Abstract

Understanding brain function relies on the collective work of many labs generating reproducible results. However, reproducibility has not been systematically assessed within the context of electrophysiological recordings during cognitive behaviors. To address this, we formed a multi-lab collaboration using a shared, open-source behavioral task and experimental apparatus. Experimenters in 10 laboratories repeatedly targeted Neuropixels probes to the same location (spanning secondary visual areas, hippocampus, and thalamus) in mice making decisions; this generated a total of 121 experimental replicates, a unique dataset for evaluating reproducibility of electrophysiology experiments. Despite standardizing both behavioral and electrophysiological procedures, some experimental outcomes were highly variable. A closer analysis uncovered that variability in electrode targeting hindered reproducibility, as did the limited statistical power of some routinely used electrophysiological analyses, such as single-neuron tests of modulation by individual task parameters. Reproducibility was enhanced by histological and electrophysiological quality-control criteria. Our observations suggest that data from systems neuroscience is vulnerable to a lack of reproducibility, but that across-lab standardization, including metrics we propose, can serve to mitigate this.

Research organism: Mouse

Introduction

Reproducibility is a cornerstone of the scientific method: a given sequence of experimental methods should lead to comparable results if applied in different laboratories. In some areas of biological and psychological science, however, the reliable generation of reproducible results is a well-known challenge (Crabbe et al., 1999; Sittig et al., 2016; Baker, 2016; Voelkl et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Errington et al., 2021). In systems neuroscience at the level of single-cell-resolution recordings, evaluating reproducibility is difficult: experimental methods are sufficiently complex that replicating experiments is technically challenging, and many experimenters feel little incentive to do such experiments since negative results can be difficult to publish. Unfortunately, variability in experimental outcomes has been well-documented on a number of occasions. These include the existence and nature of ‘preplay’ (Dragoi and Tonegawa, 2011; Silva et al., 2015; Ólafsdóttir et al., 2015; Grosmark and Buzsáki, 2016; Liu et al., 2019), the persistence of place fields in the absence of visual inputs (Hafting et al., 2005; Barry et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2016; Waaga et al., 2022), and the existence of spike-timing dependent plasticity (STDP) in nematodes (Zhang et al., 1998; Tsui et al., 2010). In the latter example, variability in experimental results arose from whether the nematode being studied was pigmented or albino, an experimental feature that was not originally known to be relevant to STDP. This highlights that understanding the source of experimental variability can facilitate efforts to improve reproducibility.

For electrophysiological recordings, several efforts are currently underway to document this variability and reduce it through standardization of methods (de Vries et al., 2020; Siegle et al., 2021). These efforts are promising, in that they suggest that when approaches are standardized and results undergo quality control (QC), observations conducted within a single organization can be reassuringly reproducible. However, this leaves unanswered whether observations made in separate, individual laboratories are reproducible when they likewise use standardization and QC. Answering this question is critical since most neuroscience data is collected within small, individual laboratories rather than large-scale organizations. A high level of reproducibility of results across laboratories when procedures are carefully matched is a prerequisite to reproducibility in the more common scenario in which two investigators approach the same high-level question with slightly different experimental protocols. Therefore, establishing the extent to which observations are replicable even under carefully controlled conditions is critical to provide an upper bound on the expected level of reproducibility of findings in the literature more generally.

We have previously addressed the issue of reproducibility in the context of mouse psychophysical behavior, by training 140 mice in 7 laboratories and comparing their learning rates, speed, and accuracy in a simple binary visually driven decision task. We demonstrated that standardized protocols can lead to highly reproducible behavior (Aguillon-Rodriguez et al., 2021). Here, we build on those results by measuring within- and across-lab variability in the context of intra-cerebral electrophysiological recordings. We repeatedly inserted Neuropixels multi-electrode probes (Jun et al., 2017) targeting the same brain regions (including secondary visual areas, hippocampus, and thalamus) in mice performing an established decision-making task (Aguillon-Rodriguez et al., 2021). We gathered data across 10 different labs and developed a common histological and data processing pipeline to analyze the resulting large datasets. This pipeline included stringent new histological and electrophysiological quality-control criteria (the ‘Recording Inclusion Guidelines for Optimizing Reproducibility’ [RIGOR]) that are applicable to datasets beyond our own.

We define reproducibility as a lack of systematic across-lab differences: that is, the distribution of within-lab observations is comparable to the distribution of across-lab observations, and thus a data analyst would be unable to determine in which lab a particular observation was measured. This definition takes into account the natural variability in electrophysiological results. After applying the RIGOR QC measures, we found that features such as neuronal yield, firing rate, and LFP power were reproducible across laboratories according to this definition. However, the proportions of cells modulated and the precise degree of modulation by single decision-making variables, such as the sensory stimulus or the choice, while reproducible for many tests and brain regions, sometimes failed to reproduce in some regions (tests that considered the a neuron’s full response profile were more robust). To interpret potential lab-to-lab differences in reproducibility, we developed a multi-task neural network encoding model that allows nonlinear interactions between variables. We found that within-lab random effects captured by this model were comparable to between-lab random effects. Taken together, these results suggest that electrophysiology experiments are vulnerable to a lack of reproducibility, but that standardization of procedures and QC metrics can help to mitigate this problem.

Results

Neuropixels recordings during decision-making target the same brain location

To quantify reproducibility across electrophysiological recordings, we set out to establish standardized procedures across the International Brain Laboratory (IBL) and to test whether this standardization led to reproducible results. Ten IBL labs collected Neuropixels recordings from one repeated site, targeting the same stereotaxic coordinates, during a standardized decision-making task in which head-fixed mice reported the perceived position of a visual grating (Aguillon-Rodriguez et al., 2021). The experimental pipeline was standardized across labs, including surgical methods, behavioral training, recording procedures, histology, and data processing Figure 1a, b, Figure 1—figure supplement 1; see Materials and methods for full details. Neuropixels probes were selected as the recording device for this study due to their standardized industrial production, and their 384 dual-band, low-noise recording channels providing the ability to sample many neurons in each of multiple brain regions simultaneously. In each experiment, Neuropixels 1.0 probes were inserted, targeted at 2.0 mm AP, -2.24 mm ML, 4.0 mm DV relative to bregma; 15° angle (Figure 1c). This site was selected because it encompasses brain regions implicated in visual decision-making, including visual area a/am (Najafi et al., 2020; Harvey et al., 2012), dentate gyrus (DG), CA1, (Turk-Browne, 2019), and lateral posterior (LP) and posterior (PO) thalamic nuclei (Saalmann and Kastner, 2011; Roth et al., 2016).

Figure 1. Standardized experimental pipeline and apparatus; location of the repeated site.

(a) The pipeline for electrophysiology experiments. (b) Drawing of the experimental apparatus. (c) Location and brain regions of the repeated site. VISa: Visual Area A/AM; CA1: Hippocampal Field CA1; DG: Dentate Gyrus; LP: Lateral Posterior nucleus of the thalamus; PO: Posterior Nucleus of the Thalamus. Black lines: boundaries of sub regions within the five repeated site regions. (d) Gray lines: Actual repeated site trajectories shown within a 3D brain schematic. Red line: planned trajectory. (e) Raster plot of all measured neurons (including some that ultimately failed quality control) from one example session. (f) A comparison of neuron yield (neurons/channel of the Neuropixels probe) for this dataset (IBL), Steinmetz et al., 2019 (STE), and Siegle et al., 2021 (ALN) in three neural structures. Bars: SEM; the center of each bar corresponds to the mean neuron yield for the corresponding study.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Detailed experimental pipeline for the Neuropixels experiment.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Electrophysiology data quality examples.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Detailed comparison of yield between our dataset and published reference datasets.

Figure 1—figure supplement 4. Visual inspection of datasets by three observers blinded to data identity yielded similar metrics for all three studies.

