Abstract

In green plants, chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b are the predominant pigments bound to light-harvesting proteins. While the individual characteristics of these chlorophylls are well understood, the advantages of their coexistence remain unclear. In this study, we establish a method to simulate excitation energy transfer within the entire photosystem II supercomplex by using network analysis integrated with quantum dynamic calculations. We then investigate the effects of the coexistence of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b by comparing various chlorophyll compositions. Our results reveal that the natural chlorophyll composition allows the excited energy to preferentially flow through specific domains that act as safety valves, preventing downstream overflow. Our findings suggest that the light-harvesting proteins in a photosystem II supercomplex achieve evolutionary advantages with the natural chlorophyll a/b ratio, capturing light energy efficiently and safely across various light intensities. Using our framework, one can better understand how green plants harvest light energy and adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Network analysis reveals that land plants can take functional advantage from heterogeneous chlorophylls in its photosystem.

INTRODUCTION

Chlorophylls (Chls) play a crucial role in photosynthesis by serving as the primary light harvesters that transfer energy to the reaction centers (RCs) of a photosystem, where charge separation takes place (1). Under conditions of excess light, however, Chls also participate in the thermal dissipation of excess excitation energy to prevent photooxidative damage (2). The light-harvesting system, thus, needs to be designed for both efficient light capture and effective photoprotection.

In land plants, a photosystem II supercomplex (PSII SC) contains peripheral light-harvesting antennae, each composed of three monomeric light-harvesting complex II (LHCII)—CP24, CP26, and CP29—and two LHCII trimers—M-LHCII and S-LHCII (Fig. 1A) (3). In this photosystem, while both Chls a and b are in LHCIIs, only Chl a exists in the core complex. Chl b can increase the light-harvesting efficacy of LHCIIs because of its higher absorption coefficient at specific wavelengths and a higher excited energy level than that of Chl a. Therefore, it might be desirable for LHCIIs to exclusively bind Chl b to achieve maximal excitation energy transfer (EET) efficiency due to the increased energy gap between Chls in LHCIIs and PSII core complexes. However, natural LHCIIs of land plants still maintain both Chl a and Chl b, the reason for which has yet to be elucidated.

Fig. 1. EET network analysis of natural PSII SC.

(A) Protein compositions and Chl distribution of the PSII SC. (B) Schematic representations of the Chl domains generated via excitonic coupling between Chls. (C) Excitation energy transfer (EET) network and site energies of Chl domains in the natural PSII SC. The size and color of the circles represent the number of Chls in the domain and its averaged site energy. The direction and line width of the arrows between the circles represent the direction and the relative rate constants for EET. The rate constants larger than 0.005 ps−1 (time constant of 200 ps) are shown to visualize dominant EET (fig. S1). (D) Excitation probability of domains at t = 0 due to random Chl excitation for EET simulation considering the charge separation by the special pairs and intrinsic dissipation processes of Chls. (E) Simulated ensemble probabilities of the excited states of Chls, charge separation, and intrinsic dissipation after initial excitation.

Because the determination of the crystal structure of LHCII (4), the EET dynamics among the pigments in this structure have been studied using various experimental and theoretical approaches. By combining quantum chemical and electrostatic methods, researchers have calculated excitonic couplings and site energies of Chls, showing good agreement with experimental data (5, 6). These results indicate a strong coupling between Chl b and Chl a, facilitating rapid EET from Chl b to Chl a. Furthermore, the existence of long-lived quantum coherence in an LHCII (7) and other photosynthetic antenna proteins such as the Fenna-Matthews-Olson (FMO) complex (8) has been revealed through two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy. This long-lived quantum coherence is proposed to enhance the energy transfer efficiency to the RC at physiological temperature (9). Recent studies have identified the importance of a noise-canceling network model for EET dynamics (10). Molecular mechanisms of photoprotective excitation quenching in LHCII have also been proposed, including the interaction between Chl and lutein (11) and the formation of charge transfer states within the Chl-carotenoid (12, 13) and Chl-Chl (14, 15) pairs. However, these analyses have focused on individual antenna protein molecules, with limited extension to the entire PSII SC using simplified interactions (16, 17). This limitation arises from the complex nature of the photosynthetic antenna system, which involves numerous pigments and prevents the application of conventional computational methods typically used for smaller proteins such as the combination of quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics with molecular dynamics simulations (18) or coarse-grained approaches (17, 19).

While the maturation of cryo–electron microscopy technology, near-atomic structures of many photosystem SCs, ranging from land plants to various algae, are now accessible (20). Addressing EET dynamics across the entire SC considering the structural information of these SCs could tackle previously unreachable critical issues. For example, analyzing how the mixed composition of Chls within LHCII affects its function as PSII antennae, as studied in this report, is one such issue. Because both Chl a and Chl b are crucial for forming natural LHCII (21), it is challenging to experimentally produce LHCII with various Chl compositions, making a computational approach more feasible.

This study presents a multidisciplinary approach to analyze the holistic EET dynamics across the entire PSII SC (22). Multiple EET domains were introduced by considering the quantum mechanical interactions within the LHCII molecules and PSII complexes. The holistic EET dynamics were then investigated by network science (23) that has been rapidly developed for the past 20 years to understand complex interactions (23, 24), including neuroscience (25), power engineering (26), sociology (27), and ecology (28). In a network, a node, which is also referred to as a vertex, represents an individual entity or unit. A link, which is also called an edge, embodies the relationship or interaction between the nodes. The specific nature of the node or link depends on the type of system under investigation. By modeling the EET as a network, we were able to disclose and visualize how energy flows between different Chl domains, which is essential to understand the efficiency and regulation of the light-harvesting system of the PSII SC. This approach represents one of the most feasible methods currently available to investigate the holistic EET dynamics among numerous Chls in the entire PSII SC, clarifying the contributions of individual components to the EET dynamics. Last, on the basis of various versions of EET networks that vary the ratio of Chls a to b, the advantages of the natural Chl composition in the PSII SC are discussed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The EET network of the natural PSII SC

To generate the natural EET network, we first estimated the EET rate constants between Chls in the natural PSII SC based on quantum dynamical methods. In this study, we analyzed the PSII SC [Protein Data Bank (PDB): 5XNL] of Pisum sativum, for which coordinates of all Chls a and b belonging to the SC are known with detailed structural information (19). The EET rate depends on the site energies of Chls and the delocalized exciton states between strongly coupled Chls (Fig. 1B). To appropriately simulate the EET between Chls for a wide range of distances, we adopted the concept of “domain” that corresponds to a group of strongly coupled Chls (29, 30). For proximal EET within a domain, we applied Redfield theory, which has been widely used for more accurately describing EET as the relaxation process of the excitons (31). The generalized Förster theory, which has been commonly used to describe long range EET (29, 32, 33), was applied to consider further EET between delocalized exciton states belonging to different domains.

