Abstract

Anthrax is a zoonotic disease that is also well recognized as a potential agent of bioterrorism. Routine culture and biochemical testing methods are useful for the identification of Bacillus anthracis, but a definitive identification may take 24 to 48 h or longer and may require that specimens be referred to another laboratory. Virulent isolates of B. anthracis contain two plasmids (pX01 and pX02) with unique targets that allow the rapid and specific identification of B. anthracis by PCR. We developed a rapid-cycle real-time PCR detection assay for B. anthracis that utilizes the LightCycler instrument (LightCycler Bacillus anthracis kit; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.). PCR primers and probes were designed to identify gene sequences specific for both the protective antigen (plasmid pX01) and the encapsulation B protein (plasmid pX02). The assays (amplification and probe confirmation) can be completed in less than 1 h. The gene encoding the protective antigen (pagA) was detected in 29 of 29 virulent B. anthracis strains, and the gene encoding the capsular protein B (capB) was detected in 28 of 29 of the same strains. Three avirulent strains containing only pX01 or pX02, and therefore only pagA or pagB genes, could be detected and differentiated from virulent strains. The assays were specific for B. anthracis: the results were negative for 57 bacterial strains representing a broad range of organisms, including Bacillus species other than anthracis (n = 31) and other non-Bacillus species (n = 26). The analytical sensitivity demonstrated with target DNA cloned into control plasmids was 1 copy per μl of sample. The LightCycler Bacillus anthracis assay appears to be a suitable method for rapid identification of cultured isolates of B. anthracis. Additional clinical studies are required to determine the usefulness of this test for the rapid identification of B. anthracis directly from human specimens.

Bacillus anthracis is a spore-forming gram-positive bacillus that causes the disease anthrax in animals and humans. Infection in humans is extremely rare in the developed world and is generally due to contact with infected animals or contaminated animal products. Humans may contract the disease via three routes: cutaneous inoculation via a cut or abrasion, ingestion of contaminated meat, or inhalation of spores. In naturally acquired infections, the cutaneous mode of transmission is by far the most common, accounting for approximately 95% of infections in the United States (6). Death is uncommon in cases of cutaneous anthrax, but not uncommon in gastrointestinal or inhalation anthrax (7, 11, 13, 20, 21).

B. anthracis is easily cultivated in its vegetative (bacillary) form with conventional growth media. Sporulation can be achieved by using nutrient-deficient media. Because of their relatively small size (less than 5 μm), spores may be easily inhaled into the lower respiratory tract in humans (11, 20). This ease of cultivation, coupled with the hardy nature of its spores and the high mortality associated with inhalation anthrax, makes B. anthracis a potential biological warfare agent. Concern about the use of anthrax as an agent of bioterrorism and a weapon of mass destruction has increased due to the recent deliberate dissemination of anthrax spores in United States and the resulting inhalational and cutaneous infections. To ensure that patients infected with B. anthracis are treated as rapidly as possible, tests that rapidly identify the organism in culture, clinical specimens, and environmental samples are essential.

Culture represents the “gold standard” for identification of B. anthracis. A definitive identification of isolated colonies as B. anthracis may take 24 to 48 h or more and requires specialized testing, including direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) staining of capsule and cell wall polysaccharide and lysis of colonies by gamma phage. These confirmatory tests are not generally available in clinical microbiology laboratories in the United States, except at higher-level public health laboratories, which are part of the Laboratory Response Network established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Ga. (17).

B. anthracis and other members of the Bacillus cereus group exhibit an extremely high degree of genomic homology (1, 9), making differentiation by PCR challenging. However, virulent isolates of B. anthracis contain two plasmids, pX01 and pX02, with unique virulence gene targets that allow the rapid identification of B. anthracis by PCR. Several conventional PCR assays have been described for the identification of B. anthracis (2-4, 16, 18, 19). These assays are time-consuming and labor-intensive, requiring a separate step after PCR for confirmation of product. These assays have been constructed to identify a gene target on a single plasmid (4, 16, 19) or both plasmids (2, 18) and use conventional PCR and product detection formats.

