Abstract

Background

Despite the well‐known importance of witnessed arrest and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest outcomes, previous studies have shown significant statistical inconsistencies. We hypothesized an interaction effect and conducted stratified analyses to investigate whether witnessed arrest is more important than bystander CPR.

Methods

This study enrolled patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest between January 2010 and December 2022 in 3 emergency medical service (systems in Taiwan). Data were extracted from emergency medical service dispatch reports, including patient characteristics, witnessed arrest, bystander CPR, time for each dispatch, and prehospital interventions. The outcome measure was prehospital return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Patients were categorized into 4 groups: witnessed and bystander CPR present (W+B+), witnessed present but bystander CPR absent (W+B−), witnessed absent but bystander CPR present (W−B+), and witnessed and bystander CPR absent (W−B−). Multiple logistic regression on prehospital ROSC were performed in the 4 subgroups separately.

Results

A total of 14 737 patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest were identified, of whom 977 (6.6%) achieved prehospital ROSC. The W+B+ group exhibited the highest prehospital ROSC rate (14.0%). Stratification confirmed a statistically significant interaction between witnessed arrest and bystander CPR. Defibrillation, endotracheal intubation, and epinephrine administration were significantly associated with prehospital ROSC in all subgroups. Most explanatory variables significant in the witnessed arrest group were adjusted for in the nonwitnessed arrest group. Younger age was associated with prehospital ROSC only in the W+B+ group.

Conclusions

Witnessed arrest and bystander CPR may interact to predict prehospital ROSC in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest, with witnessed arrest likely having more significant impact on outcomes.

Keywords: bystander CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, return of spontaneous circulation, stratified analysis, witnessed arrest

Subject Categories: Cardiopulmonary Arrest, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiac Care

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- OHCA

out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest

- PAD

public access defibrillator

- ROSC

return of spontaneous circulation

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

The predictors of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest outcomes vary depending on the witnessed arrest and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation status, with traditional factors losing significance in cases of unwitnessed arrests.

Compared with bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation, witnessed arrest appears to have a more significant impact on outcomes.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Whether the patient experienced a witnessed arrest can assist clinicians in explaining potential outcome factors to families and in guiding postresuscitation care strategies.

Witnessed arrest and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are 2 variables of the Utstein‐style guidelines, which standardize the reporting of care processes and outcomes for patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). 1 , 2 For decades, these factors have been recognized as essential for the initial resuscitation of patients with OHCA. However, the individual roles of witnessed arrest and bystander CPR in influencing OHCA outcomes have been inconsistent across different studies.

Several studies predicting OHCA outcomes have demonstrated that witnessed arrest and bystander CPR are equally associated with short‐ 3 and long‐term outcomes. 4 , 5 Some studies have found that although both witnessed arrest and bystander CPR are indicators of good outcomes, the effect of bystander CPR diminishes in adjusted regression models. 6 , 7 Other studies have found that only witnessed arrest is associated with improvements in prehospital return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), 8 survival to hospital discharge, 9 , 10 and favorable neurological outcomes 11 ; however, the impact of bystander CPR remains unclear. Furthermore, Baldi et al. found that the positive effect of bystander CPR on survival to hospital admission was evident only in the presence of witnessed arrest. 12 These findings indicate that witnessed arrest appears to be critically important for determining OHCA outcomes.

Conversely, some studies have concluded that bystander CPR is more important than witnessed arrest in predicting patient outcomes after OHCA, particularly in regions with underdeveloped emergency medical service (EMS) systems. 13 Additionally, bystander CPR has been reported to have more significant impact on long‐term outcomes in studies involving survivors of OHCA. 14 , 15 These results suggest that bystander CPR could be an independent predictor of OHCA outcomes.

This inconsistency may originate from the potential interaction between witnessed arrest and bystander CPR. Moreover, the prevalence of witnessed arrest and bystander CPR may differ based on regional characteristics in Taiwan, such as medical resources or public knowledge, potentially influencing their impact on outcomes. 16 This study aimed to test the hypothesis that witnessed arrest and bystander CPR have a statistical interaction and further investigate which factors are more significantly associated with OHCA outcomes, considering these variations in regional EMS characteristics.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the National Taiwan University Hospital Hsin‐Chu Branch in Taiwan. The study included patients from 3 regions: Taipei City, the capital of Taiwan; Hsinchu City, a designated special municipality; and Hsinchu County. Taipei City and Hsinchu City are classified as metropolitan areas, whereas Hsinchu County, with its mountainous landscape and population primarily engaged in industrial and agricultural work, is considered a rural area. Taiwan's EMS system operates with a 2‐tiered structure. First, in Taipei City, at least 3 emergency medical technicians (EMTs), including an EMT‐paramedic, are dispatched for each OHCA incident, whereas in Hsin‐Chu City and Hsin‐Chu County, at least 2 EMTs are typically dispatched. EMT‐paramedics are not always available in these regions. Second, due to the relatively quick response times, first‐responder systems are not widely implemented across most areas. The EMTs are capable of providing advanced cardiovascular life support, including advanced airway management, intravascular catheterization, intraosseous catheterization, and epinephrine administration. The detailed characteristics of EMS systems are listed in Table S1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Taiwan University Hospital (Approval Nos. 202307016RINA, 202401013RINC and 202409087RINA). The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the study's retrospective nature.