We treated the EET information derived from this combined approach as a “network” and characterized it through network theory (20), which enables quantifying and simulating the dynamic process as interactions of “nodes” along with their topological characteristics (see Materials and Methods). In our EET network, the nodes are Chl domains, and the links represent EET rate constants connecting domains. In Fig. 1C, the color of each node represents the average site energies of Chls within each domain, revealing that the domains in CP29 and CP26 have the maximum (blue) and minimum (red) site energies, respectively. The EET links show that CP43 is tightly coupled to CP26 and S-LHCII, whereas CP47 is weakly coupled to peripheral LHCIIs. In this manner, the EET network can show how the PSII core is energetically integrated with each LHCII component of the peripheral antennae.

Excitation probability of each domain and its charge separation yield was estimated as an EET network, incorporating experimentally determined rate constants for the charge separation and intrinsic rate constants for the dissipation of electronically excited Chls through nonradiative and radiative pathways (Fig. 1D). We numerically simulated the dynamic behavior of EET as a Markov process, wherein the EET process is only influenced by the current states of the Chls or their domains (and not by past events) (34). By assuming that Chls in all domains are randomly excited at time zero, the excitation probability of each domain, charge separation, and intrinsic dissipation were calculated, which revealed the detailed dynamics of energy conversion from absorbed light energy to charge separation in a PSII SC (Fig. 1E and fig. S2). The distribution map of the excitation probability shows localization of excitation energy in CP26 at ~100 ps and that the decay lifetime of Chl excitation was estimated as 500 ps, comparable to experimentally determined values (490 ps for intact spinach PSII SC at pH 5.5) (35). The charge separation yield was determined to be 0.81, which is consistent with the range (0.78 to 0.84) of the maximum quantum yield experimentally determined in C3 plants (36). This consistency of the quantum yield between experiments and our simulation supports our approach as effective in determining the holistic EET dynamics within the entire PSII SC.

Synthetic EET networks of hypothetical PSII SC models

To understand the advantages of the mixed Chl system of the natural PSII SC, we examined hypothetical PSII SC models consisting of various Chl a and Chl b combinations in LHCIIs (Fig. 2 and fig. S3). These models include all-a– or all-b–type LHCII that solely binds Chl a or Chl b, respectively. The position and orientation of Chls are the same as those of natural Chls. Furthermore, Chl a has a larger magnitude of transition dipole moment than Chl b (table S1). Due to stronger excitonic coupling between Chls a than Chls b, a domain in an all-a–type LHCII has more Chls and has lower site energy than a domain in all-b–type LHCII (Fig. 2, A and C, and tables S2 to S4).

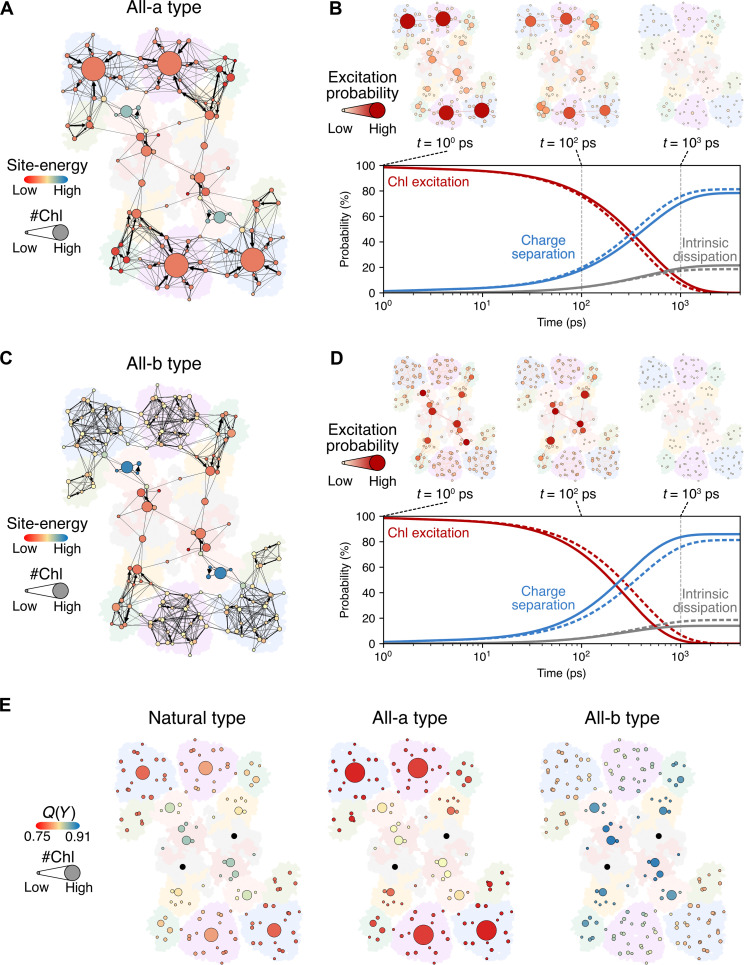

Fig. 2. EET network analysis of all-a– and all-b–type PSII SCs.

(A and C) The EET network and site energies of Chl domains in the all-a– and all-b–type PSII SCs, respectively. The size and color of the circle represent the number of Chls in the domain and its averaged site energy. The direction and line width of the arrows between circles represent the direction and relative rate constants for EET. The rate constants larger than 0.005 ps−1 (time constant of 200 ps) are shown to visualize dominant EET (fig. S1). (B and D) Simulated ensemble probabilities of the excited states of Chls, charge separation, and intrinsic dissipation after initial excitation of a Chl in the all-a– and all-b–type PSII SCs, respectively. Solid lines represent the simulation results of either all-a– or all-b–type PSII SCs, and dashed lines represent the results of the natural PSII SC. (E) Individual yield, Q(Y), of domains in the natural-, all-a–, and all-b–type PSII SCs. Q(Y) of the domain represents the yield of charge separation when the domain is excited. Q(Y) of RC domains was not included in the scale map of Q(Y).

