Abstract

Objective

To identify factors influencing the completion of a three-dose course of weekly intramuscular benzathine penicillin G injections by adults and adolescents with syphilis of unknown duration or late syphilis.

Methods

We searched medical literature databases for studies reporting on factors influencing treatment completion by patients with syphilis aged 10 years or older and studies involving health professionals administering syphilis treatment. Studies could use quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods approaches. We conducted a systematic review following the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis method.

Findings

We identified 24 eligible studies, of which 20 (83%) were published in 2010 or later, 19 (79%) focused on pregnant women, seven (29%) were conducted in Brazil, six (25%) in the United States of America and three (12%) in China. Health-care system-related factors influencing the noncompletion of treatment included the limited supply of, and limited access to, medication and inadequate follow-up systems. Other common factors were patients presenting late to antenatal services and social and economic factors, such as transportation barriers and a low educational level.

Conclusion

A comprehensive systems approach is needed to increase the treatment completion rate for syphilis of unknown duration and late syphilis. Health service interventions, such as improving patient management systems, should be supplemented by actions to address social inequalities and shortages in the supply of benzathine penicillin G. Research is needed to understand barriers to treatment completion in high-income countries and among priority groups, including Indigenous people and men who have sex with men.

Résumé

Objectif

Identifier les facteurs influençant l’achèvement d’un traitement de trois doses d’injections intramusculaires hebdomadaires de benzathine benzylpénicilline par des adultes et des adolescents atteints d’une syphilis de durée inconnue ou d’une syphilis tardive.

Méthodes

Nous avons consulté des bases de données de la littérature médicale pour trouver des études portant sur les facteurs influençant l’achèvement du traitement par des patients atteints de syphilis et âgés de 10 ans ou plus, ainsi que des études portant sur des professionnels de la santé administrant un traitement contre la syphilis. Ces études pouvaient utiliser des approches quantitatives, qualitatives ou des méthodes mixtes. Nous avons procédé à un examen systématique en suivant la méthode «Manual for Evidence Synthesis» du Joanna Briggs Institute.

Résultats

Nous avons identifié 24 études éligibles, dont 20 (83%) ont été publiées en 2010 ou par la suite, 19 (79%) portaient sur des femmes enceintes, sept (29%) ont été menées au Brésil, six (25%) aux États-Unis et trois (12%) en Chine. Les facteurs liés au système de soins de santé qui influencent l’inachèvement du traitement comprennent la fourniture limitée de médicaments et l’accès limité à ceux-ci, ainsi que des systèmes de suivi inadéquats. D’autres facteurs courants étaient la présentation tardive des patientes aux services prénatals et les facteurs sociaux et économiques, tels que les obstacles dans l’utilisation des transports et un faible niveau d’éducation.

Conclusion

Une approche systémique globale s’impose pour augmenter le taux d’achèvement du traitement de la syphilis de durée inconnue et de la syphilis tardive. Les interventions des services de santé, telles que l’amélioration des systèmes de prise en charge des patients, doivent s’accompagner d’actions visant à remédier aux inégalités sociales et aux pénuries de benzathine benzylpénicilline. Des recherches sont nécessaires pour comprendre les obstacles à l’achèvement du traitement dans les pays à revenu élevé et parmi les groupes prioritaires, notamment les hommes ayant des relations sexuelles avec d’autres hommes et les populations autochtones.

Resumen

Objetivo

Identificar los factores que influyen en la finalización de un tratamiento de tres dosis semanales de penicilina G benzatina por vía intramuscular en personas adultas y adolescentes con sífilis de duración desconocida o sífilis tardía.

Métodos

Se realizó una búsqueda en bases de datos de literatura médica de estudios que informaran sobre factores que influyen en la finalización del tratamiento en pacientes con sífilis de 10 años o más, así como en estudios que incluyeran a profesionales sanitarios encargados de administrar el tratamiento para la sífilis. Se incluyeron estudios con enfoques cuantitativos, cualitativos o de métodos mixtos. Se llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática siguiendo la metodología del JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis.

Resultados

Se identificaron 24 estudios que cumplían los criterios de inclusión, de los cuales 20 (83%) fueron publicados en 2010 o posteriormente, 19 (79%) se centraron en mujeres embarazadas, siete (29%) se realizaron en Brasil, seis (25%) en Estados Unidos de América y tres (12%) en China. Entre los factores relacionados con el sistema sanitario que influyeron en la no finalización del tratamiento se encontraron el suministro limitado y el acceso restringido a la medicación, así como sistemas de seguimiento inadecuados. Otros factores frecuentes fueron la asistencia tardía de las pacientes a los servicios prenatales y diversos determinantes sociales y económicos, como las barreras de transporte y el bajo nivel educativo.

Conclusión

Es necesario adoptar un enfoque sistémico integral para aumentar la tasa de finalización del tratamiento de la sífilis de duración desconocida y la sífilis tardía. Las intervenciones en los servicios sanitarios, como la mejora de los sistemas de gestión de pacientes, deben complementarse con medidas orientadas a reducir las desigualdades sociales y a paliar la escasez de penicilina G benzatina. Se requiere investigación adicional para comprender las barreras a la finalización del tratamiento en países de ingresos altos y en grupos prioritarios, como los hombres que tienen relaciones sexuales con hombres y las poblaciones indígenas.

ملخص

الغرض تحديد العوامل المؤثرة على إكمال البالغين والمراهقين المصابين بمرض الزهري غير معروف المدة أو الزهري المتأخر، لدورة علاجية أسبوعية ثلاثية الجرعات من حقن البنزاثين بنسلين ج العضلية.

الطريقة قمنا بالبحث في قواعد بيانات المنشورات الطبية عن الدراسات التي تتناول العوامل المؤثرة على إكمال علاج مرضى الزهري الذين تبلغ أعمارهم 10 سنوات فأكثر، والدراسات التي تشمل أخصائيين صحيين يقدمون علاجًا للزهري. يمكن للدراسات استخدام أساليب كمية أو نوعية أو طرق مختلطة. قم بإجراء مراجعة منهجية وفقًا لدليل JBI لطرق تجميع الأدلة.

النتائج قمنا بتحديد 24 دراسة مؤهلة، نُشرت منها 20 دراسة (%83) في عام 2010 أو لاحقًا، وركزت 19 دراسة (%79) على السيدات الحوامل، وأُجريت سبع دراسات (%29) في البرازيل، وست دراسات (%25) في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية، وثلاث دراسات (%12) في الصين. تشمل العوامل المرتبطة بنظام الرعاية الصحية والتي تؤثر على عدم إكمال العلاج: الإمدادات المحدودة للأدوية، والحصول المحدود عليها، وعدم كفاية أنظمة المتابعة. ومن العوامل الشائعة الأخرى: تأخر المرضى في السعي لخدمات ما قبل الولادة، والعوامل الاجتماعية والاقتصادية، مثل صعوبة الانتقالات، وانخفاض المستوى التعليمي.

الاستنتاج هناك حاجة إلى أسلوب شامل للأنظمة لزيادة معدل إكمال العلاج لمرض الزهري غير معروف المدة، والزهري المتأخر. يجب استكمال تدخلات الخدمات الصحية، مثل تحسين أنظمة إدارة المرضى، بإجراءات لمعالجة أوجه عدم المساواة الاجتماعية، ونقص إمدادات البنزاثين بنسلين ج. هناك حاجة إلى إجراء أبحاث لفهم عوائق إكمال العلاج في الدول ذات الدخل المرتفع وبين الفئات ذات الأولوية، بما في ذلك الرجال الذين يمارسون الجنس مع الرجال والسكان الأصليين.

