Abstract

Background

Metabolic profiling of blood metabolites, particularly in plasma and serum, is vital for studying human diseases, human conditions, drug interventions and toxicology. The clinical significance of blood arises from its close ties to all human cells and facile accessibility. However, patient-specific variables such as age, sex, diet, lifestyle and health status, along with pre-analytical conditions (sample handling, storage, etc.), can significantly affect metabolomic measurements in whole blood, plasma, or serum studies. These factors, referred to as confounders, must be mitigated to reveal genuine metabolic changes due to illness or intervention onset.

Review objective

This review aims to aid metabolomics researchers in collecting reliable, standardized datasets for NMR-based blood (whole/serum/plasma) metabolomics. The goal is to reduce the impact of confounding factors and enhance inter-laboratory comparability, enabling more meaningful outcomes in metabolomics studies.

Key concepts

This review outlines the main factors affecting blood metabolite levels and offers practical suggestions for what to measure and expect, how to mitigate confounding factors, how to properly prepare, handle and store blood, plasma and serum biosamples and how to report data in targeted NMR-based metabolomics studies of blood, plasma and serum.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11306-025-02259-7.

Keywords: Metabolomics, Standardization, Blood, Serum, Plasma, NMR, Metabolites

Introduction

Metabolomics offers a powerful approach to monitor the chemical response of biological systems to internal and external perturbations. In particular, the comprehensive measurement of metabolite changes in selected tissues or biofluids can provide a detailed, molecular snapshot of the down-stream effects of physiological, environmental, pathological or genetic changes and exposures. In this regard, metabolomics offers a very powerful route to measure the chemical phenotype of an organism (Wishart, 2016). In addition to serving as a useful vehicle to perform rapid and inexpensive molecular phenotyping, metabolomics is increasingly being integrated with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to provide a more complete molecular understanding of biological systems (Jendoubi, 2021; Patt et al., 2019; Wishart, 2022).

Metabolomic analyses can be either untargeted or targeted. Untargeted methods attempt to measure all detectable features in the investigated samples, typically without absolute metabolite quantification. In targeted metabolomics, a pre-selected set of metabolites is identified and (often) absolutely quantified in each sample. Multivariate statistics are then used to determine a set ofmetabolites, either feature-based in the untargeted approach or based on their absolute concentrations in the targeted approach, significantly associated with the response of interest, e.g., a phenotype (Barba et al., 2009; DeSilva et al., 2009; Jung et al., 2013; H. S. Kim et al., 2009; Moussallieh et al., 2014; Porzel et al., 2014; Schicho et al., 2010; Van Doorn et al., 2007). Untargeted metabolomics is ideal for exploratory analysis and novel metabolite discovery, while targeted metabolomics is most suited for clinical applications and biomarker discovery (Patti et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2012; Schrimpe-Rutledge et al., 2016; Wishart, 2016).

Both targeted and untargeted metabolomics can be done on a wide range of analytical platforms, including liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC–MS), gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC–MS), inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP–MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. NMR and MS methods are the most commonly used analytical approaches with each method having its own strengths and weaknesses. In terms of strengths, MS is highly sensitive, offers broad metabolite coverage and requires only micrograms or nanograms of sample (Letertre et al., 2021). However, MS is an inherently destructive technique, requiring substantial sample preparation with limited ability to perform accurate quantification (X. Liu & Locasale, 2017). On the other hand, NMR is a non-destructive technique that is highly reproducible, requires little-to-no sample preparation, is very amenable to full automation and offers facile, accurate quantification (Wishart et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). However, NMR is much less sensitive than MS, has much more limited metabolite coverage and often needs milligrams of material (Edison et al., 2021).

Regardless of the choice of method (targeted or untargeted) or analytical platform (NMR, LC–MS or GC–MS), the selection, collection and handling of the biological samples is of paramount importance in metabolomic studies. Traditionally, most metabolomic studies have focused on the analysis of biofluids (blood, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid) or excreta (urine or feces), as these are more easily collected. The most popular and most important biofluid in clinical metabolomics is blood.

Blood is a specialized body fluid that has four main components: plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. It is the carrier by which oxygen, nutrients, metabolites and drugs are transported throughout the body and it directly or indirectly (via interstitial fluids between various blood/organ barriers) reaches all living cells. Blood maintains homeostasis in the body via several continuous regulatory mechanisms. Because it touches every organ and collects and delivers both essential and waste products, blood has played a pivotal role in many areas of biomedical science, including the assessment of human health, the search for new disease biomarkers, the exploration of the effects of dietary intake on health, the monitoring of drug or surgical interventions, and the investigation of drug toxicity (Angioni et al., 2022; Farley et al., 2013; Krewski et al., 2010; Schwedes et al., 2002; Ubaida-Mohien et al., 2023).

While blood is perhaps the ideal biofluid to monitor health via metabolomics, the challenges of storing and preserving blood for metabolomic studies have forced most researchers to use cell-free versions of blood—namely plasma and serum. Serum is the straw-colored liquid portion that remains after the blood has clotted, while plasma is the liquid portion that remains when clotting is prevented with the addition of an anticoagulant. Both serum and plasma contain metabolites and proteins, and both are easily prepared via centrifugation. While plasma and serum are widely thought to be very uniform and very similar in chemical composition (certainly much more so than urine), many different factors, including genetics, age, sex, diet, physical activities and lifestyle, can affect their metabolic composition. Additionally, the collection and storage conditions of serum or plasma specimens—referred to as pre-analytical factors—can significantly affect metabolite concentrations. These include donor diurnal variations, emotional or physical stress, collection temperature, collection methods, collection tubes, processing times, storage temperatures and storage time. These confounders can complicate the interpretation of metabolomic data, the assessment of health status and the discovery of novel biomarkers. Some of these factors can be easily controlled during the sampling, pre-analytical and analytical phases of a metabolomics study while others are often beyond the control of the researcher (Fig. 1).

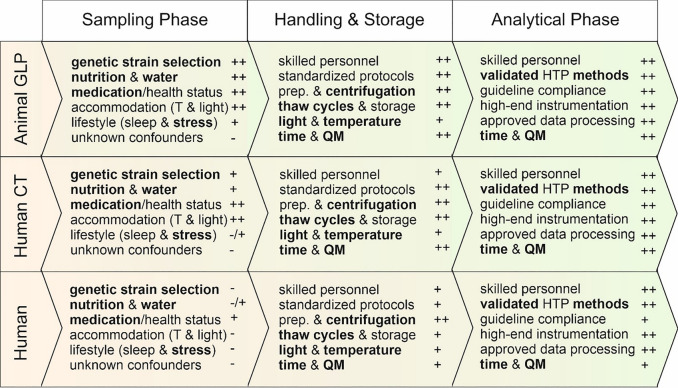

Fig. 1.

Operative phases, confounding factors* and associated uncertainties (−)** for in-vitro metabolome studies in humans and animals. Animal testing as part of good laboratory practice (GLP) provide the highest level of controllability (+ +)**. Similar favorable conditions can be found in human clinical trials (CT) where the most important confounding variables can be well controlled. In human field studies, important parameters are placed in the test subjects' confidence range. This leads to uncertainties within a study, which can no longer be fully compensated for. Thus, good planning, extensive standardization, efficient quality management, and detailed collection and reporting of potential confounding variables is a guarantee for high-quality metabolome studies. There is currently no global standard for conducting metabolome studies. *the most critical factors are in bold; **rough estimate, whereby (−) indicates little controllable and ( +) well controllable; prep. = sample preparation; QM = quality management; HTP = high throughput

Over the past 15 years, a number of excellent reviews on blood, plasma and serum metabolomics (and metabolomes) have been published (Bar et al., 2020; James & Parkinson, 2015; Kalantari & Nafar, 2019; Kondoh et al., 2020; Likhitweerawong et al., 2021; Psychogios et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2021; Serkova et al., 2011; Trabado et al., 2017; A. Zhang et al., 2012). Most have focused on the application of MS-based approaches to analyze the metabolome of blood/serum/plasma for specific diseases or conditions such as autism, various cancers, dementia, chronic kidney disease, sepsis or aging (Kalantari & Nafar, 2019; Kondoh et al., 2020; Likhitweerawong et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2021; Serkova et al., 2011; A. Zhang et al., 2012). A smaller number of papers have focused on NMR-based approaches to analyze the metabolome of blood/serum/plasma (Nagana Gowda & Raftery, 2017, 2019; Nagana Gowda et al., 2022; Schicho et al., 2012; Silva et al., 2020; Soininen et al., 2015; Würtz et al., 2017). An even smaller number reviewed the analytical aspects of blood/serum/plasma metabolomics (sample preparation, sample processing, metabolite extraction/filtering, separation methods, sample referencing, batch corrections, and data processing) (Beckonert et al., 2007; Lipfert et al., 2019; Madrid-Gambin et al., 2023; Snytnikova et al., 2019; Wishart et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). Recent advancements, particularly the ISO 23118: 2021- “Molecular in vitro diagnostic examinations—specifications for pre-examination processes in metabolomics in urine, venous blood serum and plasma” standard, provide guidelines for pre-examination processes in urine, venous blood plasma, and serum for metabolomics (IOS, 2021). This standard outlines detailed recommendations for handling, documentation, and processing to ensure the reliability of metabolomics studies. The latest additional guidelines particularly focus on the pre-examination phases of multi-center metabolomic studies (Ghini et al., 2022) and on the pre-analytical factors influencing metabolomic studies (Thachil et al., 2024) without considering patient associated factors. However, there is a lack of comprehensive guidelines on the best practices for the preparation of these blood samples, or on the expected compounds in targeted NMR-based metabolomics studies. Moreover, increased awareness of the impact of diet, sex, gender, lifestyle, and gut microbiota on metabolite levels in blood highlights the significance of considering and controlling these pre-analytical factors. These variables are crucial for the accurate interpretation of metabolite data in blood, serum, or plasma, as they can lead to potential misinterpretations if not properly accounted for.

