Abstract

An algorithm was implemented in the clinical microbiology laboratory to assess the clinical significance of organisms that are often considered contaminants (coagulase-negative staphylococci, aerobic and anaerobic diphtheroids, Micrococcus spp., Bacillus spp., and viridans group streptococci) when isolated from blood cultures. From 25 August 1999 through 30 April 2000, 12,374 blood cultures were submitted to the University of Iowa Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Potential contaminants were recovered from 495 of 1,040 positive blood cultures. If one or more additional blood cultures were obtained within ±48 h and all were negative, the isolate was considered a contaminant. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of these probable contaminants was not performed unless requested. If no additional blood cultures were submitted or there were additional positive blood cultures (within ±48 h), a pathology resident gathered patient clinical information and made a judgment regarding the isolate's significance. To evaluate the accuracy of these algorithm-based assignments, a nurse epidemiologist in approximately 60% of the cases performed a retrospective chart review. Agreement between the findings of the retrospective chart review and the automatic classification of the isolates with additional negative blood cultures as probable contaminants occurred among 85.8% of 225 isolates. In response to physician requests, AST had been performed on 15 of the 32 isolates with additional negative cultures considered significant by retrospective chart review. Agreement of pathology resident assignment with the retrospective chart review occurred among 74.6% of 71 isolates. The laboratory-based algorithm provided an acceptably accurate means for assessing the clinical significance of potential contaminants recovered from blood cultures.

False-positive blood cultures lead to additional laboratory tests, unnecessary antibiotic use, and longer hospitalizations that increase patient care costs (2, 16). Assessing the clinical significance of blood culture isolates can be difficult, but actions based on the accurate identification of contaminants may minimize the associated costs and lower future contaminant rates. An algorithm was implemented in the University of Iowa Clinical Microbiology Laboratory to assess the clinical significance of organisms that are often considered contaminants when isolated from blood cultures. An independent retrospective chart review was used to assess the accuracy of automatic assignments made by the algorithm, determinations of clinical significance by pathology residents, and the reclassification of probable contaminant isolates as pathogens after physicians requested antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST).

(This report was presented in part at the 101st General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, 21 May 2001 [abstr. C-65].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From 25 August 1999 through 30 April 2000, 12,374 blood culture sets were submitted to the University of Iowa Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. The majority of blood culture sets consisted of an aerobic and anaerobic bottle (Organon Teknika, Durham, N.C.) inoculated by phlebotomists, nurses, residents, and medical students. Each bottle within a blood culture set was inoculated with blood obtained from the same venipuncture site or line. The blood culture bottles were incubated at 37°C in a continuous monitoring system (BacT/Alert; Organon Teknika) for up to 5 days. When a blood culture was signaled positive, a gram stain was performed and the results were reported to the floor. The blood culture broth was plated on solid medium, and the organism was identified by conventional methods when growth was observed (11).

