Abstract

Resolution of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) infection in pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients often leads to an asymptomatic carrier state characterized by a persistently elevated circulating EBV load that is 2 to 4 orders of magnitude greater than the load typical of healthy latently infected individuals. Elevated EBV loads in immunosuppressed individuals are associated with an increased risk for development of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease. We have performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies with peripheral blood B cells from carriers of persistent EBV loads in order to directly quantitate the number of EBV genomes per infected cell. Patients were assigned to two groups on the basis of the level of the persistent load (low-load carriers, 8 to 200 genomes/105 peripheral blood lymphocytes; high-load carriers, >200 genomes/105 peripheral blood lymphocytes). FISH analysis revealed that the low-load carriers predominantly had circulating virus-infected cells harboring one or two genome copies/cell. High-load carriers also had cells harboring one or two genome copies/cell; in addition, however, they carried a distinct population of cells with high numbers of viral genome copies. The increased viral loads correlated with an increase in the frequency of cells containing high numbers of viral genomes. We conclude that low-load carriers possess EBV-infected cells that are in a state similar to normal latency, whereas high-load carriers possess two populations of virus-positive B cells, one of which carries an increased number of viral genomes per cell and is not typical of normal latency.

Primary Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) infection in the immunocompetent individual invariably leads to a state in which the host becomes persistently infected with the virus. Latent infection is characterized by the presence of episomal viral genomes in the nuclei of resting memory B cells. Frequencies of 0.1 to 5 infected cells per 107 peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) are maintained in a stable state (16). By presorting of PBLs on the basis of cell surface markers, infected cells were detected among the CD19+, immunoglobulin D-negative, CD23−, CD80−, and Ki67− populations, consistent with the view that latent infection occurs in resting nonactivated memory B cells (2, 3, 25, 26). Recent studies have further defined the subset of peripheral latently infected B cells to the CD27+, CD5− B2 type of memory cell (15). The number of copies of viral episomes per cell has been estimated to be 2 to 5 (7, 16, 47). The polyadenylated RNA transcript encoded by latent membrane protein 2a (LMP2a) is the only viral gene whose expression is consistently detected in these latently infected cells by reverse transcriptase PCR (31).

Most studies of primary EBV infection focus on the infections of individuals diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis (IM). It is assumed that these symptomatic infections recapitulate the events of asymptomatic or unrecognized infections that result in most serologically detected conversions to the virus-positive latent state. Immunologic studies have demonstrated an increased number of activated natural killer (NK) cells and virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) during early stages of acute IM. By limiting the number of virus-infected cells, NK cells represent an important first line of defense (6, 27, 32), and the absence of these cells results in a more severe course of disease (13). The primary effector cells limiting the spread of virus later in the course of infection are the CTLs (33, 44). The induction of EBV-specific CTLs is directed toward epitopes derived from the EBV nuclear antigen 3 (EBNA3) family of proteins (EBNA3A, EBNA3B, and EBNA3C) and immediate-early and early proteins (17, 33, 44). T lymphocytosis accounts for the clinical mononucleosis associated with IM. The rapid expansion in the number of T cells abates as the acute infection subsides, but from the time of recovery onwards a constant immunosurveillance is necessary to detect and eliminate virus-immortalized cells.

Immunocompromised individuals (such as solid-organ transplant recipients) have difficulty mounting adequate specific immune responses to EBV infections and as a consequence are at risk of developing a virus-driven lymphoproliferative disorder. The condition is a heterogeneous array of diseases ranging from reactive polyclonal lymphoid hyperplasia to monoclonal malignant lymphoma. The origin of virus that causes posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) has occasionally been traced to the donor organ (40), although community-acquired infection may also be responsible for a significant number of cases of PTLD. Before the occurrence of symptomatic disease there is a period of approximately 2 to 6 weeks when the rising EBV load can be detected by PCR. PTLD is associated with a very high EBV load circulating in the peripheral blood: >1,000 copies of EBV genomes/105 PBLs in most cases and greater than 200 copies/105 PBLs with rare exceptions (4, 11, 12, 19, 21, 23, 29, 34, 36, 38, 39, 46). Resolution of EBV infection in pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients is often accompanied by a persistent high circulating EBV load 2 to 3 orders of magnitude higher than the viral load observed in latently infected immunocompetent individuals. The elevated load is likely attributable to the diminished immune response to EBV caused by the immunosuppressive therapy used to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ (48). Once the load carrier state is established, these patients maintain their loads for months to years without symptoms (10, 19, 45, 49, 51; unpublished observations). Similar to healthy, immunocompetent individuals, immunocompromised patients carry their loads in the memory B-cell compartment. Also, infected cells from patients with loads at the low end of the load carrier scale (whose loads are detectable but who have <200 copies/106 PBLs) have an LMP2a-positive phenotype typical of normal latency. LMP1 and LMP2a expression by infected cells from patients with loads at the high end of the load scale (>200 copies/106 PBLs) is consistently detected. This contrasts with the viral gene expression patterns for PTLD patients with high loads, which consists of the expression of all the EBNAs (EBNAs 1, 2, 3A, 3B, and 3C and EBNA-LP) as well as LMP1 and LMP2 (30).

In the study described in this paper we characterized the persistent carrier state using a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay that was developed to detect viral DNA in EBV-infected cells in the peripheral blood B cells. This has allowed us to directly visualize the viral genomes in the infected cells in the circulation and quantitate the number of genomes per cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

We have focused on the pediatric transplant population because we have multiple prospectively collected specimens from more than 190 patients in this group. A viral load was never detectable by quantitative PCR in only 65 of these patients (34.2%) (36). A low load (defined as detectable but <200 genome copies/105 lymphocytes for >2 months) has been detected in 69 patients (36.3%), and a high load (defined as >200 genome copies/105 lymphocytes for >2 months) has been detected in 35 patients (18.4%). The viral loads in the remaining 21 patients have fluctuated. Among the patients in this population, we initially identified 5 low-load carriers with no previous history of PTLD and 5 high-load carriers in which the 10 carriers were equally split with respect to whether their clinical histories included a recognized episode of PTLD, as well as 5 high-load carriers with a recent diagnosis of PTLD (Table 1). Peripheral blood cells from all patients were sorted for CD19+ cells. The cells were spun onto Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher) in a Cytospin apparatus; Namalwa cells, used as a control for in situ hybridization, were also spun onto microscope slides.

TABLE 1.

