Abstract

The synthesis of propargyl ethers is an efficient way to access a variety of pharmaceuticals and natural products. However, direct etherification of simple alkynes via propargylic C–H activation remains largely underreported, while propargylic substitution of prefunctionalized alkyne starting materials remains the dominant method for the synthesis of propargyl ethers. Herein, we report an organometallic umpolung approach for iron-mediated C–H propargylic etherification. The stepwise iron-mediated C–H activation followed by mild oxidative functionalization enables the first use of unadorned alkynes to preferentially couple with alcohols for the efficient synthesis of synthetically important propargylic ethers with excellent functional group compatibility, chemoselectivity and regioselectivity.

Keywords: C–H functionalization, umpolung, oxidation, organometallics, etherification

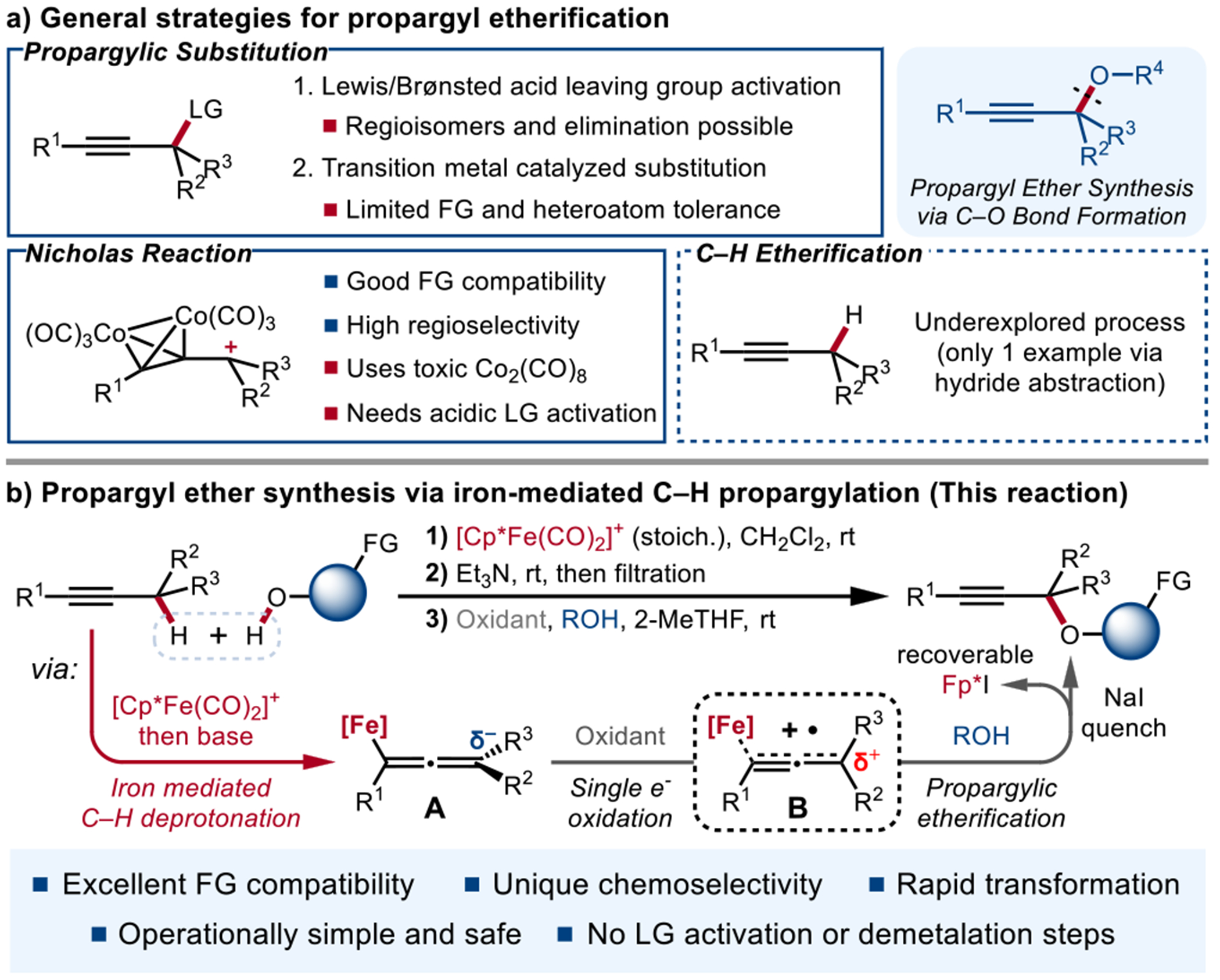

Etherification enabled by C–H functionalization, specifically the construction of C–O bonds α to π bonds, is an important transformation to access a variety of pharmaceuticals and natural products.[1] While a wide range of C–H etherification reactions has been developed and utilized for the construction of benzylic[2] and allylic[3] ethers, analogous propargylic C–H etherification remains conspicuously unreported, with propargylic substitution being the dominant approach to access propargylic ethers.

