Abstract

Background

Bladder cancer (BC), characterized by epithelial heterogeneity, remains a challenging malignancy with limited tissue biomarkers for anticipating neoadjuvant chemotherapy efficacy. Tumor progression, orchestrated by cancer cells, intricately involves the modulation of apoptosis-related pathways. Given their pivotal role in this cascade, apoptosis-related genes emerge as potential determinants of tumor development. Concurrently, the formidable challenge of drug resistance significantly impedes the success of cancer treatments, where a patient's susceptibility to chemotherapy profoundly influences therapeutic outcomes. Consequently, our objective is to develop a prognostic risk model rooted in apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene. This comprehensive approach aims to enhance our ability to predict the prognosis of BC patients and optimize treatment strategies.

Methods

We extracted 412 BC patients and 19 healthy humans RNA-seq samples from the TCGA database and loaded 1416 apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes from the GeneCards website. Subsequently, we established four risk score models for apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes through single-factor, multi-factor, and LASSO regression analysis. Additionally, we conducted analyses on the risk model using methods such as Kaplan–Meier log-rank test, principal component analysis, time-dependent ROC curve analysis, uni-variate analysis, and multivariate Cox regression analysis. We discussed the relationship of this model with the immune status and its predictive capability for drug sensitivity. Finally, we validated the correlation of these four genes with BC drug resistance by establishing drug-resistant cell lines and conducting in vitro drug resistance-related experiments.

Results

This study’s findings demonstrate that apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes can impact the progression of BC. We obtained a prognostic risk model composed of four apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes (FASN, GLI2, VHL, and PDGFRA). Among them, FASN, GLI2, and PDGFRA were identified as risk factors, with high expression in the high-risk group, while VHL exhibited high expression in the low-risk group. A nomogram was constructed based on these features to assess patient survival and prognosis. In addition, in vitro drug resistance experiments showed that FASN was associated with BC resistance.

Conclusion

These four apoptosis-related genes may serve as valuable factors for predicting the prognosis of BC, providing insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of apoptosis-related genes in BC. It provides a new research path to overcome drug resistance in BC. They offer more precise references and guidance for the treatment of high-risk BC patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-02581-5.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Chemotherapy, Prognosis, Bladder cancer, Bioinformatics

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) ranks among the most prevalent malignancies within the urinary system, accounting for approximately 900,000 newly diagnosed cases and 250,000 annual fatalities [1]. The disease exhibits a high degree of heterogeneity, resulting in variations in histological attributes, molecular profiles, and subtypes across individuals [2]. Presently, treatment modalities for BC are primarily confined to radical cystectomy and Cisplatin-based chemotherapy [3]. Nevertheless, both approaches are encumbered by limitations stemming from tumor recurrence rates and drug resistance.

In recent years, tumor immunology has emerged as a pivotal domain within cancer research [4]. Noteworthy progress has been documented in immunotherapeutic strategies for a spectrum of malignancies, encompassing hepatocellular carcinoma [5]. Currently, the foremost challenges in clinical research pertaining to BC persist in the form of elevated recurrence rates and drug resistance. Consequently, the identification of pertinent biomarkers capable of prognosticating disease progression, delineating prognosis, and guiding tailored precision interventions is imperative.

Cell apoptosis, the programmed death of cells, involves a cascade of gene activations and regulations, playing a pivotal role in various normal physiological processes [6]. Dysregulation of gene expression associated with apoptosis has been demonstrated as a critical factor influencing the development and progression of numerous cancers [7]. In addition, apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes are also associated with tumor resistance to targeted therapies. Firstly, apoptosis genes can induce tumor resistance through mutations in target molecules. Secondly, they can disrupt the upstream or downstream signal proteins in the therapeutic targets, leading to tumor resistance. Furthermore, apoptosis genes can confer resistance to tumors by activating alternative biological pathways [8]. However, there is currently no research that has explored the prognostic significance of apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene characteristics in BC, as well as the mechanisms associated with resistance to targeted therapies in BC.

In the present study, we utilized RNA sequencing data and clinical information from BC patients in TCGA to identify four apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. Subsequently, we established a risk prediction model to accurately predict overall survival and prognosis in patients. Our research results validate the reliability of the prediction model composed of these four apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes, suggesting that these four genes may be potential therapeutic targets in BC. Furthermore, we conducted in vitro experiments related to drug resistance, and the findings demonstrated a notable association between FASN and resistance to targeted therapies in BC among the four genes related to apoptosis and chemotherapy.

Method

Patients dataset

The RNA sequences and clinical information of 412 BC patients and 19 healthy humans were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/). Samples with a survival time of fewer than 30 days were excluded from the analysis. We obtained information on 1416 genes related to apoptosis and chemotherapy from GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org).

Identification of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes

Data normalization, processing, and analysis were conducted using R software version 4.3.1. Under the cutoff values of false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and |log2 fold change (FC)|≥ 1, we identified differentially expressed apoptosis and chemotherapy-related genes between normal bladder and BC samples. A co-expression analysis of these genes allowed for the identification of potential candidates associated with apoptosis and chemotherapy. The R software was employed to randomly allocate all samples into training and testing sets at a 1:1 ratio. Subsequently, univariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was utilized to ascertain apoptosis and chemotherapy-related genes significantly linked to overall survival (OS) in the training cohort, with a defined significance threshold of p < 0.05. Furthermore, the most pertinent apoptosis and chemotherapy-related genes in relation to OS were validated through the application of the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression method using the 'glmnet' package in R.

