Abstract

Although EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) are effective for EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), resistance inevitably develops through diverse mechanisms, including secondary genetic mutations, amplifications and as-yet undefined processes. To comprehensively unravel the mechanisms of EGFR-TKI resistance, we establish a biobank of patient-derived EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoids, encompassing cases previously treated with EGFR-TKIs. Through comprehensive molecular profiling including single-cell analysis, here we identify a subgroup of EGFR-TKI-resistant LUAD organoids that lacks known resistance-related genetic lesions and instead exhibits a basal-shift phenotype characterized by the hybrid expression of LUAD- and squamous cell carcinoma-related genes. Prospective gene engineering demonstrates that NKX2-1 knockout induces the basal-shift transformation along with EGFR-target therapy resistance. Basal-shift LUADs frequently harbor CDKN2A/B loss and are sensitive to CDK4/6 inhibitors. Our EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoid library not only offers a valuable resource for lung cancer research but also provides insights into molecular underpinnings of EGFR-TKI resistance, facilitating the development of therapeutic strategies.

Subject terms: Cancer models, Non-small-cell lung cancer, Cancer genomics, Growth factor signalling

Resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) is prevalent. Here the authors establish a biobank of patient-derived EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoids and identify a subgroup of EGFR-TKI-resistant lung adenocarcinoma organoids, which exhibit a basal-shift phenotype and vulnerability to CDK4/6 inhibitors.

Introduction

The prevalence of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation in human lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) underscores the fundamental role of the EGFR signaling pathway in cancer growth. Consequently, targeting mutant EGFR with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) has shown promise as a treatment strategy1–6. Despite initial response, resistance to 1st and 2nd generation EGFR-TKIs (Gefitinib, Erlotinib, and Afatinib) inevitably develops, primarily due to the emergence of secondary EGFR mutations, most notably T790M mutation in the ATP-binding pocket7. The third-generation EGFR-TKI Osimertinib overcomes this limitation and is now recommended as the forefront therapeutic agent for EGFR-mutant LUAD6,8,9. Nevertheless, the majority of patients experience tumor relapse or recurrence within 1-2 years, highlighting the need to investigate mechanisms underlying EGFR-TKI resistance10–12.

The increasing prevalence of EGFR-TKI resistance in EGFR-mutant LUADs has spurred extensive research to unravel its molecular mechanisms13–17. Genomics studies in LUAD have identified various genetic lesions associated with EGFR-TKI resistance, including secondary and tertiary EGFR mutations18–21, as well as alterations in EGFR downstream signaling involving PIK3CA, BRAF and CCND genes22,23. Recent studies have also linked EGFR-TKI resistance to alterations in non-EGFR receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), such as those in MET15, ERBB213, IGF1R24, AXL25, RET, ALK, FGFR3, and NTRK13,26. However, in nearly half of the EGFR-TKI-resistant tumors, whole-genome level sequencing has failed to detect genetic lesions directly associated with drug resistance. The presence of histological transformation to small cell lung cancer (SCLC)13,14,27 or squamous cell carcinoma (SQ)28,29 accounts for non-genetic EGFR-TKI resistance, indicating that epigenetic mechanisms may play a role30–32. However, the absence of SCLC- and SQ- transformation in most cases prompts further investigation into molecular mechanisms that confer EGFR-TKI resistance. As non-genetic lesions are challenging to capture by genomic sequencing, biological platforms that faithfully phenocopy EGFR-TKI response in a clinical context are required to investigate non-genetic determinants of EGFR-TKI resistance.

Organoid technology has enabled the establishment and molecular characterization of LUAD organoids derived from clinical specimens33–39. Previous studies have shown that patient-derived LUAD organoids largely represent genomics-defined sensitivity to targeted therapy. While these organoids have contributed to our understanding of LUAD genetic drivers and their role in drug sensitivity in therapy-naïve tumors, limited accessibility to post-therapy tumors and few opportunities to sample them in a timely manner have hindered the derivation and characterization of therapy-exposed LUAD organoids.

In this work, to overcome these limitations, we here establish a living biobank comprising 39 lines of EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoids, including post-therapy organoids with EGFR-TKI resistance. Organoid transcriptomes illuminate a subgroup in EGFR-TKI-resistant organoids, characterized by bi-potency with partial LUAD and SQ traits, which we refer to as basal-shift LUAD, and an enrichment of CDKN2A/B loss. CRISPR-knockout of NKX2-1, a regulator of the alveolar identity, confers EGFR-TKI resistance on LUAD and human alveolar organoids through alteration of the cell-autonomous niche dependency. We further demonstrate CDK4/6 inhibition as a potential strategy to treat basal-shift LUAD with CDKN2A/B loss. Our findings not only shed light on mechanisms of EGFR-TKI resistance but also emphasize the translational potential of phenotype-driven approaches using patient-derived organoids to identify synthetic vulnerabilities in drug-resistant tumors and to develop targeted therapies.

Results

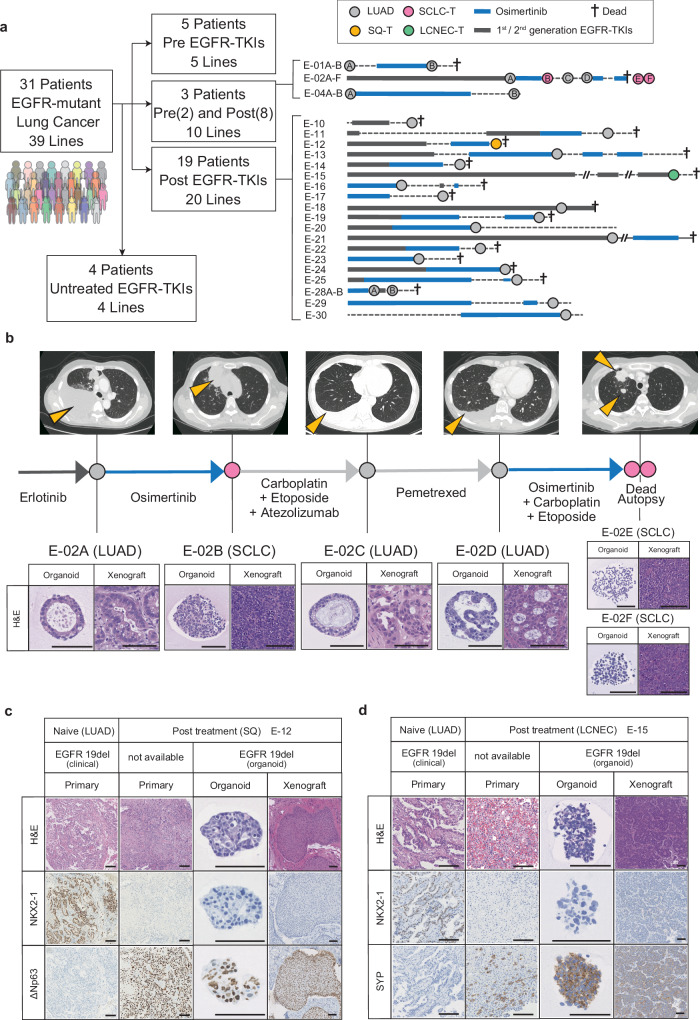

Establishment of a patient-derived EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoid library

To create a biological platform that represents clinical resistance to EGFR-TKIs in lung cancer and encompasses diverse mechanisms of resistance, we established 39 lung cancer organoid lines derived from 31 patients known to have EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Clinical specimens were obtained through various approaches, including surgical resection, pleural effusion drainage, bronchoscopy, CT-guided biopsy, ascites puncture, cerebral spinal fluid puncture and postmortem autopsy (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Detailed clinical information for each patient is available in Supplementary Data 1. All organoid lines underwent a stable propagation for over six months. Among these patients, 28 had received EGFR-TKI therapy, including Osimertinib or other EGFR-TKIs. Three patients provided longitudinal samples collected before and after EGFR-TKI treatment, allowing us to establish two (E-01A and E-01B), six (E-02A–F) and two (E-04A and E-04B) serial lines from the same patients (Fig. 1a, b). LUAD-derived organoids and xenograft tumors exhibited characteristic LUAD-like morphology with NKX2-1 (TTF-1) expression (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Notably, five of the organoid lines derived from EGFR-TKI-treated tumors underwent histological transformation, presenting as SQ, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC), or SCLC (Fig. 1b–d, Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). In these transformed cases, the histopathological traits were conserved in organoids, xenografts and original tumors. Specifically, SQ-transformed (SQ-T) organoids and their xenografts exhibited a loss of glandular structures, nests of polygonal cells and expression of the squamous cell marker ΔNp63 (p40), while LCNEC- or SCLC-transformed (SCLC-T) organoids expressed neuroendocrine markers. Such histological diversity and detailed clinical annotation of our EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoid library (ELCOL) highlight its value as a unique resource for investigating strategies to target lung cancer with EGFR-TKI resistance.