Summary of patient populationa

| Patient group and no. | History of PTLD | Sex | Age (mo) at treatment | Time of specimen collection (mo posttreatment) | EBV status pretransplant | Type of transplant | EBV load (no. of copies/105 PBLs) | No. of EBV genomes/low-copy-no. cellb | No. of EBV genomes/high-copy-no. cellc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic low-load carriers | |||||||||

| 1 | N | F | 147 | 63 | Pos | Liver-small bowel + BM | ND | 1-3 | ND |

| 2 | N | M | 117 | 5 | Pos | Small bowel | 20 | 1-2 | ND |

| 3 | N | M | Neg | Heart | 40 | 1-8 | 8, 10 | ||

| 4 | N | F | Neg | Heart | 80 | 1-4 | ND | ||

| 5 | N | F | 45 | 6 | Pos | Liver-small bowel | 100 | 1-3 | ND |

| Chronic high-load Carriers | |||||||||

| 6 | N | M | 48 | 46 | Neg | Heart | 200 | 1-3 | 79 |

| 7 | Y | M | 106 | Neg | Heart (second) | 400 | 1-6 | NQ | |

| 8 | N | M | 54 | 41 | Neg | Liver-small bowel | 500 | 1-5 | NQ |

| 9 | N | F | 40 | 36 | Neg | Heart | 500 | 1-8 | NQ |

| 10 | Y | F | Liver | >5000 | 1-3 | 17, 23 | |||

| PTLD patients | |||||||||

| 11 (18)d | Y | F | 31 | 14 | Neg | Bowel | 1-8 | NQ | |

| 12 (50) | Y | M | Bowel | 1-5 | 18, 21, 42 | ||||

| 13 (104) | Y | M | 111 | 90 | Pos | Liver-bowel | 1-9 | 16, 20, 24 | |

| 14 (65) | Y | F | 283 | 32 | Neg | Liver | 1-8 | 29, 30 | |

| 15 (15) | Y | M | 205 | 2 | Neg | Bowel | 1-9 | 27 |

Abbreviations: N, no; Y, yes; F, female; M, male; Pos, positive; Neg, negative; BM, bone marrow; ND, not detected; NQ, not quantified.

Range of genome numbers for all low-copy-number cells detected.

Number of genomes in representative high-copy-number cells.

The value in parentheses represent the test periods (in days).

Cell lines.

The B95-8 and B95-8CR cell lines (gifts of G. Miller, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.) are widely used for studies of immortalization and viral production. BJAB cells are EBV-negative B-cell lymphomas used as virus-negative controls and as carrier cells. Namalwa is a BL-cell line that contains two copies of the EBV genome integrated into the host genome and in which the cell-associated wild-type EBV genome copy number can be easily measured. All cell lines were maintained in 10% fetal calf serum in RPMI 1640 medium with penicillin and streptomycin with a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Quantitative-competitive (QC)-PCR of EBV loads in lymphocytes

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared from whole-blood specimens by centrifugation onto a Histopaque (Sigma) cushion. The cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and counted. The cell pellets were stored at −20°C until they were ready for PCR. To make lymphocyte lysates, 20 μl of PCR lysis buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1% Tween 20, 100 μg of proteinase K per ml) was added for every 105 lymphocytes. The lysates were incubated at 55°C for 1 h, boiled for 10 min to inactivate the proteinase K, and chilled on ice. Primers for the PCR target sequence in the EBV genome were designed with OLIGO software (National Biosciences).

Primers TP1Q5′ (AGGAACGTGAATCTAATGAAGA) and TP1Q3′ (GAGTCATCCCGTGGAGAGTA) amplify a 177-bp EBV sequence (exon 1) in the LMP2a gene. A competitor target was made by deleting 42 bp from a 177-bp EBV amplicon derived from the viral LMP2a exon 1 sequence. For each sample, four tubes containing 8, 40, 200, or 1,000 copies of the viral LMP2a competitor sequence, respectively, along with a lymphocyte or plasma lysate from the equivalent of 105 cells were subjected to 30 cycles of amplification (94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min). Each PCR mixture (50 μl) contained 20 pmol (each) of the 5′ and 3′ primers, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris (pH 9.0), 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.25 mM deoxynucleotides (Pharmacia). One unit of Amplitaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) was used in each reaction mixture. The PCR products were analyzed on 3% agarose gels containing 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA electrophoresis buffer and 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml.

The QC-PCR assay for EBV is used to quantitate viral loads in the range of 8 to 5,000 copies of viral DNA in 105 lymphocytes. Normal latent infection (0.01 to 0.1 copies/105 lymphocytes) is not detected by this protocol (36), and detectable levels of viral DNA reflect a viral genome burden at least 2 to 3 orders of magnitude above that during normal latency.

Magnetic bead separations.

Lymphocytes were positively sorted for CD19+ (B cells) by using Dynabeads M-450 CD19 (pan B cell marker). Ficoll-Hypaque lymphocyte preparations from patient blood specimens were mixed with Dynabeads at a concentration of 107 beads/ml, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 4°C. The positively selected cells were isolated with a magnet (Dynal MPC) and detached from the Dynabeads with DETACHaBEAD CD19.

Construction of DNA probe.

An EBV-specific probe was made from plasmid p1040, which contains a cloned BamHI WWYH fragment of EBV strain B95-8 DNA. The 14.7-kb fragment was cloned into a holding vector and linearized with HindIII, and double-stranded DNA probes of 250 to 300 bp were generated with the Prime-a-Gene Labeling System (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and labeled with digoxigenin-11 (DIG)-2′-dUTP (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) at room temperature overnight. The reaction was terminated by heating the mixture at 95 to 100°C for 2 min, and then the mixture was chilled in an ice bath, after which 20 mM EDTA was added. The labeling efficiency was measured, after which the reaction mixture was stored at −20°C and used directly in the in situ hybridization reaction.

Measurement of labeling efficiency.

The probe labeling efficiency was achieved by quantitating the amount of incorporated digoxigenin with the standard DIG detection kit and by the standard protocol (Roche Diagnostics). A 10-fold dilution series of the probe reaction mixture and a DIG-labeled control DNA of known concentration (Roche Diagnostics) were spotted onto nylon membranes. The nucleic acids were fixed on the membrane by cross-linking with UV light, and then the membranes were washed and blocked for 30 min at room temperature. The membranes were incubated in DIG-alkaline phosphatase (1:5,000; Roche Diagnostics) for 30 min at room temperature and were then washed to remove the unbound antibody. The membranes were than incubated in a solution of 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Roche Diagnostics) in the dark until the color precipitate was formed at a sufficient intensity. The reaction was stopped by washing the membranes in sterile water. The spot intensities of the reactions with labeled DNA were compared to those of the control DNA in order to quantitate the amount of DIG detected.

In situ hybridization.