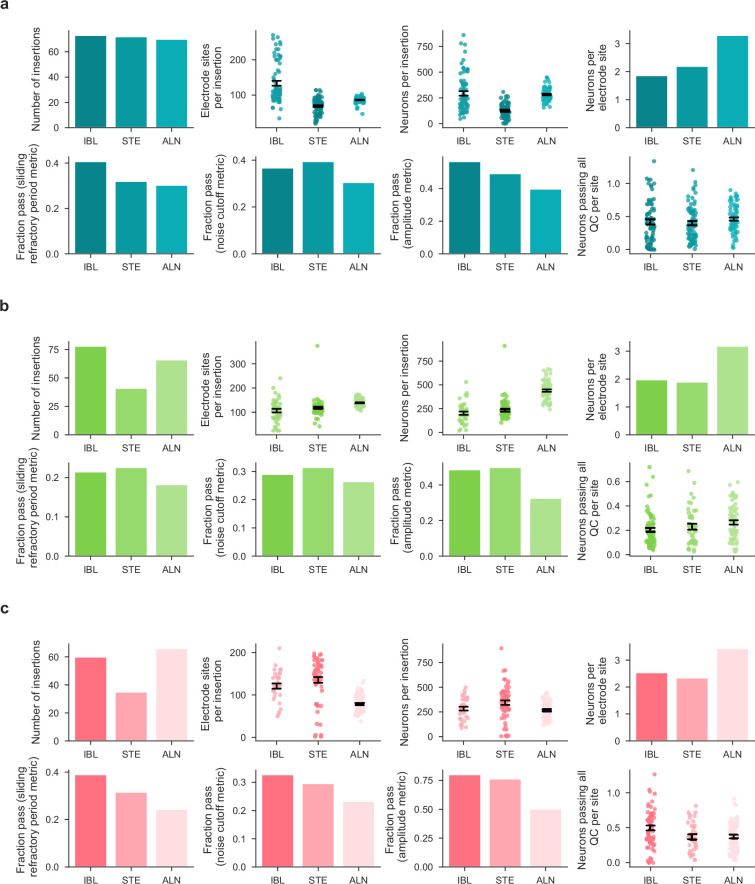

Once data were acquired and brains were processed, we visualized probe trajectories using the Allen Institute Common Coordinate Frame (Figure 1d, more methodological information is below). This allowed us to associate each neuron with a particular region (Figure 1e). To evaluate whether our data were of comparable quality to previously published datasets (Steinmetz et al., 2019; Siegle et al., 2021), we compared the neuron yield. The yield of an insertion, defined as the number of QC-passing units recovered per electrode site, is informative about the quality of both the raw recording and the spike sorting pipeline. We performed a comparative yield analysis of the repeated site insertions and the external electrophysiology datasets. Both external datasets were recorded from mice performing a visual task and included insertions from diverse brain regions.

Different spike sorting algorithms detect distinct units as well as varying numbers of units, and yield is sensitive to the inclusion criteria for putative neurons. We therefore re-analyzed the two comparison datasets using IBL’s spike sorting pipeline (Banga et al., 2022). When filtered using identical QC metrics and split by brain region, we found the yield was comparable across datasets within each region (Figure 1f). A two-way ANOVA on the yield per insertion with dataset (IBL, Steinmetz, or Allen/Siegle) and region (Cortex, Thalamus, or Hippocampus) as categorical variables showed no significant effect of dataset origin (p=0.31), but a significant effect of brain region (p < 10−17). Systematic differences between our dataset and others were likewise absent for a number of other metrics (Figure 1—figure supplement 3).

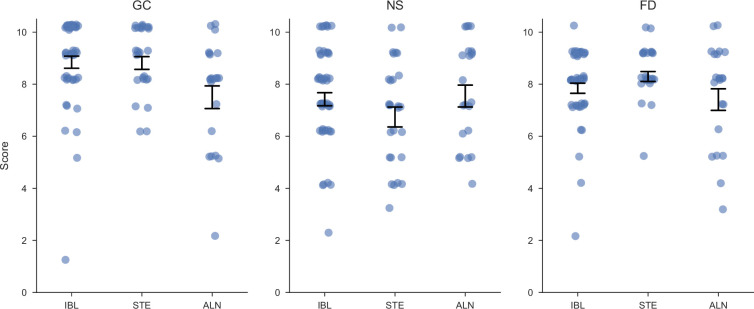

Finally, in addition to the quantitative assessment of data quality, a qualitative assessment was performed. 100 total insertions were randomly selected from the three datasets and assigned random IDs to blind the raters during manual assessment. Three raters were asked to look at snippets of raw data traces with spikes overlaid and rate the overall quality of the recording and spike detection on a scale from 1 to 10, taking into account the apparent noise levels, drift, artifacts, and missed spikes. We found no evidence for systematic quality differences across the datasets (Figure 1—figure supplement 4).

Stereotaxic probe placement limits resolution of probe targeting

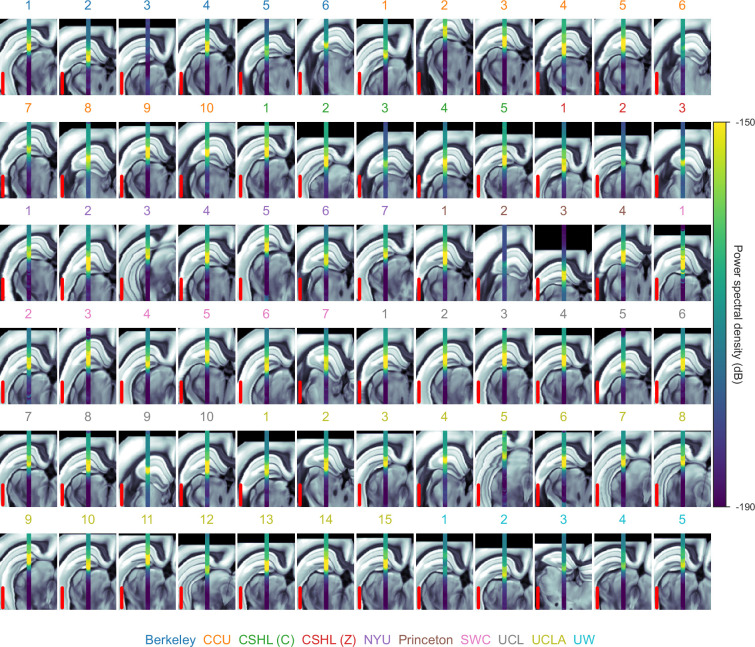

As a first test of experimental reproducibility, we assessed variability in Neuropixels probe placement around the planned repeated site location. Brains were perfusion-fixed, dissected, and imaged using serial section two-photon microscopy for 3D reconstruction of probe trajectories (Figure 2a). Whole brain auto-fluorescence data was aligned to the Allen Common Coordinate Framework (CCF; Wang et al., 2020) using an elastix-based pipeline (Klein et al., 2010) adapted for mouse brain registration (Liu et al., 2021). cm-DiI-labelled probe tracks were manually traced in the 3D volume (Figure 2b; Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Trajectories obtained from our stereotaxic system and traced histology were then compared to the planned trajectory. To measure probe track variability, each traced probe track was linearly interpolated to produce a straight line insertion in CCF space (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Histological reconstruction reveals resolution limit of probe targeting.

(a) Histology pipeline for electrode probe track reconstruction and assessment. Three separate trajectories are defined per probe: planned, micro-manipulator (based on the experimenter’s stereotaxic coordinates), and histology (interpolated from tracks traced in the histology data). (b) Example tilted slices through the histology reconstructions showing the repeated site probe track. Plots show the green auto-fluorescence data used for CCF registration and red cm-DiI signal used to mark the probe track. White dots show the projections of channel positions onto each tilted slice. Scale bar: 1 mm. (c) Histology probe trajectories, interpolated from traced probe tracks, plotted as 2D projections in coronal and sagittal planes, tilted along the repeated site trajectory over the allen CCF, colors: laboratory. Scale bar: 1 mm. (d, e, f) Scatterplots showing variability of probe placement from planned to: micro-manipulator brain surface insertion coordinate (d, targeting variability, N=88), histology brain surface insertion coordinate (e, geometrical variability, N=98), and histology probe angle (f, angle variability, N=99). Each line and point indicates the displacement from the planned geometry for each insertion in anterior-posterior (AP) and mediolateral (ML) planes, color-coded by institution. (g, h, i) Assessment of probe displacement by institution from planned to: micro-manipulator brain surface insertion coordinate (g, N=88), histology brain surface insertion coordinate (h, N=98), and histology probe angle (i, N=99). Kernel density estimate plots (top) are followed by boxplots (bottom) for probe displacement, ordered by descending median value. A minimum of four data points per institution led to their inclusion in the plot and subsequent analysis. Dashed vertical lines display the mean displacement across institutions, indicated in the respective scatterplot in (d, e, f).

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Tilted slices of histology along the probe insertion for all insertions used in assessing probe placement.

We first compared the micro-manipulator brain surface coordinate to the planned trajectory to assess variance due to targeting strategies only (targeting variability, Figure 2d). Targeting variability occurs when experimenters must move probes slightly from the planned location to avoid blood vessels or irregularities. These slight movements of the probes led to sizeable deviations from the planned insertion site (Figure 2d and g, total mean displacement = 104 µm).