摘要

目的

为了确定影响病情持续时间不明的或晚期成人和青少年梅毒患者的苄星青霉素 G 肌肉注射疗程(共三剂次,每周注射一次)完成率的因素。

方法

我们检索了医学文献数据库,以查找报告了 10 岁及以上梅毒患者治疗完成率影响因素的研究以及涉及卫生专业人员实施梅毒治疗的研究。研究可以采用定量方法、定性方法或者混合方法。

结果

我们根据《JBI 证据综合手册》(JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis) 中的方法进行了系统评价。我们确定了 24 项符合条件的研究,其中 20 项(占 83%)发布于 2010 年或之后,19 项(占 79%)以孕妇为研究对象,7 项(占 29%)在巴西开展,6 项(占 25%)在美国开展,3 项(占 12%)在中国开展。与卫生保健系统有关的治疗未完成率影响因素包括药物补给受限、药物获取渠道受限以及追踪系统不完善。其他常见因素包括患者接受产检服务的时间较晚以及交通障碍和教育水平低下等社会经济因素。

结论

必须采用全面的系统做法以提高病情持续时间不明的或晚期梅毒患者的治疗完成率。在实施医疗服务干预措施(例如改善患者管理系统)的同时必须采取相应行动以解决社会不平等和苄星青霉素 G 供应不足的问题。必须开展相关研究以了解影响高收入国家优先人群(包括男男性接触者和土著人民)的治疗完成率的障碍。

Резюме

Цель

Выявление факторов, которые влияют на завершение курса из трех еженедельных внутримышечных инъекций бензатина пенициллина G взрослыми и подростками, страдающими от сифилиса неизвестной давности или запущенной формы данного заболевания.

Методы

Авторы провели поиск исследований в базах данных медицинской литературы, в которых сообщалось о факторах, влияющих на завершение курса лечения у пациентов с сифилисом длительностью 10 лет или более. Проводился также поиск исследований с участием врачей, проводящих лечение от сифилиса. В этих исследованиях могли использоваться количественные, качественные или смешанные методологические подходы. Авторы выполнили систематический обзор, следуя руководству JBI по синтезу доказательных данных.

Результаты

Было обнаружено 24 исследования, удовлетворяющие условиям. Из них 20 (83 %) были опубликованы в 2010 году или позже, 19 работ (79 %) были посвящены беременным женщинам, семь (29 %) были проведены в Бразилии, шесть (25 %) – в Соединенных Штатах Америки, три (12 %) – в Китае. Факторы, связанные с системой здравоохранения и препятствующие завершению курса лечения, включали ограниченность поставок и доступа к лекарствам, а также недостаточно эффективные системы последующего контроля. К другим распространенным факторам относились позднее обращение пациенток в службы дородового ухода и социально-экономические факторы, такие как проблемы с транспортной доступностью и низкий уровень образования.

Вывод

Необходим всеобъемлющий системный подход для того, чтобы повысить уровень завершенности лечения сифилиса неизвестной давности или запущенной формы сифилиса. Вмешательства в сфере здравоохранения, такие как улучшение систем ведения пациентов, следует подкреплять действиями, направленными на уменьшение социального неравенства и нехватки безантина пенициллина G. Требуются исследования, которые помогли бы определить факторы, препятствующие завершению курса лечения в странах с высоким уровнем дохода и среди приоритетных групп населения, включая мужчин, практикующих секс с мужчинами, и представителей коренных народов.

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 49.7 million people were living with syphilis in 2019. Of the 209 253 cases reported in the United States of America in 2023, 98 791 (47.2%) were syphilis of unknown duration or late syphilis.1 Here, late syphilis is defined as late-stage (i.e. tertiary) syphilis or late latent syphilis, where at least 2 years have passed since infection. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) set a target for the reduction in the number of new syphilis cases globally from 7.1 million in 2020 to 0.71 million in 2030.2 To achieve this target, a key strategic priority is to monitor the cascade of care to ensure that timely treatment is provided with a minimal loss to follow-up.2 For most cases, WHO guidelines for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis) recommend treating adults and adolescents with primary, secondary and early latent (asymptomatic) syphilis of less than 2 years’ duration by administering a single intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin G (i.e. 2.4 million units). For syphilis of unknown duration and late syphilis, by contrast, a regimen of three intramuscular injections delivered at weekly intervals (i.e. 7.2 million units in total) is generally recommended.3 However, limited data are available on the use of specific regimens or on the duration of treatment for syphilis of unknown duration and late syphilis.3 Theoretically, longer treatment is required for late syphilis as the causative bacteria divide more slowly at that stage.4 For syphilis of unknown duration, longer administration ensures that treatment is adequate regardless of when the infection was acquired. Furthermore, serological cure rates for syphilis of unknown duration and late syphilis with one dose of benzathine penicillin G are reported to be low, ranging from 33% to 39%.3

There are wide variations in the proportion of people with syphilis of unknown duration or late syphilis who receive all three doses of benzathine penicillin G as prescribed. The proportion reported varies from 93.5% in a Thai antenatal clinic study and 86% in a Bolivian antenatal clinic study to 61–65% in South African antenatal clinic studies;5–8 54% in a Peruvian study of transgender women and men who have sex with men; and 43% in the general population in one county in the United States.9,10 Noncompletion of the three-dose regimen increases the risk of serious sequelae, including complications that affect the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular and central nervous systems.11 In pregnant women with syphilis, incomplete treatment may result in stillbirth, miscarriage, birth defects, preterm birth or neonatal death.11,12

The reasons people start but do not complete syphilis treatment are not clear. A review showed that factors that influenced whether pregnant women and their partners completed syphilis treatment regimens included: (i) the level of engagement with antenatal care; (ii) proximity to a clinic; (iii) knowledge about, and attitudes to, sexually transmissible infections; (iv) perceptions of pain associated with treatment; (v) medication availability; and (vi) clinical protocols and practices.13 However, information is also needed on factors that influence treatment pathways in priority groups with a higher prevalence of syphilis, such as Indigenous populations and men who have sex with men.14,15

The previous search identified only one systematic review of factors associated with the completeness of, and adherence to, benzathine penicillin G injections in a broad population group.16 That review examined treatment for rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease and found that adherence to treatment pathways was affected by: (i) disease severity; (ii) the quality of patient–staff interactions; (iii) the health worker’s cultural competence; (iv) patients’ perceptions of the pain associated with, and the efficacy of, treatment; and (v) the accessibility of treatment services, such as the provision of home-based care. However, the review’s findings may not be relevant for the treatment of syphilis of unknown duration and late syphilis because it is recommended that benzathine penicillin G is administered every three to four weeks for several years for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, with the duration determined by a range of sociodemographic and clinical factors.17

The aim of our review was to identify factors that influence the completion of a three-dose course of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G injections for syphilis by adults and adolescents to improve the health-care services and interventions involved in the syphilis care cascade.

Methods

We followed the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis method for systematic reviews and the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.18,19 The protocol is registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42023406247).20 Our review included studies that reported data on factors influencing the completion of a regimen of three intramuscular, 2.4 million-unit doses of benzathine penicillin G delivered at weekly intervals. Studies involving patients with syphilis aged 10 years or older, and studies involving health workers administering syphilis treatment were eligible. We considered all quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method studies conducted since 1944, the year when penicillin use for late-stage syphilis was first documented.21 Studies that investigated only factors related to the commencement of benzathine penicillin G treatment were not eligible for inclusion. In addition, opinion pieces, commentaries, protocols, conference abstracts, systematic reviews and literature reviews were excluded. There were no geographical or language limitations.

We initially searched Medline® and CINAHL databases to identify relevant articles to inform the search strategy. Then, we developed search strategies, with the assistance of a research librarian, for the Medline®, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, CINAHL and Google Scholar databases (Box 1). Searches were conducted on 28 and 29 March 2023 and updated on 21 February 2024 and again on 30 January 2025. We assessed the first 200 results on Google Scholar, as previously recommended.22 We imported all records identified into EndNote 20 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, United States) and removed duplicates using the Bramer method.23 The grey literature and reference lists of the studies included were not searched.

Box 1. Search strategies, systematic review of factors influencing treatment completion for late syphilis, worldwide, 1989–2025.

Medline

syphili*.mp. or exp syphilis/

pallidum.mp.

1 or 2

treatment.mp. or exp therapeutics/

penicillin.mp. or exp penicillins/

exp anti-bacterial agents/ad, dt [administration & dosage, drug therapy]

exp penicillin g benzathine/ or benzathine.mp.

regimen*.mp.

treatment*.mp.

4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

exp patient compliance/ or exp “treatment adherence and compliance”/

exp treatment refusal/

((treat* or therap* or medicat* or antibiotic* or penicillin or benzathine) adj10 (commenc* or adher* or “non-adher*” or nonadher* or complian* or “non-complian*” or noncomplian* or complet* or “non-complet*” or noncomplet* or refus* or “follow-up” or incomplete or adequat* or inadequat*)).mp.

cascade.mp.

