Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis

Symptomatic pedunculated leiomyomas in pregnancy; review of the literature with special consideration of an example case.

Study design

Retrospective narrative review with an example case.

Methods

Systematic evaluation of 37 reports.

Example case

A 36-year-old Caucasian primigravida was referred symptomatic at 16 + 0 weeks due to a 13,5 cm myoma causing pain, constipation, urine retention and dysesthesias. Our patient underwent myomectomy at 17 + 0 weeks. One pedunculated leiomyoma was successfully removed.

Conclusion

Myomectomy can be performed and is safe for pedunculated fibroids in pregnancy. Depending on the clinical scenario, surgical removal may be indicated. Based on the size of the fibroids and expected adhesions, a laparotomy is a safe option and is not a contraindication for vaginal birth in the case of pedunculated fibroids. Myomas larger than 10 cm should be removed by laparotomy.

Keywords: Myomectomy, Pregnancy, Pedunculated myoma, Fibroids, Laparotomy, Laparoscopy

Introduction

Leiomyomas are the most common (20–40%) benign disease affecting the female reproductive system. The prevalence of leiomyomas in pregnancy is 2–10% and is usually asymptomatic, but 10% of patients develop complications in pregnancy [1]. Pain is often seen in women with fibroids > 5 cm [2]. In early pregnancy the volume of fibroids increases by 12% in volume because of the rapid increase in serum chorionic gonadotropin levels [3]. Only 37 pedunculated fibroids during pregnancy with single myomectomy are reported in the literature [4].Complication risk does increase with the number of fibroids, size, relation to the placenta and location [4]. Pain is related to the blood supply of the fibroid because increased growth can result in insufficient blood supply followed by necrosis [2].

Example case presentation

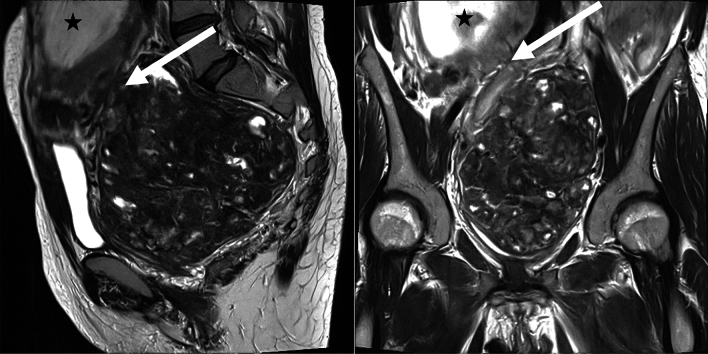

A 36-year-old primigravida presented to our University Hospital in January 2024 with a one-year history of chronic hematochezia, which had been treated with oral iron supplementation. The patient had been in the 16 + 0 weeks of gestation with a viable fetus (single, intra-uterine). The patient reported flank pain and micturition disorder. Diagnostic work-up included transabdominal ultrasound which identified a previously unknown pelvic mass. MR imaging was performed for better delineation and characterization of the mass. A 13.5 × 13 cm measuring pedunculated sub-serosal leiomyoma was diagnosed, originating from the posterior wall of the uterus. The lower abdominal organs had been shifted upwards with a compression-related urinary stasis III° on the left side and a compression of the common iliac vein (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative MRI. T2-weighted images in the sagittal and coronal plane depicts a pedunculated sub serosal Leiomyoma (arrowhead) and the fetus (asterisk). The vascular pedicle visualized by worm-like signal-free vessels (arrowhead) suggests an attachment side of the leiomyoma to the posterior wall of the uterus. Degenerative changes (white spots) are seen within the leiomyoma

The uterine leiomyoma had not been diagnosed before the pregnancy, because the patient has not undergone regular screenings. The pregnancy had been developing physiological. After interdisciplinary discussion prophylactic low molecular weight heparin was prescribed. The patient developed dysesthesia in the left leg in the following weeks. Because of the increasing symptoms a conservative vs. surgical therapy was discussed with the patient. Double-J catheters had been inserted prior to surgery. Because of declining hemoglobin levels, two erythrocyte concentrates had been transfused.