FISH was done with freshly prepared PBLs from patient specimens that had been spun onto glass microscope slides with a Cytospin apparatus. B95-8CR, Namalwa, and BJAB cells were used as controls. The cells were fixed in methanol-acetic acid (3:1) for 15 min and aged in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M sodium chloride plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) at 37°C for 30 min and then dehydrated in a 70, 80, and 90% ethanol series (5 min at each concentration) and air dried. The slides were prewarmed to 50°C and denatured in 70% formamide-2× SSC at 70°C for 2 min and then immediately placed in a cold graded series of ethanol concentrations (70, 80, and 90% for 5 min at each concentration) and air dried. For each sample, 50 ng of probe, 5 μg of salmon sperm DNA, and 20 μg of yeast tRNA were suspended in formamide, dextran sulfate, and SSC so that the final concentrations were 50% formamide and 10% dextran sulfate in 1× SSC. The hybridization mixture was heated at 80°C for 10 min to denature the probe, followed by a preannealing at 37°C for 15 to 25 min. The slides were prewarmed at 37°C and were subsequently allowed to hybridize overnight at 37°C in a slide moat (Boekel Scientific, Festerville, Pa). Following hybridization the slides were washed first in 50% formamide-2× SSC for 30 min at 37°C and then in 2× SSC for 30 min at 37°C. RNase H treatment (8 U of RNase H/ml in RNase H reaction buffer) was done at 37°C for 1 h, and then the slides were washed twice in 2× SSC at room temperature for 15 min each time.

Immunological detection of bound EBV probe.

For immunological detection of the EBV probe, the blocked slides were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with anti-DIG-rhodamine Fab fragments (Roche Diagnostics). The slides were washed twice in 2× SSC at room temperature, dried, and mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting medium containing 4′,6′-diamidono-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories, Burmingdale Calif.). Positive signals are characterized as red dots within a 4′,6′-diamidono-2-phenylindole-counterstained (blue) nucleus, in which each specific signal represents one genome. Signals in close proximity to each other may appear as one; however, a doubling of the signal size is noted.

Photographs and quantitation of EBV genome copy number per cell.

The slides were examined with a Nikon E600 microscope equipped with a SPOTII charge-coupled device digital camera and, for higher resolution, an Olympus Provis microscope equipped with an Olympus Magnafire digital camera. The images were analyzed with Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, Westchester, Pa.) to quantitate the number of signals (genomes) per EBV-infected cell. A threshold for each gray-scale image was set, and regions were generated around each FISH-positive cell nucleus. The images were processed through a low-band-pass filter, and the counts were determined on the basis of the surface area of each positive signal. By using the signals acquired from a hybridized Namalwa control cell line, a surface area of 22 pixels represented one signal.

RESULTS

Specificity and sensitivity of FISH for EBV.

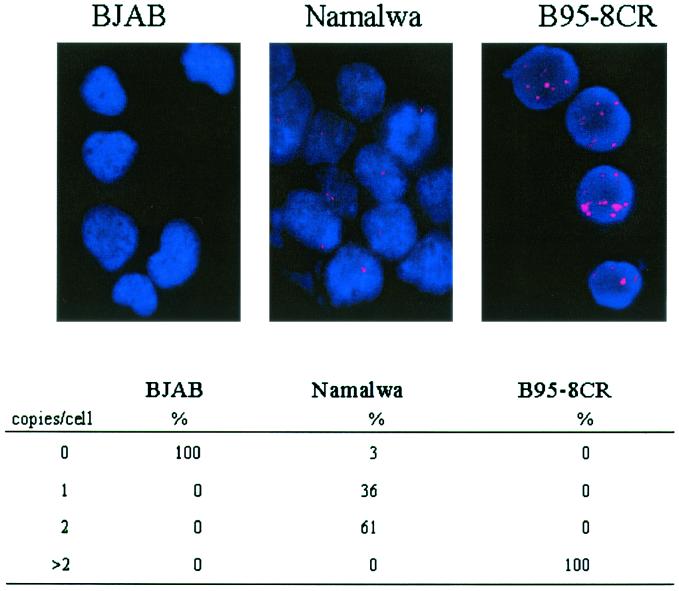

Before an analysis for the number of copies of the EBV genome in virus-infected cells in the peripheral blood could be performed, it was necessary to determine whether the probing techniques we were to use had the capability to reliably detect viral DNA. In situ hybridization assays were performed with virus-positive cell lines B95-8CR and Namalwa and virus-negative control cell line BJAB (Fig. 1). The B95-8CR cell line is a high-passage-number in vitro immortalized human adult B-cell line that carries an estimated 50 to 100 copies of the EBV genome per cell. As expected, in situ hybridization produced multiple spots in every nucleus of every cell. The B95-8CR cells shown in Fig. 1 had 83, 125, 228, and 59 spots per nucleus, as measured by automated counting (with Metamorph software), and these counts were typical of the large spread in counts detected within the population of these immortalized cells. Namalwa is a Burkitt's lymphoma cell line which has two copies of EBV DNA integrated head to head at a single site on chromosome 1p35 of the cellular genome (14, 20). For Namalwa cells, 97% of the nuclei scored positive for the presence of viral DNA. Sixty-one percent of the nuclei contained two hybridization spots, and 36% of the nuclei contained only one hybridization spot (Fig. 1). When two spots were resolved, they were always very close together, reflecting the close proximity of the sister chromatids carrying the integrated viral DNAs even in interphase nuclei.

FIG. 1.

FISH assay for EBV with control cell lines. In situ hybridization with the WWYH DNA probe for the detection of the EBV genome was performed with BJAB cells (negative control); Namalwa cells (positive control), which have two integrated genomes per cell; and B95-8CR cells (positive control), which have multiple copies of episomal DNA. The percentages of cells with different numbers of hybridization spots (copies of the EBV genome) per cell for each cell line are summarized below each photo.

How the expected two spots occasionally appeared as one can largely be accounted for by the relative orientations of the two integration sites when the nucleus is deposited randomly onto the slide. The hybridization patterns in the cell lines tested revealed that the probe was specific for viral DNA, had a sensitivity greater than 95%, and had the ability to resolve genomes that are closely packed within the nucleus. These results were similar to those that have previously been reported for in situ hybridization with Namalwa cells (20). The nuclei of the EBV-negative control BJAB cell line had no positive signals. The in situ hybridization therefore had 100% specificity and 97% sensitivity for the detection of cells with low numbers of EBV genome copies per cell that were anticipated in the peripheral blood specimens.

Viral genome distribution per cell in low-load carriers.

