Abstract

Background

Singing bowl has traditionally been utilized to promote healing and relaxation. This systematic review aimed to analyze all available clinical evidence, and determine any beneficial or adverse effects of singing bowl in any population.

Methods

Databases searched included PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, PsyINFO, CINAHL, CNKI, VIP, Wanfang, Sinomed from database inception to July 2024. Clinical studies of singing bowl therapy, regardless of research type, population, and intervention were included. The risk of bias of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was assessed using the Cochrane tool. Data from randomized trials were analyzed and presented as the mean difference with 95 % confidence interval, and the results from two or more separate trials with same study type that evaluated similar populations, interventions, comparisons and outcomes were statistical pooled using meta-analysis by Stata.16 software.

Results

Nineteen clinical studies originated from eight countries and published between 2008 and 2024 were identified. Half were RCTs (9), the remainder included case series studies (7), randomized crossover studies (2) and non-RCT (1). Evidence showed that singing bowl has been applied to a wide range of conditions, including the elderly, surgery, Parkinson's disease, pain, cancer, neurological function, sleep disorder, depression, anxiety, autism spectrum disorder, as well as physiological and psychological function, and it has mainly focused on outcomes related to mental health.

Conclusion

Singing bowl may have potential to alleviate anxiety, depression, improve quality of sleep and cognitive function in various patient groups, and change autistic behavior. It also shows potential benefits in physiological improvements like electroencephalography.

Protocol registration

PROSPERO, CRD42025639808.

Keywords: Singing bowl therapy, Systematic review, Anxiety, Depression, Clinical Studies

1. Introduction

The bowl-shaped instrument called singing bowl can be made of various metals, including copper, tin, zinc, iron, silver, gold, and nickel, and is played by hitting or rubbing its edges with wooden or leather mallets. Different frequencies of sound can be produced by hitting singing bowls with different materials and sizes. Originating in Tibet, China, it was initially utilized by Tibetan Buddhist monks to conduct religious rites, and sometimes for healing.1 In the 1970s, a Dutch psychotherapist named Hans De Back, who was suffering severe pain due to ankylosing spondylitis, discovered this instrument. Surprisingly, he found singing bowl could help him relax and relieve pain. Inspired, he transformed this discovery into a therapeutic modality according to the Tibetan health and rehabilitation theory, leading to its widespread development.1 As a type of vibroacoustic therapy, the singing bowl therapy generates vibration on the body surface and emits sounds of varying frequencies depending on the material and size of bowls. It provides a combination of vibration, music listening combined providing a therapeutic interaction. The use of singing bowls can be regarded as a kind of complementary and alternative therapy that combines medicine, psychology and musicology.

With the increasing acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine and integrative medicine worldwide, music therapy is also becoming increasingly popular. In 2022, the Chinese government included music therapy in medical insurance, and recommended that it could be used to improve the physical, mental, and cognitive function of people with specific conditions, such as autism. As a type of music therapy, singing bowl therapy has been reported by previous studies to have some beneficial effects on various diseases, such as Parkinson's disease,2 autism spectrum disorder,3 and insomnia.4 The potential mechanism of how singing bowl therapy works can be explained by several theories. In traditional Chinese medicine, singing bowl therapy is a type of Chinese medicine five-tone therapy, which considers that different sounds generated by different sizes of singing bowls correspond to different internal organs. According to Ayurvedic medicine, the different overtones of the singing bowl can correspond to different chakras.5 Modern research has found that singing bowls apply the frequencies of music in the form of vibrations to various parts of the body, including muscles, bones, and nerves, while simultaneously stimulating brainwaves and inducing bodily resonance.6 A previous study revealed that singing bowl induced the body into a state of deep relaxation by inhibiting the function of the human prefrontal lobe.7

An increasing number of clinical studies have documented that singing bowl therapy has been applied to different conditions in various forms of intervention. However, these studies vary in research types, methodological quality, complexity and heterogeneous features, which have not yet been comprehensively reviewed and analysed. Therefore, it is necessary to synthesize the current evidence and analyse data related to singing bowl therapy characteristics by conducting a systematic review. This review aims to search for and analyse all available clinical evidence on singing bowl therapy to determine the evidence base and provide an overview of this field, and determine any beneficial or adverse effects of singing bowl therapy in any population. Furthermore, we aim to disseminate research findings, identify research gaps, and make recommendations for future research.

2. Method

This study was a systematic review of clinical studies conducted and reported in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions8 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement9 (Supplement 1). This review has been registered in the International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), with an ID of CRD42025639808.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

The clinical studies included in this systematic review were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) Participants were those who received singing bowl therapy, without restrictions on age, gender, nationality, ethnicity, conditions, or diseases. 2) All styles and forms of singing bowl therapy were eligible, with no limitations on number of sessions and frequency. Interventions combining singing bowl therapy with other treatments with singing bowl therapy as the main component were also included. 3) There were no restrictions on the types of comparisons. No treatment, wait-list control, usual care, and other forms of control were all eligible for inclusion. 4) Outcomes related to mental health, such as depression, anxiety, quality of sleep, quality of life, were eligible for primary outcomes. The secondary outcomes included heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, pain, electroencephalograph, and safety. 5) All types of clinical study designs were eligible for inclusion, e.g., randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case control studies, case series studies, single-arm trials, and case report studies. This broad approach ensured a comprehensive assessment of the available evidence on the effects of singing bowl therapy across diverse populations and research methodologies. We excluded clinical studies if they were duplicated or reported incomplete data.

