Abstract

With the rapid aging of populations worldwide, the role of daycare centers in supporting older adults’ well-being has gained unprecedented attention. Despite the growing body of research in this area, systematic reviews focusing on high-quality literature remain scarce. This study aims to address this gap by providing an in-depth analysis of the existing literature on adult daycare centers. This study bridges this gap by conducting a 33-year bibliometric analysis of 853 publications from the Web of Science database (1990-2023), using VOSviewer, CiteSpace, and Biblioshiny. Through the analysis of countries and authors, it was found that research in this field is predominantly concentrated in regions such as North America, Asia, and Europe. Keyword analysis revealed 3 main research themes in the field of adult daycare centers: “physical and mental diseases,” “rehabilitative care,” and “social support.” There is a lack of comprehensive and systematic evaluation frameworks in the research on the architectural design and facilities of adult daycare centers. Meanwhile, the study highlights 3 key aspects for improving the design and facilities of adult daycare centers: (1) addressing the physical and psychological needs of the older adults, (2) enhancing rehabilitative care facilities, and (3) focusing on the needs of caregivers. This study not only maps research trends but also provides actionable directions for policymakers and practitioners to create more inclusive and effective older adult daycare support systems in response to the aging population.

Keywords: adult daycare centers, scoping review, bibliometric analysis, physical, and mental diseases, rehabilitative care, social support

Highlights.

● Three major research themes were identified: physical and mental diseases, rehabilitative services, and social support.

● The study highlights the urgent need for systematic evaluation frameworks for architectural design and caregiving facilities in Adult daycare centers.

Introduction

The concept of daycare centers originated in the United Kingdom in the mid-to-late 20th century, and was originally designed to provide an environment in which people with mental illness could continue to receive rehabilitation treatment in the community, with the aim of facilitating the reintegration of this group of people into their families and society.1,2 Over time, the scope of services provided by the daycare centers has been gradually expanded, and their clientele has gradually expanded from the initial group of people with mental illness to include a wider group of people, including children and the older adults.3,4 For the older adult population, daycare centers not only provide basic daily care services, but more importantly, they provide emotional support and opportunities for social participation, which are irreplaceable in alleviating the sense of loneliness of the older adults and enhancing their social participation.5,6 Adult daycare centers primarily refer to community-based institutions that provide daytime care for older adults, typically offering rehabilitation services, social activities, and nutritional meals. 7 However, the structure and scope of services of adult daycare centers vary across different countries. In the United States and European countries, adult daycare centers generally offer 3 main types of services: social day care, health/medical day care, and specialized dementia care.8,9 In contrast, in Asian countries such as China and Japan, older adult daycare centers models may have different focal points, with a greater emphasis on social support functions.7,10

With the continuous development and innovation of service models, daycare centers have significantly improved the quality of life of older persons through the provision of quality services and the creation of a proactive environment. 11 In addition to regular care services, these centers also provide personalized services such as transportation, meals, and companionship for seniors with mobility impairments, and this meticulous care helps to enhance seniors’ self-esteem, self-evaluation, and sense of control. 12 In recent years, an emerging community care model has begun to receive attention, which, by combining traditional health care services with community daycare, has formed an all-encompassing service system that integrates medical care, nursing care, and rehabilitation into 1 system. 13 As a result, daycare centers have become an important part of the community care field, and by constantly expanding the content and mode of service, they have improved the quality of life and social participation of the older adult population, while at the same time demonstrating their indispensable value and role in contemporary society.

As the service content and care model of daycare centers continue to improve, conducting research on performance evaluation has become essential. Tretteteig et al study the positive impact of daycare centers on family caregivers. It primarily highlights the positive role of these centers in meeting the diverse needs of older adults with dementia and reducing the burden on family caregivers. 14 Lunt et al highlighted the current reduction in daycare center services and the significant role of such centers in supporting older adult care. Meanwhile, the study also pointed out the scarcity of research on daycare services for older adults with chronic illnesses and intergenerational services. 15 Ayalon conducted a 2-round study involving 245 respondents from different care centers, revealing that constraints within social networks have differentiated impacts across communities. Older adults in various care communities can enhance their sense of belonging through extensive social networks. 16 Zhang et al employed structural equation modeling to identify key factors influencing the daily living care needs of older adults. Factors such as physical and mental health status, age, living conditions, economic factors, social support, and family circumstances were found to affect daily living, with physical and mental health being the strongest predicto. 17 Shao et al systematically evaluated the performance of community-based home care service centers. Using the SBM-DEA model, the study conducted an empirical analysis of 186 community organizations in Nanjing and established 6 evaluation dimensions: financial management, hardware facilities, team development, service management, service recipients, and organizational development. 18

In summary, the number of studies on community-based older adult care has been increasing yearly, with a focus primarily on care services, care models, and service performance evaluation. However, macro-level analysis, research trends, and hot topics in this field remain relatively underexplored. Therefore, this study primarily focuses on reviewing the literature on daycare centers, utilizing network modeling and visual analysis to provide insights into research trends and hotspots in this area. This gap makes it challenging for the academic community to achieve a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of overall development trends, core research topics, and their evolution in community daycare center studies, as well as to identify current research hotspots and potential future research directions. To address this, the present study aims to fill the aforementioned research gap by conducting an in-depth review and analysis of the literature on daycare centers, applying scientific bibliometric methods and visualization software to explore the differences in countries, authors, and keywords within the field’s main publications. Scoping reviews are ideal for mapping extensive fields with diverse topics, especially when the literature is wide-ranging and multidisciplinary. 19 This study is particularly well-suited for a scoping review, as it aims to explore a broad research area in adult daycare centers. To gain a comprehensive understanding of research dynamics and development trends, we conducted a scoping review study. This research addresses the following primary research questions:

RQ1: What are the current development trends and research hotspots on adult daycare centers?

RQ2: What are the current research gaps in research on the design and facilities in adult daycare centers?

Methodology

Selection of Method

In order to deeply analyze the existing relevant studies from a macro perspective, this study adopts bibliometrics, a quantitative research methodology. Bibliometrics is a discipline that employs statistical and inductive methods to analyze and quantify various forms of literature and information resources. 20 The term “Bibliometrics” was first coined by Paul Otlet in 1934. 21 However, the foundational concepts of modern bibliometrics were further developed by scholars such as Alfred Lotka, George Zipf, and Derek de Solla Price in the mid-20th century.22 -24 Bibliometrics, as a branch of statistics, focuses on visualizing the multiple distributions of various types of journal articles, books, and other literature in existing research by counting and analyzing data from existing literature. 25 Bibliometrics, as a statistical method for macro-level literature analysis, objectively quantifies and compares existing literature, enabling the analysis of current research trends and the prediction of future research directions from a macro perspective.26,27 In short, bibliometrics not only enhances researchers’ macroscopic view of the current field, but also promotes the rational allocation of academic resources and the efficient dissemination of research results

