Abstract

This study examines the mediating role of financial well-being in the relationship between housing affordability and mental health across the European Union. Utilizing data from the 2018 EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, the analysis incorporates both objective and subjective measures of housing affordability and financial well-being. The findings reveal that financial well-being acts as a mechanism that links housing pressure to mental health, proxied by the MHI-5 Mental Health Inventory. Notably, the effect is stronger for subjective indicators, which exhibit a more pronounced mediating effect than do objective financial well-being indicators. The results underscore the importance of considering both objective and subjective dimensions in understanding the complex interplay between housing affordability, financial well-being, and mental health. The study contributes to the literature by providing insights into the underlying mechanisms through which housing affordability impacts mental health, with implications for policy interventions aimed at alleviating the negative impacts of housing affordability issues on mental health and overall well-being.

Keywords: Housing affordability, Financial well-being, Mental health, EU-SILC

Subject terms: Psychology, Quality of life

Introduction

Housing typically represents the largest share of total household expenditures, averaging somewhat above 30% of household budgets across the European Union. Housing affordability has become an increasingly pressing issue in the context of rising living costs and growing socio-economic inequalities. Conventional, objective measures of housing affordability are predicated on the notion that housing costs should not burden the non-housing consumption of the household1, and are typically quantified as the proportion of income spent on housing. The generally accepted rule of thumb is that housing costs should not exceed 25–30% of a household’s income2. However, there is no consensus on the appropriate threshold3, with percentages applied in the literature ranging from 25 to 50%4.

Because research on housing affordability predominantly relies on traditional objective indicators, studies may not accurately capture the full experience of financial stress or its impacts on a household’s quality of life5,6. An alternative approach is to measure perceived affordability7, also known as subjective housing affordability. This typically involves data on households’ self-reported financial burden levels based on their perceptions of their housing costs8. However, empirical research has demonstrated discrepancies between objective and subjective measures9, and indicates some degree of misalignment between the two approaches10. While some researchers remain sceptical of subjective indicators11,12, they are increasingly recognized as essential for capturing the complex nature of quality of life13–15. Subjective indicators have been identified as missing dimensions in quality-of-life research16. Importantly, individuals’ subjective perceptions of socio-economic reality may have a stronger influence on their preferences, decisions, and behaviors than do objective socio-economic conditions17,18.

Research indicates that a heavy burden of housing costs can exacerbate economic hardship19, significantly reduce a households’ ability to allocate resources, and ultimately compromise overall living standards20. Housing is generally regarded as a critical socio-economic determinant of mental21, and overall health22,23. For instance, homeownership can enhance individuals’ subjective well-being by providing an avenue for wealth accumulation24, whereas paying rents that are high relative to household income adversely affects mental health25. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the importance of examining the impact of housing affordability on mental health, as it has intensified unemployment, economic distress, and insecurity related to homeownership26,27.

Substantial empirical evidence indicates a robust association between poor housing affordability and adverse mental health outcomes28. Empirical studies have documented that both prolonged and intermittent exposure to housing affordability challenges is correlated with diminished mental health29. Notably, a systematic review conducted by Singh et al.30 provides causal evidence on the impacts of housing disadvantage on mental health. Their findings highlight that housing is a critical socio-economic determinant of mental health, and present evidence of the detrimental effects of housing cost disadvantage on depression, anxiety, and stress. Conversely, affordable housing has been demonstrated to enhance mental health31.

Limited attention has been paid to the mechanisms through which the relationship between housing affordability and mental health operate32. Singh et al.30 show that the negative effects of unaffordable housing on mental health are mediated by financial difficulties. Botha et al.33 extend their model and show that housing stress directly influences financial well-being, which can exacerbate its effects on mental health. Their findings reveal that housing affordability stress is directly associated with lower financial well-being, while strong financial well-being can obviate this stress, and potentially reduce the adverse effects of housing affordability stress on mental health.

Financial well-being, proxied by variables such as perceptions of the degree of financial stress versus financial stability, significantly influences individual well-being34. These factors play a particularly crucial role during crises. For example, financially resilient households managed the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic more successfully35, while those experiencing financial distress reported worsened health outcomes. The pandemic also triggered shifts in household behavior, driving increased risk aversion36 and greater reliance on digital finance which sometimes resulted in over-indebtedness37.

The profound impact of financial well-being on health and mental well-being becomes even more evident when its specific components, such as financial stress and debt, are considered. For instance, the perception of financial insecurity exacerbates stress33, while financial stress and concerns have been shown to have a significant negative impact on individuals’ health and mental well-being38. Those in financial distress report poorer health outcomes39, which underscores the detrimental effects of financial stress on health. Research further suggests that financial stress, including debt, can contribute to symptoms of depression40. Poor mental health, in turn, negatively affects individuals’ social and economic circumstances, being associated with higher unemployment rates and labor market withdrawal41.

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to understanding the relationships between housing stress and financial well-being. The link between housing affordability and financial well-being is rooted in the interplay between economic pressures and psychological perceptions. Rising housing costs directly reduce disposable income and can constrain a households’ ability to save, invest, or even to fulfill essential needs19. Recent studies have shown that financial well-being not only reflects material conditions but also acts as a protective factor that buffers households from the adverse effects of economic shocks35.

