Abstract

Plant cells are contained within a rigid network of cell walls. Cell walls serve as a structural material and a crucial signaling hub vital to all aspects of the plant life cycle. However, many features of the cell wall remain enigmatic, as it has been challenging to map its functional properties in live plants at subcellular resolution. Here, we introduce CarboTag, a modular toolbox for live functional imaging of plant walls. CarboTag uses a small molecular motif, a pyridine boronic acid, that directs its cargo to the cell wall. We designed a suite of cell wall imaging probes based on CarboTag in various colors for multiplexing. Additionally, we developed new functional reporters for live quantitative imaging of key cell wall characteristics: network porosity, cell wall pH and the presence of reactive oxygen species. CarboTag paves the way for dynamic and quantitative mapping of cell wall responses at subcellular resolution.

Subject terms: Plant cell biology, Fluorescence imaging

A suite of nontoxic and permeable CarboTag probes in various colors enables live quantitative imaging of a range of plant cell wall characteristics and dynamic, high-resolution mapping of cell wall changes in response to growth or perturbations.

Main

Plant cells are characterized by the presence of a carbohydrate-rich cell wall, which plays a key role in many processes along the life cycle of plants. It provides mechanical support to cells and tissues, mediates cell-to-cell communication and forms a signaling platform1,2. Plant cell walls are highly complex materials, formed from interpenetrating networks of various carbohydrates, whose properties and function are tailored by diverse glycoproteins, and contain numerous receptors for both chemical and physical signals3,4. Moreover, given its critical role in plant life, the maintenance of cell wall integrity and function is characterized by high genetic redundancy and many compensatory mechanisms2. Hence, studying the cell wall has proved to be difficult.

Fluorescence microscopy is an invaluable tool in the study of plant cell walls. Various fluorescent probes have been reported to bind different cell wall components, recently reviewed comprehensively in ref. 5. Alternatively, a range of antibodies for specific cell wall epitopes have been developed6, but their use requires fixation and cell wall permeabilization, thus precluding live imaging. Moreover, these probes and antibodies resolve localization but do not provide functional insights about cell wall properties nor dynamics. To this end, various genetically encoded cell wall biosensors for plants are reported, for example, to reveal apoplastic calcium, glutamate or pH levels7–9. While powerful, genetically encoded reporters require genetic access to the species of interest, which is not possible or difficult for many organisms in the green lineage.

Efforts to develop de novo functional chemical probes tailored to plants and their cell walls are absent. Chemical targeting requires the design of targeting groups that bind an epitope in the cell wall. In addition, chemical probes suitable for live-cell imaging are ideally of limited toxicity and capable of permeating multicellular tissues without requiring additional permeabilization. We aimed to develop a convenient targeting strategy that could be applied to all plants. Previously, we used the pectin-binding peptide from extensin proteins to target a functional probe to the cell wall in live tissue10. While successful, this approach is costly and resulted in low yields; the probes were unstable during prolonged storage and showed relatively slow tissue penetration due to the relatively large hydrodynamic size of the peptide. We thus set out to find a reliable chemical motif for targeting molecules of interest to the cell wall.

Here we describe the design of a modular dye toolbox for the live and functional fluorescence imaging of plant cell walls. It is centered around a de novo cell wall targeting motif, CarboTag, a small synthetic molecule that undergoes high-affinity binding with diols in the plant cell wall. CarboTag is minimally toxic, ensures rapid penetration into plant tissues and can deliver a range of water-soluble cargos to the cell wall. CarboTag allowed us to construct a range of cell wall fluorophores across the visible spectrum, based on readily available probes. Applying the same approach, we constructed chemical reporters for functional imaging of cell wall porosity, pH levels and reactive oxygen species (ROS). CarboTag offers a modular approach for the specific delivery of a range of cargos to the plant cell wall and opens the way for creating functional and dynamical maps of living plant cell wall networks with subcellular resolution.

Results

CarboTag

We took inspiration from the chemistry used by plants themselves for cell wall binding. Plants use the natural compound boric acid B(OH)3, which is used as a crosslinker for cell wall components11. Boric acid can bind cell walls based on the dynamic covalent bonding that a boronic acid, RB(OH)2, undergoes with diols present in saccharides, including cell wall carbohydrates. For a typical boronic acid or phenylboronic acid, the optimal pH to form a diol complex lies between pH 7 and 9 (ref. 12). As plant cell walls are generally acidic, with apoplastic pH levels ranging from four to eight under physiological conditions13, these motifs would only form very weak complexes with cell wall carbohydrates. By contrast, pyridinium boronic acids have been reported to form stable complexes in the correct acidic pH window14. Starting from commercially available 4-pyridinylboronic acid and propargyl bromide, we synthesized, in a two-step reaction, the structure we name CarboTag (Fig. 1a): a pyridinium boronic acid carrying a clickable alkyne group, suitable for conjugation to azide-functional fluorophores or other azide-carrying cargo, using click chemistry15. Click chemistry encompasses a range of modular chemical ligation strategies that occur with high yields under mild conditions, and give minimal side products.

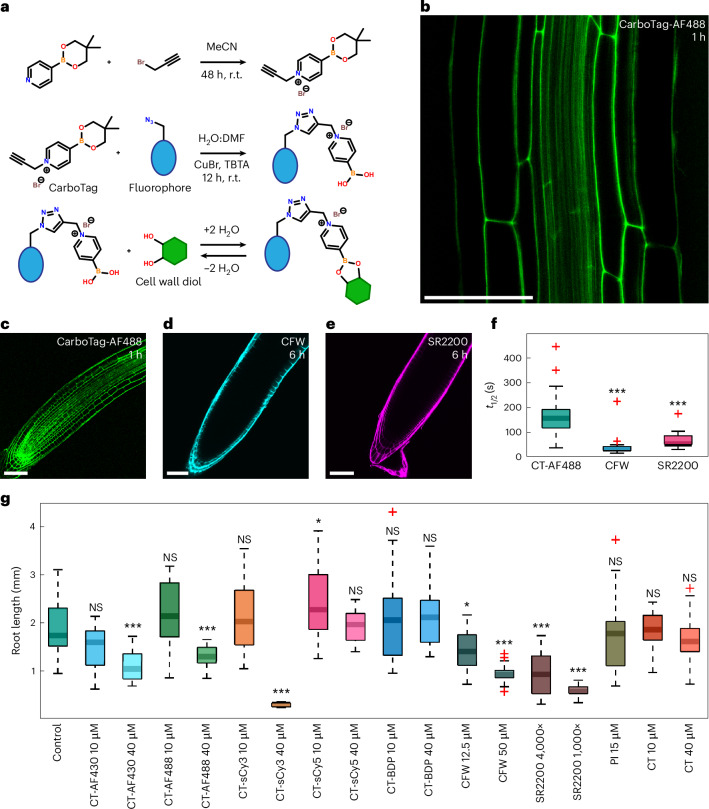

Fig. 1. CarboTag cell wall targeting.

a, Chemical route to synthesize CarboTag (top), CarboTag-modified dyes (middle) and chemical mechanism of forming reversible covalent bonds with diols (bottom). r.t., room temperature. b, A. thaliana root stained with CarboTag-AF488. c–e, Arabidopsis roots stained with CarboTag-AF488 (c), CFW (d) and Renaissance 2200 (SR2200) (e), with incubation times indicated in the panels. f, Timescale of FRAP, performed in Arabidopsis root hairs, for CarboTag-AF488 (CT-AF488, n = 29), CFW (n = 22, P = 0.000000017) and Renaissance 2200 (n = 12, P = 0.000022). g, Toxicity test of CarboTag-modified dyes (CT-AF430, CT-AF488, CT-sCy3, CT-sCy5 and CT-BDP), conventional cell wall dyes (CFW, SR2200 and PI) and pure CarboTag (CT). Stratified seeds are grown and germinated in liquid medium containing different concentrations (as indicated) of probes; root length was measured after 7 days, data represents at least n = 14 independent measurements. Exact P values compared to control: CT-AF430 10 µM, P = 0.091; CT-AF430 40 µM, P = 0.0000060; CT-AF488 10 µM, P = 0.074; CT-AF488 40 µM, P = 0.00027; CT-sCy3 10 µM, P = 0.39; CT-sCy3 40 µM, P = 0.00000015; CT-sCy5 10 µM, P = 0.49; CT-sCy5 40 µM, P = 0.048; CT-BDP 10 µM, P = 0.75; CT-BDP 40 µM, P = 0.30; CFW 12.5 µM, P = 0.014; CFW 50 µM, P = 0.00000026; SR2200 4,000×, P = 0.000021; SR2200 1,000×, P = 0.00000010; PI 15 µM, P = 0.54; CT 10 µM, P = 1.00; CT 40 µM, P = 0.24. In box plots the center line is the median, box bounds represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers span from the smallest to the largest data points not considered outliers. Red + symbols indicate outliers. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; NS, P > 0.05; two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. Scale bars represent 50 µm (b–e).

