Abstract

Purpose

Adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma (PHEO) presents a significant challenge due to the high incidence of early hospital readmission (ER). This study evaluated the incidence and risk factors of ER for PHEO within 30 days of adrenalectomy.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of 346 patients > 18 years with unilateral PHEO who underwent adrenalectomy between September 2012 and September 2024. The patients were categorised into ER (n = 49) and no ER (n = 297) groups. Logistic regression analyses were performed to predict risk factors for ER.

Results

The most common causes of ER were postoperative maintained hypotension (42.9%), bleeding (6.1%), ileus (24.5%), wound infection (4.1%), hyperkalemia (8.2%), pneumonia (2%), intra-abdominal abscess (2%), acute MI (4.1%), and colonic injury (6.1%). Most postoperative complications were Clavien-Dindo grade II (n = 40, 81.6%). Two perioperative deaths (4%) occurred in the ER group. Logistic regression showed that low body mass index (OR 0.849, 95% CI, 0.748–0.964; p = 0.012), tumor size < 5 cm (OR 0.096, 95% CI, 0.030–0.310; p < 0.001), and low ASA (OR 0.435, 95% CI, 0.249–0.761; p = 0.003) were associated with risk reduction for ER while malignancy (OR 5.302, 95% CI, 1.214–23.164; p = 0.027), open approach(OR 12.247, 95% CI, 5.227–28.694; p < 0.001), and intraoperative complications (OR 19.149, 95% CI, 7.091–51.710; p < 0.001) were associated with risk increase of ER.

Conclusion

Postoperatively maintained hypotension and ileus were the most common causes of ER. Low body mass index, tumour size < 5 cm, and low ASA were risk reductions for ER, while malignancy, open approach, and intraoperative complications were the independent risk increase factors.

Keywords: Laparoscopic adrenalectomy, Open adrenalectomy, Postoperative complications, Pheochromocytoma

Introduction

Pheochromocytoma (PHEO) originates from adrenomedullary cells that secrete adrenaline and noradrenaline [1]. The Clinical symptoms of tumour catecholamine overproduction range from silent to sudden death [2, 3]. Surgery for PHEO may involve either an open or laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Emerging technologies now encompass minimally invasive laparoscopic adrenalectomy (LA), which offers the benefits of excellent surgical view, precise dissection, and less tumour manipulation. It is safe feasible, and is associated with lower morbidity [4]. Gagner et al. [5] pioneered transperitoneal LA. Subsequently, numerous surgeons have advocated transperitoneal LA because of its recognisable anatomy and wide operational field [6].

Adrenal glands exhibit various anatomical relationships. The right adrenal gland lies partially behind the inferior vena cava (IVC), close to the liver and duodenum, and drains through the small right adrenal vein directly into the IVC posterolaterally. The left adrenal gland is intimately associated with the colon, pancreatic tail, and spleen and drains through the longer left adrenal vein into the left renal vein. Technical challenges can complicate adrenalectomy, thereby increasing the risk of complications [7–9]. The occurrence of postoperative complications following PHEO surgery varies between 11.4% and 29.8%, with comorbidities, tumour size, catecholamine levels, and surgical techniques correlating with an increased risk of such complications [3, 10, 11].

Various early hospital readmission (ER) risk factors have been addressed [12, 13]. Preoperative assessment of such risk factors is crucial for surgeons to determine the likelihood of ER, formulate a surgical strategy to minimise readmission rates and enhance perioperative surgical outcomes. Understanding these risk factors enables us to inform patients and include them in the decision-making process regarding surgical treatment. We have previously assessed the risk variables for intraoperative hemodynamic instability [14]. Recognising the risk factors for ER should enhance the perioperative treatment. This study assessed ER incidence and risk predictors within 30 days of PHEO surgery owing to complications.

Material and methods

The University Research Ethics Board approved the study protocol (IRB number: 10281212025) and was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06697652). This study adhered to the STROCSS Guidelines [15]. The study team did not plan prior protocols.

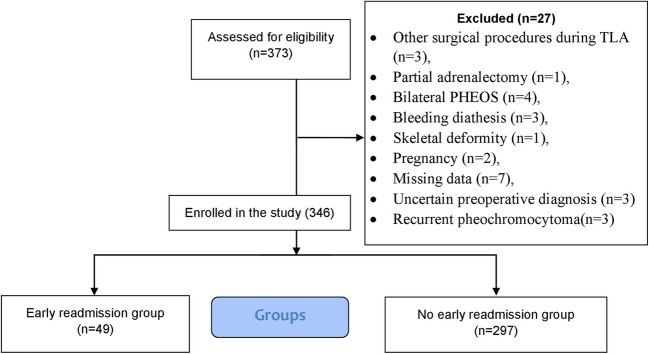

Study design and eligibility criteria: 346 consecutive patients > 18 years with unilateral PHEO (benign or malignant) who underwent open adrenalectomy or transperitoneal LA between September 2012 and September 2024 were retrospectively analysed. The patients were divided into ER (n = 49) and no ER (n = 297) groups. The diagnosis was confirmed biochemically, radiologically [16], and by postoperative pathological examination. Figure 1 illustrates a flowchart detailing the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study participants.

Fig. 1.