Rowley et al.42 show that households classified as experiencing housing stress display lower levels of financial well-being. In a similar vein, Botha et al.33 find that renters experiencing housing affordability stress report, on average, a 2.5-point lower financial well-being score than those not affected by housing affordability stress. Further evidence43 indicates that, while not all households in housing stress are financially distressed, these households are more inclined to rate themselves as “just getting along”, “poor”, or “very poor”. In contrast, non-stressed households tend to consider themselves “reasonably comfortable “.

When looking over longer periods of time, the relationship between housing affordability and financial well-being may be different. Focusing on households that experience stress for three or more years significantly strengthens the observed link between housing stress and (lower) financial well-being44. Such households often cannot adequately adapt to changing circumstances, and ultimately face more severe financial challenges. Difficulty making housing payments has been identified as a negative predictor of financial well-being45.

The conceptual model introduced by Singh et al.30 posits financial hardship as a mediator in the relationship between housing affordability and mental health. Botha et al.33 utilize a specific set of five items to measure subjective financial well-being, such as enjoying life due to money management, handling unexpected expenses, and feeling in control of day-to-day finances. The literature often explores financial satisfaction as a dimension of financial well-being, which can be impacted by housing affordability issues46. Housing affordability problems have been shown to deteriorate overall financial well-being47, with evidence linking various dimensions of financial well-being—such as self-reported financial deprivation48, perceived financial security49, and financial satisfaction50—to adverse effects on mental health.

Existing research examining the mediating effects of financial well-being on the relationship between unaffordable housing and mental health typically relies on objective measures of housing affordability and subjective indicators of financial well-being30,33. Our study advances this stream of literature by jointly investigating the mediating effects of both objective and subjective indicators of financial well-being, by simultaneously incorporating both objective and subjective operationalizations of unaffordable housing in the analysis. This aligns with recent calls for multidimensional approaches that integrate subjective perceptions of socio-economic reality alongside objective conditions. Analyzing these mediation effects is critical for identifying the mechanisms through which housing affordability impacts mental health. This analysis is particularly relevant for social policy, as interventions targeting objective factors, such as housing costs or debt issues, differ from those addressing subjective factors, such as perceived financial hardship or satisfaction with financial circumstances. Understanding which indicators better explain the overall impact of housing affordability on mental health can guide the development of interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of housing unaffordability on mental health. A comprehensive approach ensures that policies address both the symptoms and root causes of mental health issues linked to housing unaffordability.

Additionally, this study seeks to expand the existing empirical literature by providing international evidence on the mediating effect of financial well-being in the relationship between housing affordability and mental health. We draw on data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), which is representative of the countries included in the survey.

Conceptual framework

Financial hardship plays a central role in societal contributors to disease, as it can result in trade-offs that may harm health, for example, by reducing access to medical care30. Building on the framework proposed by Singh et al.30, this study adds to traditional measurements of objective housing affordability and emphasizes the need for the inclusion of subjective indicators in studying these relationships.

Singh et al.30 propose a conceptual framework that links the adverse impact of unaffordable housing (an objective indicator) on mental health, mediated by financial hardship (a subjective indicator), and the degree of social support available. This model explains how unaffordable housing affects mental health, highlighting the central roles of financial strain and social support. By linking high housing costs to increased financial insecurity, the framework suggests that housing stress can negatively affect mental well-being. To capture these effects, their empirical exercise uses participants’ own perceptions of their economic circumstances as a subjective measure of financial strain (vs. financial well-being). In doing so, it presents a comprehensive model that clarifies the complex relationships among housing affordability, financial challenges, social support, and overall mental health. Botha et al.33 introduce a similar model, omit social support and expand the construct of financial hardship to encompass financial well-being.

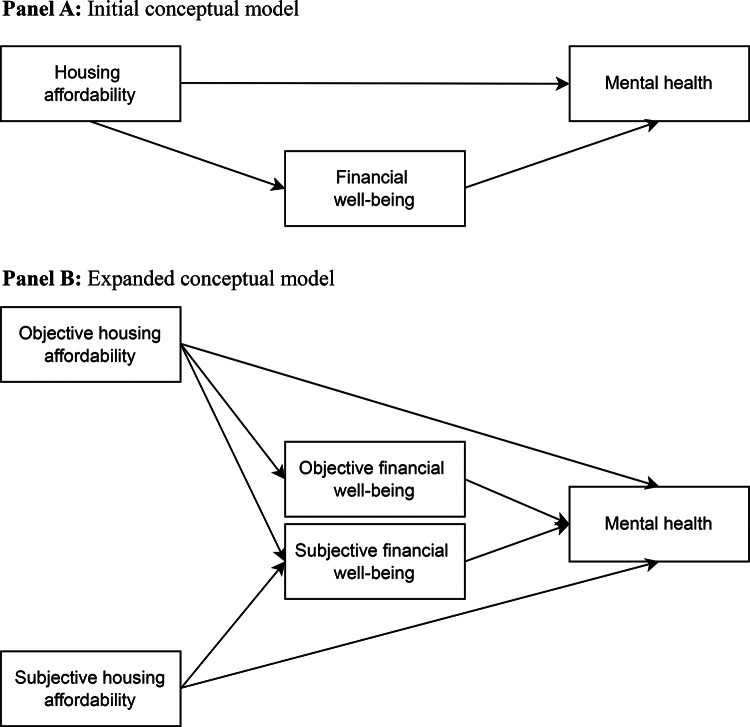

Both Singh et al.30 and Botha et al.33 utilize an objective indicator of housing affordability and subjective indicators of financial well-being. Building upon this literature, our proposed conceptual framework introduces several modifications. First, we extend the initial conceptual model (Panel A of Fig. 1) based on Singh et al.30 and Botha et al.33 by utilizing both objective and subjective approaches to assess housing affordability and to examine their impact on mental health, mediated through objective and subjective indicators of financial well-being (Panel B of Fig. 1). Following Botha et al.33, we omit the social support variable and augment the financial wellbeing construct by including an objective dimension.