Fig. 1. Establishment of an EGFR-mutant Lung Cancer Organoid Library (ELCOL).

a Summary of ELCOL. Treatment course for patients with clinical resistance to EGFR-TKI is shown on the right. Circle indicates the timing of tissue sampling and organoid derivation and is colored according to the histology. Thick line shows the treatment period. LUAD; lung adenocarcinoma, SQ-T; squamous transformation, SCLC-T; small cell lung cancer transformation, LCNEC-T; large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma transformation. 1st/2nd generation EGFR-TKIs include Gefitinib, Erlotinib, Afatinib and Dacomitinib. b Example of longitudinal organoid establishment from a patient with LUAD and SCLC-T (E-02). The computed tomography image at each sampling timepoint is shown on the top, and yellow arrowheads indicate lung cancer lesions. Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the organoids and xenografted tumors (bottom). Scale bar: 100 μm. c Representative H&E staining and NKX2-1 and ΔNp63 immunostaining of the primary tumors, organoids and xenografted tumors of the E-12 line with SQ-T. Scale bar: 100 μm. d Representative H&E staining and NKX2-1 and SYP immunostaining of the primary tumors, organoids and xenografted tumors of the E-15 line with LCNEC-T. Scale bar: 100 μm.

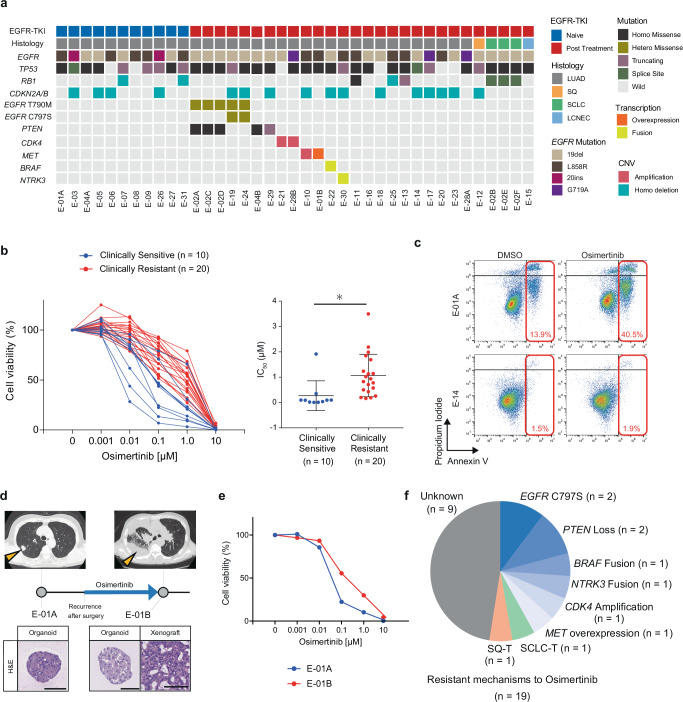

Genotype-phenotype associations in EGFR-TKI resistance

To investigate the associations between genetic alterations and sensitivity to EGFR-TKI, we conducted whole exome sequencing (WES) of lung cancer organoids. WES analysis validated the presence of EGFR mutation in all organoid lines and their correspondence with the mutation in the parental tumor specimens (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Data 1). SCLC-T organoids also shared the identical EGFR mutation with the adenocarcinoma counterparts, supporting their common origin. Post-treatment specimens exclusively carried EGFRT790M and EGFRC797S mutations, which are associated with resistance to 1st/2nd and 3rd generation EGFR-TKIs7,20,21,27, respectively, consistent with the clinical resistance. RB1 mutation was more prevalent in ELCOL (7 out of 36 lines) than in the TCGA cohort40. In agreement with the role of RB1 mutation as a driver of SCLC41, three RB1-mutant lines were derived from SCLC-T cases. Interestingly, one RB1-mutant line was established from a patient with treatment-naïve LUAD (E-07), who later experienced relapse with SCLC transformation after EGFR-TKI treatment. This line showed increased expression of ASCL1, a neuroendocrine differentiation transcription factor42 (Supplementary Fig. 2a), suggesting that RB1 mutation in LUAD may predispose to SCLC transformation prior to EGFR-TKI treatment. WES analysis also identified other minor gene alterations associated with EGFR-TKI resistance, such as MET amplification, BRAF fusion, and CDK4 amplification. 16 lines in ELCOL exhibited a loss of CDKN2A/B, regardless of EGFR-TKI treatment (Fig. 2a). WES-based copy number analysis revealed recurrent gain of the 7p chromosome region spanning the EGFR gene locus (Supplementary Fig. 2b). These findings demonstrate that ELCOL covers diverse genetic variations associated with EGFR-TKI resistance.

Fig. 2. Genetic determinants of EGFR-TKI resistance in lung cancer organoids.

a Summary of genetic alterations identified in ELCOL (n = 39 organoid lines). Genes known to be associated with sensitivity to EGFR-TKI are selected. EGFR T790M and C797S mutations that confer resistance to 1st/2nd generation EGFR-TKI and Osimertinib, respectively, are shown independently. b Sensitivity of lung cancer organoids to Osimertinib. The organoids were grouped according to the response of the original tumor to Osimertinib. Cell viability is shown as the ratio of ATP abundance between treated and untreated samples in quadruplicate. Clinically sensitive or resistant lines derive from a tumor judged to be PR/CR or PD, respectively, in RECIST. The IC50 value of each organoid line is shown on the right. Each dot shows one line. *p = 0.0123, t-test (two-sided). Data are shown as mean ± S.D. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. c Apoptosis analysis of E-01A (Osimertinib sensitive) and E-14 organoids (Osimertinib resistant) treated with DMSO or Osimertinib (1 μM, 72 hours) using flow cytometry. The number (%) indicates the proportion of Annexin V-positive cells. d Organoid derivation from the E-01 patient before and after the development of Osimertinib resistance. Yellow arrowheads show the sampled tumors. Scale bar: 100 μm. e Osimertinib sensitivity in pre- (E-01A) and post- (E-01B) Osimertinib lines. 0.1 μM ****p = 1.85 × 10−6, 1 μM ****p = 3.12 × 10−5, t-test (two-sided). Data are shown as mean ±S.D. The experiment was performed with four technical replicates. f The proportion of organoid lines with genetically defined mechanisms of Osimertinib resistance and histological transformation in Osimertinib-treated lines (n = 19). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The established organoids were next subjected to Osimertinib treatment (Fig. 2b). Comparison of the IC50 values with the clinical responses based on the RECIST criteria revealed higher resistance to Osimertinib in organoids derived from clinically resistant tumors (SD/PD after EGFR-TKI treatment) than in organoids derived from tumors with a clinical response (CR/PR) (Fig. 2b). Osimertinib treatment induced apoptosis in Osimertinib-sensitive E-01A organoids but not in resistant E-14 organoids (Fig. 2c). As a case in point, the E-01B line derived from an Osimertinib-exposed tumor showed a higher resistance to Osimertinib than its treatment-naïve counterpart, E-01A (Fig. 2d, e). Around two-thirds of the EGFR mutant lines derived from EGFR-TKI-treated tumors lacked additional genetic lesions known to be associated with EGFR-TKI resistance, consistent with previous studies (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 2c)12. These EGFR-TKI-resistant lines without second hits genetic lesions included organoids that had undergone histological transformation to SCLC, LCNEC or SQ. Nevertheless, the mechanism of EGFR-TKI resistance in a half of the cases remained unclear. These results highlight the potential of patient-derived lung cancer organoids in drug sensitivity testing, as well as the limitation of predicting clinical response to EGFR-TKI based solely on genomics.

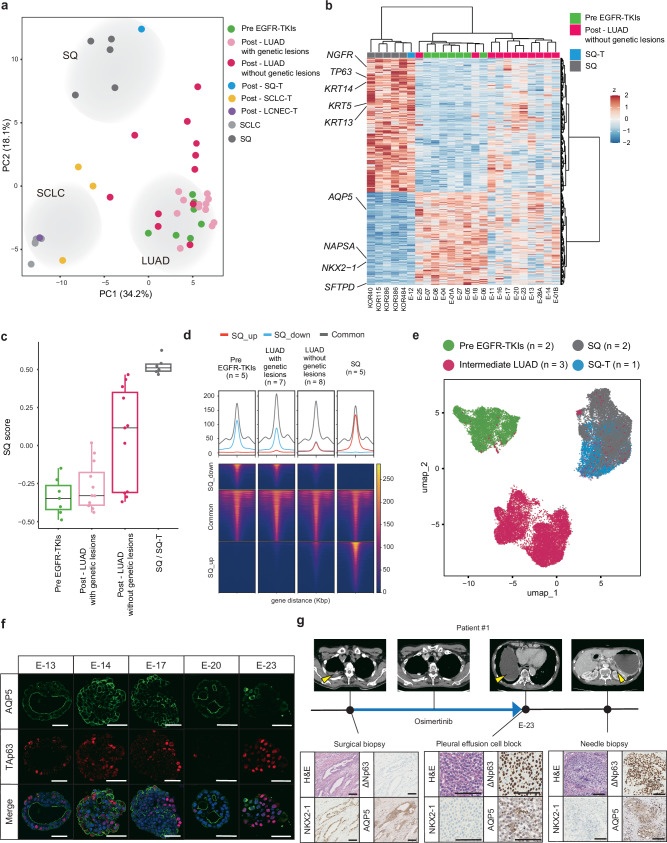

Transcriptome analysis reveals a basal-like subtype in EGFR-TKI-resistant lung cancer

