Abstract

In the present investigation, 49 Aspergillus fumigatus isolates obtained from four nosocomial outbreaks were typed by Afut1 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis and three PCR-based molecular typing methods: random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis, sequence-specific DNA primer (SSDP) analysis, and polymorphic microsatellite markers (PMM) analysis. The typing methods were evaluated with respect to discriminatory power (D), reproducibility, typeability, ease of use, and ease of interpretation to determine their performance and utility for outbreak and surveillance investigations. Afut1 RFLP analysis detected 40 types. Thirty types were observed by RAPD analysis. PMM analysis detected 39 allelic types, but SSDP analysis detected only 14 types. All four methods demonstrated 100% typeability. PMM and RFLP analyses had comparable high degrees of discriminatory power (D = 0.989 and 0.988, respectively). The discriminatory power of RAPD analysis was slightly lower (D = 0.971), whereas SSDP analysis had the lowest discriminatory power (D = 0.889). Overall, SSDP analysis was the easiest method to interpret and perform. The profiles obtained by PMM analysis were easier to interpret than those obtained by RFLP or RAPD analysis. Bands that differed in staining intensity or that were of low intensity were observed by RAPD analysis, making interpretation more difficult. The reproducibilities with repeated runs of the same DNA preparation or with different DNA preparations of the same strain were high for all the methods. A high degree of genetic variation was observed in the test population, but isolates were not always similarly divided by each method. Interpretation of band profiles requires understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for genetic alternations. PMM analysis and Afut1 RFLP analysis, or their combination, appear to provide the best overall discriminatory power, reproducibility, ease of interpretation, and ease of use. This investigation will aid in planning epidemiologic and surveillance studies of A. fumigatus.

Aspergillus fumigatus is a saprophytic fungus with a worldwide distribution and an ecological niche primarily of decomposing plant matter, organic debris, and soil, where it can release large numbers of airborne conidia (23). A. fumigatus is an important opportunistic fungal pathogen, especially for immunocompromised persons, in whom it may cause life-threatening invasive aspergillosis (23). The number of reports of invasive infections caused by A. fumigatus has been rising, in part due to the increasing number of immunocompromised, especially neutropenic patients (12, 16, 17).

Effective prevention strategies may be enhanced by a better understanding of the environmental sources and the routes of infection of A. fumigatus strains involved in infections. Inhalation of airborne spores into the lungs is the most likely route of infection; alternatively, aerosolized waterborne Aspergillus or fomites may be a potential source of aspergillosis (1, 8, 28). Epidemiologic investigations would be facilitated by a reliable, simple, and rapid typing system in order to resolve medically relevant questions regarding the source of outbreaks and the strains involved in outbreaks, help develop improved guidelines for patient management, and determine the existence and frequency of pathogenic strains. Several molecular methods have been applied for evaluations of the genetic epidemiology of A. fumigatus. Briefly, these molecular typing methods include isoenzyme electrophoresis (IE) or multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (33, 34) and analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs). RFLP analysis includes restriction endonuclease analysis (REA) (10, 14), hybridization with a heterologous probe specific for the nontranscribed region of the rRNA gene (37), or analysis of hybridization profiles with a dispersed, repetitive DNA probe denoted as bacteriophage lambda 3.9 or Afut1 (18, 29). Plasmid pFOLT4R4 harboring Fusarium oxysporum telomeric sequences (39) or bacteriophage M13 (2) also displayed complex patterns of hybridization bands but were used in single investigations. PCR-based methods include arbitrarily primed PCR or randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis (3, 24, 41), sequence-specific DNA primer (SSDP) analysis (9, 27), and analysis of polymorphic microsatellite markers (PMMs) (4).

While the number of molecular typing methods for A. fumigatus appears to be formidable, these procedures may not be ideal for aspergillosis outbreak or surveillance investigations. For instance, RFLP analysis with Southern blotting may be tedious and labor intensive, and PMM analysis requires specialized or expensive equipment. RAPD analysis suffers from a lack of reproducibility and difficulty of interpretation of the profiles (5, 25). REA suffers from an inability to determine the degree of genetic relatedness, and interpretation of the profiles is subjective (25). Of increasing concern is knowing how to interpret conflicting data obtained by multiple typing methods (5, 25, 33, 35, 42). The investigation described here compared the performance of Afut1 RFLP analysis with the performance of three PCR-based typing methods, RAPD, SSDP, and PMM analyses, to determine their epidemiologic utilities for A. fumigatus outbreak and surveillance investigations. Few investigators have directly evaluated the performance of Afut1 RFLP analysis and RAPD analysis and the performance of the more recently introduced methods, SSDP analysis and PMM analysis, with respect to typeability, discriminatory power, reproducibility, ease of use, and ease of interpretation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

The 49 isolates of A. fumigatus, 2 isolates of Aspergillus flavus, and 1 isolate of Aspergillus niger used in this study are described in Table 1. These included 19 isolates obtained from either hospital A in Pennsylvania or hospital B in Washington, D.C. (25). Five isolates were obtained from a cluster of cases of invasive aspergillosis in liver transplant patients (30). An additional 10 isolates were obtained from a cluster of invasive aspergillosis in cardiac transplant patients in Buffalo, N.Y., and an additional 15 isolates were taken from the fungal culture collection maintained by the Mycotic Diseases Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (25). Species identification was based on the colonial and microscopic morphologies of isolates (21, 32). Conidial suspensions from single spores of isolates were frozen in 50% glycerol phosphate buffer (20).

TABLE 1.

A. fumigatus isolates, isolate sources, and genotypes determined by Afut1 RFLP, RAPD, SSDP, and PMM analysesa

| Isolate | Source | Geographic location | Type obtained by:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afut1 RFLP analysis | RAPD analysis | SSDP analysis | PMM analysis | |||

| 19723 | Clinical | CDC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B-1014 | Clinical | Florida | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| B-1015 | Clinical | Honduras | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| B-4210 | Clinical | CDC | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| B-4211 | Clinical | CDC | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| B-5051 | Clinical | Alabama | 3 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| B-5211 | Clinical | Pennsylvania | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| B-5212 | Clinical | Pennsylvania | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| B-5213 | Clinical | Pennsylvania | 6 | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| B-5214 | Clinical | Pennsylvania | 7 | 7 | 3 | 8 |

| B-5215 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 8 | 8 | 2 | 9 |

| B-5216 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 9 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| B-5217 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 10 | 9 | 8 | 10 |

| B-5218 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 10 | 10 | 6 | 11 |

| B-5225 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 10 | 10 | 3 | 10 |

| B-5226 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 11 | 11 | 2 | 12 |

| B-5227 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 12 | 11 | 9 | 12 |

| B-5228 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 13 | 10 | 6 | 10 |

| B-5230 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 14 | 11 | 9 | 12 |

| B-5231 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 15 | 11 | 4 | 13 |

| B-5232 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 16 | 7 | 3 | 14 |

| B-5233 | Envir | Pennsylvania | 17 | 4 | 10 | 15 |

| B-5257 | Envir | Indiana | 18 | 12 | 3 | 16 |

| B-5262 | Clinical | Washington, D.C. | 19 | 3 | 11 | 17 |

| B-5263 | Clinical | Washington, D.C. | 20 | 13 | 3 | 18 |

| B-5267 | Clinical | Washington, D.C. | 19 | 15 | 3 | 19 |

| B-5309 | Clinical | Pennsylvania | 21 | 16 | 12 | 20 |

| B-5355 | Clinical | New York | 22 | 17 | 11 | 21 |

| B-5356 | Envir | New York | 23 | 18 | 7 | 22 |

| B-5357 | Clinical | New York | 24 | 19 | 11 | 23 |

| B-5358 | Envir | New York | 25 | 20 | 11 | 24 |

| B-5359 | Envir | New York | 26 | 19 | 13 | 25 |

| B-5360 | Envir | New York | 33 | 11 | 11 | 18 |

| B-5361 | Clinical | New York | 32 | 7 | 11 | 27 |

| B-5362 | Envir | New York | 31 | 21 | 5 | 28 |

| B-5363 | Envir | New York | 30 | 1 | 6 | 29 |

| B-5364 | Envir | New York | 29 | 22 | 11 | 30 |

| B-5447 | Clinical | CDC | 28 | 23 | 7 | 31 |

| B-5450 | Clinical | CDC | 27 | 24 | 9 | 32 |

| B-5451 | Clinical | CDC | 40 | 25 | 7 | 33 |

| B-5854 | Clinical | California | 37 | 26 | 6 | 34 |

| B-5856A | Clinical | California | 38 | 27 | 7 | 35 |

| B-5856B | Clinical | California | 37 | 28 | 6 | 36 |

| B-5859 | Clinical | California | 38 | 27 | 7 | 35 |

| B-5863 | Envir | California | 37 | 29 | 3 | 34 |

| 36607 | Clinical | ATCC | 47 | 35 | 7 | 33 |

| 42202 | Clinical | ATCC | 48 | 36 | 7 | 34 |

| 64026 | Clinical | ATCC | 35 | 4 | 7 | 26 |

| 12B | Envir | Georgia | 34 | 3 | 11 | 39 |

| A. flavus | Clinical | CDC | X | 39 | X | X |

| A. flavus | Clinical | CDC | X | 40 | X | X |

| A. niger | Envir | CDC | X | 41 | X | X |

Abbreviations: Envir, environmental; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection: X, hybridization bands or PCR amplification was not observed.

Purification of genomic DNA.

Cultures were shaken in Sabouraud dextrose broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and harvested by filtration, and mycelium frozen in liquid nitrogen was pulverized in a mortar and pestle (25). A. fumigatus genomic DNA was purified by either repeated phenol-chloroform extractions (20, 22) or elution through Genomic G-100 columns (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) with the buffers and according to the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. The relative concentrations of genomic DNA extracts were determined with a Lumi-Imager F1 workstation (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, Ind.).

Afut1 hybridization.

Purified genomic DNA (3 μg) was digested with 50 U of EcoRI (Roche Diagnostics Corp.) for 6 h at 37°C. EcoRI restriction fragments were electrophoresed through 25-cm 0.7% agarose gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) in TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) for 16 h at 2.5 V/cm. Restriction fragments were capillary blotted overnight onto positively charged nylon membranes (Roche Diagnostics Corp.) by using 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M sodium chloride plus 0.015 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0]). The membranes were hybridized and washed as described by Girardin et al. (18), except that Afut1 DNA was labeled with digoxigenin by random priming and hybridization bands were visualized with the reagents and by the protocol supplied in the Genius kit (Roche Diagnostics Corp.). Afut1 DNA was kindly provided by D. R. Soll (University of Iowa). Gel-to-gel runs were standardized by including EcoRI-digested A. fumigatus ATCC 42202 genomic DNA and 1-kb extension ladder molecular size markers (Life Technologies) on all gels. Hybridization profiles with bands with identical numbers and sizes were considered indistinguishable. Isolates were assigned a different type by Afut1 RFLP analysis when two or more band differences were observed between hybridization profiles (5, 30).

RAPD analysis.

Primers R108, R151, and UBC90 for RAPD analysis, the conditions for PCR amplification, reagents, agarose gel electrophoresis, and inspection and interpretation of ethidium bromide-stained gels were as described by Lin et al. (25). Likewise, primer NS3, the PCR conditions, reagents, agarose gel electrophoresis, and inspection and interpretation of ethidium bromide-stained gels were previously described by Rodriguez et al. (35), except that PCR amplification was performed with a Perkin-Elmer Gene Amp 9700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Ethidium bromide staining intensities were ignored for comigrating bands, and isolates observed to have differences in a single intense band were assigned different RAPD types (5, 25).

SSDP analysis.

The five pairs of primers for SSDP analysis, the PCR amplification conditions, reagents, resolution of the amplified PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis, and genotyping were as described previously by Mondon et al. (27), except that AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics Corp.) was used instead of Replitherm DNA polymerase, and the reaction mixtures were not overlaid with mineral oil. The patterns obtained by SSDP analysis were scored as the presence or the absence of the appropriately sized PCR product for each primer pair on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels (27).

PMM analysis.

Reaction conditions and the four primer pairs used for PMM analysis were as described by Bart-Delabesse et al. (4). PCR amplification was performed with Taq DNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics Corp.) in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). The PCR products were resolved by capillary electrophoresis with polymer POP-4 (Applied Biosystems) in an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and were analyzed with GeneScan Analysis software (version 2.1; Applied Biosystems). Each sample for analysis contained GeneScan 500 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine size standards (Applied Biosystems). The observation of differences in band sizes among the strains in analyses with one of the PMMs was used to assign alleles to a different PMM allelic type (4).

Band analysis.

A Fluor-S-Multimager instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) was used to scan the band profiles, and the image was digitized with Diversity Database software (Bio-Rad). The program calculates the molecular weights for individual bands, subtracts the background, and normalizes the profiles between different lanes of the same gel or profiles between different gels so that they can be compared. The unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages was used to determine the genetic relatedness of the isolates (20).

Discriminatory power and reproducibility.

The discriminatory power of a typing method (D) is the mathematical probability that two unrelated isolates chosen at random from a test population can be shown to belong to different groups. Discriminatory power was calculated in the manner described by Hunter (19). When all isolates tested are a different type, D is equal to 1. Conversely, D is equal to 0 when all isolates are the same type. Reproducibility is the ability to assign an identical type to the same isolate by a repeat assay. The reproducibility of each of the four typing methods was examined by running the same DNA preparation repeatedly and by analysis of a second DNA preparation from the isolates (38).

RESULTS

Afut1 RFLP analysis.

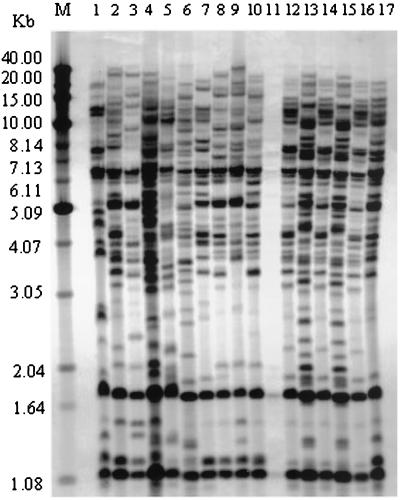

Hybridization of A. fumigatus EcoRI genomic blots with digoxigenin-labeled Afut1 DNA showed a high degree of discriminatory power. Forty different Afut1 types were observed (D = 0.988). Types 2 and 10 were the most common Afut1 types, containing four and three isolates, respectively (Table 1). Thirty-five Afut1 types were represented by single isolates (Table 1). The hybridization profiles were indistinguishable for a second DNA preparation obtained from the same isolate or after an aliquot of the same DNA preparation was rerun. Hybridization profiles consisted of between 20 and 40 intense or faint bands of between 1.1 and 40 kb. A typical Afut1 RFLP hybridization profile is shown in Fig. 1. Gels 25 cm in length provided band resolution superior to that provided by gels 15 cm in length (data not shown). Differences in hybridization profiles between isolates were generally easy to recognize; however, several of the intense bands may be composed of two or more restriction fragments. Of the 49 isolates examined, the hybridization profile observed for isolate ATCC 36607 displayed considerably lower band intensity than those observed for the 48 other isolates (Fig. 1, lane 11). A. fumigatus was 100% typeable. No hybridization bands were observed following hybridization of A. flavus or A. niger genomic blots with the Afut1 probe.

FIG. 1.

Southern blotting profiles of EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs of 17 A. fumigatus isolates (lanes 1 to 17, respectively) hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled Afut1 DNA. Lane M, molecular size standards, with the sizes indicated on the left.

RAPD analysis.

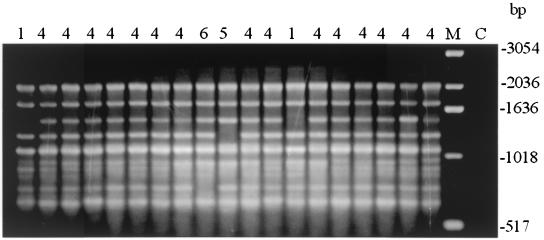

The discriminatory powers of the individual RAPD primers were variable. Primer R108 displayed the highest degree of discriminatory power (D = 0.902), identifying 17 types. The discriminatory powers for RAPD primers UBC90, NS3, and R151 were 0.709, 0.615, and 0.582, respectively. Combination of the amplification profiles obtained with the four RAPD primers resulted in 30 RAPD types, with 20 types represented by single isolates (D = 0.971). The most common RAPD types, types 2 and 10, harbored five isolates each (Table 1). Figure 2 shows a typical RAPD profile. Repeated amplification with DNA from the same preparation or from a second DNA preparation showed occasional bands that were difficult to interpret since either differences in staining intensities or the presence of faint bands was observed. Incorrect scoring may occur since intensely staining bands may be composed of comigrating nonhomologous amplicons. Profiles were observed for both A. flavus and A. niger by RAPD analysis with all four primers (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

RAPD profiles produced by amplification with primer NS3 electrophoresed through a 1.5% agarose gel. The numbers above the lanes denote the NS3 genotype. Lane M, molecular size standards, with the sizes indicated on the right; lane C, control consisting of the PCR mixture without DNA template.

SSDP analysis.

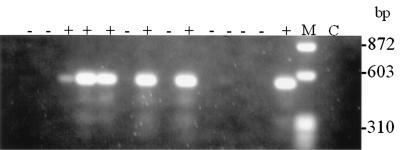

Overall, SSDP analysis detected 14 different SSDP types; seven SSDP types were represented by single isolates (Tables 1 and 2). The most common SSDP types, types 3 and 7, were composed of 10 and 9 isolates, respectively. SSDP analysis showed a moderate degree of discriminatory power (D = 0.889). The level of reproducibility was high, and the SSDP profiles were generally easy to score, as they were scored for the presence or the absence of the PCR band of the appropriate size. Figure 3 shows a typical SSDP profile. The preponderance of amplified bands stained intensely. Low-intensity bands were occasionally observed after amplification with primer pairs SSDP 2, 3, and 4 (Fig. 3, lane 3) but not with primer pairs SSDP 1 and 5. Southern blot analysis with the appropriate digoxigenin-labeled SSDP fragment as a probe showed a positive hybridization signal and, consequently, scored positive (data not shown). Only the primer pair specific for SSDP 5 showed a very low ability to discriminate among the isolates. No amplicons were observed with A. flavus and A. niger genomic DNA preparations by SSDP analysis with any of the five primer pairs (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Discriminatory powers of typing methods and combinations of methods

| Typing method | No. of types | No. of isolates with the same type | D value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afut1 RFLP analysis | 40 | 35 | 0.988 |

| SSDP analysis | 14 | 7 | 0.889 |

| RAPD analysis | 30 | 20 | 0.971 |

| PMM analysis | 39 | 32 | 0.989 |

| RAPD analysis + SSDP analysis | 42 | 35 | 0.994 |

| RAPD analysis + PMM analysis | 43 | 39 | 0.993 |

| SSDP analysis + PMM analysis | 47 | 45 | 0.998 |

| RFLP analysis + SSDP analysis | 47 | 45 | 0.998 |

| RFLP analysis + PMM analysis | 44 | 44 | 0.998 |

| RFLP analysis + RAPD analysis | 44 | 41 | 0.993 |

FIG. 3.

SSDP analysis with SSDP type 3-specific primer pair Afd1 and Afd2. Isolates were scored for the presence (+) or the absence (−) of a 550-bp band. Lane M, molecular size standards, with the sizes indicated on the right; lane C, control consisting of the PCR mixture without DNA template.

PMM analysis.

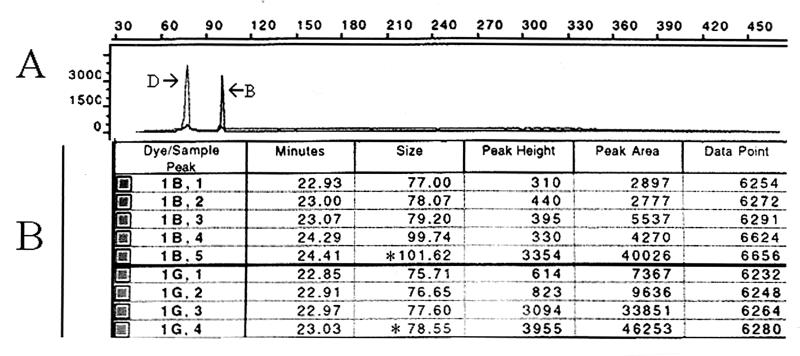

PMM analysis detected 39 PMM allelic types (Tables 1 and 2). Thirty-two allelic types obtained by PMM analysis were represented by single isolates. Three PMM allelic types, types 2, 10, and 12, contained three isolates each. The four primer pairs used for PMM analysis exhibited differences in discriminatory powers. The highest discriminatory power was obtained with primer D (D = 0.925), and the lowest discriminatory power was obtained with primer A (D = 0.768). Of the three PCR-based typing methods, PMM analysis exhibited the highest degree of discriminatory power (D = 0.989) (Table 2). The reproducibilities for different DNA preparations or duplicate runs were high, but analysis required the inclusion of DNA preparations from isolates with alleles of known sizes. The method was easy to interpret since the molecular sizes of the bands were automatically calculated with respect to those of the size standards loaded with each sample. Figure 4 shows two PMM loci, B and D, resolved through the same capillary for isolate 19723. Microsatellites A, B, C, and D showed 100% typeability for all 49 A. fumigatus isolates tested, but no PCR amplification products were observed with A. flavus or A. niger DNA templates (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

PMM analysis of PCR profiles for isolate 19723. (A) Analysis of PCR products was performed with 6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled primer B (←B) and 4,7,2′,4′,5′,7′-hexachloro-6-carboxy-fluorescein-labeled primer D (D→). (B) The molecular sizes of the bands were automatically calculated by using 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine-labeled internal size standards loaded with each sample. Dye-sample peaks were 1B for primer B and 1G for primer D. The sizes of the PCR fragments was calculated by using the maximum height of the fluorescent peak (∗).

Combination of methods.

A high degree of genetic diversity was observed for the 49 isolates of A. fumigatus. A modest increase in discriminatory power was observed by the combination of typing methods (Table 2). For instance, the highest degree of discrimination was observed with the combination of SSDP analysis and PMM analysis, Afut1 RFLP analysis and SSDP analysis, or Afut1 RFLP analysis and PMM analysis (D = 0.998).

DISCUSSION

In this investigation, four molecular typing methods, Afut1 RFLP analysis, RAPD analysis, SSDP analysis, and PMM analysis, were directly compared by analysis of 49 isolates of A. fumigatus obtained from four epidemiologic investigations in order to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each method by using previously recommended performance criteria (19, 26, 38). All four methods demonstrated 100% typeability, which is the proportion of isolates in a population that can be typed. Afut1 RFLP analysis, SSDP analysis, and PMM analysis were species specific; however, amplification products were observed by RAPD analysis for non-A. fumigatus species of Aspergillus. Nonspecific amplification may hamper the analysis if incorrectly identified isolates are analyzed in an outbreak investigation.

Afut1 RFLP and PMM analyses had comparable high degrees of discriminatory power (D = 0.989 and 0.988, respectively) (Table 2). These estimates for the discriminatory power of PMM analysis are in good agreement with those from the investigation by Bart-Delabesse et al. (4) for a collection of 102 isolates obtained from three Paris hospitals (D = 0.994). While each primer used for RAPD analysis displayed a low to moderate degree of discriminatory power, a higher degree of discriminatory power (D = 0.971) was observed after the profiles obtained with the four primers used for RAPD analysis were combined. The discriminatory power for RAPD analysis in this investigation was greater than that which Lin et al. (25) reported previously (D = 0.928). Higher discriminatory power was achieved by two changes. RAPD primers UBC69 and RP4-2 were eliminated from the present analysis because they previously displayed low degrees of discriminatory power; RAPD primer NS3 was therefore included in this investigation. SSDP analysis exhibited a moderate degree of discriminatory power (D = 0.889), whereas Mondon et al. (27) reported that SSDP analysis had a higher discriminatory power (D = 0.96) for a collection of 51 isolates of A. fumigatus. This discrepancy is due to the lack of discrimination observed for primer pair SSDP 5, also recently observed by Bertout et al. (6). The discriminatory power of a typing method is not absolute and changes with respect to the number of test differences needed to establish that two strains are indistinguishable. When the number of test differences required to distinguish between strains increases, the reproducibility increases whereas the discriminatory power is reduced (19). The increased number of test differences predictively lowers the number of genotypes, thereby resulting in an enhanced concordance between methods. One example is the number of test differences used to distinguish genotypes by Afut1 RFLP analysis. Either one (11) or two (5) band differences have been used. Consequently, the difference in one or two test differences may be medically relevant when typing data from an outbreak investigation are being interpreted. These test differences may be interpreted as indicating that microevolutionary changes have occurred in the genomes of closely related strains or, alternatively, may be interpreted as indicating that the strains are unrelated (36).

For all four typing methods, reproducibility was analyzed by rerunning aliquots of DNA from the same preparation and by analysis of different DNA preparations of the same isolate. The profiles obtained by SSDP analysis, RAPD analysis, and Afut1 RFLP analysis on replicate analyses were indistinguishable, as were the allelic profiles identified by PMM analysis. While markers manifest apparent intralaboratory reproducibility, investigation of long-term marker stability in vitro or in vivo was not examined in this investigation.

SSDP analysis was the easiest method to perform, and its profiles were the easiest to interpret, despite the occasional presence of faint bands following PCR amplification (Fig. 3). The faint bands were also observed following amplification with a replicate DNA sample and were not due to a decreased DNA concentration but may have been due to a point mutation in the target sequence that resulted in less efficient amplification. Interpretation of the data obtained by PMM analysis was straightforward because the molecular sizes of the PCR products obtained by PMM analysis were automatically calculated by use of internal size standards loaded with each sample and PMM analysis can detect mixtures of isolates in cultures (4). One disadvantage of PMM analysis is the need for sophisticated and expensive equipment and software for analysis. Alternatively, the amplification products obtained by PMM analysis can be resolved by electrophoresis through 3.5% Metaphore agarose gels (7). PMM analysis may be hampered by two PCR artifacts: the slippage of Taq DNA polymerase and the addition of an extra 3′ adenosine residue. These artifacts may be reduced by using dimethyl sulfoxide in the PCR mixtures and increasing the final extension to 30 min (4). Because of the ease of sample preparation, the ability to assay a large number of isolates, and the need for relatively inexpensive equipment, RAPD analysis is the method perhaps the most widely used for the typing of A. fumigatus. Interpretation of RAPD analysis profiles was occasionally confounded due to changes in the staining intensities of comigrating bands. Due to the low number of markers, the degree of genetic relatedness determined from the profile obtained with a single RAPD primer is not as reliable as that determined from the combination of profiles obtained with several RAPD primers. However, as the number of RAPD primers and profiles increases, interpretation of the profiles and control of the reaction conditions become more difficult, reducing the overall reproducibility (25). Afut1 RFLP analysis has been used to examine the genetic relatedness of hundreds of strains of A. fumigatus (11, 13). It has the advantage of high degrees of discriminatory power and reproducibility (>95%) (13). Southern blot analysis is generally considered more tedious and labor-intensive than PCR methods and is subjected to partial digests. Only ATCC 36607, a clinical isolate, was observed to have an unusual hybridization profile by Afut1 RFLP analysis; its profile was composed of faint hybridization bands (Fig. 1, lane 11). The faint bands were not due to the loading of unequal or reduced amounts of DNA for this isolate (data not shown). The SSDP profile for ATCC 36607 was identical to the SSDP profile for isolates ATCC 42202 and ATCC 64026, and ATCC 36607 DNA was amplified by all four primer pairs used for PMM analysis, indicating that isolate ATCC 36607 was not misidentified.

Whereas there was good agreement between the four typing methods, they were not always able to divide all 49 isolates in a similar fashion (Table 1). Discordant results have been observed between RFLP analysis and RAPD analysis (5, 42), between RAPD analysis and IE analysis (25, 33), and among IE analysis, SSDP analysis, and RAPD analysis (34). RAPD analysis has recently been shown to be less reliable than RFLP analysis or PMM analysis due to mismatched hybridization between the RAPD primer and the target, resulting in the loss or gain of bands (5). It is well known that RAPD profiles are stringently dependent on annealing conditions, hybridization temperature, reagents, primer sequences and concentrations, and equipment (15, 31). Homoplasy may also complicate the interpretation of typing data for outbreak investigations because isolates harboring identical genotypes may not be from a common ancestor due to convergence, parallelism, or reversion. However, the potential for homoplasy is low since A. fumigatus has been reported to have a clonal population (34). The limited number of molecular markers used at present to determine levels of relatedness among isolates suggests the need for a stronger emphasis between molecular typing and population genetics.

As expected, use of a combination of typing methods resulted in a greater degree of discriminatory power than that which can be achieved by a single method (Table 2). Use of a combination of methods achieved a moderate increase in discriminatory power compared to that achieved by PMM analysis or Afut1 RFLP analysis. The price was higher for the combination of methods than for a single method, however, because of the need for increased amounts of labor, throughput, and time; the need for additional specialized equipment and training and for additional reagents; increased costs; and the increased complexity of interpretation of the typing data. A. fumigatus isolates demonstrate a high degree of genetic diversity (Table 1), as was observed previously (4, 13, 14). Because of the higher discriminatory powers of recently reported methods, the ability to identify and segregate isolates into meaningful phenotypic and genotypic groups is more problematic, especially when interpreting discrepant typing data between methods during outbreak investigations (7, 34). Interpretation and comparison of typing data are intimately dependent on knowledge of the molecular mechanism and the rates of occurrence of the mutations responsible for altering the fragment profiles. For example, expansion of PMM loci is by a replication slippage mechanism, whereas a missing SSDP band may be due to a spontaneous mutation, insertion, or deletion in the target sequence, but these are both scored as a single test difference. The importance of knowing the molecular mechanisms for correct interpretation of the typing data is illustrated by a potential three-fragment difference in DNA fragment profiles due to creation of a new restriction site by a point mutation (40).

The combination of typing methods compared in this investigation differs significantly from those compared in previous investigations (5, 6, 35). The isolates analyzed in this investigation were obtained from four epidemiologic clusters and did not consist of a random collection of isolates (25, 30). The collection of isolates was composed of two pairs of isolates indistinguishable by Afut1 RFLP analysis (isolates B-5854 and B-5863 and isolates B-5856A and B-5859) (30) and unrelated isolates (isolates 19723, B-5051, B-5211, B-5230, B-5231, B-5332, and B-5333) previously analyzed by REA, RAPD, and IE analyses (25). The unrelated isolates were clearly distinguished by both Afu1 RFLP analysis and PMM analysis. The genotypes of isolates B-5856A and B-5859 were identical by all four typing methods, whereas those of isolates B-5854 and B-5863 were identical only by Afut1 RFLP analysis and PMM analysis, indicating nonspecific hybridization by the primer sequences used for RAPD analysis or SSDP analysis (5). The inclusion of these isolates is important since the ability to identify identical and unrelated strains is an important requirement for the assessment of typing methods (36). This investigation is the first to identify isolates producing low-intensity profiles, which may lead to difficulties with interpretation, by SSDP analysis and Afut1 RFLP analysis. The array of primers used for RAPD analysis and the amplification conditions used were different from those used in studies reported previously (3, 5, 10). A major distinction exists between the geographic origins of the isolates; large numbers of North American clinical and environmental isolates were analyzed in this investigation, whereas previous investigations analyzed isolates primarily from European sources (4, 5, 7, 13, 27). Finally, this is the first report to determine the discriminatory powers of four molecular typing methods by direct comparison of the profiles for the same collection of isolates instead of by use of a single typing method with different collections of isolates (3, 4, 13, 27).

The best method or combination of methods for outbreak and surveillance investigations is undetermined and is applied heuristically. PMM analysis and Afut1 RFLP analysis were observed to provide the best overall discriminatory power, reproducibility, ease of interpretation, and ease of use for the typing of A. fumigatus; a combination of these methods would provide a better estimate of genetic relatedness. Investigations involving molecular typing may be enhanced by the availability of a standard panel of test strains, longitudinal series of isolates, standard sampling strategies, an optimal number of subclones per sample for typing, a consensus on the acceptable levels of discriminatory power, tests that are reproducible in vivo and in vitro, a standard number of test differences for establishment of genotypic breakpoints, standard methods and reagents, and a means of computer analysis of the typing data. Improvements in correlations between DNA types and phenotypic markers need to be made for determination of pathogenesis and antifungal resistance. It is reasonable to speculate that completion of determination of the nucleotide sequence of the A. fumigatus genome will expedite typing by identifying new markers and their evolutionary significance as well as identifying genetic markers for a sequence-based typing method.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anaissie, E. J., and S. F. Costa. 2001. Nosocomial aspergillosis is waterborne. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:1546-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, M. J., K. Gull, and D. W. Denning. 1996. Molecular typing by random amplification of polymorphic DNA and M13 Southern blot hybridization of related paired isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:87-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aufauvre-Brown, A., J. Cohen, and D. W. Holden. 1992. Use of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA markers to distinguish isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2991-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bart-Delabesse, E., J.-F. Humbert, E. Delabesse, and S. Bretagne. 1998. Microsatellite markers for typing Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2413-2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bart-Delabesse, E., J. Sarfati, J.-P. Debeaupuis, W. van Leeuwen, A. van Belkum, S. Bretagne, and J.-P. Latgé. 2001. Comparison of restriction fragment length polymorphism, microsatellite length polymorphism, and random amplification of polymorphic DNA analysis for fingerprinting Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2683-2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertout, S., F. Renaud, R. Barton, F. Symoens, J. Burnod, M.-A. Piens, B. Lebeau, M.-A. Viviani, F. Chapuis, J.-M. Grillot, M. Mallié, and the European Research Group on Biotype and Genotype ofAspergillus. 2001. Genetic polymorphisms of Aspergillus fumigatus in clinical samples from patients with invasive aspergillosis: investigation using multiple typing methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1731-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertout, S., F. Renaud, T. DeMeeüs, M.-A. Piens, B. Lebeau, M.-A. Viviani, M. Mallié, J.-M. Bastide, and the EBGA Network. 2000. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus strains isolated from the first clinical sample from patients with invasive aspergillosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:375-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouakline, A., C. Lacroix, N. Roux, J. P. Gangneux, and F. Derouin. 2000. Fungal contamination of food in hematology units. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4272-4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenier-Pinchart, M.-P., B. Lebeau, G. Devauassoux, P. Mondon, C. Pison, P. Ambroise-Thomas, and R. Grillot. 1998. Aspergillus and lung transplant recipients: a mycologic and molecular epidemiology study. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 17:972-979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnie, J. P., A. Coke., and R. C. Matthews. 1992. Restriction endonuclease analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus DNA. J. Clin. Pathol. 45:324-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chazalet, V., J.-P. Debeaupuis, S. Sarfati, J. Lortholary, P. Ribaud, P. Shah, M. Cornet, H. V. Thien, E. Gluckman, G. Brücker, and J.-P. Latgé. 1998. Molecular typing of environmental and patient isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus from various hospital settings. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1494-1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasbach, E. J., G. M. Davies, and S. M. Teutsch. 2000. Burden of aspergillosis-related hospitalizations in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:1524-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debeaupuis, J.-P., J. Sarfati, V. Chazalet, and J.-P. Latgé. 1997. Genetic diversity among clinical and environmental isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 65:3080-3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denning, D. W., K. V. Clemons, L. H. Hanson, and D. A. Stevens. 1990. Restriction endonuclease analysis of total cellular DNA of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates of geographically and epidemiologically diverse origin. J. Infect. Dis. 162:1151-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellsworth, D. L., K. D. Rittenhouse, and R. L. Honeycutt. 1993. Artifactual variation in randomly amplified polymorphic DNA banding patterns. BioTechniques 14:214-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser, D. W., J. I. Ward, L. Ajello, and B. D. Plikaytis. 1979. Aspergillosis and other systemic mycoses: the growing problem. JAMA 242:1631-1635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerson, S. L., G. H. Talbot, S. Hurwitz, B. L. Strom, E. J. Lusk, and P. A. Cassileth. 1984. Prolonged granulocytopenia: the major risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with acute leukemia. Ann. Intern. Med. 100:345-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girardin, H., J. P. Latgé, T. Srikantha, B. Morrow, and D. R. Soll. 1993. Development of DNA probes to fingerprinting Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1547-1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter, P. R. 1990. Reproducibility and indices of discriminatory power of microbial typing methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1903-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James, M. J., B. A. Lasker, M. M. McNeil, M. Shelton, D. W. Warnock, and E. Reiss. 2000. Use of a repetitive DNA probe to type clinical and environmental isolates of Aspergillus flavus from a cluster of cutaneous infections in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3612-3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klich, M. A., and J. I. Pitt. 1988. A laboratory guide to common Aspergillus species and their teleomorphs. Division of Food Processing, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, North Ryde, New South Wales, Australia.

- 22.Lasker, B. A., C. M. Elie, T. J. Lott, A. Espinel-Ingroff, L. Gallagher, R. J. Kuykendall, M. E. Kellum, W. R. Pruitt, D. W. Warnock, D. Rimland, M. M. McNeil, and E. Reiss. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of Candida albicans strains isolated from the oropharynx of HIV-positive patients at successive clinic visits. Med. Mycol. 39:341-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latgé, J.-P. 1999. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:310-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leenders, A., A. van Belkum, S. Janssen, S. deMarie, J. Kluytmans, J. Wielenga, B. Löwenberg, and H. Verbrugh. 1996. Molecular epidemiology of an apparent outbreak of invasive aspergillosis in a hematology ward. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:345-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin, D., P. F. Lehmann, B. H. Hamory, A. A. Padhye, E. Durry, R. W. Pinner, and B. A. Lasker. 1995. Comparison of three typing methods for clinical and environmental isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1596-1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maslow, J. N., A. M. Slutsky, and R. D. Arbeit. 1993. Molecular epidemiology: the application of contemporary techniques to typing bacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 17:153-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mondon, P., M. P. Brenier, E. Coursange, B. Lebeau, P. Ambroise-Thomas, and R. Grillot. 1997. Molecular typing of Aspergillus fumigatus strains by sequence-specific DNA primer (SSDP) analysis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 17:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neely, A. N., and M. M. Orloff. 2001. Survival of some medically important fungi on hospital fabrics and plastics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3360-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neuveglise, C., J. Sarfati, J.-P. Latge, and S. Paris. 1996. Afut1, a retrotransposon-like element from Aspergillus fumigatus. Nucleic Acids Res. 8:1428-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pegues, D. A., B. A. Lasker, M. M. McNeil, P. M. Hamm, J. L. Lundal, and B. M. Kubak. 2002. Cluster of invasive aspergillosis in a transplant intensive care unit: evidence of person-to-person airborne transmission. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:412-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penner, G. A., A. Bush, R. Wise, W. Kim, L. Domier, K. Kasha, A. Laroche, G. Scoles, S. J. Molnar, and G. Fedak. 1993. Reproducibility of random amplified polymorphic (RAPD) analysis among laboratories. PCR Methods Appl. 2:112-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raper, K. B., and D. I. Fennell. 1965. The genus Aspergillus. The Williams & Williams Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 33.Rinyu, E., J. Varga, and L. Ferenczy. 1995. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of variability in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2567-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez, E., T. D. Meeüs, F. Renaud, F. Symoens, P. Mondon, M.-A. Piens, B. Lebeau. M. A. Viviani, R. Grillot, N. Nolard, F. Chapuis, A.-M. Tortorano, and J.-M. Bastide. 1996. Multicenter epidemiological study of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2559-2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez, E., F. Symoens, P. Mondon, M. Mallie, M.-A. Piens, B. Lebeau, A.-M. Tortorano, F. Chaib, A. Carlotti, J. Villard, M.-A. Viviani, F. Chapuis, N. Nolard, R. Grillot, and J.-M. Bastide. 1999. Combination of three typing methods for the molecular epidemiology of Aspergillus fumigatus infections. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:181-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soll, D. R. 2000. The ins and outs of DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:332-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spreadbury, C. L., B. W. Bainbridge, and J. Cohen. 1990. Restriction fragment length polymorphisms is isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus probed with part of the intergenic spacer region from ribosomal RNA gene complex of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:1991-1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stuelens, M. J., and the Members of the European Study Group on Epidemiological Markers (ESGEM), of the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID). 1996. Consensus guidelines for appropriate use and evaluation of microbial epidemiologic typing systems. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2:2-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang, C. M., J. Cohen, A. J. Rees, and D. H. Holden. 1994. Molecular epidemiological study of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a renal transplantation unit. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:318-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murrayt, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Belkum, A., W. G. V. Quint, B. E. De Pauw, W. J. G. Melchers, and J. F. Meis. 1993. Typing of Aspergillus species and Aspergillus fumigatus isolates by interrepeat polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2502-2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verweij, P. E., J. F. G. M. Meis, J. Sarfati, J. A. A. Hookamp-Korstanje, J.-P. Latgé. 1996. Genotype characterization of sequential Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2595-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]