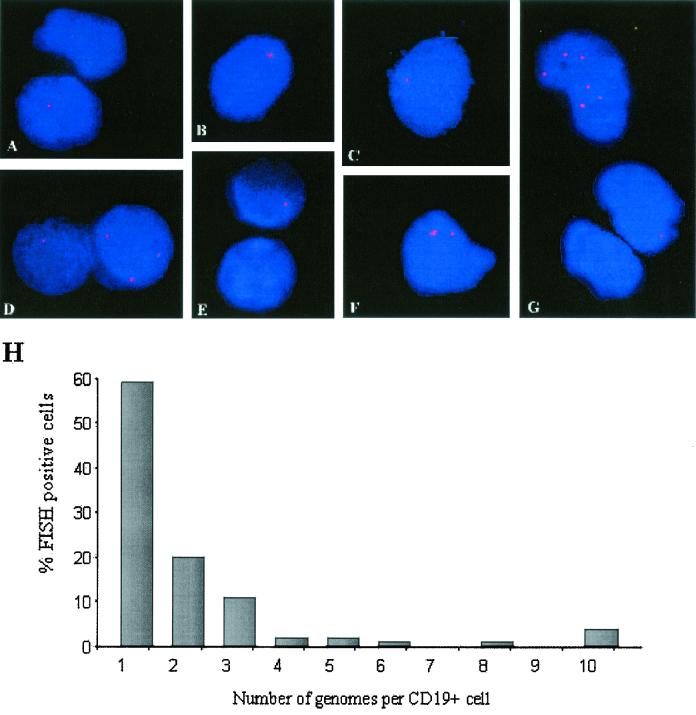

The FISH assay for EBV was performed with peripheral blood B cells purified from five stable asymptomatic low-load carriers (Table 1). Low-load carriers were defined as asymptomatic pediatric transplant recipients with EBV loads between 8 and 200 genomes per 105 PBLs. Virus-positive cells were detected in all patient specimens. These cells had low numbers of EBV genome copies per nucleus and most often had one or two detectable spots (Fig. 2A to G). For cells with two or more spots within the nucleus, the spots were randomly located with respect to each other, suggesting an unlinked relationship, in direct contrast to the pattern of close association of the viral genomes integrated in chromosome 1 in Namalwa cells (Fig. 1). The summed distributions of the numbers of genomes per infected cell for all low-load carriers showed that 59% of virus-positive cells had only one EBV genome per cell, while 20% carried two genomes per cell. Cells with 3 to 9 genomes comprised 17% of the virus-positive cell population, and cells with 10 or more genomes (4%) were detected on rare occasions. The results showed that in low-load carriers the genome burden per cell is characteristically low, usually less than five genomes per cell. Cells with low numbers of spots per cell were readily detected. The cell counts for hybridizations performed with samples from the same specimen on different slides were not significantly different, indicating that the technique is reproducible.

FIG. 2.

EBV genomes detected in peripheral blood B cells from chronic low-load carriers. Examples of cells with typical patterns of fluorescence were derived from patient 3 (D and G), patient 4 (A, B, E, and F), and patient 5 (C). All cells contained low numbers of genomes per cell. (H) Summary of the distribution of the number of genomes per cell for all persistent low-load carriers expressed as a percentage of all EBV-positive cells present.

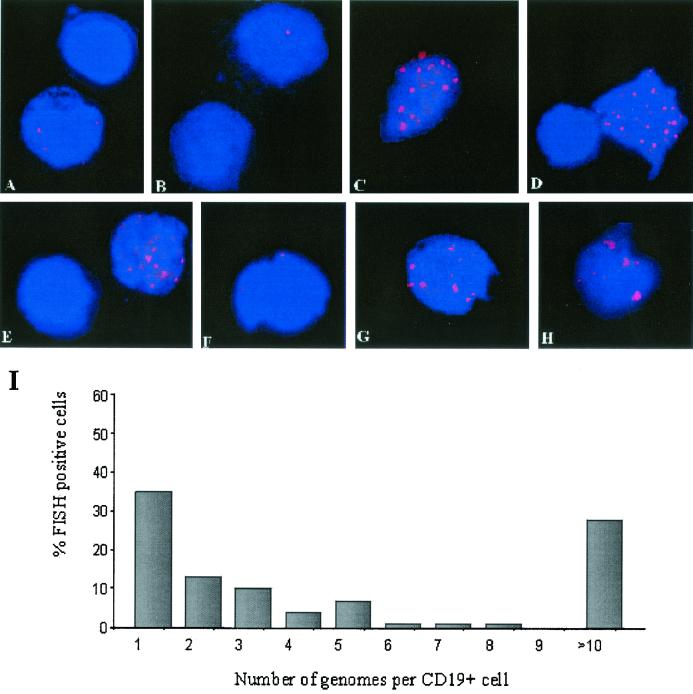

Viral genome distribution per cell in high-load carriers.

We have previously shown that a correlation can be made between the viral load and the pattern of latent viral gene expression in carriers with stable loads. Cells from high-load carriers, defined as asymptomatic pediatric transplant recipients with EBV loads greater than 200 genomes per 105 PBLs, expressed LMP1, in addition to LMP2, as determined by reverse transcriptase PCR. We analyzed the number of EBV genomes per cell among the virus-positive cells in the circulations of high-load carriers. Sixty-nine percent of all positive cells had low genome copy numbers (between one and five genomes per cell). Approximately half of these cells with low genome copy numbers carried only one genome per cell. When multiple spots were detected within a single nucleus, they were randomly scattered in respect to each other. These virus-positive cells with low genome copy numbers were similar in every respect to the cells with low genome copy numbers detected in the low-load carriers (Fig. 3A and F). In addition to these cells, 28% of the virus-positive cell population from high-load carriers had greater than 10 genomes per cell. Among these cells with high genome copy numbers, cells with very high genome copy numbers (20 to 30 copies per nucleus) were predominant. Since these types of cells were detected only in the high-load carriers, the presence of cells with very high genome copy numbers was a distinctive marker for this group (Fig. 3C to E and G to H). The fluorescent signals for the EBV genomes in the cells with high numbers of genome copies revealed a pattern distinct from that for the cells with low genome copy numbers. The genomes were unevenly distributed throughout the nuclei and were in close proximity, resulting in a poor resolution of the individual genomes. By normalizing the signal surface area with that of Namalwa cells by use of Metamorph imaging software, we were able to estimate the total number of genomes in these cells on the basis of the surface area of each group of genome clusters.

FIG. 3.

EBV genomes detected in peripheral blood B cells from chronic high-load carriers. Examples of cells with typical patterns of fluorescence were derived from patient 6 (E and H), patient 7 (B and G), and patient 10 (A, C, D, and F), which revealed a mixed population of cells with 5 or fewer genomes per cell and cells with 20 to 30 genomes per cell. (I) Summary of the distribution of the number of genomes per cell for persistent high-load carriers as a percentage of all EBV-positive cells present.