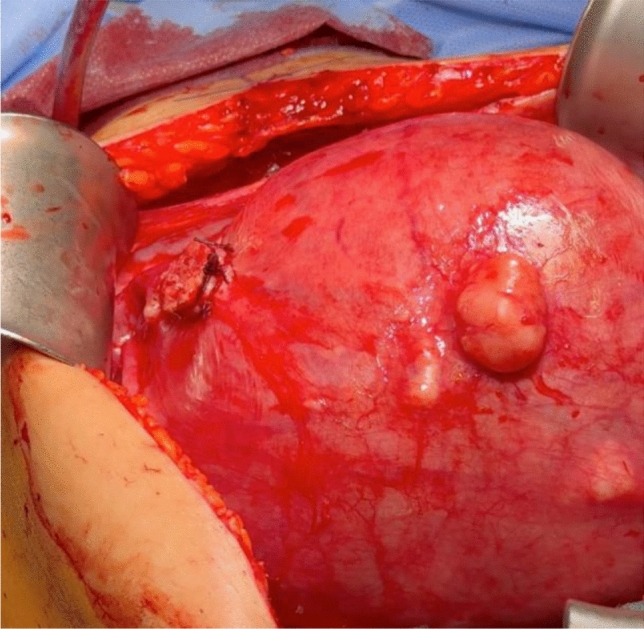

On 24/01/2024 a longitudinal laparotomy was performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. Operative findings included normal liver, spleen, kidneys, diaphragm, ovaries and fallopian tubes. The uterus was soft and the size was adequate for 17 + 0 weeks of gestation. Fetal movements were visible. A pedunculated fibroid without a torsion measuring 13,5 cm in diameter filled out the whole lower sacral cavity. The pedicle was originating from the dorsal uterus with a stalk diameter of 2 cm. The fibroid was adherent to the peritoneum and sigmoid colon. It was detached and the pedicle was cut after ligation with several sutures 2-0 vicryl. After myomectomy, the pedicle was found to originate from the anterior wall of the uterus and had been turned during pregnancy dorsally. The estimated blood loss was 400 ml and the time of the surgery was 85 min. The tumor weighted 740 g and was sent for pathology. Pre-, intra- and postoperative performed sonographic vital controls of the fetus revealed normal findings (Fig. 2, 3).

Fig. 2.

Stump of the pedicle

Fig. 3.

Myoma

Postoperatively, the patient was given indomethacin prophylactically to prevent uterine contractions. In the Further course, there was a slight neuropathy of the left leg, which after further diagnostics using MRI was most likely interpreted as the expression of an irritation caused by the pressure of the fibroid. There were no further abnormalities.

The symptoms improved and the patient was discharged from the hospital 10 days after the operation. The histological findings showed a leiomyoma with regressive changes and focal ischemic necrosis. There was no evidence of malignancy. The patient was followed up by us twice, and the pregnancy developed normally with no further complaints. Unfortunately, the patient decided to give birth in a rural hospital at 38 + 1 weeks’ gestation. Due to her history, a spontaneous labor was not performed and a secondary caesarean section was performed. A 3300 g baby with APGAR 9–10-10 was delivered. The patient was discharged after 4 days without complications.

The patient’s written consent to publication has been obtained.