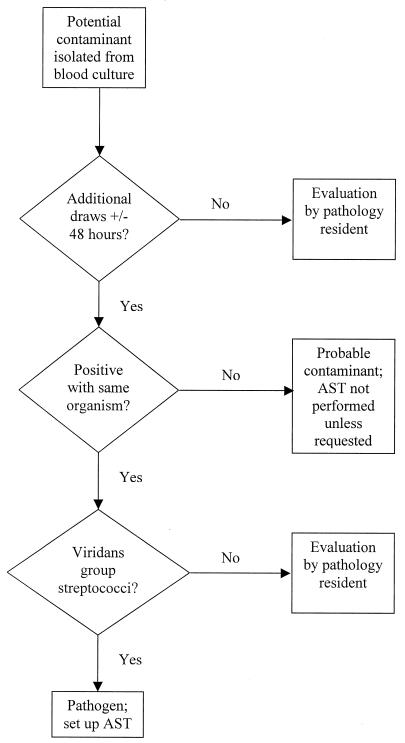

Organisms considered to be potential contaminants (coagulase-negative staphylococci [CNS], aerobic diphtheroids, anaerobic diphtheroids, Micrococcus spp., Bacillus spp., and viridans group streptococci [VGS]) were further evaluated with an algorithm (Fig. 1) based on the number of positive blood cultures as follows. (i) When one or more additional blood cultures were obtained from a patient within ±48 h and all were negative (no growth detected at that time), the technologist automatically reported the isolate as a probable contaminant and AST was not performed unless the patient's physician contacted the laboratory. When a physician requested AST, the original classification as a probable contaminant was removed from the hospital information system and replaced with the phrase “susceptibility test results to follow.” (ii) When no additional blood cultures were obtained from a patient within ±48 h, a pathology resident gathered clinical data from the hospital's computerized information system and often discussed the potential significance of the isolate with a physician caring for the patient. On the basis of the judgment of the resident, the isolate was classified as a pathogen, indeterminate, or a contaminant. AST was performed only for pathogens and indeterminate isolates. (iii) When additional positive blood cultures (with the same organism) were obtained from a patient within ±48 h, with one exception, isolates were assessed by a pathology resident to determine their clinical significance as described for condition ii above. Isolates of VGS with additional positive blood cultures were automatically considered to be pathogens.

FIG. 1.

Overview of the laboratory-based algorithm used in this study.

The number of bottles positive within a set was not considered in the algorithm—each blood culture set was treated as a single entity. The 48-h time period specified in the algorithm was based on collection times and considered an absolute cutoff. No consideration was given to the amount of time for which an additional negative culture had been incubated. If an additional negative blood culture later turned positive, the pathology resident would be consulted as outlined for condition iii (isolates with additional positive blood cultures) and asked to evaluate the significance of the isolate obtained from the newly positive culture. The classification of an isolate originally as a probable contaminant was not altered unless a physician requested AST as described for condition i above.

Pathology residents were given a reference that discusses the clinical significance of positive blood cultures (17) and instructed to consider each patient's clinical history, leukocyte count, body temperature, number of positive blood cultures, results from other sites, radiographic data, histopathologic findings, and current status to arrive at a judgment of an isolate's significance. In addition, conversations with physicians caring for patients were encouraged, especially prior to classification of an isolate as a contaminant.

To assess the accuracy of the assignments, a retrospective chart review was performed in approximately 60% of the cases by a nurse epidemiologist with the assistance of an infectious disease physician. Determination of whether the blood culture isolate was clinically significant was based on this chart review, which included the patient's clinical signs and symptoms, leukocyte count, other culture results, imaging studies, and overall clinical course.

Isolates with additional negative cultures that were initially classified as contaminants but for which AST was performed because of a request by the patient's physician were subsequently reclassified as pathogens for the purpose of this evaluation. Error rates were determined for individual steps (isolates with additional negative cultures automatically considered contaminants, isolates reclassified as pathogens after a physician's request for AST, pathology residents' evaluation of isolates, and VGS isolates automatically considered pathogens because of additional positive blood cultures), as well as for the overall performance of the combined steps. A very major (VM) error was defined as classification of an isolate as a contaminant that was determined to be clinically significant by the retrospective chart review. A major (M) error was defined as classification of an isolate as indeterminate or a pathogen that was not considered clinically significant by the retrospective chart review. For assessment of the overall performance of the automatic steps of the algorithm and evaluations by individuals, isolates that were reclassified as pathogens because a physician called and requested AST were only considered on the basis of their final classification as pathogens and considered to represent M errors if not found to be clinically significant by the retrospective chart review.

RESULTS

Organisms considered to be potential contaminants (CNS, aerobic diphtheroids, anaerobic diphtheroids, Micrococcus spp., Bacillus spp., and VGS) were isolated from 495 of 1,040 positive blood cultures during the study period (Table 1). Of these 495 isolates, 286 (57.8%) were automatically classified as probable contaminants because of additional negative blood cultures (26 of these isolates were reclassified as pathogens after a physician-requested AST), 171 (34.5%) required investigation by a pathology resident, and 15 (3.0%) were automatically classified as pathogens (VGS with additional positive cultures). The algorithm was not applied to 4.6% of the 495 isolates: 17 isolates from deceased patients and 6 CNS isolates from babies (for reasons detailed below). The percentages of the organism groups determined to be contaminants according to the final assignments were as follows: CNS, 61.7%; VGS, 42.5%; aerobic diphtheroids, 75.8%; Bacillus spp., 28.6%; Micrococcus spp., 80%; anaerobic diphtheroids, 77.8%.

