Abstract

Antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi has become more important given the recognition of drug-resistant organisms and the availability of therapies other than amphotericin B (AMB). As current microdilution and E-test methods are limited by a 2 to 3 day incubation time required to obtain results, a more rapid method for susceptibility testing of fungi is needed. We report here a flow cytometric assay that relies on conidial metabolism of the viability dye FUN-1. Conidia are incubated in media containing increasing concentrations of AMB for 3 h, exposed to FUN-1, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Relative susceptibility to AMB can be measured both by forward and side scatter characteristics of the conidial population and by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the dye. MIC, calculated as the concentration of AMB to yield 90% reduction in MFI relative to growth controls, was determined for 27 clinical isolates Aspergillus species and correlated well with the standard (i.e., NCCLS) method. The results of these studies illustrate a method by which AMB susceptibility can be rapidly and reproducibly determined by measuring conidial viability.

One antifungal drug of choice for primary treatment of invasive aspergillosis is amphotericin B (AMB). Several reports have described in vitro tolerance or resistance of Aspergillus spp., which correlate with therapeutic failure (8, 15, 21). Amphotericin B resistance appears to be particularly frequent among isolates of Aspergillus terreus, and other filamentous fungi, such as Fusarium spp. and Scedosporium spp. (3). For infection with these organisms, new triazole antifungals may be more effective alternatives. Given the impending availability of alternative antifungals, rapid, reproducible methods to measure in vitro antifungal susceptibility of filamentous fungi are needed.

The National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) M38-P document has recommended a standardized broth dilution method to perform antifungal drug susceptibility testing of conidium-forming fungi (20). Alternative methods which quantify mycelial protein (23), glucose consumption (4), mitochondrial respiration (13), and inhibition of glucan synthase (7) by serial dilution, drug diffusion (1), and E-test (3) assays have been reported. Since most of these methods require mycelial growth, these assays require long incubation times (2 to 3 days) and are labor-intensive.

FUN-1 is a membrane-permeant fluorescent probe that is converted into orange-red cylindrical intravacuolar structures (CIVS) in metabolically active cells (14). Cells with impaired metabolism do not form CIVS. FUN-1 has been used to assess the effect of antifungals on Candida albicans (17, 22), to study the cytotoxic effect of acetic acid on Zygosaccharomyces bailii (18), and to study the killing efficacy of Aspergillus fumigatus by monocytes (11). FUN-1 has also been used to study the effect of azole antifungals (voriconazole and itraconazole) on A. fumigatus by evaluation of hyphal dye metabolism (9).

We hypothesized that antifungal susceptibility may be more rapidly determined by conidial viability analysis with FUN-1. We report here the development of a flow cytometric method and the results of blinded analyses on a large number of susceptible and resistant isolates. The results suggest that analysis of conidial viability with a fluorescent probe provides rapid, reproducible measures of Aspergillus species susceptibility to AMB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates and media.

One AMB-susceptible A. fumigatus isolate (B5233; NCCLS MIC, 0.5 μg/ml) and one AMB-resistant A. terreus isolate (F2B7; NCCLS MIC, >2 μg/ml) were used to develop the flow cytometric (FCM) method. Isolates were originally obtained from clinical specimens at the National Institutes of Health (B5233) and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC; F2B7). For subsequent comparative testing by NCCLS- and FUN-1-based methods, 24 isolates of A. fumigatus and 3 isolates of A. terreus were randomly selected from a clinical specimen bank (FHCRC). All of the isolates were identified by colony morphology and microscopic characteristics and were stored in water suspensions at 4°C. Prior to testing, each isolate was subcultured at least twice on potato dextrose agar to ensure optimal growth characteristics.

RPMI 1640 (with l-glutamine and without sodium bicarbonate; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (Sigma) was used for NCCLS broth microdilution testing. All assays that measured conidial viability by the FCM method utilized RPMI 1640 with 2% glucose (RPMI+Glu) media in order to accelerate metabolism and CIVS formation (12).