Selection of Visualization Tools

In order to present the results of the bibliometric analysis more intuitively, 3 visualization tools, VOSviewer, CiteSpace, and Biblioshiny, were selected for in-depth analysis of the data in this paper. 27 VOSviewer is a tool for building visual literature networks, which is particularly suitable for building visual network diagrams from large-scale literature databases about various types of journal articles, researchers, research institutes, countries, keywords, and so on. 28 CiteSpace is a widely used tool for scientific literature analysis and information visualization, which was developed by Prof. Chaomei Chen to help researchers discover and analyze trends, hotspots, and knowledge structures in the scientific literature. 29 The main functions of CiteSpace include co-citation analysis, emergent word detection, network visualization, temporal view, cluster analysis, etc., of which the most special function is emergent word detection, which can identify keywords with a rapidly increasing frequency in the current literature through data computation, and these usually represent new trends or hotspots in scientific research.30,31 Biblioshiny is a powerful literature analysis tool that provides users with data analysis and information visualization.32,33 It helps researchers to analyze trends, clusters and themes in the existing literature more clearly.34,35 In summary, all 3 tools (VOSviewer, CiteSpace, and Biblioshiny) visualize and analyze the existing literature from different perspectives, helping researchers to more accurately assess the trends, hotspots, and gaps in the current research field.

Selection of Data

The data for this study were obtained from the Web of Science (WoS) journal database. As a large and comprehensive journal retrieval platform, WoS includes high-quality journal literature across various disciplines. 36 By conducting a comprehensive search for literature related to adult daycare centers in the WoS database, this study identified 853 eligible academic articles. The search method employed an “ALL search” strategy, which has the advantage of retrieving all content related to the search terms in academic articles. Through multiple searches, many false positive results appeared, so in the advanced search, the author excluded keywords unrelated to the older adults, such as “children” and “child.” Additionally, the author found that articles before 1990 often lacked complete content, with most missing key information and having little research significance. Therefore, the time frame for article retrieval was limited to 1990 to 2023. Since the software used in the subsequent research is all in English, to ensure clearer presentation in the final visualizations, the search language was set to English. As a result, the following advanced search code was used in the WoS search engine:

((((ALL=(“day centers” OR “day center” OR “day centres” OR “day centre” OR “day care” OR “daycare”)) AND ALL=(“adult” OR “senior” OR “elderly” OR “old people” OR “elders” OR “older”)) NOT ALL=(“children” OR “child”) AND PY = (1990-2023)) AND LA=(“English”))

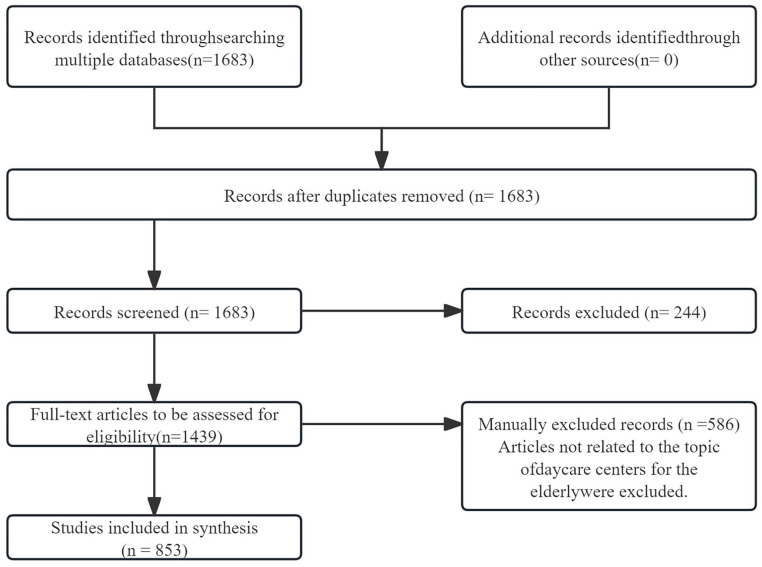

After conducting the advanced search using the above code, 1683 literature records were identified, including 1439 records of the “Article” type. “Article” type literature refers to articles published in scientific journals, which typically employ a peer review mechanism. Peer review is a quality control process in which other experts in the field review the article, making it more scientific, professional, and authoritative. 37 Furthermore, among these 1439 articles, there were some that were not relevant to the topic of “adult daycare centers.” Therefore, after filtering the articles based on their content, 853 articles were retained as the primary data source for this study. This study follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). 19 The data charting process was conducted using standardized, calibrated forms tested by the research team. Data was charted independently by 2 researchers, with discrepancies resolved through discussion and confirmation with the original investigators. Below is the data collection workflow (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Workflow of data collection.

Results

Evaluation of Retrieved Data

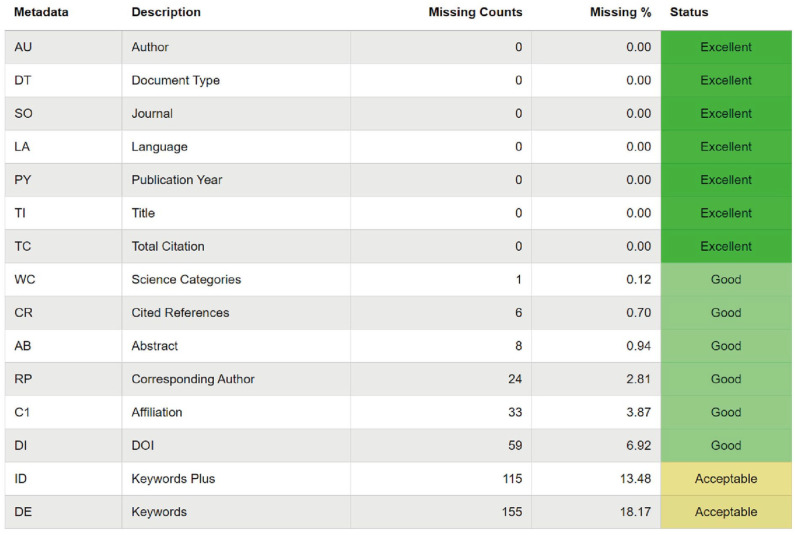

After filtering out 853 articles from WoS, they were exported as TXT format files. The exported content included the title, authors, publication year, keywords, and other relevant information. These files were then imported into Biblioshiny for in-depth analysis. During the analysis, the first step was to check the completeness of the information from the 853 articles. The results showed that data for “Author,” “Document Type,” “Journal,” “Language,” “Publication Year,” “Title,” and “Total Citation” had no missing values. Data for “Science Categories,” “Cited Reference,” “Abstract,” “Corresponding Author,” “Affiliation,” and “DOI” had less than 10% missing, and the data status was considered “good.” However, “Keywords” and “Keywords Plus” had more than 10% but less than 20% missing data, and their status was rated as “acceptable” (Figure 2). Upon further inspection, it was discovered that the missing data for “Keywords” and “Keywords Plus” was mainly due to these articles being published before 2000. The likely cause was that some information from these earlier articles had not been entered into the WoS database. Overall, the retrieval results were satisfactory, and the missing data remained within an acceptable range.