TABLE 1.

Assignments of clinical significance for 495 blood culture isolates

| Organism group | No. of isolates | No. (%) of isolates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contaminant | Indeterminate | Pathogen | Deceased patienta | NICU/INSb | ||

| CNS | 389 | 240 (61.7) | 49 (12.6) | 82 (21.1) | 12 (3.1) | 6 (1.5) |

| Additional negative within ±48 h | 232 | 211 (90.9)c | 18 (7.7)d | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Only blood culture within ±48 h | 57 | 20 (35.7)e | 20 (35.1)e | 8 (14.3)e | 5 (8.9) | 4 (7.1) |

| Additional positive within ±48 h | 100 | 9 (8.8)e | 29 (29.0)e | 56 (54.9)e | 5 (4.9) | 1 (1.0) |

| VGS | 40 | 17 (42.5) | 2 (5.0) | 18 (45.0) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Additional negative within ±48 h | 16 | 13 (81.3)c | 3 (18.8)d | |||

| Only blood culture within ±48 h | 9 | 4 (44.4)e | 2 (22.2)e | 3 (33.3) | ||

| Additional positive within ±48 h | 15 | 15 (100)f | ||||

| Aerobic diphtheroids | 33 | 25 (75.8) | 3 (9.1) | 5 (15.1) | ||

| Additional negative within ±48 h | 20 | 20 (100)c | ||||

| Only blood culture within ±48 h | 6 | 3 (50.0)e | 3 (50.0)e | |||

| Additional positive within ±48 h | 7 | 2 (28.6)e | 5 (71.4)e | |||

| Bacillus spp. | 14 | 4 (28.6) | 1 (7.1) | 7 (50.0) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Additional negative within ±48 h | 6 | 3 (50.0)c | 3 (50.0)d | |||

| Only blood culture within ±48 h | 2 | 1 (50.0)e | 1 (50.0)e | |||

| Additional positive within ±48 h | 6 | 4 (66.7)e | 2 (33.3) | |||

| Micrococcus spp. | 10 | 8 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) | |||

| Additional negative within ±48 h | 9 | 7 (77.8)c | 2 (22.2)d | |||

| Only blood culture within ±48 h | 1 | 1 (100)e | ||||

| Additional positive within ±48 h | ||||||

| Anaerobic diphtheroids | 9 | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | |||

| Additional negative within ±48 h | 6 | 6 (100)c | ||||

| Only blood culture within ±48 h | 1 | 1 (100)e | ||||

| Additional positive within ±48 h | 2 | 2 (100)e | ||||

| Total | 495 | 301 (60.8) | 57 (11.5) | 114 (23.0) | 17 (3.4) | 6 (1.2) |

| Positive blood cultures (all organisms) | 1,040 | 301 (28.9) | 57 (5.5) | 114 (11.0) | 17 (1.6) | 6 (0.6) |

| Total blood cultures drawn | 12,374 | 301 (2.4) | 57 (0.5) | 114 (0.9) | ||

The significance of isolates belonging to deceased patients was not determined.

Isolates from the NICU and INS during the latter half of the study period, when neonatologists requested all CNS isolates to be considered significant.

Isolates considered contaminants because of additional negative blood cultures.

Isolates initially classified as contaminants because of additional negative cultures but subsequently considered to be pathogens after a physician called and requested AST.

Isolates evaluated by pathology residents.

VGS with additional positive blood cultures were automatically considered pathogens.

