Abstract

Developing effective treatments for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) likely requires a deep understanding of molecular mechanisms. Integration of transcriptomic datasets and developing innovative computational analyses may yield novel molecular targets with broad applicability. The motivation for this study was conceived from two main observations: (a) most transcriptomic analyses of AD data consider univariate differential expression analysis, and (b) insights are often not transferable across studies. We designed a machine learning-based framework that can elucidate interpretable multivariate relationships from multiple human AD studies to discover robust transcriptomic AD biomarkers transferable across multiple studies. Our analysis of three human hippocampus datasets revealed multiple robust synergistic associations from unrelated pathways along with inconsistencies of gene associations across different studies. Our study underscores the utility of developing AI-assisted next-gen metrics for integration, robustness, and generalization and also highlights the potential benefit of elucidating molecular mechanisms and pathways that are important in targeting a single population.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Multivariate analysis, Machine learning, RNA sequencing, Transcriptomics, KCNIP1

Subject terms: Computational science, Neurodegenerative diseases, Learning algorithms

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a complex neurodegenerative disorder characterized by amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and progressive cognitive decline1. This disorder poses a true public health challenge due to its increasing prevalence among the growing aging population. Recently, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has emerged as a dominant, powerful gene expression quantification technique. Transcriptomic analyses have provided critical revelations into biological mechanisms that underlie AD pathology. Typically, in AD, RNA transcripts responsible for immune response are upregulated, whereas pathways related to synaptic transmission and cell-to-cell signaling are downregulated2,3. The analysis of RNA-Seq data commonly uses tools such as edgeR4 and DESeq25, which implement univariate statistical tests such as differential expression (DE) analysis. These univariate statistical tests rank gene relevance according to their significance (p-value) and fold change (FC). Transcriptomic studies typically apply differential expression analysis due to its scalability, robustness, and interpretability, which are crucial aspects for identifying new gene-based biomarkers6. However, beyond comparing DE analysis, emerging new studies have begun to demonstrate the importance of multivariate methods for exploring the AD transcriptomic landscape7–12.

Multivariate methods using typical machine learning (ML) approaches have been gaining ground in disease classification and have shown to perform well in AD13. For instance, Random Forest (RF) based methods can render classification accuracy of 91.6%14 and correlation-based feature selection followed by Support Vector Machines (SVM) can achieve 94% accuracy15 using transcriptomic data. Under specific scenarios with increased number of features, even scores in the 99% accuracy range have been reported16. However, an increasing number of features in a machine learning model can lead to over-fitting. Moreover, neural network-based classifiers can obtain accuracy scores above 90%9, although interpretation is limited.

In this paper, we designed and report the results of AD classification using simpler bivariate models, resulting in more interpretable and robust gene-based biomarkers. We considered classification using transcriptomic data to arrive at a set of novel, gene-based biomarkers that can potentially be used for targeted therapeutic development.

The hippocampus is known to be a critical region of the brain when it comes to AD17. In typical AD progression, this area is affected very early on, showing rapid atrophy rates18. The dysfunction spreads to surrounding tissues, eventually leading to generalized loss of neuronal activity and collapse of critical mechanisms in the brain. Most studies focus on specific regions of the brain, for instance Park et al. (2018) analyze gene expression profiles from the prefrontal cortex (PFC)14, while Zhang et al. (2013) worked with the cerebellum and the visual cortex19. The prefrontal cortex is also known to be dysregulated, particularly in the case of late-onset AD3.

There are limited studies in the literature regarding the integrated analysis of multiple AD datasets to elucidate robust biomarkers, particularly in the human hippocampus. Validating results from multiple studies is vital for capturing nuances in different populations and verifying promising gene-based biomarkers before constructing hypotheses and investigating their underlying biological mechanisms. Typically, validating results from different datasets involves checking the directionality of the fold change in DE analysis, while observing statistical requirements, such as false discovery rates. Multivariate non-parametric models lack concepts of directionality, fold change and statistical significance. Therefore it is imperative to be cautious when drawing conclusions from such models.

The current manuscript considers the design of a robust machine learning pipeline to analyze hippocampus transcriptomic datasets from three independent studies using two different measuring approaches: RNA-Seq and microarray. The insights gained from the analysis are described, along with caveats in interpretation and applicability. We also considered pathway analysis to explore the biological relevance of the results learned from the integrated analysis of the three datasets. Finally, the robustness of the inferred biomarkers were evaluated by simulating the experiments with permuted datasets to create the null distribution of feature importance scores.

This article is organized as follows. Section “Results” provides a description of the results of the analysis. Section “Discussion” provides a discussion of the results and the gathered insights. The methods used in the manuscript are provided in section “Methods”.

Results

Our study utilizes three datasets, two of which employ RNA-Seq and one that employs microarray technology. The first is an RNA-Seq gene expression dataset provided by van Rooij et al. (2019)20 and shall be henceforth referred as VR. The second is also an RNA-Seq dataset, part of the Mayo Clinic Hippocampal Vulnerability Study21 and shall be referred as MAYO dataset. The third dataset is the only one that comes from microarray analysis and is obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus, identifier GSE293782, and will be referred as GSE dataset. The three datasets were selected prioritizing the region of the brain where the tissue was extracted. The data collection and preprocessing techniques are documented in section “Datasets”. The demographic data, DE expression results and directionality of fold change are explained in the Supplementary Information, but are not included in the main text due to our study not relying on DE analysis.

Data visualization

The plotted Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projections (UMAPs) in Supplementary Fig. S1 before and after the feature selection indicate better class separation between case and control samples after application of feature selection as compared to without feature selection. The same pattern is observed using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), as shown in Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3, respectively.

Bivariate analysis

The results of applying the bivariate analysis using SVMs are presented in Fig. 1, which displays a pixelated visualization of the gene pairs performances across the three different datasets in a color-coded fashion. This visual representation serves to display the superiority of the top 10 ranked genes from our bivariate ranking approach. Each pixel’s intensity represents a score obtained from training an SVM. In the monochromatic panels (a, b, c) the pixel intensity corresponds to the cross-validation accuracy of a gene pair in a single dataset. Panels (a, b, c) illustrate that there are numerous pairs with high scores in VR—primarily red pixels in (a)—as compared to MAYO and GSE (large number of black pixels denoting low accuracy in (b) and (c). Note that there are substantially more black pixels in GSE as compared to MAYO). The polychromatic panel (d) displays the performance across all three datasets by combining the monochromatic panels additively, shown for only the top 10 ranked genes. Most gene combinations present pink colored pixels, which encode a dominance of high scores in VR (red). The gene SLC38A2 displays more beige colored pixels, which encode a more balanced combination of scores. By assessing the accuracy of gene pairs in multiple datasets, we can identify biomarkers that are not only highly accurate but also generalizable across different populations and conditions.

