Abstract

Antimony zinc borate glasses with compositions (45–m)ZnO–(55–n)B2O3–(m + n)Sb2O3 (0 ≤ m, n ≤ 15 mol%) were synthesized via the melt-quenching technique to investigate the impact of Sb2O3 substitution on structural, thermal, and radiation shielding properties. X-ray diffraction confirmed the amorphous nature of the synthesized glass samples. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy revealed significant structural rearrangements, including an increase in non-bridging oxygen content with rising Sb2O3 concentrations, as evidenced by the shifting and intensification of characteristic absorption bands. Differential thermal analysis demonstrated that the glass transition temperature decreased from 580 °C to 490 °C with increasing Sb2O3, while the thermal stability parameter (ΔT) improved from 144 °C to 256 °C, particularly when B2O3 was replaced. Density increased from 3.121 g/cm3 to 3.836 g/cm3, and molar volume expanded from 24.01 cm3/mol to 31.16 cm3/mol. Radiation shielding performance was significantly enhanced: at 10 MeV, the linear attenuation coefficient increased from 0.0768 cm−1 to 0.1142 cm−1 (~ 49%) when replacing B2O3 and to 0.0983 cm−1 (~ 28%) when replacing ZnO. The half-value layer decreased from 9.02 cm to 6.07 cm at 15 mol% Sb2O3, confirming improved photon attenuation. Overall, this work offers valuable insights into the interplay between composition, structure, and functional properties in Sb2O3-doped zinc borate glasses.

Keywords: Zinc Borate glasses, Density, Glass transition, Melt-quench technique, Thermal expansion

Subject terms: Ceramics, Glasses

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6425-936X.

Introduction

The pursuit of advanced materials for radiation shielding and related applications has driven significant research interest in specialized glass compositions. Borate glasses have emerged as particularly promising candidates due to their exceptional versatility in accommodating various structural modifications while maintaining desirable properties such as high thermal stability, superior glass-forming ability, and remarkable optical transmission characteristics1,2. These fundamental attributes, combined with their relatively low melting points, position borate glasses at the forefront of materials science innovation, enabling their deployment across diverse technological domains, from optical devices to radiation protection systems3.

The incorporation of zinc oxide into borate glass networks has revolutionized their structural and functional properties, marking a significant advancement in glass engineering. When introduced into the borate network, ZnO exhibits a fascinating dual nature - functioning both as a network modifier and as a network former, according to its coordination environment4. As a modifier, it disrupts the continuous B-O-B bonds, creating non-bridging oxygen atoms that significantly influence the glass’s physical properties. Alternatively, when acting as a network former, ZnO forms tetrahedral ZnO4 units that integrate into the glass network5, enhancing structural stability and improving thermal characteristics. This multifaceted behavior offers opportunities to finely tune the overall structural arrangement, thermal expansion, chemical stability, and optical responses of borate-based glass formulations. Consequently, zinc borate glasses, with their relatively low melting point and adaptable structural network, have been employed for plasma display panels, low-temperature co-fired ceramics (LTCC), and numerous high-performance optoelectronic devices6–8.

Recent investigations have demonstrated the efficacy of incorporating heavy metal oxides such as TeO2, Bi2O3, and PbO into zinc and borate glass matrices to enhance radiation shielding properties, thermal stability, and optical properties9–12. Notably, these heavy metal oxides can act as both network formers and network modifiers, depending on their coordination environment, thereby offering tunability in optical, mechanical, and radiation-attenuating characteristics. Nevertheless, there remains a continuous demand for identifying alternative heavy metal oxides that can offer comparable or superior multifunctional performance while maintaining cost-effectiveness and ease of processing.

Despite the progress made with TeO2, Bi2O3, and PbO dopants, comparatively fewer investigations have focused on incorporating antimony trioxide (Sb2O3) into borate glasses. Sb2O3 exhibits heavy metal oxide characteristics, contributing high density, broad optical transmission, and strong radiation attenuation potential13,14. Although Sb2O3 alone has a relatively weak glass-forming ability, its integration into borate networks can significantly alter the structural arrangement and lower the glass transition temperature without sacrificing overall stability15,16. These attributes suggest that Sb2O3-containing glasses could be highly beneficial for applications requiring a combination of excellent thermal stability and radiation shielding performance.

In light of these considerations, the present study aims to examine how substituting Sb2O3 for ZnO and B2O3 alters the structural, physical, thermal, and radiation-shielding attributes of zinc borate glasses. By adjusting the amount of Sb2O3 introduced, we elucidate the underlying structural transformations and correlate these changes with the observed property enhancements. The outcomes of this investigation are anticipated to facilitate the design of next-generation borate-based glasses that combine strong thermal stability with effective radiation protection for emerging technological applications.

Materials and methods

A series of ZnBSb glasses with the nominal composition (45–m)ZnO–(55–n)B2O3–(m + n)Sb2O3 (m, n = 0–15 mol%) was synthesized via the well-established melt-quench method, as outlined in Table 1. High-purity zinc oxide (ZnO, Reachim), boric acid (H3BO3, Etimaden), and antimony trioxide (Sb2O3, Sigma-Aldrich) were precisely weighed and homogenized. The batch mixture was preheated in a muffle furnace at 250 °C for one hour to dehydrate boric acid, ensuring complete conversion to boron trioxide (B2O3). The resulting dry mixture was then transferred into a standard 60-mL corundum crucible and melted in a SiC rod-heated furnace (model Nabertherm HTCT 01/16 C) at 1280 °C for one hour, thereby facilitating complete fusion. The resulting melts were cast into molds to form ZnBSb glass samples in two different shapes: sticks with dimensions of 5 × 5 × 50 mm3 and disks with a diameter of 30 mm and a thickness of 2.5 mm. The samples were then annealed at 510–590 °C in a SNOL 7.2/900 muffle furnace for ten hours to eliminate any residual stresses. Finally, at a carefully controlled rate of 50 °C per hour, the ZnBSb samples were refrigerated to ambient temperature.

