some members of the Clostridium genus are known to cause disease, i.e. Clostridium perfringens is known to be a causative agent of necrotic enteritis (Parish, 1961; Emami and Dalloul, 2021). It is also important to note that E. coli belong to the proteobacteria phylum, obtain nutrients from mucus, and some strains can be pathogenic (Conway et al., 2004; Rizzatti et al., 2017; Doranga et al., 2024). The increase in the BCFA to VFA ratio reported herein that preceded the increase in E. coli at 24 h of fasting suggests that the BCFA to VFA ratio may have potential as a marker of intestinal status or health in chickens which warrants further research.

Experiment 2

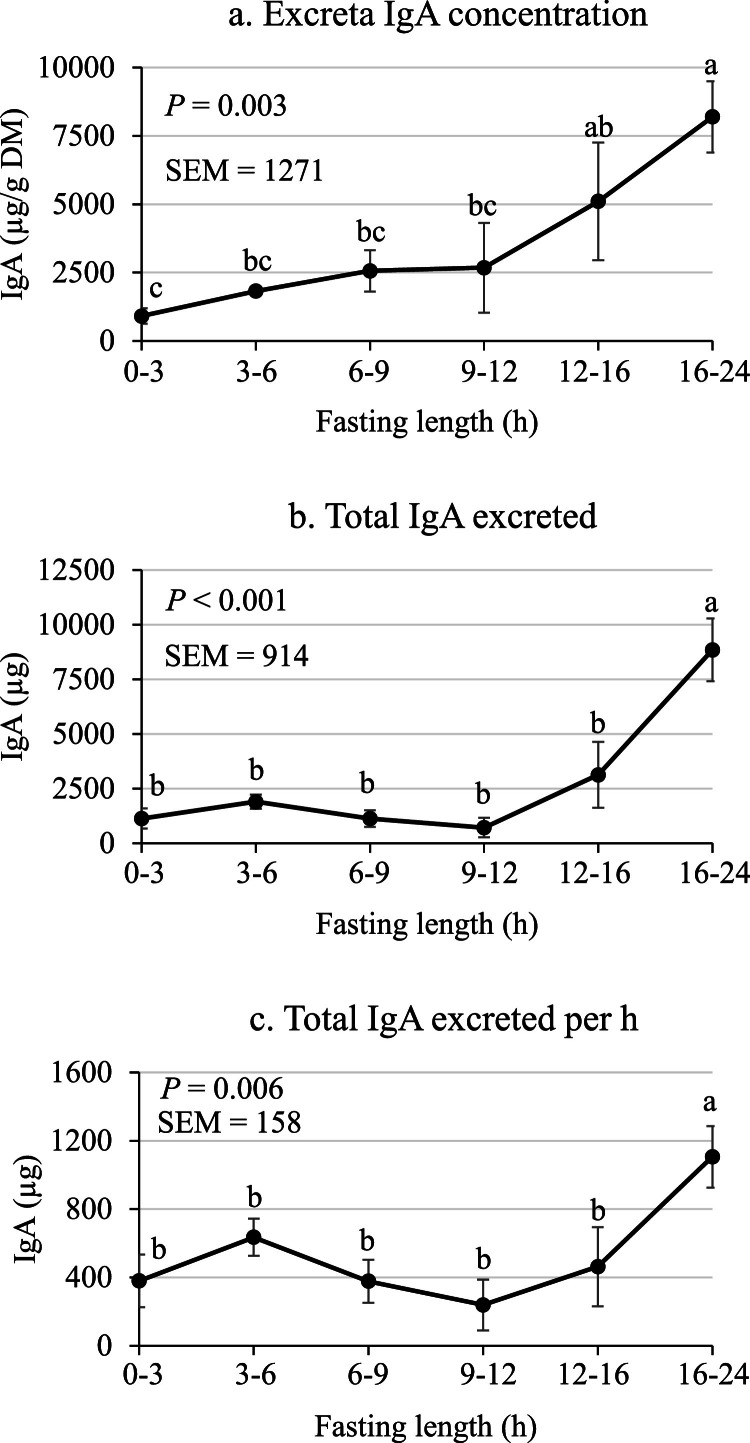

The effect of fasting length on sIgA excretion in Experiment 2 was determined using a separate set of 8 roosters (Fig. 4). In this experiment, sIgA excretion was evaluated in each individual rooster at every time point to control for the effect of the individual bird. Parsons et al. (2023) previously evaluated sIgA excretion in adult Leghorn roosters and found that roosters that were fasted for 48 h excreted less sIgA (2.7 mg / 24 h) compared with roosters precision-fed a nitrogen-free diet (6.7 mg / 24 h). Further, Parsons et al. (2023) found that sIgA excretion differed among individual roosters, thus highlighting the importance of controling for the effect of the invidual bird when measuring sIgA excretion in this bioassay. In the present study, the concentration of sIgA and total sIgA excreted were greater (P < 0.05) from 16 to 24 h of fasting compared with shorter fasting lengths (Fig. 4). Further, sIgA excretion per h was greater (P < 0.05) from 16 to 24 h of fasting (1106 µg/h) compared with earlier time points (mean of 419 µg/h). The increased sIgA excretion in roosters from 16 to 24 h of fasting herein compared with the previous observation that fasting reduced sIgA exretion (Parsons et al., 2023) may be due to the longer fasting period used in the previous study, where excreta were collected from 24 to 48 h of fasting. The cause for the discrepancy between studies, however, remains to be elucidated.

Fig. 4.

(a) Excreta IgA concentration, (b) total IgA excreted, and (c) total IgA excreted per h in Experiment 2. Values are means ± SE of 8 individually caged roosters. Values with no common superscript differ (P < 0.05).

The increase in sIgA excretion from 16 to 24 h of fasting (Fig. 4) is an interesting observation when compared with Experiment 1. In the first experiment, E. coli concentrations and total E. coli present in cecal contents were greater at 24 h of fasting compared with 0 to 12 h of fasting (Fig. 3). Secretion of sIgA is an important mechanism by which animals can regulate the microbiota in the intestine and prevent damage to the intestinal epithelium (Perrier et al., 2006; Mantis et al., 2011; Bunker et al., 2017). Further, Parsons et al. (2023) found that adult roosters excrete a substantial amount of sIgA equating to approximately 12 to 15 mg / 24 h. Although the increase in E. coli in the ceca and increased sIgA excretion were measured in 2 separate sets of roosters, these experiments were run simultaneously in the same room and thus it is possible that the roosters increased antibody secretion into the intestine as a response to the increase in E. coli in an attempt to prevent damage to the epithelium and ameliorate dysbiosis.

Results from the present study suggest that fasting lengths up to 24 h can elicit negative effects on the gastrointestinal tract of chickens as shown by the reduction in cecal VFA concentrations and increase in cecal pH, E. coli, and sIgA excretion. The practice of fasting birds has been used in the poultry industry for a variety of reasons. Laying hens have historically been fasted for approximately 14 days to induce molting and extend the laying cycle (Hurwitz et al., 1995). Although this is an effective means by which to extend the lay cycle, it has been reported that feed-withdrawal molt programs may increase the susceptibility of hens to infections, such as Salmonella enteritidis and E. Sigella (Holt, 1995; Zhang et al., 2024). Further, Corrier et al. (1997) reported that laying hens subjected to a 14 d feed withdrawal molt program had lower concentrations of acetate and propionate in the ceca at the end of the fasting period compared with unfasted hens.

In addition to feed withdrawal molt programs, fasting is also routinely used when raising broiler chickens and broiler breeders. When raising broiler breeder pullets, fasting is used as a means by which to prevent excessive weight gain. For instance, skip-a-day feeding programs may be used in which the birds will be without feed for 24 h or more (Bartov et al., 1988). In contrast, broiler chickens are generally provided ad libitum access to feed until they reach market age, after which they will be fasted overnight for a minimum of 6 to 8 h prior to processing to reduce fecal excretion and risk of microbial contamination during meat processing (Northcutt et al., 1997). Utilization of fasting in these programs may increase the susceptibility of chickens to dysbiosis. Wilson et al. (2018) reported that skip-a-day feeding for broiler breeder pullets was found to increase Salmonella and Campylobacter colonization in the ceca compared with every-day feeding. Further, pre-harvest fasting of broiler chickens has been shown to result in reductions in mucus production, alternations in intestinal morphology, and increased adhesion of Salmonella enteritidis (Northcutt et al., 1997; Thompson and Applegate, 2006; Burkholder et al., 2008).

