Abstract

Summary

Rare genetic variants in genes previously described to be involved in bone monogenic disorders were identified in postmenopausal women split into two groups according to extreme bone mineral density (BMD) values and lumbar spine Z-scores. A pathogenic variant in COL1A2 gene found in a woman with low BMD highlights the overlap between osteogenesis imperfecta and osteoporosis, which may share their genetic etiology. Other variants were not clearly associated with the extreme BMD, suggesting that there is little contribution of rare variants to postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Purpose

We aimed to evaluate whether extreme values of bone mineral density (BMD) in a population-based cohort of postmenopausal women (BARCOS) could be determined by rare genetic variants in genes related to monogenic bone disorders.

Methods

A panel of 127 genes related to different skeletal phenotypes was designed. Massive sequencing by targeted capture of these genes was performed in 104 DNA samples from those women of the BARCOS cohort that exhibited the highest (HZ group) and lowest (LZ group) LS Z-scores, ranging from + 0.70 to + 3.80 and from − 2.35 to − 4.26, respectively. 5’UTR, 3’UTR, splice region, missense, nonsense, and short indel variants with MAF < 0.01 were annotated with CADD version 1.6 and considered in the analysis.

Results

After filtering those variants with CADD > 25 and present only in one of the groups (either LZ or HZ), six variants were detected, most of which (5/6) were in the LZ group in TCIRG1, COL1A2, SEC24D, LRP4, and ANO5 genes, while only one, in the LMNA gene, was in the HZ group. According to the ClinVar database, the COL1A2 variant, causative of a recessive form of osteogenesis imperfecta, is described as pathogenic, while the other variants are considered of uncertain significance (VUS).

Conclusion

The variant identified in COL1A2 in a woman from the LZ group highlights the genetic overlap between monogenic diseases such as osteogenesis imperfecta and complex diseases like osteoporosis. However, the other variants were not clearly associated with the extreme BMD, suggesting that there is little contribution of rare variants to postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00198-025-07413-4.

Keywords: Bone mineral density, COL1A2, Osteoporosis, Osteogenesis imperfecta, Rare variants

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a disease characterized by a reduction of bone mineral density (BMD) that is associated with skeletal fragility. OP is especially prevalent in postmenopausal women, in whom estrogen decline constitutes the most important factor for the accelerated loss of bone mass. Other important risk factors for postmenopausal osteoporosis include advanced age, genetics, smoking, and low body weight, in addition to many diseases and drugs that impair bone health [1–3].

In the last decade, numerous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been conducted as a strategy to identify new genes and variants associated with complex diseases. In the field of OP, a number of GWAS have been performed to determine genetic association with BMD and osteoporotic fractures [3]. Initial GWAS studies have identified more than 50 loci associated with BMD [4–8]. Some of these loci correspond to genes involved in skeletal disorders other than OP, such as osteogenesis imperfecta (OI).

Although OP is a common complex disease and OI is a monogenic rare disease, both conditions are associated with bone fragility and increased fracture risk, even though the severity is usually much higher in OI [9]. Therefore, the fact that both disorders share several clinical features poses a diagnostic challenge for some mild forms of OI or severe OP. In fact, variants in genes such as COL1A1 and COL1A2 have been associated with both disorders [10–12] suggesting that some rare variants in OI genes might contribute importantly to the pathophysiology of—or even be responsible for—some cases of postmenopausal osteoporosis.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate whether rare genetic variants in genes associated with several bone phenotypes, particularly OI, could contribute to the development of extreme BMD values in patients without clear features of skeletal monogenic disorders. To do so, we investigated the presence of rare genetic variants in selected genes in a subset of women with the highest and the lowest lumbar spine (LS) Z-score values in a population-based cohort of postmenopausal women from the Barcelona area (BARCOS cohort).