Rapid-cycle real-time PCR represents a significant advance in PCR testing (5). Real-time PCR instruments have built-in thermocyclers and fluorimeters, which permit rapid PCR cycling and simultaneous detection of amplification product. Furthermore, PCR and product detection are performed in the same closed reaction vessel, which considerably lessens the chance for contamination. A first-generation real-time PCR platform, which uses the fluorogenic probe-based assay TaqMan 5′ nuclease assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), has been developed to detect a variety of biothreat agents, including anthrax (10). In our experience, this type of assay requires approximately 2 h to complete, and unlike newer real-time PCR platforms, information on product detection is not available to the technologist until all PCR cycles are completed (5).

Second-generation real-time PCR assays offer faster thermocycling, and information on product detection is available to the technologist with each PCR cycle. Assays using second-generation real-time PCR instrumentation (LightCycler; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.) have been developed, which detect the capB gene (plasmid pX02) (14) or both the capB and the pagA genes (plasmid pX01) (15). The first of these assays uses SYBR Gold and the second uses SYBR Green as fluorescent indicators of the amplification product. However, SYBR Gold and SYBR Green are dyes that will intercalate between any double-stranded DNA structure, and therefore specific product detection cannot be ensured.

Plasmids pX01 and pX02 have been completely sequenced, although the functions of many of the genes on these plasmids are not yet known. However, three proteins encoded by genes on plasmid pX01 have long been recognized as important contributors to B. anthracis pathogenicity. The three proteins are the protective antigen (pagA gene), edema factor (cya gene), and lethal factor (lef gene), and together the genes coding for these proteins encode the toxin complex. The protective antigen combines with both lethal factor and edema factor to produce binary toxins, and it is the protective antigen that allows the toxin complexes to bind to host cells for toxin delivery (8). The capB gene is one of three genes (capA, capB, and capC) on plasmid pX02 that are necessary for biosynthesis of the protective polypeptide capsule (8).

A rapid assay that identifies gene targets on both virulence plasmids (pX01 and pX02) is preferred, because B. anthracis strains can lack either plasmid. Vaccine strains, with reduced virulence in humans, may be used in biocrime hoaxes. These strains lack either virulence plasmid, and so identification of these strains in the setting of a potential biocrime is important to prevent undue anxiety and inappropriate treatment of exposed individuals. Likewise, rapid identification of virulent B. anthracis strains is especially important, since systemic disease may not be detected early enough by conventional techniques to allow sufficient time to begin effective antibiotic therapy. The high mortality associated with inhalation anthrax is thought to be due in large part to a delay in diagnosis (20). Recent cases of inhalation anthrax in the United States have demonstrated that mortality rates may be greatly reduced and patients can make a full recovery provided the infection is promptly diagnosed and appropriate antibiotic treatment is initiated in a timely manner (12).

This study presents the development and evaluation of a rapid-cycle real-time PCR assay, which uses the LightCycler instrument and the LightCycler Bacillus anthracis kit (Roche Applied Science) for the identification of B. anthracis. The assay identifies the protective antigen (pagA) gene from plasmid pX01 and the encapsulation B (capB) gene from plasmid pX02. LightCycler technology permits rapid PCR cycling with real-time fluorescent resonance energy (FRET) probe detection of product. Amplification and probe confirmation of product can be performed in the same closed reaction vessel and completed in less than 1 h. The assay was validated for use as a rapid method for identification of cultured isolates of B. anthracis. A bank of archived strains of B. anthracis, Bacillus spp. other than B. anthracis, and non-Bacillus bacteria were evaluated by this method.

(This study was presented in part at the 101st General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Orlando, Fla., 20 to 24 May 2001.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Thirty-one strains of B. anthracis, 31 strains of Bacillus spp. other than B. anthracis, and 26 strains of bacteria from genera other than Bacillus and including other potential bioterrorism agents were evaluated (Tables 1 and 2). Phenotypic culture-based identification and, in some cases, genotypic identification of these bacterial strains were performed previously either at the Mayo Clinic or the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP). Genotyping of strains by determination of the presence of either the pagA gene (plasmid pX01) or the capA gene (plasmid pX02) was previously performed at the AFIP for B. anthracis strains (Table 1). Fresh isolates of archived strains were used for nucleic acid extraction and subsequent evaluation by the LightCycler assay.