Flow Diagram of inclusion and exclusion criteria of studied patients

Definition of Outcomes (endpoints) and measurements: The outcomes were the incidence and predictors of ER within 30 days after adrenalectomy for PHEO. Following adrenergic receptor blockade during the pre-induction phase, blood pressure was < 130/80 mmHg, with a heart rate of < 80 beats per minute in the supine position and < 100 beats per minute in the standing position [17]. Tumor sizes were documented based on preoperative CT findings, with tumours measuring ≥ 5 cm classified as"large"[18]. Intraoperative hemodynamic instability (HDI) is characterised by systolic blood pressure (SBP) > 200 mmHg for > one minute or a mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 60 mmHg, necessitating the administration of intravenous vasopressors (norepinephrine or epinephrine) or vasodilators (nitroprusside) to sustain normal blood pressure during the procedure [19]. Maintained hypotension is defined as the requirement for continuous saline and vasopressor infusion (norepinephrine or epinephrine) to sustain a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 90 mm Hg for more than 24 h postoperatively [20]. Operative time was defined as the duration (in minutes) from skin or port-site incision to skin closure. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification was rated from I to IV [21]. The Clavien-Dindo classification was employed to assess morbidity [22]. Genetic analyses were not performed in this study.

Perioperative approaches

All patients followed a standard operating procedure (SOPS) to the guidelines [23]. All patients with PHEO received preoperative doxazosin, bunazosin [24], phenoxybenzamine [25], and atenolol (beta-blockers) [26]. As required, hypotension was controlled during and after surgery using plasma expanders or norepinephrine infusion. Open adrenalectomy [27] and transperitoneal laparoscopic adrenalectomy [28] were conducted as previously outlined. All procedures were conducted by proficient endocrine surgeons, each performing over 30 laparoscopic adrenalectomies, the requisite minimum to surmount the learning curve [29]. We conducted clipless laparoscopic adrenalectomy by occluding the adrenal arteries and veins using a harmonic scalpel (Johnson and Johnson) or LigaSure (Covidien-Medtronic) [30]. When clips were required, we used titanium clips or Hemo-lok clips (Weck Closure Systems, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). All specimens were obtained using an endoscopic pouch (U.S. Surgical, Norwalk, CT, USA) and were sent for histological analysis. Implementation of drainage is contingent on the selection of the primary surgeon. Postoperatively, all patients were admitted to the ICU and offered typical enhanced recovery protocols, including early movement and nutrition. Blood pressure was monitored in the ICU for the first 48 h postoperatively, followed by regular intervals (every 4 h) until discharge. Patients requiring vasopressors beyond 24 h were indicated for readmission.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA), employing the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for data visualisation and quantitative analysis for normality assessment. We employed the independent t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test to assess the distribution of normally and non-normally distributed quantitative variables across groups. We used the chi-square or Fisher's exact test to compare categorical data. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to predict early readmission and calculate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Only variables with a p-value < 0.25 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Three hundred forty-six patients (n = 346) were categorised into ER (n = 49) and no ER (n = 297) groups. Table 1 shows the baseline patient and tumour data. We found no significant differences between the two groups regarding the preoperative data, except for smoking(47% vs 23.6%,p < 0.001), Body Mass Index (BMI) (33.7 ± 3.2 vs 31.4 ± 3.8, P < 0.001), family history(71.4% vs 16.5%, p = 0.042), PASS score(p < 0.001), pathological type of the tumour (benign or malignant) (p = 0.049), mean tumour size(6.5 ± 1.8 vs 5.07 ± 1.3, p = < 0.001), tumour diameter > 5 cm(91.8% vs 50.5%, p < 0.001) ASA(p < 0.001), median preoperative diastolic blood pressure before alpha-blocker use [96(92–100) vs. 92(89–98), p = 0.007], median preoperative SBP after alpha-blocker use [125(119–127) vs. (120–127), p = 0.026), alpha-blocker usage(p < 0.001), median 24 h urinary metanephrine, nor metanephrine [3.8(3.25–3.9) vs 3.1(2.8–3.9), p = 0.006], and previous upper abdominal surgery(46.9% vs 12.1%, p = 0.001) for ER and no ER groups, respectively. The median patient age was 48(45–53) and 46(41.5–53) years (p = 0.22), and 8(16.3%) vs. 26(9.8%) were retrocaval PHEO (p = 0.09). The most common comorbidities were DM (28.6% vs 28.3%) and hypertension (10.2% vs 9.4%) (p = 0.690) in both groups respectively.

Table 1.

Patients and tumor characteristics in the studied groups

| Early readmission (n = 49) (%) |

No early readmission (n = 297) (%) |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(median, IQR) | 48(45–53) | 46(41.5–53) | 0.222 | |

| Sex | Male | 34(69.4%) | 186(62.6%) | 0.362 |

| Female | 15(30.6%) | 111(37.4%) | ||

| Smoker | Smoker | 23(47%) | 70(23.6%) | < 0.001* |

| Non-smoker | 26(53.1%) | 227(76.4%) | ||

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 33.7 ± 3.2 | 31.4 ± 3.8 | < 0.001* | |

| Family history of PHEO | 35(71.4%) | 49(16.5%) | 0.042* | |

| Side of PHEO | Right-sided | 17(34.7%) | 132(44.4%) | 0.202 |

| Left-sided | 32(65.3%) | 165(55.6%) | ||

| PASS score | < 4 | 6(12.2%) | 266(89.6%) | < 0.001* |

| ≥ 4 | 43(87.8%) | 31(10.4%) | ||

| Benign or malignant | Benign PHEO | 9(18.4%) | 270(90.9%) | 0.049* |

| Malignant PHEO | 40(81.6%) | 27(9.1%) | ||

| Tumor size (cm)(mean SD) | 6.5 ± 1.8 | 5.07 ± 1.3 | < 0.001* | |

| Tumor size | < 5 cm | 4(8.2%) | 147(49.5%) | < 0.001* |

| > 5 cm | 45(91.8%) | 150(50.5%) | ||

| Retrocaval PHEO | no | 41(83.7%) | 271(91.2%) | 0.09 |

| yes | 8(16.3%) | 26(9.8%) | ||

| ASA | II | 6(12.2%) | 174(58.6%) | < 0.001* |

| III | 39(79.6%) | 89(30%) | ||

| IV | 4(8.2%) | 34(11.4%) | ||

| Comorbidities | No comorbidities | 30(61.2%) | 172(57.9%) | 0.690 |

| DM | 14(28.6%) | 84(28.3%) | ||

| HTN | 5(10.2%) | 28(9.4%) | ||

| Previous MI | 0(0.00%) | 6(2%) | ||

| Previous stroke | 0(0.00%) | 7(2.4%) | ||

| CHD | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Preoperative predominant clinical symptoms | HTN | 31(63.3%) | 170(57.2%) | 0.157 |