Figure 2.

Completeness of bibliographic metadata—853 documents from lsi.

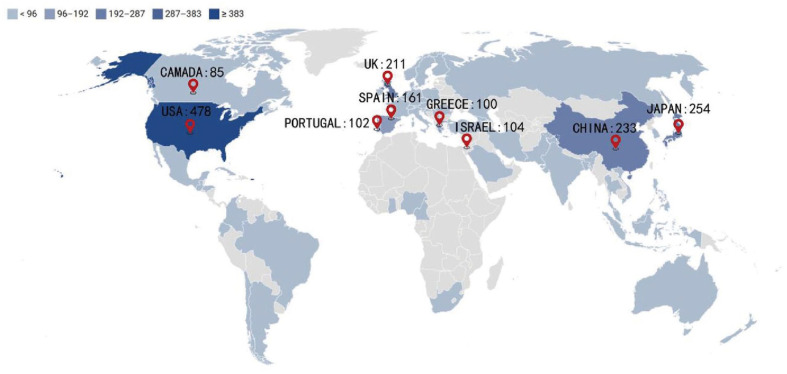

Active Countries Analysis

The analysis of countries contributing to research on adult daycare centers highlights both their respective contributions and the extensive network of international collaboration in this field. This study, using Biblioshiny software, examines the global scientific output on this topic, aiming to reveal the contributions of different countries as well as the scope and density of their international cooperation networks. The visualization map in Figure 3 clearly illustrates the distribution of authors’ affiliations by country for publications related to adult daycare centers. As of December 2023, 2603 countries have participated in research on this topic, with the majority located in the Americas, Asia, South America, and Oceania. The high level of participation from countries in these regions highlights the global concern surrounding older adult daycare. According to the data in Figure 3, the United States leads with 478 publications, significantly surpassing other countries, reflecting high scientific activity in this area. Japan and China follow closely with 254 and 233 publications, respectively, indicating strong research capabilities in Asia. The United Kingdom and Spain, with 211 and 161 publications respectively, further suggest that European countries also have a solid research foundation in adult daycare centers.

Figure 3.

Countries’ scientific production.

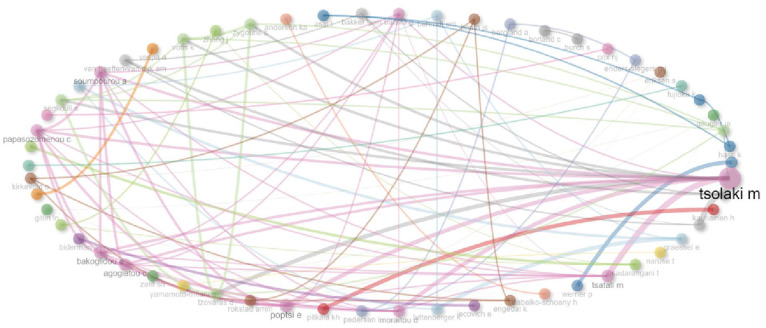

Leading Authors Analysis

Among the 835 relevant journal articles retrieved from the WoS database, authors from various countries and regions exhibit close collaborative relationships, forming an interconnected research network. Author collaboration refers to the process where multiple researchers jointly conduct studies, co-author academic papers, or contribute to shared scholarly outputs. 38 An author collaboration network provides a graphical representation of these relationships, highlighting patterns of academic cooperation. 39 Figure 4 presents the author collaboration network for research on adult daycare centers, where nodes represent authors and lines denote collaborative relationships. The thickness and color of the lines reflect the frequency and intensity of these collaborations. Notably, Tsolaki M emerges as a central node, demonstrating strong collaboration with Soumpourou A, Segkouli S, and Moraitou D. Similarly, Poptsi E is another prominent figure, frequently collaborating with multiple authors, suggesting a cohesive research cluster focused on older adult daycare studies.

Figure 4.

The authors’ collaboration network.

The research provides detailed information on the 10 most relevant authors in this field, as shown in Table 1. Each author’s full name was retrieved from the WoS expert database. The “Articles Fractionalized” column uses a fractional counting method to indicate each author’s contribution score per paper. The H-index, a key metric for assessing research influence, is a modern method for evaluating academic achievement. 40 The “H” in H-index stands for “high citations,” indicating the number of papers (H) a researcher has published that have been cited at least H times. 40 The author’s influence grows as the H-index increases. 40 In Table 1, the authors are ranked according to the number of relevant publications in the field. Cohen Mansfield Jiska having published a total of 15 academic articles in this field. The fractionalized value of her articles is 6.08, which is significantly higher than that of other scholars. This data shows that the author has a large number of publications and contributions in this field. Tsolaki Magdalini has published 14 articles in the field but has a fractionalized value of 1.71. She has a decent number of publications in the field, but her average contribution is not high. The above study helps scholars to quickly identify the most influential authors in their field of study. The fractionalized value of her articles is 6.08, which is significantly higher than that of other scholars. This data shows that the author has a large number of publications and contributions in this field. Tsolaki Magdalini has published 14 articles in the field but has a fractionalized value of 1.71. She has a decent number of publications in the field, but her average contribution is not high. The above study helps scholars to quickly identify the most influential authors in their field of study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Top 10 Most Highly Cited Documents in Adult Daycare Centers.

| Characteristics of the top 10 most highly cited documents in adult daycare centers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranking | Authors | Country/Region | Related articles | Related articles fractionalized | Total publication | Total citations | H-index |

| First | Cohen-Mansfield, Jiska | Israel | 15 | 6.08 | 316 | 16 514 | 59 |

| Second | Tsolaki, Magdalini | Greece | 14 | 1.71 | 594 | 33 440 | 85 |

| Third | Droes, Rose-Marie | Netherlands | 10 | 1.92 | 159 | 4704 | 38 |

| Fourth | Kautiainen, Hannu | Finland | 7 | 1.26 | 1060 | 22 517 | 72 |

| Fifth | Meiland, Franka JM | Netherlands | 7 | 1.3 | 62 | 1701 | 25 |

| Sixth | Ayalon, Liat | Israel | 6 | 4.5 | 367 | 8932 | 45 |

| Seventh | Graessel, Elmar | Germany | 6 | 1.12 | 83 | 1889 | 22 |

| Eighth | Takashi Naruse | Japan | 6 | 1.78 | 38 | 469 | 13 |

| Ninth | Sadarangani, Tina | USA | 6 | 1.24 | 44 | 181 | 8 |

| Tenth | Tsatali, Marianna | Greece | 6 | 0.86 | 31 | 451 | 8 |

Note. Related articles: refers to the papers published by the author in the Web of Science (WOS) database on the topic of adult daycare centers.