Fig. 1.

The conceptual framework. Panel A displays a path diagram corresponding to the initial conceptual model based on Singh et al.30 and Botha et al.33, where financial well-being is the only mediating variable in the relationship between housing affordability and mental health. In Panel B, both objective and subjective financial well-being indicators mediate the relationships between objective and subjective housing affordability and mental health.

We investigate this relationship through a series of steps. We first explore the mediating effect of objective and subjective financial well-being separately in partial models. Subsequently, we analyze these associations within an expanded model that incorporates all variables concurrently. Comparing these sets of results enhances our understanding of the importance of both the objective and subjective dimensions of financial well-being in explaining the relationship between housing affordability and mental health. Our model specifications consistently support the hypothesis that financial well-being acts as a mechanism that links housing affordability to mental health.

Data and methods

The analyses in this study are based on microdata from the 2018 EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (Cross UDB, 2020–09 version). The EU-SILC is a harmonized survey that collects data on income, living conditions, and social exclusion across the EU and other European countries. According to the EU-SILC Framework Regulation, data are based on a nationally representative probability sample of the population residing in private households within the country, irrespective of language, nationality, or legal residence status. All private households and all persons aged 16 and over within the household are eligible for the study. Persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded from the target population. The sampling frame and methods of sample selection should ensure that every individual and household in the target population is assigned a known probability of selection that is not zero51. The study utilizes a subsample of respondents from whom household-level information is obtained.

The outcome variable, mental health (MH), is based on the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5), which measures a respondent’s general mood or affect, including depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being52, and is used for screening depressive symptoms53, with a score of 56 or lower (out of 100) indicating serious problems. Within the EU-SILC 2018 ad hoc module, respondents answer the following set of five questions: “During the last four weeks, have you been… 1. feeling very nervous? 2. feeling down in the dumps? 3. feeling calm and peaceful? 4. feeling downhearted or depressed? 5. happy?” For each question, respondents chose one answer: all of the time; most of the time; some of the time; a little of the time; none of the time; (do not know).

In line with Zhan et al. 202254, we utilize two different operationalizations of housing affordability (HA), the explanatory variable in our conceptual framework. The objective HA is an indicator variable with a value of 1 if the household’s income spent on housing exceeds 30% and 0 otherwise. We perform a robustness check utilizing the threshold adopted by the EU, where the housing cost overburden rate is defined as the share of the population living in a household where total housing costs represent more than 40% of disposable household income. The subjective HA indicator is based on the following survey question: “Please consider your total housing costs, including mortgage repayment (instalment and interest) or rent, insurance, and service charges (sewage removal, garbage removal, regular maintenance, repairs, and other charges). To what extent are these costs a financial burden to you? Please note: Only actual paid housing costs have to be taken into account. Would you say they are: a) A heavy burden; b) A slight burden; c) Not a burden at all.” We assign the subjective HA a value of 1 if the respondent selected ‘a heavy burden’ or ‘a slight burden’, and 0 otherwise.

Drawing from existing literature45,55, we adopt objective and subjective operationalizations of financial well-being (FWB), the mediating variable in the relationship between housing affordability and mental health. The objective operationalization is represented by two variables indicating whether a household was in arrears on 1. hire purchase instalments or other loan payments, and/or 2. utility bills. The subjective operationalization is proxied by three subjective variables: 1. Capacity to afford a one-week annual holiday away from home; 2. Capacity to handle unexpected financial expenses; and 3. Capacity to spend a small amount of money each week on yourself.

We include the following set of control variables in the model: age, gender, degree of urbanization of residence, education, marital status, income, household size, economic activity, and housing tenure status. Detailed descriptions of all variables are available in Table S1 of the Supplementary Material.

We employ structural equation modelling (SEM) as our primary method for empirical analysis of the conceptual framework illustrated in Fig. 1. Specifically, we use partial least squares (PLS)56 with SmartPLS software57. The PLS-SEM method is widely employed in exploratory research and has been acknowledged as a second-generation approach that is adept at handling measurement errors, modelling complex structures, and accommodating non-normal data distributions58. We measure all constructs in the model with reflective indicators, except for objective and subjective FWB, which are modelled as formative constructs.

Formative measurement models are predicated on the premise that the indicators contribute to the construct through linear combinations59,60. In contrast to reflective indicators, which are viewed as manifestations of the latent construct61, formative indicators posit that each indicator linked to a specific construct will have an effect on that construct62. Hence, the directionality of the relationship flows from the indicator towards the construct61. Within a formative measurement model, it is not necessary for the indicators to exhibit high correlations with one another. Furthermore, it is crucial to highlight that formative indicators are not interchangeable, in contrast to reflective indicators62. Consequently, we consider each indicator to encapsulate a distinct aspect of a construct, and removing any single indicator would alter the conceptual scope of the construct.

Model accuracy metrics (AIC, BIC, coefficient of determination, discriminant validity), formative measurement model metrics (collinearity and statistical significance & relevance of outer weights), and convergent validity (average variance extracted, outer loadings) of the latent variables for the model specifications are documented in Tables S7-S11 of the Supplementary Material for all countries.