From the network analysis on the EET between the domains of the synthetic models, we also found that the decay of the excitation probabilities is slower in the PSII SC with all-a–type LHCII (all-a–type PSII SC) and faster in the PSII SC with all-b–type LHCII (all-b–type PSII SC) than in the natural PSII SC (Fig. 2, B and D). Specifically, in the all-a–type PSII SC, the excitation probabilities in the peripheral antennae, including S-LHCII, M-LHCII, and CP26, remained higher than those in the other types even at 1 ns (Fig. 2B and figs. S4 and S5). In all-b–type PSII SC, however, the excitation probabilities in the inner antennae, including CP43 and CP47, were higher than those in the other area (Fig. 2D and figs. S4 and S6), leading to the highest charge separation yield among the comparative PSII SC models. These results indicate that the yield of charge separation at RCs is increased in all-b–type PSII SC by the effect of the increased number of Chl b on the energy gap between LHCIIs and the PSII core, which suppresses the energy backflow from the PSII core to LHCIIs.

To further characterize the integrity of antennae, we estimated the probability of charge separation at the RC when each domain is excited individually, which we call individual yield, Q(Y) (Fig. 2E). Each colored circle corresponds to a domain with its color representing Q(Y). We found that Q(Y)’s were higher in the PSII core than in the peripheral LHCIIs for all types of PSII SCs. This is due to the structure of the PSII SC in which the peripheral LHCIIs surround the PSII core. It makes the EET directed toward the RC, generating the gradient of Q(Y) from the peripheral LHCIIs to the PSII core. Compared to the natural-type PSII SC, the domains in the PSII core in the all-a–type PSII SC featured lower Q(Y)’s, and those in the all-b–type PSII SC showed higher Q(Y)’s. Note that all types of PSII SCs have an identical PSII core having only Chl a. Therefore, we emphasize that this occurs because of the large energy gap between LHCIIs and the PSII core, which more obstructs the energy backflow from the PSII core to LHCIIs in the all-b–type PSII SC than the all-a type. In other words, “the funneling effect” of EET is the most prominent effect in the all-b–type PSII SC, which aligns well with previously reported characteristics of EET in the FMO complex such as the advantage of “a ratchet system” (37). Therefore, after excitation energy is captured by the PSII SC, it can be efficiently used for charge separation at RCs.

Cumulative excitation energy flow analysis of EET

To trace excitation energy flow in PSII SCs, we propose two key metrics: cumulative input (CI) for each node and net cumulative flow (NCF) on each link. The CI represents the total accumulated energy input to node j, , during the simulation, where fij is the accumulated energy flow from node i to j. Concurrently, the NCF between nodes i and j is defined by , illustrating the net energy transfer dynamics between them. On the basis of the CI and the NCF values, we can reveal the energy transfer pathways in the PSII SC. For example, a node with a high CI value will serve as a gateway, where excitation energy frequently passes through, and the link with a high NCF value will be the major path of the energy traversal. The energy flow map in Fig. 3A shows the characteristic energy pathway of the natural-type PSII (thick and dark arrows in Fig. 3A). The RCs mainly receive excitation energy from the two distinct in-flows through the domains in CP43 or CP47. In the peripheral area, where S-LHCII, M-LHCII, CP24, and CP26 reside, certain domains (red and large nodes) facilitate the building of particular pathways that contribute to frequent EET. These EET paths occur as a consequence of the site-energy landscape in the PSII SC related to the spatial position of low site-energy Chls. In the all-a–type PSII SC, for instance, only a few domains feature high CI, and the EET pathways (distinguished by the dark and thick arrows) are denser in the peripheral region than in the natural region (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the energy flow to RCs can be interrupted and trapped in the peripheral area, resulting in a lower charge separation yield than that of the natural type. In the all-b–type PSII SC, conversely, high-CI domains are positioned along the major EET pathways so that the energy flow can be effectively guided to RCs, which enables the highest yield of charge separation (Fig. 3C). Note that the high-CI domains have low site energy in PSII SC.

Fig. 3. Cumulative flow analysis of PSII SCs.

(A to C) Relative CI of each domain and NCF of each link in the natural-, all-a–, and all-b–type PSII SCs, respectively. The Chls in the high CI domains are shown in the red boxes for each domain.

Light-harvesting and photoprotective capabilities of PSII SCs

The increased amount of Chl b can improve the charge separation yield of the PSII SC beyond the increased absorption in several spectral areas of Chl b. Considering the solar radiation spectrum that both Chls a and b can absorb, having more Chl b in an LHCII can naturally achieve higher light-harvesting efficiency (fig. S7). However, we found in the PSII SC models that the yield is even higher (Fig. 4A, green circles) than the expected natural yield advantage (Fig. 4A, gray dashed line). This indicates that the funneling effect described above enables the PSII SC to outperform the inherent advantage of having more Chl b in the antennae.

Fig. 4. Light-harvesting and photoprotective capabilities of PSII SCs.

(A) The relationship between the proportion of Chl b in the antenna of the PSII SCs compared with the relative absorption of solar radiation (gray dashed line) and the consequent relative net light-harvesting efficiency (green circles and line). (B) Non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) candidate domains (red circles) and RCs (green circles) and the major pathway of energy flow in the natural-type PSII SC. Major pathways selectively represent the top 1% NCF (fig. S8). (C) Simulated NPQ values [(yield without NPQ)/(yield with NPQ) − 1] of the natural-type PSII SC with various combinations of the rate constants of NPQ in trimeric LHCII and CP29 (table S5). (D) Simulated NPQ values of the natural-, all-a–, and all-b–type PSII SCs with the rate constants of NPQ in trimeric LHCII (tables S5 to S7).

In general, the higher the yield of a PSII SC is, the larger the amount of light energy a plant can harvest. However, it is always beneficial only for plants under moderate light conditions. In nature, plants are often exposed to excessive light conditions that could cause photodamage to the photosystems (38). Thus, any photoprotection schemes are crucial for plants to avoid such photodamage for their survival under changing light conditions.

