Abstract

While neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with surgical resection has improved the prognosis for patients with osteosarcoma, its impact on metastatic and recurrent cases remains limited. Immunotherapy is emerging as a promising alternative. However, the relationship between the phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages and the prognosis of osteosarcoma remains unclear. Differentially expressed gene during macrophage polarization were identified using the Monocle package. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis was conducted to select genes regulating macrophage polarization. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator algorithm and multivariate Cox regression were used to construct long-term survival predictive strategies. Multiple machine learning algorithms identified target genes for pan-cancer analysis. Lentiviral transfection created stable strains with target gene knockdown, and CCK-8 and transwell migration assays verified the target gene's effects. Western blot and flow cytometry assessed the impact of target genes on macrophage polarization. A total of 141 genes regulating macrophage polarization were identified, from which eight genes were selected to construct prognostic models. Significant differences between high-risk and low-risk groups were observed in immune cell activation, immune-related signaling pathways, and immune function. The prognostic model and target gene were validated to provide more precise immunotherapy options for osteosarcoma and other tumors. BNIP3 knockdown decreased osteosarcoma cell proliferation and migration and promoted macrophage polarization to the M2 phenotype. The constructed prognostic model offers precise immunotherapy regimens and valuable insights into mechanisms underlying current studies. Furthermore, BNIP3 may serve as a potential immunotherapeutic target for osteosarcoma and other tumors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10238-024-01530-w.

Keywords: Osteosarcoma, Macrophage polarization, Immunotherapy, Prognostic model, BNIP3, Tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS), the most prevalent invasive bone malignancy, poses a serious threat to the health of children and teenagers, typically developing in the epiphysis of long bones [1, 2]. Despite significant improvements in the five-year survival rate for osteosarcoma patients due to complete tumor resection and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the heterogeneity and chromosomal instability of OS cells continue to foster drug resistance [3, 4]. Additionally, OS progresses rapidly, with over 70% of patients presenting with micro-metastases at diagnosis, and the five-year survival rate drops to less than 30% once metastasis occurs [5, 6]. Furthermore, the efficacy of drugs in Phase II trials has been significantly lower than expected for patients with recurrent osteosarcoma [7]. Therefore, to enable early intervention and halt tumor progression, there is an urgent need for innovative biomarkers that can predict outcomes for osteosarcoma patients.

The tumor immune microenvironment (TIME), characterized by immune infiltration, immune modification, and immune escape involving both immunosuppressive and anti-tumor elements, plays a pivotal role in the tumorigenesis, progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance of osteosarcoma [8, 9]. Consequently, various immunotherapeutic approaches, including cytokine therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy, and chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy, have shown promising clinical efficacy [10–12]. Mifamurtide, which activates immune cells by binding to receptors both intracellularly and extracellularly, was the first immunotherapeutic drug approved for non-metastatic osteosarcoma [13]. However, in patients with relapsed or metastatic osteosarcoma, particularly those with postoperative recurrence or metastasis, current immunotherapies, such as PD1 and CTLA4 antibodies, have not yielded satisfactory clinical outcomes [14, 15].

A profound comprehension of the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) and the mechanisms of immunosuppression are paramount for advancing contemporary osteosarcoma therapy [16]. Due to the heterogeneous nature of immune cells, TIME represents a multifaceted and distinctive framework that profoundly impacts the efficacy of immunotherapy [17]. Within this milieu, the role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) is evolving, transitioning from anti-tumor effectors capable of tumor cell elimination and immune response induction to promoters of tumor progression and immunosuppression [18]. The genetic plasticity of macrophages enables differential responses to microenvironmental stimuli, such as lactate concentration, electrolyte levels, and energy availability, resulting in substantial genetic heterogeneity across various cancer types [19]. AMs can be selectively polarized to adopt either an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype or a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, contingent upon environmental cues [20]. For instance, the interaction between the "don't eat me" signal CD47 and its receptor SIRP-α on TAMs facilitates polarization toward the M2 phenotype, facilitating osteosarcoma cell evasion of phagocytosis while precipitating the demise of normal cells [21]. Consequently, prognostic models predicated on differentially expressed genes governing TAM polarization may afford more precise prognostications of immune responses and patient outcomes, albeit such models are currently absent.

In light of the clinical challenges presented by the high metastatic rate and limited response to immunotherapy, we advocate for the development of a prognostic model based on tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) polarization to enable the creation of effective prognostic indicators and therapeutic strategies for optimizing the clinical management of osteosarcoma [14, 22, 23].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as an indispensable tool in the realms of immunotherapy and tumor-targeted therapy, propelled by advancements in high-throughput sequencing technology [8, 24]. It has been extensively harnessed to unravel the intricate dynamics of the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) [25, 26]. Integration of data from various omics modalities, encompassing genetics, proteomics, and metabolomics, via Machine Learning (ML) predictive algorithms, offers profound insights into the complex systems biology of cancer [27, 28]. Pseudo-time analysis of macrophage phenotype transition has unveiled the underlying gene regulatory network and delineated genes implicated in macrophage polarization. Furthermore, leveraging lasso regression, multivariate analysis, and the cibesort algorithm, we devised a prognostic model adept at accurately predicting prognosis and immunotherapy response in osteosarcoma patients. In addition to this, LASSO helps in creating sparse models by selecting a subset of features, making it computationally efficient in high-dimensional settings. It is widely used for regularization in regression problems. On the other hand, Support Vector Machine Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE) iteratively ranks and eliminates features based on their importance to the SVM model, making it suitable for complex classification tasks, especially with nonlinear decision boundaries. Both methods aim to improve model interpretability, reduce overfitting, and enhance predictive accuracy [29]. Employing these machine learning methods, we identified molecular markers associated with diverse tumor immunotherapies and prognoses. Notably, BNIP3 (BCL2 interacting protein 3) emerged as a pivotal macrophage polarization gene correlated with poor prognosis in osteosarcoma. BNIP3 exhibited heightened expression in osteosarcoma cell lines, and its depletion attenuated osteosarcoma cell proliferation and migration. Our risk model underscored BNIP3's association with tumor-associated macrophage polarization and immunotherapy response in patients. Co-culture experiments demonstrated that BNIP3 knockdown fostered M1 macrophage polarization while impeding M2 macrophage polarization.

Materials and methods

Obtaining the data

We drew the flowchart of the study, and carried out the follow-up experimental exploration according to the flowchart (Fig. 1). In this investigation, we accessed eighty-eight osteosarcoma samples sourced from the Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) repository, complemented by an additional fifty-three samples retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (GSE21257) [30]. The expression matrices, quantified in transcripts per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (TPM), along with pertinent clinical metadata, were meticulously collected and processed in accordance with the established protocols of the respective public repositories. Moreover, scRNA-seq datasets elucidating macrophage polarization (GSE164498) and encompassing six osteosarcoma samples (GSE162454) were procured from GEO [31]. Furthermore, we obtained bulk RNA-seq expression matrices spanning 36 tumor types from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database.