Table 1.

Comprehensive glass chemical composition (mol%), along with density (ρ) and molar volume (Vm) for ZnBSb glasses.

| Sample identifier | ZnO | B2O3 | Sb2O3 | ρ, (g/cm3) |

Vm, (cm3/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45Z40B15S | 45 | 40 | 15 | 3.836 | 28.206 |

| 30Z55B15S | 30 | 55 | 15 | 3.415 | 31.165 |

| 35Z50B15S | 35 | 50 | 15 | 3.543 | 29.091 |

| 40Z45B15S | 40 | 45 | 15 | 3.699 | 29.091 |

| 45Z45B10S | 45 | 45 | 10 | 3.610 | 26.898 |

| 35Z55B10S | 35 | 55 | 10 | 3.328 | 28.823 |

| 40Z50B10S | 40 | 50 | 10 | 3.461 | 27.886 |

| 45Z50B5S | 45 | 50 | 5 | 3.367 | 25.544 |

| 40Z55B5S | 40 | 55 | 5 | 3.267 | 26.145 |

| 45Z55B | 45 | 55 | 0 | 3.121 | 24.010 |

Thermal analysis of the ZnBSb glasses was systematically assessed using a MOM Q-1500 Derivatograf (Paulik-Paulik-Erdey, Hungary) at a constant heating rate of 5 °C per minute for all samples in Pt crucibles, with high-purity α-Al2O3 (Thermo Fisher) as a reference. The following characteristic temperatures were recorded from each DTA curve: Tg.t.—the glass transition temperature, To – the onset of crystallization (the point at which the exothermic reaction begins), Tp—the peak temperature of crystallization (the maximum reaction rate), and Tm.t.—the melting temperature. These values provide insight into the glass’s thermal stability and crystallization behavior. Further examination of the samples was conducted using a dilatometer (model GT-1000) at a heating rate of 3 °C per minute to determine the glass transition (Tg.t.) temperature, the dilatometric (Tdil) softening point, and the coefficient (CTE) of linear thermal expansion17. The amorphous structure of the as-prepared glasses and the presence of crystalline phases (detection threshold ~ 2 wt%) after heat treatment were verified using a DRON-3 M diffractometer. The crystallization analysis was further enhanced through field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), which provided detailed insights into the morphological characteristics of the heat-treated ZnBSb samples.

Infrared spectral analysis was performed with an FT-IR spectrometer (IRSpirit-X) over the range of 1600–400 cm−1 at a resolution of 2 cm−1 (40 scans, SqrTriangle apodization) using the potassium bromide pellet technique. The density of the ZnBSb glass sample was measured at standard ambient temperature using the Archimedes principle with distilled water as the immersion liquid18, utilizing a Radwag АЅ analytical balance with 0.0001-gram precision. Density values are reproducible within ± 0.001 g/cm3 for repeated measurements of the same sample. The assessment of the radiation shielding efficacy of the fabricated ZnBSb glasses was accomplished by employing the PSD/Phy-X software19. This analysis provided theoretical calculations for an array of shielding-related metrics20, including the linear attenuation coefficient (LAC), the tenth-value layer (TVL), the half-value layer (HVL), and the effective atomic number (Zeff) across gamma-ray energies spanning from 0.015 MeV to 15 MeV. These parameters were used to evaluate the impact of Sb2O3 content on the attenuation capabilities of the ZnBSb glasses.

Results and discussion

Structural analysis

The utilization of X-ray diffraction analysis in the examination of ZnBSb glass specimens has led to the discernment of their amorphous structural nature, as illustrated by the XRD patterns displayed in Fig. 1a. The diffractogram manifests a distinctive broad hump traversing the 2-theta range of 27° to 42°21, a phenomenon that contrasts with the sharp, well-defined peaks commonly observed in crystalline materials. This feature is a hallmark of amorphous glassy structures, where atoms are arranged in a disordered, non-crystalline configuration. Regarding the coloration effect, the images of the ZnBSb glass samples in Fig. 1b show a progressive yellowing as the Sb2O3 content increases. The base zinc-borate (45ZnO·55B2O3) glass is clear, but with the introduction of Sb2O3, the samples acquire a yellow tint that becomes more pronounced with higher Sb2O3 concentrations.

Fig. 1.

XRD results and corresponding visual representation of ZnBSb glass samples.

Figure 2 depicts the FT-IR absorption spectra of 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass and its modifications resulting from the replacement of varying amounts of ZnO and B2O3 with Sb2O3. These spectra exhibit prominent absorption bands corresponding (Table 2) to the vibrational modes of the borate network. The bands observed in the spectral region between 1600 and 400 cm−1 are attributed to various borate structural units, including tetrahedral BO4 and triangular BO3 groups, as well as vibrations associated with zinc and antimony oxide contributions. The spectra demonstrate systematic changes increasing Sb2O3 content, suggesting significant structural rearrangements in the glass matrix. The base 45Z55B glass exhibits characteristic absorption peaks at 1372, 1256, 1084, 1022, 882, 688, 466, and 424 cm−1, associated with BO4 tetrahedra, BO3 triangles, B–O–B linkages, and Zn–O vibrations, in agreement with prior studies22.

Fig. 2.

FT-IR spectra of ZnBSb glasses.