Results

Measurement model analysis

In this study, we measure mental health using reflective indicators. This subsection presents our evaluation of the reflective measurement model, including assessments of (i) indicator loadings, (ii) internal consistency reliability (via Cronbach’s Alpha, Rho A, and Composite Reliability), and (iii) convergent validity (via Average Variance Extracted (AVE))63,64.

As shown in Table S7 in the Supplementary Material, most indicators, except for the “calm” and “nervous” indicators, exhibit outer loadings above the threshold of 0.708, indicating that the construct explains more than 50% of the variance in these indicators65. However, Hair et al.66 suggest that outer loadings of 0.6 or higher are still acceptable and should not be dropped. Therefore, we retain indicators with outer loadings exceeding 0.60 but below 0.70 due to their conceptual importance in explaining the construct. We find exceptions in the case of Poland, where the “calm” indicator has an outer loading of 0.567, and in Lithuania the construct of the “nervous” indicator is 0.303, and 0.378 in Latvia. Hair et al.58 note that indicator loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 can be retained if they are conceptually important for their respective constructs.

We employ the Rho A measure67 to assess the internal consistency reliability of the constructs, with values between 0.6 to 0.9 indicating satisfactory internal consistency reliability65. Cronbach’s alpha values range from 0.765 to 0.885, with all exceeding the benchmark value of 0.7. This confirms the internal consistency reliability of the construct. Additionally, the AVE values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.5 (ranging from 0.499 for Estonia to 0.684 for Portugal), demonstrating that the constructs account for at least 50% of the variance in their indicators65, which establishes convergent validity. For details, refer to Table S7 in Supplementary Material.

We measure objective and subjective financial well-being using formative indicators. We include a variance inflation factor (VIF) and the statistical significance of the external weights in our estimation of the formative measurement model. In the first step, we check whether there is a significant level of collinearity between indicators, using the VIF criterion, which is a standard metric for assessing the collinearity of indicators66. The acceptable VIF value is below 368. As shown in Table S9, almost all values are below 3, except for Spain, where the indicator “dumps” is 3.347, but as Hair et al.66 argue, results below 5 are also acceptable. The second step involves examining each indicator’s relative contribution to forming the construct. To do this, it is necessary to assess the significance of the indicator weights. In this study, the results are statistically significant in all cases. For details, refer to Table S10 in Supplementary Material.

Structural model analysis

In this subsection, we present the results of the structural model, testing the conceptual framework that links housing affordability to mental health. To understand the mediating role of financial well-being in this relationship, we initially explore three partial models (see Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material).

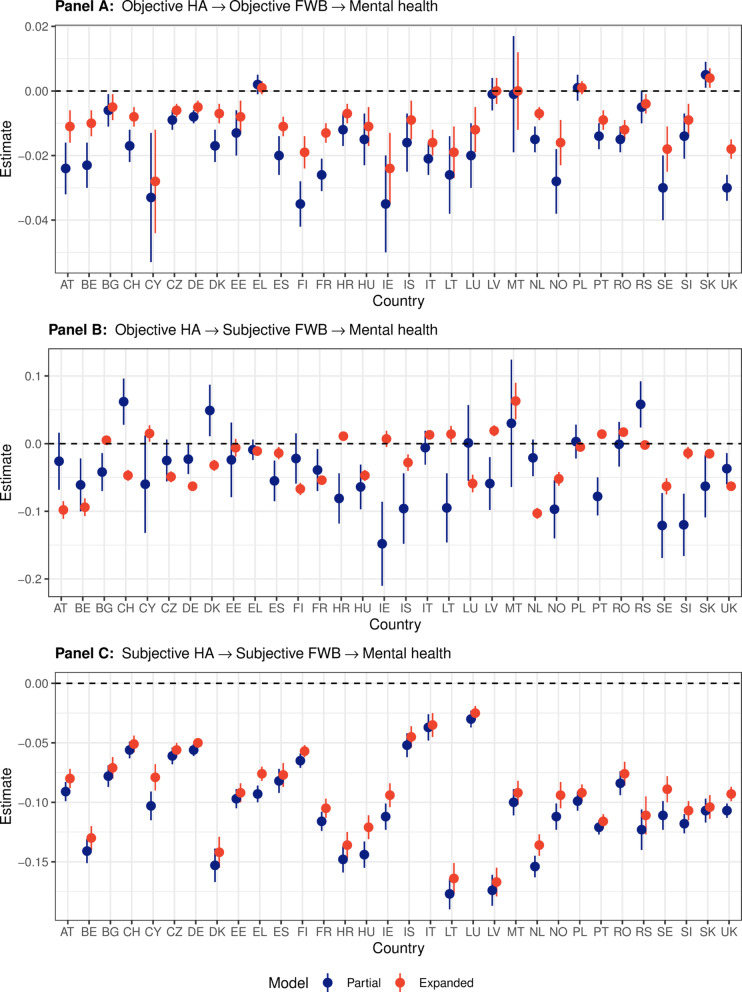

In the first partial model, we posit that objective FWB mediates the relationship between objective HA and MH. Results in most countries indicate a strong negative mediating effect in this relationship (blue dots in Panel A of Fig. 2). Problems related to housing affordability negatively impact the objective financial well-being of households, and lower levels of objective financial well-being are associated with reduced mental health.

Fig. 2.