The main purpose of this review is to assist metabolomics researchers in conducting well-designed, well-controlled studies so that reliable, standardized, shareable datasets from targeted or untargeted, NMR-based metabolomics of blood, plasma or serum can be obtained. This document is divided into five parts. The first part of this review focuses on what is known about the blood, serum and plasma metabolomes as measured by various NMR techniques. This is important for understanding the subsequent topics and caveats discussed in this review. In part two of this review, we will focus on the participant or patient-specific confounders and highlight how significant these effects are especially when it comes to biomarker discovery. The third part of this review discusses the effects of sample handling, sample storage and sample preparation on NMR-detectable blood, plasma and serum metabolites. The fourth part discusses the results of a literature review conducted to assess the common practices among labs conducting NMR-based metabolomics studies of blood, serum or plasma. A number of shortcomings in current practices and reporting methods are highlighted. The fifth part of this review focuses on providing recommendations regarding the use of appropriate methods to reduce pre-analytic variability and improve reporting practices. This includes recommendations for optimizing study design, cohort/subject data collection, sample selection, sample collection, and sample preparation of blood, serum or plasma for NMR-based metabolomics. We anticipate that these descriptions, recommendations, and assessments will enhance the quality of NMR-based metabolomics studies performed on human blood, plasma and serum.

Defining the whole blood, serum and plasma metabolomes as measured by NMR

As highlighted earlier, whole blood, plasma, and serum are fundamentally different in their preparation methods, with detectable differences in their composition. Whereas large scale, multi-platform (NMR, GC–MS, LC–MS, ICP-MS) studies have described or reviewed the metabolite content of human plasma and serum (Lawton et al., 2008; Psychogios et al., 2011; Trabado et al., 2017; Wishart, Guo, et al. 2022), there has been no detailed summary of the NMR-measurable metabolite content of serum, plasma or blood. Given this paucity of information, we believe a short summary of what is known about the NMR-measurable metabolite content of serum, plasma or blood would be quite useful. The detection limit for biomolecules using NMR methods (typically in the micromolar range) is generally one to two orders of magnitude (10- to 100-fold) less sensitive than commonly applied LC–MS metabolomics methods. Thus, in NMR metabolomics of blood, typically only about 50–100 metabolites are detected, whereas LC/GC–MS methods can detect far more than 1000 metabolites (Mandal et al., 2025). Likewise, the number of detectable compounds also depends on the sample preparation or sample pre-treatment protocols applied to each biofluid, the NMR pulse sequences applied, the NMR spectrometer frequency and the target(s) of the chemical analysis.

Blood, serum, and plasma consist of a complex mixture of both large molecules (proteins, lipoprotein complexes, and lipid vesicles) and numerous small molecules. In a given NMR spectrum, the signals from all these components are superimposed on top of each other. In particular, the signals from the large molecules tend to be much more intense than the small molecule metabolites. NMR samples are usually analyzed without chromatographic separation (such as GC or LC), which results in complex, highly overlapped spectra. The analytical complexity is further increased by the presence of both large molecules (proteins, lipoprotein complexes, lipid vesicles) and small molecules (metabolites). Without signal suppression or separation of the large molecules, the NMR signals from these macromolecules interferes with the small molecule signals. This interference leads to difficulties in identifying and quantifying the small molecule metabolites (or to properly measure large molecules—if desired). Removal of the proteins (deproteinization) as well as the lipids and lipoproteins (delipidization) is commonly done to enhance metabolite signals in NMR. This can be done chemically by solvent (methanol) extraction (Nagana Gowda & Raftery, 2014; Nagana Gowda et al., 2015) or mechanically by ultrafiltration (Psychogios et al., 2011; Rout et al., 2023; Wevers et al., 1994). It can also be done spectroscopically using the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence which takes advantage of the T2 relaxation time differences between large molecules and small molecules in NMR (Beckonert et al., 2007; Nagana Gowda et al., 2015). Because of its simplicity, the use of the CPMG “spectroscopic filtering” method in blood metabolomics has been and still is widely used, in particular, for semi-quantitative, untargeted metabolomics studies. In comparison to chemical or mechanical deproteinization and delipidization, the CPMG method can be employed on blood/serum/plasma specimens without any additional sample preparation steps, typically lowering consumable costs, workload, and sources of unwanted pre-analytical variability. Therefore, the CPMG method is particularly advantageous for the analysis of large-scale metabolomics studies involving hundreds to thousands of specimens. However, the CPMG method does not completely remove large molecule signals, and, because of various uncontrollable signal suppression effects, it makes the quantification of metabolite levels very difficult and inconsistent (Bliziotis et al., 2020; Nagana Gowda et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, over the past 10 years, it has been recognized that NMR of intact serum and plasma (i.e. with all intrinsic proteins and lipids) can provide very useful quantitative information about lipid and lipoprotein content—as well as some number of small molecules (Cacciatore et al., 2021; Funderburg et al. 2017; Jeyarajah et al., 2006; Julkunen et al., 2023; Lodge et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2020; Sliz et al., 2018; Zeleznik et al., 2023). Therefore, we provide a list of small molecules measured by traditional NMR methods employing ultrafiltration or methanol extraction/lyophilization, as well as metabolites, lipids, proteins and lipoproteins identified in intact plasma via the Nightingale (See Table 1, “Serum concentrations” or “Plasma concentrations” (Julkunen et al., 2023)) as well as the Bruker IVDr Quantification Engine for Human Plasma & Serum (B.I. Quant-PS) (38 metabolites; see Table 1, “Whole serum” column) (Jiménez et al., 2018; Trautwein, 2025)) approaches, currently the most popular approaches for serum/plasma characterization by NMR. It is also worth noting that LabCorp (LipoScience) has developed a similar assay or platform for measuring lipids and lipoproteins in intact serum and plasma (Funderburg et al. 2017; Jeyarajah et al., 2006).

Table 1.

List of metabolites which can be measured using 1D 1H NMR in whole blood, plasma or serum, after various sample preparation methods

| Name | HMDB | Ultra-filtration (Rout et al., 2023) | Deproteinization (Nagana Gowda & Raftery, 2019; Nagana Gowda et al., 2015) | Cell Lysisa (Nagana Gowda & Raftery, 2017; Nagana Gowda et al., 2022) | Whole Serum (Julkunen et al., 2023; Zeleznik et al., 2023) | Lipid Extraction (Julkunen et al., 2023; Zeleznik et al., 2023) | Serum concentrations (µmol/L)b,c | Plasma concentrations (µmol/L)b,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Methylhistidine | HMDB0000001 | * | * |