Materials and methods

Study participants

The BARCOS cohort has been previously described [13, 14]. In short, it is a cross-sectional population-based cohort that includes unselected postmenopausal women from the Barcelona area, without known mineral metabolic disorders, except for potential primary postmenopausal osteoporosis. BMD was measured (g/cm2) in the lumbar spine (LS) (L1–L4) and the non-dominant femoral neck (FN) using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Hologic QDR 4500 SL, Hologic, Waltham, Mass). In our center, the technique has an in vivo coefficient of variance (CV) of 1.0% for the LS and 1.65% for the FN measurements. All participants underwent a baseline DXA and collection of a series of clinical variables. In addition, most had blood drawn for DNA extraction. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. For this study, LS Z-scores were ordered from the highest to the lowest values. Two groups were created according to the highest and lowest Z-score values from the cohort (HZ and LZ groups, respectively). LS DXA images were carefully examined by an expert clinician to exclude those DXA exams with artifacts. Bioethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Universitat de Barcelona (IRB00003099).

Candidate gene selection

A literature-based selection of 127 BMD-related genes, corresponding to 0.5 Mb of exonic regions, was used in the design of a Roche KAPA Hyper Choice custom-capture kit. Genes were prioritized based on their relation to OI or OP as follows: First, genes with reported pathogenic variants causing OI or other bone-related diseases [15–21], and these were completed with genes associated with BMD in the GWAS studies from Morris et al. [8] and Estrada et al. [5] (supplemental table S1).

Sequencing analysis and genetic variant prioritization

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Library preparation and sequencing were performed at CNAG facilities (Barcelona, Spain). Captured fragments were sequenced in an Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Reads were then aligned to the hg38 reference genome with Burrows-Wheeler Alignment Tool (BWA-mem), duplicate-marked, recalibrated, and sorted before calling variants with the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) haplotype caller (V4) following GATK standard parameters. Quality-filtering following GATK recommended hard filters (https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us/articles/360035890471-Hard-filtering-germline-short-variants) was applied. Intergenic, intragenic, intronic, upstream and downstream gene variants, as well as synonymous variants were excluded. Finally, 5’UTR, 3’UTR, splice region, missense, nonsense, and short indel variants were annotated with Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) version 1.6 and considered in the analysis.

Gene-Based Burden Testing

The Variant Call Format (VCF) file and a file containing sample information were used as input files. Genotypes that had > 5% of unavailable calls were filtered out, variants with 0 samples mutated were also excluded, and no outlier samples were filtered by the number of mutations nor the transversion/transition (tv/tr) ratio. In order to perform burden tests on the rare variants of the gene panel, R script “rvGWAS_numeric_phenotype. R” was used. The input files used were the output files from the quality control script. To assess rare variants with pathogenic prediction, variants were filtered out when the frequency of the variant was > 0.01 and CADD score was lower than 15. Bayesian rare variant Association Test using Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (BATI) [22].

Results

Patient characteristics

Among the 104 samples from the BARCOS cohort representing the truncated ends of the Z-score distribution (52 from each extreme), 3 samples with highest Z-score did not pass the quality control. Finally, 49 samples belonging to the HZ group (Z-score range 0.70–3.80) and 52 from the LZ group (Z-score range − 4.26 to − 2.35), were included in the analysis. Clinical and densitometric characteristics of these 101 postmenopausal women are summarized in Table 1 and Supplemental Table S2. Age and years since menopause were not different between groups, while average body mass index (BMI) was significantly lower in women from the LZ group. As expected, more women from the LZ group had sustained fragility fractures compared to the HZ subset.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and lumbar spine and femoral neck DXA values of the truncated BARCOS cohort

| Patient characteristics | LZ group (n = 52) | HZ group (n = 49) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) ± SD | 55.19 ± 8.465 | 55.3 ± 6.774 |

| Mean LS BMD ± SD | 0.628 ± 0.072 | 1.170 ± 0.086*** |

| Mean FN BMD ± SD | 0.624 ± 0.121 | 0.875 ± 0.115*** |

| Mean BMI ± SD | 25.939 ± 3.976 | 29.115 ± 4.665** |

| LS Z-score ± SD | − 2.689 ± 0.350 | 1.328 ± 0.608*** |

| FN Z-score ± SD | − 1.228 ± 0.929 | 1.06 ± 0.899*** |

| Years since menopause (years) ± SD | 8.42 ± 7.815 | 6.21 ± 6.975 |

| Individuals with fragility fracture, n (%) | 16 (31%) | 0 (0%)*** |

t-test: *(p < 0.05), **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001)

BMD, bone mineral density (g/cm2); BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); LS, lumbar spine; FN, femoral neck; SD, standard deviation

