SUMMARY

Trichomes of aerial plant organs contribute to adaptive responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. In horticultural plants, increasing glandular trichome density is an effective breeding strategy to enhance resistance to herbivores through promoting the capacity to produce specialized metabolites. The regulatory mechanisms controlling multicellular trichome formation are only partially understood. In this study, we reveal that SlGRAS9 and SlMYC1 transcription factors form a regulatory module controlling glandular trichome formation in multiple tissues. Knockout of SlGRAS9 or overexpression of SlMYC1 in tomato leads to an increased number of type VI glandular trichomes and to higher terpenoid accumulation in leaves, petals, sepals, and fruits. Conversely, knockout of SlMYC1 results in reduced type VI glandular trichomes number and terpenoid levels. Promoter‐binding and genetic interaction experiments revealed that SlGRAS9 negatively regulates the transcription of SlMYC1, indicating that the regulation of glandular trichome formation by SlGRAS9 is dependent, at least partly, on SlMYC1. Consistently, both SlGRAS9 knockout and SlMYC1 overexpression result in higher tolerance of tomato plants to spider mites and aphids. In addition to adding some of the missing components to the mechanisms controlling formation of type VI glandular trichome, our findings also uncover new targets for breeding strategies aimed at improving crop protection against pest invasion, thus ensuring crop yield resilience to climate change.

Keywords: trichome formation, tomato, type VI glandular trichome, terpenoid accumulation, spider mites, aphids

Significance Statement

Trichomes contribute to plant adaptive responses to environmental stresses. Our knowledge of the factors that govern the formation of various trichome types and the means by which these structures provide tolerance to environmental stresses remains only partially understood. Our study unveiled the role of SlGRAS9‐SlMYC1 module of transcription factors in regulating glandular trichome formation and enhancing plant tolerance to pests, thereby defining trichomes as new breeding target aimed at improving crop protection against pest invasion.

INTRODUCTION

Climate change tends to expose crops to increasingly severe environmental constraints, hence the major challenge of ensuring the resilience of crop yield to biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant trichomes are specialized epidermal appendages differentiated from epidermal cells that exist on most organs in the aerial parts of plants, including leaves, stems, petals, sepals, and fruits (Li et al., 2002; Pattanaik et al., 2014; Werker, 2000). The morphology of trichomes varies considerably among different species, prompting their classification into several types, including unicellular or multicellular, glandular or nonglandular, and branched or unbranched (Baur et al., 1991; Yang & Ye, 2013). Multicellular trichomes, especially glandular trichomes, can be considered as cellular factories in which various specialized metabolites such as terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids are produced, stored, and secreted (Barba et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2010, 2014; Schilmiller et al., 2008). Volatile terpenoids produced by multicellular trichomes are important components of the volatile aroma of fruits and flowers that are effective in attracting pollinators and frugivorous animals, thereby making these compounds an important element of the seed dispersal process (Aharoni et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2003). In addition, plant trichomes act as physical barriers and chemical reservoirs, thus representing the first line of defense in plant resistance to various biotic and abiotic stresses, including pest predation, pathogen attack, excessive transpiration, ultraviolet radiation, and extreme temperature (Cho et al., 2017; Frerigmann et al., 2012; Mauricio & Rausher, 1997; Paudel et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020).

Because Arabidopsis can only differentiate single‐cell trichomes, most research on glandular trichome development has focused on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), and sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua) (Chalvin et al., 2020). Among these species, tomato is an excellent model for studying the development of glandular trichome, building on high‐quality genome sequence, a routine genetic transformation system, and extensive genetic resources, providing a wide diversity of trichome types (Jeong et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2014; Tissier, 2012). Indeed, there are seven types of trichomes in cultivated tomato, of which types II, III, and V are nonglandular, and I, IV, VI, and VII are multicellular glandular trichomes (Deng et al., 2012). Type VI glandular trichomes have four head cells and represent the most abundant glandular trichomes that produce and secrete terpenoids. By comparison, types I and IV trichomes have single‐cell heads and are involved in the biosynthesis and secretion of acyl sugars (McDowell et al., 2011). In this regard, tomato glandular trichomes are important barriers allowing plants to resist against pathogens and pests (Kennedy, 2003; Leckie et al., 2016).

Several regulatory factors affecting tomato trichome formation have been identified, including Woolly (Wo), a homeodomain‐Leu zipper IV (HD‐ZIP) transcription factor whose function acquisition mutation leads to a significant increase in the density of type I glandular trichomes (Hua, Chang, Wu, et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2011). Wo protein forms a gradient along the axis of trichome, which plays a dose‐dependent role in trichome differentiation (Wu et al., 2024). To regulate the formation of type I glandular trichome, Wo can form heterodimers with the B‐type cyclin protein (SlCycB2) (Gao et al., 2017). Moreover, Hair and its homolog Hair2, which encode C2H2 zinc finger protein, can interact with Wo to co‐regulate the initiation and elongation of type I glandular trichome in tomato (Chun et al., 2021). HD‐ZIP IV transcription factor Lanata (Ln) is a positive regulator of trichome development, which can interact with Wo and Hair, and the protein–protein interaction between Ln and Wo can promote trichome formation by activating the expression of SlCycB2 and SlCycB3 (Xie et al., 2022). Another member of HD‐Zip IV, SlHD8, has also been proven to promote tomato trichome elongation by directly activating the transcription of cell‐wall‐loosening genes (Hua, Chang, Xu, et al., 2021). In addition, many MYB transcription factors, including SlTHM1, SlMYB52, SlMYB75, and GLAND CELL REPRESSOR (GCR) 1 and 2, have been reported to negatively regulate glandular trichome formation (Chang et al., 2024; Gong et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2021). On the other hand, down‐regulation of the basic bHLH transcription factor SlMYC1 resulted in decreased terpenoid production as well as altered type VI glandular trichome density and morphology, indicating that SlMYC1 is a key regulator of type VI glandular trichome formation in tomato (Hua, Chang, Wu, et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2018). SlMYC1 is recruited by Wo to activate the expression of terpene synthase genes, thereby promoting terpene biosynthesis in type VI glandular trichomes (Hua, Chang, Wu, et al., 2021). Despite the identification of these regulatory components controlling tomato trichome formation, our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms underlying the formation of tomato trichomes remains incomplete.