TABLE 1.

B. anthracis isolates tested for presence of pagA (plasmid pX01) and capB (plasmid pX02)

| Isolate | pX01/pX02 | LightCycler assay result

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| pagA | capB | ||

| Ames | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| BC3132 | pX01−/pX02+ | − | + |

| delta-Ames | pX01−/pX02+ | − | + |

| GT3 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT10 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT15 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT20 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT23 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT25 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | −a |

| GT28 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT29 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT30 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT34 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT35 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT38 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT41 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT45 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT51 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT55 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT57 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT62 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT68 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT69 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT77 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT80 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT85 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| GT87 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| Mayo 1 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| SD96-1-355 | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| Sterne | pX01+/pX02− | + | − |

| Vollum | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

| Zimbabwe | pX01+/pX02+ | + | + |

Initial genotyping of this strain at the AFIP showed the presence of the capA gene. Subsequent testing in the present study did not reveal the presence of the capB gene, suggesting that the plasmid pX02 was lost by the organism. This was confirmed, because PCR assays for all encapsulation genes (capA, capB, and capC) were negative.

TABLE 2.

Other organisms tested for the presence of pagA (plasmid pX01) and capB (plasmid pX02)

| Organism | No. of isolates tested | LightCycler assay result

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| pagA | capB | ||

| Bacillus cereus | 8 | − | − |

| Bacillus circulans | 2 | − | − |

| Bacillus globigii | 1 | − | − |

| Bacillus laterosporus | 1 | − | − |

| Bacillus megaterium | 3 | − | − |

| Bacillus mycoides | 1 | − | − |

| Bacillus niacini | 1 | − | − |

| Bacillus pumilus | 3 | − | − |

| Bacillus silvestris | 1 | − | − |

| Bacillus sphaericus | 1 | − | − |

| Bacillus subtilis | 4 | − | − |

| Bacillus thuringiensis | 4 | − | − |

| Bacillus thuringiensis serovar israeliensis | 1 | − | − |

| Brucella abortus | 1 | − | − |

| Brucella bovis | 1 | − | − |

| Brucella melitensis | 1 | − | − |

| Burkholderia mallei | 1 | − | − |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | 1 | − | − |

| Clostridium botulinum | 4 | − | − |

| Clostridium perfringens | 2 | − | − |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | 1 | − | − |

| Corynebacterium jeikeium | 1 | − | − |

| Deinococcus radiodurans | 1 | − | − |

| Francisella tularensis | 1 | − | − |

| Listeria innocua | 1 | − | − |

| Paenibacillus (Bacillus) lautus | 3 | − | − |

| Paenibacillus (Bacillus) macerans | 1 | − | − |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2 | − | − |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus | 1 | − | − |

| Vibrio cholerae | 1 | − | − |

| Yersinia pestis | 2 | − | − |

Cultivation of bacterial strains.

B. anthracis strains were cultured on sheep blood agar plates and nutrient agar plates at 37°C. All B. anthracis strains were nonhemolytic, catalase-positive, nonmotile, gram-positive bacilli and were confirmed as B. anthracis by a DFA technique (CDC). Bacteria other than B. anthracis were identified by using the appropriate media, culturing conditions, and biochemical determinations.

DNA template preparation.

Template or “target” DNA for use in the PCRs was isolated from bacterial strains with the High Pure PCR template preparation kit (Roche Applied Science) or the MagNA Pure LC DNA isolation kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's directions.

PCR primers and probes.

Oligonucleotide primers for PCR were designed to amplify the desired gene products from pagA (GenBank accession no. M22589) and capB (GenBank accession no. M24150). FRET probes for each of these gene PCR products were labeled with fluorescein and LC (LightCycler)-Red640. These PCR primers and FRET probes for pagA and capB are available as analyte-specific reagents through Roche Applied Science (LightCycler Bacillus anthracis detection kit; catalog no. 33 03 411).

Control DNA.

The positive control DNAs for pagA and capB are plasmid constructs containing a portion of these target genes. These controls are available as part of the LightCycler Bacillus anthracis detection kit.