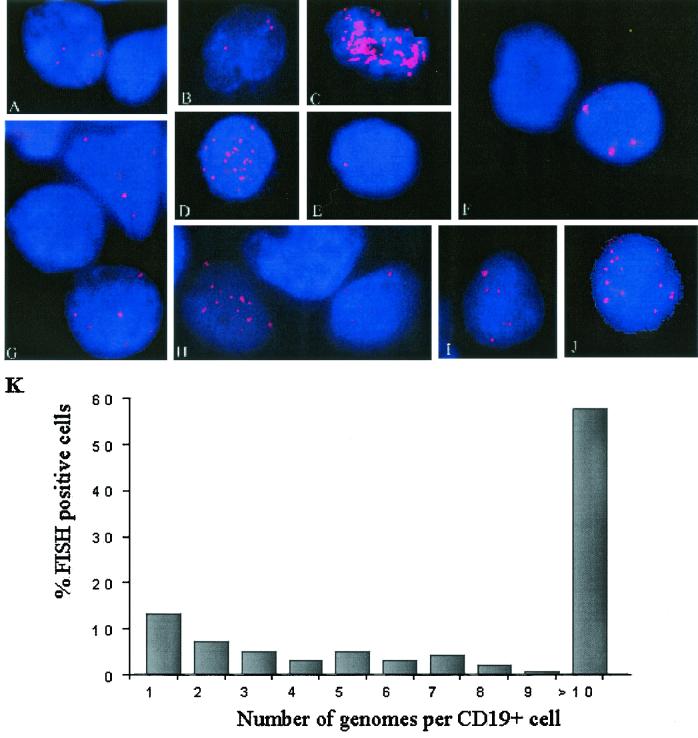

Viral genome distribution per cell in PTLD patients.

The viral loads usually reach a peak at or near the time of diagnosis of PTLD. We examined the distributions of the loads within the circulating B-cell compartments of PTLD patients using specimens obtained at times when the loads were close to the peak. The CD19+ cells in peripheral blood from five patients, collected from 1 to 3 months after a diagnosis of PTLD, during which time the peripheral viral load remained high, were subjected to hybridization for the detection of EBV DNA. Prospective specimens were collected one to two times per week in order to monitor changes in the viral loads and the distributions of the genome copy number per infected cell after the initiation of therapy. In situ hybridizations for EBV DNA in the blood lymphocytes showed a mixed cell population, with cells with high and low genome copy numbers detected (Fig. 4A to J). In all five PTLD patients the loads per infected cell were high, with greater than 10 copies per cell detected (Fig. 4C, D, H, and J). The population was predominantly composed of cells with between 20 and 30 genomes per cell. These cells represented approximately 57% of the EBV-positive cells (Fig. 4K). Approximately 13% of the virus-positive cells had only a single nuclear hybridization spot, and these were the next most common type of cell present. Twenty percent of the virus-positive cells carried two or genomes or less.

FIG. 4.

EBV genomes detected in peripheral blood B cells from patients with a recent diagnosis of PTLD. Examples of cells with typical patterns of fluorescence were derived from patient 12 (A to E), patient 13 (F to H), patient 14 (J), and patient 15 (I), which revealed a predominance of cells with high numbers of genome copies (20 to 30 genomes per cell). (K) Summary of the distribution of the number of genomes per cell for all PTLD patients as a percentage of all EBV-positive cells present.

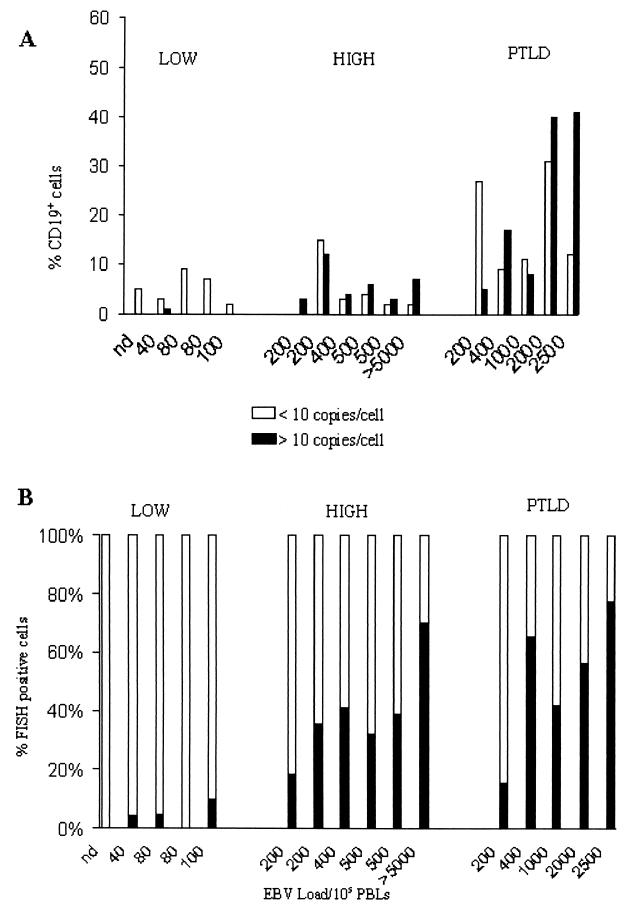

A comparison of the percentages of CD19+ cells which carried 1 to 10 EBV genomes per cell versus >10 EBV genomes per cell in five stable low-load carriers, six stable high-load carriers, and five PTLD patients revealed an overall increase in the number of EBV-infected cells as the viral load increased.

In low-load carriers, 2 to 13% of the cells in the B-cell population had viral loads of only 1 to 10 genomes per cell (Fig. 5A). The high-load carriers had a similar proportion of cells with low genome copy numbers as a fraction of the total B-cell population. One to 9% of the B cells in the high-load carriers had >10 copies of viral DNA per nucleus. These types of cells were absent or very rare in low-load carriers. There was little variation in the frequency of virus-positive cells from both populations of patients who were carriers of stable loads (mean for low-load carriers, 6%; mean for high-load carriers, 9%). The peripheral blood of PTLD patients had more infected cells with both high and low numbers of genome copies. The proportion of B cells with low numbers of genome copies (<10 viral genomes/cell) ranged from 9 to 31% of the total B-cell population, while the proportion of B cells with high numbers of genome copies (>10 viral genomes/cell) ranged from 5 to 41% of the total B-cell population.

FIG. 5.

(A) Percentage of CD19+ cells that were EBV positive in low- and high-load carriers as well as PTLD patients. Open bars, cells with 10 or fewer genomes per cell; closed bars, cells with greater than 10 genomes per cell. (B) Relative distributions of cells with low and high viral genome copy numbers in low- and high-load carriers, showing the predominance of cells with high copy numbers in patients with loads greater than 200 copies/105 PBLs. The ratios of the percentage of cells with high copy numbers to the percentage of cells with low copy numbers were 0.06, 0.7, and 1.2 for persistent low-load carriers, persistent high-load carriers, and PTLD patients, respectively.

