Abstract

From 1992 to 1997, only six sporadic isolates of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis from patients with cases of gastroenteritis in southern Italy exhibited resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Five isolates produced SHV-12, and one isolate encoded a class C β-lactamase. The blaSHV-12 gene was located in at least two different self-transferable plasmids, one of which also carried a novel class 1 integron.

Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis is one of the dominant serotypes causing human disease in Europe (6). Most infections caused by serotype Enteritidis and other nontyphoid salmonellae result in self-limiting diarrhea and do not require antimicrobial treatment. However, invasive infections are fairly common in children, for which cases the broad-spectrum cephalosporins are the antibiotics of choice.

During the period 1990 to 1998, the Center for Enteric Pathogens in Palermo, Italy, typed approximately 1,000 salmonella isolates annually, 20% of which belonged to serotype Enteritidis. Of these, approximately 45% were of human origin (13). These had originated primarily from the two epidemiological sentinel hospitals the “G. Di Cristina” pediatric hospital of Palermo and the “Pugliese” hospital of Catanzaro. Phage type PT4 was predominant, represented by 70 to 80% of all isolates, depending on the year. Susceptibility testing, performed according to NCCLS standards by a disk diffusion method (14), showed resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins for only six isolates throughout the whole period. Five of these (S76, S78, S79, S86, and S88) belonged to phage type PT4, while the lysis pattern of the sixth (S87) did not conform to a standard type.

Five isolates (S78, S79, S86, S87, and S88) were resistant to ampicillin, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and aztreonam. They were also positive in the double-disk synergy test (DDST) (10), indicating production of an extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL). The sixth isolate, S76, was resistant to cefoxitin and amoxicillin-clavulanate but negative in the DDST, thus exhibiting a class C β-lactamase phenotype (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of six expanded-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant isolates of serotype Enteriditisa

| Strain | Yr | PT | Antibiotic resistance phenotype | Transferred resistance markers | PFGE pattern | pI | β-Lactamase resistance gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S76 | 1992 | PT4 | ApAmcFoxCazCtxKm | No transfer | A | 9.0 | ampC |

| S78 | 1994 | PT4 | ApCazCtxAtmCmKmSmToSu | ApCazCtxAtmCmKmSmToSu | B1 | 8.2 | blaSHV-12 |

| S79 | 1996 | PT4 | ApCazCtxAtmCmKmSmToSu | ApCazCtxAtmCmKmSmToSu | B2 | 8.2 | blaSHV-12 |

| S86 | 1997 | PT4 | ApCazCtxAtmCm | ApCazCtxAtmCm | B3 | 8.2 | blaSHV-12 |

| S87 | 1997 | RDNC | ApCazCtxAtmCmKmSmToSu | ApCazCtxAtmCmKmSmToSu | B4 | 8.2 | blaSHV-12 |

| S88 | 1997 | PT4 | ApCazCtxAtmCm | ApCazCtxAtmCm | B5 | 8.2 | blaSHV-12 |

Abbreviations: PT, Phage type; Ap, ampicillin; Caz, ceftazidime; Ctx, cefotaxime; Atm, aztreonam; Amc, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; Cm, chloramphenicol; Sm, streptomycin; Km, kanamycin, To, tobramycin; Su, sulfonamides; Fox, cefoxitin; RDNC, react but do not conform.

It was possible to transfer β-lactam resistance from the five DDST-positive isolates to Escherichia coli by conjugation (19), along with all other resistance markers (Table 1).

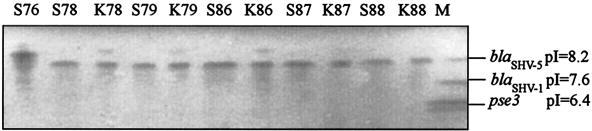

Isoelectric focusing of β-lactamases showed that all isolates, except S76, and their respective ceftazidime-resistant transconjugants produced a β-lactamase that focused at 8.2, suggesting expression of a blaSHV-like gene (Fig. 1). PCR for blaSHV (1) and DNA sequencing showed that these isolates carried blaSHV-12 (EMBL accession no. AY008838). Strain S76 produced a β-lactamase species with a pI of 9.0 and was positive, by ampC PCR assay and DNA sequencing, for a Citrobacter freundii ampC-derived bla gene (95% homologous, EMBL accession no. D85910).