| Sweating | 6(12.2%) | 52(17.5%) | ||

| Palpitation | 3(6.1%) | 43(14.5%) | ||

| Headache | 9(18.4%) | 32(10.8%) | ||

| Preoperative SBP (before alpha-blocker)(median, IQR) | 147(140–150) | 145(142–150) | 0.438 | |

| Preoperative DBP (before alpha-blocker))(median, IQR) | 96(92–100) | 92(89–98) | 0.007* | |

| Preoperative SBP after alpha blocker(pre-induction) (median, IQR) | 125(119–127) | 125(120–127) | 0.026* | |

| Preoperative DBP after alpha blocker(pre-induction) (median, IQR) | 77(71–78) | 77(69–79) | 0.904 | |

| Alpha blocker | Bunazocin | 1(2%) | 31(10.4%) | < 0.001* |

| Doxazocin | 29(59.2%) | 114(38.4%) | ||

| Phenoxypenzamine | 19(38.8%) | 152(51.2%) | ||

| Beta-blocker | 9(18.4%) | 43(14.5%) | 0.480 | |

| 24 h urinary epinephrine (microgram/24) (n = 0–20) (median, IQR) | 89(74–100) | 87(73–95) | 0.333 | |

|

24 h urinary nor epinephrine (microgram/24)(n = 15–80)(median, IQR) |

134(125–136) | 133(125 −134) | 0.271 | |

| 24 h urinary metanephrine and normetanephrine(mg/24)(n = 0–1.2 mg/day)(median, IQR) | 3.8(3.25–3.9) | 3.1(2.8–3.9) | 0.006* | |

| 24 h urinary VMA (n = 0–7.9 mg/day) (median, IQR) | 34(23.5–41) | 35(24–41) | 0.490 | |

| Plasma epinephrine(pg/ml)(n = 4–83 pg/ml) | 126(121–145) | 131(122–152) | 0.887 | |

| Plasma norepinephrine(pg/ml)(n = 80–498 pg/ml)(median, IQR) | 697(658–837) | 735(640–831.5) | 0.955 | |

| Previous upper abdominal surgery | 23(46.9%) | 36(12.1%) | 0.001* | |

IQR Interquartile range, PHEO Pheochromocytoma, PASS Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologist, CHD coronary heart disease, MI myocardial infarction, DM diabetes mellitus, BMI body mass index, HTN hypertension. *statistically significant

Table 2 shows intraoperative data. No statistically significant difference between the groups as regards intraoperative data except that the ER group had longer median operative time (158(136–198.5) vs 134(122–145) min, p < 0.001), more intraoperative complications (41 (83.7%) vs 1(0.3%) (p < 0.001) and higher conversion(16(32.7%) vs 11(3.7%) (p < 0.001). In this study, the most common intraoperative complication was bleeding from adrenal vein injuries in both groups. Moreover, the commonest causes of conversion were uncontrolled bleeding from the adrenal vein in the early readmission group and adhesion with difficult dissection in the no early readmission group.

Table 2.

Intraoperative data of the studied groups

| Early readmission (n = 49) (%) |

No early readmission (n = 297) (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approach(open or laparoscope) | Open | 24(49%) | 29(9.8%) | < 0.001* |

| Laparoscope | 25(51%) | 268(90.2%) | ||

| Operative time(median,IQR) | 158 (136–198.5) | 134(122–145) | < 0.001* | |

| Blood loss(ml) (median,IQR) | 230(194.5–274) | 210(187–269) | 0.163 | |

| Intraoperative hemodynamic instability | 10(20.4%) | 36(12.1%) | 0.113 | |

| Forms of intraoperative hemodynamic instability | Hypertensive crisis | 8(16.3%) | 32(10.8%) | 0.195 |

| Tachycardia(> 100 bpm) | 2(4.1%) | 4(1.3%) | ||

| Intraoperative complications | No intraoperative complications | 8(16.3%) | 296(99.7%) | < 0.001* |

| Intraoperative bleeding from adrenal vein | 20(40.8%) | 1(0.3%) | ||

| Intraoperative acidosis | 3(6.1%) | 0 | ||

| Intraoperative bleeding from IVC | 10(20.4%) | 0 | ||

| Other causes of intraoperative bleeding | 2(4.1%) | 0 | ||

| Liver injury | 4(8.2%) | 0 | ||

| Splenic injury | 1(2%) | 0 | ||

| Colonic injury | 1(2%) | 0 | ||

| Tumor rupture | 1(2%) | 13(4.4%) | 0.442 | |

| Conversion | 16(32.7%) | 11(3.7%) | < 0.001* | |

| Causes of conversion | Uncontrolled bleeding from adrenal vein | 6(12.2%) | 4(1.3%) | < 0.001* |

| Adhesion with difficult dissection | 2(4.1%) | 7(2.4%) | ||

| Uncontrolled bleeding from IVC | 1(2%) | 0 | ||

| Intraoperative recurrent hemodynamic instability | 3(6.1%) | 0 | ||

| Uncontrolled bleeding from splenic injury | 3(6.1%) | 0 | ||

| Left colonic injury | 1(2%) | 0 | ||

IQR Interquartile range, IVC Inferior vena cava. *statistically significant

Table 3 shows postoperative data. The commonest causes of early postoperative complications and ER were postoperative maintained hypotension 21(42.9%), bleeding 3(6.1%), ileus 12(24.5%), wound infection 2(4.1%), hyperkalemia4 (8.2%), pneumonia1 (2%), intra-abdominal abscess1 (2%), acute MI 2(4.1%), and colonic injury3(6.1%). The ER group is associated with a statistically significant higher median hospital stay [4(3–8.5) vs. 4(3–4), p < 0.001] and CD classification (p < 0.001). Most postoperative complications were Clavien-Dindo grade II (N = 40(81.6%), p < 0.001). There is no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding postoperative 30-day mortality (p = 0.339). There were two perioperative deaths (4%) ten days after surgery due to acute respiratory failure and myocardial infarction. Reoperation occurred in three patients who were diagnosed with postoperative colonic injury.