The relative distributions of cells with low and high numbers of genome copies within the B-cell compartment were compared for five low-load carriers, six high-load carriers, and five PTLD patients (Fig. 5B). The ratio of cells with high numbers of copies to cells with low numbers of copies in low-load carriers was 0.05 and increased 10-fold (ratio, 0.6) in high-load carriers and was even higher (ratio, 1.23) in PTLD patients. Two pairs of patients in the high-load carrier group had identical EBV loads but carried different proportions of cells with high copy numbers. For the two patients with EBV loads of 200 copies/105 PBLs, one had twice as many cells with high copy numbers. This variation may correspond to a difference in the average number of EBV copies per nucleus in cells with high copy numbers or may be related to the mean load measured over time. The patient with a greater proportion of cells with high copy numbers had a mean EBV load of 400 copies/105 cells, while the patient with fewer cells with high copy numbers had a mean EBV load of 140 copies/105 cells and was not a high-load carrier 3 months prior to the time of specimen collection. There were no major differences in the proportion of cells with high copy numbers in the two patients with measured EBV loads of 500 copies/105 PBLs, and both patients carried high mean EBV loads 6 months prior to the test date. For the patient with the higher proportion of cells with high genome copy numbers, the mean load was 750 copies/105 PBLs, while for the patient with the lower proportion of cells with high copy numbers, the mean load was 350 copies/105 PBLs. The higher EBV loads in PTLD patients (200 to 2,500 copies/105 PBLs) corresponded to an increased number of EBV-positive cells in the B-cell compartment (mean, 40%; range, 19 to 72%) and a distinct shift toward more cells with high copy numbers. Overall, the results suggest that there are more similarities between PTLD patients and stable carriers of high loads than there are between stable carriers of high loads and stable carriers of low loads.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we have reported that a large fraction of pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients carry persistently elevated EBV loads. The elevated viral DNA loads seen in these patients appeared to be associated with latent virus because (i) no viral DNA was detected in the plasma fraction, (ii) immortalization or lytic replication genes were not expressed, and (iii) the load was restricted to the memory B-cell compartment (30, 35). Beyond the high loads, the only distinction between immunocompromised and healthy individuals was the expression of LMP1 RNA in all the carriers with loads greater than 200 copies/105 lymphocytes. RNA for the BZLF1 immediately-early gene product was not usually detected in either low- or high-load carriers. In the present study we have found that the presence of cells with high numbers of genome copies per cell, as detected by direct visualization of EBV genomes by in situ hybridization, is a second major distinction between low-load and high-load carriers. In situ hybridization of nonisotopic DNA for the detection of EBV genomes has been performed with tonsillar B cells, specimens of lesions from patients with PTLD, and specimens of other EBV-associated tumors, as well as lymphoblastoid cell lines (5, 8, 24, 37, 41, 43); but it has not previously been used with latently infected peripheral blood B cells. The Namalwa cell line provided a quantitative control for the sensitivity and the specificity of the assay. Namalwa cells carry two integrated genomes on chromosome 1, and direct visualization of control Namalwa cells showed that the sensitivity for detection of EBV DNA was greater than 97%. Because the viral DNA in Namalwa cells was confined to sister chromatids by covalent integration, the two integrations usually resolved as spots in close proximity. Approximately one-third of the time the hybridization signals merged into a single unresolvable signal, indicating that estimates of the number of spots in nuclei with large numbers of spots will result in underestimates of the number of genomes present.

Evidence from PCR-based studies suggests that there are three to five genome copies per latently infected lymphocyte in the circulations of healthy carriers and has shown that these viral genomes are episomal (2, 3, 7, 16, 47, 49). Among the cells from low-load carriers, the most commonly detected infected cell type was a cell with a single nuclear spot. We conclude that these cells have a single viral episome on the basis of a fluorescence intensity for the spot that was similar to but slightly lower than that in the Namalwa cell control on slides prepared at the same time with the same probe. When multiple spots were detected in cells from low-load carriers, the number was less than 10 and the localization of the spots within the nucleus was random. A nonrandom close association of nuclear spots might be an expected outcome of either replicative events (in which daughter viral episomes remain concatenated after replication at the S phase) or mitotic events (in which both newly replicated episomes remain associated with the same chromatid and are inherited by only one of the daughter cells). Our observations suggest that the episomes in these latently infected cells do not appear to be constrained by an association with each other or by attachment to the chromatids of a particular chromosome.

In the high-load carriers and PTLD patients, cells with low numbers of viral genomes were also detected. Just as with the cells from the low-load carriers, the localization of the spots within the nucleus was random when multiple spots were detected in these cells with low numbers of genome copies. In addition to cells with low numbers of copies, some cells also carried 20 to 30 genomes per cell. These cells with high numbers of genome copies appeared in the same memory B-cell pool as the cells with low numbers of genome copies (35) and were not obviously distinguishable in size or appearance from other cells in the fraction. There was an unevenness in the fluorescence intensities and sizes of the EBV genome spots within the nuclei of these cells, suggesting that within each nucleus there are areas where multiple genomes are in close proximity to each other. There was also a direct correlation between an increase in the frequency of these cells and an increase in the viral load, as measured by PCR (Fig. 5A). This pattern was also detected for patients with a recent diagnosis of PTLD. We are investigating whether this pattern might also be reflected in the longitudinal decreases in viral loads that occur as individual patients convalesce and the viral load stabilizes at lower levels. All of our low-load patients who previously had elevated loads, including PTLD patients, did not carry cells with high numbers of genome copies. This suggests that cells with high numbers of genome copies are not as long-lived as cells with low numbers of genome copies and, furthermore, that a stable recovery may involve the elimination of cells with high numbers of genome copies.