Among all propargylic substitution reaction and their derivatives, the Nicholas reaction is among the most reliable and heavily employed stoichiometric organometallic transformations for the synthesis of alkynes carrying functional groups at the propargylic position.[4] Given its excellent functional group tolerance, the Nicholas reaction has been widely accepted as a powerful tool in the synthesis of natural products and bioactive molecules.[5] In addition to the Nicholas reaction, a multitude of other propargylic substitution processes have also been developed.[6] These include Lewis or Brønsted acid catalyzed processes,[7] as well as transition metal catalyzed cross coupling[8] and allenylidene mediated propargylic substitution.[9] However, despite substantial recent progress, including the development of enantioselective processes, only functionally simple alcohols have been applied in these propargyl etherification reactions. Moreover, reactions mediated by unbounded propargyl cations are highly substrate dependent and, in many cases, may give the isomeric allene derivative as a side product.[10] Yet, all currently reported propargylic etherification reactions require the pre-installation a leaving group.

In contrast to substitution-based strategies, the C–H functionalization of unadorned alkynes at the propargylic position is significantly underexplored, compared to analogous allylic C–H etherification,[11] in part due to the higher α-C–H bond dissociation energy (BDE) of alkynes (92.5 kcal mol−1 for propyne) compared to analogous alkenes (88.2 kcal mol−1 for propene).[12] Previous strategies on the oxidative coupling between nucleophiles and alkynes generally require electronic activation of the propargylic C–H bond with additional heteroatoms or π-bonds at the α-position,[13] or proceed through intramolecular C–H insertion of metal carbene/nitrene intermediates derived from nucleophilic precursors.[14] However, since metal-oxo species that function as oxene equivalents are limited to the delivery of a single oxygen atom, the coupling between alkynes and oxygen nucleophiles remains a relatively limited process. Direct oxygenation products like ynones,[15] propargyl alcohols,[16] and propargyl peroxides [17] can be obtained under catalytic and stoichiometric oxidative conditions, while a limited range of propargyl esters can be synthesized via the Kharasch-Sosnovsky reaction.[18]

However, to the best of our knowledge, the synthesis of propargyl ethers from the simple alkynes by C(sp3)–H functionalization has not been previously reported. The lack of such transformation is not surprising, given the inapplicability of formal oxene insertion processes and the difficulty of controlling processes that generate free propargylic cations, necessitating the development of a new mechanistic framework. Moreover, the development of a generally applicable process would also need to address the selective functionalization of the propargylic position over allylic and benzylic C–H bonds that may also be present in more structurally complex substrates.

Previously, our group has developed a strategy for the catalytic generation of propargylic anion equivalents from alkynes for redox-neutral C–H functionalization.[19] In this strategy, electron-rich allenyliron intermediates (Scheme 1b, A) are readily generated by deprotonation of alkyne–[Fp*]+ (Fp* = Cp*Fe(CO)2, Cp* = η5-C5Me5) complexes by amine bases. The allenyliron intermediates underwent reactivity with electrophiles to deliver propargylic functionalization products in high regioselectivity. Intriguingly, reports by Selegue, Lapinte, and Giering indicate that, upon one electron oxidation, allyl-, alkenyl- and alkynyl-iron species similarly undergo oxidative coupling reactions in a highly regiocontrolled manner.[20] These studies indicate that cyclopentadienyliron-based organometallic species can undergo polarity reversal (umpolung) to act as electrophiles when subjected to one-electron oxidation.[21] Additionally, Lapinte and Sponsler had reported structurally characterized vinyl- and dienyl-iron radical cations and dications as part of electrochemical investigations.[22] Consequently, we speculated that our Fp*-derived allenyliron complexes could similarly be oxidized to organometallic radical cations that serve as propargyl cation synthons for an umpolung propargylic functionalization process (Scheme 1b, B). In particular, the coupling of these radical cationic species with alcohols would generate propargylic ethers, potentially with high functional group compatibility and unique regioselectivity and chemoselectivity. Based on these considerations, we report herein the successful development of such a process, one that could be applied to the preparation of propargylic ethers from various internal alkynes in the presence of a range of heterocycles and pharmaceutical derivatives.

Scheme 1.

State of art for propargylic ethers synthesis via C–O bond formation.