To investigate non-genetic mechanisms that mediate Osimertinib resistance, we analyzed the transcriptome of ELCOL organoids (n = 35) and our previously reported lung cancer organoids, including SQ (n = 5), and SCLC (n = 5) organoid lines38. Principal component analysis (PCA) depicted distinct gene expression patterns among LUAD, SCLC, and SQ organoids (Fig. 3a). The transcriptome of SCLC-T and SQ-T organoids resembled those of primary SCLC and SQ organoids, respectively. Some LUAD organoids were intervened between treatment-naïve LUAD and SQ organoids in the PCA plot, suggestive of an intermediate gene signature (Fig. 3a). Notably, all SQ/LUAD intermediates were EGFR-TKI-resistant lines lacking resistance-associated genetic alterations. The presence of this unique intermediate population prompted us to explore gene programs associated with EGFR-TKI resistance. Comparative transcriptome analysis uncovered a partial upregulation of SQ markers such as KRT5, KRT14, NGFR and TP63 in intermediate organoids compared to pre-EGFR-TKIs LUAD organoids (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Gene ontology terms associated with squamous cell, such as the epidermis and skin, were enriched in the upregulated genes (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Unlike SQ-T organoids, the intermediate population retained the expression of alveolar marker genes to some degree (Fig. 3b). Gene set enrichment analysis using genes upregulated in SQ organoids vs pre-EGFR-TKIs LUAD organoids validated an increased enrichment of SQ genes in intermediate LUAD organoids compared to pre-EGFR-TKIs LUAD organoids (Fig. 3c). Assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) further revealed the de-repression of SQ-specific ATAC peaks in intermediate LUAD organoids (Fig. 3d). These data demonstrated that EGFR-TKI-resistant LUAD organoids without known genetic lesions partially acquired SQ-like properties while retaining LUAD traits through transcriptomic and epigenome remodeling.

Fig. 3. Basal-shift transformation in EGFR-TKI resistant LUAD organoids.

a Principal component analysis of EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoid transcriptomes. The transcriptomes of primary SQ (n = 5) and SCLC lines (n = 5) were included for reference. b Genes differentially expressed between primary SQ (n = 5), SQ-T (n = 1), pre-EGFR-TKIs LUAD (n = 7) and post-EGFR-TKIs LUAD without genetic lesions (n = 11) (FDR < 5.0 ×10−5 in DESeq2). Expressions in post-EGFR-TKIs LUAD lines without known genetic lesions are also shown. SQ and LUAD genes are co-expressed in LUAD without genetic lesions. c SQ-related gene scores for EGFR-mutant organoid lines. Pre-EGFR-TKIs (n = 7 lines), LUAD with genetic lesions (n = 12 lines), LUAD without genetic lesions (n = 11 lines), SQ-T (n = 1 line), SQ (n = 5 lines). Each dot shows SQ-related gene scores for one organoid line. Box plots represent the median (center line), upper and lower quartiles (box limits) and 1.5× interquartile range (whiskers). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. d Coverage of SQ specific ATAC peaks in EGFR-mutant organoid lines. The mean coverage of each peak is shown per subtype. SQ_up indicates upregulated genes in SQ (red). SQ_down indicates downregulated genes in SQ (blue). e scRNA-seq analysis and UMAP embedding of treatment-naïve LUAD, intermediate LUAD and SQ(-T) organoids. The samples were integrated using Harmony. The cell numbers for the UMAP plot are 1797 for E-01A (pre EGFR-TKIs), 4574 for E-05 (pre EGFR-TKIs), 3740 for E-14 (intermediate LUAD), 6924 for E-17 (intermediate LUAD), 1338 for E-20 (intermediate LUAD), 3280 for KOR386 (SQ), 4710 for KOR484 (SQ) and 6777 for E-12 (SQ-T). f Immunofluorescence TAp63 and AQP5 staining in E-13, E-14, E-17, E-20 and E-23 organoid lines with EGFR-TKI resistance and without known genetic lesions. Scale bar: 50 μm. g Representative H&E staining and NKX2-1, ΔNp63 and AQP5 immunostaining of E-23 patient tumors. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Although these results suggested that the hybrid SQ/LUAD identity characterizes the intermediate population, whether it reflects tumor heterogeneity comprising quasi-SQ and -LUAD cells, or homogeneous cells co-expressing both lineage markers remained unclear due to the limited resolution of bulk transcriptome analysis. To address this question, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis of a total of 8 organoid lines encompassing 2 LUAD (E-01A, E-05), 2 SQ (KOR386, KOR484), 1 SQ-T (E-12) and 3 intermediate LUAD organoids (E-14, E-17 and E-20) (Fig. 3e). Data integration followed by uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) depicted three distinct subgroups, each corresponding to LUAD, SQ/SQ-T and intermediate LUAD (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 4a). Pseudotime intervened intermediate tumor cells between LUAD and SQ/SQ-T cells, consistent with their partial retention of LUAD traits and acquisition of SQ features (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Intermediate tumor cells expressed LUAD and SQ genes, which distinguished LUAD and SQ/SQ-T cells in the first primary component in PCA analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4c), at variable degrees yet at lower extents than LUAD and SQ/SQ-T cells (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e). Per-sample analysis further revealed that intermediate samples comprise tumor cells with a high expression of LUAD- or SQ-related genes in a mutually exclusive fashion (Supplementary Fig. 5).

To visualize the co-expression of LUAD and SQ markers in intermediate LUAD, we performed immunohistochemistry analysis using single cell-derived organoids. Given the variable loss of LUAD markers in the transcriptome of intermediate organoids, we selected AQP5, which was relatively conserved in the intermediate population, as an alveolar/LUAD marker, and TP63 as a SQ marker (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig 6a). Immunostaining of organoids revealed heterogenic expression of AQP5 and TAp63/ΔNp63 at variable degrees in single organoids, with rare co-expression of both markers (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 6b–d). Based on these results, we refer to intermediate LUAD retaining both LUAD and SQ markers as basal-shift LUAD.

Xenograft tumors of basal-shift LUAD organoids maintained the expression of AQP5 and TP63, excluding the possibility that the basal-shift phenotype was an artifact of in vitro culture (Supplementary Fig. 6e, f). We further confirmed the concomitant expression of AQP5 and ΔNp63 in the tumors of E-23 patient after Osimertinib treatment (Fig. 3g). These results collectively suggest that LUAD tumors adopt basal-shift as one of the strategies to tolerate EGFR-TKI treatment.

NKX2-1 loss confers EGFR-TKI resistance through basal-shift transformation

To gain better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the basal-shift transformation along with the acquisition of EGFR-TKI resistance, we explored genetic alterations that potentially contribute to the basal-shift phenotype. Analysis of genetic alterations in basal-shift versus non-basal-shift, EGFR-TKI-treated LUAD organoids revealed a higher frequency of CDKN2A/B loss in basal-shift LUAD organoids (Fig. 4a). To clarify whether CDKN2A/B-null cells emerged de novo after EGFR-TKI treatment, we analyzed CDKN2A (p16) expression in the original cancer tissues using immunohistochemistry, which demonstrated the loss of p16 expression before EGFR-TKI treatment (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 7a). Organoid lines with CDKN2A/B loss, E-03, E-05, and E-06, were relatively sensitive to Osimertinib in vitro (Fig. 2b), and their parental tumors also showed clinical response to EGFR-TKI treatment. Moreover, TP53 and CDKN2A (TC) knockout in human normal alveolar organoids, which we previously performed38, failed to induce basal-shift phenotypes. Therefore, loss of CDKN2A/B was insufficient for basal-shift transformation and acquisition of EGFR-TKI resistance.

