Abstract

Traditional medicine is the primary healthcare source for most people in developing nations, with herbal remedies used for disorders of metabolism. The study assessed how Andrographis paniculata aqueous extract affected male Wistar rats' cardiotoxicity caused by dichlorvos. Three groups consisting of eighteen rats were randomly assigned (n = 6). Group A was not exposed to dichlorvos, as it served as (control). Group B was exposed to dichlorvos (1 ml/day for 1 week) via inhalation. Group C was exposed to dichlorvos (as in B) and treated with Andrographis paniculata aqueous extract (500 mg/kg body weight) orally for 28 days. Exposure to dichlorvos caused alteration in cardiovascular variables and electrocardiac function (blood pressure, heart rate and electrocardiogram), cardiac injury (lactate dehydrogenase and creatine kinase), oxidative stress (malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), reduced glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)), cardiac inflammation (tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and apoptosis (caspase 3). However, treatment with Andrographis paniculata aqueous extract improved the antioxidant defense system, attenuated electrocardiac impairment, and prevented damage to cardiac musculature. Andrographis paniculata aqueous extract exhibited cardioprotective potential.

Keywords: Andrographis paniculata, Cardiotoxicity, Dichlorvos, Cardiac markers, Oxidative stress

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Dichlorvos-induced cardiotoxicity via oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis.

-

•

Aqueous extract of A. paniculata confers cardioprotection against DDVP-induced cardiotoxicity by restoring cardiac hemodynamic and enhancing endogenous antioxidant defense.

-

•

The extract’s anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties reduce tissue injury and inflammation.

-

•

The study also showed that whole herb extract might be used for prophylaxis and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for around 20 percent of all fatalities globally and is a leading cause of sickness and mortality. According to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO), almost 30 million people will die from CVD. Most CVD-related deaths occur in developing countries, predominately among people under the age of 70 [68], [73]. CVD mainly result because vascular dysfunction has the potential to harm organs. The primary factors that cause high blood pressure, thrombosis, and atherosclerosis are examples of vascular dysfunctions. Furthermore, smoking, an unhealthy diet, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, dyslipidemia, physical inactivity, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), and hypertension are major risk factors that significantly contribute to cardiovascular health risks [34], [67]. Apart from the fundamental risk factors, exposure to environmental toxic substances such as pesticides can also contribute to cardiovascular diseases through inflammation and oxidative stress. Consequently, ecological toxicants must be regarded as important CVD risk factors [60].

An international challenge is the use of organophosphates (OPs) in the control of key disease-carrying vectors. OPs have been connected to health risks, human poisoning, and environmental contamination [38]. Toxicity and non-specific multi-organ toxicity have been seen to rise with the release of OPs into the environment through unintentional exposure to them [39]. Dichlorvos (DDVP) is an OP pesticide that is known to have cardiotoxic effects. The production of reactive free radicals, which is probably the cause of DDVP-mediated cell damage, is one of the possible causes of the drug's negative effects [23], or abnormal calcium signaling, which could lead to irregular arrhythmia, chronic heart failure, and electrical conduction in the heart [5]. Research has shown that besides the established primary mechanism of action, acetylcholinesterase inhibition, DDVP induces oxidative stress and reduces antioxidant activities [25], [43], [50], [51].

Often referred to as the King of Bitters, Andrographis paniculata is a herbaceous plant of the Acanthaceae family. For centuries, people have utilized it traditionally to treat a wide range of ailments on the continents of Asia, America, and Africa. These ailments include cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, ulcers, leprosy, bronchitis, skin diseases, flatulence, colic, influenza, dysentery, dyspepsia, and malaria [29]. The plant is also used traditionally for detoxification in China [19], [58]. It has been demonstrated that the plant's extract and pure components have antibacterial properties [1], [72], immunostimulant, immunomodulatory [46], anti-inflammatory and antioxidant [35], [40], [42], [74], anti-diabetic [32], [41], [48], [59], hepato-renal protective [42], [59], modulation of sexual function and sex hormone [40], glucose regulation and insulin sensitivity [52].

There is little information available on DDVP's effects on cardiovascular function after inhalational exposure, which is the most common route of exposure. Additionally, it is unknown how Andrographis paniculata, an antioxidant, may affect DDVP-induced cardiovascular changes. Consequently, it's critical to look at how an aqueous extract of Andrographis paniculata affects the cardiovascular alterations in male Wistar rats given dichlorvos. The purpose of this work is to determine how this extract affects the cardiovascular changes caused by DDVP in adult male Wistar rats.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Eighteen male Wistar rats in total, about 8–10weeks old and with body weights ranging from 200 g to 250 g, used in this investigation were procured and housed at the Department of Physiology's animal house of the Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH), Ogbomoso. The rats were given a regular pellet diet and unlimited access to water in a well-ventilated plastic cage. The rats were acclimated to the laboratory conditions (temperature 25ºC and environment 12 h light-dark cycle) for two weeks. Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences ethics committee of LAUTECH, Ogbomoso gave approval for this study (FBMS/AEC/P/074/22). A conscious effort was made to guarantee that the fewest possible animals were used and that their suffering was kept to a minimum.

2.2. Treatments

The eighteen (18) rats were subjected to a random sampling technique to allocate the rats into three groups. Each group consists of six (6) rats.

-

♦

Group A (control): were given standard rat feed, water, and 1 ml of distilled water daily.

-

♦

Group B (DDVP): The rats were given standard rat feed and water and exposed to 98.4 g/m3 DDVP via inhalation for 15 min daily [49], [51] and 1 ml of distilled water daily through the oropharyngeal cannula. 1 ml) of DDVP was dropped on a cotton wool which was placed in a compartment of the desiccator while the rat was placed in another compartment for 15 min. There was easy diffusion of the DDVP across the desiccator, but the rat had no physical contact with the cotton wool.

-

♦

Group C (DDVP + A. paniculata): The rats were given standard rat feed and water and exposed to DDVP as described above for group B and 500 mg/kg of aqueous extract of A. paniculate [53] once per day through the oropharyngeal cannula for 28 days.

