Summary

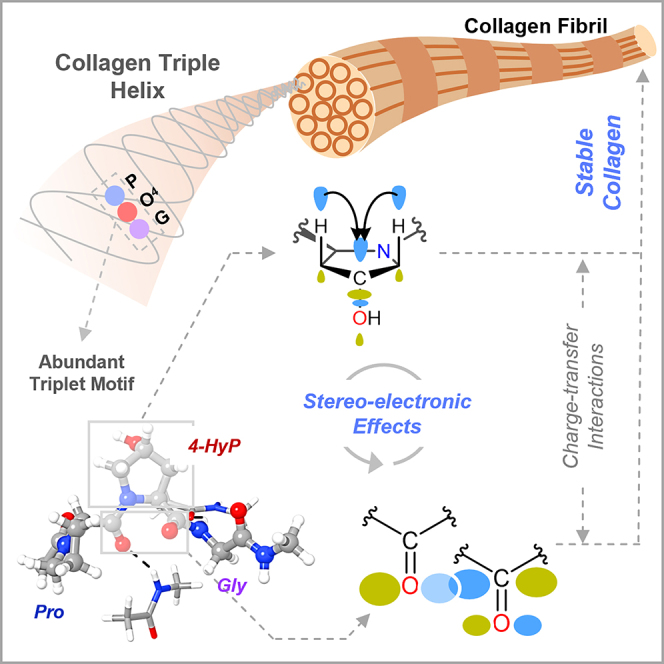

Prolyl-4-hydroxylation is an ancient evolutionarily conserved post-translational modification (PTM) critical for both structural and regulatory functions in multicellular life forms. This PTM plays a pivotal role in stabilizing collagen’s triple helix by influencing the puckering of the pyrrolidine ring. The elegant interplay between ring pucker, torsional angles, peptide bond isomerization, and charge-transfer interactions (O···C=O n→π∗ and σ→σ∗) attaining the helical stability remains underappreciated. Using density functional theory calibrated against gold standard ab initio methods, we analyzed a physiologically relevant collagenous peptide proline-4-hydroxyproline-glycine (PO4G) to establish the correlation between stereo-electronic effects due to prolyl-4-hydroxylation. Our results show that 4(R)-hydroxylation promotes an exo ring pucker, optimizing main-chain torsional angles for a stable trans peptide bond and maximizing the n→π∗ interaction (En→π∗ = 0.9 kcal/mol) by tuning Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory, and maximizes σ→σ∗ interactions between axial C–H σ-electrons and C–OH∗ orbitals of the pyrrolidine ring. This study reveals the intricate stereo-electronic effects driving collagen’s structural stability.

Subject area: Physical chemistry, Quantum chemistry, Quantum chemical calculations

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Deciphered the stereoelectronic effects of prolyl-4-hydroxylation in collagen

-

•

Prolyl-4-hydroxylation-mediated exo ring pucker tunes Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory

-

•

4-HyP enhances the peptide backbone stabilization through n→π∗ interaction

-

•

Decoded elegant interplay between geometry, bond isomerization, and charge-transfer

Physical chemistry; Quantum chemistry; Quantum chemical calculations

Introduction

Evolutionarily conserved post-translational modifications (PTMs) of collagens have been instrumental in regulating the cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions and maintaining the structural integrity of the ECM.1,2 Type I collagen is the most abundant ECM protein of multicellular vertebrate life forms, including humans.3 The trimeric collagen I protein comprises three polypeptide chains, which can be homotrimer and/or heterotrimer, each conforming to the left-handed helical structure similar to the polyproline type II (PPII) helix.3,4 The three polypeptide chains, arranged in one amino acid staggered manner, wrap around the central fibril axis to construct a right-handed triple helical structure (Figure 1A). Each helical chain of type I collagen is predominantly arranged by the repetitive triplet –Xaa–Yaa–Gly (XYG).3,4,5 The highly abundant prolyl-4-hydroxylation PTM, catalyzed by prolyl-4-hydroxylases, is prevalent in the Yaa position of the collagenous triplet.5 Specifically, the amino acid hydrolysis of fibrillar and non-fibrillar collagen chains from human tissue sources showed that approximately 38% of Yaa amino acids are 4-hydroxyproline (4-HyP).6 The occurrence of 4-HyP in the repetitive triplet in the form of –Xaa–4-HyP–Gly– (XO4G) provides the foundational framework to achieve the typical helical structural attainment of type I collagen and its thermal stability (Figure 1A).7 Commonly, proline (Pro) occupies the Xaa position to construct the most abundant triplet in collagen I, –Pro–4-HyP–Gly– (PO4G).5,6

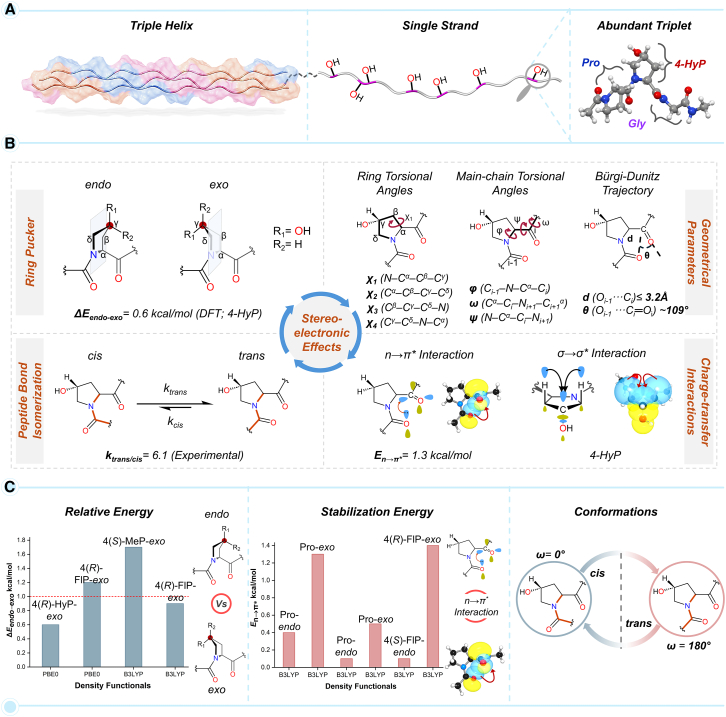

Figure 1.

Stereoelectronic effects in collagen due to 4-HyP and quantum chemical studies of stabilization energies

(A) The triple helical structure of collagen, a single strand of collagen, and the abundant triplet (–Xaa–4-HyP–Gly–). The sections in pink represent the –Xaa–4-HyP–Gly– triplet motif in a single strand in the triple helical domain.

(B) The stereoelectronic parameters associated with 4-HyP responsible for collagenous helical stability; pyrrolidine ring pucker, key geometrical parameters (ring (χ) and main-chain (ϕ, ψ, and ω) torsional angles and Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory), peptide bond conformations, and charge-transfer (n→π∗ and σ→σ∗) interactions.

(C) An illustration of the reported ΔEendo–exo (kcal/mol) and En→π∗ (kcal/mol) values for single amino acid conformers using DFT methods.

The structural integrity of the triplet PO4G repeats is maintained by different highly synchronized stereoelectronic parameters that involve pyrrolidine ring puckers in prolines, main-chain torsional angles (ϕ, ψ, and ω), charge transfer interactions, and peptide bond cis/trans conformation (Figure 1B).8 The post-translationally modified 4-HyP in PO4G attains a Cγ-exo ring pucker owing to the hydroxylation at the C4 or γ-carbon of the pyrrolidine ring. The resulting exo ring pucker is 0.6 kcal/mol (ΔEendo–exo) more stable over the endo ring pucker.9 This stabilization effect has been attributed to the “gauche” effect facilitated by a charge-transfer interaction (σ→σ∗) between the σ-bonding electrons of Cβ–Hax/Cδ–Hax bonds and σ-antibonding (σ∗) orbital of Cγ–OH (Figure 1B).9 To gain a deeper understanding of this effect, more electronegative groups like –F, –Cl, and –SH were incorporated in synthetic peptidomimetics at the Cγ position. The electronegative groups were found to enhance the charge-transfer interaction, further stabilizing the exo ring pucker.8,10 Interestingly, the fluoroproline 4(R)-FlP-exo single amino acid peptidomimetics was shown to possess the highest Eσ→σ∗ value among all the four conformers.8 However, electronic structure analysis for the four conformers due to the naturally occurring Cγ–OH hydroxylation in 4-HyP in collagen chains, i.e., 4(R)-HyP-exo, 4(R)-HyP-endo, 4(S)-HyP-exo, and 4(S)-HyP-endo (Figure 1B) has not been reported thus far. Taken together, the positional preferences of prolines in collagen triple helix have led to the propensity-based hypothesis suggesting that prolyl-4-hydroxylation at the Yaa position restricts the conformational flexibility of proline adopting the Cγ-exo pucker Consequently, Pro and 4-HyP pre-organize a single strand to attain a folded triple helix.7,11 The restriction in conformational flexibility of the pyrrolidine ring would certainly imply that the ring torsional angles (χ1, χ2, χ3, χ4) would be restricted to a particular value, which in turn would dictate the main-chain torsional angles (ϕ, ψ, and ω) (Figure 1B).12 Indeed, as revealed by crystallography studies, the angles χ1 and ϕ are required to attain approximately −20° and −60°, respectively, for the Cγ-exo pucker for 4-hydroxyproline in the PO4G triplet.7,13 More importantly, the main-chain torsional angle ω with a value of ∼180° in PO4G triplet significantly contributes to the collagenous helical stability by enforcing all peptide bonds to their trans conformation (Figure 1B).3,14 In this trans peptide bond conformation, two carbonyl groups are orientated in such a way that the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory (Figure 1B), distance from Oi–1 to Ci (d), and the angle formed between Oi–1 … Ci = O (θ), attain optimal values of ∼3.2 Å and ∼109°, respectively.15,16,17 This specific orientation of the carbonyl groups promotes a crucial charge-transfer interaction (n→π∗) between the donor lone-pair electron (n) of one carbonyl oxygen (–C=Oi–1) and the acceptor anti-bonding C=O π-orbital (π∗) of another carbonyl moiety (–C=Oi) (Figure 1B).17 Such n→π∗ interactions are associated with a typical stabilization energy of En→π∗ ∼ 0.3–0.7 kcal/mol in proteins.17 It is important to mention here that the n→π∗ interaction has made the acyl groups of the helical backbone resistant to acid hydrolysis, which has preserved collagen through evolution.2 Remarkably, the n→π∗ interaction is larger in 4(R)-HyP-exo as compared to the 4(R)-HyP-endo conformer with an En→π∗ value of 1.3 kcal/mol.18 In this line, an estimation of the En→π∗ values for 4(S)-HyP-exo and 4(S)-HyP-endo, along with their 4(R) diastereoisomers, would provide valuable insights into explaining the naturally occurring conformer −4(R)-HyP– in collagen chains.