11 or 12 or 13 or 14

3 and 10 and 15

limit 16 to yr = ”1944 -current”

Embase

syphili*.mp. or exp syphilis/

pallidum.mp.

1 or 2

penicillin.mp. or exp penicillin derivative/

exp benzathine/ or benzathine.mp. or exp benzathine penicillin/

treatment.mp.

regimen*.mp. or exp drug dose regimen/ or exp drug therapy/

4 or 5 or 6 or 7

((treat* or therap* or medicat* or antibiotic* or penicillin or benzathine) adj10 (commenc* or adher* or “non-adher*” or nonadher* or complian* or “non-complian*” or noncomplian* or complet* or “non-complet*” or noncomplet* or refus* or “follow-up” or incomplete or adequat* or inadequat*)).mp.

cascade.mp.

exp treatment refusal/

exp patient compliance/

9 or 10 or 11 or 12

3 and 8 and 13

limit 14 to yr = ”1944 -current”

Web of Science Core Collection

syphili*

pallidum

1 or 2

treatment

penicillin*

benzathine

regimen*

4 or 5 or 6 or 7

((treat* or therap* or medicat* or antibiotic* or penicillin or benzathine) and (commenc* or adher* or “non-adher*” or nonadher* or complian* or “non-complian*” or noncomplian* or complet* or “non-complet*” or noncomplet* or refus* or “follow-up” or incomplete or adequat* or inadequat*))

3 and 8 and 9

limit 10 to yr = ”1944 -current”

CINAHL

syphili* or mh syphilis

pallidum

1 or 2

treatment

mh penicillins

benzathine

regimen*

4 or 5 or 6 or 7

mh patient compliance or mh treatment withdrawal or mh treatment refusal

((treat* or therap* or medicat* or antibiotic* or penicillin or benzathine) and (commenc* or adher* or “non-adher*” or nonadher* or complian* or “non-complian*” or noncomplian* or complet* or “non-complet*” or noncomplet* or refus* or “follow-up” or incomplete or adequat* or inadequat*))

cascade

9 or 10 or 11

3 and 8 and 12

limit 13 to yr = ”1944 -current”

Google Scholar

Search 1: penicillin syphilis adherence (Limits: title only and limit yr = ”1944 -current”)

Search 2: penicillin syphilis treatment (Limits: title only and limit yr = ”1944 -current”)

Notes: In Medline and Embase searches, mp. indicates multipurpose (e.g. title, abstract and keywords). In CINAHL searches, mh indicates both major and minor headings.

We imported study details into the Rayyan review management tool (Rayyan, Cambridge, United States).24 Non-English language studies were translated using Google Translate (Google Inc., Mountain View, United States) or through an accredited translation company. At least two members of a team of four reviewers screened study titles and abstracts against eligibility criteria, followed by full-text assessment of studies marked for possible inclusion. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus following discussion; if a consensus could not be reached, a third team member made the final decision. Reasons for exclusion were recorded.

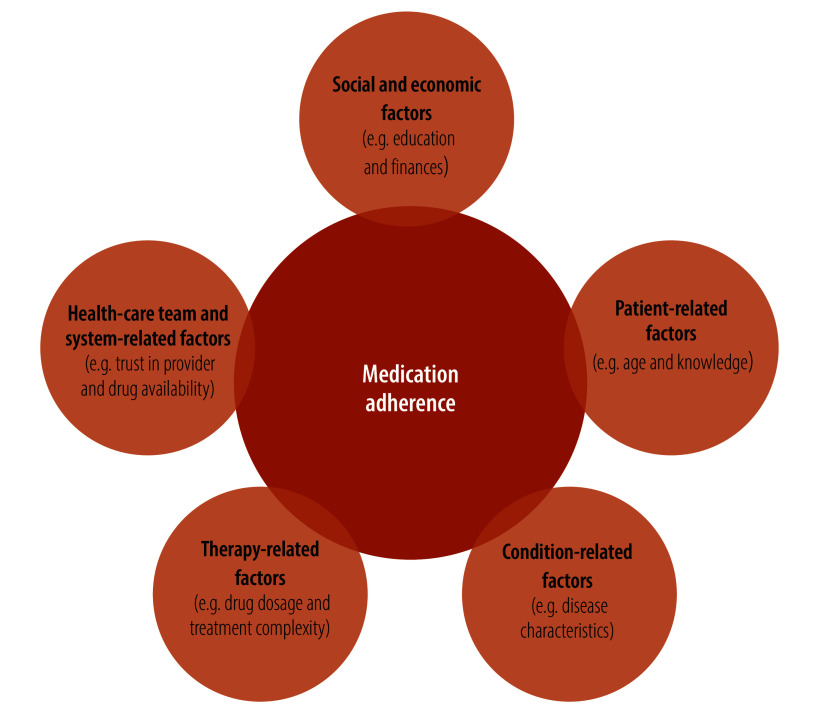

We classified factors influencing treatment completion using WHO’s five dimensions of medication adherence,25 a widely used framework for characterizing adherence factors (Fig. 1).26

Fig. 1.

Dimensions of medication adherence, systematic review of factors influencing treatment completion for late syphilis, worldwide, 1989–2025

Note: The five dimensions of medication adherence are described in the World Health Organization’s publication Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action.25

We also appraised all studies included in the systematic review for study quality using a checklist based on the Meta Quality Appraisal Tool (MetaQAT),27 which was developed to evaluate public health research across a variety of study designs. The tool assesses study quality using nine criteria in four domains: (i) relevancy (one criterion); (ii) reliability (three criteria); (iii) validity (four criteria); and (iv) applicability (one criterion).27 An overall judgment is produced for each criterion and domain. MetaQAT scores range from 0 to 18, with a high score indicating high quality: a score of 0 to 9 was classified as low quality, a score of 10 to 14 as medium quality and a score of 15 to 18 as high quality. For our review, this appraisal process demonstrated the relevance and appropriateness of the studies included for public health policy and practice.

One author extracted following data from the included studies into Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft, Redmond, United States): (i) author or authors; (ii) year of publication or writing; (iii) publication journal; (iv) study design; (v) methodology (quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods); (vi) methods; (vii) number of participants; (viii) participants’ characteristics; (ix) country in which the study was conducted; (x) health-care setting; (xi) study aim; and (xii) the type of factor reported to influence the completion of benzathine penicillin G treatment (i.e. condition-related factors, therapy-related factors, health-care system-related factors, patient-related factors, and social and economic factors). A second author crosschecked the extracted data and any disagreements were resolved by consensus. As our research question concerned the identification of factors influencing treatment completion rather than the measurement of effects, no meta-analysis was conducted.