Our results also support that the natural PSII SC has great potential to prevent photodamage by non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) in trimeric LHCIIs or CP29s. In the natural PSII SC, we found that excitation energy mostly flows through specific domains along the major pathways in the LHCIIs (Fig. 4B). Intriguingly, these stepping domains include Chls a611-a612 and a603-a609, which have been proposed as photoprotective quenching sites in LHCIIs. Chls a611-a612, observed in S-LHCII and M-LHCII, have been proposed to quench the excitation energy by transferring the energy to lutein (11, 39) or by charge transfer quenching (14). Chls a603-a609, observed in CP29, have been proposed to conduct a similar role by charge transfer quenching with zeaxanthin (13). Therefore, these stepping domains in the natural PSII SC can dissipate excessive energy, when necessary, as if firefighters were near fire. To address this hypothesis, we estimated the yield of PSII SC when NPQ process is activated and calculated the NPQ values by applying the various rate constants [0.005 to 0.04 ps−1 for trimeric LHCII (11, 14, 15, 40, 41) and 0.005 to 0.2 ps−1 for CP29 (13, 42–44)] of NPQ in trimeric LHCIIs or CP29s (Fig. 4, C and D, and tables S5 to S7). The result showed that NPQ in trimeric LHCII much more efficiently quenches the excitation energy than that in CP29 (Fig. 4C). In the comparison of the PSII SCs, the simulated NPQ in natural and all-a–type PSII SCs showed about twice higher values than that of all-b–type PSII SC (Fig. 4D). This result supports that the natural-type PSII SC forms an efficient structure to dissipate the excitation energy while maintaining high light-harvesting efficiency.

Enhancing light-harvesting efficiency through the ratchet system

Our results also provide the insight that the “ratchet” system is advantageous over a monotonous funnel system for light-harvesting efficiency. To consider the ratchet effect on EET, we investigated other models of PSII SC with various ratios of Chl b to Chls: trimerLHCII-a, trimerLHCII-b, monomerLHCII-a, and monomerLHCII-b. The trimerLHCII-a or monomerLHCII-a types involve the hypothetical trimeric or monomeric LHCIIs that bind only Chl a, respectively. Likewise, the trimerLHCII-b and monomerLHCII-b types are defined in the same way, binding only Chl b. Notably, the trimerLHCII-a type showed higher quantum yields than the monomerLHCII-a type, as well as the monomerLHCII-b type to the trimerLHCII-b type (Fig. 4A). We hypothesize that these features originated from the different excited energy levels of the Chls in trimeric LHCIIs and monomeric LHCIIs. In the trimerLHCII-a type and the monomerLHCII-b type, the overall excited energy levels of Chls in the monomeric LHCIIs are higher than those of the trimeric LHCIIs, which can cause the ratchet effect because the excitation energy in the core complexes can rarely migrate to the trimeric LHCIIs in this condition, and vice versa in the monomerLHCII-a type and the trimerLHCII-b type (fig. S3). This finding is in line with a previous study showing that the FMO complex forms the ratchet system rather than the monotonous funnel system (37). This insight supports that the utilization of the ratchet system can be a potential strategy to increase light-harvesting efficiency in light-energy conversion systems such as photovoltaic materials, including solar cells.

Our EET analysis of the PSII SC stands out from previous studies by offering a holistic approach to understanding the entire system of PSII SC. By incorporating network analysis, we provide a comprehensive view of the EET process, focusing on the interplay between antenna complexes and core complexes within the EET network. Our analysis successfully simulated the “light-harvesting” and “photoprotection” capabilities of the PSII SC, highlighting the advantages of the coexistence of Chls a and b in natural LHCII, particularly when compared to hypothetical PSII SCs. Only the natural PSII SC efficiently transfers excitation energy to the RC while simultaneously protecting itself.

The EET network analysis can be further extended to investigate various characteristics of EET in photosynthetic protein complexes. This approach represents a step toward understanding the photosystem from a network perspective, with focus primarily on the topological characteristics and EET dynamics of the PSII SC. Further research can explore other network science approaches to this problem, including consideration of community characteristics and resilience analysis, which hold great promise for further comprehending natural systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Domain formation

In large photosynthetic antenna systems, all embedded pigments are not necessarily strongly coupled. This coupling results in the formation of discrete domains, each of which comprises delocalized exciton states of strongly coupled pigments. To define these domains quantitatively, the threshold value is introduced. Pigment pairs whose electronic coupling is greater than the threshold are assigned to the same domain. The Redfield theory is often used to describe exciton relaxation within the domains, whereas the generalized Förster theory (29, 32, 33) is a suitable choice to describe energy transfer between different domains. The electronic excitation localized on the mth pigment and the Mth delocalized exciton state in the d-domain are denoted by and , respectively. The corresponding electronic transition energies are written as and . For convenience, is introduced for any possible paris . Delocalized exciton states can be expressed by a linear combination of localized electronic excitations as . It is noted that the subscription will be omitted when domains are not necessarily specified. The threshold value is usually chosen to be in the order of the environmental reorganization energy to consider environment-induced dynamic localization effects. A typical value for the reorganization energy associated with electronic excitations in pigment-protein complexes is in the range (37) of , and, therefore, we assume the threshold value to be 30 . We note that both Redfield and generalized Förster theories are computationally less expensive but quantitatively less accurate than more sophisticated theories (31). However, both the theories provide qualitatively reasonable results in the parameter region corresponding to natural photosynthetic systems, as was demonstrated by Ishizaki and Fleming (31). Therefore, we think it is relevant to use the Redfield theory and the generalized Förster theory to investigate energy transfer dynamics in such a large system as the PSII SC. For the same reason, we will use the point-dipole approximation to evaluate the excitonic couplings of pigment instead of more sophisticated theories (45, 46).

The values of electronic excitation energies and excitonic couplings of pigments in the PSII core, LHCII, CP26, and CP29 are taken from (6, 47–49). Because the parameters for CP24 have not been reported, they are substituted by those for the LHCII monomer in a similar fashion as in (17). The interprotein excitonic couplings are calculated with the use of the point-dipole approximation with the effective magnitudes of transition dipole moments (50)

| (1) |

where is the vacuum permittivity and is the center-to-center spatial vector between pigments m and n. The vector stands for the transition dipole moment of the band in Chl. The direction is assumed to be along the NB-ND axis (29), and the effective magnitudes are used to include the influence of the surrounding protein environment (50). The cryo-electron microscopy data, PDB: 5XNL, are used to evaluate the orientations of the transition dipole moments and distance vectors. The used values are presented in table S1.