Fig. 1.

The whole analysis process of this research

Pseudo-time analysis of scRNA seq data and identification of differential genes

The "Seurat" package was employed for the initial handling and preprocessing of scRNA-seq datasets GSE162454 and GSE164498 [32]. First, quality control on GSE162454 data was executed based on the following criteria, with non-compliant cells being discarded: (1) nFeature_RNA > 500 and nFeature_RNA < 4000; (2) percent.mt < 10%. Following this, the six samples were integrated using the "harmony" package to correct for batch effects. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to derive the top 20 principal components from the 2,000 most variable genes. This served as the foundation for t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), enabling unsupervised clustering and unbiased visualization of cell subpopulations in a two-dimensional space [33]. Differential gene analysis between clusters was performed with the FindAllMarkers tool, applying a threshold of |log2(fold change)|> 1 and an adjusted P-value < 0.01. Subsequent cell type annotation was conducted using the "SingleR" package [34]. The "commpath" package was utilized to examine the relationship between osteosarcoma-associated TAMs and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy [35]. The same protocol was applied to process GSE164498 data. Finally, the "monocle" package was employed to elucidate different states and identify differential genes involved in macrophage polarization [36].

Identification of hub genes-related macrophage polarization

After converting data from FPKM to TPM, the "cibesort" package was employed to delineate M1 and M2 macrophage populations in 88 patients from the TARGET database and 53 patients from the GEO database [37]. Subsequently, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was utilized to identify hub genes associated with macrophage polarization, based on the proportions of M1 and M2 macrophages within each osteosarcoma specimen [38]. The intersecting hub genes from the TARGET and GEO datasets were then subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses. The interconnections among these genes were visualized using the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) [39].

Construction of immune subtypes

Using the NMF package, the samples from GEO and TARGET were classified into distinct subtypes. The TIMER2.0 database (cistrome.org) was employed to analyze the composition of the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) in each sample [40]. This analysis examined the variations in immune cell composition, immunological microenvironment, and immune activity across different immune subtypes.

The establishment of risk model

By utilizing multivariate analysis and lasso regression, we developed a prognostic model based on genes regulating macrophage polarization [41]. The robustness of this prognostic model was further assessed through decision curve analysis (DCA), a nomogram, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Evaluation of tumor immune microenvironment

Gene sets for relevant enrichment analysis were downloaded from GSEA | MSigDB (gsea-msigdb.org). Molecular pathways associated with the risk score were identified using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and gene set variation analysis (GSVA). Additionally, the relationship between the risk score and the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) was examined.

Validation of this predictive model

The reliability of this prognostic signature was assessed in the GSE21257 dataset using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, a nomogram, and decision curve analysis (DCA). Finally, the "survcomp" package was utilized to compare the C-index of our established osteosarcoma prognostic model with that of other existing models [42–45].

Prediction of chemotherapy and target drug response

To evaluate the efficacy of drugs between different risk groups, the half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were calculated using the "oncopredict" package [46]. Additionally, the relationship between the risk score and the effectiveness of immunotherapy was assessed using the Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) algorithm (harvard.edu) [47].

Machine learning screening for characteristic genes

To delineate the target gene from the hub genes regulating macrophage polarization, we employed lasso regression and the support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) method [48]. Initially, using the "cibesort" package, we validated the relationship between the target gene and macrophages in the osteosarcoma microenvironment. Subsequently, we investigated the association of the target gene with immune function and cellular processes relevant to immunotherapy.

Cell culture

Cell lines including RAW264.7, THP-1, hFOB1.19, U2OS, HOS, 143B, MG63, and K7M2 were obtained from Wuhan Procell Life Technology Co., LTD. THP-1 and hFOB 1.19 cell lines were cultured in 1640 and DMED/F12k medium, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The remaining cell lines were cultured in high-glucose DMED medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Lentiviral transduction for stable cell lines

The lentiviruses packaging BNIP3 shRNA were purchased from Hanheng Biological Technology (Shanghai, China). Each of these sequences was cloned into the corresponding vector. Lentiviral packaging experiments were conducted using Lipofiter™, as manufacture described. BNIP3 knockdown plasmid was co-transfected with the packaging plasmids (pMD2G, psPAX2) into HEK293T cells. The lentivirus was collected 48 h and 72h after transfection. To generate stable BNIP3 knockdown cell lines, 143B, MG63 and K7M2 osteosarcoma cells were transduced with lentiviruses and then selected with puromycin (2 µg/ml, Biosharp) after 1 weeks of production. (RNA sequences: #sh1: 5’-GAACTGCACTTCAGCAATAAT-3’, #sh2: 5’-TCCAGCCTCGGTTTCTATTTA-3’, #sh3: 5’-CCCAAGGAGTTCCTCTTTAAA-3’, #shNC: 5’-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTAA-3’).

Western blotting

Total cellular proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Biosharp) supplemented with protease inhibitor. Following thorough lysis, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min to remove cell debris. The protein samples were denatured for 10 min at 100 °C and separated by SDS-PAGE. Subsequently, the separated proteins were transferred onto 0.45 µm PVDF membranes for 90 min at 4 °C. The membranes were then blocked in 5% BSA with TBST for 1 h at room temperature before being incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody. After washing three times with TBST, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies. The primary antibodies used for the western blotting assay were as follows: anti-BNIP3 (1:1000, Abcam), anti-BCL-2 (1:1000, Abcam), anti-Bax (1:1000, Abcam), anti-CD206 (1:1000, Protein-tech), anti-CD86 (1:1000, Protein-tech), anti-Arg-1 (1:1000, Abcam), and Tubulin (1:2000, Protein-tech).

Cell proliferation and migration assays

Cell proliferation activity was assessed via the CCK-8 assay. Osteosarcoma cells were seeded in 96-well plates, and after designated incubation intervals (6, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h), 10 µl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well. Following a 2-h incubation at 37 °C, absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Migration assays were conducted using a 24-well Transwell system equipped with polycarbonate filters (8 µm pores, Corning), without precoating of extracellular matrix (BD Biosciences). A suspension containing 20,000 osteosarcoma cells in serum-free DMEM was introduced into the upper chamber, while 500 µl of DMEM containing 10% FBS was placed in the lower chamber. After a 24-h incubation at 37 °C, migrated cells in the Transwell system were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and subsequently stained with 0.25% crystal violet for 30 min. Finally, migrated cells in the lower chamber were photographed and quantified.