The only opposition from clinicians to implementation of the algorithm was from neonatologists approximately halfway through the study period. At their request, the algorithm was modified so that isolates of CNS from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and intermediate care nursery (INS) would always be considered significant. The six subsequent CNS isolates from these areas were reviewed retrospectively, and four (67%) were not considered significant. The NICU/INS isolates, as well as those collected from patients who were deceased, were not included in the evaluation of the algorithm.

The final assignment of 301 isolates on the basis of the automatic steps of the algorithm, evaluations by pathology residents, and the reclassification of probable contaminant isolates as pathogens after physicians requested AST was compared to the significance determined by the retrospective chart review (Table 2. Only the significance of the first blood culture isolate from a patient was determined by the retrospective chart review. Of the 301 isolates, 225 (74.7%) were automatically classified as probable contaminants because of additional negative blood cultures (19 of these isolates were reclassified as pathogens after a physician requested AST), 71 (23.6%) required investigation by a pathology resident, and 5 (1.7%) were automatically classified as pathogens (VGS with additional positive cultures). Agreement between the final assignment and the retrospective chart review occurred among 87.1% of 233 CNS, 91.3% of 23 VGS, 81.8% of 22 aerobic diphtheroids, 100% of 7 Bacillus sp., 77.8% of 9 Micrococcus sp., and 85.7% of 7 anaerobic diphtheroid isolates. Overall, VM errors occurred in 6.3% of the cases and M errors occurred in 6.6% of the cases.

TABLE 2.

Agreement of assignment with retrospective chart review for 301 isolates

| Assignment | Retrospective chart review

|

No. (%) of isolates

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. significant | No. not significant | Agreement | VM errora | M errorb | |

| CNS (n = 233) | 203 (87.1) | 14 (6.0) | 16 (6.9) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 179) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturesc | 13 | 151 | |||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 1 | 11 | |||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | 3 | ||||

| Indeterminate (n = 24) | |||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 7 | 7 | |||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | 8 | 2 | |||

| Pathogen (n = 30) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturese | 9 | 3 | |||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 3 | 4 | |||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | 11 | ||||

| VGS (n = 23) | 21 (91.3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 14) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturesc | 1 | 10 | |||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 3 | ||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Indeterminate (n = 1) | |||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 1 | ||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Pathogen (n = 8) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturese | 3 | ||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | |||||

| Additional positive blood culturesf | 5 | ||||

| Aerobic diphtheroids (n = 22) | 18 (81.8) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 18) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturesc | 2 | 14 | |||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 1 | ||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | 1 | ||||

| Indeterminate (n = 3) | |||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 2 | 1 | |||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Pathogen (n = 1) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturese | |||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | |||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | 1 | ||||

| Bacillus spp. (n = 7) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 4) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturesc | 3 | ||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 1 | ||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Indeterminate (n = 1) | |||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 1 | ||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Pathogen (n = 2) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturese | 2 | ||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | |||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Micrococcus spp. (n = 9) | 7 (77.8) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 7) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturesc | 1 | 6 | |||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | |||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | /PICK>{tt} | ||||

| Indeterminate (n = 0) | |||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | |||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Pathogen (n = 2) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturese | 1 | 1 | |||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | |||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Anaerobic diphtheroids (n = 7) | 6 (85.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 6) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturesc | 5 | ||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | 1 | ||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| Indeterminate (n = 1) | |||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | |||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | 1 | ||||

| Pathogen (n = 0) | |||||

| Additional negative blood culturese | |||||

| Only blood culture obtainedd | |||||

| Additional positive blood culturesd | |||||

| All organisms (n = 301) | 262 (87.0) | 19 (6.3) | 20 (6.6) | ||

Isolate classified as contaminant by the algorithm but determined to be clinically significant by retrospective chart review.

Isolate classified as indeterminant or a pathogen by the algorithm but not considered significant by retrospective chart review.

Isolates considered contaminants because of additional negative blood cultures.

Isolates evaluated by pathology residents.

Isolates initially classified as contaminants because of additional negative cultures but subsequently considered to be pathogens after a physician called and requested AST.