Fig. 1.

RGB-encoded visualization of bivariate gene pair accuracy scores. This figure presents a visual representation of accuracy scores from all possible combinations of the top 10 ranked genes in our bivariate ranking, using an RGB-encoded pixel format. In panels (a)–(c), the accuracy scores for each hippocampal dataset—VR, MAYO, and GSE—are depicted in distinct color schemes: red for VR, green for MAYO, and blue for GSE. Panel (d) merges these representations additively. A pixel with a white color indicates a perfect accuracy score across all three datasets, signifying robust gene pair performance. The diagonal encodes the combination of a gene with itself and is not relevant for this analysis.

Among the three datasets, we observe that the average performance of a gene pair selected in one dataset tends to be lower when tested in other datasets, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. The average CV score for gene pairs selected from the VR dataset is 0.89, while the average performance of these same gene pairs is 0.63 in the MAYO dataset and 0.57 in the GSE dataset, significantly lower with  measured by a Welch’s t-test. This disparity reveals potential dataset-specific variations in gene expression patterns. The significantly higher CV scores in the VR dataset compared to MAYO and GSE highlight the importance of considering multiple datasets to capture a more comprehensive view of the disease. Analysis performed using only a single transcriptomic dataset might fail to encompass the entire panorama of Alzheimer’s Disease due to limited sample sizes and differences in population characteristics. For example, the VR dataset includes reads from the Netherlands Brain Bank, while the MAYO dataset contains reads from the Mayo Clinic Florida Brain Bank. To address this, we evaluated the performance of gene pairs across all three datasets, providing a more robust and generalizable assessment of gene pair relevance, following the approach from Fig. 2.

measured by a Welch’s t-test. This disparity reveals potential dataset-specific variations in gene expression patterns. The significantly higher CV scores in the VR dataset compared to MAYO and GSE highlight the importance of considering multiple datasets to capture a more comprehensive view of the disease. Analysis performed using only a single transcriptomic dataset might fail to encompass the entire panorama of Alzheimer’s Disease due to limited sample sizes and differences in population characteristics. For example, the VR dataset includes reads from the Netherlands Brain Bank, while the MAYO dataset contains reads from the Mayo Clinic Florida Brain Bank. To address this, we evaluated the performance of gene pairs across all three datasets, providing a more robust and generalizable assessment of gene pair relevance, following the approach from Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Considered approach for ranking gene importance in Alzheimer’s disease from multiple datasets. This figure illustrates the methodologies employed for ranking gene importance using bivariate and multivariate approaches across hippocampal transcriptomic datasets. Bivariate ranking methodology is used to exhaustively search for top performing gene pairs. All pairs from the top 500 genes from Relief feature selection (124,750) are evaluated across three hippocampal transcriptomic datasets. The accuracy scores above the 0.70 threshold are added up, producing a bivariate ranking.

To demonstrate the advantages of bivariate analysis over univariate differential expression analysis, we present the fold changes of the top genes identified by the bivariate methodology in Supplementary Table S1. This table lists the aggregated scores from the top-ranked genes based on our bivariate ranking methodology, along with their respective fold changes in each of the three hippocampal studies. A key observation is that many of the top bivariate genes are not unanimously differentially expressed in all three datasets and would have been potentially overlooked if differential expression analysis alone was used. For instance, KCNIP1, the top-ranked gene from our bivariate analysis, demonstrates high aggregated scores across the datasets, showcasing its relevance despite not being consistently differentially expressed in univariate analysis. This highlights the innate difference between our bivariate methodology, which captures gene interactions and their combined effects, and the commonly accepted univariate approach of differential expression analysis, which evaluates each gene in isolation.

The differences between DE analysis and the bivariate analysis is further shown in the Supplementary Information. The volcano plot displayed in Supplementary Fig. S5 shows the statistical significance of the differential expression analysis of the two RNA-Seq gene expression profiles. The volcano plot in Supplementary Fig. S6 displays the statistical significance of the differential expression analysis in the microarray study. The location of the top 10 ranked genes in the volcano plots reveals that most of them are not significantly differentially expressed in MAYO and GSE.

Potential biomarkers

Among the top scoring genes, we highlight KCNIP1 ( ), CA10 (

), CA10 ( ), CSPG5 (

), CSPG5 ( ), BCL6 (

), BCL6 ( ) and SCG3 (

) and SCG3 ( ). The bivariate gene ranking remains the same when perturbing the 0.70 threshold. We also observed that SLC7A2 (

). The bivariate gene ranking remains the same when perturbing the 0.70 threshold. We also observed that SLC7A2 ( ) and CMTM4 (

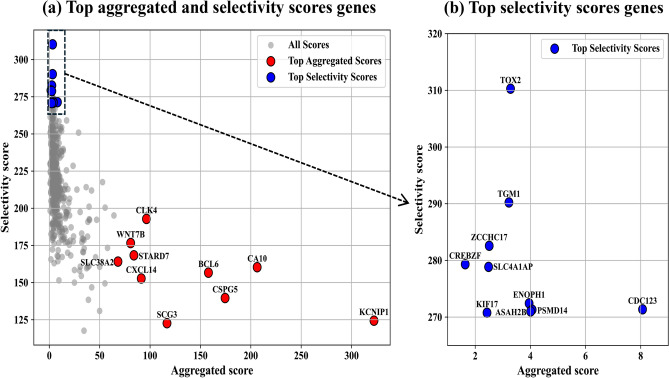

) and CMTM4 ( ) were only present when selecting the top 500 genes from Relief in MAYO. The top genes selected through aggregated and selectivity scores across three datasets are shown in Fig. 3.

) were only present when selecting the top 500 genes from Relief in MAYO. The top genes selected through aggregated and selectivity scores across three datasets are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot of aggregated scores vs. selectivity scores for gene pairs. This scatter plot presents the relationship between aggregated scores and selectivity scores for gene pairs in our bivariate analysis. The aggregated score, plotted on the x-axis, reflects the robustness of gene pair performance across multiple hippocampal datasets, with higher scores indicating consistent accuracy across VR, MAYO, and GSE datasets. The selectivity score, shown on the y-axis, measures the discrepancy in performance across these datasets, with higher selectivity scores indicating greater variability.