Table 2.

Wavenumbers and corresponding assignments for FTIR spectra of ZnBSb samples.

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Assignment | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1372–1354 | Stretching vibrations of non-bridging B–Ø bonds in metaborate units | 22,23 |

| 1256–1238 | Stretching vibrations of bridging B–O bonds in pyroborate units | 22,23 |

| 1084–1078 | Stretching vibrations of B–O bonds in tetrahedral BO4 units from tri-, tetra-, and pentaborate groups | 23,24 |

| 1022–1012 | Stretching vibrations of B–O bonds in tetrahedral BO4 units from diborate groups | 22,25 |

| 882–878 | Symmetric B–O–B stretching of pyroborates dimers | 23,26 |

| 692–688 | B–O–B bending modes of triangular borate units and symmetric stretching vibrations of Sb–O bonds in SbO3 pyramidal structures | 27–29 |

| 468–466 | Bending vibrations of Zn–O bonds within ZnO4 units | 24,25 |

| 424–418 | Vibration of zinc (Zn2+) cations | 8,30 |

The spectra exhibit a series of well-defined absorption bands, which can be assigned to specific vibrational modes based on prior literature. In the high-frequency region (1600 –1200 cm−1), the substitution of B2O3 with Sb2O3 leads to more pronounced changes in the absorption bands at 1372–1354 cm−1 and 1256–1238 cm−1, corresponding to non-bridging B-Ø bonds in metaborate units and bridging B-O bonds in pyroborate units, respectively. This effect is particularly evident in samples where B2O3 content decreases from 55 to 40 mol%, suggesting that Sb2O3 preferentially disrupts the borate network connectivity. In contrast, when ZnO is replaced by Sb2O3, these bands show more subtle shifts, indicating that zinc’s network-modifying role is gradually assumed by antimony without drastically altering the fundamental borate structure. The presence of BO4 tetrahedral units is confirmed by characteristic absorption bands in the 1084–1078 cm−1 and 1022–1012 cm−1 ranges, corresponding to B–O stretching vibrations in tri-, tetra- and pentaborate groups, as well as diborate units, respectively. The increase in Sb2O3 concentration is associated with a gradual shift of these peaks, suggesting structural rearrangements in the borate framework. The band at 882–878 cm−1, attributed to pyroborate dimers, exhibits enhanced definition with increasing Sb2O3 content, particularly in compositions where it replaces B2O3. The vibrational modes observed in the 692–688 cm−1 range indicate contributions from B–O–B bending modes in diverse borate triangles, along with symmetric stretching vibrations of Sb–O bonds within SbO3 pyramids. The appearance of bands associated with Sb–O bonds suggests the integration of antimony into the glass network, leading to structural rearrangements. These findings are consistent with studies on antimony-doped borate glasses, which report similar structural transformations27. Notably, in the low-wavenumber region, bands at about 466 cm−1 correspond to bending vibrations of Zn–O within ZnO4 units, and the shoulder near 420 cm−1 stems from vibrations of Zn<Superscript>2+</Superscript> cations. Overall, the observed FT-IR spectral trends suggest that Sb2O3 incorporation induces a reorganization of the borate network, primarily through the creation of non-bridging oxygens and structural rearrangements in tetrahedral BO4 and triangular BO3 units.

Thermal and crystallization behavior

Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) provides a precise way to examine the thermal behavior of glass materials by measuring the temperature difference between a sample and a reference under identical heating. It reveals key thermal events31 - such as glass transition (Tg.t.), crystallization (To and Tp), and melting (Tm.t.) - thus offering crucial insights into a glass’s stability and crystallization tendencies.

The DTA curves in Fig. 3 illustrate the influence of Sb2O3 on the thermal properties of 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass when replacing either ZnO or B2O3. As the concentration of Sb2O3 increases from 0 to 15 mol% in place of ZnO, a downward trend is observed in both the glass transition (Tg.t.) and the onset of crystallization (To) temperatures. For instance, the Tg.t. decreases from 580 °C in the base composition (45Z55B) to 550 °C in the 40Z55B5S sample and subsequently to 495 °C in the 30Z55B15S sample. A comparable decline is observed in the To values, which shift from 724 °C in the base composition to 644 °C in the 30Z55B15S sample. Similarly, the crystallization peak (Tp) temperature also decreases, with a notable change from 790 °C in the 45Z55B sample to 662 °C in the 30Z55B15S sample. Samples with lower ZnO content (e.g., 30Z55B15S) exhibit two crystallization exotherms and multiple endothermic transitions, indicating multi-stage crystallization due to the partial destabilization of the zinc borate network as Zn<Superscript>2+</Superscript> is replaced by Sb3+. This leads to the formation of multiple phases across distinct temperature ranges, a phenomenon previously reported in zinc-deficient borate glasses32. The curves also show a progressive reduction in melting temperature (Tm.t.), reflecting Sb2O3’s fluxing effect, which lowers the viscosity and the melting point of the glass matrix. Conversely, when Sb2O3 partially replaces B2O3, an increase in both the To and Tp is observed with an increase in the Sb2O3 content. As an illustration, the To value shifts from 724 °C in the 45Z55B sample to 748 °C in the 45Z40B15S sample, while the Tp rises from 790 °C to 802 °C. This suggests that Sb2O3 enhances the thermal stability of the glass network when replacing B2O3, making it more resistant to crystallization. Furthermore, the decreasing crystallization peak intensity with increasing Sb2O3 content demonstrates that replacing B2O3 with Sb2O3 reduces the crystallization tendency of the glass. However, the Tm.t. and Tg.t. decreases slightly, indicating that Sb2O3 still acts as a flux, reducing the glass’s viscosity.