The mediated effects of financial well-being on the relationship between housing affordability and mental health. Panel (A) reports mediated effects of objective FWB (1 if the household was in arrears on hire purchase installments or other loan payments or utility bills; 0 otherwise) on the relationship between objective HA (1 if the household’s income spent on housing exceeds 30%; 0 otherwise) and mental health (higher values = better mental health). Panel (B) reports mediated effects of subjective FWB (1 if the household has the capacity to afford a one-week annual holiday away from home, to handle unexpected financial expenses, and to spend a small amount of money each week on yourself; 0 otherwise) on the relationship between objective HA and mental health. Panel (C) reports mediated effects of subjective FWB on the relationship between subjective HA (1 if ‘a heavy burden’ or ‘a slight burden’; 0 otherwise) and mental health. The blue dots represent mediated effects from the partial models, the red dots correspond to the expanded model.

In the second partial model, acknowledging the potential negative impact of problems with HA on subjective FWB, we examine the mediating role of subjective FWB in the relationship between objective HA and MH. The results from this partial model (blue dots in Panel B of Fig. 2) corroborate those from the first partial model that utilizes objective FWB, indicating a negative mediating effect in the relationship between objective HA and MH. The magnitude of the effect is greater than in the first partial model, however, in eight countries (Bulgaria, Estonia, Spain, Croatia, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland and Slovenia), this effect is not statistically significant, while in Italy and Portugal, the effect is positive and statistically significant. This reversal in the mediated effect across these countries can be attributed to a weak positive correlation between objective HA and subjective FWB indicators. This correlation can be further understood by the nearly zero correlation between objective HA and the subjective FWB indicators among individuals with high or low values of these dimensions. These observations align with prior research that emphasizes the disparity between subjective perceptions and objective economic indicators9,10.

The third partial model incorporates subjective operationalizations of both HA and FWB (blue dots in Panel C of Fig. 2). Similarly to the models using objective HA, this partial model incorporating subjective HA and subjective FWB yields qualitatively similar results, with heightened effect magnitudes. Households that perceive their total housing costs to be a significant financial burden report lower levels of subjective financial well-being, which in turn impacts their mental health.

Integrating these partial models into an expanded conceptual model (Panel B of Fig. 1) allows for a more complex examination of these relationships. The red dots in Fig. 2 indicate that the overarching findings remain qualitatively consistent. However, compared to the effects estimated from the partial models, the magnitude of effects is somewhat lower. Ultimately, both sets of results lead to the same qualitative conclusions.

Robustness analysis

The main findings of this study are based on a 30% threshold for the objective housing affordability indicator. Because there is no consensus on this value3, and empirical studies employ thresholds ranging from 25 to 50%4, we conduct a robustness analysis using a 40% threshold. This threshold aligns with the value adopted by Eurostat for reporting the housing cost overburden rate69. As shown in Panel A of Table S15, the results remain robust under this alternative threshold. Further, we observe qualitatively similar findings when the same model specifications are applied to 2013 data (Panels B and C of Table S15).

We perform additional robustness checks using an alternative definition of the subjective HA indicator. In the main model, we assign the subjective HA indicator a value of 1 if the respondent reports experiencing either “a heavy burden” or “a slight burden”, and 0 otherwise. In our alternative specification, the subjective HA indicator is assigned a value of 1 only if the respondent selects “a heavy burden”. The results from this alternative model specification (Table S16) indicate qualitatively similar effects for the mediation of subjective FWB in the relationship between subjective HA and MH. We observe minor discrepancies for the total mediated effect of objective FWB in the relationship between objective HA and MH, and a higher prevalence of statistically insignificant effects.

Finally, the main model excludes a direct link between the objective and subjective HA indicators. We estimate an alternative specification incorporating this link (Figure S2), and the results, presented in Table S6, demonstrate the robustness of the findings.

Heterogeneity analysis

To further explore the nuances of the relationship between housing affordability, financial well-being, and mental health, we perform a heterogeneity analysis. This analysis examines whether the observed effects vary across different subgroups of households. This approach enables a deeper understanding of potential disparities and context-specific mechanisms influencing these relationships.

Dividing the sample into subgroups defined by urban–rural settlement (Table S12), housing tenure status (Table S13), and income levels (Table S14) shows that, while there are negative effects in both urban and rural samples, rural households experience stronger indirect effects of subjective affordability on mental health through financial well-being. Households paying housing mortgage or rent face greater affordability challenges than do those without mortgage obligations or who receive free accommodation. The effects are stronger for objective housing affordability. For income levels, the indirect effects are strongest in the bottom 30% of earners, while the top 30% show few significant results.

Discussion

The findings from all models suggest that financial well-being acts as a mechanism through which the relationship between housing affordability and mental health operates. Despite previous research indicating a misalignment between objective and subjective approaches to housing affordability operationalization10, we provide international evidence from numerous countries suggesting that the relationship between mental health and both objectively and subjectively defined housing affordability is, in fact, mediated by financial well-being. Notably, this mediated effect is stronger for subjective HA than it is for objective HA. The stronger effect of the subjective indicator of housing affordability on mental health aligns with research that examines the effects of subjective and objective poverty on mental health. A study by Chang et al.70 provides evidence that reducing subjective poverty has a more substantial positive impact on mental health than does reducing objective poverty. This finding has significant implications for understanding the underlying relationship mechanisms between housing affordability and mental health.

While all of our partial and expanded models point to the same conclusion regarding the mediating role of financial well-being, can we infer whether any of these models is superior to the others? Specifically, can we determine whether objective or subjective indicators are more important in explaining variations in mental health? As indicated in Table S8 of the Supplementary Material, the model incorporating subjective FWB yields higher values of the coefficient of determination than do the models based on objective FWB. This result suggests a stronger mediating effect of subjective than of objective FWB.