Genetic findings

Two-hundred forty-five variants with a MAF < 0.01 remained after filtering which belonged to 78 genes (data not shown). Next, we selected those with the highest functional scores (cutoff = 25 in CADD), located within coding regions and identified only in one of the groups (either LZ or HZ). Finally, six variants were selected and looked for in the ClinVar (VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine) [23] and in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®), in order to know their clinical classification (Table 2). The main reason for the discrepancy between both databases is the source they use to get the information: mainly clinical laboratories for ClinVar and scientific publications for HGMD. Interestingly, most of them (5/6) were present in the LZ group (in genes TCIRG1, COL1A2, SEC24D, LRP4, and ANO5), and only one was from the HZ group (in the LMNA gene). According to the VarSome pathogenicity predictor, only variant p.Gly751Ser in COL1A2 is classified as pathogenic and is associated with OI [24]; the other ones are considered either of uncertain significance (VUS) or benign/likely benign (in the case of the SEC24D variant). According to HGMD, the COL1A2 variant is also classified as pathogenic for OI; the variant in TCIRG1 is absent (although this gene has been associated with osteoclast-rich osteopetrosis [25]; the variant at LRP4 is classified as likely pathogenic and is associated with 46XY disorder of sex development [26] (although this gene has also been implicated in osteosclerosis and high bone mass (HBM) [27]); the SEC24D variant is classified as likely pathogenic and has been related to OI [28]; the ANO5 variant is classified as pathogenic and is related to gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia [29]; and finally, the LMNA variant, which is the only one identified in the HZ subset, is classified as pathogenic and associated with LMNA-linked congenital muscular dystrophy [30, 31].

Table 2.

Rare variants identified in the truncated BARCOS cohort

| Gene | Associated bone phenotype | Variant | Chromosome location | MAF gnomAD | CADD | ClinVar classification (Varsome 30–8–24) | HGMD classification | Sample | LS Z-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCIRG1 | Osteopetrosis | c.2162 T > A p.(Ile721Asn) | chr11: 68050180 | 0.000509 | 31 | VUS | Absent | LZ_52 | − 4.26 |

| COL1A2 | OI | c.2251G > A p.(Gly751Ser) | chr7: 94420604 | N/A | 28.9 | Pathogenic | OI; Pathogenic | LZ_50 | − 3.19 |

| SEC24D | OI/Cole-Carpenter syndrome | c.1576C > T p.(Leu526Phe) | chr4: 118752734 | 0.008910 | 28 | Benign/likely benign | bone fragility disorder; likely pathogenic | LZ_32 | − 2.73 |

| LRP4 | Osteosclerosis /HBM | c.5660C > G p.(Ser1887Cys) | chr11: 46859041 | 0.001088 | 29.4 | VUS; Likely benign | 46,XY disorder of sex development; likely pathogenic | LZ_16 | − 2.43 |

| ANO5 | Gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia | c.2411G > C p.(Cys804Ser) | chr11: 22274744 | N/A | 28.9 | VUS | Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy; pathogenic | LZ_08 | − 2.39 |

| LMNA | Muscular dystrophy | c.1871G > A p.(Arg624His) | chr1: 156138660 | 0.000014 | 25.1 | VUS | Muscular Dystrophy, Emery-Dreifuss; Pathogenic | HZ_48 | 3.70 |

OI, osteogenesis imperfecta; HBM, high bone mass; VUS, variant of uncertain significance

The patient with the lowest LS Z-score of the cohort (− 4.26) carried the TCIRG1 variant. Conversely, the patient with the LMNA variant exhibited the second highest LS Z-score (3.70; Table 2 and Supplemental Table S2). Clinical data on the patient with the COL1A2 variant are presented in the next section.

Variant enrichment analysis (BATI/Burden Test) did not identify any gene with an excess of variants in the LZ samples (Table 3 and Supplemental Table S3). In particular, while only two genes had a positive ΔDIC (SQSTM, LMNA), neither was close to the ΔDIC of 10 (standard cutoff value, considered equivalent to a p-value of 0.001).

Table 3.