Fig. 3.

DTA thermograms of ZnBSb glasses.

Using the Dietzel33 criterion (ΔT = To – Tg.t.) as a measure of thermal stability, it becomes clear that Sb2O3 influences the thermal stability differently depending on whether it replaces ZnO or B2O3. When Sb2O3 substitutes ZnO, Tg.t. and To both decrease, but ΔT shows a slight increase, indicating a marginal enhancement in thermal stability despite the reduced absolute temperature values. For example, the base composition (45Z55B) has ΔT = 144 °C. Replacing 5 mol% ZnO with Sb2O3 (40Z55B5S) results in ΔT = 150 °C, and further substitution to 10 mol% Sb2O3 (35Z55B10S) increases ΔT to 165 °C. When Sb2O3 replaces B2O3, the glass shows a more pronounced increase in ΔT, signifying a significant enhancement in thermal stability. The introduction of 10 mol% of Sb2O3 in lieu of B2O3 (45Z45B10S) results in an increase in the ΔT to 244 °C. At the highest level of substitution, 15 mol% Sb2O3 (45Z40B15S), the ΔT reaches 256 °C. This significant increase suggests that Sb2O3 strengthens the glass network when replacing B2O3, acting as a stabilizing agent against crystallization. The enhanced stability can be attributed to structural modifications in the glass network. Sb3+ ions, due to their higher polarizability and larger ionic radius compared to B3+, may contribute to increased network rigidity, requiring greater thermal energy for structural reorganization. Additionally, Sb2O3 may enhance network connectivity through the formation of Sb–O–B linkages or by modifying the distribution of non-bridging oxygens, leading to a more resistant glass matrix. This structural reinforcement effectively delays the onset of crystallization, widening the temperature range between Tg.t. and To, thereby improving the glass’s resistance to devitrification and enhancing its overall thermal stability.

Figure 4 provides a combined analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (left side) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (right side) for three glass samples after controlled heat treatment. This heat treatment process, which involved heating the samples to their respective crystallization temperatures (identified from DTA analysis) for 5 h, was conducted to understand the crystallization behavior and phase evolution of these materials. Such understanding is crucial for applications where these glasses might experience elevated temperatures during service, such as in radiation shielding components near heat-generating sources or in sealing applications for electronic devices.

Fig. 4.

XRD patterns and SEM micrographs of heat-treated ZnBSb samples: 45Z55B (a), 40Z55B5S (b), and 35Z55B10S (c), showing crystallization phases and corresponding microstructural evolution.

The heat-treated samples − 45Z55B, 40Z55B5S, and 35Z55B10S - show distinct crystallization patterns that provide valuable insights into their thermal stability and phase transformation behavior. The sharp peaks in the XRD patterns indicate the formation of well-defined crystalline phases during heat treatment, contrasting with the broad, diffuse patterns of the original glasses (shown earlier in Fig. 1a). This controlled crystallization study helps predict how these materials might behave in high-temperature applications and allows us to understand the role of Sb2O3 in influencing phase evolution. The 45Z55B sample, subjected to a heat treatment at 790 °C for a period of 5 h, displays the presence of peaks corresponding to Zn4B6O13 and Zn4B2O7, indicative of the formation of these crystalline phases during the aforementioned heat treatment. The substitution of ZnO with Sb2O3 in the 35Z55B10S and 30Z55B15S samples results in the emergence of Sb2ZnO4, which emerges alongside those of ZnB2O4. This substitution alters the crystallization dynamics, promoting phases that include Sb2ZnO4 at the expense of the zinc-borate phases seen in 45Z55B.

The SEM findings (see Fig. 4, right side) serve to supplement the XRD data by elucidating the microstructural changes associated with the varying compositions. In Fig. 4a (45Z55B), the crystal morphology consists predominantly of larger, well-defined hexagonal and rectangular crystals with smooth surfaces interspersed with smaller rod-like crystals. Figure 4b (40Z55B5S) shows notable morphological changes with the introduction of 5 mol% Sb2O3. The crystals are larger and exhibit enhanced faceting compared to the undoped sample, suggesting improved crystallization kinetics. The rods appear less prominent, replaced by a denser arrangement of well-faceted hexagonal crystals. When the Sb2O3 concentration is increased to 10 mol% in the 35Z55B10S sample (see Fig. 4c), the morphology becomes more complex, with an increased number of smaller rod-like or needle-like formations intertwined with the larger crystals. This suggests that a higher Sb2O3 content introduces additional crystalline phases or facilitates the preferential growth of these secondary structures, leading to a more intricate and interconnected network.

Figure 5 illustrates the alterations in dilatometric properties (CTE, Tg.t., and Tdil) that arise from the substitution of ZnO and B2O3 with Sb2O3 in the initial 45Z55B glass composition. The base composition (45Z55B) demonstrates a CTE of 4.65 ppm/°C, a Tg.t. of 586 °C, and a Tdil of 611 °C. An increase in the Sb2O3 content results in a notable alteration of these parameters. The substitution of B2O3 with Sb2O3 while maintaining the ZnO content (e.g., 45Z50B5S and 45Z40B15S) has been observed to result in a notable reduction in both Tg.t. and Tdil, while simultaneously exhibiting a significant increase in CTE. The 45Z50B5S composition (5 mol% Sb2O3) exhibits a Tg.t. of 554 °C, a Tdil of 579 °C, and a higher CTE of 5.01 ppm/°C in comparison to the base glass. Upon further increasing the concentration of Sb2O3 in the 45Z40B15S composition (to 15 mol%), the Tg.t. and Tdil values decrease to 497 °C and 529 °C, respectively, while the CTE rises to 5.95 ppm/°C. The substitution of ZnO for Sb2O3 while holding the B2O3 content constant also leads to a reduction in Tg.t. and Tdil, along with an augmentation in CTE. When 5 mol% Sb2O3 replaces ZnO (45Z50B5S), the CTE increases to 5.05 ppm/°C, while the Tg.t. and Tdil temperatures decrease to 557 °C and 582 °C, respectively. A further increase in Sb2O3 content to 15 mol% (30Z55B10S) continues this trend, with the CTE rising to 5.9 ppm/°C, while Tg.t. and Tdil are further lowered to 503 °C and 539 °C, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Dilatometry results of ZnBSb glasses.