AMB (Sigma) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to yield a stock solution of 1,600 μg/ml. Further drug dilutions were made in RPMI, RPMI+Glu, or Na-HEPES, where appropriate.

Susceptibility testing by broth microdilution.

The broth microdilution method utilized was adapted from the NCCLS M38-P document. To prepare conidial inocula, Aspergillus colonies were flooded with sterile RPMI containing 0.025% Tween 20 and gently probed with a pipette tip. The resulting suspension was vortexed, heavy particles were allowed to settle for 3 to 5 min, and the upper layer was adjusted to a percentage transmittance of 80 to 82% by using a spectrophotometer (wavelength, 530 nm). The adjusted inoculum was diluted 1:50 in RPMI 1640, 100 μl was dispensed into microtiter wells containing serial twofold dilutions of AMB, and plates were incubated for 48 h at 35°C. MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of drug that produced 90% reduction in the optical density at 550 nm (OD550) relative to the growth control.

Susceptibility testing with the fluorescent probe.

Conidial concentration, FUN-1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) concentration, and incubation times were optimized for susceptibility testing. Initial experiments were carried out in duplicate with A. fumigatus B5233 and A. terreus F2B7. Conidial suspensions, prepared in RPMI+Glu, were adjusted to 80 to 82% optical transmittance to yield a conidial concentration of 1 × 106 to 5 × 106 cells/ml (16), and 200 μl was dispensed into polystyrene round-bottom FACS tubes (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). Then, 200 μl of AMB (diluted in RPMI+Glu) was added to yield final drug concentrations of 0.0625 to 2 μg/ml. For controls, conidia were suspended in media alone (live control) or in 70% ethanol (dead control). The tubes were vortexed and incubated at 35°C with continuous shaking for 3 h. Thereafter, FUN-1 was added to a final concentration of 5 μmol, and the tubes were reincubated for 45 min at 30°C in the dark.

Data acquisition was performed by using a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The instrument parameters were forward light scatter (FSc), side light scatter (SSc), green fluorescence detection at 530 ± 15 nm (FL 1), and orange fluorescence detection at 560 ± 15 nm (FL 2). A total of 5,000 cells were acquired, and analysis was performed by using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Controls included unstained and FUN-1-stained live and dead (ethanol-killed) conidia. The results acquired by the FCM method were confirmed by visualizing the cells with a Deltavision wide-field fluorescent microscope (Applied Precision, Inc., Issaquah, Wash.) fitted with a fluorescein isothiocyanate and rhodamine filter set.

The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the drug-treated cells, analyzed in both FL-1 and FL-2 channels, decreased with increasing concentrations of AMB. In keeping with the NCCLS 38-P method, the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of AMB that caused 90% reduction in the MFI compared to the untreated (growth) controls. To compare the results of the two methods, MICs for all 27 Aspergillus isolates were obtained by the NCCLS microdilution method. These isolates were then coded and analyzed in a blinded fashion by using the FCM-based assay.

Viability assay.

To measure the viability of drug-treated conidial suspensions, aliquots were removed after incubation with AMB (and before the FCM assay), serially diluted, and plated in duplicate onto yeast extract agar containing Triton X-100 (10 g of yeast extract, 20 g of peptone, 20 g of dextrose, 20 g of agar, and 50 μl of Triton X-100 per liter). Plates were incubated at 35°C, colonies were counted, and results were expressed as CFU relative to untreated controls.