Fig. 4. NKX2-1 loss mediates EGFR-TKI resistance.

a Bar graphs showing the proportion of CDKN2A/B loss in basal-shift (n = 5) and non-basal-shift (n = 17) EGFR-mutant organoid lines. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. b Representative pictures of immunohistochemistry for CDKN2A protein in the E-12 and E-23 primary tissues before EGFR-TKI treatment. Scale bar: 100 μm. c Enriched and de-enriched motifs in the basal-shift LUAD lines (n = 5) compared to the pre-treatment LUAD lines (n = 6). The motifs were ranked based on the adjusted p values in motif enrichment analysis. d NKX2-1 staining in E-13, E-14, E-17, E-20 and E-23 organoid lines. LUAD and SQ-T lines were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Scale bar: 100 μm. e Additional knockout of NKX2-1(N) in TP53 (T) and CDKN2A (C) double knockout human alveolar organoids. Confirmation of NKX2-1 knockout in TCN organoids by sanger sequencing (bottom). f Representative NKX2-1 and TAp63 staining in normal alveolar, alveolar_TC and alveolar_TCN lines. Scale bar: 100 μm. At least five independent organoids were evaluated with similar results. g Immunofluorescence staining of TAp63 and AQP5 in an alveolar_TCN organoid. Scale bar: 50 μm. At least five independent organoids were evaluated with similar results. h PCA analysis of lung cancer organoid transcriptomes including genetically engineered alveolar organoids (alveolar_TC and alveolar_TCN). i The growth of the indicated organoid lines in the complete medium containing EGF (E), IGF-1 (I) and FGF-2 (F), and the condition without EIF. The figure indicates the organoid area relative to the control (complete). The experiments were performed in quadruplicate for each condition, technical replicates. Scale bar: 1 mm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To identify other non-genetic mediators of basal-shift, we examined the ATAC-seq profile of conventional and basal-shift LUAD organoids. Motif analysis of differentially accessible ATAC-seq peaks revealed distinct transcription factor (TF) activities between the two LUAD organoid types (Fig. 4c). Consistent with the basal-like gene expression patterns in basal-shift LUAD organoids, they exhibited increased activities of GRHL2 and TP63 which regulate the squamous-cell identity. To investigate whether TP63 activation alone confers EGFR-TKI resistance, we overexpressed TP63 in two EGFR-TKI- naïve LUAD organoid lines with EGFR mutation (E-01A and E-05) (Supplementary Fig. 7b). However, overexpression of TP63 did not alter the sensitivity to Osimertinib, suggesting that TP63 activation alone does not confer EGFR-TKI resistance through basal-shift transformation (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Interestingly, basal-shift LUAD organoids also displayed a decreased activity of NKX2-1, a TF of the lung alveolar identity. RNA-seq and immunohistochemistry confirmed decreased expression of NKX2-1 in basal-shift LUAD organoids (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 7d).

To determine the role of NKX2-1 loss in basal-shift transformation, we introduced sgRNAs targeting NKX2-1 to treatment-naïve LUAD organoid lines (E-01A, E-05 and E-06) with EGFR mutation (Supplementary Fig. 7e). Immunoassay confirmed successful knockout of NKX2-1 (Supplementary Fig. 7f). Following a one-month exposure to Osimertinib, NKX2-1-knockout organoids showed an upregulation of TP63 and its target genes (Supplementary Fig. 7b, g). NKX2-1-knockout organoids also gained resistance to Osimertinib (Supplementary Fig. 7h). These results suggest that defective NKX2-1 not only mediates basal-shift transformation through de novo TP63 expression but is also essential for EGFR-TKI resistance.

To further investigate the role of NKX2-1 loss in basal-shift, we leveraged gene engineering of human alveolar epithelial cells, which serve as the cells-of-origin of LUAD, and generated TC-NKX2-1 triple knockout (TCN) human alveolar organoids by introducing NKX2-1 sgRNA to TC organoids (Fig. 4e). We used two TC organoid lines derived from different donors to establish two independent TCN lines. Interestingly, NKX2-1 knockout induced de novo expression of TP63 in TC organoids while retaining AQP5 expression (Fig. 4f, g, Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). The global gene expression pattern of TCN organoids shifted towards that of airway/SQ organoids (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 8c), whereas TC organoids preserved an intact alveolar gene expression pattern. These results suggested that NKX2-1 loss disrupts the alveolar identity while inducing basal-shift transformation. Consistent with the transcriptomic basal-shift, TCN organoids showed EGF/IGF1/FGF2-independent growth, a characteristic of basal cell-derived airway organoids33 (Fig. 4i). Osimertinib reduced the phosphorylation of EGFR and ERK in basal-shift LUAD organoids, despite the failure to inhibit their growth (Supplementary Fig. 8d). At the transcriptome level, both treatment-naïve and basal-shift exhibited an upregulation of immediate response genes following Osimertinib treatment, whereas replication-related genes were downregulated only in treatment-naïve organoids (Supplementary Fig. 8e). These results suggested that basal-shift and airway organoids can grow independent of tyrosine kinase receptors and their downstream signal activation. Together, in the context of sustained EGFR inhibition, loss of NKX2-1 commits alveolar cells toward the basal cell-like state and alters the cell-autonomous niche dependence, thereby providing EGFR pathway independency.

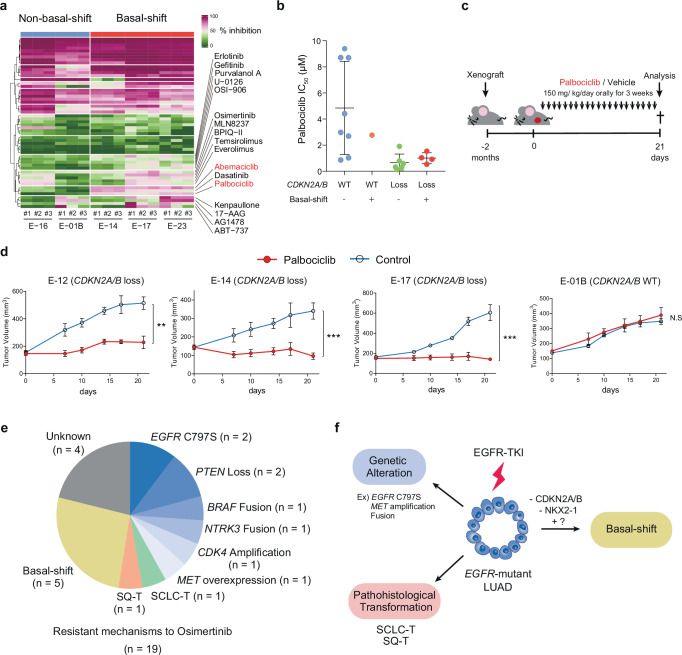

CDK4/6 inhibitors therapeutically target basal-shift LUAD organoids

To explore candidate drugs with a potential therapeutic effect on basal-shift LUAD with EGFR-TKI resistance, we performed high-throughput screening of 54 small molecule compounds targeting oncogenic pathways43 using two non-basal-shift LUAD organoid lines and three basal-shift organoid lines (Supplementary Data 2). Consistent with the frequent loss of CDKN2A/B in basal-shift LUAD, the screening revealed a higher sensitivity to CDK inhibitors including CDK4/6 inhibitors (Palbociclib and Abemaciclib) in basal-shift organoids than in non-basal-shift organoids (Fig. 5a). As expected, the growth retardation was explained by cytostatic effect of CDK4/6 inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Secondary testing of CDK4/6 inhibitors on a larger set of lung cancer organoids validated the correlation between the therapeutic effect of CDK4/6 inhibitors and the presence of CDKN2A/B loss in EGFR-mutant lines (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 9b). Notably, regardless of basal-shift or non-basal-shift, LUAD organoids with CDKN2A/B loss were sensitive to CDK4/6 inhibitor (Fig. 5b). As compared with EGFR-mutant LUAD, KRAS-mutant LUADs were relatively resistant to CDK4/6 inhibitors, despite the presence of CDKN2A/B loss (Supplementary Fig. 9c, d), suggesting that the effect of CDK4/6 inhibitor depends on the genetic background in LUAD.

Fig. 5. Therapeutic Effect of CDK4/6 Inhibitors on EGFR-mutant Lung Cancer with CDKN2A/B Loss.

a A heatmap showing the therapeutic landscape of 54 compounds in basal-shift (E-14, E-17 and E-23) and non-basal-shift organoid (E-01B and E-16) lines. Percent growth inhibition for each compound versus DMSO is shown in triplicate. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. b IC50 values of Palbociclib for the four distinct groups: (1) non-basal-shift organoids with CDKN2A/B WT, (2) basal-shift organoids with CDKN2A/B WT, (3) non-basal-shift organoids with CDKN2A/B loss, (4) basal-shift organoids with CDKN2A/B loss. Each dot shows one line. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. Each dot represents the IC50 value for each line obtained from four technical replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. c Overview of Palbociclib treatment in mouse xenografts. d The effect of Palbociclib on xenografts of CDKN2A/B loss (E-12, E-14 and E-17) or CDKN2A/B WT (E-01B) organoids. n = 5 tumors for each condition. Data are shown as mean ± SD. E-12 **p = 0.0021, E-14 ***p = 0.0008, E-17 ***p = 0.0004, t-test (two-sided). N.S. not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. e Mechanisms of Osimertinib resistance in ELCOL incorporating basal-shift. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. f The role of basal-shift and other mechanisms in the acquisition of EGFR-TKI resistance.

To investigate the therapeutic effect of CDK4/6 inhibitor in vivo, we generated mouse xenografts using basal-shift LUAD organoids (E-14 and E-17), SQ-T (E-12) organoids, and non-basal-shift LUAD organoids (E-01B) (Fig. 5c). Following xenograft implantation and growth (>100 mm3), the mice were treated with either Palbociclib or vehicle for three weeks. Consistent with the in vitro data, Palbociclib treatment suppressed the growth of basal-shift LUAD organoids while having no effect on non-basal-shift LUAD organoids (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 9e). Palbociclib also showed a therapeutic effect on SQ-T organoid xenografts, suggesting that CDKN2A/B loss rather than basal-shift per se renders vulnerability to CDK4/6 blockade (Fig. 5d). These findings provide preclinical evidence that supports the implementation of CDK4/6 inhibitors for treating EGFR-TKI-resistant basal-shift LUAD with CDKN2A/B loss.