The above discussion suggests that the crucial stereoelectronic effects involving pyrrolidine ring puckers, torsional angles (ϕ, ψ, and ω), peptide bond cis/trans conformation, and charge-transfer interactions (n→π∗ and σ→σ∗) operate in a highly orchestrated manner to provide the overall stability of the collagen chain and triple helix. However, the role of the elegant interplay between these stereoelectronic effects in dictating the collagen helical stability has remained underappreciated since all previous reports involve a single amino acid model for quantum chemical investigations.8,9,19,20,21,22 To appropriately decipher the correlation between different stereoelectronic effects due to prolyl-4-hydroxylation stabilizing the collagenous helicity, a physiologically relevant collagenous tripeptide would be essential. Moreover, one of the most critical stabilizing factors to helical stability originating from the Cγ-exo ring pucker, ΔEendo–exo ranges between ∼0.6 and ∼1.7 kcal/mol (Figure 1C),5,9,23 which is close to the accuracy limit (∼2–3 kcal/mol)24 of modern density functional theory (DFT) methods. This necessitates rigorous calibration of the chosen DFT methods against the gold-standard ab initio quantum chemical methods, which offer significantly higher chemical accuracy, typically within ∼1 kcal/mol.25,26 In this pursuit of understanding the critical role of stereoelectronic effects in collagenous helical stability, we employed DFT methods–calibrated against ab initio quantum chemical methods–on a physiologically relevant collagenous peptide (PO4G). Specifically, a wide range of DFT methods involving 24 DFT functionals have been calibrated against the gold standard ab initio method, domain-based pair natural orbital coupled cluster methods with single, double, and perturbative triples corrections (DLPNO-CCSD(T)). Subsequently, the most optimal DFT method has been used to obtain the stereoelectronic parameters, ΔEendo–exo, En→π∗, and Eσ→σ∗ with the physiologically relevant collagenous peptide. Overall, this study has comprehensively delineated the electronic level understanding of the role of prolyl-4-hydroxylation in the helical collagenous structural attainment that is the fundamental requirement for all vertebrate life forms.

Results and discussion

Calibration of DFT functionals against ab initio methods for relative energy to study the stereoelectronic effects of collagen prolyl-4-hydroxylation

Collagen helical structure and stability are critically dependent on the 4-HyP ring conformer, which makes the relative energy between endo and exo ring pucker (ΔEendo–exo) one of the most crucial deterministic parameters in structural stability. Considering the low magnitude of ΔEendo–exo, typically between 1 and 2 kcal/mol, it is of utmost importance to ensure the accuracy of the chosen DFT method for the investigation of the stereoelectronic effects of prolyl-4-hydroxylation. In this quest, we begin with the direct comparison of the relative energy due to pyrrolidine ring conformations, ΔEendo–exo for the 4(R)-HyP-endo relative to the natural 4(R)-HyP-exo conformer, estimated by DLPNO-CCSD(T) and 2nd-order Møller–Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) methods (Figure S1). Pleasingly, the ΔEendo–exo value of 1.7 kcal/mol predicted at the MP2 level was found to be nearly identical to that of the gold-standard ab initio method, DLPNO-CCSD(T) producing a ΔEendo–exo value of 1.8 kcal/mol. This result suggests that the geometry and relative energy at the MP2 level can be used as the benchmark for further calibration of the DFT methods. Figure 2B presents a direct comparison of the MP2-predicted ΔEendo–exo values with twenty-four DFT functionals. As it appears, the DFT functionals, CAM-B3LYP, revTPSS, M06L, MN15L, M052X, M06, M062X, MN15, B2PLYP, DSD-PBEP86, and mPW2PLYP, show closest match with the MP2-estimated relative energies. Moreover, these DFT functionals also predict the ΔEendo–exo relative energy around or slightly above the chemical accuracy limit of ∼1 kcal/mol (Figure 2B). Thus, this result provides an initial screening of the DFT methods against the ab initio MP2, and thereby, the DLPNO-CCSD(T) method.

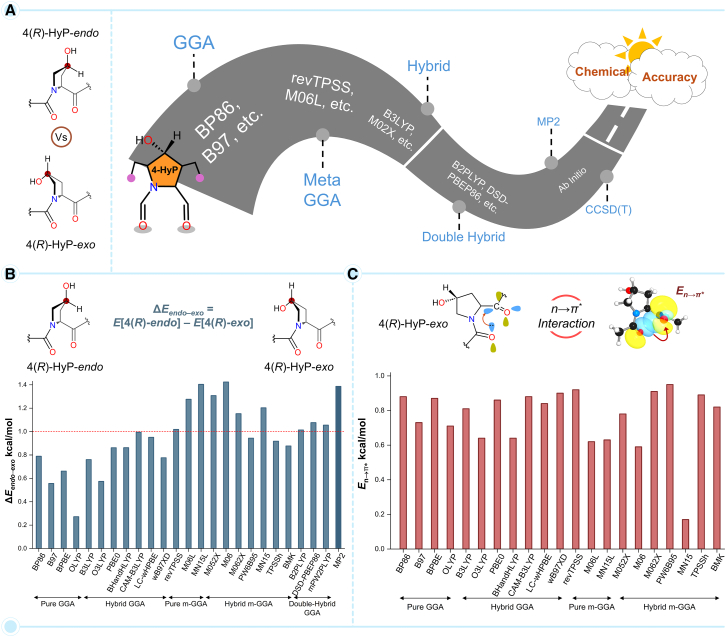

Figure 2.

Calibration of DFT methods against ab initio methods

(A) An illustration of the category of DFT methods that are calibrated against ab initio MP2 and the DLPNO-CCSD(T) methods using the relative energy ΔEendo–exo = E[4(R)-endo] – E[4(R)-exo] (kcal/mol) for 4-HyP conformers as the parameter.

(B) Calibration of twenty-four DFT functionals including, pure GGA, hybrid GGA, pure meta-GGA, hybrid meta-GGA, and double hybrid functionals against the ab initio MP2 method. See also Figure S2 and Table S1.

(C) Estimation of the interaction energy due to the n→π∗ charge-transfer (En→π∗) for the natural conformer of 4-HyP, i.e., 4(R)-HyP-exo at different DFT levels. See also Figure S5 and Table S4.

The DFT functional calibration study was further extended to the diastereomer of the 4(R)-HyP, i.e., 4(S)-HyP. Both the endo and exo conformer of the 4(S)-HyP, i.e., 4(S)-HyP-endo and 4(S)-HyP-exo were subjected to the DFT functional calibration study. The relative electronic energies (ΔE) of all the non-natural HyP conformers, i.e., 4(S)-HyP-endo (ΔEendo–exo = E[4(S)-endo] – E[4(R)-exo]), 4(S)-HyP-exo (ΔEexo–exo = E[4(S)-exo] – E[4(R)-exo]), and 4(R)-HyP-endo (ΔEendo–exo = E[4(R)-endo] – E[4(R)-exo]) together relative to the natural 4(R)-HyP-exo conformer at the DFT and MP2 levels are presented in the supplemental information (Figure S2; Table S1). A close inspection of the relative energy comparison reveals DFT functionals, revTPSS, M06L, M052X, M06, M062X, B2PLYP, DSD-PBEP86, and mPW2PLYP, unanimously predict ΔEendo–exo close to the ab initio MP2 values and above the chemical accuracy limit of ∼1 kcal/mol. The DFT-M06 functional predicts a ΔEendo–exo value of 1.4 kcal/mol for the 4(R)-HyP conformer, which is the closest to the corresponding MP2 value (Figures 2B and S2). Based on the data presented in Figures 2B and S2, the calibrated DFT functionals having closer ΔEendo–exo values to MP2 can be arranged in the decreasing order of their accuracy in predicting the relative energies as M06 > M052X ≈ M06L > M062X > DSD-PBEP86 ≈ mPW2PLYP > B2PLYP ≈ revTPSS. Mostly, the hybrid DFT functionals predict relative energy values that are closer to the ab initio methods. In this context, it should be noted that the results obtained from the hybrid DFT methods significantly depend on the amount of the Hartree-Fock exchange (%HF-X) correlation that constitutes the functional. Keeping this in mind, we evaluated the role of %HF-X in predicting the ΔE values for all non-natural conformers, i.e., 4(S)-HyP-endo (ΔEendo–exo), 4(S)-HyP-exo (ΔEexo–exo), and 4(R)-HyP-endo (ΔEendo–exo) relative to the natural 4(R)-HyP-exo conformer (Figure S3; Table S2). Specifically, twelve DFT functionals with varying %HF-X between 0 and 56% were calibrated against the MP2 level. Among the previously screened functionals, only five DFT functionals satisfy the chemical accuracy mark, as shown with the ΔEendo–exo values of 4(R)-HyP-endo (Figure S3). Also, in this case, the ΔEendo–exo value of 1.4 kcal/mol predicted by the M06 functional (27% HF-X) is the closest to the MP2 value. In comparison, the M052X functional with the highest amount of %HF-X of 56% predicts a close value of 1.3 kcal/mol. Therefore, the DFT functionals that predict the ΔEendo–exo values to the chemical accuracy mark can be further screened and arranged in the decreasing order of accuracy as, M06 > M052X > M062X > DSD-PBEP86 > B2PLYP.