RESULTS

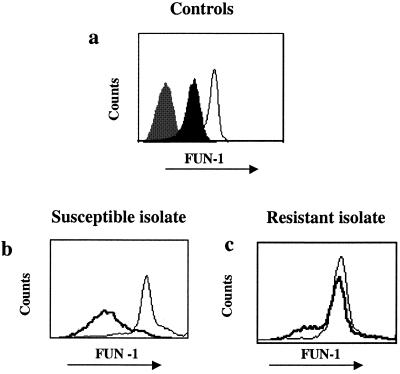

The growth of fungal conidia results in an increase in cellular size over time, which was reflected by changing light scatter characteristics. Figure 1 illustrates the FSc and SSc characteristics of susceptible (Fig. 1a) and resistant (Fig. 1b) conidia, in the presence (right panel) or absence of (left panel) of AMB. After 3 h of incubation in AMB at a concentration equivalent to the NCCLS 90% MIC (MIC90), i.e., 0.5 μg/ml, susceptible conidia were characterized by a homogenous population of small cells. At lower drug concentrations, conidial growth was apparent, and light scatter characteristics were similar to those of the growth control (data not shown). The conidia of the resistant isolate (NCCLS MIC, >2 μg/ml) continued to grow even when incubated with high concentrations of AMB, showing no shift in the FSc and SSc ratio (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

(a) Light scatter characteristics of conidia. FSc and SSc characteristics of susceptible conidia (NCCLS; MIC, 0.5 μg/ml) incubated with 0.5 μg of AMB (right panel)/ml show an overall decrease in size compared to the growth control (left panel). (b) Conidia of the resistant isolate (NCCLS; MIC, >2 μg/ml) continue to grow when incubated with 2 μg/ml (right panel), showing no shift in FSc and SSc properties.

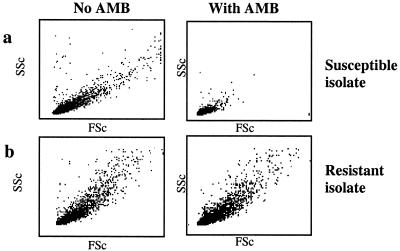

Within 30 min of incubation with FUN-1, live A. fumigatus and A. terreus conidia took up and converted the FUN-1 dye into bright orange-red CIVS (as documented under a microscope). There is no difference in the rate or extent to which the two Aspergillus species metabolized FUN-1 (data not shown). Representative histograms of FUN-1 fluorescence within live and dead populations of Aspergillus conidia are shown in Fig. 2a. Live conidia converted FUN-1 into red-orange CIVS (open histograms), whereas ethanol-killed conidia did not, thus yielding a very dim fluorescence (black-shaded histogram). Conidia demonstrated no autofluorescence in the absence of FUN-1 (gray-shaded histogram).

FIG. 2.

Conidial FUN-1 fluorescence. (a) FUN-1 orange fluorescence of live (open histogram) and ethanol-killed (solid histogram) A. fumigatus controls are shown. The gray shaded histogram (leftmost peak) represents conidia in the absence of FUN-1. (b and c) FUN-1 orange fluorescence in the absence (open histogram) and presence of 2 μg/ml AMB (bold histograms) is shown for the susceptible and resistant isolates.