While strong author collaboration suggests knowledge-sharing and intellectual exchange, the network also reveals potential limitations. The high concentration of collaborations among a few key researchers may indicate a dominance of certain academic groups, potentially leading to thematic biases in the field. Additionally, limited cross-regional collaboration could hinder a truly global understanding of older adult daycare models, as research findings may be contextually specific rather than universally applicable. Future efforts should encourage broader international collaboration, integrating diverse perspectives and methodologies to enhance the generalizability and impact of older adult daycare research.

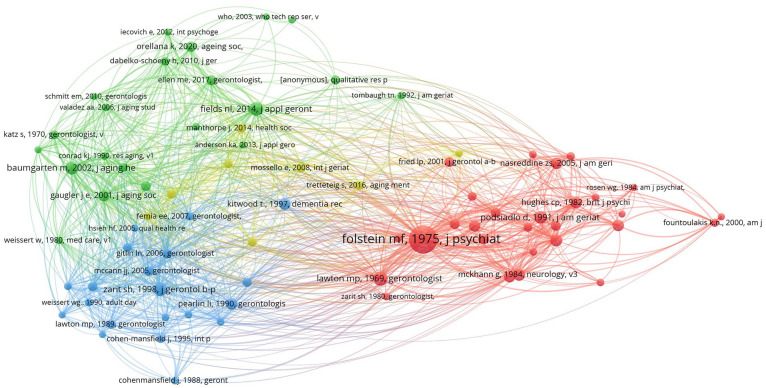

Reference Co-Citation Analysis

The co-citation analysis visualization in Figure 5 reveals distinct clusters of frequently co-cited references in adult daycare centers research. The red cluster, centered around Folstein MF, 41 indicates a strong focus on cognitive assessment tools, particularly the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which is widely used in dementia research. The blue and green clusters reflect a broader focus on older adult services and gerontological health studies, with key references including Fields NL and Zarit SH.42,43 While the network highlights foundational studies, the dominance of certain references suggests a continued reliance on established frameworks, which may limit methodological diversity. Additionally, research on adult daycare centers remains heavily dependent on early foundational works, with many key references dating back to the 1970s to 1990s. Although these early studies provide a solid theoretical foundation, the absence of more recent, highly co-cited works suggests that emerging research has yet to establish new widely recognized paradigms. Future studies should critically assess the continued applicability of existing frameworks and actively integrate new technologies and theoretical advancements to develop more comprehensive and innovative models for adult daycare centers.

Figure 5.

Reference co-citation analysis.

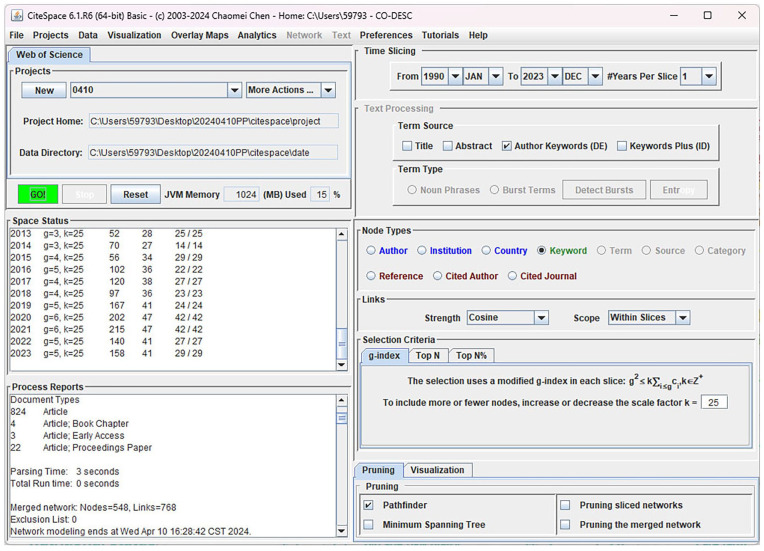

Keyword Clustering Analysis

CiteSpace is a literature analysis software developed by Professor Chaomei Chen.29,30 This study uses CiteSpace for keyword clustering, keyword mutation, and keyword trend analysis in related fields.A total of 853 publications from the WoS database were imported into the CiteSpace software, and the following settings were applied: (1) The “Time Slicing” option was set from January 1990 to December 2023, with the “time slices” interval set to 1. (2) “Author Keywords (DE)” was selected in the “Term Source” section, and “Keyword” was chosen in the “Node Types” section. (3) The “Pathfinder” option was selected in the “Pruning” section. Pathfinder is a network pruning technique that simplifies the knowledge network structure, resulting in a clearer and more concise visualization map. 30 After completing the above steps, clicking the “Visualize” button generates a knowledge map of the keywords from the relevant literature. This visual map helps researchers intuitively identify key nodes and structural relationships within the data, thereby revealing research themes, emerging trends, and the knowledge structure within a specific academic field (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

CiteSpace’s operating interface.

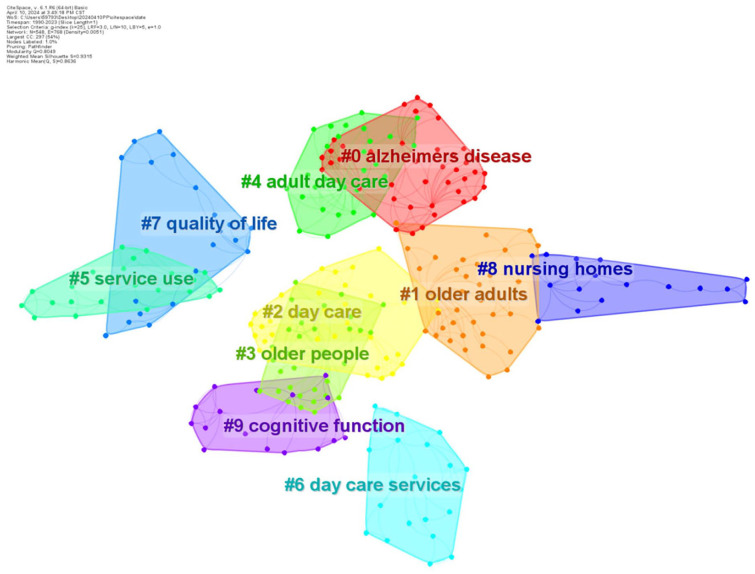

Figure 7 presents a keyword clustering analysis of adult daycare centers, revealing the main research themes and trends in this field. Each cluster represents a research theme related to adult community daycare, and they are marked with different colors and numbers in the figure. The 10 cluster themes identified can be grouped into 2 major modules: the “Older Adult Disease and Health” module (Cluster #0, Cluster #1, Cluster #3, Cluster #7, and Cluster #9) and the “Older Adult Care and Services” module (Cluster #2, Cluster #4, Cluster #5, Cluster #6, and Cluster #8). The “Older Adult Disease and Health” module primarily encompasses clusters related to the quality of life and health issues of the older adults population, such as “Alzheimer’s disease,” “older people,” “cognitive function,” and “quality of life.” The “Older Adult Care and Services” module focuses primarily on older adult daycare and care institutions, including “day care,” “nursing homes,” and “service use.” The formation of these 2 modules clearly illustrates that research in this field is primarily centered on 2 major aspects: older adults’ physical and mental health and older adult care services.