2.2. Search strategy

A search was conducted for all published clinical studies and grey literatures with no language or publication restrictions. Two researchers independently conducted the search in nine English and Chinese databases including PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, PsyINFO, CINAHL, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biomedical Literature Service System (SinoMed), Chinese Scientific Journals Database (VIP), and the Wanfang Database from their inception to July 2024 by two researchers (CYQ and LYB) independently. The search term in English databases was “singing bowl,” in Chinese databases was “song-bo.” Apart from the free term search, we conducted an additional subject term search as well. However, no indexed terms were found for singing bowl. In addition, the reference lists of all identified studies were manually searched for additional studies. The search strategies are given in Supplement 2.

2.3. Study selection

The related studies were selected by two researchers (CYQ and LYB) independently using the Reference manager software EndNote (version 20). After removing duplicates, irrelevant studies were excluded by screening the titles and abstracts, followed by a more thorough reviewing of full texts. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus with involvement of a third author (LJP). In addition, we screened the reference lists of all the included studies to supplement the additional eligible studies. The selection procedure is shown in a PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for selection of studies.

2.4. Data extraction

A predefined table was used for data extraction. The extracted data included author, country, language, publication year, type of studies, sample size, characteristics of participants, details of intervention and comparison, outcomes and results. Two authors extracted data independently (CYQ and ZXY). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author (LJP).

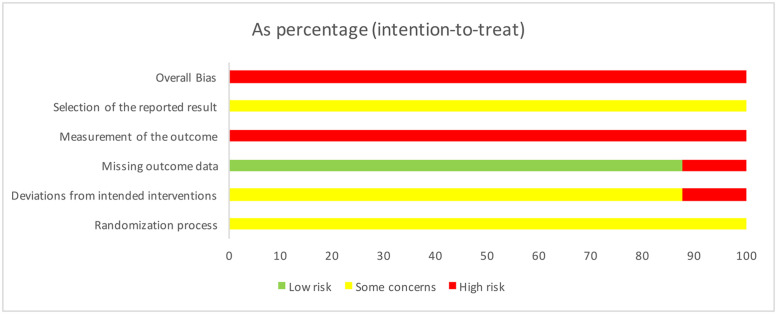

2.5. Quality assessment

The risk of bias of RCTs was assessed by applying the Version 2 of the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias in RCT (RoB 2)10 by two researchers (CYQ and ZXY) independently. The assessment of potential bias was conducted across five critical domains: 1) randomization process, 2) deviations from intended interventions, 3) missing outcome data, 4) measurement of outcomes and 5) selection of the reported result. The risk of bias judgments for each domain are “low risk of bias,” “some concerns,” or “high risk of bias.” The response options for an overall risk of bias judgment are the same as for individual domains. The overall risk of bias generally corresponds to the worst risk of bias in any of the domains.10 When applying the RoB 2, the tool can automatically recommend an overall risk of bias result when the judgment for each domain is completed.

2.6. Data synthesis and analysis

Descriptive statistics analyses, encompassing frequency and count distributions of the characteristics of the included studies, were performed to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research on singing bowl therapy. We planed to perform meta-analyses for studies with two or more groups, such as RCTs, non-randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, according to different study types to quantify the effects of singing bowl therapy. The results from two or more separate trials with same study type that evaluated similar populations, interventions, comparisons and outcomes were statistical pooled using meta-analysis by Stata.16 software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Data were summarised using mean difference (MD) with 95 % confidence interval (CI) for continuous outcomes and risk ratio (RR) with 95 % CI for dichotomous outcomes. When included studies used different instruments to measure the same outcome, standardised mean difference (SMD) was applied as the summary statistic in the meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity among the studies was evaluated using the I² statistic. For meta-analysis, a random-effects model was employed unless the statistical heterogeneity was found to be low (I² < 25 %), in which case a fixed-effects model was utilized. When the I² > 75 %, indicating considerable heterogeneity among the studies, we deemed it inappropriate to proceed with meta-analysis. In accordance with Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,8 when suitable data are unavailable for meta-analysis or when meta-analyses are deemed inappropriate, it is still possible to examine these domains to provide a systematic assessment of the available evidence. Therefore, even when the results from trials could not be statistically combined due to insufficient data or obvious clinical diversity, we continue to emphasize the importance of these results in the overall summary of evidence. Consistent with the PRISMA statement,9 we performed secondary statistics on these results reported in individual trials using Stata.16 software to present the effect estimates and their precision based on MD/RR with CI. This approach not only enhances the precision of these results, but also serves as a way to verify the findings reported in the trials.8

3. Result

3.1. Study selection

A total of 152 records were identified through database searching, and after removal of duplicates, irrelevant and non-clinical studies, 39 eligible full-text articles remained. Finally, 19 studies2, 3, 4,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 published between 2008 and 2024 were included in this review as displayed in the flowchart in Fig. 1.