To describe the influence of the protein environment upon the involved electronic excitations, we consider the spectral density. Substantial experimental and computational efforts have been made to obtain spectral density functions for various photosynthetic pigment-protein complexes, which provides the information on protein-induced fluctuations and intramolecular vibrational modes affecting the electronic states of embedded pigments. For computationally reproducing absorption and emission spectra of molecules, both the effects are necessary. As was demonstrated by Fujihashi et al. (51), however, the impact of the intramolecular vibrational modes on the energy transfer dynamics is typically eradicated by the protein-induced fluctuations at physiological temperatures. For this reason, we use the spectral density with no vibrational sideband (52)

| (2) |

with S = 0.65, s1 = 0.8, s2 = 0.5, ω1 = 0.5565 cm−1, and ω2 = 1.936 cm−1. The reorganization energy associated with electronic excitations is thus obtained with the well-known formula, , yielding the values of Eλ = 50.87 cm−1.

Intradomain exciton transfer

Among the pigments in a domain, we assume that the relaxation of one delocalized exciton state to another is described with the Redfield theory. Hence, the rate constant of exciton transfer is obtained as (29)

| (3) |

where is the Bose-Einstein distribution function. The factor is computed with the exciton coefficients {} as

| (4) |

where is the center-to-center distance between pigments and , and is the correlation radius of the protein-induced fluctuations. We set Rc = 5.0 Å for numerical calculations (52). The inverse lifetime of state is, thus, obtained as , yielding the lifetime broadening in optical spectra. See Eqs. 7 and 8.

Interdomain exciton transfer

Energy transfer between delocalized exciton states each of which belongs to different domains is described as Förster-type transfer. The rate constant of the transfer from to is, thus, computed as

| (5) |

In the equation, represents excitonic coupling between delocalized exciton states

| (6) |

and and are the fluorescence and absorbance line-shape functions

| (7) |

| (8) |

respectively. In the line-shape functions, the function is given by

| (9) |

and is the frequency renormalized with the diagonal and off-diagonal contributions of the exciton-vibrational coupling

| (10) |

We assume that intradomain exciton relaxation processes are sufficiently fast in comparison to interdomain exciton transfer; thus, the rate of interdomain exciton transfer from domain a to b is calculated as in (30)

| (11) |

where is the thermal distribution of an exciton state when only domain a is considered. The parameter is the Boltzmann constant. An average over the static disorder in site energies needs to be taken to calculate the interdomain transfer rate constant in Eq. 11 (47). We assume that the independent variation of the site energies obeys a Gaussian distribution with full width at half maximum, for all pigments, and we perform Monte Carlo sampling. The used values for are given in tables S8 and S9. The simulated absorption spectrum was compared with experimentally obtained data (fig. S9). The results showed that the peak positions and widths of the simulated spectrum were in good agreement with the experiment data, demonstrating the validity of the theoretical model and parameters used. The discrepancy in the shorter wavelength region below 640 nm is due to the exclusion of the and Soret bands and intermolecular vibrational sidebands from the simulations.

Linear absorption spectrum

The linear absorption spectrum is obtained as a sum of the spectrum in each domain as (30)

| (12) |

| (13) |

where is the transition dipole moment of the exciton state expressed as and the bracket stands for the average over the static disorder in the site energies.

Site energies and excitonic couplings in hypothetical PSII SC models

If the Chl in the light-harvesting systems is replaced with another type of Chl, then the structural and physical properties of the Chl, such as the positions, orientations, site energies, and excitonic couplings, are expected to change. When the EET dynamics in PSII SC models with varied ratios of Chl b to Chl a are investigated, the values of the site energies and excitonic couplings should be essentially evaluated on the basis of quantum chemical calculations. However, the aim of this study was to explore the general characteristics of the EET dynamics affected by Chl substitution rather than the details. Then, we assume that the positions and orientations of the Chls are fixed, and we determine the values of the site energies and excitonic couplings in these hypothetical PSII SC models with the approximations described below.

The site energy of Chl is determined on the basis of its transition energy under the influence of environmental degrees of freedom. In the PSII SC, because each Chl is affected by these different environments, the shift of the transition energy from the vacuum is different in each Chl, even if the types of Chls are the same. Thus, when the Chl in the PSII SC is substituted into the other type, the magnitude of the change in the site energy is expected to be different at each site. However, we assume that this magnitude, , is the same throughout the PSII SC and is estimated as the difference in the transition energy between Chl a and Chl b in solvent. We, therefore, choose the excitation energies in diethyl ether obtained as 662 nm for Chl a and 644 nm for Chl b, respectively, which leads to ΔE = 422 cm−1. In the all-a, monomerLHCII-a, and trimerLHCII-a types, we subtract ΔE from the site energies of Chl b, whereas we add ΔE to the site energies of Chl a in the all-b, monomerLHCII-b, and trimerLHCII-b types.

When the distance between the Chls is short compared to the spatial extent of their wave functions, the point-dipole approximation can be used to compute the values of the excitonic couplings between them. Within the point-dipole approximation, if the transition dipole moment of the mth Chl in the natural PSII SC, is replaced with , then the modified excitonic coupling between the mth and nth Chls is expressed as

| (14) |

We assume that Eq. 14 is valid for all pairs of the Chls in the hypothetical models of the PSII SC. Generally, this approximation is not satisfied, and the evaluation of the excitonic couplings requires a more accurate method of quantum chemical calculation (53, 54). However, for the excitonic couplings involving only the transitions of Chls in LHCII, it has been reported that the point-dipole approximation is sufficiently accurate to compute the values of these couplings (55). We assume that this fact is applicable to monomeric light-harvesting complexes, and we use Eq. 14 to obtain the values of the excitonic couplings in the hypothetical models. The distributions of rate constants in natural-type, all-a–type, and all-b–type PSII SCs are shown in fig. S1.