GRAS transcription factors play important roles in plant growth and development, as well as in hormone signaling and stress responses (Frerigmann et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2024). Overexpression of SlSCL3, a scarecrow‐like (SCL) transcription factor, leads to increased glandular trichome size and terpenoid production, whereas the knockout of SlSCL3 leads to decreased terpenoid levels, demonstrating the ability of GRAS transcription factors to regulate tomato trichome development (Yang et al., 2021). Here, we show that SlGRAS9, another member of this transcription factor family, is expressed in tomato trichomes and negatively regulates type VI glandular trichome formation and terpenoid accumulation in tomato leaf, petal, sepal, and fruit tissues. We further show that the regulation of type VI glandular trichomes is dependent, at least in part, on SlMYC1, whose transcription is negatively regulated by SlGRAS9. Knockout of SlGRAS9 or overexpression of SlMYC1 both result in a higher density of type VI glandular trichomes in multiple tissues and lead to improved tomato resistance to spider mite and aphid aggressors. Altogether, our findings shed new light on the regulatory factors controlling type VI glandular trichome formation and provide novel and effective targets for improving the resistance of tomato plants to spider mites and aphids.

RESULTS

SlGRAS9 is a potential regulator of glandular trichome formation

Transcriptomic profiling of leaf trichomes and leaf tissues of wild (S. habrochaites cv. LA1777) and cultivated (S. lycopersicum cv. LA4024) tomato accessions highlighted the higher transcript abundance of four GRAS TFs, SlGRAS1, SlGRAS9, SlSCL3, and SlGRAS32 in trichomes compared to leaves (Balcke et al., 2017) (Figure S1a,b). Among these, SlSCL3 has already been reported to be an important regulator of terpenoid metabolism in type VI glandular trichomes (Yang et al., 2021). To further investigate whether other GRAS family members play a role in trichome formation, we assessed the transcript levels of 53 GRAS genes present in the tomato genome by quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR). As expected, the GRAS genes identified as highly expressed in glandular trichomes include the previously described glandular trichome development regulator SlSCL3 (Yang et al., 2021). Moreover, we revealed that SlGRAS1, SlGRAS9, and SlGRAS32 display high expression in type VI glandular trichomes isolated from leaf tissues (Figure 1a). Among these, SlGRAS9 showed high transcript level in all trichome‐rich tissues examined with the highest accumulation in sepals (Figure S2a–c). Notably, trichomes account for most of the expression of SlGRAS9 in stem and fruit tissues, as shown by the higher transcript levels in trichomes than in total stem and fruit (Figure S2d,e). Tomato accessions can be categorized into two main types based on their trichome density: (i) the trichome‐rich accessions that are characterized by high density of trichomes regardless of their type (including types I, II, III, IV, V, VI, and VII) and (ii) the trichome‐poor accessions that exhibit a small number of trichomes (Figure S3a,b). To explore the potential role of SlGRAS9 in trichome formation, we first evaluated the expression of SlGRAS9 at the transcript level in eight tomato accessions with contrasting trichome density, including four trichome‐poor and four trichome‐rich tomato lines (Figure 1b). Interestingly, the SlGRAS9 transcript level is tightly correlated with trichome density across different tomato accessions, with the highest level found in trichome‐poor tomato accessions and the lowest level in the trichome‐rich accessions (Figure 1b,c). Altogether, these data suggest that SlGRAS9 plays a potential role in trichome formation.

Figure 1.

SlGRAS9 was highly expressed in trichomes.

(a) Heatmap representation of the expression patterns of 53 GRAS genes in leaves, total trichomes, and glandular trichomes. The expression levels of 53 GRAS genes were detected by RT‐qPCR.

(b) Observation of leaf surface of different tomato cultivars by scanning electron microscope (SEM). According to the trichome density, these tomato cultivars can be divided into two types: trichome‐rich and trichome‐poor. Bars, 500 μm.

(c) The expression level of SlGRAS9 in different tomato cultivars was detected by RT‐qPCR. Data are means (±SD) of three biological replicates. The transcript abundance of leaves of LA0025 tomato cultivar was set as 1. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student's t test.

SlGRAS9 is involved in regulating trichome formation and terpenoid accumulation in multiple tissues

The functional significance of SlGRAS9 in trichome formation was addressed through the generation of knockout lines (Slgras9‐CR) using gene editing by CRISPR/Cas9. Scanning electron microscopy observation revealed higher density of trichomes in Slgras9‐CR leaves, sepals, petals, and fruits compared to wild‐type (WT) (Figure 2a). Assessing the different types of trichomes in 1‐month‐old WT plants indicated that type VI glandular trichomes are present in all organs examined while type VII glandular trichomes can be observed only in floral organs. It is worth mentioning that in leaves, sepals, and fruits, types I, II, and III long trichomes have been counted together, while types IV and V trichomes with similar morphology have been considered together. Remarkably, the density of type VI glandular trichomes significantly increased in all examined organs of Slgras9‐CR plants (Figure 2b–e). In addition, the density of long trichomes (types I, II, and III) was slightly lower in fruits and sepals of Slgras9‐CR plants than in WT plants (Figure 2b–e). These data clearly indicate that misexpression of SlGRAS9 changes the type and density of trichomes in multiple tissues, with the greatest effect observed on type VI glandular trichome formation.

Figure 2.

Trichome density in Slgras9‐CR plants.

(a) The trichome density in leaves, sepals, petals, and fruits of WT and Slgras9‐CR plants was observed by scanning electron microscopy. The bars represent 200 μm and 500 μm, respectively.

(b–e) The density analysis of trichomes in leaves (b), sepals (c), petals (d), and fruits (e) of WT and Slgras9‐CR plants. Data are means (±SD) of at least 10 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student's t test. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Volatile terpenes are important plant metabolites and key actors of plant defense responses, with type VI glandular trichomes being the main producers of terpenoids in plants (McDowell et al., 2011). Consistent with the increased density of type VI glandular trichomes in different organs of Slgras9‐CR plants, the levels of volatile terpenes assessed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) displayed significant increases in the knockout lines. In particular, the concentrations of two sesquiterpenes (α‐humulene and β‐caryophyllene) and four monoterpenes (δ‐elemene, α‐pinene, α‐terpinene, and γ‐terpinene) were significantly higher in leaves, petals, and fruits of Slgras9‐CR plants compared to those in WT plants (Figure 3a–d). In sepals, the contents of α‐pinene and γ‐terpinene were markedly enhanced in Slgras9‐CR plants, while α‐humulene and β‐caryophyllene were slightly decreased (Figure 3b). To gain more insight into the role of SlGRAS9 in terpene biosynthesis, we assessed the transcript levels of terpene synthase genes (TPS) by RT‐qPCR in Slgras9‐CR and WT plants in three different trichome‐rich tissues, including young leaves, petals, and mature green fruit (MG) trichomes. Consistent with GC–MS data, RT‐qPCR analysis indicated higher transcript levels of TPS genes in young leaves, petals, and fruit trichomes of Slgras9‐CR plants compared to WT (Figures S4–S6). However, dual‐luciferase assays failed to show any significant regulatory effect of SlGRAS9 on TPS gene promoters (Figure S7). Taken together, these results support a negative role of SlGRAS9 in controlling terpenoid accumulation in multiple tissues.