3.2. Characteristics of the included studies

Nineteen clinical studies on singing bowls published between 2008 and 2024 were identified.2, 3, 4,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Thirteen published in English, five in Chinese and one in German. These studies originated from eight different countries, five were conducted in China,2, 3, 4,11,13 five in America,14,18,21,24,25 three in India,19,23,26 two in Austria,16,17 one in Germany,22 one in Chile,12 one in Korea,20 and one in Italy.15 Of the nineteen studies, nine were RCTs (47 %),2, 3, 4,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 two were randomized crossover studies (11 %),17,18 one was a non-randomized controlled trial (5 %),19 and seven were case series studies (37 %).20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 For conditions investigated, one RCT focused on the elderly,11 one RCT on Parkinson's disease,2 one RCT on surgery,15 one RCT on pain,16 one RCT on Autism spectrum disorder,3 two case series studies on neurophysiology,20,22 three studies (one RCT and two case series studies) on cancer.14,21,26 Three studies including one randomized crossover studies, one non-RCT, one case series study focused on physiological and psychological changes.18,19,23 Moreover, six studies explored singing bowl therapy for mental health, three of six (one randomized crossover study, one non-RCT, one case series study) for sleep disorder,4,13,17 one RCT for anxiety,12 one case series study for depression24 and one case series study for mood.25 Although focusing on different populations with specific characteristics, fourteen studies (74 %) analysed outcomes about mental health, such as depression (n = 9), anxiety (n = 8), heart rate variability (n = 7), quality of sleep (n = 4), and quality of life (n = 4). Regarding the delivery of the intervention, singing bowls were used in the majority of studies (10 studies) as the only intervention. In remaining studies, it was utilized in combination with varies interventions, including usual care (n = 3), meditation (n = 3), yoga (n = 1), relaxation (n = 1), and psychotherapy (n = 1). Among these 19 studies, six utilized both music sound and vibrations from singing bowl as the intervention components, whereas only the musical sound of singing bowl was used in the remainder studies. The characteristics of the included 9 RCTs and 2 randomized crossover studies are presented in Table 1. The characteristics of one non-RCT and 7 case series studies are presented in Supplement 3.

Table 1.

The characteristics of randomized trials.

| First author (year) [ref] | Country/Language | Participants (Sample size) | Interventions (Sample size) | Comparisons (Sample size) | Outcomes | Results MD [95%CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials | ||||||

| Zhang (2024)11 | China/Chinese | 60 hospitalized elderly | (A) Singing bowl (sound + vibration, n=30) + (B) | (B) Usual care (n=30) | 1) Depression (SDS) 2) Anxiety (SAS) |

-7.30 [-8.68, -5.92] -6.00 [-8.04, -3.96] |

| Cristobal (2023)12 | Chile/English | 50 nonclinical anxious adults | (A) Singing bowl (sound, 50 min, 1 session, n=16) | (B) Waiting list control (n = 15); (C) Jacobson’s Progressive Muscle Relaxation (50min, 1 session, n=19) |

1) Anxiety (SAI) 2) Heart rate variability |

(A) vs (B): -9.43 [-11.04, -7.82] (A) vs (C): -4.63 [-6.25, -3.01] (A) vs (B): 0.62 [ 0.12, 1.12] vs (C): 0.43 [-0.09, 0.95] |

| Ren (2023)13 | China/Chinese | 30 college students with sleep disorder preparing for exams | (A) Singing bowl (sound, 30 min/ session, 1 session/day, 7 days, n=15) | (B) No treatment (7 days, n=15) | Quality of sleep (SII) | -1.29 [-4.25, 1.67] |

| Zhang (2023)4 | China/Chinese | 104 adults with inflammatory bowel disease and insomnia | (A) Singing bowl (sound) with yin yoga (60 min/ session, 7 sessions/week, 12 weeks, n=52 ) + (B) | (B) Usual treatment (12 weeks, n=52) | 1) Depression (PHQ-9) 2) Quality of sleep (PSQI) 3) Sleeping time 4) Sleeping latency 5) Wake time 6) Sleep efficiency |

-3.64 [-3.75, -3.55] -3.99 [-4.58, -3.40] 58.87 [44.00, 73.74] -19.71 [-23.90, -15.52] -36.04 [-40.49, -31.59] 13.21 [9.74, 16.68] |

| Li (2023)2 | China/Chinese | 70 patients with Parkinson’s disease | (A) Singing bowl (sound, 60 min/ session, 5 sessions/week, 4 weeks, n=35) + (B) | (B) Usual care (4 weeks, n=35) | 1) Depression (HAMD), 2) Anxiety (HAMA) 3) Cognitive disorder (MoCA) |

-3.87 [-6.69, -1.05] -4.38 [-6.97, -1.79] 2.26 [0.59, 3.93] |

| Li (2021)3 | China/Chinese | 60 children with autism spectrum disorder | (A) Singing bowl (sound + vibration, 30 min/ session, 3 sessions/week, 24 weeks, n=30) + (B) | (B) Usual treatment (60 sessions, n=30) | 1) Autistic behavior (ABC) 2) Autism treatment assessment (ATEC) |

-11.27 [-15.32, -7.22] -6.10 [-10.04, -2.16] |

| Milbury (2013)14 | America/English | 47 women with stages I–III breast cancer | (A) Singing bowl + meditation+usual care (60 min/ session, 2 sessions/week, 6 weeks, n=18) | (B) Waiting list control (6 weeks, n=24) | 1) Cognitive dysfunction (FACT-Cog) 2) Depression (CES-D) 3) Fatigue (BFI) 4) Quality of sleep (PSQI) 5) Mental health (SF-36) 6) Physical health (SF-36) 7) Spiritual well-being (SF-36) |