Figure 7.

CiteSpace’s Keyword cluster analysis.

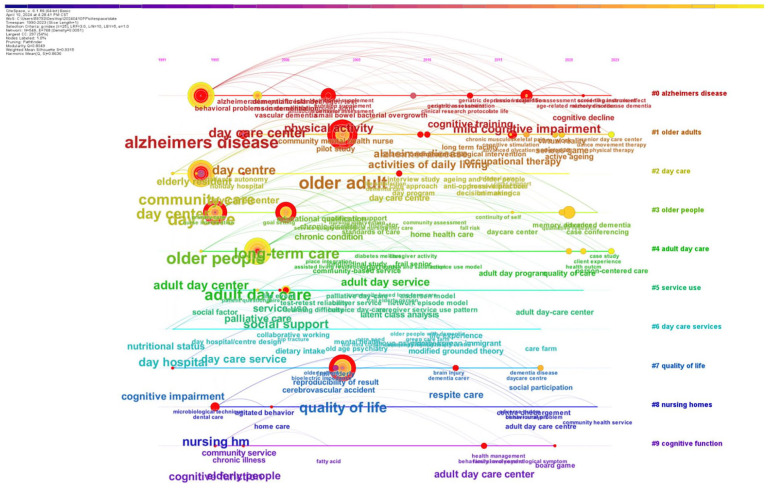

Figure 8 illustrates the evolution of keywords in the field of daycare centers from 1991 to 2023. The size of the nodes in the figure represents the frequency of keyword occurrences; the larger the node, the higher the keyword frequency. 30 The arcs connecting the keywords indicate co-occurrence relationships. 30 The combination of nodes and arcs effectively reveals research trends in the field. 30 In Figure 6, keywords such as “alzheimer’s disease,” “older adults,” and “day care” emerge as central topics of research in this field. The keyword timeline tracks allow researchers to understand the evolution of research trends over time. 30 From the timeline map in Figure 6, it is evident that “alzheimer’s disease” and “older adults” were early focal points of research. Research on “quality of life” and “day care” has been steadily increasing, reflecting the varied needs of older adults in terms of physical and mental health, social support, and long-term care services.

Figure 8.

CiteSpace’s Keyword timeline analysis.

Keyword Citation Burst Analysis

Keyword citation highlighting is used to analyze research trends that have exploded in a short period of time. 29 Figure 9 presents the top 50 most popular keywords in the field of daycare centers research from 1990 to 2023, along with the time periods of their bursts. These keywords reveal that earlier research in this field primarily focused on medical and nursing personnel. From 1990 to 2010, keyword hotspots mainly included “day hospital,” “nutritional status,” “cerebrovascular accident,” “disabled older adults,” and “caregiver burden,” indicating that during this period, researchers were primarily interested in studying physical illnesses among the older adults. From 2010 to 2020, research shifted toward cognitive health, home care, and quality of life for older adults. Keywords such as “Alzheimer’s disease,” “home health care,” and “cognitive function” exhibited explosive growth during this time. Between 2020 and 2023, studies focused on “long-term care,” “quality of life,” “active ageing,” and “older people,” reflecting an increased emphasis on health management and the quality of life for the older adults.

Figure 9.

CiteSpace’s Keyword citation burst analysis.

Keyword Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

VOSviewer is a user-friendly visualization tool for analyzing scientific literature, characterized by its simple interface and ease of operation. 27 It can process data from literature databases (eg, Web of Science, Scopus, CNKI, etc.), and at the same time can help researchers visualize and analyze literature in a certain field, such as Co-citation Analysis, Co-occurrence Analysis, Citation Network Analysis, Author and Institution Analysis, etc. 28 This study uses VOSviewer to conduct a keyword co-occurrence analysis of literature related to adult daycare centers. First, the pre-filtered literature is imported into VOSviewer. In the “Choose threshold” interface, the minimum number of keyword occurrences is set to 8. The prompt below indicates that out of 3160 keywords, 166 meet this threshold (Figure 10). Based on these settings, VOSviewer extracts the keywords that meet the criteria from the imported data and constructs a co-occurrence network and keyword nodes. Through the visualized network generated by VOSviewer, researchers can systematically analyze the knowledge structure within large-scale literature data, revealing key themes and development trends in the research field.

Figure 10.

VOSviewer’s operating interface.

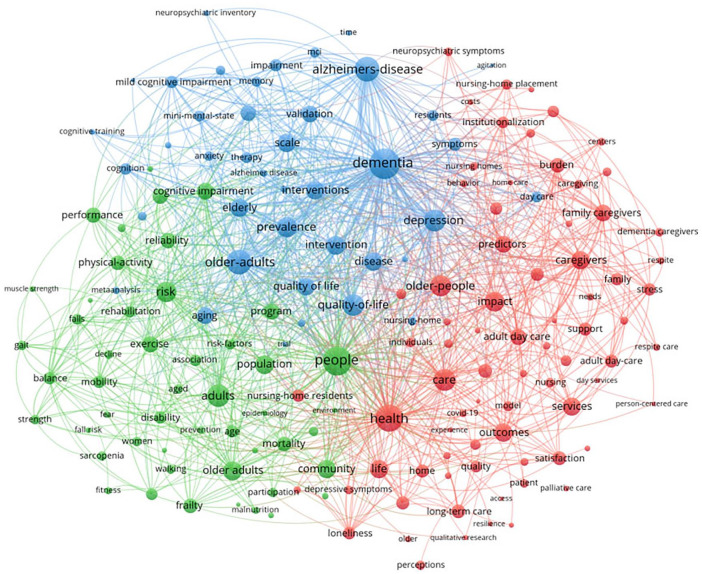

Figure 11, generated using VOSviewer, presents the keyword co-occurrence network, which depicts keyword relationships and clusters in the field of older adult health, care, and related research. In the visualization, the size of the nodes and the number of connections intuitively reflect the significance of each keyword. 27 Blue cluster focusing on keywords such as “Alzheimer’s disease,” “dementia,” and “cognitive impairment.” This indicates that research in this area emphasizes neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive decline in the older adults. Keywords in the green cluster are primarily related to “disability,” “physical activity,” and “exercise,” highlighting the attention given to the physical health and rehabilitation of the older adults in this field. In the red cluster, “care,” “caregivers,” and “adult day care” are the main keywords, reflecting scholars’ concern for aged care services and social support.The main keywords from these 3 clusters indicate that research in this field primarily focuses on 3 areas: “neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive impairment,” “physical health and rehabilitation of the older adults,” and “older adult care services and social support.” Therefore, the detailed exploration of these areas is considered crucial for optimizing older adult health management and improving their quality of life.

Figure 11.

VOSviewer’s keyword co-occurrence network analysis.

By further analyzing the keyword information in Figure 11, Table 2 has been constructed. After a careful review, the keywords were classified into 3 main themes: physical and mental diseases of the older adults (blue cluster), rehabilitation care for the older adults (green cluster), and social support for the older adults (red cluster) :

Table 2.