7.1 ± 1.3 (4.6–9.1) |

– | |||

| 2-Hydroxybutyrate | HMDB0000008 | * | * | *d |

48.1 ± 16.6 (25.0–81.8) |

14.5 | ||

| 3-Hydroxybutyrate | HMDB0000011 | * | * | *d,e |

60.5 ± 62.1 (0.0–3843.4) |

215.9 ± 127.3 (59.1–1570.0) | ||

| 2-Oxoisovalerate | HMDB0000019 | * | 3.2 | – | ||||

| Acetate | HMDB0000042 | * | * | *d,e |

18.7 ± 33.0 (0.0–1800.6) |

44.8 ± 31.2 (19.4–940.0) | ||

| Betaine | HMDB0000043 | * | * |

43.5 ± 11.9 (18.7–59.8) |

7.4 | |||

| AMP | HMDB0000045 | * | – | – | ||||

| Carnitine | HMDB0000062 | * | * |

39.5 ± 5.8 (29.1–45.3) |

18.7 | |||

| Creatine | HMDB0000064 | * | * | *d |

34.1 ± 21.2 (12.3–70.5) |

17.1 | ||

| Glycerophosphocholine | HMDB0000086 | * | – | – | ||||

| Dimethylamine | HMDB0000087 | * | – | – | ||||

| Dimethylglycine | HMDB0000092 | * | * | *d |

2.7 ± 1.0 (1.4–4.7) |

0.8 | ||

| Citrate | HMDB0000094 | * | * | *d,e |

65.6 ± 13.2 (3.4–572.0) |

111.6 ± 18.0 (60.4–245.0) | ||

| Choline | HMDB0000097 | * | * | *d |

8.6 ± 2.1 (5.8–12.6) |

6.1 | ||

| Ethanol | HMDB0000108 | * | *d |

17.7 ± 11.1 (7.1–42.0) |

69 | |||

| Galactose | HMDB0000143 | *d | ||||||

| Glucose | HMDB0000122 | * | * | *d,e |

3747.8 ± 1192.1 (289.5–41,833.0) |

4437.8 ± 1430.3 (2120.0–22,700.0) | ||

| Glycine | HMDB0000123 | * | * | *d,e |

171.0 ± 66.7 (0.0–793.2) |

257.4 ± 37.6 (159.0–555.0) | ||

| Glutathione | HMDB0000125 | * | – | – | ||||

| Glycerol | HMDB0000131 | * | * | *d,e |

252.1 ± 76.6 (193.3–423.5) |

88.9 ± 23.2 (20.6–212.0) | ||

| Fumarate | HMDB0000134 | * | * | – | – | |||

| Formate | HMDB0000142 | * | * | *d |

42.1 ± 3.5 (35.2–48.6) |

– | ||

| Glutamate | HMDB0000148 | * | * | *d |

35.1 ± 27.7 (12.5–96.7) |

– | ||

| Hypoxanthine | HMDB0000157 | * | * |

5.2 ± 1.6 (3.4–7.9) |

– | |||

| Tyrosine | HMDB0000158 | * | * | *d,e |

63.0 ± 14.5 (5.5–389.4) |

49.7 ± 9.7 (22.9–120.0) |

||

| Phenylalanine | HMDB0000159 | * | * | *d,e |

47.2 ± 11.6 (5.2–1309.2) |

72.7 ± 10.9 (44.3–355.0) | ||

| Alanine | HMDB0000161 | * | * | *d,e |

296.6 ± 78.5 (61.3–1272.6) |

382.5 ± 56.9 (232.0–739.0) | ||

| Proline | HMDB0000162 | * | * | *d |

140.4 ± 40.6 (72.3–198.3) |

84.5 | ||

| Threonine | HMDB0000167 | * | * | *d |

126.4 ± 21.6 (95.2–160.3) |

86 | ||

| Asparagine | HMDB0000168 | * | * | *d |

55.8 ± 11.7 (37.4–78.0) |

44.7 | ||

| Mannose | HMDB0000169 | * | * |

41.3 ± 6.3 (31.9–53.8) |

13.7 | |||

| Isoleucine | HMDB0000172 | * | * | *d,e |

51.1 ± 18.2 (0.0–240.5) |

56.8 ± 17.8 (20.5–235.0) | ||

| Inosine monophosphate | HMDB0000175 | * | – | – | ||||

| Histidine | HMDB0000177 | * | * | *d,e |

65.6 ± 11.4 (21.2–657.4) |

58.9 ± 8.9 (24.0–109.0) |

||

| Lysine | HMDB0000182 | * | * | *d |

195.5 ± 37.9 (132.7–236.1) |

101.4 | ||

| Serine | HMDB0000187 | * | * |

109.1 ± 24.5 (79.1–152.9) |

72.1 | |||

| Lactate | HMDB0000190 | * | * | *d,e | 3873.7 ± 1141.1 (722.2–21,248.0) | 1454.8 ± 489.0 (543.0–3940.0) | ||

| Aspartate | HMDB0000191 | * | * |

5.0 ± 2.2 (0.0–8.4) |

– | |||

| Acetylcarnitine | HMDB0000201 | * | * |

10.8 ± 6.1 (5.5–27.0) |

6.3 | |||

| Oxoglutarate | HMDB0000208 | * | *d |

7.8 ± 2.4 (4.2–12.3) |

– | |||

| Myoinositol | HMDB0000211 | * | 22.4 | 27.2 | ||||

| Ornithine | HMDB0000214 | * | * | *d |

78.7 ± 17.9 (49.2–113.7) |

27.2 | ||

| NADPH | HMDB0000221 | * | – | – | ||||

| Pyruvate | HMDB0000243 | * | *d,e |

79.8 ± 32.5 (1.0–1847.8) |

87.9 ± 24.4 (34.1–232.0) | |||

| Succinate | HMDB0000254 | * | * | *d |

3.6 ± 1.5 (0.0–5.4) |

4.8 | ||

| Sucrose | HMDB0000258 | * | – | – | ||||

| Phosphoenolpyruvate | HMDB0000263 | * | – | – | ||||

| Pyroglutamate | HMDB0000267 | * | – | – | ||||

| Sarcosine | HMDB0000271 | * | * | *d |

1.9 ± 1.0 (0.7–4.1) |

– | ||

| Trimethylamine-N-oxide | HMDB0000925 | *d | ||||||

| Uridine diphosphate-glucose | HMDB0000286 | * | – | – | ||||

| Uridine monophosphate | HMDB0000288 | * | – | – | ||||

| Uridine diphosphate–N–acetylglucose | HMDB0000290 | * | – | – | ||||

| Xanthine | HMDB0000292 | * | – | – | ||||

| Urea | HMDB0000294 | * | 1716.9 ± 556.8 (944.7–2776.9) | – | ||||

| Uridine | HMDB0000296 | * | – | – | ||||

| 2–Hydroxyisovalerate | HMDB0000407 | * | * |

4.7 ± 2.4 (2.8–11.1) |

– | |||

| 2-Aminobutyrate | HMDB0000452 | * | * | *d |

19.7 ± 6.7 (5.3–27.4) |

– | ||

| Allantoin | HMDB0000462 | * | – | – | ||||

| 3-Methylhistidine | HMDB0000479 | * | – | – | ||||

| 3-Methyl-2-oxovalerate | HMDB0000491 | * | * |

2.6 ± 1.9 (0.0–5.2) |

16.4 | |||

| Arginine | HMDB0000517 | * | * |

78.1 ± 22.5 (29.6–121.3) |

– | |||

| N-Acetylglycine | HMDB0000532 | * | – | – | ||||

| ATP | HMDB0000538 | * | – | – | ||||

| Creatinine | HMDB0000562 | * | * | *e |

67.4 ± 15.5 (15.1–940.8) |

71.4 ± 18.3 (26.4–438.0) | ||

| Glutamine | HMDB0000641 | * | * | *d,e |

554.4 ± 85.3 (84.4–1881.8) |

469.2 ± 67.7 (96.5–781.0) | ||

| Leucine | HMDB0000687 | * | * | *d,e |

103.8 ± 28.9 (13.7–447.7) |

77.5 ± 17.0 (32.1–260.0) | ||

| Malonate | HMDB0000691 | * |

7.8 ± 3.4 (2.9–12.6) |

– | ||||

| Ketoleucine | HMDB0000695 | * | * |

4.6 ± 1.2 (2.6–6.8) |

– | |||

| Methionine | HMDB0000696 | * | * | *d |

27.4 ± 3.5 (20.0–30.9) |

15 | ||

| Hippurate | HMDB0000714 | * | – | – | ||||

| Isovalerate | HMDB0000718 | * | – | – | ||||

| 3-Hydroxyisovalerate | HMDB0000754 | * | * |

1.5 ± 0.7 (0.0–2.8) |

– | |||

| Isopropanol | HMDB0000863 | * |

1.9 ± 1.2 (0.9–4.9) |

– | ||||

| Valine | HMDB0000883 | * | * | *d,e |

210.3 ± 43.5 (67.4–847.7) |

157.9 ± 27.6 (62.8–372.0) | ||

| NAD + | HMDB0000902 | * | – | – | ||||

| Tryptophan | HMDB0000929 | * | * |

2.8 ± 1.5 (0.3–5.1) |

27 | |||

| 2,3-diphosphoglycerate | HMDB0001294 | * | – | – | ||||

| ADP | HMDB0001341 | * | – | – | ||||

| Guanosine monophosphate | HMDB0001397 | * | – | – | ||||

| Nicotinamide | HMDB0001406 | * | – | – | ||||

| NADH | HMDB0001487 | * | – | – | ||||

| Phosphocholine | HMDB0001565 | * | – | – | ||||

| Acetone | HMDB0001659 | * | *d,e |

14.2 ± 5.6 (2.3–421.2) |

– | |||

| Benzoate | HMDB0001870 | * | – | – | ||||

| Isobutyrate | HMDB0001873 | * | * |

7.1 ± 2.8 (3.7–11.4) |

5.7 | |||

| Methanol | HMDB0001875 | * |

39.4 ± 17.6 (21.8–62.9) |

161 | ||||

| Propylene glycol | HMDB0001881 | * | * |

57.9 ± 24.0 (22.5–97.7) |

– | |||

| Glutathione disulfide | HMDB0003337 | * | – | – | ||||

| α-D-Glucose-1,6-biphosphate | HMDB0003514 | * | – | – | ||||

| Dimethyl sulfone | HMDB0004983 | * | *d |

10.1 ± 5.5 (4.7–19.5) |

– | |||

| Acetoacetate | HMDB0304256 | * | *d,e |

13.2 ± 12.5 (0.0–758.2) |

90.1 ± 62.7 (0.0–860.0) |

|||

| NADP + | HMDB0304435 | * | – | – | ||||

| Glycoprotein acetylation (GlycA) | NA | *e |

812.3 ± 120.3 (274.8–1884.7) |

1332.8 ± 259.9 (717.0–4920.0) | ||||

| Chylomicrons/VLDL (6 subclasses) | NA | *f,g |

0.1 ± 0.0 (0.0–0.6) |

0.1 ± 0.0 (0.0–0.5) |

||||

| LDL (3 subclasses) | NA | *f,g |

1.2 ± 0.3 (0.1–3.5) |

0.5 ± 0.1 (0.0–1.2) |

||||

| IDL | NA | *f,g |

0.3 ± 0.1 (0.1–0.9) |

0.1 ± 0.0 (0.0–0.3) |

||||

| HDL (4 subclasses) | NA | *f,g |

15.3 ± 2.5 (2.4–36.7) |

7.8 ± 0.8 (0.0–14.5) |

||||

| Apolipoprotein A1 | NA | *h |

52.1 ± 8.8 (10.8–123.5) |

49.7 ± 5.8 (29.1–74.7) |

||||

| Apolipoprotein B | NA | *h |

1.6 ± 0.4 (0.3–4.8) |

1.9 ± 0.4 (0.7–5.4) |

||||

| Free cholesterol | HMDB0000067 | * | 1266.7 ± 271.9 (230.1–3430.8) | 1346.2 ± 267.0 (477.0–3030.0) | ||||