To begin our investigation, we measured the oxidation potential of allenyliron species 1a’ to be +0.65 V vs. ferrocene (EoFc+/0 = +0.45 V vs. Ag/AgCl) in CH2Cl2. With the electrochemical data obtained, we considered Ag+ sources as strong yet functional group tolerant oxidants, which were previously used in the oxidation of iron half-metallocene complexes.[23] We were pleased to find that oxidation of 1a’ with AgBF4 in the presence of benzyl alcohol (2a) afforded benzyl ether 3a in 8% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Of solvents tested for the reaction (entries 2-6), 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) was found to be optimal (entry 6). Subsequently, several other common oxidants were examined (entries 7-13). While AgOTf was also effective (entry 7), an alternative organic oxidant thianthrenium tetrafluoroborate (TTBF4) also afforded the product in significant yield (entry 12). No product was observed without the addition of oxidant (entry 14). It was found that the reaction occurred rapidly, reaching completion within 5 min (entry 15). To improve the operational simplicity of the propargylic ether synthesis, a one-pot protocol that uses alkyne 1a directly as the starting material and avoids the isolation of the allenyliron intermediate (1a’) was developed (entry 17), with use of the alcohol as the limiting reagent further increasing the yield (entry 18). Under otherwise successful reaction conditions, the replacement of the Cp* ligand on Fe with Cp resulted in no formation of 3a (entry 16).

Table 1.

Preparation of key organoiron species and reaction optimization.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Entry[a] | Solvent | Oxidant | Time | Yield (%)[b] |

| 1 | MeCN | AgBF4 | 15 h | 8 |

| 2 | DCM | AgBF4 | 15 h | 0 |

| 3 | MeNO2 | AgBF4 | 15 h | 29 |

| 4 | 1,4-Dioxane | AgBF4 | 15 h | 10 |

| 5 | THF | AgBF4 | 15 h | 46 |

| 6 | 2-MeTHF | AgBF4 | 15 h | 52 |

| 7 | 2-MeTHF | AgOTf | 15 h | 37 |

| 8 | 2-MeTHF | Ag2O | 15 h | 0 |

| 9 | 2-MeTHF | Cu(OTf)2 | 15 h | 0 |

| 10 | 2-MeTHF | FcPF6 | 15 h | 0 |

| 11 | 2-MeTHF | (NH4)2Ce(NO3)6 | 15 h | 0 |

|

| ||||

| 12 | 2-MeTHF | TTBF4 | 60 min | 30 |

|

| ||||

| 13[c] | 2-MeTHF | (4-BrC6H4)3NSbCl6 | 60 min | <5 |

| 14 | 2-MeTHF | no oxidant | 15 h | 0 |

| 15 | 2-MeTHF | AgBF4 | 5 min | 56 |

| 16[d] | 2-MeTHF | AgBF4 | 5 min | 0 |

|

| ||||

| 17[e] | 2-MeTHF | AgBF4 | 5 min | 58 |

|

| ||||

| 18[f] | 2-MeTHF | AgBF4 | 5 min | 74(71)[g] |

Reaction conditions: allenyliron (0.1 mmol), BnOH (0.3 mmol), oxidant (0.2 mmol), solvent (1.0 mL), rt.

NMR yields.

Mixture of allenyliron and alcohol added to [(4-BrC6H4)3N]SbCl6 at −78°C and allowed to warm to rt over 30 min.

The allenyliron based on Fp (= CpFe(CO)2) was used instead of the Fp* complex.

Reaction conditions: allenyliron (in situ from 0.11 mmol alkyne), BnOH (0.3 mmol), oxidant (0.2 mmol), solvent (1.0 mL), rt (see the Supporting Info GP-IV for detailed process).

Reaction conditions: allenyliron (in situ from 0.33 mmol alkyne), BnOH (0.1 mmol), oxidant (0.5 mmol), solvent (1.5 mL), rt (see the Supporting Info GP-I for detailed process).

Isolated yield.

DCM = dichloromethane. DMF = N,N-dimethylformamide. THF = tetrahydrofuran. 2-MeTHF = 2-methyltetrahydrofuran. FcPF6 = ferrocenium hexafluorophosphate. TTBF4 = thianthrenium tetrafluoroborate.