Our findings strongly support the mediating role of both objective and subjective FWB in the relationship between corresponding HA indicators and mental health across the EU. However, evidence regarding the mediating role of subjective FWB in the relationship between objective HA and mental health is mixed. This finding holds true for both the partial model and the corresponding link in the expanded model. Ultimately, while we observe a strong mediating effect of objective FWB in the relationship between objective HA and mental health, and a strong mediating effect of subjective FWB in the relationship between subjective HA and mental health; in a few countries, we observe the opposite in the mediating role of subjective FWB in the relationship between objective HA and mental health, suggesting a discrepancy between objective and subjective indicators, as has been previously documented by Seo et al.10.

Based on these findings, it is evident that financial well-being serves as a critical mediator in the relationship between housing affordability and mental health, with subjective financial well-being demonstrating a stronger mediating effect than objective financial well-being. This highlights the necessity for social policies to incorporate both objective and subjective measures of financial well-being and housing affordability when addressing mental health issues. Policies focused solely on objective factors, such as reducing housing costs or alleviating arrears problems, may not capture the full range of the effects of financial distress. To some extent, this has also been demonstrated by existing research, which suggests that, while some interventions targeting objective factors in some contexts have had a positive effect on mental health71, others report no effects72. Therefore, comprehensive interventions should also address subjective perceptions of financial hardship and satisfaction with one’s financial situation, to more effectively mitigate the adverse effects of housing unaffordability on mental health.

Given the significant role of subjective financial well-being, policy-makers should consider strategies that enhance perceived financial security and overall satisfaction with their financial situation. In this vein, Fan and Henager73 argue that interventions aimed at financial well-being should focus on building confidence in financial abilities through programs that enhance self-confidence in financial knowledge, money management skills, and goal-setting abilities. This could involve financial education programs, counselling services, and support systems aimed at improving financial literacy and confidence74,75. By acknowledging and addressing both the objective and subjective dimensions of financial well-being and housing affordability, social policies can be more finely tuned to address the root causes and symptoms of housing-related mental health issues, leading to more effective and sustainable outcomes.

It is important to note that tools targeting objective and subjective dimensions of financial well-being must be strongly coordinated, as these dimensions are deeply interlinked. Focusing exclusively on subjective perceptions, without addressing the underlying objective conditions, could be misleading and potentially even counterproductive. For instance, individuals may experience a temporary boost in perceived financial well-being due to improved financial literacy or confidence, while persistent objective challenges, including inadequate income or overwhelming debt, ultimately undermine their long-term mental health outcomes. Interventions that solely emphasize subjective improvements may risk neglect of structural inequalities or systemic barriers that bar individuals from achieving financial stability. Policy frameworks must integrate interventions that address both dimensions, and ensure that objective measures such as housing affordability, debt reduction, and income adequacy are complemented by strategies to enhance financial confidence, literacy, and satisfaction. This dual approach is essential to creating a comprehensive and sustainable pathway for improving financial well-being and mitigating the adverse effects of financial distress on mental health.

Given the cross-sectional nature of the data and its inherent limitations, the results of this study should be interpreted as correlational rather than causal; this can be considered the key limitation of our study. In our conceptual model, we propose that financial well-being influences mental health. However, it is also plausible that mental health influences financial well-being by reducing productivity or income76, or by increasing the likelihood of unemployment41. This bi-directional nature introduces a potential limitation in our study, as the possibility of reverse causality or omitted variable bias may affect the interpretation of the results. Establishing causality in the relationships examined remains a significant challenge and warrants careful consideration. Future research is essential to address this issue and to explore the bi-directional dynamics underlying the phenomena investigated in this study.

Concluding remarks

In this study, we present a series of findings that offer evidence of the mediating role of financial well-being in the relationship between housing affordability and mental health. Our approach encompasses both objective indicators and subjective operationalizations of housing affordability and financial well-being, and shows their complementary importance alongside conventional objective measures.

Recent economic developments characterized by rising inflation rates and energy prices have increased housing expenses generally, and consequently intensified housing pressure, which can impact household members’ mental health. Understanding this relationship is critical not only for understanding the economic hardships faced by households, but also for appreciating the potential impacts on their mental health.

Consistent with previous research, we show that good financial well-being can reduce the negative impacts of housing affordability on mental health. Specifically, we show that economic hardships experienced by households diminish their financial well-being, and can subsequently impact their mental health. Our results underscore the importance of addressing housing unaffordability not only for economic reasons, but also to support the well-being and mental health of individuals and households.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

V.J., C.S.F., J.W.J.N., T.Ž. designed research, performed research, and wrote the manuscript; V.J. analyzed data.

Funding

The work of Jurčišinová was supported by the the Slovak Scientific Grant Agency under Grant no. VEGA-1/0034/23. The work of Želinský was supported by the Czech Science Foundation under Grant no. 23-06264S. Želinský also acknowledges institutional support from the Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Sociology (RVO: 68378025). Forbes acknowledges financial support under National Science Foundation Grant SES-1921523.

Data availability

The analyses presented in this paper are based on EU-SILC microdata, which was made available under contract No. RPP 319/2022-EU-SILC between the European Commission, Eurostat, and the Technical University of Košice. Details on accessing EU-SILC microdata for scientific purposes can be found at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata. The contact person for the database utilized in our study is Tomáš Želinský (tomas.zelinsky@tuke.sk). Responsibility for all conclusions drawn from the data lies entirely with the authors.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-00997-1.