| Cholesterol esters | NA | * |

3368.2 ± 685.4 (512.8–8405.8) |

3165.0 ± 669.3 (791.0–6040.0) | ||||

| Average fatty acid chain length | NA | * | – |

17.5 ± 0.3 (16.5–19.0) |

||||

| Average fatty acid saturation degree | NA | * |

1.4 ± 0.1 (0.9–3.0) |

1.2 ± 0.1 (0.9–1.5) |

||||

| Omega-3 fatty acids | NA | * |

532.9 ± 223.1 (1.0–4156.4) |

449.9 ± 152.5 (145.0–2070.0) | ||||

| Omega-6 fatty acids | NA | * |

4512.4 ± 692.4 (1005.3–16,411.0) |

3645.4 ± 730.1 (1060.0–10,800.0) | ||||

| Lineolic acid | HMDB0000673 | * |

3463.5 ± 694.7 (4.9–16,411.0) |

2980.6 ± 657.7 (792.0–9810.0) | ||||

| Docosahexaenoic acid | HMDB0002183 | * |

237.1 ± 84.2 (0.3–1789.8) |

157.2 ± 59.1 (38.1–678.0) |

||||

| Triglycerides | NA | * |

1321.0 ± 588.8 (179.2–8401.5) |

1568.9 ± 749.5 (421.0–9450.0) | ||||

| Phosphatidylcholines | NA | * |

2110.0 ± 381.1 (0.0–5697.4) |

1780.8 ± 311.5 (687.0–3440.0) | ||||

| Phosphoglycerides | NA | * |

2296.4 ± 405.0 (109.4–6112.4) |

1781.7 ± 328.9 (625.0–3540.0) | ||||

| Sphingomyelins | NA | * |

451.9 ± 73.3 (115.2–979.2) |

435.6 ± 81.8 (162.0–822.0) |

||||

| Albumin | NA | * |

587.7 ± 50.7 (0.0–1074.8) |

– | ||||

| Monounsaturated Fatty Acids | NA | * |

2904.2 ± 837.3 (0.0–13,077.0) |

3033.4 ± 904.6 (1110.0–15,000.0) | ||||

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids | NA | * |

5045.3 ± 815.0 (1006.3–19,399.0) |

4095.0 ± 811.6 (1210.0–11,700.0) | ||||

| Saturated Fatty Acids | NA | * |

4128.0 ± 969.5 (0.0–17,514.0) |

4175.5 ± 921.4 (1620.0–14,600.0) |

a—listing only uniquely identified compounds. b—mean values, standard deviations, and ranges, when available. c—references: (Madrid-Gambin et al., 2023; Nagana Gowda & Raftery, 2014; Rout et al., 2023); https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ukb/label.cgi?id=220; https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ucl.ac.uk%2Fepidemiology-health-care%2Fsites%2Fepidemiology_health_care%2Ffiles%2Fbrhs_1998-2000_q20_20_year_follow-up_metabolites_data_dictionary_v1.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK. d—metabolites quantified by B.I. Quant-PS (Trautwein, 2025). e—using CPMG pulse sequence. f—methods include using lineshape fitting (Jeyarajah et al., 2006), statistical methods/machine learning (Ala-Korpela et al., 1995) or diffusion spectroscopy (Mallol et al., 2015). g—number and naming of subclasses may differ between tests (Balling et al., 2020; Rief et al., 2022). h—measured using partial least squared (PLS) or neural network analysis (Bathen et al., 2000)

As can be seen from this table, the number of metabolites identifiable by NMR in deproteinized/delipidated serum and plasma as prepared via ultrafiltration is identical for both biofluids and includes typically 57–58 compounds (Bahado-Singh et al., 2018; Mandal et al., 2025; Rout et al., 2023). The number of metabolites identifiable by NMR in deproteinized/delipidated serum and plasma prepared by methanol extraction/lyophilization is also identical and includes typically 67–71 compounds (Nagana Gowda & Raftery, 2019; Nagana Gowda et al., 2015). The compounds that are most different between samples prepared via the methanol vs. ultrafiltration methods include acetone, dimethylamine, ethanol, hippurate, isopropanol, methanol, sucrose and urea (Table 1). These differences are primarily due to the volatility of some compounds (which are lost due to lyophilization) as well as the concentration effects enabled by methanol extraction. Furthermore, compounds showing strong protein binding can only be assessed following methanol extraction. On the other hand, we would like to point out that, due to the necessary drying step, methanol extraction is not suitable for the analysis of volatile compounds, and traces of exogenous methanol, even after careful drying, will be found in the corresponding NMR spectra. Interestingly, the number of compounds identifiable by NMR in deproteinized/delipidated whole blood, as prepared via methanol extraction/lyophilization is ~ 90 (Nagana Gowda et al., 2022). This is nearly 30% more than seen with plasma or serum prepared in the same manner. The reason for this difference is due to the release of red blood cell contents (which include many cofactors and redox molecules) into the medium during the blood sample work-up (Nagana Gowda et al., 2022).

In contrast to the deproteinized/delipidated samples, when “intact” plasma is analyzed by NMR, the number of metabolites and lipoprotein components that can be identified can be as high as 168, including 150 lipid, protein and lipoprotein components and 18 small molecules when employing the Nightingale assay (Julkunen et al., 2023; Zeleznik et al., 2023), and up to a total of 112 different lipoprotein subclasses and 38 individual metabolites when employing the Bruker IVDr system (Jiménez et al., 2018; Trautwein, 2025). Note that the number of small molecules identifiable in intact plasma is significantly lower than what is achievable in deproteinized/delipidated plasma. This is primarily due to the extensive overlap of lipid or lipoprotein signals, leading to the loss of identifiable peaks associated with small molecule metabolites. On the other hand, the ability to identify many lipoprotein or cholesterol components including high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) fractions in intact plasma provides a very informative picture of many key cardiovascular disease markers (Patrizia Bernini et al., 2011a, 2011b; Khakimov et al., 2022).

The fact that different components of blood (i.e., whole blood, serum or plasma), prepared or processed in different ways and analyzed with different analytical techniques, can lead to different chemical compositions is important to remember. Likewise, this list of compounds is useful to recall when discussing the pre-analytical or environmental factors (such as diet, microbiome, collection or storage conditions) that influence NMR-measurable metabolite levels in human plasma, serum or whole blood.

As Table 1 shows, if the sample preparation method is identical, the chemical composition of serum and plasma are essentially identical. However, the concentrations of specific metabolites will certainly differ between plasma and serum. This is evident in the concentration ranges reported for ultracentrifuged serum/plasma as measured by NMR (Table 1). This NMR-derived information agrees with the study by Liu et al. (L. Liu et al., 2010) who used GC–MS to investigate the metabolome differences between serum and plasma. They measured the concentration levels of 72 metabolites in human plasma and compared them to the corresponding serum samples (L. Liu et al., 2010). They found that 29 metabolites were at higher concentrations in serum than plasma, while 7 metabolites in plasma were at higher concentrations than serum. Of these, only 24 metabolites are relevant to NMR studies. Of the NMR-relevant metabolites, most amino acids were at higher levels in serum, while citrate and pyruvate were more elevated in plasma samples (L. Liu et al., 2010). Similar results were also found in another publication that used LC–MS to quantify metabolites in serum and plasma, and higher levels of several amino acids such as glycine, serine, arginine and phenylalanine were reported in serum samples compared to plasma (Yu et al., 2011).

In addition to these modest metabolite concentration differences, there are other differences between serum and plasma that are worth noting. The incubation time effect on metabolite concentration levels has generally been found to be more dominant in plasma when compared to serum samples (Ferreira et al., 2019; L. Liu et al., 2010). That is, the longer that plasma is left unfrozen, the more likely metabolite levels will change due to enzyme-mediated events. Additionally, the effect of freeze–thaw cycles on metabolite levels has also been found to be more prominent in plasma than serum (Saito et al., 2014). Likewise, the presence of additional signals caused by anticoagulants in plasma can reduce the number of compounds identified by NMR (Barton et al., 2009; Kennedy et al., 2021). On the other hand, the use of EDTA as an anticoagulant can facilitate the identification and absolute quantification of bivalent cations such as Mg2+ and Ca2+, otherwise invisible in NMR experiments, which form EDTA-complexes with distinct NMR signal shifts (Barton et al., 2009; Somashekar et al., 2006).