VGS with additional positive blood cultures were automatically considered pathogens.

Agreement between the findings of the retrospective chart review and the automatic classification by the algorithm of the 225 isolates with additional negative blood cultures as probable contaminants occurred among 85.8% of those isolates (14.2% VM error rate; Table 3). In response to physician requests, AST had been performed on 15 of the 32 isolates with additional negative cultures considered significant by a retrospective chart review. The agreement of the reclassification of the 19 isolates as pathogens (because of AST requests) with the retrospective chart review was 78.9% (21.1% M error rate; Table 4). The VM error rate for the overall algorithm would have been 11.3% (34 of 301) and the M error rate would have been 5.3% (16 of 301) if the 19 isolates had not been reclassified as pathogens.

TABLE 3.

Agreement of automatic classification of isolates with additional negative blood cultures as probable contaminants with retrospective chart review

| Isolates with additional negative blood cultures | Retrospective chart review

|

% Agreement | % VM errorsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. significant | No. not significant | |||

| CNS (n = 176) | 22 | 154 | 87.5 | 12.5 |

| VGS (n = 14) | 4 | 10 | 71.4 | 28.6 |

| Aerobic diphtheroids (n = 16) | 2 | 14 | 87.5 | 12.5 |

| Bacillus spp. (n = 5) | 2 | 3 | 60 | 40 |

| Micrococcus spp. (n = 9) | 2 | 7 | 77.8 | 22.2 |

| Anaerobic diphtheroids (n = 5) | 5 | 100 | 0 | |

| All organisms (n = 225) | 32 | 193 | 85.8 | 14.2 |

Isolate initially classified as contaminant by the algorithm but determined to be clinically significant by retrospective chart review. Nineteen isolates were later considered pathogens after a physician called requesting AST.

TABLE 4.

Agreement of reclassification of isolates with additional negative blood cultures as pathogens after physician requested AST with retrospective chart review

| Isolates with additional negative blood cultures reclassified as pathogens | Retrospective chart review

|

% Agreement | % M errorsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. significant | No. not significant | |||

| CNS (n = 12) | 9 | 3 | 75 | 25 |

| VGS (n = 3) | 3 | 100 | 0 | |

| Aerobic diphtheroids (n = 0) | ||||

| Bacillus spp. (n = 2) | 2 | 100 | 0 | |

| Micrococcus spp. (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | 50 | 50 |

| Anaerobic diphtheroids (n = 0) | ||||

| All organisms (n = 19) | 15 | 4 | 78.9 | 21.1 |

Isolate reclassified as a pathogen because of physician request to perform AST but not considered significant by retrospective chart review.

Agreement of pathology resident assignments with retrospective chart reviews occurred among 74.6% of 71 isolates (2.8% VM error rate, 22.5% M error rate; Table 5). The five VGS isolates with additional positive cultures that were automatically classified as pathogens by the algorithm were all considered significant by the retrospective chart review (Table 2).

TABLE 5.

Agreement of pathology resident assignment with retrospective chart review

| Pathology resident assignment | Retrospective chart review

|

No. (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. significant | No. not significant | Agreement | VM errorsa | M errorsb | |

| CNS (n = 57) | 43 (75.4) | 1 (1.8) | 13 (22.8) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 15) | 1 | 14 | |||

| Indeterminate (n = 24) | 15 | 9 | |||

| Pathogen (n = 18) | 14 | 4 | |||

| VGS (n = 4) | 3 (75.0) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 3) | 3 | ||||

| Indeterminate (n = 1) | 1 | ||||

| Pathogen (n = 0) | |||||

| Aerobic diphtheroids (n = 6) | 4 (66.6) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 2) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Indeterminate (n = 3) | 2 | 1 | |||

| Pathogen (n = 0) | 1 | ||||

| Bacillus spp. (n = 2) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 1) | 1 | ||||

| Indeterminate (n = 1) | 1 | ||||

| Pathogen (n = 0) | |||||

| Micrococcus spp. (n = 0) | |||||

| Anaerobic diphtheroids (n = 2) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Contaminant (n = 1) | 1 | ||||

| Indeterminate (n = 1) | 1 | ||||

| Pathogen (n = 0) | |||||

| All organisms (n = 71) | 35 | 36 | 53 (74.6) | 2 (2.8) | 16 (22.5) |

Isolate classified as a contaminant by a pathology resident but determined to be clinically significant by the retrospective chart review.