Validation of basal-shift in clinical specimens with EGFR-TKI resistance

To confirm the clinical relevance of basal-shift transformation, we performed pathological evaluation of re-biopsied samples obtained in a defined period (2017/Jan to 2023/Dec), consisting of 32 and 21 samples obtained after acquisition of resistance to 1st/2nd generation EGFR-TKIs and Osimertinib, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Based on our observations, basal-shift LUAD were defined based on the following criteria; (1) NKX2-1 expression positivity <5%, (2) expression of TAp63 or ΔNp63, and (3) expression of AQP5. These criteria diagnosed 4 cases with basal-shift LUAD in this cohort (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 10b). These samples exhibited heterogenic expression of AQP5 and TAp63 or ΔNp63 with occasional co-expression of both markers at variable degrees (Supplementary Fig. 10c), validating the existence of basal-shift transformation. Together, comprehensive phenotypic, genetic and epigenetic profiling of ELCOL identified a subgroup with basal-shift features in EGFR-TKI-resistant lung cancers (Fig. 5e, f).

Discussion

The advent of EGFR-TKI has dramatically transformed the therapeutic paradigm in EGFR-mutant lung cancer from conventional chemotherapy to targeted therapy. However, the near-inevitable development of drug resistance within 1-2 years after the inception of EGFR target therapy has emerged as a critical determinant of the clinical outcome in patients with EGFR-mutant LUAD. Recent sequencing studies have identified secondary genetic hits accounting for approximately one-third of the cases with Osimertinib resistance, yet the mechanism of drug-resistance in the remaining majority have yet to be clarified. ELCOL established in this study provides a valuable biological resource that aids in the functional drug testing of patient tumors and in the fundamental understanding of mechanisms that underlie their drug resistance.

Unlike genetic mutations that can be captured by sequencing, non-genetic lesions responsible for drug resistance have been challenging to identify. To resolve this issue, we here established a living biobank consisting of 39 lines of EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoids derived from pre- and post- EGFR-TKI treatment samples. Patient-derived lung cancer organoids faithfully recapitulated the drug sensitivity expected from the response of the parental clinical tumors. The predictive value of organoid drug testing has also been reported in LUAD and other cancer types36–39,44. Previous organoid resources included sporadic EGFR-TKI-resistant lines, whereas our library encompasses multiple EGFR-TKI-resistant lines and various mechanisms of resistance, including known genetic alterations and histological transformation from LUAD to SCLC, LCNEC, and SQ. Transcriptome analysis of histologically transformed organoids revealed their loss of the original LUAD identity and acquisition of gene expression patterns pertinent to the acquired histology, suggesting the contribution of genetic reprogramming during therapy-related histological transformation. Importantly, these histologically transformed lung cancer organoids exhibited resistance to Osimertinib in vitro. These findings suggest that LUADs converts their histological identity to adapt to an EGFR-inhibitory environment. Together, our ELCOL that captures various routes to EGFR-TKI resistance provides a valuable resource for gaining mechanistic insights into the biology and treatment of EGFR-mutant LUAD.

Although the genetic alterations and histological transformation underlie EGFR-TKI resistance in around a half of the cases, the mechanisms driving resistance in the remaining individuals are still poorly understood. As one of such mechanisms, we identified a unique subtype in EGFR-TKI-resistant LUADs characterized by the bi-lineage expression of LUAD and SQ markers, which we referred to as basal-shift LUAD. Basal-shift LUADs accounted for 26.3% (5 out of 19) of the Osimertinib-resistant LUAD organoids and 9.5% of the Osimertinib-resistant clinical specimens at our institution. Given the higher proportion of basal-shift LUAD in the LUAD organoid library than in clinical samples, organoid derivation from basal-shift LUAD may be more efficient than from non-basal-shift LUAD, but further investigation is required to confirm this possibility.

Basal-shift in LUAD may reflect lineage plasticity, which has emerged as an alternative mechanism of treatment resistance that can bypass resistance-related genetic mutations. Recent evidence has suggested that tissue plasticity is preceded by genomic or epigenetic loss of transcription factors that specify the original tissue identity. We previously showed that the altered lineage identity is linked with not only histological morphology and gene expression patterns but also niche factor dependency45. Basal-shift transformation in LUAD is reminiscent of basal-like transition in human pancreatic cancer characterize by the loss of GATA6, upregulation of TP63, and subsequent acquisition of Wnt signal independency46,47. Our previous study also demonstrated that knockout of NKX2-1, a regulator of the alveolar identity, confers Wnt-driven growth along with characteristic expression of gastric markers, including HNF4A and MUC6, in LUAD organoids38. In contrast, NKX2-1 knockout induced TP63 expression but not HNF4A in the present study. These discrepant impacts of NKX2-1 loss in LUAD might be explained by the scenario where differing tissue environments drive commitment towards divergent lineages during tissue transdifferentiation. Specifically, Wnt-rich environments drive gastric transdifferentiation in NKX2-1-lost LUAD, whereas basal-shift transformation occurs specifically in the context of EGFR signal blockage, consistent with the rare occurrence of basal-shift in treatment-naïve LUAD. Similar treatment-related lineage transition has become apparent especially in prostate cancer, and the emergence of such lineage-plastic cancers suggests that specific tissue environments select cancer cells that acquired the fittest tissue lineage through epigenetic changes.

De novo expression of squamous markers in LUAD is evident in several situations, including basal-shift, adenosquamous carcinoma, and SQ-T. Adenosquamous carcinoma by definition consists of NKX2-1+LUAD and NKX2-1- SQ components in a biphasic manner and is generally unrelated to EGFR-TKI therapy48, which makes it distinct from basal-shift and SQ-T cancers. SQ-T tumors are histologically indiscernible from SQ tumors, whereas basal-shift LUAD does not show typical squamous histology and retains LUAD marker expression. Whether basal-shift LUADs are en route to SQ-T or represent a distinct stable state remains elusive and requires longitudinal histological assessment of LUAD during the course of Osimertinib treatment and resistance acquisition.

Recurrent loss of CDKN2A/B in SQ-T and basal-shift LUAD suggested that the pre-existing driver gene mutations may prime LUAD for histological transformation or basal-shift after EGFR-TKI therapy. Prospective genetic manipulation in normal alveolar organoids further consolidated the relationship between (epi)genotypes and basal-shift phenotypes. Exploiting the recurrent CDKN2A/B loss in basal-shift LUADs, we have developed a therapeutic strategy using CDK4/6 inhibitors for basal-shift LUADs. The common use of CDK4/6 inhibitors Abemaciclib and Palbociclib for the treatment of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer49,50 in clinics encourages the clinical translation of CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy in basal-shift LUAD. Although our results indicate an association between the sensitivity to CDK4/6 inhibitors and CDKN2A/B loss, it remains unclear whether CDKN2A/B loss alone drives sensitivity to Palbociclib. Indeed, recent clinical trials failed to show the therapeutic efficacy of Palbociclib in patients with non-small cell lung cancer with CDKN2A/B alteration51 and SQ lung cancer52, despite frequent CDKN2A/B loss in SQ tumors. Therefore, synthetic sensitivity to Palbociclib may require other molecular lesions in addition to CDKN2A/B loss. In our study, two out of the three LUAD organoid lines with mutant KRAS and CDKN2A/B loss were resistant to Palbociclib, whereas those with mutant EGFR and CDKN2A/B loss were sensitive regardless of basal-shift transformation. Such context dependency suggests that EGFR and CDKN2A/B co-alteration is required for the anti-proliferative effect of Palbociclib. Our data further suggest the promising therapeutic effect of Palbociclib in conjunction with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Future clinical trials are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors in the treatment of basal-shift LUADs with CDKN2A/B loss.

In conclusion, our ECLOL illuminated a basal-shift transformation as a mechanism of EGFR-TKI resistance that accounts for approximately one-fourth of the cases with secondary resistance. Our findings underscore the translational value of harnessing phenotypically and clinically relevant models of drug resistance, including patient-derived organoids with clinically confirmed resistance, in comprehensively understanding resistance mechanisms and strategies to overcome treatment failure.

Methods

Ethics statement

Our research compiles with all relevant regulations. All clinical samples used for organoids establishment and biological analyses were obtained from patients at Keio University Hospital, Kawasaki Municipal Hospital, or Saiseikai Chuo Hospital with written informed consent prior to sample collection. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of each facility (approval number: 20110171). Gene engineering and animal experiments were conducted under the approval and guidance of the Gene Modification Safety Committee (approval number: D2016-039) and Laboratory Animal Centre of Keio University School of Medicine (approval number: A2022-054), respectively.