4.80 [0.27, 9.33] -4.40 [-9.01, 0.21] -0.40 [-1.73, 0.93] 0.40 [-1.54, 2.34] 5.80 [0.12, 11.48] -2.20 [-9.78, 5.38] 5.50 [0.79, 10.21] |

| Antonella (2018)15 | Italy/English | 60 patients undergoing elective major urologic surgery | (A) Singing bowl (sound, 30 min, n=30) | (B) No treatment (n=30) | 1) Trait anxiety (STAI) 2) #Heart rate variability |

-9.80 [-13.34, -6.26] |

| Florian (2008)16 | Austria/German | 54 patients with chronic unspecific spinal pain | (A) Singing bowl (sound + vibration, 30 min/ session, 3 sessions/week, 1 weeks) | (B) Placebo (sound, 30 min/ session, 3 sessions/week, 1 week) (C) No treatment (1 week) |

1) #Pain intensity (VAS, NR) 2) #Pain disability (RMDQ, NR) 3) #Quality of life (SF-36, NR) 4) #Mood state (MDBF, NR) 5) #Heart rate variability (NR) |

|

| Randomized crossover studies | ||||||

| Melanie (2020)17 | Austria/English | 48 healthy individuals | (A) Singing bowl (sound, 20 min, n=48) | (B) Placebo (silent singing bowl, 20 min, n=48) | 1) Pupil-lographic sleepiness (PST) 2) #Situational sleepiness (KSS) |

0.03 [-0.10, 0.15] |

| Jayan (2014)18 | America/English | NR (n=51) | (A) 12 min Singing bowl (sound) + 20 min directed relaxation (n=51) | (B) 12 min Singing bowl (silent) + 20 min directed relaxation (n=51) | 1) Systolic blood pressure 2) Diastolic blood pressure 3) Heart rate variability 4) Positive affect 5) Negative affect |

-4.60 [-11.39, 2.19] -4.00 [-8.17, 0.17] -0.80 [-4.35, 2.75] -0.70 [-4.40, 3.00] 0.40 [-0.19, 0.99] |

Abbreviations: ABC, Autism Behavior Checklist; ATEC, Autism Treatment Assessment Scale; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; CI, confidence interval; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; FACT-Cog, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; KSS, Karolinska sleepiness scale; MD, Mean difference; MDBF, Multidimensional Mood State Questionnaire; MoCA, Montreal cognitive assessment; NR, Not Reported; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; PST, Pupillographic sleepiness test; RMDQ, Rowland-Morris Disability questionnaire; SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; SAS, Self Rating Anxiety Scale; SII, Sleep Impairment Index; SAI, Spielberg's State Anxiety Inventory; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory Questionnaire; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

The statistical analyses could not be performed because of the unreported sample size or data.

3.3. Risk of bias in RCTs

The overall risk of bias of all the 7 RCTs2, 3, 4,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 was “high” (Fig. 2), that was mainly due to all the RCTs had a high risk of bias in measurement of the outcome. Blinding is difficult in a trial, because it is hard to provide a placebo which is exactly the same as singing bowl therapy. Therefore, all the participants filled in several scales of outcomes knew what they received. All the RCTs were “some concerns” in randomization process and selection of the reported results, because the related information was not reported. In terms of deviations from intended intervention, approximately 90% of trials raised “some concerns”, only one trial13 reported dropouts exceeding 5 % without an appropriate analysis, marked as “high” risk of bias. Regarding missing outcome data, the majority of trials were marked as “low” risk of bias, only one trial13 had dropouts over 5 % without any analysis, marked as “high” risk of bias.

Fig. 2.

Summary of risk of bias.

3.4. Evidence from randomized trials

3.4.1. Depression

A total of 4 RCTs reported outcomes of depression using different scales, and we tried to conduct meta-analysis for three of them using scales with the similar scoring principle.2,4,11 However, we found it inappropriate to proceed with meta-analysis due to considerable heterogeneity (I2= 99 %) and obvious clinical diversity among the studies, even though the result obtained was indicative of an significant reduction in depression with singing bowl therapy (SMD = −5.38, 95 % CI [−9.65, −1.10], P = 0.01). Therefore, we performed secondary statistics on these results reported in individual trials using Stata.16 software, and showed that compared with usual care, singing bowl therapy plus usual care demonstrated a significant reduction on depression in hospitalized elderly (MD = −7.30, 95 % CI [−8.68, −5.92], P < 0.05, Table 1),11 and patients with Parkinson's disease (MD = −3.87, 95 % CI [−6.69, −1.05], P = 0.009, Table 1).2 When compared with usual care, singing bowl therapy combining yoga and usual care could significantly reduce depression in adults with inflammatory bowel disease and insomnia (MD = −3.64, 95 % CI [−3.75, −3.55], P < 0.001, Table 1).4 However, singing bowl therapy failed to change depression in women with stages I–III breast cancer comparing with usual care (MD = −4.40, 95 % CI [−9.01, 0.21], P = 0.05, Table 1).14