In VR, most of the genes in our bivariate ranking perform well by themselves, obtaining 90% accuracy scores or higher without being paired to any other gene. As an exception, the genes RLBP1, BRINP3, C17orf58, TRIB1 and SHISA4 have poor accuracy scores individually, but perform considerably better when paired with other genes.

In MAYO, the top genes from our ranking are not able to split the classes by themselves and gain considerable accuracy when combined in pairs. Particularly, SCG3, CLK4, STARD7 and WNT7B obtain accuracy scores below 0.70 if we used a univariate approach. The same pattern can be observed in GSE with the following genes: BCL6, SCG3, CXCL14 and WNT7B. These genes are not differentially expressed in some studies like MAYO and GSE, but show more consistent performance when paired with other genes.

Supplementary Fig. S7 shows an example of a robust gene pair of KCNIP1 and SLC38A2 across three datasets. The performance of this pair is higher in VR and MAYO datasets while being slightly lower in GSE. Furthermore, the slopes of the decision boundary shows the importance of both the genes for classification in the VR and MAYO whereas limited gain is achieved from adding SLC38A2 to KCNIP1 in GSE dataset. This variation could be due to the different sample distributions in the dataset or due to the technology used (microarray for GSE as opposed to RNA-Seq for VR and Mayo).

Supplementary Fig. S8 shows an example of a more dataset-dependent gene pair of RBP1 and WNT7B. The gene pair provides perfect separation in the VR dataset but poor separation in the MAYO dataset and relatively lower separation in GSE.

Robustness analysis

We observed a high level of agreement between the list of genes selected before and after adding the noise (Kendall Rank Correlation coefficient of  ). Similar agreement in rankings were observed in our bivariate analysis pipeline (

). Similar agreement in rankings were observed in our bivariate analysis pipeline ( ).

).

The rank correlation coefficient  for the rankings using thresholds 0.7 and 0.65 (

for the rankings using thresholds 0.7 and 0.65 ( ) and between the rankings using thresholds 0.70 and 0.75 (

) and between the rankings using thresholds 0.70 and 0.75 ( ). These findings suggest that our rankings demonstrate robustness across different threshold choices, indicating consistent outcomes regardless of the specific threshold used.

). These findings suggest that our rankings demonstrate robustness across different threshold choices, indicating consistent outcomes regardless of the specific threshold used.

The majority of the randomized aggregated scores are close to zero, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S9. For visualization, we selected the top 10 randomized aggregated scores from permutation testing and compared them with the actual aggregated scores. As shown in Fig. 4, even the smallest actual aggregated score (for gene SLC38A2 at 68.16) is almost on pair with the largest randomized aggregated score (for gene SDHB at 76.62). All other actual aggregated scores exceed the randomized scores. Given the total of 100,000 randomized aggregated scores, these results indicate the possibility of observing the actual aggregated scores by chance is very low ( for gene SLC38A2 and

for gene SLC38A2 and  for the other genes).

for the other genes).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of actual and randomized aggregated scores. This figure presents histograms of the top 10 actual (red) and randomized (blue) aggregated scores. Randomized scores represent a quantified version of the null hypothesis, obtained by permuting the actual labels 200 times and repeating the bivariate score computation. These randomized scores help assess the statistical significance of the original ranking. By comparing the performance of the genes identified in the original analysis to these randomized scores, we can evaluate the likelihood that the original ranking occurred by chance. The top 10 randomized aggregated scores were selected from a distribution of 100,000 randomized scores. The histograms show that the genes from the original analysis, particularly KCNIP1, which is the top-ranked gene, perform significantly better than top-ranked genes in the randomized scenario. This indicates that the original ranking is statistically significant and that KCNIP1’s high rank is not due to random chance.

Discussion

Transcriptomic data may have multiple interpretations, depending on the tissue being analyzed and the technique applied to extract gene expression. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) data has the advantage of being more general than microarray data, as microarray experiments require a priori strands of cDNA for the analysis. In this multi-study, two datasets—VR and MAYO—were extracted using modern NGS techniques, while the last dataset—GSE—applies microarray. Microarrays rely on pre-designed probes, limiting their ability to detect less abundant genes. Furthermore, microarray technology has to deal with a limited range and suffers from background noise. In contrast, RNA-Seq offers an unbiased approach by sequencing all RNA molecules present in a sample.

Differential expression results for each of the three hippocampal transcriptomic datasets vary substantially in terms of fold change; however, the directionality of the most significant genes remains the same. The assumptions of differential expression analysis may not align with the objectives of machine learning, where predictive performance relies on capturing diverse patterns beyond fold changes in gene expression. One novel aspect of our study is that univariate feature selection approaches, such as Relief-F, manage to extract genes that are not significantly differentially expressed but seem to have undiscovered associations with AD. Focusing on gene pairs, rather than individual genes, the application of Relief-F produces a set of genes of interest that further diverges from conventional DE analysis and incorporates potential synergistic relationships among genes, providing potential therapeutic targets for future research. The contrast between Relief-F and conventional DE analysis is further displayed in Supplementary Table S2, which shows that among the 500 selected genes from applying Relief-F in VR transcriptomes, only 22% of those are considered significantly differentially expressed.

Another aspect of AD classification tasks lie on the kind of data being used for model training. Note that MRI image based classification approaches have shown to achieve higher accuracy as compared to transcriptomic analysis22–24. This is likely due to the fact that AD affects brain memory and has a strong impact on brain volume. Using gene expression data for AD classification tasks presents both opportunities and limitations. AD is a complex disorder in which the relationships between cause and effect are often intertwined. Dysregulation of the transcriptome struggles to tell apart the underlying molecular mechanisms from the compensatory responses of the body. AD is typically characterized by extracellular deposition of amyloid  (A

(A ) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, combined with a progressive decline of neuronal function25. This triggers a strong response from the brain, indicated by the upregulation of genes related to immune response activation.

) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, combined with a progressive decline of neuronal function25. This triggers a strong response from the brain, indicated by the upregulation of genes related to immune response activation.

The identification of potential gene-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease through our robust machine learning pipeline reveals the potential for uncovering undocumented insights into AD pathogenesis. We further evaluated the robustness of our approach through multiple approaches and arrived at some potential new biomarkers for AD. The discovery of these novel associations highlights the importance of continuing research efforts to explore the complex interactions between genetic modifications and neurodegenerative diseases. Further investigation and validation of these novel associations are essential for advancing our understanding of AD and expanding the scope of transcriptomic research in the context of neurodegenerative disorders. We developed approaches to determine applicability across datasets and observed highly differentiating behavior using multiple gene pairs in one dataset which were not replicated in the other datasets. The limited applicability of some gene pairs may offer insights into molecular mechanisms and targets that may be applicable to only one population, which could be a new frontier in precision medicine.

