Abstract

Background

The rural-urban disparity in healthcare quality is a global issue. Compared with living in urban areas, living in rural areas is associated with poorer healthcare outcomes. Moreover, the shortage of healthcare providers in rural areas is a worldwide concern. This scoping review aims to map existing evidence regarding rural-urban disparities in access and quality of healthcare in Japan using the Donabedian model as a theoretical framework and to identify conceptual and measurement gaps.

Methods

This review targeted published articles and gray literature. We included documents that (1) were based on Japanese populations and (2) compared the quality of care between defined rural and urban areas. We excluded articles if they (1) were published during or before 2005 since the Japanese government amended the Medical Care Law in 2006; (2) focused exclusively on urban or rural areas; or (3) were not published in English or Japanese. This study employed PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, the Japanese medical literature database, ICHUSHI, and CiNii Research. We extracted quality indicators (structure, process, and outcomes) based on the Donabedian model. We recorded the definitions or indicators of rurality described by the studies.

Results

Out of 5,020 articles, 15 were included. Only one study was conducted in a primary care setting. Moreover, no study evaluated the “outcomes” of the Donabedian model in a primary care setting. Regarding the definitions or indices of rurality, the most commonly used indicator of rurality was population size, followed by population density. The cutoff values or descriptions of rurality using these indicators differed across studies.

Conclusion

This study mapped rural-urban disparities in access and quality of healthcare in Japan. These findings highlight the need to evaluate rural-urban disparities in the “outcomes” of care in primary care settings in Japan and the lack of common indicators of rurality.

Keywords: Healthcare, Japanese, Rurality index, Rural-urban, Scoping review

Introduction

Less than 1% of Japan’s total population lives on one of its 6800 islands [1], and another 11 million people reside in “depopulated areas.” Japan has a total population of 123 million [2]; thus the 11 million residents of depopulated areas represent 8.9% of all inhabitants. In addition, approximately 130,000 people live in “districts without a doctor” and have poor access to health care [1]. Rural-urban disparities in health status, healthy behaviors, and access to care are well documented worldwide [3–11]. Compared with their urban counterparts, rural residents are more likely to have obesity-related chronic diseases and have poorer physical and social functioning, mental health, self-reported health status [9], cancer survival [10], and overall quality of life [11]. They are less likely to report healthy behaviors than urban residents [3–5, 6] and have fewer visits to family physicians and specialists than urban residents [7, 8]. Rural communities also face challenges recruiting and retaining healthcare providers [12].

Rural-urban disparities in healthcare quality are a global issue, and healthcare providers, policymakers, and rural residents have attempted to address these challenges [13, 14]. An essential first step in addressing rural-urban healthcare disparities is developing a rurality index for healthcare research [1]. A previous scoping review of global literature reported rurality indices in healthcare research mainly measure access to healthcare, such as travel distance, time and cost to healthcare facility [1]. Thus, access and quality of healthcare is essential to assess rural-urban healthcare disparity.

Aims

This scoping review aims to map existing evidence regarding rural-urban disparities in access and quality of healthcare and to identify conceptual and measurement gaps in Japan. We classified these disparities using the Donabedian model, which is a framework for assessing quality of care comprising structure, process, and outcomes [15]. We opted for a scoping review given the limited number of anticipated studies, variances in research designs and methods, and the exploratory nature of the research question.

Methods

Study design

We designed this scoping review based on the framework described by Levac et al. and Arksey & O’Malley [16, 17]. We selected a scoping-review design because it systematically maps existing evidence and highlights gaps in the literature [16, 17]. The findings are reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols for Scoping Reviews framework [18]. This review targeted published peer-reviewed articles and gray literature, including government reports. We registered the protocol in the Open Science Framework a priori: https://osf.io/af9vp/.

Setting

The Japanese healthcare system

The Ministry of Labor, Health, and Welfare is responsible for overall healthcare administration in Japan [19]. Under central governance, local governments are responsible for the delivery of primary, secondary, and tertiary care [19]. Local governments comprise 47 prefectures and approximately 1,700 municipalities (e.g., cities, towns, and villages). Prefectures are responsible for secondary and tertiary care service areas and comprise 344 secondary and 52 tertiary medical regions [20]. Each municipality provides primary care services. Primary care is mainly offered in clinics, and secondary care is generally provided in hospitals.

Eligibility criteria

We developed inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify relevant articles from an initial database search. We included studies that (1) were based on primary quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods research, or gray literature; (2) were based on a Japanese population; and (3) compared the quality of care between defined rural and urban areas. Since the study focused on recent findings, we excluded studies published during or before 2005 or if they used data from before 2005 because the Japanese government amended the Medical Care Law in 2006, including prefectural governments being responsible for providing medical care in rural areas [21]. Additionally, we excluded studies that focused exclusively on urban or rural areas since our objective was to compare healthcare quality in urban and rural areas. Finally, we excluded studies targeting a country or region other than Japan and articles not written in English or Japanese. We resolved ambiguous information through discussion and consensus, with these decisions being documented. We developed the eligibility criteria a priori and shared the criteria and their interpretation and application to the search with all team members.

Information sources and search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search using PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science for articles published from January 1, 2006, to April 15, 2024. Moreover, we queried the Japanese medical literature databases ICHUSHI (https://www.jamas.or.jp/english/) and CiNii Research (https://cir.nii.ac.jp/?lang=en), as well as government websites [22–24].

The search terms for PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science were derived from the research questions and are listed in Table 1. The librarian at Yokohama City University participated in determining the search terms. We used Rayyan software to manage the references [25].

Table 1.