The negative effects of fasting on the gastrointestinal tract of broiler breeder pullets and growing broiler chickens reported previously are in good agreement with the present study, in which reductions in cecal pH and VFA concentrations occured within 3 and 9 h of fasting, respectively. This suggests that prolonged fasting in chickens may negatively affect intestinal homeostasis which could lead to dysbiosis, infection, and inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. It is important to note, however, that the data obtained from the present study are not directly applicable to the fasting scenarios discussed above. This is due to the fact that adult Leghorn roosters were used and the birds were subjected to up to 24 h of fasting once. Growing broiler chickens may respond differently to fasting as they likely have a less well-developed and stable microbiota compared with adult roosters. In contrast, broiler breeders pullets that are repeatedly subjected to fasting periods over the course of their production cycle may develop adaptations to maintain a stable microbiota, such as reducing the frequency in which cecal contents are voided.

Another important consideration when evaluating the effect of fasting on the gastrointestional tract is the diet the birds received. Roosters in the present study were provided with a corn-soybean meal-based diet. Utilization of alternative feedstuffs, such as canola meal, distillers dried grains with solubles, wheat middlings, and barley would alter both the type and total amount of fiber present and potentially alter the amount of protein entering the ceca as well. McCafferty et al. (2019) reported that utilization of a wheat-based diet increased cecal butyric acid but reduced propionic acid compared with broiler chickens fed a corn-based diet. Anderson et al. (2023) reported that cecal short-chain fatty acids were numerically increased by 48 and 62 millimoles per kg when rye and barley were added to a control corn-soybean meal diet, respectively. Furthermore, size of fiber particles must also be considered as Vanderghinste et al. (2023) reported that the mean size of particles in the cecal digesta in broiler chickens from 8 to 36 d-of-age ranged from 5 to 19 µm, indicating that only extremely small fiber particles from the diet can enter the ceca of chickens. Utilization of feedstuffs that vary in oligosaccharides, non-starch polysaccharides, and particle size may, therefore, alter the response of birds to fasting by altering VFA production and the rate at which cecal contents are voided.

In summary, fasting adult Leghorn roosters for up to 24 h resulted in negative effects on the gastrointestinal tract. The pH in the ceca and cecal BCFA to VFA ratio increased after 6 h of fasting, cecal VFA concentrations were reduced after 6 to 9 h of fasting, E. coli in the cecal contents began to increase after 9 to 12 h of fasting, and sIgA excretion was increased by 24 h of fasting. These results demonstraste that fasting can alter microbial activity in the ceca and lead to a reduction in VFA which may predispose the birds to dysbiosis. Further research is warranted to better characterize the incremental effects of fasting in various production settings for poultry and to identify dietary interventions to ameliorate these effects.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Scientific Section: Metabolism and Nutrition

References

- Anderson A.G., Bedford M..R., Parsons C.M. Effects of adaptation diet and exogenous enzymes on true metabolizable energy and cecal microbial ecology, short-chain fatty acid profile, and enzyme activity in roosters fed barley and rye diets. Poult. Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. 2007. Official methods of analysis. 18th ed. Rev. 2. AOAC int., Gaithersburg, MD.