Results

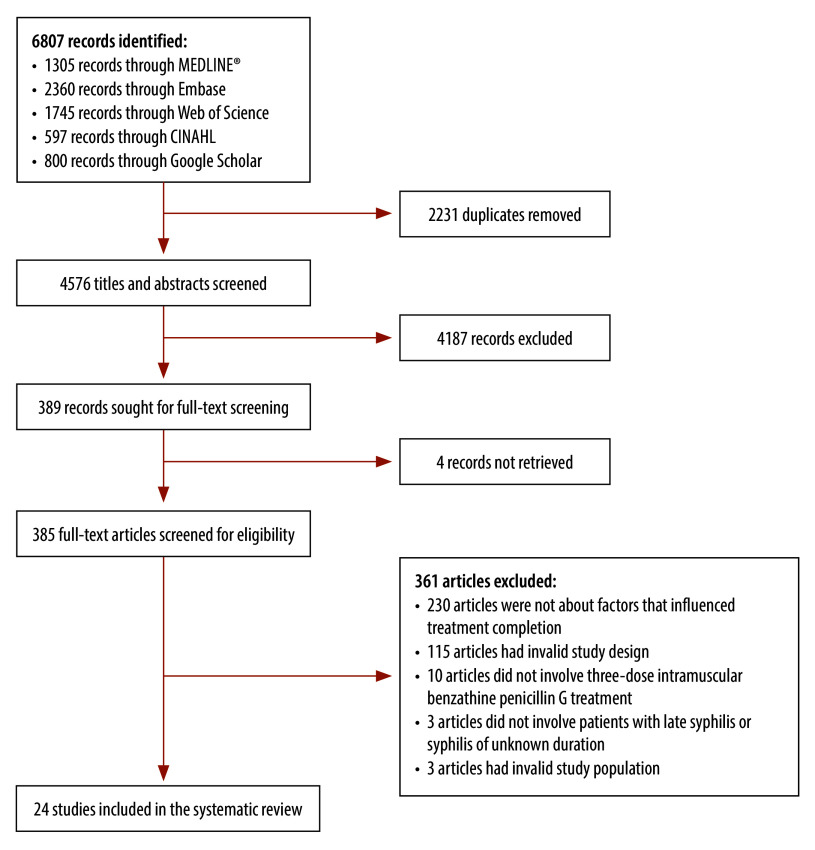

We screened the titles and abstracts of 4576 studies, of which 389 were selected for full-text screening and 24 met the eligibility criteria (Fig. 2).5–7,9,10,28–46 The MetaQAT scores for these studies ranged from 9 to 17; 11 studies were categorized as high quality, 12 as medium quality and one as low quality. The MetaQAT appraisal revealed that many studies had treatment completion as a secondary or ancillary aim, which meant that these studies’ relevance to the aims of our review was not always clear. However, all 24 studies were relevant to public health policy and practice, and provided clear recommendations on the management and treatment of syphilis in primary care. As adequate treatment was not the primary focus of most studies, its definition varied. In addition, because a large proportion of studies examined treatment completion by pregnant women, incomplete treatment was frequently defined as treatment that was initiated less than 30 days before delivery.10,28–35 Several studies did not clearly describe what they defined as adequate treatment,36–38 with one study extending the definition of adequate treatment to include the partners of pregnant women.35 Most studies did not quantify the proportion of participants at each disease stage.5–7,9,29–31,33,34,36–40 Consequently, lack of clarity about the definition of adequate treatment, and about whether adequate treatment was the administration of one or three benzathine penicillin G doses, made it difficult to determine if the influencing factors reported in the studies related to completion of the three-dose treatment regimen or to another aspect of treatment, such as treatment uptake or, for pregnant women, treatment before delivery.

Fig. 2.

Study selection flowchart, systematic review of factors influencing treatment completion for late syphilis, worldwide, 1989–2025

Table 1 (available at https://www.who.int/publications/journals/bulletin/) summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies. Most were published in 2010 or later (83%; 20)6,9,10,28,30–32,34–46 and were conducted in Brazil (29%; 7)30,34,35,37,38,40,41 or United States (25%; 6).10,31,42,44–46 The majority included only pregnant women (79%; 19/24).5–7,28–37,39,41–44,46 Of the 24 studies, two (8%) looked at treatment completion among gender- or sexually diverse people, specifically transgender women and men who have sex with men,9,40 and three (13%) investigated people with syphilis in the general population.10,38,45 Few studies collected data through surveys, interviews or focus groups (25%; 6);29,33,36–38,40 instead, most studies (71%; 17) involved the quantitative analysis of cross-sectional data from reviews of medical records or syphilis registers.7,9,10,28,29,31–36,41–46

Table 1. Study characteristics, systematic review of factors influencing treatment completion for late syphilis, worldwide, 1989–2025.

| Study authors and year of publication | Study aim | Study country | Study setting | Study type and methods | Data source and study participants | Stage of syphilis | Adequacy of treatment | Analysis of factors affecting treatment completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaosavasdi et al. 19895 | To determine the effectiveness of the three-dose benzathine penicillin G regimen for the treatment of syphilis in pregnancy | Thailand | Tertiary care | Quantitative: matched cohort study | Antenatal records of 197 pregnant women with syphilis | ND | 3.6% (7/197) of pregnant women received inadequate treatment of only one or two benzathine penicillin G injections | Descriptive analysis |

| Rutgers 199333 | To assess the quality of antenatal care regarding the detection and management of syphilis | Zimbabwe | Primary and tertiary care | Mixed methods: cross-sectional register review and interviews | Antenatal records of 1433 pregnant women | ND | ND | Descriptive analysis of qualitative findings |

| Beksinka et al. 200229 | To evaluate the process of providing routine syphilis screening for antenatal care clients | South Africa | Primary and tertiary care | Qualitative: interviews, focus groups, observations and inventory and client flow analysis | Key informant interviews with: (i) 9 policy-makers and clinic staff; (ii) 112 antenatal clinic clients (i.e. pregnant women); (iii) 22 postnatal clinic clients (i.e. postpartum women); and (iv) 16 antenatal clinic clients focus groups | ND | ND | Descriptive analysis of qualitative findings |

| Mullick et al. 20057 | To establish the degree of compliance with treatment for syphilis by pregnant women | South Africa | Tertiary care | Quantitative: cross-sectional medical record review | Antenatal records of 18 128 pregnant women with syphilis, of whom 188 tested positive for syphilis | ND | 64.8% (122/188) of pregnant women received all three benzathine penicillin G doses, 5.8% (11/188) received two doses, 13.2% (23/188) received one dose and 15.9% (30/188) received nonea | Frequency analysis |

| Campos et al. 201030 | To identify reasons for inadequate treatment of pregnant women | Brazil | Tertiary care | Quantitative: cross-sectional survey and medical record review | Medical records and questionnaires involving 58 pregnant women with syphilis | ND | 94.8% (55/58) of pregnant women received inadequate treatment | Frequency analysis |

| Zhu et al. 201039 | To assess trends and determinants of maternal and congenital syphilis in Shanghai | China | Primary and tertiary care | Quantitative: prospective cohort | Database records of 1471 pregnant women with syphilis | ND | 26.6% (392/1471) received incomplete treatment | Frequency analysis |

| Diaz Olavarrieta et al. 20116 | To assess the feasibility and acceptability of a patient-led syphilis partner notification strategy among pregnant women with syphilis and their male partners and to assess treatment completion | Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | Tertiary care | Quantitative: cross-sectional survey | Self-administered surveys by 144 pregnant women and 137 male partners | Due to the nature of the study and the test used (immuno-chromato-graphic strip), the stage could not be determined | 86.1% (124/144) received three benzathine penicillin G doses, 11.8% (17/144) had incomplete treatment (i.e. one or two doses) and 2.1% (3/144) received treatment elsewhere | Descriptive and bivariate analysis |

| Tang et al. 20159 | To assess if men who have sex with men and transgender women who screen positive for syphilis are receiving appropriate care and treatment | Peru | Multi-city database | Quantitative: cross-sectional register and medical record review | Database records of 314 men who have sex with men and transgender women with syphilis, of whom 63 were prescribed three weekly doses of benzathine penicillin G | ND | 46.0% (29/63) did not receive all three benzathine penicillin G doses | Frequency and regression analysis |

| Rodrigues et al. 201638 | To analyse the practice of nurses in primary health care monitoring syphilis | Brazil | Primary care | Qualitative: interviews | Interviews with 18 nurses | ND | ND | None |

| Nunes et al. 201737 | To identify difficulties found by professionals affecting the adherence to syphilis treatment by pregnant women and their partners | Brazil | Antenatal clinic (undefined) | Qualitative: interviews | Interviews with 4 nurses | ND | ND | ND |

| Santos et al. 201741 | To assess the knowledge and compliance of health professionals regarding diagnostic and treatment practices for syphilis in patients admitted for childbirth to public maternity hospitals | Brazil | Tertiary care | Quantitative: cross-sectional survey | Questionnaire with 159 obstetricians and maternity nurses | Not determined as the study investigated obstetricians’ and nurses’ knowledge | ND | Frequency analysis |

| Kidd et al. 201831 | To estimate the proportion of potential congenital syphilis cases averted with current prevention efforts and to develop a classification framework to better describe why reported cases were not averted | United States | Nationwide database | Quantitative: cross-sectional register review | Database records of 2508 pregnant women with syphilis | ND | 76.9% (1928/2508) of pregnant women received adequate treatment and 7.6% (48/628) of mothers of reported congenital syphilis cases received adequate treatment | Frequency analysis |

| Zhang et al. 201843 | To describe the epidemiological characteristics of pregnant women with syphilis and to investigate the determinants of adverse pregnancy outcomes | China | City database | Quantitative: cross-sectional register review | Database records of 807 pregnant women with syphilis | Latent (89.3%; 721/807), primary (2.7%; 22/807), secondary (0.6%; 5/807), tertiary (0.2%; 2/807) and unknown duration (7.1%; 57/807) | 40.5% (327/807) were inadequately treated | Frequency and regression analysis |