Isolate classified as indeterminate or a pathogen by a pathology resident but not considered significant by the retrospective chart review.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies suggest that more than 40% of all positive blood cultures may represent contaminants (9, 17). The problem of false-positive blood cultures and the associated costs has been discussed for many years. In 1984, John and Bannister estimated the annual cost of false-positive blood cultures in the United States as possibly exceeding 22 million dollars (7). Multivariate analyses have shown contaminants to be independently correlated with a 20% increase in subsequent laboratory costs and 39% higher antimicrobial charges (2). Souvenir et al. reported the use of antibiotics to treat 41% of 59 patients with false-positive blood cultures, with vancomycin used for 83% of the treated pseudobacteremic patients (16). The cost for inappropriate therapy was approximately $1,000/patient (16).

Thirty years ago, MacGregor proposed guidelines for the differentiation of contaminated from significant positive blood cultures on the basis of the organism identification and the number of positive cultures after noting that only 11% of contaminated cultures had additional positive cultures while 69% of significant isolates had more than one positive culture (9). CNS, diphtheroids, bacilli, and alpha- or nonhemolytic streptococci were often contaminants (9). Although contamination may occur at any stage of blood culture processing, the continued predominance of skin flora organisms in false-positive cultures points to insufficient skin disinfection and poor phlebotomy technique as primary causes of pseudobacteremia (4).

Bates and Lee developed a model based on four factors (time to positivity, additional positive blood cultures, organism category, and clinical risk class) to help clinicians determine the significance of a blood culture isolate at the time of the initial report by the laboratory (3). Ram et al. validated Bates' model and also found that a modified version, with elimination of the clinical risk class, performed as well as the original algorithm (13). Bates' statement that “the most significant limitation” of his study was “the lack of an independent gold standard for the diagnosis of bacteremia” continues to be true today (3). Although subjective and cumbersome, the optimal approach to distinguishing between true bacteremia and a contaminant is a comprehensive assessment of the patient's clinical and microbiologic data by an infectious disease expert (15). This is not a feasible option for a microbiology laboratory to employ when deciding whether to perform AST on a positive blood culture isolate. The algorithm we implemented was based on MacGregor's early observation of the importance of the number of positive cultures (9) and was limited to organisms that colonize skin.

Because of data that suggest that the number of bottles positive within a set (typically an aerobic and anaerobic bottle filled from a single venipuncture sample) is not useful in predicting true bacteremia, this information was not incorporated into our algorithm (10, 14). A frequently referenced paper urges caution before calling a single positive blood culture a contaminant after no difference in hypothermia, fever, leukocytosis, or mortality was found in patients with CNS in one bottle versus two or more bottles (12). That study used the number of positive single bottles rather than culture sets as the basis for comparison, and the exact number of patients with a single bottle positive was not reported but was less than 16 (12). The study design and small patient sample make it difficult to use the data (12) as an argument against our algorithm's automatic classification of a single positive blood culture with additional negative cultures as a contaminant. Some of the patients with one bottle positive only had one set of cultures drawn (12). The significance of these cultures would be evaluated by a pathology resident according to our algorithm.