Co-cultures system and flow cytometry

THP-1 cell lines treated with PMA (100 ng/ml, MultiSciences (Lianke)Biotech Co., Ltd) for 24h were co-cultured with 143B and MG63 osteosarcoma cells using a transwell culture system with 0.4μm well polyester membrane. Briefly, THP-1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a number of 5 × 105 cells/well, and osteosarcoma cells were seeded in transwell upper chambers at a number of 1 × 105 cells/well. After 48h of co-culture, the proteins of THP-1macrophages in the co-culture system were extracted according to the procedures described above, and the expression of CD206, CD86, and Arg-1 was detected. In the same way, after 48 h of co-culture, THP-1 macrophage cells were collected. CD206 and CD86 were resuspended in staining buffer (DPBS) containing 3% fetal bovine serum and analyzed by flow cytometry. Similarly, the co-culture system of K7M2 (1 × 105 cells/well) osteosarcoma cells and RAW264.7 (1 × 105 cells/well) macrophages was constructed, and the above treatment steps were carried out. The CD206 and CD86 fluorescence-conjugated antibodies were purchased from eBioscience at a dilution of 1:100.

Pan-cancer analysis of the target gene

The expression matrices of 36 solid tumors were obtained from TCGA. Target gene expression was extracted, and specimens were stratified into groups with high or low expression based on the median. Subsequently, leveraging the comprehensive immunogenomic analysis offered by the Cancer Immune Group Database (TCIA), we assessed the association between the target genes and the efficacy of immunotherapy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R 4.2.1. Nonparametric tests were employed to compare the two risk categories, with statistical significance set at a p-value of 0.05. Genuine associations were identified through Spearman Rank Correlation Analysis.

Result

Macrophage and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

Using the "Seurat" and "SingleR" packages, we characterized and categorized ten distinct cell types within the osteosarcoma tumor microenvironment, as observed in the GSE162454 cohort. It was evident that various cells within the tumor microenvironment exhibit close associations (Fig. S1a, b). Notably, macrophages demonstrated significant enrichment in the PD-1 and PD-L1 detection pathways, indicating their pivotal role in immune regulation (Fig. 2a). Moreover, macrophages displayed substantial correlations with other cell types (Fig. 2b). Additionally, we identified all receptor-ligand pairs present in the osteosarcoma microenvironment (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, we delineated the upstream and downstream pathways associated with macrophages, which have implications for immunotherapy (Fig. 2c, d). Lastly, we unveiled significantly distinct receptor-ligand pairs involved in various molecular pathways (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Macrophage and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. a The heatmap shows the molecular pathways involved in different cells in the osteosarcoma microenvironment. b The circus plot shows the interaction between macrophages and other cells. c 5 molecular pathways, "Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity," "Osteoclast differentiation," "Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation," "Th17 cell differentiation," and "PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer," upstream of macrophages and their receptor and ligand pairs were listed (p < 0.01). d 5 molecular pathways, "TNF signaling pathway," "Toll-like receptor signaling pathway," "JAK-STAT signaling pathway," "Apoptosis," "NF-kappa B signaling pathway," and "Necroptosis," downstream of macrophages and their receptor and ligand pairs were listed (p < 0.01). e Intercellular communication chains involved in molecular pathways upstream of macrophages

Identification of hub genes related to polarization of macrophages

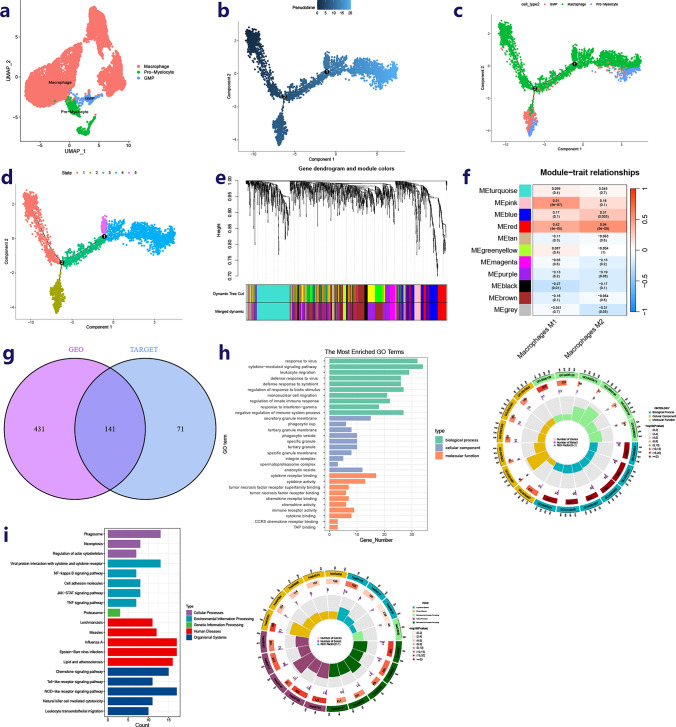

Utilizing the “Seurat” and “SingleR” packages, three cell types (Macrophage, GMP, Pro-Myelocyte) were identified and labeled based on the GSE164498 dataset (Fig. 3a). The process was classified into five distinct states using the monocle package (Fig. 3b–d). Through pseudo-time analysis, differentially expressed genes corresponding to various states were singled out, referred to as genes influencing macrophage polarization (Supplementary Table 2). The tumor immune microenvironment infiltration of osteosarcoma specimens from the GEO and TARGET datasets was assessed using the “CIBERSORT” package (Supplementary Table 3). In the TARGET-OS cohort, WGCNA was employed to identify hub genes regulating the polarization of macrophages toward the M1 or M2 phenotype from the macrophage differentiation-related genes (Fig. 3e, f). The same analysis was conducted on the GSE21257 cohort (Fig. S1c, d). The gene sets obtained from both databases were then intersected for further analysis (Fig. 3g).

Fig. 3.

Identification of hub genes-related polarization of macrophages. a Identification3 types of cells in the process of polarization of the macrophage. b–d Pseudo-time series analysis revealed the different states of macrophages in the process of driving the polarization of macrophages. eClustering tree of dissimilar macrophage polarization related genes based on the topological overlap, and specified merge module colors and original module colors in TARGET cohort. f Heat map of module–trait correlations in TARGET cohort. The hub genes (212) in the red modules presented the strongest association with macrophage M1 and macrophage M2. g The intersection of two hub gene sets related polarization of macrophages. h Bar plot and circus-plot show the main molecular pathways involved in hub genes based on GO functional enrichment analysis (p < 0.05). i Bar plot and circus-plot show the main molecular pathways involved in hub genes based on KEGG functional enrichment analysis (p < 0.05)

Exploring the function of hub genes associated with macrophage polarization

Subsequently, using the String database, interactions among 141 hub genes related to macrophage polarization were elucidated (Supplementary Table 4). A bar graph was also generated to illustrate genes encoding proteins that have ten or more interacting nodes (Fig. S1e). Functional enrichment analysis was conducted, revealing that these hub genes are predominantly involved in the cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, mononuclear cell migration, cytokine receptor binding, and tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily binding, which are crucial in the osteosarcoma TME, as indicated by GO enrichment analysis (Fig. 3h). Additionally, KEGG functional enrichment analysis identified gene sets associated with necrosis signaling pathways, protein interactions with cytokines and cytokine receptors, NF-kappa B receptor signaling pathway, cell adhesion molecules, JAK-STAT signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, toll-like receptor signaling pathway, natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and leukocyte trans-endothelial migration (Fig. 3i).