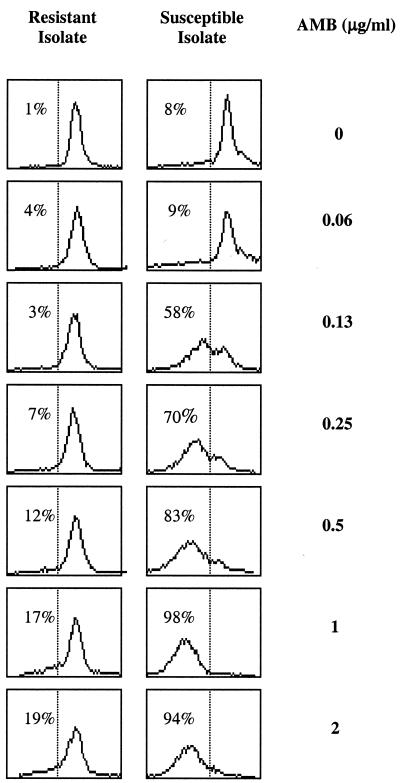

We investigated whether FUN-1 fluorescence can be used to measure viability after exposure to AMB (Fig. 2b and c). Susceptible A. fumigatus conidia pretreated with high concentrations (2 μg/ml) of AMB (Fig. 2b, bold histogram) metabolized FUN-1 less well compared to growth controls (Fig. 2b). When viewed under a microscope, these susceptible conidia exhibited a very dim fluorescence and were reduced in size (data not shown). The histograms in Fig. 3 illustrate that the percentage of conidia expressing FUN-1 fluorescence decreased progressively with increasing concentrations of AMB. The percentage of conidia within the FUN-1-negative gate (indicated in left of histograms) correlated with the MIC determined by NCCLS methods (0.5 μg/ml). In contrast, the MFI of the resistant conidia is equivalent to that of the growth control, even at high concentrations of AMB (>2 μg/ml, Fig. 2c and 3b).

FIG. 3.

Serial histogram profiles. The FUN-1 orange fluorescence results of conidia treated with increasing concentrations of AMB are shown for susceptible and resistant Aspergillus isolates. The percentage of cells within the FUN-1-negative gate is indicated.

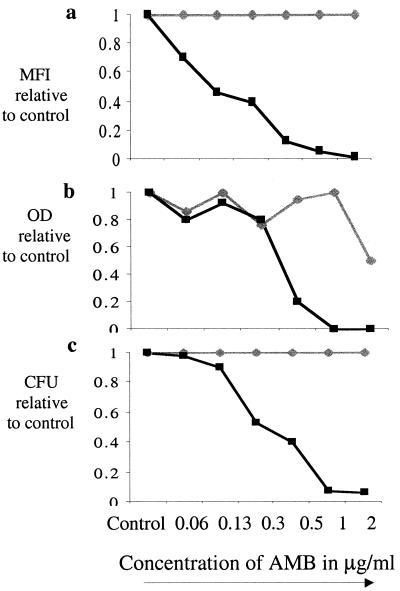

The AMB concentration at which conidial growth is inhibited can be defined by the Fsc and Ssc characteristics and the MFI of FUN-1. To be consistent with the NCCLS definition of effective growth inhibition (MIC90), the growth of isolates was graphed relative to the growth controls. Figure 4 demonstrates growth curves for the AMB-susceptible and -resistant isolates by using three parameters to measure growth: MFI (panel a), the OD (panel b), and viability (panel c). The MIC90 of the susceptible isolate, measured by both FCM assay and the NCCLS method, was 0.5 μg/ml, which is comparable to the drug concentration that yields 90% reduction in CFU. There was no reduction in the CFU, MFI, or OD in the resistant isolate at any AMB concentration tested (up to 8 μg/ml).

FIG. 4.

Growth curves obtained by multiple methods. Growth curves for the AMB-susceptible (black squares) and AMB-resistant (gray diamonds) isolates relative to the growth control, as measured by MFI (a), OD (b), and viability (c), were determined.

AMB MICs of 27 randomly selected isolates were compared by using the FCM and NCCLS methods (Table 1). The results obtained by both methods were highly comparable.

TABLE 1.

AMB MICs obtained by the FCM and NCCLS methods

| Isolate | AMB MIC (μg/ml)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| NCCLS | FCM | |

| A. fumigatus | ||

| F13C1 | 1 | 1 |

| F13E6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| F14E1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| F13G6 | 1 | 1 |