EET simulation

The consecutive EET is initiated at one of the domains and terminated when the excitation energy is used for charge separation at special pairs in RCs (photosynthesis) or is intrinsically dissipated. We denote the set of transient states of the 134 total domains as and two absorbing states representing the charge separation and dissipation as . Representing the possible states S at each transition, the number of states . Note that this is the case of natural type. See the Supplementary Materials for the total number of states of all-a and all-b types. In this study, the timescale over which the memory effect persists in energy transfer is negligibly short in comparison to the timescale of the numerical simulation. Therefore, the energy transfer process to a state depends only on the current state, not on previous history. It means that the energy transition process in the photosystem can be considered as a stochastic process that satisfies the Markov property (56, 57). Therefore, we generate the transition rate matrix , which is also known as generator matrix, from the excited energy transition as a Markov process (34). Assuming the system starts in state , for the first-order reaction of the excited energy transfer during photosynthesis, the transition proceeds to the next state at . We approximate the transition rate from the EET rate such that . Similarly, the rate constant of charge separation in RCs is set as (time constant of 1.5 ps) (58, 59), where i is a particular domain in RCs and j = 135, while the dissipation is set identically for all domains (time constant of 2 ns) (60–62), where and j = 136. In addition, the system can incorporate the process of NPQ. This process is characterized by the conversion of energy to thermal energy in specific domains, as illustrated in Fig. 4B, which identifies the domains belonging to trimeric LHCII and CP29. Therefore, in these domains, the usual dissipation rate for all nodes is supplemented with the additional dissipation rate due to NPQ. We simulated the system’s yield with different NPQ rates assigned to the domains in LHCII and CP29, respectively, varying these rates to observe the consequences. The results are described in Fig. 4 (C and D).

A simulation was also performed with the rate constants (charge separation, 0.5 to 3 ps−1; intrinsic dissipation, 1 to 4 ns−1) and showed that the experimentally obtained values resulted in a consistent yield of charge separation (0.81), which is close to the experimentally obtained yield (fig. S10). Note that the transient states (i ∈ T) represent the distinct domains in PSII that consist of physically existing Chls, whereas the two additional absorbing states () are conceptual. The diagonal elements considering that no self-transition occurs. We then convert the transition rate matrix of PSII to the embedded discrete-time Markov chain, . While l is typically defined as the smallest diagonal element of Q (63), we set l = −5 uniformly across all networks to ensure consistent simulation conditions across diverse network structures. This approach is valid because the minimum diagonal element of Q is greater than −5 for all networks. The elements of P, , indicate the probability of transferring the excitation energy between states. We consider the excited energy transition between S states such that for all i.

Upon giving the initial conditions of the states, we numerically track the transition process of the excited energy by multiplying P. Let the vector be the state vector indicating the excitation probability of each state i at Markov time (or step) t. Because the vector represents the probability distribution, at all Markov times t, it satisfies . We let a domain i be initially excited by defining the ith element and , otherwise in the initial state vector . The excited energy can move to the next state following the transition probability , where denotes the ith standard basis vector, which has a value of 1 in the ith position and 0 elsewhere. Using this formulation, the next states are computed iteratively as: . We set the time interval of the Markov process to 0.2 ps to balancing the need for sufficient resolution to capture the interdomain EET dynamics with the need for neglecting the memory effects due to protein-induced fluctuations and the thermal equilibration inside individual domains. This time step is larger than the timescale of the memory effects, which are faster than 0.1 ps (9, 31), but provides sufficient resolution to capture essential features of the system as shown in the simulated EET dynamics within the natural PSII SC (fig. S2), because the largest net outgoing EET rate constant between all domains is 3 to 4 ps−1, corresponding to a timescale of 0.25 to 0.33 ps. In this sense, we recursively estimate the probability distribution at any tth step. Note that depends on the initial distribution of . We assume that only a domain is initially excited, and no additional multiple excitations occur during the Markov process. To estimate the average probability distribution over the initial target domains, we take the ensemble average over i, such that , where is the initial excitation probability of domain i. In this study, we assume that the excitation probability of domain i is proportional to the number of Chls, which is denoted by . Therefore, we estimate the average probability distribution for PSII as , where with for or 0 for , and

Network analysis of various PSII network models

We convert the natural PSII SC into a network structure, which we refer to as the natural PSII network, with nodes representing the domains in PSII and links for the energy transfer rate between the pairs of them. The spatial coordinates of domains remain in the PSII network, and the directed link weight from node i to j is identical to in P. Therefore, the PSII network is a directed and weighted fully connected spatial network for the total number of nodes and the total number of links. The PSII network is, in principle, a fully connected network between all pairs of domains, because the EET rates between domains are all positive values. However, considering the fact that the EET rate decays rapidly as the distance between domains increases, we filter out the links with negligible low weight remaining a backbone of the network for visualization. In this study, we estimate the energy transfer dynamics on the basis of the fully connected relationship while we show the network with only some part of all links for visual clarity.

In the PSII network, where the excited energy transfers between domains are probabilistically proportional to the EET rate, total cumulative flow analysis can reveal the apparent pattern of energy delivery from each node to the RC. To formally define the cumulative energy flow, we start by specifying the directed edge from to as where represents the simulation time, which, in our study, is set to 105. The NCF of link (i, j) is then defined as the absolute difference between and and follows the direction of the larger energy flow. Furthermore, we define the CI of node i as which corresponds to the total incident energy of the node. These formal definitions enable the accurate characterization of excited energy transfer within the PSII network.

For the comparative analysis, we constructed various types of PSII network models in addition to the natural PSII network. By alternating Chl b to Chl a (Chl a to Chl b) in an LHCII of the natural PSII network, we generate an all-a–type (all-b–type) PSII network that has only a single type of Chl in LHCII. We also constructed the intermediate versions of PSII networks between those models by partially modifying Chls. Specifically, we change the Chls only for those that are in monomeric or trimeric components in LHCII. By this, we prepared seven distinct PSII networks varying the composition of the Chl types (fig. S3).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI, grants 23K14216 (E.K.), 23H04960 (E.K. and J.M.), 21H01052 (S.S. and A.I.), and 21H05040 (J.M.); National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT), NRF-2022R1C1C1005856 (D.L. and H.K.); Human Frontier Science Program, award no. RGY0076 (A.I.); and MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Program, grant no. JPMXS0120330644 (A.I.).