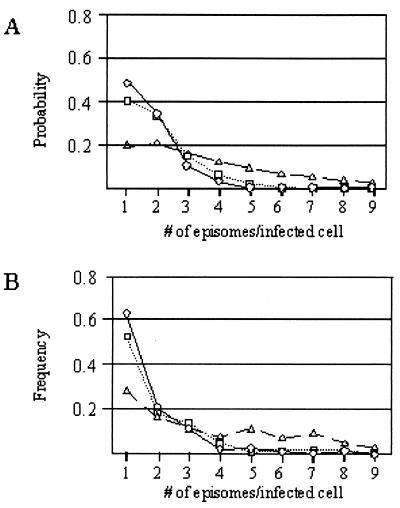

The viral load in low-load patients seems to be in a latent state. The distribution of the numbers of viral genomes in low-load carriers, as measured by direct counting, may be used to reconstruct a likely history of viral replication in latently infected cells from this patient population. For such a reconstruction, three key assumptions need to be made: (i) each cell becomes infected with one virus particle, (ii) the infected cells have equal replicative potentials, and (iii) the viral genome uses the dyad symmetry (DS) element of oriP to replicate only once per cell cycle and segregate randomly and efficiently to daughter cells. The last assumption is based on extensive studies of the properties of oriP-mediated plasmid replication (1, 50) This random assortment model for genome amplification has been used to compute the probability distribution of the number of viral episomes per cell after any given number of generations (Fig. 6A). The use of random assortment as the only mechanism for genome amplification requires all infected cells to undergo at least 10 generations to shift the predominant cell type to cells with more than one EBV genome copy per infected cell and to obtain cells with three or more genome copies per cell among a significant fraction of the infected cell population. Comparison of the calculated distributions with the measured frequencies of genomes in the cells from transplant patients with low genome copy numbers (Fig. 6B) allows one to draw several interesting conclusions. First, the latently infected cells with low copy numbers in the circulations of low- and high-load carriers have replicated after virus infection. This may be construed as direct evidence that latency can be established in cells that pass through the S phase after infection, a common assumption that lacks experimental support. Second, the cells with low numbers of genome copies from the low- and high-load carriers have replicated through an average of two to three generations after infection, but no more. This distribution of genomes per cell suggests that at least one S phase may actually be necessary before entry into the latent state. Third, the population of cells with low numbers of genome copies circulating in patients shortly after a diagnosis of PTLD appears to have undergone, on average, a higher number of generations (approximately 8 to 10) after infection.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of the distribution of the number of EBV episomes per cell predicted with a random assortment model and the observed distribution of EBV episomes per cell. (A) Expected distribution of the number of genomes per cell predicted with the random assortment model after cells become infected with a single virus particle and the viral episome replicates during cell proliferation. The plots represent the calculated distribution of the number of episomes per infected cell expected after B cells have proliferated for 2 (circles), 3 (squares), or 10 (triangles) generations. (B) Observed distribution of the number of EBV episomes per infected cell in the peripheral blood of low-load carriers (circles), high-load carriers (squares), and PTLD patients (triangles).