DDVP was administered at a dosage of 98.54 g/m3 – similar to previous studies [49], [50]. The route of administration was inhalation, as described by Saka and colleagues [49]. The dose of A. paniculata used is as reported in a previous study [53]. Rats were treated in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory animals, and the study received approval from the ethical committee of the Faculty of Basic Medical Science at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH), Ogbomoso.

2.3. Chemicals

The DDVP containing 1000 g of DDVP/Litre) used for the study was manufactured by Forward (Beinaj) Hepu Pesticide Co. Limited, China, and procured from Saro Agrosciences Limited, Oyo State, Nigeria. Standard ELISA kits were utilized for the detection of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatinine kinase (CK), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Agappe Diagnostics, Switzerland).

2.4. Plant collection, extraction, and preparation

Andrographis. paniculata fresh leaves were obtained from herbarium of the Department of Pure and Applied Biology, LAUTECH, Ogbomoso with voucher number LHO 715. After air drying, the leaves were pulverized in an electric blender. In a conical flask, 300 g of A. paniculata powder and 3 L of distilled water were combined. The mixture was stirred multiple times, covered, and left at room temperature overnight. The next day, Whatman filter paper (15 cm) was utilized to filter the mixture, and the filtrate was evaporated at 40°C until completely dry. This resulted in a fine, dark-colored solid residue, which was scraped, weighed, and stored in a capped bottle. A fresh solution was made from the dried residue daily [37].

2.5. Sample collection and preparation

The animals were weighed at the start of the trial, weekly and at the end of the experiment. The difference between the weight at the start and finish of the experiment was used to calculate body weight growth. After all administration is complete (end of experimental period), the rats were anesthetized with 1 % chloralose and 25 % urethane given intraperitoneally. Blood pressure measurement and electrocardiography were carried out. After a heart puncture, blood was collected and centrifuged for five minutes at 3000 r.p.m, after which serum was collected for biochemical analysis. The hearts were excised, divided, fixed in buffered formalin, and processed for immunohistochemical staining.

2.6. Biochemical assays

ELISA kits were utilized to measure the serum levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Agappe Diagnostics, Switzerland) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Colorimetric techniques were used to measure the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), reduced glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), malondialdehyde (MDA), and myeloperoxidase (MPO) [6], [7], [8].

ELISA kits were used to measure the levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatinine kinase (CK) in serum (Agappe Diagnostics, Switzerland) following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Cardiovascular parameters (Blood pressure, heart rate, and electrocardiography)

After the period of the administration, rats were given anesthesia. with 1 % chloralose and 25 % urethane given intraperitoneally. Anesthesia was confirmed by checking for a lack of pedal reflex. The rats were then placed on a board, and conductive gel was applied to the chest, left arm, left leg, right arm, and right leg, followed by the attachment of EDAN electrodes. The electrodes were then connected to the laptop, and information about the rats was stored there. An electrocardiogram was recorded for each rat for one minute, following a procedure described in previous studies [12]. Following the anesthesia, the rats' femoral artery was cannulated, and a pressure transducer (P23LD Statham Hato Rey, Inc.) of the Grass 7D polygraph (Grass Instrument Ltd, Quincy, Massachusetts, USA) was used to measure their blood pressure. Alongside blood pressure, heart rate was also recorded. This procedure was carried out following previously reported studies [13]. Calculating the mean arterial blood pressure was done as:

MAP = DBP + 1/3 (SBP – DBP)

MAP – Mean arterial blood pressure

SBP – Systolic blood pressure

DBP – Diastolic blood pressure.

2.8. Caspase-3 immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was carried out as described in previous studies [21]. Before being deparaffinized and having the antigen extracted, paraffin slices (5 μm) were dried for an hour at 37°C. The endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by incubating the sections for 10–15 minutes. The slides were subjected to a one-hour incubation process with the polyclonal antibody at 37°C, followed by washing and incubation with prediluted biotinylated goat antirabbit IgGs for half an hour and streptavidin horseradish-peroxidase.

The caspase-3 labeling index was calculated as the percentage of apoptotic cells per total number of cells:

2.9. Phytochemical analysis

Qualitative phytochemical screening of A. paniculata aqueous extract was done and reported as previously documented by [36].

2.10. Test for alkaloids

One milliliter (1 ml) of diluted hydrochloric acid (HCl) was mixed with a little amount of the extract before it was filtered. The reagent Dragandroff's was applied to the filtrate. The presence of alkaloids is indicated by the formation of organic precipitate.

2.11. Test for tannins

In a test tube, a little amount of the dried powder of Andrographis paniculata was boiled in 20 milliliters of water and then filtered. After adding a few drops of 0.1 percent ferric chloride, the presence of tannins was indicated by a blackish-blue or brownish-green tint.

2.12. Test for saponins

In a water bath, two (2) g of powdered Andrographis paniculata was boiled in 20 ml of water and then filtered. To verify if saponins are present, combine 10 milliliters of the filtrate with 5 milliliters of water in a test tube, shake well, and watch for the development of a stable foam.

2.13. Test for flavonoids

The extracts turned yellow when strong sulfuric acid was added, signifying the presence of flavonoids.

2.14. Test for terpenoids (Salkowski test)

5 g of extract were mixed with 2 milliliters of chloroform. After that, 3 ml of concentrated H2SO4 was added to create a layer. A thin interface developed a reddish-brown coloring, signifying a positive terpenoids test.

2.15. Test for protein

To perform Xanthoprotein tests, a small amount of extract was dissolved in 5 ml of water followed by addition of 1 ml concentrated nitric acid and stirred. As a result, a white precipitate was formed. The solution was heated for 1 minute and then allowed to cool under running water. It was made alkaline by an excess of NaOH. The appearance of an orange precipitate indicates the presence of protein.

2.16. Test for phytosterol

The Salkowski test was used to determine if phytosterol was present. After adding 1 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid to 1 g of plant extract, the mixture was let to stand for 5 minutes. Following shaking, the lower layer had a golden-yellow hue, which suggested the presence of phytosterol.