Patient-specific factors influencing metabolite levels in human blood, plasma and serum

In this section, we will focus on participant or patient-specific effects that can significantly influence NMR-detectable metabolite levels in blood, plasma and serum. Researchers need to be mindful of these effects, especially in studies focusing on metabolite-based biomarker identification. Here, we briefly review the influence of different “intrinsic” confounders on serum and plasma metabolite composition and possible ways to compensate or minimize these perturbations.

Effects of food intake

As the old adage goes: “we are what we eat”. In other words, the metabolites found in the human metabolome, including the blood, serum or plasma metabolome, are primarily derived from metabolites in our diet. While the human body itself can produce thousands of metabolites, many other compounds, such as essential amino acids, vitamins, and essential fatty acids, must come from external dietary sources. Likewise, many other food-derived xenobiotics such as polyphenols, phytosterols and alkaloids, as well as a variety of food additives, food preservatives or food colorants, are digested and transformed into a host of other compounds that can also become part of the blood, serum or plasma metabolome. Furthermore, the presence of some food components or food-derived chemicals can have significant downstream effects that change the metabolism, the metabolic pathways or abundance of seemingly unrelated metabolites.

There are numerous published NMR metabolomic studies that have explored these food or diet-related impacts on the blood, serum or plasma metabolome. One study described by Hefni et al. in 2018 investigated the effect of folate supplements on plasma metabolite levels by NMR spectroscopy (Hefni et al., 2018). These authors observed an increase in six different metabolites: glycine, choline, betaine, formate, histidine, and threonine, all of which are known to be affected by folate mediated one-carbon metabolism. This result suggests that folate supplementation should be monitored, or at least noted, in plasma/serum metabolomic studies. Another study conducted in 2013 by Gregory et al. (Gregory et al., 2013) explored the effect of vitamin B6 restriction on plasma samples for 23 different participants. They found the ratios of glutamine/glutamate and 2-oxoglutarate/glutamate increased. This is consistent with the role that vitamin B6 plays in transaminase activity. They also noted an increase in the plasma concentration of acetate, pyruvate (reflecting the role of vitamin B6 in glucose metabolism), and trimethylamine-N-oxide. Given that vitamin B6 deficiencies can range from 13 to 50% of the population (Ho et al., 2016; Kjeldby et al., 2013) (depending on the age of the population), these effects on the serum or plasma metabolome need to be taken seriously.

Habitual diets also influence the human serum/plasma metabolome in significant ways. Fotiou et al. in 2018 explored the effects of habitual dietary patterns on the chemical composition of serum (as well as amniotic fluid, serum and urine) in pregnant women in their second trimester (Fotiou et al., 2018). The authors found that women who consumed a less healthy diet consisting of refined cereals, yellow cheese, red meat, poultry, and ready-to-eat foods had moderately higher serum levels of glucose, alanine, tyrosine, valine, citrate, cis-aconitate, and formate compared to women who ate a healthier diet consisting of whole grain cereals, vegetables, fruits, legumes, and nuts. Whether these metabolite levels reflect the habitual diet per se, or the metabolic consequence of the habitual diet, is still to be determined.

Similar effects on the serum or plasma metabolome have also been observed with other kinds of habitual or modified habitual diets. In 2011, Moazzami et al. (Moazzami et al., 2011) studied the effect of a diet rich in whole grain rye products on plasma metabolites of prostate cancer patients. These patients were given a diet rich in whole grain (WG) rye and rye bran products (RP) or refined white wheat products (WP) for six weeks followed by a two-week washout period. At the end of the intervention period, patient plasma samples were collected and studied by 1H NMR. A modest increase in plasma levels of 3-hydroxy butyric acid, acetone, betaine, N,N-dimethylglycine, and dimethyl sulfone after RP intake was observed (Moazzami et al., 2011). Elevated levels of betaine and N,N-dimethylglycine could be attributed to the higher levels of these two compounds in WG foods. On the other hand, changes in 3-hydroxybutyric acid and acetone (ketone bodies) appear to reflect long-term, endogenous metabolic responses in the subjects that were induced by the WG diet.

Habitual consumption of meat or an omnivorous diet versus a vegetarian or vegan diet can also lead to NMR-detectable serum metabolome differences. A study by Lindqvist et al. in 2019 (Lindqvist et al., 2019) involving 40 omnivores, 37 vegetarian and 43 vegan dieters demonstrated that all three groups could be distinguished by their 1H NMR serum metabolomic profiles. Serum levels of branched-chain amino acids, creatine, creatinine, 3-hydroxyisobutyrate, lysine and 2-aminobutyrate (tentative ID) were all elevated in the meat eaters/omnivores while glutamine, glycine and trimethylamine were elevated in the vegans and vegetarians.

The Mediterranean diet (MD), because of its clear health benefits, is becoming increasingly popular (Vázquez-Fresno et al., 2015). As a result, the effects of a habitual MD on the plasma metabolome of 58 subjects were studied by Macias et al. in 2019 using 1H NMR-based metabolomics (Macias et al., 2019). Based on an established MD adherence scoring scheme, subjects were classified into two groups (“low” and “high”). This study found that those who scored high on the MD scale had moderately-elevated plasma levels of citric acid, betaine and acetic acid, but lower levels of pyruvate, mannose and myo-inositol relative to those who scored low on the MD scale (Macias et al., 2019). Citrate was found to be an excellent marker of habitual fruit intake. As with other diet-metabolome studies, certain metabolite changes could be attributed directly to food components while others appeared to arise from general shifts in the subject’s metabolism.

While habitual food intake or habitual diets can modestly change an individual’s serum or plasma metabolome, so too can acute consumption of certain foods. An acute intervention study conducted by Radjursoga et al. in 2019 (Rådjursöga et al., 2019) investigated the serum metabolic responses to two different kinds of breakfast: a ham and egg breakfast, and a cereal breakfast. The postprandial serum samples (n = 24) were subjected to 1H NMR-based metabolomics and it was found that concentrations of proline, tyrosine, and N-acetylated amino acids increased after consumption of the cereal breakfast, while concentrations of creatine, methanol and isoleucine were increased after the ham and egg breakfast (Rådjursöga et al., 2019).

A similar acute intervention study by Trimigno et al., 2018 (Trimigno et al., 2018) looked at the serum from 11 healthy individuals who consumed milk, cheese, or a soy drink. Using 1H NMR-based metabolomics, they found that levels of tyrosine, isoleucine, valine and 3-hydroxyisobutyrate were elevated in the serum of cheese consumers relative to milk and soy drink consumers (Trimigno et al., 2018). While the effects are relatively modest, these examples show that serum/plasma metabolite concentration levels can be modified by both habitual and acute food intake.

Effects of extended fasting

Periods of fasting have been, and still are, very common in human culture. Fasting has been followed by Muslims, Christians, Jews, Buddhists, and others as religious practice for centuries. For example, during the Ramadan, intermittent fasting is practiced with a daytime (12–14 h) cessation of food consumption for nearly a month (Ang et al., 2012; Townsend et al., 2016). Fasting affects energy production of the human body and will trigger catabolic and anabolic reactions. Glucose and its short-term storage form glycogen comprise the major energy sources of the body. During fasting, glycogen stores are rapidly exhausted forcing the body to activate gluconeogenesis. For fasting subjects, it was shown by Rothman et al. using 13C NMR that gluconeogenesis accounts for a substantial fraction of total blood glucose during the first 22 h of a fast (Rothman et al., 1991). Likewise, Teruya et al. showed that during fasting, various non-carbohydrate metabolites such as lipids and branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) (Teruya et al., 2019) are used as additional energy sources leading to a substantial increase in blood ketone bodies such as β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate (Nicholson et al., 1984). As a result, samples collected from fasted individuals will tend to have higher levels of ketone bodies along with lower levels of glucose, lipids and BCAAs than those samples collected from individuals who have just consumed a meal (Bermingham et al., 2023; Shrestha et al., 2017).

The preference for fasted samples for plasma or serum in clinical studies originally arose from a study conducted by Cohn et al. nearly 40 years ago (Cohn et al., 1988) which showed that the lipoprotein cholesterol concentration measured in plasma sampled from probands fed a high-fat diet differed significantly from those measured in the fasted control group. As a result, most plasma samples being analyzed for lipids, lipoproteins and apolipoproteins—whether by NMR or by other means—are usually measured in the fasting state (De Backer et al., 2003; Remaley et al., 2006). Likewise, for the analysis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic microangiopathy, it is also recommended that plasma and serum samples should be obtained after an at least 8 h fast to ensure stable fasting blood glucose levels (Lin et al., 2019). Therefore, for the analysis of metabolites, lipids and lipoproteins, it is generally recommended to collect human blood samples after an overnight fast.