High-load carriers and PTLD patients have, in addition to cells with low numbers of genome copies, as discussed above, a population of cells that carry an average of 20 to 30 copies of the viral genome per cell. The random assortment model for genome amplification does not result in the accumulation of sufficiently large numbers of cells with high genome copy numbers within a reasonable number of generations to account for the presence of these cells with high numbers of genome copies in high-load carriers. A different model is needed to account for the replication history of cells with high numbers of viral genome copies. In vitro experiments involving virus infection of PBLs detected an approximately 20-fold increase in the genome copy number within 10 to 20 generations after infection (42). This expansion has been attributed to a short burst of viral genome replication occurring asynchronously relative to the cell cycle. Recent studies suggest that some cells replicate viral episomes by a DS-independent mechanism whose properties have not been clearly defined (18, 22, 28). One is tempted to speculate that the difference between cell populations with high and low numbers of genome copies arises because the cells with low numbers of copies have not undergone a burst of asynchronous viral episome replication, while the cells with high numbers of copies have. Since over time, as patients convalesce, the cells with low numbers of copies come to predominate, they may be longer lived. This could simply be related to the presence of low episome copy numbers, or it could be a consequence of a unique lineage history that excludes DS-independent replication. Further characterization of the cells with high genome copy numbers should reveal whether they are more prone to enter a period of immortalization-like cell proliferation and/or the lytic cycle than their counterparts with low genome copy numbers. Such properties might make them both easier to detect for normal immune surveillance and more dangerous for immunocompromised patients to have in their circulations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susanne Gollin for assistance in the development of the FISH protocol for the detection of EBV DNA. We also thank Martin Cottrell and Monica Bailey for dedicated technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, A. 1987. Replication of latent Epstein-Barr virus genomes in Raji cells. J. Virol. 61:1743-1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock, G. J., L. L. Decker, R. B. Freeman, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 1999. Epstein-Barr virus-infected resting memory B cells, not proliferating lymphoblasts, accumulate in the peripheral blood of immunosuppressed patients. J. Exp. Med. 190:567-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babcock, G. J., L. L. Decker, M. Volk, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1998. EBV persistence in memory B cells in vivo. Immunity 9:395-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buteau, C., and C. V. Paya. 2001. Clinical Usefulness of Epstein-Barr virus viral load in solid organ transplantation. Liver Transplant. 7:157-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coates, P., W. Mak, G. Slavin, and A. d'Ardenne. 1991. Detection of single copies of Epstein-Barr virus in paraffin wax sections by non-radioactive in situ hybridisation. J. Clin. Pathol. 44:487-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen, J. 1991. Epstein-Barr virus lymphoproliferative disease associated with acquired immunodeficiency. Medicine. 70:137-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decker, L. L., L. Klaman, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 1996. Detection of the latent form of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals. J. Virol. 70:3286-3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delsol, G., P. Brousset, S. Chittal, and F. Rigal-Huguet. 1992. Correlation of the expression of the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein and in situ hybribization with biotinylated BamHI-W probes in Hodgkin's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 140:247-253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gratama, J., M. Oosterveer, J. Lepoutre, J. van Rood, F. Zwaan, J. Vossen, J. Kapsenberg, D. Richel, G. Klein, and I. Ernberg. 1990. Serological and molecular studies of Epstein-Barr virus infection in allogenic marrow graft recipients. Transplantation 49:725-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green, M., T. V. Cacciarelli, G. V. Mazariegos, L. Sigurdsson, L. Qu, D. T. Rowe, and J. Reyes. 1998. Serial measurement of Epstein-Barr viral load in peripheral blood in pediatric liver transplant recipients during treatment for posttransplant lymphoproliferative diseases. Transplantation 66:1614-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green, M., M. G. Michaels, S. A. Webber, D. T. Rowe, and J. Reyes. 1999. The management of Epstein-Barr virus associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders in pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients. Pediatr. Transplant. 3:271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green, M., J. Reyes, S. Webber, M. G. Michaels, and D. Rowe. 1999. The role of viral load in the diagnosis, management and possible prevention of Epstein-Barr virus-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease following solid organ transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 4:292-296. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale, G., and H. Waldman. 1998. Risks of developing Epstein-Barr virus-related lymphoproliferative disorders after T-cell-depleted marrow transplants. Blood 91:3079-3083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson, A., S. Ripley, M. Heller, and E. Kieff. 1983. Chromosome site for Epstein-Barr virus DNA in a Burkitt tumor cell line and in lymphocytes growth transformed in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:1987-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph, A., G. Babcock, and D. A. Thorley-Lawson. 2000. EBV persistence involves strict selection of latently infected B cells. J. Immunol. 165:2975-2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan, G., E. Miyashita, B. Yang, G. Babcock, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1996. Is EBV persistence in vivo a model for B cell homeostasis? Immunity 5:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khanna, R., S. R. Burrows, and D. Moss. 1995. Immune regulation in Epstein-Barr virus-associated diseases. Microbiol. Rev. 59:387-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirchmaier, A. L., and B. Sugden. 1998. Rep∗: a viral element that can partially replace the origin of plasmid DNA synthesis of Epstein-Barr virus. J. Virol. 72:4657-4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kogan, D. L., M. Burroughs, S. Emre, T. Fishbein, A. Moscona, C. Ramson, and B. L. Schneider. 1999. Prospective longitudinal analysis of quantitative Epstein-Barr virus polymerase chain reaction in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Transplantation 67:1068-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrence, J., C. Villnave, and R Singer. 1988. Sensitive high resolution chromatin and chromosome mapping in situ: presence and orientation of two closely integrated copies of EBV in a lymphoma line. Cell 52:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Limaye, A. P., M.-L. Huang, E. E. Atienza, J. M. Ferrenberg, and L. Corey. 1999. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in sera from transplant recipients with lymphoproliferative disorders. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1113-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Little, R., and C. Schildkraut. 1995. Initiation of latent DNA replication in the Epstein-Barr virus genome can occur at sites other than the genetically defined origin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:2893-2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucas, K. G., R. L. Burton, S. E. Zimmerman, J. Wang, K. G. Cornetta, K. A. Robertson, C. H. Lee, and D. J. Emanuel. 1998. Semiquantitative Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) polymerase chain reaction for the determination of patients at risk for EBV-induced lymphoproliferative disease after stem cell transplantation. Blood 91:3654-3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mabruk, M., S. Flint, D. Coleman, O. Shiels, M. Toner, and G. Atkins. 1996. A rapid microwave-in situ hybridization method for the definitive diagnosis of oral hairy leukoplakia: comparison with immunohistochemistry. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 25:170-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyashita, E., B. Yang, G. Babcock, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1997. Identification of the site of Epstein-Barr persistence in vivo as a resting B cell. J. Virol. 71:4882-4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyashita, E., B. Yang, K. Lam, D. Crawford, and D. Thorley-Lawson. 1995. A novel form of Epstein-Barr virus latency in normal B cells in vivo. Cell 80:593-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nalesnik, M., and T. Starzl. 1994. Epstein-Barr virus, infectious mononucleosis, and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Transplant. Sci. 4:61-79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norio, P., C. L. Schildkraut, and J. L. Yates. 2000. Initiation of DNA replication within oriP is dispensable for stable replication of the latent Epstein-Barr virus chromosome after infection of established cell lines. J. Virol. 74:8563-8574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohga, S., E. Kubo, A. Nomura, and N. Suga. 2001. Quantitative monitoring of circulating Epstein-Barr virus DNA for predicting the development of post transplant lymphoproliferative disease. Int. J. Hematol. 73:323-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qu, L., M. Green, S. Webber, J. Reyes, D. Ellis, and D. Rowe. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in the peripheral blood of transplant recipients with chronic circulating viral loads. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1013-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qu, L., and D. T. Rowe. 1992. Epstein-Barr virus latent gene expression in uncultured peripheral blood lymphocytes. J. Virol. 66:3715-3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rickinson, A., and E. Kieff. 1996. Epstein-Barr virus, p. 2397-2436. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 33.Rickinson, A., and D. Moss. 1997. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:405-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riddler, S. A., B. K. Breining, and J. C. McKnight. 1994. Increased levels of circulating Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected lymphocytes and decreased EBV nuclear antigen antibody responses are associated with the development of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in solid-organ transplant recipients. Blood 84:1972-1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose, C., M. Green, S. Webber, D. Ellis, J. Reyes, and D. Rowe. 2001. Pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients carry chronic loads of Epstein-Barr virus exclusively in the immunoglobulin D-negative B-cell compartment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1407-1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe, D. T., L. Qu, J. Reyes, N. Jabbour, E. Yunis, P. Putnam, S. Todo, and M. Green. 1997. Use of quantitative competitive PCR to measure Epstein-Barr virus genome load in the peripheral blood of pediatric transplant patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. J. Clin. Microbol. 35:1612-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saeki, K., K. Mishima, K. Horiuchi, S. Hirota, S. Nomura, Y. Kitamura, and K. Aozasa. 1993. Detection of low copy numbers of Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization using nonradioisotopic probes prepared by the polymerase chain reaction. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 2:108-115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapiro, R., M. Nalesnik, J. McCauley, S. Fedorek, M. L. Jordan, V. P. Scantlebury, A. Jain, C. Vivas, D. Ellis, S. Lombardozzi-Lane, P. Randhawa, J. Johnston, T. R. Hakala, R. L. Simmons, J. J. Fung, and T. E. Starzl. 1999. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in adult and pediatric renal transplant patients receiving tacrolimus-based immunosuppression. Transplantation 68:1851-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens, S. J., E. A. Verchuuren, I. Pronk, and M. C. Harmsen. 2001. Frequent monitoring of Epstein-Barr virus DNA load in unfractionated whole blood is essential for the early detection of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in high risk patients. Blood 97:1165-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strazzabosco, M., E. D'Andrea, A. Faccioli, A. Del Mistro, M. Montagna, A. Poletti, D. Neri, R. Merenda, L. Bonaldi, G. Gerunda, C. Menin, R. Iemmolo, and B. Corneo. 1997. Epstein-Barr virus-associated post-transplant lympho-proliferative disease of donor origin in liver transplant. J. Hepatol. 26:926-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strickler, J., M. Rooney, E. d'Amore, C. Copenhaver, and P. Roche. 1993. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization with a commercially available biotinylated oligonucleotide probe. Mod. Pathol. 6:208-211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugden, B., M. Phelps, and J. Domoradzki. 1979. Epstein-Barr virus DNA is amplified in transformed lymphocytes. J. Virol. 31:590-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szeles, A., K. Falk, S. Imreh, and G. Klein. 1999. Visualization of alternative Epstein-Barr virus expression programs by fluorescent in situ hybridization at the cell level. J. Virol. 73:5064-5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan, L. C., N. Gudgeon, N. E. Annels, P. Hansasuta, C. A. O'Callaghan, S. Rowland-Jones, A. J. McMichael, A. B. Rickinson, and M. F. Callan. 1999. A re-evaluation of the frequency of CD8+ T cells specific for EBV in healthy virus carriers. J. Immunol. 162:1827-1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thorley-Lawson, D., and G. Babcock. 1999. A model for persistent infection with Epstein-Barr virus: the stealth virus of human B cells. Life Sci. 65:1433-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vajro, P., S. Lucariello, S. Migliarello, and B. Gridelli. 2000. Predictive value of Epstein-Barr virus genome copy number and BZLF1 expression in blood lymphocytes of transplant recipients at risk for lymphoproliferative disease J. Infect. Dis. 181:2050-2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner, H., G. Bein, A. Bitsch, and H. Kirchner. 1992. Detection and quantitation of latently infected B lymphocytes in Epstein-Barr virus-seropositive, healthy individuals by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2826-2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Webber, S., and M. Green. 2000. Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: advances in diagnosis, prevention and management in children. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 11:145-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang, J., Q. Tao, I. W. Flinn, P. G. Murray, L. E. Post, H. Ma, S. Piantadosi, M. A. Caligiuri, and R. F. Ambinder. 2000. Characterization of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells in patients with posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease: disappearance after rituximab therapy does not predict clinical response. Blood 96:4055-4063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yates, J., N. Warren, and B. Sugden. 1985. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature 313:812-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zangwill, S., D. Hsu, and M. Kickuk. 1998. Incidence and outcome of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection and lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric heart transplant recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 17:1161-1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]