Main topics based on cluster analysis.

| Clusters | Keywords | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Blue cluster | Dementia, alzheimers-disease, neuropsychiatric inventory, alzheimer disease, cognitive impairment, memory, depression, anxiety, therapy, scale, mini-mental-state, interventions, validation, cognition, cognitive training, elderly, prevalence, intervention, older-adults, quality of life | Physical and mental diseases of the older adults |

| Green cluster | People, population, adults, older adults, aged, risk, physical-activity, rehabilitation, falls, gait, decline, exercise, decline, balance, strength, fear, disability, prevention, age, sarcopenia, walking, fitness, frailty, malnutrition, environment, community, participation, fall risk, rick-factors, association, reliability, performance | Rehabilitation care of the older adults |

| Red cluster | Health, older-people, care, long-tern-care, caregivers, family caregivers, dementia caregivers, adult day care, day services, day care, person-centered care, nursing, respite care, palliative care, neuropsychiatric symptoms, agitation, life, loneliness, resilience, home, family, patient, services, support, individuals, needs, stress, respite, behavior, burden, impact, nursing homes, nursing-home placement, centers, institutionalization, costs, covid-19, qualitative research, perceptions, access, quality, satisfaction, experience, outcomes, model | Social support of the older adults |

1) Physical and Mental Diseases (Blue Cluster). Keywords such as “dementia,” “Alzheimer’s disease,” “cognitive impairment,” “depression,” and “anxiety” highlight the prevalence of neurodegenerative and mental health disorders among older adults.44 -46 While research extensively covers Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline, there is a lack of studies integrating these conditions into older adults daycare facility design. Additionally, the cluster underscores the psychological challenges faced by older adults,47 -49 yet research remains largely focused on clinical interventions rather than environmental or social strategies for mental well-being.

2) Rehabilitation Care (Green Cluster). This theme emphasizes fall prevention, physical exercise, and community-based care, with keywords such as “risk,” “rehabilitation,” “falls,” “exercise,” and “sarcopenia.” Although research supports the role of exercise in maintaining physical function, there is limited focus on how adult daycare centers can better facilitate rehabilitation.50 -52 Furthermore, the importance of community support is recognized,51,53 but studies often fail to propose specific architectural or environmental improvements to enhance mobility and independence.

3) Social Support (Red Cluster). Keywords such as “caregivers,” “family caregivers,” “stress,” “burden,” and “COVID-19” highlight the challenges faced by both older adults and their caregivers. While studies acknowledge the emotional and physical strain on caregivers, research often lacks practical solutions for reducing caregiver burden within daycare settings.54 -63 The emphasis on “quality of care,” “satisfaction,” and “qualitative research” reflects a growing interest in evaluating daycare services, yet comprehensive frameworks for assessing architectural and service quality remain underdeveloped.64 -67 Overall, this analysis reveals significant gaps in older adult daycare research. While extensive studies exist on diseases, rehabilitation, and social support, there is limited interdisciplinary research connecting healthcare, social care, and environmental design. Future research should integrate evidence-based facility improvements and person-centered care models to create more inclusive, supportive, and effective older adult daycare environments.

Discussion

By analyzing WoS publications on adult daycare centers, this study provides a macro-level interpretation of research trends over the past 3 decades. The geographic concentration of studies in North America, Asia, and Europe reflects both demographic shifts and academic priorities in these regions. Developed nations such as the U.S., the U.K., and Japan experienced rapid population aging in the late 20th century, prompting extensive research on older adult care. 68 In China, where the older adult population exceeded 7% in 2000, scholarly attention to older adult care facilities has grown significantly. 69 However, this regional focus raises concerns about research generalizability. While aging is a global issue, regions like Africa and South America remain significantly underrepresented, limiting insights into how daycare models function in diverse economic and cultural settings.

Cultural values also shape older adult care systems, particularly in Asia, where filial piety and family responsibility remain deeply ingrained. 70 Urbanization and socio-economic shifts are straining traditional caregiving models, driving the rise of daycare centers as an alternative care solution. 71 Despite this shift, existing research often focuses on policy frameworks rather than empirical evaluations of daycare effectiveness, leaving gaps in understanding care quality, accessibility, and user satisfaction. This study highlights uneven research coverage and thematic biases in older adult daycare research. Future studies should prioritize comparative analyses across regions, addressing sociocultural influences and policy effectiveness to develop globally adaptable, evidence-based daycare models.

Keywords are crucial in academic research, offering a quick and comprehensive overview of an article’s focus. Analyzing keyword trends in adult daycare center research reveals 3 dominant themes: “physical and mental diseases of the older adults,” “rehabilitation care,” and “social support.” Among these, physical and mental health conditions are a significant barrier to independent living and a central research focus. 72 Common issues such as Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive impairment, anxiety, and depression not only reduce the quality of life but also limit social participation.44,47,72 However, despite the growing attention to these conditions, there is a lack of research on how daycare centers can effectively integrate mental health interventions into their facility design and daily operations.

The increasing focus on older adult health issues has also driven research on rehabilitation care, essential for maintaining functionality and improving life quality. 73 Daycare centers offer rehabilitation and nursing services that alleviate the burden on home caregivers and medical institutions. 74 Keywords such as “exercise,” “prevention,” “rehabilitation,” and “malnutrition” highlight critical areas in rehabilitation, yet current studies tend to emphasize clinical interventions rather than the built environment’s role in facilitating recovery.73,75 Facility design should not only incorporate exercise spaces but also ensure barrier-free accessibility, proper nutrition, and routine health monitoring. 76 Moreover, the architectural layout should prioritize fall prevention and minimize injury risks, yet few studies provide evidence-based design recommendations for these aspects. 75

Social support has also emerged as a key research focus, reflecting its role in complementing family-based and institutional eldercare models. While daycare centers reduce caregiver burden, research suggests that caregivers themselves experience high levels of physical and emotional strain, including grief, family resistance, and workplace stress.10,77 Despite the prevalence of these issues, limited studies explore caregiver well-being from a spatial and operational perspective, leaving gaps in optimizing facility design for both caregivers and older adult users.77,78 Additionally, the presence of keywords such as “qualitative research,” “interviews,” and “satisfaction” indicates a growing interest in care service evaluation. While these evaluations help match services to user needs, most studies focus on care quality rather than the built environment’s influence on user satisfaction and operational efficiency.65,66 Future research should integrate both qualitative and architectural evaluations to develop a comprehensive framework for older adult daycare center design, ensuring that facilities meet the needs of both the older adults and caregivers.