2.17. Test for glycosides

Fehling's test was performed on a little amount of the extract after it had been hydrolyzed for a few hours in a water bath with 5 ml HCL. Reducing sugars were present when a yellow or red-colored precipitate appeared.

2.18. Statistical analysis

In order to compare the mean values of the variables between the groups, the data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism for Windows' one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's posthoc test for multiple comparisons to determine the significance of individual variation between two groups (Versions 5, GraphPad Software, Inc.). P values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. The data are shown as mean ± SEM.

3. Results

3.1. Estimation of body weight

After receiving DDVP administration, there was a significant decrease in body weight gain. On the other hand, oral administration of A. paniculata prevented this effect (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Body weight gain in control, DDVP-treated and DDVP + AP rats. The mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M) is shown by each bar. *p < 0.05 in comparison to the control, #p < 0.05 vs DDVP-treated. DDVP: Dichlorvos; AP: Andrographis paniculata. Body weight is expressed in grams. Dosage of DDVP= 98.54 g/m3; Dosage of AP= 500 mg/kg.

3.2. Estimation of cardiovascular variables

3.2.1. Blood pressure (SBP and DBP) and heart rate (HR) of rats

Fig. 2 shows the effect of DDVP inhalation and treatment with A. paniculata on blood pressure parameters. DDVP increased SBP, DBP, and MAP but reduced HR when compared with the control. Treatment with A. paniculata attenuated DDVP-induced alterations.

Fig. 2.

A- Systolic blood pressure; B- Diastolic blood pressure; C- Mean arterial blood pressure; D- Heart rate; and E- Pulse pressure in control, DDVP-treated and DDVP + AP treated rats. Each bar represents mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.M). *p < 0.05 vs control, #p < 0.05 vs DDVP-treated. Dosage of DDVP= 98.54 g/m3; Dosage of AP= 500 mg/kg DDVP: Dichlorvos; AP: Andrographispaniculata. Blood pressures are expressed in mmHg and heart rate is expressed in beats/min.

3.3. Estimation of electro-cardiac function

3.3.1. P-Duration, PR-Intervals, QRS complex, and QT-Intervals of rats

The effects of DDVP and A. paniculata on the electrocardiogram in treated rats are shown in Fig. 3. P-duration had no significant difference. PR-interval, QRS complex, and R amplitude. However, DDVP treatment caused a significant increase in QT-interval while treatment with A. paniculata prevented the prolongation of QT-interval.

Fig. 3.

A- P duration; B- PR interval; C- R amplitude; D- QRS complex; and E- QT interval in control, DDVP-treated and DDVP + AP rats. Each bar represents mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.M). *p < 0.05 vs control, #p < 0.05 vs DDVP-treated. Dosage of DDVP= 98.54 g/m3; Dosage of AP= 500 mg/kg. DDVP= Dichlorvos; AP: Andrographis paniculata. P duration, PR interval, QRS complex and QT interval are expressed in ms. R amplitude is expressed in mV.

3.4. Estimation of cardiac enzymes

3.4.1. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatine kinase enzyme (CK-MB) of rats

The results of DDVP and A. paniculata treatment are illustrated in Fig. 4. DDVP significantly increased the concentration of LDH and CK-MB compared with the control. A. paniculata treatment decreased the concentration of LDH and CK-MB.

Fig. 4.

A- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); B- Creatine kinase (CK-MB)in control, DDVP-treated and DDVP + AP rats. Each bar represents mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.M). *p < 0.05 vs control, #p < 0.05 vs DDVP-treated. Dosage of DDVP= 98.54 g/m3; Dosage of AP= 500 mg/kg. DDVP: Dichlorvos; AP: Andrographis paniculata. LDH and CK-MB are expressed in U/L.

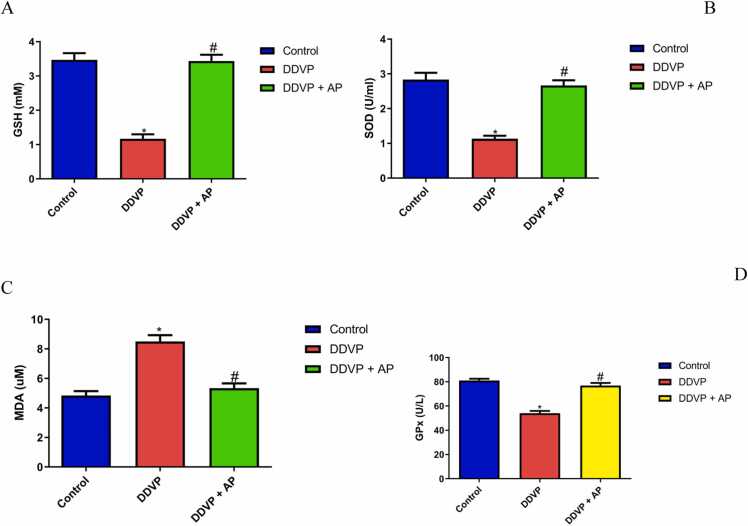

3.4.2. Estimation of cardiac oxidative markers and antioxidant enzymes

Fig. 5 shows the results of exposure to DDVP and A. paniculata on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant activities. Inhalation of DDVP upregulated lipid peroxidation and diminished activities of antioxidants when compared to control rats. Oral administration of A. paniculata prevented lipid peroxidation and enhanced antioxidant activities.

Fig. 5.

A- Reduced glutathione (GSH); B- Superoxide dismutase (SOD); C- Malondialdehyde (MDA); D- Glutathione peroxidase (GPx)in control, DDVP-treated and DDVP + AP rats. Each bar represents mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.M). *p < 0.05 vs control, #p < 0.05 vs DDVP-treated. Dosage of DDVP= 98.54 g/m3; Dosage of AP= 500 mg/kg DDVP: Dichlorvos; AP: Andrographispaniculata.