Another report found no difference in the frequency of septicemia among 36 patients with CNS in a single bottle compared to 38 patients with two or more bottles positive (5). Again, the small sample size and criteria based on the number of bottles (rather than sets) positive limit the strength of these data (5) as evidence to refute our algorithm design. A recent analysis found that more than half of the reported bloodstream infections due to CNS in the Evaluation of Processes and Indicators in Infection Control study were single positive blood cultures and suggested that bloodstream infection rates may be overestimated when using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance definition (L. C. McDonald, R. Carrico, B. Simmons, et al., 11th Annu. Sci. Meet. Soc. Healthcare Epidemiol. Am., Toronto, Ontario, Canada, abstr. 105, 2001). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of nosocomial bloodstream infection when a skin flora organism is isolated from a single blood culture only requires an intravenous line and antimicrobial therapy to have been instituted in addition to fever, chills, or hypotension (6). At least one of these nonspecific signs or symptoms of infection is present in almost all patients from whom blood cultures are obtained.

At the University of Michigan, Kirchhoff and Sheagren judged 85% of 694 CNS isolates to be contaminants but automatically considered isolates from patients with single positive CNS cultures to be contaminants and only reviewed the charts of patients with multiple positive cultures done ≤10 days apart (70 patients with 221 positive cultures) (8). More than half (52.9%) of the 221 isolates were determined to be contaminants, and the authors suggested that microbiology laboratories should limit AST of CNS to significant isolates (8). Further support for a laboratory-based algorithm came from Archer, who proposed that the laboratory should implement methods to identify high-probability contaminants (i.e., single positive blood cultures with additional negative cultures) and not proceed with AST unless it is requested by a clinician (1).

During our study period, the percentage of CNS isolates classified as contaminants (61.7%; Table 1) was lower than that reported by Weinstein (81.9%) (17). The remaining percentages of isolates classified as indeterminate and pathogens (12.6 and 21.1%) were consequently higher than those of Weinstein et al. (5.8 and 12.4%) (17). We believe that these differences are evidence of an appropriate tendency of our pathology residents (compared to infectious disease experts utilized in other studies) to err on the side of overcalling significance. Of the 20 M errors revealed by the retrospective chart review, 16 were attributed to pathology residents and 4 were attributed to clinicians calling and requesting AST of isolates with additional negative cultures. A negative impact from the M errors was not apparent. AST was performed on the isolates, and the results reported as would have been done if we had not implemented the algorithm.

Only two VM errors were a result of a pathology resident calling a significant isolate a contaminant. The other VM errors involved isolates automatically classified as contaminants because of additional negative cultures. The alternative of assessing every positive blood culture (an additional 289 isolates during our 8-month study period) would overly burden pathology residents and result in too many phone calls to clinicians. All of the patients associated with the VM errors received appropriate antimicrobial therapy despite the laboratory's report that the isolate was a probable contaminant.

The microbiology laboratory avoided performing AST on 301 isolates classified as contaminants during the 8-month period. With $46.25 billed for each AST, $13,921.25 in microbiology charges was deferred. At our institution, continued use of the algorithm should result in an annual reduction of unnecessary patient charges by $20,881.88.

It is hoped that reporting of a nonsignificant isolate as a probable contaminant decreases the likelihood that a patient will receive therapy. Of the 165 patients with CNS isolates deemed nonsignificant by a retrospective chart review and reported as probable contaminants by the laboratory, only 35 (21%) were receiving vancomycin more than 30 h after the report. Without a control group, it is difficult to ascribe meaning to this information. Souvenir reported that 34% of 59 false-positive blood culture isolates were treated with vancomycin (16), while a smaller percentage of pseudobacteremic patients in our study received a full course of vancomycin (21%; P = 0.04 by the Fisher exact test). This difference may reflect an effect of our laboratory reporting on clinicians' behavior; however, other factors (i.e., physician and patient characteristics) must also be considered.

Despite the inherent difficulty of discerning bacteremia from pseudobacteremia, the algorithm provided an acceptably accurate means for assessing the clinical significance of potential contaminants recovered from blood cultures. We believe it is important for clinical microbiology laboratories to attempt to identify false-positive blood cultures in order to limit further microbiology testing of the isolate and suggest to the clinician that therapy may not be warranted. The act of reporting a susceptibility profile may increase the chance that a patient will be treated. Avoidance of unnecessary antimicrobial therapy should lower costs and minimize pressure for the emergence of resistance. A further benefit of implementing our algorithm was the ability to determine a contamination rate that was incorporated into a quality assurance monitor with interventions aimed at optimizing the specimen collection procedure. Finally, the algorithm has provided opportunities to educate pathology residents about the significance of particular organisms when they are isolated from blood cultures and has increased residents' involvement in clinical microbiology laboratory activities. Laboratories that do not have pathology residents could utilize other qualified individuals to evaluate the significance of selected blood culture isolates.