References

- 1.Rangel, G. J. et al. Measuring Malaysian housing affordability: the lifetime income approach. Inter. J. Housing Markets Anal.12, 966–984 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hulchanski, J. D. The concept of housing affordability: Six contemporary uses of the housing expenditure-to-income ratio. Hous. Stud.10, 471–491 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bramley, G. Affordability, poverty and housing need: Triangulating measures and standards. J. Housing Built Environ.27, 133–151 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, J., Hao, Q. Q. & Stephens, M. Assessing Housing Affordability in Post Reform China: A Case Study of Shanghai. Hous. Stud.25, 877–901 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lester, L. et al. The ROC and role of the 30% Rule. 7th Australasian Housing Researchers’ Conference: Refereed Proceedings, 1–13 (2013).

- 6.Daniel, L. et al. Measuring Housing Affordability Stress: Can Deprivation Capture Risk Made Real?. Urban Policy Res.36, 271–286 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heylen, K. Measuring housing affordability. A case study of Flanders on the link between objective and subjective indicators. Housing Stud.38, 552–568 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Özdemir Sarı, Ö. B. & Aksoy Khurami, E. Housing Affordability Trends and Challenges in the Turkish Case. J. Housing Built Environ.38, 305–324 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunega, P. & Lux, M. Subjective perception versus objective indicators of overcrowding and housing affordability. J. Housing Built Environ.31, 695–717 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo, B. K. et al. The incongruence between objective and subjective rental affordability: Does residential satisfaction matter?. Cities141, 104471 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertrand, M. & Mullainathan, S. Do People Mean What They Say? Implications for Subjective Survey Data. Am. Econ. Rev.91, 67–72 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel, J. Strategies and Traditions in Swedish Social Reporting: A 30-Year Experience. Soc. Indic. Res.58, 89–112 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagerty, M. R. et al. Quality of Life Indexes for National Policy: Review and Agenda for Research. Bullet. Sociol. Methodol. Bull. Méthodol. Sociol.71, 58–79 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stiglitz, JE., Sen, A. & Fitoussi, J.-P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, 2009). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdf.

- 15.Veenhoven, R. Why Social Policy Needs Subjective Indicators. Soc. Indic. Res.58, 33–46 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steger, M. F. & Samman, E. Assessing meaning in life on an international scale: Psychometric evidence for the meaning in life questionnaire-short form among Chilean households. Inter. J. Well.2, 182–195 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gimpelson, V. & Treisman, D. Misperceiving inequality. Econ. Politics30, 27–54 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn, A. The subversive nature of inequality: Subjective inequality perceptions and attitudes to social inequality. Eur. J. Polit. Econ.59, 331–344 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kutty, N. K. A new measure of housing affordability: Estimates and analytical results. Hous. Policy Debate16, 113–142 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deidda, M. Economic Hardship, Housing Cost Burden and Tenure Status: Evidence from EU- SILC. J. Fam. Econ. Issues36, 531–556 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lund, C. et al. Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: a systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatr.5, 287–378 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braubach, M. Key challenges of housing and health from WHO perspective. Int. J. Public Health56, 579–580 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung, R.Y.-N. Housing affordability effects on physical and mental health: household survey in a population with the world’s greatest housing affordability stress. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health74, 164–172 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, Ch. & Zhang, F. Effects of housing wealth on subjective well-being in urban China. J. Housing Built Environ.34, 965–985 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker, E. et al. New evidence on mental health and housing affordability in cities: A quantile regression approach. Cities96, 102455 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benfer, E. A. et al. Eviction, Health Inequity, and the Spread of COVID-19: Housing Policy as a Primary Pandemic Mitigation Strategy. J. Urban Health98, 1–12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bower, M. et al. ‘Trapped’, ‘anxious’ and ‘traumatised’: COVID-19 intensified the impact of housing inequality on Australians’ mental health. Int. J. Hous. Policy23, 260–291 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason, K. E. et al. Housing affordability and mental health: Does the relationship differ for renters and home purchasers?. Soc. Sci. Med.94, 91–97 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker, E. et al. Mental health and prolonged exposure to unaffordable housing: a longitudinal analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol.55, 715–721 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh, A. et al. Do financial hardship and social support mediate the effect of unaffordable housing on mental health?. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol.55, 705–713 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyle, T. & Dunn, J. R. Effects of housing circumstances on health, quality of life and healthcare use for people with severe mental illness: a review. Health Soc. Care Community.16, 1–15 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn, J. R. Housing and Health Inequalities: Review and Prospects for Research. Hous. Stud.15, 341–366 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Botha, F. et al. Housing affordability stress and mental health: The role of financial wellbeing. Australian Econ. Papers.63, 1–20 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owusu, G. M. Y. Predictors of financial satisfaction and its impact on psychological wellbeing of individuals. J. Hum. Appl. Social Sci.5, 59–76 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, T. et al. Financial literacy and household financial resilience. Financ. Res. Lett.63, 105378 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yue, P. et al. Household Financial Decision Making Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade56, 2363–2377 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yue, P. et al. The rise of digital finance: Financial inclusion or debt trap?. Financ. Res. Lett.47, 102604 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryu, S. & Fan, L. The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among U.S. adults. J. Family Econ. Issues44, 16–33 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bialowolski, P. et al. The role of financial conditions for physical and mental health. Evidence from a longitudinal survey and insurance claims data. Soc. Sci. Med.281, 114041 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guan, N. et al. Financial stress and depression in adults: A systematic review. PLoS ONE17, e0264041 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bubonya, M. et al. The reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and employment status. Econ. Hum. Biol.35, 96–106 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowley, S. et al. Do traditional measures of housing stress accurately reflect household financial wellbeing? 5th Australasian Housing Researchers’ Conference, 17–19 November, University of Auckland, New Zealand (2010).