Construction of an apoptosis and chemotherapy related risk prediction system

We conducted multivariate Cox regression analysis to identify crucial genes for constructing prognostic signatures. Following this, we calculated individualized risk scores for each patient based on the expression levels of apoptosis and chemotherapy-related genes. This was achieved using the following formula [9]: Riskscore = exp1β1 + exp2β2… + expi*βi. Here, expi represents the expression value of each apoptosis and chemotherapy-related gene, while βi signifies the multivariate Cox analysis regression coefficient for the respective apoptosis and chemotherapy-related gene. Subsequently, BC patients were categorized into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score within the training set.

Application verification of risk scoring system

To assess the model's predictive capability, we performed various statistical analyses, including the Kaplan–Meier log-rank test, time-dependent ROC curve analysis, univariate analysis, and multivariate Cox regression analysis. These analyses utilized the R packages 'survival' and 'survival ROC'. Survival rates between the high-risk and low-risk groups were compared across the training, testing, and overall datasets. Additionally, we examined the correlations between the expression levels of the four apoptosis and chemotherapy-related genes and clinical-pathological characteristics.

GSEA analysis

We performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) version 4.0.3 [10] (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea). The BC samples from the TCGA dataset were divided into two groups based on their risk scores. Subsequently, GSEA was independently conducted for each group using both KEGG and GO gene sets. Pathways within KEGG/GO showing a False Discovery Rate (FDR) value of < 0.25 and a p-value of < 0.05, after 1000 permutations, were considered significantly enriched in the high/low apoptosis gene groups.

Cell lines

The human normal urothelial cell line human BC cell lines (T24 and UMUC3) cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and were maintained in DMED and RPMI 1640 medium containing 10 fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), respectively. All cell lines were cultured at the appropriate medium at 37 °C and supplied with 5% CO2. In order to generate BC cell lines resistant to Gemcitabine (T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem) and Cisplatin (T24-CDPP and UMUC3-CDPP), T24 and UMUC3 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of gemcitabine. The resulting T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem were maintained in the presence of 10 μM gemcitabine, while T24-CDPP and UMUC3-CDPP were maintained in the presence of 20 μM. Gemcitabine (GEM) (Cat. No. T0251, TOPSCIENCE, Shanghai, China) and Cisplatin (Cat. No. T1564, TOPSCIENCE, Shanghai, China) powders were dissolved in DMSO at appropriate concentration and used in the following experiments. The DMSO concentration in the medium did not exceed 0.1% (volume per volume).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

The assessment of cell viability was conducted through the CCK-8 assay. Approximately 5 × 103 cells were seeded in triplicate in 96-well plates. Following drug treatment or transfection, 10 μl of CCK-8 solution (Servicebio) was introduced to each well. After a 2-h incubation period, the optical density (OD) values at 450 nm were measured using a spectrometer (Molecular Devices, USA).

Transfection of small interfering RNA

Three small interfering RNAs against FASN (siFASN) and GLI2 (siGLI2), along with a scrambled negative control siRNA (si-NC), were designed and synthesized by Ribobio (Guangzhou, China). The transfection of siRNAs into cells was facilitated using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis

Protein lysates were treated with RIPA buffer (Invitrogen) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). The protein sample concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, the protein samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After a 1-h blocking step at room temperature, primary antibodies targeting human FASN, GLI2, PDGFRA, VHL or β-Actin from Proteintech Group, Wuhan, China, were incubated at 4 °C for 12 h. FASN (Cat. No. 10624-2-AP), GLI2 (Cat. No. 18989-1-AP) and β-Actin (Cat. No. 81115-1-RR) were purchased from Proteintech Group (Wuhan, China). PDGFRA (Cat. No. ab203491) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). VHL (Cat. No. 68547)were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with specific HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Proteintech Group, Wuhan, China) for 2 h before development with the ECL kit (Beyotime). All images were captured using Tanon 5200 (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

Statistical analysis

We assessed differences in patients' overall survival using the Kaplan–Meier log-rank test. Both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted to determine whether the predictive model remained independent of clinical characteristics. Furthermore, we employed time-dependent ROC curve analysis to assess the accuracy of the signature. These analyses were implemented using the R packages 'survival' and 'survival ROC'. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.1, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05. In vitro experimental data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (La Jolla, USA) and reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). T-tests were used for comparisons between groups, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene enrichment analysis

We obtained 466 differentially expressed apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes, 249 genes were found to be up-regulated, while 217 genes were down-regulated in BC tissues (Fig. 1A). We conducted KEGG and GO analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. KEGG pathway analysis revealed that apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes were predominantly enriched in pathways such as MicroRNAs in cancer, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, Calcium signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, Proteoglycans in cancer, and Cell cycle (Fig. 1B, C). In the biological process category, GO pathway analysis showed that apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes were mainly enriched in processes such as urogenital system development, response to decreased oxygen levels, muscle cell proliferation, aging, renal system development, kidney development, and regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation (Fig. 1D, E).

Fig. 1.