- Apajalahti J., Vienola K. Interaction between chicken intestinal microbiota and protein digestion. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2016;221:323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Bartov I., Bornstein S., Lev Y., Pines M., Rosenberg J. Feed restriction in broiler breeder pullets: skip-a-day versus skip-two-days. Poult. Sci. 1988;67:809–813. doi: 10.3382/ps.0670809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D.D., Kuney D.R. Farm evaluation of alternative molting procedures. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2004;13:673–679. [Google Scholar]

- Berry W.D. The physiology of induced molting. Poult. Sci. 2003;82:971–980. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgili S.F. Slaughter quality as influenced by feed withdrawal. World's. Poult. Sci. J. 2002;58:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bilic I., Hess M. Interplay between Histomonas meleagridis and bacteria: mutualistic or predator-prey. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:232–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R.E., Reid M.W. Histomonas meleagridis and several bacteria as agents of infectious enterohepatitis in gnotobiotic turkeys. Exp. Parasitol. 1966;19:91–101. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(66)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunker J.J., Erickson S..A., Flynn T.M., Henry C., Koval J.C., Meisel M., Jabri B., Antonopoulos D.A., Wilson P.C., Bendelac A. Natural polyreactive IgA antibodies coat the intestinal microbiota. Science. 2017;358:eaan6619. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder K.M., Thompson K..L., Einstein M.E., Applegate T.J., Patterson J.A. Influence of stressors on normal intestinal microbiota, intestinal morphology, and susceptibility to Salmonella enteritidis colonization in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2008;87:1734–1741. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmer S.G., Walker W.M. Pairwise multiple comparisons of treatment means in agronomic research. J. Agron. Educ. 1985;14:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro P.R.O., Lunedo R., Fernandez-Alarcon M.F., Baldissera G., Freitas G.G., Macari M. Effect of different feed restriction programs on the performance and reproductive traits of broiler breeders. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:4705–4715. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho F.A., Koren O.., Goodrich J.K., Johansson M.E.V., Nalbantoglu I., Aitken J.D., Su Y., Chassaing B., Walters W.A., González A., Clemente J.C., Cullender T.C., Barnich N., Darfeuille-Michaud A., Vijay-Kumar M., Knight R., Ley R.E., Gewirtz A.T. Transient inability to manage proteobacteria promotes chronic gut inflammation in TLR5-deficient mice. Cell. Host. Microbe. 2012;12:139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman P.A., Siddons C.A., Cerdan Malo A.T., Harkin M.A. A 1-year study of Escherichia coli O157 in cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry. Epidemiol. Infect. 1997;119:245–250. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikina A., Vignjevic D.M. At the right time in the right place: how do luminal gradients position the microbiota along the gut? Cells & Develop. 2021;168 doi: 10.1016/j.cdev.2021.203712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway T., Krogfelt K.A., Cohen P.S. The life of commensal Escherichia coli in the mammalian intestine. Eco. Sal. Plus. 2004;1:1–15. doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.8.3.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrier D.E., Nisbet D..J., Hargis B.M., Holt P.S., DeLoach J.R. Provision of lactose to molting hens enhances resistance to Salmonella enteritidis colonization. J. Food Prot. 1997;60:10–15. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-60.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C., Gonzáles-Ortiz G., Rinttilä T., Apajalahti J., Alyassin M., Bedford M.R. Stimbiotic supplementation and xylose-rich carbohydrates modulate broiler's capacity to ferment fibre. Front. Microbiol. 2024;14:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1301727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vuyst L., Leroy F. Cross-feeding between bifidobacteria and butyrate-producing colon bacteria explains bifidobacterial competitiveness, butyrate production, and gas production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011;149:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doranga S., Krogfelt K.A., Cohen P.S., Conway T. Nutrition of Escherichia coli within the intestinal microbiome. EcoSal. Plus. 2024;12:1–24. doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0006-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami N.K., Dalloul R.A. Centennial Review: recent developments in host-pathogen interactions during nectrotic enteritis in poultry. Poult. Sci. 2021;100 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford D.J. The effect of the microflora on gastrointestinal pH in the chick. Brit. Poult. Sci. 1974;15:131–140. doi: 10.1080/00071667408416086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furet J.P., Firmesse O.., Gourmelon M., Bridonneau C., Tap J., Mondot S., Doré J., Corthier G. Comparative assessment of human and farm animal faecal microbiota using real-time quantitative PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009;68:351–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganas P., Liebhart D., Glösmann M., Hess C., Hess M. Escherichia coli strongly supports the growth of Histomnas meleagridis, in a monoxenic culture, without influence on its pathogenicity. Int. J. Parastiol. 2012;42:893–901. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz S., Wax E., Nisenbaum Y., Plavnik I. Responses of laying hens to forced molt procedures of variable length with or without light restriction. Poult. Sci. 1995;74:1745–1753. doi: 10.3382/ps.0741745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L.R., Pope C..E., Hayden H.S., Heltshe S., Levy R., McNamara S., Jacobs M.A., Rohmer L., Radey M., Ramsey B.W., Brittnacher M.J., Borenstein E., Miller S.I. Escherichia coli dysbiosis correlates with gastrointestinal dysfunction in children with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:396–399. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt P.S. Horizontal transmission of Salmonella enteritidis in molted and unmolted laying chickens. Avian Dis. 1995;39:239–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itani K., Ahmed M., Ghimire S., Schüller R.B., Apajalahti J., Smith A., Svihus B. Interaction between feeding regimen, NSPase enzyme and extent of grinding of barley-based pelleted diets on the performance, nutrient digestibility and ileal microbiota of broiler chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2025:1–12. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2025.2451245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Józefiak D., Rutkowski A., Jensen B.B., Engberg R.M. The effect of β-glucanase supplementation of barley- and oat-based diets on growth performance and fermentation in broiler chicken gastrointestinal tract. Brit. Poult. Sci. 2007;47:57–64. doi: 10.1080/00071660500475145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen H., van Eerden E., Lipiński K., Rinttilä T., Valkonen E., Vuorenmaa J. Dietary resin acid composition as a performance enhancer for broiler chickens. J. Appl. Anim. Nutr. 2017;5:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen H., Vuorenmaa J., Rinttilä T., Grönberg H., Valkonen E., Apajalahti J. Natural resin acid -enriched composition as a modulator of intestinal microbiota and performance enhancer in broiler chicken. J. Appl. Anim. Nutr. 2015;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Koelkebeck K.W., Parsons C..M., Biggs P., Utterback P. Nonwithdrawal molting programs. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2006;15:483–491. [Google Scholar]