Author contributions: Writing—original draft: E.K., D.L., S.S., J.-Y.J., A.I., J.M., and H.K. Conceptualization: E.K., D.L., M.V., A.I., J.M., and H.K. Investigation: E.K., D.L., S.S., J.-Y.J., M.V., A.I., and H.K. Writing—review and editing: E.K., D.L., S.S., M.V., A.I., J.M., and H.K. Methodology: E.K., D.L., S.S., J.-Y.J., A.I., and H.K. Resources: E.K., A.I., J.M., and H.K. Funding acquisition: E.K., A.I., J.M., and H.K. Data curation: E.K., S.S., J.-Y.J., M.V., and H.K. Validation: E.K., D.L., A.I., J.M., and H.K. Supervision: A.I., J.M., and H.K. Formal analysis: E.K., D.L., S.S., J.-Y.J., M.V., A.I., and H.K. Software: E.K., D.L., S.S., J.-Y.J., M.V., and H.K. Project administration: E.K, J.M., and H.K. Visualization: E.K., D.L., and H.K.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S10

Tables S1, S5 to S9

Legends for tables S2 to S4

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Tables S2 to S4

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.R. E. Blankenship. Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis (Wiley/Blackwell, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müller P., Li X. P., Niyogi K. K., Non-photochemical quenching. A Response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol. 125, 1558–1566 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dekker J. P., Boekema E. J., Supramolecular organization of thylakoid membrane proteins in green plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1706, 12–39 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Z., Yan H., Wang K., Kuang T., Zhang J., Gui L., An X., Chang W., Crystal structure of spinach major light-harvesting complex at 2.72 Å resolution. Nature 428, 287–292 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novoderezhkin V. I., Palacios M. A., van Amerongen H., van Grondelle R., Excitation dynamics in the LHCII complex of higher plants: Modeling based on the 2.72 Å crystal structure. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 10493–10504 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müh F., Madjet M. E.-A., Renger T., Structure-based identification of energy sinks in plant light-harvesting complex II. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 13517–13535 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calhoun T. R., Ginsberg N. S., Schlau-Cohen G. S., Cheng Y. C., Ballottari M., Bassi R., Fleming G. R., Quantum coherence enabled determination of the energy landscape in light-harvesting complex II. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 16291–16295 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel G. S., Calhoun T. R., Read E. L., Ahn T. K., Mancal T., Cheng Y. C., Blankenship R. E., Fleming G. R., Evidence for wavelike energy transfer through quantum coherence in photosynthetic systems. Nature 446, 782–786 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishizaki A., Fleming G. R., Quantum coherence in photosynthetic light harvesting. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 3, 333–361 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arp T. B., Kistner-Morris J., Aji V., Cogdell R. J., van Grondelle R., Gabor N. M., Quieting a noisy antenna reproduces photosynthetic light-harvesting spectra. Science 368, 1490–1495 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruban A. V., Berera R., Ilioaia C., van Stokkum I. H., Kennis J. T., Pascal A. A., van Amerongen H., Robert B., Horton P., van Grondelle R., Identification of a mechanism of photoprotective energy dissipation in higher plants. Nature 450, 575–578 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holt N. E., Zigmantas D., Valkunas L., Li X. P., Niyogi K. K., Fleming G. R., Carotenoid cation formation and the regulation of photosynthetic light harvesting. Science 307, 433–436 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn T. K., Avenson T. J., Ballottari M., Cheng Y. C., Niyogi K. K., Bassi R., Fleming G. R., Architecture of a charge-transfer state regulating light harvesting in a plant antenna protein. Science 320, 794–797 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miloslavina Y., Wehner A., Lambrev P. H., Wientjes E., Reus M., Garab G., Croce R., Holzwarth A. R., Far-red fluorescence: A direct spectroscopic marker for LHCII oligomer formation in non-photochemical quenching. FEBS Lett. 582, 3625–3631 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller M. G., Lambrev P., Reus M., Wientjes E., Croce R., Holzwarth A. R., Singlet energy dissipation in the Photosystem II light-harvesting complex does not involve energy transfer to carotenoids. ChemPhysChem 11, 1289–1296 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caffarri S., Broess K., Croce R., van Amerongen H., Excitation energy transfer and trapping in higher plant photosystem II complexes with different antenna sizes. Biophys. J. 4, 2094–2103 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennet D. I. G., Amarnath K., Fleming G. R., A structure-based model of energy transfer reveals the principles of light harvesting in photosystem II supercomplexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9164–9173 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liguori N., Croce R., Marrink S. J., Thallmair S., Molecular dynamics simulations in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 144, 273–295 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thallmair S., Vainikka P. A., Marrink S. J., Lipid fingerprints and cofactor dynamics of light-harvesting complex II in different membranes. Biophys. J. 116, 1446–1455 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheng X., Liu Z., Kim E., Minagawa J., Plant and algal PSII-LHCII supercomplexes: Structure, evolution and energy transfer. Plant Cell Physiol. 62, 1108–1120 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takabayashi A., Kurihara K., Kuwano M., Kasahara Y., Tanaka R., Tanaka A., The oligomeric states of the photosystems and the light-harvesting complexes in the Chl b-less mutant. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 2103–2114 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su X., Ma J., Wei X., Cao P., Zhu D., Chang W., Liu Z., Zhang X., Li M., Structure and assembly mechanism of plant C2S2M2-type PSII-LHCII supercomplex. Science 357, 815–820 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. E. J. Newman, Networks: An Introduction (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 24.B. Albert-László, Network Science (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avena-Koenigsberger A., Misic B., Sporns O., Communication dynamics in complex brain networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 17–33 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y., Nishikawa T., Motter A. E., Small vulnerable sets determine large network cascades in power grids. Science 358, eaan3184 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee E., Karimi F., Wagner C., Jo H.-H., Strohmaier M., Galesic M., Homophily and minority-group size explain perception biases in social networks. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 1078–1087 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J., Zhang Y.-J., Xu C., Li J., Sun J., Xie J., Feng L., Zhou T., Hu Y., Reconstructing the evolution history of networked complex systems. Nat. Commun. 15, 2849 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renger T., Theory of excitation energy transfer: From structure to function. Photosynth. Res. 102, 471–485 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raszewski G., Renger T., Light harvesting in Photosystem II core complexes is limited by the transfer to the trap: Can the core complex turn into a photoprotective mode? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 4431–4446 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishizaki A., Fleming G. R., Unified treatment of quantum coherent and incoherent hopping dynamics in electronic energy transfer: Reduced hierarchy equation approach. J. Chem. Phys. 130, 234111 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sumi H., Theory on rates of excitation-energy transfer between molecular aggregates through distributed transition dipoles with application to the antenna system in bacterial photosynthesis. J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 252–260 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholes G. D., Jordanides X. J., Fleming G. R., Adapting the Förster theory of energy transfer for modeling dynamics in aggregated molecular assemblies. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 1640–1651 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 34.A. T. Bharucha-Reid, Elements of the Theory of Markov Processes and Their Applications (McGraw-Hill, 1960). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim E., Watanabe A., Duffy C. D. P., Ruban A. V., Minagawa J., Multimeric and monomeric photosystem II supercomplexes represent structural adaptations to low- and high-light conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 14537–14545 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Björkman O., Demmig B., Photon yield of O2 evolution and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics at 77 K among vascular plants of diverse origins. Planta 170, 489–504 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishizaki A., Fleming G. R., Theoretical examination of quantum coherence in a photosynthetic system at physiological temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17255–17260 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aro E. M., Virgin I., Andersson B., Photoinhibition of Photosystem II. Inactivation, protein damage and turnover. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1143, 113–134 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pascal A. A., Liu Z., Broess K., van Oort B., van Amerongen H., Wang C., Horton P., Robert B., Chang W., Ruban A., Molecular basis of photoprotection and control of photosynthetic light-harvesting. Nature 436, 134–137 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miloslavina Y., de Bianchi S., Dall’Osto L., Bassi R., Holzwarth A. R., Quenching in Arabidopsis thaliana mutants lacking monomeric antenna proteins of photosystem II. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36830–36840 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chmeliov J., Gelzinis A., Songaila E., Augulis R., Duffy C. D. P., Ruban A. V., Valkunas L., The nature of self-regulation in photosynthetic light-harvesting antenna. Nat. Plants 2, 16045 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng Y. C., Ahn T. K., Avenson T. J., Zigmantas D., Niyogi K. K., Ballottari M., Bassi R., Fleming G. R., Kinetic modeling of charge-transfer quenching in the CP29 minor complex. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 13418–13423 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fox K. F., Ünlü C., Balevičius V. Jr., Ramdour B. N., Kern C., Pan X., Li M., van Amerongen H., Duffy C. D. P., A possible molecular basis for photoprotection in the minor antenna proteins of plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1859, 471–481 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park S., Fischer A. L., Steen C. J., Iwai M., Morris J. M., Walla P. J., Niyogi K. K., Fleming G. R., Chlorophyll-carotenoid excitation energy transfer in high-light-exposed thylakoid membranes investigated by snapshot transient absorption spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11965–11973 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adolphs J., Renger T., How proteins trigger excitation energy transfer in the FMO complex of green sulfur bacteria. Biophys. J. 91, 2778–2797 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adolphs J., Müh F., Madjet M. E.-A., Renger T., Calculation of pigment transition energies in the FMO protein: From simplicity to complexity and back. Photosynth. Res. 95, 197–209 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shibata Y., Nishi S., Kawakami K., Shen J.-R., Renger T., Photosystem II does not possess a simple excitation energy funnel: Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy meets theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 6903–6914 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khokhlov D. V., Bekiv A. S., Eremin V. V., Exciton states and optical properties of the CP26 photosynthetic protein. Comput. Biol. Chem. 72, 105–112 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jurinovich S., Viani L., Prandi I. G., Renger T., Mennucci B., Towards an ab initio description of the optical spectra of light-harvesting antennae: Application to the CP29 complex of photosystem II. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 14405–14416 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.T. Renger, E. Scholdder, “Modeling of Optical Spectra and Light Harvesting in Photosystem I” in Photosystem I: The Light-Driven Plastocyanin:Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase, J. H. Golbeck, Ed. (Springer, 2006), pp. 595–610. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fujihashi Y., Fleming G. R., Ishizaki A., Impact of environmentally induced fluctuations on quantum mechanically mixed electronic and vibrational pigment states in photosynthetic energy transfer and 2D electronic spectra. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 212403 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Renger T., Marcus R. A., Photophysical properties of PS-2 reaction centers and a discrepancy in exciton relaxation times. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 1809–1819 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krueger B. P., Scholes G. D., Jimenez R., Fleming G. R., Electronic excitation transfer from carotenoid to bacteriochlorophyll in the purple bacterium Rhodopseudomonas acidophila. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 2284–2292 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madjet M. E., Abdurahman A., Renger T., Intermolecular Coulomb couplings from ab initio electrostatic potentials: Application to optical transitions of strongly coupled pigments in photosynthetic antennae and reaction centers. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 17268–17281 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frähmcke J. S., Walla P. J., Coulombic couplings between pigments in the major light-harvesting complex LHC II calculated by the transition density cube method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 430, 397–403 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 56.R. Syski, Passage Times for Markov Chains (IOS Press,1992). [Google Scholar]