We then applied the optimized condition for reaction scope exploration using more heavily functionalized alkyne (1) and alcohol (2) coupling partners. The reaction demonstrated compatibility toward a wide-ranging variety of heterocycles including a thiazole (3b), a pyridine (3c), a quinoline (3d), a pyrimidine (3e), a pyrazole (3h), and others (3f, 3g, 3i-3k). Unsaturated functional groups including internal (3q) and terminal alkenes (3p), an alkyne (3r), an allene (3o) and a diazene (3s) were also well tolerated. This reaction could also be applied to the sterically demanding propargyl ethers (3l-3n). In addition, various nitrogen containing functional groups like a nitrile (3t), a nitro group (3u), an unprotected amine (3w), a squaramide (3z), a carboxamide (3aa) and an azide (3ad) were likewise tolerated, and these substrates reacted with chemoselectivity for propargyl ether formation. Highly polar functional groups, including a carboxylic acid (3v), and a phosphonate ester (3x), were also compatible. An aryl boronic ester (3y) was similarly unaffected by the reaction conditions. Fluorine containing functional groups including a trifluoromethylthio group (3ac), a pentafluorosulfanyl group (3ai), and a perfluorophenyl group (3an) could also be successfully employed. Several drug molecules or their derivatives (3ar-3au) were also successfully functionalized using this transformation.[24] This protocol could also make use of water as nucleophile for the regioselective synthesis of propargylic alcohols by C–H hydroxylation (3am). Notably, this approach was successful for a substrate containing several other C–H bonds susceptible to hydrogen atom abstraction (3am), demonstrating the orthogonality of this this approach to methods based on hemolytic C–H cleavage.

Besides the excellent scope of alcohols that could be employed, this transformation was also compatible with alkynes bearing electron-rich (3ag) and electron-poor (3ah) aryl groups. However, yields tended to be highest for electron-neutral alkynes, while electron-rich alkynes tended to give more 1,3-enyne as the side product due to overoxidation (see the Supporting Information for a discussion), while the key radical cation intermediate derived from electron-poor alkynes are likely to be less stable.[25] A span of different steric properties was also tolerated, ranging from a methyl-substituted phenylacetylene (3ae) to one bearing a bulky diphenylmethyl group (3l). Dialkylacetylenes (3ap, 3aq) could also be successfully employed to give propargylic ethers in moderate yields, with high regioselectivity observed for the more substituted product in the case of unsymmetrical substrates. An isolated enyne (3al) and an isolated diyne (3ak) could also be applied in this reaction to give propargylic ethers with exclusive chemo- and regioselectivity, again illustrating the distinct selectivity of this process over other methods mediated by H–atom abstraction. It bears mention that the ratio of alkyne and alcohol could also be reversed to accommodate the accessibility of each coupling partner. While lower yields were usually observed when alkyne was used as limiting reagent, the amount of metal and oxidant needed could be significantly reduced, allowing for improved ease of purification (see the Supporting Information). Finally, a modified protocol using thianthrenium tetrafluoroborate (TTBF4) as the oxidant was also developed, allowing for a procedure that avoids the use of silver.

Compared to the Lewis acid promoted substitution of propargylic alcohols, this approach exhibited exceptional tolerance to substrates containing Lewis basic nitrogen atoms. For example, attempts to affect the substitution of 4-phenyl-3-butyn-2-ol with 3-pyridinemethanol (2c) using a range of Lewis acids (FeCl3, Et2O·BF3, Sc(OTf)3) that have been used to promote the formation of propargylic cation intermediates were uniformly unsuccessful, resulting in no conversion of the alcohol.[26] However, the same alcohol was a fully competent coupling partner under our reaction conditions (3c, 77% yield). Moreover, in all cases examined, the current protocol gave propargylic ether product without concomitant formation of the regioisomeric allenylic ether (>20:1 in the crude material). These observations strongly suggest that C–O bond formation is not mediated by (free) carbocationic intermediates.[27] Furthermore, a preliminary comparison with the Nicholas reaction using glycolic acid as the substrate (3av, 22% yield) indicated that this process exhibits distinct chemoselectivity compared to the classical cobalt-mediated process (see the Supporting Information). When the reaction was conducted on larger scale, it was found that, by quenching the reaction mixture with a solution of NaI in acetone, much of the iron reagent could be recovered chromatographically as the bench stable iodide complex, Fp*I. Similarly, when TTBF4 was used as the oxidant, thianthrene could be recovered in near-quantitative yield (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Scale-up and recovery of reagents.

Since the formation of allenyliron intermediate has been well-studied by our group and others,[19b, 19e, 28] we focused our attention on clarifying the mechanism of the later umpolung C–O bond forming process. A series of mechanism experiments were performed to gain some evidence for the key proposed intermediate. First, 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO, 1.0 equiv) was added to the reaction mixture to intercept the proposed intermediate. The propargyl-TEMPO adduct 4 was isolated in 56% yield (Scheme 4a), while the propargylic ether product 3a was not observed. The TEMPO adduct 4 could also be obtained from 1a’ alone in the absence of alcohol. A further control experiment was conducted without the presence of AgBF4. However, these conditions did not afford adduct 4, suggesting that formation of 4 required oxidation by silver(I). Moreover, treatment of 1a’ with TEMPO+ also resulted in no reaction, suggesting that role of silver(I) was to oxidize the allenyliron species rather than the TEMPO. Considered in conjunction with previous observations regarding the scope and the regiocontrol, these experiments suggest an intermediate with radical character is generated from the reaction of allenyliron species and AgBF4.[29] We propose that this intermediate is radical cation B, which is intercepted by the alcohol to give β-metalloradical C.[19d, 30] Further oxidation then affords the observed product 3 and [Fp*]+ fragment (recovered as Fp*I).