Results of BATI on genes involved in bone phenotype

| BATI value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene/gene group | Total mutations | ΔDIC | ΔCPO |

| LMNA | 2 | 6.452 | 0.025 |

| SQSTM1 | 2 | 2.705 | 0.013 |

| OI-related genes | 14 | − 1.122 | − 0.016 |

ΔDIC Deviance Information Criterion difference; ΔCPO Conditional Predictive Ordinate difference

Clinical description of the patient with the pathogenic variant in COL1A2

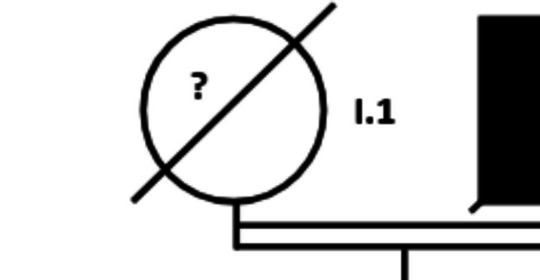

The COL1A2 p.(Gly751Ser) variant, which has been related to OI, was identified in a 73-year-old woman (age at the time of the current study; II.1 in Fig. 1) who presented with densitometric osteoporosis without a history of fractures. This woman has a family history of osteoporosis with fragility fractures (see pedigree in Fig. 1). She is the daughter of consanguineous parents (cousins), both deceased (I.1 and I.2). Her father (I.2) had sustained a femoral fracture and her younger sister (II.2) is diagnosed and treated for very severe densitometric osteoporosis without fractures. No data is available from her other 6 siblings (II.3–8). The proband is married and has a 36-year-old son of whom no data is available. Unfortunately, none of the family members wanted to be part of a further genetic study, so no additional genetic data could be obtained.

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of the family in which the p.(Gly751Ser) variant in the COL1A2 gene was identified. Filled symbols correspond to family members with known skeletal fragility. The arrow identifies the female of whom we obtained the only sample that was genetically analyzed. The white symbols represent family members for whom no information is available (?). Despite the consanguinity of I.1 and I.2 (first cousins), the presence of osteoporosis in two generations suggests a dominant pattern of inheritance, coinciding with the fact that the possibly causal mutation is in heterozygosity

Discussion

Here we aimed to identify rare genetic variants in a list of candidate bone-related genes in order to broaden our understanding of the genetic complexity underlying a quantitative bone trait such as BMD. For this purpose, an in-house bone gene panel was designed and DNA samples from postmenopausal women with extreme lumbar spine BMD values and Z-scores were subjected to next-generation sequencing. After filtering by predicted functionality, six genetic variants were identified. The only one cataloged as pathogenic was a heterozygous variant in the COL1A2 gene.

This variant, p.(Gly751Ser) in COL1A2, has been reported previously. De Paepe et al. [24] identified it in two sibs with severe osteogenesis imperfecta, who were homozygous for the missense change, and in other family members who were heterozygous and presented mild clinical manifestations of OI. Similar to our case, Spotila et al. [32] found this same variant in heterozygosity in a woman with postmenopausal osteoporosis. These cases evidence the phenotypic and genotypic overlap between osteoporosis and mild osteogenesis imperfecta and point to the milder character of the p.(Gly751Ser) variant in heterozygosis, which has been consistently associated with osteoporosis rather than OI.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous skeletal dysplasia characterized by bone fragility, growth deficiency, and skeletal deformity. The most frequent mutations causing OI are single-nucleotide substitutions that replace glycine residues or exon splicing defects in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes that encode the α1(I) and α2(I) collagen chains. Mutant collagen is partially retained intracellularly, and after secretion, it assembles in disorganized fibrils, altering mineralization. Alternatively, truncating mutations lead to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and subsequent quantitative defects (about 50% reduction) of otherwise normal collagens. OI is characterized by a wide range of clinical outcomes ranging from mild forms of skeletal fragility (often related to quantitative defects) to lethal phenotypes [33, 34]. The genetic spectrum of OI includes at least 16 other genes, most of them playing a pivotal role in synthesis, post-translational modification, and processing of type I collagen. All of this heterogeneity leads to a variety of inheritance patterns spanning from autosomal dominant and recessive as well as X-linked recessive which further complicate the disease classification and clinical characterization [19, 35].

Another gene associated with OI for which we found a rare variant is SEC24D, which encodes a component of the COPII complex involved in protein export from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Mutations in this gene have been associated with Cole-Carpenter syndrome, a recessive disorder affecting bone formation, resulting in craniofacial malformations and bones that break easily, as well as a syndromic form of osteogenesis imperfecta. Functional studies of fibroblasts from a Cole-Carpenter syndrome patient displayed moderate accumulation of collagen in a significantly enlarged ER, indicative of a collagen export defect. The patient, a 7-year-old boy, had moderately reduced BMD (− 2.0 SD in a DXA whole body measurement), while the BMD of his heterozygous carrier parents, measured by DXA and peripheral quantitative computed tomography, was in the normal age-adjusted range [28, 36]. The variant found in our study, p.(Leu526Phe), is cataloged as likely pathogenic in HGMD, but the fact that it is present in heterozygosity would make the patient an asymptomatic carrier. Alternatively, we might speculate that the variant, together with other variants that may have gone undetected (such as second mutation in SEC24D or in a SEC23A), might indeed contribute to explain the low BMD (− 2.73) of our patient. Further description of the BMD status of additional heterozygous carriers of this rare form of OI may help clarify the involvement of SEC24D in low bone mass phenotypes.

The woman with the lowest LS Z-score of our cohort carried the variant p.(Ile721Asn) in the T-cell immune regulator 1 gene (TCIRG1), which encodes the α3 subunit of the vacuolar ATPase proton pump involved in acidification of the osteoclast resorption lacuna and in secretory lysosome trafficking [37]. Mutations in this gene are mainly involved in autosomal recessive osteopetrosis (ARO)—or exceptionally in autosomal dominant osteopetrosis (ADO)—due to the inefficient bone resorption by nonfunctional osteoclasts [25, 38], and in this scenario, it is difficult to reconcile the mutation in heterozygosity in our patient with her severe low bone mass (LBM). Nevertheless, variants in TCIRG1 have been previously described in patients with LBM phenotype which experienced atypical femoral fractures [16]. Additionally, the p.(Ile721Asn) variant described here falls precisely in the proton pumping channel of the protein [37], and it is tempting to speculate that it might cause the channel to remain permanently open, acidifying the osteoclast lumen space and increasing bone resorption. Functional assays would be required to prove this hypothesis.

Another woman from the LZ group carried a missense mutation in ANO5. Mutations in this gene are responsible for gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia (GDD), a rare skeletal syndrome characterized by osteopetrosis-like sclerosis of the long bones and fibrous dysplasia-like cemento-osseous lesions of the jaw bone. People with this condition have reduced BMD which causes the bones to be unusually fragile. As a result, they typically experience multiple bone fractures during childhood, often from mild trauma or with no apparent cause [29]. The ANO5 gene encodes a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel involved in bone remodeling through the functional regulation of osteoclasts. Interestingly, most of the mutations in ANO5 leading to anoctamin-5 deficiency, representing loss-of-function, are causative of several forms of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMDL2L), while missense mutations in anoctamin-5 are causative of GDD which follows an autosomal dominant mode of transmission, reflecting a gain-of-function phenotype. Significantly, patients with LGMDL2L exhibit no pathogenic phenotype related to the bone, which, conversely, is evident in patients with GDD. Of note, the genetic variant reported in the present study, p.Cys804Ser, was previously described in compound heterozygosity in patients diagnosed with LGMD instead of GDD. Our patient did not display characteristic GDD features nor a clinical LGMD diagnosis, but had severe osteoporosis (spinal T-score < − 3.5 associated with a couple of postmenopausal fragility fractures). All things considered, it is unlikely that the variant explains this low bone mass phenotype. However, functional analyses and-or discovery of additional carrier patients would be necessary to get a definitive statement.

It is well known that alterations of the Wnt pathway have profound effects on bone properties, both increasing bone mass (HBM) or decreasing it (osteoporosis). LRP4 mediates SOST-dependent inhibition of bone formation by facilitating the inhibitory action of sclerostin on LRP5 [39]. It has been demonstrated that missense mutations in LRP4 that prevent its interaction with SOST, decrease the inhibitory function of sclerostin in bone formation, generating an HBM phenotype [27, 40]. On the other hand, a Lrp4-deficient mutant mice revealed shortened total femur length, reduced cortical femoral perimeter, and reduced total femur bone mineral content and BMD [41] suggesting that mutations in different domains of LRP4 may also have different effects on BMD [42]. According to HGMD, the variant found in our study was previously described as a secondary mutation in a patient with 46,XY disorder of sex development [27] and its putative contribution to the low bone density phenotype of our patient is presently unclear [26].