The underlying mechanism driving these changes can be traced to the fundamental role of Sb2O3 as a network modifier within the glass structure. As Sb2O3 is incorporated into the glass structure, it disrupts the existing boron-oxygen network by breaking B–O–B linkages and generating non-bridging oxygen (NBO) sites34. This structural depolymerization process reduces the overall network connectivity, manifesting as lower glass transition and dilatometric softening temperatures. Concurrently, the diminished network rigidity facilitates increased molecular mobility, directly translating to enhanced thermal expansion characteristics. These observations regarding increasing CTE with higher Sb2O3 content closely parallel the findings of Šubčík et al.35 on antimony-doped zinc borophosphate glasses, where the CTE likewise rose proportionally with Sb2O3 concentration due to the progressive weakening of chemical bonds in the glass network.

Density and molar volume

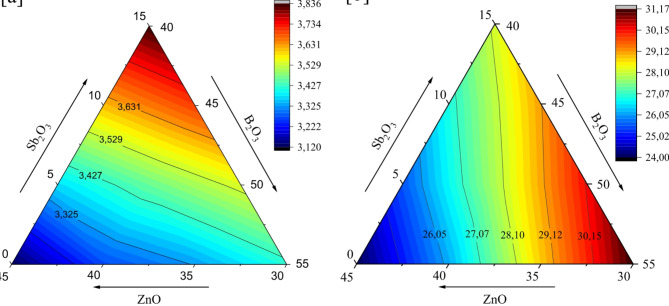

The density and molar volume of glasses are fundamental physical properties that provide critical insights into the structural modifications occurring within the glass network36. The substitution of ZnO and B2O3 with Sb2O3 in the 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass composition induces notable variations in density and molar volume, as depicted in Fig. 6a and b. The higher molar mass of Sb2O3 (291.51 g/mol), compared to ZnO (81.41 g/mol) and B2O3 (69.62 g/mol), primarily accounts for the marked increase in density. For instance, in the 45Z40B15S sample, which contains 15 mol% Sb2O3, the density reaches 3.836 g/cm3, the highest recorded value. In contrast, the base composition without Sb2O3 (45Z55B) has a much lower density of 3.120 g/cm3. This trend can be visualized in Fig. 6a, where the density contours shift toward higher values as the Sb2O3 concentration increases. Accompanying this rise in density is a systematic increase in the molar volume, as illustrated in Fig. 6b. At 0 mol% Sb2O3 (45Z55B), the molar volume is the lowest at 24.010 cm3/mol, indicating a relatively compact glass network. With the substitution of 5 mol% Sb2O3 (45Z50B5S), the molar volume increases to 25.544 cm3/mol, and at 15 mol% Sb2O3 (45Z40B15S), it peaks at 28.206 cm3/mol. This increase reflects the larger ionic radius (0.76 Å) and structural influence of Sb3+ ions, which expand the glass network and reduce overall packing efficiency. Overall, Fig. 6a and b reveal a clear trend: introducing Sb2O3 into the 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass composition tends to increase both the density and the molar volume of the glass. The specific values depend on which oxide (ZnO or B2O3) is being replaced and by how much, but the overall effect is a systematic shift toward higher density and molar volume as Sb2O3 substitution increases.

Fig. 6.

Density (a) and Molar volume (b) results of ZnBSb glasses.

Radiation shielding performance

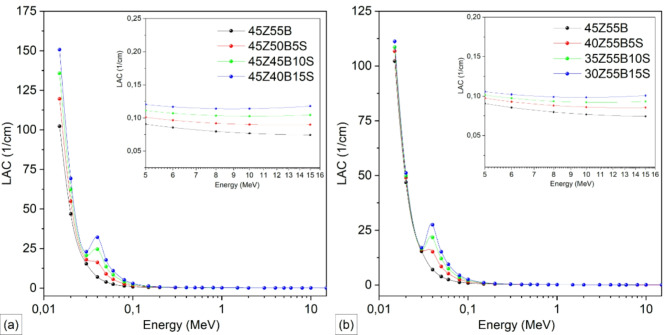

Figure 7 compares the linear attenuation coefficients (LAC) of 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass when B2O3 (Fig. 7a) and ZnO (Fig. 7b) are partially substituted by Sb2O3 over the photon energy range extending from 15 keV to 15 MeV. In Fig. 7a, reducing B2O3 content from 55 to 40 mol% and replacing it with up to 15 mol% Sb2O3 (indicated by the transition from black to blue curves) significantly enhances the LAC values at all photon energies. Similarly, Fig. 7b shows that decreasing ZnO from 45 to 30 mol% while increasing Sb2O3 to 15 mol% consistently raises the LAC. Both substitution series reveal a consistent improvement in photon attenuation with each increment of Sb2O3. In the low-energy range (< 0.1 MeV), photoelectric absorption dominates37, yielding very high LAC values. As energy increases, the curves decrease and converge, reflecting a shift toward Compton scattering (CS) and, ultimately, pair production (PP) at higher energies38,39. Nonetheless, glasses with more Sb2O3 invariably show higher LACs. For instance, at 10 MeV, the LAC increases from 0.0768 cm−1 in 45Z55B to 0.1142 cm−1 in 45Z40B15S for the B2O3 substitution series; likewise, it rises from 0.0768 cm−1 in 45Z55B to 0.0983 cm−1 in 30Z55B15S for the ZnO substitution series. Overall, the results confirm that increasing Sb2O3 content improves gamma-ray attenuation across the full energy range. This improvement is consistent with previous research indicating that Sb2O3 enhances gamma-ray attenuation in sodium-boro-silicate glasses40.