Construction of immune subtypes

The "SVA" package's combat function was utilized to eliminate batch effects in the expression matrix of osteosarcoma samples from various databases. Subsequently, 141 hub genes were employed to categorize all samples into two subtypes using the NMF program (Fig. 4a). Further comparisons revealed that samples from subtype C2 exhibited a more favorable tumor microenvironment composition than those from subtype C1 (Fig. S1f, g). Additionally, the immune cells and immune functions in group C2 were found to be superior to those in group C1 (Fig. 4b). Moreover, osteosarcoma samples in group C2 demonstrated higher activity in immune-related molecular processes (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Construction of immune subtypes and risk model a Dimensionality reduction matrix for rank = 2 was obtained by applying NMF clustering and the corresponding osteosarcoma samples were divided into C1 and C2. b Heat maps showing immune cell differences between groups C1 and C2 (p < 0.05). c Heat maps show differences in the relevant molecular pathways between C1 and C2 (p < 0.05). d, e 8 hub genes regulating the polarization of macrophages were screened by lasso regression and multivariate analysis. f Multivariate analysis reveals the relationship between clinical features and risk-score and prognosis. g–i The KM curve and time-dependent ROC curve in all TARGET queue, train queue and test queue. j Nomogram for 1, 3, and 5-year overall survival of specimens combined risk model with clinical features. k Calibration curves compare the model prediction probability with the observed probability, the dotted line refers to the ideal nomogram. l The cumulative risk curve based on nomogram. Clearly, the low-risk group had a better prognosis

The establishment of the risk model

Osteosarcoma specimens from the TARGET database were utilized to create a predictive signature, with specimens from the GEO database serving as external validation data to assess the model's reliability. The osteosarcoma specimens from the TARGET database were divided into a training cohort and a test cohort in a 7:3 ratio. Using multivariate analysis and lasso regression, a predictive model was developed based on the expression matrices of 141 hub genes and patient prognosis in the training cohort (Fig. 4d, e). Finally, eight genes (SCO2, YWHAN, GPR82, RNASET2, BRI3, IL2RG, BNIP3, PML) were selected to construct the prognostic model. The risk-score for each sample was calculated using the correlation coefficient of these signature genes.

Next, the risk-score and tumor metastasis were identified as significant risk factors for patients (Fig. 4f). Based on the median risk-score in the training cohort, subjects in the TARGET cohort, training cohort, and test cohort were categorized as either high-risk or low-risk. Patients in the low-risk category demonstrated higher overall survival rates, and the model's strong predictive power was confirmed by the ROC curve (Fig. 4g–i). A nomogram was constructed by integrating patient age, gender, immune subtype, and risk characteristics (Fig. 4j). The calibration plot illustrated the nomogram's reliability (Fig. 4k). Nomogram risk scores for each sample were calculated, and the median nomogram risk score was used to classify samples into high and low-risk subgroups. The cumulative risk curve indicated that cumulative hazards increase over time for both groups, with the high nomogram risk group exhibiting a higher cumulative hazard (Fig. 4l). Additionally, immune subtypes and tumor metastasis were significantly correlated with the risk-score (Fig. 4m). The DCA curve further demonstrated the prognostic predictive accuracy of both the risk model and the nomogram risk model (Fig. S2a, b).

Validation of the prognostic model

After determining the risk-score of each sample, the GSE21257 cohort was utilized as external validation data for the prognostic model. The Kaplan–Meier curve subsequently revealed that patients with a lower risk-score exhibited a more favorable prognosis (Fig. 5a). The time-dependent ROC curve further illustrated the accuracy of this prognostic signature in the GSE21257 cohort (Fig. 5a). By integrating the age, sex, immune subtype, and risk-score of all osteosarcoma patients in the GEO data, a nomogram was constructed (Fig. 5b). The calibration curve was generated to demonstrate the reliability of the nomogram (Fig. 5c). In the cumulative hazard curve, the high-risk group exhibited a notably higher cumulative hazard (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Validation the prognostic risk model and association analysis between risk-score and TIME a The KM curve and time-dependent ROC curve in GSE21257 cohort. b Nomogram Prediction of 1, 3, and 5year overall survival of osteosarcoma patients from GSE21257 cohort. c Validation of the nomogram. d The cumulative risk curve based on nomogram. e Concordant index of different prognostic models revealing that compared with other prognostic models of osteosarcoma, this model has a more reliable predictive ability. f GSEA in the high-risk group and the low-risk group. g Heat map of correlation between key signaling pathways and risk scores (p < 0.05). h Coefficient plot between immune cells and risk score. i Bar-plot compares the clinical outcomes of high-risk and low-risk groups receiving immunotherapy. j Correlation chart between drugs sensitivity and risk scores (p < 0.01). k Identification10 types of cells in TME through analysis of single-cell sequencing data from osteosarcoma samples. l Bubble plot of prognostic gene expression in different

ROC curves of clinical characteristics, immune subtypes, and risk scores affirmed the reliability of the risk model in predicting prognosis (Fig. S2c). Simultaneously, gender, age, metastasis, and immune subtype demonstrated no influence on the accuracy of the risk model in predicting outcomes (Fig. S2d–g). The prognostic model based on macrophage polarization exhibited a higher concordance index (C-index) compared to other prognostic models of osteosarcoma based on cuproptosis, immunogenic cell death, glycolysis, and aging (Fig. 5e). Restricted mean survival time (RMS time) for the different models was subsequently presented, indicating higher accuracy of prognostic features based on macrophage polarization (Fig. S3a).

Correlation among risk scores, TIME, and immunotherapy response

Following the GSEA findings, the low-risk group exhibited associations with antigen processing and presentation, lysosome, and diseases related to autoimmunity, while the high-risk group primarily showed involvement in focal adhesion, calcium signaling pathway, leukocyte trans-endothelial migration, and FC epsilon RI signaling pathway (Fig. 5f). A strong negative correlation between the risk-score and immune-related signaling pathways was identified (Fig. 5g). Subsequently, the CIBERSORT algorithm depicted the immune cell composition of each specimen and the interrelation between immune cells (Fig. 5h). Importantly, most immune cells in the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME), including M1 and M2 macrophages, exhibited an inverse relationship with the risk-score, whereas M0 macrophages showed a positive correlation. Additionally, samples in the low-risk category tended to exhibit a predominance of stronger immune function (Fig. S3b). The association between the risk-score and immune checkpoint-related genes revealed an adverse correlation with those genes (Fig. S3c). Consequently, it should come as no surprise that the high-risk group exhibited a poorer response to immunotherapy compared to the low-risk group (Fig. 5i).