Search terms used in the scoping review

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (((“Rural Health Services“[MeSH Terms] OR (“rural“[Title/Abstract] AND “Health“[Title/Abstract]) OR “Rural Population“[MeSH Terms]) AND (“Urban Health Services“[MeSH Terms] OR (“urban“[Title/Abstract] AND “Health“[Title/Abstract]))) OR (“Healthcare Disparities“[MeSH Terms] OR “regional difference*“[Title/Abstract] OR “regional disparit*“[Title/Abstract] OR “regional variation*“[Title/Abstract] OR “regional gap“[Title/Abstract])) AND (“Japan“[MeSH Terms] OR “Japan“[Title/Abstract] OR “Japanese“[Title/Abstract]) |

| EMBASE | (((‘Rural Health Services’/exp OR (rural: ti, ab AND Health: ti, ab) OR ‘Rural Population’/exp) AND (‘Urban Health Services’/exp OR (urban: ti, ab AND Health: ti, ab))) OR (‘Healthcare Disparities’/exp OR ‘regional difference*’:ti, ab OR ‘regional disparit*’:ti, ab OR ‘regional variation*’:ti, ab OR ‘regional gap’:ti, ab)) AND (Japan/exp OR Japan: ti, ab OR Japanese[Title/de) |

| Web of Science | ((TI=(rural AND health) OR AB=(rural AND health)) AND (TI=(urban AND health) OR AB=(urban AND health)) OR (TI=(regional AND (Disparit* OR difference* OR variation* OR gap) AND Health) OR AB=(regional AND (Disparit* OR difference* OR variation* OR gap) AND Health))) AND (TI=(japan) OR AB=(japan)) AND (PY=(2006–2024)) |

Study selection/screening

In the first stage, two investigators (MK and RO) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the retrieved literature, with discrepancies being resolved through discussion. Rayyan software was used for the first stage [25]. In the second stage, the same investigators reviewed the full texts to identify the final list of studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. There was no need to contact the authors of the included studies, as no information required clarification.

Data charting/collection/extraction

The review extracted the following data from each source: year of publication, language, study design, setting (community/clinic/secondary hospital/tertiary hospital/long-term care), data source, sample size, definition/indices of rurality, indicators of healthcare quality (structure, process, and outcomes) based on Donabedian model [15], study outcome, covariates, and an overview of the results. The rules for data extraction and an example were shared with the research team. Two investigators (MK and RO) independently extracted the data, with discrepancies being resolved through discussion.

To situate our work within established quality‑of‑care theory, we adopted the Donabedian model [15]. In the model, “Structure” refers to the attributes of the service and provider, including physician-to-patient ratios and service times. “Process” reflects the work processes used to achieve the desired outcome, including whether patients receive standard care and staff wash their hands [15]. The “outcomes” include mortality, length of hospital stay, cost of care, and patient experience. The structure–process–outcome triad remains the most widely cited model in comparative health‑services research [26, 27] and aligns with recent WHO quality taxonomies [28]. Moreover, it accommodates access‑related indicators, which are central to rural–urban analyses. Alternative frameworks such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Triple Aim [29]” were considered; however, they emphasize population‑level goal‑setting rather than the indicator‑level mapping required for this scoping review. We operationalized the three domains as follows: (i) Structure = provider, facility, or system attributes (e.g., physician‑to‑population ratio); (ii) Process = care activities including adherence to guidelines or timeliness (e.g., door‑to‑balloon time); (iii) Outcome = patient‑level or population‑level results (e.g., mortality, life expectancy). One investigator (MK) assigned each study’s indicators to ≥ 1 domain and the remaining investigators checked the results.

Synthesis and presentation of results

We used a PRISMA flow diagram to describe the inclusion and exclusion of studies. We described the number and proportion of each category, such as the definition of rurality or types of indicators. The included studies were classified based on Donabedian’s model, and the results are summarized in Table 2. In this scoping review, the results of each source were not synthesized.

Table 2.

Scoping review studies investigating urban-rural disparities in the quality of healthcare in Japan

| Title | Year of publication | Language | Study design | Study setting: Level of care | Study setting: national/prefecture/city, town, village | Data source | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A regional difference in care burden feelings of family caregivers with frail elderly using visiting nurse [30] | 2007 | Japanese | Cross-sectional | Home-visit nursing service | One prefecture | Questionnaire | 167 families |

| Current situations and issues in respiratory medicine in Japan [31] | 2010 | English | Cross-sectional | Hospital | National | Questionnaire | 1251 hospitals |

| Geographic distribution of radiologists and utilization of teleradiology in Japan: A longitudinal analysis based on national census data [32] | 2015 | English | Cross-sectional | Municipality | National | Questionnaire | 1811 municipalities |

| Rural-urban disparity in emergency care for acute myocardial infarction in Japan [33] | 2018 | English | Prospective cohort | hospital | Prefecture | Registry | Rural: 1313 individuals、Metropolitan: 2,075 individuals |

| Geographical distribution of family physicians in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional study [34] | 2019 | English | Cross-sectional | Prefecture | National | Database of academic society | 527 family physicians |

| Geography of suicide in Japan: spatial patterning and rural-urban differences [35] | 2021 | English | Cross-sectional | Municipality | National | Suicide database | 240673 individuals |

| Regional and facility disparities in androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer from a multi-institutional Japan-wide database [36] | 2021 | English | Prospective cohort | Hospital | National | Japan Study Group of Prostate Cancer (J-CaP) | 19162 individuals |

| Differences in treatment and survival between elderly patients with thoracic esophageal cancer in metropolitan areas and other areas [37] | 2021 | English | Retrospective cohort | Prefecture | National | The national database of hospital-based cancer registries | 5066 individuals |

| Regional disparities in adherence to guidelines for the treatment of chronic heart failure [38] | 2021 | English | Prospective cohort | Hospital | Prefecture | Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Syndromes (ATTEND) | 387 individuals |