Identifying prognostic gene pairs using transcriptomic data presents several challenges and caveats that need careful consideration. The inherent complexity and variability of transcriptomic data can lead to both promising discoveries, but also potential misinterpretations.

One interesting result is the observation of synergistic associations between gene pairs that don’t belong to the same biological pathway. For instance, the genes KCNIP1 and SLC38A2 have shown combined association with AD, despite these genes not being traditionally linked through the same biological processes. This might suggest the existence of a novel pathway or an intricate network of interactions that implicates both genes in the progression of AD. Such findings can open new avenues for research, hinting at undiscovered mechanisms that contribute to the disease. However, it requires further validation and functional studies to confirm these interactions and elucidate their roles in AD pathology.

KCNIP1 belongs to the family of voltage-gated potassium channel-interacting proteins (KCNIPs) that regulate the A-type currents and neuronal excitability in response to changes in intracellular calcium26. KCNIP1 was nominated as an AD gene in 2018 by Dr. Rima Kaddurah-Daouk (Duke AMP-AD team). KCNIP1 interacts directly with the N-terminal domain of Kv4 channels, modulating its cell surface expression and function27. Distinct from its effects on Kv4.2-mediated channels, KCNIP1 accelerates the inactivation of Kv4.1 channels and causes a depolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of activation, highlighting the complex and subtype-specific nature of KCNIP1’s regulatory effects on Kv4 channels27. In the absence of KCNIP1 expression, Kv4 channels aggregate and misfold, and are consequently retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for degradation28. Kv4.1 downregulation has been shown in the dentate gyrus of AD mouse model, accompanied by granule cell hyperexcitability and impaired cognitive performance29. These findings suggest a potential role for KCNIP1 in human AD2,30. KCNIP1 knockout mice also exhibited increased susceptibility to seizures, as demonstrated by enhanced anxiety-like behavior and altered GABAergic neurotransmission31. Beyond its role in channel regulation, KCNIP1 has emerged as a calcium-dependent transcriptional repressor. This function involved binding to a specific DNA sequence known as the Downstream Regulatory Element (DRE) sites, which are typically located in the promoter region of the target gene32.

CA10, also known as carbonic anhydrase X, is a metalloenzyme containing zinc necessary for ion transport across cellular membranes33. CA10 can bind to all neurexin isoforms with high affinity34. Neurexins are a family of cell adhesion proteins in the neuronal presynaptic terminal. These proteins have been shown to play a role in synaptogenesis by interacting with postsynaptic ligands, such as neuroligins or leucine-rich-repeats transmembrane proteins (LRRTMs)35. A oligomers disrupt neurexin function, potentially contributing to synaptic dysfunction and cognitive decline in AD36,37. CA10 has no well-established association with AD.

oligomers disrupt neurexin function, potentially contributing to synaptic dysfunction and cognitive decline in AD36,37. CA10 has no well-established association with AD.

DeWitt et al. (1993)38, demonstrated that CSPG5 is present in both senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the hallmark pathological feature of AD. The researchers used immunohistochemical techniques to identify CSPG5 in brain tissue samples from AD patients38. Genome-wide comparison of gene expression in CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus revealed that CSPG5 transcript is downregulated in advanced AD2. A recent experimental study conducted on middle-aged mice focused on the effects of memantine, a drug used in AD treatment and suggested that memantine regulates CSPG5 biosynthesis and degradation in the hippocampus39. This regulation was associated with increased densities of newborn granule cells and improved mice’s short- and long-term memory performance39. Importantly, when CSPG5 was pharmacologically depleted, the cognitive benefits of memantine were impaired, suggesting that CSPG5 is essential for the drug’s effects39.

BCL6 (B-cell lymphoma 6) is a transcriptional repressor that plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and other B-cell malignancies40 As a master regulator of germinal center (GC) B-cell development, BCL6 facilitates the physiological genomic instability required for antibody affinity maturation40. Recent findings demonstrated that BCL6 may protect against amyloid- -induced neuronal damage AD41. Their study found that overexpression of BCL6 in SH-SY5Y cells attenuated A

-induced neuronal damage AD41. Their study found that overexpression of BCL6 in SH-SY5Y cells attenuated A -42-induced increases in p-Tau levels and improved cell viability, suggesting that NCL6 can be established as a potential target for mitigating A

-42-induced increases in p-Tau levels and improved cell viability, suggesting that NCL6 can be established as a potential target for mitigating A -related pathology in AD41. Researchers investigated the expression pattern of BCL6 in normal human brains and AD42. They found that BCL6 is expressed in isolated cortical neurons, cerebellar granule cells, scattered glial cells, and some cells of ependyma and choroid plexus42. However, BCL6 expression was absent in neurofibrillary tangles and the nuclei of cells associated with amyloid plaques in AD brains42.

-related pathology in AD41. Researchers investigated the expression pattern of BCL6 in normal human brains and AD42. They found that BCL6 is expressed in isolated cortical neurons, cerebellar granule cells, scattered glial cells, and some cells of ependyma and choroid plexus42. However, BCL6 expression was absent in neurofibrillary tangles and the nuclei of cells associated with amyloid plaques in AD brains42.

Secretogranin III (SCG3) plays a role in producing and moving dense-core secretory vesicles and is widely expressed in neuroendocrine tissues and the central nervous system. In Parkinson’s Disease (PD) research, SCG3 is upregulated in astrocytes exposed to Parkinsonian toxins such as MPTP (1-methyl-1.2.3.6.-tetrahydropyridine), a major synthetic neurotoxin, suggesting its involvement in astrocyte activation and neuroinflammatory process43. In AD, dopamine levels and receptors are significantly reduced, particularly in the striatum and hippocampus44. The decrease in SCG3-Positive secretory granules observed in dopamine neurons in PD models suggests a potentially similar mechanism in AD, where impaired vesicle trafficking could contribute to reduced dopamine signaling.

CLK4 belongs to the family of cdc2-like kinases (CLKs) containing four isoforms namely CLK1, CLK2, CLK3 and CLK4. CLK1 has been considered as a potential target for Alzheimer’s disease drug development45. The dysregulation of the processes regulated by CLKs has been linked to various diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, inflammatory diseases, viral replication, and cancer46.