Effects of age and gender

The impact of age and sex on plasma/serum composition is well established (Pinto et al., 2014). Age-related changes include alterations in the levels of amino acids that are involved in muscle mass and protein synthesis as well as metabolites associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, energy metabolism and lipid metabolism. For example, van den Akker et al. demonstrated that it is possible to use NMR-derived metabolite concentrations to predict an individual’s chronological age with a median error of 7.3 years (van den Akker et al., 2020). Specifically, they used concentrations of 52 metabolites to develop a linear model that correlated with chronological age with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.64. The metabolites that correlated negatively with chronological age included histidine, leucine, isoleucine, alanine, linoleic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, phosphatidylcholine and total choline. Conversely, the metabolites that correlated positively with chronological age included glutamine, citrate, phenylalanine, creatinine, tyrosine, lactate, valine, acetate and glucose.

In agreement with this study, Lau et al. (Lau et al., 2023) reported an age-related decrease in the concentration of the amino acids leucine and histidine (as well as the protein albumin, small HDL phospholipids, and VLDL cholesterol). The authors also observed age-related increases in levels of tyrosine, phenylalanine, glutamine, creatinine, citrate, glucose, omega-3 fatty acids, triglycerides, and the degree of unsaturation of fatty acids. In a separate NMR-based metabolomics study, Castro and co-authors (Castro et al., 2022) found that concentrations of leucine, isoleucine, asparagine, threonine, and 3-hydroxybutyrate correlate negatively, while aspartate, succinate, valine, dimethylsulfone and ornithine correlate positively with age in a statistically significant manner. In other words, a significant number of blood, serum or plasma metabolites will either decrease or increase with age. Therefore, if the confounding effects of age are unaccounted for in disease-related metabolomics studies, the variation due to age could be misinterpreted as being disease related or could hide the presence of other more subtle changes in truly meaningful biomarkers.

Similar to age differences, biological sex differences have a significant impact on metabolite concentrations measured by NMR. The sex-specific differences in metabolite levels originate from well-known differences in hormone levels, body composition, and metabolic processes between males and females. For instance, estrogen and testosterone have been shown to modulate lipid metabolism, which can be detected as variations in lipid-related metabolites in serum/plasma samples analyzed by the Nightingale or B.I. LISA NMR assays. Additionally, sex-specific differences in muscle mass and fat distribution can influence concentrations of metabolites, particularly those that are related to energy metabolism and amino acid turnover. For example, Barba et al. (Barba et al., 2019) identified and quantified 19 serum metabolites from methanol deproteinized serum samples and found that lactate, glucose, valine and glycine were notably elevated in women, compared to men. The study involved 39 healthy individuals (22 males and 17 females) aged between 55 and 70 years, who underwent stress tests and were considered negative for any sign of coronary artery disease.

A significant sex-related difference in metabolite concentrations was also found by Bell et al. in a study that looked at the sex differences in metabolites across four life stages (Bell et al., 2021). This study used data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, which involved the analysis of 7727 offsprings (49% male/51% female) and 6500 parents. This study examined over 200 serum or plasma components (metabolites, lipids, proteins and lipoproteins) quantified through targeted NMR metabolomics using the Nightingale assay. The researchers found that at age 8, males had lower levels of total lipids in VLDL compared to females. As males aged, VLDL levels increased, particularly in medium-or-larger subclasses of VLDL triglycerides. By 18 years, males had significantly higher levels of VLDL triglycerides, a trend that continued into early adulthood (25 years) and middle adulthood (50 years). While males showed increasing levels of VLDL triglycerides with age, females had generally higher levels of LDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and acetylated glycoproteins across all ages.

In agreement with this study, Ellul et al. (Ellul et al., 2020), who also used the Nightingale NMR assay, reported higher average serum levels of lipids in small and very-small VLDL particles in their study of sex differences in serum metabolites of infants (Ellul et al., 2020). The Ellul et al. study was part of the Barwon Infant Study and involved a population of 485 infants. The authors found that several serum cholesterol measures (i.e., total serum, and remnant, esterified and free cholesterol) were higher in girls. Likewise, serum docosahexaenoic acid, omega-3, omega-6, and monounsaturated fatty acids were higher in female infants. Other serum metabolites that were elevated in girls included intermediate density lipoproteins, LDL-related measures, inflammation marker acetylated glycoproteins, total serum albumin, glycerol and glycine.

A higher plasma glycine concentration in female participants was also found in the Karlsruhe Metabolomics and Nutrition (KarMeN) study conducted by Rist and colleagues (Rist et al., 2017). This cross-sectional study included 301 healthy men and women aged 18–80 years. The KarMeN study aimed to investigate how these sex- and age-related physiological conditions such as body composition and physical fitness are reflected in the metabolome and whether sex and age can be predicted based on plasma and urine metabolite profiles. This study employed several experimental techniques, including 1H NMR-based metabolomics. Overall, it was discovered that men had higher plasma concentrations of creatinine, leucine and valine, while women had higher plasma levels of creatine and glycine. Overall, these data indicate a significant number of blood, serum or plasma metabolites that are affected by sex. Therefore, if sex effects or their confounding influence are not properly accounted for in disease-related NMR metabolomic studies, one’s ability to discover important metabolite markers, pathways or trends will be compromised.

Effects of physical activity

The involvement in exercise and sports has long been known to cause substantial changes in human physiology and in the human metabolism (Jaguri et al., 2023). Exercise typically brings about an immediate metabolic response that influences the rate of synthesis or generation of many different metabolites that are linked to aerobic and anaerobic glucose metabolism, lipid and amino acid metabolism, muscle damage and liver function (Coelho et al., 2016).

1H NMR metabolomics studies, such as those by Brugnara et al. (Brugnara et al., 2012), have shown that immediately after an intense workout, an increase in serum tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates (succinate, citrate, and glycerol) and products of anaerobic glycolysis (lactate and pyruvate) are often observed, reflecting the increased energy demands during exercise (Brugnara et al., 2012). Gluconeogenic precursors, which includes alanine and lactate, also increased in serum post-workout (Brugnara et al., 2012). 1H NMR metabolomics studies have also shown that after exercise of longer durations, such as running long distances (i.e., a marathon), several additional changes in energy metabolism occur as the body responds to this massive energy demand. Bester et al. (Bester et al., 2021) showed that for serum lactate and pyruvate, post-marathon levels doubled compared to pre-marathon levels, suggesting increased anaerobic glycolysis. Serum amino acid levels (lysine, proline, leucine, isoleucine, valine) decreased post-marathon suggesting that amino acids were catabolized for energy generation. An increase in ketone bodies (3-hydroxybutyric acid, acetone, acetoacetic acid) was also seen in post-marathon serum which is strongly indicative of upregulated lipid catabolism. Increased serum creatine and creatinine were also observed, suggesting that muscle damage may be occurring (Bester et al., 2021). Similar changes in serum TCA and anaerobic glycolysis metabolites were also seen by Pechlivanis et al., who studied effects of sprint interval training, suggesting that these are global changes seen with exercise (Pechlivanis et al., 2012).

Additional changes to the serum/plasma metabolome have been detected via NMR-based metabolomics over the long term with regular exercise. Overall, changes of metabolites related to protein and fatty acid metabolic pathways are typically observed (Castro et al., 2023; Pechlivanis et al., 2012; Sardeli et al., 2022). These studies found that serum lipid levels are decreased, while other changes to serum metabolites related to fatty acid metabolism, such as 3-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate, are also observed. With moderate and high-level inspiratory muscle training, Castro et al. (Castro et al., 2023) observed higher serum levels of proline and methionine, suggesting upregulation of amino acid metabolism. The above 1H NMR study, focussed on sprint interval training by Pechlivanis et al. (Pechlivanis et al., 2012), also detected a decrease in serum glycoprotein acetylation, which has been previously identified as a biomarker for inflammation and cardiovascular disease (Otvos et al., 2015). Pechlivanis et al. also noted increased serum methylguanidine with increased training (Pechlivanis et al., 2012). Methylguanidine, derived from protein catabolism, has been reported as a biomarker of oxidative stress (Ienaga et al., 2007) and exhibits anti-inflammatory activity (Marzocco et al., 2004). Collectively, these results point to the need to be aware of the effects of both acute and long-term exercise on serum/plasma metabolomes and that mitigation of exercise effects or providing guidance about when blood should be collected after exercise is important in the design of 1H NMR metabolomics studies.

Effects of obesity

Several studies have reported a significant association of body-mass index (BMI) and obesity measures, such as waist–hip ratio (WHR) and android/gynoid fat ratio (AGR) with changes in serum metabolites. For example, in a 2019 paper, Wulaningsih and colleagues used 1H NMR and the Nightingale assay to investigate the relationship between adiposity measures (from childhood through adulthood), BMI and serum metabolites for 900 British individuals (Wulaningsih et al., 2019). They quantified 233 serum metabolites, lipids, and lipoproteins and found significant associations between BMI, WHR, AGR, and numerous serum metabolite concentrations and features. Specifically, 168, 126, and 133 compounds were associated with BMI, WHR, and AGR at age 60–64, respectively. The study found strong associations for HDL, particularly HDL particle size, with a notable decrease in HDL diameter with each unit increase in BMI. The study also identified inverse associations between BMI at age 7 and levels of glucose and glycoprotein at age 60–64, suggesting early-life BMI influences on metabolic profiles in later life.