KEGG and KO analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes in BC. A There are 466 apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes in BC. Orange dots represent up-regulated genes, and blue represents down-regulated genes. B Bubble chart of KEGG analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. C Circle chart of KEGG analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. D Bubble chart of GO analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. E Circle chart of GO analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. GO: Gene Ontology; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Identification of genes associated with apoptosis and chemotherapy and development of a prognostic model

To narrow down apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes for prognostic purposes, uni-variate Cox regression analysis was conducted, revealing 33 apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes significantly associated with overall survival (OS) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2A).To avoid over-fitting, we utilized the LASSO regression method for variable selection and addressing multicollinearity. Seventeen apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes were selected by LASSO, and an optimized prognostic feature was constructed by adjusting λ using the glmnet package in R software (Fig. 2B, C). Subsequently, a multivariate Cox analysis further narrowed down the 17 apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes to four key genes associated with OS: FASN (HR = 1.7601387, p = 0.0000524), GLI2 (HR = 1.7192552, p = 0.0075466), VHL (HR = 0.5294918, p = 0.0013854), and PDGFRA (HR = 1.3783587, p = 0.0194117) (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Identification and construction of an apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene prognostic model through uni-variate Cox regression and Lasso regression analysis. A Forest plot of 33 candidate apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes selected through uni-variate Cox regression analysis, which are associated with BC survival rates in the training set. B LASSO coefficient profiles of the 17 candidate points in the training set. C Coefficient profile plot generated based on the log(λ) sequence. Selection of the optimal parameter (λ) in the LASSO model." D Multi-factor Cox regression analysis shows that genes are independent prognostic factors

Bladder cancer patient predictive features and their correlation with prognosis

To further evaluate the performance of the gene model across various clinical and pathological sub-types, we grouped patients according to various clinical features, such as N stage (N0-3), T stage (T0-3), Stage (1–4), gender (male and female), age (≤ 65 and > 65), and Fustat (alive and dead). A heat-map, combining clinical information and the expression levels of the four genes related to apoptosis and chemotherapy, was used to rank patients based on risk scores. Low gene expression was represented in green, while high gene expression was depicted in red. The results showed that VHL was up-regulated in the low-risk group, while FASN, GLI2, and PDGFRA were up-regulated in the high-risk group (Fig. 3A).To further assess the value of this model, we conducted Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis for the four apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. The analysis indicated that patients with elevated expression levels of FASN, GLI2, and PDGFRA exhibited significantly shorter overall survival (OS) compared to those with lower expression levels. Conversely, patients with increased expression of VHL demonstrated significantly longer OS compared to the low-expression group (Fig. 3B–E).

Fig. 3.

The prognostic value of a risk model for 4 apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. A Heatmap combining clinical information and the expression of 4 genes, with green indicating low gene expression and red indicating high gene expression. B Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis showing the survival difference between high and low-risk BC patients, according to FANS gene (B), GLI2 gene (C), VHL gene (D), and FDGFRA gene (E)

To ascertain the independence of the predictive features as prognostic factors for BC patients, Cox regression analysis was conducted, aiming for a more substantial reduction in complexity. Uni-variate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that age, Stage, T stage, N stage, and risk score were significantly associated with the overall survival (OS) of BC patients (Fig. 4A). Multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that age and risk score independently predicted overall survival in BC patients (Fig. 4B). The AUC of the risk score reached 0.757, indicating that it outperformed clinical and pathological variables in predicting the prognosis of BC patients (Fig. 4C). To further prognosticate the outcomes of BC patients, a nomogram was constructed, incorporating clinical and pathological variables along with the risk score. This nomogram could predict the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year prognosis of BC patients (Fig. 4D). Calibration curves exhibited favorable consistency between observed overall survival rates and predicted survival rates at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years (Fig. 4E–G). These results suggest that the predictive features have the capability to forecast the prognosis of BC patients.

Fig. 4.

Development of a personalized prediction model for overall survival (OS) in BC patients. A, B Uni-variate (A) and Multi-variate (B) Cox regression analyses showing the impact of clinical factors and risk scores on overall survival for all samples. C ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) analysis of risk score, age, gender, stage, T, N, and OS in the BC cohort. D Construction of a Nomogram for predicting 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year OS in BC patients. E–G Calibration curve analysis

The predictive ability of apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene prognostic features

Based on the median risk score in the training set, BC patients were stratified into low-risk and high-risk groups. The Kaplan–Meier analysis illustrated that the median overall survival (OS) in the low-risk group exceeded that in the high-risk group (p = 2.07837835145552e−05) (Fig. 5A). To enhance the prognostic model's accuracy, we applied the same algorithm for further evaluation on both the training and testing sets. The results remained consistent with the training set, demonstrating significantly higher OS in the low-risk group compared to the high-risk group (p = 2.54994486920124e−05 in the testing set, and p < 0.001 in the total set) (Fig. 5B, C).

Fig. 5.

Validation of the prognostic feature prediction ability of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes. A–C Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for BC overall survival curves in the training set (A), testing set (B), and the total set (C), with a low or high risk of death based on the model-based classifier risk score level. D–F Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene risk scores in the training set (D), testing set (E), and the total set (F) to assess sensitivity and specificity

In the ROC curve analysis within the training set, the model demonstrated good predictive value for BC survival (1-year AUC = 0.734, 3-year AUC = 0.713, 5-year AUC = 0.796) (Fig. 5D). Subsequently, we validated the model in the testing set, resulting in a 1-year AUC of 0.662, a 3-year AUC of 0.706, and a 5-year AUC of 0.732 (Fig. 5E). For the total set, the AUC values were 0.696 for 1 year, 0.711 for 3 years, and 0.755 for 5 years (Fig. 5F).

Analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene feature risk score

We utilized scatter plots and risk curves to analyze the risk scores and survival status of each BC patient. In the training set, testing set, and total set, the high-risk group exhibited significantly higher hazard ratios and mortality rates compared to the low-risk group (Fig. 6A–F). Heatmaps revealed that in the training set, GLI2, PDGFRA, and FASN were up-regulated in the high-risk group, whereas VHL was up-regulated in the low-risk group. Similar patterns were observed in both the testing set and the total set (Fig. 6G–I).

Fig. 6.