| Urban-rural inequalities in care and outcomes of severe traumatic brain injury: A nationwide inpatient database analysis in Japan [39] | 2022 | English | Retrospective cohort | Hospital | National | Diagnosis Procedure Combination(DPC) | 48910 individuals |

| Regional variation in national healthcare expenditure and health system performance in central cities and suburbs in Japan [40] | 2022 | English | Cross-sectional | Municipality | National | Open data | 23 urban municipalities and 27 rural municipalities |

| Disparity of performance measure by door-to-balloon time between a rural and urban area for management of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction - insights from the Nationwide Japan Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry [41] | 2023 | English | Retrospective cohort | Hospital | National | The Japan Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (JAMIR) | 17167 individuals |

| The inter-prefectural regional disparity of healthcare resources and representative surgical procedures in orthopedics and general surgery: a nationwide study in Japan during 2015–2019 [42] | 2023 | English | Cross-sectional | Prefecture | National | Nippon Data Base (NDB) Open data | 47 prefectures |

| Development and validation of a rurality index for healthcare research in Japan: a modified Delphi study [43] | 2023 | English | Cross-sectional | Municipality | National | Open data | 335 secondary medical areas and 1713 municipalities |

| Primary care physicians working in rural areas provide a broader scope of practice: a cross‑sectional study [44] | 2024 | English | Cross-sectional | Primary care clinic and hospital | National | Questionnaire | 299 primary care physicians |

| Title | Index or definition of rurality | Details of the index or definition of rurality: population size/density | Donabedian's model (structure, process, outcomes) | Study outcome | Covariates | Overview of results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A regional difference in care burden feelings of family caregivers with frail elderly using visiting nurse [30] | Urban: ordinance, designated cityRural: depopulated area | Not applicable | Outcomes | Care burden of family caregivers | Caregiver's age Caregiver's gender Duration of care Welfare services used Certification for long-term care/support needs, Activities of daily living | No difference in care burden of family caregivers |

| Current situations and issues in respiratory medicine in Japan [31] | Population size | Metropolitan areas (population ≥500000)Urban areas (200000 to 500000)Provincial areas (50000 to 200000)Rural areas (<50000) | Structure, process | Numbers of internists, respiratory physicians, respiratory specialistsScope of practice | Not applicable | Fewer respiratory specialists in rural areas than the Japanese average. Lower self-containment level (Scope of Practice) in rural areas than in urban areas. |

| Geographic distribution of radiologists and utilization of teleradiology in Japan: A longitudinal analysis based on national census data [32] | Ordinance designated city/special ward/city/town | Not applicable | Structure | Numbers of radiologists, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging | Not applicable | Fewer radiologists in rural areas than in urban areas. |

| Rural-urban disparity in emergency care for acute myocardial infarction in Japan [33] | Population size | Rural areas: prefecture with population <2 million | Process | Direct ambulance transport, onset-to-balloon time | Age, sex, mode of transport, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, current smoker, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, previous myocardial infarction, Killip classification at presentation, ST elevation myocardial infarction, multivessel disease and left anterior descending coronary artery lesion as the culprit | Less direct ambulance transportation in rural areas than in urban areas. Onset-to-balloon time in rural areas is longer than in urban areas. |

| Geographical distribution of family physicians in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional study [34] | Population densityOrdinance designated City/special ward/town | Municipalities divided into quintiles by population density | Structure | Number of family physicians per 100000 population | Not applicable | More family physicians in rural areas than any other specialists. |

| Geography of suicide in Japan: spatial patterning and rural-urban differences [35] | Population density | Municipalities divided into deciles sorted by population density | Outcomes | Number of suicides | Single-person households Unmarried adultsUnemployment rateEducational attainment | Men aged 0–39 and 40–59 years: rural residents had a higher suicide risk than urban residents. |

| Regional and facility disparities in androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer from a multi-institutional Japan-wide database [36] | Population density | Urban areas: prefectures with a population density >1000 persons/km2 | Outcomes | Cancer mortality All-cause mortality | Age, initial Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) value at pretreatmentGleason scoreClinical TNM-stageTherapeutic modality Regional area or facility type | Geographical regions (rural or urban) do not affect outcomes |

| Differences in treatment and survival between elderly patients with thoracic esophageal cancer in metropolitan areas and other areas [37] | Population size | Urban areas: a prefecture with >6 million population | Process, outcomes | Treatment strategy, mortality | Age, sex, first-line treatments | cStage I thoracic esophageal cancer mortality in rural areas is worse than in urban areas. |

| Regional disparities in adherence to guidelines for the treatment of chronic heart failure [38] | Authors-defined rural and urban areas | Process | Treatment rates for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) as recommended by guidelines | Not applicable | Treatment rates for HFrEF following guidelines were lower in rural areas than in urban areas. | |

| Urban-rural inequalities in care and outcomes of severe traumatic brain injury: A nationwide inpatient database analysis in Japan [39] | Population size | Urban areas (population ≥50000)Rural areas (10000 to 50000) | Outcomes | In-hospital mortality | Age, sex, fiscal year, and season of admission, admission on weekends or at night, referral from other institutions, ambulance use, smoking history, body mass index, comorbidities, Charlson comorbidity index, Japan Coma Scale score at admission, details of head injury (diffuse axonal injury, acute epidural hemorrhage, acute subdural hemorrhage, traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, contusion, skull fracture, penetrating injury), and injury severity score | Mortality by brain traumatic injury in rural areas is greater than that in urban areas. |

| Regional variation in national healthcare expenditure and health system performance in central cities and suburbs in Japan [40] | Population size | Metropolitan areas (population ≥500000)Suburb areas: three categories (100000 to 500000, 30000 to 100000, <30000) | Structure, process, outcomes | Total medical expenses of national healthcare experience: medical expenses of inpatients, medical expenses of outpatients, and consultation rates of inpatients and outpatients | Number of doctors, number of nurses, number of beds, income, number of people employed in primary industries, percentage of completely unemployed, percentage of population aged 65–74, number of household members, percentage of singles, percentage of households with own houses | The factors affecting medical care costs in suburban areas differ from those in metropolitan areas. |