Scheme 4.

Mechanistic experiments.

To summarize, we have reported an organometallic umpolung approach for iron-mediated propargylic C–H etherification capable of coupling unactivated alkynes and alcohols for the synthesis of highly functionalized propargyl ethers. The reaction could be performed under mild conditions under operationally simple reaction conditions and in short reaction times, and each of the two coupling partners could be extensively varied, leading to products of exceptional structural and functional group diversity. Preliminary mechanistic investigations support a reaction pathway involving the nucleophilic trapping of organometallic radical cation intermediates. Further applications of deprotonative propargylic C–H functionalization under oxidative conditions are under investigation in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Propargyl ether scope.[a].

[a] Unless otherwise stated, all yields were obtained following GP-I: 1) alkyne (0.66 mmol), Fp*I (0.6 mmol), AgBF4 (0.6 mmol), DCM (0.6 mL), rt, 15 h; 2) Et3N (1.2 mmol), rt, 1 h; 3) alcohol (0.2 mmol), AgBF4 (1.0 mmol), 2-MeTHF (2.4 mL), rt, 30 min. [b] Following GP-II: 1) alkyne (0.66 mmol), Fp*(thf)BF4 (0.6 mmol), Et2O·BF3 (1.8 mmol), DCM (0.6 mL), rt, 15 h; 2) Et3N (2.4 mmol), rt, 1 h; 3) alcohol (0.2 mmol), AgBF4 (1.0 mmol), 2-MeTHF (2.4 mL), rt, 30 min. [c] Following GP-III: 1) alkyne (0.9 mmol), Fp*(thf)BF4 (0.6 mmol), DCM (0.6 mL), rt, 15 h; 2) Et3N (0.72 mmol), rt, 1 h; 3) alcohol (0.2 mmol), TTBF4 (0.8 mmol), 2,6-di-t-butylpyridine (0.9 mmol), 1,2-DCE (2.4 mL), 0°C, 30 min. [d] 4.0 equiv Et3N used in step 2. [e] 3.0 equiv Et2O·BF3 added in step 3. [f] alkyne as limiting reagent (see the Supporting Information).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health (R35GM142945, Y.-M.W.). We thank Zhengru Liu (Star group) for CV data acquisition. We thank Yifan Qi (Brummond group) for IR data acquisition. We thank Steven Geib (University of Pittsburgh) for XRD data acquisition. We thank Yuting Song (Wang group) for known substrate synthesis. We thank Jiao Yu (Wang group) for discussions and proofreading of the experimental procedures and spectral data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This manuscript has been accepted after peer review and appears as an Accepted Article online prior to editing, proofing, and formal publication of the final Version of Record (VoR). The VoR will be published online in Early View as soon as possible and may be different to this Accepted Article as a result of editing. Readers should obtain the VoR from the journal website shown below when it is published to ensure accuracy of information. The authors are responsible for the content of this Accepted Article.

Supporting Information

The authors have cited additional references within the Supporting Information.