FIG. 1.

Isoelectric focusing of β-lactamases, performed in ampholyte-containing polyacrylamide gels (pH range, 3.5 to 9.5), produced by the broad-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant serotype Enteritidis isolates (S76 to S88) and the respective E. coli transconjugants (K78 to K88). β-Lactamases with known pIs are on the right (lane M).

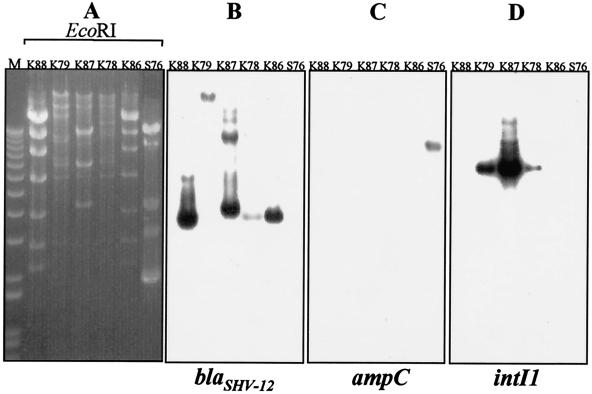

Plasmids purified from the five E. coli transconjugants and the S76 clinical isolate were digested with EcoRI (Fig. 2). E. coli transconjugants K86 and K88 contained indistinguishable plasmids (ca. 50 kb in size), while transconjugants K78, K79, and K87 contained plasmids of ca. 90 kb with different restriction patterns, though they included some common bands (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Restriction patterns of plasmids isolated (Concert Purification Midi kit; Life Technologies, Milan, Italy) from five E. coli transconjugant clones and serotype Enteritidis isolate S76. (A) Plasmid fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gels and transferred onto positively charged nylon membranes (Boehringer-Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Molecular weight markers (1-kb ladder) are in lane M. (B to D) Southern blot hybridization was performed according to standard protocols (19) with blaSHV-12, C. freundii ampC, and intI1 DNA probes, respectively, labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using the RTS RadPrimer DNA labeling kit (Life Technologies). Primers OS5 and OS6 were used to amplify the blaSHV genes and synthesize the blaSHV-12 DNA probe (1). Primers ampCF (5′-TGGGTTCAGGCCAACATGGATGC-3′) and ampCR (5′-TGCCAACATTACGATGCCAAGG-3′) were used to amplify the C. freundii ampC-derived gene probe (EMBL accession no. X91840). The intI1 probe was prepared as previously described (21).

Hybridization with the blaSHV-12 probe demonstrated that this gene was located on the transferred plasmid in each case (Fig. 2B). In spite of two distinct plasmids being present in transconjugant K78 on the one hand and transconjugants K86 and K88 on the other, all three showed an apparently common blaSHV-12-positive band of approximately 4.0 kb. In contrast, the blaSHV-12 probe hybridized to distinct EcoRI fragments of the K79 and K87 plasmids. Southern blot hybridization with a C. freundii ampC-specific probe demonstrated that the cephalosporinase gene was also located on a plasmid (Fig. 2C).

The presence of class 1 integrons was investigated for all six clinical isolates by PCR amplification with the 5′CS and 3′CS primer pair (12). Amplicons of a similar size (2.5 kb) were obtained from S78, S79, and S87 and sequenced. Three resistance genes were included as gene cassettes: aacC4, conferring resistance to kanamycin and tobramycin; aadA1, conferring streptomycin-spectinomycin resistance; and catB2, conferring chloramphenicol resistance. This particular structure does not correspond to any of the variable regions of class 1 integrons described so far. The integrons were located on the blaSHV-12-carrying plasmids, as demonstrated by Southern blot hybridization on plasmid DNA, using an intI1-specific probe (Fig. 2D). The three remaining isolates were negative for the presence of class 1 integrons by both PCR and hybridization with the intI1 probe.