LightCycler PCR.

PCR amplification and product detection for all bacterial strains were performed with the Roche LightCycler Bacillus anthracis detection kit and the LightCycler instrument.

The assays to detect pagA and capB were performed in separate cuvettes with FRET probe detection. For the assay, 5 μl of extracted sample or positive control DNA was added to 15 μl of the PCR mix in each reaction cuvette. The reaction conditions are identical for both gene targets, so the pagA and capB tests may be performed with the same run. Amplification was performed for 1 cycle as follows: 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s (denaturation), 55°C for 15 s (annealing), and 72°C for 12 s (primer extension).

Melting curve analysis.

Following the completion of the PCR amplification reaction, a melting curve analysis was performed (50 to 85°C) to confirm the product identification. The paired FRET hybridization probes are designed to anneal with unique segments of either the pagA or capB gene and provide characteristic Tm values.

Analytical sensitivity.

Dilutions of DNA were prepared and assayed to determine the analytical sensitivity of the assay. Dilutions that yielded 5 to 1,000,000 copies of the target DNA per reaction were tested.

RESULTS

Analytical sensitivity.

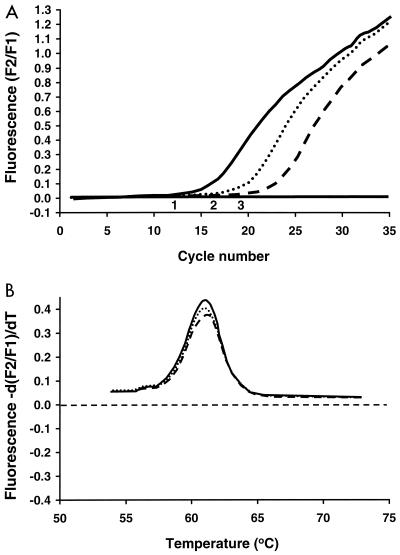

Five copies of the pagA and the capB target sequences per reaction (1 copy per μl of sample) were detectable. Representative cycling curves for samples tested for pagA are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

(A) Representative LightCycler assay for detection of the pagA gene by using FRET probes. Shown are the results from three samples. The solid line indicates a DNA preparation from a B. anthracis strain with a relatively high concentration of target DNA, the dotted line indicates a positive plasmid control, and the dashed line indicates a DNA preparation from another B. anthracis strain with a relatively low concentration of target DNA. (B) Confirmatory analysis (quality control step) by evaluation of melting curves. In this case, the negative derivative of fluorescence, −d(F2/F1), over the derivative of time, dT, is compared to temperature. F1 refers to the F1 channel of the LightCycler that detects the 530-nm light emitted by the fluorescein fluorophore. F2 refers to the F2 channel of the LightCycler that detects the 640-nm light emitted by the LC (LightCycler)-Red640 acceptor fluorophore. The same melting curve occurs for the two samples and the positive control shown in panel A, indicating that DNA with identical sequences has been amplified for each of the three samples.

Melting curve analysis.

Each amplification product for pagA and capB demonstrated a specific and characteristic melting curve. The Tms for the products generated were 61.5°C for pagA and 67.0°C for capB. Representative melting curves for samples tested for pagA are shown in Fig. 1.

Evaluation of bacterial strains.

Twenty-nine of the 32 B. anthracis strains evaluated in this study were considered virulent strains. These strains were shown previously to contain both the pagA and capA genes, indicating that both the pX01 and pX02 plasmids were present (Table 1). The LightCycler Bacillus anthracis assay detected the pagA gene target in all 29 of these B. anthracis strains, while the capB gene was detected in 28 of 29 of these strains (Table 1). The capB assay was repeated from the same DNA preparation for the one strain (GT25) for which the capB gene was not initially detected, and again the capB gene was not detected. To determine if a gene deletion had occurred in B. anthracis isolate GT25, seven PCR primer pairs were selected to amplify 325- to 492-bp fragments of the contiguous encapsulation protein genes, capA (1,236 bp), capC (450 bp), and capB (1,395 bp). Amplification of DNA was obtained from all seven PCRs with DNA extracted from B. anthracis strain BC3132 (pX02+), but not with DNA from isolate GT25. To determine if the DNA extracted from isolate GT25 is amplifiable, the pagA gene assay was repeated, and again the pagA gene was amplified. It was concluded that the B. anthracis GT25 isolate evaluated in the present study had lost all of the encapsulation (capA, capC, and capB) genes, implying that plasmid pX02 was also lost.