In a similar study, Saner et al. (Saner et al., 2019) applied the Nightingale NMR assay to investigate the associations between adiposity measures and serum metabolomic profiles in youth with obesity. This study utilized the Childhood Overweight BioRepository of Australia (COBRA) cohort and looked at 214 participants. Positive associations were found between BMI z-score and serum phenylalanine and tyrosine levels, as well as in medium HDL levels. Negative associations with BMI were detected with the ratio of serum docosahexaenoic acid/total fatty acids and histidine.

Discovering the association between metabolite concentrations and BMI as well as modifiable life factors (smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, diet, etc.) was also the subject of a study by Hamaya et al. (Hamaya et al., 2022). These authors focused on measuring plasma BCAAs (isoleucine, leucine, and valine) by 1H NMR (using the LipoScience/LabCorp assay) because of their known association with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes. The study included a cross-sectional analysis among 18,897 women from the Women's Health Study to identify modifiable lifestyle factors that influence BCAA concentrations. BMI was found to be significantly associated with BCAA levels. Compared to women with a BMI of less than 25.0, plasma BCAAs were 8.6%, 15.3%, and 21.0% higher for women with a BMI of 25.0–29.9, 30.0–39.9, and ≥ 40.0, respectively. Diet, physical activity, and other lifestyle factors had a smaller impact.

This connection between BMI and serum BCAA concentrations appears to be in agreement with the results of the Shanghai Changfeng Study, published in 2021 by Wu et al. (Wu et al., 2021). This study, which looked at 1078 individuals, was aimed at identifying serum metabolites that could indicate future development of metabolic disorders in individuals who are initially metabolically healthy. Participants were categorized based on their BMI and metabolic health into metabolically-healthy overweight/obese and metabolically-healthy normal weight groups. Their serum metabolic profiles were analyzed using 1H NMR spectroscopy via the B.I. LISA assay (which detected 112 lipids and lipoproteins) and the B.I.Quant-PS system (which detected 38 small-molecule metabolites). This study found that, after a follow-up of 4 years, a higher proportion of healthy overweight participants transitioned to a metabolically unhealthy status compared to normal-weight healthy participants. It was also found that healthy overweight individuals had higher concentrations of BCAAs, alanine and tyrosine as well as lower concentrations of HDL components and glycine when compared with normal-weight individuals. Overall, it is clear that obesity or higher BMI has a significant influence on NMR measurable metabolites. Therefore, if obesity or BMI-related metabolite effects are not included in NMR-based metabolomic studies, one’s ability to discover important metabolite markers, pathways or trends may be compromised.

Effects of smoking

While smoking or smoke-exposure compounds such as cotinine are detectable in certain biofluids via GC–MS and LC–MS studies (Lehtovirta et al., 2023; Thomas et al., 2020), no smoking or smoke-derived compounds have yet been detected by NMR of serum or plasma. However, because smoking (like obesity) can lead to negative, long-term health effects, the effects of smoking are typically detected through secondary effects on metabolism or general health. One study by Lehtovirta et al. used the Nightingale NMR assay on serum to assess the “smoker’s metabolome” (Lehtovirta et al., 2023). This study found that serum lipid levels, particularly unsaturated fatty acids, triglycerides, and VLDL particle concentrations and size were increased in smokers. Interestingly, these biomarkers are also associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Another NMR study by Bernini et al. (Patrizia Bernini et al., 2011a, 2011b) found that changes to metabolites related to fatty acid metabolism (such as 3-hydroxybutyrate, α-ketoglutarate, threonine, and dimethylglycine) can be correlated with blood lipid levels. Other NMR studies appear to show weaker correlations between the serum metabolome and smoking. However, effects were detected including reduced serum amino acid concentrations (Labaki et al., 2019), increased serum tryptophan levels (Aguilar et al., 2021), decreased BAAAs in plasma (Hamaya et al., 2022; Jang et al., 2022), and decreased levels of plasma citrate and glycerol (Jang et al., 2022). Collectively, these data indicate that smoking does influence the NMR measurable serum/plasma metabolome and that these confounding effects should be modeled into any cohort measured via NMR-based metabolomics.

Effects of alcohol

Alcohol consumption has a strong and multifaceted effect on NMR-detectable metabolites in serum and plasma. These effects depend on the subject’s age, sex, genetics, physiology and the amount of consumed alcohol. A large study by Würtz et al. (Würtz et al., 2016) applied an early version of the Nightingale NMR assay to investigate the associations between alcohol intake and 86 serum metabolites, lipids and lipoproteins in a cross-sectional study from three population-based cohorts from Finland. In addition, these authors also examined the serum metabolic changes associated with changes in alcohol intake in 1,466 individuals during a 6-year follow-up. This study found that increased alcohol intake was associated with higher serum HDL levels and smaller LDL particle size, increased monounsaturated fatty acids, decreased omega-6 fatty acids, and lower serum concentrations of glutamine and citrate. Many serum metabolic biomarkers were found to have U-shaped associations with alcohol consumption, indicating differential effects depending on the quantity of alcohol intake.

The U-shaped dependence on alcohol consumption was also detected for several other serum metabolites (e.g., lipoprotein lipids in VLDL subclasses, VLDL triglycerides) using the more extensive Nightingale-based NMR assay as reported by Du and co-authors (Du et al., 2020). Alcohol intake was significantly associated with changes in 23 out of 37 lipids, 12 out of 16 fatty acids, and six out of 20 low-molecular-weight metabolites, independent of confounding factors. These effects were similar for total alcohol consumption and different types of alcohol (beer, wine, and spirits). Many metabolites, including those in several HDL subclasses, HDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein A-1, phosphotriglycerides, total fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, and omega-3 fatty acids, had positive correlations with alcohol intake. Conversely, LDL particle size, omega-6 fatty acids ratio to total fatty acids, and citrate had negative linear associations with alcohol consumption. The findings indicate that alcohol intake can be a significant confounding variable that should be taken into consideration in NMR metabolomics studies.

Effects of gut microbiota

The gut microbiome (GM) is a complex ecosystem that comprises bacteria, protozoa, archaea, viruses, and fungi, which symbiotically interact with each other and their human host and the food that their host consumes. The gut microbiome plays important physiological roles, participating in digestion, immunomodulation, cardiovascular health, gut health, and a number of different pathological disorders (Amedei & Morbidelli, 2019).

The metabolites generated by gut microbes can easily pass into the circulatory system, including amino acids, lipids, sugars, biogenic amines, organic acids, peptides, glycolipids, oligosaccharides, terpenoids or secondary bile products, and volatile small molecules. These compounds can influence both the health and the metabolic state of the host (Amedei & Morbidelli, 2019). Gut microbes can chemically cleave dietary compounds containing tertiary amines such as choline, phosphatidylcholine, glycerophosphocholine, carnitine and betaine leading to the release of trimethylamine (TMA). These can be further oxidized by liver flavin monooxygenase (FMO) to produce trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) (Fan et al., 2015; Koeth et al., 2013). TMAO is a known uremic toxin and has been implicated in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Short-chain fatty acids or SCFAs (such as acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, and the less abundant, valeric acid and caproic acid) are synthesized by bacteria from the glycolysis of glucose to pyruvate, to acetyl-CoA, and finally to the SCFAs acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid (Miller & Wolin, 1996). Unlike TMAO, SCFAs are widely recognized to have beneficial effects (Abdul Rahim et al., 2019).

The diversity and composition of the gut microbiome can influence the metabolites found in serum. An NMR study by Org et al. (Org et al., 2017) found associations between gut microbes and the fasting serum levels of several metabolites, including fatty acids, amino acids, lipids, and glucose (Org et al., 2017). They found a strong association of microbial diversity with serum levels of, glutamine, glycated haemoglobin and acetate levels. Partula et al. (Partula et al., 2021) found that higher gut microbial diversity was correlated with higher concentrations of amino acids, glucose, and citrate, and with lower concentrations of metabolites involved in fatty acid metabolism.

Bacterial infections in the gastrointestinal tract can also influence the serum metabolome. Using 1H NMR, Fang et al. (Fang et al., 2020) found that serum TMAO and lactate levels were affected by Helicobacter pylori infection in the stomach, and that these compounds could be potential biomarkers for monitoring the course of antibiotic treatment. Kato et al. (Kato et al., 2018) used 1H NMR to investigate the effects of oral administration of Porphyromonas gingivalis on the gut microbiome and serum metabolome in mice. While the mechanism by which P. gingivalis alters the gut microbiome is not clear, these authors found that the gut microbiome composition was altered and serum amino acids, notably the aromatic amino acids, were also increased.