Analysis of apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene feature risk scores. A–C Scatter-plots of survival outcomes for training (A), testing (B), and total (C) samples, where blue and orange dots represent survival and death, respectively. D–F Feature risk score distributions in training (D), testing (E), and total (F) set. G–I Heat-maps display the expression profile distribution of this signature in low-risk and high-risk groups in training (G), testing (H), and total (I) datasets, with pink bars representing the low-risk group and blue bars representing the high-risk group

Principal component analysis was utilized to further validate the grouping capability of the apoptosis and chemotherapy-related gene model

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed based on the total genes (Fig. 7A), apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes (Fig. 7B), and the risk model (Fig. 7C) to detect differences between the low-risk and high-risk groups. Our results demonstrate that the low-risk and high-risk groups, as shown in Fig. 7A and 7B, are relatively dispersed, while our risk model effectively distinguishes between the low and high-risk groups, further corroborating the accuracy of our risk model.

Fig. 7.

The apoptosis status differs between low-risk and high-risk groups. A–C Principal component analysis (PCA) of low-risk and high-risk groups based on the whole genome (A), the genome of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes in BC (B), and four apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene prediction models (C)

Analysis of immune cell infiltration and immune-related functional scoring

To delve deeper into the correlation between risk scores and immune cells and functions, we quantified single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) enrichment scores for various immune cell subtypes and associated functions. The results of immune cell infiltration showed that activated dendritic cells (aDCs), CD8+ T cells, Macrophages, T helper cells, T follicular helper (Tfh), T helper type 1 (Th1) cells, T helper type 2(Th2 cells), and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) had higher scores in the high-risk group (Fig. 8A). Immune-related functional results revealed that antigen-presenting cell (APC) coinhibition, APC costimulation, chemokine receptor (CCR), Checkpoint, Cytolytic activity, Inflammation promoting, Parainflammation, T cell coinhibition, T cell costimulation, and Type I IFN Response had a higher proportion in the high-risk group (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Immune cell infiltration and immune-related functional scoring in high-risk and low-risk groups. A Violin plot showing immune infiltration of lymphocytes between the low-risk (green) and high-risk (red) groups. B Infiltration levels of 16 immune cells in high-risk and low-risk groups calculated using the ssGSEA algorithm. C Correlation of predictive features with 13 immune-related functions. D Differences in the expression of common immune checkpoint markers in the high-risk population

Additionally, we further employed the CIBERSORT algorithm to compare the proportions of 22 immune cell types between the high-risk and low-risk groups. The results indicated that in the low-risk group, the proportions of naive B cells (p < 0.001), CD8+ T cells (p < 0.001), resting memory CD4+ T cells (p < 0.001), and activated memory CD4+ T cells (p < 0.001) were higher, while M0 Macrophages (p < 0.001) and M2 Macrophages (p < 0.001) were more abundant in the high-risk group (Fig. 8C). In addition, we conducted a comparative analysis of common immune checkpoint expression in the high-risk population, showing that nearly every immune checkpoint was more active in the high-risk BC group (Fig. 8D). These findings suggest that immune functions are more active in the high-risk population.

Tumor micro environment analysis

We used the ESTIMATE algorithm to calculate immune scores and stromal scores for the low-risk and high-risk groups, allowing us to quantitatively compare the immune and stromal components in the two tumor groups. In the results, red represents the high-risk group, and blue represents the low-risk group. The scores for stromal score, immune score, and ESTIMATE score were all higher in the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group (Fig. 9A–C). These results further validate that our risk model is a method that can correctly predict the effectiveness of immunotherapy and prognosis for BC patients.

Fig. 9.

Tumor micro-environment analysis in high and low-risk groups. A Stromal score. B Immune score. C Estimate score

Drug sensitivity analysis

We compared the drug sensitivity between the low-risk group and the high-risk group, revealing that BC patients in the high-risk group exhibited resistance to 13 chemotherapy drugs, including Cisplatin and Gemcitabine, the basic chemotherapeutic drugs for BC, and showed strong sensitivity to 24 chemotherapy drugs (Fig. 10A, B, S1A-K and S2A-X). These findings suggest that the model has the potential to serve as a predictive factor for chemotherapy sensitivity. Researching specialized treatment regimens tailored to BC risk groups is beneficial and can provide advantages in the treatment and prognosis of BC patients in the high-risk group, thus further extending the survival period of BC patients.

Fig. 10.

Drug sensitivity analysis. A IC50 of Gemcitabine in high and low-risk groups. B IC50 of Cisplatin in high and low-risk groups

Functional analysis

In our analysis, we conducted KEGG and GO functional enrichment analyses. In the KEGG analysis, apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes were primarily enriched in Ecm receptor interaction, Dilated cardiomyopathy, Hyper-trophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), and Focal adhesion (Fig. 11A). In the GO analysis, apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes were mainly enriched in the following terms: Negative regulation of interleukin 10 production, Endonuclease activity active with either ribonucleic or deoxyribonucleic acids, Positive regulation of interleukin 4 production, Interleukin 4 production, and Cytokine activity (Fig. 11B).

Fig. 11.

KEGG and GO Enrichment analysis. A KEGG Enrichment analysis. B GO Enrichment analysis

Analysis of the correlation between predictive models and clinical variables

We used TCGA gene expression and clinical variables data to explore the correlation between the model genes and clinical variables. The results indicated that GLI2 was associated with fustat, gender, grade, stage, and T-stage (Fig. S3A–E). PDGFRA exhibited associations with fustat, gender, grade, stage, and T-stage (Fig. S3F–J). VHL, on the other hand, showed an association only with gender (Fig. S3K). The Riskscore demonstrated associations with fustat, gender, grade, stage, and T-stage (Fig. S3L-P).