B. anthracis delta-Ames and BC3132 lack plasmid pX01, and therefore the pagA gene. The LightCycler assay detected the capB gene and not the pagA gene in these two strains. B. anthracis Sterne lacks plasmid pX02, and as expected, the LightCycler assay detected pagA, but not capB, in this strain.

Thirty-one strains of Bacillus spp. (other than B. anthracis) and 26 strains of other bacteria (genera other than Bacillus and including other potential agents of bioterrorism) were negative for both capB and pagA by the LightCycler assay (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Conventional culture-based methods are considered the gold standard for identification of B. anthracis. These manual testing methods are time-consuming, and confirmatory testing frequently requires referral of isolates to reference laboratories. The rapid-cycle real-time PCR assay described herein appears to be a useful test for confirming B. anthracis isolated by culture. The results of our study showed that the LightCycler Bacillus anthracis assay correctly identified all 31 B. anthracis strains tested. Twenty-eight of these strains carried both the pagA and capB genes and were confirmed as virulent B. anthracis strains. One strain was previously shown to carry both the pagA gene and the capA gene and therefore was classified as a virulent strain. Subsequent analysis of this strain in the present study demonstrated the absence of the capB gene. Further evaluation of this strain indicated a loss of all three encapsulation genes (capA, capB, and capC), suggesting that plasmid pX02 was no longer present. Three strains lacked either of these genes and were correctly identified as avirulent B. anthracis strains. The specificity of the assay was also demonstrated. None of the 31 Bacillus species other than B. anthracis strains and none of the other 26 organisms representing genera other than Bacillus had positive results for either pagA or capB.

Methods currently used for presumptive identification of B. anthracis and which can be performed in most clinical laboratories include cultivation on sheep blood agar, Gram stain and catalase, and motility testing. B. anthracis organisms are large spore-forming gram-positive bacilli that are catalase positive and amotile and do not produce hemolysis on blood agar. To confirm organisms with these characteristics as B. anthracis, it is recommended that they be tested for lysis by gamma phage and that direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing for capsule antigen and cell wall polysaccharide be performed. The reliability of gamma phage and DFA testing is unknown, and currently in the United States, these tests can only be performed at higher-level laboratories that are part of the Laboratory Response Network (17).

PCR-based nucleic acid amplification methods have been recognized as valuable diagnostic tools for some time. However, conventional PCR testing has not been widely implemented in clinical laboratories, in part due to its requirement for time-consuming and labor-intensive steps, which include specimen preparation, amplification, and product confirmation. Moreover, there have been concerns about amplification product (amplicon) carryover contamination. The latter three concerns are essentially eliminated by rapid, real-time PCR testing methods, in which the amplification reaction and confirmation of product occur rapidly and automatically in a closed reaction vessel. Specimen preparation has also been streamlined by automated extraction platforms, such as the MagNAPure instrument (Roche Applied Science), which was used to extract DNA from the majority of B. anthracis strains evaluated in the present study. Other potential advantages of real-time PCR testing based methods compared to culture-based methods include enhanced sensitivity and shortened analytical turnaround times for the direct detection of infectious agents from human specimens. Using real-time PCR and FRET technology, we have noted significantly greater sensitivities and reduced analytical times compared with culture for the direct detection of group A streptococci, Bordetella pertussis, herpes zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus from patient samples (5).