Molecular typing by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of XbaI-restricted genomic DNA (8) showed that all clinical strains carrying the blaSHV-12 gene were highly related at the chromosomal level. Their PFGE patterns differed by three to four DNA fragments, classifying them in five subtypes (data not shown). Nevertheless, isolates S78 and S79 had been identified in Sicily 2 years apart and were epidemiologically unrelated. Isolates S86, S87, and S88, however, had been recovered from patients in three gastroenteritis cases that had occurred in Catanzaro, Calabria, during a very brief interval of time. Given the similarity of their PFGE profiles, these isolates may represent a clonal outbreak, though clinical records did not indicate any epidemiological association. The cephalosporinase-producing S76 isolate exhibited a distinct PFGE type.

The present findings constitute further evidence regarding the increasing frequency of isolation of cephalosporin-resistant strains among epidemiologically important Salmonella serotypes. Most other studies so far have focused on S. enterica serotype Typhimurium strains that had acquired plasmids encoding various ESBL types such as TEM, SHV, CTX-M, and PER (20, 22). Recently, serotype Typhimurium strains producing cephalosporinases similar to the chromosomal enzymes of C. freundii have also been reported in the United States (5, 23). However, β-lactamase-mediated resistance to newer cephalosporins is much more rare in serotypes other than Typhimurium. Class A ESBLs have so far been described for a limited number of Salmonella strains of serotypes Wien, Mbandaka, and antigenic formula 35:c:1,2 in African countries and Senftenberg in India (3, 9, 17, 18). There have also been indications of serotype Enteritidis producing unidentified ESBLs in various countries (2, 4, 7). The present study documents for the first time acquisition of bla genes coding for SHV-12 and a C. freundii-derived class C cephalosporinase by serotype Enteritidis.

In five of the six isolates examined here, resistance was due to the acquisition of plasmids coding for SHV-12. This ESBL resembles SHV-5 and exhibits potent hydrolytic activity against most oxyimino-β-lactams, including ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and ceftriaxone. There were at least two different types of SHV-12-encoding plasmids, as indicated by the differences in plasmid restriction patterns and the results of hybridization experiments. Therefore, acquisition of the blaSHV-12 gene could have occurred on more than one separate occasion.

The possibility that serotype Enteritidis acquired “nosocomial” plasmids warrants investigation. The hypothesis of nosocomial acquisition would be in agreement with previous studies indicating that nontyphoid salmonellae producing TEM or SHV ESBLs may have exchanged bla genes with other enterobacteria frequently encountered in hospitals (21, 22). Besides, SHV-12-encoding plasmids have been previously encountered in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from hospitals throughout Italy (11, 15). A similar hypothesis could also be formulated for isolate S76, which produced a class C β-lactamase, since enterobacterial clinical isolates with plasmid-mediated cephalosporinases have been repeatedly reported in European countries and the United States (16, 23).

Production of newer cephalosporin-hydrolyzing β-lactamases by strains belonging to a predominant phage type of serotype Enteritidis is a disturbing development. Further dissemination of such strains may drastically reduce therapeutic options for severe salmonella infections in children. In addition, salmonella carriage of transmissible plasmids such as those described here may facilitate spread of a variety of resistance determinants to other community-acquired pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ida Luzzi and Emma Filetici for helpful advice and suggestions. We thank F. Riccobono for DNA sequencing.