Figure 3.

Analysis of terpenoid levels in trichome‐rich tissues of Slgras9‐CR plants.

(a–d) The concentration of terpenoids in leaves (a), sepals (b), petals (c), and fruits (d) of WT and Slgras9‐CR plants was determined by GC–MS. Data are means (±SD) of three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student's t test. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

SlGRAS9 negatively regulates transcription of SlMYC1

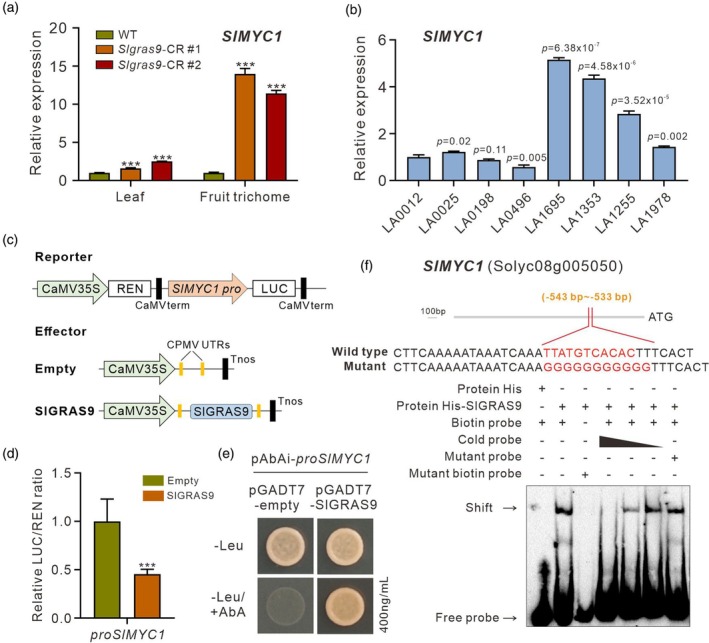

Since the data described above support the hypothesis that SlGRAS9 negatively regulates expression of TPS genes in an indirect way, we sought to uncover the transcription factors mediating the SlGRAS9‐dependent repression of TPS genes. Interestingly, previous DNA affinity purification sequencing (DAP‐seq) experiments revealed that the promoter of SlMYC1, a key regulator of type VI glandular trichome formation, is among the binding targets of SlGRAS9 (Shi et al., 2024). This observation is consistent with the markedly enhanced expression of SlMYC1 in young leaves and fruit trichomes of Slgras9‐CR plants (Figure 4a). Accordingly, the transcript level of SlMYC1 is higher in tomato accessions displaying high trichome density (Figure 4b). In line with the idea that SlGRAS9 is a direct repressor of SlMYC1, the dual‐luciferase assay revealed that SlGRAS9 significantly reduced the luciferase activity driven by the SlMYC1 promoter fragment (Figure 4c,d). Furthermore, both electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and yeast one‐hybrid experiments clearly showed that SlGRAS9 is able to bind with specificity to the SlMYC1 promoter (Figure 4e,f). On the other hand, firefly luciferase complementation imaging assays failed to show interaction between the SlGRAS9 protein and known trichome‐related factors (Figure S8). All these data suggest that SlGRAS9 regulates the expression of TPS genes through the control of SlMYC1 transcription.

Figure 4.

SlMYC1 is directly regulated by SlGRAS9.

(a) The expression level of SlMYC1 in leaves and fruit trichomes of WT and Slgras9‐CR plants. The transcript abundance in young leaves and fruit trichomes of WT plants was set to 1. Data are means (±SD) of three biological replicates.

(b) The expression level of SlMYC1 in different tomato cultivars was detected by RT‐qPCR. Data are means (±SD) of three biological replicates.

(c) Structural schematic diagrams of effector and reporter vectors used in the dual‐luciferase assay. For reporter and effector constructs, the promoter of SlMYC1 was fused into the reporter vector, and the full‐length coding sequence of SlGRAS9 was constructed into the effector vector.

(d) Regulation of the SlMYC1 gene promoter by SlGRAS9 based on the dual‐luciferase assay. The empty effector was regarded as a calibrator (set as 1). Data are means (±SD) of five biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student's t test. The significant differences were indicated by an asterisk (***P < 0.001).

(e) Yeast one‐hybrid assay showing the binding of SlGRAS9 to the SlMYC1 promoter.

(f) SlGRAS9 binding to SlMYC1 promoter region assessed in vitro by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The biotin‐labeled DNA probe incubated with TF‐His protein was used as a negative control, –: absence; +: presence.

Overexpression of SlMYC1 increases trichome density in multiple tissues

Previously, the knockout of SlMYC1 lines showed significant decreases in the density and size of type VI glandular trichomes in leaves (Hua, Chang, Wu, et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2018). To clarify how SlGRAS9 and SlMYC1 co‐regulate trichome formation and to further explore the functional significance of SlMYC1, three independent SlMYC1 overexpressing plants (35S:: SlMYC1) were generated (Figure 5a; Figure S9a,b). Scanning electron microscopy showed that trichome density was substantially higher in SlMYC1‐OE plants than in leaves, sepals, petals, and fruits of WT plants (Figure 5a; Figure S9c). Remarkably, the increased number of type VI glandular trichomes in multiple tissues of SlMYC1‐OE plants resembles the phenotype of Slgras9‐CR plants (Figure 5b–e; Figure S9c). Consistently, the density of type VI glandular trichomes markedly decreased in different tissues of Slmyc1‐CR plants, while the number of types VII and VII‐like (similar to the morphology of VII glandular trichomes) glandular trichomes significantly increased (Figure 5b–e).

Figure 5.

Trichome density in SlMYC1‐OE and Slmyc1‐CR plants.

(a) The trichome density in leaves, sepals, petals, and fruits of WT, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants was observed by scanning electron microscopy. The bars represent 200 and 500 μm, respectively.

(b–e) Trichome density analysis in leaves (b), sepals (c), petals (d), and fruits (e) of WT, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants. Data are means (±SD) of at least 10 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student's t test. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

GC–MS analysis showed a significant increase in terpenoid accumulation in leaves, sepals, petals, and fruits of SlMYC1‐OE plants compared to WT plants (Figure 6a–d). Conversely, terpenoids content in Slmyc1‐CR plants was reduced to almost undetectable levels, in line with the low density of type VI glandular trichomes (Figure 6a–d). While validating the essential role of SlMYC1 in the differentiation of a specific type of trichome, these data also highlight its role in the production of specialized metabolites by type VI glandular trichomes.