Estimation of Cardiac inflammatory markers and apoptosis

The effect of exposure to DDVP and treatment with A. paniculataare shown in Fig. 6. DDVP increased the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, MPO, and caspase-3 expression in contrast to rats used as controls. Treatment with A. paniculata at the dose of 500 mg/kg decreased the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, MPO, and caspase-3 expression.

Fig. 6.

A- Myeloperoxidase (MPO); B-, Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α); C- Interleukin-6 (IL-6); D- Caspase 3 in control, DDVP-treated and DDVP + AP rats. Each bar represents mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.M). *p < 0.05 vs control, #p < 0.05 vs DDVP-treated. Dosage of DDVP= 98.54 g/m3; Dosage of AP= 500 mg/kg. DDVP: Dichlorvos; AP: Andrographis paniculata.

3.4.3. Immunohistochemistry

Effects of exposure to DDVP and treatment with A. paniculata on cardiac histo-architecture are shown in Fig. 7. DDVP led to degradation of cardiac histo-architecture and elevated caspase-3 expression in contrast to rats used as controls. Treatment with A. paniculata at the dose of 500 mg/kg preserved the cardiac histo-architecture and decreased caspase-3 expression (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Photomicrograph (magnification x400) of immunohistochemistry assay of a heart tissue in control, DDVP-treated and DDVP+AP-treated rats. A- control showing no expression of Caspase 3in the cytoplasm of cardiac muscle; B- DDVP-treated showing moderate expression of Caspase 3in the cytoplasm of cardiac muscle; C- DDVP+AP-treated showing no expression of Caspase3 inthe cytoplasm of cardiac muscle. DDVP: Dichlorvos; AP: Andrographis paniculata.

Fig. 8.

Graphical illustration of the effects of inhalation of DDVP and treatment with Andrographispaniculata on the heart.

3.4.4. Phytochemical analysis

The results of the qualitative phytochemical tests are displayed in Table 1. Aqueous extract of A. paniculata contained alkaloids, tannin, saponin, terpenoids, flavonoids, glycoside and phytosterol.

Table 1.

Phytochemical analysis of aqueous extract of Andrographispaniculata.

| Phytochemicals | Presence |

|---|---|

| Alkaloids | ++ |

| Tannin | ++ |

| Saponin | + |

| Terpenoids | ++ |

| Flavonoids | ++ |

| Protein | - |

| Glycoside | + |

| Phytosterol | + |

4. Discussion, conclusion, and recommendation

4.1. Discussion

People are now more exposed to environmental contaminants as a result of the ongoing usage of pesticides. These contaminants have negative health impacts that are both short-term and long-term. Pesticides' artificial ingredients could have long-term negative impacts on the ecosystem. Humans are also exposed to insecticides in dwellings, the entire toxicity profiles of which remain unknown. Dichlorvos (DDVP), a chemical that the WHO has designated as extremely hazardous and as class one (Class I) [66], builds up in people and has harmful impacts on many body organs [64].

The prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) is constantly rising despite the abundance of knowledge regarding them. This has created an immediate demand for new drug candidates that are safe, effective, and relatively affordable. Andrographis paniculata, a plant that has long been used to cure a variety of illnesses in traditional medicine, contains andrographolide, which has several medicinal benefits [61]. Its ability to block the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor has demonstrated its strong anti-inflammatory properties [17]. The plant also reduces the production of nitric oxide, which contributes to oxidative stress and inflammation [3], [69]. The Indian and Chinese traditional medicine systems have a long history of using A. paniculata as a hepatostimulant and hepatoprotective agent, and it was shown to prevent injury and death of liver cells following exposure to concanavalin-A [56]. Extracts of A. paniculata prevented the high expression of liver transaminases in the serum, which is the hallmark of ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity. Aqueous and ethanol extract of A. paniculata is effective against several bacterial strains. The antimicrobial activities of A. paniculata have been confirmed in Salmonella typhimurium, E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia, and several others [24], [70].

This study investigated the effect of aqueous extract of A. paniculata on dichlorvos-induced toxicity on the heart of male Wistar rats. This was done by assessing the cardiac enzyme activities, inflammatory markers, antioxidant markers, electro-cardiac function, and cardiac apoptosis markers, which act as the biomarkers for heart function and integrity, respectively. In this study, the aqueous extract of A. paniculata has been shown to have a cardioprotective effect in DDVP-induced cardiotoxicity. This is demonstrated by an enhanced antioxidant defense system, a reduction in left ventricular dysfunction and hemodynamic impairment, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and a prevention of myocyte injury marker enzyme leakage from the heart.

This study found that the administration of dichlorvos resulted in a significant alteration in cardiovascular variables, including increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and a corresponding decrease in heart rate (HR) and pulse pressure (PP). These findings are consistent with previous research on the effects of dichlorvos-induced cardiac injury on the heart [49]. Because of problems with left ventricular contraction, DDVP may stimulate the adrenergic response, which could alter cardiovascular factors. It has been shown that DDVP induction significantly reduced arterial blood pressure (DBP, SBP, and MAP) in rats according to the result of Jun et al. [26]. Nevertheless, the DDVP-induced change in cardiovascular characteristics was reversed by the administration of an aqueous extract of A. paniculata. The current findings support the earlier conclusions of Shreesh et al. [57], who noted that extract from Andrographis paniculata protected against cardiac damage caused by isoproterenol [57]. Tannins may be the reason for A. paniculata's ability to control blood pressure [18].

The study evaluated various electrocardiac functions, including P-duration, PR-interval, QRS-complex, QT-interval, and R-amplitude. Rats that were induced with DDVP showed aberrant electrocardiac function, as shown by a substantial increase in QT-interval and a non-significant difference in P-duration, PR-interval, QRS-complex, and R-Amplitude when compared to control rats (as depicted in Fig. 3a-e). It is possible that DDVP predisposes to ventricular arrhythmia (torsades de pointes) and the accompanying seizure, as evidenced by the reported DDVP-induced increase in QT-interval [11]. This may be a factor in the study's findings that DDVP causes a rise in arterial blood pressure and a drop in heart rate and pulse pressure. Nevertheless, administration of A. paniculata aqueous extract resulted in a considerable reduction of increased QT-interval with a non-significant difference compared to dichlorvos-induced rats. The administration of an aqueous extract of A. paniculata reversed this alteration. This reveals the extract's cardioprotective effect, which is similar to the findings by Charan Sahoo et al., [15].