Furthermore, we predicted the sensitivity of various targeted medications, observing that samples from the low-risk category typically displayed heightened drug sensitivity (Fig. 5j). Leveraging the "seurate" and "singleR" packages, we delineated and classified ten cell types within the tumor microenvironment using data from the GSE162454 cohort (Fig. 5k). Subsequently, the scatter plot and bubble plot unveiled distinct expressions of prognostic genes within the TME (Fig. 5l).

Machine learning screening for characteristic genes

Various Machine Learning (ML) algorithms were employed to identify superior molecular markers for treatment guidance. Among 72 ML algorithms integrated, the combined survival-SVM and lasso regressions demonstrated the highest c-index value (Fig. 6a). Subsequently, the SVM method pinpointed nine crucial genes with optimal accuracy and minimal error rates (Fig. 6b). These nine essential genes (Supplementary Table 5) were further refined via lasso regression (Fig. 6c). Upon intersection with the prognostic model gene set, the final target gene, BNIP3, was identified (Fig. 6d). Elevated expression of BNIP3 in the high-risk group suggested its potential as a subpar prognostic indicator (Fig. 6e). Notably, BNIP3 displayed an inverse correlation with osteosarcoma prognosis based on K-M curves (Fig. S3d). Furthermore, the classification of osteosarcoma samples according to BNIP3 expression exhibited heightened accuracy (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6.

Machine learning screening for characteristic genes a The C-index values of key genes were screened by different machine learning methods. b Estimate generalization error of SVM. c Intersection of lasso regression and SVM. d The intersection of multiple machine learning algorithms. Then the final target gene BNIP3 was obtained. e Box plot is used to compare the expression of BNIP3 in high-risk and low-risk groups. f The time-dependent ROC of predicting the risk grouping of patients based on BNIP3 expression. g Background expression of BNIP3 in different osteosarcoma cell lines and osteoblast cell line. h Western blotting verified the construction of BNIP3 knockdown models in different cell lines

BNIP3 promotes osteosarcoma growth and metastasis

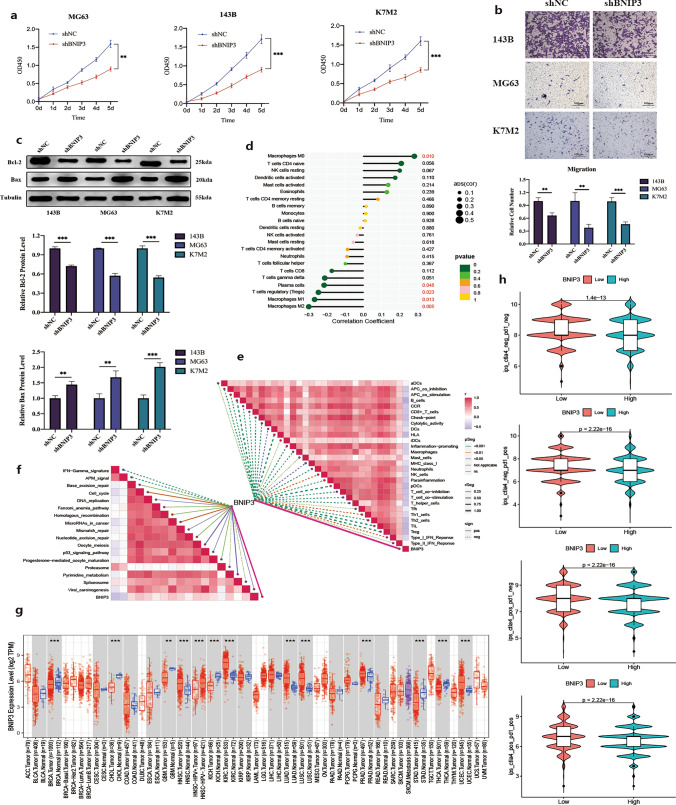

Western blotting analysis revealed up-regulation of BNIP3 in various human and murine osteosarcoma cell lines (Fig. 6g). Specifically, compared to hOFB1.19, tumor cell lines exhibited notably higher BNIP3 expression levels, particularly the 143B and HOS cell lines. We selected the 143B cell line with high BNIP3 expression, MG63 cell line with moderate BNIP3 expression, and the murine K7M2 cell line for further experimentation. To elucidate the functional significance of BNIP3 in osteosarcoma malignant progression, we successfully established a stable BNIP3 knockdown model in 143B, MG63, and K7M2 cells using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences (Fig. 6h). Our findings demonstrated that BNIP3 knockdown significantly inhibited both cell proliferation and migration in 143B, MG63, and K7M2 cells (Fig. 7a, b). Moreover, after BNIP3 knockdown, the MG63, 143B, and K7M2 cell lines exhibited increased susceptibility to apoptosis (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

Relationship between BNIP3 and tumor immune microenvironment and pan-cancer analysis a, b Cell proliferation, and migration of BNIP3 knockdown 143B, MG63 and K7M2 cells. c Western blot analysis of BAX and BCL2 after BNIP3 knockdown. d Association of BNIP3 with immune cells in tumor microenvironment. e Correlations between BNIP3 and the enrichment scores of immunotherapy-predicted pathways. f Relationship between BNIP3 and immune function in osteosarcoma microenvironment. g Boxplot showing the difference of BNIP3 expression in tumor tissue and para-cancer tissue. h Violin plots showing the expression of BNIP3 with the therapeutic effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors. (*p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.001)

Relationship between BNIP3 and tumor immune microenvironment and pan-cancer analysis

To delve deeper into the potential role of BNIP3 in the immune microenvironment, we conducted a comprehensive correlation analysis between BNIP3 and 29 reported immune-related gene sets, encompassing various immune cell types and functions. Intriguingly, within the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) of osteosarcoma, BNIP3 exhibited a direct correlation with macrophages M0 and an inverse correlation with macrophages M1 and M2 (Fig. 7d). Furthermore, BNIP3 demonstrated a positive association with diverse molecular pathways implicated in immunotherapy (Fig. 7e). However, BNIP3 showed a negative correlation with multiple immune functions within the osteosarcoma tumor microenvironment, suggesting its potential relevance to immunotherapy efficacy (Fig. 7f).

Distinct levels of BNIP3 expression were observed in different tumor tissues and adjacent tissues from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (Fig. 7g). Additionally, a significant difference in BNIP3 expression between tumor tissue and adjacent tissue was evident (Supplementary Table 6). Subsequently, based on the median expression of BNIP3 in all tumor tissues, tumor samples from TCGA were stratified into high or low expression groups. Notably, PD1 and CTLA4 immune checkpoint inhibitors, either alone or in combination, demonstrated enhanced clinical efficacy in the low BNIP3 expression group (Fig. 7h).