Table 3.

Postoperative data of the studied groups

| Early readmission (n = 49)(%) | No early readmission (n = 297)(%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital stay(median, IQR) | 4(3–8.5) | 4(3–4) | < 0.001* | |

| Early postoperative complications | Maintained hypotension | 21(42.9%) | 0(0.00%) | < 0.001* |

| Bleeding | 3(6.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Ileus | 12(24.5%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Wound infection | 2(4.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Hyperkalemia | 4(8.2%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Pneumonia | 1(2%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1(2%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Acute MI | 2(4.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Colonic injury | 3(6.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Treatment of early readmission | Conservative treatment + k losing diuretics | 4(8.2%) | 0(0.00%) | < 0.001* |

| Conservative treatment antibiotic | 2(4.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Conservative treatment blood transfusion | 3(6.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Conservative treatment cardiac support | 2(4.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Conservative treatment + IV fluid Ryle | 13(26.5%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Conservative treatment respiratory support | 1(2%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Postoperative fluid and vasopressor | 20(40.8%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Radiological drainage | 1(2%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Surgical re-intervention | 3(6.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Clavien-Dindo classification | < 0.001* | |||

| Grade I | 2(4.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Grade II | 40(81.6%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Grade III | 4(8.2%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Grade IV | 2(4.1%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Postoperative mortality(within 30 days) | No mortality | 47(96%) | 297(100%) | 0.339 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 1(2%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

| Acute MI | 1(2%) | 0(0.00%) | ||

IQR Interquartile range, MI myocardial infarction. *statistically significant

Table 4 shows full details of postoperative complications.

Table 4.

Details of causes of early readmission

| Variable | Maintained hypotension (n = 21) |

Bleeding (n = 3) |

Ileus (n = 12) |

Wound infection (n = 2) |

Hyperkalemia (n = 4) |

Pneumonia (n = 1) |

Intra-abdominal abscess (n = 1) |

Acute MI (n = 2) |

colonic injury (n = 3) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(median)(years) | 51 | 42 | 47 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 44 | 52 | 48 | |

| Sex | male | 16(76.2%) | 3(100%) | 5(41.7%) | 0(0.00%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 3(100%) |

| female | 5(23.8%) | 0(0.00%) | 7(58.3%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Smoker | smoker | 6(28.6%) | 1(33.3%) | 5(41.7%) | 1(50%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 3(100%) |

| non smoker | 15(71.4%) | 2(66.7%) | 7(58.3%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Body mass index | 35 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 35 | 37 | 23 | 31 | |

| Family history of pheos | 13(61.9%) | 1(33.3%) | 12(100%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) | |

| Side of pheo | right sided | 8(38.1%) | 2(66.7%) | 1(8.3%) | 1(50%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| left sided | 13(61.9%) | 1(33.3%) | 11(91.7%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) | |

| PASS score | ≥ 4 | 16(76.2%) | 3(100%) | 12(100%) | 2(100%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 2(66.7%) |

| < 4 | 5(23.8%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(33.3%) | |

| Benign or malignant | malignant pheo | 12(57.1%) | 3(100%) | 12(100%) | 2(100%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) |

| benign pheo | 9(42.9%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 7.6 | 7.3 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 5.8 | 5.1 | |

| Tumor size | < 5 cm | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 3(25%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| > 5 cm | 21(100%) | 3(100%) | 9(75%) | 2(100%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 3(100%) | |

| Retrocaval pheochromocytoma | no | 16(76.2%) | 1(33.3%) | 12(100%) | 2(100%) | 4(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) |

| yes | 5(23.8%) | 2(66.7%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| ASA | 2 | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(16.7%) | 1(50%) | 2(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(33.3%) |

| 3 | 19(90.5%) | 3(100%) | 8(66.7%) | 1(50%) | 2(50%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 2(66.7%) | |

| 4 | 2(9.5%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(16.7%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Comorbidities | no comorbidities | 12(57.1%) | 1(33.3%) | 7(58.3%) | 1(50%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 3(100%) |

| DM | 6(28.6%) | 2(66.7%) | 4(33.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| hypertension | 3(14.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(8.3%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| previous myocardial infarction | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| previous stroke | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| coronary heart disease | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Preoperative predominant clinical symptoms | hypertension | 18(85.7%) | 3(100%) | 6(50%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) |

| sweating | 2(9.5%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 4(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| palpitation | 1(4.8%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(8.3%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| headache | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 5(41.7%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 3(100%) | |

| preoperative SBP (before alpha blocker) | 151 | 155 | 148 | 140 | 140 | 140 | 139 | 139 | 142 | |

| preoperative DBP (before alpha blocker) | 97 | 107 | 96 | 96 | 92 | 94 | 88 | 88 | 100 | |

| preoperative SBP after alpha blocker(pre-induction) | 123 | 124 | 121 | 120 | 110 | 128 | 125 | 128 | 125 | |

| preoperative DBP after alpha blocker(pre-induction) | 75 | 79 | 76 | 69 | 71 | 77 | 71 | 70 | 73 | |