3.4.2. Anxiety

Similar to the depression, it inappropriate to conduct meta-analysis for 4 RCTs because of the considerable heterogeneity (I2=86 %) and obvious clinical diversity, though the result was indicative of an significant reduction in anxiety with singing bowl therapy (SMD = −1.73, 95 % CI [−2.59, −0.86], P < 0.001). According to results of secondary analysis based on single trial (Table 1), singing bowl therapy plus usual care showed a significant reduction on anxiety in hospitalized elderly (MD = −6.00, 95 % CI [−8.04, −3.96], P < 0.05)11 and patients with Parkinson's disease (MD = −4.38, 95 % CI [−6.97, −1.79], P = 0.002)2 compared with usual care. Tibetan singing bowl therapy had a significant effect on anxiety when compared with a control waiting list (MD = −9.43, 95 % CI [−11.04, −7.82], P = 0.001) and muscle relaxation (MD = −4.63, 95 % CI [−6.25, −3.01], P < 0.00001) in patients with nonclinical anxiety.12 Compared with no treatment, singing bowl therapy had a significant benefit in reducing trait anxiety (MD = −9.8, 95 % CI [−13.34, −6.26], P < 0.01) in patients undergoing elective major urologic surgery.15 However, this RCT also reported there was no significant impact from singing bowl for Amsterdam preoperative anxiety score (without secondary analysis due to insufficient data, P > 0.05).15

3.4.3. Fatigue

The secondary analysis for one RCT14 of women with stages I–III breast cancer revealed, compared with usual care, singing bowl therapy failed to change fatigue (MD = −0.40, 95 % CI [−1.73, 0.93], P > 0.05, Table 1).

3.4.4. Quality of sleep

Similar to the depression and anxiety, conducting a meta-analysis for 3 RCTs reporting quality of sleep is deemed inapposite because of the considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 90 %), and the result indicated no difference between the groups (MD = −1.75, 95 % CI [−4.92, 1.43], P = 0.28). The secondary analysis of single RCT found there was no significant benefit due to singing bowl therapy in quality of sleep in college students with sleep disorder (MD = −1.29, 95 % CI [−4.25, 1.67], P > 0.05)13 and women with stages I–III breast cancer (MD = 0.40, 95 % CI [−1.54, 2.34], P > 0.05)14 when compared with no treatment (Table 1). Furthermore, the statistical analysis of another RCT4 included adults with inflammatory bowel disease and insomnia showed singing bowl therapy combining yoga and usual care could significantly improve quality of sleep (MD = −3.99, 95 % CI [−4.58, −3.40], P < 0.001), sleeping time (MD = 58.87, 95 % CI [44.00, 73.74], P < 0.001) and sleep efficiency (MD =13.21, 95 % CI [9.74, 16.68], P < 0.001), reduce sleeping latency (MD = −19.71, 95 % CI [−23.90, −15.52], P < 0.001) and wake time (MD = −36.04, 95 % CI [−40.49, −31.59], P < 0.001) comparing with usual care (Table 1). The results of one trial17 included healthy participants reported, situational sleepiness could be significantly reduced due to singing bowl therapy, when compared with placebo (without secondary analysis due to insufficient data, P = 0.04). Whereas, the pupil-lographic sleepiness was not affected by singing bowl (MD = 0.03, 95 % CI [−0.10, 0.15], P = 0.46, Table 1). The placebo applied singing bowl without sound, which was the difference with singing bowl therapy. However, though the music intervention was not used in placebo, the vibration used may still produce the intervention.

3.4.5. Cognitive function

A total of 2 RCTs reported outcomes of cognitive function, however, the meta-analysis was not considered due to obvious clinical heterogeneity. The secondary analysis based on an RCT2 indicated singing bowl therapy plus usual care had a significant effect on cognitive disorder in patients with Parkinson's disease comparing with usual care (MD = 2.26, 95 % CI [0.59, 3.93], P = 0.01, Table 1). The statistical analysis of another RCT14 of women with stages I–III breast cancer revealed singing bowl therapy could significantly improve perceived cognitive abilities (MD = 4.80, 95 % CI [0.27, 9.33], P < 0.05, Table 1) compared with usual care.

3.4.6. Outcomes investigated autism spectrum disorder

From the results of secondary analysis in single RCT3 included children with autism spectrum disorder, singing bowl therapy plus usual care could effectively change autistic behavior (MD = −11.27, 95 % CI [−15.32, −7.22], P < 0.05, Table 1) and autism treatment assessment (MD = −6.1, 95 % CI [−10.04, −2.16], P < 0.05, Table 1).

3.4.7. Quality of life and other outcomes investigated mentle health

According to the results of secondary analysis based on a single RCT14 investigated quality of life in women with stages I–III breast cancer by Short Form 36 Health Survey, compared with usual care, singing bowl therapy could significantly improve mental health (MD = 5.80, 95 % CI [0.12, 11.48], P < 0.04, Table 1), spiritual well-being (MD = 5.50, 95 % CI [0.79, 10.21], P < 0.05, Table 1), but failed to improve physical health (MD = −2.20, 95 % CI [−9.78, 5.38], P > 0.05, Table 1). Without secondary analysis due to insufficient data, an RCT reported singing bowl therapy could also improve quality of life in patients with chronic unspecific spinal pain when compared with no treatment.16 Moreover, from the results of secondary analysis based on one trial18 of 51 participants, there was no significant benefit of singing bowl plus directed relaxation on positive (MD = −0.70, 95 % CI [−4.40, 3.00], P > 0.05, Table 1) and negative affect (MD = 0.40, 95 % CI [−0.19, 0.99], P > 0.05, Table 1) when compared with placebo, which applied singing bowl without sound plus directed relaxation.