| F10l8 | 1 | 1 |

| F13E9 | 1 | 1 |

| F13E4 | 0.5 | 1 |

| F13F6 | 1 | 2 |

| F14E3 | 1 | 2 |

| F14E5 | 1 | 1 |

| F5l5 | 2 | 2 |

| F5l8 | 2 | 2 |

| F5l6 | 1 | 1 |

| F5H4 | 2 | 2 |

| F5H8 | 2 | 2 |

| F8F7 | 1 | 2 |

| F7E7 | 1 | 1 |

| F816 | 1 | 1 |

| F11E9 | 1 | 1 |

| F12D8 | 1 | 1 |

| F11F7 | 1 | 2 |

| F7F1 | 1 | 2 |

| F11H8 | 1 | 2 |

| A. terreus | ||

| F12E4 | >2 | >2 |

| F3D4 | 1 | 1 |

| F14B9 | >2 | >2 |

DISCUSSION

Current methods for determining antifungal susceptibility of filamentous fungi are limited by the time required to quantify mycelial growth. The method described here analyzes the susceptibility to AMB by measuring viability and growth at an earlier cellular stage. Since preliminary experiments suggest that this method is reproducible and yields results consistent with more time-consuming serial dilution methods, it may represent an alternative mechanism to rapidly obtain susceptibility data.

Currently available methods, including the NCCLS broth dilution, E-test, and colorimetric methods, assess susceptibility by measuring hyphal growth as the overall endpoint (13, 20). Although these methods are reproducible, the clinical applicability of each is limited by the time required to obtain hyphal growth (48 to 72 h). Flow cytometry allows for the analysis of thousands of cells within seconds. Previous studies have largely focused on the development of flow cytometric assays to measure the antifungal susceptibilities of Candida species. Fluorochromes utilized include acridine orange, propidium iodide, rhodamine 123, oxonol SYBR green, and 5,6-carboxy-fluorescein diacetate (2, 5, 6, 10, 19). The fluorochrome utilized in the present study, FUN-1, was chosen because fluorescence is indicative of cellular viability, not death, allowing for potential utility in measuring the action of drugs that introduce both “cidal” and “static” effects. Also, the change in cell membrane permeability that occurs during conidial maturation does not cause nonspecific fluorescence with FUN-1, as it does with other vital dyes such as propidium iodide (11).

Recently, Lass-Florl and colleagues described a method to measure hyphal viability after exposure to triazole antifungals with the FUN-1 dye (9). The method described here builds on these studies by providing adaptations to reproducibly measure conidial viability. The FUN-1-based FCM assay requires just 4 h and can be performed from the primary culture of the causative organism. Conidia treated with concentrations of AMB in excess of the MIC are small by light scatter measurement and exhibit dim fluorescence. In contrast, the conidia of AMB-resistant isolates grow in high concentrations of drug, as assessed by both light scatter and fluorescence intensity. The MIC90 of susceptible and resistant Aspergillus isolates, calculated by the FCM method, correlate with those obtained by NCCLS methodologies. No results were discordant using the previously recommended breakpoint for resistance (2 μg/ml) (21).