Review of literature

Material and methods

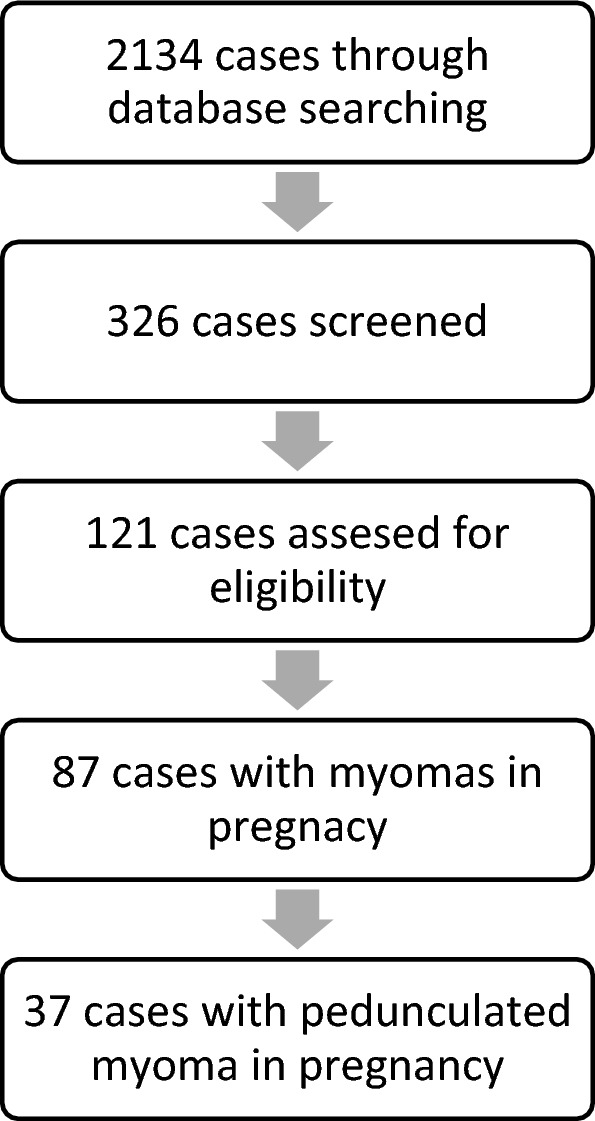

In March 2024, the search was carried out with various search terms in Pubmed® (Table 1). The initial search was for case reports and case descriptions of fibroids during pregnancy. Cases with myomectomy during cesarean section were excluded. The cases were then reduced to pedunculated fibroids. Vaginally pedunculated fibroids were excluded. A table was created and the following parameters were recorded for each case: Year of treatment, name of author, title of publication, age of patient, parity, week of pregnancy at first presentation, week of pregnancy at treatment, location of fibroid, symptoms, sonographic findings, MRI findings, size of fibroid, type of operation, special features of operation, blood loss, antibiotics, tocolysis, pneumoperitoneum, intraoperative torsion, pathological findings, weight of fibroid, time of discharge, type of birth, week of pregnancy at birth and other complications. The data collection was carried out by one author (B.J.) (Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Presentation of cases used for this review

| Author | Date | Age | Pregnancy | Gestational week of surgery | Location of myoma | Symptoms | Imaging | Type of operation | Myoma weight | Size of myoma | Type of birth | Week of birth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Makar et al. | 1989 | 14 | Posterior wall | Pelvic pain | Sonography | 120 mm | Vaginal | |||||

| Kalantaridou et al. | 1994 | 38 | 19 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | Longitudinal laparotomy | 1500 g | 37 | |||

| Pelosi et al. | 1995 | 35 | Primipara | 13 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK, free morcellation into abdominal cavity | 1500 g | 60 mm | Cesarean section for breech presentation | 39 |

| Sciannameo et al. | 1996 | 31 | 20 | MRI | ||||||||

| Majid et al. | 1997 | 35 | Multipara | 17 | Fundus | Gastrointestinal symptoms | Sonography | 240 mm | Intrauterine fetal death | 19 | ||

| Luxman et al. | 1997 | 27 | Primipara | 15 | Fundus | Sonography | LSK, free morcellation into abdominal cavity | 80 mm | Vaginal | 39 | ||

| Kalantaridou et al. | 1999 | 25 | 16 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | 170 g | 39 | ||||

| Wittich et al. | 2000 | 31 | Primipara | 15 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography + MRI | Longitudinal laparotomy | 2074 g | 205 mm | Elective cesarean section | 37 |

| Kalantaridou et al. | 2001 | 25 | 16 | Anterior wall | Pelvic pain | Sonography + MRI | 625 g | 39 | ||||

| Sentilhes et al. | 2003 | 35 | Multipara | 17 | Left lateral wall | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK, free morcellation into abdominal cavity | 50 mm | Elective cesarean section | 37 | |

| Melgrati et al. | 2005 | 29 | Primipara | 24 | Fundus | Pelvic pain, fever | Sonography | Isobaric Laparoscopy | 70 mm | Vaginal | 39 | |

| Dracea et al. | 2006 | 39 | Multipara | 14 | Fundus | Sonography | Transverse Laparotomy | 240 mm | Vaginal | 37 | ||

| Usifo et al. | 2007 | 31 | Primipara | 13 | Posterior wall | Pelvic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms | Sonography | Transverse Laparotomy | 168 mm | Elective cesarean section | 38 | |