Next, we synthesized a fusion of CarboTag to AlexaFluor488 to give the CarboTag-AF488 probe. Live Arabidopsis thaliana stained with CarboTag-AF488 for 30 min show excellent staining of the root cell wall network, even deep inside the tissue (Fig. 1b). As a control, we incubated seedlings with the unmodified AF488, lacking the CarboTag targeting group, which did not result in any detectable cell wall staining (Supplementary Fig. 1). We also confirmed that CarboTag targets the cell wall exclusively, and does not result in membrane insertion, by performing a plasmolysis experiment on a CarboTag-AF488 stained seedling. Plasmolyzed roots show highly stained cell walls, and a complete lack of fluorescence signal in the plasma membrane (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Next, we benchmarked CarboTag to the current state-of-the-art. We compared tissue permeation kinetics of CarboTag-AF488 with that of CalcoFluor White (CFW), Renaissance SR2200 and propidium iodide (PI), three commonly used cell wall stains5, in live Arabidopsis seedlings. Both CFW and SR2200 brightly stain the root epidermis after several hours but their penetration into the tissue is limited (Fig. 1d,e and Supplementary Fig. 3). We observe a similar lack of staining with PI when using isotonic 0.5 Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium; PI staining improved substantially when using pure water as the staining medium, which is, however, hypotonic and thus imposes an osmotic stress on the tissue. Moreover, prolonged staining with PI, within 1 h, leads to internalization of the dye and staining of the nucleus, and we observe severe signs of toxicity resulting from PI staining (Supplementary Fig. 4).

By contrast, CarboTag-AF488 fully penetrates the root in as little as 15–30 minutes and reaching full staining intensity in 1 h (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Fig. 7). After 24 h, CFW and SR2200 only had a marginal increase in penetration (Supplementary Fig. 3). More importantly, roots exposed to CFW and SR2200 for 24 h began to display signs of cytotoxicity, such as aberrant cell swelling (Supplementary Fig. 3q,r), which are absent for CarboTag-AF488 (Supplementary Fig. 3p). The de novo CarboTag-based cell wall probe thus permeates tissues more rapidly and efficiently compared to the state-of-the-art cell wall probes.

The more rapid permeation of CarboTag compared to CFW and SR2200 could hint at a lower binding affinity to its cell wall epitope. To test whether a weaker binding is responsible for the more rapid tissue permeation of our dye, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments on these three probes in A. thaliana root hairs that were stained well by all probes. From the FRAP measurements, we extracted the characteristic timescale for fluorescence recovery and used this as a relative measure of the diffusion rate of the probes in the apoplastic space16. Both CFW and SR2200 diffuse more rapidly, indicated by a low recovery timescale, when compared to CarboTag-AF488, which has a slower fluorescence recovery (Fig. 1f). This difference in diffusion kinetics suggests that CarboTag binds the cell wall more strongly compared to CFW and SR2200.

Multicolor plant cell wall imaging

Existing cell wall fluorophores encode their cell wall binding and fluorescence properties within the same chemical structure. As a result, there is only limited spectral flexibility in choosing a cell wall probe, which can be challenging in multiplexing experiments with plants that express a genetically encoded fluorescent reporter.

CarboTag can turn any azide-carrying and water-soluble fluorophore into a cell wall stain. Advances in dye chemistry have resulted in an enormous diversity of fluorophores that can be commercially procured with an azide modification. To demonstrate the versatility of CarboTag, we selected probes across the visible spectrum based on coumarin (AF430), sulfo-rhodamine (AF488) and cyanine (sulfo-Cy3 and sulfo-Cy5) chemistries. Despite their different chemical nature (Supplementary Fig. 1), all CarboTag fusions stain the root tip tissues of of A. thaliana seedlings within 1 h (Fig. 2a–c) and exclusively stain the cell wall with no measurable membrane insertion detected (Supplementary Fig. 2).

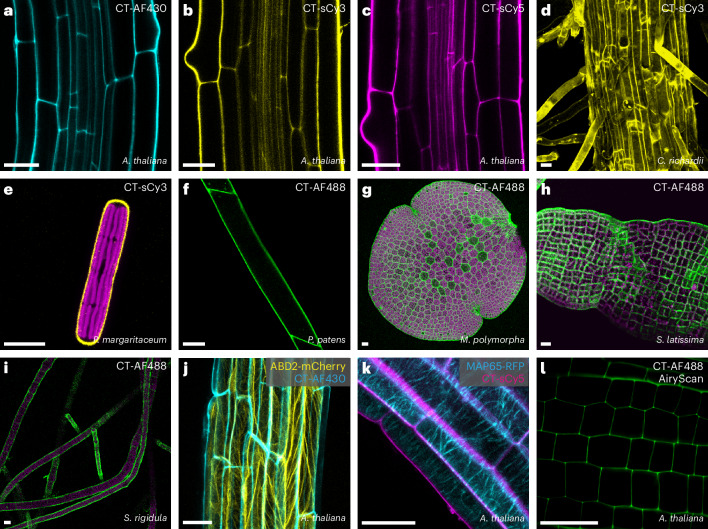

Fig. 2. Multicolor CarboTag dyes function in plants and algae the green lineage.

a–c, A. thaliana roots stained with CarboTag-modified AF430 (a), sulfo-Cy3 (b) and sulfo-Cy5 (c) that cover the emission spectrum from blue-green to far red. d, Root of the fern C. richardii stained with CarboTag-sCy3. e, A single algal cell stained with CarboTag-sCy3, chloroplasts autofluorescence in magenta. f, Caulonema of the moss P. patens stained with CarboTag-AF488. g, Gemma of the liverwort M. polymorpha stained with CarboTag-AF488, chloroplast autofluorescence in magenta. h,i, CarboTag-AF488 staining of brown algae: S. latissima (h) and S. rigidula (i), chloroplast autofluorescence in magenta. CarboTag dyes for multiplexed imaging. j,k, CarboTag-AF430 (cyan) with actin marker ABD2-mCherry (yellow) (j) and CarboTag-sCy5 (magenta) with microtubule marker MAP65-RFP (cyan) (k), both in Arabidopsis root tissues. l, AiryScan super-resolution imaging of Arabidopsis root meristem stained with CT-AF488. Scale bars in all images represent 25 µm.

Access to a wide spectral range of cell wall stains facilitates multiplexed live imaging with existing plant lines that express genetically encoded fluorescent markers. We demonstrate this by combining CarboTag cell wall probes with fluorescent protein reporters for actin (ABD2-mCherry, Fig. 2j) and microtubules (MAP65-RFP, Fig. 2k). In addition, CarboTag-based probes are suited for higher-resolution imaging such as AiryScan imaging (Fig. 2l).

CarboTag is compatible with a wide diversity of plant species: we performed in a green algae (Penium margaritaceum), a fern (Ceratopteris richardii), a moss (Physcomitrium patens) and a liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha). Cell walls of all these species could be stained with CarboTag-based probes (Fig. 2d–g). This also indicates that the epitope that CarboTag binds is present in all plant species and green algae, even though their cell wall composition varies substantially17. We also tested the capacity of CarboTag to stain the pectin-rich mucilage that surrounds Arabidopsis seeds just after hydration, and find it stains this structure very well, revealing intricate fibrillar structures in the seed mucilage (Extended Data Fig. 1).

Extended Data Fig. 1. Arabidopsis seed coats stained with CarboTag dyes.

Arabidopsis seeds stained for 2 h with 40 µM CT-sCy3 (a–c) and 10 µM CT-sCy5 (d–f). Images a-e are average intensity projections of Z stacks, image f is a maximum intensity projection of a z-stack. Scale bars represent 25 µm.

We also tested the staining of organisms outside the plant lineage that feature a saccharide-rich cell wall. We found that CarboTag could not stain the cell wall of bacteria, an example of Escherichia coli is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, nor oomycetes (Phytophthora palmivora, Supplementary Fig. 6). CarboTag does not generally bind all diols, as there are many diol-containing polysaccharides and glycans present in the cell walls of these species. Since the oomycete cell wall contains cellulose18, this compound is not the CarboTag target. Thus, pectin is likely the epitope that is bound in green plants, as pectin is missing in the organisms we could not stain. We then tested whether CarboTag could target cell walls of several species of brown algae; both Saccharina latissimi (Fig. 2h) and Saccharina latissidula (Fig. 2i) showed excellent staining with CarboTag-AF488, with the cell outlines clearly visible. The cell wall of brown algae lacks pectin and is mostly composed of alginates. Moreover, we observed that CarboTag stained agar-containing media and gels. We thus conclude that CarboTag binds hydrated carbohydrate hydrogels consisting of polymers (pectin, agar, alginate), where the diol groups are readily accessible for binding.