An analytical turnaround time of less than 1 h post-specimen processing is frequently possible with the LightCycler Bacillus anthracis assay. Extraction of DNA from B. anthracis isolates can be accomplished in approximately 1 h with the MagNAPure instrument and Mag NA Pure LC DNA isolation kit and in about 30 min with the High Pure PCR template preparation kit. Therefore, the total time for specimen processing and analysis is 1.5 to 2 h. Because the current application is described for identification of cultured isolates of B. anthracis, an additional 18 to 24 h may be required for bacterial growth before the LightCycler test can be performed. We are currently evaluating the utility of this assay for detection of B. anthracis directly from patient samples. Preliminary work performed in our laboratory indicates that one copy of target DNA (either capB or pagA) can be detected by this method in 1 μl of spiked human blood. This is in the same range as that observed in the analytical sensitivity studies conducted for the present evaluation. Clinical studies are required to assess whether this sensitivity will be validated for direct detection of B. anthracis in human specimens. These studies may be difficult in view of the very low incidence of human anthrax infections. Presuming that this assay can be applied directly to human specimens, the analytical turnaround time should be considerably less than that required for conventional culture-based tests, which minimally require 24 h to complete.

Even with more widespread utilization of this real-time PCR testing for B. anthracis, there will be a continued need for culture. For example, the standard genetic fingerprinting method for bacteria is pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and this method involves fragmentation of genomic DNA obtained from culture. Furthermore, antimicrobial susceptibility testing of B. anthracis requires that the organism be cultured.

The diagnostic potential of PCR for the direct detection of B. anthracis from human specimens has been confirmed in a report detailing the first 10 cases of inhalation anthrax associated with the recent deliberate release of anthrax in the United States (12). For 2 of the 10 patients reported in this study, all cultures of sterile fluids, including blood and pleural fluid, were negative for B. anthracis. Both of these patients received antimicrobial agents effective against B. anthracis early in their illness, which may have resulted in negative cultures. One of these patients had a positive PCR result for a blood sample; immunohistochemistry stains for B. anthracis cell wall and capsule antigen gave positive results for a pleural fluid sample. The second patient had a positive PCR result for B. anthracis for two pleural fluid samples; one of these pleural fluids was tested and was positive by immunohistochemical staining. For many patients in the study, it was noted that blood cultures rapidly became sterile after initiation of antibiotic therapy. All of these findings support the contention that laboratories that rely solely on conventional culture-based techniques may underdiagnose anthrax. A user-friendly real-time PCR assay like the LightCycler assay may provide a useful adjunct to culture for laboratories attempting to detect B. anthracis.

For PCR assays, we believe that gene targets on both virulence plasmids of B. anthracis (pX01 and pX02) should be amplified. This is because both of these plasmids must be present for an isolate to be virulent. Such PCR assays may therefore have the potential to differentiate virulent from avirulent (vaccine) strains. The targeting of chromosomal nucleic acid sequences for B. anthracis identification is discouraged due to the extensive chromosomal homology that exists among the organisms of the B. cereus genogroup. In fact B. anthracis, B. cereus, and B. thuringiensis may even belong to the same species (9).