Establishment of EGFR-mutant lung cancer organoids

Clinical samples from patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer were sequentially collected between May 2018 and Dec 2023. The clinical samples used in this study included surgical resection, bronchoscopic biopsy, CT-guided needle biopsy, ascitic fluid, pleural effusion, cerebral spinal fluid and autopsy samples. Lung cancer organoids were established as we have previously reported38,45. Briefly, tissue samples were minced into 1 mm3- fragments using surgical scissors. The fragments were digested with Liberase TH (Roche) at 37 °C for 30 min. Digested pellets were treated with TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C for 10 min. The isolated cells were embedded in droplets of Matrigel Growth Factor Reduced (Corning) and overlaid with the culture medium: Advanced Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/F12 supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 1× B27 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 nM gastrin I (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mM N-acetylcysteine (Wako), 50 ng/ml mouse recombinant EGF (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 50 ng/ml human recombinant FGF-2 (Peprotech), 100 ng/ml human recombinant IGF-1 (BioLegend), 100 ng/ml mouse recombinant noggin (Peprotech), 1 μg/ml recombinant human R-spondin-1 (R&D), 5% Afamin-Wnt-3A serum-free conditioned medium53 and 500 nM A83-01 (Tocris). Plated organoids were maintained in a CO2 incubator with 5% CO2 and 20% O2, and the media were changed every 3 or 4 days.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed as previously described38. Briefly, the patient specimens and isolated xenografts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Organoid tissue blocks were prepared using iPGell (GSPG20-1, NIPPON Genetics Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Standard protocols were used for sectioning paraffin-embedded tissues and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry consisted of rabbit anti-Synaptophysin (proteintech, 17785-1-AP, 1:1500), mouse anti-CD56 (DAKO, M7304, 1:200), rabbit anti-Chromogranin A (abcam, ab15160, 1:1000), mouse anti- CDKN2A / p16INK4a (Gene Tex, GTX01783, 1:100), mouse anti-TTF1 (DAKO, M3575, 1:100), mouse anti-p63 (DAKO, M7317, 1:100), mouse anti-p40 (Nichirei, bc28, 1:2), rabbit anti-AQP5 (abcam, ab92320, 1:20). Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described38,45. The antibodies included rabbit anti-AQP5 (Abcam, ab92320, 1:20), mouse anti-p63 (DAKO, M7317, 1:200), and mouse anti-p40-deltaNp63 antibody (abcam, ab172731, 1:50) with subsequent labeling with Alexa Fluor 488-, 568- conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific). AQP5 expression was enhanced using the Alexa Fluor 488 Tyramide SuperBoost kit. The nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were captured using a BZ-X710 digital microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). The images were analyzed using Fiji Ver.2.9.0/1.53t and R software (Ver.4.0.1).

Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) analysis

WES analysis was performed as we have previously described38,45,54. Briefly, a QIAamp Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN) was used for DNA extraction. DNA quality was examined using agarose gel electrophoresis. Paired-end libraries (150 bp) were prepared using the SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit (Agilent Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was performed using a IIIumina NovaSeq instrument. The cleaned fastq files were mapped onto the human reference genome version GRCh37 (hg19) using BWA-MEM version 0.7.17 (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/)55. Somatic mutations, single nucleotide variations (SNVs), insertions, and deletions were detected using the Genome Analysis Toolkit version 4.1.9.0 (https://gatk.broadinstitute.org). Variant detection was performed using Mutect2. To remove germline variants, the detected variants were filtered by removing those detected with an allele frequency of 0.1% or more in the dbSNP or the Japanese germline variant database (the Human Genetic Variation Database). Furthermore, variants were filtered by removing those detected in at least two of the 23 normal organoids and 35 blood samples that were sequenced in our previous studies38,45,54. Data were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) under the accession numbers JGAS000610 (study) and JGAD000739 (dataset).

Copy number analysis

We performed copy number analysis based on the WES data. Read counts were first obtained from the BAM files using GATK CollectReadCounts. The read count files of normal organoids and blood samples that were sequenced in our previous studies were compiled into a panel of normal using GATK CreateReadCountPanelOfNormals. A panel of normal individuals was used to smooth read counts using GATK DenoiseReadCounts. Segmented copy number ratios were calculated using GATK Model Segments.

RNA extraction and sequencing

RNA sequencing of organoids was performed as previously reported54. The RNA quality was evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). The sequence library was prepared using the TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 (Illumina) and sequenced using a HiSeq 4000 or NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina). RNA sequencing was performed by AZENTA. Adaptors were removed from raw fastq files with cutadapt version 2.5 (https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/installation.html), and the reads were aligned to hg38 using STAR version 2.6.1 (https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR)56. The expression levels of human genes in Ensembl release 81 were estimated using RSEM version 1.3.3 (https://github.com/deweylab/RSEM)57. Gene expression analysis was performed using the R Bioconductor package DESeq258. The read count matrix was normalized with size factors, and a variance stabilizing transformation was performed using the vst function in DESeq2. Principal component analysis was performed using genes exhibiting large variance (standard deviation of log2 normalized expression values > 1). Cluster analysis was performed using the R Bioconductor package ConsensusClusterPlus (based on the Euclidean distance and PAM algorithm)59. Differentially expressed genes were identified using the nbinomLRT function in DESeq2. Gene ontology analysis was performed on the differentially expressed genes using enrichGO in the clusterProfiler R package version 3.18.1 (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html) and all gene ontology categories. To detect fusion transcripts, RNA-seq reads were aligned to hg38 using STAR-Fusion version 1.5.0 (https://github.com/STAR-Fusion/STAR-Fusion). Data were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) under the accession numbers JGAS000610 (study) and JGAD000739 (dataset). For gene set enrichment analysis, the genes were sorted according to the fold change values and the enrichment of immediate early genes60 and DNA replication genes (GO:0008283) derived from MSigDB database. We used the R Bioconductor package fgsea (v.1.28.0) with 10,000 permutations.

scRNA-sequencing

Two treatment-naïve LUAD (E-01A and E-05), three basal-shift LUAD (E-14, E-17 and E-20), one SQ-T (E-12) and two SQ (KOR386 and KOR484) organoid lines were used for scRNA-seq. The organoids were dissociated into single cells using TrypLE Express and passed through a 20-μm cell strainer, followed by dead cell staining with 7-AAD. Live single cells were collected using flow cytometry (SH800, Sony) and suspended in PBS supplemented with 0.04% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma Aldrich). The scRNA-seq libraries were prepared using the Chromium Controller and Chromium Next GEM Single cell 3’ GEM v3.1 chemistry (10x Genomics) targeting 5000 cell recovery per sample. The libraries were sequenced on NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) aiming to generate 50,000 paired-end reads per cell. The Cell Ranger pipeline (version 6.1.2, 10x Genomics) was used to map the raw sequencing reads onto the GRCh38 human genome and generate count data matrices.

Cell Ranger outputs were imported to and analyzed with Seurat v5 (version 5.0.1)61. Low quality cells with less than 1000 detected genes and containing mitochondrial genes in more than 25% of the total unique molecular identifier count. The count data were normalized using NormalizeData, and 3000 variably expressed genes were obtained using FindVariableFeatures function. The normalized data were scaled with ScaleData function while regressing out the percentage of mitochondrial gene reads. To regress out the effect of cell cycle, we ran CellCycleScoring using S and G2M features provided by Seurat and re-scaled the data with ScaleData while regressing out the percentage of mitochondrial reads, S-phase score and G2M-phase score. Dimensionality reduction was done using the RunPCA function. Data integration of all samples was performed using Harmony with the RunHarmony function62. To further filter low quality cells, we initially clusters the cells by running the FindNeighbors function on the Harmony space and then the FindClusters function with the resolution set to 1. Clusters with less than 2500 detected gene counts in more than 50% of the cells were filtered out. The filtered raw count data were re-processed by running again the same normalization and integration steps. To analyze the enrichment of LUAD- and SQ-related genes, we first retrieved these genes from the DESeq2-based bulk RNA-seq analysis of LUAD versus SQ organoids. To control the gene set size, we set a stringent cutoff of an absolute fold change >4 and adjusted p-value < 0.001, and the genes upregulated in LUAD or SQ organoids were defined as bulk LUAD or SQ genes, respectively. The enrichment of these gene sets was calculated using AddModuleScore. Lineage inference and pseudotime calculation was done using Slingshot (version 2.10.0)63. To construct cell lineages, we first performed a rough cell clustering FindClusters with the resolution set to 0.25, and ran Slingshot with the starting cluster set to the cluster with the highest enrichment of bulk LUAD genes. Per-sample analysis of basal-shift samples was done using the same workflow except for data integration.