References

- [1].For significance of C-H functionalization in synthesizing pharmaceuticals and natural products, see:; a) Gutekunst WR, Baran PS, Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 1976–1991; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Guillemard L, Kaplaneris N, Ackermann L, Johansson MJ, Nat. Rev. Chem 2021, 5, 522–545; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Budnikov AS, Krylov IB, Mulina OM, Lapshin DA, Terent’ev AO, Adv. Synth. Catal 2023, 365, 1714–1755; [Google Scholar]; Ethers are important moieties commonly found in a variety of pharmaceuticals and natural products, for examples, see:; d) Enthaler S, Company A, Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 4912–4924; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Roughley SD, Jordan AM, J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 3451–3479; . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Hu H, Chen S-J, Mandal M, Pratik SM, Buss JA, Krska SW, Cramer CJ, Stahl SS, Nat. Catal 2020, 3, 358–367; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee BJ, DeGlopper KS, Yoon TP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 197–202; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dong M, Jia Y, Zhou W, Gao J, Lv X, Luo F, Zhang Y, Liu S, Org. Chem. Front 2021, 8, 6881–6887; [Google Scholar]; d) Golden DL, Suh S-E, Stahl SS, Nat. Rev. Chem 2022, 6, 405–427; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Bone KI, Puleo TR, Delost MD, Shimizu Y, Bandar JS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2024, 63, e202408750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Ammann SE, Rice GT, White MC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10834–10837; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang P-S, Liu P, Zhai Y-J, Lin H-C, Han Z-Y, Gong L-Z, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 12732–12735; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ammann SE, Liu W, White MC, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 9571–9575; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Qi X, Chen P, Liu G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 9517–9521; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kazerouni AM, McKoy QA, Blakey SB, Chem. Commun 2020, 56, 13287–13300; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Wang H, Liang K, Xiong W, Samanta S, Li W, Lei A, Sci. Adv 2020, 6, eaaz0590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Green JR, Nicholas KM, Propargylic Coupling Reactions via Bimetallic Alkyne Complexes: The Nicholas Reaction. Organic Reactions. Wiley, 2020, pp. 931–1326; [Google Scholar]; b) Teobald BJ, Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 4133–4170; [Google Scholar]; c) Díaz DD, Betancort JM, Martín VS, Synlett 2007, 0343–0359. [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Jacobi PA, Murphree S, Rupprecht F, Zheng W, J. Org. Chem 1996, 61, 2413–2427; [Google Scholar]; b) Magnus P, Eisenbeis SA, Fairhurst RA, Iliadis T, Magnus NA, Parry D, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 5591–5605; [Google Scholar]; c) Isobe M, Hamajima A, Nat. Prod. Rep 2010, 27, 1204–1226; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kann N, Curr. Org. Chem 2012, 16, 322–334; [Google Scholar]; e) Djurdjevic S, Green JR, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 5468–5471; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Rodríguez-López J, Pinacho Crisóstomo F, Ortega N, López-Rodríguez M, Martín VS, Martín T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 3659–3662; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Djurdjevic S, Green JR, Synlett 2014, 25, 2467–2470; [Google Scholar]; h) Rodríguez-López J, Ortega N, Martín VS, Martín T, Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 3685–3688; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Shao H, Bao W, Jing Z-R, Wang Y-P, Zhang F-M, Wang S-H, Tu Y-Q, Org. Lett 2017, 19, 4648–4651; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Johnson RE, Ree H, Hartmann M, Lang L, Sawano S, Sarpong R, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 2233–2237; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Nicolaou KC, Pan S, Shelke Y, Das D, Ye Q, Lu Y, Sau S, Bao R, Rigol S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 9267–9276; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Wang H, Liu Y, Zhang H, Yang B, He H, Gao S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2023, 145, 16988–16994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Detz RJ, Hiemstra H, van Maarseveen JH, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2009, 2009, 6263–6276; [Google Scholar]; b) Bauer EB, Synthesis 2012, 44, 1131–1151; [Google Scholar]; c) Nishibayashi Y, Synthesis 2012, 44, 489–503; [Google Scholar]; d) Roy R, Saha S, RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 31129–31193; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Tsuji H, Kawatsura M, Asian J. Org. Chem 2020, 9, 1924–1941; [Google Scholar]; f) Nishibayashi Y, Chem. Lett 2021, 50, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar]

- [7].For reviews:; a) Debleds O, Gayon E, Vrancken E, Campagne J-M, Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2011, 7, 866–877; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For selected articles:; b) Bartels A, Mahrwald R, Quint S, Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 5989–5990; [Google Scholar]; c) Karunakar GV, Periasamy M, J. Org. Chem 2006, 71, 7463–7466; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhan Z-P, Yang W-Z, Yang R-F, Yu J-L, Li J-P, Liu H-J, Chem. Commun 2006, 3352–3354; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Qin H, Yamagiwa N, Matsunaga S, Shibasaki M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2007, 46, 409–413; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Huang W, Wang J, Shen Q, Zhou X, Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 11636–11643; [Google Scholar]; g) Liu X-T, Huang L, Zheng F-J, Zhan Z-P, Adv. Synth. Catal 2008, 350, 2778–2788; [Google Scholar]; h) Rubenbauer P, Herdtweck E, Strassner T, Bach T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 10106–10109; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Ohta K, Koketsu E, Nagase Y, Takahashi N, Watanabe H, Yoshimatsu M, Chem. Pharm. Bull 2011, 59, 1133–1140; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Donald CP, Boylan A, Nguyen TN, Chen P-A, May JA, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 6767–6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].For reviews:; a) Ljungdahl N, Kann N, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 642–644; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mandai T, Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis, Wiley, 2022, pp. 1845–1858; [Google Scholar]; c) Kobayashi Y, Catalysts 2023, 13, 132; [Google Scholar]; For selected articles:; d) Marshall JA, Wolf MA, J. Org. Chem 1996, 61, 3238–3239; [Google Scholar]; e) Sherry BD, Radosevich AT, Toste FD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 6076–6077; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Smith SW, Fu GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 12645–12647; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Smith SW, Fu GC, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 9334–9336; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Daniels DSB, Thompson AL, Anderson EA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 11506–11510; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Schley ND, Fu GC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 16588–16593; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Daniels DSB, Jones AS, Thompson AL, Paton RS, Anderson EA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 1915–1920; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Ambrogio I, Cacchi S, Fabrizi G, Goggiamani A, Iazzetti A, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2015, 2015, 3147–3151. [Google Scholar]

- [9].For reviews:; a) Miyake Y, Uemura S, Nishibayashi Y, ChemCatChem 2009, 1, 342–356; [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang D-Y, Hu X-P, Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 283–295; [Google Scholar]; c) Sakata K, Nishibayashi Y, Catal. Sci. Technol 2018, 8, 12–25; [Google Scholar]; d) Zhang Y-P, You Y, Yin J-Q, Wang Z-H, Zhao J-Q, Li Q, Yuan W-C, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2023, 26, e202300728; [Google Scholar]; e) Li M-D, Wang X-R, Lin T-Y, Tetrahedron Chem 2024, 11, 100082; [Google Scholar]; For selected articles:; f) Nishibayashi Y, Inada Y, Yoshikawa M, Hidai M, Uemura S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2003, 42, 1495–1498; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Nishibayashi Y, Milton MD, Inada Y, Yoshikawa M, Wakiji I, Hidai M, Uemura S, Chem. Eur. J 2005, 11, 1433–1451; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Hattori G, Sakata K, Matsuzawa H, Tanabe Y, Miyake Y, Nishibayashi Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 10592–10608; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an example of a Au allenylidene species generated from an alkyne by propargylic deprotonation, see:; i) Wei Y, Jiang J, Jing Y, Ke Z, Zhang L, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2024, 63, e202402286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Huang K, Sheng G, Lu P, Wang Y, J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 5294–5300; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang S, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Lu P, Org. Lett 2009, 11, 2615–2618; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhu Y, Yin G, Hong D, Lu P, Wang Y, Org. Lett 2011, 13, 1024–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Ammann SE, Rice GT, White MC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10834–10837; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang P-S, Liu P, Zhai Y-J, Lin H-C, Han Z-Y, Gong L-Z, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 12732–12735; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ammann SE, Liu W, White MC, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 9571–9575; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Qi X, Chen P, Liu G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 9517–9521; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Li C, Li M, Li J, Liao J, Wu W, Jiang H, J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 10912–10919; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Nelson TAF, Blakey SB, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 14911–14915; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Kazerouni AM, McKoy QA, Blakey SB, Chem. Commun 2020, 56, 13287–13300; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Wang H, Liang K, Xiong W, Samanta S, Li W, Lei A, Sci. Adv 2020, 6, eaaz0590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sharath N, Reddy KPJ, Arunan E, J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 5927–5938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Wang T, Zhou W, Yin H, Ma J-A, Jiao N, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 10823–10826; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cheng D, Bao W, J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 6881–6883; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Xie Y, Yu M, Zhang Y, Synthesis 2011, 2803–2809. [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Grigg RD, Rigoli JW, Pearce SD, Schomaker JM, Org. Lett 2012, 14, 280–283; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ju M, Zerull EE, Roberts JM, Huang M, Guzei IA, Schomaker JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 12930–12936; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lu H, Li C, Jiang H, Lizardi CL, Zhang XP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 7028–7032; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Scamp RJ, Jirak JG, Dolan NS, Guzei IA, Schomaker JM, Org. Lett 2016, 18, 3014–3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Hu S, Hager LP, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1998, 253, 544–546; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yeon Ryu J, Heo S, Park P, Nam W, Kim J, Inorg. Chem. Commun 2004, 7, 534–537; [Google Scholar]; c) Muzart J, Piva O, Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 2321–2324; [Google Scholar]; d) Shaw JE, Sherry JJ, Tetrahedron Lett. 1971, 12, 4379–4382. [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Chabaud B, Sharpless KB, J. Org. Chem 1979, 44, 4202–4204; [Google Scholar]; b) Hu S, Hager LP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 872–873. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nait Ajjou A, Ferguson G, Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 3719–3722. [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Alvarez LX, Christ ML, Sorokin AB, Appl. Catal. A 2007, 325, 303–308; [Google Scholar]; b) Chen P, Liu G, Catalytic Oxidation in Organic Synthesis, Vol. 2017/4, 1st edition ed., Georg Thieme; Verlag KG, Stuttgart, 2018; [Google Scholar]; c) Kropf H, Schröder R, Fölsing R, Synthesis 1977, 894–896; [Google Scholar]; d) Stephen Clark J, Tolhurst KF, Taylor M, Swallow S, Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 4913–4916. [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Wang Y, Zhu J, Durham AC, Lindberg H, Wang Y-M, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 19594–19599; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang Y, Zhu J, Guo R, Lindberg H, Wang Y-M, Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 12316–12322; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dey S, Charlack AD, Durham AC, Zhu J, Wang Y, Wang Y-M, Org. Lett 2024, 26, 3355–3360; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Scrivener S, Wang Y-M, Chem. Sci 2024, 15, 8850–8857; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zhu J, Durham AC, Wang Y, Corcoran JC, Zuo X-D, Geib SJ, Wang Y-M, Organometallics 2021, 40, 2295–2304. [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Waterman PS, Giering WP, J. Organomet. Chem 1978, 155, C47–C50; [Google Scholar]; b) Iyer RS, Selegue JP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 910–911; [Google Scholar]; c) Cron S, Morvan V, Lapinte C, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1993, 1611–1612; [Google Scholar]; d) Mahias V, Cron S, Toupet L, Lapinte C, Organometallics 1996, 15, 5399–5408. [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Eisch JJ, J. Organomet. Chem 1995, 500, 101–115; [Google Scholar]; b) Mao W, Fehn D, Heinemann FW, Scheurer A, van Gastel M, Jannuzzi SAV, DeBeer S, Munz D, Meyer K, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2022, 61, e202206848; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Morris RH, Chem. Soc. Rev 2024, 53, 2808–2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Kumar M, Reyes EA, Pannell KH, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2008, 361, 1793–1796; [Google Scholar]; b) Sponsler MB, Englich U, Ruhlandt K, Jung S-C, Ahn HG, Chung M-C, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol 2011, 11, 1534–1537; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Etzenhouser BA, Cavanaugh MD, Spurgeon HN, Sponsler MB, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 2221–2222; [Google Scholar]; d) Le Narvor N, Toupet L, Lapinte C, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 7129–7138; [Google Scholar]; e) Etzenhouser BA, Chen Q, Sponsler MB, Organometallics 1994, 13, 4176–4178; [Google Scholar]; f) Guillaume V, Mahias V, Mari A, Lapinte C, Organometallics 2000, 19, 1422–1426; [Google Scholar]; g) Guschlbauer J, Shaughnessy KH, Pietrzak A, Chung M-C, Sponsler MB, Kaszyński P, Organometallics 2021, 40, 2504–2515; [Google Scholar]; h) Mahias V, Cron S, Toupet L, Lapinte C, Organometallics 1996, 15, 5399–5408; [Google Scholar]; i) Sponsler MB, Organometallics 1995, 14, 1920–1927. [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Waterman PS, Giering WP, J. Organomet. Chem 1978, 155, C47–C50; [Google Scholar]; b) Chung M-C, Gu X, Etzenhouser BA, Spuches AM, Rye PT, Seetharaman SK, Rose DJ, Zubieta J, Sponsler MB, Organometallics 2003, 22, 3485–3494. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Substrates containing unprotected aniline and phenol were not compatible with the oxidative conditions of the coupling.