3.4.8. Heart rate variability

A total of 4 RCTs reported heart rate variability, however, the meta-analysis was not considered due to obvious clinical heterogeneity or insufficient data. The secondary analysis of one RCT12 with adult patients with nonclinical anxiety demonstrated that Tibetan singing bowl had a significant effect on heart rate variability when compared with waiting list (MD = 0.62, 95 % CI [0.12, 1.12], P = 0.001, Table 1). However, there were no differences between Tibetan singing bowl and muscle relaxation (MD = 0.43, 95 % CI [−0.09, 0.95], P = 0.11, Table 1). In addition, another two RCTs with insufficient data also reported singing bowl had an obvious benefit in heart rate variability in patients undergoing elective major urologic surgery15 and patients with chronic unspecific spinal pain.16 According to results of statistical analysis based on one trial18 of 51 participants, there was no significant benefit of singing bowl plus directed relaxation on heart rate variability (MD = −0.80, 95 % CI [−4.35, 2.75], P > 0.05, Table 1) when compared with placebo applying singing bowl without sound plus directed relaxation.

3.4.9. Blood pressure

The results of secondary analysis based on one trial18 of 51 participants found, singing bowl plus directed relaxation failed to significantly decrease systolic blood pressure (MD = −4.60, 95 % CI [−11.39, 2.19], P > 0.05, Table 1) and diastolic blood pressure (MD = −4.00, 95 % CI [−8.17, 0.17], P > 0.05, Table 1) comparing with placebo applying singing bowl without sound plus directed relaxation.

3.4.10. Pain

Without meta-analysis due to insufficient data, an RCT16 included 54 patients with chronic unspecific spinal pain showed, compared with no treatment, singing bowl therapy could significantly reduce pain intensity (P < 0.05), but failed to demonstrate any benefit for disability related to pain (P > 0.05).

3.5. Evidence from non-RCT and case series studies

The results of one non-RCT and 7 case series studies demonstrated that singing bowl therapy had a potential effect on psychological function including depression, anxiety, stress, tension, anger, fatigue, confusion, vigor, spiritual well-being, positive and negative affect, as well as physiological function including heart rate variability, respiration rate and electroencephalograph. However, it is hard for singing bowl to influence depression, anxiety, distress, fatigue, quality of life, heart rate variability, respiration rate and electroencephalograph of cancer patients. Supplement 3 showed the result reported by these non-RCT and case series studies.

4. Discussion

Over the past few years, music-based interventions have gradually been implemented in Western healthcare.27 This non-pharmaceutical therapy has been shown to relieve various symptoms, including pain, anxiety, and stress,28 which also be considered as one of the most widely used approach to treat the psychosocial related symptoms of cancer.29 As a music therapy, singing bowl therapy has a long history and has cultural connotations. The application of the singing bowl has been gradually implemented in the medical field. This systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of singing bowl therapy's application in clinical settings and the characteristics of related research. This review summarizes and reports the current evidence on singing bowl therapy. Data from the included 19 trials found that singing bowl therapy has been used to intervene the elderly, patients undergo surgery, Parkinson's disease, pain, cancer, neurological function, sleep disorder, depression, anxiety, children with autism spectrum disorder, as well as physiological and psychological function. Although singing bowl therapy is used for many of these conditions, it has mainly focused on outcomes related to mental health.

From the evidence summarized, we found singing bowl therapy has a potentially significant effect on anxiety and depression in the elderly11 and patients with anxiety,12 depression,24 sleep disorder,4 Parkinson's disease,2 and patients undergo surgery.15 Singing bowl therapy can also potentially relieve negative mood, including tension, anger, stress and fatigue.19,23, 24, 25 Furthermore, singing bowl therapy can improve quality of sleep, reduce drowsiness of patients with sleep disorder.4 For Parkinson's disease, using singing bowl therapy can help to improve cognitive function.2 For cancer, singing bowl therapy can also potentially improve cognitive function and wellbeing, but failed to relieve anxiety, depression, stress, fatigue and quality of sleep.14,21,26 For chronic unspecific spinal pain, though singing bowl therapy can help to relieve pain, it is hard for singing bowl therapy to improve quality of life and heart rate variability.16 Similarly, there was no evidence to suggest that singing bowl therapy to decrease heart rate variability in patients undergoing surgery.15 For autism spectrum disorder, singing bowl therapy can improve autistic behavior, and clinical manifestation.3 Furthermore, in terms of physiological function, in addition to lowering heart rate and breathing, singing bowl therapy can also improve electroencephalography.19,20,22,23 No adverse events related to singing bowl therapy were reported. These evidence summarized indicate as a safe intervention, singing bowl therapy may help the body relax and stimulate brain waves. The results of the included trials were heterogeneous, with some studies showing significant benefits of singing bowl therapy, while others did not. These discrepancies may be attributed to differences in study design, sample sizes, and interventions. Studies with larger sample sizes and more rigorous methodologies generally reported more reliable results. Additionally, variations in the duration and frequency of singing bowl therapy sessions, as well as differences in the control interventions, may have contributed to the inconsistent findings.