CXCL14 (C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 14) is a chemokine involved in immune system regulation and inflammation, and emerging research suggests it may play a role in Alzheimer’s disease. For instance, CXCL14 may influence microglial behavior47 and indirectly affecting AD progression48. Furthermore, prior research points to the the expression of CXCL14 by single-bouquet cells in layer I (LI) of the somatosensory cortex during development of mice and loss of CXCL14 can cause increased intrinsic excitability and neuronal complexity49.

STARD7 is a lipid transport protein that facilitates the transfer of phosphatidylcholine to mitochondria. Impaired mitochondrial function has been considered as a contributing factor to neurodegenerative diseases50. Specifically, mutations in the STARD7 gene have been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegenerative diseases51,52.

WNT7b is a member of the WNT gene family, which consists of structurally related genes that encode secreted signaling proteins. A substantial amount of prior research links the Wnt signaling pathway to synaptic regulation and cognitive functions, indicating that disruptions in this pathway may contribute to cognitive decline and linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. Notably, changes in the expression of critical Wnt pathway components have been observed in the brains of both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients and animal models, reinforcing the idea that the pathway is dysregulated in AD53.

SLC38A2, also known as SNAT2, functions as a sodium-dependent amino acid transporter that mediates the neuronal efflux of neural  -amino acids across the blood-brain barrier and their uptake into neurons54. SLC38A2 was identified as one of the genes associated with selective hippocampal vulnerability in AD21. Notably, this upregulation was not confined to the hippocampus alone but was observed across multiple brain regions examined in the study21. Under hyperosmotic stress, SLC38A2 expression is significantly upregulated in an NF-

-amino acids across the blood-brain barrier and their uptake into neurons54. SLC38A2 was identified as one of the genes associated with selective hippocampal vulnerability in AD21. Notably, this upregulation was not confined to the hippocampus alone but was observed across multiple brain regions examined in the study21. Under hyperosmotic stress, SLC38A2 expression is significantly upregulated in an NF- B-dependent manner, and its overexpression attenuated cell death in medullary collecting duct cells21. Various AD-related factors, including amyloid-

B-dependent manner, and its overexpression attenuated cell death in medullary collecting duct cells21. Various AD-related factors, including amyloid- peptides and oxidative stress, also trigger NF-

peptides and oxidative stress, also trigger NF- B activation55, suggesting its potential influence on SLC38A2 expression56. Correlation analysis and received operating characteristic (ROC) curves have verified SLC38A2 as a possible key target associated with AD immunity57. SLC38A2 is also observed to create a steep concentration gradient for amino acids, particularly glutamine58. As a glutamine transporter, SLC38A2 serves an important role in maintaining amino acid homeostasis in the brain59. Glutamine is essential for neurotransmitter synthesis, particularly for the production of glutamate and GABA, which are crucial for cognitive function60. Dysfunction in SLC38A2 expression could potentially disrupt this balance, leading to alterations in neurotransmitter levels and signaling pathways that are critical for normal brain function59. The observation of an association between KCNIP1 and SLC38A2 may strengthen an association between hyperexcitability (KCNIP1) and neuroinflammation (SLC38A2).

B activation55, suggesting its potential influence on SLC38A2 expression56. Correlation analysis and received operating characteristic (ROC) curves have verified SLC38A2 as a possible key target associated with AD immunity57. SLC38A2 is also observed to create a steep concentration gradient for amino acids, particularly glutamine58. As a glutamine transporter, SLC38A2 serves an important role in maintaining amino acid homeostasis in the brain59. Glutamine is essential for neurotransmitter synthesis, particularly for the production of glutamate and GABA, which are crucial for cognitive function60. Dysfunction in SLC38A2 expression could potentially disrupt this balance, leading to alterations in neurotransmitter levels and signaling pathways that are critical for normal brain function59. The observation of an association between KCNIP1 and SLC38A2 may strengthen an association between hyperexcitability (KCNIP1) and neuroinflammation (SLC38A2).

A caveat that should be noted is the inconsistency of gene associations across different datasets. For example, while the gene pair RBP1 and WNT7B may exhibit distinct distribution patterns and a strong association with AD in VR (Supplementary Fig. S8), these findings do not replicate in MAYO, even though both datasets are derived from the same brain region. This variability can arise from several factors, including differences in sample preparation and patient demographics. Such discrepancies highlight the importance of replicating findings in multiple, independent datasets to ensure the robustness and generalization of the results.

While the identification of prognostic gene pairs using transcriptomic data holds great potential for understanding the complexities of Alzheimer’s Disease, there is still much room for improvement. Synergistic associations between genes from unrelated pathways could point to novel, uncharacterized pathways involved in AD, calling for deeper investigation. Conversely, the inconsistency of results across different datasets highlights the need for rigorous validation and replication across studies.

Methods

Datasets

This study integrates transcriptomic data from three independent datasets: VR, MAYO, and GSE, each of which was processed using distinct methodologies. The demographic data of each dataset is in Supplementary Table S3.

The VR dataset consists of RNA-Seq data obtained from hippocampal samples of 20 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cases and 10 cognitively normal controls. The RNA sequencing was conducted using an Illumina HiSeq2000 platform with a paired-end read length of 2  50 base pairs (bp). Data processing involved trimming, alignment, and transcript quantification against the GENCODE reference genome (version date; 2013-12-05). The original authors identified and removed two samples in the AD group deemed as outliers through Principal Component Analysis. We’re left with 10 samples in the control group and 18 samples in the AD group.

50 base pairs (bp). Data processing involved trimming, alignment, and transcript quantification against the GENCODE reference genome (version date; 2013-12-05). The original authors identified and removed two samples in the AD group deemed as outliers through Principal Component Analysis. We’re left with 10 samples in the control group and 18 samples in the AD group.

The MAYO dataset contains bulk RNA-Seq hippocampus data, extracted from a postmortem cohort selected by a single neuropathologist21. Specifics on hippocampus tissue section are not included in the metadata. The MAYO hippocampus data is available through the AD Knowledge Portal, identified as syn32141161. The raw sequence files can be obtained through agreement to the project’s data-specific terms of use. The MAYO dataset includes RNA-Seq profiles from 55 hippocampal samples, representing different AD subtypes and control cases. The 55 samples are distributed as follows: 15 cognitively normal controls, 10 hippocampal sparing AD, 10 limbic predominant AD and 20 considered typical AD cases. RNA was extracted, followed by ribosomal RNA depletion and library preparation. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform, generating paired-end reads of 2  101 bp. Unlike the VR dataset, which we analyzed using preprocessed data, the raw reads from the MAYO study were processed de novo in this study using the DNASTAR software. Reads were mapped to the hg38 human genome assembly, and expression values were calculated in terms of Reads per Kilobase per Million (RPKM). Differential expression analysis applied a fold change threshold

101 bp. Unlike the VR dataset, which we analyzed using preprocessed data, the raw reads from the MAYO study were processed de novo in this study using the DNASTAR software. Reads were mapped to the hg38 human genome assembly, and expression values were calculated in terms of Reads per Kilobase per Million (RPKM). Differential expression analysis applied a fold change threshold  and a significance threshold of

and a significance threshold of  , with subsequent false discovery rate (FDR) correction. The patients with extreme phenotype diagnosis were disregarded for this study and only the patients with typical AD diagnosis were accounted for our analysis, resulting in a cohort of 20 typical AD cases with 15 controls.