Plasmids pX01 and pX02 may spread horizontally (9), and B. anthracis isolates may be “cured” of a plasmid in the laboratory (8). Indeed, Pasteur generated the first live, attenuated bacterial vaccine by growing B. anthracis at an elevated temperature. This experiment resulted in the loss of the plasmid pX02 and therefore the loss of the antiphagocytic capsule genes that are located on this plasmid (8). Naturally occurring isolates lacking plasmid pX02 have been identified (22), and vaccine isolates without either plasmid pX01 or pX02 have been produced. These nonvirulent isolates could be used as hoax agents, necessitating the targeting of genes in both plasmids for the molecular detection of B. anthracis. The LightCycler assay presented herein detects both pagA and capB genes and therefore may help to distinguish virulent from avirulent or vaccine strains. However, in the setting of clinical disease, identification of only one gene target (capB or pagA) may indicate spontaneous loss of the respective plasmid with passage by culture in vitro.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that the LightCycler Bacillus anthracis assay appears to be a suitable rapid method for identification of cultured isolates of B. anthracis. Further clinical studies are required to determine the utility of this test for the rapid identification of B. anthracis directly from human specimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ash, C., J. A. E. Farrow, M. Dorsch, E. Stackebrandt, and M. D. Collins. 1991. Comparative analysis of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and related species on the basis of reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:343-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyer, W., P. Glockner, J. Otto, and R. Bohm. 1995. A nested PCR method for the detection of Bacillus anthracis in environmental samples collected from former tannery sites. Microbiol. Res. 150:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyer, W., S. Pocivalsek, and R. Bohm. 1999. Polymerase chain reaction-ELISA to detect Bacillus anthracis from soil samples—limitations of present published primers. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brightwell, G., M. Pearce, and D. Leslie. 1998. Development of internal controls for PCR detection of Bacillus anthracis. Mol. Cell. Probes 12:367-377. (Erratum, 13:167, 1999.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cockerill, F. R., and J. R. Uhl. 2001. Applications and challenges of real-time PCR for the clinical microbiology laboratory, p. 31-41. In U. Reischl, C. Wittwer, and F. R. Cockerill (ed.), Rapid cycle real-time PCR, methods and applications, microbiology and food analysis. Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 6.Dixon, T. C., M. Meselson, J. Guillemin, and P. C. Hanna. 1999. Anthrax. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:815-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franz, D. R., P. B. Jahrling, A. M. Friedlander, et. al. 1997. Clinical recognition and management of anthrax—an update. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:399-411. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna, P. 1998. Anthrax pathogenesis and host response. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 225:13-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helgason, E., O. A. Økstad, D. A. Caugant, H. A. Johansen, A. Fouet, M. Mock, I. Hegna, and A. B. Kolstø. 2000. Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis—one species on the basis of genetic evidence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2627-2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins, J. A., M. S. Ibrahim, F. K. Knauert, G. V. Ludwig, T. M. Kijek, J. W. Ezzell, B. C. Courtney, and E. A. Henchal. 1999. Sensitive and rapid identification of biological threat agents. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 894:130-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inglesby, T. V., D. A. Henderson, J. G. Bartlett, M. S. Ascher, E. Eitzen, A. M. Friedlander, J. Hauer, J. McDade, M. T. Osterholm, T. O'Toole, G. Parker, T. M. Perl, P. Russell, and K. Toanat. 1999. Anthrax as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. JAMA 281:1735-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jernigan, J. A., D. S. Stephens, D. A. Ashford, C. Omenaca, M. S. Topiel, M. Galbraith, M. Tapper, T. L. Fisk, S. Zaki, T. Popovic, R. F. Meyer, C. P. Quinn, S. A. Harper, S. K. Fridkin, J. J. Sejvar, C. W. Shepard, M. McConnell, J. Guarner, W.-J. Shieh, J. M. Malecki, J. L. Gerberding, J. M. Hughes, and B. A. Perkins. 2001. Bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax: the first 10 cases reported in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:933-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klietmann, W. F., and K. L. Ruoff. 2001. Bioterrorism: implications for the clinical microbiologist. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:364-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, M. A., G. Brightwell, D. Leslie, H. Bird, and A. Hamilton. 1999. Fluorescent detection techniques for real-time multiplex strand specific detection of Bacillus anthracis using rapid PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:218-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makino, S.-I., H. I. Cheun, M. Wataral, I. Uchida, and K. Takeshi. 2001. Detection of anthrax spores from the air by real-time PCR. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 33:237-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makino, S.-I., Y. Iinuma-Okada, T. Maruyama, T. Ezaki, C. Sasakawa, and M. Yoshikawa. 1993. Direct detection of Bacillus anthracis DNA in animals by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:547-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, J. M. 2001. Agents of bioterrorism. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 15:1127-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramisse, V., G. Patra, H. Garrigue, J. L. Guesdon, and M. Mock. 1996. Identification and characterization of Bacillus anthracis by multiplex PCR analysis of sequences on plasmids pXO1 and pXO2 and chromosomal DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 145:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reif, T. C., M. Johns, S. D. Pillai, and M. Carl. 1994. Identification of capsule-forming Bacillus anthracis spores with the PCR and a novel dual-probe hybridization format. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1622-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shafazand, S., R. Doyle, S. Ruoss, A. Weinacker, and T. A. Raffin. 1999. Inhalation anthrax: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Chest 116:1369-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swartz, M. N. 2001. Recognition and management of anthrax—an update. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1621-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turnbull, P. C. 1999. Definitive identification of Bacillus anthracis—review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:237-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]