According to this systematic review, the current clinical trials on singing bowl therapy mainly focused on the psychological outcomes, which is related to the characteristics of singing bowl therapy. However, the specific mechanisms operating in singing therapy has been rarely investigated. As a kind of music therapy, singing bowl therapy is similar with the clinical application of other music therapies, and their underlying mechanism are likely to be highly similar. It has been reported that patients with traumatic encephalopathy have increased gray matter volume in multiple subregions of the cerebral cortex after receiving music therapy, which is thought to be one of the reasons for the significant improvement in executive function, attention, and cognitive imagination.30 A clinical study by Koelsch. et al. found, cortisol levels are reduced when participants received music therapy, causing stress release.31 Several studies have shown that music therapy reduces the activity of brain structures that affect mental processes, including anxiety and emotional distress.32,33

This systematic review has some strengths. Firstly, all types of clinical study designs were eligible for inclusion in this review, which ensured a comprehensive evaluation of the available evidence on the effects of singing bowl therapy across diverse populations and research methodologies, providing a extensive overview of the current state of research on singing bowl therapy. Furthermore, adhering to the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions8 and the PRISMA statement,9 we recognized the importance of results from individual trial in the overall summary, even when meta-analysis was not feasible due to insufficient data or heterogeneity. To enhance the precision of these results, we conducted secondary statistical analyses on individual trials.

However, there are also some limitations of this systematic review. Firstly, one notable limitation of this review is the unavailable meta-analysis. Many outcomes were only reported by a single trial, precluding the possibility of conducting meta-analyses, which limits the ability to synthesize and generalize findings across multiple studies. Additionally, for those outcomes reported by multiple trials, significant statistical heterogeneity and clinical diversity were observed. This heterogeneity, stemming from differences in study populations and interventions, may bias the results of meta-analyses. All the RCTs included in this review were found to have a high risk of bias, particularly in outcome measurement and randomization, which may affect the reliability of findings. The lack of blinding in many trials may potentially introduce performance bias and detection bias. And the randomization process was often poorly described, raising concerns about the allocation concealment and sequence generation, may have inflated the observed effects, leading to overestimation of the true therapeutic benefits of singing bowl therapy. In addition, half of the evidence came from RCTs and the other half from other types of studies, therefore, the variability in methodological quality and risk of bias across studies also affects the certainty of the conclusions drawn. Moreover, the limited research exploring the underlying mechanisms of singing bowl therapy constrains our understanding of its therapeutic effects. While this review provides evidence on the potential benefits of singing bowl therapy across various conditions, the absence of mechanistic studies leaves a gap in our knowledge regarding how this intervention exerts its effects.

Given the preliminary results, future studies should consider employing a wider range of search terms, such as “sound healing” and “vibrational therapy”, to broaden the scope of literature searches. These terms may uncover additional relevant studies that were not identified in the current review, thereby enriching the evidence base for singing bowl therapy. Future research should focus on rigorously designed randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods. There is a need for standardization of singing bowl therapy interventions to ensure consistency across studies. Additionally, research should delve into the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the therapy's effects, potentially through neuroimaging or biomarker studies. The potential of singing bowl therapy as a complementary treatment modality warrants exploration, with future studies addressing the current gaps in knowledge and methodology.

In conclusion, singing bowl therapy appears to be a safe and potentially beneficial intervention for a variety of conditions. It may help to alleviate anxiety, depression, improve quality of sleep and cognitive function in various patient groups, and change autistic behavior. It also shows potential in physiological improvements like electroencephalography. While singing bowl therapy appears to offer benefits for mental health and physiological well-being, the evidence base requires further strengthening through higher quality research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yiqing Cai: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Guoyan Yang: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Yibo Liu: Software, Visualization. Xiangyun Zou: Software. Heng Yin: Investigation. Xinyan Jin: Validation. Xuehan Liu: Formal analysis. Chenlu Wang: Visualization. Nicola Robinson: Writing – review & editing. Jianping Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by High-level traditional Chinese medicine key subjects construction project of National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine——Evidence-based Traditional Chinese Medicine (zyyzdxk-2023249); Evidence-based Chinese medicine discipline innovation and intelligence base (B23041).

Ethical statement

No ethical approval was required as this study did not involve human participants or laboratory animals.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.imr.2025.101144.

Supplement 1. PRISMA checklist.

Supplement 2. Database retrieval strategies.