Among other enzymes, the heart contains large concentrations of lactate dehydrogenase and creatine kinase. However, if metabolic damage occurs, these enzymes are detected in the extracellular matrix [55]. A more sensitive marker in the early stages of myocardial ischemia is serum creatine kinase activity. In addition, peak increases in lactate dehydrogenase are generally correlated with the degree of cardiac tissue damage [16], [71]. When assessing the integrity of the cardiac apparatus in medication biotransformation and metabolism, blood levels of creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase could be employed [10]. The increased LDH and CK-MB infer that DDVP induces cardiac injury [62]. This is consistent with earlier research that showed the cardiotoxic effects of insecticides and pesticides containing pyrethroids [50], [51]. Aqueous extract of A. paniculata significantly ameliorated this effect [2].

Oxidative stress is the primary factor responsible for causing damage to the heart. Antioxidant enzymes are widely acknowledged as the first line of defense against oxidative stressors in order to safeguard cellular integrity and prevent the onset of numerous degenerative illnesses. The overproduction of free radicals during oxidative stress has a profound impact on the status of the enzymatic antioxidant enzymes, particularly SOD, catalase (CAT), and GPx, as well as the non-enzymatic antioxidant, GSH. This impact varies depending on the degree of disruptions in the normal redox state within the cells. Inflammatory diseases, alcoholism, smoking-related disorders, ischemia diseases, and many other conditions are significantly impacted by oxidative stress [20], [30], [44]. In the current investigation, the overall decline in the levels of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants in the heart homogenates of rats treated with dichlorvos suggested a net suppression of the tissue's total antioxidant capacity. This supports other reports [4], [50], [51]. Antioxidant status significantly reversed after treatment with A. paniculata aqueous extract, suggesting the extract's potential for amelioration. This finding implies that the plant extract has bioactive components that can scavenge free radicals by giving them hydrogen ions, so reducing their ability to cause cellular harm. This confirms the aqueous extract of A. paniculata's protective effect against oxidative stress brought on by dichlorvos exposure. The observed improvement in cardiac function seen in Andrographis paniculata-treated animals may be due to its antioxidant ability [2].

Lipid peroxidation is a sensitive marker of oxidative stress, an essential pathogenic event in myocardial necrosis induced by DDVP. Cardiac damage intensity is reflected by increased MDA level, a lipid peroxidation end product [28], [31]. This study showed a rise in MDA level in the group treated with DDVP which was attenuated by Andrographis paniculata. The reduced amount of MDA in heart tissues may have been brought about by the increased activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and GPx. The extract's cardioprotective effects could have been caused by the efficient neutralization and scavenging of the free radicals that DDVP generated.

Inflammatory response is a key factor in developing various cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction [26]. Patients with cardiovascular diseases exhibit increased expression and plasma concentrations of inflammatory markers and mediators [14], [54], [9]. It is a known fact that oxidative stress and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can cause inflammation and vice versa. Most often, oxidative stress amplifies a range of inflammatory cell signaling pathway [44]. The onset and progression of cardiac dysfunction are mostly dependent on inflammatory markers such TNF-α, IL-6, and MPO, which were significantly elevated after exposure to DDVP. The DDVP-induced increase in cardiac inflammatory markers may be due to DDVP-induced oxidative stress [6]. This may account for the increased cardiac injury markers and alterations in electro-cardiac function. The results are consistent with other studies showing that, despite DDVP's persistent binding and inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity, the majority of its detrimental biological effects are mediated by oxidative stress [25], [65]. Administration of aqueous extract of A. paniculata significantly decreases cardiac inflammatory markers compared to dichlorvos-induced rats. The cardiac cytoprotection conferred by A. paniculata likely prevented inflammatory response in the cardiac tissue [6].

Cardiac apoptosis markers such as caspase 3 were assessed in this study. The increase in cardiac caspase 3 caused by DDVP infers that DDVP induces cardiac apoptosis [6]. DDVP likely triggered cardiac proton pump dysfunction with increased intracellular calcium ions, resulting in DNA fragmentation and cell death [6]. This may be because DDVP can cause inflammation and oxidative damage, which are known mediators of apoptosis [22], [47]. The administration of aqueous extract of A. paniculata likely abrogated caspase 3 by preventing cardiac oxidative injury and inflammatory response. The potential of A. paniculata's aqueous extract to protect against cardiotoxicity caused by DDVP could be explained by this.

4.2. Limitation

This study has some limitations and the primary constraint on this research is the challenge of determining the precise dosage of pesticide that humans are exposed to during a single application; the dosage used in this study cannot directly be related to human exposure. However, the behavioral pattern of humans following insecticide use, which means humans are exposed to a minute amount of insecticide in a single use, was considered, and the rats were exposed to a low dose of insecticide. This study draws strength from its methodology and a wide array of investigations. The study reported organophosphate's overall and specific effects on cardiovascular function, inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and cardiac architecture.

5. Conclusion

DDVP-induced cardiotoxicity via oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Aqueous extract of A. paniculata confers cardioprotection against DDVP-induced cardiotoxicity by enhancing cardiac antioxidants. By restoring cardiac hemodynamic and contractile function, enhancing endogenous antioxidant defense, and inhibiting lipid peroxidation, the current findings highlight the therapeutic effects of A. paniculata's aqueous extract in an integrated approach. The study also showed that whole herb extract might be used for prophylaxis and treatment of CVD, as well as for excellent symptom relief. It is thought that the presence of phytochemicals, or tannins, or that the action of the plant as a whole inhibits lipid peroxidation or increases the activities of enzymatic antioxidants, is what makes the whole herb helpful against cardiovascular disease, inflammation, and apoptosis in the cardiac tissue.