- Mantis N.J., Rol N.., Corthésy B. Secretory IgA's complex roles in immunity and mucosal homeostasis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:603–611. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki T., Watanabe K., Fujimoto J., Takada T., Tanka R. Use of 455 16S rRNA gene-targeted group-specific primers for real-time PCR analysis of 456 predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:7220–7228. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7220-7228.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty K.W., Bedford M..R., Kerr B.J., Dozier W.A. Effects of age and supplemental xylanase in corn- and wheat-based diets on cecal volatile fatty acid concentrations of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:4787–4800. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhya I., Hansen R., El-Omar E.M., Hold G.L. IBD-what role do proteobacteria play? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9:219–230. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni M.A., Martin F..E., Jacques N.A., Hunter N. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiol. 2002;148:257–266. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcutt J.K., Savage S..I., Vest L.R. Relationship between feed withdrawal and viscera condition of broilers. Poult. Sci. 1997;76:410–414. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish W.E. Necrotic enteritis in the fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus). I. Histopathology of the disease and isolation of a strain of Clostridium welchii. J. Comp. Pathol. 1961;71:377–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons B.W., Drysdale R..L., Cvengros J.E., Utterback P.L., Rochell S.J., Parsons C.M., Emmert J.L. Quantification of secretory IgA and mucin excretion and their contributions to total endogenous amino acid losses in roosters that were fasted or precision-fed a nitrogen-free diet or various highly digestible protein sources. Poult. Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier C., Sprenger N., Corthésy B. Glycans on secretory component participate in innate protection against mucosal pathogens. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:14280–14287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinttilä T., Kassinen A., Malinen E., Krogius L., Palva A. Development of an extensive set of 16S rDNA-targeted primers for quantification of pathogenic and indigenous bacteria in fecal samples by real-time PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004;97:1166–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios-Covian D., González S., Nogacka A.M., Arboleya S., Salazar N., Gueimonde M., de los Reyes-Gavilán C.G. An overview of fecal branched short-chain fatty acids along human life and as related with body mass index: associated dietary and anthropometric factors. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:973–981. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivière A., Gagnon M., Weckx S., Roy D., De Vuyst L. Mutual cross-feeding interactions between bifidobacterium longum subsp. Longum NCC2705 and eubacterium rectale ATCC33656 explain the bifidogenic and butrogenic effects of arabinoxylan oligosaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:7767–7781. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02089-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzatti G., Lopetuso L.R., Gibiino G., Binda C., Gasbarrini A. Proteobacteria: a common fator in human diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/9351507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K., Yang Q., Stewart S., Whitmore M.A., Zhang G. Biogeography, succession, and origin of the chicken intestinal mycobiome. Microbiome. 2022;11:55. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger W.E. Utilization of nutrients by isolated epithelial cells of the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:424–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik I. In: Advancements and Technologies in Pig and Poultry Bacterial Disease Control. Foster N., Kyriaakis I., Barrow P., editors. Acad. Press; Cambridge, MA: 2021. 10 – Monitoring microbiota in chickens and pigs; pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar N., González S., Gonzalez de los Reyes Gavilan C., Rios-Covian D. In: Biomarkers in Nutrition. Patel V.B., Preedy V.R., editors. Springer; Cham: 2022. Branched short-chain faty acids as biological indactors of microbiota health and links with anthropometry; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E.A., Macfarlane G.T. Enumeration of amino acid fermenting bacteria in the human large intestine: effects of pH and starch on peptide metabolism and dissimilation of amino acids. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 1998;25:355–368. [Google Scholar]

