Abstract

Background:

The aim was to assess the impact of non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid (HA) injections on the healing of intraoral wounds from 3 types of incisions.

Methods:

A total of 36 Wister albino rats were included in this research. The rats were randomly assigned to 1 of 6 groups: the first group underwent a scalpel incision in the buccal mucosa with HA injection. The second group received a laser incision using a 976-nm diode laser with HA injection, whereas the third group was subjected to a laser incision with a 450-nm diode laser with HA injection. The fourth group underwent scalpel incision only, the fifth group received a 976-nm laser incision only, and the sixth group received a 450-nm laser incision only. Biopsies were collected at baseline, as well as on the third and seventh days, to assess wound healing using hematoxylin and eosin and Masson trichrome staining.

Results:

Group 3 exhibited the most pronounced results on the third and seventh days after surgery, with collagen formation noted alongside well-organized granulation tissue that contributed to improved and expedited wound healing.

Conclusions:

In this low-volume experimental study, HA injections in wounds made with a 450-nm diode laser demonstrated encouraging outcomes, enhancing the healing process and resulting in quicker recovery.

Takeaways

Question: Is non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid effective in promoting the healing process in oral wounds?

Findings: The proposed technique may offer an acceptable modality to aid in wound healing progression.

Meaning: The non-cross-linked hyaluronic acid injection was found to provide optimum healing for oral wounds.

INTRODUCTION

Numerous adults experience oral wounds that can result from ulcerations, injuries, or orofacial operations, all of which affect patients’ quality of life.1–3 The healing process for oral wounds differs from that of skin wounds, demonstrating a reduced proinflammatory response during recovery, which allows for a quicker self-repair compared with skin injuries. Nevertheless, the presence of saliva and the fluctuating conditions in the oral cavity may hinder the healing of these wounds.4,5

Numerous instruments have been recommended for making incisions in oral surgery, including traditional scalpels, the 976-nm diode laser, and the 450-nm diode laser. Using blades can result in significant bleeding and a risk of scarring, but they do not inflict thermal injury on the surrounding tissues.6 Conversely, the 976-nm diode laser has shown effective surgical results with minimal peripheral tissue damage.7 In contrast, the 450-nm diode laser has proven to be highly effective for surgical procedures on oral soft tissues without adverse effects for patients.8 Additionally, research indicated that the 450-nm diode laser provides a high level of tissue vaporization while limiting tissue coagulation.9

Hyaluronic acid (HA) consists of alternating units of the repeating disaccharide β-1,4-d-glucuronic acid-β-1,3-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, which is broadly found throughout the body and serves as a crucial element of the extracellular matrix (ECM).10 HA is essential in the wound healing process. The growing interest in HA products stems from their diverse biological activities and various physiological functions. HA has the capability to maintain a moist environment that facilitates healing and encourages the proliferation of growth factors, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes. Highly hydrophilic nature of HA allows it to absorb exudate and improve cell migration. It has positive effects on wound healing, leading to reduced inflammation, better tissue remodeling, and enhanced angiogenesis.11

Although data are available on the use of blades, the 976-nm diode laser, and the 450-nm diode laser for surgical interventions, not enough existing studies have compared the effect of non-cross-linked HA injection on the wound healing rates produced by these devices within a single research effort up to this point. Therefore, this study sought to assess the impact of non-cross-linked HA injection after the use of each instrument on the healing of oral wounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research involved 36 adult Wistar albino rats of the species Rattus norvegicus, which were matched for age and weight (4–6 mo old and weighing between 110 and 170 g), sourced from the animal facility at the Faculty of Science, Cairo University. The rats were given a week-long period before the experiments to acclimatize to the laboratory environment. They were provided with food and water ad libitum, with fresh supplies delivered daily. This study received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cairo University, with the approval number CU I F 34 24. Following general anesthesia, all rats were randomly assigned to 1 of 6 groups. Each group contained 6 rats, and equal number of rats were killed in each group at each time interval (baseline, third postoperative day, and seventh postoperative day):

Group 1: A scalpel was used to make a 2-mm cut in the buccal mucosa, followed by non-cross-linked HA injection in the wound bed and along the wound edges.

Group 2: A 2-mm cut was made in the buccal mucosa using a 976-nm diode laser, followed by non-cross-linked HA injection in the wound bed and along the wound edges.

Group 3: A 2-mm cut was made in the buccal mucosa using a 450-nm diode laser, followed by non-cross-linked HA injection in the wound bed and along the wound edges.

Group 4: A scalpel was used to make a 2-mm cut in the buccal mucosa without any further intervention (control group).

Group 5: A 2-mm cut was made in the buccal mucosa using a 976-nm diode laser without any further intervention (control group).

Group 6: A 2-mm cut was made in the buccal mucosa using a 450-nm diode laser without any further intervention (control group).

The laser apparatus used in this research was the fiber optic–delivered diode laser (LX16, Guilin Woodpecker Medical Instrument Co., Ltd, China). The laser device has 3 wavelengths, 2 of which were used in this study (450 and 976 nm wavelengths), with all laser parameters standardized across the different wounds created, regardless of their varying wavelengths, delivering a power of 2 W in continuous mode for 2 seconds. Furthermore, every group received identical amounts of non-cross-linked HA injections, which was 0.01 mL, and the product used was Monalisa Skin (Genoss Co., Ltd, Korea). No postoperative dressings were used on any of the wounds, nor was any antibiotic ointment applied or suturing performed. A biopsy was conducted on all the rats under general anesthesia; this occurred immediately after the procedure and again on the third and seventh postoperative days for evaluation purposes. The histological analysis of wound healing was carried out using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson trichrome (MT) staining.

Microscope examination images were captured by Labomed trinocular inverted phase contrast microscope (TCM400) and the Atlas 16MP CMOS USB camera software (Labomed). The magnification power is 10×, with a scale bar of 50 µm. The MT-stained sections were analyzed using the Labomed fluorescence microscope LX400 (cat no: 9126000) and Labomed camera software.

Statistical Analysis

Numerical data were explored for normality by checking the data distribution, calculating the mean and median values, and using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Data showed a parametric distribution, represented by mean and SD values. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to study the effect of different tested variables and their interaction. Comparison of main and simple effects was done using pairwise t tests with Bonferroni correction. The significance level was set at a P value of 0.05 or less for all tests. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26 for Windows.

RESULTS

The results of the baseline samples for H&E stain analysis were as follows: group 1 displayed clean, crisp borders where the epithelium was separated from the underlying tissue. A small amount of bleeding was seen in the tissues, and the mucosal damage spread farther into the surrounding tissue. The primary cause of the larger incision zone in group 2 was thermal damage, which led to notable coagulative necrosis at the edges of the wound. Because the blood vessels were cauterized, there was only slight bleeding, and thermal damage that penetrated deeper into the surrounding tissue. In comparison, wounds made with a 450-nm diode laser in group 3 exhibited less thermal damage, with cut edges that displayed extensive coagulative necrosis and tissue dehydration.

On the third day, the connective tissue displayed significant edema, reepithelialization was delayed, and there was a noticeable inflammatory infiltration in group 1 samples, which was dominated by neutrophils and macrophages. At this point, fibroblast activity was beginning, but the rate of healing was delayed. Group 2 also displayed a marked inflammatory response with substantial macrophage infiltration, and the wound margins showed slower reepithelialization with significant connective tissue edema. Group 3 samples revealed a mild inflammatory response, with macrophage cells predominating and neutrophil activity being lower. Early reepithelialization was also evident, and the surrounding connective tissue displayed mild fibroblast proliferation. At this stage, tissue repair seems to be more controlled than in the other groups.

Group 1 demonstrated reepithelialization on the seventh day. Tissue maturation was accelerated by the apparent advancement in collagen organization. Angiogenesis and mild inflammation were also visible. Group 2 displayed almost total reepithelialization, with a thin but continuous layer of new epithelium covering the wound; organized collagen deposition and fibroblast activity in the connective tissue were prominent; inflammation was low; and the tissue displayed good organization and visible angiogenesis. Reepithelialization was evident in group 3 samples, in addition to a significant collagen deposition; moreover, fibroblast activity was observed in the connective tissue, and the healing process was more developed and well structured.

Group 4 baseline samples (H&E) showed an incision with clean, sharp margins and a well-defined wound with immediate disruption of epithelial layer and connective tissue, including hemorrhage and inflammatory cell infiltration. The surrounding tissue showed no significant changes apart from the mechanical disruption. On the third day, there was an evidence of acute inflammation, characterized by the presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, especially neutrophils, within the wound area. The epithelial layer appeared disrupted, and early reepithelialization was noted at the wound edges, associated with new vessel formation. The connective tissue showed edema and some early fibroblast proliferation. On the seventh day after incision, the samples showed that the reepithelialization was more advanced, with epithelial cells covering a larger portion of the wound. The underlying connective tissue showed an increased fibroblast activity, with new collagen deposition and fewer inflammatory cells. Angiogenesis (new blood vessel formation) was more prominent, which means there was a state of active wound healing.

H&E stain for the fifth group also showed that baseline samples had cut edges with extensive coagulative necrosis and tissue dehydration when compared with the incision performed using the 450-nm diode laser. On the third day postincision, the inflammation was more pronounced, with delayed granulation tissue formation. Fibroblast activity was noticed, but epithelial proliferation was slower compared with both blade and 450-nm diode laser incisions. Samples taken on the seventh day postincision showed that the wound healing was progressing but remained delayed compared with wounds created with the 450-nm diode laser. Reepithelialization was incomplete, and collagen deposition was less organized, reflecting prolonged tissue damage and remodeling.

Furthermore, in the sixth group, the H&E stain of baseline samples showed a zone of injury, which caused a significant coagulative necrosis at the wound margins, and there was minimal bleeding due to cauterization of blood vessels. Examination of the third-day samples showed a mild inflammatory response, reepithelialization was visible, and the connective tissue showed prominent fibroblast activation. Edema was limited to the surrounding tissue. Samples taken on the seventh day revealed that the reepithelialization progressed more slowly with more prominent fibroblast and collagen activity compared with blade-induced wounds. There was more evidence of delayed tissue remodeling and inflammation subsiding.

Baseline samples from group 1 revealed a disruption of the collagen network at the site of the incision, according to MT analysis. Collagen deposition began earlier on the third day, as evidenced by more ordered, blue-stained fibers. There was increased fibroblast activity and neovascularization, and the granulation tissue seemed denser. There appeared to be increased structure in the ECM, which suggests early tissue remodeling. Collagen fibers were well organized in the samples collected on the seventh day, and the wound region had denser and more consistent blue-green staining. HA encouraged the production of more mature collagen.

Furthermore, MT analysis for group 2 baseline samples displayed less blue staining at the incision site; nevertheless, on the third day, collagen deposition progressed, and better-formed blue-stained fibers were visible. Granulation tissue was denser and the ECM had indications of organization. Neovascularization was more noticeable, and fibroblast activity was increased. Collagen fiber organization and improved blue-green staining on the seventh day indicated a more advanced stage of wound healing. Tissue contraction was more noticeable.

Additionally, baseline samples from group 3 showed damaged collagen fibers in MT analysis, and the stain showed less blue-green staining because the collagen matrix was destroyed. Collagen deposition became more noticeable on day 3, as seen by the granulation tissue’s enhanced blue staining. The overall tissue architecture was stabilized, and the ECM displayed improved organization. On the seventh day, however, the blue-green staining was more vivid and the collagen deposition was more organized, indicating advanced ECM remodeling.

Baseline samples of the fourth group showed a disruption of collagen fibers within the connective tissue, with clear demarcation between the injured and uninjured areas. The incision site showed minimal collagen staining (pink-red), whereas the surrounding tissue retained a dense blue-green collagen network. On the third day, granulation tissue started to form, characterized by loose collagen fibers (light blue staining) and increased cellularity. Collagen deposition was beginning, but the fibers were disorganized. On the seventh day postincision, collagen deposition became more pronounced, with thicker and more organized fibers visible in the wound area. The blue-green staining in the MT indicated maturing collagen.

MT stain for baseline samples taken from group 5 showed a large area of necrosis and disruption of the collagen matrix. The collagen fibers appeared fragmented or absent. On the third day postincision, collagen regeneration was slower, with disorganized and loosely arranged fibers. The blue staining in the granulation tissue was less intense, and fibroblast activity was delayed. The ECM remained highly disorganized, and the overall tissue architecture was poorly defined. Samples taken on the seventh day postincision showed that collagen deposition was visible but still less organized compared with other groups. The blue-green staining showed mild intensity, reflecting the delayed tissue remodeling due to the higher degree of thermal damage. Wound healing remained slower, with ongoing fibrosis.

Moreover, samples taken from group 6 at the baseline interval showed that the collagen fibers were disrupted, and the stain showed a reduced blue-green staining due to the destruction of the collagen matrix. On the third day, the collagen regeneration was active, and the granulation tissue appeared more organized compared with the blade incisions; moreover, the collagen fibers were firmly arranged. MT stain examination on the seventh day showed that collagen deposition was visible, and the fibers were more well organized than in the blade-incised group and 976-nm diode laser–incised group. The MT stain for collagen analysis between groups showed the following:

Baseline: There was no statistically significant difference between groups according to collagen fiber (%). The ANOVA test revealed no statistically significant difference between groups (P = 0.286).

Three days: The highest mean value of collagen fiber (%) was recorded in group 3 (450 nm + HA), which was 36.33 ± 2.04, followed by group 1 (blade + HA) at 32.07 ± 3.30, then group 2 (976 nm + HA) at 29.05 ± 3.17, followed by group 6 (450 nm only) at 26.13 ± 3.51, then by group 4 (blade only) at 23.01 ± 3.61, and the lowest value was in group 5 (976 nm only) at 18.27 ± 1.93. The ANOVA test revealed a statistically significant difference between groups (P = 0.001).

Seven days: The highest mean value of collagen fiber (%) was recorded in group 3 (450 nm + HA), which was 54.83 ± 2.52, followed by group 1 (blade + HA) at 50.31 ± 4.17, then by group 2 (976 nm + HA) at 45.67 ± 3.43, followed by group 6 (450 nm only) at 40.27 ± 4.06, group 4 (blade only) at 35.67 ± 2.52, and the lowest value was in group 5 (976 nm only) at 30.16 ± 3.11. ANOVA test revealed a statistically significant difference between groups (P = 0.001). The previously described histological findings (H&E stain and MT stain) as well as the interpretation of those findings as descriptive data in terms of the percentage of the collagen fibers are presented in Figures 1–13 and Tables 1–3.

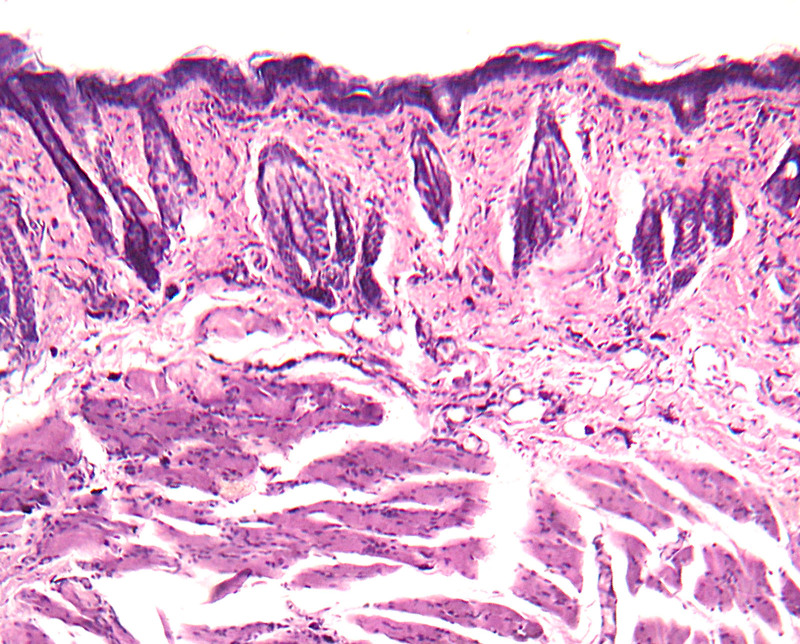

Fig. 1.

H&E stain for group 1 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 13.

Bar chart showing average collagen fiber for different groups at each time.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Collagen Fiber (%) of Different Groups

| Groups | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 d | 7 d | |

| Group 1 (blade + HA) | 4.17 ± 0.97 | 32.07 ± 3.30 | 50.31 ± 4.17 |

| Group 2 (976 nm + HA) | 4.05 ± 0.83 | 29.05 ± 3.17 | 45.67 ± 3.43 |

| Group 3 (450 nm + HA) | 3.42 ± 0.65 | 36.33 ± 2.04 | 54.83 ± 2.52 |

| Group 4 (blade only) | 3.53 ± 0.53 | 23.01 ± 3.61 | 35.67 ± 2.52 |

| Group 5 (976 nm only) | 4.08 ± 0.65 | 18.27 ± 1.93 | 30.16 ± 3.11 |

| Group 6 (450 nm only) | 4.04 ± 0.65 | 26.13 ± 3.51 | 40.27 ± 4.06 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SDs.

Table 3.

Multiple Comparisons Between Groups at Each Time Point Regarding Collagen Fiber (%), Using Bonferroni Correction Post Hoc

| Groups | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 d | 7 d | |

| Group (blade only) | |||

| Group (976 nm only) | 0.796 | 0.040* | 0.008* |

| Group (450 nm only) | 0.727 | 0.025* | 0.027* |

| Group (blade + HA) | 0.738 | 0.008* | 0.049* |

| Group (976 nm + HA) | 0.104 | 0.009* | 0.020* |

| Group (450 nm + HA) | 0.440 | 0.008* | 0.022* |

| Group B (976 nm only) | |||

| Group (450 nm only) | 0.476 | 0.006* | 0.047* |

| Group (blade + HA) | 0.683 | 0.006* | 0.010* |

| Group (976 nm + HA) | 0.121 | 0.007* | 0.009* |

| Group (450 nm + HA) | 0.944 | 0.008* | 0.023* |

| Group (blade + HA) | 0.377 | 0.026* | 0.008* |

| Group (976 nm + HA) | 0.815 | 0.042* | 0.009* |

| Group (450 nm + HA) | 0.920 | 0.007* | 0.007* |

| Group G (blade + HA) | |||

| Group (976 nm + HA) | 0.691 | 0.014* | 0.044* |

| Group (450 nm + HA) | 0.230 | 0.023* | 0.009* |

| Group H (976 nm + HA) | |||

| Group (450 nm + HA) | 0.267 | 0.040* | 0.008* |

Significant, P < 0.05; nonsignificant, P > 0.05.

Table 2.

Results of 2-way ANOVA and Post Hoc Tests Comparing Collagen Fiber (%) Between Different Groups and Different Time Points

| Groups | Time | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 d | 7 d | ||

| Group 1 (blade + HA) | 4.17 ± 0.97 aA | 32.07 ± 3.30 cB | 50.31 ± 4.17 cC | 0.001* |

| Group 2 (976 nm + HA) | 4.05 ± 0.83 aA | 29.05 ± 3.17 bcB | 45.67 ± 3.43 bcC | 0.001* |

| Group 3 (450 nm + HA) | 3.42 ± 0.65 aA | 36.33 ± 2.04 dB | 54.83 ± 2.52 dC | 0.001* |

| Group 4 (blade only) | 3.53 ± 0.53 aA | 23.01 ± 3.61 bB | 35.67 ± 2.52 aC | 0.001* |

| Group 5 (976 nm only) | 4.08 ± 0.65 aA | 18.27 ± 1.93 aB | 30.16 ± 3.11 aC | 0.001* |

| Group 6 (450 nm only) | 4.04 ± 0.65 aA | 26.13 ± 3.51 bcB | 40.27 ± 4.06 bC | 0.001* |

| P | 0.286 | 0.001* | 0.001* | |

Different small letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) among means in the same column. Different capital letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) among means in the same row. Data are expressed as mean ± SDs.

Significant, P < 0.05; nonsignificant, P > 0.05.

Fig. 2.

H&E stain for group 2 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 3.

H&E stain for group 3 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 4.

H&E stain for group 4 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 5.

H&E stain for group 5 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 6.

H&E stain for group 6 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 7.

MT stain for group 1 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 8.

MT stain for group 2 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 9.

MT stain for group 3 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 10.

MT stain for group 4 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 11.

MT stain for group 5 (seventh-day sample).

Fig. 12.

MT stain for group 6 (seventh-day sample).

DISCUSSION

Wound healing involves multiple stages, and any disruption in these stages can lead to impaired healing. Consequently, various treatment options have been proposed to facilitate the healing process.6–9 In this study, 3 incisions were made in the buccal mucosa of rats using 3 distinct methods: a scalpel, a 450-nm diode laser, and a 976-nm diode laser. This was followed by the injection of non-cross-linked HA at the wound bed and along the wound edges. All wounds were allowed to heal by secondary intention, without the use of sutures or dressings that could potentially influence the outcomes and evaluation methods used.

The group that underwent an incision made with a 450-nm diode laser followed by non-cross-linked HA injection demonstrated the most favorable healing pattern among all groups observed. Consequently, using this particular wavelength in addition to injecting HA for intraoral incisions may yield a more satisfactory healing outcome compared with other incision techniques, specifically those using a scalpel or a 976-nm diode laser.

The results obtained were consistent with findings from other studies that demonstrated the effectiveness of using a 450-nm diode laser wavelength in oral soft tissue surgical procedures. This method not only exhibits high efficacy in tissue vaporization but also minimizes tissue coagulation.8–13

The application of the 976-nm diode laser in this research has demonstrated the capability to induce thermal damage in the tissue samples, as assessed through histological evaluation. These results contrast with those reported by Palaia et al7 in 2021, which indicated that the 976-nm diode laser resulted in minimal thermal damage and limited peripheral injury at the cut edges. Conversely, Al-Ani et al14 in 2024 reported that the 980-nm diode laser caused tissue damage due to thermal effects, aligning with the observations made in our study. The results of our study showed that the thermal effect of this specific wavelength might have a negative impact on the stability and accelerate the degradation of the HA, thus compromising the effect of HA on wound healing. That is why the use of HA with the 976-nm diode laser exhibited the least prognosis compared to the other study groups.

It was observed that group 3 exhibited a pronounced development of collagen fibers compared with the other study groups, accompanied by a significant increase in the formation of new endothelial cells. This resulted in a more rapid healing process than that observed in the other groups. These findings align with the results obtained in a study conducted by Etemadi et al15 in 2020. This study presented several limitations, including the absence of measurements for liquefaction necrosis, epithelial migration, and fibroblast activity. Therefore, it is essential to promote further research that addresses these aspects, along with a comparative analysis of various laser wavelengths. Such investigations are necessary to establish evidence-based practices for selecting a specific wavelength for diode lasers in intraoral incisions, aimed at enhancing the healing process.

CONCLUSIONS

A promising technique seems to be the injection of non-cross-linked HA following 450-nm diode laser incisions. Additionally, we observed that oral wounds made with this particular wavelength had a superior healing pattern to wounds made with a scalpel and diode laser set at 976 nm. Therefore, it is highly advised to conduct more research in addition to patient clinical trials to better explore the latter strategy.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Published online 6 May 2025.

Disclosure statements are at the end of this article, following the correspondence information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dudding T, Haworth S, Lind PA, et al. ; 23andMe Research Team. Genome wide analysis for mouth ulcers identifies associations at immune regulatory loci. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, et al. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:661–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toma AI, Fuller JM, Willett NJ, et al. Oral wound healing models and emerging regenerative therapies. Transl Res. 2021;236:17–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamont RJ, Koo H, Hajishengallis G. The oral microbiota: dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:745–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hearnden V, Sankar V, Hull K, et al. New developments and opportunities in oral mucosal drug delivery for local and systemic disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:16–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loh SA, Carlson GA, Chang EI, et al. Comparative healing of surgical incisions created by the PEAK PlasmaBlade, conventional electrosurgery, and a scalpel. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1849–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palaia G, Renzi F, Pergolini D, et al. Histological ex vivo evaluation of the suitability of a 976 nm diode laser in oral soft tissue biopsies. Int J Dent. 2021;2021:6658268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fornaini C, Rocca JP, Merigo E. 450 nm diode laser: a new help in oral surgery. World J Clin Cases. 2016;4:253–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang D, Liu G, Yang B, et al. 450-nm blue diode laser: a novel medical apparatus for upper tract urothelial lesions. World J Urol. 2023;41:3773–3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He C, Bi S, Zhang R, et al. A hyaluronic acid hydrogel as a mild photothermal antibacterial, antioxidant, and nitric oxide release platform for diabetic wound healing. J Control Release. 2024;370:543–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cortes H, Caballero-Florán IH, Mendoza-Muñoz N, et al. Hyaluronic acid in wound dressings. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2020;66:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fornaini C, Merigo E, Rocca JP, et al. 450 nm blue laser and oral surgery: preliminary ex vivo study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016;17:795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fornaini C, Fekrazad R, Rocca JP, et al. Use of blue and blue-violet lasers in dentistry: a narrative review. J Lasers Med Sci. 2021;12:e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Ani AJ, Taher HJ, Alalawi AS. Histological evaluation of the surgical margins of oral soft tissue incisions using a dual-wavelength diode laser and an Er, Cr:YSGG laser; an ex vivo study. J Appl Oral Sci. 2024;32:e20230419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etemadi A, Taghavi Namin S, Hodjat M, et al. Assessment of the photobiomodulation effect of a blue diode laser on the proliferation and migration of cultured human gingival fibroblast cells: a preliminary in vitro study. J Lasers Med Sci. 2020;11:491–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]