, with subsequent false discovery rate (FDR) correction. The patients with extreme phenotype diagnosis were disregarded for this study and only the patients with typical AD diagnosis were accounted for our analysis, resulting in a cohort of 20 typical AD cases with 15 controls.

The third hippocampal transcriptomic dataset, which we will refer to as GSE, comes from a microarray transcriptomic study by Miller et al. (2013)2, available in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus, accessible through Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Series GSE293782,61. This study encompasses gene expression in advanced stage AD versus nondemented control patients in annotated regions CA1 and CA3. According to Miller et al. (2013), the CA1 region showed more significant gene differential expression. The GSE dataset is the only study that presents spatial annotation regarding the specific section of the hippocampus where the tissue was extracted. The GSE dataset (GSE29378) comprises microarray-based gene expression data obtained from hippocampal subfields. For this study, we focused exclusively on the CA1 region, as the original publication reported stronger differential gene expression in this subfield. Gene expression was profiled using the Illumina HumanHT-12 v3 Expression BeadChip, which covers over 25,000 genes. After quality control and outlier removal, 63 samples (31 AD and 32 control) remained in the analysis. Data preprocessing involved probe filtering based on expression levels, annotation status and redundancy, ultimately resulting in 17,128 unique gene expression profiles.

The analysis workflow considered in this paper is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Workflow for biomarker discovery and pathway analysis across multiple studies. The process begins with (a) visualization of data from multiple studies (Study 1—VR, Study 2—MAYO, and Study 3—GSE). It proceeds with (b) the application of filtering approaches and (c) the training of predictive models using techniques such as SVM (d) Model performance is evaluated across all studies, with thresholds applied to performance metrics. Gene importance is computed, followed by the ranking and visualization of genes based on their performance and importance. The workflow includes robustness analysis and permutation testing to ensure the reliability of results.

UMAPs

To illustrate the importance of feature selection, we considered the representation of the entire multidimensional dataset in a lower dimensional manifold using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) and plotted the entire transcriptome data mapped to a lower manifold in Supplementary Fig. S1a–c before any feature selection. We then selected the top 500 ranked genes using filter feature selection approach Relief-F with its hyperparameter k set to 362,63 and projected the multidimensional data once again in Supplementary Fig. S1d–f.

Bivariate ranking using SVMs

For classification tasks, we utilized Support Vector Machines that are used to find the optimal hyperplane that separates different classes and minimizes classification error. We considered the exhaustive evaluation of all gene pairs from the 500 genes selected by the filter feature selection approach Relief-F. In order to evaluate the 124,750 gene pairs, we used SVM as a wrapper method to systematically assess each pair’s predictive power. We used linear SVMs in this scenario due to their robustness against overfitting and high interpretability. From the top 500 Relief-F genes from VR dataset, we exhaustively looked for the best gene pair in the reduced feature space by training linear SVMs ( ) and computing its corresponding cross-validation score (

) and computing its corresponding cross-validation score ( ) in each of our three hippocampal datasets. Keeping the gene pairs with CV scores above

) in each of our three hippocampal datasets. Keeping the gene pairs with CV scores above  , we’re left with 3428 gene pairs. At last, the scores for each gene were added up to rank the most relevant genes in bivariate classification of AD. The same process was repeated for the top 500 genes from MAYO and GSE. The aggregated score is the sum of the cross-validation scores from training SVMs across all three datasets. To ensure robustness, a threshold of 0.70 CV score was applied to exclude low-performing pairs before summing the scores.

, we’re left with 3428 gene pairs. At last, the scores for each gene were added up to rank the most relevant genes in bivariate classification of AD. The same process was repeated for the top 500 genes from MAYO and GSE. The aggregated score is the sum of the cross-validation scores from training SVMs across all three datasets. To ensure robustness, a threshold of 0.70 CV score was applied to exclude low-performing pairs before summing the scores.

Feature selection

Differential expression analysis considers the importance of individual genes for categorizing the various groups and might miss out on the multivariate relationships that can differentiate the different classes. However, using all genes to categorize the different classes is also not an optimal solution. In fact, the sheer number of features compared to the small number of samples in transcriptomics poses a well-known machine learning problem called curse of dimensionality, where the performance increases with the number of features until it achieves a peak and then starts diminishing with further increase in dimensionality64. Consequently, machine learning approaches that are trained using all genes are often prone to overfitting and lack generalization power. Thus, we considered feature selection approaches to narrow down the genes being used for classification. We used Relief65 for initially reducing the number of genes. We also considered LASSO as a feature selector, are included in the Supplementary Information.

Robustness analysis

We explored the robustness of our methodology in three different ways: Noise injection, where additive noise is added to the data and the variation in the gene ranking observed; Robustness to threshold selection and Permutation test, where permuted data labels are used to analyze the statistical significance of the gene ranking scores.

Noise injection

We investigated the robustness of our feature selection methodology, Relief-F, by injecting Gaussian additive noise with a standard deviation set to 0.05 times each gene expression’s standard deviation.

Threshold selection

To evaluate the robustness across different threshold choices, we compared three different choices of threshold by computing the Kendall Rank Correlation  for the rankings using different thresholds. We evaluated the thresholds 0.65, 0.70 and 0.75 for bivariate ranking of the 500 selected genes from VR and evaluated the correlation between each ranking, taking into account its position in the rank as well as its score.

for the rankings using different thresholds. We evaluated the thresholds 0.65, 0.70 and 0.75 for bivariate ranking of the 500 selected genes from VR and evaluated the correlation between each ranking, taking into account its position in the rank as well as its score.