Figure 6.

Analysis of terpenoid levels in trichome‐rich tissues of SlMYC1‐OE and Slmyc1‐CR plants.

(a–d) The concentration of terpenoids in leaves (a), sepals (b), petals (c), and fruits (d) of WT, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants was determined by GC–MS. Data are means (±SD) of three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student's t test. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Formation of type VI glandular trichome is mediated by SlGRAS9 and depends at least partly on SlMYC1

To further assess the genetic interactions between SlGRAS9 and SlMYC1, Slgras9‐CR was crossed with Slmyc1‐CR, allowing us to identify homozygous double mutants (Slgras9‐CR × Slmyc1‐CR) that were validated by DNA sequencing. The trichomes number in leaf and fruit tissues of WT, Slgras9‐CR, Slmyc1‐CR, and Slgras9‐CR × Slmyc1‐CR plants were assessed by scanning electron microscopy (Figure 7a). The data revealed that double Slgras9/Slmyc1 mutants display a high number of types VII and VII‐like glandular trichomes and a low number of type VI glandular trichomes, similar to the phenotype observed in single Slmyc1‐CR mutants, suggesting that SlGRAS9 regulates type VI glandular trichome formation through SlMYC1 (Figure 7a–c). These findings again support the role of the SlGRAS9‐SlMYC1 regulatory module in the formation of tomato type VI glandular trichome.

Figure 7.

Analysis of the trichome formation of Slgras9‐CR and Slmyc1‐CR single and double mutants.

(a) The trichome density in leaves and fruits of WT, Slgras9‐CR, Slmyc1‐CR, and Slgras9‐CR × Slmyc1‐CR plants was observed by scanning electron microscope. The red arrow indicates type VI glandular trichomes. The bars represent 200 and 500 μm, respectively.

(b, c) The density analysis of trichomes in leaves (b) and fruits (c) of WT, Slgras9‐CR, Slmyc1‐CR, and Slgras9‐CR × Slmyc1‐CR plants. Data are means (±SD) of at least 10 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student's t test. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001).

Knockout of SlGRAS9 and overexpression of SlMYC1 both result in enhanced tolerance of tomato plants to spider mites and aphids

The contribution of glandular trichomes and terpenoid production to plant pest resistance is well documented, and terpenoids derived from glandular trichomes have been reported to affect the survival and feeding behavior of spider mites (Tetranychus urticae) and aphids (Myzus persicae Sulz.) (Barba et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2010, 2014; Schilmiller et al., 2008). We therefore challenged the tomato plants impaired in SlGRAS9 and SlMYC1 expression with spider mites and aphids, two pests known to pose a serious threat to horticultural crop production through direct sucking of young tissues and virus transmission. The relative preference of spider mites and the tolerance to aphids were tested on WT, Slgras9‐CR, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants. WT leaves exhibited severe disease phenotypes with yellow patches and wilting symptoms (Figure 8a,b), whereas Slgras9‐CR and SlMYC1‐OE leaves displayed fewer chlorotic lesions after 30 days of feeding (Figure 8a,b). Notably, the most severe damage was observed in Slmyc1‐CR plants impaired in type VI glandular trichome formation (Figure 8b). In addition, the number of spider mite eggs on the leaves was significantly reduced in Slgras9‐CR and SlMYC1‐OE compared to WT, indicating that the weaker colonization ability of spider mites on plants enriched in glandular trichomes (Figure S10). Moreover, the spider mite bioassays indicated that a higher number of mites displayed a preference to move toward WT and Slmyc1‐CR leaves rather than to Slgras9‐CR and SlMYC1‐OE leaves (Figure 8c,d). Tolerance to aphids was also tested on flowers, showing that after 7 days of inoculation, the number of aphids was significantly lower in Slgras9‐CR and SlMYC1‐OE than in WT flowers (Figure 8e–h). Altogether, these data indicate that down‐regulation of SlGRAS9 or up‐regulation of SlMYC1 promotes glandular trichome formation and leads to enhanced tolerance of tomato plants to spider mites and aphids.

Figure 8.

Tolerance of Slgras9‐CR, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants to two‐spotted spider mites and aphids.

(a, b) WT, Slgras9‐CR (a), SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR (b) plants were inoculated with spider mites for 30 days. Twenty‐five adult female mites were transferred to individual leaves of 1‐month‐old WT, Slgras9‐CR, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants.

(c, d) Preference experiments were performed to analyze the preference of spider mites for WT, Slgras9‐CR (c), SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR (d) plants. Ten adult female spider mites were placed in the middle area with WT and transgenic plants' leaflets. After 2 h, the number of mites that moved to different leaflets and those that did not make a choice (non‐choice) was counted. Data are means (±SD) of 10 biological replicates.

(e, g) WT, Slgras9‐CR (e), SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR (g) plants were inoculated with aphids for 7 days. Twenty adult aphids were transferred to the inflorescence internodes of 1‐month‐old WT, Slgras9‐CR, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants. Red arrows point to the aphids.

(f, h) Aphids number of WT, Slgras9‐CR (f), SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR (h) plants was counted 7 days after inoculation. Data are means (±SD) of five biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student's t test. The significant differences were indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

(i) Proposed model shows that SlGRAS9‐SlMYC1 regulatory mode controls the type VI glandular trichome formation. SlGRAS9 can directly bind to and inhibit the expression of SlMYC1, and the SlGRAS9‐SlMYC1 module regulates the number of type VI glandular trichomes in multiple tissues.

DISCUSSION

Unlike Arabidopsis that bears unicellular nonglandular trichomes, tomato has typical multicellular glandular trichomes, but the regulatory mechanisms controlling their formation remain only partially understood. SlMYC1, a basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor, has been reported to control type VI glandular trichome development and the regulation of terpene biosynthesis in tomato (Xu et al., 2018). Our findings describe the role of SlGRAS9, a transcription factor acting upstream of SlMYC1, thus adding a new element to the mechanism controlling the type VI glandular trichome formation (Figure 8i). We provide a body of evidence, including transactivation assay, EMSA, and yeast one‐hybrid experiments, demonstrating that SlGRAS9, the tomato homolog of Arabidopsis SCL8 gene, negatively regulates transcription of SlMYC1. Our study indicates that SlGRAS9 is a repressor of SlMYC1 transcription acting via direct binding to its promoter. However, it is important to mention that protein–protein interaction assays have failed to show the ability of SlGRAS9 to interact with known transcription factors involved in trichome development, including Wo, Hair, and SlCycB2, suggesting that SlGRAS9 operates through a pathway independent of these factors. Altogether, these data suggest that SlGRAS9 regulates glandular trichome formation and expression of TPS genes through the control of SlMYC1 transcription, but independent of other known factors.