Supplement 3. The characteristics of other types of trials.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Yong Z., Jin Y. Review of traditional Chinese medicine value-oriented music therapy research. J Guangzhou Univ Traditi Chinese Med. 2018;35(06):1139–1142. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jianping L., Yan L., Rong J. Effects of singing bowl therapy in the rehabilitation of Parkinson’s disease. Practical J Clin Med. 2023;20(03):149–152. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuo L., Zhilin L., Yong Z. Effects of singing bowl therapy on Autism spectrum disorder in children. Massage Rehabil Med. 2021;12(21):34–37. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ping Z., Ting T., Yu Z. Effect of singing bowl therapy combined with Yin yoga on sleep disorders in adults with emerging inflammatory bowel disease. Modern J Integr Tradit Chinese Western Medic. 2023;32(19):2756–2759. +2763. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zichao X., Fengying L., Yuanyuan C. Theoretical basis and research progress of sing bowl in music therapy. Asia-Pacific Trad Med. 2020;16(08):173–175. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Y. Analysis of acoustic principle of sing bowl and therapeutic effect of music. Musical Instrum Magazine. 2022;(07):19–21. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leping X., Jin Y., Li L. Exploring low dissipation optimization mechanism of customized state music to intervene prefrontal cortex function by fNIRS. Chinese J Med Phys. 2022;39(10):1303–1309. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins J.P.T., Thomas J., Chandler J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 (updated August 2024) Cochrane; 2024. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidiset J.P.A., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterne J.A.C., Savović J., Page M.J., Elbers R.G., Blencowe N.S., Boutron I., et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diwei Z. The effect of introducing singing bowl music therapy in elderly patients during hospitalization. China Sci Technol J Database Med. 2024;(1):0118–0121. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotoia A., Dibello F., Moscatelli F., Sciusco A., Polito P., Modolo A., et al. Effects of tibetan music on neuroendocrine and autonomic functions in patients waiting for surgery: a randomized, controlled study. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/9683780. Mar 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ming R., Tingting W., Shijing W. The characteristics of meridian collaterals and the effect mechanism of singing bowl as sleep aid for college students with abnormal sleep based on the bioelectrical signals of meridian points. Modern J Integrat Trad Chinese Western Med. 2023;32(13):1828–1834. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milbury K., Chaoul A., Biegler K., Wangyal T., Spelman A., Meyers C.A., et al. Tibetan sound meditation for cognitive dysfunction: results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22(10):2354–2363. doi: 10.1002/pon.3296. Oct. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotoia A., Dibello F., Moscatelli F., Sciusco A., Polito P., Modolo A., et al. Effects of tibetan music on neuroendocrine and autonomic functions in patients waiting for surgery: a randomized, controlled study. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/9683780. Mar 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wepner F., Hahne J., Teichmann A., Berka-Schmid G., Hördinger A., Friedrich M. Treatment with crystal singing bowls for chronic spinal pain and chronobiologic activities - a randomized controlled trial. Forsch Komplementmed. 2008 Jun;15(3):130–137. doi: 10.1159/000136571. (in German) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergmann M., Riedinger S., Stefani A., Mitterling T., Holzknecht E., Grassmayr P., et al. Effects of singing bowl exposure on Karolinska sleepiness scale and pupillographic sleepiness test: a randomized crossover study. PLoS One. 2020;15(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233982. Jun 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landry J.M. Physiological and psychological effects of a Himalayan singing bowl in meditation practice: a quantitative analysis. Am J Health Promot. 2014;28(5):306–309. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.121031-ARB-528. May-Jun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trivedi G., Saboo B. A comparative study of the impact of himalayan singing bowls and supine silence on stress index and heart rate variability. J Behav Therapy Mental Health. 2019;2:40–50. doi: 10.14302/issn.2474-9273.jbtm-19-3027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S.C., Choi M.J. Does the sound of a singing bowl synchronize meditational brainwaves in the listeners? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(12):6180. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20126180. Jun 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elizabeth K., Wheeler M.A. Alliant International University; 2023. The Effect of Sound Meditation On Quality of Life Among Patients With Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walter N., Hinterberger T. Neurophysiological effects of a singing bowl massage. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58(5):594. doi: 10.3390/medicina58050594. Apr 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panchal S., Irani F., Trivedi G.Y. Impact of himalayan singing bowls meditation session on mood and heart rate variability. Int J Psychotherapy Practice Res. 2020 doi: 10.14302/issn.2574-612X.ijpr-20-3213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rebecca M., Luna M.A. Alliant International University; 2018. An Examination of a Sound Healing Intervention As an Adjunct to Psychotherapy For Depression. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldsby T.L., Goldsby M.E., McWalters M., Mills P.J. Effects of singing bowl sound meditation on mood, tension, and well-being: an observational study. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22(3):401–406. doi: 10.1177/2156587216668109. Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bidin L., Pigaiani L., Casini M., Seghini P., Cavanna L. Feasibility of a trial with tibetan singing bowls, and suggested benefits in metastatic cancer patients. A pilot study in an Italian Oncology Unit. Eur J Integr Med. 2016;8(5):747–755. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldsby T.L., Goldsby M.E. Eastern integrative medicine and ancient sound healing treatments for stress: recent research advances. Integr. Med. 2020;19:24–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stegemann T., Geretsegger M., Phan Q.E., Riedl H., Smetana M. Music therapy and other music-based interventions in pediatric health care: an overview. Medicines. 2019;6:25. doi: 10.3390/medicines6010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bro M.L., Jespersen K.V., Hansen J.B., Vuust P., Abildgaard N., Gram J., et al. Kind of blue: a systematic review and meta-analysis of music interventions in cancer treatment. Psychooncology. 2018;27:386–400. doi: 10.1002/pon.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siponkoski S.T., Martínez-Molina N., Kuusela L., Laitinen S., Holma M., Ahlfors M., et al. Music therapy enhances executive functions and prefrontal structural neuroplasticity after traumatic brain injury: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(4):618–634. doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6413. Feb 15Epub 2019 Dec 5. PMID: 31642408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koelsch S., Fuermetz J., Sack U., Bauer K., Hohenadel M., Wiegel M., et al. Effects of music listening on cortisol levels and propofol consumption during spinal anesthesia. Front Psychol. 2011;2:58. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fachner J., Gold C., Erkkilä J. Music therapy modulates fronto-temporal activity in rest-EEG in depressed clients. Brain Topogr. 2013;26(2):338–354. doi: 10.1007/s10548-012-0254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raglio A., Attardo L., Gontero G., Rollino S., Groppo E., Granieri E. Effects of music and music therapy on mood in neurological patients. World J psychiatry. 2015;5(1):68–78. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.