| Disparity of performance measure by door-to-balloon time between a rural and urban area for management of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction - Insights from the Nationwide Japan Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry [41] | Population density | Municipalities divided by the median of population density | Process, outcomes | In-hospital death, door-to-balloon time | Both in-hospital death and door-to-balloon time are worse in rural areas than in urban areas. | |

| The inter-prefectural regional disparity of healthcare resources and representative surgical procedures in orthopedics and general surgery: a nationwide study in Japan during 2015–2019 [42] | Population size and density | Urban areas: large cities with a population >500000 and top seven prefectures with a high population density >1000 persons/km2. | Structure, process | Numbers of physicians and surgeries | Not applicable | Nonlarge cities had significantly more femur fracture surgeries, lower leg fracture surgeries, total knee arthroplasties, cholecystectomies, and hospitals than in large cities. Sparsely populated areas had significantly more femur fracture surgeries, lower leg fracture surgeries, total knee arthroplasties, cholecystectomies, orthopedic surgeon specialists, hospitals, and higher aging rates than densely populated areas. |

| Development and validation of a rurality index for healthcare research in Japan: a modified Delphi study [43] | Rurality index for Japan | Structure, outcomes | Indices for physician distribution and average life expectancy | Not applicable | The indices for physician distribution and average life expectancy are negatively correlated with rurality. | |

| Primary care physicians working in rural areas provide a broader scope of practice: a cross‑sectional study [44] | Rurality index for Japan | Process | Scope of practice | Sex, years of clinical experience, clinical setting (clinic or hospital), certification status, and experience of practice in rural areas | The scope of practice is broader in rural areas than in urban areas. |

Ethics approval and consent to participate

An ethics committee did not assess the study since we only used published literature or websites and did not handle personal information or human biological samples.

Results

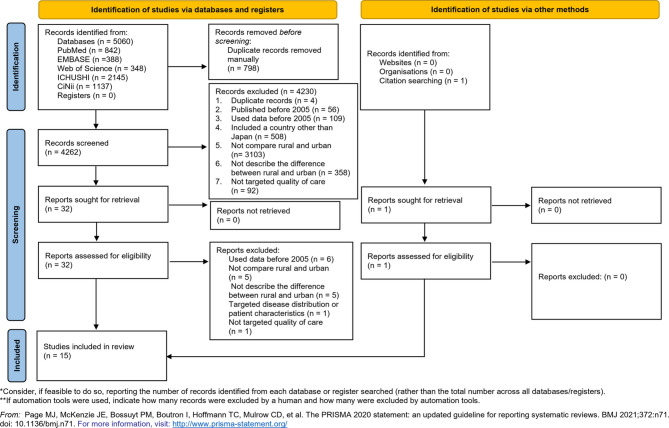

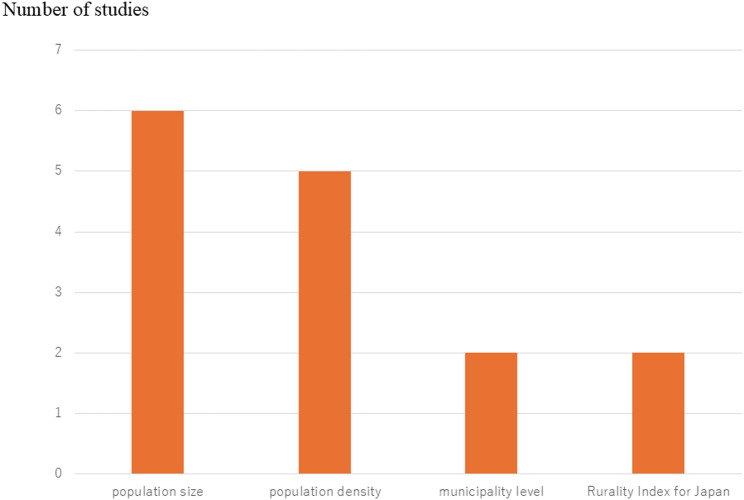

Among the 5,020 initially selected papers, 798 duplications were deleted. After screening the titles and abstracts, 4230 of the 4,262 studies were excluded. Among the remaining 32 papers, 14 were retained, and one paper was added following a review of reference lists. Finally, we included 15 studies [30–44]. The flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1. Figure 2 presents a Sankey diagram that visually maps each of the 15 included studies to the Donabedian domains they address.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the selection of studies in the scoping review

Fig. 2.

Sankey diagram of the included studies and the Donabedian domains they address. blue: structure, green: process, orange: outcomes

The extracted data are described in Table 2. Regarding study design, all included studies were observational studies, and nine (60.0%) [30–35, 40, 42–44] were cross-sectional studies. Furthermore, 12 (80.0%) studies [31, 32, 34–37, 39–44] targeted all of Japan, whereas the other three (20%) articles [30, 33, 38] focused on one or several prefectures and compared outcomes among these areas. Only one study [44] targeted clinic-level primary care, with the others focusing on secondary or tertiary hospital care. Although urban areas are usually associated with better quality, some outcomes, such as the number of family physicians per 100,000 persons [34] or the scope of practice in primary care [44], were better in rural areas.