| Rahman et al. 201942 | To assess the impact of congenital syphilis case review boards on preventing future cases by examining case reviews, identifying preventable factors and evaluating changes in provider practices | United States | Congenital syphilis case review boards | Mixed methods: analysis of case review board records | Congenital syphilis case review board records of 79 congenital syphilis cases | Primary (3.8%; 3/79), secondary (15.2%; 12/79), early latent (36.7%; 29/79), high-titre late latent (17.7%; 14/79) and low-titre late latent (26.6%; 21/79) | ND | Frequency analysis |

| Anugulruengkitt et al. 202028 | To determine the rate of congenital syphilis and to identify gaps in prevention | Thailand | Tertiary care | Quantitative: cross-sectional medical record review | Medical records of 69 pregnant women and their 30 infants | Primary (0%; 0/69 of women), secondary (2.9%; 2/69), early latent (7.2%; 5/69), late latent or unknown duration (88.4%; 61/69) and neurosyphilis (1.5%; 1/69) | 40.6% (28/69) of pregnant women received inadequate treatment | None |

| de Oliviera et al. 202035 | To analyse processes that trigger the vertical transmission of syphilis by reviewing gestational and congenital syphilis notifications | Brazil | City database | Quantitative: cross-sectional register review | Database records of 129 pregnant women with confirmed vertical syphilis transmission | Primary syphilis (51.2%; 66/129); other stages not determined | 76.7% (99/129) of pregnant women received inadequate treatment | Factors were described in the discussion |

| Swayze et al. 202234 | To identify parameters associated with the mother-to-child transmission of syphilis by pregnant women | Brazil | Tertiary care | Quantitative: cross-sectional register review | Hospital records of 1541 pregnant women with syphilis | ND | 60.6% (934/1541) of pregnant women received inadequate treatment, of whom 84.8% (792/934) were not treated while pregnant or had treatment initiated within 30 days of delivery because of a late diagnosis, 13.7% (128/934) were treated but titres did not decline or increased after treatment and no treatment was recorded for the remainder | Frequency and regression analysis |

| Delvaux et al. 202336 | To describe the challenges and outcomes of implementing a national syphilis follow-up system to improve syphilis management in maternal and child health services | Cambodia | Public health facilities | Mixed methods: register review, interviews and focus groups | Database records of 470 pregnant women (of whom 315 tested positive for syphilis), interviews with 16 pregnant women and focus groups with 37 health workers | ND | 27.9% (88/315) of women were treated adequately with benzathine penicillin G, 50.1% (158/315) were treated with other drugs (i.e. erythromycin or cefixime), and 21.9% (69/315) received no or unknown treatment | Thematic content analysis |

| Liu et al. 202332 | To identify correlates of receiving no treatment or inadequate treatment among pregnant women with syphilis | China | Nationwide database | Quantitative: cross-sectional register review | Database records of 1248 pregnant women with syphilis | Latent (80.9%; 1 010/1248), primary, secondary or tertiary (6.0%; 75/1248) and unknown duration (13.1%; 163/1248) | 30.4% (379/1248) of women received no treatment or inadequate treatment, including 29.9% (302/1010) with latent syphilis, 23.7% (18/76) with primary, secondary or tertiary syphilis and 36.2% (59/163) with syphilis of unknown duration | Frequency and regression analysis |

| Mangone et al. 202310 | To quantify treatment for people diagnosed with late latent and unknown duration syphilis | United States | County database | Quantitative: cross-sectional register review | Database records of 14 924 people with syphilis | Late latent or unknown duration (36.0%; 5 372/14 924) | 42.9% (2 302/5372) of people with late latent syphilis or syphilis of unknown duration received three benzathine penicillin G doses | Frequency analysis |

| McDonald et al. 202344 | To identify and classify missed opportunities to prevent congenital syphilis | United States | Nationwide database | Quantitative: cross-sectional register review | Database records of 3761 congenital syphilis cases | All primary and secondary combined | 39.7% (1 494/3761) of birth parents received inadequate treatment | Frequency analysis |

| Carreira et al. 202440 | To identify factors associated with treatment noncompletion among transgender women and transvestites | Brazil | Community | Quantitative: cross-sectional survey | Structured interviews with 1317 transgender women of whom 211 tested positive for syphilis | ND | 38.9% (82/211) of transgender women did not start or complete treatment | Frequency analysis |

| Clarkson-During et al. 202445 | To examine demographic and clinical factors that may contribute to treatment noncompletion | United States | Tertiary care | Quantitative: medical record review | Medical record review of 171 syphilis patients | Primary (5.3%; 9/171), secondary (7.0%; 12/171), tertiary (6.4%; 11/171), early latent (5.3%; 9/171), and late or unknown (76.0%; 130/171) | 48% (82/171) of patients did not complete treatment | Frequency analysis |

| Tannis et al. 202446 | To describe the characteristics associated with the lack of complete syphilis treatment during pregnancy | United States | Multi- jurisdictional database | Quantitative: medical record review | Surveillance data on syphilis in 1476 pregnant women from six United States’ jurisdictions | Primary, secondary or early latent (40.8%; 602/1476), late latent or unknown duration (57.6%; 850/1476), and other (1.6%; 24/1476) | 19.8% (173/874) of people recommended three benzathine penicillin G doses were inadequately treated | Frequency and regression analysis |

ND: not determined.

a Details of the number of injections were missing for two records.

Fourteen studies (58%) reported the proportion of pregnant or postpartum women who commenced and completed syphilis treatment at least 30 days before delivery (Table 1). In these studies, the proportion of women who had no, inadequate or unknown treatment ranged from 4% to 88%. In 10 studies (42%), the proportion ranged from 41% to 88%.6,28,30,32,34–36,43,44,46 Because many of these studies involved women who had given birth to babies with congenital syphilis, the proportion who completed treatment was expected to be low. Of the five studies that did not investigate syphilis in pregnant women, two reported a treatment completion rate for the three-dose, benzathine penicillin G regimen. One study assessed treatment completion by people in the general population who had been diagnosed with late latent syphilis or syphilis of unknown duration, and found that only 43% ( 2302/5372) had received all three doses.10 Similarly, another study which investigated treatment completion by transgender women and men who have sex with men in Peru, found that 54% (34/63) received all three doses in the appropriate timeframe.9

Table 2 shows that the factors most often cited as influencing noncompletion of the three-dose, intramuscular, benzathine penicillin G treatment regimen were health-care system-related factors, patient-related factors, and social and economic factors. For the health-care system, frequently cited factors included: (i) the limited supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G;10,29,34–37,41 and (ii) an inadequate follow-up system for patients.28,29,36,38 One study highlighted the inadequate syphilis treatment women may receive during pregnancy when they attend several health-care services and when the transition between different health workers is not smooth.34 One study described how the availability of specialist health services for gender- and sexually diverse people could explain why transgender women were more likely to commence and complete treatment in one location compared to places without these services.40 The limited supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G was attributed to: (i) problems with national procurement processes;36 (ii) the health service’s inability to appropriately store the medication;10 and global supply shortages in 2014 and 2019 to 2020.29,36 The most common patient-related factor influencing treatment noncompletion was late presentation to antenatal services.7,31,32,36,44,46 One study reported that nearly half of patients who had inadequate treatment were diagnosed with syphilis only at delivery.34 Social and economic factors included: (i) barriers to transportation and the distance from health services;10,36,42 (ii) the lack of private health insurance;45 (iii) cultural or ethnic identity;44 (iv) residency status (e.g. migrants);32,43 (v) homelessness;46 (vi) substance use;38,46 (vii) a history of incarceration;46 and (viii) a low educational level.34,39

Table 2. Factors reported to influence treatment completion, by study, systematic review of factors influencing treatment completion for late syphilis, worldwide, 1989–2025.