BNIP3 mediates M1/2 polarization of macrophages

Hence, to further elucidate the relationship between BNIP3 and macrophage polarization, we established a co-culture system comprising osteosarcoma cells and macrophages. Western blotting revealed that the expression of the M1-type macrophage marker CD86 in THP-1 cells and RAW264.7 cells did not show significant changes. However, the expression of the M2-type macrophage marker Arg-1 in THP-1 cells was notably increased compared to the control group, and this elevation was not observed after BNIP3 knockdown. Conversely, the expression of the M2-type macrophage marker CD206 showed no significant change, possibly due to its low expression in THP-1 cells (Fig. 8a, b). In RAW264.7 cells, both Arg-1 and CD206 expressions were significantly elevated compared to the control group, although they did not increase significantly after BNIP3 knockdown (Fig. 8g). Flow cytometry analysis indicated a substantial increase in the proportion of M2 macrophages in both THP-1 and RAW264.7 cells compared to controls, which was attenuated by BNIP3 knockdown (Fig. 8c–f, h, i).

Fig. 8.

BNIP3 induces M2 polarization of macrophages a, b Western blotting of macrophage markers of THP-1 cells receiving different treatments. c, d Representative flow cytometer data of M2 polarization when THP-1 was co-cultured with 143B cells. e, f Representative flow cytometer data of M2 polarization when THP-1 was co-cultured with MG63 cells. g Western blotting of macrophage markers of RAW264.7 cells receiving different treatments. f Representative flow cytometer data of M2 polarization when RAW264.7 was co-cultured with K7M2 cells. (*p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.001)

Discussion

Around 70% of osteosarcoma patients harbor micro-metastases upon diagnosis, indicating an advanced disease stage [5, 49]. While a subset of patients has shown benefits from neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with surgical resection, those with recurrent or metastatic osteosarcoma respond less favorably [50]. Despite efforts, immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), has not yielded significant clinical outcomes [22, 51]. It is hypothesized that the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways in TAM may upregulate inhibitory receptors and their ligands, thus dampening immune responses [52]. Notably, TAMs might be suppressed via PD-L1-mediated mechanisms, as evidenced by TAM-specific PD-L1 blockade prompting macrophage phenotypic shifts, suggesting an integral role of TAMs in osteosarcoma immunotherapy [53]. Nonetheless, few studies have explored how macrophage phenotypic alterations influence drug resistance and osteosarcoma prognosis.

Analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data from GSE162454 has revealed that macrophages exert a direct influence on immune-related molecular pathways, including the TNF signaling pathway, toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway, apoptosis, and necroptosis, as well as upstream molecular pathways such as PD-L1 expression and the PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer. This suggests a potential link between changes in macrophage phenotype within the TME and ICI. Subsequent analysis of data from GSE164498 identified different states in the process of macrophage polarization, along with corresponding genes exhibiting differential expression.

In subsequent analysis, genes governing macrophage polarization were identified from these differentially expressed genes through WGCN. These genes appeared to play crucial roles in immune cell differentiation and migration, signaling pathways related to immunomodulation, and programmed cell death (PCD), as evidenced by Gene Ontology (GO) an KEGG enrichment studies. Subsequently, using these genes, osteosarcoma samples from the TARGET and GSE21257 datasets were classified into immune-activated and immunosuppressive types. Concurrently, eight hub genes were selected through lasso regression and multivariate analysis to construct a predictive model and ascertain risk scores for all subjects. Based on the median risk score in the training set, all osteosarcoma specimens were stratified into two distinct groups. The K-M survival curve, ROC curve, nomogram, decision curve analysis DCA curve, and c-index were employed to validate the actual reliability of the prognostic model.

Subtle alterations in the microenvironmental cues affecting macrophages can lead to diverse adaptations, underscoring the pivotal role of TAMs in orchestrating TME [54]. GSEA and GSVA outcomes indicated that samples with lower risk propensity tend to engage in multiple immune-related processes and signaling pathways. The inverse correlation between the majority of immune cells in the TME and the risk score suggests that samples with lower risk exhibit a more robust immune response to the immunological microenvironment of osteosarcoma, contributing to their favorable prognosis. Moreover, individuals in the two distinct risk groups also exhibited varying IC50s for different therapeutic drugs and distinct responses to immunotherapy, highlighting the potential of this risk model to tailor more personalized therapy for osteosarcoma patients.

Moreover, amidst various machine learning algorithms, the SVM coupled with lasso regression, boasting the highest C-index value, was meticulously chosen. This amalgamation, intertwined with the established prognostic model, ultimately pinpointed BNIP3 as the final target gene. Notably, BNIP3 showcased substantial overexpression within the high-risk group. Following this revelation, comparative analyses against osteoblasts unveiled BNIP3's heightened expression across multiple osteosarcoma cell lines, including MG63, 143B, and K7M2. Leveraging these insights, we successfully constructed stable knockdown models of BNIP3 within 143B, MG63, and K7M2 cell lines. Intriguingly, BNIP3 knockdown yielded palpable reductions in osteosarcoma cell proliferation and migration, while also curbing their anti-apoptotic tendencies.

BNIP3 (BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa interacting protein 3) is an important mitochondrial-localized BH3-only protein involved in various cellular processes such as apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy. BNIP3 interacts with BCL-2 family proteins to induce mitochondrial membrane potential loss, activating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and inhibiting tumor cell survival [55]. BNIP3 also regulates autophagy to promote tumor cell survival, especially in hypoxic environments [56]. By interacting with autophagy-related proteins like LC3, BNIP3 enhances autophagy, helping tumor cells cope with metabolic stress and promoting tumor progression. Broadly speaking, BNIP3 plays a dual role in osteosarcoma progression, both promoting apoptosis to inhibit tumor cell proliferation and facilitating tumor cell survival via autophagy and other pathways to help the tumor adapt to environmental stress, thus supporting tumor growth and metastasis. In the immune response, BNIP3 regulates immune cell survival and function, potentially playing a key role in tumor immune evasion [57].

Subsequently, we delved deeper into the interplay between BNIP3 and the tumor immune microenvironment. Remarkably, BNIP3 exhibited a positive correlation with macrophage M0, while conversely displaying negative associations with macrophages M1 and M2 within the tumor immune microenvironment. This intricate relationship underscores BNIP3's multifaceted role in shaping the immune landscape of tumors. Moreover, an expansive pan-cancer analysis unveiled varied expression patterns of BNIP3 across diverse cancers and adjacent tissues. Crucially, these findings underscored BNIP3's pivotal role in modulating responses to immunotherapy, hinting at its potential as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment. To delve deeper into the intricate interplay between BNIP3 and macrophages, we established a sophisticated co-culture model comprising osteosarcoma cells and macrophages. Intriguingly, our experiments revealed that osteosarcoma cells possess the capability to induce M2 polarization of macrophages, a process that can be effectively inhibited through BNIP3 knockdown. These findings shed new light on the intricate crosstalk between BNIP3 and macrophages within the tumor microenvironment, offering novel insights into potential therapeutic strategies for cancer treatment.