- 43.Rowley, S. & Ong, R. Housing affordability, housing stress and household wellbeing in Australia. AHURI Final Report No. 192 (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2012).

- 44.Rowley, S. et al. Bridging the Gap between housing stress and financial stress: The case of Australia. Hous. Stud.30, 473–490 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Comerton-Forde, C. et al. Measuring Financial Wellbeing with Self-Reported and Bank Record Data. Econ. Record98, 133–151 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tharp, D. T. et al. Financial Satisfaction and Homeownership. J. Fam. Econ. Issues41, 255–280 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borrowmann, L. et al. How long do households remain in housing affordability stress?. Hous. Stud.32, 869–886 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiely, K. M. et al. How financial hardship is associated with the onset of mental health problems over time. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol.50, 909–918 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sargent-Cox, K. et al. The global financial crisis and psychological health in a sample of Australian older adults: A longitudinal study. Soc. Sci. Med.73, 1105–1112 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foong, H. F. et al. Relationship between financial well-being, life satisfaction, and cognitive function among low-income community-dwelling older adults: the moderating role of sex. Psychogeriatrics21, 586–595 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eurostat. Reference metadata: Income and living conditions (ilc). Retrieved [December 12, 2024] from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/ilc_sieusilc.htm (2024).

- 52.Stewart, A. L., Hays, R. D. & Ware, J. E. The MOS Short-Form General Health Survey. Med. Care26, 724–735 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamazaki, S., Fukuhara, S. & Green, J. Usefulness of five-item and three-item Mental Health Inventories to screen for depressive symptoms in the general population of Japan. Health Qual. Life Outcomes.3, 48 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhan, D. et al. The impact of housing pressure on subjective well-being in urban China. Habitat Int.127, 102639 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Netemeyer, R. G. et al. How Am I Doing? Perceived Financial Well-Being, Its Potential Antecedents, and Its Relation to Overall Well-Being. J. Consumer Res.45, 68–69 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hair, JF. et al. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (SAGE Publications, 2017).

- 57.Ringle, C. M., Wende, S. & Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4 (SmartPLS GmbH, 2022). Available at: http://www.smartpls.com.

- 58.Hair, J. F. et al. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) 3rd edn. (Sage, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) 2nd edn. (SAGE Publications Inc, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Thiele, K. O. & Gudergan, S. P. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies!. J. Bus. Res.69, 3998–4010 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bollen, K. A. & Bauldry, S. Three Cs in measurement models: Causal indicators, composite indicators, and covariates. Psychol. Methods16, 265–284 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jarvis, C. B., Mackenzie, S. B. & Podsakoff, P. M. A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research. J. Consumer Res.30, 199–218 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sarstedt, M. & Mooi, E. A Concise Guide to Market Research: The Process, Data, and Methods Using IBM SPSS Statistics 273–324 (Springer, 2014).

- 64.Sarstedt, M. et al. Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychol. Mark.39, 1035–1064 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hair, J. F. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev.31, 2–24 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hair, JF. et al. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. A Workbook (Springer, 2021).

- 67.Dijkstra, T. & Henseler, J. Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Q.39, 297–316 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Becker, JM. et al. How Collinearity Affects Mixture Regression Results. Marketing Letters. 26, 643–659 (2015).

- 69.Eurostat. Glossary: Housing cost overburden rate. Retrieved [December 12, 2024] from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Glossary:Housing_cost_overburden_rate (2024).

- 70.Chang, Q. et al. Mechanisms connecting objective and subjective poverty to mental health: Serial mediation roles of negative life events and social support. Soc. Sci. Med.265, 113308 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Denary, W. et al. Does rental assistance improve mental health? Insights from a longitudinal cohort study. Soc. Sci. Med.282, 114100 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fertig, A. R. & Reingold, D. A. Public housing, health, and health behaviors: Is there a connection?. J. Policy Anal. Manage.26, 831–860 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fan, L. & Henager, R. A structural determinants framework for Financial Well-Being. J. Fam. Econ. Iss.43, 415–428 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Archuleta, K. L. et al. Financial Goal Setting, Financial Anxiety, and Solution-Focused Financial Therapy (SFFT): A Quasi-experimental Outcome Study. Contemp. Fam. Ther.42, 68–76 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henager, R. & Cude, B. J. Financial literacy and long- and short-term financial behavior in different age groups. J. Financ. Couns. Plan.27, 3–19 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Babiarz, P. & Yilmazer, T. The impact of adverse health events on consumption Understanding the mediating effect of income transfers, wealth, and health insurance. Health Econ.26, 1743 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The analyses presented in this paper are based on EU-SILC microdata, which was made available under contract No. RPP 319/2022-EU-SILC between the European Commission, Eurostat, and the Technical University of Košice. Details on accessing EU-SILC microdata for scientific purposes can be found at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata. The contact person for the database utilized in our study is Tomáš Želinský (tomas.zelinsky@tuke.sk). Responsibility for all conclusions drawn from the data lies entirely with the authors.