Recommendation

Further molecular studies demonstrating other possible mechanisms of DDVP-induced cardiac dysfunction are suggested. Studies exploring the beneficial effects of molecules other than Andrographis paniculata in DDVP-induced cardiotoxicity are also suggested.

Abbreviation

CVD: Cardiovascular disease; WHO: World Health Organization; B.P: blood pressure; LDL: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Ops: organophosphates; DDVP: Dichlorvos; ECG: Electrocardiography; MAP: mean arterial pressure; PP: pulse pressure; CK-MB: creatinine kinase isoenzyme; LDH; lactate dehydrogenase; SOD: superoxide dismutase; GPx: Glutathione peroxidase; MDA: malondialdehyde; GSH: reduced glutathione; MPO: Myeloperoxide; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL-6: Interleukin-6; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; CAT: catalase; ROS; reactive oxygen species; A. paniculata: Andrographis paniculata.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All necessary approval was obtained from the Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Saka Waidi Adeoye: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Olusanjo A. Ayandele: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft. Oladapo Olusegun Oladipo: Project administation, Writing - review & editing, final approval. Olamilekan S. Adeshina: Conceptualization, Funding acqusition, Writing - original draft, Project administration. Busuyi David Kehinde: Investigation, Validation and analysis

Consent for publication

All authors agree to the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all authors whose publications were used in preparing this manuscript.