| Study authors and year of publication | Factors influencing completion of benzathine penicillin G treatment for late syphilis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition-related factors | Therapy-related factors | Health-care team and system-related factors | Patient-related factors | Social and economic factors | |

| Phaosavasdi et al. 19895 | NA | NA | Being required to undergo spinal puncture and staging of syphilis before treatment | NA | NA |

| Rutgers 199333 | NA | NA | Relationship between nurses and community enabler of treatment completion | NA | NA |

| Beksinka et al. 200229 | NA | NA | (i) Inadequate supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G; (ii) limited information provided to the patient on the importance of treatment compliance; (iii) inadequate follow-up system; and (iv) delays in pregnant women receiving syphilis test results, resulting in an inability to complete treatment before delivery | NA | NA |

| Mullick et al. 20057 | NA | NA | NA | Late presentation to antenatal services | NA |

| Campos et al. 201030 | NA | NA | Medical records incomplete or inaccessible during pregnancy | NA | NA |

| Zhu et al. 201039 | Abnormal reproductive history (not defined) | NA | NA | NA | Educational level of patient and partner |

| Diaz Olavarrieta et al. 20116 | NA | NA | NA | (i) Lack of time; and (ii) not notifying partners about diagnosis | NA |

| Tang et al. 20159 | NA | NA | NA | Patients who identified as transgender were more likely to be lost to follow-up | NA |

| Rodrigues et al. 201638 | NA | Lack of flexibility in treatment dosing | Inadequate follow-up systems due to lack of time and competing priorities | Lack of understanding of the need to return for further treatment (i.e. belief that one dose was adequate) | Substance use |

| Nunes et al. 201737 | NA | NA | (i) Inadequate supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G; and (ii) absence of syphilis treatment protocols | NA | NA |

| Santos et al. 201741 | NA | NA | (i) Inadequate supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G; and (ii) lack of knowledge of correct treatment regimen among health professionals (may be linked to staff turnover) | NA | NA |

| Kidd et al. 201831 | NA | NA | NA | Late presentation to antenatal services | NA |

| Zhang et al. 201843 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Barriers associated with being a migrant woman |

| Rahman et al. 201942 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Transportation barriers |

| Anugulruengkitt et al. 202028 | Recent infection near delivery | NA | (i) Inadequate follow-up system (e.g. no system to recall patients and loss to follow-up during referral or after treatment initiation); and (ii) improper treatment prescription | NA | NA |

| de Oliviera et al. 202035 | NA | NA | Inadequate supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G | NA | NA |

| Swayze et al. 202234 | Late diagnosis during pregnancy | NA | (i) Inadequate supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G; and (ii) ineffective system for enabling patient records to be accessed at different sites | Patient attendance at, and level of engagement with, antenatal care | Low educational level |

| Delvaux et al. 202336 | NA | NA | (i) Inadequate follow-up system, including lack of contact information; and (ii) inadequate supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G | (i) Late presentation to antenatal services; and (ii) behavioural or mental health issues | (i) Distance from health services; and (ii) patient’s financial challenges |

| Liu et al. 202332 | NA | NA | NA | (i) Women presenting and diagnosed late in pregnancy (unable to complete treatment before delivery); and (ii) migrant women who did not hold a residency permit | NA |

| Mangone et al. 202310 | NA | (i) Lack of flexibility in treatment dosing; and (ii) cost of treatment | (i) Inadequate supply of, or access to, benzathine penicillin G; and (ii) long waiting time for treatment | (i) Lack of time; and (ii) childcare obligations | Transportation barriers |

| McDonald et al. 202344 | NA | NA | NA | (i) No or no timely treatment during pregnancy; and (ii) patients who identified as non-Hispanic Black or African–American, and Hispanic and Latino patients | NA |

| Carreira et al. 202440 | NA | NA | Health services that specialize in sexual and gender diversity available | HIV-positive patients were more likely to complete treatment but being tested for an HIV infection was associated with a lower likelihood of treatment completion | Patients who experienced verbal assaults for being transgender were less likely to complete treatment |

| Clarkson-During et al. 202445 | NA | NA | (i) Patients diagnosed in the emergency department had the lowest rate of treatment completion, followed by those diagnosed in primary care; and (ii) patients with private health insurance were more likely to complete treatment | (i) Patients aged 40–49 years were least likely to complete treatment, whereas those aged 18–24 years were most likely; and (ii) heterosexual patients were less likely to complete treatment than those who did not identify as heterosexual | NA |

| Tannis et al. 202446 | Pregnancy outcome before 35 weeks | NA | NA | Receiving inappropriately timed or no prenatal care | (i) Lack of health insurance; (ii) history of incarceration; (iii) history of homelessness; and (iv) reported substance use during pregnancy |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; NA: not applicable.

Discussion

In this review, we found that the limited supply of, and limited access to, benzathine penicillin G were frequently cited as reasons people diagnosed with syphilis of unknown duration or late syphilis did not complete the prescribed treatment regimen.10,29,34–37,41 This finding is supported by a WHO-led survey that found that 5% of countries reported benzathine penicillin G being out of stock in 2019.47 In December 2024, the United States also reported shortages of the drug, which were attributed to reliance on a single supplier and to a rise in the incidence of syphilis.48,49

Currently, few manufacturers produce the active pharmaceutical ingredient in benzathine penicillin G because: (i) demand is low compared to similar pharmaceutical products in production; (ii) the range of applications is decreasing; (iii) there are competitive financial pressures; and (iv) profit margins are narrow.49 Regrettably, supply shortages have led to non-recommended treatments being used and to countries procuring benzathine penicillin G from unregulated suppliers.48 To increase the accuracy of predicted demand and procurement requirements for benzathine penicillin G, WHO has announced plans to collaborate with Member States to improve the supply chain infrastructure.47 Other recommended structural solutions include: (i) more extensive market interventions; (ii) improvements in drug quality assurance processes to reduce the risk of manufacturing suspensions by regulatory authorities; (iii) increasing the supply of benzathine penicillin G;47,49 and (iv) encouraging countries to adopt mitigation strategies suited to their own individual requirements.49

At both national and regional levels, effective syphilis management strategies can involve: (i) increasing testing for the disease; (ii) training and capacity-building for health workers; (iii) improving community education; (iv) developing new pharmacological interventions (e.g. a single subcutaneous infusion of high-dose benzathine penicillin G instead of three intramuscular doses); (v) promoting organizational collaborations; and (vi) making health system governance more effective to optimize service delivery and policy implementation.50,51 A scoping review of global policy responses to syphilis found that no country had developed a comprehensive response that would lead to the control or elimination of syphilis in all key population groups.52 This finding was attributed to insufficient epidemiological surveillance, to a lack of clarity in promoting equity of access to health services, and to inadequate financing for sustainable policies. We found that equity of access had a substantial impact on treatment completion: people who had a low level of education,34,39 geographical or transport barriers to accessing health services,10,36,42 or financial challenges were all less likely to complete treatment.36

To facilitate timely follow-up of patients who require repeat doses of benzathine penicillin G, primary and tertiary health services need to improve patient management systems and infrastructure. Follow-up could be improved by: (i) ensuring that the contact details of patients commencing treatment are up to date;36 (ii) creating mechanisms that enable clinical data to be accessed at different sites in situations where patients frequently move between services;34 (iii) using recall reminders;30 (iv) providing treatment in nonclinical settings (e.g. in sex-on-premises venues);44 (v) training clinicians to make referrals and notify partners;44 and (vi) ensuring staff are allocated sufficient time and resources to adequately engage in follow-up.38

Difficulties with follow-up could also be overcome by developing alternative treatment regimens. Researchers have suggested that completion rates of benzathine penicillin G treatment for rheumatic heart disease could be improved by developing a new formulation that addresses issues with the dosing interval, pain and the administration mechanism.53 Other researchers have hypothesized that a single high-dose subcutaneous benzathine penicillin G infusion could achieve pharmaco-equivalence, leading to reduced health-care visits, improved adherence and lower health-care costs.54 A clinical trial is underway to examine the effectiveness of this approach for the treatment of syphilis.55

Most studies identified were conducted in the Region of the Americas. However, only three studies were from the WHO African Region, despite this region having the highest age-standardized incidence rates of syphilis in the world.56 Interestingly, no study we identified reported that pain affected treatment completion. In contrast, pain is frequently reported as a barrier to the completion of treatment of rheumatic heart disease.53 Few included studies examined treatment completion from the patient’s perspective, which may explain our finding.

Most studies in our review investigated factors that influenced the completion of syphilis treatment among pregnant women, despite the rate of syphilis among men who have sex with men rising in high-income countries.57 As a result, many of the barriers to treatment completion we identified are similar to those reported in an integrative review of inadequate syphilis treatment during pregnancy (e.g. the quality of antenatal care and late presentation to antenatal care).13 Nevertheless, we found additional social and economic factors associated with incomplete treatment, such as geographical and transportation barriers to accessing health services and financial challenges. In addition, our review provides some insights into how health services could increase treatment completion rates.