Geometrical variability, obtained by calculating the difference between planned and final identified probe position acquired from the reconstructed histology, encompasses targeting variance, anatomical differences, and errors in defining the stereotaxic coordinate system. Geometrical variability was more extensive (Figure 2e and h, total mean displacement = 356.0 µm). Assessing geometrical variability for all probes with permutation testing revealed a p-value of 0.19 across laboratories (Figure 2h), arguing that systematic lab-to-lab differences do not account for the observed variability.

To determine the extent that anatomical differences drive this geometrical variability, we regressed histology-to-planned probe insertion distance at the brain surface against estimates of animal brain size. Regression against both animal body weight and estimated brain volume from histological reconstructions showed no correlation to probe displacement (R2 <0.03), suggesting differences between CCF and mouse brain sizes are not the major cause of variance. An alternative explanation is that geometrical variance in probe placement at the brain surface is driven by inaccuracies in defining the stereotaxic coordinate system, including discrepancies between skull landmarks and the underlying brain structures.

Accurate placement of probes in deeper brain regions is critically dependent on probe angle. We assessed probe angle variability by comparing the final histologically-reconstructed probe angle to the planned trajectory. We observed a consistent mean displacement from the planned angle in both medio-lateral (ML) and anterior-posterior (AP) angles (Figure 2f and i, total mean difference in angle from planned: 7.5 degrees). Angle differences can be explained by the different orientations and geometries of the CCF and the stereotaxic coordinate systems, which we have recently resolved in a corrected atlas (Birman et al., 2023). The difference in histology angle to planned probe placement was assessed with permutation testing across labs and showed a p-value of 0.45 (Figure 2i). This suggests that systematic lab-to-lab differences were minimal.

In conclusion, insertion variance, in particular geometrical variability, is sizeable enough to impact probe targeting to desired brain regions and poses a limit on the resolution of probe targeting. The histological reconstruction, fortunately, does provide an accurate reflection of the true probe trajectory (Liu et al., 2021), which is essential for interpretation of the Neuropixels recording data. We were unable to identify a prescriptive analysis to account for probe placement variance, which may reflect that the major driver of probe placement variance derives from differences in skull landmarks used for establishing the coordinate system and the underlying brain structures. Our data suggest that the resolution of probe insertion targeting on the brain surface to be approximately 360 µm (based on the mean across labs, see Figure 2h), which must be taken into account when planning probe insertions.

Reproducibility of electrophysiological features

Having established that targeting of Neuropixels probes to the desired target location was a source of substantial variability, we next measured the variability and reproducibility of electrophysiological features recorded by the probes. We implemented twelve exclusion criteria. Two of these were specific to our experiments: a behavior criterion where the mouse completed at least 400 trials of the behavioral task, and a session number criterion of at least three sessions per lab for analyses that directly compared across labs (permutation tests; Figures 3d, e, 4g, Figure 5). The remaining 10 criteria, which we collectively refer to as the ‘RIGOR’ (Table 1), are more general and can be applied widely to electrophysiology experiments: a yield criterion, a noise criterion, LFP power criterion, qualitative criteria for visual assessment (lack of drift, epileptiform activity, noisy channels and artifacts, see Figure 1—figure supplement 2 for examples), and single unit metrics (refractory period violation, amplitude cutoff, and median spike amplitude). These metrics could serve as a benchmark for other studies to use when reporting results, acknowledging that a subset of the metrics will be adjusted for measurements made in different animals, regions, or behavioral contexts. The RIGOR metrics, along with additional analysis-specific constraints, determined the number of neurons, mice, and sessions included in subsequent analyses presented here (see spreadsheet).

Figure 3. Electrophysiological features are mostly reproducible across laboratories.

(a) Number of experimental sessions recorded; number of sessions used in analysis due to exclusion criteria. Upper branches: exclusions based on RIGOR criteria (Table 1); lower branches: exclusions based on experiment-specific criteria. For the rest of this figure, an additional targeting criterion was used in which an insertion had to hit two of the target regions to be included. (b) Power spectral density between 20 and 80 Hz of each channel of each probe insertion (vertical columns) shows reproducible alignment of electrophysiological features to histology. Insertions are aligned to the boundary between the dentate gyrus and thalamus. Tildes indicate that the probe continued below –2.0 mm. Location of channels reflect the data after the probes have been adjusted using electrophysiological features CSHL: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory [(C): Churchland lab, (Z): Zador lab], NYU: New York University, SWC: Sainsbury Wellcome Centre, UCL: University College London, UCLA: University of California, Los Angeles, UW: University of Washington. (c) Firing rates of individual neurons according to the depth at which they were recorded. Colored blocks indicate the target brain regions of the repeated site, grey blocks indicate a brain region that was not one of the target regions. If no block is plotted, that part of the brain was not recorded by the probe because it was inserted too deep or too shallow. Each dot is a neuron, colors indicate firing rate. Probes within each institute are sorted according to their distance from the planned repeated site location. (d) p-values for five electrophysiological metrics, computed separately for all target regions, assessing the reproducibility of the distributions over these features across labs. p-values are plotted on a log-scale to visually emphasize values close to significance. (e) A Random Forest classifier could successfully decode the brain region from five electrophysiological features (neuron yield, firing rate, LFP power, AP band RMS and spike amplitude), but could not decode lab identity. The red line indicates the decoding accuracy and the grey violin plots indicate a null distribution obtained by shuffling the labels 500 times. The decoding of lab identity was performed per brain region. (* p<0.05, *** p<0.001).

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Recordings that did not pass QC can be visually assessed as outliers.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. High LFP power in dentate gyrus was used to align probe locations in the brain.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. Bilateral recordings assess within- vs across-animal variance.

Figure 3—figure supplement 4. Values used in the decoding analysis, per metric and per brain region.

Figure 4. Neural activity is modulated during decision-making in five neural structures and is variable between laboratories.

(a) Raster plot (top) and firing rate time course (bottom) of an example neuron in LP, aligned to movement onset, split for correct left and right choices.The firing rate is calculated using a causal sliding window; each time point includes a 60ms window prior to the indicated point. (b) Peri-event time histograms (PETHs) of all LP neurons from a single mouse, aligned to movement onset (only correct choices in response to right-side stimuli are shown). These PETHs are baseline-subtracted by a pre-stimulus baseline. Shaded areas show standard error of mean (and propagated error for the overall mean). The thicker line shows the average over this entire population, colored by the lab from which the recording originates. (c,d) Average PETHs from all neurons of each lab for LP (c) and the remaining four repeated site brain regions (d). Shaded regions indicate one standard error of the mean. (e) Schematic defining all six task-modulation tests (top) and proportion of task-modulated neurons for each mouse in each brain region for an example test (movement initiation) (bottom). Each row within a region correspond to a single lab (colors same as in (d), points are individual sessions). Horizontal lines around vertical marker: SEM around mean across lab sessions. (f) Schematic to describe the power analysis. Two hypothetical distributions: first, when the test is sensitive, a small shift in the distribution is enough to make the test significant (non-significant shifts shown with broken line in grey, significant shift outlined in red). By contrast, when the test is less sensitive, the vertical line is large and a corresponding large range of possible shifts is present. The possible shifts we find usually cover only a small range. (g) Power analysis example for modulation by the stimulus in CA1. Violin plots: distributions of firing rate modulations for each lab; horizontal line: mean across lab; vertical line at right: how much the distribution can shift up- or downwards before the test becomes significant, while holding other labs constant. (h) Permutation test results for task-modulated activity and the Fano Factor. Top: tests based on proportion of modulated neurons (or in the case of Fano Factor, proportion of neurons with a value <1); Bottom: tests based on the distribution of firing rate modulations (or Fano Factor values). Comparisons performed for correct trials with non-zero contrast stimuli. (Figure analyses include collected data that pass our quality metrics and have at least four good units in the specified brain region and three recordings from the specified lab, to ensure that the data from a lab can be considered representative.).

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Proportion of task-modulated neurons, defined by six statistical comparisons, across mice, labs, and brain regions.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Power analysis of permutation tests.

Figure 5. Principal component embedding of trial-averaged activity uncovers differences that are clear region-to-region and more modest lab-to-lab.