Our study revealed the essential contribution of the SlGRAS9/SlMYC1 module of transcription factors to type VI glandular trichome formation in tomato. SlGRAS9 loss‐of‐function in tomato promotes the formation of type VI glandular trichome as well as increases in terpenoids content in leaf, sepal, petal, and fruit tissues. Accordingly, the expression level of SlGRAS9 in trichome‐rich tomato cultivars is significantly lower than that in trichome‐poor tomato cultivars. In addition, the expression of TPS genes is significantly increased in the trichome‐rich tissues of Slgras9‐CR plants, in line with the increase in glandular trichome density and terpenoid accumulation. However, although the transcript abundance of TPS genes is significantly higher in Slgras9‐CR plants, these genes are not direct targets of SlGRAS9 as demonstrated by dual‐luciferase assay experiments. Previous studies reported that down‐regulation of SlMYC1 led to a significant decrease in the expression levels of SlTPS5, SlTPS9, SlTPS12, and SlTPS20 in tomato leaves, indicating that SlMYC1 may positively regulate the expression of TPS genes (Xu et al., 2018). Here, we show that the SlMYC1 transcript is significantly increased in young leaves and fruit trichomes of Slgras9‐CR plants, consistent with the idea that SlGRAS9 transcriptionally suppresses SlMYC1 expression. Interestingly, a previous study proved that SlMYC1 can activate the expression of SlTPS1, SlTPS5, and SlTPS12 genes, but SlMYC1 lacks the ability to directly bind to these TPS gene promoters (Hua, Chang, Wu, et al., 2021). SlMYC1 can form a regulatory module with Wo and is recruited into TPS promoters by Wo to activate the transcription of SlTPS1, SlTPS5, and SlTPS12, indicating that SlMYC1 may regulate the expression of TPS genes in an indirect manner (Hua, Chang, Wu, et al., 2021). A significant increase in TPS genes transcript accumulation was observed in Slgras9‐CR plants, one possible reason being the up‐regulated expression of SlMYC1. Taken together, our findings support that the regulation of TPS gene expression by SlGRAS9 depends at least in part on SlMYC1.

GRAS transcription factors are involved in the regulation of a wide range of processes including hormone signaling, plant growth and development, and stress responses, but so far there are few reports regarding a role in trichome formation (Huang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020; Niu et al., 2017). We show here that the SlGRAS9 transcript is significantly lower in trichome‐rich tomato cultivars than that in trichome‐poor tomato cultivars. On the other hand, SlMYC1 is instrumental to the development of type VI glandular trichome, and knocking out SlMYC1 led to defective type VI glandular trichome development, decreased type VI glandular trichomes number, and terpenoid accumulation in tomato leaves (Xu et al., 2018). Notably, SlMYC1 displays a high level of expression at the transcript level in the leaves of trichome‐rich tomato accessions, in contrast to SlGRAS9, which shows a low level of expression in these cultivars. Furthermore, the number of type VI glandular trichomes and terpenoid accumulation were significantly increased in leaf, petal, sepal, and fruit tissues of SlMYC1‐OE plants, in sharp contrast to the developmental defects of type VI glandular trichomes in Slmyc1‐CR plants. SlGRAS9 and SlMYC1 double mutants showed phenotypes similar to those of SlMYC1 single mutants, indicating that SlMYC1 acts downstream of SlGRAS9. The regulation by SlGRAS9 of trichome development is at least partially dependent on SlMYC1.

Remarkably, the knockout of SlGRAS9 and the overexpression of SlMYC1 both show increased type VI glandular trichome density, higher accumulation of terpenoid compounds in multiple tissues, and also improved resistance to spider mites. In addition, the knockout of SlGRAS9 or the overexpression of SlMYC1 significantly affects the feeding behavior of aphids, as shown by a lower number of aphids in inflorescences of Slgras9‐CR and SlMYC1‐OE plants. The outcome of the study designates SlGRAS9 and SlMYC1 as potential effective targets for breeding strategies aiming to enhance the resistance of plants to herbivorous pests. Altogether, our finding reveals a new regulatory module and provides additional evidence for the correlation between glandular trichome density and terpenoids content. They also provide a means to improve plant resistance to pests through modulating the expression of SlGRAS9 and SlMYC1. In this regard, our present study opens a new avenue for effective strategies aiming to increase the resilience of crop plants to environmental stresses via enhancing trichome density and promoting the differentiation of specific types of glandular trichomes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant materials and growth conditions

Transgenic plants (Slgras9‐CR #1 and Slgras9‐CR #2 lines were used in our previous study) were generated in the Micro‐Tom (Solanum lycopersicum) background via the A. tumefaciens‐mediated infection method as previously described (Shi et al., 2024). Overexpression and knockout lines of SlMYC1 in the Micro‐Tom background were kindly donated by Professor Shuang Wu. The trichome‐rich and trichome‐poor tomato accessions were kindly donated by Professor Ning Li. The wild‐type (WT) and transgenic plants are cultivated in a standard greenhouse under controlled conditions (16 h light, 25°C; 8 h dark, 18°C; 60% relative humidity).

Trichome counts and phenotyping

Trichome counts and phenotyping were carried out based on the method in our previous study (Yuan et al., 2021). The leaves and stems of 1‐month‐old tomato plants, petals, and sepals from 2 days before anthesis and fruits at the mature green stage were used for trichome counting. Different types of trichomes were analyzed and observed by JNOEC JSZ5B stereo microscope (JNOEC, Nanjing, China) and Hitachi TM400 plus scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Leaves with an area of 4.5 mm2, sepals with an area of 1.2 mm2, petals with an area of 1.2 mm2, and fruits with an area of 12 mm2 were used to calculate the number of different types of trichomes. At least eight biological replicates were performed for statistical analysis.

Analysis of volatile metabolites

Fresh young leaves, sepals, and petals were dipped in an appropriate amount of tert‐butyl methyl ether for 5 min and gently shaken to extract trichome exudates. For the detection of volatile metabolites of fruit trichomes, mature green fruits were frozen and shaken in liquid nitrogen in a 50‐ml tube with a vortex mixer to separate trichomes. Trichome exudate was concentrated under nitrogen gas, n‐tetradecane (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as an internal standard, and volatile terpenoids were analyzed via gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GCMS‐TQ8040; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) according to the method of Lewinsohn et al. (2001).