One study examined treatment completion rates among men who have sex with men and transgender women who have sex with men.9 Another examined completion rates among transgender women.40 Both reported that the completion rate for three doses of benzathine penicillin G was low. Interestingly, a study of the general population found that people who did not identify themselves as heterosexual were more likely to complete treatment.45 We found no studies that examined other priority population groups, such as sex workers or the Indigenous populations of Australia, Canada and the United States.58 It is likely that the factors influencing treatment completion in pregnant women differ from those in other priority population groups. For instance, case reviews of congenital syphilis in Australia’s Aboriginal population note that many women avoid contact with health services due to experiences of racism, having children removed from their care, and complications associated with homelessness and an itinerant lifestyle.59 Additionally, researchers highlighted how treatment uptake and completion by gender- and sexually diverse people may be negatively affected by the experience of verbal abuse and a lack of access to health services.40 For men who have sex with men, the existence of discriminatory laws that criminalize same-sex relationships may create a barrier to seeking health care.15 Targeted research involving other priority populations is warranted to better understand whether tailored interventions could increase the likelihood of treatment completion.

One strength of our review is that we employed the MetaQAT tool, which was specifically developed for public health research, to assess the quality of the studies included.27 Our review has several limitations. For example, we did not search the grey literature, the number of studies included was relatively small, only one person reviewed methodological quality, and few studies investigated treatment completion in population groups other than pregnant women. However, most studies involved the quantitative analyses of data from medical records and syphilis registers. Few qualitative studies examined reasons for inadequate treatment from the patient’s perspective.29,30 Consequently, our findings are generally limited to simplified variables that mostly quantify health workers’ observations. Recently, there have been increasing calls for qualitative research frameworks to investigate patients’ attitudes and subjective treatment experiences, including their ideas about medication efficacy, their perceptions of risk and how competing priorities are navigated.60,61 There is, then, a need for more qualitative research into factors that influence treatment completion.

In conclusion, our review highlights the importance of a comprehensive systems approach to increasing the treatment completion rate for syphilis of unknown duration and late syphilis. In addition to health service interventions, such as improving patient management systems, shortages in the supply of benzathine penicillin G and social inequalities must also be addressed. Furthermore, our findings reveal the importance of expanding syphilis research to encompass a wider spectrum of priority groups with a higher prevalence of the disease. Expanding the population groups being studied and employing a variety of data collection methods will lead to more tailored treatment interventions for syphilis that can respond effectively to the evolving epidemiology of the disease.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.National overview of STIs in 2023. Atlanta: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/sti-statistics/annual/summary.html [cited 2024 Nov 24].

- 2.Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053779 [cited 2024 Nov 24].

- 3.WHO guidelines for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549714 [cited 2024 Nov 24]. [PubMed]

- 4.Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, Johnston CM, Muzny CA, Park I, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021. Jul 23;70(4):1–187. 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phaosavasdi S, Snidvongs W, Thasanapradit P, Ungthavorn P, Bhongsvej S, Jongpiputvanich S, et al. Effectiveness of benzathine penicillin regimen in the treatment of syphilis in pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thai. 1989. Feb;72(2):101–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Díaz Olavarrieta C, Valencia J, Wilson K, García SG, Tinajeros F, Sanchez T. Assessing the effectiveness of a patient-driven partner notification strategy among pregnant women infected with syphilis in Bolivia. Sex Transm Infect. 2011. Aug;87(5):415–9. 10.1136/sti.2010.047985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullick S, Beksinksa M, Msomi S. Treatment for syphilis in antenatal care: compliance with the three dose standard treatment regimen. Sex Transm Infect. 2005. Jun;81(3):220–2. 10.1136/sti.2004.011999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotchford K, Lombard C, Zuma K, Wilkinson D. Impact on perinatal mortality of missed opportunities to treat maternal syphilis in rural South Africa: baseline results from a clinic randomized controlled trial. Trop Med Int Health. 2000. Nov;5(11):800–4. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang EC, Segura ER, Clark JL, Sanchez J, Lama JR. The syphilis care cascade: tracking the course of care after screening positive among men and transgender women who have sex with men in Lima, Peru. BMJ Open. 2015. Sep 18;5(9):e008552. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangone E, Bell J, Khurana R, Taylor MM. Treatment completion with three-dose series of benzathine penicillin among people diagnosed with late latent and unknown duration syphilis, Maricopa County, Arizona. Sex Transm Dis. 2023. May 1;50(5):298–303. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klausner JD, Freeman AH. Sequelae and long‐term consequences of syphilis infection. In: Smith JL, Brogden KA, Fratamico PM, editors. Sequelae and long‐term consequences of infectious diseases. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009. Jun 9: 187–204. 10.1128/9781555815486.ch10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eppes CS, Stafford I, Rac M. Syphilis in pregnancy: an ongoing public health threat. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022. Dec;227(6):822–38. 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres PMA, Reis ARP, Santos ASTD, Negrinho NBDS, Menegueti MG, Gir E. Factors associated with inadequate treatment of syphilis during pregnancy: an integrative review. Rev Bras Enferm. 2022. Sep 9;75(6):e20210965. 10.1590/0034-7167-2021-0965pt [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minichiello V, Rahman S, Hussain R. Epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in global indigenous populations: data availability and gaps. Int J STD AIDS. 2013. Oct;24(10):759–68. 10.1177/0956462413481526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuboi M, Evans J, Davies EP, Rowley J, Korenromp EL, Clayton T, et al. Prevalence of syphilis among men who have sex with men: a global systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000–20. Lancet Glob Health. 2021. Aug;9(8):e1110–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00221-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kevat PM, Reeves BM, Ruben AR, Gunnarsson R. Adherence to secondary prophylaxis for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: a systematic review. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2017;13(2):155–66. 10.2174/1573403X13666170116120828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Report of a WHO expert consultation. Geneva, 29 October – 1 November 2001. WHO technical report series 923. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42898 [cited 2024 Nov 24]. [PubMed]

- 18.Lizarondo L, Stern C, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, et al. Chapter 8: Mixed methods systematic reviews. In: Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide: JBI; 2024. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global/ [cited 2023 Oct 12].

- 19.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021. Mar 29;372(71):n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobin R, Vujcich D, Manning L, Norman R, Ong J, Eadie-Mirams E, et al. Factors influencing adult and adolescent completion of a three-dose regimen of benzathine penicillin G for the treatment of syphilis: a mixed methods systematic review protocol. PROSPERO record CRD42023406247. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2023. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023406247 [cited 2023 Oct 12].