| Alpha blocker | Bunazocin | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| Doxazocin | 10(47.6%) | 2(66.7%) | 5(41.7%) | 1(50%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) | |

| Phenoxypenzamine | 11(52.4%) | 1(33.3%) | 7(58.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Beta blocker | 6(28.6%) | 1(33.3%) | 2(16.7%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| 24 h urinary epinephrine (microgram/24) (n = 0–20) | 94 | 94 | 86 | 103 | 60 | 133 | 100 | 79 | 83 | |

| 24 h urinary nor epinephrine(microgram/24)(n = 15–80) | 128 | 137 | 134 | 134 | 133 | 134 | 133 | 134 | 125 | |

| 24 h urinary metanephrine and nor metanephrine(mg/24)(n = 0–1.2 mg/day) | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 3.5 | |

| 24 h urinary VMA (n = 0–7.9 mg/day) | 32 | 34 | 38 | 38 | 34 | 24 | 36 | 21 | 24 | |

| Plasma epinephrine(pg/ml)(n = 4–83 pg/ml) | 134 | 104 | 129 | 119 | 154 | 125 | 126 | 101 | 101 | |

| Plasma nor epinephrine(pg/ml)(n = 80–498 pg/ml) | 778.52 | 714.67 | 804.25 | 687.00 | 536.00 | 689.00 | 589.00 | 658.00 | 687.00 | |

| Previous upper abdominal surgery | no | 9(42.9%) | 0(0.00%) | 5(41.7%) | 2(100%) | 4(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) |

| yes | 12(57.1%) | 3(100%) | 7(58.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Approach (open or laparoscope) | open | 7(33.3%) | 1(33.3%) | 8(66.7%) | 2(100%) | 1(25%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 1(50%) | 3(100%) |

| laparoscope | 14(66.7%) | 2(66.7%) | 4(33.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 3(75%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Operative time | 184 | 188 | 149 | 149 | 121 | 214 | 148 | 122 | 135 | |

| Blood loss(ml) | 231 | 200 | 224 | 192 | 311 | 199 | 184 | 245 | 184 | |

| Intraoperative hemodynamic instability | yes | 5(23.8%) | 2(66.7%) | 2(16.7%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| no | 16(76.2%) | 1(33.3%) | 10(83.3%) | 1(50%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) | |

| Forms of intraoperative hemodynamic instability | no | 16(76.2%) | 1(33.3%) | 10(83.3%) | 1(50%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) |

| hypertensive crisis | 5(23.8%) | 2(66.7%) | 1(8.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| tachycardia | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(8.3%) | 1(50%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Intraoperative complications | no intraoperative complications | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 3(25%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 3(100%) |

| intraoperative bleeding from adrenal vein | 20(95.2%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| intraoperative acidosis | 0(0.00%) | 3(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| intraoperative bleeding from IVC | 1(4.8%) | 0(0.00%) | 9(75%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| other causes of intraoperative bleeding | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| liver injury | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 4(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| splenic injury | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| colonic injury | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Tumor rupture | yes | 1(4.8%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| no | 20(95.2%) | 3(100%) | 12(100%) | 2(100%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) | |

| Conversion | yes | 11(52.4%) | 3(100%) | 1(8.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| no | 10(47.6%) | 0(0.00%) | 11(91.7%) | 2(100%) | 4(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) | |

| Causes of conversion | uncontrolled bleeding from adrenal vein | 2(9.5%) | 3(100%) | 1(8.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| adhesion with difficult dissection | 2(9.5%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| uncontrolled bleeding from IVC | 1(4.8%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| intraoperative recurrent hemodynamic instability | 2(9.5%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| uncontrolled bleeding from splenic injury | 3(14.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| left colonic injury | 1(4.8%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Hospital stay | 3 | 1.5(1–2) | 4.5(3–9) | 6(3–9) | 4(100%) | 6(3–9) | 3 | 9 | 7(3–12) | |

| Treatment of early complications | conservative treatment + k losing diuretics | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 4(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| conservative treatment + antibiotic | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| conservative treatment + blood transfusion | 0(0.00%) | 3(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| conservative treatment + cardiac support | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| conservative treatment + IV fluid + Ryle | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 12(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| conservative treatment + respiratory support | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| postoperative fluid and vasopressor | 21(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| radiological drainage | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| surgical re-intervention | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 3(100%) | |

| Clavien—Dindo classification | Grade 0 | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) |

| Grade I | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Grade II | 21(100%) | 3(100%) | 12(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 4(100%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Grade III | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 3(100%) | |

| Grade IV | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 100% | 0(0.00%) | 2(100%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| Postoperative mortality(30 days) | no mortality | 21(100%) | 3(100%) | 10(83.3%) | 2(100%) | 4(100%) | 100% | 100% | 2(100%) | 3(100%) |

| acute respiratory failure | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(8.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

| acute MI | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(8.3%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | |

IQR Interquartile range, PHEO Pheochromocytoma, PASS Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologist, CHD coronary heart disease, MI myocardial infarction, DM diabetes mellitus, BMI body mass index, HTN hypertension. *statistically significant

Table 5 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis for predicting ER. Multivariate Logistic regression analysis to predict ER showed that low body mass index (OR 0.849, 95% CI, 0.748–0.964; p = 0.012), tumour size < 5 cm (OR 0.096, 95% CI, 0.030–0.310; p < 0.001), and low ASA (OR 0.435, 95% CI, 0.249–0.761; p = 0.003) were associated with risk reduction for ER while malignancy (OR 5.302, 95% CI, 1.214–23.164; p = 0.027), open approach(OR 12.247, 95% CI, 5.227–28.694; p < 0.001), and intraoperative complications (OR 19.149, 95% CI, 7.091–51.710; p < 0.001) were associated with risk increase for ER.