Permutation test

We performed permutation tests to assess the statistical significance of the aggregated scores for the top genes discovered by the bivariate ranking. For each permutation, we randomly shuffled the data labels and recalculated the bivariate ranking. We carried out a total of 200 permutations, resulting in 100,000 (200 permutations multiplied by 500 genes per permutation) randomized aggregated scores.

Selectivity

The selectivity is computed by taking the difference between the maximum and minimum CV scores obtained for each gene pair across the datasets. To enhance the sensitivity of this metric to score variations, we square each individual CV score before computing the difference. Specifically, for a given gene pair, let  ,

,  , and

, and  represent the CV scores in the VR, MAYO, and GSE datasets, respectively. The selectivity metric

represent the CV scores in the VR, MAYO, and GSE datasets, respectively. The selectivity metric  is then defined as:

is then defined as:

|

1 |

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 AG073826. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

F.T, J.L, and R.P. formulated the problem and conceived the experiments. F.T., Y.M., and C.S-V conducted the experiments and F.T, C. S-V and R.P. drafted the manuscript. C.S. assisted with the data pre-processing. J.L. and N.K included the biological insights. F.T., J.L and R.P analyzed the results. All authors approve the final manuscript.

Data availability

The VR dataset analysed during the current study is available in https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S0197458018303877-mmc2.xlsx20. The MAYO data that supports the findings of this study is available from the AD Knowledge Portal https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org/, study syn32141161, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available21. The GSE dataset analysed during the current study is available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Series GSE29378 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE293782,61.

Code availability

The code used to run the analyses is available through Zenodo (10.5281/zenodo.13685511).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

J. Josh Lawrence, Email: john.lawrence@ttuhsc.edu.

Ranadip Pal, Email: Ranadip.Pal@ttu.edu.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-01017-y.

References

- 1.Kumar, A., Singh, A. & Ekavali. A review on Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology and its management: an update. Pharmacol. Rep.67(2), 195–203 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Miller, J. A., Woltjer, R. L., Goodenbour, J. M., Horvath, S. & Geschwind, D. H. Genes and pathways underlying regional and cell type changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med.5(5), 48 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams, J. B., Cao, Q. & Yan, Z. Transcriptomic analysis of human brains with Alzheimer’s disease reveals the altered expression of synaptic genes linked to cognitive deficits. Brain Commun.3(3), 1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edger: A bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics26(1), 139–140 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15(12), 12 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang, P., Hao, H. & Liu, C. Feature selection revisited in the single-cell era. Genome Biol.22(1), 12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li, L., Weinberg, C. R., Darden, T. A. & Pedersen, L. G. Gene selection for sample classification based on gene expression data: Study of sensitivity to choice of parameters of the GA/KNN method. Bioinformatics17(12), 1131–1142 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nanni, L., Brahnam, S. & Lumini, A. Combining multiple approaches for gene microarray classification. Bioinformatics28(8), 1151–1157 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adiwijaya, U. N. W., Lisnawati, E., Aditsania, A. & Kusumo, D. S. Dimensionality reduction using principal component analysis for cancer detection based on microarray data classification. J. Comput. Sci.14(11), 1521–1530 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyunjin, P., Seungyeoun, L., Ye Jin, K., Myung-Sook, C. & Taesung, P. Multivariate approach to the analysis of correlated RNA-Seq data. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 1783–1786 (2016).

- 11.Knight, J., Ivanov, I., Triff, K., Chapkin, R. S. & Dougherty, E. R. Detecting multivariate gene interactions in RNA-SEQ data using optimal Bayesian classification. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform.15(2), 484–493 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranjan, B. et al. DUBStepR is a scalable correlation-based feature selection method for accurately clustering single-cell data. Nat. Commun.12(1) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Ahmed, H., Alarabi, L., El-Sappagh, S., Soliman, H. & Elmogy, M. Genetic variations analysis for complex brain disease diagnosis using machine learning techniques: Opportunities and hurdles. PeerJ7, e697 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park, C., Kim, J. R., Kim, J. & Park, S.-H. Machine learning-based identification of genetic interactions from heterogeneous gene expression profiles. PLoS One13(7), e0201056 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tejeswinee, K., Shomona, G. J. & Athilakshmi, R. Feature selection techniques for prediction of neuro-degenerative disorders: A case-study with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Procedia Comput. Sci.115, 188–194 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mostafa, M., Hamid, A. E., Mabrouk, M. S. & Omar, Y. M. K. Developing an early predictive system for identifying genetic biomarkers associated to Alzheimer’s disease using machine learning techniques. Biomed. Eng. Appl. Basis Commun.31(05), 1950040 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakshmisha Rao, Y. et al. Hippocampus and its involvement in Alzheimer’s disease: A review. 3 Biotech12(2), 2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Josephs, K. A. et al. Rates of hippocampal atrophy and presence of post-mortem TDP-43 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A longitudinal retrospective study. Lancet Neurol.16(11), 917–924 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, B. et al. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell153(3), 707–720 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Rooij, J. G. J. et al. Hippocampal transcriptome profiling combined with protein-protein interaction analysis elucidates Alzheimer’s disease pathways and genes. Neurobiol. Aging74, 225–233 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crist, A. M. et al. Transcriptomic analysis to identify genes associated with selective hippocampal vulnerability in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun.12(1), 4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Shehri, W. A. Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and classification using deep learning techniques. PeerJ Comput. Sci.8, e1177 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrarini, L. et al. Ventricular shape biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease in clinical MR images. Magn. Reson. Med.59(2), 260–267 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chitradevi, D. & Prabha, S. Analysis of brain sub regions using optimization techniques and deep learning method in Alzheimer disease. Appl. Soft Comput.86, 105857 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh, R., Kaur, N., Dhingra, N. & Kaur, T. Protein misfolding, ER stress and chaperones: An approach to develop chaperone-based therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Neurosci.133(7), 714–734 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pruunsild, P. & Timmusk, T. Structure, alternative splicing, and expression of the human and mouse KCNIP gene family. Genomics86(5), 581–593 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura, T. Y. et al. Different effects of the Ca2+-binding protein, KChIP1, on two Kv4 subfamily members, Kv4.1 and Kv4.2. FEBS Lett.499(3), 205–209 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le-Yi, W., Song, Y.-J., Zhang, C.-L. & Liu, J. KV channel-interacting proteins in the neurological and cardiovascular systems: An updated review. Cells12(14), 1894 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, K.-R. et al. Impaired pattern separation in Tg2576 mice is associated with hyperexcitable dentate gyrus caused by Kv4.1 downregulation. Mol. Brain14(1), 62 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akila Dharshini, S., Sanz-Ros, J., Pan, J., Tang, W., Vallejo, K., Otero-Garcia, M. & Cobos, I. Molecular signatures of resilience to Alzheimer’s disease in neocortical layer 4 neurons, unpublished (2024).