Fig. 7.

Impact of substituting B2O3 (a) and ZnO (b) with Sb2O3 in 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass on LAC values.

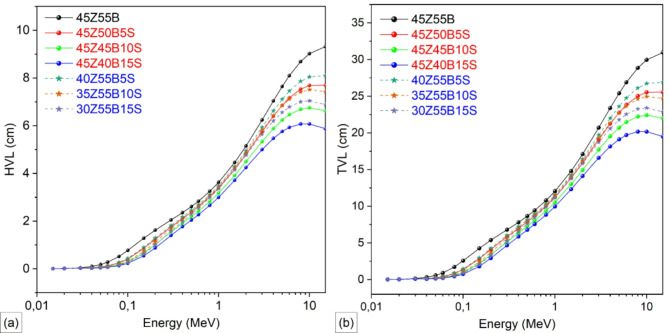

Figure 8a shows the variation of the half-value layer (HVL) with increasing photon energy for ZnBSb glass samples with different substitutions of B2O3 and ZnO with Sb2O3 in the 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass composition. Figure 8b illustrates the corresponding trend for the tenth-value layer (TVL). Both HVL and TVL exhibited an increasing trend with photon energy, thus indicating the energy-dependent attenuation behavior of the glass samples. At lower energies (e.g., 0.015–0.1 MeV), the glass samples demonstrate smaller HVL and TVL values, reflecting higher attenuation due to the dominance of the photoelectric effect. For instance, the HVL at 0.1 MeV energy for 45Z55B is approximately 0.7741 cm, while for 45Z40B15S, it is around 0.2293 cm, reflecting a decrease of about 70%. Similarly, the TVL values at the same energy are 2.5714 cm for 45Z55B and 0.7618 cm for 45Z40B15S, indicating a marked improvement in attenuation performance with Sb2O3 addition. This reduction indicates enhanced photon attenuation due to the higher atomic number of Sb, which boosts photoelectric absorption. As photon energy increased, both HVL and TVL values rose for all glass samples, driven by the reduced effectiveness of photoelectric absorption and the dominance of CS and PP. However, even at higher energies, samples with higher Sb2O3 content maintained lower HVL and TVL values compared to those without Sb2O3. For example, at 10 MeV, the HVL for 45Z55B is 9.0215 cm compared to 6.0714 cm for 45Z40B15S, showing a reduction of about 33%. This behavior demonstrates the energy-dependent attenuation characteristics of the glass and underscores the significant role of Sb2O3 in enhancing the radiation shielding capabilities of the material.

Fig. 8.

Variation in HVL (a) and TVL (b) values with photon energy for ZnBSb glasses, showing the effects of substituting varying amounts of B2O3 and ZnO with Sb2O3.

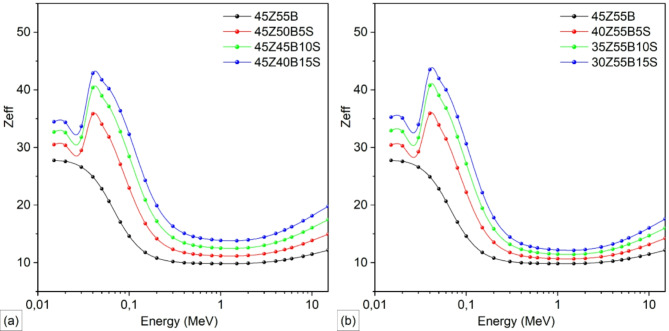

Figure 9 illustrates the alteration of the Zeff values with photon energy for ZnBSb glasses, showing the impact of partial substitution of B2O3 (Fig. 9a) and ZnO (Fig. 9b) with Sb2O3 in the 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass composition. The Zeff demonstrates a distinct dependence on photon energy, showing a marked increase surrounding 0.040 MeV due to the K-absorption edge of antimony atoms41,42, where the photon energy is sufficient to eject inner-shell electrons, thereby increasing attenuation. At lower energies (e.g., 0.1 MeV), the Zeff values for glasses with 15 mol% Sb2O3 substitution (e.g., 45Z40B15S in Figs. 9a and 30Z55B15S in Fig. 9b) are notably higher, at approximately 32.3062 and 30.6701, respectively, compared to their counterparts with no Sb2O3 substitution, which exhibit values of approximately 14.6243. The notable increase in Zeff with Sb2O3 incorporation can be attributed to the higher atomic number (Z = 51) of antimony, which enhances the dominance of the photoelectric effect at low photon energies. This effect is particularly pronounced in the 0.015–0.1 MeV range, where photoelectric absorption is the predominant interaction mechanism43. Moreover, the substitution of B2O3 for Sb2O3 (see Fig. 9a) results in a more substantial enhancement of Zeff compared to the replacement of ZnO. This is attributable to the lower atomic number of boron (Z = 5) relative to zinc (Z = 30), thereby amplifying the effect of the substitution on enhancing the overall photon attenuation efficiency. The energy-dependent behavior of Zeff values exhibits a distinct pattern. After reaching a peak around 0.040 MeV – attributed to the K-edge absorption of Sb – the Zeff values gradually decrease as the photon energy increases, reaching a minimum at approximately 1 MeV. This trend is a result of the transition from photoelectric absorption (which dominates at lower energies and is highly dependent on the atomic number) to Compton scattering, which becomes the predominant interaction in the intermediate energy range. Beyond this point, a slight increase in Zeff is observed up to 15 MeV, indicating the gradual transition from Compton scattering to pair production, where heavier elements continue to exhibit better attenuation characteristics. The improvements in LAC, HVL, TVL, and Zeff underscore the pivotal role of Sb2O3, with its higher atomic number, in boosting photon attenuation, making these glasses highly effective for radiation shielding applications.