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis to predict early readmission

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 0.971(0.934–1.009) | 0.30 | - | |

| Sex | 0.708(0.363–1.381) | 0.311 | - | |

| Low body mass index | 0.850 (0.778- 0.929) | < 0.001 | 0.849 (0.748–0.964) | 0.012* |

| PASS score | 0.637 (0.262–1.548) | 0.320 | - | - |

| Malignant PHEO | 2.838 (1.267–6.354) | 0.01 | 5.302 (1.214–23.164) | 0.027* |

| Tumour size < 5 cm | 0.096 (0.034–0.275) | < 0.001 | 0.096 (0.030–0.310) | < 0.001* |

| Low ASA | 0.449 (0.292–0.691) | < 0.001 | 0.435 (0.249–0.761) | 0.003* |

| Preoperative SBP before alpha blocker | 1.007 (0.977–1.038) | 0.642 | - | - |

| Open approach | 8.593 (4.331—17.049) | < 0.001 | 12.247 (5.227–28.694) | < 0.001* |

| intraoperative HI | 0.506 (0.232- 1.105) | < 0.001* | 1.599 (0.559–4.572) | 0.381 |

| Intraoperative complications | 0.089(0.038–0.207) | < 0.001* | 19.149(7.091–51.710) | < 0.001* |

HI Hemodynamic instability, SBP Systolic blood pressure, PASS Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score, PHEO Pheochromocytoma, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologist. *statistically significant

Discussion

This study evaluated the incidence and risk factors of ER after open and laparoscopic adrenalectomies for PHEO. The most common causes of early postoperative complications and ER were postoperative maintained hypotension in 21(42.9%) and ileus in 12(24.5%). Multivariate Logistic regression analysis to predict ER showed that low body mass index, tumour size < 5 cm and low ASA were associated with risk reduction for ER whereas malignancy, open approach, and intraoperative complications were associated with an increased risk of ER.

The incidence of postoperative complications and ER in this analysis was 14.1%, comparable to that reported in other studies [3, 11, 31]. In this study, postoperative maintained hypotension was the most common cause of ER after surgery. It represented 21/49 (42.9%) of all cases requiring ER and 6% (21/346) of patients from the entire study group, which was significantly lower than other reports that reported frequencies of hypotension after adrenalectomy for PHEO of approximately 50% [20, 32–35]. The possible reasons for this variation were variations in sample size, the definition of maintained hypotension, patient selection, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, indications, variable preoperative medical preparation [17], anaesthesia, and variations in the approaches for adrenalectomy [19]. Ileus was the second most common cause of ER in our study and was presented in 12/49 patients (24.5%) with ER and in 12/346(3.5%) patients in the overall cohort. The causes of ileus may be open surgery and postoperative hypotension, which decrease the oxygen supply to the intestine [36, 37]. Lastly, improper use of catecholamine infusion during hypotension might have decreased splanchnic blood flow[38, 39]. Patients who underwent LA had earlier bowel recovery than those who underwent OA, similar to another study [40], and the open approach was a risk factor for ER in the current study. ER due to postoperative bleeding occurred in three patients (3/346, 0.9%), which required blood transfusion. Bleeding was uncommon in our series, contradicting previous reports [13, 31]. Although patients with PHEO are at a high risk of bleeding due to the high vascularity of the tumour [41], in our study, the experienced surgeon and using recent technology of adrenalectomy helped us immensely decrease the incidence of postoperative bleeding.

PHEO surgery is commonly associated with intraoperative complications and risks [3, 42]. Adhesion to the surrounding tissue with difficult dissection of adhesive perinephric fat is common in patients with a high body mass index, which is common in left-sided PHEO surgery [43]. This may be responsible for intraoperative and postoperative colonic injuries. Logistic regression analysis confirmed that low BMI was associated with risk reduction and intraoperative complications were associated with an increased risk of ER after PHEO surgery. Tumor size has been described as a risk factor for postoperative complications after LA and PHEO surgery [13]. The larger the PHEO, the more frequent the risk of increased vascularity and adhesion to the surrounding structures. Therefore, even with skilled personnel, A PHEO may be associated with increased complications and perioperative mortalities [44]. Our institution used TLA in all scheduled adrenalectomies, regardless of tumour size, similar to previous reports [45, 46]. In the multiple regression analysis, a tumour size of < 5 cm was associated with a risk reduction for ER. Death occurred in two patients (2/49, 4.1%) of readmission in our analysis, and our results suggest the overall safety of perioperative management of patients with PHEO.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several important limitations. As a retrospective analysis, it was subject to selection bias. A single-country design may limit generalizability to other healthcare systems. Although clinically relevant, outcome definitions lack standardisation (e.g., hypotension duration and ileus criteria). Unmeasured confounders (e.g. outpatient compliance) could influence the results. Nevertheless, this is the first multi-institutional assessment of ER risk factors following PHEO adrenalectomy to identify important associations that warrant prospective validation.

Conclusions

Postoperative maintained hypotension and ileus are the most common causes of ER. Logistic regression analysis showed that low body mass index, tumour size < 5 cm and low ASA were associated with risk reductions for ER, while malignancy, open approach, and intraoperative complications were associated with increased risk. Preoperative assessment of these risk variables is crucial for surgeons and anaesthetists to determine the likelihood of ER, formulate surgical strategies, minimise admission rates, and enhance postoperative results.