- 21.Stokes JH, Sternberg TH, Schwartz WH, Mahoney JF, Moore JE, Wood WB. The action of penicillin in late syphilis, including neurosyphilis, benign late syphilis and late congenital syphilis: preliminary report. JAMA. 1944. Sep 9;126(2):73–80. 10.1001/jama.1944.02850370011003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS One. 2015. Sep 17;10(9):e0138237. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2017. Jan;105(1):111. Corrected and republished from: J Med Libr Assoc. 2016. Jul;104(3): 240–3. 10.5195/jmla.2017.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan – a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016. Dec 5;5(1):210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabate E, editor. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42682 [cited 2024 Jan 11]. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peh KQE, Kwan YH, Goh H, Ramchandani H, Phang JK, Lim ZY, et al. An adaptable framework for factors contributing to medication adherence: results from a systematic review of 102 conceptual frameworks. J Gen Intern Med. 2021. Sep;36(9):2784–95. 10.1007/s11606-021-06648-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosella L, Bowman C, Pach B, Morgan S, Fitzpatrick T, Goel V. The development and validation of a meta-tool for quality appraisal of public health evidence: meta quality appraisal tool (MetaQAT). Public Health. 2016. Jul;136:57–65. 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anugulruengkitt S, Yodkitudomying C, Sirisabya A, Chitsinchayakul T, Jantarabenjakul W, Chaithongwongwatthana S, et al. Gaps in the elimination of congenital syphilis in a tertiary care center in Thailand. Pediatr Int. 2020. Mar;62(3):330–6. 10.1111/ped.14132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beksinska ME, Mullick S, Kunene B, Rees H, Deperthes B. A case study of antenatal syphilis screening in South Africa: successes and challenges. Sex Transm Dis. 2002. Jan;29(1):32–7. 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campos AL, Araújo MA, Melo SP, Gonçalves ML. Epidemiologia da sífilis gestacional em Fortaleza, Ceará, Brasil: um agravo sem controle. Cad Saude Publica. 2010. Sep;26(9):1747–55. Portuguese. 10.1590/S0102-311X2010000900008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kidd S, Bowen VB, Torrone EA, Bolan G. Use of national syphilis surveillance data to develop a congenital syphilis prevention cascade and estimate the number of potential congenital syphilis cases averted. Sex Transm Dis. 2018. Sep;45(9S) Suppl 1:S23–8. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu H, Chen N, Tang W, Shen S, Yu J, Xiao H, et al. Factors influencing treatment status of syphilis among pregnant women: a retrospective cohort study in Guangzhou, China. Int J Equity Health. 2023. Apr 6;22(1):63. 10.1186/s12939-023-01866-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutgers S. Syphilis in pregnancy: a medical audit in a rural district. Cent Afr J Med. 1993. Dec;39(12):248–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swayze EJ, Cambou MC, Melo M, Segura ER, Raney J, Santos BR, et al. Ineffective penicillin treatment and absence of partner treatment may drive the congenital syphilis epidemic in Brazil. AJOG Glob Rep. 2022. May;2(2):100050. 10.1016/j.xagr.2022.100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Oliveira SIM, de Oliveira Saraiva COP, de França DF, Ferreira Júnior MA, de Melo Lima LH, de Souza NL. Syphilis notifications and the triggering processes for vertical transmission: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. Feb 5;17(3):984. 10.3390/ijerph17030984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delvaux T, Ouk V, Samreth S, Yos S, Tep R, Pall C, et al. Challenges and outcomes of implementing a national syphilis follow-up system for the elimination of congenital syphilis in Cambodia: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2023. Jan 10;13(1):e063261. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nunes JT, Marinho ACV, Davim RMB, de Oliveira Silva GG, Felix RS, de Martino MMF. Syphilis in gestation: perspectives and nurse conduct. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE on line (REUOL). 2017. Dec 1;11(12):4875–84. 10.5205/1981-8963-v11i12a23573p4875-4884-2017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodrigues AR, da Silva MA, Cavalcante AE, Moreira AC, Netto JJ, Goyanna NF. Atuação de enfermeiros no acompanhamento da sífilis na atenção primária. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE on line (REUOL). 2016. Apr;10(4):1247–55. Portuguese. 10.5205/1981-8963-v11i12a23573p4875-4884-2017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu L, Qin M, Du L, Xie RH, Wong T, Wen SW. Maternal and congenital syphilis in Shanghai, China, 2002 to 2006. Int J Infect Dis. 2010. Sep;14 Suppl 3:e45–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carreira LFG, Veras MAS, Benzaken AS, Queiroz RSB, Silveira EPR, Oliveira EL, et al. [Factors associated with the completion of syphilis treatment among transgender women and travestis, in five Brazilian capitals, 2019-2021: a multicenter cross-sectional study.] Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2024. Dec 6;33 spe1:e2024294. Portuguese. 10.1590/s2237-96222024v33e2024294.especial.pt [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos RRD, Niquini RP, Domingues RMSM, Bastos FI. Knowledge and compliance in practices in diagnosis and treatment of syphilis in maternity hospitals in Teresina – PI, Brazil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017. Sep;39(9):453–63. 10.1055/s-0037-1606245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman MM, Hoover A, Johnson C, Peterman TA. Preventing congenital syphilis – opportunities identified by congenital syphilis case review boards. Sex Transm Dis. 2019. Feb;46(2):139–42. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Yu Y, Yang H, Xu H, Vermund SH, Liu K. Surveillance of maternal syphilis in China: pregnancy outcomes and determinants of congenital syphilis. Med Sci Monit. 2018. Oct 29;24:7727–35. 10.12659/MSM.910216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonald R, O’Callaghan K, Torrone E, Barbee L, Grey J, Jackson D, et al. Vital signs: missed opportunities for preventing congenital syphilis – United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023. Nov 17;72(46):1269–74. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7246e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarkson-During A, Almirol E, Eller D, Hazra A, Stanford KA. Risk factors for treatment non-completion among patients with syphilis. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2024. Jul 30;11:20499361241265941. 10.1177/20499361241265941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tannis A, Miele K, Carlson JM, O’Callaghan KP, Woodworth KR, Anderson B, et al. Syphilis treatment among people who are pregnant in six U.S. states, 2018–2021. Obstet Gynecol. 2024. Jun 1;143(6):718–29. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Global shortages of penicillin. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/stis/treatment/shortages-of-penicillin [cited 2023 Jan 23].

- 48.FDA drug shortages. Current and resolved drug shortages and discontinuations reported to FDA [internet]. Silver Spring: US Food and Drug Administration; 2025. Available from: https://dps.fda.gov/drugshortages [cited 2024 Dec 12].

- 49.Seghers F, Taylor MM, Storey A, Dong J, Wi TC, Wyber R, et al. Securing the supply of benzathine penicillin: a global perspective on risks and mitigation strategies to prevent future shortages. Int Health. 2024. May 1;16(3):279–82. 10.1093/inthealth/ihad087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fajemiroye JO, Moreira ALE, Ito CRM, Costa EA, Queiroz RM, Ihayi OJ, et al. Advancing syphilis research: exploring new frontiers in immunology and pharmacological interventions. Venereology (Basel). 2023;2(4):147–63. 10.3390/venereology2040013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenspan J, Akbarali S, Heyer K, Brazeel C, McClure J. Effective public health approaches to reducing congenital syphilis. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2024. Jan-Feb 01;30(1):140–6. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Almeida MCD, Cordeiro AMR, Cunha-Oliveira A, Barros DMS, Santos DGSM, Lima TS, et al. Syphilis response policies and their assessments: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2022. Sep 16;10:1002245. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1002245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyber R, Boyd BJ, Colquhoun S, Currie BJ, Engel M, Kado J, et al. Preliminary consultation on preferred product characteristics of benzathine penicillin G for secondary prophylaxis of rheumatic fever. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2016. Oct;6(5):572–8. 10.1007/s13346-016-0313-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kado JH, Salman S, Henderson R, Hand R, Wyber R, Page-Sharp M, et al. Subcutaneous administration of benzathine benzylpenicillin G has favourable pharmacokinetic characteristics for the prevention of rheumatic heart disease compared with intramuscular injection: a randomized, crossover, population pharmacokinetic study in healthy adult volunteers. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020. Oct 1;75(10):2951–9. 10.1093/jac/dkaa282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trial registered on ANZCTR: ACTRN12622000349741. 'One injection vs. three': clinical evaluation of a single, high dose subcutaneous infusion of benzathine penicillin G for treatment of syphilis (SCIP Syphilis). Camperdown: The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR); 2023. Available from: https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=383579&isReview=true [cited 2024 Mar 25].

- 56.Tao YT, Gao TY, Li HY, Ma YT, Li HJ, Xian-Yu CY, et al. Global, regional, and national trends of syphilis from 1990 to 2019: the 2019 global burden of disease study. BMC Public Health. 2023. Apr 24;23(1):754. 10.1186/s12889-023-15510-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020. Feb 27;382(9):845–54. 10.1056/NEJMra1901593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kojima N, Klausner JD. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018. Mar;5(1):24–38. 10.1007/s40471-018-0138-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Congenital syphilis case review: a report on outcomes with recommendations for prevention and management of future cases. Adelaide: Department for Health and Wellbeing, Government of South Australia; 2021. Available from: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/5d494f69-0250-496a-8180-b92110b1e757/Congenital+Syphilis+Care+Review+Report+-+PUBLIC+VERSION+-+May2021.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE-5d494f69-0250-496a-8180-b92110b1e757-pbmvsOn [cited 2023 Jun 8].

- 60.McHorney CA. The contribution of qualitative research to medication adherence. In: Olson K, Young R, Schultz I, editors. Handbook of qualitative health research for evidence-based practice. New York: Springer; 2016:473–94. Available from: [cited 2023 Jun 8]. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2920-7_28 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Camp YP, Bastiaens H, Van Royen P, Vermeire E. Qualitative evidence in treatment adherence. In: Olson K, Young R, Schultz I, editors. Handbook of qualitative health research for evidence-based practice. New York: Springer; 2016:373–90. Available from: [cited 2023 Jun 8]. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2920-7_22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]