(a) PETHs from two example cells (black, fast reaction times only) and 2-PC-based reconstruction (red). Goodness of fit indicated on top with an example of a poor (top) and good (bottom) fit. (b) Histograms of reconstruction goodness of fit across all cells based on reconstruction by 1–3 PCs. Since PETHs are well approximated with just the first 2 PCs, subsequent analyses used the first 2 PCs only. (c) Two-dimensional embedding of PETHs of all cells colored by region (each dot corresponds to a single cell). (d) Mean firing rates of all cells per region, note visible pink/green divide in line with the scatter plot. Error bands are SD across cells normalized by the square root of the number of cells in the region (e) Cumulative distribution of the first embedding dimension (PC1, as shown in (c)) per region with inset of KS statistic, measuring the maximum absolute difference between the cumulative distribution of a region’s first PC values and that of the remaining cells; asterisks indicate significance at p = 0.01. (f) same data as in (c) but colored by lab. Visual inspection does not show lab clusters. (g) Mean activity for each lab, using cells from all regions (color conventions the same as in (f)). Error bands are SD across cells normalized by square root of number of cells in each lab. (h) same as (e) but grouping cells per lab. (i) p-values of all KS tests without sub-sampling; white squares indicate that there were too few cells for the corresponding region/lab pair. The statistic is the KS distance of the distribution of a target subset of cells’ first PCs to that of the remaining cells. Columns: the region to which the test was restricted and each row is the target lab of the test. Bottom row ‘all’: p-values reflecting a region’s KS distance from all other cells. Rightmost column ‘all’: p-values of testing a lab’s KS distance from all other cells. Small p-values indicate that the target subset of cells can be significantly distinguished from the remaining cells. Note that all region-targeting tests are significant while lab-targeting tests are less so. (j) Cell-number-controlled test results; for the same tests as in i the the minimum cell number across compared classes was sampled from the others before the test was computed and p-values combined using Fisher’s method across samplings. Fewer tests are significant after this control. (Figure analyses include collected data that pass our quality metrics and have at least four good units in the specified brain region and three recordings from the specified lab, to ensure that the data from a lab can be considered representative.).

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Lab-grouped average PETH, CDF of the first PC and 2-PC embedding, separate per brain region.

Table 1. Recording Inclusion Guidelines for Optimizing Reproducibility (RIGOR).

These criteria could be applied to other electrophysiology experiments (including those using other probes) to enhance reproducibility. We provide code to apply these metrics to any dataset easily (see Code Availability). Note that whole recording metrics are most relevant to large scale (>20 channel) recordings. For those recordings, manual inspection of datasets passing these criteria will further enhance data quality.

| Criterion | Definition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole recording | Computed | Yield | At least 0.1 neurons (that pass single unit criteria) per electrode channel in each brain region. |

| Noise level | Median action-potential band RMS (AP RMS) less than 40 µV | ||

| LFP derivative | Median of the derivative of the LFP band (20–80 Hz) less than 0.05 dB/µm (may differ for other electrodes). | ||

| Visually assessed | Drift | Drift here refers to the relative movement of brain tissue and electrodes, measured as a function of depth and time. Qualitatively, we look for sharp displacements as a function of time, as observed on the raster plot; severe discontinuity will cause units to artifactually disappear/reappear. Quantitatively, the drift is the cumulative absolute electrode motion estimated during spike sorting (μm). | |

| Epileptiform activity | Absence of epileptiform activity, which is characterized by sharp discontinuities on the raster plot (not driven by movement or noise artifacts) or strong periodic spiking spanning many channels. | ||

| Noisy channels | Absence of noisy or poor impedance channel groups (e.g. lack of visible action potential on the raw data plot). | ||

| Artefacts | Absence of artefacts, which are characterised by a sudden discontinuity in the raw signal, spanning nearly all channels at once. | ||

| Single unit | Computed | Refractory period violation | Each neuron must pass a sliding refractory period metric, a false positive estimate which computes the confidence that a neuron has below 10% contamination for all possible refractory period lengths (from 0.5 to 10ms; see Materials and methods). A neuron passes if the confidence metric is greater than 90% for any possible refractory period length. |

| Amplitude cutoff | Each neuron must pass a metric that estimates the number of spikes missing (false negative rate) and ensures that the distribution of spike amplitudes is not cut off, without a Gaussian assumption. See Materials and methods for description of quantification and thresholds. | ||

| Median spike amplitude | Each neuron must have a median spike amplitude greater than 50 µV. | ||

We recorded a total of 121 sessions targeted at our planned repeated site (Figure 3a). Of these, 18 sessions were excluded due to incomplete data acquisition caused by a hardware failure during the experiment (10) or because we were unable to complete histology on the subject (8). Next, we applied exclusion criteria to the remaining complete datasets. We first applied the RIGOR standards described in Table 1. Upon manual inspection, we observed 1 recording fail due to drift, 10 recordings fail due to a high and unrecoverable count of noisy channels, 2 recordings fail due to artefacts, and 1 recording fail due to epileptiform activity. 1 recording failed our criterion for low yield, and 1 recording failed our criterion for noise level (both automated QC criteria). Next, we applied criteria specific to our behavioral experiments and found that five recordings failed our behavior criterion by not meeting the minimum of 400 trials completed. Some of our analysis also required further (stricter) inclusion criteria (see Materials and methods).

When plotting all recordings, including those that failed to meet QC criteria, one can observe that many discarded sessions were clear outliers (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). In subsequent figures, only recordings that passed these QC criteria were included. Overall, we analyzed data from the 82 remaining sessions recorded in 10 labs to determine the reproducibility of our electrophysiological recordings. The responses of 5312 single neurons (all passing the metrics defined in Table 1) are analyzed below; this total reflects an average of 105 ± 53 [mean ± std] per insertion.

We then evaluated whether electrophysiological features of these neurons, such as firing rates and LFP power, were reproducible across laboratories. In other words, is there consistent variation across laboratories in these features that is larger than expected by chance? We first visualized LFP power, a feature used by experimenters to guide the alignment of the probe position to brain regions, for all the repeated site recordings (Figure 3b). The DG is characterized by high-power spectral density of the LFP (Penttonen et al., 1997; Bragin et al., 1995; Senzai and Buzsáki, 2017), and this feature was used to guide physiology-to-histology alignment of probe positions (Figure 3—figure supplement 2). By plotting the LFP power of all feature aligned recordings along the length of the probe side-by-side, aligned to the boundary between the DG and thalamus, we confirmed that this band of elevated LFP power was visible in all recordings at the same depth. The variability in the extent of the band of elevated LFP power in DG was due to the fact that the DG has variable thickness and due to targeting variability, not every insertion passed through the DG at the same point in the sagittal plane (Figure 3—figure supplement 2).

The probe alignment allowed us to attribute the channels of each probe to their corresponding brain regions to investigate the reproducibility of electrophysiological features for each of the target regions of the repeated site. To visualize all the neuronal data, each neuron was plotted at the depth it was recorded overlaid with the position of the target brain region locations (Figure 3c). From these visualizations, it is apparent that there is recording-to-recording variability. Several trajectories missed their targets in deeper brain regions (LP, PO), as indicated by gray blocks, despite the lack of significant lab-dependent effects in targeting as reported above. These off-target trajectories tended to have both a large displacement from the target insertion coordinates and a probe angle that unfavorably drew the insertions away from thalamic nuclei (Figure 2f). These observations raise two questions: (1) Is the recording-to-recording variability within an animal the same or different compared to across animals? (2) Is the recording-to-recording variability lab dependent?

To answer the first question, we performed several bilateral recordings in which the same insertion was targeted in both hemispheres, as mirror images of one another. This allowed us to quantify the variability between insertions within the same animal and compare this variability to the across-animal variability (Figure 3—figure supplement 3). We found that whether within- or across-animal variance was larger depended on the electrophysiological feature in question (Figure 3—figure supplement 3f). For example, neuronal yield of VISa/am was more variable within subjects than across. By contrast, noise (assessed as action-potential band root mean square, or AP band RMS) was more variable across animals than within. Therefore, variability between metrics of bilateral recordings performed simultaneously did not bear a consistent relationship to the variability observed across subjects.

To test whether recording-to-recording variability is lab dependent, we used a permutation testing approach (Materials and methods). The tested features were neuronal yield, firing rate, spike amplitude, LFP power, and AP band RMS. These were calculated in each brain region (Figure 3—figure supplement 4). As was the case when analysing probe placement variability, the permutation test assesses whether the distribution over features varies significantly across labs. When correcting for multiple tests, we were concerned that systematic corrections (such as a full Bonferroni correction over all tests and regions) might be too lenient and could lead us to overlook failures (or at least threats) to reproducibility. We therefore opted to use a more stringent of 0.01 when establishing significance, and refrained from applying any further corrections (this correction can be thought of as correcting only for the number of regions). The permutation test revealed a significant effect for the spike amplitude in VISa/am. Otherwise, we found that all electrophysiological features were reproducible across laboratories for all regions studied (Figure 3d).