Acknowledgements

No

Author contributions

Tamer. A.A.M. Habeeba, Abd Al-Kareem Elias, Abdelmonem A.M Adam, Mohamed A. Gadallah, Saad Mohamed Ali Ahmed, Ahmed Khyrallh, Mohammed H. Alsayed, Esmail Tharwat Kamel Awad, Emad A. Ibrahim, Mohamed Fathy Labib, Sobhy Rezk Ahmed Teama, Mahmoud Hassib Morsi Badawy, Mohamed Ibrahim Abo Alsaad, Abouelatta KH Ali, Hamdi Elbelkasif, Mahmoud Ali Abou Zaid, Ibtsam AbdElMaksoud Mohamed El Shamy, Boshra Ali Ali El-houseiny, Mahmoud El Azawy, Ahmed Elhoofy, Ali Hussein Khedr, Abdelrahman Mohamed Hasanin Nawar, Ahmed Salah Arafa, Ahmed Mesbah Abdelaziz, Abdelfatah H. Abdelwanis, Mostafa M Khairy, Ahmed M Yehia, Ahmed Kamal El Taher wrote the main manuscript text, prepared figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This study was funded by the FTDS in Egypt.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Ethical approval

All patients received information about their surgical procedures and signed an Informed Consent form before surgery. This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board (IRB: 10281212025) and retrospectively registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06697652). All procedures followed the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki's ethical standards and later amendments and adhered to the STROBE guidelines for observational studies.

Consent to participate and publish

Formal written consent was obtained from patients for publication purposes.

Competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sbardella E, Grossman AB (2020) Pheochromocytoma: an approach to diagnosis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 34(2):101346. 10.1016/j.beem.2019.101346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L, Zhang Y, Hu Y, Yang Z (2022) Pheochromocytoma with Takotsubo syndrome and acute heart failure: a case report. World J Surg Oncol 20(1):251. 10.1186/s12957-022-02704-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunaud L, Nguyen-Thi PL, Mirallie E, Raffaelli M, Vriens M, Theveniaud PE et al (2016) Predictive factors for postoperative morbidity after laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis in 225 patients. Surg Endosc 30(3):1051–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davey MG, Ryan ÉJ, Donlon NE, Ryan OK, Al Azzawi M, Boland MR et al (2023) Comparing surgical outcomes of approaches to adrenalectomy — a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg 408(1):180. 10.1007/s00423-023-02911-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gagner M, Lacroix A, Bolté E (1992) Laparoscopic adrenalectomy in ’ ’Cushing’s syndrome and pheochromocytoma. N Engl J Med 327:1033. 10.1056/nejm199210013271417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conzo G, Gambardella C, Candela G, Sanguinetti A, Polistena A, Clarizia G et al (2018) Single center experience with laparoscopic adrenalectomy on a large clinical series. BMC Surg 18(1):2. 10.1186/s12893-017-0333-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieder JM, Nisbet AA, Wuerstle MC, Tran VQ, Kwon EO, Chien GW (2010) Differences in left and right laparoscopic adrenalectomy. JSLS 14:369–373. 10.4293/108680810X12924466007520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cianci P, Fersini A, Tartaglia N, Ambrosi A, Neri V (2016) Are there differences between the right and left laparoscopic adrenalectomy? Our experience. Ann Ital Chir 87:242–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ippolito G, Palazzo FF, Sebag F, Thakur A, Cherenko M, Henry JF (2008) Safety of laparoscopic adrenalectomy in patients with large pheochromocytomas: a single institution review. World J Surg 32:840–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai S, Yao Z, Zhu X, Li Z, Jiang Y, Wang R et al (2018) Risk factors for postoperative severe morbidity after pheochromocytoma surgery: a single center retrospective analysis of 262 patients. Int J Surg 60:188–193. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemente-Gutiérrez U, Pérez-Soto RH, Hernández-Acevedo JD, Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Casanueva-Pérez E, Pantoja-Millán JP et al (2021) Endocrine hypertension secondary to adrenal tumors: clinical course and predictive factors of clinical remission. Langenbecks Arch Surg 406(6):2027–2035. 10.1007/s00423-021-02245-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang RY, Lang BH, Wong KP, Lo CY (2014) High preoperative urinary norepinephrine is an independent determinant of perioperative hemodynamic instability in unilateral pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma removal. World J Surg 38:2317–2323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Scholten A, Chomsky-Higgins K, Nwaogu I, Gosnell JE, Seib C et al (2018) Risk factors associated with perioperative complications and prolonged length of stay after laparoscopic adrenalectomy. JAMA Surg 153:1036–41. 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Habeeb TAAM, Araujo-Castro M, Chiaretti M, Podda M, Aiolfi A, Kryvoruchko IA et al (2024) Side-specific factors for intraoperative hemodynamic instability in laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma: a comparative study. Surg Endosc. 10.1007/s00464-024-10974-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathew G, Agha R (2021) STROCSS 2021: strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in surgery. IJS Short Reports. 6(4):e35. 10.1097/SR9.0000000000000035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaman L, Behera A, Singh R, Katariya RN (2002) Surgical management of pheochromocytomas. Asian J Surg 25(2):139–144. 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60162-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araujo-Castro M, Pascual-Corrales E, Nattero Chavez L, Martínez Lorca A, Alonso-Gordoa T, Molina-Cerrillo J et al (2021) Protocol for presurgical and anesthetic management of pheochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas: a multidisciplinary approach. J Endocrinol Invest 44(12):2545–2555. 10.1007/s40618-021-01649-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Z, Wang L, Chen J, Li X, Liu D, Cao T et al (2019) Clinical analysis of adrenal lesions larger than 5 cm in diameter (an analysis of 251 cases). World Journal of Surgical Oncology 17(1):220. 10.1186/s12957-019-1765-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vorselaars WMCM, Postma EL, Mirallie E, Thiery J, Lustgarten M, Pasternak JD et al (2018) Hemodynamic instability during surgery for pheochromocytoma: comparing the transperitoneal and retroperitoneal approach in a multicenter analysis of 341 patients. Surgery 163(1):176–182. 10.1016/j.surg.2017.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Namekawa T, Utsumi T, Kawamura K, Kamiya N, Imamoto T, Takiguchi T et al (2016) Clinical predictors of prolonged postresection hypotension after laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Surgery 159(3):763–770. 10.1016/j.surg.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haynes SR, Lawler PG (1995) An assessment of the consistency of ASA physical status classification allocation. Anaesthesia 50(3):195–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240(2):205–213. 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar SS, Collings AT, Collins C, Colvin J, Sylla P, Slater BJ (2024) Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons guidelines development: health equity update to standard operating procedure. Surg Endosc. 10.1007/s00464-024-10809-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paganini AM, Balla A, Guerrieri M, Lezoche G, Campagnacci R, D’Ambrosio G, Quaresima S, Antonica MV, Lezoche E (2014) Laparoscopic transperitoneal anterior adrenalectomy in pheochromocytoma: experience in 62 patients. Surg Endosc 28(9):2683–2689. 10.1007/s00464-014-3528-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roizen MF, Hunt TK, Beaupre PN, Kremer P, Firmin R, Chang CN, Alpert RA, Thomas CJ, Tyrrell JB, Cahalan MK (1983) The effect of alpha-adrenergic blockade on cardiac performance and tissue oxygen delivery during excision of pheochromocytoma. Surgery 94:941–945 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Filpo G, Parenti G, Sparano C, Rastrelli G, Rapizzi E, Martinelli S et al (2023) Hemodynamic parameters in patients undergoing surgery for pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma: a retrospective study. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 21(1):192. 10.1186/s12957-023-03072-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mihai R (2019) Open adrenalectomy. Gland Surg 8(Suppl 1):S28-s35. 10.21037/gs.2019.05.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Ranea A, Delisau O, Planellas-Giné P, Cornejo L, Pujadas M et al (2020) Three-dimensional (3D) system versus two-dimensional (2D) system for laparoscopic resection of adrenal tumors: a case-control study. Langenbecks Arch Surg 405(8):1163–1173. 10.1007/s00423-020-01950-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goitein D, David G, Mintz Y, Yoav M, Gross D, Reissman P (2004) Laparoscopic adrenalectomy: ascending the learning curve. Surg Endosc 18:771–773. 10.1007/s00464-003-8830-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santingamkun A, Panumatrassamee K, Kiatsopit P (2017) Clipless laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Asian Biomed 11(2):157–162 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma L, Yu X, Huang Y (2023) Risk factors for postoperative complications after pheochromocytoma and/or paraganglioma: a single-center retrospective study. Front Oncol 13:1174836. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1174836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sprung J, OʼHara JF Jr, Gill IS, Abdelmalak B, Sarnaik A, Bravo EL (2000) Anesthetic aspects of laparoscopic and open adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Urology 55:339–343 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Gao X, Yamazaki Y, Pecori A, Tezuka Y, Ono Y, Omata K et al (2020) Histopathological analysis of tumor microenvironment and angiogenesis in pheochromocytoma. Front Endocrinol 11:587779. 10.3389/fendo.2020.587779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kong H, Li N, Tian J, Li XY (2020) Risk predictors of prolonged hypotension after open surgery for pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. World J Surg 44:3786–3794. 10.1007/s00268-020-05706-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen WT, Grogan R, Vriens M, Clark OH, Duh QY (2010) One hundred two patients with pheochromocytoma treated at a single institution since the introduction of laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Arch Surg 145:893–897. 10.1001/archsurg.2010.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD et al (2012) Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 33:255167. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brady K, Hogue CW (2013) Intraoperative hypotension and patient outcome: does “one size fit all?” Anesthesiol 119:495–497. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a10cce [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkman E, Kaukonen KM, Pettilä V, Kuitunen A, Varpula M (2013) Association between inotrope treatment and 90-day mortality in patients with septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 57(4):431–442. 10.1111/aas.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue T, Manley GT, Patel N, Whetstone WD (2014) Medical and surgical management after spinal cord injury: vasopressor usage, early surgery and complications. J Neurotrauma 31(3):284–291. 10.1089/neu.2013.3061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pisarska M, Pędziwiatr M, Budzyński A (2016) Perioperative hemodynamic instability in patients undergoing laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Gland Surg 5(5):506–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dickson PV, Alex GC, Grubbs EG, Ayala-Ramirez M, Jimenez C, Evans DB et al (2011) Posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy is a safe and effective alternative to transabdominal laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Surgery 150:452–458. 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu S-Q, Wang S-Y, Chen Q, Liu Y-T, Li Z-L, Sun T (2020) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for pheochromocytoma: a meta-analysis. BMC Surg 20(1):167. 10.1186/s12893-020-00824-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kira S, Sawada N, Nakagomi H, Ihara T, Furuya R, Takeda M, Mitsui T (2022) Mayo adhesive probability score is associated with the operative time in laparoscopic adrenalectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 32(6):595–599. 10.1089/lap.2021.0459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aydın YM, Günseren KÖ, Çiçek MÇ, Aslan ÖF, Gül ÖÖ, Cander S et al (2024) The effect of mass functionality on laparoscopic adrenalectomy outcomes. Langenbecks Arch Surg 409(1):212. 10.1007/s00423-024-03409-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gan L, Meng C, Li K, Lei P, Li J, Wu J et al (2022) Safety and effectiveness of minimally invasive adrenalectomy versus open adrenalectomy in patients with large adrenal tumors (≥5 cm): A meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Surg 104:106779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arolfo S, Giraudo G, Franco C, Parasiliti Caprino M, Seno E, Morino M (2022) Minimally invasive adrenalectomy for large pheochromocytoma: not recommendable yet? Results from a single institution case series. Langenbecks Arch Surg 407(1):277–283. 10.1007/s00423-021-02312-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.