The notable contributions of this study lie in its discovery of the close association between macrophages and ICI treatment, as revealed by scRNA-se, and the identification of differentially DEGs implicated in macrophage polarization. Subsequently, leveraging lasso and multivariate analysis, we devised a prognostic model encompassing eight genes, validating its clinical robustness. Furthermore, by delineating macrophage polarization-related genes, osteosarcoma specimens were stratified into immune-activated and immunosuppressive subtypes, thereby offering tailored immunotherapeutic strategies. Notably, employing SV, we pinpointed a target gene closely associated with macrophage polarization and ICI responsiveness. Subsequent experiments underscored the inhibitory effect of BNIP3 knockdown on osteosarcoma cell proliferation and migration, while also attenuating osteosarcoma-induced macrophage M2 polarization. Despite the promising predictive capacity of the prognostic signature predicated on macrophage polarization and its potential for personalized treatment modalities in osteosarcoma patients, the study underscores the imperative for broader cohort studies owing to the limited sample size available.

At last, in our study, we recognize the potential biases inherent in using publicly available databases, including patient selection bias and sequencing variability. Public datasets may not fully represent the broader osteosarcoma patient population, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings to certain subgroups. Furthermore, differences in sequencing platforms, depth, and analysis methods can introduce variability in gene expression or mutation profiling, which could affect the robustness of biomarkers identified. To mitigate these biases, future studies should consider using more diverse patient cohorts and multiple datasets to improve representativeness. Additionally, standardizing sequencing protocols and incorporating cross-platform validation could reduce the impact of sequencing variability.