- 31.Xiong, H., Xia, K., Li, B., Zhao, G. & Zhang, Z. KChIP1: A potential modulator to GABAergic system. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin.41(4), 295–300 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Néant, I. et al. Kcnip1 a Ca2+-dependent transcriptional repressor regulates the size of the neural plate in Xenopus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res.1853(9), 2077–2085 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aspatwar, A., Tolvanen, M. E. E. & Parkkila, S. Phylogeny and expression of carbonic anhydrase-related proteins. BMC Mol. Biol.11(1), 25 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterky, F. H. et al. Carbonic anhydrase-related protein CA10 is an evolutionarily conserved pan-neurexin ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.114(7), E1253–E1262 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez, A. M., Traunmüller, L. & Scheiffele, P. Neurexins: Molecular codes for shaping neuronal synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.22(3), 137–151 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

36.Cvetkovska, V. et al. Neurexin-

mediates the synaptogenic activity of amyloid precursor protein. J. Neurosci.42(48), 8936–8947 (2022).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

mediates the synaptogenic activity of amyloid precursor protein. J. Neurosci.42(48), 8936–8947 (2022).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 37.Medina-Samamé, A. et al. Role of neurexins in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci.43(23), 4194–4196 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeWitt, D. A., Silver, J., Canning, D. R. & Perry, G. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans are associated with the lesions of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol.121(2), 149–152 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maeda, S. et al. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan is a potential target of memantine to improve cognitive function via the promotion of adult neurogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol.179(20), 4857–4877 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bunting, K. L. & Melnick, A. M. New effector functions and regulatory mechanisms of BCL6 in normal and malignant lymphocytes. Curr. Opin. Immunol.25(3), 339–346 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

41.Lin, Y. et al. miR-6076 targets BCL6 in SH-SY5Y cells to regulate amyloid-

-induced neuronal damage. J. Cell. Mol. Med.27(24), 4145–4154 (2023).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-induced neuronal damage. J. Cell. Mol. Med.27(24), 4145–4154 (2023).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 42.Baron, B. W. & Pytel, P. Expression pattern of the BCL6 and ITM2B proteins in normal human brains and in Alzheimer disease. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol.25(7), 489–496 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhan, X., Wen, G., Jiang, E., Fengrui Li, X. W. & Pang, H. Secretogranin III upregulation is involved in parkinsonian toxin-mediated astroglia activation. J. Toxicol. Sci.45(5), 271–280 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan, X. et al. Dopamine and dopamine receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci.11, 175 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jain, P. et al. Human cdc2-like kinase 1 (clk1): A novel target for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Drug Targets15(5), 539–550 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song, M., Pang, L., Zhang, M., Qu, Y., Laster, K. V. & Dong, Z.. Cdc2-like kinases: Structure, biological function and therapeutic targets for diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther.8(1) (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Li, Z., Li, Y. & Jiao, J. Neural progenitor cells mediated by h2a.z.2 regulate microglial development via cxcl14 in the embryonic brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.116(48), 24122–24132 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujikawa, R. & Tsuda, M. The functions and phenotypes of microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Cells12(8), 1207 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iannone, A. F. et al. The chemokine cxcl14 regulates interneuron differentiation in layer i of the somatosensory cortex. Cell Rep.43(8), 114531 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johri, A. & Beal, M. F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.342(3), 619–630 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu, J., Jiang, Q., Mao, W., Zhong, S., Sun, H. & Mao, K. Stard7 could be an immunological and prognostic biomarker: From pan-cancer analysis to hepatocellular carcinoma validation. Discov. Oncol.15(1) (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Flores-Martín, J., Reyna, L., Ridano, M. E., Panzetta-Dutari, G. M. & Genti-Raimondi, S. Suppression of stard7 promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress and induces ros production. Free Radic. Biol. Med.99, 286–295 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riise, J., Plath, N., Pakkenberg, B. & Parachikova, A. Aberrant wnt signaling pathway in medial temporal lobe structures of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm.122(9), 1303–1318 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffmann, T. M. et al. Effects of sodium and amino acid substrate availability upon the expression and stability of the SNAT2 (SLC38A2) amino acid transporter. Front. Pharmacol.09, 63 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

55.Snow, W. M. & Albensi, B. C. Neuronal gene targets of NF-

B and their dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci.9, 118 (2016).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

B and their dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci.9, 118 (2016).

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 56.Sun, E., Motolani, A., Campos, L. & Tao, L. The pivotal role of NF-kB in the pathogenesis and therapeutics of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23(16), 8972 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li, Y., Shi, H., Chen, T., Xue, J., Wang, C., Peng, M. & Si, G. Establishing a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA)-immunoregulatory network associated with the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Transl. Med. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Menchini, R. J. & Chaudhry, F. A. Multifaceted regulation of the system A transporter Slc38a2 suggests nanoscale regulation of amino acid metabolism and cellular signaling. Neuropharmacology161, 107789 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kui, W. et al. SLC38A2 promotes cell proliferation and invasion by promoting glutamine metabolism in adenomyosis. Exp. Ther. Med.27(5), 218 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chunxiu, D. et al. Neutral amino acid transporter SLC38A2 protects renal medulla from hyperosmolarity-induced ferroptosis. eLife12, e80647 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Edgar, R. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res.30(1), 207–210 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kira, K. & Rendell, L. A. The feature selection problem: Traditional methods and a new algorithm. In National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 129–134 (1992).

- 63.Urbanowicz, R. J., Meeker, M., La Cava, W., Olson, R. S. & Moore, J. H. Relief-based feature selection: Introduction and review. J. Biomed. Inform.85, 189–203 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Devroye, L., Györfi, L. & Lugosi, G. A Probabilistic Theory of Pattern Recognition (Springer, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kononenko, I. Estimating attributes: Analysis and extensions of relief. In Machine Learning: ECML-94 (eds Bergadano, F. & De Raedt, L.) 171–182 (Springer, 1994). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The VR dataset analysed during the current study is available in https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S0197458018303877-mmc2.xlsx20. The MAYO data that supports the findings of this study is available from the AD Knowledge Portal https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org/, study syn32141161, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available21. The GSE dataset analysed during the current study is available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Series GSE29378 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE293782,61.

The code used to run the analyses is available through Zenodo (10.5281/zenodo.13685511).