Study Population

All EMS‐attended OHCA cases occurring between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2022, in Taipei City, Hsinchu County, and Hsinchu City, were included in our study. Patients younger than 18 years, with traumatic arrest, being witnessed arrest by the EMS and those with incomplete records of witnessed arrest, bystander CPR, and prehospital ROSC were excluded.

Data Collection, Cleansing, and Processing

The data for this study were collected directly from EMS dispatch reports. Each report, authored by EMTs, included comprehensive details such as patient demographics, dispatch timelines, and interventions performed. In the report, OHCA‐associated variables were designed and collected according to the Utstein style recommendations. The transition to digital recordkeeping began between 2010 and 2011, equipping EMTs with tablets for data entry during dispatches. These data were subsequently uploaded to an electronic database in PDF format. Before this period, the reports were manually written and archived on paper. To ensure data accuracy and consistency, 3 trained research assistants systematically collected information from various fire departments using a template with predefined variables and outcomes. Finally, the electronic and written records were consolidated into a single file. An independent data analyst conducted the data cleansing and statistical analyses. Records with missing variables or outcomes were excluded from the formal analysis.

Definitions of the Study Variables

Witnessed arrest and bystander CPR were the primary variables in our study. “Witnessed arrest” was defined as a cardiac arrest observed or heard by another individual. “Bystander CPR” refers to CPR performed by an individual not affiliated with the EMS system on an individual experiencing cardiac arrest. Additional covariates collected included patient‐related factors, such as age, sex, and preexisting diseases; event‐related factors, such as event location, and public access defibrillators attachment; and EMS‐related factors, such as prehospital time. Public access defibrillators attachment was defined as any attachment by a bystander, regardless of whether defibrillation was performed. The prehospital time was defined as the interval from the emergency call to their arrival at the hospital. EMS‐provided resuscitation efforts were also recorded. Automated external defibrillator (AED) attachment was defined as the placement of an AED by EMTs upon their arrival at the scene, with the number of defibrillations recorded separately. Upon confirming cardiac arrest, EMTs initiated manual chest compressions and transitioned to mechanical chest compressions before patient transport. Advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation interventions, such as endotracheal intubation and epinephrine administration, were also recorded.

Outcome

The outcome was prehospital ROSC, defined as the achievement of spontaneous circulation upon arrival at the hospital after treatment with EMS.

Statistical Analysis

All the variables were assessed based on their type and distribution. Descriptive statistics for continuous data were expressed as mean±SD, while categorical data were presented as count (percentage). Chi‐square tests were used to examine the differences in categorical variables between patients with and without ROSC, and 2‐sample t tests were used to assess the differences in continuous variables. Pearson's correlation coefficient evaluated associations between continuous variables, Cramer's V assessed associations between categorical variables, and the biserial correlation coefficient examined associations between continuous and categorical variables.

To test our hypothesis regarding the interaction between witnessed arrest and bystander CPR, we conducted a stratified analysis on these two variables. We divided the patients into 4 subgroups based on 2 predictors: witnessed arrest status and whether bystander CPR was performed. Initially, variables were screened and selected by emergency physicians based on previous studies and their potential impact on the outcome. Age and sex were the most common predictors for survival outcomes. 3 , 8 , 12 Hypertension and diabetes were the 2 most prevalent preexisting comorbidities before OHCA in Taiwan. 17 Cardiac arrest location was found to be associated with prehospital ROSC in several studies. 3 , 12 In Taiwan, mechanical chest compression was applied before EMTs transported the patients. Therefore, longer manual chest compression time may be influenced by the procedures performed on scene. Defibrillation during prehospital resuscitation were associated with good survival outcomes; however, defibrillation more than 3 times indicates a refractory case. 18 Prehospital epinephrine administration and endotracheal tube intubation may be positive predictors for survival. 8 , 19

We then performed univariate logistic regression analyses within each subgroup. Variables with a P value <0.1 in the univariate analysis were selected for inclusion in a multiple logistic regression model, resulting in a fully adjusted model. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% CIs were calculated, and Wald P values were reported for each variable in the logistic regression. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.2.

RESULTS

Patient Selection and Stratification

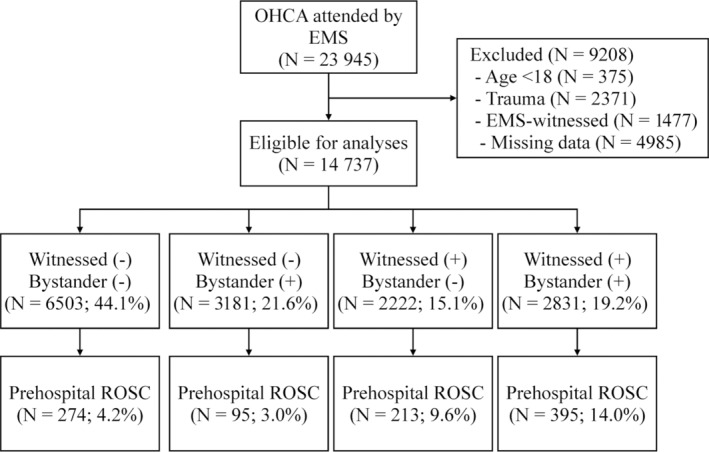

Figure 1 illustrates the patient flow chart. Between 2010 and 2022, 23 945 EMS‐attended OHCAs were preliminarily screened for eligibility. We excluded 9208 cases due to pediatric OHCA (n=375), traumatic arrest (n=2371), EMS witnessed (n=1477) and missing data (n=4985, listed in Table S2). The prehospital ROSC rates were 4.2%, 3.0%, 9.6%, and 14.0% in the witnessed and bystander CPR absent (W−B−), witnessed absent but bystander CPR present (W−B+), witnessed present but bystander CPR absent (W+B−), and witnessed and bystander CPR present (W+B+) groups, respectively.

Figure 1. Patient selection flow chart, illustrating stratification based on witnessed arrest and bystander CPR status: unwitnessed and no bystander intervention (W−B−), unwitnessed with bystander intervention (W−B+), witnessed but no bystander intervention (W+B−), and witnessed with bystander intervention (W+B+).

CPR, indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMS, emergency medical service; OHCA, out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest; and ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Comparison of Characteristics Between Patients With and Without Prehospital ROSC

Table 1 presents a comparison of the variables between patients with and without prehospital ROSC. Patients who achieved prehospital ROSC were generally younger and predominantly male than those who did not achieve prehospital ROSC. They were also less likely to have experienced OHCA events at home but more likely to be attached with a public access defibrillator.

Table 1.

Comparisons of Characteristics in Patients With OHCA With and Without Prehospital ROSC

| Variables | Prehospital ROSC | Non‐prehospital ROSC | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=977) | (n=13 760) | ||

| Age >65 y | 530 (54.3%) | 9567 (69.5%) | <0.01 |

| Sex, male | 660 (67.6%) | 8589 (62.4%) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 332 (34.0%) | 4430 (32.2%) | 0.26 |

| Diabetes | 194 (19.9%) | 2980 (21.7%) | 0.20 |

| OHCA location, household | 650 (66.5%) | 11 110 (80.7%) | <0.01 |

| Public automated defibrillator attached by bystander | 19 (1.9%) | 70 (0.5%) | <0.01 |

| Prehospital time, min | 22.2±6.6 | 22.9±8.0 | <0.01 |

| Manual chest compression time, min | 10.3±6.5 | 13.8±5.9 | <0.01 |

| Automated external defibrillator attached by emergency medical technician | 926 (94.8%) | 13 549 (98.5%) | <0.01 |

| Defibrillation count | <0.01 | ||

| 0 | 659 (67.5%) | 12 389 (90.0%) | |

| 1–2 | 248 (25.4%) | 977 (7.1%) | |

| ≥3 | 70 (7.2%) | 394 (2.9%) | |

| Endotracheal tube intubation | 153 (15.7%) | 962 (7.0%) | <0.01 |

| Epinephrine | 213 (21.8%) | 1839 (13.4%) | <0.01 |

| Witnessed arrest | 608 (62.2%) | 4445 (32.3%) | <0.01 |

| Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 490 (50.2%) | 5522 (40.1%) | <0.01 |

OHCA indicates out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest; and ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

The prehospital times were longer in the non‐prehospital ROSC group. Manual compression time was longer in patients without prehospital ROSC. Approximately one third of patients with prehospital ROSC received defibrillation, compared with <10% in the non‐prehospital ROSC group. Additionally, patients who achieved prehospital ROSC had higher rates of endotracheal intubation and epinephrine administration.

Patients with prehospital ROSC also had a significantly higher rate of witnessed arrest compared with those without ROSC (62.2% versus 32.3%, P<0.01) and a higher rate of bystander CPR (50.2% versus 40.1%, P<0.01).

Witnessed Arrest, Bystander CPR, and Their Interaction

Patients with witnessed arrest were younger and more male predominant than those without. However, there were no differences between age and sex in patients with and without bystander CPR. The detailed comparisons of characteristics between patients with and without witnessed arrest and bystander CPR are shown in Tables S3 and S4.

Table 2 shows the association between each variable and prehospital ROSC in the univariate analysis. A notable interaction was observed between witnessed arrest and bystander CPR. Compared with the W−B− group, patients in the W−B+ group had a significantly lower rate of prehospital ROSC. In contrast, patients in the W+B− and W+B+ groups had significantly higher rates of prehospital ROSC.

Table 2.

Univariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Variables on Prehospital ROSC

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age >65 y | 0.52 (0.46–0.59) | <0.01 |

| Sex, male | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 1.08 (0.95–1.24) | 0.25 |

| Diabetes | 0.90 (0.76–1.05) | 0.19 |

| Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest location, household | 0.47 (0.41–0.55) | <0.01 |

| Public automated defibrillator attached by bystander | 3.88 (2.33–6.47) | <0.01 |

| Prehospital time, min | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.01 |

| Manual chest compression time, min | 0.90 (0.89–0.91) | <0.01 |

| Automated external defibrillator attached by emergency medical technician | 0.28 (0.21–0.39) | <0.01 |

| Defibrillation (ref: no defibrillation) | ||

| 1–2 times | 4.77 (4.07–5.60) | <0.01 |

| ≥3 times | 3.34 (2.56–4.36) | <0.01 |

| Endotracheal tube intubation | 2.47 (2.05–2.97) | <0.01 |

| Epinephrine | 1.81 (1.54–2.12) | <0.01 |

| Witnessed arrest | 3.45 (3.02–3.95) | <0.01 |

| Bystander CPR | 1.50 (1.32–1.71) | <0.01 |

| Interactions (W−B− as reference group) | ||

| W−B+ | 0.70 (0.55–0.89) | <0.01 |

| W+B− | 2.41 (2.00–2.90) | <0.01 |

| W+B+ | 3.69 (3.14–4.33) | <0.01 |

W(+/−): with witnessed arrest /without witnessed arrest; B(+/−): with bystander CPR/without bystander CPR. CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OR, odds ratio; and ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Factors Associated With Prehospital ROSC: Stratification Analysis by Witnessed Arrest and Bystander CPR

In Table S5, the multiple logistic regression model for all patients shows that older age, a cardiac arrest occurring at home, AED attached by the EMT and longer durations of manual chest compressions were associated with a decreased likelihood of achieving prehospital ROSC. Conversely, factors such as extended prehospital time, defibrillation, endotracheal tube intubation, and administration of epinephrine were positively associated with a higher likelihood of prehospital ROSC. When compared with the W−B− group, patients in the W−B+ group had approximately half the likelihood of achieving prehospital ROSC (aOR, 0.60 [95% CI, 0.47–0.76]), whereas those in the W+B− (aOR, 1.85 [95% CI, 1.51–2.25]) and W+B+ groups (aOR, 2.28 [95% CI, 1.92–2.71]) had nearly double the likelihood of achieving prehospital ROSC.

Figure 2 illustrates the 4 multiple logistic regression models, presenting the association between various variables and prehospital ROSC. In the W−B− group, significant variables associated with a higher rate of prehospital ROSC included hypertension (aOR, 1.53 [95% CI, 1.18–1.98]), fewer minutes of manual chest compression (aOR, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.91–0.96]), being defibrillated 1 to 2 times (aOR, 3.71 [95% CI, 2.54–5.42]) and >3 times (aOR, 3.25 [95% CI, 1.70–6.23]), intubation (aOR, 2.37 [95% CI, 1.62–3.45]), and administration of epinephrine (aOR, 2.85 [95% CI, 2.06–3.93]). Similarly, in the W−B+ group, significant variables associated with a higher rate of prehospital ROSC included fewer minutes of manual chest compression (aOR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.83–0.90]) and being defibrillated 1 to 2 times (aOR, 3.75 [95% CI, 2.09–6.72]) or ≥3 times (aOR, 4.92 [95% CI, 2.05–11.83]) compared with no defibrillation, along with intubation (aOR, 3.84 [95% CI 2.06–7.17]), and administration of epinephrine (aOR, 1.93 [95% CI 1.07–3.47]). However, attaching AED by the EMT was associated with a lower rate of prehospital ROSC (aOR, 0.28 [95% CI 0.09–0.89]). No significant associations between other variables and prehospital ROSC were found after adjusting for confounders.

Figure 2. Multiple logistic regression.

This figure displays the adjusted odds ratios and 95% CIs for each variable after adjustment. A, unwitnessed and no bystander intervention; B, Unwitnessed with bystander intervention; C, Witnessed but no bystander intervention; D, Witnessed with bystander intervention. AED indicates automated external defibrillator; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; EMT, emergency medical technician; OHCA, out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest; and PAD, public automated defibrillator.

In the W+B− group, significant variables associated with a higher rate of prehospital ROSC included less manual chest compression time (aOR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.84–0.90]), defibrillation 1 to 2 times (aOR, 3.62 [95% CI, 2.49–5.25]) compared with no defibrillation, along with intubation (aOR, 4.24 [95% CI, 2.48–7.26]), and administration of epinephrine (aOR, 3.03 [95% CI, 1.86–4.91]). Similarly, in the W+B+ group, significant variables associated with a higher rate of prehospital ROSC included less manual chest compression time (aOR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.86–0.90]), no AED attached by the EMT (aOR 0.36 [95% CI, 0.22–0.61]), defibrillation 1 to 2 times (aOR, 3.19 [95% CI, 2.40–4.25]) and >3 times (aOR, 1.87 [95% CI, 1.22–2.86]), intubation (aOR, 3.24 [95% CI, 2.19–4.78]), and administration of epinephrine (aOR, 2.07 [95% CI, 1.46–2.93]). However, geriatric population was associated with a lower rate of prehospital ROSC (aOR, 0.46 [95% CI, 0.36–0.59]).

Correlation Analysis Between Variables in 4 Groups

Figure 3 illustrates the correlations between various associated factors under different circumstances in OHCA, categorized as W−B−, W−B+, W+B−, and W+B+. The correlation coefficients ranged from −0.18 to 0.57 in the W−B− group, −0.15 to 0.54 in the W−B+ group, −0.19 to 0.56 in the W+B− group, and −0.19 to 0.60 in the W+B+ group. Most variables presented weak correlations with each other.

Figure 3. Correlation matrix between variables in the 4 models: (A) W−B−, (B) W−B+, (C) W+B−, and (D) W+B+ groups.

Each panel presents the correlations of multiple variables on the x axis and the corresponding y axis, including endotracheal tube intubation, defibrillation count, AED attached by EMT, manual chest compression time, prehospital time, PAD attached by bystanders, OHCA location (household), diabetes, hypertension, sex (male), and age (>65 years). The color gradients in the figure indicate different levels of correlation, with darker shades representing stronger correlations. AED indicates automated external defibrillator; EMT, emergency medical technician; OHCA, out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest; and PAD, public automated defibrillator.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to apply stratified analysis to compare the effects of witnessed arrest and bystander CPR on OHCA outcomes, addressing a gap where previous studies have indirectly shown the interaction between these factors but rarely investigated them comprehensively. This method effectively eliminates potential statistical interactions. We included multiple EMS systems responsible for both metropolitan and rural areas, including regions with varying levels of medical resources. Additionally, we performed a complete data analysis without relying on data imputation, thereby avoiding bias. Our findings demonstrated that patients who experienced a witnessed arrest had a higher rate of prehospital ROSC, regardless of whether bystander CPR was administered. Additionally, this study established a statistically significant interaction between witnessed arrest and bystander CPR.

Explanations of Why Witnessed Arrest Would Be More Important

The current results support the hypothesis that witnessed arrest is more crucial than bystander CPR in OHCAs. First, witnessed arrest is the first and essential step in initiating the OHCA chain of survival because immediate recognition of the emergency and subsequent resuscitation follow a witnessed arrest. 20 In other words, when an arrest is witnessed, patients with OHCA receive prompt resuscitation, which terminates their cerebral no‐flow physiological status. Although bystander CPR could also reduce the no‐flow time in OHCA cases, it follows witnessed arrest as the second key factor. 21

Second, the actual no‐flow time is unknown in the real world if OHCA is not a witnessed arrest. A patient with OHCA may be unconscious several minutes after their physiological collapse, or they may be discovered without circulation hours or even days later. For instance, a patient may seem well before going to sleep but is found without a heartbeat and breathless when their family awakens in the morning. Clinically and theoretically, these patients have poor outcomes because their cells have already undergone irreversible death. Previous research has consistently shown that if the no‐flow time exceeds 20 minutes, the likelihood of achieving a favorable neurological outcome is minimal, even with bystander CPR or high‐quality resuscitation. 21

Third, in the witnessed‐arrest population, the previously used predictors for OHCA appear to be more rational and clinically practical. In this study, negative predictor of OHCA outcomes, such as older age, were significant only in the witnessed models (W+B− and W+B+). This may imply that patients without a witnessed arrest had poor outcomes regardless of age and cause. Baldi et al. found that the positive effect of bystander CPR on survival to hospital admission was significant only in the presence of witnessed arrest. 12 In addition, Jung et al. found that compared with nonwitnessed patients, the odds of OHCA survival in witnessed patients decreased rapidly as scene time increased, 5 which is consistent with current knowledge. However, this remains unknown in populations with nonwitnessed cardiac arrest.

Finally, the current resuscitation guidelines indicate that timely defibrillation improves survival in patients with shockable rhythms. 22 In our findings, attaching public access defibrillators by the bystander was associated with outcomes only in the W+B+ model, suggesting that witnessed arrest and subsequent bystander CPR facilitate timely defibrillation, thereby benefiting patients with shockable rhythms. A nonwitnessed patient might initially have a shockable rhythm, but without timely defibrillation, the cardiac rhythm may become nonshockable over time and eventually lead to a cardiac standstill. Therefore, witnessed arrest is also a key factor in this population.

The Impact of Sex and Prehospital Time on Prediction Models

Whether an OHCA is a witnessed arrest or involves bystander CPR may be influenced by the patient's sex. 23 In our study, the proportion of men was significantly higher in the witnessed arrest group compared with the nonwitnessed group (64.4% versus 61.9%, P<0.01). However, no significant difference in sex was found between patients who received bystander CPR and those who did not (61.7% versus 63.5%, P=0.07). The results of the sex‐specific sensitivity analyses are shown in Figures S1 and S2. In the male cohort, the models for witnessed arrests included more significant predictors, whereas fewer variables remained significant in models for nonwitnessed cases. In contrast, the models for the female cohort displayed similar variables regardless of witnessed arrest status or bystander CPR. These findings suggest that OHCA outcomes in men may be more influenced by witnessed arrest and bystander CPR compared with women.

Taiwan is a small country with a relatively high density of EMS and hospitals, resulting in shorter prehospital times. Therefore, the study's findings may not be generalizable to countries with longer prehospital times. To address this, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on OHCAs with the longest 20% of prehospital times (Figure S3). The average prehospital time in the subgroup was 33 minutes, compared with 22 minutes in the overall cohort. In this sensitivity analysis, we found that patients with longer prehospital time, models with witnessed arrest included more significant variables compared with those with nonwitnessed arrest. This suggests that in OHCA cases with potentially longer prehospital times, traditional variables and interventions may not be predictive of outcomes for patients without a witnessed arrest.

Echoes Between Previous Studies and Current Research Findings

Several studies on OHCA outcome prediction are consistent with our findings. For the prehospital ROSC score, bystander CPR was excluded from the model because it had a minimal impact on performance. 8 This study used the same outcome, prehospital ROSC, as our study, and ultimately identified 5 variables that were also significant in our model: age, response time, initial rhythm, prehospital epinephrine, and witnessed arrest. In the Utstein based‐ROSC model developed by Baldi et al., patients were stratified according to witnessed arrest and bystander CPR. Patients with witnessed arrest but without bystander CPR (W−B+) and those with bystander CPR but no witnessed arrest (W+B−) had similar prehospital ROSC rates (13.7% versus 13.2%). However, their effects on the model were opposite, with aORs of 0.59 versus 1.19, respectively. 12 These studies confirm the importance of witnessed arrest in cardiac arrest, particularly in EMS‐attended OHCA.

The importance of witnessed arrest and bystander CPR may exhibit a dynamic balance depending on their respective prevalence rates. The prevalence of witnessed arrest and bystander CPR can affect the predictability of OHCA outcomes. In regions with high rates of both witnessed arrest and bystander CPR, the predictive value of the outcomes may be diminished. For example, in a study in which the witnessed arrest rate was 89.3% and the bystander CPR rate was 72.7%, these variables were insignificant in predicting outcomes. 24 Conversely, in areas with low rates of witnessed arrest or bystander CPR, the importance of outcome predictions may be more pronounced. In a cohort with an underdeveloped EMS system and a bystander CPR rate of <5%, bystander CPR was more critical than witnessed arrest in predicting survival. 13 A study conducted in a rural area with a bystander CPR rate of 9% reported similar results. 25 The ROSC after cardiac arrest score was developed in a setting similar to that of our study, and bystander CPR was identified as a positive factor for ROSC, likely because of the low bystander CPR rate of only 14% in their cohort. 3

Clinical Implications and Practicability

Our findings may not directly alter current EMS procedures for OHCA rescues. Regardless of witnessed status or bystander CPR, the fundamentals—establishing an advanced airway, administering epinephrine, and defibrillating shockable rhythms—remain essential. For emergency physicians performing CPR on patients with OHCA, outcomes for those with witnessed arrests align with traditional predictors, including shorter response times, initial shockable rhythms and younger age. In contrast, for unwitnessed arrests, where no‐flow time is uncertain, outcome prediction becomes more probabilistic as many established factors lose significance in the model. Witnessed status may further aid physicians in explaining potential outcome factors to families and in guiding postresuscitation care strategies. For policymakers, our findings emphasize the importance of not only promoting bystander CPR but also strengthening surveillance for high‐risk individuals to facilitate earlier identification or detection of OHCA events.

Limitations

Our study has a few limitations. First, the retrospective design was subject to a selection bias owing to unintentionally missing data. The overall missing data rate in our study is 20.8%. Under the rapidly evolving and high‐stress environment of prehospital OHCA resuscitation, capturing all relevant variables can be challenging for EMTs, making some degree of missing data likely inevitable. However, for key variables such as prehospital ROSC, witnessed arrest, and bystander CPR, the missing rates were 8.7%, 7.5%, and 7.3%, respectively—levels that are within acceptable thresholds. (Table S2). Second, dispatch‐assisted CPR was not included in our study, which may result in an underestimation of the positive impact of bystander CPR on patient outcomes. However, as dispatch‐assisted CPR was initially introduced in Taiwan in 2019, its prevalence may not have been substantial during our study period. Third, the level and number of EMTs involved in each OHCA rescue were not documented, which could have affected the quality of prehospital resuscitation. 26 Finally, initial rhythm, an essential predictor of OHCA outcomes, was unavailable in our data set. Further investigations are required to explore the association between the number of defibrillations and OHCA outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Witnessed arrest and bystander CPR may have a statistical interaction in predicting prehospital ROSC for OHCA, with witnessed arrest potentially playing a more significant role in influencing outcomes. Our results provide a new perspective on the future promotion of wearable medical devices for the early detection of OHCA, thereby potentially increasing the rate of witnessed arrests.

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by the National Science and Technology Council (grant number: 112‐2314‐B‐002‐324) and the National Taiwan University Hospital Hsinchu Branch (grant number: 114‐HCH103).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S5

Figures S1–S3

This article was sent to Thomas S. Metkus, MD, PhD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.124.038427

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

Contributor Information

Charlotte Wang, Email: cywwang@ntu.edu.tw.

Chih‐Wei Sung, Email: chihweisung@ntu.edu.tw, Email: 114228@ntuh.gov.tw.

References

- 1. Idris AH, Bierens JJLM, Perkins GD, Wenzel V, Nadkarni V, Morley P, Warner DS, Topjian A, Venema AM, Branche CM, et al. 2015 revised Utstein‐style recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from drowning‐related resuscitation: an ILCOR advisory statement. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10:e000024. doi: 10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perkins GD, Jacobs IG, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, Bhanji F, Biarent D, Bossaert LL, Brett SJ, Chamberlain D, de Caen AR, et al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update of the Utstein resuscitation registry templates for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the international liaison committee on resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa, Resuscitation Council of Asia); and the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Circulation. 2015;132:1286–1300. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gräsner JT, Meybohm P, Lefering R, Wnent J, Bahr J, Messelken M, Jantzen T, Franz R, Scholz J, Schleppers A, et al. ROSC after cardiac arrest—the RACA score to predict outcome after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1649–1656. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hessulf F, Bhatt DL, Engdahl J, Lundgren P, Omerovic E, Rawshani A, Helleryd E, Dworeck C, Friberg H, Redfors B, et al. Predicting survival and neurological outcome in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest using machine learning: the SCARS model. EBioMedicine. 2023;89:104464. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jung E, Ryu HH, Ro YS, Shin SD. Association between scene time interval and clinical outcomes according to key Utstein factors in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32351. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000032351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahn JY, Ryoo HW, Moon S, Jung H, Park J, Lee WK, Kim J‐y, Lee DE, Kim JH, Lee S‐H. Prehospital factors associated with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest outcomes in a metropolitan city: a 4‐year multicenter study. BMC Emerg Med. 2023;23:125. doi: 10.1186/s12873-023-00899-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bae DH, Lee HY, Jung YH, Jeung KW, Lee BK, Youn CS, Kang BS, Heo T, Min YI. PROLOGUE (PROgnostication using LOGistic regression model for unselected adult cardiac arrest patients in the early stages): development and validation of a scoring system for early prognostication in unselected adult cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2021;159:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu N, Liu M, Chen X, Ning Y, Lee JW, Siddiqui FJ, Saffari SE, Ho AFW, Shin SD, Ma MH, et al. Development and validation of an interpretable prehospital return of spontaneous circulation (P‐ROSC) score for patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest using machine learning: a retrospective study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101422. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berdowski J, de Beus MF, Blom M, Bardai A, Bots ML, Doevendans PA, Grobbee DE, Tan HL, Tijssen JG, Koster RW, et al. Exercise‐related out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in the general population: incidence and prognosis. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3616–3623. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chai J, Fordyce CB, Guan M, Humphries K, Hutton J, Christenson J, Grunau B. The association of duration of resuscitation and long‐term survival and functional outcomes after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2023;182:109654. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2022.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pareek N, Kordis P, Beckley‐Hoelscher N, Pimenta D, Kocjancic ST, Jazbec A, Nevett J, Fothergill R, Kalra S, Lockie T, et al. A practical risk score for early prediction of neurological outcome after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: MIRACLE2. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:4508–4517. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baldi E, Caputo ML, Savastano S, Burkart R, Klersy C, Benvenuti C, Sgromo V, Palo A, Cianella R, Cacciatore E, et al. An Utstein‐based model score to predict survival to hospital admission: the UB‐ROSC score. Int J Cardiol. 2020;308:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma MH, Chiang WC, Ko PC, Huang JC, Lin CH, Wang HC, Chang WT, Hwang CH, Wang YC, Hsiung GH, et al. Outcomes from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in metropolitan Taipei: does an advanced life support service make a difference? Resuscitation. 2007;74:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin JJ, Huang CH, Chien YS, Hsu CH, Chiu WT, Wu CH, Wang CH, Tsai MS. TIMECARD score: an easily operated prediction model of unfavorable neurological outcomes in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest patients with targeted temperature management. J Formos Med Assoc. 2023;122:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2022.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nishioka N, Kobayashi D, Kiguchi T, Irisawa T, Yamada T, Yoshiya K, Park C, Nishimura T, Ishibe T, Yagi Y, et al. Development and validation of early prediction for neurological outcome at 90 days after return of spontaneous circulation in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2021;168:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fan CY, Sung CW, Chen CY, Chen CH, Chen L, Chen YC, Chen JW, Chiang WC, Huang CH, Huang EP. Updated trends in the outcomes of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest from 2017–2021: prior to and during the coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2023;4:e13070. doi: 10.1002/emp2.13070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sung CW, Chang HC, Fan CY, Chen CH, Huang EP, Chen L. Age, sex, and pre‐arrest comorbidities shape the risk trajectory of sudden cardiac death‐ patterns highlighted by population data in Taiwan. Prev Med. 2024;187:108102. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2024.108102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sakai T, Iwami T, Tasaki O, Kawamura T, Hayashi Y, Rinka H, Ohishi Y, Mohri T, Kishimoto M, Nishiuchi T, et al. Incidence and outcomes of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest with shock‐resistant ventricular fibrillation: data from a large population‐based cohort. Resuscitation. 2010;81:956–961. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kang K, Kim T, Ro YS, Kim YJ, Song KJ, Shin SD. Prehospital endotracheal intubation and survival after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: results from the Korean nationwide registry. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berg KM, Cheng A, Panchal AR, Topjian AA, Aziz K, Bhanji F, Bigham BL, Hirsch KG, Hoover AV, Kurz MC, et al. Part 7: Systems of Care: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142:S580–S604. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guy A, Kawano T, Besserer F, Scheuermeyer F, Kanji HD, Christenson J, Grunau B. The relationship between no‐flow interval and survival with favourable neurological outcome in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: implications for outcomes and ECPR eligibility. Resuscitation. 2020;155:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabanas JG, Donnino MW, Drennan IR, Hirsch KG, Kudenchuk PJ, Kurz MC, Lavonas EJ, Morley PT, et al. Part 3: adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142:S366–S468. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen CY, Fan CY, Chen IC, Chen YC, Cheng MT, Chiang WC, Huang CH, Sung CW, Huang EP. The interaction of sex and age on outcomes in emergency medical services‐treated out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: a 5‐year multicenter retrospective analysis. Resuscitation Plus. 2024;17:100552. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2024.100552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martinell L, Nielsen N, Herlitz J, Karlsson T, Horn J, Wise MP, Undén J, Rylander C. Early predictors of poor outcome after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care. 2017;21:96. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1677-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hung SC, Mou CY, Hung HC, Lai SW, Chen CC, Lin JW, Wang SH, Chen CK, Cheng KC. Non‐traumatic out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in rural Taiwan: a retrospective study. Aust J Rural Health. 2017;25:354–361. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sun JT, Chiang WC, Hsieh MJ, Huang EP, Yang WS, Chien YC, Wang YC, Lee BC, Sim SS, Tsai KC, et al. The effect of the number and level of emergency medical technicians on patient outcomes following out of hospital cardiac arrest in Taipei. Resuscitation. 2018;122:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S5

Figures S1–S3