The permutation testing approach evaluated the reproducibility of each electrophysiological feature separately. It could be the case, however, that some combination of these features varied systematically across laboratories. To test whether this was the case, we trained a Random Forest classifier to predict in which lab a recording was made, based on the electrophysiological markers. The decoding was performed separately for each brain region because of their distinct physiological signatures. A null distribution was generated by shuffling the lab labels and decoding again using the shuffled labels (500 iterations). The significance of the classifier was defined as the fraction of times the accuracy of the decoding of the shuffled labels was higher than the original labels. For validation, we first verified that the decoder could successfully identify brain region (instead of lab identity) from the electrophysiological features; the decoder was able to identify brain region with high accuracy (Figure 3e, left). Lab identity could not be decoded using the classifier, indicating that electrophysiology features were reproducible across laboratories for these regions (Figure 3e, right).

Reproducibility of functional activity depends on brain region and analysis method

Concerns about reproducibility extend not only to electrophysiological properties but also to functional properties. To address this, we analyzed the reproducibility of neural activity driven by perceptual decisions about the spatial location of a visual grating stimulus (Aguillon-Rodriguez et al., 2021). In total, we compared the activity of 4400 neurons across all labs and regions. We focused on whether the targeted brain regions have comparable neural responses to stimuli, movements, and rewards. An inspection of individual neurons revealed clear modulation by, for instance, the onset of movement to report a particular choice (Figure 4a). Despite considerable neuron-to-neuron variability (Figure 4b), the temporal dynamics of session-averaged neural activity were similar across labs in some regions (see VISa/am, CA1 and DG in Figure 4d). Elsewhere, the session-averaged neural response was more variable (see LP and PO in Figure 4c and d).

Having observed that many individual neurons are modulated by task variables during decision-making, we examined the reproducibility of the proportion of modulated neurons. Within each brain region, we compared the proportion of neurons that were modulated by stimuli, movements, or rewards (Figure 4e). We used six different comparisons of task-related time windows (using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, Steinmetz et al., 2019) to identify neurons with significantly modulated firing rates to different task aspects (Figure 4e, top and Figure 4—figure supplement 1 specify which time windows we compared for which test on each trial; for this, we use ; since leftwards versus rightwards choices are not paired we use Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to determine modulation for them). For most individual tests, the proportions of modulated neurons across sessions and across brain regions were quite variable (Figure 4e, bottom and Figure 4—figure supplement 1). We also measured the neuronal Fano Factor, which enables the comparison of the fidelity of signals across neurons and regions despite differences in firing rates (Tolhurst et al., 1983). Since the Fano Factor tends to be consistently low around movement time (Churchland et al., 2010; Churchland et al., 2011), we calculated the average Fano Factor per neuron during 40–200ms after movement onset (for correct trials with full-contrast right-side stimuli) and quantified differences across labs.

After determining that our measurements afforded sufficient power to detect differences across labs (Figure 4f, g, Figure 4—figure supplement 2, see Materials and methods), we evaluated reproducibility of these proportions using permutation tests (Figure 4h). (Note that we report the reproducibility of the Fano Factor across labs with some caution due to our power analysis results in Figure 4—figure supplement 2). Our tests uncovered only one region and period for which there were significant differences across labs (, corresponding to a Bonferroni correction for the number of regions but not the number of tests, as described above): VISa/am during the stimulus onset period (Figure 4h, top). In addition to examining the proportion of responsive neurons (a quantity often used to determine that a particular area subserves a particular function), we also compared the full distribution of firing rate modulations. Here, reproducibility was tenuous and failed in thalamic regions for some tests (Figure 4h, bottom). Taken together, these tests uncover that some traditional metrics of neuron modulation are vulnerable to a lack of reproducibility.

These failures in reproducibility were driven by outlier labs; for instance, for movement-driven activity in PO, UCLA reported an average change of 0 spikes/s, while CCU reported a large and consistent change (Figure 4d, right most panel, compare orange vs. yellow traces). Similarly, the differences in modulation in VISa/am were driven by one lab, in which all four mice had a higher percentage of modulated neurons than mice in other labs (Figure 4—figure supplement 1a, purple dots at right) Figure 6.

Figure 6. High-firing and task-modulated LP neurons have slightly different spatial positions and spike waveform features than other LP neurons, possibly contributing only marginally to variability between sessions.

(a) Spatial positions of recorded neurons in LP. Colors: session-averaged firing rates on a log scale. To enable visualization of overlapping data points, small jitter was added to the unit locations.(b) Spatial positions of LP neurons plotted as distance from the planned target center of mass, indicated with the black x. Colors: session-averaged firing rates on a log scale. Larger circles: outlier neurons (above the firing rate threshold of 13.5 sp/s shown on the colorbar). In LP, 114 out of 1337 neurons were outliers. Only histograms of the spatial positions and spike waveform features that were significantly different between the outlier neurons (yellow) and the general population of neurons (blue) are shown (two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons; * and ** indicate corrected p-values of <0.05 and<0.01). Shaded areas: the area between 20th and 80th percentiles of the neurons’ locations. (c) (Left) Histogram of firing rate changes during movement initiation (Figure 4e, Figure 4—figure supplement 1d) for task-modulated (orange) and non-modulated (gray) neurons. 697 out of 1337 LP neurons were modulated during movement initiation. (Right) Spatial positions of task-modulated and non-modulated LP neurons, with histograms of significant features (here, z position) shown. (d) Same as (c) but using the left vs. right movement test (Figure 4e, Figure 4—figure supplement 1f) to identify task-modulated units; histogram is bimodal because both left- and right-preferring neurons are included.292 out of 1337 LP neurons were modulated differently for leftward vs. rightward movements. (Figure analyses include all collected data that pass our quality metrics, regardless of the number of recordings per lab or number of repeated site brain areas that the probes pass through.).

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. High-firing and task-modulated VISa/am neurons.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. High-firing and task-modulated CA1 neurons.

Figure 6—figure supplement 3. High-firing and task-modulated DG and PO neurons.

Figure 6—figure supplement 4. Time-course and spatial position of neuronal Fano Factors.

Figure 6—figure supplement 5. Neuronal subtypes and firing rates.

Looking closely at the individual sessions and neuronal responses, we were unable to find a simple explanation for these outliers: they were not driven by differences in mouse behavior, wheel kinematics when reporting choices, or spatial position of neurons (examined in detail in the next section). This high variability across individual neurons meant that differences that are clear in across-lab aggregate data can be unclear within a single lab. For instance, a difference between the proportion of neurons modulated by movement initiation vs. left/right choices is clear in the aggregate data (compare panels d and f in Figure 4—figure supplement 1), but much less clear in the data from any single lab (e.g. compare values for individual labs in panels d vs. f of Figure 4—figure supplement 1). This is an example of a finding that might fail to reproduce across individual labs, and underscores that single-neuron analyses are susceptible to lack of reproducibility, in part due to the high variability of single neuron responses. Very large sample sizes of neurons could serve to mitigate this problem. We anticipate that the feasibility of even larger scale recordings will make lab-to-lab comparisons easier in future experiments; multi-shank probes could be especially beneficial for cortical recordings, which tend to be the most vulnerable to low cell counts since the cortex is thin and is the most superficial structure in the brain and thus the most vulnerable to damage. Analyses that characterize responses to multiple parameters are another possible solution (See Figure 7).

Figure 7. Brain region, but not lab identity is decodable from single-neuron response profiles.

Results of decoding analysis for different scenarios: (a) brain region decoding using all neurons, (b) lab decoding using all neurons, and (c) lab decoding using neurons from specific brain regions. The histogram shows the distribution of macro-averaged F1 for perturbed null datasets. The null distribution is compared to the macro-averaged F1 of the original dataset (indicated by the dashed red line). The scatter plot shows the cross-validated two-dimensional linear discriminant analysis (LDA) projection. Neurons are randomly and evenly split into two groups: one for training the LDA model and the other for testing. The plots are generated exclusively using the test set.