In conclusion, the themes of “physical and mental diseases,” “rehabilitation care,” and “social support” form the core of older adult daycare research, shaping the understanding of target groups, care services, and social support systems. While these themes dominate the field, significant gaps remain in design optimization and facility configuration. Current studies largely focus on care services rather than a systematic evaluation of architectural design, functional layouts, and user experiences. The absence of a holistic evaluation framework limits advancements in evidence-based daycare center design. Although this study conducted a systematic bibliometric analysis of research trends, hotspots, and gaps in adult daycare centers based on the Web of Science database, certain limitations remain. This study relied solely on the Web of Science database, which may have resulted in the omission of relevant studies from other databases, affecting the comprehensiveness of the research. Additionally, since the search was limited to English-language publications, research from non-English-speaking countries may not have been adequately covered. Given that cultural contexts significantly influence the development models of adult daycare centers, this limitation may introduce bias. Future research should integrate multiple databases and include multilingual literature further to enhance the comprehensiveness and applicability of the findings.

Conclusion

This study utilizes literature visualization to clearly present the current research hotspots, trends, and gaps in adult daycare centers. The findings highlight 3 key aspects for improving the design and facilities of these centers. (1) Addressing the physical and psychological needs of the older adults. This includes not only providing spaces that support mobility, safety, and comfort but also ensuring areas for psychological well-being and mental health support. (2) Enhancing rehabilitative care facilities. This involves improving rehabilitation training facilities, optimizing the dietary environment, and providing accessible infrastructure. (3) Focusing on the needs of caregivers. A well-designed working and learning environment for caregivers is fundamental to the smooth operation of adult daycare centers. In conclusion, this study not only maps existing research trends but also identifies research gaps in this field. By addressing these gaps, future researchers can contribute to the theoretical development, improvement, and standardization of architectural design and facilities in adult daycare centers. To address these gaps, policymakers and professionals should prioritize developing a comprehensive, evidence-based evaluation framework for the architectural design and facilities of adult daycare centers. Integrating these findings into future policies and design practices will help create more inclusive, functional, and sustainable daycare environments that effectively meet the needs of an aging population.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Mr. Jiaqi Liu for his invaluable assistance with the use of the software, which significantly enhanced the analysis and visualization of this study.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Zeqin Wu  https://orcid.org/0009-0005-7084-8730

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-7084-8730

Raha Sulaiman  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5183-7407

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5183-7407

Author Contributions: Zeqin Wu—Responsible for writing the manuscript.

Raha Sulaiman—Provided guidance and revisions to the manuscript, acting as the primary contact for correspondence.

Yahaya Ahmad—Contributed to reviewing, suggesting improvements, and revising the manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement: The data used in this study were obtained from publicly available databases, primarily Web of Science. All data can be accessed through institutional or individual subscriptions to these databases.