To determine the toxicity of CarboTag-based probes, we germinated and grew A. thaliana seeds in liquid medium containing CarboTag and CarboTag-based probes, at identical concentrations used for imaging experiments. We compared root length between treated and untreated controls after 7 days of exposure as a metric of developmental toxicity. CarboTag-based probes show no cytotoxicity at 10 μM (Fig. 1j). At 40 μM, exposure for 7 days leads to small but significant reductions in root growth for all CarboTag-based probes, except for the red-emitting CarboTag-Cy3 that we found to be significantly cytotoxic at 40 μM. Since the CarboTag motif itself is not toxic at this same dose, we attribute this to the Cy3 probe itself. Moreover, at 10 μM, CarboTag-based probes are significantly less toxic compared to currently used alternatives. Even though root growth is relatively weakly affected by PI staining, we observe morphological defects in roots exposed to PI for 24 h (Supplementary Fig. 4).

To confirm that lower concentrations (10 μM and below) would still result in adequate staining, we stained Arabidopsis roots for 1 hour at a range of concentrations of the CarboTag-based probes. Good staining is achieved at 10 μM for all probes, and for most probes, lower concentrations (5 or even 1 μM) suffice (Extended Data Fig. 2). This can be considered in the design of long-term imaging experiments to ensure the absence of cytotoxic effects. To demonstrate compatibility with long-term time-lapse imaging, we recorded time-lapse sequences of germinating seeds, stained with CarboTag-AF488, over a period of several days (Extended Data Fig. 3).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Arabidopsis roots stained with probes at different concentrations.

Roots were stained for 1 h with 40 µM, 10 µM, 5 µM and 1 µM of CT-AF430 (a, 40 µM; b, 10 µM; c, 5 µM; d, µM), CT-AF488 (e1-2, 40 µM; f1-2, 10 µM; g1-2, 5 µM; h1-2, 1 µM), CT-sCy3 (i1-2, 40 µM; j1-2, 10 µM; k1-2, 5 µM; l1-2, 1 µM), CT-sCy5 (m1-2, 40 µM; n1-2, 10 µM; o1-2, 5 µM; p1-2, 1 µM) and CT-BDP (q1-2, 40 µM; r1-2, 10 µM; s1-2, 5 µM; t1-2, 1 µM). Imaging settings were not constant but adjusted to get optimal signal during every measurement. Scale bars represent 25 µm.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Timelapse of an Arabidopsis seed stained with CT-AF488 germinating.

Images were taken immediately after plating on solid 0.5x MS (a), after 2 days (b), 3 days (c–e) and 4 days (f–h). on t = 3 days the testa rupture is visible (c), the emerging radical tip was imaged using higher magnification (d, e). On t = 4 days the first root hairs are visible (f–h). All images are maximum intensity projections of z-stacks. Scale bars represent 25 µm.

Cell wall porosity: CarboTag-BDP

The primary cell wall of plant cells is a complex composite that must sustain enormous internal turgor pressures while also accommodating cell expansion, growth and tissue remodeling3,19. This requires cell walls to be mechanically dynamic and plastic structures. We previously reported that a phenyl-BODIPY (boron dipyrromethene) (BDP) molecular rotor probe, coupled to a pectin-binding peptide, could be used to probe changes and defects in cell wall network structure, which can affect their mechanical resilience10,20. The BDP rotor, undergoes an intermolecular rotation on photoexcitation to a nonradiative, dark state. This physical motion requires fluid to flow around the molecule, coupling the molecular rotation hydrodynamically to its surroundings. This results in a BDP fluorescence lifetime that is low when the BODIPY probe rotates freely, for example in aqueous media, and high when the probe rotation is severely hindered21. This feature allows the mapping of the mechanical environment of the dye with fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM). In the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 7) we show that the quantity that is probed is in fact the mesh size, or porosity, of the pectin network in the cell wall, and thus an indirect measure for the pectin levels in the cell wall space.

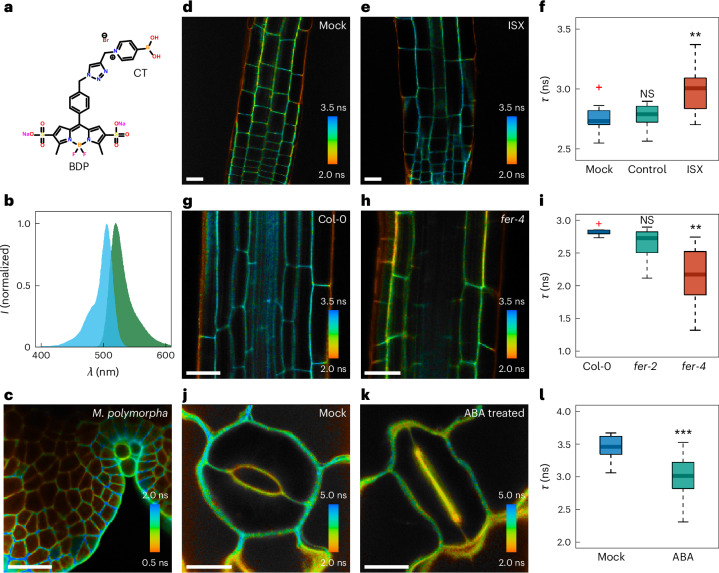

We coupled BDP to CarboTag (Fig. 3a,b) and the resulting probe CarboTag-BDP showed clear wall localization (Fig. 3c). To demonstrate its responsiveness to cell wall porosity, we manipulate the composition of the cell walls by inhibiting cellulose synthase with isoxaben (ISX). Arabidopsis seedlings grown on a solid medium containing ISX showed stunted growth and increased osmosensitivity22,23. Simultaneously, ISX treatment leads to increased levels of de-esterified pectin, and in some cases lignin, as a possible rescue response resulting in a denser meshwork in the cell wall23,24. We indeed find that cell walls in plants treated with ISX show a significantly higher lifetime of the CarboTag-BDP probe compared to both the control and mock-treated seedlings (Fig. 3c–e and Supplementary Fig. 8). A higher lifetime indicates a more hindered intramolecular rotation, hence an increased density of the pectin network in the cell walls whose cellulose biosynthesis was inhibited. In this analysis, the outer epidermal walls were excluded as those walls have consistently very low lifetimes, likely due to probe quenching by chemical interactions with components in root surface layer.

Fig. 3. CarboTag-based cell wall porosity imaging.

a, Chemical structure of CarboTag-BDP porosity probe. b, Normalized excitation (cyan) and emission (green) spectra of CarboTag-BDP. c, FLIM of a M. polymorpha gemma stained with CarboTag-BDP. d,e, FLIM images of mock-treated (DMSO, d) and ISX-treated (e) Arabidopsis seedling roots. f, Corresponding comparison of mean fluorescence lifetimes of cell walls in the root elongation zone excluding the epidermal cell wall (main text): mock (DMSO, n = 11), control (H2O, n = 8, P = 0.55) and treated (ISX, n = 18, P = 0.0015). g,h, FLIM images of Arabidopsis roots stained with CarboTag-BDP in wild-type (Col-0, g) and FERONIA loss-of-function mutant fer-4 (h). i, Comparison of mean fluorescence lifetimes in the root cell walls, excluding the outer epidermal cell walls, in these lines including fer-2: Col-0 (n = 8), fer-2 (n = 12, P = 0.082) and fer-4 (n = 12, P = 0.00033). j,k, FLIM images of opened (Control, j) and closed (ABA-treated, k) stomata in Arabidopsis leaves. l, Comparison of fluorescence lifetimes between opened (mock) and closed (ABA-treated) guard cell walls: mock (n = 12) and treated (ABA, n = 12, P = 0.00073). Color scale in FLIM images corresponds to the fluorescence lifetime. In box plots the center line is the median, box bounds represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers span from the smallest to the largest data points not considered outliers. Red + symbols indicate outliers. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, P > 0.05; two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. Scale bars in all images represent 25 µm.

As the cell wall is a vital structure to many processes, its integrity is continuously monitored by a complex cell wall integrity (CWI) maintenance pathway2,25. A central player in CWI is FERONIA (fer), a pleiotropic pectin-binding receptor-like kinase26,27. Loss-of-function fer mutants show compromised CWI, resulting in accelerated root growth, spontaneous cell bursting and hypersensitivity to osmotic stress26–28. The phenotype can be rescued by embedding the tissue in a stiffer agar gel26. This suggests that FER mutants have weakened cell walls that have difficulties in sustaining internal turgor unless supported by an exterior scaffold. However, AFM indentation experiments on FER mutants did not show a difference in the cell wall elasticity27. Since cellulose microfibrils dominate cell wall stiffness, FER mutants appear unaffected in cellulose levels and the origins of their mechanical problems lie elsewhere.

We performed FLIM-based porosity imaging of cell walls in fer-2 and fer-4 loss-of-function mutants stained with CarboTag-BDP. Mutant lines reveal significantly increased cell wall porosity, that is, lower lifetimes than the wild-type control (Fig. 3f–h and Supplementary Fig. 9). The fer-4 line shows a more severely affected cell wall porosity, consistent with reports of a stronger root growth phenotype in fer-4 versus fer-2 (ref. 28). Moreover, we find that the porosity of the fer mutants is notably more heterogeneous compared to wild-type, indicated by the width of the lifetime distributions (Fig. 3h). Given that our probe is sensitive to porosity at the nanometric scale, these changes likely reflect reduced pectin density and increased cell wall inhomogeneity in fer mutants.

Finally, we demonstrate that CarboTag-based porosity imaging is not limited to roots. First, we created lifetime-based porosity maps of gemmae of M. polymorpha; we can observe that young cell walls that surround the meristem in the apical notch are substantially less porous (higher lifetime) compared to matured cell walls, which is consistent with the notion that pectin-rich walls just after division are progressively enriched with cellulose as they mature10. Second, we mapped the cell wall porosity in the guard cells that make up stomata in the Arabidopsis leaf before and after closure induced by the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA). Stomatal closure involves the physical motion of these two cells to form an actuating aperture. We observe a significantly lower lifetime in the guard cells’ outer walls compared to those before ABA-triggered closure (Fig. 3j–i). This illustrates how the actuation of stomata involves reversible physical changes to the cell wall.

Apoplastic pH: CarboTag-OG

Plant cell growth requires the rigid cell wall to yield from the inflationary pressure of cellular turgor. In the ‘acid growth’ theory, this is mediated by an acidification of the apoplast, which activates expansins, a family of cell wall loosening proteins, resulting in cell walls with increased extensibility29. The plant signaling molecule auxin controls growth by activating processes that acidify the apoplast, including the upregulation of proton pump synthesis and the activation of proton pumps by rapid phosphorylation through a noncanonical auxin signaling pathway30,31. Pathogens are also known to manipulate cell wall pH levels, most likely to loosen the cell wall and reduce the mechanical resistance to tissue colonization32,33.

A commonly used approach to quantify apoplastic pH relies on the pH-sensitive ratiometric dye 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (HPTS)34. However, HPTS is not only a pH reporter, but also a potent photo-acid, releasing protons on illumination with the light required for imaging, thereby altering the pH as one tries to measure it35. HPTS illumination is even reported to result in strong cytotoxicity36. Alternatively, proton-sensitive dyes, such as fluorescein dye, are suspended in the medium to measure the pH at the surface of the plant tissue30,37. These approaches measure pH at the surface of the root, thus detecting protons exuded from the plant. To measure the pH inside the cell wall, genetically encoded pH reporters for the cell wall have been described9,38. All existing approaches have an intensity-based or ratiometric read-out, which makes the measurements sensitive to local changes in probe concentration and chromatic artifacts due to light scattering.

We use CarboTag to construct a FLIM-based apoplastic pH sensor, by coupling it to an Oregon Green (OG) fluorophore (Fig. 4a,b), with a reported pKa of 4.8. In vitro, the fluorescence lifetime of CarboTag-OG shows a distinct sigmoidal change with varying pH (Fig. 4c). The fact that OG can be used as a pH sensor with a lifetime-based read-out was reported previously39 but not yet exploited in biological imaging. CarboTag-OG selectively targets the cell wall with the same staining kinetics (Fig. 4d,e), while free OG, without a CarboTag anchor internalizes in the cells and shows no apoplastic localization (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Fig. 4. CarboTag-based cell wall pH imaging.

a, Chemical structure of the CarboTag-OG pH probe. b, Normalized excitation (cyan) emission (green) spectrum of CarboTag-OG. c, Mean fluorescence lifetime of CarboTag-OG in 0.5× MS with different pH values. d,e, FLIM images of a root with the 4 tissue types indicated (d) and a root tip (e). f, Comparison of mean fluorescence lifetimes observed in the root meristem (MS, n = 10, PTZ = 0.017, PEZ = 0.85, PDZ = 0.017), transition zone (TZ, n = 10, PEZ = 0.045, PDZ = 0.00018), elongation zone (EZ, n = 10, PDZ = 0.0.0022) and differentiation zone (DZ, n = 10). g,h, FLIM images of nontreated roots (g) and roots treated with IAA (h) after 10 min. i, Comparison of mean fluorescence lifetimes observed in the epidermis–cortex elongation zone cell wall between mock (DMSO, n = 12) treated, nontreated (control, n = 20, P = 0.40), auxin (IAA, n = 17, P = 0.035), fusicoccin (FC, n = 24, P = 0.015) and benzoic acid (BA, n = 8, P = 0.62) treated seedlings. In box plots the center line is the median, box bounds represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers span from the smallest to the largest data points not considered outliers. Red + symbols indicate outliers. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, P > 0.05; two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. Scale bars represent 25 µm.

FLIM maps of roots of Arabidopsis seedlings show that the fluorescence lifetime, and hence apoplastic pH, is lower in the elongation zone of the root compared to the root tip and maturation zone (Fig. 4d–f), which corresponds to the picture of acid growth theory. It is important to note that lifetime measurements performed in aqueous solutions of varying pH (Fig. 4c) cannot be used as a quantitative calibration curve, as the local chemical microenvironment in the apoplast, which influences the fluorescence lifetime of these probes, is far more complex than that in a simple buffer solution. The pH–lifetime response curve can be used to evaluate the relative amplitude of pH variations within an experiment. We estimate, based on the data in Fig. 4c, that the change of pH in the elongation zone, with respect to the root tip meristem, is ΔpH −1.1, while the change in pH between transition and elongation zone is ΔpH −0.4. The growth of the plant cells in the elongation zone is accompanied by significant acidification.

Next, we subjected roots, prestained with CarboTag-OG, to treatment with 1 μM of the natural auxin indole 3-acetic acid (IAA), which activates proton pumps through phosphorylation30,31 or 10 μM fusicoccin. This fungal toxin activates H+ ATPases33. Both treatments are thought to lead to the efflux of protons from cells into the apoplast, resulting in rapid acidification. Indeed, the median fluorescence lifetime, analyzed in the epidermis–cortex cell wall, after 10 min of exposure to auxin or fusicoccin, is significantly lower compared to untreated control roots (Fig. 4g–i and Supplementary Fig. 11). Based on the curve in Fig. 4i, we calculate the amplitude of the induced acidification to be ΔpH −0.22 for auxin treatment and ΔpH −0.31 for fusicoccin treatment. Roots subjected to benzoic acid, a molecule with similar acidity and size to IAA but with no biological function, did not result in a decrease in fluorescence lifetime.

ROS generation in the cell wall: CarboTag-Ox

ROS are key signaling components in a large diversity of physiological processes ranging from development to wounding responses40,41. Reactive oxygen also plays an antimicrobial role in plant defenses, where ROS bursts are among the earliest responses of plant cells to pathogen recognition41. Moreover, ROS acts as a chemical reagent, for example in crosslinking extensin glycoproteins in the cell wall4,42. Various approaches, based on colorimetric staining, oxidation-sensitive fluorophores or genetically encoded biosensors, are reported to resolve ROS generation inside the cytosol, mitochondria or membranes of plant cells43,44. However, ROS in the apoplast itself has remained impossible to detect directly, while this is where ROS serves its function in crosslinking cell wall compounds and where it is delivered after pathogen perception. Moreover, the role of the apoplast in ROS perception is emerging through the putative oxidative modification of cysteine residues in the extracellular domains of CRRKs45–49.

Our attempt to create an apoplastic ROS reporter for plants began by selecting the ROS reactive probe BODIPY 581/591 C11 (Fig. 5a). This probe features a BODIPY core, whose conjugated system is extended by a phenyl butadiene tail with two reactive sites for oxidation. In its native state, this extended pi-conjugated system emits in the red range. On oxidation of the tail, the conjugated system is shortened, shifting the emission to the green range. Due to its hydrophobic nature, this probe localizes to cellular plasma membranes50.

Fig. 5. CarboTag-based cell wall ROS imaging.

a, Chemical structure of CarboTag-Ox apoplastic ROS probe. b, Normalized excitation (yellow) and emission (orange) spectrum of nonoxidized CarboTag-Ox. c–e, Time lapse of CarboTag-Ox stained Arabidopsis roots treated with exogenous ROS at t = 0 (c), t = 0.5 h (d) and t = 1 h (e). The color corresponds to the fraction of oxidized probe of the total fluorescence signal (oxidized + nonoxidized). Nonoxidized and oxidized signal are shown separately in magenta and cyan, respectively. f–h, Time lapse of CarboTag-Ox ROS probe-stained Arabidopsis roots treated with flg22 at t = 0 (f), t = 0.5 h (g) and t = 1 h (h). Color corresponds to the fraction of oxidized probe of the total fluorescence signal (oxidized + nonoxidized). Nonoxidized and oxidized signal are shown separately in magenta and cyan, respectively. Scale bars represent 100 µm (c–e) and 25 µm (f–h), respectively.

Fusion of BODIPY C11 directly to CarboTag results in a probe that targets cell walls, but due to its amphiphilic nature also showed substantial membrane insertion (Supplementary Fig. 12). To reduce membrane insertion, and hence increase the specificity of cell wall localization, we introduced a hydrophilic spacer between the probe and the CarboTag motif. This resulted in the probe we name CarboTag-Ox (Fig. 5a,b). This modification reduced membrane insertion, although it did not completely prevent it (Supplementary Fig. 12). Based on the fluorescence intensity between membrane and cell wall following plasmolysis, we estimate that ~70% of the signal in cells originates from the cell wall (Supplementary Fig. 12).

To validate CarboTag-Ox, we exposed prestained plants to ROS generated in the medium through a so-called Fenton’s reaction. Before ROS exposure, the probe emits purely in the red range, indicative of little to no oxidation, resulting in a red-to-green intensity ratio of close to zero (Fig. 5c). Over the course of 1 hour, we observed ROS activating the probe, first in the root tip (Fig. 5d) and spreading over the entire root (Fig. 5e), visible as an increasing red-to-green ratio, indicative of progressive oxidation of CarboTag-Ox. Next, we treated plants with the flagellin peptide flg22, which is perceived by the Arabidopsis FLS2 (Flagellin Sensitive 2) receptor as a signature of a potential pathogenic threat51. The resulting pattern-triggered immune response involves generating a ROS burst, as a defensive countermeasure52. Before treatment, we observe little to no oxidation of the CarboTag-Ox probe (Fig. 5f). Treatment with flg22 results in ROS production in the epidermis (Fig. 5g), which spreads over time to the cortical cells inside the root (Fig. 5h). By contrast, roots subjected to a mock treatment show minimal oxidation of the ROS sensor (Supplementary Fig. 13). This shows that CarboTag-Ox can resolve the kinetics of ROS action in cell walls, in response to a pathogen signal, with live whole-mount imaging.

Discussion

We presented CarboTag, a small cell wall targeting molecular motif, as the basis for a modular toolbox for live and functional imaging of plant cell wall networks. In this work we showed how CarboTag can specifically localize any water-soluble fluorophore to the cell wall of various plants, which appears independent of the precise chemical make-up of the cargo.

Advantages

Compared to the state-of-the-art, our CarboTag approach offers several advantages. The probes permeate tissues rapidly, without requiring potentially stressing permeabilization agents. They are nontoxic, while currently used stains for live-cell imaging of cell walls show severe toxicity phenotypes. Given the flexibility of the modular platform, cell wall stains can be constructed in any color or with any desired spectral features, which makes them ideal for multiplexing experiments. Moreover, they allowed us to construct probes for functional imaging of cell wall properties that are applicable to a wide range of plants and brown algae species without the need for genetic manipulation of the organism of interest.

Limitations

The required incubation time for good tissue staining appears to be independent of the ‘cargo’ that is attached to the targeting motif but is sensitive to the tissue type, plant species and dye concentration. At 40 μM, Arabidopsis seedling roots show staining of the vasculature in as little as 15 min, while at 10 μM it may require up to 1 hour. Lower probe concentrations are feasible (Extended Data Fig. 2), but depending on the tissue may require longer staining. While A. thaliana roots, fern roots and brown and green algae accept the stains rapidly (30–60 min), some tissues and species were more challenging. Gemmae of M. polymorpha and thalli of C. richardii (Supplementary Fig. 14) took up to 6 h, or overnight, to stain at 40 μM. Lateral root primordia, before emergence, in Arabidopsis could not be stained at all with CarboTag-based probes (Supplementary Fig. 14). We speculate that the presence of barrier layers, such as a thick cuticle on the surface of gemmae and thalli, reduces the rate of probe uptake and that the root cap, which is established to cover the lateral root primordium53, prevents uptake of these, by design, very hydrophilic dyes. This is further confirmed by an experiment in which we observe staining along the length of the root and find that at the maturation zone, where the Casparian strip begins to close, the probe no longer penetrates the vasculature (Extended Data Fig. 4). The use of CarboTag-based probes in plant species and tissue types that we have not yet tested, especially those featuring cuticles or apoplastic barriers, may thus require optimization and could, in some cases, be challenging without adding permeabilizing agents.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Arabidopsis roots stained with CT-AF488 show no increased penetration into the vasculature over time.

Maximum intensity projections of roots stained with 10 µM CT-AF488 after 30 min (a), 1 h (b), 2 h (c) and 3 h (d). Scalebars represent 100 µm.

The FLIM-based reporters for cell wall porosity and pH are designed to be responsive to their local environment. As a result, these types of probe are generally solvatochromic, that is, sensitive to their local chemical environment. This has several consequences for their use in in vivo imaging. We observed that lifetime values for CarboTag-BDP and CarboTag-OG in the outer wall of root epidermal cells, at the root-medium surface, are consistently below the lowest lifetime for the probe in calibration media. This is indicative of probe quenching in these walls by chemical interaction with some, yet unidentified compound, which hinders analysis of the outer root surface. Similar effects were, in exploratory experiments, seen around tissue sites infected with pathogens or nematodes, where we believe they may be due to damage-associated compounds such as ROS or lignin precursors54,55.

A second consequence of the solvatochromism of many lifetime-based fluorescent reporters is that their quantitative calibration in vitro is difficult. The chemical microenvironment in the complex plant cell wall is intrinsically very different from that in simple solutions, making a quantitative mapping from simple experiments to in vivo results unreliable. For example, for the apoplastic pH probe CarboTag-OG, we performed lifetime measurements as a function of pH in aqueous solutions. Lifetime values of the same probes in planta would suggest apoplastic pH levels that are remarkably more acidic than those reported previously34,37. Whether this is the result of solvatochromism due to the cell wall microenvironment that shifts the lifetime–pH curve or due to inaccuracy in reported values, we cannot distinguish at this point. Out of caution, we have avoided converting our lifetime imaging results for this probe into absolute pH units and have used it as a tool to reveal relative acidification patterns and responses on treatment. In general, we feel that great caution should be exercised in using calibrations for these types of probe performed in simple solutions to measurements performed in the complex environment of living cells.

Outlook

We speculate that CarboTag can be used beyond what was reported here, and we envision extensions of this approach for functional mapping of other cell wall properties in the future, such CarboTag fusions to specific reporters for calcium, other ionic species or redox states. More hydrophobic cargo results in amphiphilic molecules that show a propensity for inserting into the membrane as well as binding the cell wall; this can be overcome to some extent by the introduction of a hydrophilic spacer, thereby extending the range of possibilities of this targeting strategy. One can also think beyond fluorescent probes and sensors, as CarboTag can theoretically also deliver bio-active signals into the cell wall to prevent their internalization in the cell; this could be a valuable tool to discriminate between the apoplastic and intercellular signal perception of, for example, hormones. Finally, we have shown that CarboTag probes can be used at low doses without posing toxicity issues during prolonged exposure, making it feasible to perform long-term imaging experiments (Extended Data Fig. 3). This opens the way to mapping physicochemical changes in the plant cell wall during developmental processes.

Methods

Additional information, including extensive chemical synthesis protocols, chemical structures (Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16), fluorescence spectra (Supplementary Fig. 17) and chemical analysis (Supplementary Figs. 18–28), is provided in the Supplementary Information.

General synthesis of CarboTag fluorophores

CarboTag-fused fluorophores were prepared from commercially available azide functionalized dyes through copper-catalyzed azide alkyne cycloaddition. Coupling reactions took place in 1:2 water:dimethylformamide mixtures with CuBr and tris(benzyltriazolylmethyl)amine as catalyst and ligand, respectively. After an overnight reaction, the resulting solution was diluted with water and filtered using a 0.45-μm syringe filter. The resulting solution was lyophilized and redissolved in water. Extensive synthetic protocols and chemical analyses are reported in the Supplementary Information.

Imaging

Imaging experiments were performed on a Leica TCS SP8 inverted confocal microscope coupled to a pulsed white light laser at a 40-MHz repetition rate, except for the experiments on brown algae that were performed on a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope. CarboTag-AF488, CarboTag-BDP (porosity probe) and CarboTag-OG were excited with a 488-nm line. Fluorescence was captured between 500 and 550 nm using a hybrid detector. CarboTag-sCy3 and CarboTag-sCy5 were excited with 548- and 646-nm lines, respectively. Fluorescence was detected between 558 and 608 nm (CarboTag-sCy3) and 656 and 706 nm (CarboTag-sCy5) using a hybrid detector. CarboTag-Ox was simultaneously excited with 488- and 581-mm laser lines, both at 5% laser power, to excite the oxidized and nonoxidized form of the probe, respectively. Fluorescence was captured simultaneously between 500 and 550 nm for the oxidized form and between 591 and 641 nm for the nonoxidized form using hybrid detectors in photon counting mode. MAP65-RFP was excited with a 561-nm laser line. Fluorescence was captured between 570 and 615 nm using a hybrid detector. ABD2-mCherry was excited with a 585-nm laser line. Fluorescence was captured between 600 and 650 nm using a hybrid detector. For CarboTag-AF430 we used a 440-nm diode pulsed laser (40 MHz) and fluorescence was captured between 500 and 550 nm. Fluorescence was captured through a ×10 (numerical objective (NA) 0.3) dry objective or a ×63 (NA 1.2) water immersion objective depending on the sample type.

Ratiometric measurements performed with CarboTag-Ox were processed in ImageJ v.1.52. For both the oxidized (green) and nonoxidized (red) channels, the background signal was removed. The pixel values of these two images were corrected for their backgrounds. Subsequently, the resulting pixel values were added up and corrected pixel values of the green channel were divided by the pixel values of the combined image. The resulting 32-bit image had pixel values between 0 and 1, which indicated the fraction of total signal originating from the oxidized (green) channel. This fraction is displayed in a 16-color scale.

FLIM experiments using CarboTag-BDP and CarboTag-OG were performed on a Leica TCS SP8 inverted confocal microscope coupled to a Becker-Hickl SPC830 time-correlated single photon counting module. An excitation line of 488 nm was used and fluorescence was captured between 500 and 550 nm using a hybrid detector. Acquisition times were between 60 and 120 s depending on signal strength were used to obtain an image of 256 × 256 pixels. Resulting FLIM images were processed in SPCImage v.8.5 software to obtain two-component exponential decay curves for every pixel. Measurements involving M. polymorpha were fitted with a 2–22-ns two-component exponential tail fit. FLIM images are presented in a false-color scale that represents the mean fluorescence lifetime per pixel in nanoseconds.

Super-resolution imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM880 inverted laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with an AiryScan detector and a 488 nm argon laser. Fluorescence was captured between 495 and 550 nm, AirySscan deconvolution was performed in Zeiss ZEN software.

Comparison CT-AF488 versus CFW and SR2200

Five-day old Arabidopsis seedlings were incubated in a 12-well plate in 0.5× MS with 40 μM CarboTag-AF488, a 1,000× diluted Renaissance 2200 (SR2200) stock solution (from supplier) or a 20× diluted CFW solution (from a 1 g l−1 solution). The well plate was covered with and left on a plate shaker at 60 rpm. Seedlings were taken out after 15 min, 30 min, 60 min, 3 h, 6 h and 2 h, washed with clean 0.5× MS and imaged. Imaging was performed on a Leica SP8 multiphoton system with a pulsed Coherent Chameleon Ti:sapphire laser. CarboTag-AF488 was excited with a 980-nm line, and the fluorescence was captured between 500 and 570 nm using a hybrid detector. Both SR2200 and CFW were excited with the two-photon laser at 810 nm and the fluorescence was captured between 420 and 500 nm using a hybrid detector. Fluorescence for all three dyes was captured through a ×40 (NA 1.10) water immersion objective.

Penetration of CT-AF488 into vasculature tissue

Five-day old Arabidopsis seedlings were incubated in a 12-well plate in 0.5× MS with 10 μM CarboTag-AF4d88 for 30 min, 1 h, 2 h and 3 h. After incubation seedlings were washed with clean 0.5× MS and imaged on a Leica SP8 multiphoton system with a pulsed Coherent Chameleon Ti:sapphire laser. CarboTag-AF488 was excited with a 980-nm line, fluorescence was captured through a ×40 (NA 1.10) water immersion objective between 500 and 600 nm using a hybrid detector. Using the navigator option in the Leica LAS X software multiple z-stacks were made starting from the tip going upward until no more fluorescence was observed in the vasculature. The maximum intensity projections from the obtained z-stacks were stitched together in LAS X software.

FRAP

Five-day old Arabidopsis seedlings were incubated in 0.5× MS with 40 μM CarboTag-AF488, a 1,000× diluted Renaissance 2200 (SR2200) stock solution (from supplier) or a 20× diluted CFW solution (from a 1 g l−1 solution). FRAP experiments were performed on a Nikon C2 CLSM with an argon laser using a 60× (NA 1.40) oil immersion objective and Nikon NIS-Elements AR v.5.21.03 acquisition software. CarboTag-AF488 was excited with a 488-nm argon laser line, fluorescence was captured between 500 and 550 nm using a photomultiplier detector. Both SR2200 and CFW were excited with a 405-nm line, fluorescence was detected between 417 and 477 nm using a photomultiplier detector. FRAP was performed by selection of a bleach region of interest and a reference region of interest on root hairs with the same size for all measurements. A series of images were taken as a prebleach (three images, 8-s intervals) where the laser power and detector gain were balanced to have a minimal number of saturated pixels. Bleaching was performed by increasing the laser power to 80–100% depending on the sample for 5-s intervals in a small region of interest. Following bleaching, a time-lapse sequence was taken at a frame rate of 0.13 fps. The fluorescence recovery in the bleach spot was normalized and corrected against the reference region to correct for imaging-induced photobleaching. The resulting data was fitted with a single exponential fit in MATLAB R2021b to extract the half-time of recovery by using the maximum intensity value after bleaching as the plateau value56.

Plant growth

A. thaliana wild-type, fer-2 and fer-4 mutants were surface sterilized by washing them in a 50% ethanol solution, followed by a wash in 70% ethanol and a 100% ethanol solution (5 min per solution). The sterilized seeds were dried for 1 h before storage. Sterilized seeds were put on half strength (0.5×) MS plates and placed at 4 °C overnight before placing them vertically under long-day growth conditions (16 h light, 8 h dark) for 5 days. Five-day old seedlings were transferred to 0.5× liquid MS medium containing 40 μM of the CarboTag dyes, except for CarboTag-Ox that was kept at 10 μM. Seedlings were incubated for 1 h and washed in fresh 0.5× MS medium for 1 min and transferred to a glass slide with 0.5× MS medium before imaging. Osmotic shock treatments were performed by placing the seedlings on a glass slide with a 0.5 M mannitol solution instead of 0.5× MS medium.

A. thaliana seeds were surface sterilized by washing them in a 50% ethanol solution, followed by a wash in 70% ethanol and a 100% ethanol solution (5 min per solution). The dried seeds were transferred to liquid 0.5× MS supplemented with 40 μM CT-sCy3 or 10 μM CT-sCy5. Seeds were incubated 2 h before imaging.

C. richardii spores (Hn-n strain) were sterilized and grown as previously describe in a Hettich MPC600 plant growth incubator set at 28 °C, with 16 h of 100 μmol m−2 s−1. Plants were grown on 0.5× MS medium supplemented with 1% sucrose. Gametophytes were grown from spores and synchronized by imbibing the spores in the dark in water for >4 days. Sporophytes were obtained by flooding plates containing sexually mature gametophytes with water. Sporophytes used for imaging were 3–4 weeks old. Samples were incubated with 40 μM of CarboTag dye for 6 h in 0.5× MS and washed with 0.5× MS for 1 min before imaging.

P. margaritaceum NIES 217 cells were grown in Woods Hole Medium for 15 days) at 20 °C with long-day conditions, 30–50 µmol m−2 s−1 light and with continuous agitation (60 rpm, 50-ml flasks). Liquid cultures with an optical density at 750 nm (OD750) of 0.2–0.3 were used for imaging experiments. After incubating with 40 μM of CarboTag dye for 6 h, cells were centrifuged at 27g for 1 min. Cells were transferred to fresh 0.5× MS and imaged.

S. latissima fragmented gametophytes were inoculated in Provasoli enriched sea water (PES) under low light conditions (16 μmol m−2 s−1), a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle at 13 °C. We transferred material to normal light conditions (50 μmol m−2 s−1) after 6 days, PES medium was changed every 7 days. Samples were incubated with 10 μM CarboTag dye for 12 h and 90 min, washed three times with sea water for >30 min and imaged.

S. rigidula male gametophytes were cultivated in PES at 16 °C with a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle. Photon irradiation was 30 μmol m−2 s−1 (white light spectrum). Samples were incubated with 10 μM CarboTag dye for 12 h and 90 min, washed three times with sea water for >30 min and imaged.

M. polymorpha was grown on B5 medium under continuous light (40 μmol m−2 s−1) at 25 °C. Gemma were isolated using a 200-μl pipet tip, incubated with 40 μM CarboTag dye in 0.5× MS for 6 h and washed for 1 min in clean 0.5× MS before imaging.

P. patens was grown on BCDAT medium under continuous light (40 μmol m−2 s−1) at 25 °C. Samples were incubated with 40 μM CarboTag dye, washed with 0.5× MS for 1 min and imaged.

Time-lapse imaging of seed germination

To an Ibidi eight-well chamber slides with a 1.5 polymer coverslip, 100 μl of molten 0.5× MS gel was added per well. Once the gel solidified, one sterilized Col-0 seed was added per well. Staining was performed by adding 25 μl of a 10 μM CT-AF488 solution on the seeds. After incubating for 1 h, the seeds were washed with 3× 50 μl of clean liquid 0.5× MS. This staining and washing procedure was repeated before every imaging session. Imaging was performed immediately after putting the seeds on the gel (t = 0), afterwards seeds were stratified overnight. Imaging was performed on a Leica SP8 multiphoton system with a pulsed Coherent Chameleon Ti:sapphire laser. CarboTag-AF488 was excited with a 980-nm line, fluorescence was captured through a ×10 (NA 0.3) dry objective or a ×40 (NA 1.10) water immersion objective between 500 and 600 nm using a hybrid detector.

Toxicity test

The toxicities of the CarboTag and CarboTag-modified dyes were compared to those of conventional cell wall dyes. Stratified seeds were placed in tightly sealed 24-well plates containing 1 ml of liquid 0.5× MS supplemented with 10 and 40 μM of CT-AF430, CT-AF488, CT-sCy3, CT-sCy5, CT-BDP or pure CarboTag. The toxicity of conventional cell wall dyes was determined using concentrations of 12.5 and 50 μM for CFW, 15 μM for PI, 1,000× and 4,000× dilutions from stock for SR2200. Root lengths were measured after 7 days.

Chemical treatments

ISX

ISX-treated seedlings were generated by supplementing melted 0.5× MS gel with 3 nM ISX from a 5 mM stock in DMSO. Sterilized seeds were plated, and placed at 4 °C overnight followed by putting the plates vertically under long-day growth conditions for 5 days before staining and imaging. A mock treatment was performed by adding an equal amount of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) without ISX to melted 0.5× MS gel.

ABA

Five-day old seedlings were stained with 40 μM CT-BDP and simultaneously treated with 10 μM ABA from a 5 mM stock in DMSO for 1 h to induced stomata closure. A mock treatment was performed by adding 0.2% DMSO without ABA.

Fusicoccin

Five-day old seedlings were stained with 40 μM CarboTag-OG for 1 h and transferred to a microscopy slide with unbuffered 0.5× MS supplemented with 10 μM fusicoccin from a 5 mM stock in DMSO. Five lots of 2-min continuous FLIM measurements were taken immediately afterward. A mock treatment was performed by placing seedlings in unbuffered 0.5× MS with 0.2% DMSO during imaging.

Auxin

Five-day old seedlings were stained with 40 μM CarboTag-OG for 1 h and transferred to a microscopy slide with unbuffered 0.5× MS supplemented with 1 μM auxin from a 5 mM stock in DMSO. Five lots of 2-min continuous FLIM measurements were taken immediately afterward. A mock treatment was performed by placing seedlings in unbuffered 0.5× MS with 0.2% DMSO during imaging.

Benzoic acid

Five-day old seedlings were stained with 40 μM CarboTag-OG for 1 h and transferred to a microscopy slide with unbuffered 0.5× MS supplemented with 1 μM benzoic acid from a 5 mM stock in DMSO. Five lots of 2-min continuous FLIM measurements were taken immediately afterward.

Flg22

Seedlings were stained with 10 μM CarboTag-Ox for 1 h, transferred to 5 ml of 0.5× MS containing 1 μM flg22 and vacuum infiltrated for 5 min. Seedlings were removed from this mixture before imaging. Mock treatment was performed by placing seedlings in 0.5× MS under vacuum for 5 min.

ROS

Seedlings were stained with 10 μM CarboTag-Ox for 1 h and transferred to a microscopy slide with freshly prepared 0.5× MS supplemented with 5 μM hemin from a 1 mM stock in DMSO and 2 mM cumene peroxide from a 500 mM stock in ethanol. Images of single roots were taken at 15-min intervals for 1 h.

Statistics and reproducibility

Replicates represent data obtained from distinct samples. The statistical method used to determine significance between datasets was a two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test (rank sum), which was performed in MATLAB R2021b. Exact P values for Figs. 1f,g, 2f,i,l and 4f,i are reported in their respective legends

The numbers of independing experiments in the Extended Data figures are as follows: Extended Data Fig. 1an = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 1bn = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 1cn = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 1dn = 3, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 1en = 3, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 1fn = 3, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2an = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2bn = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2cn = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2dn = 1, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2e(1,2) n = 4, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2f(1,2) n = 3, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2g(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2h(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2i(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2j(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2k(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2l(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2m(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2n(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2o(1,2) n = 1, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2p(1,2) n = 1, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2q(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2r(1,2) n = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2s(1,2) n = 1, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 2t(1,2) n = 1, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 3an = 2, two independent experiments; Extended Data Fig. 3bn = 2, two independent experiments; Extended Data Fig. 3cn = 2, two independent experiments; Extended Data Fig. 3dn = 2, two independent experiments; Extended Data Fig. 3en = 2, two independent experiments; Extended Data Fig. 3fn = 1, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 3gn = 1, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 3hn = 1, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 4an = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 4bn = 2, one independent experiment; Extended Data Fig. 4cn = 2, one independent experiment and Extended Data Fig. 4dn = 2, one independent experiment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41592-025-02677-4.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figs. 1–28.

Source data

Statistical source data and P values.

Statistical source data and P values.

Statistical source data and P values.

Source data fluorescence spectrum.

Acknowledgements

This work and J.S. and M.B. are funded by the European Research Council project Catch, project number 101000981. The work of B.C. is funded by the European Research Council project ALTER e-GROW, project number 101055148. Views and opinions expresses are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. We gratefully acknowledge valuable discussions, suggestions, probe testing and the supply of plant material by A. Daamen, S. Martin Ramirez, S. Woudenberg, P. Carillo Carrasco, M. de Roij, T. Niault, A. Malivert, B. Landrein, R. van Ineveld, J. Guerreiro, P. Marhavy, A. Chevalier and T. Hamann.

Extended data

Author contributions

M.B. and J.S. established the CarboTag concept. M.B., J.S., J.W.B. and D.W. designed the experiments and contributed to data interpretation. M.B. and M.H. designed and performed the synthesis of the CarboTag motif. M.B. synthesized all CarboTag-based probes and performed all in planta experiments. Imaging experiments on brown algae were performed by B.C. L.M. performed the sulfoBDP lifetime-viscosity experiment. J.S., J.W.B. and D.W. supervised the project. M.B., J.S. and J.W.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Methods thanks Jinxing Lin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Rita Strack, in collaboration with the Nature Methods team.

Data availability

The raw data associated with the figures in this paper are publicly available at 10.4121/3464fadd-ccb8-4a6c-9463-e3014bcdf984. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code developed to process and analyze data in this paper are publicly available at 10.4121/3464fadd-ccb8-4a6c-9463-e3014bcdf984.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41592-025-02677-4.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41592-025-02677-4.

References

- 1.Zhang, B. et al. The plant cell wall: biosynthesis, construction, and functions. J. Integr. Plant Biol.63, 251–272 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaahtera, L., Schulz, J. & Hamann, T. Cell wall integrity maintenance during plant development and interaction with the environment. Nat. Plants5, 924–932 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delmer, D. et al. The plant cell wall—dynamic, strong, and adaptable—is a natural shapeshifter. Plant Cell36, 1257–1311 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moussu, S. & Ingram, G. The EXTENSIN enigma. Cell Surf.9, 100094 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piccinini, L., Nirina Ramamonjy, F. & Ursache, R. Imaging plant cell walls using fluorescent stains: the beauty is in the details. J. Microsc.295, 102–120 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhertbruggen, Y. et al. An extended set of monoclonal antibodies to pectic homogalacturonan. Carbohydr. Res.344, 1858–1862 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao, D. et al. Self-reporting Arabidopsis expressing pH and [Ca2+] indicators unveil ion dynamics in the cytoplasm and in the apoplast under abiotic. Stress Plant Physiol.134, 898–908 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toyota, M. et al. Glutamate triggers long-distance, calcium-based plant defense signaling. Science361, 1112–1115 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreau, H., Gaillard, I. & Paris, N. Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors adapted to acidic pH highlight subdomains within the plant cell apoplast. J. Exp. Bot.73, 6744–6757 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michels, L. et al. Complete microviscosity maps of living plant cells and tissues with a toolbox of targeting mechanoprobes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA117, 18110–18118 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matoh, T. Boron in plant cell walls. Plant Soil193, 59–70 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan, J. et al. The relationship among pKa, pH, and binding constants in the interactions between boronic acids and diols—it is not as simple as it appears. Tetrahedron60, 11205–11209 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gámez-Arjona, F. M., Sánchez-Rodríguez, C. & Montesinos, J. C. The root apoplastic pH as an integrator of plant signaling. Front. Plant Sci.13, 931979 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohler, L. K. & Czarnik, A. W. Ribonucleoside membrane transport by a new class of synthetic carrier. J. Am. Chem. Soc.115, 2998–2999 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolb, H. C., Finn, M. G. & Sharpless, K. B. Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.40, 2004–2021 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinière, A. et al. Cell wall constrains lateral diffusion of plant plasma-membrane proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA109, 12805–12810 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popper, Z. A. et al. Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: from algae to flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.62, 567–590 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mach, J. Cellulose synthesis in phytophthora infestans pathogenesis. Plant Cell20, 500–500 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson, S. Mechanobiology of cell division in plant growth. N. Phytol.231, 559–564 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michels, L. et al. Molecular sensors reveal the mechano-chemical response of Phytophthora infestans walls and membranes to mechanical and chemical stress. Cell Surf.8, 100071 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, X. et al. Molecular mechanism of viscosity sensitivity in BODIPY rotors and application to motion-based fluorescent sensors. ACS Sens.5, 731–739 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogden, M. et al. Cellulose biosynthesis inhibitor isoxaben causes nutrient-dependent and tissue-specific Arabidopsis phenotypes. Plant Physiol.194, 612–617 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engelsdorf, T. et al. The plant cell wall integrity maintenance and immune signaling systems cooperate to control stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Signal.11, eaao3070 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manfield, I. W. et al. Novel cell wall architecture of isoxaben‐habituated Arabidopsis suspension‐cultured cells: global transcript profiling and cellular analysis. Plant J.40, 260–275 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamann, T. & Denness, L. Cell wall integrity maintenance in plants: lessons to be learned from yeast? Plant Signal. Behav.6, 1706–1709 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malivert, A. et al. FERONIA and microtubules independently contribute to mechanical integrity in the Arabidopsis shoot. PLoS Biol.19, e3001454 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng, W. et al. The FERONIA receptor kinase maintains cell-wall integrity during salt stress through Ca2+ signaling. Curr. Biol.28, 666–675.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shih, H.-W. et al. The receptor-like kinase FERONIA is required for mechanical signal transduction in Arabidopsis seedlings. Curr. Biol.24, 1887–1892 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cosgrove, D. J. et al. The growing world of expansins. Plant Cell Physiol.43, 1436–1444 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhn, A. et al. RAF-like protein kinases mediate a deeply conserved, rapid auxin response. Cell187, 130–148.e17 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, W. et al. TMK-based cell-surface auxin signalling activates cell-wall acidification. Nature599, 278–282 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kesten, C. et al. Pathogen‐induced pH changes regulate the growth‐defense balance in plants. EMBO J.38, e101822 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson, F., Sommarin, M. & Larsson, C. Fusicoccin activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by a mechanism involving the C-terminal inhibitory domain. Plant Cell5, 321–327 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbez, E. et al. Auxin steers root cell expansion via apoplastic pH regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA114, E4884–E4893 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finkler, B. et al. Highly photostable ‘super’-photoacids for ultrasensitive fluorescence spectroscopy. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci.13, 548–562 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simkovitch, R. et al. Irradiation by blue light in the presence of a photoacid confers changes to colony morphology of the plant pathogen Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B174, 1–9 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serre, N. B. C. et al. The AUX1-AFB1-CNGC14 module establishes a longitudinal root surface pH profile. eLife12, e85193 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gjetting, S. K. et al. Live imaging of intra- and extracellular pH in plants using pHusion, a novel genetically encoded biosensor. J. Exp. Bot.63, 3207–3218 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnoy, E. A. et al. Biological logic gate using gold nanoparticles and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.2, 6527–6536 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choudhary, A., Kumar, A. & Kaur, N. ROS and oxidative burst: roots in plant development. Plant Divers.42, 33–43 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camejo, D., Guzmán-Cedeño, Á. & Moreno, A. Reactive oxygen species, essential molecules, during plant–pathogen interactions. Plant Physiol. Biochem.103, 10–23 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnabelrauch, L. S. et al. Isolation of pl 4.6 extensin peroxidase from tomato cell suspension cultures and identification of Val–Tyr–Lys as putative intermolecular cross‐link site. Plant J.9, 477–489 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortega-Villasante, C. et al. Fluorescent in vivo imaging of reactive oxygen species and redox potential in plants. Free Radic. Biol. Med.122, 202–220 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nietzel, T. et al. The fluorescent protein sensor roGFP2-Orp1 monitors in vivo H2O2 and thiol redox integration and elucidates intracellular H2O2 dynamics during elicitor-induced oxidative burst in Arabidopsis. N. Phytol.221, 1649–1664 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bourdais, G. et al. Large-scale phenomics identifies primary and fine-tuning roles for CRKs in responses related to oxidative stress. PLoS Genet.11, e1005373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimura, S. et al. CRK2 and C-terminal phosphorylation of NADPH oxidase RBOHD regulate reactive oxygen species production in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell32, 1063–1080 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sewelam, N., Kazan, K. & Schenk, P. M. Global plant stress signaling: reactive oxygen species at the cross-road. Front. Plant Sci.7, 187 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmidt, R. & Schippers, J. H. M. ROS-mediated redox signaling during cell differentiation in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1850, 1497–1508 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frederickson Matika, D. E. & Loake, G. J. Redox regulation in plant immune function. Antioxid. Redox Signal.21, 1373–1388 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheloni, G. & Slaveykova, V. I. Optimization of the C11-BODIPY581/591 dye for the determination of lipid oxidation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by flow cytometry. Cytom. Pt A83, 952–961 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chinchilla, D. et al. The Arabidopsis receptor kinase FLS2 binds flg22 and determines the specificity of flagellin perception. Plant Cell18, 465–476 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wyrsch, I. et al. Tissue‐specific FLAGELLIN‐SENSING 2 (FLS2) expression in roots restores immune responses in Arabidopsis fls2 mutants. N. Phytol.206, 774–784 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berhin, A. et al. The root cap cuticle: a cell wall structure for seedling establishment and lateral root formation. Cell176, 1367–1378.e8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang, H. et al. Mechanisms of ROS regulation of plant development and stress responses. Front. Plant Sci.10, 800 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barros, J. et al. The cell biology of lignification in higher plants. Ann. Bot.115, 1053–1074 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ishikawa-Ankerhold, H. C., Ankerhold, R. & Drummen, G. P. C. Advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques—FRAP, FLIP, FLAP, FRET and FLIM. Molecules17, 4047–4132 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figs. 1–28.

Statistical source data and P values.

Statistical source data and P values.

Statistical source data and P values.

Source data fluorescence spectrum.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data associated with the figures in this paper are publicly available at 10.4121/3464fadd-ccb8-4a6c-9463-e3014bcdf984. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code developed to process and analyze data in this paper are publicly available at 10.4121/3464fadd-ccb8-4a6c-9463-e3014bcdf984.