- 57.S. R. Asmussen, “Markov jump processes” in Applied Probability and Queues. Stochastic Modelling and Applied Probability (Springer, 2003), vol 51, pp. 595–610. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wasielewski M. R., Johnson D. G., Seibert M., Govindjee, Determination of the primary charge separation rate in isolated photosystem II reaction centers with 500-fs time resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 524–528 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holzwarth A. R., Müller M. G., Reus M., Nowaczyk M., Sander J., Rögner M., Kinetics and mechanism of electron transfer in intact photosystem II and in the isolated reaction center: Pheophytin is the primary electron acceptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6895–6900 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moya I., Silvestri M., Vallon O., Cinque G., Bassi R., Time-resolved fluorescence analysis of the photosystem II antenna proteins in detergent micelles and liposomes. Biochemistry 40, 12552–12561 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palacios M. A., de Weerd F. L., Ihalainen J. A., van Grondelle R., van Amerongen H., Superradiance and exciton (de)localization in light-harvesting complex II from green plants? J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 5782–5787 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Oort B., van Hoek A., Ruban A. V., van Amerongen H., Aggregation of light-harvesting complex II leads to formation of efficient excitation energy traps in monomeric and trimeric complexes. FEBS Lett. 581, 3528–3532 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jensen A., Markoff chains as an aid in the study of Markoff processes. Scand. Actuar. J. 1953, 87–91 (1953). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taniguchi M., Lindsey J. S., Absorption and fluorescence spectral database of chlorophylls and analogues. Photochem. Photobiol. 97, 136–165 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S10

Tables S1, S5 to S9

Legends for tables S2 to S4

References

Tables S2 to S4