Spider mites and aphids bioassays

Two‐spotted spider mites (Tetranychus urticae) were treated as described by Li et al. (2004). Twenty adult female mites were transferred to 1‐month‐old tomato plants for inoculation experiments. Phenotypes of WT and transgenic plants were analyzed after 30 days of infection. Ten adult female mites were moved onto the leaf discs of WT, Slgras9‐CR, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants for fecundity analysis. Eggs were counted at 24 h intervals for 3 days. Based on the method of Wang et al. (2020), 20 adult aphids were transferred to 1‐month‐old tomato plants for inoculation experiments. Phenotypes of WT and transgenic plants were analyzed after 7 days of infection. The inoculated plants were cultured under controlled conditions (16 h light, 25°C; 8 h dark, 18°C; 60% relative humidity).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real‐time PCR analysis

In order to separate type VI glandular trichomes from leaf tissues, 1‐month‐old WT leaves were placed in 200 ml of 70% ethanol, and 15 g of sterilized glass beads with a diameter of 1 mm were added and shaken for 5 min (Bergau et al., 2016; Hua, Chang, Wu, et al., 2021; Schilmiller et al., 2010). Remove the leaves in 70% ethanol, and filter the mixture on 350 and 100 μm nylon mesh in turn (Bergau et al., 2016; Hua, Chang, Wu, et al., 2021; Schilmiller et al., 2010). Transfer the supernatant to a 50‐ml centrifuge tube and centrifuge at 7200 g for 10 min to obtain type VI glandular trichomes for subsequent RNA extraction.

For RNA extraction, plant tissues were collected and frozen with liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was isolated by RNAprep Pure kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). The total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA according to the manufacturer's instructions of PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Osaka, Japan). TB Green Premix Ex TaqTM II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara, Osaka, Japan) was used for RT‐qPCR. The RT‐qPCR procedure was conducted on the Bio‐Rad CFX96 system (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with the cycling program: 30 sec at 95°C, 39 cycles of 5 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 60°C, and 5 sec at 65°C. The relative fold change of each gene was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method, and SlActin was used as the internal reference gene. All primers are listed in Table S1.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Full length of SlGRAS9 gene coding region was amplified and cloned into the pCold™ TF (Takara, Osaka, Japan) vector, and the recombinant expression vector was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (Weidi, Shanghai, China) to generate His‐fusion proteins. The SlGRAS9‐His protein was induced with 0.1 mm isopropyl‐b‐d‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 24 h at 16°C and purified according to the instructions of a His‐tagged protein purification kit (QIAGEN, Dusseldorf, Germany). Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to biotin‐label the designed probes of target genes. EMSA assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions of Light Shift® Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo). The protein concentration used in EMSA assay was 1.5 mg ml−1. The concentrations of biotin probe, mutant biotin probe, and mutant probe without biotin were 5.6, 4.3, and 5.8 ng μl−1, respectively. The concentrations of competitive probes were 53.5, 5.6, and 2.5 ng μl−1, respectively. All primers used can be found in Table S1.

Dual‐luciferase transient expression assay

The dual‐luciferase transient expression assay was performed as described previously (Liu et al., 2020). The full length of the SlGRAS9 gene coding region was amplified and cloned into the pGreenII 62‐SK vector, and the promoter fragments of target genes were cloned into the pGreenII 0800‐LUC vector. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 (Weidi, Shanghai, China). The bacterial solution containing pGreenII 62‐SK and pGreenII 0800‐LUC plasmids was mixed at the ratio of 9:1, and then injected into 1‐month‐old tobacco leaves. The expression values of LUC and REN were detected by the commercial dual‐luciferase reporter gene assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). At least five independent biological replicates were measured for each combination. All primers are listed in Table S1.

Yeast one‐hybrid assay

Full length of SlGRAS9 gene coding region was amplified and inserted into the pGADT7 vector, and the promoter fragment of SlMYC1 gene was amplified and inserted into the pAbAi vector. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into Y1H Gold yeast strain according to the instructions of Yeastmaker™ Yeast Transformation System 2 (Takara, Osaka, Japan). The transformed yeast cells were incubated on SD/−Ura or SD/−Ura/AbA medium (Aureobasidin A; Clontech, San Francisco, CA, USA). The pGADT7‐SlGRAS9 plasmid was further transformed into the recombinant yeast strain, and the transformed yeast cells were incubated on SD/−Leu or SD/−Leu/AbA medium. The empty pGADT7 plasmid was transformed into the recombinant yeast strain as a negative control. The DNA–protein interaction between SlGRAS9 and the promoter fragment of SlMYC1 gene was tested based on colony growth. All primers are listed in Table S1.

Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay

The firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay was performed based on the description by Chen et al. (2008). Full length of SlGRAS9 coding sequence was cloned into pCAMBIA‐nLUC vector, and full length of Wo, Hair, SlCycb2, and SlMYC1 coding sequences were cloned into pCAMBIA‐cLUC vector. The recombinant plasmids were subsequently transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 and transiently co‐expressed in 1‐month‐old tobacco leaves as previously described (Shi et al., 2021). Three days after transfection, 1 mm luciferin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was applied to the injected tobacco leaves and kept in the dark for at least 6 min. The LUC images were captured by the low‐light cooled CCD imaging apparatus (Alliance, Cambridge, UK). For each combination, at least five independent tobacco leaves were observed. All primers are listed in Table S1.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

BH, ZL, MB, WD, YL, JP, and YS designed the experiments. YS, YW, YP, CD, TZ, DS, WL, YL, and JH performed the experiments. BH, ZL, YL, WD, SW, NL, JL, BD, GA, JP, and YL provided experimental assistance. YS wrote the manuscript. BH, JP, ZL, and MB revised the paper. All authors had read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supporting information

Figure S1. The transcript levels of GRAS genes in cultivated (LA4024) and wild (LA1777) tomato cultivars.

Figure S2. SlGRAS9 was highly expressed in trichome‐rich tissues.

Figure S3. Trichome density in different tomato accessions.

Figure S4The expression levels of tomato TPS genes in leaves of Slgras9‐CR plants.

Figure S5. The expression levels of tomato TPS genes in petals of Slgras9‐CR plants.

Figure S6. The expression levels of tomato TPS genes in fruit trichomes of Slgras9‐CR plants.

Figure S7. The regulatory effect of SlGRAS9 on TPS genes.

Figure S8. Protein–protein interaction between SlGRAS9 and other trichome‐related proteins.