ATAC-sequencing

ATAC-seq was performed as previously described, with minor modifications64,65. For library preparation, organoids were dissociated into single cells and pretreated with DNase (Worthington) for 10 min at 37 °C to remove DNA derived from dead cells. The medium was washed and the cells were resuspended in cold PBS. 50,000 cells were resuspended in 50 μL of ATAC-seq resuspension buffer (RSB; 10 mM Tris-HCI pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, and 3 mM MgCl2 in distilled water) containing 0.1% NP40, 0.1% Tween-20, and 0.01% digitonin, and incubated on ice for 3 min. After lysis, 1 mL of ATAC-seq RSB containing 0.1% tween-20 was added, and the lysate was centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was removed, and nuclei were resuspended in 50 μL of transposition mix (25 μL TD buffer, 2.5 μL Tn5 transposase, 16.5 μL PBS, 0.5 μL 1% digitonin, 0.5 μL 10% Tween-20, and 5 μL water) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a Thermomixer shaking at 1000 rpm. The transposed DNA was purified using QIAgen MinElute columns and subsequently amplified using Nextera sequencing primers and NEB high-fidelity 2× PCR master mix for 5–10 cycles. The PCR-amplified DNA was purified using QIAgen MinElute columns and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X with 150 bp pair-end reads. For alignment, raw reads were trimmed using cutadapt version 1.18 and mapped onto hg38 using Bowtie2 version 2.3.4.3 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/bowtie-bio/files/bowtie2/)55,66 to sort and remove the reads that mapped to the mitochondrial genome. Picard version 2.18.16 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) was used to remove duplicates using the MarkDuplicates tool. Peak calling was performed using MACS2 version 2.1.2 (https://github.com/macs3-project/MACS)67 with the parameters “-nomodel-call-summits-nolambda-keep-dup all-shift-75-extsize 150.” All the peaks were resized to a uniform width of 501 bp, centered at the summit, and filtered using the ENCODE hg38 blacklist (http://www.encodeproject.org/annotations/ENCSR636HFF/). Peaks that overlapped the regions −1000 to +100 bp from the transcription start sites were excluded from further analysis. Motif analysis was performed for basal-shift and treatment-naïve lines using HOMER68 with the other set to the background, and log10 P values were plotted using a waterfall plot. Data were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) under the accession numbers JGAS000610 (study) and JGAD000739 (dataset).

In vitro cell viability assay

The cell viability assay was performed using CellTiter-Glo (Promega) following the manufacturer’s protocol, as we previously described38. Organoids were seeded in 96-well plates (1500 cells/well) and treated with Osimertinib, Palbociclib and Abemaciclib. The control cells were treated with DMSO at the same concentration. Absorbance was measured seven days after treatment with Cytation5 (BioTek, #MO1210) or GloMax (Promega). IC50 values were calculated using Prism software (GraphPad Prism 7.04).

Western blot analysis

Protein separation and detection were performed using the Jess Simple Western system as previously described38. For protein detection, antibodies included rabbit anti-TTF1 (abcam, ab76013, 1:50), rabbit anti-β-actin (CST, 4970, 1:50), rabbit anti-phospho EGFR (Thermo, 44788G-3,1:50), rabbit anti-total EGFR (CST, 4267,1:50), rabbit anti-phospho ERK (CST, 9101,1:50) and rabbit anti-total ERK (CST, 9102,1:50), with subsequent labeling by an HRP-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody. The signals were then visualized using Compass Software for Simple Western.

Cell cycle analysis

Organoids were treated with RNase and Propidium Iodide after fixation with cold 70% ethanol. The propidium iodide intensity was measured to quantify DNA content using a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX S, Beckman Coulter Life Sciences) and analyzed using Flow Jo v10 (Becton Dickinson).

Gene engineering experiments

Gene engineering of LUAD/human alveolar cells was performed as previously reported38. ForNKX2-1 gene knockout using CRISPR-Cas9, a gene specific single-guide RNA (sgRNA); GGAGGAAAGCTACAAGAAAG(#1) or CAAGCAACAGAAGTACCTGT(#2) was cloned into the pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 vector (Addgene #42230). For ΔNp63 overexpression, cDNA was cloned into the PB-CMV-MCS-EF1a-GFP-Puro vector (System Biosciences#PB513B-1) using the Xbal and Notl digestion sites. The vectors were co-electroporated with transposase (System Biosciences) and organoids were selected by GFP-positive cell sorting. Knockout of NKX2-1 was validated by isolating genomic DNA from cloned engineered organoids, followed by PCR amplification of targeted loci (GCTGTTCCTCATGGTGTCCT and ATCCAACAAGATCGGCGTTA for #1, CGGTTTGCCGTCTTTCAC and TGCGTTTGTCGCTTACAGTC for #2), Sanger sequencing and allelic deconvolution of the PCR products using the ICE v.3 online software (Synthego). ΔNp63 overexpression was confirmed by immunohistochemistry and RNAseq data.

Drug screening experiments

In vitro drug screening experiments were performed using 3 basal-shift LUAD lines (E-14, -17, and -23) and two non-basal-shift lines (E-01B and -16). The experiments were performed in triplicate for each line. A total of 1500 cells were plated in wells of 96 well plates. The organoid lines were cultured with 54 inhibitors for 7 days. Relative cell viability in each well was measured using GloMax (Promega).

Xenotransplantation of organoids and animal experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the Laboratory Animal Center of Keio University School of Medicine (approval number: A2022-054). Xenotransplantation experiments were performed as previously described38. Female NOG (NOD/Shi-scid, IL-2RγKO Jic) mice (5 weeks old, approximately 20 g/mouse) were purchased from Charles River, Japan. Mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions, maintained at a temperature of 20–26 °C and relative humidity of 40–60%, under a 12-h:12-h light: dark cycle. For each transplantation, organoid clusters (approximately 1 × 105 cells) were suspended in 50 μL of Matrigel and implanted subcutaneously into the mice. The mice were euthanized 2 or 3 months after transplantation. For in vivo efficacy experiments with palbociclib, tumor volumes were monitored at 2–3 weeks intervals for up to 3 months. The length (L), width (W), and height (H) of each tumor were measured using calipers, and the tumor volume (TVs) was calculated as TV = (L × W × H/2). Once the average TV reached approximately 100 mm3, the mice were randomized to receive either vehicle alone or palbociclib (150 mg/kg/day, orally for 3 weeks). During drug treatment, body weight was also monitored during TV measurements. The mice were sacrificed 3 weeks after drug treatment and the tumors were isolated. The maximal tumor diameter (20 mm) was not exceeded defined by Laboratory Animal Centre of Keio University School of Medicine.

Statistical analysis

Pairwise analyses for gene expression, IC50, tumor volumes, and immunohistochemistry values were performed using Wilcoxon’s rank sum test or the Chi-squared test. The level of significance is indicated by the P value in each experiment. Asterisks in the figures indicate the following: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. P > 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 7.04 statistical software (GraphPad Prism Corp., California, USA).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank Chinatsu Yonekawa for her technical assistance. This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant numbers 19cm0106206h0004 and 20gm1210001 to T. Sato, 21cm0106576h0002 and 23ck0106722h0002 to H.Y., by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant number JP21H02765, JP22K08290 and JP21J12157) to H.Y., J.H. and T. Shinozaki, by JST Moonshot R&D (Grant Number JPMJMS2022) to T. Sato., by JST FOREST (Grant Number JPMJFR2215) to H.Y. and Doctoral Student Grant-in-Aid Program by the Ushioda Memorial Fund and the JSPS Research Fellowships for Young Scientists to T. Shinozaki. This work was supported by JST ERATO JPMJER2303 to T. Sato. This work is also supported by the Takahashi Industrial and Economic Research Foundation to H.Y. This work is also supported by the Masabumi Mori Endowed Research Laboratory for Conquering Lung Cancer to H.Y. and K.F.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, T. Shinozaki, K.T., J.H., H.Y. and T. Sato; Methodology, T. Shinozaki, K.T., J.H, M.F., H.Y. and T. Sato; Investigation, T. Shinozaki, K.T., J.H., L.S., H. Takaoka, Y.O., S.T., M. Oda, M.S., M.M., M.F., H.Y., and T. Sato; Formal Analysis, T. Shinozaki, K.T, J.H., Y.O., S.T., M. Oda, M.S., M.M., and M.F.; Resources, T. Shinozaki, A.M., T.F., K. Sugihara, T.E., M. Okada, A.S., L.S., H. Takaoka, F.I., K.O., K.I., K.W., T. Hishima, H. Terai, S.I., I. K., K.A., T. Hishida, H.A., K. Soejima, K.F., H.Y.; Visualization, T. Shinozaki, K.T., J.H., Y.K., K.E., Y.O., S.T., M. Oda and M.F.; Writing, T. Shinozaki, J.H., M.F., H.Y., and T. Sato; Funding Acquisition, T. Shinozaki, J.H., K.F., H.Y., and T. Sato; Project Administration, H.Y. and T. Sato.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Whole-exome sequencing, RNA-sequencing and ATAC-sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) database under the accession number JGAS000610 (study) and JGAD000739 (dataset) (https://humandbs.dbcls.jp/en/hum0357-v6). These data are under controlled access because they are personally identifiable data defined by Japan’s Personal Information Protection Law. Use of the data requires approval by the Human Data Review Board of National Bioscience Database Center (NBDC). Data users shall apply for data use in accordance with the data use application procedures (https://humandbs.biosciencedbc.jp/en/data-use). Data must be used in compliance with NBDC Guidelines for Human Data Sharing and NBDC Security Guidelines for Human Data (for Data Users) https://humandbs.dbcls.jp/en/guidelines/data-sharing-guidelines, https://humandbs.dbcls.jp/en/guidelines/security-guidelines-for-users. The following website summarizes how to use the controlled access data: https://humandbs.dbcls.jp/en/data-use. Contact information to request access is: https://humandbs.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/nbdc/application/. Restrictions on who the data can be made available to or for which purpose are described in the following guidelines https://humandbs.dbcls.jp/en/guidelines/data-sharing-guidelines. Basic rules to be complied with in using data are: The data users must be limited. Access is granted only to the Principal Investigator and his/her research collaborators who belong to the same organization as the Principal Investigator. / The purpose of data use must be explicitly stated. / The use of data for purposes other than those stated in the application is prohibited. / The use of data is limited to research and/or development purposes only. / Identification of individuals is prohibited. / Redistribution of data is prohibited. The expected timeframe for response to access requests is about 1 month. Data is available for a period approved by the Human Data Review Board of NBDC. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

T.S. is an inventor on several patents related to organoid culture. We declare that none of the authors have competing financial or non-financial interests as defined by Nature Portfolio.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Taro Shinozaki, Kazuhiro Togasaki, Junko Hamamoto.