Fig. 9.

Impact of substituting B2O3 (a) and ZnO (b) with Sb2O3 in 45ZnO·55B2O3 glass on Zeff values.

Conclusions

The investigation of antimony-doped zinc borate glasses demonstrated significant improvements in structural, thermal, and radiation shielding properties with increasing Sb2O3 content. The results confirmed that the amorphous nature of the glass was maintained across all compositions, with Sb2O3 incorporation leading to significant structural rearrangements, as evidenced by FT-IR analysis. The thermal characteristics showed remarkable improvement, particularly when B2O3 was replaced with Sb2O3. The thermal stability parameter (ΔT) increased substantially from 144 °C in the base composition to 256 °C at 15 mol% Sb2O3 substitution, demonstrating enhanced crystallization resistance. The coefficient of thermal expansion increased from 4.65 to 5.95 ppm/°C, indicating reduced network rigidity and enhanced flexibility of the glass matrix. The density and molar volume exhibited systematic increases with Sb2O3 content, reaching maximum values of 3.836 g/cm3 and 28.206 cm3/mol for the 45Z40B15S composition, attributable to the higher atomic mass and ionic radius of antimony. Most significantly, the radiation shielding capabilities show marked enhancement across the entire studied energy spectrum. The linear attenuation coefficient at 10 MeV increased by 49% (from 0.0768 cm−1 to 0.1142 cm−1) when substituting B2O3 with Sb2O3, while the half-value layer decreased by approximately 28% (from 9.02 cm to 6.07 cm). These improvements were particularly pronounced when B2O3 was replaced with Sb2O3, rather than substituting ZnO, due to the greater contrast in atomic numbers. These comprehensive findings establish Sb2O3-doped zinc borate glasses as exceptional candidates for advanced applications requiring both structural integrity and radiation protection. The demonstrated ability to fine-tune thermal, structural, and radiation shielding properties through controlled Sb2O3 substitution opens new possibilities for deployment in specialized technical applications, particularly in environments demanding robust radiation protection and thermal stability.

Author contributions

YH conceptualization, investigation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing; AZ methodology, investigation, formal analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bengisu, M. Borate glasses for scientific and industrial applications: a review. J. Mater. Sci.51, 2199–2242 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topper, B. & Möncke, D. Structure and properties of borate glasses. in Phosphate and Borate Bioactive Glasses 162–191 (The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2022).

- 3.Sayyed, M. I. et al. Optical and radiation shielding features for a new series of Borate glass samples. Optik239, 166790 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cetinkaya Colak, S., Akyuz, I. & Atay, F. On the dual role of ZnO in zinc-borate glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 432, 406–412 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sindhu, S., Sanghi, S., Agarwal, A., Kishore, N. & Seth, V. P. Effect of V2O₅ on structure and electrical properties of zinc Borate glasses. J. Alloys Compd.428, 206–213 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebastian, M. T., Wang, H. & Jantunen, H. Low temperature co-fired ceramics with ultra-low sintering temperature: A review. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci.20, 151–170 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naresh, P. et al. Dielectric and spectroscopic features of ZnO–ZnF2–B2O3:MoO3 glass ceramic—a possible material for plasma display panels. J. Mater. Sci. : Mater. Electron.25, 4902–4915 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanamar, K. et al. Nonlinear optical coefficients of Samarium–activated lithium zinc Borate glasses in femtosecond and nanosecond regimes. Opt. Laser Technol.168, 109859 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolavekar, S. B. & Ayachit, N. H. Impact of variation of TeO2 on the thermal properties of lead Borate glasses doped with Pr2O3. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 137, 475 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolavekar, S. B. & Ayachit, N. H. The role of Bi2O3 and Sm2O3 on the thermal properties of phospho-zinc tellurite glasses. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.148, 13263–13271 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goleus, V. I., Hordieiev, Y. S. & Nosenko, A. V. Properties of low-melting glasses in the system PbO–ZnO–B2O3–SiO2. Voprosy Khimii I Khimicheskoi Tekhnologii. 4, 92–96 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolavekar, S. B. et al. An investigation into gold nanoparticle-doped sodium-variety zinc Borate glasses for gamma and neutron shielding applications. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 139, 1120 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nalin, M., Poulain, M., Poulain, M., Ribeiro, S. J. L. & Messaddeq, Y. Antimony oxide based glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 284, 110–116 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Som, T. & Karmakar, B. Structure and properties of low phonon antimony glasses in the K2O–B2O3–Sb2O3–ZnO system. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.92, 2230–2236 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfryyan, N. et al. Physical and gamma-ray shielding characteristics of borophosphate glasses reinforced with Sb2O3: simulation and theoretical approach. J. Mater. Eng. Perform.10.1007/s11665-024-10613-4 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Som, T. & Karmakar, B. Structure and properties of low-phonon antimony glasses and nano glass-ceramics in K2O–B2O3–Sb2O3 system. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 356, 987–999 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hordieiev, Y. S. & Zaichuk, A. V. Structure, thermal and crystallization behavior of lead-bismuth silicate glasses. Results Mater.19, 100442 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hordieiev, Y. & Zaichuk, A. Thermal and crystallization behavior of aluminum-doped bismuth Borate glasses. MRS Adv.9, 671–677 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Şakar, E. et al. -X / PSD: development of a user friendly online software for calculation of parameters relevant to radiation shielding and dosimetry. Radiat. Phys. Chem.166, 108496 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayyed, M. I., Hamad, D. & Rashad, M. The role of ZnO in the radiation shielding performance of newly developed B2O3–PbO–ZnO–CaO glass systems. Radiat. Phys. Chem.223, 111896 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hordieiev, Y. S. & Zaichuk, A. V. Synthesis, structure and properties of PbO–PbF2–B2O3–SiO2 glasses. Chalcogenide Lett.19, 891–899 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osipova, L. M., Osipov, A. A. & Osipov, A. A. The structure of binary and iron-containing ZnO–B2O3 glass by IR, Raman, and Mössbauer spectroscopy. Glas Phys. Chem.45, 182–190 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iordanova, R. et al. Structure and luminescent properties of niobium-modified ZnO-B2O3:Eu3+ glass. Materials17, 1415 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahlawat, J. et al. Structural and optical characterization of IR transparent sodium-modified zinc Borate oxide glasses. Appl. Phys. Mater. Sci. Process.128 (2022).

- 25.Hanamar, K. et al. Physical, structural, and photoluminescence characteristics of Sm2O3 doped lithium zinc Borate glasses bearing large concentrations of modifier. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater.33, 1612–1620 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Topper, B. et al. Zinc Borate glasses: properties, structure and modelling of the composition-dependence of Borate speciation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.25, 5967–5988 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samuel, A. B., Kumar, V. V. R. K., Harsha, S. S., Nalam, S. A. & Kiran, P. P. Structural and optical studies of sodium zinc Borate glasses: effect of antimony in supercontinuum generation. Appl. Phys. B130 (2024).

- 28.Zhang, Y. et al. Effect of Sb2O3 on thermal properties of glasses in Bi2O3–B2O3–SiO2 system. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.92, 1881–1883 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hordieiev, Y. S. & Zaichuk, A. V. Study of the influence of R2O3 (R = Al, La, Y) on the structure, thermal and some physical properties of magnesium borosilicate glasses. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater.33, 591–598 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hordieiev, Y. S. & Zaichuk, A. V. Effect of the addition of Al2O3, ZnO and TiO2 on the crystallization behavior, thermal and some physical properties of lead Borate glasses. MRS Adv.8, 201–206 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musgraves, J., Hu, J. & Calvez, L. Springer Handbook of Glass (Springer, 2019).

- 32.Heuser, L., Nofz, M. & Müller, R. Alkali and alkaline Earth zinc and lead Borate glasses: sintering and crystallization. J. Non-Crystalline Solids: X. 15, 100116 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dietzel, A. Glass structure and glass properties. Glasstech Ber. 22, 41–50 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gad, M. M., Salama, E., Yousef, H. A., Hannora, A. E. & Assran, Y. Exploring the physical, structural, optical, and gamma radiation shielding properties of Borate glasses incorporating Sb2O3/MoO3. Opt. Mater.154, 115734 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Šubčík, J., Mošner, P. & Koudelka, L. Thermal behaviour and fragility of Sb2O3-containing zinc borophosphate glasses. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.91, 525–528 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolavekar, S. B. & Ayachit, N. H. Role of Bi2O3 in the thermal and structural analysis (theoretical) of the vanadium phosphate glasses. in AIP Conference Proceedings vol. 3231 050006 (AIP Publishing, 2024).

- 37.Sasirekha, C., Poojha, M. K. K., Marimuthu, K., Alqahtani, M. S. & Vijayakumar, M. Investigations on physical, structural, elastic, optical and radiation shielding properties of boro-phosphate glasses for radioactive waste management applications. Prog Nuclear Energy. 175, 105327 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaaban, K. S., Alotaibi, B. M. & Yousef, E. S. Effect of La2O3 concentration on the structural, optical and radiation-shielding behaviors of titanate borosilicate glasses. J. Electron. Mater.52, 3591–3603 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kolavekar, S. B., Hiremath, G. B., Patil, P. N., Badiger, N. M. & Ayachit, N. H. Investigation of gamma-ray shielding parameters of bismuth phospho-tellurite glasses doped with varying Sm2O3. Heliyon8, e11788 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zoulfakar, A. M. et al. Effect of antimony-oxide on the shielding properties of some sodium-boro-silicate glasses. Appl. Radiat. Isot.127, 269–274 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soraya, M. M., Ahmed, F. B. M. & Mahasen, M. M. Enhancing the physical, optical and shielding properties for ternary Sb2O3–B2O3–K2O glasses. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.33, 22077–22091 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ornketphon, O. et al. Photon shielding properties of oxyfluoride aluminophosphate glass added with Sb2O3 by using PHITS Monte Carlo simulation and experimental methods. Radiat. Phys. Chem.224, 111993 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolavekar, S. B., Hiremath, G. B., Badiger, N. M. & Ayachit, N. H. Investigation of the influence of TeO2 on the elastic and radiation shielding capabilities of phospho-tellurite glasses doped with Sm2O3. Nucl. Sci. Eng.197, 1506–1519 (2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.