Having discovered vulnerabilities in the reproducibility of standard single-neuron tests, we tested reproducibility using an alternative approach: comparing low-dimensional summaries of activity across labs and regions. To start, we summarized the response for each neuron by computing peri-event time histograms (PETHs, Figure 5a). Because temporal dynamics may depend on reaction time, we generated separate PETHs for fast () and slow () reaction times ( was the mean reaction time when considering the distribution of reaction times across all sessions). We concatenated the resulting vectors to obtain a more thorough summary of each cell’s average activity during decision-making. The results (below) did not depend strongly on the details of the trial-splitting; for example, splitting trials by ‘left’ vs ‘right’ behavioral choice led to similar results. We further tried a stimulus-aligned pre-movement window, which resulted in many fewer responding cells, although no substantially different test results, not shown here.

Next, we projected these high-dimensional summary vectors into a low-dimensional ‘embedding’ space using principal component analysis (PCA). This embedding captures the variability of the population while still allowing for easy visualization and further analysis. Specifically, we stack each cell’s summary double-PETH vector (described above) into a matrix (containing the summary vectors for all cells across all sessions) and run PCA to obtain a low-rank approximation of this matrix (see Materials and methods). The accuracy of reconstructions from the top two principal components (PCs) varied across cells (Figure 5a); PETHs for the majority of cells could be well-reconstructed with just 2 PCs (Figure 5b).

This simple embedding exposes differences in brain regions (Figure 5c; e.g. PO and DG are segregated in the embedding space), verifying that the approach is sufficiently powerful to detect expected regional differences in response dynamics. Region-to-region differences are also visible in the region-averaged PETHs and cumulative distributions of the first PCs (Figure 5d and e). By contrast, differences are less obvious when coloring the same embedded activity by labs (Figure 5f, g and h); however some labs, such as CCU and CSHL(Z), are somewhat segregated. In comparison to regions, the activity point clouds overlap somewhat more homogeneously across most labs (Figure 5—figure supplement 1 for scatter plots, PETHs, cumulative distributions for each region separately, colored by lab).

We quantified this observation via two tests. First, we applied a permutation test using the first 2 PCs of all cells, computing each region’s 2D distance between its mean embedded activity and the mean across all remaining regions, then comparing these values to the null distribution of values obtained in an identical manner after shuffling the region labels. Second, we directly compared the distributions of the first PCs, applying the Kolmorogov-Smirnov (KS) test to determine whether the distribution of a subset of cells was different from that of all remaining cells, targeting either labs or regions. The KS test results were nearly identical to the 2D distance permutation test results, hence we report only the KS test results below.

This analysis confirmed that the neural activity in each region differs significantly (as defined above, , Bonferroni correction for the number of regions but not the number of tests) from the neural activity measured in the other regions (Figure 5i, bottom row), demonstrating that neural dynamics differ from region-to-region, as expected and as suggested by Figure 5c–e. We also found that the neural activity from 7/10 labs differed significantly from the neural activity of all remaining labs when considering all neurons (Figure 5i, right column). When restricting this test to single regions, significant differences were observed for 6/40 lab-region pairs (Figure 5i, purple squares in the left columns). Note that in panels i,j of Figure 5, the row ‘all’ indicates that all cells were used when testing if a region had a different distribution of first PCs than the remaining regions and analogously the column ‘all’ for lab-targeted tests. We further repeated these tests after controlling for varying cell numbers, by sampling the minimum cell number across compared classes and combining p-values across these samplings using Fisher’s method, which resulted in overall fewer significant differences (Figure 5j). Overall, these observations are in keeping with Figure 4 and suggest, as above, that outlier responses during decision-making can be present despite careful standardization (Figure 5i).

The spatial position within regions and spike waveforms of neurons explain minimal firing rate variability

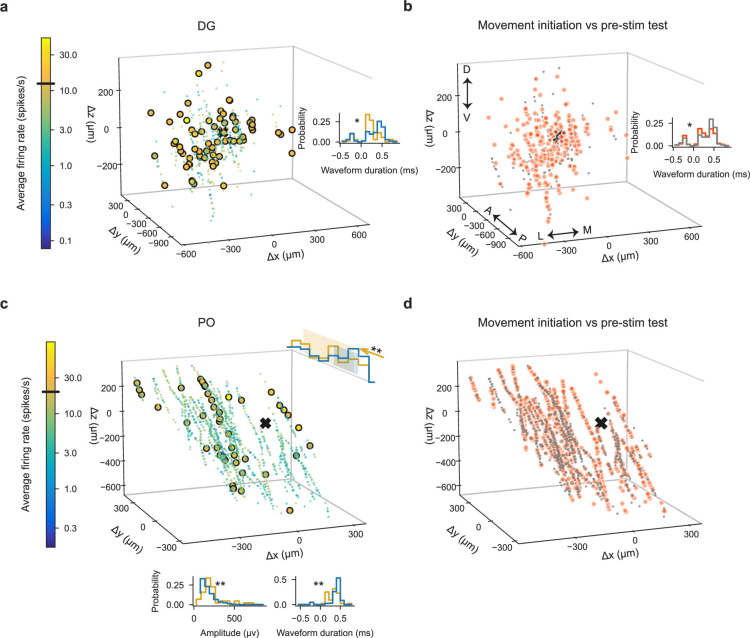

In addition to lab-to-lab variability, which was low for electrophysiological features and higher for functional modulation during decision-making (Figures 4 and 5), we observed considerable variability between recording sessions and mice. Here, we examined whether this variability could be explained by either the within-region location of the Neuropixels probe or the single-unit spike waveform characteristics of the sampled neurons.

To investigate variability in session-averaged firing rates, we identified neurons that had firing rates different from the majority of neurons within each region (absolute deviation from the median firing rate being >15% of the firing rate range). These outlier neurons, which all turned out to be high-firing, were compared against the general population of neurons in terms of five features: spatial position (x, y, z, computed as the center-of-mass of each unit’s spike template on the probe, localized to CCF coordinates in the histology pipeline) and spike waveform characteristics (amplitude, peak-to-trough duration). We observed that recordings in all areas, such as LP (Figure 6a), indeed spanned a wide space within those areas. Interestingly, in areas other than DG, the highest firing neurons were not entirely uniformly distributed in space. For instance, in LP, high firing neurons tended to be positioned more laterally and centered on the anterior-posterior axis (Figure 6b). In VISa/am and CA1, only the spatial position of neurons, but not differences in spike characteristics, contributed to differences in session-averaged firing rates (Figure 6—figure supplements 1b and 2b). In contrast, high-firing neurons in LP, PO, and DG had different spike characteristics compared to other neurons in their respective regions (Figure 6b, Figure 6—figure supplement 3a, c). It does not appear that high-firing neurons in any brain region belong clearly to a specific neuronal subtype (see Figure 6—figure supplement 5).

To quantify variability in session-averaged firing rates of individual neurons that can be explained by spatial position or spike characteristics, we fit a linear regression model with these five features (x, y, z, spike amplitude, and duration of each neuron) as the inputs. For each brain region, features that had significant weights were mostly consistent with the results reported above: In VISa/am and CA1, spatial position explained part of the variance; in DG, the variance could not be explained by either spatial position or spike characteristics; in LP and PO, both spatial position and spike amplitudes explained some of the variance. In LP and PO, where the most amount of variability could be explained by this regression model (having higher values), these five features still only accounted for a total of ∼5% of the firing rate variability. In VISa/am, CA1, and DG, they accounted for approximately 2%, 4%, and 2% of the variability, respectively.

Next, we examined whether neuronal spatial position and spike features contributed to variability in task-modulated activity. We found that brain regions other than DG had minor, yet significant, differences in spatial positions of task-modulated and non-modulated neurons (using the definition of at least of one of the six time-period comparisons in Figure 4c, Figure 4—figure supplement 1). For instance, LP neurons modulated according to the movement initiation test and the left versus right movement test tended to be more ventral (Figure 6c–d). Other brain regions had weaker spatial differences than LP (Figure 6—figure supplements 1–3). Spike characteristics were significantly different between task-modulated and non-modulated neurons only for one modulation test in LP (Figure 6d) and two tests in DG, but not in other brain regions. On the other hand, the task-aligned Fano Factors of neurons did not have any differences in spatial position except for in VISa/am, where lower Fano Factors (<1) tended to be located ventrally (Figure 6—figure supplement 4). Spike characteristics of neurons with lower vs. higher Fano Factors were only slightly different in VISa/am, CA1, and PO. Lastly, we trained a linear regression model to predict the 2D embedding of PETHs of each cell shown in Figure 5c from the x, y, z coordinates and found that spatial position contains little information () about the embedded PETHs of cells.