- [25].Substrates containing unprotected NH, OH and nitriles were not compatible with this reaction.

- [26].a) Zhan Z-P, Yu J-L, Liu H-J, Cui Y-Y, Yang R-F, Yang W-Z, Li J-P, J. Org. Chem 2006, 71, 8298–8301; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yin G, Zhu Y, Lu P, Wang Y, J. Org. Chem 2011, 76, 8922–8929; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yadav JS, Reddy BVS, Rao KVR, Kumar GGKSN, Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 5573–5576. [Google Scholar]

- [27].The detection of small amounts of solvent-trapping and elimination side products suggests that formation of the propargylic cation could be a minor reaction pathway (see the Supporting Information).

- [28].a) Durham AC, Wang Y, Wang Y-M, Synlett 2020, 31, 1747–1752; [Google Scholar]; b) Xia Y, Wang Y-M, α-C–H Functionalization of π-Bonds Using Iron Complexes. Handbook of CH-Functionalization, (Eds.: Maiti D), Wiley, 2022; [Google Scholar]; c) Durham AC, Liu CR, Wang Y-M, Chem. Eur. J 2023, 29, e202301195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].A radical clock experiemnt was conducted using 3-cyclopropyl-1-phenylprop-1-yne (see Supporting Information). The observation of products arising from cyclopropane ring opening suggests the formation of an intermediate with radical and/or cationic character at the propargylic position.

- [30].Rosenblum M, Waterman P, J. Organomet. Chem 1981,206, 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Deposition Number 2369300 (for 3at-2) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.