| Okokwo et al. | 2007 | 40 | 19 | Fundus | Lower extremity edemas | Sonography | Longitudinal laparotomy | 10,000 g | 280 mm | Elective cesarean section | 38 | |

| Leite et al. | 2007 | 43 | Primipara | 17 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | Longitudinal laparotomy | 91 mm | Vaginal | 39 | |

| Alanis et al. | 2008 | 22 | Multipara | 13 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | MRI | Longitudinal laparotomy | 8000 g | 300 mm | Vaginal | 38 |

| Suwandinata et al. | 2008 | 28 | Primipara | 15 | Posterior wall | Pelvic pain | Sonography | Longitudinal laparotomy | 320 g | 80 mm | Elective cesarean section | 37 |

| Camacho et al. | 2009 | 35 | Multipara | 16 | Posterior wall | Pelvic pain, fever | Sonography | Longitudinal laparotomy | 62 mm | Vaginal | 40 | |

| Bhatla et al. | 2009 | 30 | Primipara | 20 | Fundus | Pelvic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms | Sonography | Longitudinal laparotomy | 3900 g | 280 mm | Vaginal | 38 |

| Fanfani et al. | 2010 | 39 | Primipara | 25 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK, Endo bag extraction | 95 g | 90 mm | Vaginal | 40 |

| Son et al. | 2011 | 31 | Primipara | 18 | Posterior wall | Sonography + MRI | LSK, Endo bag extraction | 108 g | 90 mm | Vaginal | 39 | |

| Ardovino et al. | 2011 | 31 | Multipara | 14 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK, free morcellation into abdominal cavity | 127 g | 63 mm | Vaginal | 40 |

| Pelissier-Komorek et al. | 2012 | 34 | Primipara | 10 | Fundus | Pelvic pain, dyspnea | Sonography + MRI | Longitudinal laparotomy | 2040 g | 220 mm | Vaginal | 35 |

| Doerga-Bachasing et al. | 2012 | 33 | Multipara | 10 | Posterior wall | Pelvic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms | Sonography + MRI | Longitudinal laparotomy | 175 mm | Cesarean section | 40 | |

| Macció et al. | 2012 | 33 | Primipara | 19 | Fundus | Pelvic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, vaginal bleeding | Sonography | LSK, Endo bag extraction | 250 g | 150 mm | Elective cesarean section with FGR | 39 |

| Macció et al. | 2012 | 24 | Primipara | 20 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK, Endo bag extraction | 170 g | 100 mm | Vaginal | 40 |

| Macció et al. | 2012 | 34 | Primipara | 20 | Anterior wall | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK, Endo bag extraction | 240 g | 40 mm | Vaginal | 39 |

| Tabandeh et al. | 2012 | 30 | Primipara | 24 | Fundus | Pelvic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms | Sonography + MRI | Longitudinal laparotomy | 230 mm | Elective cesarean section | 37 | |

| Currie et al. | 2013 | 27 | Primipara | 11 | Anterior wall | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK with Pfannenstiel incision | 80 mm | |||

| Domenici et al. | 2013 | 35 | Primipara | 16 | Posterior wall | Pelvic pain, urinary habit changes | Sonography + MRI | Longitudinal laparotomy | 200 mm | Elective cesareans section | 38 | |

| Saccardi et al. | 2014 | 35 | Primipara | 15 | Anterior wall | Pelvic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms | Sonography | LSK, free morcellation into abdominal cavity | 1363 g | 240 mm | Cesarean section for fetal tachycardia | 41 |

| Anthimides et al. | 2015 | 31 | Multipara | 10 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK, Endo bag extraction | 77 mm | |||

| Algara et al. | 2015 | 36 | 18 | Pelvic pain | LSK | Intrauterine fetal death after car accident | ||||||

| Jhalta et al. | 2016 | 34 | Primipara | 14 | Fundus | Sonography | Longitudinal laparotomy | 160 mm | Vaginal | 39 | ||

| Kim et al. | 2016 | 35 | Primipara | 10 | Fundus | Pelvic pain | Sonography | LSK | 93 mm | Vaginal | 41 | |

| Basso et al. | 2017 | 36 | Multipara | 17 | Anterior wall | Pelvic pain | Sonography | Longitudinal laparotomy | 132 mm | Vaginal | 38 | |

| Our case | 2024 | 37 | Primipara | 18 | Anterior wall | Pelvic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, urinary habit changes | Sonography + MRI | Longitudinal laparotomy | 740 g | 135 mm | Secondary caesarean section | 39 |

Fig. 4.