Drug resistance verification

For further investigation into the role of genes in the BC drug resistance risk model, we initially screened and established gemcitabine-resistant BC cell lines, designated as T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem. The IC50 for gemcitabine in T24-Gem cells is 40.51 μM, significantly higher than the parental cells with an IC50 of 1.042 μM. The calculated resistant index (RI) is approximately 38.88 (RI = 40.51/1.042), indicating substantial gemcitabine resistance in T24-Gem. Similarly, the IC50 for UMUC3-Gem is 38.76 μM, compared to the parental cells with an IC50 of 0.9974 μM (Fig. 12A). The RI for UMUC3-Gem is also notably high (RI = 38.86 = 38.76/0.9974) (Fig. 12A). In T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem, the expression level of the FASN protein significantly increased, while GLI2, PDGFRA, and VHL did not show significant alterations (Fig. 12B). Furthermore, we designed siRNAs targeting FASN (siFASN) and verified that siFASN-1 and siFASN-1 were effectively silenced in T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem (Fig. 12C, D). Downregulating the expression of FASN resulted in a notable decrease in gemcitabine resistance in T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cell lines (Fig. 12E).

Fig. 12.

Validation of Gemcitabine resistance in BC cell lines. A CCK-8 assay was performed to detect cell viability treated with different concentrations of gemcitabine in T24, UMUC3, T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cells. B The protein levels of FASN, GLI2, PDGFRA and VHL in T24, T24-Gem, UMUC3, and UMUC3-Gem cells were validated by western blotting. C, D The efficiency of FASN silencing in T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cells was detected by qRT-PCR and western blotting. E Cell viability abilities of T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cells treated with different concentrations of Gemcitabine at 72 h after transfection were evaluated by CCK-8 assays. Data are presented as mean ± Standard Error of Mean (SEM) from three independent replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test)

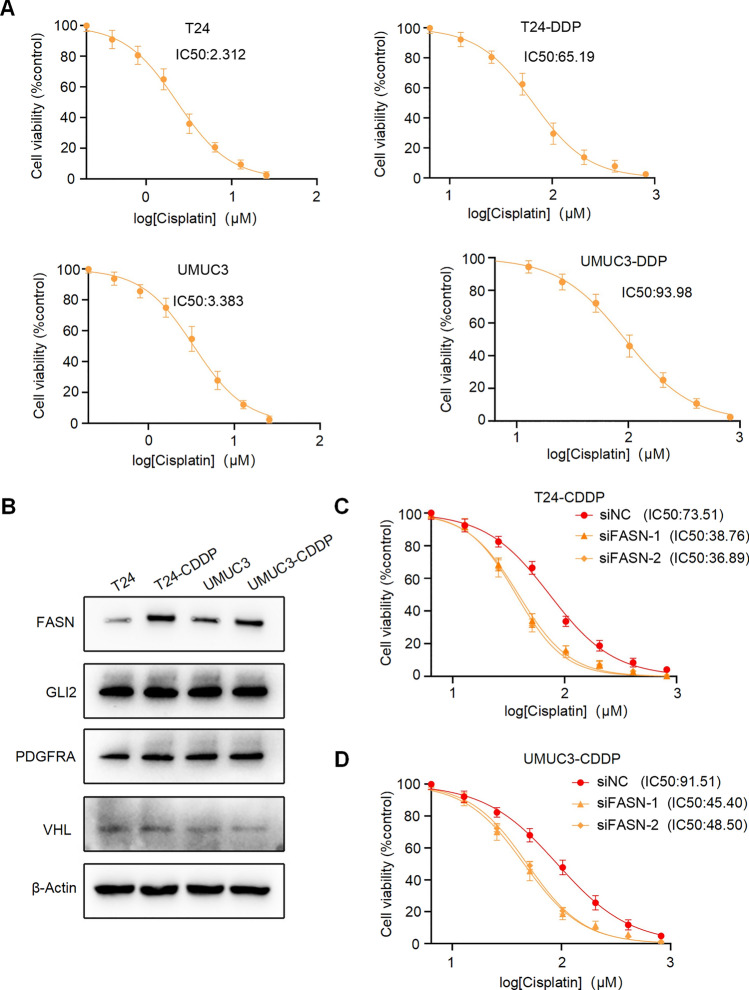

Next, we screened and established Cisplatin-resistant BC cell lines, named T24-CDPP and UMUC3-CDPP (Fig. 13A). Similarly, in T24-CDPP and UMUC3-CDPP, the expression level of the FASN protein was significantly increased (Fig. 13B). Moreover, silencing FASN significantly enhanced the drug sensitivity of T24-CDPP and UMUC3-CDPP lines to Cisplatin (Fig. 13C). These results demonstrate that FASN promotes drug resistance in BC within the risk model.

Fig. 13.

Validation of Cisplatin resistance in BC cell lines. A CCK-8 assay was performed to detect cell viability treated with different concentrations of Cisplatin in T24, UMUC3, T24-CDDP and UMUC3-CDDP cells. B The protein levels of FASN, GLI2, PDGFRA and VHL in T24, T24-CDDP, UMUC3, and UMUC3-CDDP cells were validated by western blotting. C, D Cell viability abilities of T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cells treated with different concentrations of Cisplatin at 72 h after transfection were evaluated by CCK-8 assays. Data are presented as mean ± Standard Error of Mean (SEM) from three independent replicates

We also designed siRNAs targeting GLI2 (siGLI2) and verified the effective silencing of GLI2 in T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cells (Fig. S4A, B). However, the downregulation of GLI2 expression did not lead to a reduction in Gemcitabine resistance in the T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cell lines (Fig. S4C, D). Similarly, downregulation of GLI2 expression did not result in reduced Cisplatin resistance in the T24-CDDP and UMUC3-CDDP cell lines (Fig. S4C, D).