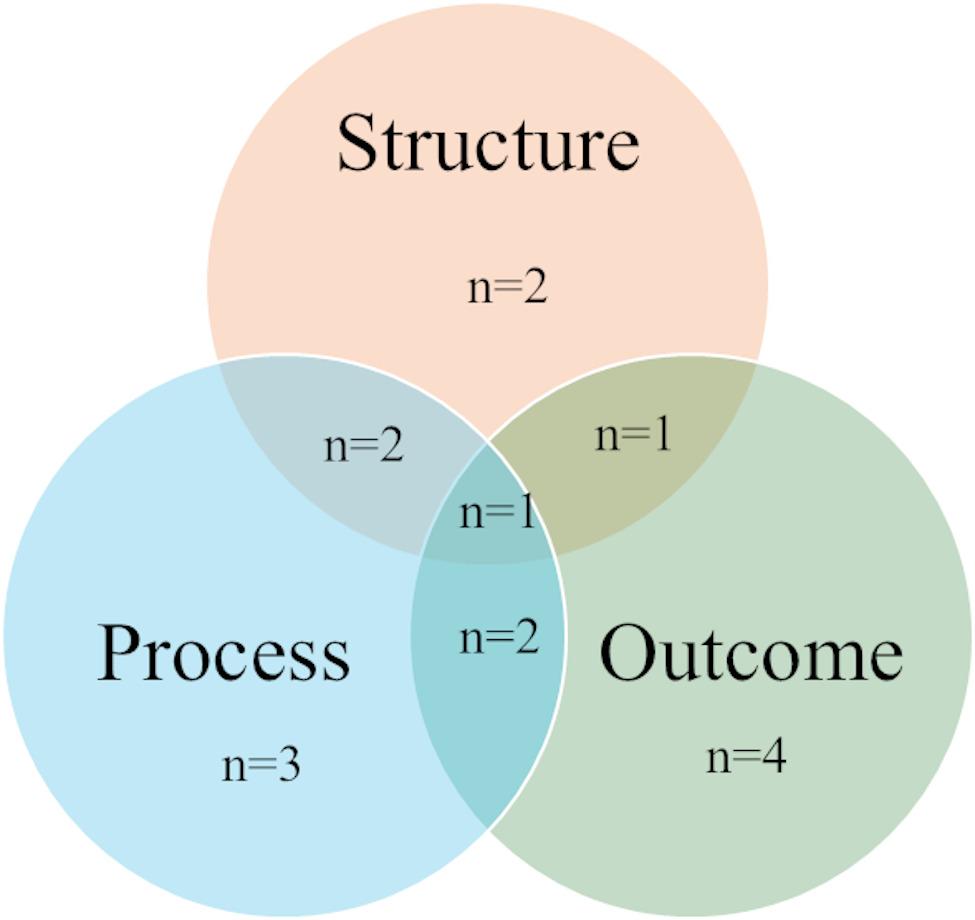

Types of quality of care

Figure 3 shows the breakdown of the domains of Donabedian’s model applied in the included studies. Four studies (26.7%) [30, 35, 36, 39] assessed the “outcomes” of the model. Five studies (33.3%) [31, 33, 34, 41, 42] evaluated two domains: “structure” and “outcomes” or “process” and “outcomes.” One study (6.7%) targeted all three domains [40]. However, no studies evaluated “outcomes” in primary care settings. For example, some studies compared the numbers of internists and respiratory specialists or radiologists (“structure”), revealing fewer of these physicians in rural areas than in urban areas [31, 32]. Other studies targeted “processes,” such as onset-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction or the rates of those who received guideline-recommended treatments for heart failure [33, 38, 41]. These processes were better in urban areas [33, 38, 41]. In terms of “outcomes,” the number of suicides among specific populations and average life expectancy tended to be worse in rural areas [35, 43]. In-hospital mortality from severe traumatic injury and acute myocardial infarction is also higher in rural areas [35, 43]. Although 9 of 15 studies reported poorer healthcare quality in rural areas and three reported no difference, three studies reported better healthcare quality in rural areas, such as more family physicians (“structure”), more general and orthopedic surgeries (“process”), and a broader scope of practice (“process”) in rural areas [34, 42, 43].

Fig. 3.

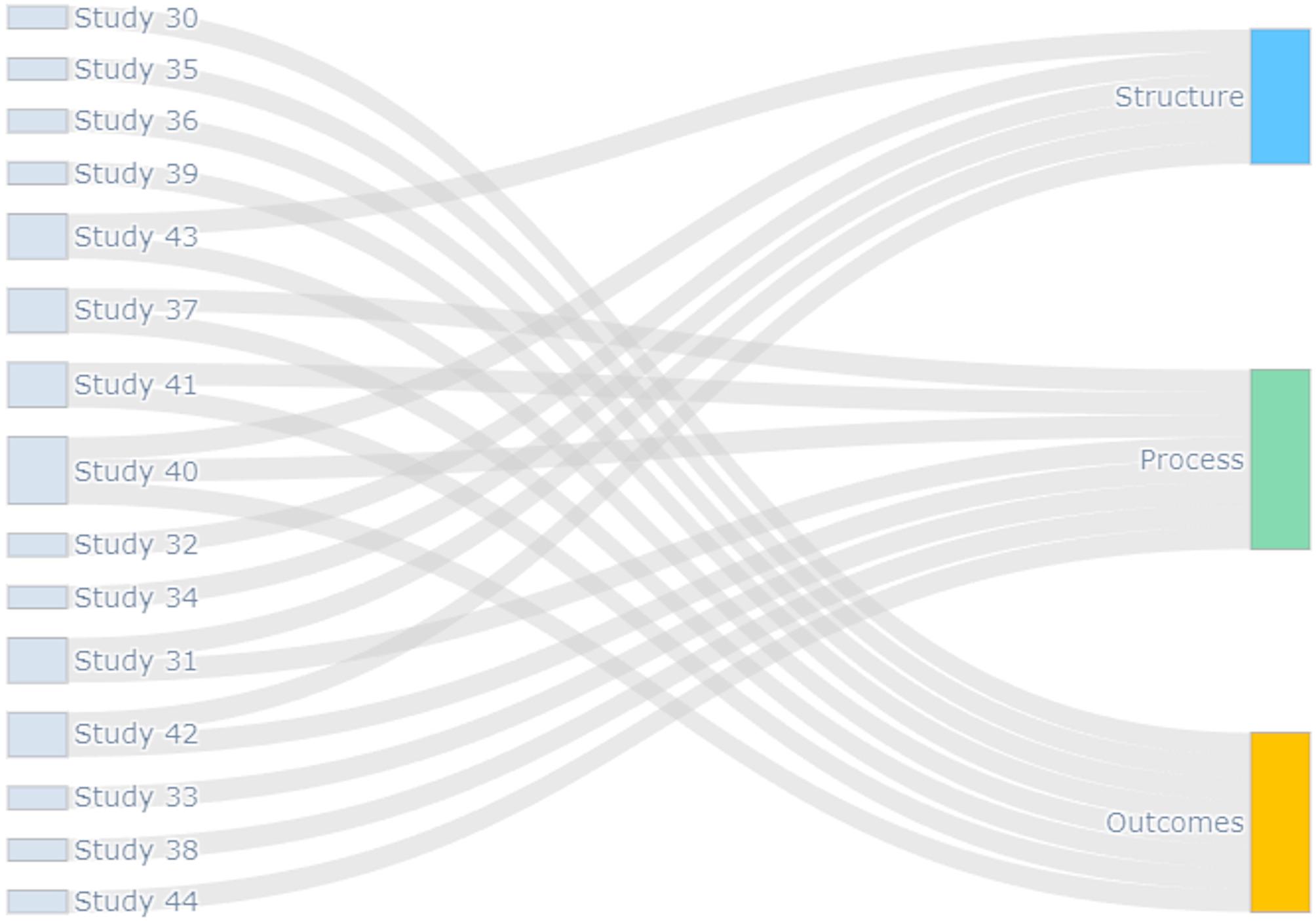

Definitions or indices of rurality used in the included studies

Index or definition of rurality

Population size was the most commonly used indicator of rurality in the included studies (six studies: 40%) [31, 33, 37, 39, 40, 42], followed by population density (five studies: 33.3%) [34–36, 41, 42]. Figure 4 shows the number of indicators of rurality used in the included studies. Some studies employed multiple indicators, such as population size and population density [42] or population density and administrative division (city/town/village) [34]. Furthermore, each study used population size/density differently to define rurality. The rurality index for Japan (RIJ), published in 2023, was used in two studies (13.3%) [43, 44]. One study defined rurality without using existing indicators or describing any rationale for the definitions used [38].

Fig. 4.

Breakdown of domains of the Donabedian model

Discussion

This review aims to map recent evidence about rural-urban disparities in terms of access and quality of care and to identify conceptual and measurement gaps in Japan. Only one study was conducted in a primary care setting [43]. Moreover, no study has evaluated the “outcomes” domain of the Donabedian model in primary care settings. Although population size was the most commonly used indicator of rurality in this scoping review, the extracted indicators varied and diverse cutoff values were used. The lack of a shared and well-defined rural indicator in the Japanese setting is an important finding of the scoping review.

Regarding the domains of the Donabedian model, two studies [32, 34] assessed “structure”, three [33, 38, 43] evaluated “process”, and four [30, 35, 36, 39] targeted “outcomes”. In addition, five studies [31, 33, 34, 41, 42] assessed two domains, and one examined all three domains [40]. Since the three domains interact, assessing rural-urban disparity from multiple perspectives is vital for improving the access and quality of care. Although the Donabedian model provides a structured lens for analysis, the absence of harmonized definitions and standardized indicators across studies prevents meaningful comparison and limits the generalizability of findings. This gap highlights a critical need for developing consensus measures tailored to the Japanese health system. Moreover, in this scoping review, only one paper investigated a clinic in a primary care setting [44]. This may be partly attributed to the limited number and impact of clinical studies on Japanese primary care [45, 46]. Nonetheless, research evidence is critical for building strong primary health care [47]. For example, the access and quality of primary care should be assessed in rural and urban areas as an essential first step in reducing inequality.

The studies in this scoping review varied in their definitions of rurality. Although population size and density were commonly used as definitions or indices of rurality, studies used different cutoff values or descriptions of rurality. There were no studies that used the same definition or cutoff. For example, although four studies defined “urban” or “metropolitan” areas similarly (500,000 population in one municipality) [31, 38, 40, 42], they used different definitions of “rural.” Moreover, in terms of population density, one study used quintiles [34], and another study employed deciles [35]. Others set their cutoff as > 1000 persons/km2 [36]. Some studies have used the RIJ to highlight differences at the secondary healthcare level (life expectancy, physician distribution) [43] and at the primary-care level (scope of practice) [44]. The RIJ encompasses the population density of the location’s zip code, the direct distance to the nearest secondary or tertiary hospital, whether the location is a remote island, and whether heavy snow affects access to the nearest medical facility [43].

Defining and measuring rurality presents a significant methodological challenge internationally, as it is influenced by multiple context-dependent factors—such as commuting patterns, social context and access to essential services including internet connectivity and advanced medical care—which may vary according to the specific objectives of a given study [48]. Among them, access to healthcare facilities is a critical concern in health services research and utilized in rurality indices in many countries [1, 49]. In Japan, the RIJ was developed in 2023 as a composite indicator for healthcare research incorporating access factors such as distance to the nearest hospital and degree of geographical isolation [43]. The included variables were selected through a modified Delphi process, and both convergent and criterion-related validity were established by examining correlations with physician distribution and average life expectancy [43]. The RIJ has been increasingly applied in Japanese healthcare research—for example, in studies assessing rurality in relation to functional outcomes following acute stroke after the study period covered by this scoping review [50]. Similar to rurality indices developed in Australia [51] and Ontario, Canada [52], the RIJ considers local context-related healthcare access and is well-suited for health-related studies. While the RIJ includes geographic isolation and hospital distance, additional access-based indicators—such as travel time, transportation modes, or availability of specific services—may complement the RIJ in future refinements, as seen in frameworks like regional classifications in Australia [51] or Canada’s RIO-2008 [52].

Strengths of the study

This study maps rural-urban disparities in the access and quality of care in Japan. This is a comprehensive and reproducible literature review, including gray literature. Focusing on the access and quality of care and the definition or index of rurality used in the included studies may facilitate future research. Based on our previous scoping review that summarized rurality indices used in healthcare research across countries, such as Australia, Canada, and the United States, we acknowledge that the definitional challenges we identified in the Japanese context reflect a broader international issue [1]. In addition, by applying the Donabedian model to classify existing healthcare research, this study identified a notable lack of evidence on outcomes within the primary care setting. This approach may be applicable to other countries facing similar challenges, such as poorer health outcomes and workforce shortages in rural areas.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations. First, owing to the nature of a scoping review, we did not assess the quality of each study, which may influence the interpretation of the results. Second, although we focused on studies that defined and compared rural and urban areas, we may have missed descriptive studies that did not define rurality and urbanity.

Conclusions

This study mapped recent evidence about rural-urban disparities in the access and quality of care in Japan. Only one study targeted primary care settings, and no study evaluated the “outcome” domain of the Donabedian model in primary care settings. Although population size and density were the most frequently used indicators for defining and comparing rural and urban areas, there is no common indicators or cut-off of rurality. Further studies using consistent and reproducible indices for urbanity and rurality are warranted to assess rural-urban disparities in primary care settings in Japan.

Acknowledgements

We thank Chihiro Tanaka, Fumie Morimoto, and Mayumi Shibata, librarians at Medical Library, Yokohama City University, for their assistance in developing the search strategy. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. This study was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24K02670. The study sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviation

- RIJ

Rurality index for Japan

Authors' contributions

M.K. wrote the main manuscript and prepared Figures 1-4. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24K02670. The study sponsors had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis and interpretation; writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Data availability

All data is available from the published articles.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

An ethics committee did not assess the study since we only used published literature or websites and did not handle personal information or human biological samples.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kaneko M, Ohta R, Vingilis E, Mathews M, Freeman TR. Systematic scoping review of factors and measures of rurality: toward the development of a rurality index for health care research in Japan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):9. 10.1186/s12913-020-06003-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Bureau of Japan. Preliminary counts of population of Japan. 2025. Accessed 22 Apr 2025. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/index.html.

- 3.Patterson PD, Moore CG, Probst JC, Shinogle JA. Obesity and physical inactivity in rural America. J Rural Health. 2004;20(2):151–9. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishna S, Gillespie KN, McBride TM. Diabetes burden and access to preventive care in the rural united States. J Rural Health. 2010;26(1):3–11. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parks SE, Housemann RA, Brownson RC. Differential correlates of physical activity in urban and rural adults of various socioeconomic backgrounds in the united States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(1):29–35. 10.1136/jech.57.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michimi A, Wimberly MC. Associations of supermarket accessibility with obesity and fruit and vegetable consumption in the conterminous united States. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9:49. 10.1186/1476-072X-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey MM, Thiede call K, Klingner JM. Are rural residents less likely to obtain recommended preventive healthcare services? Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(3):182–8. 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang P, Tao G, Irwin KL. Utilization of preventive medical services in the united States: a comparison between rural and urban populations. J Rural Health. 2000;16(4):349–56. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yen IH, Michael YL, Perdue L. Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(5):455–63. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1050–7. 10.1002/cncr.27840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace AE, Lee R, Mackenzie TA, West AN, Wright S, Booth BM, et al. A longitudinal analysis of rural and urban Veterans’ health-related quality of life. J Rural Health. 2010;26(2):156–63. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson NW, Couper ID, De Vries E, Reid S, Fish T, Marais BJ. A critical review of interventions to redress the inequitable distribution of healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(2):1060. 10.22605/RRH1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strasser R. Rural health around the world: challenges and solutions. Fam Pract. 2003;20(4):457–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. WHO guideline on health workforce development, attraction, recruitment and retention in rural and remote areas. 2021. Accessed 22 Apr 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240024229. [PubMed]

- 15.NHS. A model for measuring quality care. Act Acad Published online. 2018;4. Accessed 26 July 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/qsir-measuring-quality-care-model.pdf.

- 16.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arksey H, O’malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato D, Ryu H, Matsumoto T, Abe K, Kaneko M, Ko M, et al. Building primary care in Japan: literature review. J Gen Fam Med. 2019;20(5):170–9. 10.1002/jgf2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakamoto H, Rahman M, Nomura S, Okamoto E, Koike S, Yasunaga H, et al. Japan health system review. 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259941.

- 21.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of changes of the Medical Care Law in 2006 (in Japanese). Accessed 22 Apr 2025. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2007/11/dl/s1105-2b.pdf.

- 22.Kazuhiko K. Research to promote rural healthcare in response to demographic trends and regional characteristics (in Japanese). https://mhlw-grants.niph.go.jp/project/158691. Accessed 22 Apr 2025.

- 23.The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey on no-doctor districts (in Japanese). Accessed 22 Apr 2025. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00450122&tstat=000001085875&cycle=0&tclass1val=0.

- 24.The Ministry of Health. Labour and Welfare. Rural health (in Japanese). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/shakaihosho/iryouseido01/pdf/kanrenjigyou-r.pdf. Accessed 22 Apr 2025.

- 25.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Endalamaw A, Khatri RB, Erku D, Nigatu F, Zewdie A, Wolka E, Assefa Y. Successes and challenges towards improving quality of primary health care services: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayanian JZ, Markel H. Donabedian’s lasting framework for health care quality. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):205–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. PHC measurement framework and indicators: monitoring health systems through a primary health care lens. Accessed 22 Apr 2025. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/health-services-performance-assessment/phc-measurement-framework-and-indicators.

- 29.Berwick, Donald, et al. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurasawa S, Yoshimasu K, Washio M, Miyai M, Miyashita K, Arai Y. A regional difference in care burden feelings of family caregivers with frail elderly using visiting nurse. Jpn J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;7:771–80. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura H, Toga H, Yamaya M, Mishima M, Nukiwa T, Kudo S. Current situations and issues in respiratory medicine in Japan. Jpn Med Assoc J. 2010;53(3):178–84. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto M, Koike S, Kashima S, Awai K. Geographic distribution of radiologists and utilization of teleradiology in Japan: A longitudinal analysis based on National census data. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0139723. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masuda J, Kishi M, Kumagai N, Yamazaki T, Sakata K, Higuma T, et al. Rural-urban disparity in emergency care for acute myocardial infarction in Japan. Circ J. 2018;82(6):1666–74. 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida S, Matsumoto M, Kashima S, Koike S, Tazuma S, Maeda T. Geographical distribution of family physicians in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):147. 10.1186/s12875-019-1040-6. Pubmed:31664903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshioka E, Hanley SJB, Sato Y, Saijo Y. Geography of suicide in Japan: Spatial patterning and rural-urban differences. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(5):731–46. 10.1007/s00127-020-01978-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiota M, Sumikawa R, Onozawa M, Hinotsu S, Kitagawa Y, Sakamoto S, et al. Regional and facility disparities in androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer from a multi-institutional Japan-wide database. Int J Urol. 2021;28(5):584–91. 10.1111/iju.14518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motoyama S, Maeda E, Iijima K, Anbai A, Sato Y, Wakita A, et al. Differences in treatment and survival between elderly patients with thoracic esophageal cancer in metropolitan areas and other areas. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(10):4281–91. 10.1111/cas.15070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuo Y, Yoshimine F, Fuse K, Suzuki K, Sakamoto T, Iijima K, et al. Regional disparities in adherence to guidelines for the treatment of chronic heart failure. Intern Med. 2021;60(4):525–32. 10.2169/internalmedicine.4660-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shibahashi K, Ohbe H, Yasunaga H. Urban-rural inequalities in care and outcomes of severe traumatic brain injury: a nationwide inpatient database analysis in Japan. World Neurosurg. 2022;163:e628–34. 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seo Y, Takikawa T. Regional variation in National healthcare expenditure and health system performance in central cities and suburbs in Japan. Healthc (Basel). 2022;10(6):968. 10.3390/healthcare10060968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fukui K, Takahashi J, Hao K, Honda S, Nishihira K, Kojima S, et al. Disparity of performance measure by door-to-balloon time between a rural and urban area for management of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction - insights from the nationwide Japan acute myocardial infarction registry. Circ J. 2023;87(5):648–56. 10.1253/circj.CJ-22-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kido M, Ikoma K, Kobayashi Y, Maki M, Ohashi S, Shoda K, et al. The inter-prefectural regional disparity of healthcare resources and representative surgical procedures in orthopaedics and general surgery: a nationwide study in Japan during 2015–2019. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):726. 10.1186/s12891-023-06820-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaneko M, Ikeda T, Inoue M, Sugiyama K, Saito M, Ohta R, et al. Development and validation of a rurality index for healthcare research in Japan: a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(6):e068800. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaneko M, Higuchi T, Ohta R. Primary care physicians working in rural areas provide a broader scope of practice: a cross-sectional study. BMC Prim Care. 2024;25(1):9. 10.1186/s12875-023-02250-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aoki T, Fukuhara S. Japanese representation in high-impact international primary care journals (in Japanese). Off J Jpn Prim Care Assoc. 2017;40(3):126–30. 10.14442/generalist.40.126. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watari T, Nakano Y, Gupta A, Kakehi M, Tokonami A, Tokuda Y. Research trends and impact factor on pubmed among general medicine physicians in Japan: A cross-sectional bibliometric analysis. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:7277–85. 10.2147/IJGM.S378662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaneko M, Oishi A, Matsui Y, Miyachi J, Aoki T, Mathews M. Research evidence is essential for the development of family medicine as a discipline in the Japanese healthcare system. BJGP Open. 2019;3(2):bjgpopen19X101650. 10.3399/bjgpopen19X101650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moloney M, Rubio J, Palencia I, Hollimon L, Mejia D, Seixas A. Rural health research in the 21st century: A commentary on challenges and the role of digital technology. J Rural Health. 2025;41(1):e12903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.RUPRI Health Panel. Access to Rural Health Care – A Literature Review and New Synthesis. Accessed 22 Apr 2025. https://rupri.org/wp-content/uploads/20140810-Access-to-Rural-Health-Care-A-Literature-Review-and-New-Synthesis.-RUPRI-Health-Panel.-August-2014-1.pdf.

- 50.Fujiwara G, Kondo N, Oka H, Fujii A, Kawakami K. Regional disparities in hyperacute treatment and functional outcomes after acute ischemic stroke in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2024;31(11):1571–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Modified Monash model discussion paper, rural classification technical working group. 2014. Accessed 9 Sep 2024. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e2f9/c4ade1f31fcf0dade9f0dab1758f7345a2c9.pdf.

- 52.Kralj B, Measuring Rurality. – RIO2008 BASIC: methodology and results. 2008. Accessed 9 Sep 2024. https://www.oma.org/wp-content/uploads/2008rio-fulltechnicalpaper.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available from the published articles.