Overview of the review process

Statistics

The statistical analysis was performed using data from eligible studies to assess the overall effect sizes and heterogeneity. Effect measures, such as odds ratios (OR) and risk ratios (RR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI), were calculated for binary outcomes, while mean differences (MD) were used for continuous outcomes. Funnel plots and Egger’s regression test were conducted to assess potential publication bias, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

2134 cases were found and 326 of them further screened. 121 cases had been eligible, but only 87 of them had myomectomies during pregnancy. All cases before the introduction of ultrasound diagnostics were excluded. The oldest included case was from 1989 [5], seven cases were before 2000 [6–10], twelve cases between 2000 and 2010 [6, 11–21] and 17 cases since 2010 to date [22–36]. The most recent case was from 2017 [36]. 37 cases reported about pedunculated myomas during pregnancy. One study was translated into Spanish. The remaining cases were in English. We include our above-mentioned case in the systematic review.

Demography

The age was noted in 37 [6–23, 23–36] of the 38 cases. The average age was 32.7 years (± 4.72; 22–43 years). 55.3% (n = 21) were primipara [7, 10, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21–23, 26, 28–31, 34, 35] and 26,3% (n = 10) of the patients had already been pregnant once [9, 12, 14, 18, 20, 25, 27, 32, 36], whereby no information was provided in 7 case reports [5, 6, 8, 16, 33].

Symptomatology and diagnosis

On average, the patients presented at 14.97 weeks of pregnancy (± 4.38; range: 7–25). Only one patient [14] showed no symptoms at all and no information about the symptoms was reported in three patients [8, 10, 24]. 81.6% (n = 31) of the patients reported pelvic pain. In addition, 18.4% (n = 7) had gastrointestinal symptoms in combination or alone [9, 15, 21, 22, 27–29]. Urinary habit changes were reported in 5.3% (n = 2) of cases [31]. Fever, edema of the lower extremities or vaginal bleeding were also described in 2.6% (n = 1) [16, 20, 28].

71.1% (n = 27) of the patients had only a preoperative sonography [5–7, 9, 10, 12–17, 19–23, 25, 28, 30, 32, 34–36], with 5,3% (n = 2) having an MRI [8, 18] and only 18,4% (n = 7) having an MRI and sonography [11, 26–29, 31]. No examination was documented in one patient [33].

A pedunculated fibroid was diagnosed preoperatively in 14 ultrasound findings [5, 6, 14, 22, 25, 27, 28, 35], with 22 findings not describing a pedicle. 55.3% (n = 21) of the fibroids originated from the fundus, [6, 7, 9–11, 13, 14, 16–18, 21, 23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 32, 34, 35] followed by 21.1% (n = 8) from the posterior wall [5, 15, 19, 20, 27, 28, 31]. 15.8% (n = 6) were on the anterior wall [22, 28, 30, 36] and only one fibroid (2.6%) was lateral to the uterus [12].

A sub-serosal fibroid was described in all MRI examinations, [8, 11, 17, 24, 27, 29, 31] whereby a torsion could already be detected in one finding [8]. At least one further fibroid was diagnosed in 28,9% (n = 11) of the patients [6, 9, 14, 19, 26, 28, 31, 36]. 21% (n = 8) of patients showed multiple uterine fibroids [6, 9, 26, 28, 36].

Management

No case report could be found that describes a wait-and-see approach.

47.4% (n = 18) of the patients underwent open surgery, [6, 11, 14–21, 26, 27, 29, 31, 34, 36] with a longitudinal laparotomy being performed in 42.1% (n = 16) of cases [6, 11, 16–21, 26, 27, 29, 31, 34, 36] and a transverse laparotomy in 5.3% (n = 2) [14, 15]. Laparoscopy (LSK) was performed in 39.5% (n = 15) [7, 10, 12, 13, 22–25, 28, 30, 32, 33, 35].