Discussion

Through in-depth research into apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes [11] and the immune system [12], researchers have uncovered the potential of apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes not only as prognostic biomarkers for cancer but also as avenues for exploring novel treatment approaches. Nevertheless, there is currently insufficient research validating the accuracy of apoptosis genes in evaluating prognosis.

Using single-factor COX regression analysis, this study identified 33 apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes associated with the prognosis of BC patients. Through LASSO and multi-factor regression analysis, we confirmed four apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes (GLI2, PDGFRA, VHL, and FASN). Our four candidate genes have been documented to exert a significant influence by modulating apoptosis in tumor cells. One study found that the Hh signaling pathway can induce GLI2 to bind to the promoter of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 6 (CDK6), thus activating CDK6 expression, ultimately promoting the proliferation of medulloblastoma cells and facilitating the progression of medulloblastoma [13]. Mutations or amplifications of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor Alpha (PDGFRA) and Neurotrophic Tyrosine Kinase Receptor (NTRK) fusion genes are commonly found in advanced neuroglial tumors in both children and adults [14]. According to research findings [15], Fatty Acid Synthase (FASN) is involved in the progression of lung cancer. VHL has been reported to be frequently deleted in clear cell renal cell carcinoma tissues [16], the deletion of VHL leads to the stabilization of HIF2A, which in turn inhibits the enhancer of the pro-tumor gene CCND1. Collectively, these studies support the role of our four candidate genes in promoting tumor initiation and progression by influencing apoptosis in tumor cells. Subsequently, we computed risk scores for each patient using a risk formula, subsequently categorizing patients into low and high-risk groups based on the median score. The overall survival (OS) of the high-risk group was notably shorter than that of the low-risk group. The ROC curve indicates that our risk prediction model exhibits good predictive capability. Compared to clinical pathological variables, the prediction model provides a more reliable prognosis for BC patients.

GSEA uncovered that gene sets associated with ECM receptor interaction, Dilated cardiomyopathy, Hyper-trophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), and Focal adhesion were predominantly enriched in the high-risk group. Subsequent ssGSEA results showed higher levels of activated dendritic cells (aDCs), CD8+ T cells, T helper cells, T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, T helper type 1 (Th1) cells, Th2 cells, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in the high-risk group. Increased CD8+ T cell infiltration is associated with poor prognosis in BC [17]. Elevated levels of activated dendritic cells (aDCs) in the tumor micro-environment have been linked to worse outcomes in colon cancer patients [18]. Higher levels of T helper cells are indicative of poorer overall survival in T-cell lymphoma [19]. Increased T follicular helper (Tfh) cell infiltration is associated with worse outcomes in muscle-invasive BC [20]. Both Th1 and Th2 cell infiltration are associated with a poor prognosis in high-risk melanoma [21]. High tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte levels are correlated with a poorer prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer [22]. Furthermore, high-risk patients also demonstrate elevated levels of immune and stromal components in the tumor micro-environment compared to the low-risk group. This suggests that the changes in the tumor micro-environment are more pronounced in the high-risk population. Therefore, we hypothesize that the progression of the tumor micro-environment are factors contributing to the poor prognosis in the high-risk population.

The latest international BC treatment guidelines propose that for patients with advanced metastatic BC, the first-line treatment regimen involves Cisplatin combined with chemotherapy. For patients intolerant to Cisplatin, a dual therapy comprising carboplatin and gemcitabine is often considered a preferable and more tolerable treatment option [23]. Our study suggests that high-risk patients are responsive to gemcitabine but display resistance to both Cisplatin and Gemcitabine. To validate the association between four apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes and BC resistance, we conducted in vitro experiments. Initially, drug-resistant cell lines were established for Cisplatin and Gemcitabine in T24 and UMUC3 BC cell lines, respectively. We conducted an analysis of the protein expression of the four genes in these cell lines, revealing differential expression solely in the FASN gene. Further investigation involved silencing the FASN gene in tumor cells, followed by Western blotting and Northern blotting. Results demonstrated that upon FASN gene silencing, T24 and UMUC3 cells regained resistance to Cisplatin and Gemcitabine. Previous studies have shown that up-regulation of FASN increases pancreatic cancers cell resistance to gemcitabine [24]. Moreover, FASN overexpression in breast cancer sactivates the fatty acid synthesis pathway, leading to lapatinib resistance and promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition and neovascularization, thereby advancing BC progression and drug resistance. FASN gene overexpression triggers abnormal activation of the fatty acid synthesis pathway [25]. This leads to hydrolysis of intracellular fatty acids into free fatty acids, which are absorbed by downstream CD36, activating the CD36 signaling pathway and ultimately causing lapatinib resistance. Recent research indicates that the FASN gene modulates the DNA damage process, inducing resistance formation [26]. The up-regulation of PARP-1 by FASN can influence drug-induced DNA damage repair resistance. Moreover, silencing the FASN gene elevates ceramide and TNF-α production in breast cancer cells by up-regulating caspase-8, thereby increasing apoptosis protease-activating factor expression [27]. In conclusion, our future experiments aim to validate the functional correlation between the FASN gene and drug resistance in BC, offering potential for more effective therapeutic strategies. We have also discovered that combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy benefits high-risk individuals, enhancing their overall quality of life and providing a scientific foundation for precise personalized treatment of BC patients.

However, our study does have certain limitations. Firstly, our research data was exclusively derived from the TCGA database, and we did not conduct comprehensive analyses by integrating data from other databases for a more comprehensive investigation. Secondly, although we conducted in vitro experiments to confirm the involvement of apoptosis genes in tumor drug resistance, we did not delve deeply into the specific mechanisms relating to apoptosis genes and tumor resistance. Hence, further functional studies are necessary to validate the accuracy of our predictive model and to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying the association between apoptosis genes and tumor drug resistance.