This research was supported by grants from the Joint Research and Technology Program between Italy and Greece for 1999-2001 from the Greek General Secretariat for Research and Development of the Ministry of Development and the “Progetto Antibiotico Resistenza 2000” from the Italian Ministry of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arlet, G., M. Rouveau, and A. Philippon. 1997. Substitution of alanine for aspartate at position 179 in the SHV-6 extended-spectrum β lactamase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 152:163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blahova, J., M. Lesicka-Hupkova, K. Kralikova, V. Krcmery, T. Krcmeryova, and K. Kubonova. 1998. Further occurrence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Salmonella enteritidis. J. Chemother. 10:291-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardinale, E., P. Colbachini, J. D. Perrier-Gros-Claude, A. Gassama, and A. Aidara-Kane. 2001. Dual emergence in food and humans of a novel multiresistant serotype of Salmonella in Senegal: Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype 35:c:1,2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2373-2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherian, B. P., N. Singh, W. Charles, and P. Prabhakar. 1999. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Salmonella enteritidis in Trinidad and Tobago. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:181-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fey, P., P. Safranek, M. E. Rupp, E. F. Dunne, E. Ribot, P. C. Iwen, P. A. Bradford, F. J. Angulo, and S. H. Hinrichs. 2000. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella infection acquired by a child from cattle. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1242-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher, J. 1997. Salm/Enter-Net records a resurgence in Salmonella Enteritidis infection through the European Union. Eurosurveillance Wkly. 1:26.

- 7.Gaillot, O., C. Clement, M. Simonet, and A. Philippon. 1997. Novel transferable β-lactam resistance with cephalosporinase characteristics in Salmonella enteritidis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:85-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gautom, R. K. 1997. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other gram-negative organisms in 1 day. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2977-2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammami, A., G. Arlet, S. Ben Redjeb, F. Grimont, A. Ben Hassen, A. Rekik, and A. Philippon. 1991. Nosocomial outbreak of acute gastroenteritis in a neonatal intensive care unit in Tunisia caused by multiply drug resistant Salmonella Wien producing SHV-2 β-lactamase. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 10:641-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarlier, V., M. H. Nicolas, G. Fournier, and A. Philippon. 1988. Extended-broad-spectrum β-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer β-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10:867-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laksai, Y., M. Severino. M. Perilli, G. Amicosante, G. Bonfiglio, and S. Stefani. 2000. First identification of an SHV-12 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:349-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levesque, C., L. Pichè, C. Larose, and P. Roy. 1995. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:185-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nastasi, A., C. Mammina, and L. Cannova. 2000. Antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella Enteritidis, Southern Italy, 1990-1998. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:401-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6 (M100-S7). National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 15.Pagani, L., M. Perilli, R. Migliavacca, F. Luzzaro, and G. Amicosante. 2000. Extended-spectrum TEM- and SHV-type beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing outbreaks in intensive care units in Italy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:765-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philippon, A., G. Arlet, and G. A. Jacoby. 2002. Plasmid-determined AmpC-type β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poupart, M. C., C. Chanal, D. Sirot, R. Labia, and J. Sirot. 1991. Identification of CTX-2, a novel cefotaximase from a Salmonella mbandaka isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1498-1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Revathi, G., K. P. Shannon, P. D. Stapleton, B. K. Jain, and G. L. French. 1998. An outbreak of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Salmonella senftenberg in a burns ward. J. Hosp. Infect. 40:295-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 20.Threlfall, E. J., J. A. Frost, L. R. Ward, and B. Rowe. 1996. Increasing spectrum of resistance in multiresistant Salmonella typhimurium. Lancet 347:1053-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tosini, F., P. Visca, I. Luzzi, A. M. Dionisi, C. Pezzella, A. Petrucca, and A. Carattoli. 1998. Class 1 integron-borne multiple-antibiotic resistance carried by IncFI and IncL/M plasmids in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3053-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villa, L., C. Pezzella, F. Tosini, P. Visca, A. Petrucca, and A. Carattoli. 2000. Multiple-antibiotic resistance mediated by structurally related IncL/M plasmids carrying an extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene and a class 1 integron. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2911-2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winokur, P. L., D. L. Vonstein, L. J. Hoffman, E. K. Uhlenhopp, and G. V. Doern. 2001. Evidence for transfer of CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase plasmids between Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals and humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2716-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]