Significantly (p = < 0.001), larger fibroids underwent laparotomy and smaller fibroids underwent LSK. There was also a significance (p = 0.018) between the weight of the fibroid and the type of surgery. Patients who underwent open surgery had fibroids that were on average 181.71 mm (± 71.64 mm; 62–300 mm) in size and 3571.8 g (± 3556 g; 320–10.000 g) in weight. In contrast, the patients with LSK had 91.6 cm (± 50.13 cm; 40–240) measuring fibroids and lighter fibroids weighing 481.6 g (± 590.1 g; 95–1500 g). Surprisingly, the transverse laparotomy was more likely to yield heavy fibroids (204 g; ± 50.9 g) than longitudinal laparotomy (178.8 g; ± 78.4 g).

In only 8 patients the time between the first presentation and the surgical treatment documented [11, 18, 20–22, 27, 29]. For these, the average time span was 6.25 weeks (± 4.13; 1–12 weeks). We assume that the weeks of pregnancy stated in the case report also correspond to the time of surgical treatment. Thus, on average, the patients underwent surgical intervention at 16.3 weeks of pregnancy (± 3.78; 10–25). Blood loss was reported in 17 patients, [7, 9, 13, 15, 16, 19, 21, 22, 25, 27, 28, 28, 31, 35] with a mean value of 607 ml (± 1.076 ml; 0–4.500 ml) and thus a very wide range. Nevertheless, only one patient is described as requiring a postoperative transfusion [21]. No antibiotics were discussed in 17 patients, [5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 15–17, 26–29, 33] so that 26.3% (n = 10) received antibiotics [12, 14, 18, 19, 21, 31, 34, 36] and 28.9% (n = 11) did not receive antibiotics [8, 10, 12, 21, 23–25, 30, 32]. Only one patient was described as having a post-operative infection with abscess development at the uterine scar. [12] This one patient had a laparoscopy and did not receive antibiotics intraoperatively [12].

26.3% (n = 10) patients received tocolysis pre- or postoperatively, [9, 11, 14, 17, 21, 29, 34, 36]. whereas 34.2% (n = 13) did not receive tocolysis [7, 12, 18–20, 22–25, 30–32, 35]. In 15 patients no information regarding tocolysis was documented [5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 15, 16, 26–28, 33]. No patient developed labor until postoperative discharge. Torsion of the fibroid was present in 26.3% (n = 10) of the cases. [9, 11, 15, 21, 30, 32, 33, 35], However, the majority of 55.3% (n = 21) had no torsion [6, 7, 11–13, 17, 19, 21–23, 25, 27–29, 31, 34]. Of the LSK patients, 4 underwent free morcellation into the abdominal cavity [7, 10, 12, 22, 25]. In 6 of the LSK patients, the fibroid was retrieved using an Endo bag [23, 24, 28, 32]. In one patient, attention was paid to isobaric pressure [13]. The intra-abdominal pressure during LSK was described in 11 patients [7, 10, 13, 19, 22–25, 28, 32] and was found to be 11.2 mmHg (± 1.687 mmHg; 10–14 mmHg) on average.

Histopathology

In 31 operations, a histopathological examination was subsequently performed [5, 7, 9, 11–13, 15–26, 28, 30–36]. This revealed a degenerative change in the fibroid in 41.9% (n = 13) of the patients [6, 12–14, 16–20, 26, 28, 35]. 20 fibroids were described as sub serosal [9, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25–28, 30–36], whereby the other cases did not document any such description regarding the localization.

Postoperative time

On average, patients were discharged 4.64 (± 2.99; 1–14) days after surgery.

81.3% (n = 31) had a complication-free postoperative course. Postoperative complications were described in only 10.5% (n = 4) of the patients [12, 21, 27, 36]. One patient developed an abdominal abscess [12], as mentioned above and one patient required a transfusion of two red blood cell coagulates [21]. One patient developed cervical insufficiency in the 21st week of pregnancy [36].

One child died in the immediate post-operative period after multiple myomas had been removed and an appendectomy was performed [9].

Delivery

On average, all other cases had a birth in the 38.6 (± 1.36; 35–41) week of pregnancy. Of these, 47.2% (n = 17) had a vaginal birth [5, 10, 13, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 23–26, 28, 34–36]. A cesarean section was performed in 30.6% (n = 11) of cases [7, 11, 12, 15, 16, 19, 22, 27–29, 31]. No case reported a reduced APGAR or postpartum abnormalities. Significantly (p = 0.002), the patients with laparotomy gave birth at 37.9 (± 1.26; 35–40) weeks gestation, whereas the patients with LSK gave birth at 39.4 (± 1.08; 37–41) weeks gestation. There was no significance in regard to the type of birth.