Handling Editor: Prof. L.H. Lash

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Adaramola Feyisara, Benjamin Goodluck, Oluchi O., Fapohunda Stephen. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of crude methanol extract and fractions of Andrographispaniculata leaf (Family: Acanthaceae) (Burm. f.) wall. Ex Nees. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2018;11:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeoye B.O., Ajibade T.O., Oyagbemi A.A., Omobowale T.O., Yakubu M.A., Adedapo A.D., Ayodele A.E., Adedapo A.A. Cardioprotective effects and antioxidant status of Andrographis paniculata in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. J. Med. Plants Econ. Dev. 2004;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adiguna S.P., Panggabean J.A., Swasono R.T., Rahmawati S.I., Izzati F., Bayu A., Putra M.Y., Formisano C., Giuseppina C. Evaluations of andrographolide-rich fractions of Andrographis paniculata with enhanced potential antioxidant, anticancer, antihypertensive, and anti-inflammatory activities. Plants. 2023;12(6):1220. doi: 10.3390/plants12061220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed M.A., Hassanein K.M. Cardio protective effects of Nigella sativa oil on lead induced cardio toxicity: anti inflammatory and antioxidant mechanism. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. 2013;4(5):72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akamo A.J., Ojelabi A.O., Somade O.T., Kehinde I.A., Taiwo A.M., Olagunju B.A., Akinsanya M.A., Adebisi A.A., Adekunbi T.S., Adenowo A.F., Anifowose F., Ajagun-Ogunleye O.M., Eteng O.E., Akintunde J.K., Ugbaja R.N. Hesperetin-7-O-rhamnoglucoside ameliorates dichlorvos-facilitated cardiotoxicity in rats by counteracting ionoregulatory, ion pumps, redox, and lipid homeostasis disruptions. Toxicol. Rep. 2024;19(13) doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2024.101698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhigbe R., Ajayi A. Testicular toxicity following chronic codeine administration is via oxidative DNA damage and up-regulation of NO/TNF-α and caspase 3 activities. PLoS One. 2020;15(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhigbe R.E., Ajayi A.F., Ram S.K. Oxidative stress and cardiometabolic disorders. BioMed. Res. Int. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/9872109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akhigbe R.E., Hamed M.A. Co-administration of HAART and antikoch triggers cardiometabolic dysfunction through an oxidative stress-mediated pathway. Lipids Health Dis. 2021;20:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12944-021-01493-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alfaddagh A., Martin S.S., Leucker T.M., Michos E.D., Blaha M.J., Lowenstein C.J., Jones S.R., Toth P.P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020;21 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2020.100130. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alnahd H.S. Effect of Rosmarinus officinalis extract on some cardiac enzymes of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Health Sci. 2012;2(4):33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambhore A., Teo S.G., Omar A.R.B., Poh K.K. ECG series. Importance of QT interval in clinical practice. Singap. Med. J. 2014;55(12):607. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2014172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azeez O.M., Adah S.A., Olaifa F.H., Basiru A., Abdulbaki R. The ameliorative effects of Moringa oleifera leaf extract on cardiovascular functions and osmotic fragility of wistar rats exposed to petrol vapour. Sokoto J. Vet. Sci. 2017;15(2):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azeez O.M., Akhigbe R.E., Ige S.F., Saka W.A., Anigbogu C.N. Variability in cardiovascular functions and baroflex sensitivity following inhalation of petroleum hydrocarbons. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. Res. 2012;3(2):99–103. doi: 10.4103/0975-3583.95361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blake G.J., Ridker P.M. Novel clinical markers of vascular wall inflammation. Circ. Res. 2001;89(9):763–771. doi: 10.1161/hh2101.099270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charan Sahoo K., Arora S., Goyal S., Kishore K., Ray R., Chandra Nag T., Singh Arya D. Cardioprotective effects of benazepril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, in an ischaemia-reperfusion model of myocardial infarction in rats. J. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2009;10(4):201–209. doi: 10.1177/1470320308353059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjea M.N., Shinde R. Textbook of Medical Biochemistry (5th ed.) Jappe brothers. Med. Publ. Ltd; New Delhi: 2002. Serum enzymes in heart diseases; pp. 555–557. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chun J.Y., Tummala R., Nadiminty N., Lou W., Liu C., Yang J., Evans C.P., Zhou Q., Gao A.C. Andrographolide, an herbal medicine, inhibits interleukin-6 expression and suppresses prostate cancer cell growth. Genes Cancer. 2010;1(8):868–876. doi: 10.1177/1947601910383416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung K.T., Wong T.Y., Wei C.I., Huang Y.W., Lin Y. Tannins and human health: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998;38(6):421–464. doi: 10.1080/10408699891274273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai Y., Chen S.R., Chai L., Zhao J., Wang Y., Wang Y. Overview of pharmacological activities of Andrographis paniculata and its major compound andrographolide. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;59(sup1):S17–S29. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1501657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dailiah Roopha, Padmalatha C. Effect of herbal preparation on heavy metal (cadmium) induced antioxidant system in female Wistar rats. J. Med. Toxicol. 2012;8(2):101–107. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0194-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan W.R., Garner D.S., Williams S.D., Funckes-Shippy C.L., Spath I.S., Blomme E.A. Comparison of immunohistochemistry for activated caspase-3 and cleaved cytokeratin 18 with the TUNEL method for quantification of apoptosis in histological sections of PC-3 subcutaneous xenografts. J. Pathol.: A J. Pathol. Soc. Great Britain Ireland. 2003;199(2):221–228. doi: 10.1002/path.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007;35(4):495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eroğlu S., Pandir D., Uzun F.G., Bas H. Protective role of vitamins C and E in dichlorvos-induced oxidative stress in human erythrocytes in vitro. Biol. Res. 2013;46(1):33–38. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602013000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hossain S., Urbi Z., Karuniawati H., Mohiuddin R.B., Moh Qrimida A., Allzrag A.M.M., Ming L.C., Pagano E., Capasso R. Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Wall. ex Nees: an updated review of phytochemistry, antimicrobial pharmacology, and clinical safety and efficacy. Life (Basel) 2021;16(4):348. doi: 10.3390/life11040348. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imam A., Ogunniyi A., Ibrahim A., Abdulmajeed W.I., Oyewole L.A., Lawan A.H., Sulaimon F.A., Adana M.Y., Ajao M.S. Dichlorvos induced oxidative and neuronal responses in rats: mitigative efficacy of Nigella sativa (black cumin) Niger. J. Physiol. Sci. 2018;33(1):83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J., Chen L., Lu H. Cardioprotective effect of salvianolic acid B against isoproterenol-induced inflammation and histological changes in a cardiotoxicity rat model. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2018;17(11):2189–2197. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalil M.I., Ahmmed I., Ahmed R., Tanvir E.M., Afroz R., Paul S., Gan S.H., Alam N. Amelioration of isoproterenol-induced oxidative damage in rat myocardium by Withania somnifera leaf extract. BioMed. Res. Int. 2015;2015(1) doi: 10.1155/2015/624159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar S., Singh B., Bajpai V. Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Nees: traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological properties and quality control/quality assurance. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021;15(275) doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lobo V., Patil A., Phatak A., Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010;4(8):118. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddock C., Pariante C.M. How does stress affect you? An overview of stress, immunity, depression and disease. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2001;10(3):153–162. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00005285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masaenah E., Elya B., Setiawan H., Fadhilah Z., Wediasari F., Nugroho G.A., Mozef T. Antidiabetic activity and acute toxicity of combined extract of Andrographis paniculata, Syzygium cumini, and Caesalpinia sappan. Heliyon. 2021;7(12) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mozaffarian D., Wilson P.W., Kannel W.B. Beyond established and novel risk factors: lifestyle risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117(23):3031–3038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.738732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mussard E., Jousselin S., Cesaro A., Legrain B., Lespessailles E., Esteve E., Berteina-Raboin S., Toumi H. Andrographis paniculata and its bioactive diterpenoids protect dermal fibroblasts against inflammation and oxidative stress. Antioxidants. 2020;9(5):432. doi: 10.3390/antiox9050432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagajothi S., Mekala P., Raja A., Raja M.J., Senthilkumar P. Andrographis paniculata: qualitative and quantitative phytochemical analysis. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018;7(4):1251–1253. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nasir A., Abubakar M.G., Shehu R.A., Aliyu U., Toge B.K. Hepatoprotective effect of the aqueous leaf extract of Andrographis paniculata Nees against carbon tetrachloride–induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Niger. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2013;21(1):45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neylon J., Fuller J.N., van der Poel C., Church J.E., Dworkin S. Organophosphate insecticide toxicity in neural development, cognition, behaviour and degeneration: insights from zebrafish. J. Dev. Biol. 2022;10(4):49. doi: 10.3390/jdb10040049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oboh A., Uwaifo F., Gabriel O.J., Uwaifo A.O., Ajayi S.A.O., Ukoba J.U. Multi-organ toxicity of organophosphate compounds: hepatotoxic, nephrotoxic, and cardiotoxic effects. Int. Med. Sci. Res. J. 2024;4(8):797–805. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogundola A.F., Akhigbe R.E., Saka W.A., Adeniyi A.O., Adeshina O.S., Babalola D.O., Akhigbe T.M. Contraceptive potential of Andrographis paniculata is via androgen suppression and not induction of oxidative stress in male Wistar rats. Tissue Cell. 2021;73 doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2021.101632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogunlana O.O., Adetuyi B.O., Esalomi E.F., Rotimi M.I., Popoola J.O., Ogunlana O.E., Adetuyi O.A. Antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of the twigs of andrograhis paniculata on streptozotocin-induced diabetic male rats. BioChem. 2021;1(3):238–249. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owoade A.O., Alausa A.O., Adetutu A., Owoade A.W. Protective effects of methanolic extract of Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees leaves against arsenic-induced damage in rats. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022;46(1):141. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson J.N., Patel M. The role of oxidative stress in organophosphate and nerve agent toxicity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016;1378(1):17–24. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prabu S.M., Muthumani M., Shagirtha K. Quercetin potentially attenuates cadmium induced oxidative stress mediated cardiotoxicity and dyslipidemia in rats. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2013;17(5):582–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajanna M., Bharathi B., Shivakumar B.R., Deepak M., Prabakaran D., Vijayabhaskar T., Arun B. Immunomodulatory effects of Andrographis paniculata extract in healthy adults–an open-label study. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2021;12(3):529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2021.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Redza-Dutordoir M., Averill-Bates D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1863(12):2977–2992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Picones R.P., Macadangdang R.R., Solitario J.M.A.L., Aguilar M.J.F., Chang M.P., Pangilinan N.M., Regulado J.A.M., Salazar B.Z.S. Hypoglycemic effect of Andrographis paniculata extract in alloxan induced albino wistar rats: a systematic review. Asian J. Biol. Life Sci. 2021;10(2):225. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saka W.A., Adeshina O.A., Yusuf M.G., Omole A.I. Hepatoprotective and renoprotective effect of Moringa oleifera seed oil on dichlorvos-induced toxicity in male Wistar rats. Niger. J. Physiol. Sci. 2022;37:119–126. doi: 10.54548/njps.v37i1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saka W.A., Akhigbe R.E., Abidoye A.O., Dare O.S., Adekunle A.O. Suppression of uric acid generation and blockade of glutathione dysregulation by L-arginine ameliorates dichlorvos-induced oxidative hepatorenal damage in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;138 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saka W.A., Ayoade T.E., Akhigbe T.M., Akhigbe R.E. Moringa oleifera seed oil partially abrogates 2, 3-dichlorovinyl dimethyl phosphate (Dichlorvos)-induced cardiac injury in rats: evidence for the role of oxidative stress. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021;32(3):237–246. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2019-0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saka W.A., Oyekunle O.S., Akhigbe T.M., Oladipo O.O., Ajayi M.B., Adekola A.T., Omole A.I., Akhigbe R.E. Andrographis paniculata improves glucose regulation by enhancing insulin sensitivity and upregulating GLUT 4 expression in Wistar rats. Front. Nutr. 2024;11:31. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1416641. 1416641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sankar K.D. Protective role of aqueous extract of Andrographis paniculata Nees on chromium-induced membrane damage. IJIRT. 2021;8(6) 2349-6002. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sesso H.D., Buring J.E., Rifai N., Blake G.J., Gaziano J.M., Ridker P.M. C-reactive protein and the risk of developing hypertension. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003;290:2945–2951. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma M.K., Kishore S.K., Gupta S.J., Arya D.S. Cardioprotective potential of Ocimum sanctum in isoprotenol induced myocardiac infarction in rats. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001;225:75–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1012220908636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi G., Zhang Z., Zhang Protective effect of andrographolide against concanavalin A-induced liver injury. Naunyn’s Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2012;385(1):69–79. doi: 10.1007/s00210-011-0685-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shreesh O., Saurabh B., Mahaveer G., Ashok K.S., Neha R., Santosh K., Dharamvir S.A. Andrographispaniculataextract protect against Isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury by mitigating Cardiac dysfunction and oxidative injury in rats. Acta Pol. Pharm. Drug Res. 2012;69(2) 269-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh B., editor. Botanical leads for drug discovery. Springer; 2020. pp. 363–387. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Subramaniam S., Hedayathullah Khan H.B., Elumalai N., Sudha Lakshmi S.Y. Hepatoprotective effect of ethanolic extract of whole plant of Andrographis paniculata against CCl 4-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2015;24:1245–1251. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sule R.O., Condon L., Gomes A.V. A common feature of pesticides: oxidative stress-the role of oxidative stress in pesticide-induced toxicity. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/5563759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan W.D., Peh H.Y., Liao W., Pang C.H., Chan T.K., Lau S.H. Cigarette smoke-induced lung disease predisposes to more severe infection with nontypeableHaemophilusinfluenzae: protective effects of andrographolide. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;79(5):1308–1315. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tonomura Y., Mori Y., Torii M., Uehara T. Evaluation of the usefulness of biomarkers for cardiac and skeletal myotoxicity in rats. Toxicology. 2009;266(1-3):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsitsimpikou C., Tzatzarakis M., Fragkiadaki P., Kovatsi L., Stivaktakis P., Kalogeraki A., Kouretas D., Tsatsakis A.M. Histopathological lesions, oxidative stress and genotoxic effects in liver and kidneys following long term exposure of rabbits to diazinon and propoxur. Toxicology. 2013;307:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.11.002. 2013;10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y., Chen G., Yu X., Li Y., Zhang L., He Z., Zhang N., Yang X., Zhao Y., Li N., Qiu H. Salvianolic acid B ameliorates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibiting TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway. Inflammation. 2016;39(4):1503–1513. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.WHO: World Health Organization (1992). International Programme on chemical safety. WHO recommended classification of pesticide by hazards and guidelines to classification 1994–1995, UNEP/ILO/WHO.