Conclusion

In summary, we have identified a set of four genes (GLI2, PDGFRA, VHL, and FASN) that constitute an apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene signature, which may serve as a novel independent prognostic factor for BC. Furthermore, we conducted in vitro experiments related to drug resistance, and the results unveiled a notable correlation between FASN and resistance to targeted therapies in BC among the four apoptosis and chemotherapy-related genes. In the future, through further functional tests, these four apoptosis and chemotherapy related gene features can be utilized to enhance the predictive accuracy for BC patients, overcome drug resistance, and guide precise individualized treatments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (PNG 884 KB) Fig.S1 Drug Sensitivity Analysis. (A–K) IC50 of Tipifarnib (A), SB590885 (B),QS11 (C), Pyrimethamine (D), PAC.1 (E), Methotrexate (F), GW.441756 (G), Etoposide (H), BIRB.0769 (I), Eriotinib (J), ATRA (K) in high and low-risk groups.

Supplementary file2 (TIF 1786 KB) Fig.S2 Drug Sensitivity Analysis. (A–X) IC50 of AZD.0530 (A), Bexarotene(B), Bicalutamide (C), AZD6482 (D), BMS.509744 (E), BMS.536924(F), BX.795 (G), CGP.082996 (H), CHIR.99021 (I), CMK (J), GDC0941 (K), Cyclopamine (L), Dasatinib (M), DMOG (N), Embelin (O), GNF.2 (P), GSK269962A (Q), Lmatinib (R), JNJ.26854165 (S), KIN001.135 (T), NU.7441 (U), Midostaurin (V), MG.132 (Y), KU.55933 (X) in high and low-risk groups.

Supplementary file3 (PNG 457 KB) Fig.S3 The relationship between each of the four apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes and clinical features. (A-E) The relationship between GLI2 expression and Survival Status, Grade, Gender, and T Stage. (F–J) The relationship between PDGFRA expression and Survival Status, Gender, Grade, Stage, and T Stage. (K) The relationship between VHL and Gender. (L–P) The relationship between the risk score and Survival Status, Gender, Grade, Stage, and T Stage.

Supplementary file4 (TIF 387 KB)Fig.S4 Validation of Gemcitabine resistance in BC cell lines. (A, B) The efficiency of GLI2 silencing in T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cells was detected by qRT-PCR and western blotting. (C–D) Cell viability abilities of T24-Gem, T24-CDDP, UMUC3-Gem and UMUC3-CDDP cells treated with different concentrations of Gemcitabine or Cisplatin at 72 h after transfection were evaluated by CCK-8 assays. Data are presented as mean ± Standard Error of Mean (SEM) from three independent replicates. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BC

Bladder cancer

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FC

Fold change

- OS

Overall survival

- LASSO

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator

- GSEA

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- OD

Optical density

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- aDCs

Activated dendritic cells

- Tfh

T follicular helper

- Th1

T helper type 1

- Th2 cells

T helper type 2

- APC

Antigen-presenting cell

- CCR

Chemokine receptor

- HCM

Hyper-trophic cardiomyopathy

- ARVC

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

- RI

Resistant index

- siFASN

SiRNAs targeting FASN

- CDK6

Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 6

- PDGFRA

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor Alpha

- NTRK

Neurotrophic Tyrosine Kinase Receptor

- FASN

Fatty acid synthase

- HCM

Hyper-trophic cardiomyopathy

- ARVC

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

Author contributions

K.Z. Data curation (lead),Funding acquisition (lead). G.X. Data curation (equal). J.J. Formal analysis (equal). C.P. Formal analysis (equal). J.C. Methodology (equal). Y.L. Visualization (equal). W.W. Data curation (equal), writing—original draft (lead). S.P. Funding acquisition (equal).

Funding

This study was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Medicine, Health, and Science and Technology Project (No. 2022KY1297) , (No. 2023KY1253) and (No. 2024KY1720).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Keyuan Zhao and Gang Xu contributed equally to this work (co-first authors).

Contributor Information

Weihao Wang, Email: 18367531686@163.com.

Shouhua Pan, Email: 13606550587@163.com.