In summary, our results suggest that neither spatial position within a region nor waveform characteristics account for very much variability in neural activity. We examine other sources of variability below (see section, A multi-task neural network accurately predicts activity and quantifies sources of neural variability).

Single neuron coefficients from a regression-based analysis are reproducible across labs

Neural encoding models provide a natural way to quantify the impact of many variables on single neuron activity, and to test whether the resulting profiles are reproducible across labs or brain regions. We first estimated single-neuron response profiles using standard linear regression models. Second, we evaluated reproducibility by decoding either lab identity or brain region from the response profiles of each neuron.

We used a Reduced-Rank Regression (RRR) encoding model to predict the single neuron activity as a function of the experimental conditions and the subject’s behavior. Our approach follows a previous application of the RRR model to cortical neurons in the IBL Brainwide Map dataset (Posani et al., 2025). Specifically, the input variables we used for fitting the model range from cognitive (left vs. right block), sensory (stimulus side, contrast), motor (wheel velocity, whisker motion energy, lick), to decision-related (choice, outcome). The goal of the model is to relate these variables to the measured neural activity (aligned to stimulus onset, smoothed, and normalized). After fitting the RRR model to predict trial-by-trial activity, each neuron is summarized by a single 32-dimensional coefficient vector.

Using these 32-dimensional vectors, we then attempted to decode the region or lab identity associated with the neurons. We used 69 sessions from the dataset presented here. Neurons from the regions VISa, DG, PO, CA1, LP, passing the QC (RIGOR), and with sufficient goodness-of-fit (cross-validated ) were included in the decoding analysis. There were 1767 responsive neurons in total. We used the support vector classification (SVC) for the multi-class classification and the macro-averaged F1 score to assess the goodness of decoding. Additionally, we conducted a permutation test (Materials and methods, N_permute = 1000) to determine whether the macro-averaged F1 score obtained from the data was significantly higher than chance level.

We found that the region identity was more decodable than the lab identity. The macro-averaged F1 score for the region decoding was 0.35 (p<0.0001, Figure 7a), while for lab decoding, it was only 0.14 (p=0.325, Figure 7b). To ensure that the unequal distribution of recorded regions did not cause us to mis-estimate the lab decoding performance, we applied the same lab decoding analysis to each region separately. The results are close to chance level for all the regions (p=0.166, 0.048, 0.147, 0.124 0.599 for VISa, CA1, DG, LP, and PO respectively, Figure 7c). The results align with our visual inspection using linear discriminant analysis (Figure 7, bottom row), where region-to-region differences are more visible than lab-to-lab differences. In summary, the identity of the brain region is significantly decodable from the single-neuron response profiles, while the identity of the laboratory is not. This speaks to the reproducibility of single neuron metrics across labs, and provides reassurance that when a neuron’s full response profile is considered (instead of its selectivity for just one variable as in Figure 4), results are more robust.

A multi-task neural network accurately predicts activity and quantifies sources of neural variability

As discussed above, variability in neural activity between labs or between sessions can be due to many factors. These include differences in behavior between animals, differences in probe placement between sessions, and uncontrolled differences in experimental setups between labs. Simple linear regression models or generalized linear models (GLMs) may be too inflexible to capture the nonlinear contributions that many of these variables, including lab identity and spatial positions of neurons, might make to neural activity. On the other hand, fitting a different nonlinear regression model (involving many covariates) individually to each recorded neuron would be computationally expensive and could lead to poor predictive performance due to overfitting.

To estimate a flexible nonlinear model given constraints on available data and computation time, we adapt an approach that has proven useful in the context of sensory neuroscience (McIntosh et al., 2016; Batty et al., 2016; Cadena et al., 2019). We use a ‘multi-task’ neural network (MTNN; Figure 8a) that takes as input a set of covariates (including the lab ID, the neuron’s 3D spatial position in standardized CCF coordinates, the animal’s estimated pose extracted from behavioral video monitoring, feedback times, and others; see Table 2 for a full list). The model learns a set of nonlinear features (shared over all recorded neurons) and fits a Poisson regression model on this shared feature space for each neuron. With this approach we effectively solve multiple nonlinear regression tasks simultaneously; hence the ‘multi-task’ nomenclature. The model extends simpler regression approaches by allowing nonlinear interactions between covariates. In particular, previous reduced-rank regression approaches (Izenman, 1975; Kobak et al., 2016; Steinmetz et al., 2019; Posani et al., 2025), including the analysis presented here (Figure 7), can be seen as a special case of the multi-task neural network, with a single hidden layer and no nonlinearity between layers.

Figure 8. Single-covariate, leave-one-out, and leave-group-out analyses show the contribution of each (group of) covariate(s) to the MTNN model.

Lab and session IDs have low contributions to the model. (a) We adapt a MTNN approach for neuron-specific firing rate prediction. The model takes in a set of covariates and outputs time-varying firing rates for each neuron for each trial. See Table 2 for a full list of covariates. (b) MTNN model estimates of firing rates (50ms bin size) of a neuron in VISa/am from an example subject during held-out test trials. The trials with stimulus on the left are shown and are aligned to the first movement onset time (vertical dashed lines). We plot the observed and predicted PETHs and raster plots. The blue ticks in the raster plots indicate stimulus onset, and the green ticks indicate feedback times. The trials above (below) the black horizontal dashed line are incorrect (correct) trials, and the trials are ordered by reaction time. The trained model does well in predicting the (normalized) firing rates. The MTNN prediction quality measured in is 0.45 on held-out test trials and 0.94 on PETHs of held-out test trials. (c) We plot the MTNN firing rate predictions along with the raster plots of behavioral covariates, ordering the trials in the same manner as in (b). We see that the MTNN firing rate predictions are modulated synchronously with several behavioral covariates, such as wheel velocity and paw speed. (d) Single-covariate analysis, colored by the brain region. Each dot corresponds to a single neuron in each plot. (e) Leave-one-out and leave-group-out analyses, colored by the brain region. The analyses are run on 1133 responsive neurons across 32 sessions. The leave-one-out analysis shows that lab/session IDs have low effect sizes on average, indicating that within and between-lab random effects are small and comparable. The ‘noise’ covariate is a dynamic covariate (white noise randomly sampled from a Gaussian distribution) and is included as a negative control: the model correctly assigns zero effect size to this covariate. Covariates that are constant across trials (e.g., lab and session IDs, neuron’s 3D spatial location) are left out from the single-covariate analysis.

Figure 8—figure supplement 1. MTNN prediction quality; MTNN slightly outperforms GLMs on predicting the firing rates of held-out test trials; PETHs and MTNN predictions for held-out test trials.

Figure 8—figure supplement 2. MTNN prediction quality on the data simulated from GLMs is comparable to the GLMs’ prediction quality.

Figure 8—figure supplement 3. Lab IDs have a negligible effect on the MTNN prediction.

Figure 8—figure supplement 4. MTNN single-covariate effect sizes are highly correlated across sessions and labs.

Table 2. List of covariates input to the multi-task neural network.

| Covariate Name | Type | Group | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lab ID | Categorical / Static | ||

| Session ID | Categorical / Static | ||

| Neuron 3D spatial position | Real / Static | Electrophysiological | In standardized CCF coordinates |

| Neuron amplitude | Real / Static | Electrophysiological | Template amplitude |

| Neuron waveform width | Real / Static | Electrophysiological | Template width |

| Paw speed | Real / Dynamic | Movement | Inferred from Lightning Pose |

| Nose speed | Real / Dynamic | Movement | Inferred from DLC |

| Pupil diameter | Real / Dynamic | Movement | Inferred from Lightning Pose |

| Motion energy | Real / Dynamic | Movement | |

| Stimulus | Real / Dynamic | Task-related | Stimulus side, contrast and onset timing |

| Go cue | Binary / Dynamic | Task-related | |

| First movement | Binary / Dynamic | Task-related | |

| Choice | Binary / Dynamic | Task-related | |

| Feedback | Binary / Dynamic | Task-related | |

| Wheel velocity | Real / Dynamic | Movement | |

| Mouse Prior | Real / Static | Mouse’s prior belief | |

| Last Mouse Prior | Real / Static | Mouse’s prior belief in previous trial | |

| Lick | Binary / Dynamic | Movement | Inferred from DLC |

| Decision Strategy | Real / Static | Decision-making strategy Ashwood et al., 2021 | |

| Brain region | Categorical / Static | Electrophysiological | 5 repeated site regions |

Figure 8b shows model predictions on held-out trials for a single neuron in VISa/am. We plot the observed and predicted peri-event time histograms and raster plots for left trials. As a visual overview of which behavioral covariates are correlated with the MTNN prediction of this neuron’s activity on each trial, the predicted raster plot and various behavioral covariates that are input into the MTNN are shown in Figure 8c. Overall, the MTNN approach accurately predicts the observed firing rates. When the MTNN and GLMs are trained on movement, task-related, and prior covariates, the MTNN slightly outperforms the GLMs on predicting the firing rate of held-out test trials (See Figure 8—figure supplement 1b). On the other hand, as shown in Posani et al., 2025, reduced-rank regression models can achieve similar predictive performance as the MTNN.