Discussion

Surgical interventions are avoided during pregnancy, if possible, but our case and review of the literature show that surgical interventions may be necessary in pregnant patients. Symptomatic pedunculated fibroids rarely occur in pregnancy but require a well prepared and considered treatment. Patients with the combination of sonography and MRI showed the lowest complication rate. This is also confirmed by the fact that visualization of a pedicle enabling a diagnosis of a pedunculated leiomyoma was mostly successful on MRI.

Our decision to perform open surgery was in line with the current literature. We conclude that fibroids larger than 10 cm should be treated by laparotomy. In addition, adhesions with the fibroid should always be considered and expected.

The complexity of our case, as well as the literature review, show that surgically experienced personnel are essential for these procedures. Even if there is a temptation to enucleate further fibroids, the cases to date confirm that only the symptomatic fibroid should be removed. Experienced anesthetists should be present, as blood loss of up to 4.5 L has been described. Patients receiving antibiotic therapy showed no further infection, which was also confirmed in our case. Transfusion is not often needed prior surgery [21]. Ligation of the stalk by means of vicryl sutures is the most commonly applied technique, followed by staplers and bipolar electrosurgical devices. Vaginal delivery mode is seen in single myomectomies by 30–45%, even though there is missing data about the pedunculated situation [37].

It is astonishing that neither in patients with tocolysis nor without tocolysis a labor induction kit was described in any case.

Torsion of a fibroid is rare but should be considered first, as further complications such as necrosis or septicemia can develop.

A primary cesarean section was not recommended in any of the cases. No complications were described in any of the vaginal births. This confirms previous literature that vaginal birth is possible after myomectomy without opening the uterine cavity [38].

Conclusion

Myomectomy can be performed safely for pedunculated fibroids in pregnancy. MRI is helpful for fibroid mapping and maybe considered when sonography is insufficient. Based on the size of the fibroids and expected adhesions, a laparotomy is a safe option and is not a contraindication for vaginal birth in case of pedunculated fibroids. Myomas larger than 10 cm should be removed by laparotomy.

Author contributions

J.B.; Conceptualization; Writing—original draft; Writing— review and editing; project administration; supervision. C.M.W.; Statistics method evaluation. D,C.; F.M.; E.B.; Writing—review and editing; data curation; supervision; visualization. S.M.; V.P.; data curation; investigation; formal analysis; supervision J,U.; G.F.: Project administration; Conceptualization; investigation; supervision; validation K.T.: Writing—review and editing; supervision; formal analysis; methodology.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors have not disclosed any funding.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

U.J. received travel money from pfm. C.D. is funded by Roche, AstraZeneca, TEVA, Mentor, and MCI Healthcare. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed consent and Ethical approval

Informed consent for research and publication purposes was obtained from the patient mentioned in the study before collecting data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Loverro G et al (2021) Myomectomy during pregnancy: an obstetric overview. Minerva Obstet Gynecol 73:646–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaima A, Ash A (2011) Fibroid in pregnancy: characteristics, complications, and management. Postgrad Med J 87:819–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milazzo GN, Catalano A, Badia V, Mallozzi M, Caserta D (2017) Myoma and myomectomy: poor evidence concern in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 43:1789–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spyropoulou K et al (2020) Myomectomy during pregnancy: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 254:15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schatteman Makar, Vergote (1989) Myomectomy during pregnancy: uncommon case report. Acta Chirurgica Belgica 89:212–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lolis DE (2003) Successful myomectomy during pregnancy. Hum Reprod 18:1699–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelosi MA, Pelosi MA, Giblin S (1995) Laparoscopic removal of a 1500-g symptomatic myoma during the second trimester of pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2:457–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madami Sciannameo (1996) Torsion of uterine fibroma associated with inguinal incarcerated hernia in pregnancy. Case Rep Minerva Obstetr Gynecol 48:501–504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majid M, Khan GQ, Wei LM (1997) Inevitable myomectomy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 17:377–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luxman D, Cohen JR, David MP (1998) Laparoscopic myomectomy during pregnancy. Gynaecol Endosc 7:105–107 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittich AC, Salminen ER, Yancey MK, Markenson GR (2000) Myomectomy during early pregnancy. Mil Med 165:162–164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sentilhes, L. et al. Laparoscopic myomectomy during pregnancy resulting in septic necrosis of the myometrium. [PubMed]

- 13.Melgrati L, Damiani A, Franzoni G, Marziali M, Sesti F (2005) Isobaric (gasless) laparoscopic myomectomy during pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 12:379–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dracea L, Codreanu D (2006) Vaginal birth after extensive myomectomy during pregnancy in a 39-year-old nulliparous woman. J Obstet Gynaecol 26:374–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usifo F, Macrae R, Sharma R, Opemuyi IO, Onwuzurike B (2007) Successful myomectomy in early second trimester of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 27:196–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okonkwo JEN, Udigwe GO (2007) Myomectomy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 27:628–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leite GKC et al (2010) Miomectomia em gestação de segundo trimestre: relato de caso. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 10.1590/S0100-72032010000400008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alanis MC, Mitra A, Koklanaris N (2008) Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging and antepartum myomectomy of a giant pedunculated leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol 111:577–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suwandinata FS, Gruessner SEM, Omwandho COA, Tinneberg HR (2008) Pregnancy-preserving myomectomy: preliminary report on a new surgical technique. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 13:323–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camacho EEV, Carranco EC, Herrera RGS (2009) Mioma pediculado torcido en una mujer embarazada Reporte de caso. Ginecología y Obstetricia de México [PubMed]

- 21.Bhatla N, Dash BB, Kriplani A, Agarwal N (2009) Myomectomy during pregnancy: a feasible option. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 35:173–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saccardi C et al (2015) Uncertainties about laparoscopic myomectomy during pregnancy: a lack of evidence or an inherited misconception? A critical literature review starting from a peculiar case. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 24:189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fanfani F et al (2010) Laparoscopic myomectomy at 25 weeks of pregnancy: case report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 17:91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Son CE et al (2011) A case of laparoscopic myomectomy performed during pregnancy for subserosal uterine myoma. J Obstet Gynaecol 31:180–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ardovino M et al (2011) Laparoscopic myomectomy of a subserous pedunculated fibroid at 14 weeks of pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Rep 5:545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelissier-Komorek A et al (2012) Fibrome et grossesse : quand le traitement médical ne suffit pas. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 41:307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doerga-Bachasingh S, Karsdorp V, Yo G, Van Der Weiden R, Van Hooff M (2012) Successful myomectomy of a bleeding myoma in a twin pregnancy. JRSM Short Reports 3:1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macciò A et al (2012) Three cases of laparoscopic myomectomy performed during pregnancy for pedunculated uterine myomas. Arch Gynecol Obstet 286:1209–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabandeh A, Besharat M Successful myomectomy during pregnancy.

- 30.Currie A, Bradley E, McEwen M, Al-Shabibi N, Willson PD (2013) Laparoscopic approach to fibroid torsion presenting as an acute abdomen in pregnancy. JSLS 17:665–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Domenici L et al (2014) Laparotomic myomectomy in the 16th week of pregnancy: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2014:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anthimidis G (2015) Laparoscopic excision of a pedunculated uterine leiomyoma in torsion as a cause of acute abdomen at 10 weeks of pregnancy. Am J Case Rep 16:505–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Algara AC et al (2015) Laparoscopic approach for fibroid removal at 18 weeks of pregnancy. Surg Technol Int 27:195–197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jhalta P, Negi SG, Sharma V (2016) Successful myomectomy in early pregnancy for a large asymptomatic uterine myoma: case report. Pan Afr Med J. 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.228.9890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim M (2016) Laparoscopic management of a twisted ovarian leiomyoma in a woman with 10 weeks’ gestation: case report and literature review. Medicine 95:e5319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basso A et al (2017) Uterine fibroid torsion during pregnancy: a case of laparotomic myomectomy at 18 weeks’ gestation with systematic review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2017:4970802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babunashvili EL et al (2023) Outcomes of laparotomic myomectomy during pregnancy for symptomatic uterine fibroids: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Med 12:6406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weibel HS, Jarcevic R, Gagnon R, Tulandi T (2014) Perspectives of obstetricians on labour and delivery after abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 36:128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]