Finally, the variant found in the LMNA gene in the only woman with HBM might hardly explain her bone density phenotype. It is well known that mutations in this gene are often associated with Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (for which no bone density defects have been described) [43] or premature aging syndromes (which typically lead to skeletal deformities and/or osteoporosis through activation of non-canonical pathways of osteoclastogenesis) [31]. Most probably, other genetic variants are involved in the HBM phenotype of our patient and this variant is a secondary finding.

The main limitation of this study is that the gene panel was mostly focused on genes involved in low bone mass phenotypes rather than those associated with HBM since the primary aim was to describe rare variants related to OI enriched in women with LBM. Therefore, mutations involved in HBM are underrepresented in our HZ group as well as the problem of studying recessive inheritance linked to the X chromosome only in the sample of women. Another limitation is the number of samples whereby we could not obtain statistically significant differences in the burden test. An additional limitation is that the lumbar spine was selected as the phenotyping site instead of the total hip, the latter being more reproducible in terms of BMD measurement. Unfortunately, total hip BMD was not extensively measured in our center at the time of DXA acquisition. However, the mean age of our study population was 55 years, an age in which spinal artifacts are not so common as in older individuals. In any case, all DXA scans were reviewed by an expert clinician to investigate the presence of artifacts. Also, in the early postmenopausal period, alterations in BMD occur quicker at the lumbar spine than at the hip [44], making it an adequate phenotyping site for the purpose of our study. Finally, the family of the member carrying the COL1A2 variant was not willing to collaborate for a genetic study and we could not reach a conclusion about the implications of this variant in this family. One strength of this study is that using extreme-truncate selection designs could increase the power for detecting genetic variants associated with BMD. It is demonstrated by a previous GWAS performed by Duncan et al. (2011), where they replicated 21 of 26 known BMD-associated genes and additionally reported six new genes, most of them included in our gene panel [45]. Unlike the study by Duncan et al. which used a GWAS approach, we focused on sequencing a selected gene panel in order to identify rare genetic variants. Hence, both studies are complementary and contribute to deciphering the BMD genetics in postmenopausal women.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified rare genetic variants in genes previously described to be involved in bone monogenic phenotypes, in postmenopausal women split into two groups according to extreme BMD values and lumbar spine Z-scores. The variant identified in COL1A2 in a woman in the LZ group highlights the overlap between monogenic diseases such as osteogenesis imperfecta and complex diseases such as osteoporosis, which may share their genetic etiology. However, overall, we did not observe an enrichment of rare OI variants in the low BMD group, and except for the pathogenic variant in COL1A2, the variants could not be clearly associated with the bone density phenotype of these women, suggesting that there is little contribution of rare variants to postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Jaume Reig for the technical help.

Abbreviations

- BMD

Bone mineral density

- LBM

Low bone mass

- HBM

High bone mass

- OI

Osteogenesis imperfecta

- GDD

Gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia

- LGMDL2L

Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Funds for the study include grants PID2019-107188RB-C21 (Spanish MICINN) and CIBERER (U720). JDP was a recipient of the FI-SDUR predoctoral fellowship from Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR). The research was also supported by the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fragilidad y Envejecimiento Saludable (grant number CB16/10/00245) and European Union Fund. DO is recipient of a Miquel Servet grant from ISCIII.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Both the Bioethics Committee of Universitat de Barcelona and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Parc de Salut Mar have emitted a favorable bioethical statement regarding the present research. Written informed consents were obtained from all the participants.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

Patiño-Salazar, J.D. and Ovejero, D. contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.

Rabionet, R. and Garcia-Giralt, N.2 contributed equally to this work as co-last authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gregson CL, Armstrong DJ, Bowden J et al (2022) UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos 17:58. 10.1007/s11657-022-01061-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barron RL, Oster G, Grauer A et al (2020) Determinants of imminent fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 31:2103–2111. 10.1007/s00198-020-05294-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R et al (2019) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 30:3–44. 10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medina-Gomez C, Kemp JP, Estrada K et al (2012) Meta-analysis of genome-wide scans for total body BMD in children and adults reveals allelic heterogeneity and age-specific effects at the WNT16 locus. PLoS Genet 8:e1002718. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E et al (2012) Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat Genet 44:491–501. 10.1038/ng.2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trajanoska K, Morris JA, Oei L et al (2018) Assessment of the genetic and clinical determinants of fracture risk: genome wide association and mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 362:k3225. 10.1136/bmj.k3225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregson CL, Newell F, Leo PJ et al (2018) Genome-wide association study of extreme high bone mass: Contribution of common genetic variation to extreme BMD phenotypes and potential novel BMD-associated genes. Bone 114:62–71. 10.1016/j.bone.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JA, Kemp JP, Youlten SE et al (2019) An atlas of genetic influences on osteoporosis in humans and mice. Nat Genet 51:258–266. 10.1038/s41588-018-0302-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Gazzar A, Högler W (2021) Mechanisms of bone fragility: from osteogenesis imperfecta to secondary osteoporosis. Int J Mol Sci 22. 10.3390/ijms22020625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Forlino A, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, Marini JC (2011) New perspectives on osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Rev Endocrinol 7:540–557. 10.1038/nrendo.2011.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botor M, Fus-Kujawa A, Uroczynska M, et al (2021) Osteogenesis imperfecta: current and prospective therapies. Biomolecules 11.: 10.3390/biom11101493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Peris P, Monegal A, Mäkitie RE et al (2023) Osteoporosis related to WNT1 variants: a not infrequent cause of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 34:405–411. 10.1007/s00198-022-06609-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bustamante M, Nogués X, Mellibovsky L et al (2007) Polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 receptor gene are associated with bone mineral density and body mass index in Spanish postmenopausal women. Eur J Endocrinol 157:677–684. 10.1530/EJE-07-0389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bustamante M, Nogués X, Agueda L et al (2007) Promoter 2–1025 T/C polymorphism in the RUNX2 gene is associated with femoral neck bmd in Spanish postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 81:327–332. 10.1007/s00223-007-9069-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roca-Ayats N, Ng PY, Garcia-Giralt N et al (2018) Functional characterization of a GGPPS variant identified in atypical femoral fracture patients and delineation of the role of GGPPS in bone-relevant cell types. J Bone Miner Res 33:2091–2098. 10.1002/jbmr.3580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou W, van Rooij JG, van de Laarschot DM et al (2023) Prevalence of monogenic bone disorders in a Dutch cohort of atypical femur fracture patients. J Bone Miner Res 38:896–906. 10.1002/jbmr.4801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Giralt N, Roca-Ayats N, Abril JF et al (2022) Gene network of susceptibility to atypical femoral fractures related to bisphosphonate treatment. Genes 13. 10.3390/genes13010146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Jovanovic M, Guterman-Ram G, Marini JC (2022) Osteogenesis imperfecta: mechanisms and signaling pathways connecting classical and rare OI types. Endocr Rev 43:61–90. 10.1210/endrev/bnab017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panzaru M-C, Florea A, Caba L, Gorduza EV (2023) Classification of osteogenesis imperfecta: importance for prophylaxis and genetic counseling. World J Clin Cases 11:2604–2620. 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i12.2604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu H, Li C, Wu H et al (2023) Pathogenic mechanisms of osteogenesis imperfecta, evidence for classification. Orphanet J Rare Dis 18:234. 10.1186/s13023-023-02849-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald MM, Khoo WH, Ng PY et al (2021) Osteoclasts recycle via osteomorphs during RANKL-stimulated bone resorption. Cell 184:1330-1347.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Susak H, Serra-Saurina L, Demidov G et al (2021) Efficient and flexible Integration of variant characteristics in rare variant association studies using integrated nested Laplace approximation. PLoS Comput Biol 17:e1007784. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopanos C, Tsiolkas V, Kouris A et al (2019) VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics 35:1978–1980. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Paepe A, Nuytinck L, Raes M, Fryns JP (1997) Homozygosity by descent for a COL1A2 mutation in two sibs with severe osteogenesis imperfecta and mild clinical expression in the heterozygotes. Hum Genet 99:478–483. 10.1007/s004390050392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frattini A, Orchard PJ, Sobacchi C et al (2000) Defects in TCIRG1 subunit of the vacuolar proton pump are responsible for a subset of human autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. Nat Genet 25:343–346. 10.1038/77131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez de LaPiscina I, de Mingo C, Riedl S et al (2018) GATA4 variants in individuals with a 46, XY disorder of sex development (DSD) may or may not be associated with cardiac defects depending on second hits in other DSD genes. Front Endocrinol 9:142. 10.3389/fendo.2018.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leupin O, Piters E, Halleux C et al (2011) Bone overgrowth-associated mutations in the LRP4 gene impair sclerostin facilitator function. J Biol Chem 286:19489–19500. 10.1074/jbc.M110.190330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garbes L, Kim K, Rieß A et al (2015) Mutations in SEC24D, encoding a component of the COPII machinery, cause a syndromic form of osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet 96:432–439. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rolvien T, Koehne T, Kornak U et al (2017) A novel ANO5 mutation causing gnathodiaphyseal dysplasia with high bone turnover osteosclerosis. J Bone Miner Res 32:277–284. 10.1002/jbmr.2980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helbling-Leclerc A, Bonne G, Schwartz K (2002) Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Eur J Hum Genet 10:157–161. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alcorta-Sevillano N, Macías I, Rodríguez CI, Infante A (2020) Crucial role of lamin A/C in the migration and differentiation of MSCs in bone. Cells 9. 10.3390/cells9061330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Spotila LD, Constantinou CD, Sereda L et al (1991) Mutation in a gene for type I procollagen (COL1A2) in a woman with postmenopausal osteoporosis: evidence for phenotypic and genotypic overlap with mild osteogenesis imperfecta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:5423–5427. 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindahl K, Åström E, Rubin C-J et al (2015) Genetic epidemiology, prevalence, and genotype-phenotype correlations in the Swedish population with osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur J Hum Genet 23:1042–1050. 10.1038/ejhg.2015.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garibaldi N, Besio R, Dalgleish R et al (2022) Dissecting the phenotypic variability of osteogenesis imperfecta. Dis Model Mech 15. 10.1242/dmm.049398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Kang H, Aryal ACS, Marini JC (2017) Osteogenesis imperfecta: new genes reveal novel mechanisms in bone dysplasia. Transl Res 181:27–48. 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melville DB, Montero-Balaguer M, Levic DS et al (2011) The feelgood mutation in zebrafish dysregulates COPII-dependent secretion of select extracellular matrix proteins in skeletal morphogenesis. Dis Model Mech 4:763–776. 10.1242/dmm.007625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu A, Zirngibl RA, Manolson MF (2021) The V-ATPase 3 subunit: structure, function and therapeutic potential of an essential biomolecule in osteoclastic bone resorption. Int J Mol Sci 22. 10.3390/ijms22136934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Jodeh W, Katz AJ, Hart M et al (2024) Autosomal dominant osteopetrosis (ADO) caused by a missense variant in the TCIRG1 gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 109:1726–1732. 10.1210/clinem/dgae040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martínez-Gil N, Ugartondo N, Grinberg D, Balcells S (2022) Wnt pathway extracellular components and their essential roles in bone homeostasis. Genes 13. 10.3390/genes13010138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Hendrickx G, Boudin E, Mateiu L et al (2024) An additional Lrp4 high bone mass mutation mitigates the Sost-knockout phenotype in mice by increasing bone remodeling. Calcif Tissue Int 114:171–181. 10.1007/s00223-023-01158-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi HY, Dieckmann M, Herz J, Niemeier A (2009) Lrp4, a novel receptor for Dickkopf 1 and sclerostin, is expressed by osteoblasts and regulates bone growth and turnover in vivo. PLoS One 4:e7930. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fijalkowski I, Geets E, Steenackers E et al (2016) A novel domain-specific mutation in a sclerosteosis patient suggests a role of LRP4 as an anchor for sclerostin in human bone. J Bone Miner Res 31:874–881. 10.1002/jbmr.2782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muchir A, Worman HJ (2019) Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy: focal point nuclear envelope. Curr Opin Neurol 32:728–734. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finkelstein JS, Brockwell SE, Vinay M et al (2008) Bone mineral density changes during the menopause transition in a multiethnic cohort of women. JCEM 93:861–868. 10.1210/jc.2007-1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duncan EL, Danoy P, Kemp JP et al (2011) Genome-wide association study using extreme truncate selection identifies novel genes affecting bone mineral density and fracture risk. PLoS Genet 7:e1001372. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.