Interventions targeting the gastrointestinal tract or altering the gut microbiome can affect the serum metabolome. Gralka et al. (Gralka et al., 2015) used 1H NMR to explore the effects of bariatric surgery on the serum metabolome. They found that obese subjects, prior to surgery, had higher levels of methanol and isopropanol and that these levels dropped to healthy, normal levels after bariatric surgery. The fact that methanol and isopropanol are gut-derived metabolites suggests that bariatric surgery induced changes in their gut microbiota. Ghini et al. (2020) used 1H NMR to measure the effect of probiotics on gut microbiota and serum metabolome. They found that serum pyruvate, phenylalanine and proline levels were increased over the course of probiotic treatment in healthy subjects. Overall, these data clearly show that individual differences in gut microbiota as well as interventions, such as surgical procedures or dietary modifications that alter the gut microbiota, can significantly affect the serum or plasma metabolome. In this regard, the gut microbiome must be considered as a potential confounding factor in the interpretation of NMR-based metabolomic studies.

Effects of health status

An individual’s health status can significantly influence their NMR-detectable serum, plasma or whole blood metabolome. These health-status effects can be broadly distinguished according to whether the condition is acute or chronic. Acute diseases, such as viral infections, including influenza (Banoei et al., 2017), and SARS-CoV-2 (Bruzzone et al., 2020, 2023), sepsis (Mickiewicz et al., 2018) as well as acute lung diseases (Dasgupta et al., 2023) have been shown to cause broad alterations in the composition of NMR-detectable blood, serum and plasma metabolomes. Similar metabolome-wide effects have been shown for acute organ injuries, including acute damage to the liver (Amathieu et al., 2016) and kidney (Zacharias et al., 2015). Numerous chronic diseases have likewise been associated with significant changes in the NMR-detectable blood, serum and plasma metabolomes, including cardiovascular diseases (Ussher et al., 2016), diabetes (Roberts et al., 2014), chronic kidney disease (Schultheiss et al., 2021), chronic liver diseases (Amathieu et al., 2016), chronic lung diseases (Moitra et al., 2023), chronic gastrointestinal disorders (Bjerrum et al., 2021; Y. Zhang et al., 2013), neurodegeneration (Zacharias et al., 2022), chronic viral infections, e.g. HIV (Sitole et al., 2013), gout (Li et al., 2023), psychiatric disorders (Pedrini et al., 2019), various cancers (Nannini et al., 2020; Vignoli et al., 2021), and even hereditary metabolic diseases, e.g., phenylketonuria (Cannet et al., 2020). These findings have also been reaffirmed with large-scale epidemiological association studies using NMR-derived metabolomics data from the UK Biobank for many common diseases (Buergel et al., 2022; Julkunen et al., 2023). A detailed accounting of the individual serum/plasma metabolite changes associated with these many health conditions is beyond the scope of this review, but suffice to say, these NMR-detectable metabolite changes are often highly significant and their confounding effects cannot be ignored.

Given the large influence of health status on the blood, serum and plasma metabolomes (A.-H. M. Emwas et al., 2013), researchers should try to carefully assess the individual health states of their study population (and, if applicable, their healthy control population) by appropriate medical exams, patient/treating physician questionnaires, and/or information retrieval from medical records. Further recommendations for mitigating the confounding effects of health status on serum/plasma/blood metabolomics studies are provided in the Recommendations Section (Sect. 8).

Effects of drug intake

Besides the individual’s health status, the intake of drugs can significantly influence a patient’s blood metabolome. NMR-based metabolomics is able to accurately detect and quantify both small molecule drugs, e.g., paracetamol or D-mannitol, as well as downstream drug metabolites, such as propofol-glucuronide (J W Kim et al., 2013; Zacharias et al., 2015). The reflection of a patient’s medication intake in the NMR metabolic fingerprint of his/her blood specimen can have serious consequences for subsequent analyses, as large drug NMR signals—for example the large multiplets of D-mannitol administered during surgery—might obscure signals of small molecules of interest (Pertinhez et al., 2014) and/or drugs and their metabolites might act as confounders, inducing, e.g., spurious differences between patients and healthy controls, which only reflect the fact that the patients received a specific medication, while the healthy controls did not. Moreover, drugs themselves can have drastic effects on the endogenous metabolism of a patient, thereby potentially obscuring metabolic effects of diseases, which are oppressed by the drug treatment, or inducing metabolic differences between patients and healthy controls, which do not reflect the pathomechanisms of disease, but of the treatment itself (Preuss & Burris, 1996).

On the other hand, drugs and drug metabolites reflected in NMR metabolic fingerprints can also be used to study pharmacokinetics, drug metabolism, drug response as well as toxicity and their relation to the patient’s disease status (A-H Emwas et al., 2021). Zacharias et al., for example, utilized increased levels of propofol metabolites as well as the antifibrinolytic agent tranexamic acid in plasma NMR spectra to diagnose acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, potentially reflecting both prolonged drug administration and delayed excretion in patients with renal impairment (Zacharias et al., 2015). Likewise, drug effects on the endogenous metabolome can be studied by NMR-based metabolomics, providing insights into, e.g., hepatotoxicity induced in humans by acetaminophen (J W Kim et al., 2013).

In conclusion, each metabolomics study of blood, plasma, and/or serum should carefully consider potential drug effects directly being reflected in the NMR spectra as well as indirectly by influencing the endogenous metabolome. Therefore, we recommend, analogously to assessing the health states of investigated patients, to also assess the drug intake, including individual timing and dosage, of the patients under study by employing appropriate patient/treating physician questionnaires, and/or information retrieval from medical records. We would like to point out that patients undergoing anesthesia are particularly exposed to high-dosage drug administration, and researchers should, in this setting, be especially aware of NMR signals arising from drugs or metabolites thereof in the investigated metabolic fingerprints.

Summary of participant-specific factors

It should be clear from the NMR-based metabolomic studies that the whole blood, serum and plasma metabolomes are affected significantly by diet, fasting status, sex, age, exercise, obesity or weight, smoking, alcohol consumption, gut microbiota, health status, and drug administration. The magnitude of these effects varies considerably, and in unfortunate cases, may lead to a significant misinterpretation of a typical metabolomics study. Their influence or the added metabolic “noise” from these effects can lead to a loss of signal or the diminishment of potentially interesting findings. Whereas most of these confounders can be controlled and adjusted through suitable patient selection, well-defined sample collection protocols, careful tracking or the use of questionnaires, it is important to remember that some confounders (such as the microbiome) cannot be as easily controlled. Being aware that these confounders exist and being knowledgeable about their likely contributions to a given study can certainly help improve the quality and the robustness of the findings of any NMR-based metabolomic study of serum, plasma or whole blood.

Effects of sample processing time

In addition to the participant- or patient-specific confounding factors discussed in the previous section, another critical variable is the blood sample processing time, i.e., the amount of time it takes to prepare plasma or serum from blood. Blood is a “living” biofluid containing cells and enzymes that carry out a range of chemical functions, including glycolysis, oxidation, transamination, hydroxylation and others. Therefore, the time between blood collection and the processing of the blood samples (involving removing the cellular components for plasma and removing cells and clotting components in the case of serum) is important because it directly affects measured metabolite concentrations. Extended delays before and during processing can alter the final concentrations of several “time-sensitive” metabolites measured by 1H NMR spectroscopy. A thorough study of this phenomena was performed by Bernini et al. (P Bernini et al., 2011a, 2011b). This study found that delays in processing blood caused a significant decrease in glucose concentration and an increase in lactate concentration, likely due to glycolysis in erythrocytes. These glucose and lactate changes were also observed in another study that also noted relatively small changes in lipid components’ levels with delays in sample processing (Debik et al., 2022a, 2022b). Changes in pyruvate concentration, an intermediate metabolite of glycolysis, depended on the type of blood derivative (serum or plasma) and on temperature. Specifically, the pyruvate concentration slightly decreased in plasma at 4 °C and increased at 25 °C, while in serum, it decreased at 4 °C and was almost constant at 25 °C. After blood processing, concentrations of glucose, lactate, and pyruvate remained stable over time. However, the presence of oxygen led to changes in several other metabolites and proteins, including albumin, triglycerides, LDL/VLDL, proline, citrate, and histidine. Histidine signals showed a shift consistent with a pH variation increase of about 0.1 pH units.

Debik et al. (Debik et al., 2022a, 2022b) proposed that the lactate/glucose ratio can be used as a measure for compliance with the sample collection protocols, specifically, the expected time between blood collection and blood centrifugation (to obtain either plasma or serum). However, as detailed above it should be noted that both glucose and lactate may be affected by numerous other factors. Debik et al. also found that several NMR-measured metabolites other than lactate, glucose and pyruvate can be affected by delays in sample processing. Specifically, an 8-h delay resulted in 147% increase in ornithine levels in plasma, along with 15.0 and 52.5% increases in phenylalanine concentrations in plasma and serum, respectively. Likewise, a 10.4 and 13.7% increase was seen in alanine levels in plasma and serum, respectively, and a 32.9% increase was seen in glycine concentration in serum (Debik et al., 2022a, 2022b).

Bervoets et al. (Bervoets et al., 2015) found that the impact of sample processing delays can be minimized if blood is stored at 4 °C before centrifugation. Specifically, they found that changes in the concentrations of lactate, glucose and pyruvate after storing blood at 4 °C for 8 h are significantly reduced and much smaller than the inter-individual variation in the study (Bervoets et al., 2015).