In summary, the applicability of flow cytometry for antimicrobial susceptibility testing can be extended to include filamentous fungi. This FUN-1-based FCM assay clearly distinguishes susceptible and resistant isolates and is reproducible and rapid. Further studies to automate the assay and to define parameters for testing the susceptibilities of multiple different filamentous fungi to triazole and echinocandin antifungals may expand its applicability for the clinical microbiological laboratory.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by a research grant from the American Lung Association and the National Institutes of Health (K08-A101571).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartizal, K., C. J. Gill, G. K. Abruzzo, A. M. Flattery, L. Kong, P. M. Scott, J. G. Smith, C. E. Leighton, A. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, and J. Balkovec. 1997. In vitro preclinical evaluation studies with the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2326-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deere, D., J. Shen, G. Vesey, P. Bell, P. Bissinger, and D. Veal. 1998. Flow cytometry and cell sorting for yeast viability assessment and cell selection. Yeast 14:147-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 2001. In vitro fungicidal activities of voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B against opportunistic moniliaceous and dematiaceous fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:954-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrigues, J. C., G. Cadet de Fontenay, M. D. Linas, M. Lagente, and J. P. Seguela. 1994. New in vitro assay based on glucose consumption for determining intraconazole and amphotericin B activities against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2857-2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green, L., B. Petersen, L. Steimel, P. Haeber, and W. Current. 1994. Rapid determination of antifungal activity by flow cytometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1088-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirk, S. M., S. M. Callister, L. C. L. Lim, and R. F. Schell. 1997. Rapid susceptibility testing of Candida albicans by flow cytometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:358-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurtz, M. B., I. B. Heath, J. Marrinan, S. Dreikorn, J. Onishi, and C. Douglas. 1994. Morphological effects of lipopeptides against Aspergillus fumigatus correlate with activities against (1,3)-β-d-glucan synthase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1480-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lass-Florl, C., G. Kofler, G. Kropshofer, J. Hermans, A. Kreczy, M. P. Dierich, and D. Niederwieser. 1998. In-vitro testing of susceptibility to amphotericin B is a reliable predictor of clinical outcome in invasive aspergillosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lass-Florl, C., M. Nagl, C. Speth, H. Ulmer, M. P. Dierich, and R. Wurzner. 2001. Studies of in vitro activities of voriconazole and itraconazole against Aspergillus hyphae using viability staining. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:124-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao, R. S., R. P. Rennie, and J. A. Talbot. 2001. Novel fluorescent broth microdilution method for fluconazole susceptibility testing of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2708-2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marr, K., M. Khododoust, M. Black, and S. Balajee. 2001. Early events in macrophage killing of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia: development of a new flow cytometric viability assay. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:1240-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meletiadis, J., J. F. Meis, J. W. Mouton, and P. E. Verweij. 2001. Analysis of growth characteristics of filamentous fungi in different nutrient media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:478-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meletiadis, J., J. W. Mouton, J. F. Meis, B. A. Bouman, J. P. Donnelly, and P. E. Verweij. 2001. Colorimetric assay for antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3402-3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millard, P., B. Roth, H. Thi, S. Yue, and R. Haugland. 1997. Development of the FUN-1 family of fluorescent probes for vacuole labeling and viability testing of yeasts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2897-2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosquera, J., P. A. Warn, J. Morrissey, C. B. Moore, C. Gil-Lamaignere, and D. W. Denning. 2001. Susceptibility testing of Aspergillus flavus: inoculum dependence with itraconazole and lack of correlation between susceptibility to amphotericin B in vitro and outcome in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1456-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrikkou, E., J. L. Rodriguez-Tudela, M. Cuenca-Estrella, A. Gomez, A. Molleja, and E. Mellado. 2001. Inoculum standardization for antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi pathogenic for humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1345-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pina-Vaz, C., F. Sansonetty, A. G. Rodrigues, S. Costa-de-Oliveira, J. Martinez-de-Oliveira, and A. F. Fonseca. 2001. Susceptibility to fluconazole of Candida clinical isolates determined by FUN-1 staining with flow cytometry and epifluorescence microscopy. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:375-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prudencio, C., F. Sansonetty, and M. Corte-Real. 1998. Flow cytometric assessment of cell structural and functional changes induced by acetic acid in the yeasts Zygosaccharomyces bailii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cytometry 31:307-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramani, R., and V. Chaturvedi. 2000. Flow cytometry antifungal susceptibility testing of pathogenic yeasts other than Candida albicans and comparison with the NCCLS broth microdilution test. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2752-2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rex, J. H., M. A. Pfaller, T. J. Walsh, V. Chaturvedi, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, L. L. Gosey, F. C. Odds, M. G. Rinaldi, D. J. Sheehan, and D. W. Warnock. 2001. Antifungal susceptibility testing: practical aspects and current challenges. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:643-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton, D. A., S. E. Sanche, S. G. Revankar, A. W. Fothergill, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1999. In vitro amphotericin B resistance in clinical isolates of Aspergillus terreus, with a head-to-head comparison to voriconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2343-2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wenisch, C., C. B. Moore, R. Krause, E. Presterl, P. Pichna, and D. W. Denning. 2001. Antifungal susceptibility testing of fluconazole by flow cytometry correlates with clinical outcome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2458-2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada, H., S. Kohno, S. Maesaki, H. Koga, M. Kaku, K. Hara, and H. Tanaka. 1993. Rapid and highly reproducible method for antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1009-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]