- Tansuphasiri U. Development of duplex PCR assay for rapid detection of enterotoxigenic isolates of Clostridium perfringens. Southeast Asian J. of Trop. Med. and Public Health. 2002;32:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K.L., Applegate T.J. Feed withdrawal alters small-intestinal morphology and mucus of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2006;85:1535–1540. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.9.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacca M., Celano G., Calabrese F.M., Portincasa P., Gobbetti M., De Angelis M. The controversial role of human gut lachnospiraceae. Microorganisms. 2020;8:573–597. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8040573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderghinste P., Bautil A., Bedford M., Gonzalez-Ortiz G. Revealing the phytical restrictions of caecal influx to improve caecal fibre fermentation in broilers: effect of insoluble fibre particle size and age. 23rd Europ. Symp. Poult. Nutr. 2023 (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, R. A., .K.. Doranalli, T. Rinttilä, K. Vienola, G. Jurgens, and J. Apajalahti. 2019. The impact of Bacillus subtilis DSM 32315 on the pathology, performance, and intestinal microbiome of broiler chickens in a necrotic enteritis challenge. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wilson K.M., Bourassa D..V., McLendon B.L., Wilson J.L., Buhr R.J. Impact of skip-a-day and every-day feeding programs for broiler breeder pullets on the recovery of Salmonella and Campylobacter following challenge. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:2775–2784. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin M.J. Volatile fatty acids and the inhibition of Escherichia coli growth by rumen fluid. Appl. Microbiol. 1969;17:83–87. doi: 10.1128/am.17.1.83-87.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Jobin C. Microbial imbalance and intestinal pathologies: connections and contributions. Dis. Model Mech. 2014;7:1131–1142. doi: 10.1242/dmm.016428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., van der Wielen N., van der Hee B., Wang J., Hendriks W., Gilbert M. Impact of fermentable protein, by feeding high protein diets, on microbial composition, microbial catabolic activity, gut health and beyond in pigs. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1735–1757. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8111735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhang Y., Gong Y., Zhang J., Li D., Tian Y., Han R., Guo Y., Sun G., Li W., Zhang Y., Zhao X., Zhang X., Wang P., Kang X., Jiang R. Fasting-induced molting impacts the intestinal health by altering the gut microbiota. Animals. 2024;14:1640–1654. doi: 10.3390/ani14111640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]