- 67.World Health Organization (2017). Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) (World Health Organization). Available: 〈https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/〉 detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(CVDs) [Accessed 26-06-2019].

- 68.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Published 2021. 〈https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-%28cvds%29?utm〉.

- 69.Wu H., Wu X., Huang L., Ruan C., Liu J., Chen X., et al. Effects of andrographolide on mouse intestinal microflora based on high-throughput sequence analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.702885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zaidi F.H., Mohtar S.H. A review on the evaluation of antimicrobial properties of crude extracts and bioactive compounds derived from Andrographis paniculata. ASEAN J. Life Sci. 2021;1(2):68–73. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang H., Kang K., Chen S., Su Q., Zhang W., Zeng L., Lin X., Peng F., Lin J., Chai D. High serum lactate dehydrogenase as a predictor of cardiac insufficiency at follow-up in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024;117 doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2023.105253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang L., Bao M., Liu B., Zhao H., Zhang Y., Ji X., Zhao N., Zhang C., He X., Yi J., Tan Y., Li L., Lu C. Effect of andrographolide and its analogs on bacterial infection: a review. Pharmacology. 2020;105(3-4):123–134. doi: 10.1159/000503410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ziaee M., Khorrami A., Ebrahimi M., Nourafcan H., Amiraslanzadeh M., Rameshrad M., Garjani M., Garjani A. Cardioprotective effects of essential oil of Lavandulaangustifolia on isoproterenol-induced acute myocardial infarction in the rat. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2015;14(1):279–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zou W., Xiao Z., Wen X., Luo J., Chen S., Cheng Z., Xiang D., Hu J., He J. The anti-inflammatory effect of Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees on pelvic inflammatory disease in rats through down-regulation of the NF-κB pathway. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016;16:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1466-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.