Figure S9. Trichome density in SlMYC1‐OE plants.

Figure S10. Fecundity analysis of two‐spotted spider mites on WT, Slgras9‐CR, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32230092, 32202563, 32372403) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2024IAIS‐ZX005), the New Youth Innovation Talent Project of Chongqing (2024NSCQ‐qncxX0339) and the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTB2023NSCQ‐MSX0529) and the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Support Program of Overseas Students of Chongqing (cx2023106) and Chongqing Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (CQMAITS202302).

Contributor Information

Julien Pirrello, Email: julien.pirrello@toulouse-inp.fr.

Zhengguo Li, Email: zhengguoli@cqu.edu.cn.

Baowen Huang, Email: huangbaowen2022@cqu.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Supporting Information of this article.

REFERENCES

- Aharoni, A. , Giri, A.P. , Deuerlein, S. , Griepink, F. , de Kogel, W.J. , Verstappen, F.W.A. et al. (2003) Terpenoid metabolism in wild‐type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell, 15, 2866–2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcke, G.U. , Bennewitz, S. , Bergau, N. , Athmer, B. , Henning, A. , Majovsky, P. et al. (2017) Multi‐omics of tomato glandular trichomes reveals distinct features of central carbon metabolism supporting high productivity of specialized metabolites. Plant Cell, 29, 960–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barba, P. , Loughner, R. , Wentworth, K. , Nyrop, J.P. , Loeb, G.M. & Reisch, B.I. (2019) A QTL associated with leaf trichome traits has a major influence on the abundance of the predatory mite Typhlodromus pyri in a hybrid grapevine population. Horticulture Research, 6, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baur, R. , Binder, S. & Benz, G. (1991) Nonglandular leaf trichomes as short‐term inducible defense of the grey alder, Alnus incana (L.), against the chrysomelid beetle, Agelastica alni L. Oecologia, 87, 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergau, N. , Navarette Santos, A. , Henning, A. , Balcke, G.U. & Tissier, A. (2016) Autofluorescence as a signal to sort developing glandular trichomes by flow cytometry. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7, 949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalvin, C. , Drevensek, S. , Dron, M. , Bendahmane, A. & Boualem, A. (2020) Genetic control of glandular trichome development. Trends in Plant Science, 25, 477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J. , Wu, S. , You, T. , Wang, J. , Sun, B. , Xu, B. et al. (2024) Spatiotemporal formation of glands in plants is modulated by MYB‐like transcription factors. Nature Communications, 15, 2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F. , Tholl, D. , D'Auria, J.C. , Farooq, A. , Pichersky, E. & Gershenzon, J. (2003) Biosynthesis and emission of terpenoid volatiles from Arabidopsis flowers. Plant Cell, 15, 481–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. , Zou, Y. , Shang, Y. , Lin, H. , Wang, Y. , Cai, R. et al. (2008) Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein‐protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiology, 146, 368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.S. , Kwon, M. , Cho, J.H. , Im, J.S. , Park, Y.E. , Hong, S.Y. et al. (2017) Characterization of trichome morphology and aphid resistance in cultivated and wild species of potato. Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology, 58, 450–457. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, J.I. , Kim, S.M. , Kim, H. , Cho, J.Y. , Kwon, H.W. , Kim, J.I. et al. (2021) SlHair2 regulates the initiation and elongation of type I trichomes on tomato leaves and stems. Plant & Cell Physiology, 62, 1446–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W. , Yang, Y. , Ren, Z. , Audran‐Delalande, C. , Mila, I. , Wang, X. et al. (2012) The tomato SlIAA15 is involved in trichome formation and axillary shoot development. The New Phytologist, 194, 379–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frerigmann, H. , Böttcher, C. , Baatout, D. & Gigolashvili, T. (2012) Glucosinolates are produced in trichomes of Arabidopsis thaliana . Frontiers in Plant Science, 3, 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S. , Gao, Y. , Xiong, C. , Yu, G. , Chang, J. , Yang, Q. et al. (2017) The tomato B‐type cyclin gene, SlCycB2, plays key roles in reproductive organ development, trichome initiation, terpenoids biosynthesis and Prodenia litura defense. Plant Science, 262, 103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z. , Luo, Y. , Zhang, W. , Jian, W. , Zhang, L. , Gao, X. et al. (2021) A SlMYB75‐centred transcriptional cascade regulates trichome formation and sesquiterpene accumulation in tomato. Journal of Experimental Botany, 72, 3806–3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, B. , Chang, J. , Wu, M. , Xu, Z. , Zhang, F. , Yang, M. et al. (2021) Mediation of JA signalling in glandular trichomes by the woolly/SlMYC1 regulatory module improves pest resistance in tomato. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 19, 375–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, B. , Chang, J. , Xu, Z. , Han, X. , Xu, M. , Yang, M. et al. (2021) HOMEODOMAIN PROTEIN8 mediates jasmonate‐triggered trichome elongation in tomato. The New Phytologist, 230, 1063–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W. , Peng, S. , Xian, Z. , Lin, D. , Hu, G. , Yang, L. et al. (2017) Overexpression of a tomato miR171 target gene SlGRAS24 impacts multiple agronomical traits via regulating gibberellin and auxin homeostasis. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 15, 472–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, N.R. , Kim, H. , Hwang, I.T. , Howe, G.A. & Kang, J.H. (2017) Genetic analysis of the tomato inquieta mutant links the ARP2/3 complex to trichome development. Journal of Plant Biology, 58, 450–457. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.H. , Liu, G. , Shi, F. , Jones, A.D. , Beaudry, R.M. & Howe, G.A. (2010) The tomato odorless‐2 mutant is defective in trichome‐based production of diverse specialized metabolites and broad‐spectrum resistance to insect herbivores. Plant Physiology, 154, 262–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.‐H. , McRoberts, J. , Shi, F. , Moreno, J.E. , Jones, A.D. & Howe, G.A. (2014) The flavonoid biosynthetic enzyme chalcone isomerase modulates terpenoid production in glandular trichomes of tomato. Plant Physiology, 164, 1161–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, G.G. (2003) Tomato, pests, parasitoids, and predators: tritrophic interactions involving the genus Lycopersicon . Annual Review of Entomology, 48, 51–72. Available from: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckie, B.M. , D'Ambrosio, D.A. , Chappell, T.M. , Halitschke, R. , De Jong, D.M. , Kessler, A. et al. (2016) Differential and synergistic functionality of acylsugars in suppressing oviposition by insect herbivores. PLoS One, 11, e0153345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn, E. , Schalechet, F. , Wilkinson, J. , Matsui, K. , Tadmor, Y. , Nam, K.H. et al. (2001) Enhanced levels of the aroma and flavor compound S‐linalool by metabolic engineering of the terpenoid pathway in tomato fruits. Plant Physiology, 127, 1256–1265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. , Williams, M.M. , Loh, Y.T. , Lee, G.I. & Howe, G.A. (2002) Resistance of cultivated tomato to cell content‐feeding herbivores is regulated by the octadecanoid‐signaling pathway. Plant Physiology, 130, 494–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. , Zhao, Y. , McCaig, B.C. , Wingerd, B.A. , Wang, J. , Whalon, M.E. et al. (2004) The tomato homolog of CORONATINE‐INSENSITIVE1 is required for the maternal control of seed maturation, jasmonate‐signaled defense responses, and glandular trichome development. Plant Cell, 16, 126–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. , Shi, Y. , Zhu, N. , Zhong, S. , Bouzayen, M. & Li, Z. (2020) SlGRAS4 mediates a novel regulatory pathway promoting chilling tolerance in tomato. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 18, 1620–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio, R. & Rausher, M.D. (1997) Experimental manipulation of putative selective agents provides evidence for the role of natural enemies in the evolution of plant defense. Evolution, 51(5), 1435–1444. Available from: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb01467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, E.T. , Kapteyn, J. , Schmidt, A. , Li, C. , Kang, J.H. , Descour, A. et al. (2011) Comparative functional genomic analysis of Solanum glandular trichome types. Plant Physiology, 155, 524–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y. , Zhao, T. , Xu, X. & Li, J. (2017) Genome‐wide identification and characterization of GRAS transcription factors in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). PeerJ, 5, e3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanaik, S. , Patra, B. , Singh, S.K. & Yuan, L. (2014) An overview of the gene regulatory network controlling trichome development in the model plant, Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science, 5, 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, S. , Lin, P.A. , Foolad, M.R. , Ali, J.G. , Rajotte, E.G. & Felton, G.W. (2019) Induced plant defenses against herbivory in cultivated and wild tomato. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 45, 693–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilmiller, A.L. , Last, R.L. & Pichersky, E. (2008) Harnessing plant trichome biochemistry for the production of useful compounds. The Plant Journal, 54, 702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilmiller, A.L. , Miner, D.P. , Larson, M. , McDowell, E. , Gang, D.R. , Wilkerson, C. et al. (2010) Studies of a biochemical factory: tomato trichome deep expressed sequence tag sequencing and proteomics. Plant Physiology, 153, 1212–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , Hu, G. , Wang, Y. , Liang, Q. , Su, D. , Lu, W. et al. (2024) The SlGRAS9‐SlZHD17 transcriptional cascade regulates chlorophyll and carbohydrate metabolism contributing to fruit quality traits in tomato. The New Phytologist, 241(6), 2540–2557. Available from: 10.1111/nph.19530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , Pang, X. , Liu, W. , Wang, R. , Su, D. , Gao, Y. et al. (2021) SlZHD17 is involved in the control of chlorophyll and carotenoid metabolism in tomato fruit. Horticulture Research, 8, 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H. , Wang, X. , Guo, H. , Cheng, Y. , Hou, C. , Chen, J.‐G. et al. (2017) NTL8 regulates trichome formation in Arabidopsis by directly activating R3 MYB genes TRY and TCL1 . Plant Physiology, 174, 2363–2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissier, A. (2012) Glandular trichomes: what comes after expressed sequence tags? The Plant Journal, 70, 51–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. , Park, Y.‐L. & Gutensohn, M. (2020) Glandular trichome‐derived sesquiterpenes of wild tomato accessions (Solanum habrochaites) affect aphid performance and feeding behavior. Phytochemistry, 180, 112532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werker, E. (2000) Trichome diversity and development. Advances in Botanical Research, 31, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. , Bian, X. , Hu, S. , Huang, B.B. , Shen, J.Y. , du, Y.D. et al. (2024) A gradient of the HD‐zip regulator Woolly regulates multicellular trichome morphogenesis in tomato. Plant Cell, 36, 2375–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q. , Xiong, C. , Yang, Q. , Zheng, F. , Larkin, R.M. , Zhang, J. et al. (2022) A novel regulatory complex mediated by Lanata (ln) controls multicellular trichome formation in tomato. The New Phytologist, 236, 2294–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. , van Herwijnen, Z.O. , Dräger, D.B. , Sui, C. , Haring, M.A. & Schuurink, R.C. (2018) SlMYC1 regulates type VI glandular trichome formation and terpene biosynthesis in tomato glandular cells. Plant Cell, 30(12), 2988–3005. Available from: 10.1105/tpc.18.00571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. , Li, H. , Zhang, J. , Luo, Z. , Gong, P. , Zhang, C. et al. (2011) A regulatory gene induces trichome formation and embryo lethality in tomato. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108, 11836–11841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. , Marillonnet, S. & Tissier, A. (2021) The scarecrow‐like transcription factor SlSCL3 regulates volatile terpene biosynthesis and glandular trichome size in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). The Plant Journal, 107, 1102–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. & Ye, Z. (2013) Trichomes as models for studying plant cell differentiation. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 70, 1937–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. , Xu, X. , Luo, Y. , Gong, Z. , Hu, X. , Wu, M. et al. (2021) R2R3 MYB‐dependent auxin signalling regulates trichome formation, and increased trichome density confers spider mite tolerance on tomato. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 19, 138–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Song, H. , Wang, X. , Zhou, X. & Wang, A. (2020) The roles of different types of trichomes in tomato resistance to cold, drought, whiteflies, and botrytis. Agronomy, 10, 411. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. The transcript levels of GRAS genes in cultivated (LA4024) and wild (LA1777) tomato cultivars.

Figure S2. SlGRAS9 was highly expressed in trichome‐rich tissues.

Figure S3. Trichome density in different tomato accessions.

Figure S4The expression levels of tomato TPS genes in leaves of Slgras9‐CR plants.

Figure S5. The expression levels of tomato TPS genes in petals of Slgras9‐CR plants.

Figure S6. The expression levels of tomato TPS genes in fruit trichomes of Slgras9‐CR plants.

Figure S7. The regulatory effect of SlGRAS9 on TPS genes.

Figure S8. Protein–protein interaction between SlGRAS9 and other trichome‐related proteins.

Figure S9. Trichome density in SlMYC1‐OE plants.

Figure S10. Fecundity analysis of two‐spotted spider mites on WT, Slgras9‐CR, SlMYC1‐OE, and Slmyc1‐CR plants.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Supporting Information of this article.