References

- 1.Babjuk M, Böhle A, Burger M, Capoun O, Cohen D, Compérat EM, Hernández V, Kaasinen E, Palou J, Rouprêt M, van Rhijn BWG, Shariat SF, Soukup V, Sylvester RJ, Zigeuner R. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2016. Eur Urol. 2017;71(3):461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson AG, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H, Bellmunt J, Guo G, Cherniack AD, Hinoue T, Laird PW, Hoadley KA, Akbani R, Castro MA. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell. 2018;174(4):540–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witjes JA, Bruins HM, Cathomas R, Compérat EM, Cowan NC, Gakis G, Hernández V, Espinós EL, Lorch A, Neuzillet Y, Rouanne M, Thalmann GN, Veskimäe E, Ribal MJ, van der Heijden AG. European Association of Urology guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: summary of the 2020 guidelines. Eur Urol. 2020;104:82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, Fradet Y, Lee JL. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1015–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel Ghafar MT, Morad MA, El-Zamarany EA, Ziada D, Soliman H. Autologous dendritic cells pulsed with lysate from an allogeneic hepatic cancer cell line as a treatment for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a pilot study. Int Immunopharmaco. 2020;82: 106375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obulesu M, Lakshmi MJ. Apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease: an understanding of the physiology, pathology and therapeutic avenues. Neurochem Res. 2014;39(12):2301–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson DR, Robinson DR, Wu Y-M, Wu Y-M, Lonigro RJ. Integrative clinical genomics of metastatic cancer. Nature. 2017;548(7667):297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu X, Zhang Z. Understanding the genetic mechanisms of cancer drug resistance using genomic approaches. Trends Genet. 2015;32:127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng W, Ren X, Cai J, Zhang C, Li M, Wang K, et al. A five-miRNA signature with prognostic and predictive value for MGMT promoter-methylated glioblastoma patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6(30):29285–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanca A, Lopez-Beltran A, Lopez-Porcheron K, Gomez-Gomez E, Cimadamore A. Risk classification of bladder cancer by gene expression and molecular subtype. Cancers. 2023;15:2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan S, Li S, Zhan Y, Chen X, Sun M. Immune status for monitoring and treatment of bladder cancer. Front Immunol. 2022. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.963877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raleigh DR, Raleigh DR, Choksi PK, Choksi PK, Krup AL. Hedgehog signaling drives medulloblastoma growth via CDK6. J Clin Investig. 2017;128(1):120–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu G, Diaz AK, Diaz AK, Paugh BS, Rankin SL. The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):444–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartolacci C, Andreani C, Vale G, Berto S, Melegari M. Targeting de novo lipogenesis and the Lands cycle induces ferroptosis in KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel SA, Patel SA, Hirosue S, Rodrigues P, Vojtasova E. The renal lineage factor PAX8 controls oncogenic signalling in kidney cancer. Nature. 2022;606:999–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou W, Xue M, Shi J, Yang M, Zhong W. PD-1 topographically defines distinct T cell subpopulations in urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder and predicts patient survival. Urol Oncol. 2023;38(8):685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Li Z, Skrzypczynska KM, Fang Q, Zhang W. Single-cell analyses inform mechanisms of myeloid-targeted therapies in colon cancer. Cell. 2020;181(2):442–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng SY, Brown L, Stevenson K, deSouza T, Aster JC. RhoA G17V is sufficient to induce autoimmunity and promotes T-cell lymphomagenesis in mice. Blood. 2018;132(9):935–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goubet A-G, Goubet A-G, Goubet A-G, Lordello L, Lordello L. Escherichia coli-specific CXCL13-producing TFH are associated with clinical efficacy of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade against muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(10):2280–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dizier B, Callegaro A, Debois M, Dreno B, Hersey P. A Th1/IFNγ gene signature is prognostic in the adjuvant setting of resectable high-risk melanoma but not in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;7:1725–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo X, Zhang Y, Zheng L, Zheng C, Song J. Global characterization of T cells in non-small-cell lung cancer by single-cell sequencing. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crabb SJ, Douglas J. The latest treatment options for bladder cancer. Br Med Bull. 2018;128(1):85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Liu H, Li Z, Zhao Z, Yip-Schneider M. Role of fatty acid synthase in gemcitabine and radiation resistance of pancreatic cancers. Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;2(1):89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng WW, Wilkins O, Bang S, Ung M, Li J. CD36-mediated metabolic rewiring of breast cancer cells promotes resistance to HER2-targeted therapies. Cell Rep. 2019;29(11):3405–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu H, Wu X, Dong Z, Luo Z, Zhao Z. Fatty acid synthase causes drug resistance by inhibiting TNF-α and ceramide production. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:776–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knowles LM, Smith JW. Genome-wide changes accompanying knockdown of fatty acid synthase in breast cancer. BMC Genomics. 2007;8(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 (PNG 884 KB) Fig.S1 Drug Sensitivity Analysis. (A–K) IC50 of Tipifarnib (A), SB590885 (B),QS11 (C), Pyrimethamine (D), PAC.1 (E), Methotrexate (F), GW.441756 (G), Etoposide (H), BIRB.0769 (I), Eriotinib (J), ATRA (K) in high and low-risk groups.

Supplementary file2 (TIF 1786 KB) Fig.S2 Drug Sensitivity Analysis. (A–X) IC50 of AZD.0530 (A), Bexarotene(B), Bicalutamide (C), AZD6482 (D), BMS.509744 (E), BMS.536924(F), BX.795 (G), CGP.082996 (H), CHIR.99021 (I), CMK (J), GDC0941 (K), Cyclopamine (L), Dasatinib (M), DMOG (N), Embelin (O), GNF.2 (P), GSK269962A (Q), Lmatinib (R), JNJ.26854165 (S), KIN001.135 (T), NU.7441 (U), Midostaurin (V), MG.132 (Y), KU.55933 (X) in high and low-risk groups.

Supplementary file3 (PNG 457 KB) Fig.S3 The relationship between each of the four apoptosis and chemotherapy related genes and clinical features. (A-E) The relationship between GLI2 expression and Survival Status, Grade, Gender, and T Stage. (F–J) The relationship between PDGFRA expression and Survival Status, Gender, Grade, Stage, and T Stage. (K) The relationship between VHL and Gender. (L–P) The relationship between the risk score and Survival Status, Gender, Grade, Stage, and T Stage.

Supplementary file4 (TIF 387 KB)Fig.S4 Validation of Gemcitabine resistance in BC cell lines. (A, B) The efficiency of GLI2 silencing in T24-Gem and UMUC3-Gem cells was detected by qRT-PCR and western blotting. (C–D) Cell viability abilities of T24-Gem, T24-CDDP, UMUC3-Gem and UMUC3-CDDP cells treated with different concentrations of Gemcitabine or Cisplatin at 72 h after transfection were evaluated by CCK-8 assays. Data are presented as mean ± Standard Error of Mean (SEM) from three independent replicates. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test).

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.