Next we use the predictive model performance to quantify the contribution of each covariate to the fraction of variance explained by the model. Following Musall et al., 2019, we run two complementary analyses to quantify these effect sizes: single-covariate fits, in which we fit the model using just one of the covariates, and leave-one-out fits, in which we train the model with one of the covariates left out and compare the predictive explained to that of the full model. As an extension of the leave-one-out analysis, we run the leave-group-out analysis, in which we quantify the contribution of each group of covariates (electrophysiological, task-related, and movement) to the model performance. Using data simulated from GLMs, we first validate that the MTNN leave-one-out analysis is able to partition and explain different sources of neural variability (See Figure 8—figure supplement 2).

We then run single-covariate, leave-one-out, and leave-group-out analyses to quantify the contributions of the covariates listed in Table 2 to the predictive performance of the model on held-out test trials. The results are summarized in Figure 8d and e, with a simulated positive control analysis in Figure 8—figure supplement 3. According to the single-covariate analysis (Figure 8d), face motion energy (derived from behavioral video), paw speed, wheel velocity, and first movement onset timing can individually explain about 5% of variance of the neurons on average, and these single-covariate effect sizes are highly correlated (Figure 8—figure supplement 4).

The leave-one-out analysis (Figure 8e left) shows that most covariates have low unique contribution to the predictive power. This is because many covariates are correlated and are capable of capturing variance in the neural activity even if one of the covariates is dropped (See behavioral raster plots in Figure 8c). According to the leave-group-out analysis (Figure 8e right), the ‘movement’ covariates as a group have the highest unique contribution to the model’s performance while the task-related and electrophysiological variables have close-to-zero unique contribution. Most importantly, the leave-one-out analysis shows that lab and session IDs, conditioning on the covariates listed in Table 2, have close to zero effect sizes, indicating that within-lab and between-lab random effects are small and comparable.

Decodability of task variables is consistent across labs, but varies by brain region

The previous sections addressed whether task modulation of neural activity is consistent across labs from an encoding perspective. In this section, we explored the consistency in population-level representation of task variables across labs from a decoding perspective. The analysis consists of two parts: first, we decoded selected task variables—choice, stimulus side, reward, and wheel speed—using population activity from five brain regions (PO, LP, DG, CA1, and VISa/am) across individual probe insertions. Second, we conducted statistical tests to determine whether the decodability of task variables is comparable across labs.

We used the multi-animal, across-region reduced-rank decoder introduced in Zhang et al., 2024. We performed fivefold cross-validation and adjusted for chance-level decoding scores for each task variable. For choice, stimulus side, and reward, we calculated chance-level accuracy by decoding based on the majority class in the training data and then subtracting this from the observed accuracy. For wheel speed, we report the single-trial , which measures prediction quality by first calculating the trial-average behavior across choice, stimulus side, and reward conditions, and then subtracting these averages from the observed behavior. This approach adjusts for chance-level decoding by implicitly assuming that the condition-specific trial averages can serve as the chance-level prediction.

Given the decoding scores over chance level, we performed statistical tests to assess the consistency of task variable decodability across labs and regions. To assess whether there are significant differences in mean decoding scores across different labs, we performed a one-way ANOVA test Figure 9a; the adjusted significance level is 0.01 after multiple-comparison correction. No statistically significant differences in decoding scores were apparent for any region or variable. This suggests that the decodability of task variables from populations is generally comparable across different labs. We then evaluated task-specific decoding performance categorized by region and lab, accounting for the number of neurons (Figure 9b). No clustering of decoding scores based on lab identities was apparent. We then performed a quantitative test by decoding lab and region identity using both decoding scores and the number of units as covariates. We conducted a permutation test with 5000 permutations and used a support vector classifier (again with an adjusted significance level of 0.01 after multiple-comparison correction). We could accurately determine region identity based on decoding scores and unit counts, as evidenced by macro F1 scores that exceed chance levels and significant p-values. In contrast, lab identity is less decodable than region identity, with F1 scores near chance. This implies that, after accounting for the number of neurons, the decodability of task variables from populations remains comparable across different labs.

Figure 9. The decodability of task variables from the population is consistent across labs, but varies by brain region.

(a) Task-specific decoding performance per region with per session results. The decoding scores over chance level for choice, stimulus side, and reward represent decoding accuracy, while the score for wheel speed is measured in units. Each dot indicates the decoding performance for a single insertion, color-coded by lab identity. A one-way ANOVA is conducted to determine if there are significant differences in mean decoding scores across labs. The F-statistic and p-value are reported. After multi-comparison correction, the reported p-values reveal no statistically significant differences in decoding scores across labs. (b) The scatter plot shows the decoding score over chance level plotted against the number of neurons used. Each dot represents a single insertion, color-coded by the region (top) and lab (bottom) identity. The scores for choice, stimulus side, and reward represent decoding accuracy, while the score for wheel speed is measured in units. We conduct a quantitative test of the decodability of lab and region identity using decoding scores and the number of units as covariates. A support vector classifier is used, and a permutation test with 5000 permutations is applied. We report the macro F1 scores and p-values from the permutation test. After multiple-comparison correction, lab identity is less decodable than region identity, and its observed decodability may occur by chance.

Discussion

We set out to test whether the results from an electrophysiology experiment could be reproduced across 10 geographically separated laboratories. We observed notable variability in the position of the electrodes in the brain despite efforts to target the same location (Figure 2). Fortunately, after applying stringent quality-control criteria (including the RIGOR standards, Table 1), we found that electrophysiological features such as neuronal yield, firing rate, and LFP power were reproducible across laboratories (Figure 3d). The proportion of neurons with responses that were modulated, and the ways in which they were modulated by individual, behaviorally relevant task events was more variable: lab-to-lab differences were evident in some regions (Figures 4 and 5) and these were not explainable by, for instance, systematic variation in the subregions that were targeted (Figure 6). Reassuringly, analyses that summarized each neuron’s activity by a compact vector of features were more robust (Figure 7). Further, when we trained a multi-task neural network to predict neural activity, lab identity accounted for little neural variance (Figure 8), arguing that the lab-to-lab differences we observed are driven by outlier neurons/sessions and nonlinear interactions between variables, rather than, for instance, systematic biases. A decoding analysis likewise confirmed reproducibility of neural activity across labs (Figure 9). This is reassuring, and points to the need for appropriate analytical choices to ensure reproducibility. Altogether, our results suggest that standardization and QC metrics can enhance reproducibility, and that caution should be taken with regard to electrode placement and the interpretation of some standard single-neuron metrics.

The absence of systematic differences across labs for some metrics argues that standardization of procedures is a helpful step in generating reproducible results. Our experimental design precludes an analysis of whether the reproducibility we observed was driven by person-to-person standardization or lab-to-lab standardization. Most likely, both factors contributed: all lab personnel received standardized instructions for how to implant head bars and train animals, which likely reduced personnel-driven differences. In addition, our use of standardized instrumentation and software minimized lab-to-lab differences that might normally be present. Another significant limitation of the analysis presented here is that we have not been able to assess the extent to which other choices of quality metrics and inclusion criteria might have led to greater or lesser reproducibility.

Reproducibility in our electrophysiology studies was further enhanced by rigorous QC metrics that ultimately led us to exclude a significant fraction of datasets (retaining 82 / 121 experimental sessions). QC was enforced for diverse aspects of the experiments, including histology, behavior, targeting, neuronal yield, and the total number of completed sessions. A number of recordings with high noise and/or low neuronal yield were excluded. Exclusions were driven by artifacts present in the recordings, inadequate grounding, and a decline in craniotomy health; all of these can potentially be improved with experimenter experience (a metric that could be systematically examined in future work). A few QC metrics were specific to our experiments (and thus not listed in Table 1). For instance, we excluded sessions with fewer than 400 trials, which could be too stringent (or not stringent enough) for other experiments.