Conclusion

This study offers a comprehensive analysis of 141 hub genes related to macrophage polarization, culminating in the construction of a risk model. The derived risk-score effectively predicts patient outcomes and immunotherapy efficacy. Additionally, BNIP3 emerges as a key player in macrophage polarization and immunotherapy across various tumors. Knockdown of BNIP3 inhibits osteosarcoma cell proliferation, migration, and their ability to induce macrophage M2 polarization. Overall, these findings enhance our understanding of macrophage polarization's regulatory role in TM, paving the way for personalized immunotherapy in osteosarcoma and beyond.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Central Laboratory of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University for the guidance of the experimental site and experimental technology.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the work presented in this paper. S.J.C. and D.W. were responsible for the design and methodology of the article. Z.C.T., Z.X.L. and D.W. completed the data collection. J.Z. and Y.M.D finished preparing the data. D.W. and S.J.C completed data analysis and writing. G.W.W, J.L.M and J.S.L are responsible for data management and article proofreading.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82373046、82172594) and the Wisdom Accumulation and Talent Cultivation Project of the Third XiangYa hospital of Central South University (YX202001), Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2022SK2033).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jin Zeng and Dong Wang have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Lee JA, Lim J, Jin HY, Park M, Park HJ, Park JW, Kim JH, Kang HG, Won YJ. Osteosarcoma in adolescents and young adults. Cells. 2021;10:2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer. 2009;115:1531–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson ME. Update on survival in osteosarcoma. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47:283–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S, Sun W, Wang H, Zuo D, Hua Y, Cai Z. Research progress on the multidrug resistance mechanisms of osteosarcoma chemotherapy and reversal. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:1329–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almeida SFF, Fonseca A, Sereno J, Ferreira HRS, Lapo-Pais M, Martins-Marques T, Rodrigues T, Oliveira RC, Miranda C, Almeida LP, Girao H, Falcao A, Abrunhosa AJ, Gomes CM. Osteosarcoma-derived exosomes as potential pet imaging nanocarriers for lung metastasis. Small. 2022;18:e2203999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smeland S, Bielack SS, Whelan J, Bernstein M, Hogendoorn P, Krailo MD, Gorlick R, Janeway KA, Ingleby FC, Anninga J, Antal I, Arndt C, Brown KLB, Butterfass-Bahloul T, Calaminus G, Capra M, Dhooge C, Eriksson M, Flanagan AM, Friedel G, Gebhardt MC, Gelderblom H, Goldsby R, Grier HE, Grimer R, Hawkins DS, Hecker-Nolting S, Sundby Hall K, Isakoff MS, Jovic G, Kuhne T, Kager L, von Kalle T, Kabickova E, Lang S, Lau CC, Leavey PJ, Lessnick SL, Mascarenhas L, Mayer-Steinacker R, Meyers PA, Nagarajan R, Randall RL, Reichardt P, Renard M, Rechnitzer C, Schwartz CL, Strauss S, Teot L, Timmermann B, Sydes MR, Marina N. Survival and prognosis with osteosarcoma: outcomes in more than 2000 patients in the EURAMOS-1 (European and American osteosarcoma study) cohort. Eur J Cancer. 2019;109:36–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omer N, Le Deley MC, Piperno-Neumann S, Marec-Berard P, Italiano A, Corradini N, Bellera C, Brugieres L, Gaspar N. Phase-II trials in osteosarcoma recurrences: a systematic review of past experience. Eur J Cancer. 2017;75:98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Zhang Z. The history and advances in cancer immunotherapy: understanding the characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:807–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez S, Tabernacki T, Kobyra J, Roberts P, Chiappinelli KB. Combining epigenetic and immune therapy to overcome cancer resistance. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;65:99–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong M, Clubb JD, Chen YY. Engineering CAR-T cells for next-generation cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:473–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johal S, Ralston S, Knight C. Mifamurtide for high-grade, resectable, nonmetastatic osteosarcoma following surgical resection: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2013;16:1123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill J, Gorlick R. Advancing therapy for osteosarcoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:609–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen Y, Tang F, Tu C, Hornicek F, Duan Z, Min L. Immune checkpoints in osteosarcoma: recent advances and therapeutic potential. Cancer Lett. 2022;547:215887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Y, Yang D, Yang Q, Lv X, Huang W, Zhou Z, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Yuan T, Ding X, Tang L, Zhang J, Yin J, Huang Y, Yu W, Wang Y, Zhou C, Su Y, He A, Sun Y, Shen Z, Qian B, Meng W, Fei J, Yao Y, Pan X, Chen P, Hu H. Single-cell RNA landscape of intratumoral heterogeneity and immunosuppressive microenvironment in advanced osteosarcoma. Nat Commun. 2020;11:6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitt JM, Marabelle A, Eggermont A, Soria JC, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1482–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiang X, Wang J, Lu D, Xu X. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages to synergize tumor immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christofides A, Strauss L, Yeo A, Cao C, Charest A, Boussiotis VA. The complex role of tumor-infiltrating macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:1148–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrissey MA, Kern N, Vale RD. CD47 ligation repositions the inhibitory receptor SIRPA to suppress integrin activation and phagocytosis. Immunity. 2020;53:290–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen C, Xie L, Ren T, Huang Y, Xu J, Guo W. Immunotherapy for osteosarcoma: fundamental mechanism, rationale, and recent breakthroughs. Cancer Lett. 2021;500:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheng G, Gao Y, Yang Y, Wu H. Osteosarcoma and metastasis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:780264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Wang ZX, Chen YX, Wu HX, Yin L, Zhao Q, Luo HY, Zeng ZL, Qiu MZ, Xu RH. Integrated analysis of single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing data reveals a pan-cancer stemness signature predicting immunotherapy response. Genome Med. 2022;14:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Miao J, Wang S, Shen R, Zhang S, Tian Y, Li M, Zhu D, Yao A, Bao W, Zhang Q, Tang X, Wang X, Li J. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the genesis and heterogeneity of tumor microenvironment in pancreatic undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant-cells. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee HW, Chung W, Lee HO, Jeong DE, Jo A, Lim JE, Hong JH, Nam DH, Jeong BC, Park SH, Joo KM, Park WY. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the tumor microenvironment and facilitates strategic choices to circumvent treatment failure in a chemorefractory bladder cancer patient. Genome Med. 2020;12:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reel PS, Reel S, Pearson E, Trucco E, Jefferson E. Using machine learning approaches for multi-omics data analysis: a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2021;49:107739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee D, Park Y, Kim S. Towards multi-omics characterization of tumor heterogeneity: a comprehensive review of statistical and machine learning approaches. Brief Bioinform. 2021. 10.1093/bib/bbaa188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou B, Zhou N, Liu Y, Dong E, Peng L, Wang Y, Yang L, Suo H, Tao J. Identification and validation of CCR5 linking keloid with atopic dermatitis through comprehensive bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Front Immunol. 2024. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1309992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buddingh EP, Kuijjer ML, Duim RA, Burger H, Agelopoulos K, Myklebost O, Serra M, Mertens F, Hogendoorn PC, Lankester AC, Cleton-Jansen AM. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages are associated with metastasis suppression in high-grade osteosarcoma: a rationale for treatment with macrophage activating agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2110–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Feng W, Dai Y, Bao M, Yuan Z, He M, Qin Z, Liao S, He J, Huang Q, Yu Z, Zeng Y, Guo B, Huang R, Yang R, Jiang Y, Liao J, Xiao Z, Zhan X, Lin C, Xu J, Ye Y, Ma J, Wei Q, Mo Z. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals the complexity of the tumor microenvironment of treatment-naive osteosarcoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:709210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangiola S, Doyle MA, Papenfuss AT. Interfacing seurat with the R tidy universe. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:4100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Vinck M. Improved visualization of high-dimensional data using the distance-of-distance transformation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2022;18:e1010764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Zhou Z, Xie J, Qi S, Tang J. Integration of single-cell and bulk transcriptomics reveals immune-related signatures in keloid. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu H, Ping J, Zhou G, Zhao Z, Gao W, Jiang Y, Quan C, Lu Y, Zhou G. CommPath: an R package for inference and analysis of pathway-mediated cell-cell communication chain from single-cell transcriptomics. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:5978–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reid JE, Wernisch L. Pseudotime estimation: deconfounding single cell time series. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2973–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang X, Ke K, Jin W, Zhu Q, Zhu Q, Mei R, Zhang R, Yu S, Shou L, Sun X, Feng J, Duan T, Mou Y, Xie T, Wu Q, Sui X. Identification of genes related to 5-fluorouracil based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:887048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinfo. 2008;9:559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, Lyon D, Kirsch R, Pyysalo S, Doncheva NT, Legeay M, Fang T, Bork P, Jensen LJ, von Mering C. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D605–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER20 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:W509–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Z, Sillanpaa MJ. Overview of LASSO-related penalized regression methods for quantitative trait mapping and genomic selection. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:419–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lv Y, Wu L, Jian H, Zhang C, Lou Y, Kang Y, Hou M, Li Z, Li X, Sun B, Zhou H. Identification and characterization of aging/senescence-induced genes in osteosarcoma and predicting clinical prognosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:997765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian K, Qi W, Yan Q, Lv M, Song D. Signature constructed by glycolysis-immune-related genes can predict the prognosis of osteosarcoma patients. Invest New Drugs. 2022;40:818–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J, Zhang J, Na S, Wang Z, Li H, Su Y, Ji L, Tang X, Yang J, Xu L. Integration of single-cell RNA sequencing and bulk RNA sequencing to reveal an immunogenic cell death-related 5-gene panel as a prognostic model for osteosarcoma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:994034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang M, Zheng H, Xu K, Yuan Q, Aihaiti Y, Cai Y, Xu P. A novel signature to guide osteosarcoma prognosis and immune microenvironment: cuproptosis-related lncRNA. Front Immunol. 2022;13:919231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maeser D, Gruener RF, Huang RS. oncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief Bioinform. 2021. 10.1093/bib/bbab260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, Fu J, Sahu A, Hu X, Li Z, Traugh N, Bu X, Li B, Liu J, Freeman GJ, Brown MA, Wucherpfennig KW, Liu XS. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med. 2018;24:1550–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou X, Tuck DP. MSVM-RFE: extensions of SVM-RFE for multiclass gene selection on DNA microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kager L, Zoubek A, Pötschger U, Kastner U, Flege S, Kempf-Bielack B, Branscheid D, Kotz R, Salzer-Kuntschik M, Winkelmann W, Jundt G, Kabisch H, Reichardt P, Jürgens H, Gadner H, Bielack SS. Primary metastatic osteosarcoma: presentation and outcome of patients treated on neoadjuvant cooperative osteosarcoma study group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meltzer PS, Helman LJ. New horizons in the treatment of osteosarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2066–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lascelles BD, Dernell WS, Correa MT, Lafferty M, Devitt CM, Kuntz CA, Straw RC, Withrow SJ. Improved survival associated with postoperative wound infection in dogs treated with limb-salvage surgery for osteosarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:1073–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao J, Liang Y, Wang L. Shaping polarization of tumor-associated macrophages in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:888713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang Q, Liang X, Ren T, Huang Y, Zhang H, Yu Y, Chen C, Wang W, Niu J, Lou J, Guo W. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in osteosarcoma progression - therapeutic implications. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2021;44:525–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mosser DM, Hamidzadeh K, Goncalves R. Macrophages and the maintenance of homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:579–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng J, Cao Y, Yang J, Jiang H. UBXD8 mediates mitochondria-associated degradation to restrain apoptosis and mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2022;23:e54859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang J, Ney PA. Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:939–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shuwen H, Yinhang W, Jing Z, Qiang Y, Yizhen J, Quan Q, Yin J, Jiang L, Xi Y. Cholesterol induction in CD8+ T cell exhaustion in colorectal cancer via the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contact sites. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72:4441–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.