Acknowledgments

This project received financial support from Organon Teknika.

We thank the following University of Iowa pathology residents for determining the clinical significance of blood culture isolates: Michelle Barry, Michele Cooley, Marc Dvoracek, Avina Kolareth, Julie Meredith, Paul Murray, Sanjai Nagendra, Charles Nicholson, Stephen Plumb, Rostislav Ranguelov, Daniel Schraith, Eric Stevens, Sergei Syrbu, Manaf Ubaidat, and Michael Woltman. We are indebted to the following technologists of the University of Iowa Clinical Microbiology Laboratory for incorporating the algorithm into their daily work: Linda Aker, Barry Buschelman, Tony Chavez, Carmen Clark, Sen Dinh, Carol Hayward, Jean Jennings, Mary Lindsey, Nancy Paulsen, Connie Quee, Lissa Sanford, Dennis Troy, and Carol Yang.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archer, G. L. 1985. Coagulase-negative staphylococci in blood cultures: the clinician's dilemma. Infect. Control 6:477-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates, D. W., L. Goldman, and T. H. Lee. 1991. Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization: the true consequences of false-positive results. JAMA 265:365-369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates, D. W., and T. H. Lee. 1992. Rapid classification of positive blood cultures: prospective validation of a multivariate algorithm. JAMA 267:1962-1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correa, L., and D. Pittet. 2000. Problems and solutions in hospital-acquired bacteraemia. J. Hosp. Infect. 46:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dominguez-de Villota, E., A. Algora-Weber, I. Millan, et al. 1987. Early evaluation of coagulase negative staphylococcus in blood samples of intensive care unit patients: a clinically uncertain judgement. Intensive Care Med. 13:390-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garner, J. S., W. R. Jarvis, T. G. Emori, et al. 1996. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, p. A1-A20. In R. N. Olmsted (ed.), APIC infection control and applied epidemiology: principles and practice. The C. V. Mosby Co., St. Louis, Mo.

- 7.John, J. F., and E. R. Bannister. 1984. Pseudobacteremia. Infect. Control 5:69-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirchhoff, L. V., and J. N. Sheagren. 1985. Epidemiology and clinical significance of blood cultures positive for coagulase-negative staphylococcus. Infect. Control 6:479-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacGregor, R. R., and H. N. Beaty. 1972. Evaluation of positive blood cultures: guidelines for early differentiation of contaminated from valid positive cultures. Arch. Intern. Med. 130:84-87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirrett, S., M. P. Weinstein, L. G. Reimer, et al. 2001. Relevance of the number of positive bottles in determining clinical significance of coagulase-negative staphylococci in blood cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3279-3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray, P. R., E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, et al. 1999. Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Ponce de Leon, S., and R. P. Wenzel. 1984. Hospital-acquired bloodstream infections with Staphylococcus epidermidis: review of 100 cases. Am. J. Med. 77:639-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ram, S., J. M. Mylotte, and M. Pisano. 1995. Rapid classification of positive blood cultures: validation and modification of a prediction model. J. Gen. Int. Med. 10:82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reimer, L. G., M. L. Wilson, and M. P. Weinstein. 1997. Update on detection of bacteremia and fungemia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:444-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegman-Igra, Y., and C. Ernst. 2000. Nosocomial bloodstream infections: are positive blood cultures misleading? Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:986.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Souvenir, D., D. E. Anderson, S. Palpant, et al. 1998. Blood cultures positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci: antisepsis, pseudobacteremia, and therapy of patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1923-1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein, M. P., M. L. Towns, S. M. Quartey, et al. 1997. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:584-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]