Evaluation of n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction energy, En→π∗ at different DFT levels to select the optimal DFT method for studying the electronic effect of collagen prolyl-4-hydroxylation

In this section, we analyzed the second-order perturbation energy (E(2)) obtained from the natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis. The carbonyl groups (–C=O) in collagen, as in other proteins, play a vital role in maintaining overall structural stability.27,28 The vacant π∗ orbital of the carbonyl group readily interacts with nucleophiles, such as the lone pair (n) of adjacent oxygen atoms. The underlying mechanism of this interaction can be understood as a charge-transfer process between the “donor” oxygen lone-pair orbital (n) and the “acceptor” C=O π∗ orbital. The resulting orbital mixing between n and π∗ exerts a stabilizing effect on the overall molecular framework. In the context of protein structure, the stabilizing n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction is significantly influenced by the distance between the donor oxygen of one C=O and the acceptor carbon of the other C=O moiety. The energy () associated with the donor (i) → acceptor (j) charge-transfer interaction can be estimated using the following equation and obtained through NBO analysis.29,30

Here, is the effective orbital Hamiltonian (Kohn-Sham operator in DFT) and , are the respective orbital energies of “donor” and “acceptor” NBOs. Using perturbation theory, the strength of the charge-transfer interaction can be approximately estimated as

Therefore, we used the calculated energy , denoted as in the manuscript, to estimate the strength of charge-transfer interactions in collagenous tripeptides. This stabilization energy due to n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction has been denoted as En→π∗ throughout our discussion. The natural HyP conformer, i.e., 4(R)-HyP-exo, was subjected to the En→π∗ analysis at different DFT levels (Figure 2C). Since no ab inito method could be used as a reference for the calculation of the En→π∗ value, we focused on the primarily screened density functionals that were calibrated against ab initio methods based on the ΔEendo–exo values. For completion, the En→π∗ values obtained at the other pure-GGA, hybrid-GGA, pure meta-GGA, and hybrid meta-GGA DFT functionals are also presented together. However, the double-hybrid GGA functionals could not be used as they are not yet implemented in the NBO 7.0 program. Because En→π∗ quantifies the stabilization effect due to charge-transfer interaction and a higher value signifies greater stabilization, the DFT functional that gives a higher En→π∗ can be selected as the most suitable one among the selected functionals. Figure 2C presents the En→π∗ values for the 4(R)-HyP-exo conformer obtained from the NBO analysis with different DFT functionals. The result shows that PW6B95 predicts the highest En→π∗ value of 1.0 kcal/mol as compared to the other functionals. The density functionals that estimate the second (0.9 kcal/mol) highest En→π∗ values are revTPSS and M062X, respectively. It should be noted that the PW6B95 method predicted a ΔEendo–exo value lower than the chemical accuracy limit for the 4(R)-HyP-endo conformer in our primary calibration study, and therefore, we discarded this DFT functional for the present analysis of stereoelectronic effect together. Similarly, the revTPSS functional, although predicted an appreciably high En→π∗ value of 0.9 kcal/mol, failed to estimate an accurate relative energy (ΔEendo–exo) value close to the MP2 value (vide supra). Therefore, the revTPSS functional is also not a good choice for accurately predicting both relative energy and En→π∗ values together. This leaves us with the M062X hybrid meta-GGA functional among the eight primarily short-listed DFT functionals, which can estimate a reasonably accurate ΔEendo–exo value (1.1 kcal/mol) along with an appreciably high En→π∗ value (0.9 kcal/mol). Therefore, M062X can be the method of choice for the electronic structure and energy calculation of the proline and 4-hydroxyproline conformers.

To provide a deeper insight into the charge-transfer interaction present in the 4(R)-HyP-exo moiety, we analyzed the occupation numbers (O.N.) of the donor (e.g., nCO) and acceptor (π∗CO) orbitals. The O.N. of the donor nCO orbital significantly decreased to 1.89 from its ideal value of ∼2.0, whereas the same for the acceptor orbital appreciably increased to 0.28 from its ideal value of ∼0.0 (Table S3). However, it is rather challenging to directly correlate the occupation numbers of the donor and acceptor orbitals to the En→π∗ values, as other auxiliary charge-transfer processes, such as nCO→σ∗NC and nNH→π∗CO associated with the amide bonds also contribute to the O.N. To verify this, we analyzed the O.N. of the associated orbitals in the single amino acid 4(R)-HyP-exo model and a structure (Structure-1) where the –NH(Me) moiety of one of the amide bonds is replaced with –H (Figure S4). This way, using Structure-1, we target to better estimate the O.N. associated with the primary nCO→π∗CO charge transfer. Indeed, in Structure-1, the O.N. of the donor oxygen lone pair orbital (1.90) and that of the acceptors π∗CO (0.04) and σ∗NC (0.06) is summed to ∼2.0 (Table S3).

With the single amino acid model used over the decades to understand the role of 4-hydroxylation in collagen structure and stability, we anticipated the En→π∗ value to be the highest for the natural 4(R)-HyP-exo conformer. To validate this notion, we used our DFT functional of choice, i.e., M062X in conjunction with Pople’s triple-ζ basis set 6-311+G(d,p) to perform geometry optimization followed by NBO analysis on all the conformational isomers of the single amino acid model (Figure 3A). Surprisingly, a higher En→π∗ value was obtained for two out of the three non-natural conformers, 4(R)-HyP-endo (En→π∗ = 1.1 kcal/mol) and 4(S)-HyP-exo (En→π∗ = 1.0 kcal/mol), as compared to the natural conformer, 4(R)-HyP-exo (En→π∗ = 0.9 kcal/mol). As such, the decreasing order of En→π∗ values in 4-HyP conformers is 4(R)-HyP-endo > 4(S)-HyP-exo > 4(R)-HyP-exo > 4(S)-HyP-endo. To check whether this result is an artifact of the chosen DFT method, we calculated the En→π∗ values with the complete set of twenty-one functionals as presented in Figure 2C. Interestingly, sixteen out of twenty-one functionals including M062X predicted a higher En→π∗ value for a non-natural conformer than the natural one, and the rest five functionals predicted the En→π∗ value of one of the three non-natural conformers equal to the natural one (Figure S5; Table S4). This unexpected observation led us to revisit the amino acid model used in the literature to investigate the role of the stereoelectronic effect in collagen structure.

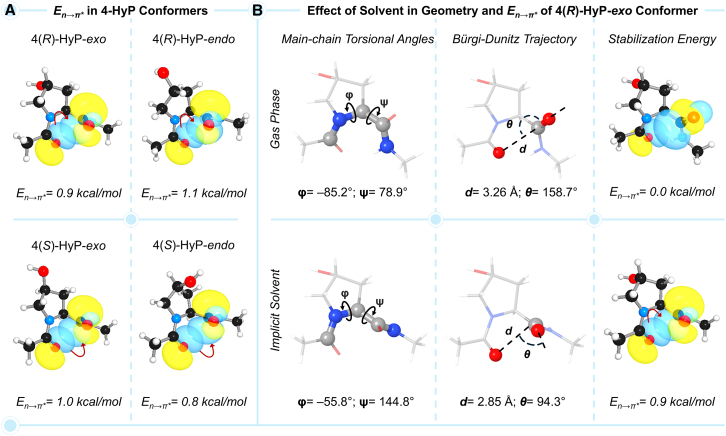

Figure 3.

Geometry and natural bond orbital analysis of 4-HyP conformers

(A) Natural bond orbitals and En→π∗ values in kcal/mol for four different conformers of 4-HyP.

(B) Gas- and solvent-phase geometries of the single amino acid model of the natural 4(R)-HyP-exo conformer along with the natural bond orbitals and En→π∗ values. See also Figure S6.

Effect of solvent on geometry in understanding the role of prolyl-4-hydroxylation

Most quantum chemical studies in the literature on proline derivatives were performed with the single amino acid model and the geometry obtained in the gas-phase optimization.8,9,19,20,21,22 The subsequent NBO analyses were also performed on the gas-phase geometries. To shed light on the effect of the solvent on the amino acid models used, we performed the geometry optimization, frequency calculation, and NBO analysis in both the gas- and solvent-phase (water) at the M062X/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory. The geometrical parameters, i.e., the main-chain torsional angles (ϕ,ψ) associated with the n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction, were compared for the gas- and solvent-phase geometries (Figure 3B). The ϕ and ψ values for the gas-phase optimized geometry, −85.2° and 78.9°, respectively, were found to be far away from the expected values, ϕ = −60 ± 7° and ψ = 150 ± 9°.31 This results in a significant distortion in the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory (d = 3.26 Å and θ = 158.7°), which is far off from the ideal value of θ ∼109°. As a consequence, the structure displayed an En→π∗ value of 0.0 kcal/mol, showing no n→π∗ interaction (Figure 3B). In contrast to the gas-phase geometry, the solvent-phase optimized geometry of the natural conformer, i.e., 4(R)-HyP-exo single amino acid model features the main-chain torsional angles of ϕ = −55.8° and ψ = 144.8°. In addition, the geometrical parameters associated with the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory, d = 2.85 Å, θ = 94.3° get closer to the ideal value and yield an En→π∗ value of 0.9 kcal/mol (Figure 3B). This result nicely showcases the importance of the solvent-phase geometry in understanding the role of prolyl-4-hydroxylation. The solvent appears to have a more pronounced effect on the n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction than on the endo/exo puckering (ΔEendo–exo). This explains why the gas-phase geometries of the single amino acid model used in the literature to investigate the relative energy due to ring puckering were somewhat reasonable. However, for examining the correlation between the geometry and n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction, the inclusion of solvent becomes critical as the charge-transfer effects are best captured in the presence of a polar solvent dielectric environment.32 To better understand the effect of solvent dielectric environment, we also performed the geometry optimization and NBO analysis of the single amino acid model, 4(R)-HyP-exo conformer in ethanol and ethanol:water (1:1) mixture, along with water solvent (Figure S6). However, no appreciable change in geometry was observed for the three solvents. As shown in Figure S6, the crucial C=O···C=O distance (d) associated with the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory remains almost similar in all three geometries obtained in water, ethanol, and ethanol:water (1:1) mixture. As a consequence of the unaltered geometries, the calculated En→π∗ values were also found to be similar (∼1.0 kcal/mol) in all three cases. Therefore, we have performed all our calculations in the physiologically relevant water solvent along with the gas-phase calculations to understand the effect of the solvent. Our electronic structure analyses reveal that the solvent-phase optimized geometry of the single amino acid model is still not ideal for investigating the role of the stereoelectronic effect. Specifically, a higher En→π∗ value was obtained for the non-natural conformer (vide supra), as compared to the natural conformer (Figure 3A). This prompted us to reassess the amino acid model that can correctly rationalize the interplay between different stereoelectronic effects of prolyl-4-hydroxylation on collagen stability.

The physiologically relevant collagenous peptide (PO4G) to probe different stereoelectronic effects

In the pursuit to establish a physiologically relevant collagenous peptide model that can capture n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction more accurately as well as feature main-chain torsional angles (ϕ and ψ) and crucial geometrical parameters (d and θ) associated with Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory close to the crystal structure, we aimed at developing a “triplet” amino acid model. The model was constructed to represent the most abundant tripeptide motifs of a single strand of the collagen (Figure 4A). In humans, type I collagen has a higher count of PPG; 46 out of 127 Xaa–Pro–Gly triplets occur in one chain, as compared to any other triplets.33 Initially, we extracted a tripeptide motif, PO4G, featuring the 4(R)-HyP-exo at the Yaa position, from the crystal structure of collagen (PDB: 2G66), where the terminal amino acids were capped with methyl groups. The geometry optimization of the PO4G triplet model yielded ϕ torsional angle and the geometrical parameters for n→π∗ interaction (d, θ) associated with Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory with significant deviation from the crystal structure (Figure S7A). Consequently, the En→π∗ values were largely overestimated. Specifically, we noticed that the geometrical distortion in Pro at Xaa and Gly flanked to 4-HyP at Yaa was the cause of this deviation. Therefore, to rectify and make the model more realistic, we included two additional amino acids at each terminal, 4-HyP and Gly at the N-terminal, and Pro and 4-HyP at the C-terminal to flank. However, this relatively large amino acid model also turned out to be poor at the full geometry optimization level (Figure S7B).

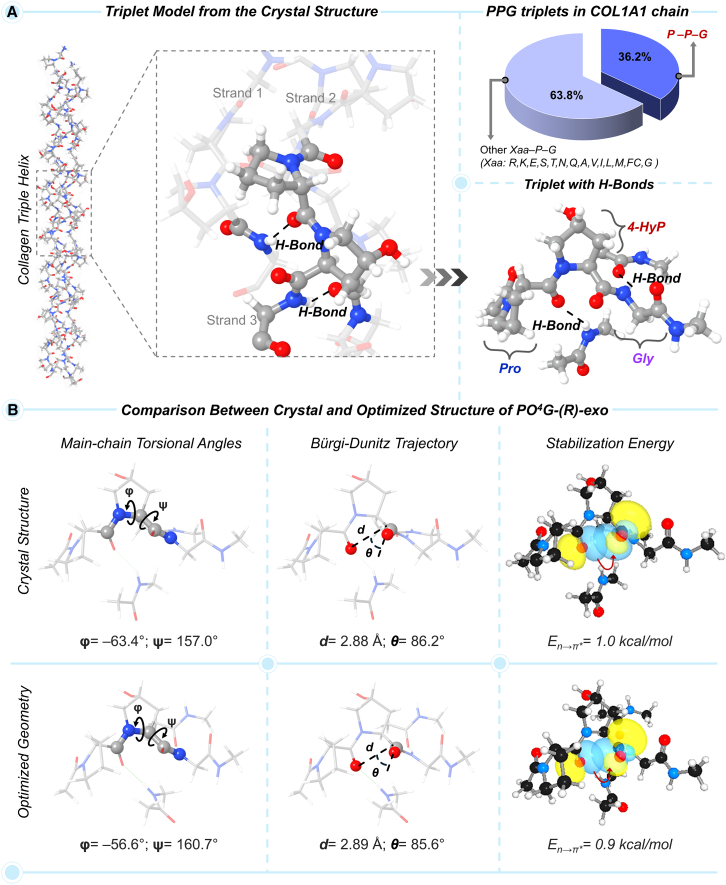

Figure 4.

Occurence of PPG triplet in collagen chain and building the physiologically-relevant PO4G peptide model

(A) Collagen triple-helix structure highlighting a tripeptide unit in a single strand with H-bonding interactions with the other strands. The occupancy of the PPG triplet in the COL1A1 chain is shown.

(B) Evaluation of the main-chain torsional angle and Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory of the DFT-M062X-optimized geometry and the crystal structure. The corresponding En→π∗ value and natural bond orbitals are also shown. See also Figures S7 and S8, and Tables S5 and S6.

In our subsequent attempt to construct a physiologically relevant tripeptide model, we sought to incorporate the inter-helix H-bonding interaction in the PO4G triplet. The –C=O···H–N– hydrogen bonds in collagen triple-helix involve the –C=O moiety of Pro and the –N–H moiety of Gly holding the three strands together, where each triplet-containing unit possesses two of such hydrogen bonds.3,5,34 Using this crucial inter-strand structural feature as a guide, we extracted a triplet from one strand hydrogen-bonded with two peptide bonds from the other two strands (Figure 4A). This triplet PO4G featuring the natural conformer of hydroxyproline, 4(R)-HyP-exo is labeled as PO4G-(R)-exo. In this tripeptide model, the ϕ and ψ dihedral angles of 4-HyP at the Yaa position are calculated to be −56.6° and 160.7°, respectively, which are close to that of the crystal structure (Figure 4B). In addition, the geometrical parameters, d = 2.89 Å and θ = 85.6° in 4(R)-HyP-exo are in close agreement with the crystal structure values, 2.88 Å and 86.2°, respectively (Figure 4B). Such a close geometrical match in the optimized triplet model also yielded an En→π∗ value of 0.9 kcal/mol, almost similar to that calculated with the crystal structure (1.0 kcal/mol, Figure 4B). Therefore, the established physiologically relevant collagenous peptide PO4G can be used further to investigate the correlation between the stereoelectronic parameters due to the prolyl-4-hydroxylation.

As discussed above, the occupancy of 4(R)-HyP with an exo pyrrolidine ring pucker (O4) in the Yaa position of the –Xaa–Yaa–G- triplet (PO4G) directly governs the main-chain torsional angles (ϕ and ψ, Figure 4) to attain their optimal values, ϕ = −60 ± 7° and ψ = 150 ± 9° in the collagen PPII-helix. This conformational uniqueness enforces the –C=O groups of the amide bonds, preceding and succeeding to the pyrrolidine ring of the 4(R)-HyP, to orient at a C=O···C=O distance of 2.89 Å and an ∠OCO angle of 85.6° (Figure 4B). Notably, this angle closely aligns with the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory, the preferred approach angle for a nucleophile attacking a carbonyl group. Table S5 clearly demonstrates that the C=O···C=O donor-acceptor distance is directly correlated with the strength of the n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction in collagenous tripeptides; as the distance increases, En→π∗ decreases. The En→π∗ value is maximum in the PO4G collagenous tripeptide featuring the (R)-exo conformer of the 4-HyP.

To systematically compare other amino acids with 4-HyP at the Yaa position, we began by analyzing the sequence of the helical region in the human collagen-I alpha-1 (COL1A1) chain. The sequence analysis suggests that 35.7% of total tripeptides are PPG (Figure S8A). Melting temperature (Tm°C) experiments have well-established that the presence of 4-HyP at the Yaa position enhances the thermal stability of the collagen triple helix (Table S6).35,36,37,38,39 Notably, replacing 4-HyP with any amino acid—except arginine (Arg)—leads to a significant decrease in the melting temperature. Given the predominant presence of proline in the collagen chain, we primarily focused our investigation on unraveling the stereoelectronic effects, specifically within the PO4G tripeptide. To achieve the systematic comparison involving other amino acids in the Yaa position, we used the relative occupancies of the PYG motifs presented in Figure S8A as a guide. Specifically, we estimated the stabilization effect due to the crucial n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction (En→π∗, kcal/mol) for alanine PAG (24.3%), arginine PRG (7.8%), lysine PKG (6.1%), serine PSG (6.1%), and aspartic acid PDG (0.9%) in the Yaa position of the PYG triplet (Figure S8B). The PAG, PDG, and PKG tripeptides exhibit lower stabilization energy (En→π∗) values compared to PO4G. While PRG and PSG display stabilization energies similar to PO4G, the predominant presence of proline at the Yaa position and its hydroxylation likely exerts a significantly greater stabilizing effect on the collagen triple helix. In line with this, the Tm of PO4G is the highest (Table S6), therefore establishing the crucial role of 4-HyP in collagen thermal stability.39 In their work, Brodsky et al. mentioned that positively charged arginine could engage in side-chain interactions with the available backbone carbonyl groups, contributing to higher thermal stability than hydroxy-proline.39 As the Tm of PRG containing triple helix is close to that of PO4G, its role remains an open question. Thus, a systematic comparison of various amino acids at the Yaa position in the PYG triplet, alongside 4-HyP in the PO4G motif, offers deeper insights into the role of the prevalent PPG sequence in collagen helical stability.

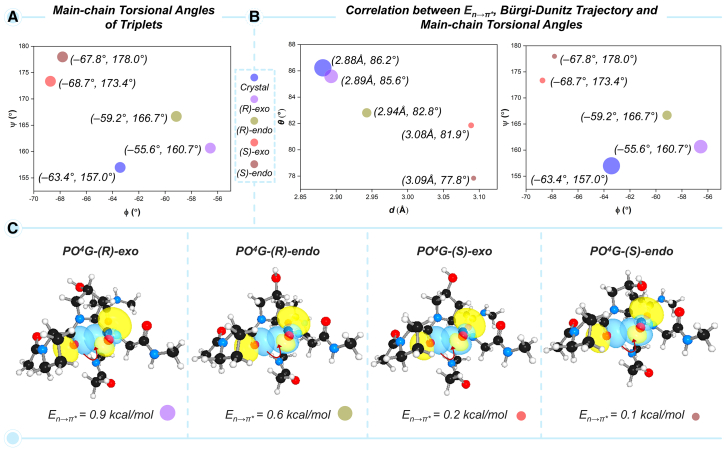

Positional preference of 4-HyP in pre-Organizing the main-chain torsional angles, Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory, and n→π∗ interaction that stabilizes collagen triple-helix is revealed using PO4G triplets containing four different conformers of 4-HyP

To obtain insights into the natural preference of 4(R)-exo conformer, we first compared the geometrical parameters (d and θ), main-chain torsional angles (ϕ and ψ), and electronic parameters, En→π∗ for four different tripeptides, PO4G-(R)-exo, PO4G-(R)-endo, PO4G-(S)-exo, and PO4G-(S)-endo featuring four different conformers of 4-HyP (Figure 5). To assess the geometrical parameters in the DFT-optimized structures, the crystal structure was used as the reference. As shown in Figures 5A and 5B, the ϕ and ψ angles and d and θ in PO4G-(R)-exo are relatively closer to the crystal structure, as compared to the PO4G-(R)-endo, PO4G-(S)-exo, and PO4G-(S)-endo containing unnatural conformers of 4-HyP (Figures 5A and 5B). Due to the optimal geometrical parameters in the PO4G-(R)-exo tripeptide, the En→π∗ value was estimated to be 0.9 kcal/mol (Figure 5C). On the other hand, in the other three triplets containing the non-natural conformers of 4-HyP, the calculated En→π∗ value decreases as, PO4G-(R)-endo (0.6 kcal/mol) > PO4G-(S)-exo (0.2 kcal/mol) and PO4G-(S)-endo (0.1 kcal/mol). Importantly, the En→π∗ value appears to be nicely correlated with the main-chain torsional angles (ϕ and ψ) and geometrical parameters d and θ. As represented in Figure 5B, the highest En→π∗ value (represented with the largest circle) corresponds to the crystal structure, and the next highest is associated with the DFT-optimized PO4G-(R)-exo triplet. As En→π∗ is a quantification of the stabilization energy of a conformer, the above results nicely portray the positional preference of 4-HyP at the Yaa with the exo ring pucker, which not only pre-organizes the main-chain torsional angles but also affects the n→π∗ interaction, stabilizing the overall structure of collagen.

Figure 5.

Correlation between geometrical parameters and n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction in PO4G triplets

(A) Main-chain torsional angles (ϕ and ψ) of triplets along with the crystal structure.

(B) Correlations between En→π∗ and Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory and En→π∗ and main-chain torsional angles.

(C) Natural bond orbitals and En→π∗ values for PO4G triplets bearing the four different conformers of 4-HyP.

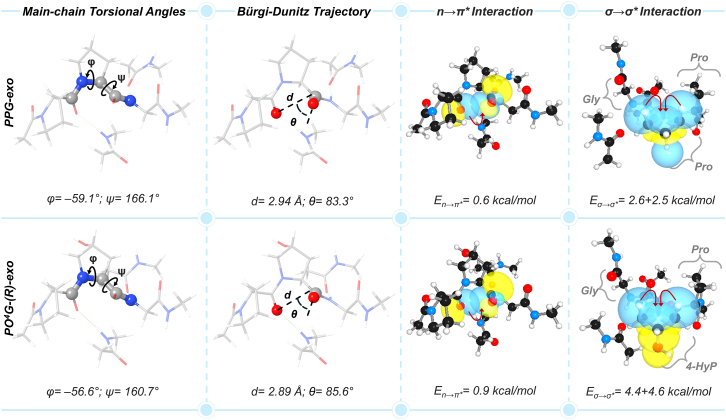

In addition to the correlation between geometrical and electronic parameters of the PO4G tripeptide, it would be interesting to see how the n→π∗ interaction gets affected by the hydroxylation of Pro at the Yaa position. To investigate this, we extracted a tripeptide, PPG-exo from the PDB file (ID: 1K6F). Our calculations reveal that the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory (θ) associated with Pro at Yaa in the optimized geometry of the triplet PPG-exo decreased by 2.3°. Consequently, a lower En→π∗ value of the triplet PPG-exo was obtained; 0.6 kcal/mol vs. 0.9 kcal/mol in the PO4G-(R)-exo triplet (Figure 6). This result verifies that the 4-hydroxylation PTM indeed affects the structural parameters of a collagen single strand. This dictates the strength of the n→π∗ interaction, and thereby increases the collagenous triple-helical stability.

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis between PPG and PO4G triplets

Comparison of geometrical parameters and charge-transfer (n→π∗ and σ→σ∗) interactions between the PPG-exo and PO4G-(R)-exo tripeptides showcasing the effect of 4-hydroxylation at the Yaa position. See also Figure S9.

Moreover, the preference of proline for exo ring pucker increases as the σ→σ∗ interaction between Cβ–Hax/Cδ–Hax and Cγ–X strengthens. The interaction becomes further stronger as the electronegativity of the X substituent increases.9 Therefore, we anticipated a stronger σ→σ∗ interaction may exist in the abundant PO4G-(R)-exo tripeptide, as compared to the unmodified PPG-exo tripeptide. Indeed, the calculated Eσ→σ∗ value of ∼9 kcal/mol for PO4G-(R)-exo tripeptide is twice higher compared to that of the PPG-exo analog (Figure 6). This explains the crucial role of σ→σ∗ charge-transfer interaction in stabilizing the collagenous helicity.

To shed light on the positional preference of 4-HyP at the Yaa position, we examined the analogous O4PG sequence, where 4-HyP is positioned at the Xaa site within the triplet. In this case, we aim to estimate the stabilization effect due to the crucial n→π∗ charge-transfer interaction through the En→π∗ (in kcal/mol) energy calculation for the O4PG triplet. However, the tripeptide model needed to extend to a tetrapeptide model to account for both the amide bonds connected to the 4-Hyp in the Xaa position. This resulted in a GO4PG tetrapeptide sequence with the 4(R)-HyP-exo (O4) conformer. Now, we compared the calculated En→π∗ values for GO4PG-(R)-exo and GPO4G-(R)-exo, featuring the 4(R)-HyP-exo in the Xaa and Yaa positions, respectively. The same computational protocol, as described in the computational detail section, was followed to estimate the En→π∗ values. The computed En→π∗ values, along with the NBOs overlap between the donor and acceptor orbitals are presented in Figure S9.

As shown in Figure S9, the presence of 4(R)-HyP in the Xaa position, in GO4PG-(R)-exo, increases the En→π∗ stabilization energy by 0.4 kcal/mol around the Xaa position and by 1.9 kcal/mol around the Yaa position, compared to the GPO4G-(R)-exo natural analog. This result is counterintuitive, given the natural preference of 4-HyP at the Yaa position, which is known to enhance collagen helical stability. However, the analysis of the main-chain torsional angles (ϕ and ψ) and Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory (d and θ) around Yaa reveals a significant deviation in the GO4PG-(R)-exo sequence from the optimal values. Specifically, a ϕ = −45.1° for Pro in GO4PG-(R)-exo and ϕ = −53.4° for 4-HyP in GPO4G-(R)-exo was observed, where the former significantly deviates from the optimum range of ϕ = −60 ± 7°.31 Furthermore, the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory in GO4PG-(R)-exo, d = 2.72 Å and θ = 93.1°, also appeared to be highly deviated compared to d = 2.78 Å and θ = 97.7° in GPO4G-(R)-exo (Figure S9). Evidently, the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory in GO4PG-(R)-exo is far off from the optimal value of θ ∼109°.17 This unnatural deviation in geometry in GO4PG-(R)-exo overestimates the calculated En→π∗ stabilization energy. Notably, the overall thermal stability (ΔH) GPO4G-(R)-exo motif was calculated to be 0.3 kcal/mol higher compared to the GO4PG-(R)-exo analog. In addition to the unnatural geometrical distortion due to the presence of 4-HyP in the Xaa position, it has been shown in the literature that the collagen model peptide (O4PG)10 with 4-HyP in the Xaa position does not form the triple helix.40 This experimental observation also supports the positional preference of the 4-HyP in the Yaa position. Therefore, though the presence of 4-HyP shows an unnatural increment in En→π∗ at the peptide backbone, the analysis of main-chain torsional angles and the thermochemistry of motifs suggest the opposite, that the presence of 4-HyP at Xaa may hinder the helicity of PPII-like structure of single strand, the thermal stability of triple helix, and the packing of collagen into fibrils. Consequently, 4(R)-HyP with exo ring pucker is likely positionally preferred at Yaa over Xaa in the collagen chain.

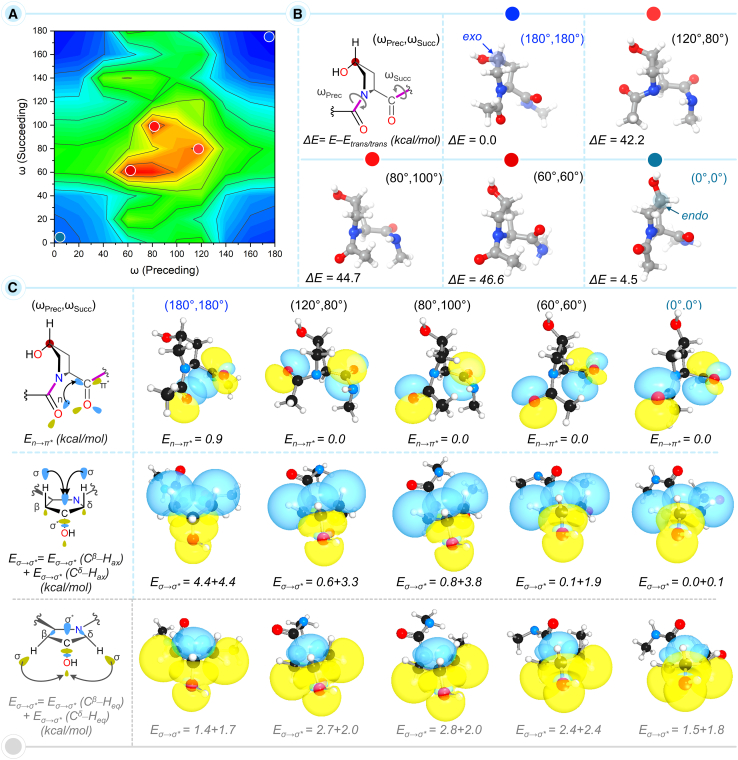

Correlation between the trans-peptide bond and charge-transfer (n→π∗ and σ→σ∗) interactions

It is known that if a peptide bond attains a cis conformation in a single strand of collagen, the collagen triple helix does not form and transport out to the extracellular matrix.41 An isomerase enzyme, called peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (PPIase) is responsible for the conformational change of the cis peptide bond to trans that leads to the formation of the collagen triple helix.42,43 The trans peptide bond connected to the 4-HyP residue in the PO4G triplet is likely to contribute to maximizing the n→π∗ interaction to provide greater stability to the collagen chains and subsequently to the triple helix. To investigate this, relaxed torsional angle (ω) scans of the preceding (ωprec) and succeeding (ωsucc) peptide bonds were performed (Figure 7A; Table S7). Specifically, through the systematic variation of the torsional angle affecting the –C=O···O=C– distance (d), we monitored the En→π∗ values (Figure 7C). This torsional angle vs. En→π∗ analysis is set to provide insights into the interconnection between ring pucker, stereoelectronic effect, and peptide bond conformation.

Figure 7.

Relative energy and NBO analyses of conformers from two-dimensional energy landscape of 4(R)-HyP-exo

(A) A two-dimensional energy landscape of the relaxed torsional angle scans of the preceding (ωprec) and succeeding (ωsucc) peptide bonds of the 4(R)-HyP-exo conformer at the M062X/6-31+G(d,p) level of theory.

(B) The highest, lowest, and a few intermediate energy conformers are presented along with their relative energies (ΔE, kcal/mol).

(C) Calculated En→π∗ and Eσ→σ∗ values (in kcal/mol) associated with the n→π∗ and σ→σ∗ interactions, respectively for five selected conformers. See also Tables S7 and S8.

The trans conformer possessing ωprec ∼180° and ωsucc ∼180° (180°,180°) is calculated to be more stable than the cis isomer with ωprec ∼0° and ωsucc ∼0° (0°,0°) by 4.5 kcal/mol (Figure 7B). This observation falls in line with the established notion. We anticipated that the ring pucker would bear the energy penalty of the cis ↔︎ trans transformation of the peptide bond. To probe the interplay between the peptide bond isomerization and the ring pucker, five different points were selected from the conformational landscape (Figures 7A and 7B). Interestingly, we observed that as one bond moves from trans/trans (180°,180°) to the highest energy point (60°,60°), the pyrrolidine ring becomes almost planar. Moving forward to the other end of the conformational landscape, as both the peptide bonds attain a cis/cis conformation (0°,0°), the ring puckering gets shifted from exo to endo leading to the 4(R)-HyP-endo conformer (Figure 7B). This result nicely showcases the interdependence of the ring puckering and the peptide bond conformation.

Apart from the n→π∗, another type of charge transfer interaction in amino acids can occur between an electron-rich σ-bond donor (e.g., C–H σ orbital) and a vacant electron-deficient σ∗ acceptor (e.g., C–OH σ∗ orbital) orbital. The nature of the σ→σ∗ interaction as the charge transfer interaction is evident from the change in occupation numbers of the associated orbitals (Table S8). With establishing the elegant correlation between the ring puckering and peptide bond conformation, it would be further intriguing to investigate how this correlation is connected to the electronic stabilization effects associated with the n→π∗ and σ→σ∗ charge-transfer interactions. The NBO analysis evidence that the isomerization of both peptide bonds from trans to cis leads to destabilization due to the loss in the n→π∗ interaction. The latter is evident from the En→π∗ value of the trans conformer, 0.9 kcal/mol, which completely diminishes to 0.0 for the cis peptide bond (Figure 7C). As previously discussed in the introduction section, the exo ring pucker is stabilized by the delocalization σ-bonding electrons of Cβ–Hax/Cδ–Hax bonds into σ∗ orbital of Cγ–OH. Therefore, we analyzed the σ→σ∗ interactions to obtain further insights into the electronic stabilization effect (Figure 7C). In the trans/trans (180°,180°) conformer, the strength of σ→σ∗ interactions due to Cβ–Hax and Cδ–Hax was calculated to be equal, 8.8 kcal/mol. During the transition of the peptide bonds from trans/trans (180°,180°) to cis/cis (0°,0°), the strength of the σ→σ∗ interactions gradually reduces. Interestingly, the σ→σ∗ interaction due to the Cβ–Hax reduced more drastically than the other, Cδ–Hax (Figure 7C). The diminished σ→σ∗ charge transfer interaction due to the axial Cβ/δ–Hax bonds of the pyrrolidine ring alters the ring torsional angle χ1 (Figure 1B), which, in turn, dictates the ring pucker, endo, or exo. As such, the peptide bond isomerization is also interconnected with the nature of the ring pucker. This can be further evidenced through the preferred endo ring pucker of the cis/cis (0°,0°) conformer. As the peptide bonds attain the cis/cis (0°,0°) conformer, the σ orbitals of the equatorial Cβ–Heq and Cδ–Heq bonds of the pyrrolidine ring and σ∗ orbital of the Cγ–OH experience an enhanced the σ→σ∗ charge-transfer interactions (Figure 7C). This stabilization effect eventually favors an endo ring pucker instead of the exo, which explains why the natural trans/trans peptide bond conformer favors an exo ring pucker for the pyrrolidine ring.

In addition to the electronic stabilization effect due to the peptide bond conformation, to qualitatively assess how the change in peptide bond conformation affects the pyrrolidine ring puckering, we analyzed the distortion experienced in the ring at four corner points on the two-dimensional energy landscape, i.e., (180°,180°), (0°,180°), (180°,0°), and (0°,0°) (Figure S10B). For this purpose, the conformers were fragmented into pyrrolidine ring and peptide bonds, and the fragments were capped with H atoms. Then, the relative energies of the rings with respect to that of the (180°,180°) ring were compared. The ring conformer at (0°,180°) experiences the highest distortion due to the peptide bond isomerization, as reflected in the relative energy value of 4.9 kcal/mol. A lower degree of destabilization, by 0.1 and 1.3 kcal/mol was observed for the ring conformers at (180°,0°), and (0°,0°), respectively. Although the highest degree of destabilization to the ring pucker is expected to be observed at (0°,0°), the change in ring pucker from exo to endo at this point likely compensates for the destabilization energy. Thus, the correlation between cis ↔ trans peptide bond conformation, pyrrolidine ring puckering, and electronic stabilization due to n→π∗ and σ→σ∗ charge-transfer interactions established in this section nicely rationalizes the natural preference of the trans peptide bond conformation.

Conclusions

Using a calibrated DFT method and a physiologically relevant collagenous PO4G tripeptide, we have investigated the elegant interplay between different stereoelectronic effects, pyrrolidine ring puckers, torsional angles (ϕ, ψ, and ω), peptide bond cis/trans conformation, and n→π∗/σ→σ∗ charge-transfer interaction, all governed by prolyl-4-hydroxylation in achieving collagen triple-helical stability. Our work employs the PO4G tripeptide, incorporating four different conformers of 4-HyP–PO4G-(R)-exo, PO4G-(R)-endo, PO4G-(S)-exo, and PO4G-(S)-endo–alongside the non-hydroxylated PPG tripeptide to unveil the positional preference of 4-HyP with (R)-exo ring pucker. Specifically, the geometrical parameters and NBO analyses of the collagenous tripeptide at the DFT-M062X level show 4-HyP in the PO4G-(R)-exo tripeptide enforces the trans peptide bond conformation through the optimal values of the main-chain torsional angles. This, in turn, tunes the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory to achieve the highest En→π∗ of 0.9 kcal/mol in the PO4G-(R)-exo triplet. The NBO analyses also uncover that the (R)-exo ring pucker, due to 4-hydroxylation, gains additional stability due to the σ→σ∗ charge-transfer interaction between the axial Cβ/δ–H σ bonds and Cγ–OH σ∗ orbital in the pyrrolidine ring, contributing to the helical stability. Overall, this work offers a fundamental electronic-level understanding of collagenous helical stability driven by the intricate interplay of inter-connected stereoelectronic effects arising from prolyl-4-hydroxylation. Additionally, this study also paves the way for an accurate quantum chemical understanding of the role of other PTMs that contribute to collagen stability.

Limitations of the study

This study has not delved into the effect of other amino acids (positively and negatively charged and neutral) present at the Xaa position (non-Pro-4HyP-Gly motif) on the helical stabilization attained by prolyl-4-hydroxylation catalyzed by different prolyl-4-hydroxylases.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Requests for further information and resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Bhaskar Mondal (bhaskarmondal@iitmandi.ac.in).

Materials availability

The study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

Data: Optimized Cartesian coordinates for all single amino acid and large amino acid models used in the study are available in the Mendeley data repository (Joshi, Ashutosh; Basak, Trayambak; Mondal, Bhaskar (2025), “Decoding Elegant Interplay Between Different Stereo-Electronic Effects Due to the Ancient Prolyl-4-Hydroxylation Stabilizing Collagenous Helicity”, Mendeley Data, V1, https://doi.org/10.17632/ychk3jfdfk.1).

-

•

Code: No code was generated in this study.

-

•

Other: See the STAR Methods section for methodological details. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

A.J. thanks the Ministry of Education (MoE), Government of India, for the research fellowship. T.B. and B.M. are further grateful for the funding support from the Department of Biotechnology, Govt. of India, for “Understanding the prolyl-3-hydroxylase 1 (P3H1) mediated perturbed post-translational modification of collagen network aggravating fibrotic remodeling during myocardial infarction”, DBT – BT/PR/50004/CMD/150/148/2023. B.M. and T.B. are also grateful for the funding support from the Anusandhan National Research Foundation-Science and Engineering Research Board (ANRF-SERB) in the form of Core Research Grants, CRG/2023/002138 and CRG/2022/006204, respectively. The authors acknowledge the National Supercomputing Mission (NSM), for providing computing resources of ‘PARAM Himalaya’ at IIT Mandi, which is implemented by C-DAC and supported by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) and Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India. In addition, the High-Performance Computing (HPC) facility at IIT Mandi is also acknowledged for providing high-end computational resources. Further, we dedicate this work to Prof. Ronald T. Raines (MIT Chemistry), whose pioneering contributions to the field of prolyl-4-hydroxylation have been a profound source of inspiration for our research.

Author contributions

A.J., T.B., and B.M. designed the project. A.J. executed all the theoretical calculations. The manuscript was written with contributions from all the authors.

Declaration of interests

There are no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| Data S1. Optimized Cartesian coordinates of all the single amino acid and large models used in the study. | Mendeley data repository | https://doi.org/10.17632/ychk3jfdfk.1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Gaussian16 | Frish et al.44 | https://gaussian.com |

| ORCA 4.2.1 | Neese, F.45 | https://orcaforum.kofo.mpg.de/app.php/portal |

| NBO 7.0 | Glendening et al.46 | https://nbo6.chem.wisc.edu/ |

| NBO7Pro@Jmol | Glendening et al.46 | https://nbo6.chem.wisc.edu/ |

| ChemDraw Professional 22.0 | Revvity Signals | https://revvitysignals.com/products/research/chemdraw |

| Chimera 1.16 | UCSF Chimera, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from NIH P41-GM103311. | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ |

| Origin 2021 | OriginLab Corporation | https://www.originlab.com/ |

Method details

A thorough benchmarking of the density functional theory (DFT) method used in this work was performed against correlated ab initio quantum chemical methods, viz. 2nd-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2)47,48,49 and domain-based local pair natural orbital coupled cluster method with single-, double, and triple-excitations (DLPNO-CCSD(T)).50 Considering the vast data set, we restricted our benchmarking to the single amino acid model, like 4-HyP or other proline derivatives. The relative energy between the two pyrrolidine ring conformers, ΔEendo–exo = E[4(R)-endo] – E[4(R)-exo], was taken as the key parameter for the benchmarking study. To select an appropriate DFT method, we began with a total of twenty-four density functionals, involving four pure generalized gradient approximation (GGA), seven hybrid GGA, three pure meta-GGA, seven hybrid meta-GGA, and three double-hybrid GGA functionals (Table S9). The non-covalent interaction due to the dispersion effect was considered during the DFT calculations using Grimme’s empirical dispersion corrections, D2,51 D30,52 and D3 with Becke-Johnson damping (D3BJ).53 Three different dispersion corrections were needed due to the lack of parameters for a single dispersion correction in the Gaussian 1644 program for different functionals. On top of this, DFT functionals with varying percentages of Hartree-Fock exchange (%HF-X), starting from 0% to 55% were selected, to investigate the role of %HF-X in relative energies.

To obtain the most accurate DFT functional to be employed for the geometry and electronic structure, first, we sought to calibrate the DFT functionals against the gold-standard ab initio methods, i.e., DLPNO-CCSD(T). Importantly, the DLPNO-CCSD(T) method is capable of estimating relative energies (ΔE) within the chemical accuracy limit of ∼1 kcal/mol. However, as this method is available with the ORCA45 suite of quantum chemical programs, we first calibrated the ab initio MP2 method available in the ORCA program (Figure S1). While optimized equilibrium geometries were obtained for all DFT and MP2 methods, the MP2-level geometries optimized in Gaussian 16 were used for the calibration of MP2 against DLPNO-CCSD(T) in ORCA by single point energy (SPE) calculations (Table S10). All equilibrium geometries were verified to be local minima through the harmonic vibrational frequency calculation. Pople’s triple-ζ quality basis set with single diffuse and double polarization functions, 6-311+G(d,p)54,55 was used for the DFT-level, and Dunning’s correlation consistent augmented triple-ζ basis set with diffuse functions, aug-cc-pVTZ56,57,58 was used for the MP2-level geometry optimization. The DLPNO-CCSD(T) energy calculations were performed in conjunction with Dunning’s aug-cc-pVTZ basis set. The geometry optimization and energy calculations at the MP2 level of theory were accelerated with the resolution of the identity (RI) for the Coulomb part and a chain of spheres algorithm for the Hartree-Fock exchange part (RIJCOSX). The RIJCOSX approximation was also used to accelerate the energy calculations at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) level. The electrostatic effect due to solvation was taken into account during the geometry optimizations through the implicit solvent model based on density (SMD) and water as solvent.

Once the ab initio MP2 method is calibrated against the DLPNO-CCSD(T) energies, we selected the MP2 method as the standard for our benchmarking of DFT functionals. To access an extended set of DFT functionals, we re-optimized the 4-HyP conformers with twenty-four DFT functionals (vide supra) along with the ab initio MP2 level using the Gaussian 16 program. The basis set, dispersion correction, and effect due to solvation were used consistently as described above.

To investigate the electronic structure, chemical bonding, and stabilization due to n→π∗ and σ→σ∗ charge-transfer interactions, natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis was performed on the DFT-optimized geometries. The NBO 7.046 program suite was used for this purpose. The stabilization provided by n→π∗ charge-transfer interactions was quantified using energy obtained from the second-order perturbation theory (E(2)) implemented in the NBO 7.0 program. The natural bond orbitals were viewed with the “View” module of NBOPro7@Jmol visualization software.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Gaussian 1644 and ORCA45 programs were used for the geometry optimization. NBO 7.046 program was used to quantify the charge-transfer interactions.

Published: April 10, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.112393.

Contributor Information

Trayambak Basak, Email: trayambak@iitmandi.ac.in.

Bhaskar Mondal, Email: bhaskarmondal@iitmandi.ac.in.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Pokidysheva E., Boudko S., Vranka J., Zientek K., Maddox K., Moser M., Fässler R., Ware J., Bächinger H.P. Biological role of prolyl 3-hydroxylation in type IV collagen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:161–166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307597111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang J., Kojasoy V., Porter G.J., Raines R.T. Pauli Exclusion by n→π∗ Interactions: Implications for Paleobiology. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024;10:1829–1834. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.4c00971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bella J. Collagen structure: New tricks from a very old dog. Biochem. J. 2016;473:1001–1025. doi: 10.1042/BJ20151169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onursal C., Dick E., Angelidis I., Schiller H.B., Staab-Weijnitz C.A. Collagen Biosynthesis, Processing, and Maturation in Lung Ageing. Front. Med. 2021;8:593874. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.593874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoulders M.D., Raines R.T. Collagen structure and stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:929–958. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.032207.120833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramshaw J.A., Shah N.K., Brodsky B. Gly-X-Y tripeptide frequencies in collagen: A context for host-guest triple-helical peptides. J. Struct. Biol. 1998;122:86–91. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitagliano L., Berisio R., Mazzarella L., Zagari A. Structural Bases of Collagen Stabilization Induced by Proline Hydroxylation. Biopolymers. 2001;58:459–464. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(20010415)58:5<459::AID-BIP1021>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeRider M.L., Wilkens S.J., Waddell M.J., Bretscher L.E., Weinhold F., Raines R.T., Markley J.L. Collagen stability: Insights from NMR spectroscopic and hybrid density functional computational investigations of the effect of electronegative substituents on prolyl ring conformations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2497–2505. doi: 10.1021/ja0166904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Improta R., Benzi C., Barone V. Understanding the role of stereoelectronic effects in determining collagen stability. 1. A quantum mechanical study of proline, hydroxyproline, and fluoroproline dipeptide analogues in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12568–12577. doi: 10.1021/ja010599i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmgren S.K., Taylor K.M., Bretscher L.E., Raines R.T. Code for collagen’s stability deciphered. Nature. 1998;392:666–667. doi: 10.1038/33573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okuyama K., Hongo C., Wu G., Mizuno K., Noguchi K., Ebisuzaki S., Tanaka Y., Nishino N., Bächinger H.P. High-resolution structures of collagen-like peptides [(Pro-Pro-Gly)4-Xaa-Yaa-Gly-(Pro-Pro-Gly)4]: Implications for triple-helix hydration and Hyp(X) puckering. Biopolymers. 2009;91:361–372. doi: 10.1002/bip.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitagliano L., Berisio R., Mastrangelo A., Mazzarella L., Zagari A. Preferred proline puckerings in cis and trans peptide groups: Implications for collagen stability. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2627–2632. doi: 10.1110/ps.ps.26601a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berisio R., Vitagliano L., Mazzarella L., Zagari A. Crystal structure of the collagen triple helix model [(Pro-Pro-Gly) 10 ] 3. Protein Sci. 2002;11:262–270. doi: 10.1110/ps.32602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramachandran G.N., Kartha G. Structure of collagen. Nature. 1955;176:593–595. doi: 10.1038/176593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bürgi H.B., Dunitz J.D., Shefter E. Geometrical Reaction Coordinates. II. Nucleophilic Addition to a Carbonyl Group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:5065–5067. doi: 10.1021/ja00796a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bürgi H.B., Dunitz J.D., Lehn J.M., Wipff G. Stereochemistry of reaction paths at carbonyl centres. Tetrahedron. 1974;30:1563–1572. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90678-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newberry R.W., Raines R.T. The n→π∗ Interaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:1838–1846. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choudhary A., Gandla D., Krow G.R., Raines R.T. Nature of amide carbonyl-carbonyl interactions in proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7244–7246. doi: 10.1021/ja901188y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bretscher L.E., Jenkins C.L., Taylor K.M., Derider M.L., Raines R.T. Conformational Stability of Collagen Relies on a Stereoelectronic Effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:777–778. doi: 10.1021/ja005542v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins C.L., Lin G., Duo J., Rapolu D., Guzei I.A., Raines R.T., Krow G.R. Substituted 2-azabicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes as constrained proline analogues: Implications for collagen stability. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:8565–8573. doi: 10.1021/jo049242y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinderaker M.P., Raines R.T. An electronic effect on protein structure. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1188–1194. doi: 10.1110/ps.0241903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodges J.A., Raines R.T. Energetics of an n → π∗ interaction that impacts protein structure. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4695–4697. doi: 10.1021/ol061569t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shoulders M.D., Hodges J.A., Raines R.T. Reciprocity of steric and stereoelectronic effects in the collagen triple helix. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8112–8113. doi: 10.1021/ja061793d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogojeski M., Vogt-Maranto L., Tuckerman M.E., Müller K.R., Burke K. Quantum chemical accuracy from density functional approximations via machine learning. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5223. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19093-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riplinger C., Neese F. An efficient and near linear scaling pair natural orbital based local coupled cluster method. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138 doi: 10.1063/1.4773581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liakos D.G., Sparta M., Kesharwani M.K., Martin J.M.L., Neese F. Exploring the accuracy limits of local pair natural orbital coupled-cluster theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:1525–1539. doi: 10.1021/ct501129s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartlett G.J., Choudhary A., Raines R.T., Woolfson D.N. n→π∗ interactions in proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:615–620. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahim A., Saha P., Jha K.K., Sukumar N., Sarma B.K. Reciprocal carbonyl-carbonyl interactions in small molecules and proteins. Nat. Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00081-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed A.E., Curtiss L.A., Weinhold F. Intermolecular Interactions from a Natural Bond Orbital, Donor—Acceptor Viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:899–926. doi: 10.1021/cr00088a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landis C.R., Weinhold F. In: The Chemical Bond: Fundamental Aspects of Chemical Bonding. Frenking G., Shaik S., editors. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2014. The NBO View of Chemical Bonding; pp. 91–120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egli J., Schnitzer T., Dietschreit J.C.B., Ochsenfeld C., Wennemers H. Why Proline? Influence of Ring-Size on the Collagen Triple Helix. Org. Lett. 2020;22:348–351. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rondi A., Rodriguez Y., Feurer T., Cannizzo A. Solvation-driven charge transfer and localization in metal complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1432–1440. doi: 10.1021/ar5003939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salo A.M., Rappu P., Koski M.K., Karjalainen E., Izzi V., Drushinin K., Miinalainen I., Käpylä J., Heino J., Myllyharju J. Collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase isoenzymes I and II have sequence specificity towards different X-Pro-Gly triplets. Matrix Biol. 2024;125:73–87. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2023.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramachandran G.N., Kartha G. Structure of collagen. Nature. 1954;174:269–270. doi: 10.1038/174269c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah N.K., Ramshaw J.A., Kirkpatrick A., Shah C., Brodsky B. A host-guest set of triple-helical peptides: Stability of Gly-X-Y triplets containing common nonpolar residues. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10262–10268. doi: 10.1021/bi960046y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan V.C., Ramshaw J.A., Kirkpatrick A., Beck K., Brodsky B. Positional Preferences of Ionizable Residues in Gly-X-Y Triplets of the Collagen Triple-helix. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31441–31446. doi: 10.1074/JBC.272.50.31441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmgren S.K., Bretscher L.E., Taylor K.M., Raines R.T. A hyperstable collagen mimic. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:63–70. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck K., Chan V.C., Shenoy N., Kirkpatrick A., Ramshaw J.A., Brodsky B. Destabilization of osteogenesis imperfecta collagen-like model peptides correlates with the identity of the residue replacing glycine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4273–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070050097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Persikov A.V., Ramshaw J.A., Kirkpatrick A., Brodsky B. Amino acid propensities for the collagen triple-helix. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14960–14967. doi: 10.1021/bi001560d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inouye K., Kobayashi Y., Kyogoku Y., Kishida Y., Sakakibara S., Prockop D.J. Synthesis and physical properties of (hydroxyproline-proline-glycine)10: Hydroxyproline in the X-position decreases the melting temperature of the collagen triple helix. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1982;219:198–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu K.P., Finn G., Lee T.H., Nicholson L.K. Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:619–629. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishikawa Y., Bächinger H.P. A molecular ensemble in the rER for procollagen maturation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 2013;1833:2479–2491. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishikawa Y., Boudko S., Bächinger H.P. Ziploc-ing the structure: Triple helix formation is coordinated by rough endoplasmic reticulum resident PPIases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2015;1850:1983–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Li X., et al. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2019. Gaussian 16. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neese F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012;2:73–78. doi: 10.1002/wcms.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.NBO 7.0. Glendening E.D., Badenhoop J.K., Reed A.E., Carpenter J.E., Bohmann J.A., Morales C.M., Karafiloglou P., Landis C.R., Weinhold F. Theoretical Chemistry Institute. University of Wisconsin; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Head-Gordon M., Pople J.A., Frisch M.J. MP2 energy evaluation by direct methods. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988;153:503–506. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(88)85250-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frisch M.J., Head-Gordon M., Pople J.A. Semi-direct algorithms for the MP2 energy and gradient. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1990;166:281–289. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(90)80030-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frisch M.J., Head-Gordon M., Pople J.A. A direct MP2 gradient method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1990;166:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(90)80029-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riplinger C., Sandhoefer B., Hansen A., Neese F. Natural triple excitations in local coupled cluster calculations with pair natural orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139 doi: 10.1063/1.4821834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006;27:1787–1799. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grimme S., Antony J., Ehrlich S., Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132 doi: 10.1063/1.3382344/926936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimme S., Ehrlich S., Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/JCC.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLean A.D., Chandler G.S. Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z=11-18. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:5639–5648. doi: 10.1063/1.438980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krishnan R., Binkley J.S., Seeger R., Pople J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:650–654. doi: 10.1063/1.438955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kendall R.A., Dunning T.H., Harrison R.J. Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;96:6796–6806. doi: 10.1063/1.462569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woon D.E., Dunning T.H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. III. The atoms aluminum through argon. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:1358–1371. doi: 10.1063/1.464303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dunning T.H., Jr., Peterson K.A., Wilson A.K. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. X. The atoms aluminum through argon revisited. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:9244–9253. doi: 10.1063/1.1367373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Data: Optimized Cartesian coordinates for all single amino acid and large amino acid models used in the study are available in the Mendeley data repository (Joshi, Ashutosh; Basak, Trayambak; Mondal, Bhaskar (2025), “Decoding Elegant Interplay Between Different Stereo-Electronic Effects Due to the Ancient Prolyl-4-Hydroxylation Stabilizing Collagenous Helicity”, Mendeley Data, V1, https://doi.org/10.17632/ychk3jfdfk.1).

-

•

Code: No code was generated in this study.

-

•

Other: See the STAR Methods section for methodological details. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.