References

- 1. Oster C, Kibat WH. Evaluation of a multidisciplinary care program for stroke patients in a day care center. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(2):63-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou Y, Fu J. Review of Studies on Day-Care centers for the elderly in community. Open J Soc Sci. 2019;07(12):322-334. doi: 10.4236/jss.2019.712024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilliam WS, Malik AA, Shafiq M, et al. COVID-19 transmission in US child care programs. Pediatrics. 2021;147(1): 1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jordan HT, Calderon M, Pichardo C, Ahuja SD. Tuberculosis contact investigations conducted in New York City Adult Day Care and Senior Centers, 2011–2018. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(2):545-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iecovich E, Carmel S. Differences between users and nonusers of day care centers among frail older persons in Israel. J Appl Gerontol. 2011;30(4):443-462. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iecovich E, Biderman A. Attendance in adult day care centers and its relation to loneliness among frail older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(3):439-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen J, Zhu Y, Song Y, et al. Current situation and factors influencing elderly care in community day care centers: a cross-sectional study. Front Med. 2024;10: 1-9. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1251978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silverstein NM, Wong CM, Brueck KE. Adult day health care for participants with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dementias. 2010;25(3):276-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rokstad AMM, McCabe L, Robertson JM, Strandenæs MG, Tretteteig S, Vatne S. Day care for people with dementia: a qualitative study comparing experiences from Norway and Scotland. Dementia. 2019;18(4):1393-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. You N. Identifying the potential location of day care centers for the elderly in Tokyo: an integrated framework. Appl Spat Anal Policy. 2020;13(3):591-608. doi: 10.1007/s12061-019-09319-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Noor S, Isa FM, Hossain MS, Shafiq A. Ageing care centers: mediating role of quality care and proactive environment. J Popul Soc Stud. 2020;28(4):324-347. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ron P. Self-esteem among elderly people receiving care insurance at home and at day centers for the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(6):1097-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Melo RCCPD, Costa PJ, Henriques LVL, Tanaka LH, Queirós PJP, Araújo JP. Humanitude in the humanization of elderly care: experience reports in a health service. Rev Bras Enferm. 2019;72(3):825-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tretteteig S, Vatne S, Rokstad AM. The influence of day care centres designed for people with dementia on family caregivers–a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lunt C, Dowrick C, Lloyd-Williams M. The role of day care in supporting older people living with long-term conditions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2018;12(4):510-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ayalon L. Sense of belonging to the community in continuing care retirement communities and adult day care centers: the role of the social network. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(2):437-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang M, Chen C, Du Y, Wang S, Rask M. Multidimensional factors affecting care needs in daily living among community-dwelling older adults: a structural equation modelling approach. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(5):1207-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shao Q, Yuan J, Lin J, Huang W, Ma J, Ding H. A SBM-DEA based performance evaluation and optimization for social organizations participating in community and home-based elderly care services. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018/October/02;169(7):467-473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Godin B. On the origins of bibliometrics. Scientometrics. 2006;68(1):109-133. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rostaing H. La bibliométrie et ses techniques. Sciences de la Société; Centre de Recherche Rétrospective de Marseille; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lotka A. The frequency distribution of scientific productivity. J Franklin Inst. 1926;16(12):271-323. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zipf GK. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort: An Introduction to Human Ecology. Ravenio Books; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Price D. Networks of scientific papers: the pattern of bibliographic references indicates the nature of the scientific research front. Science. 1965;149(3683):510-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stuart D. Open bibliometrics and undiscovered public knowledge. Online Inform Rev. 2018;42(3):412-418. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jaradat Y, Alia M, Masoud M, et al. A bibliometric analysis of the. Int J Adv Soft Comput Appl. 2022;14(2):186-184. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maliha H. A review on bibliometric application software. Scientometr Letter. 2023;1(1).. [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. 2010;84(2):523-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen C. CiteSpace: A Practical Guide for Mapping Scientific Literature. Nova Science Publishers; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen C, Song M. Visualizing a field of research: a methodology of systematic scientometric reviews. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen C. Visualizing and Exploring Scientific Literature With Citespace: An Introduction. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Human Information Interaction & Retrieval (CHIIR ‘18), New Brunswick, NJ, March 11-15, 2018, Association for Computing Machinery; 2018:369-370. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aria M, Cuccurullo C. Bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informetr. 2017;11(4):959-975. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Büyükkıdık S. A bibliometric analysis: a tutorial for the bibliometrix package in R using IRT literature. J Meas Eval Educ Psychol. 2022;13(3):164-193. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Caputo A, Kargina M. A user-friendly method to merge Scopus and Web of Science data during bibliometric analysis. J Market Analyt. 2022;10(1):82-88. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ab Rashid MF. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis using R packages: a comprehensive guidelines. J Tour Hosp Culinar Arts. 2023;15(1):24-39. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chadegani AA, Salehi H, Yunus MM, et al. A comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of Science and Scopus databases. Asian Soc Sci. 2013;9(5): 18-26. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ali PA, Watson R. Peer review and the publication process. Nurs Open. 2016;3(4):193-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Julpisit A, Esichaikul V. A collaborative system to improve knowledge sharing in scientific research projects. Inform Dev. 2019;35(4):624-638. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Polyakov M, Polyakov S, Iftekhar MS. Does academic collaboration equally benefit impact of research across topics? The case of agricultural, resource, environmental and ecological economics. Scientometrics. 2017;113(3):1385-1405. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xu L, Yang Q, Xu Q. H-type indices with applications in chemometrics I: h-multiple similarity index. J Chemometr. 2021;35(9):e3365. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fields NL, Anderson KA, Dabelko-Schoeny H. The effectiveness of adult day services for older adults: a review of the literature from 2000 to 2011. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33(2):130-163. doi: 10.1177/0733464812443308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zarit SH, Stephens MAP, Townsend A, Greene R. Stress reduction for family caregivers: effects of adult day care use. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(5):S267-S277. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.5.s267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Keramat SA, Lee V, Patel R, Hashmi R, Comans T. Cognitive impairment and health-related quality of life amongst older Australians: evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Qual Life Res. 2023;32(10):2911-2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang M, Ho E, Nowinski CJ, et al. The paradox in positive and negative aspects of emotional functioning among older adults with early stages of cognitive impairment. J Aging Health. 2024;36(7-8):471-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Qiu Z, Cai J, Xia F. Correlation between the degree of cognitive impairment and emotional state in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Investigación Clínica. 2024;65(1):37-47. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sari NPWP, Manungkalit M. The best predictor of anxiety, stress, and depression among institutionalized elderly. Int J Public Health Science. 2019;8(4):419-426. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Manungkalit M, Sari NPWP. The influence of anxiety and stress toward depression in institutionalized elderly. J Educ Health Commun Psychol. 2020;9(1):65-76. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Suwal RP, Upadhyay B, Chalise HN. Factors associated with anxiety and depression among elderly living in old age homes. KMC J. 2024;6(1):280-299. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cadore EL, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Sinclair A, Izquierdo M. Effects of different exercise interventions on risk of falls, gait ability, and balance in physically frail older adults: a systematic review. Rejuvenat Res. 2013;16(2):105-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Okubo Y, Osuka Y, Jung S, et al. Effects of walking on physical and psychological fall-related factors in community-dwelling older adults: walking versus balance program. J Phys Fitness Sports Med. 2014;3(5):515-524. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dipietro L, Campbell WW, Buchner DM, et al. Physical activity, injurious falls, and physical function in aging: an umbrella review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kwan I, Rutter D, Anderson B, Stansfield C. Personal care and practical support at home: a systematic review of older people’s views and experiences. Work Old People. 2019;23(2):87-106. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim S, Sok SR. Relationships among the perceived health status, family support and life satisfaction of older Korean adults. Int J Nurs Pract. 2012;18(4):325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dai J, Liu Y, Zhang X, Wang Z, Yang Y. A study on the influence of community spiritual comfort service on the mental health of older people. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1137623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shamsikhani S, Ahmadi F, Kazemnejad A, Vaismoradi M. Typology of family support in home care for Iranian older people: a qualitative study. Int J Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vasara P, Simola A, Olakivi A. The trouble with vulnerability. Narrating ageing during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Aging Stud. 2023;64:101106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu E, Dean CA, Elder KT. The impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable populations. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1267723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Alam MS, Sultana R, Haque MA. Vulnerabilities of older adults and mitigation measures to address COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: a review. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2022;6(1):100336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee YJ. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vulnerable older adults in the United States. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2020;63(6-7):559-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Calderón-Larrañaga A, Dekhtyar S, Vetrano DL, Bellander T, Fratiglioni L. COVID-19: risk accumulation among biologically and socially vulnerable older populations. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;63:101149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang J, Wu B, Bowers BJ, et al. Person-centered dementia care in China: a bilingual literature review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2019;5:2333721419844349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Boggatz T. Quality of Life and Person-Centered Care for Older People. Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Moore K. Quality of care for frail older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(9):1255-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Berglund H, Gustafsson S, Ottenvall Hammar I, Faronbi J, Dahlin-Ivanoff S. Effect of a care process programme on frail older people’s life satisfaction. Nurs Open. 2019;6(3):1097-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Patel AB. Challenges faced by older people in a district of Uttar Pradesh: a qualitative study. J Adult Protect. 2021;23(4):263-276. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vitman-Schorr A, Ayalon L. Older adults’ mental maps of their spatial environment: exploring differences in attachment to the environment between participants in adult day care centers in rural and urban environments. J Hous Built Environ. 2020;35(4):1037-1054. doi: 10.1007/s10901-020-09737-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gu D, Andreev K, Dupre ME. Major trends in population growth around the world. China CDC Weekly. 2021;3(28):604-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Peng X. China’s demographic history and future challenges. Science. 2011;333(6042):581-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zi Y, Chengcheng SJ. Gender role attitudes and values toward caring for older adults in contemporary China, Japan, and South Korea. J Asian Sociol. 2021;50(3):431-464. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fang EF, Xie C, Schenkel JA, et al. A research agenda for ageing in China in the 21st century: focusing on basic and translational research, long-term care, policy and social networks. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;64:101174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tornero-Quiñones I, Sáez-Padilla J, Espina Díaz A, Abad Robles MT, Sierra Robles Á. Functional ability, frailty and risk of falls in the elderly: relations with autonomy in daily living. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Othman LB, Shan TP, Abd Hamid B, Rahman A, Sciences H. Restorative care for older adults to age gracefully. Malays J Med Health Sci. 2022;18:111. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Aronoff-Spencer E, Asgari P, Finlayson TL, et al. A comprehensive assessment for community-based, person-centered care for older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bonaccorsi G, Manzi F, Del Riccio M, et al. Impact of the built environment and the neighborhood in promoting the physical activity and the healthy aging in older people: an umbrella review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ko AJ, Kim J, Park E-C, Ha MJ. Association between the utilization of senior centers and participation in health check-ups. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):11518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kazaki S, Christodoulakis A, Tsiligianni I, et al. Health-related issues of users of social care services for elderly and their caregivers: a cross-sectional study in a day care center. Curr Health Sci J. 2024;50(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Montejano-Lozoya R, Alcañiz-Garrán MDM, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Sánchez-Alcón M, García-Sanjuan S, Sanjuán-Quiles Á. Affective impact on informal caregivers over 70 years of age: a qualitative study. Healthcare. 2024;12(3):329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]