Contributor Information

Hiroyuki Yasuda, Email: hiroyukiyasuda@keio.jp.

Toshiro Sato, Email: t.sato@keio.jp.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-59623-3.

References

- 1.Paez, J. G. et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science304, 1497–1500 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch, T. J. et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med.350, 2129–2139 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mok, T. S. et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med.361, 947–957 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosell, R. et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.13, 239–246 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sequist, L. V. et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J. Clin. Oncol.31, 3327–3334 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soria, J. C. et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.378, 113–125 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi, S. et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med.352, 786–792 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok, T. S. et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.376, 629–640 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross, D. A. et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov.4, 1046–1061 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blakely, C. M. et al. Evolution and clinical impact of co-occurring genetic alterations in advanced-stage EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Nat. Genet.49, 1693–1704 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Passaro, A., Janne, P. A., Mok, T. & Peters, S. Overcoming therapy resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Nat. Cancer2, 377–391 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piper-Vallillo, A. J., Sequist, L. V. & Piotrowska, Z. Emerging Treatment Paradigms for EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancers Progressing on Osimertinib: A Review. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 2926–2936 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Piotrowska, Z. et al. Landscape of acquired resistance to osimertinib in EGFR-mutant NSCLC and clinical validation of combined EGFR and RET inhibition with osimertinib and BLU-667 for acquired RET fusion. Cancer Discov.8, 1529–1539 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oxnard, G. R. et al. Assessment of resistance mechanisms and clinical implications in patients with EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer and acquired resistance to osimertinib. JAMA Oncol.4, 1527–1534 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le, X. et al. Landscape of EGFR-dependent and -independent resistance mechanisms to osimertinib and continuation therapy beyond progression in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Clin. Cancer Res.24, 6195–6203 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chmielecki, J. et al. Analysis of acquired resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer from the AURA3 trial. Nat. Commun.14, 1071 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chmielecki, J. et al. Candidate mechanisms of acquired resistance to first-line osimertinib in EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun.14, 1070 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown, B. P. et al. On-target resistance to the mutant-selective EGFR inhibitor osimertinib can develop in an allele-specific manner dependent on the original EGFR-activating mutation. Clin. Cancer Res.25, 3341–3351 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fassunke, J. et al. Overcoming EGFR(G724S)-mediated osimertinib resistance through unique binding characteristics of second-generation EGFR inhibitors. Nat. Commun.9, 4655 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thress, K. S. et al. Acquired EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to AZD9291 in non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M. Nat. Med.21, 560–562 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederst, M. J. et al. The allelic context of the C797S mutation acquired upon treatment with third-generation EGFR inhibitors impacts sensitivity to subsequent treatment strategies. Clin. Cancer Res.21, 3924–3933 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dagogo-Jack, I. et al. Response to the combination of osimertinib and trametinib in a patient with EGFR-mutant NSCLC harboring an acquired BRAF fusion. J. Thorac. Oncol.14, e226–e228 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang, Z. et al. Investigating novel resistance mechanisms to third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor osimertinib in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res.24, 3097–3107 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, R. et al. Transient IGF-1R inhibition combined with osimertinib eradicates AXL-low expressing EGFR mutated lung cancer. Nat. Commun.11, 4607 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taniguchi, H. et al. AXL confers intrinsic resistance to osimertinib and advances the emergence of tolerant cells. Nat. Commun.10, 259 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Offin, M., et al. Acquired ALK and RET gene fusions as mechanisms of resistance to osimertinib in EGFR-mutant lung cancers. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2, PO.18.00126 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Ishioka, K. et al. Upregulation of FGF9 in lung adenocarcinoma transdifferentiation to small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res.81, 3916–3929 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoenfeld, A. J. et al. Tumor analyses reveal squamous transformation and off-target alterations as early resistance mechanisms to first-line osimertinib in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.26, 2654–2663 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maynard, A. et al. Therapy-induced evolution of human lung cancer revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Cell182, 1232–1251 e1222 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashima, Y. et al. Single-cell analyses reveal diverse mechanisms of resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Res.81, 4835–4848 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilsson, M. B. et al. A YAP/FOXM1 axis mediates EMT-associated EGFR inhibitor resistance and increased expression of spindle assembly checkpoint components. Sci. Transl. Med.12, eaaz4589 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Shah, K. N. et al. Aurora kinase A drives the evolution of resistance to third-generation EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Nat. Med. 25, 111–118 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachs, N., et al. Long-term expanding human airway organoids for disease modeling. EMBO J.38, e100300 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Kim, S. Y. et al. Modeling clinical responses to targeted therapies by patient-derived organoids of advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.27, 4397–4409 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim, M. et al. Patient-derived lung cancer organoids as in vitro cancer models for therapeutic screening. Nat. Commun.10, 3991 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dijkstra, K. K. et al. Challenges in establishing pure lung cancer organoids limit their utility for personalized medicine. Cell Rep.31, 107588 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi, R. et al. Organoid cultures as preclinical models of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res26, 1162–1174 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebisudani, T. et al. Genotype-phenotype mapping of a patient-derived lung cancer organoid biobank identifies NKX2-1-defined Wnt dependency in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep.42, 112212 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, H. M. et al. Using patient-derived organoids to predict locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer tumor response: A real-world study. Cell Rep. Med.4, 100911 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature511, 543–550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.George, J. et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature524, 47–53 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudin, C. M. et al. Molecular subtypes of small cell lung cancer: a synthesis of human and mouse model data. Nat. Rev. Cancer19, 289–297 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toshimitsu, K. et al. Organoid screening reveals epigenetic vulnerabilities in human colorectal cancer. Nat. Chem. Biol.18, 605–614 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veninga, V. & Voest, E. E. Tumor organoids: opportunities and challenges to guide precision medicine. Cancer Cell39, 1190–1201 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujii, M. et al. Human intestinal organoids maintain self-renewal capacity and cellular diversity in niche-inspired culture condition. Cell Stem Cell23, 787–793.e786 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seino, T. et al. Human pancreatic tumor organoids reveal loss of stem cell niche factor dependence during disease progression. Cell Stem Cell22, 454–467.e456 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamagawa, H. et al. Wnt-deficient and hypoxic environment orchestrates squamous reprogramming of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Cell Biol.26, 1759–1772 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Tang, S. et al. Counteracting lineage-specific transcription factor network finely tunes lung adeno-to-squamous transdifferentiation through remodeling tumor immune microenvironment. Natl Sci. Rev.10, nwad028 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turner, N. C., Huang Bartlett, C. & Cristofanilli, M. Palbociclib in hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.373, 1672–1673 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Royce, M. et al. FDA approval summary: abemaciclib with endocrine therapy for high-risk early breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.40, 1155–1162 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahn, E. R. et al. Palbociclib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with CDKN2A alterations: results from the targeted agent and profiling utilization registry study. JCO Precis Oncol.4, 757–766 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edelman, M. J. et al. SWOG S1400C (NCT02154490)-a phase II study of palbociclib for previously treated cell cycle gene alteration-positive patients with stage IV squamous cell lung cancer (lung-MAP substudy). J. Thorac. Oncol.14, 1853–1859 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mihara, E. et al. Active and water-soluble form of lipidated Wnt protein is maintained by a serum glycoprotein afamin/alpha-albumin. Elife5, e11621 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Kawasaki, K. et al. An organoid biobank of neuroendocrine neoplasms enables genotype-phenotype mapping. Cell183, 1420–1435.e1421 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinforma.12, 323 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics26, 1572–1573 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tullai, J. W. et al. Immediate-early and delayed primary response genes are distinct in function and genomic architecture. J. Biol. Chem.282, 23981–23995 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol.42, 293–304 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Korsunsky, I. et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods16, 1289–1296 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Street, K. et al. Slingshot: cell lineage and pseudotime inference for single-cell transcriptomics. BMC Genomics19, 477 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buenrostro, J. D., Giresi, P. G., Zaba, L. C., Chang, H. Y. & Greenleaf, W. J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods10, 1213–1218 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Corces, M. R. et al. An improved ATAC-seq protocol reduces background and enables interrogation of frozen tissues. Nat. Methods14, 959–962 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol.9, R137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heinz, S. et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell38, 576–589 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement